Abstract

The Antibacterial Resistance Leadership Group (ARLG) has prioritized infections caused by gram-positive bacteria as one of its core areas of emphasis. The ARLG Gram-positive Committee has focused on studies responding to 3 main identified research priorities: (1) investigation of strategies or therapies for infections predominantly caused by gram-positive bacteria, (2) evaluation of the efficacy of novel agents for infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and vancomycin-resistant enterococci, and (3) optimization of dosing and duration of antimicrobial agents for gram-positive infections. Herein, we summarize ARLG accomplishments in gram-positive bacterial infection research, including studies aiming to (1) inform optimal vancomycin dosing, (2) determine the role of dalbavancin in MRSA bloodstream infection, (3) characterize enterococcal bloodstream infections, (4) demonstrate the benefits of short-course therapy for pediatric community-acquired pneumonia, (5) develop quality of life measures for use in clinical trials, and (6) advance understanding of the microbiome. Future studies will incorporate innovative methodologies with a focus on interventional clinical trials that have the potential to change clinical practice for difficult-to-treat infections, such as MRSA bloodstream infections.

Keywords: antibacterial resistance, gram-positive bacterial infections, antibacterial agents, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, vancomycin-resistant enterococci

The Antibacterial Resistance Leadership Group (ARLG) has prioritized infections caused by gram-positive bacteria as one of its scientific priority areas. This article describes accomplishments and future directions of ARLG gram-positive studies.

Antibacterial-resistant gram-positive infections threaten global public health [1], creating an unmet need for new diagnostic and treatment strategies. In response, the Antibacterial Resistance Leadership Group (ARLG) has prioritized infections caused by gram-positive bacteria as one of its 3 core areas of emphasis with 3 main research priorities identified (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Antibacterial Resistance Leadership Group gram-positive research priorities.

The current portfolio of studies includes those investigating methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE), antibiotic treatment strategies, and the microbiome. Here, we summarize ARLG accomplishments in gram-positive bacterial infection research since the last update in 2017 [2] (Table 1) and future directions for these challenging infections.

Table 1.

Completed and Active Gram-positive Studies Since the Last Antibacterial Resistance Leadership Group Update in Clinical Infectious Diseasesa

| Study | Main Summary | Status |

|---|---|---|

| Studies investigating strategies or therapies for the treatment of infections predominantly caused by gram-positive bacteria | ||

| Clostridioides difficile RNA (DIFFR) | Development of a novel multiplex real-time RT-PCR assay designed to more accurately identify true Clostridioides difficile infection without overdiagnosing colonization | Data analysis |

| Strain Temporal Engraftment and Persistence After Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (STEP-FMT) | Identification of specific taxa that may confer long-term MDRO colonization resistance among FMT-treated individuals in a clinical trial of renal transplant recipients undergoing FMT | Data analysis |

| Quality of Life Measurement in Gram-positive Bacterial Infections | Development of HR-QoL measures for use in clinical trials of common antibacterial entry indications | Multiple manuscripts in preparation |

| Studies comparing the effectiveness of novel agents for infections caused by MRSA or VRE | ||

| Dalbavancin as an Option for Treatment of Staphylococcus aureus Bacteremia (DOTS) | Multicenter, open-label, randomized controlled trial comparing dalbavancin to standard of care for adults with complicated SAB or right-sided endocarditis who have cleared bacteremia | Enrollment completed |

| Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci Outcomes Study (VENOUS) | Multicenter study to characterize the clinical characteristics of enterococcal BSI | Published [3, 4] |

| Studies optimizing administration of antimicrobial agents for the treatment of gram-positive infections with respect to dose, dosing interval, and duration | ||

| Prospective Observational Evaluation of the Association Between Initial Vancomycin Exposure and Failure Rates Among Adult Hospitalized Patients With Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Bloodstream Infections (PROVIDE) | Prospective evaluation of the impact of vancomycin AUC/MIC exposures on treatment failure rates among hospitalized adults with MRSA BSIs | Published [5–7] |

| Short-Course Outpatient Antibiotic Therapy for Community-Acquired Pneumonia (SCOUT-CAP) | Multicenter, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, randomized trial comparing a short-course (5 d) vs standard-course (10 d) treatment strategy for CAP in children along with microbiome analysis | Published [8–10] |

Abbreviations: AUC, area under the concentration-time curve; BSI, bloodstream infection; CAP, community-acquired pneumonia; FMT, fecal microbiota transplantation; HR-QoL, health-related quality of life; MDRO, multidrug-resistant organism; MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; RT-PCR, reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction; SAB, Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia; VRE, vancomycin-resistant enterococci.

aSee Doernberg et al [2].

COMPLETED AND ACTIVE STUDIES

Studies Investigating Strategies or Therapies for the Treatment of Infections Predominantly Caused by Gram-positive Bacteria

Improved Molecular Diagnostic Approaches to Detect Clostridioides difficile (DIFFR)

Considered by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as one of the most urgent infectious threats [11], Clostridioides difficile infection is a leading cause of hospital-acquired infection [12] that causes significant morbidity and mortality. Antibiotic exposure [13], the chief risk factor for C. difficile, perturbs the gut microbiome and selects for other antibiotic-resistant organisms, which, in turn, can potentiate C. difficile infection [14]. Current laboratory diagnostic tests for C. difficile lack sufficient sensitivity and specificity to distinguish between active infection versus colonization with metabolically inactive spores, leading to both risk of underdiagnosis of true infection and inappropriate treatment of colonized individuals [15]. Through an ARLG Early-Stage Investigator Seed Grant overseen by the Mentoring Committee, Dr Sixto Leal (mentored by Dr Martin Rodriguez) developed and optimized a novel multiplex real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction assay incorporating 4 distinct C. difficile–specific targets designed to overcome these challenges. In vitro, the assay detects toxin gene expression with a very low analytic limit of detection and without cross-reactivity to other bacterial pathogens, related Clostridium species, or commensal gastrointestinal flora. The assay can discriminate metabolically active C. difficile from dead spores or metabolically active nontoxigenic C. difficile strains, allowing for precise discrimination of active infection from colonization with either toxigenic or nontoxigenic strains. Using a collection of >250 stool samples from patients undergoing C. difficile diagnostic testing, the study team compared the novel assay with glutamate dehydrogenase and toxin enzyme immunoassays (EIAs), DNA-based nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs), and gold-standard toxigenic culture. Preliminary results showed accurate distinction between active C. difficile infection and colonization among patients testing EIA negative/NAAT positive. By more accurately identifying true-positive infections, this test will facilitate appropriate treatment for patients with C. difficile infection while avoiding overtreatment. Future work will entail prospective evaluation of assay performance and evaluation of clinical outcomes associated with its use.

Strain Temporal Engraftment and Persistence After Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (STEP-FMT)

Perturbation of the microbiome results in additional risks beyond C. difficile infection. Intestinal colonization with multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs) frequently precedes invasive clinical infection [16]. Microbiome therapies, such as fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), lead to reduction in antibiotic resistance genes, MDRO colonization, and subsequent infections [17–19]. Persistence of select donor-derived anaerobic bacterial strains, described as engraftment, mediates sustained improvements in the host dysbiotic states associated with MDRO colonization, although the exact mechanisms require further elucidation [20]. STEP-FMT, funded by an ARLG Early Stage Investigator (ESI) Seed Grant to Dr Ahmed Babiker (mentored by Dr Michael Woodworth), aimed to identify the specific taxa that may confer long-term MDRO colonization resistance among FMT-treated individuals. Using samples from participants enrolled in a recently completed randomized controlled clinical trial of FMT for MDRO decolonization in renal transplant recipients (NCT02922816), the study team identified candidate anaerobic taxa with MDRO decolonization by employing metagenomic analytical methods. These methods allow for precise strain-level engraftment measurement [20, 21], supplemented with concomitant anaerobic culturing and whole genome sequencing, for combined strain-resolved metagenomic analyses. Biobanking of key target anaerobic taxa identified in this study will enable future development of well-defined, donor-independent bacterial consortia as a scalable advanced therapeutic and associated diagnostics for the measurement of engraftment [22].

Quality of Life Measurement in Gram-positive Bacterial Infections

While other medical fields have developed well-validated health-related quality of life (HR-QoL) measures [23] for chronic diseases, such as breast cancer [24] and heart failure [25], specific HR-QoL measures have not been developed for acute bacterial infections that are common entry indications sought by drug companies for regulatory approval of new antimicrobials, including complicated urinary tract infection, acute bacterial skin and skin structure infection, complicated intra-abdominal infection, and hospital-acquired/ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia. The ARLG Innovations Group, in collaboration with representatives from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the United States (US) Food and Drug Administration, has developed HR-QoL measures for use in clinical trials. Initial studies focused on patients with S. aureus bacteremia (SAB) and gram-negative bacteremia. First, the group performed in-depth interviews (concept elicitation) to determine patient experiences and examine for a priori and emergent themes, demonstrating impact on multiple domains of HR-QoL, particularly physical and functional ones, even when patients experienced “clinical success” [26]. The next step was to utilize cognitive interviews to refine these measures to reach an end product of an HR-QoL survey ready for use in clinical trials [27]. The final survey, based on items from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) [28], is being used in the Dalbavancin as an Option for Treatment of Staphylococcus aureus Bacteremia (DOTS) trial highlighted in the next section. To inform syndrome-specific measure development, the Quality of Life Taskforce of the Innovations Committee has undertaken several additional projects to adapt the previously developed bloodstream infection (BSI) survey for deployment in clinical trials of antibacterial drugs for common indications [29].

Studies Comparing the Effectiveness of Novel Agents for Infections Caused by MRSA or VRE

Dalbavancin as an Option for Treatment of S. aureus Bacteremia: A Phase 2b, Multicenter, Randomized, Open-Label, Assessor-Blinded Superiority Study to Compare the Efficacy and Safety of Dalbavancin to Standard of Care Antibiotic Therapy for the Completion of Treatment of Patients With Complicated S. aureus Bacteremia (DOTS)

Current standard of care therapy for high-risk SAB, a leading cause of bacteremia and infective endocarditis with stubbornly high mortality rates, currently requires 4–6 weeks of intravenous antibiotic therapy [30–32]. Nearly 10% of patients receiving long-term parenteral therapy experience vascular access–related complications, further complicated by the coexisting opioid use epidemic, as persons who inject drugs (PWID) experience both an increased risk for SAB and adverse treatment outcomes with long-term parenteral therapy [33, 34].

Pharmacokinetic modeling of dalbavancin, a lipoglycopeptide with potent anti-staphylococcal activity and a long half-life, predicts that a 2-dose regimen can provide effective drug levels for up to 6 weeks, making this an appealing treatment option for SAB while avoiding the risks of prolonged parenteral access [35]. Dalbavancin also has lower rates of renal injury than vancomycin [36, 37]. While there are not yet any randomized controlled trials of dalbavancin for the treatment of complicated SAB or endocarditis, the results of phase 2/3 trials for other indications suggest that a 2-dose regimen of dalbavancin may be effective [38–42]. As off-label dalbavancin use for SAB expands, observational data also suggest high rates of clinical success but remain seriously hindered by heterogeneous dosing, nonstandardized outcomes, and residual confounding [43, 44]. Simultaneously, case reports highlight dalbavancin failures, including treatment-emergent resistance [45]. Consequently, there is a clear clinical need for randomized clinical trial data to inform the optimal role for dalbavancin in SAB.

DOTS is a multicenter, open-label, randomized controlled trial comparing dalbavancin to standard of care for adults with complicated SAB or right-sided endocarditis who have cleared bacteremia following at least 72 hours (but no more than 10 days) of effective antibiotic therapy (Figure 2), which has completed enrollment with data analysis underway [46]. Participants were randomized to receive either 2 doses of dalbavancin on days 1 and 8 or a total of 4–8 weeks of standard intravenous monotherapy (nafcillin, oxacillin, or cefazolin for methicillin-susceptible S. aureus; vancomycin or daptomycin for MRSA). While PWID are generally underrepresented in clinical trials, they have been specifically included as a population of interest in DOTS [47].

Figure 2.

Dalbavancin as an Option for Treatment of Staphylococcus aureus Bacteremia (DOTS) study schematic. Figure used under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) from Turner et al [46].

The primary analysis compares the desirability of outcome ranking (DOOR) endpoint between the 2 arms at 70 days after randomization [46]. The DOOR ordinal endpoint is a key innovation adapted from prior ARLG research through the Statistical and Data Management Center and the Innovations Committee. DOOR uniquely incorporates not only the main clinical outcome, but also a comprehensive benefit:risk assessment integrating the occurrence of complications and adverse events. Consequently, DOOR outcomes more accurately reflect meaningful outcomes for clinicians and patients alike [48]. Key exploratory analyses will inform critical aspects of dalbavancin's clinical use. First, DOTS includes a pharmacokinetic substudy with input from the ARLG Pharmacokinetics Working Group to verify target achievement for the full duration of intended therapy and assess predictors of variability in dalbavancin serum levels over time. Second, a range of subgroup analyses will assess dalbavancin's efficacy within populations of special interest, including PWID, immunocompromised hosts, and those with osteomyelitis.

If dalbavancin proves safe and effective, patients with SAB would have the option of completing treatment without risks of prolonged central venous access and physicians could feel comfortable offering such therapy to high-risk populations, such as PWID and unhoused persons. The built-in pharmacokinetics substudy and robust exploratory analyses ensure that much can be learned about the optimal use (and potential pitfalls) of dalbavancin in the event of partial success. Even if dalbavancin proves inferior to current standard of care, the knowledge gained could still save lives as dalbavancin is already increasingly used off-label for SAB. The high likelihood of reshaping the clinical management of SAB regardless of result marks DOTS as a pivotal trial.

Prospective Evaluation of Clinical Outcomes of Cancer Patients With Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococcus faecium Bacteremia (VENOUS)

Vancomycin-resistant enterococci present major therapeutic challenges, particularly for critically ill or immunocompromised patients [49–52]. Optimal treatment is not well-defined as prior clinical outcome data are from studies with significant limitations, including retrospective design, single-center involvement, and/or lacking defined epidemiology of infecting organisms [52–54]. In 2015, an ESI Seed Grant from ARLG supported a young investigator at the time (Dr Jose M. Munita, mentored by Dr Cesar A. Arias) to launch the multicenter Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci Outcomes Study (VENOUS) to describe the clinical characteristics of enterococcal BSI. VENOUS I started with 3 US medical systems and subsequently expanded to additional sites in the US (n = 8), South America (n = 4), Europe (n = 2), and South Korea (n = 1) (VENOUS II). VENOUS II is now supported by an independent grant from the NIH (R01 AI148342) with expected enrollment of up to 1000 patients by 2025.

VENOUS I [3] focused on understanding the risk factors for all-cause in-hospital mortality of enterococcal BSIs (VRE and vancomycin-susceptible enterococci [VSE]) and included genomic characterization of all isolates. Patients with VRE were more critically ill and immunosuppressed compared with patients with VSE bacteremia. Patients infected with VRE experienced higher in-hospital mortality compared with those with VSE (35.7% vs 12.5%). VENOUS I also showed that microbiological failure (duration of bacteremia ≥4 days) was the strongest predictor of in-hospital mortality in patients with Enterococcus faecium bacteremia. Many strains, particularly E. faecium, were found to harbor resistance determinants to multiple classes of antibiotics on resistome analyses, including identification of aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes or mutations associated with linezolid and daptomycin resistance.

VENOUS has created a central repository to explore emerging patterns of enterococcal susceptibility, including an observational study of non-faecium, non-faecalis BSI [55], vanB-containing Enterococcus faecalis [4], and β-lactam susceptibility in E. faecalis [56]. Many questions remain to be answered from this cohort, including the impact of treatment approaches on clinical outcomes.

Studies Optimizing Administration of Antimicrobial Agents for the Treatment of Gram-positive Infections With Respect to Dose, Dosing Interval, and Duration

Prospective Observational Study to Validate the Pharmacodynamic Index for Vancomycin Among Patients With MRSA Bloodstream Infections (PROVIDE)

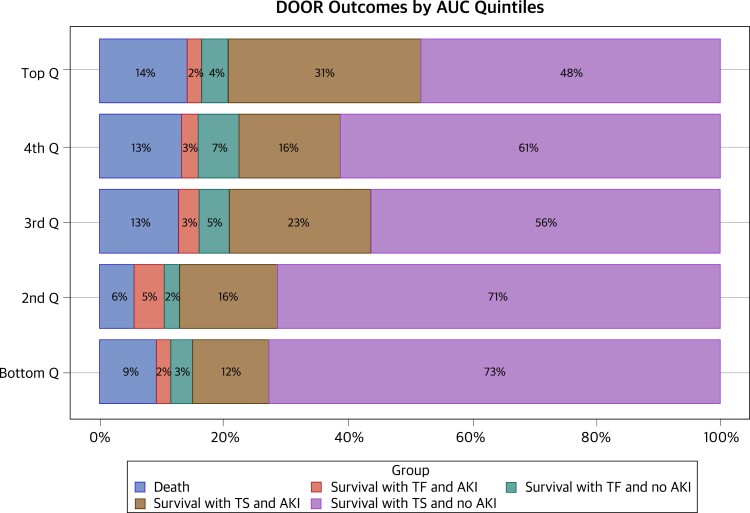

The Prospective Observational Evaluation of the Association Between Initial Vancomycin Exposure and Failure Rates Among Adult Hospitalized Patients With Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Bloodstream Infections (PROVIDE) study was undertaken with leadership from the Pharmacokinetics Working Group to prospectively evaluate the impact of vancomycin exposure [57] on treatment failure rates among adult, hospitalized patients with MRSA BSIs [5]. Using validated, state-of-the-art Bayesian techniques to precisely estimate the vancomycin concentration-time profile in each patient [58], the study found that higher area under the concentration-time curve/minimum inhibitory concentration (AUC/MIC) exposures on day 2 were not associated with clinical benefit but were associated with vancomycin-associated acute kidney injury (VA-AKI), especially among patients who received ≥5 days of therapy [5]. The results also indicated that vancomycin dosing should be guided by the AUC alone versus the AUC/MIC ratio [5, 59]. Most importantly, the findings from the DOOR analyses suggested that day 2 vancomycin AUCs should be maintained between 400 and 515 to maximize efficacy and minimize the likelihood of VA-AKI (Figure 3). The results from PROVIDE directly informed the revised vancomycin guidelines to maintain AUCs between 400 and 600 with a goal of minimizing VA-AKI while maintaining similar effectiveness for patients with suspected or definitive serious invasive MRSA infections and raised the question of whether daily AUC <400 can be maintained in practice without compromising clinical outcomes [6, 60].

Figure 3.

Desirability of outcome ranking analysis by vancomycin area under the curve quintiles. Bottom quintile, 94.3–389.8; second quintile, >389.8–515.7; third quintile, >515.7–620.8; fourth quintile, >620.8–757.4; top quintile, >757.4–1755.0. Abbreviations: AKI, acute kidney injury; AUC, area under the curve; DOOR, desirability of outcome ranking analysis; Q, quintile; TF, treatment failure; TS, treatment success. Figure used with permission from Lodise et al [5].

A Phase 4, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Randomized Trial to Evaluate Short-Course Versus Standard-Course Outpatient Therapy of Community-Acquired Pneumonia (SCOUT-CAP)

Guidelines from the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America recommend 10 days of antibiotic therapy for outpatient pediatric community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) but acknowledge that shorter courses of therapy may be equally effective [61]. Short Course Outpatient Antibiotic Therapy for Community-Acquired Pneumonia (SCOUT-CAP) was a double-blinded, placebo-controlled, randomized trial that compared a short-course (5 days) versus standard-course (10 days) treatment strategy for CAP in children [8].

Similar to DOTS, the study used a DOOR endpoint, this time augmented with a tiebreaker based on the duration of antibiotic therapy actually received, also known as response adjusted for duration of antibiotic risk (RADAR) [62]. The study hypothesized that the short-course strategy would be superior to a standard-course strategy, resulting in similar clinical outcomes with fewer antibiotic-associated adverse effects (using the DOOR component) and fewer days of antibiotic exposure (adding the RADAR component). The probability of a more desirable DOOR for the short-course strategy was 0.48 (95% confidence interval [CI], .42–.53), indicating no difference compared with the standard-course strategy. With the addition of RADAR, the short-course strategy was superior, with an estimated probability for the short-course strategy of 0.69 (95% CI, .63–.75).

Treatment strategies involving shorter courses of antibiotics have been described as a proactive antibiotic resistance management strategy that would decrease antibiotic selection pressure, a hypothesis that is intuitive but not yet evidence-based [63]. In SCOUT-CAP [8], shotgun metagenomic sequencing on serial throat swabs was performed to evaluate the impact of antibiotic treatment on the microbiome and respiratory resistome (ie, the collection of antibiotic resistance genes within the microbiota). The abundance of β-lactam and multidrug efflux pump resistance determinants was significantly lower in children receiving the short versus standard treatment strategy at the end of the study (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, P < .05 for each) [9]. The study team additionally used 16S ribosomal RNA sequencing of longitudinally collected stool samples to identify associations between patient characteristics, microbiota characteristics, and antibiotic-associated diarrhea (AAD) [10]. Overall, 29% of the children developed AAD, and they experienced prolonged dysbiosis compared with children who did not develop AAD (P < .05). Children with a higher baseline relative abundance of 2 potentially protective Bacteroides species were less likely to experience AAD. In contrast, a higher baseline abundance of Lachnospiraceae was associated with AAD. These data advance microbiome research and help inform the design of effective antibiotic treatment strategies that minimize the selection of antibiotic resistance in bacteria. These data also suggest that future studies of antimicrobial efficacy should consider the impact of antibiotics on the microbiota and resistome as part of the trial design.

UNMET NEEDS AND OPPORTUNITIES

Building upon the foundation developed by the ARLG, upcoming work will focus on interventional trials with the potential to change clinical practice. The ARLG Gram-positive Committee will continue to perform deep pathogen and microbiome profiling in the context of these practice-changing trials to simultaneously advance mechanistic understanding of antimicrobial resistance. The PROVIDE study has informed optimal vancomycin dosing. VENOUS has established a robust collection of well-characterized clinical VRE isolates. SCOUT-CAP demonstrated benefits of short-course therapy for pediatric CAP, and DOTS will help determine the optimal role of dalbavancin for SAB. The next generation of studies will leverage our experienced network of sites and investigators to further explore both diagnostic and therapeutic questions. Optimal management of MRSA infections remains an enigma, and many questions remain in how to monitor, look for complications, manage persistent infections, and step down treatment. Trials under development include evaluation of S. aureus DNA-based biomarkers, which may provide a means to personalize the duration of antibiotic therapy, ensuring that patients receive a necessary but not excessive treatment course (Figure 4). A MRSA strategy trial evaluating management approaches for initial therapy, persistent bacteremia (eg, timing of combination therapy), and well-controlled infection (eg oral step-down) is also planned. Future trials will include innovations developed and advanced by the ARLG, including sequential, multiple assignment randomized trials (SMART-COMPASS) [64], DOOR [62], and quality of life measurement [27], to advance understanding of how to manage these challenging gram-positive bacterial infections.

Figure 4.

Sample study schematic for validation and interventional studies using biomarkers to personalize antibiotic management for Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections. Abbreviations: DOOR, desirability of outcome ranking; mNGS, metagenomic next-generation sequencing; SAB, Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia; Tx, treatment; UD, undetectable. Figure used with permission from Mourad A, Fowler VG Jr, Holland TL. Which trial do we need? Next-generation sequencing to individualize therapy in Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia. Clin Microbiol Infect 2023; 29:955–58.

Contributor Information

Sarah B Doernberg, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, University of California, SanFrancisco, California, USA.

Cesar A Arias, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Houston Methodist Hospital, Houston, Texas, USA; Center for Infectious Diseases, Houston Methodist Research Institute, Houston, Texas, USA; Department of Medicine, Weill-Cornell Medical College, New York, New York, USA.

Deena R Altman, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York, USA; Department of Genetics and Genomics Sciences, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, NewYork, New York, USA.

Ahmed Babiker, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia, USA; Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Helen W Boucher, Tufts University School of Medicine, Medford, Massachusetts, USA.

C Buddy Creech, Division of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, Department of Pediatrics, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tennessee, USA; Vanderbilt Vaccine Research Program, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee, USA.

Sara E Cosgrove, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Scott R Evans, Department of Biostatistics, George Washington University, Washington, District of Columbia, USA.

Vance G Fowler, Jr, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, North Carolina, USA.

Stephanie A Fritz, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Washington University School of Medicine, St Louis, Missouri, USA.

Toshimitsu Hamasaki, Biostatistics Center, George Washington University, Rockville, Maryland, USA.

Brendan J Kelly, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

Sixto M Leal, Jr, Department of Laboratory Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama, USA.

Catherine Liu, Vaccine and Infectious Disease Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, Seattle, Washington, USA; Division of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA.

Thomas P Lodise, Department of Pharmacy Practice, Albany College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences, Albany, New York, USA.

Loren G Miller, Department of Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, California, USA; Division of Infectious Diseases, Lundquist Institute at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, California, USA.

Jose M Munita, Instituto de Ciencias e Innovación en Medicina, Facultad de Medicina Clinica Alemana, Universidad del Desarrollo, Santiago, Chile; Multidisciplinary Initiative for Collaborative Research on Bacterial Resistance, Santiago, Chile.

Barbara E Murray, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, McGovern Medical School, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, Texas, USA.

Melinda M Pettigrew, Department of Epidemiology of Microbial Diseases, Yale School of Public Health, New Haven, Connecticut, USA.

Felicia Ruffin, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, North Carolina, USA.

Marc H Scheetz, Pharmacometrics Center of Excellence, College of Pharmacy, Midwestern University, Downers Grove, Illinois, USA.

Bo Shopsin, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, New York University Grossman School of Medicine, New York, New York, USA; Department of Microbiology, NewYork University Grossman School of Medicine, New York, New York, USA.

Truc T Tran, Center for Infectious Diseases, Houston Methodist Research Institute, Houston, Texas, USA.

Nicholas A Turner, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, North Carolina, USA.

Derek J Williams, Division of Hospital Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine and the Monroe Carell Jr Children's Hospital at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee, USA.

Smitha Zaharoff, Duke Clinical Research Institute, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, North Carolina, USA.

Thomas L Holland, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, North Carolina, USA.

for the Antibacterial Resistance Leadership Group:

Robin Patel, Heather King, Tori Kinamon, Weixiao Dai, Holly Geres, Nancie Deckard, Carl Schuler, Ivra Bunn, Shrabani Sharma, Cathy Wickward, Jason Waller, Holly Wilson, Maureen Mehigan, Varduhi Ghazaryan, Erica Raterman, Tamika Samuel, and Marina Lee

Notes

Author Contributions. S. B. D., V. G. F., and T. L. H. were responsible for conceptualization. S. B. D., C. A. S., A. B., C. B. C., S. M. L., T. P. L., J. M. M., M. M. P., F. R., T. T. T., N. A. T., D. J. W., and T. L. H. were responsible for writing, original draft preparation, review, and editing. D. R. A., H. W. B., S. E. C., S. R. E., S. A. F., T. H., B. J. K., C. L., L. G. M., B. E. M., M. H. S., B. S., and S. Z. were responsible for writing, review, and editing.

Acknowledgments. The authors would like to thank the following study team members for their contributions making studies and results possible: Robin Patel, Heather King, Tori Kinamon, Weixiao Dai, Holly Geres, Nancie Deckard, Carl Schuler, Ivra Bunn, Shrabani Sharma, Cathy Wickward, Jason Waller, Holly Wilson, Maureen Mehigan, Varduhi Ghazaryan, Erica Raterman, Tamika Samuel, Marina Lee, other Division of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases team members, and the members of the EMMES and CROMS teams. The authors also thank all study sites and study participants, without whom this work would not be possible.

Disclaimer. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Financial support. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) of the National Institutes of Health (award number UM1AI104681).

Supplement sponsorship. This article appears as part of the supplement “The Antibacterial Resistance Leadership Group (ARLG): Innovation and Evolution,” sponsored by the Antibacterial Resistance Leadership Group.

References

- 1. Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators . Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet 2022; 399:629–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Doernberg SB, Lodise TP, Thaden JT, et al. Gram-positive bacterial infections: research priorities, accomplishments, and future directions of the Antibacterial Resistance Leadership Group. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 64(Suppl_1):S24–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Contreras GA, Munita JM, Simar S, et al. Contemporary clinical and molecular epidemiology of vancomycin-resistant enterococcal bacteremia: a prospective multicenter cohort study (VENOUS I). Open Forum Infect Dis 2022; 9:ofab616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Simar SR, Tran TT, Rydell KB, et al. Multisite detection of Tn1549-mediated vanB vancomycin resistance in multidrug-resistant Enterococcus faecalis ST6 in Texas and Florida. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2023; 67:e0128422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lodise TP, Rosenkranz SL, Finnemeyer M, et al. The emperor's new clothes: prospective observational evaluation of the association between initial vancomycin exposure and failure rates among adult hospitalized patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections (PROVIDE). Clin Infect Dis 2020; 70:1536–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lodise TP, Scheetz M, Carreno JJ, et al. Associations between vancomycin exposure and acute kidney injury within the recommended area under the curve therapeutic exposure range among patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections. Open Forum Infect Dis 2022; 9:ofab651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Scheetz MH, Pais GM, Lodise TP, et al. Of rats and men: a translational model to understand vancomycin pharmacokinetic/toxicodynamic relationships. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2021; 65:e0106021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Williams DJ, Creech CB, Walter EB, et al. Short- vs standard-course outpatient antibiotic therapy for community-acquired pneumonia in children: the SCOUT-CAP randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr 2022; 176:253–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pettigrew MM, Kwon J, Gent JF, et al. Comparison of the respiratory resistomes and microbiota in children receiving short versus standard course treatment for community-acquired pneumonia. mBio 2022; 13:e0019522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kwon J, Kong Y, Wade M, et al. Gastrointestinal microbiome disruption and antibiotic-associated diarrhea in children receiving antibiotic therapy for community-acquired pneumonia. J Infect Dis 2022; 226:1109–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2019. Atlanta, GA: CDC, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Magill SS, O’Leary E, Janelle SJ, et al. Changes in prevalence of health care-associated infections in U. S. hospitals. N Engl J Med 2018; 379:1732–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stevens V, Dumyati G, Fine LS, Fisher SG, van Wijngaarden E. Cumulative antibiotic exposures over time and the risk of Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 53:42–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Smith AB, Jenior ML, Keenan O, et al. Enterococci enhance Clostridioides difficile pathogenesis. Nature 2022; 611:780–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Polage CR, Gyorke CE, Kennedy MA, et al. Overdiagnosis of Clostridium difficile infection in the molecular test era. JAMA Intern Med 2015; 175:1792–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Isendahl J, Giske CG, Hammar U, et al. Temporal dynamics and risk factors for bloodstream infection with extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing bacteria in previously-colonized individuals: national population-based cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 2019; 68:641–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Woodworth MH, Hayden MK, Young VB, Kwon JH. The role of fecal microbiota transplantation in reducing intestinal colonization with antibiotic-resistant organisms: the current landscape and future directions. Open Forum Infect Dis 2019; 6:ofz288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Millan B, Park H, Hotte N, et al. Fecal microbial transplants reduce antibiotic-resistant genes in patients with recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 62:1479–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ianiro G, Murri R, Sciumè GD, et al. Incidence of bloodstream infections, length of hospital stay, and survival in patients with recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection treated with fecal microbiota transplantation or antibiotics. Ann Intern Med 2019; 171:695–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Aggarwala V, Mogno I, Li Z, et al. Precise quantification of bacterial strains after fecal microbiota transplantation delineates long-term engraftment and explains outcomes. Nat Microbiol 2021; 6:1309–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Olm MR, Crits-Christoph A, Bouma-Gregson K, et al. Instrain profiles population microdiversity from metagenomic data and sensitively detects shared microbial strains. Nat Biotechnol 2021; 39:727–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kao D, Wong K, Franz R, et al. The effect of a microbial ecosystem therapeutic (MET-2) on recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection: a phase 1, open-label, single-group trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021; 6:282–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wilson IB, Cleary PD. Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life. A conceptual model of patient outcomes. JAMA 1995; 273:59–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Montazeri A. Health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients: a bibliographic review of the literature from 1974 to 2007. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2008; 27:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Garin O, Ferrer M, Pont À, et al. Disease-specific health-related quality of life questionnaires for heart failure: a systematic review with meta-analyses. Qual Life Res 2009; 18:71–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. King HA, Doernberg SB, Miller J, et al. Patients’ experiences with Staphylococcus aureus and gram-negative bacterial bloodstream infections: a qualitative descriptive study and concept elicitation phase to inform measurement of patient-reported quality of life. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 73:237–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. King HA, Doernberg SB, Grover K, et al. Patients’ experiences with Staphylococcus aureus and gram-negative bacterial bloodstream infections: results from cognitive interviews to inform assessment of health-related quality of life. Open Forum Infect Dis 2022; 9:ofab622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. J Clin Epidemiol 2010; 63:1179–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Evans SR, Patel R, Hamasaki T, et al. The future ain’t what it used to be…out with the old…in with the better: Antibacterial Resistance Leadership Group (ARLG) innovations. Clin Infect Dis 2023; 77:321–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hindy JR, Quintero-Martinez JA, Lahr BD, et al. Incidence of monomicrobial Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota—2006 to 2020. Open Forum Infect Dis 2022; 9:ofac190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. van Hal SJ, Jensen SO, Vaska VL, Espedido BA, Paterson DL, Gosbell IB. Predictors of mortality in Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Clin Microbiol Rev 2012; 25:362–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 52:e18–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shrestha NK, Shrestha J, Everett A, et al. Vascular access complications during outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy at home: a retrospective cohort study. J Antimicrob Chemother 2016; 71:506–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wildenthal JA, Atkinson A, Lewis S, et al. Outcomes of partial oral antibiotic treatment for complicated Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia in people who inject drugs. Clin Infect Dis 2023; 76:487–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Carrothers TJ, Chittenden JT, Critchley I. Dalbavancin population pharmacokinetic modeling and target attainment analysis. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev 2020; 9:21–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gonzalez PL, Rappo U, Mas Casullo V, et al. Safety of dalbavancin in the treatment of acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections (ABSSSI): nephrotoxicity rates compared with vancomycin: a post hoc analysis of three clinical trials. Infect Dis Ther 2021; 10:471–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Monteagudo-Martinez N, Solís-García Del Pozo J, Ikuta I, Galindo M, Jordán J. Systematic review and meta-analysis on the safety of dalbavancin. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2021; 20:1095–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Boucher HW, Wilcox M, Talbot GH, et al. Once-weekly dalbavancin versus daily conventional therapy for skin infection. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:2169–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Dunne MW, Puttagunta S, Giordano P, Krievins D, Zelasky M, Baldassarre J. A randomized clinical trial of single-dose versus weekly dalbavancin for treatment of acute bacterial skin and skin structure infection. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 62:545–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jauregui LE, Babazadeh S, Seltzer E, et al. Randomized, double-blind comparison of once-weekly dalbavancin versus twice-daily linezolid therapy for the treatment of complicated skin and skin structure infections. Clin Infect Dis 2005; 41:1407–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Raad I, Darouiche R, Vazquez J, et al. Efficacy and safety of weekly dalbavancin therapy for catheter-related bloodstream infection caused by gram-positive pathogens. Clin Infect Dis 2005; 40:374–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Seltzer E, Dorr MB, Goldstein BP, et al. Once-weekly dalbavancin versus standard-of-care antimicrobial regimens for treatment of skin and soft-tissue infections. Clin Infect Dis 2003; 37:1298–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fazili T, Bansal E, Garner D, Gomez M, Stornelli N. Dalbavancin as sequential therapy for infective endocarditis due to gram-positive organisms: a review. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2023; 61:106749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cooper MM, Preslaski CR, Shihadeh KC, Hawkins KL, Jenkins TC. Multiple-dose dalbavancin regimens as the predominant treatment of deep-seated or endovascular infections: a scoping review. Open Forum Infect Dis 2021; 8:ofab486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Werth BJ, Jain R, Hahn A, et al. Emergence of dalbavancin non-susceptible, vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus (VISA) after treatment of MRSA central line-associated bloodstream infection with a dalbavancin- and vancomycin-containing regimen. Clin Microbiol Infect 2018; 24:429.e1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Turner NA, Zaharoff S, King H, et al. Dalbavancin as an option for treatment of S. aureus bacteremia (DOTS): study protocol for a phase 2b, multicenter, randomized, open-label clinical trial. Trials 2022; 23:407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Serota DP, Chueng TA, Schechter MC. Applying the infectious diseases literature to people who inject drugs. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2020; 34:539–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Doernberg SB, Tran TTT, Tong SYC, et al. Good studies evaluate the disease while great studies evaluate the patient: development and application of a desirability of outcome ranking endpoint for Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infection. Clin Infect Dis 2019; 68:1691–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Weiner LM, Webb AK, Limbago B, et al. Antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with healthcare-associated infections: summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011–2014. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2016; 37:1288–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Weber S, Hogardt M, Reinheimer C, et al. Bloodstream infections with vancomycin-resistant enterococci are associated with a decreased survival in patients with hematological diseases. Ann Hematol 2019; 98:763–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kramer TS, Remschmidt C, Werner S, et al. The importance of adjusting for enterococcus species when assessing the burden of vancomycin resistance: a cohort study including over 1000 cases of enterococcal bloodstream infections. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2018; 7:133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Papanicolaou GA, Ustun C, Young J-AH, et al. Bloodstream infection due to vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus is associated with increased mortality after hematopoietic cell transplantation for acute leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome: a multicenter, retrospective cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 2019; 69:1771–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Prematunge C, MacDougall C, Johnstone J, et al. VRE and VSE bacteremia outcomes in the era of effective VRE therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2016; 37:26–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hefazi M, Damlaj M, Alkhateeb HB, et al. Vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus colonization and bloodstream infection: prevalence, risk factors, and the impact on early outcomes after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Transpl Infect Dis 2016; 18:913–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Axell-House DB, Egge SL, Tran C, Shelburne SA, Arias CA. Non-faecium non-faecalis enterococcal bloodstream infections in patients with cancer. Open Forum Infect Dis 2022; 9(Suppl_2):ofac492.083. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Tran TC, Simar SR, Egge SL, et al. Association of PBP4 variants and β-lactam susceptibility in Enterococcus faecalis. Open Forum Infect Dis 2022; 9(Suppl_2):ofac492.206. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lodise TP, Drusano GL, Zasowski E, et al. Vancomycin exposure in patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections: how much is enough? Clin Infect Dis 2014; 59:666–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Neely MN, Youn G, Jones B, et al. Are vancomycin trough concentrations adequate for optimal dosing? Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014; 58:309–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lodise TP, Drusano G. Vancomycin area under the curve-guided dosing and monitoring for adult and pediatric patients with suspected or documented serious methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections: putting the safety of our patients first. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 72:1497–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Rybak MJ, Le J, Lodise TP, et al. Therapeutic monitoring of vancomycin for serious methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections: a revised consensus guideline and review by the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, and the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2020; 77:835–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Bradley JS, Byington CL, Shah SS, et al. The management of community-acquired pneumonia in infants and children older than 3 months of age: clinical practice guidelines by the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 53:e25–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Evans SR, Rubin D, Follmann D, et al. Desirability of outcome ranking (DOOR) and response adjusted for duration of antibiotic risk (RADAR). Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61:800–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Rice LB. The Maxwell Finland lecture: for the duration-rational antibiotic administration in an era of antimicrobial resistance and Clostridium difficile. Clin Infect Dis 2008; 46:491–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Evans SR, Follmann D, Liu Y, et al. Sequential, Multiple-Assignment, Randomized Trials for COMparing Personalized Antibiotic StrategieS (SMART-COMPASS). Clin Infect Dis 2019; 68:1961–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]