Abstract

The extracellular matrix represents a critical regulator of tissue vascularization during embryonic development and postnatal life. In this perspective, we present key information and concepts that focus on how the extracellular matrix controls capillary assembly, maturation, and stabilization, and, in addition, contributes to tissue stability and health. In particular, we present and discuss mechanistic details underlying (1) the role of the extracellular matrix in controlling different steps of vascular morphogenesis, (2) the ability of endothelial cells (ECs) and pericytes to coassemble into elongated and narrow capillary EC-lined tubes with associated pericytes and basement membrane matrices, and (3) the identification of specific growth factor combinations (“factors”) and peptides as well as coordinated “factor” and extracellular matrix receptor signaling pathways that are required to form stabilized capillary networks.

In this perspective, we highlight key aspects for how extracellular matrices (ECMs) regulate vascular morphogenesis, maturation, and stabilization. A central point is that vascular cell–ECM interactions signal each of these processes to control tissue vascularization in health and disease states. Furthermore, vascularization is known to be required for tissue development, and there is accumulating evidence for paracrine cross talk between blood vessels such as capillaries with developing tissue parenchymal cells to facilitate tissue assembly and differentiation (Butler et al. 2010; Cleaver and Dor 2012; Ramasamy et al. 2015, 2016; Rafii et al. 2016; Augustin and Koh 2017; Koch et al. 2021). The specialization of specific tissue types as well as their associated vasculatures (with their unique features) appear to be controlled by this cross talk. An interesting and important detail is that some of these paracrine signals are delivered by growth factors that are anchored to the vascular ECM (Hynes 2009; Senger and Davis 2011).

This review will be divided into three major sections regarding the ECM and its ability to control the development, maturation, and stability of the vasculature. In brief, these sections include (1) how endothelial cell (EC)–ECM interactions control key steps in vascular morphogenesis, (2) how EC–mural cell interactions regulate ECM remodeling events to induce vascular basement membrane (BM) deposition and vessel maturation, and (3) how ECM and growth factor signaling events coordinate EC morphogenesis and mural cell assembly with the vasculature.

EC INTERACTIONS WITH THE EXTRACELLULAR MATRIX ARE REQUIRED FOR VASCULAR MORPHOGENESIS INCLUDING VASCULOGENESIS AND ANGIOGENESIS

The ECM is required for all vascular morphogenesis including both developmental and postnatal vascularization events (Davis and Senger 2005; Hynes 2007; Rhodes and Simons 2007; Astrof and Hynes 2009; Arroyo and Iruela-Arispe 2010; Senger and Davis 2011). Thus, both vasculogenic and angiogenic vessel formation requires EC–ECM interactions. There are important differences in the ECM in embryonic versus adult tissues; in general, there is less interstitial collagen and collagen cross-linking in the embryonic ECM compared to adult tissue ECM. In contrast, the embryonic ECM is rich in fibronectin and tenascins, interacting proteoglycans such as versican, and glycosaminoglycans such as hyaluronic acid, which facilitate the bridging of these matrix components (Hynes 2007; Astrof and Hynes 2009; Senger and Davis 2011). In adult tissues, during angiogenesis, new sprouting vessels are exposed to interstitial collagens as well as proteins from plasma that leak into tissues following increased vascular permeability and tissue injury responses (Senger 1996; Davis and Senger 2005; Senger and Davis 2011). Plasma proteins such as fibronectin, fibrinogen/fibrin, and vitronectin adsorb and contribute to the ECM during angiogenesis in addition to interstitial collagens such as type I and type III collagen (Dvorak et al. 1983; van Hinsbergh et al. 2001; Davis and Senger 2005; Astrof et al. 2007; Zhou et al. 2008; Astrof and Hynes 2009; Senger and Davis 2011; Nagy et al. 2012). Degradation of the vascular BM was identified as a key step in initiating angiogenic responses from a stable microvascular wall (Paku and Paweletz 1991; Rowe and Weiss 2008).

Control of Extracellular Matrix–Stimulated Vascular Morphogenesis by Integrins

The key class of cell surface receptors that directly controls vascular morphogenesis, which represents EC sprouting behavior, lumen formation, tube elongation, and network formation, are the integrins that bind ECM components in embryonic versus adult tissues (Hynes 1992, 2007; Stupack and Cheresh 2004; Davis et al. 2011, 2015; Senger and Davis 2011). The major integrins involved in all vascular morphogenesis appear to be α5β1 (a fibronectin receptor), αvβ3 (an RGD-binding receptor, which can interact with vitronectin, fibrinogen, fibronectin, and denatured collagens), and α2β1 (a collagen receptor) (Brooks et al. 1994; Davis and Camarillo 1996; Bayless et al. 2000; Francis et al. 2002; Senger et al. 2002; Bayless and Davis 2003; Zweers et al. 2007; San Antonio et al. 2009). These are receptors for interstitial matrices from normal or wounded ECM environments, whether they are derived from embryonic or adult tissues. In contrast, ECs express other β1 integrins including α1β1, α3β1, and α6β1, which are thought to be predominantly BM matrix-binding integrins with affinity for collagen type IV, laminins, nidogens, and perlecan (Miner and Yurchenco 2004; Hohenester and Yurchenco 2013; Pozzi et al. 2017). In this latter instance, these integrins appear to be more important in vessel maturation and stabilization (see the section below on EC interactions with mural cells).

It is intriguing that α5β1, αvβ3, and α2β1, alone among a number of receptors, appear to exert the majority of influence on critical vascular morphogenic processes. This conclusion is based on many in vitro and in vivo studies, including an in vitro model using human ECs in a simplified 3D ECM environment that can be generated using defined ECM components (Davis et al. 2011, 2015). Dramatic EC sprouting behavior, lumen formation, and multicellular tube assembly has been demonstrated to occur in 3D collagen or fibrin matrices (in the absence or presence of serum to mimic injury states) (Fig. 1; Aplin et al. 2008; Koh et al. 2008b; Nakatsu and Hughes 2008). In collagen matrices, α2β1 is required for human EC lumen and tube formation as well as sprouting behavior (Davis and Camarillo 1996; Bayless and Davis 2003; San Antonio et al. 2009). Once EC-lined tubes assemble in 3D collagen matrices (in the absence of pericytes), they still depend on α2β1; the addition of blocking antibodies resulted in collapse of the tube networks (Davis and Camarillo 1996). Interestingly, when ECs were cultured in fibrin/fibronectin gels in the absence of serum and under defined conditions, EC tubulogenesis and sprouting behavior was strongly dependent on the α5β1 integrin (not αvβ3) (Smith et al. 2013). In contrast, in fibrin matrices in the presence of serum, which contributes both fibronectin and vitronectin to the 3D fibrin matrix (and thus mimics a wound environment), EC tube formation and sprouting behavior was dependent on both α5β1 (evaluated using integrin-blocking antibodies) and αvβ3 (as assessed using integrin-blocking antibodies or RGD peptides) (Bayless et al. 2000; Bayless and Davis 2003).

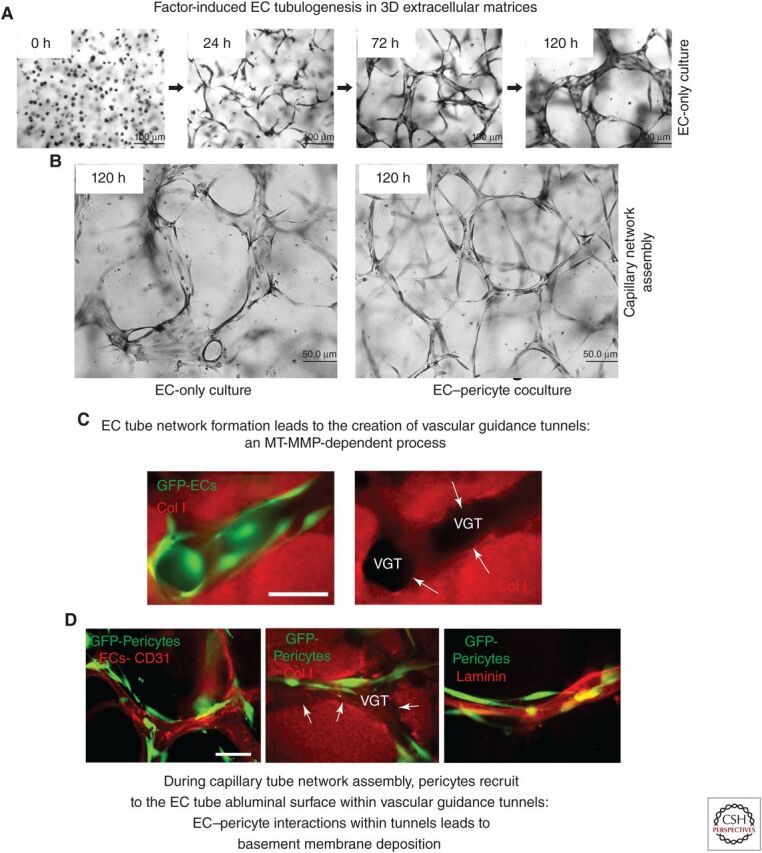

Figure 1.

Extracellular matrix and growth factor–induced signaling stimulates endothelial tubulogenesis, and endothelial–pericyte tube coassembly to generate capillary networks with associated basement membrane matrices. (A) Using a serum-free defined model system with added SCF, IL-3, SDF-1α, FGF-2, and insulin (“factors”) and 3D collagen matrices, endothelial cells (ECs) were seeded alone and were allowed to assemble into networks of EC-lined tubes for the indicated times. Cultures were fixed and stained with toluidine blue. Scale bar, 100 µm. (B) EC-only versus EC and pericyte cocultures were seeded in the presence of the “factors” in 3D collagen matrices and were fixed and stained after 120 h. Scale bar, 50 µm. (C) GFP-labeled EC-only cultures were seeded in collagen matrices and, after 72 h, were fixed and stained with anticollagen type I antibodies (red). (VGTs) Vascular guidance tunnels. White arrows indicate the borders of these tunnel spaces. Scale bar, 50 µm. (D) ECs and GFP-labeled pericytes were cocultured in 3D collagen matrices for 120 h, and, after fixation, were immunostained with antibodies to CD31 to label ECs, collagen type I to delineate the VGT spaces, and laminin to label the vascular basement membrane matrix. White arrows indicate the borders of the tunnel spaces. Scale bar, 50 µm.

Critical Role for Vascular Guidance Tunnels, within the Extracellular Matrix, as Controllers and Conduits for Vascular Morphogenesis and Remodeling of the Vasculature

A key insight into understanding the biology of blood vessel assembly was the discovery that EC tube network formation is accompanied by the generation of ECM-free spaces termed vascular guidance tunnels (Fig. 1; Stratman et al. 2009b), are created through MT-MMP-dependent proteolysis. MT-MMP-dependent proteolysis is a required step for EC formation of tube networks and sprouting in 3D matrices (Bayless and Davis 2003; Chun et al. 2004; Saunders et al. 2006; Stratman et al. 2009b; Sacharidou et al. 2010). Blockade of MT-MMPs using either TIMPs, including TIMP-3 and TIMP-2 (but not TIMP-1), or using chemical inhibitors such as GM6001, completely interferes with EC tubulogenesis or sprouting (Chun et al. 2004; Saunders et al. 2006; Stratman et al. 2009b; Sacharidou et al. 2010) and the creation of these matrix-free tunnels (Stratman et al. 2009b), suggesting that these processes occur concurrently. MT1-MMP strongly contributes to the ability of human ECs to generate vascular guidance tunnels and EC lumen/tube formation (Chun et al. 2004; Saunders et al. 2006; Stratman et al. 2009b; Sacharidou et al. 2010). Whereas MT1-MMP appears to be selectively involved in EC motility in 3D ECM, it does not control cell migration on a two-dimensional (2D) matrix surface (Stratman et al. 2009b). However, if vascular guidance tunnels are first allowed to form for 48–72 h, addition of MT-MMP inhibitors does not block EC motility in 3D matrices. This result suggests that vascular guidance tunnel spaces, once created, are physical spaces in a 3D matrix environment, which mimic a 2D matrix surface. Once the physical tunnel spaces are present, EC tube migration and remodeling can occur that is not dependent on MT1-MMP activity (Stratman et al. 2009b). Furthermore, pericytes recruited to the EC–abluminal surface within vascular guidance tunnels migrate along this surface in a 2D-like matrix environment (Stratman et al. 2009a). Together, the motility of ECs and tube networks with abluminally positioned pericytes that move along the tubes induces the polarized assembly of the capillary BM matrix between the two cell types (Figs. 1 and 2; Stratman et al. 2009a). Very interesting previous work demonstrated that vascular guidance tunnels containing BMs can serve as conduits for rapid vascular regrowth following cessation of antivascular chemotherapeutic regimens directed at tumor angiogenic vessels (Mancuso et al. 2006).

Figure 2.

“Factor”-dependent molecule and signaling requirements for endothelial cell (EC) tubulogenesis, EC–pericyte tube coassembly, and basement membrane deposition, all necessary steps to create capillary networks. (A–C) EC–pericyte cocultures were established in 3D collagen matrices, and, after 120 h, cultures were fixed, photographed under light microscopy (A), or immunostained with antibodies directed to CD31 to visualize ECs (B), or to collagen type IV to visualize basement membrane deposition. Scale bars, 100 µm (A); 50 µm (B,C). (D) Schematic diagram showing key molecule and signaling requirements for ECs to respond to a five-“factor” combination of SCF, IL-3, SDF-1α, FGF-2, and insulin, which stimulates EC tubulogenesis in 3D matrices in conjunction with integrin- and MT1-MMP-dependent signaling events. (Col I) Collagen type I, (FN) fibronectin, (FG) fibrinogen/fibrin. The indicated key molecules and signaling pathways are required for EC lumen and tube formation and include key kinase cascades, small GTPases, and their effectors, and the production of EC-derived factors (PDGF-BB, PDGF-DD, ET-1, TGF-β1, and HB-EGF) that drive pericyte recruitment, pericyte proliferation, and pericyte-induced basement membrane assembly.

EC INTERACTIONS WITH MURAL CELLS CONTROL BLOOD VESSEL MATURATION AND STABILIZATION BY INDUCING VASCULAR BASEMENT MEMBRANE ASSEMBLY

In the stabilized vasculature, ECs are attached to the vascular BM matrix, a matrix environment that favors vascular stability and quiescence. In contrast, in injury responses, ECs get exposed to interstitial matrices such as collagen type I, fibronectin-rich matrices, or fibrin/fibronectin matrices in a wound matrix, which stimulates vascular morphogenesis driving ECs to sprout, elongate, lumenize, and form tube networks. An important concept, first proposed by Donald Senger, is the idea that exposure of ECs to these interstitial matrices creates the “fire” that initiates and stimulates the signaling (Src and Rho activation) necessary for ECs to initiate and undergo vascular morphogenesis (Fig. 3; Whelan and Senger 2003; Liu and Senger 2004; Davis and Senger 2005). He also proposed that exposure of ECs to BM matrices containing laminin isoforms provides an “ice” signal that suppresses morphogenesis and keeps ECs in a stabilized monolayer state with VE-cadherin-based junctional contacts (via increased Rac activation). Another important GTPase controlling EC junctional stability is Rap1, which is activated by Epac1, a guanine exchange factor that is activated by cyclic AMP (Kooistra et al. 2005; Bos 2006; Dejana and Giampietro 2012). In further support of these concepts, using an embryoid body system, a laminin γ1 chain knockout that disrupts all laminin isoforms containing laminin α4 or laminin α5 chains, led to vessels with widened lumens compared to controls, suggesting an inhibitory function for these laminins (Jakobsson et al. 2008).

Figure 3.

Distinct vascular morphogenic (“fire”) versus vascular stabilization (“ice”) signals delivered to endothelial cells (ECs) by exposed interstitial matrices, such as collagen type I or vascular basement membranes (BMs), respectively. Schematic diagram discussing how EC exposure to different types of extracellular matrix (ECM) environments can either lead to initiation/stimulation of vascular morphogenesis (“fire”) or can suppress morphogenesis and lead to stabilization of the vasculature (“ice”). Exposure of ECs to collagen matrices increases Src and Rho activities, which leads to disassembly of VE-cadherin junctions and increases actin stress fibers. These signals cause increased sprouting behavior and EC cord assembly. In contrast, exposure to laminins, such as laminin-511, leads to EC wall stabilization with enhanced VE–cadherin junctions due to increased Rac, Rap, EPAC, and PKA activities. Overall, this leads to suppression of EC activation and morphogenesis. EC adhesive interactions with the vascular BM enhances apicobasal polarization, which further enhances EC junctional stability, and the vascular BM matrix may also facilitate this stabilization by sequestering or inactivating proinflammatory or growth factor/peptide/small molecule mediators that contribute to vascular destabilization.

Pericyte Recruitment to Developing Capillary Tube Networks Plays a Critical Role in Vascular Basement Membrane Assembly

How does the vascular BM induce the signals that suppress EC morphogenesis and stimulate tube stability? It was generally assumed that ECs were capable of assembling this BM on their own. However, pericyte recruitment to developing tubes directly correlates with the deposition of BMs around EC-lined tubes (Stratman et al. 2009a; Kemp et al. 2020) and lymphatic capillaries, which are devoid of pericytes, lack BMs in vivo (Adams and Alitalo 2007). A direct demonstration that pericyte recruitment is necessary for EC tubes to deposit BMs was shown using defined in vitro models with human ECs and pericytes in 3D collagen or fibrin matrices (Stratman et al. 2009a; Smith et al. 2013; Kemp et al. 2020). EC-only cultures fail to deposit BM matrices, whereas EC–pericyte cocultures robustly deposit the major known BM components, including laminins, fibronectin, collagen type IV, perlecan, nidogen-1, and nidogen-2 (Stratman et al. 2009a; Stratman and Davis 2012; Smith et al. 2013). Over time, EC tubes from EC-only cultures continue to widen and become progressively shorter in length and less branched (Fig. 1). In contrast, tubes in EC–pericyte cocultures maintain their narrow diameter and very elongated network pattern over time (Stratman et al. 2009a). In addition, BM deposition (as detected by transmission electron microscopy) was observed only in EC–pericyte cocultures, but not in EC-only cultures (Fig. 4; Stratman et al. 2009a). In quail embryos, BM deposition temporally correlates with the appearance of mural cell recruitment to EC tubes (Stratman et al. 2009a) and is not observed on the tubes prior to pericyte arrival. In addition, a blockade of mural cell recruitment in zebrafish embryos interferes with aortic EC BM deposition (Stratman et al. 2017).

Figure 4.

Endothelial cell (EC)–pericyte interactions control vascular basement membrane (BM) matrix deposition, which changes integrin requirements necessary for vascular wall maturation and stabilization compared to those controlling vascular morphogenesis. (A) EC-only cultures versus EC–pericyte cocultures were established in 3D collagen matrices in the presence of the “factors” and, after 120 h, were fixed and imaged by transmission electron microscopy. Collagen fibrils are visualized on the basal aspects of the tubes and the luminal (L) spaces were devoid of collagen fibrils. The black arrows indicate the vascular BM. Scale bars, 0.5 µm (left panel); 1 µm (right panel). (B) Key morphologic features comparing EC-only cultures to EC–pericyte cocultures in 3D collagen matrices. Blocking antibody experiments revealed complete dependence on the α2β1 integrin in EC-only cultures, while EC–pericyte cocultures demonstrated involvement of the BM-binding integrins, α6β1, α3β1, α1β1, and α5β1, while showing much less involvement of α2β1. EC-only cultures were more susceptible to MMP-1-dependent tube regression (leading to collagen matrix degradation and tube collapse) compared to EC–pericyte cocultures when serine proteinases such as plasminogen (converted to plasmin by ECs) or plasma kallikrein were added due to EC production of TIMP-2 and pericyte production of TIMP-3.

Blockade of Pericyte Recruitment Interferes with Vascular Basement Membrane Matrix Assembly

In support of the conclusion that both pericytes and ECs are necessary for BM deposition are findings showing that pericytes are necessary to stabilize capillary networks. Reduced pericyte association with capillaries leads to increased vessel widths in vivo (Benjamin et al. 1999; Hellström et al. 2001). Blockade of pericyte recruitment and proliferation in response to EC tubes results in marked increases in EC tube width, reduced tube lengths, and strongly reduced BM matrix assembly (Stratman et al. 2010; Kemp et al. 2020). These experiments were performed using combinations of chemical inhibitors directed to pericyte receptors or with blocking antibodies directed to EC-derived factors that drive pericyte recruitment and proliferation during EC–pericyte tube coassembly (see the section on ECM and growth factor signaling) (Fig. 5; Kemp et al. 2020). Blockade of pericyte recruitment in vivo using genetic deletion of PDGFRβ or PDGF-BB leads to reduced mural cell association with capillaries, which leads to vessel widening and instability, increased permeability, and decreased BM deposition (Lindahl et al. 1998; Hellström et al. 2001; Betsholtz et al. 2005; Armulik et al. 2011; Fuxe et al. 2011; Stratman et al. 2017). Overall, these results indicate that pericytes play a direct role in mediating capillary BM matrix deposition, which in turn controls capillary wall maturation and stability.

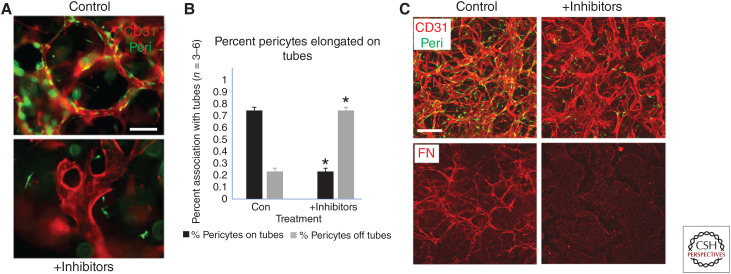

Figure 5.

Blockade of pericyte recruitment during capillary assembly induces less elongated and markedly widened endothelial cell (EC) tubes with strongly reduced deposition of basement membrane matrices. A mixture of chemical inhibitors directed to pericyte receptors, which recognize EC-derived factors that stimulate pericyte recruitment and proliferation, were added to EC–pericyte cocultures for 120 h. The combined chemical inhibitors included imatinib (which blocks PDGFRβ), CI 1020 (which blocks endothelin receptor A), SB431542 (to block the TGF-β receptor, Alk5), and gefitinib (which blocks EGF receptors), and their addition was compared to control cultures. (A) Untreated versus inhibitor-treated cultures were stained with anti-CD31 antibodies to label ECs, revealing marked shortening and widening of EC tubes following addition of the inhibitors. Pericytes were labeled with GFP. Scale bar, 50 µm. (B) Quantitation of pericyte recruitment following inhibitor treatment reveals marked blockade of pericyte recruitment and elongation along the EC-lined tubes compared to control conditions. Asterisks indicate significance at p < 0.05 (n = 6). (C) Control versus inhibitor-treated cocultures were fixed at 120 h and were immunostained with anti-CD31 and anti-fibronectin (FN) to stain the vascular basement membrane matrix. Scale bar, 50 µm.

Mouse Cardiovascular Phenotypes in Genetic Knockout of Vascular Basement Membrane Matrix Components

An approach to assess the functional role of BM components within the vasculature has been to perform genetic knockouts for each of the key vascular BM genes including laminins α4 and α5 (which contribute laminins 411, 421, 511, and 521), fibronectin, collagen type IV, perlecan, nidogen-1, and nidogen-2 (Table 1). Most of the global BM knockout phenotypes are embryonically lethal with significant impairment in the developing vasculature. The defects are particularly severe in the fibronectin knockout mice (including fibronectin splice variants), which have profound vascular morphogenic and other mesodermal developmental abnormalities (Table 1; George et al. 1993, 1997; Francis et al. 2002; Astrof et al. 2007). Global knockout of either of the two major laminin α chains (α4 and α5) in the vascular BM leads to vascular developmental abnormalities. In the α5 laminin chain knockouts, embryonic lethality occurs due to severe abnormalities in the placenta, neural tube, and limbs (Miner et al. 1998). By contrast, the α4 knockout mice show a milder phenotype with minimal embryonic lethality (Thyboll et al. 2002). However, these mice do manifest vascular hemorrhages and are anemic early on, which correlates with reduced BM deposition of laminin, collagen type IV, and perlecan around vessels. Then, over time, the α4 laminin chain knockouts recover, and their vasculatures normalize including the BMs. Furthermore, there is increased deposition of α5 laminins (Wu et al. 2009). Of great interest, the microvasculature with increased abluminal EC α5 laminin isoforms demonstrates improved vessel stability with reduced vascular permeability as well as decreased neutrophils or T-cell tissue infiltration (Wu et al. 2009). Under normal circumstances, there are areas of the postcapillary venule basement with reduced α5 laminin deposition that represent hot spots for vascular permeability and leukocyte transmigration (Richards et al. 2021). With endothelial-specific α4 laminin knocked out, laminin α5 levels increase, resulting in decreased vascular permeability and leukocyte transmigration (Song et al. 2017). By contrast, knockout of EC α5 laminin in ECs leads to increased neutrophil transmigration. Another significant point is that α5 laminins, such as laminin 511, have been shown to increase VE-cadherin-based junctional contacts and transendothelial resistance in cultured ECs (Song et al. 2017; Richards et al. 2021).

Table 1.

Developmental and postnatal cardiovascular defects secondary to mouse knockouts of vascular basement membrane matrix genes

| Basement membrane (BM) component | Mouse knockout phenotype | Specific vascular phenotypic defects/comments | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laminin α4 chain (laminins 411, 421) | Mild, early postnatal lethality, newborns lethargic, pale, and icteric due to anemia and hemorrhage, survivors improve and have normal life span. Corneal angiogenesis assays with FGF-2 reveal early, more intense sprouting and grossly distorted vasculature with apparent hemorrhages and dilated vessels. | Diffuse hemorrhagic phenotype from small vessels, particularly associated with parturition. Discontinuous BM in capillaries with delays in deposition and reductions in collagen type IV and nidogen staining but normal levels of perlecan. Adult null mice correct these defects and have normal levels of collagen type IV, nidogen, perlecan, and express laminin 511 more uniformly in capillary BMs. Reduced T-cell infiltration in the brain of EAE-induced disease in mice to mimic multiple sclerosis due to elevated BM laminins contacting α5 chain. | Thyboll et al. (2002) and Wu et al. (2009) |

| Laminin α5 chain (laminins 511, 521) | Embryonic lethality between E13.5 and 16.5 with limb, neural tube, and placental defects. Placental labyrinth is malformed, which primarily consists of interacting trophoblasts and endothelial cells (ECs) with intervening BMs. | At E13.5–16.5, vessels were present in placental labyrinth, but the branching complexity was markedly reduced and vessel diameters were significantly increased. In normal embryos, trophoblasts and ECs are separated only by a BM while in the mutant, only the ECs remained adherent to the BM creating a cell-free space. EC-selective knockout of LM α5 chain leads to increased neutrophil transmigration, while knockout of LM α4 does the opposite due to increased vascular LMs containing the α5 subunit. Vascular LMs with the α5 subunit enhance VE-cadherin-induced EC junctional stability. | Miner et al. (1998) and Song et al. (2017) |

| Fibronectin | Embryonic lethality after E8.5 with deficits in mesodermal development, particularly notochord, somites, and heart, as well as embryonic and extraembryonic vasculature. Combined knockout of alternatively spliced exons EIIIA and EIIIB show embryonic lethality (usually by E10.5) due to cardiovascular defects including failure of vascular remodeling and hemorrhage. | Cardiac and vascular defects vary with the genetic background (more severe defects in 129S4 vs. C57BL/6J background) as well as vessel location. In some cases, defects in EC–mesenchymal interactions (e.g., heart and aorta) may underlie the vascular morphogenic defects observed. | George et al. (1993, 1997) and Astrof et al. (2007) |

| Collagen type IV, α1/α2 chains | Embryonic lethality between E10.5 and E11.5; BM laminin and nidogen-1 were detected underlying epithelia and endothelia, although showed weaker and more patchy staining. Areas of BM discontinuity and fragmentation were apparent. Excessive amounts of maternal blood was present in the yolk sac cavity indicative of hemorrhage as was the presence of pericardial bleeding. | Impairment of the placental labyrinth was apparent as its thickness was reduced. At the time of embryonic death, dilated blood vessels were observed. Overall, vascular development appeared relatively normal with reduced capillary density sprouting into the neural layer. However, hemorrhage was observed in the heart and arteries with excessive yolk sac hemorrhage indicative of abnormalities in EC BM contacts or stability. Hemizygous knockout of Col IV α1 and α2 chains leads to the development of aortic aneurysms. | Pöschl et al. (2004) and Steffensen et al. (2021) |

| Perlecan | Embryonic lethality between E10 and E12 as well as perinatally. The lethality occurs due to hemopericardium and cardiac arrest. There is no evidence for placental or vascular defects. | There are few apparent vascular developmental defects except for some microaneurysms that form in several tissues including lung, skin, and brain. Later than E12.5 and by E15.5, vascular stability defects become apparent, particularly in the brain and skin. | Costell et al. (1999) and Gustafsson et al. (2013) |

| Nidogen-1 and -2 | Viable mice, some seizure-like with loss of muscle control in hindlimbs, no discernable vascular phenotype. Overall, normal BM assembly and immunostaining of major BM components. | Minimal to no vascular abnormalities, some structural abnormalities in BM matrix of brain capillaries. Nidogen-2 appears to be expressed in higher amounts in EC BMs compared to other BMs. Probable compensation for both nidogen-1 and -2 following knockout. Double knockout of Nid1 and Nid2 leads to skin capillary breakdown with red blood cell extravasation. | Murshed et al. (2000), Miosge et al. (2002), Dong et al. (2002), and Mokkapati et al. (2008) |

Table from Senger and Davis (2011); adapted, with permission, from Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press © 2011.

The global knockout of collagen type IV subunits results in embryonic lethality with vascular hemorrhage and BM discontinuities (Pöschl et al. 2004), whereas combined hemizygous deficiency in the collagen type IV α1 and α2 chains lead to the increased development of aortic aneurysms (Steffensen et al. 2021). Perlecan knockout mice also exhibit embryonic lethality (70%–80%) due to hemorrhage in the pericardial sac (i.e., hemopericardium), which results in cardiac arrest (Costell et al. 1999). There are few vascular abnormalities in the developing mouse prior to E12.5, but as the vasculature matures in surviving embryos, defects become apparent in a proportion of mice (∼40%), particularly in the brain and skin at E15.5 to E17.5 (Gustafsson et al. 2013). The vessels are excessively wide and rupture leading to hemorrhage. Of the vascular basement components, knockout of nidogen-1 or -2 leads to the mildest phenotype with little to no cardiovascular defects (Murshed et al. 2000; Dong et al. 2002; Miosge et al. 2002). This may be due to functional redundancy of the two nidogens, and in support of this idea, global double knockout of nidogen-1 and -2 leads to vascular defects, where skin blood vessels showed reduced BMs with capillary wall fragility and disruption causing prominent red blood cell extravasation (Mokkapati et al. 2008). Overall, these studies demonstrate critical functional roles for a majority of the BM matrix proteins in the structure and function of the forming and stabilized vasculature.

ECM Receptors Including Integrins Control the Assembly of the Vascular Basement Membrane Matrix

In addition to controlling vascular morphogenesis, integrin interactions with ECM are known to control its extracellular assembly. One of the primary examples of this phenomenon is the assembly of fibronectin, a mechanically sensitive protein, whereby stretching of fibronectin exposes matricryptic sites that stimulate its self-assembly (Morla and Ruoslahti 1992; Zhong et al. 1998; Davis et al. 2000; Vogel 2006; Zhou et al. 2008; Davis 2010). Blockade of RhoA-dependent mechanotransduction strongly interferes with fibronectin matrix assembly (Zhong et al. 1998), which can also be inhibited using an amino-terminal 70 kDa fibronectin fragment or by interfering with the activity of the α5β1 integrin (McKeown-Longo and Mosher 1985; Fogerty et al. 1990). Integrin coreceptors such as the syndecans (i.e., cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans), can also influence fibronectin matrix assembly (Klass et al. 2000). The self-assembly of laminins in the vascular BM is also controlled by their receptors including α3β1, α6β1, αvβ3, syndecans, dystroglycan, and membrane-associated sulfatides (Miner and Yurchenco 2004; Yurchenco 2011; Hohenester and Yurchenco 2013; Pozzi et al. 2017). For collagen type IV self-assembly, major integrins with affinity for this ECM component are α1β1 and α2β1, and there might also be a role for non-integrin-binding proteins including CMG-2 (Bell et al. 2001; Yurchenco 2011; Pozzi et al. 2017). CMG-2, a cell surface ECM receptor induced during EC tube formation, contains a von Willebrand factor A domain like the α1β1 and α2β1 integrins that allow it to bind collagen type IV and other collagens (Bell et al. 2001). Collagen type IV assembly also appears to be influenced by the coassembly of fibronectin matrices (Stratman et al. 2009a; Miller et al. 2014). During EC–pericyte tube formation and BM deposition, disruption of fibronectin assembly also interferes with the deposition of collagen type IV (Stratman et al. 2009a; Bowers et al. 2016). As with collagen type IV, the deposition of nidogens and perlecan are directly influenced by their interactions with fibronectin, collagen type IV, and laminin isoforms (and vice versa) (Yurchenco 2011; Pozzi et al. 2017).

In addition to the integrins that appear to be the major drivers of vascular morphogenesis (i.e., α5β1, αvβ3, α2β1), ECs also strongly express other β1 integrins with affinity for BM components (i.e., α1β1, α3β1, and α6β1) that are first engaged when they participate in BM deposition and capillary stabilization (Stratman et al. 2009a). Addition of neutralizing antibodies against these integrins had no effect on vascular morphogenesis in the absence of pericytes (where BM deposition fails to occur), but addition of these antibodies individually and in combination to EC–pericyte cocultures led to disruption of capillary development with increases in tube width (Fig. 4; Stratman et al. 2009a). These findings support the concept that these BM-binding integrins (i.e., α6β1, α3β1, α1β1) and possibly other integrin coreceptors more selectively regulate capillary maturation and stabilization rather than morphogenesis. Other integrins, including α5β1, αvβ3, and α2β1, may have dual functions due to their ability to stimulate vascular morphogenesis, but they may also play a functional role in capillary maturation and stabilization due to their affinities for BM components. Thus, these integrins might work in combination with other BM receptors to control this maturation and stabilization process.

Do Healthy Capillaries and Their Associated Basement Membrane Matrices Suppress Basic Disease Mechanisms?

We have previously proposed the concept that healthy capillaries provide signals to suppress basic disease mechanisms, thus promoting tissue health (Davis et al. 2015). Here, we extend this concept to suggest that capillaries and their associated BM matrices provide disease-suppressing signals to facilitate tissue and organismal health (Fig. 6). This effect could be accomplished by capillary stabilization, which, by extension, would promote stabilization of adjacent tissues. Delivery of growth factors, peptides, or other small molecules (oxygen, nutrients, prostaglandins, etc.) delivered from the capillaries might play such a role. Previous investigators have referred to these signals as angiocrine signals (Butler et al. 2010; Ramasamy et al. 2015; Rafii et al. 2016; Koch et al. 2021). However, to suppress basic disease mechanisms, a fundamental role for capillaries and the BM might be to reduce the biological activities or availability of mediators (e.g., proinflammatory, growth factors, peptides, etc.) that contribute to disease. This would contribute both to the stabilization and quiescent state of the vasculature but also to its surrounding tissue cells to promote tissue health.

Figure 6.

Hypothesis: Healthy capillaries and their associated basement membrane matrices are disease suppressors in that they promote the stability and quiescence of the vasculature and its associated tissue parenchyma. Endothelial cell (EC)–pericyte cocultures were established in 3D collagen matrices and, after 120 h, were fixed and stained with antibodies to CD31 to label ECs or collagen-type IV to label basement membranes. Pericytes were labeled with GFP and are shown to recruit to the abluminal surface of EC-lined tubes where the collagen-type IV–rich basement membrane assembles in between the two cell types. We hypothesize that healthy assembled capillaries and their basement membranes stabilize the capillary networks and their adjacent tissue parenchymal by decreasing the availability or activity of proinflammatory mediators or other activating growth factors, peptides, and other small molecules. In this manner, the stabilized capillaries and tissues protect against key mechanisms of disease pathogenesis (listed in the left lower box), and this protection further decreases the development of key diseases that are directly linked to capillary dysfunction and loss (right lower box).

For example, proinflammatory mediators such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and thrombin are well known to destabilize the vasculature, leading to increased vascular permeability, inflammation, thrombosis, and, most recently, were shown to directly cause capillary regression (Pober 2007; Kumar et al. 2009; Rigor et al. 2012; Koller et al. 2020). Mechanisms by which capillary-derived molecules, including those in the BM, could interfere with mediator functions might include (1) sequestration, (2) functional blockade, (3) degradation, or (4) interference with the release (secretion or shedding) of mediators from critical cell types that control tissue injury responses (i.e., tissue parenchymal cells, macrophages, mast cells, lymphocytes, etc.). In contrast, capillary injury or loss, with associated disruption of the capillary BM, might result in the opposite effect, whereby mediators could then be released to activate vascular and other tissue parenchymal and stromal cells. Chronic injury states might result from continuous proinflammatory mediator and other growth factor/mediator exposure, which activates different cell types in the injury site to initiate and propagate disease states. This may also be a mechanism involved in reinitiating vascular morphogenesis and angiogenic sprouting (i.e., the release of VEGF and other key promorphogenic “factors”; see the section on ECM and growth factor signaling) since BM degradation is an important step in this process. In addition, chronic exposure to VEGF appears to contribute to destabilized angiogenic processes occurring during tumor growth or in various eye pathologies including macular degeneration and diabetic retinopathy (Ferrara 1999; Kim and D'Amore 2012; Apte et al. 2019). We propose that such tissues containing destabilized capillaries and disrupted BMs display pathogenic features including edema, inflammation, ischemic damage, thrombosis, hemorrhage, infection, autoimmunity, and fibrosis. Many human diseases are causally related to one or more of these major pathogenic mechanisms.

A few examples of molecules presented by the capillary wall and its ECM to promote capillary and tissue stability are pericyte TIMP-3 (Saunders et al. 2006) and the endothelial anticoagulant system, which blocks the generation and activity of thrombin (Esmon 2006, 2012; Mohan Rao et al. 2014). TIMP-3, an inhibitor of MMPs, ADAMs, and ADAMTSs, is expressed by pericytes and binds the BM through the heparan sulfate chains of perlecan (Saunders et al. 2006; Davis and Senger 2008). The presence of TIMP-3 inhibits the function of Adam17, a sheddase on many cell types, including macrophages and mast cells, which upon activation can induce the release of TNF-α (and other growth factors such as EGF family members) (Lee et al. 2003; Sahin et al. 2004; Smookler et al. 2006). Pericyte TIMP-3 has been reported to block EC lumen formation and sprouting behavior (by blocking MT1-MMP) (Bayless and Davis 2003; Saunders et al. 2006; Stratman et al. 2009b), to block MMP-1 and MMP-10-dependent capillary regression (Saunders et al. 2006), and to play a central role in TGF-β-dependent vascular stabilization (Dave et al. 2018). Pericyte-derived TIMP-3 is strongly reduced in the kidneys of mice with experimentally induced diabetes (Schrimpf et al. 2012) and may contribute to capillary destabilization in this disease. Capillaries also act to reduce inflammatory mediators. For example, EC expression of thrombomodulin and the protein C receptor (Esmon 2006, 2012) provides an anticoagulant surface by regulating the activation of protein C, and in conjunction with protein S blocks the generation of thrombin. Moreover, circulating inhibitors of thrombin, antithrombin III, and heparin cofactor II, bind glycosaminoglycans including heparan sulfate and dermatan sulfate (that markedly accelerate their thrombin inhibitory activities), which are highly represented in the vascular BM and perivascular ECM (Tollefsen et al. 1989; Huntington 2013). Thus, capillaries and their BMs have the ability to locally reduce the levels and activities of proinflammatory and other mediators.

CONTROL OF VASCULAR MORPHOGENESIS AND MATURATION THROUGH COORDINATION OF GROWTH FACTOR– AND EXTRACELLULAR MATRIX–MEDIATED SIGNALING EVENTS

As previously discussed, the ECM serves as a scaffold to present signals to ECs and mural cells to control vascular morphogenesis and stabilization (Hynes 2007, 2009; Senger and Davis 2011). This insoluble scaffold also binds growth factors and presents them to vascular cells during these processes. In addition, ECM scaffolds such as the BM may play a key role in sequestering growth factors and other mediators to prevent them from activating cells and, thus, promote vessel or tissue stabilization. The ECM can bind growth factors directly through binding to glycosaminoglycan chains (e.g., heparan sulfate) of proteoglycans such as perlecan. Or it can bind growth factor–binding proteins such as IGFBP3, which binds IGFs, or LTBP-1, which binds latent TGF-β isoforms, thus anchoring the growth factors to the ECM. Both IGFBP-3 and LTBP-1 can interact with fibronectin (Taipale et al. 1996; Gui and Murphy 2001; Dallas et al. 2005; Martino and Hubbell 2010) and, in addition, are known to interact with one another. Interestingly, BMP-4, a major growth factor produced by ECs, is known to directly bind collagen type IV (Wang et al. 2008). Stromal-derived factor-1α (SDF-1α), a driver of vascular morphogenesis (see below), can also bind collagen type IV (Yang et al. 2007). Angiopoietin-1, a growth factor produced by pericytes, is known to bind fibronectin, and its receptor, Tie2, directly associates with the fibronectin-binding integrin, α5β1 (Cascone et al. 2005; Saharinen et al. 2008). These interactions may underlie its ability to stabilize vessels and reduce vascular permeability during tissue injury (Fuxe et al. 2011). Fibronectin has been shown to bind VEGF as well as connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), a known binding partner for TGF-β1, -β2, and -β3 (Wijelath et al. 2002; Hoshijima et al. 2006; Martino and Hubbell 2010). Laminin isoforms in the basement membrane directly bind to a variety of growth factors including FGF-2, VEGF, PDGF-BB, and HB-EGF (Ishihara et al. 2018). The close connection between growth factors and the vascular ECM suggests that they are involved in unique signaling events that control vascular morphogenesis and/or stabilization.

Defining the Growth Factors that Control Capillary Tube Assembly and Maturation

A fundamental question in vascular biology is which growth factors and other molecules such as peptides act directly to regulate vascular morphogenesis, maturation, and stabilization. This question needs to be addressed, with respect to both ECs and pericytes, to the two constituents of capillaries. Clearly, these factors must work in concert with the ECM to control EC–pericyte tube assembly. Using genetic approaches primarily in the mouse and zebrafish, the major growth factor drivers of vascular morphogenesis and maturation have been reported to be VEGF, FGF, SDF-1α, angiopoietin-1, PDGF-BB, and TGF-β (Risau and Flamme 1995; Beck and D'Amore 1997; Hirschi et al. 1998; Ferrara 1999; Dvorak 2000; Lawson et al. 2002; Adams and Alitalo 2007; Ramsauer and D'Amore 2007; Murakami and Simons 2008; Siekmann et al. 2009; Armulik et al. 2011). One of the challenges in synthesizing these results is to determine where in the morphogenic or stabilization pathway a particular factor exerts its effect. It is also difficult to assess such questions using in vivo models, since combinations of factors controlling these processes are acting in concert versus in vitro where typically one factor is evaluated at a time.

To address these issues, experiments were performed using a serum-free defined in vitro model system (in 96 microwell plates) to identify which growth factors control the formation of human EC tube networks in 3D collagen or fibrin matrices (Stratman et al. 2011; Smith et al. 2013). Initially, recombinant VEGF and FGF-2 were tested and neither factor individually or in combination were able to support EC tube formation and survival over a 72-h period (Stratman et al. 2011). Marked degeneration of the ECs was observed over this time frame. After this result, an extensive screen was undertaken in the presence of FGF-2 and insulin, to identify individual or combinations of recombinant growth factors that would support tube formation. The combination of FGF-2, SCF, IL-3, SDF-1α, and insulin dramatically stimulated the ability of human ECs to undergo vascular morphogenesis including sprouting, lumen formation, and the development of branched networks of tubes (Stratman et al. 2011; Bowers et al. 2016). This growth factor combination termed the “factors” is the only one that was identified under serum-free defined conditions that allowed for human vascular morphogenesis (i.e., tube formation and sprouting behavior) in either 3D collagen or fibrin matrices. Thus, “factor”-induced signaling appears to be directly coordinated with 3D ECM-mediated signaling to control these critical morphogenic events. Under the same serum-free-culture conditions, the “factors” support EC survival, but not tubulogenesis on a 2D collagen-coated plastic surface, suggesting that EC tubulogenesis and sprouting behavior require a 3D matrix environment (Bowers et al. 2016). Although VEGF does not directly stimulate vascular morphogenesis under these defined serum-free conditions, it was demonstrated to be a primer, although not essential, for downstream “factor”-dependent EC morphogenesis (Stratman et al. 2011; Bowers et al. 2020). VEGF pretreatment and VEGFR2-dependent signaling strongly accelerates “factor”-dependent responses by increasing the number of EC tip cells as well as enhancing EC tube formation, pericyte recruitment, and pericyte-induced EC BM deposition (Bowers et al. 2020).

Coordinated Growth Factor- and Integrin-Dependent Signaling Events Control Capillary Tube Morphogenesis and Maturation

There has been considerable progress in our understanding of the signaling events that control EC tubulogenesis that occurs downstream of the coordinated “factor”- and ECM-stimulated, integrin-dependent signaling pathways (Fig. 2). Key small GTPases and their effectors have been identified that control EC lumen and tube formation including Cdc42, Rac isoforms, k-Ras, and Rap1b as well as major effectors including Pak2, Pak4, Par6b, Par3, IQGAP1, MRCKβ, β-Pix, GIT1, Raf kinases, Rasip1, CCM1, and CCM2 (Bayless and Davis 2002; Bryan and D'Amore 2007; Galan Moya et al. 2009; Iruela-Arispe and Davis 2009; Whitehead et al. 2009; Davis et al. 2011; Xu and Cleaver 2011; Bowers et al. 2016; Norden et al. 2016). Major interfacing kinase signaling cascades are also activated that control EC lumen/tube formation including PKCε, the Src family kinases, Src, Fyn, and Yes, as well as Raf, Mek, and Erk kinases (Alavi et al. 2003; Koh et al. 2008a, 2009; Davis et al. 2011; Patel-Hett and D'Amore 2011; Lanahan et al. 2013; Bowers et al. 2016; Norden et al. 2016; Kim et al. 2017). These signaling molecules are activated by a combination of “factor” receptor and integrin signaling, and this is also coordinated with MT1-MMP-dependent ECM proteolysis to generate EC tubes and vascular guidance tunnels (Saunders et al. 2006; Stratman et al. 2009b; Sacharidou et al. 2010). Experiments using siRNA to suppress various components, expression of dominant-negative mutants, addition of chemical or protein inhibitors, and genetic knockout experiments have demonstrated the role of these major molecules in the EC tubulogenic process (Bowers et al. 2016).

Defining the EC-Derived Growth Factors and Peptides that Control Pericyte Recruitment, Proliferation, and Pericyte-Induced Capillary Basement Membrane Deposition

In support of the conclusion that the “factors” are central regulators of capillary network assembly are experiments in which human ECs and pericytes were cocultured in their presence in either 3D collagen or fibrin matrices. In both cases, dramatic activation and motility of the pericytes occurred and polarized recruitment of pericytes to the abluminal surface of EC-lined tubes was observed (Stratman et al. 2009a, 2011; Smith et al. 2013). In addition, the coculture induced the deposition of the capillary BM. Thus, the “factors” stimulate EC–pericyte tube coassembly creating narrow, elongated tube networks with abluminally deposited BMs, which represent mature capillary networks. Altogether, the “factors,” in combination with integrin signaling, induces the formation of capillaries in 3D matrices that strongly mimic the appearance of capillary networks in vivo (Bowers et al. 2016).

An important observation is that culture of pericytes alone in the presence of the “factors” did not result in pericyte activation (as indicated by motility or proliferation) in 3D matrices. The pericyte responses required the presence of ECs, and the ECs require the “factors” to stimulate these pericyte responses and for EC–pericyte tube coassembly (Stratman et al. 2010; Kemp et al. 2020). In a series of studies, the defined serum-free system (described above) identified EC-derived PDGF-BB, PDGF-DD, ET-1, HB-EGF, and TGF-β1 as the major factors that stimulate pericyte recruitment and proliferation, as well as pericyte-induced EC BM matrix deposition (Stratman et al. 2010; Kemp et al. 2020). Although individual blockade of these molecules or their receptors revealed significant inhibition, combined blockade markedly enhanced the inhibitory effect (Kemp et al. 2020). Under these conditions, the influence of pericytes on EC tube network morphology over time is dramatically abrogated. In fact, with combined blockade, EC tubulogenesis proceeds as if pericytes had never been added (Kemp et al. 2020). A similar effect was not observed when single factors such as PDGF-BB or its receptor PDGFRβ were individually blocked, suggesting that other EC-derived factors are necessary for this EC–pericyte coassembly process to properly occur (Kemp et al. 2020). Overall, these new insights indicate that both ECs and pericytes require a unique set of “factors” to control concurrent capillary tube network and BM assembly, a required process for tissue development, maturation, and maintenance of vascularized tissues to promote organismal health.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

This perspective has addressed how the ECM affects the ability of vascular cells such as ECs and pericytes to assemble and remodel the ECM to form BMs, a necessary step to create stabilized vascular tube networks. Despite the considerable progress in elucidating many of the key molecular and signaling pathways controlling these processes, many questions remain. More work is needed to understand how capillary networks and their BMs provide signals to promote tissue health and stability, as many disease states have associated deficiencies in capillary function or have reduced capillary densities. An important new area for future work should focus on the molecular basis for capillary regression (i.e., rarefaction) (Koller et al. 2020). This process also involves the interface between pro-regressive growth factors and loss of ECM integrity, as ECM proteolysis is a causative factor in developmental vascular failure as well as pathologic capillary collapse and vascular disruption (Saunders et al. 2005, 2006; Chang et al. 2006; Ingram et al. 2013). Additional work is necessary to better understand the biology underlying how the vasculature interacts with the ECM and its associated growth factors and mediators to optimize health benefits and to develop new therapeutic options to treat major human diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants HL136139, HL126518, and HL149748 to G.E.D.

Footnotes

Editors: Diane R. Bielenberg and Patricia A. D'Amore

Additional Perspectives on Angiogenesis: Biology and Pathology available at www.perspectivesinmedicine.org

REFERENCES

- Adams RH, Alitalo K. 2007. Molecular regulation of angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Nat Rev 8: 464–478. 10.1038/nrm2183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alavi A, Hood JD, Frausto R, Stupack DG, Cheresh DA. 2003. Role of Raf in vascular protection from distinct apoptotic stimuli. Science 301: 94–96. 10.1126/science.1082015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aplin AC, Fogel E, Zorzi P, Nicosia RF. 2008. The aortic ring model of angiogenesis. Methods Enzymol 443: 119–136. 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)02007-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apte RS, Chen DS, Ferrara N. 2019. VEGF in signaling and disease: beyond discovery and development. Cell 176: 1248–1264. 10.1016/j.cell.2019.01.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armulik A, Genové G, Betsholtz C. 2011. Pericytes: developmental, physiological, and pathological perspectives, problems, and promises. Dev Cell 21: 193–215. 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo AG, Iruela-Arispe ML. 2010. Extracellular matrix, inflammation, and the angiogenic response. Cardiovasc Res 86: 226–235. 10.1093/cvr/cvq049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astrof S, Hynes RO. 2009. Fibronectins in vascular morphogenesis. Angiogenesis 12: 165–175. 10.1007/s10456-009-9136-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astrof S, Crowley D, Hynes RO. 2007. Multiple cardiovascular defects caused by the absence of alternatively spliced segments of fibronectin. Dev Biol 311: 11–24. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augustin HG, Koh GY. 2017. Organotypic vasculature: from descriptive heterogeneity to functional pathophysiology. Science 357: eaal2379. 10.1126/science.aal2379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayless KJ, Davis GE. 2002. The Cdc42 and Rac1 GTPases are required for capillary lumen formation in three-dimensional extracellular matrices. J Cell Sci 115: 1123–1136. 10.1242/jcs.115.6.1123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayless KJ, Davis GE. 2003. Sphingosine-1-phosphate markedly induces matrix metalloproteinase and integrin-dependent human endothelial cell invasion and lumen formation in three-dimensional collagen and fibrin matrices. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 312: 903–913. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.11.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayless KJ, Salazar R, Davis GE. 2000. RGD-dependent vacuolation and lumen formation observed during endothelial cell morphogenesis in three-dimensional fibrin matrices involves the αvβ3 and α5β1 integrins. Am J Pathol 156: 1673–1683. 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65038-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck L Jr, D'Amore PA. 1997. Vascular development: cellular and molecular regulation. FASEB J 11: 365–373. 10.1096/fasebj.11.5.9141503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell SE, Mavila A, Salazar R, Bayless KJ, Kanagala S, Maxwell SA, Davis GE. 2001. Differential gene expression during capillary morphogenesis in 3D collagen matrices: regulated expression of genes involved in basement membrane matrix assembly, cell cycle progression, cellular differentiation and G-protein signaling. J Cell Sci 114: 2755–2773. 10.1242/jcs.114.15.2755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin LE, Golijanin D, Itin A, Pode D, Keshet E. 1999. Selective ablation of immature blood vessels in established human tumors follows vascular endothelial growth factor withdrawal. J Clin Invest 103: 159–165. 10.1172/JCI5028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betsholtz C, Lindblom P, Gerhardt H. 2005. Role of pericytes in vascular morphogenesis. EXS 94: 115–125. 10.1007/3-7643-7311-3_8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos JL. 2006. Epac proteins: multi-purpose cAMP targets. Trends Biochem Sci 31: 680–686. 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers SLK, Norden PR, Davis GE. 2016. Molecular signaling pathways controlling vascular tube morphogenesis and pericyte-induced tube maturation in 3D extracellular matrices. Adv Pharmacol 77: 241–280. 10.1016/bs.apha.2016.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers SLK, Kemp SS, Aguera KN, Koller GM, Forgy JC, Davis GE. 2020. Defining an upstream VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) priming signature for downstream factor-induced endothelial cell–pericyte tube network coassembly. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 40: 2891–2909. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.120.314517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks PC, Clark RAF, Cheresh DA. 1994. Requirement of vascular integrin αvβ3 for angiogenesis. Science 264: 569–571. 10.1126/science.7512751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan BA, D'Amore PA. 2007. What tangled webs they weave: Rho-GTPase control of angiogenesis. Cell Mol Life Sci 64: 2053–2065. 10.1007/s00018-007-7008-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler JM, Kobayashi H, Rafii S. 2010. Instructive role of the vascular niche in promoting tumour growth and tissue repair by angiocrine factors. Nat Rev Cancer 10: 138–146. 10.1038/nrc2791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cascone I, Napione L, Maniero F, Serini G, Bussolino F. 2005. Stable interaction between α5β1 integrin and Tie2 tyrosine kinase receptor regulates endothelial cell response to Ang-1. J Cell Biol 170: 993–1004. 10.1083/jcb.200507082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang S, Young BD, Li S, Qi X, Richardson JA, Olson EN. 2006. Histone deacetylase 7 maintains vascular integrity by repressing matrix metalloproteinase 10. Cell 126: 321–334. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun TH, Sabeh F, Ota I, Murphy H, McDonagh KT, Holmbeck K, Birkedal-Hansen H, Allen ED, Weiss SJ. 2004. MT1-MMP-dependent neovessel formation within the confines of the three-dimensional extracellular matrix. J Cell Biol 167: 757–767. 10.1083/jcb.200405001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleaver O, Dor Y. 2012. Vascular instruction of pancreas development. Development 139: 2833–2843. 10.1242/dev.065953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costell M, Gustafsson E, Aszódi A, Mörgelin M, Bloch W, Hunziker E, Addicks K, Timpl R, Fässler R. 1999. Perlecan maintains the integrity of cartilage and some basement membranes. J Cell Biol 147: 1109–1122. 10.1083/jcb.147.5.1109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallas SL, Sivakumar P, Jones CJP, Chen Q, Peters DM, Mosher DF, Humphries MJ, Kielty CM. 2005. Fibronectin regulates latent transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ) by controlling matrix assembly of latent TGFβ-binding protein-1. J Biol Chem 280: 18871–18880. 10.1074/jbc.M410762200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dave JM, Mirabella T, Weatherbee SD, Greif DM. 2018. Pericyte ALK5/TIMP3 axis contributes to endothelial morphogenesis in the developing brain. Dev Cell 44: 665–678.e6. 10.1016/j.devcel.2018.01.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis GE. 2010. Matricryptic sites control tissue injury responses in the cardiovascular system: relationships to pattern recognition receptor regulated events. J Mol Cell Cardiol 48: 454–460. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis GE, Camarillo CW. 1996. An α2β1 integrin-dependent pinocytic mechanism involving intracellular vacuole formation and coalescence regulates capillary lumen and tube formation in three-dimensional collagen matrix. Exp Cell Res 224: 39–51. 10.1006/excr.1996.0109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis GE, Senger DR. 2005. Endothelial extracellular matrix: biosynthesis, remodeling, and functions during vascular morphogenesis and neovessel stabilization. Circ Res 97: 1093–1107. 10.1161/01.RES.0000191547.64391.e3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis GE, Senger DR. 2008. Extracellular matrix mediates a molecular balance between vascular morphogenesis and regression. Curr Opin Hematol 15: 197–203. 10.1097/MOH.0b013e3282fcc321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis GE, Bayless KJ, Davis MJ, Meininger GA. 2000. Regulation of tissue injury responses by the exposure of matricryptic sites within extracellular matrix molecules. Am J Pathol 156: 1489–1498. 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65020-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis GE, Stratman AN, Sacharidou A, Koh W. 2011. Molecular basis for endothelial lumen formation and tubulogenesis during vasculogenesis and angiogenic sprouting. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol 288: 101–165. 10.1016/B978-0-12-386041-5.00003-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis GE, Norden PR, Bowers SLK. 2015. Molecular control of capillary morphogenesis and maturation by recognition and remodeling of the extracellular matrix: functional roles of endothelial cells and pericytes in health and disease. Connect Tissue Res 56: 392–402. 10.3109/03008207.2015.1066781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dejana E, Giampietro C. 2012. Vascular endothelial-cadherin and vascular stability. Curr Opin Hematol 19: 218–223. 10.1097/MOH.0b013e3283523e1c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong L, Chen Y, Lewis M, Hsieh JC, Reing J, Chaillet JR, Howell CY, Melhem M, Inoue S, Kuszak JR, et al. 2002. Neurologic defects and selective disruption of basement membranes in mice lacking entactin-1/nidogen-1. Lab Invest 82: 1617–1630. 10.1097/01.LAB.0000042240.52093.0F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak HF. 2000. VPF/VEGF and the angiogenic response. Semin Perinatol 24: 75–78. 10.1016/S0146-0005(00)80061-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak HF, Senger DR, Dvorak AM. 1983. Fibrin as a component of the tumor stroma: origins and biological significance. Cancer Metastasis Rev 2: 41–73. 10.1007/BF00046905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esmon CT. 2006. The endothelial protein C receptor. Curr Opin Hematol 13: 382–385. 10.1097/01.moh.0000239712.93662.35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esmon CT. 2012. Protein C anticoagulant system—anti-inflammatory effects. Semin Immunopathol 34: 127–132. 10.1007/s00281-011-0284-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara N. 1999. Molecular and biological properties of vascular endothelial growth factor. J Mol Med (Berl) 77: 527–543. 10.1007/s001099900019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogerty FJ, Akiyama SK, Yamada KM, Mosher DF. 1990. Inhibition of binding of fibronectin to matrix assembly sites by anti-integrin (α5 β1) antibodies. J Cell Biol 111: 699–708. 10.1083/jcb.111.2.699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis SE, Goh KL, Hodivala-Dilke K, Bader BL, Stark M, Davidson D, Hynes RO. 2002. Central roles of α5β1 integrin and fibronectin in vascular development in mouse embryos and embryoid bodies. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 22: 927–933. 10.1161/01.ATV.0000016045.93313.F2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuxe J, Tabruyn S, Colton K, Zaid H, Adams A, Baluk P, Lashnits E, Morisada T, Le T, O'Brien S, et al. 2011. Pericyte requirement for anti-leak action of angiopoietin-1 and vascular remodeling in sustained inflammation. Am J Pathol 178: 2897–2909. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.02.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galan Moya EM, Le Guelte A, Gavard J. 2009. PAKing up to the endothelium. Cell Signal 21: 1727–1737. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George EL, Georges-Labouesse EN, Patel-King RS, Rayburn H, Hynes RO. 1993. Defects in mesoderm, neural tube and vascular development in mouse embryos lacking fibronectin. Development 119: 1079–1091. 10.1242/dev.119.4.1079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George EL, Baldwin HS, Hynes RO. 1997. Fibronectins are essential for heart and blood vessel morphogenesis but are dispensable for initial specification of precursor cells. Blood 90: 3073–3081. 10.1182/blood.V90.8.3073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gui Y, Murphy LJ. 2001. Insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-binding protein-3 (IGFBP-3) binds to fibronectin (FN): demonstration of IGF-I/IGFBP-3/FN ternary complexes in human plasma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86: 2104–2110. 10.1210/jcem.86.5.7472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson E, Almonte-Becerril M, Bloch W, Costell M. 2013. Perlecan maintains microvessel integrity in vivo and modulates their formation in vitro. PLoS ONE 8: e53715. 10.1371/journal.pone.0053715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellström M, Gerhardt H, Kalén M, Li X, Eriksson U, Wolburg H, Betsholtz C. 2001. Lack of pericytes leads to endothelial hyperplasia and abnormal vascular morphogenesis. J Cell Biol 153: 543–554. 10.1083/jcb.153.3.543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschi KK, Rohovsky SA, D'Amore PA. 1998. PDGF, TGF-β, and heterotypic cell–cell interactions mediate endothelial cell–induced recruitment of 10T1/2 cells and their differentiation to a smooth muscle fate. J Cell Biol 141: 805–814. 10.1083/jcb.141.3.805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohenester E, Yurchenco PD. 2013. Laminins in basement membrane assembly. Cell Adh Migr 7: 56–63. 10.4161/cam.21831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshijima M, Hattori T, Inoue M, Araki D, Hanagata H, Miyauchi A, Takigawa M. 2006. CT domain of CCN2/CTGF directly interacts with fibronectin and enhances cell adhesion of chondrocytes through integrin α5β1. FEBS Lett 580: 1376–1382. 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.01.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huntington JA. 2013. Thrombin inhibition by the serpins. J Thromb Haemost 11: 254–264. 10.1111/jth.12252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes RO. 1992. Integrins: versatility, modulation, and signaling in cell adhesion. Cell 69: 11–25. 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90115-S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes RO. 2007. Cell-matrix adhesion in vascular development. J Thromb Haemost 5: 32–40. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02569.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes RO. 2009. The extracellular matrix: not just pretty fibrils. Science 326: 1216–1219. 10.1126/science.1176009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram KG, Curtis CD, Silasi-Mansat R, Lupu F, Griffin CT. 2013. The NuRD chromatin-remodeling enzyme CHD4 promotes embryonic vascular integrity by transcriptionally regulating extracellular matrix proteolysis. PLoS Genet 9: e1004031. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iruela-Arispe ML, Davis GE. 2009. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of vascular lumen formation. Dev Cell 16: 222–231. 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.01.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara J, Ishihara A, Fukunaga K, Sasaki K, White MJV, Briquez PS, Hubbell JA. 2018. Laminin heparin-binding peptides bind to several growth factors and enhance diabetic wound healing. Nat Commun 9: 2163. 10.1038/s41467-018-04525-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsson L, Domogatskaya A, Tryggvason K, Edgar D, Claesson-Welsh L. 2008. Laminin deposition is dispensable for vasculogenesis but regulates blood vessel diameter independent of flow. FASEB J 22: 1530–1539. 10.1096/fj.07-9617com [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp SS, Aguera KN, Cha B, Davis GE. 2020. Defining endothelial cell–derived factors that promote pericyte recruitment and capillary network assembly. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 40: 2632–2648. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.120.314948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim LA, D'Amore PA. 2012. A brief history of anti-VEGF for the treatment of ocular angiogenesis. Am J Pathol 181: 376–379. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DJ, Norden PR, Salvador J, Barry DM, Bowers SLK, Cleaver O, Davis GE. 2017. Src- and Fyn-dependent apical membrane trafficking events control endothelial lumen formation during vascular tube morphogenesis. PLoS ONE 12: e0184461. 10.1371/journal.pone.0184461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klass CM, Couchman JR, Woods A. 2000. Control of extracellular matrix assembly by syndecan-2 proteoglycan. J Cell Sci 113: 493–506. 10.1242/jcs.113.3.493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch PS, Lee KH, Goerdt S, Augustin HG. 2021. Angiodiversity and organotypic functions of sinusoidal endothelial cells. Angiogenesis 24: 289–310. 10.1007/s10456-021-09780-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh W, Mahan RD, Davis GE. 2008a. Cdc42- and Rac1-mediated endothelial lumen formation requires Pak2, Pak4 and Par3, and PKC-dependent signaling. J Cell Sci 121: 989–1001. 10.1242/jcs.020693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh W, Stratman AN, Sacharidou A, Davis GE. 2008b. In vitro three dimensional collagen matrix models of endothelial lumen formation during vasculogenesis and angiogenesis. Methods Enzymol 443: 83–101. 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)02005-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh W, Sachidanandam K, Stratman AN, Sacharidou A, Mayo AM, Murphy EA, Cheresh DA, Davis GE. 2009. Formation of endothelial lumens requires a coordinated PKCɛ-, Src-, Pak- and Raf-kinase-dependent signaling cascade downstream of Cdc42 activation. J Cell Sci 122: 1812–1822. 10.1242/jcs.045799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koller GM, Schafer C, Kemp SS, Aguera KN, Lin PK, Forgy JC, Griffin CT, Davis GE. 2020. Proinflammatory mediators, IL (interleukin)-1β, TNF (tumor necrosis factor) α, and thrombin directly induce capillary tube regression. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 40: 365–377. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.119.313536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kooistra MRH, Corada M, Dejana E, Bos JL. 2005. Epac1 regulates integrity of endothelial cell junctions through VE-cadherin. FEBS Lett 579: 4966–4972. 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.07.080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P, Shen Q, Pivetti CD, Lee ES, Wu MH, Yuan SY. 2009. Molecular mechanisms of endothelial hyperpermeability: implications in inflammation. Expert Rev Mol Med 11: e19. 10.1017/S1462399409001112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanahan A, Zhang X, Fantin A, Zhuang Z, Rivera-Molina F, Speichinger K, Prahst C, Zhang J, Wang Y, Davis G, et al. 2013. The neuropilin 1 cytoplasmic domain is required for VEGF-A-dependent arteriogenesis. Dev Cell 25: 156–168. 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.03.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson ND, Vogel AM, Weinstein BM. 2002. Sonic hedgehog and vascular endothelial growth factor act upstream of the Notch pathway during arterial endothelial differentiation. Dev Cell 3: 127–136. 10.1016/S1534-5807(02)00198-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DC, Sunnarborg SW, Hinkle CL, Myers TJ, Stevenson MY, Russell WE, Castner BJ, Gerhart MJ, Paxton RJ, Black RA, et al. 2003. TACE/ADAM17 processing of EGFR ligands indicates a role as a physiological convertase. Ann NY Acad Sci 995: 22–38. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb03207.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl P, Hellstrom M, Kalen M, Karlsson L, Pekny M, Pekna M, Soriano P, Betsholtz C. 1998. Paracrine PDGF-B/PDGF-Rβ signaling controls mesangial cell development in kidney glomeruli. Development 125: 3313–3322. 10.1242/dev.125.17.3313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Senger DR. 2004. Matrix-specific activation of Src and Rho initiates capillary morphogenesis of endothelial cells. FASEB J 18: 457–468. 10.1096/fj.03-0948com [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancuso MR, Davis R, Norberg SM, O'Brien S, Sennino B, Nakahara T, Yao VJ, Inai T, Brooks P, Freimark B, et al. 2006. Rapid vascular regrowth in tumors after reversal of VEGF inhibition. J Clin Invest 116: 2610–2621. 10.1172/JCI24612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino MM, Hubbell JA. 2010. The 12th–14th type III repeats of fibronectin function as a highly promiscuous growth factor-binding domain. FASEB J 24: 4711–4721. 10.1096/fj.09-151282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeown-Longo PJ, Mosher DF. 1985. Interaction of the 70,000-mol-wt amino-terminal fragment of fibronectin with the matrix-assembly receptor of fibroblasts. J Cell Biol 100: 364–374. 10.1083/jcb.100.2.364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CG, Pozzi A, Zent R, Schwarzbauer JE. 2014. Effects of high glucose on integrin activity and fibronectin matrix assembly by mesangial cells. Mol Biol Cell 25: 2342–2350. 10.1091/mbc.e14-03-0800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miner JH, Yurchenco PD. 2004. Laminin functions in tissue morphogenesis. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 20: 255–284. 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.094555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miner JH, Cunningham J, Sanes JR. 1998. Roles for laminin in embryogenesis: exencephaly, syndactyly, and placentopathy in mice lacking the laminin α5 chain. J Cell Biol 143: 1713–1723. 10.1083/jcb.143.6.1713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miosge N, Sasaki T, Timpl R. 2002. Evidence of nidogen-2 compensation for nidogen-1 deficiency in transgenic mice. Matrix Biol 21: 611–621. 10.1016/S0945-053X(02)00070-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohan Rao LV, Esmon CT, Pendurthi UR. 2014. Endothelial cell protein C receptor: a multiliganded and multifunctional receptor. Blood 124: 1553–1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokkapati S, Baranowsky A, Mirancea N, Smyth N, Breitkreutz D, Nischt R. 2008. Basement membranes in skin are differently affected by lack of nidogen 1 and 2. J Invest Dermatol 128: 2259–2267. 10.1038/jid.2008.65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morla A, Ruoslahti E. 1992. A fibronectin self-assembly site involved in fibronectin matrix assembly: reconstruction in a synthetic peptide. J Cell Biol 118: 421–429. 10.1083/jcb.118.2.421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami M, Simons M. 2008. Fibroblast growth factor regulation of neovascularization. Curr Opin Hematol 15: 215–220. 10.1097/MOH.0b013e3282f97d98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murshed M, Smyth N, Miosge N, Karolat J, Krieg T, Paulsson M, Nischt R. 2000. The absence of nidogen 1 does not affect murine basement membrane formation. Mol Cell Biol 20: 7007–7012. 10.1128/MCB.20.18.7007-7012.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy JA, Dvorak AM, Dvorak HF. 2012. Vascular hyperpermeability, angiogenesis, and stroma generation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2: a006544. 10.1101/cshperspect.a006544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakatsu MN, Hughes CC. 2008. An optimized three-dimensional in vitro model for the analysis of angiogenesis. Methods Enzymol 443: 65–82. 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)02004-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norden PR, Kim DJ, Barry DM, Cleaver OB, Davis GE. 2016. Cdc42 and k-Ras control endothelial tubulogenesis through apical membrane and cytoskeletal polarization: novel stimulatory roles for GTPase effectors, the small GTPases, Rac2 and Rap1b, and inhibitory influence of Arhgap31 and Rasa1. PLoS ONE 11: e0147758. 10.1371/journal.pone.0147758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paku S, Paweletz N. 1991. First steps of tumor-related angiogenesis. Lab Invest 65: 334–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel-Hett S, D'Amore PA. 2011. Signal transduction in vasculogenesis and developmental angiogenesis. Int J Dev Biol 55: 353–363. 10.1387/ijdb.103213sp [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pober JS. 2007. Effects of tumour necrosis factor and related cytokines on vascular endothelial cells. Ciba Found Symp 131: 170–191. 10.1002/9780470513521.ch12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pöschl E, Schlötzer-Schrehardt U, Brachvogel B, Saito K, Ninomiya Y, Mayer U. 2004. Collagen IV is essential for basement membrane stability but dispensable for initiation of its assembly during early development. Development 131: 1619–1628. 10.1242/dev.01037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozzi A, Yurchenco PD, Iozzo RV. 2017. The nature and biology of basement membranes. Matrix Biol 57–58: 1–11. 10.1016/j.matbio.2016.12.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafii S, Butler JM, Ding BS. 2016. Angiocrine functions of organ-specific endothelial cells. Nature 529: 316–325. 10.1038/nature17040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramasamy SK, Kusumbe AP, Adams RH. 2015. Regulation of tissue morphogenesis by endothelial cell-derived signals. Trends Cell Biol 25: 148–157. 10.1016/j.tcb.2014.11.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramasamy SK, Kusumbe AP, Itkin T, Gur-Cohen S, Lapidot T, Adams RH. 2016. Regulation of hematopoiesis and osteogenesis by blood vessel–derived signals. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 32: 649–675. 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-111315-124936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsauer M, D'Amore PA. 2007. Contextual role for angiopoietins and TGFβ1 in blood vessel stabilization. J Cell Sci 120: 1810–1817. 10.1242/jcs.003533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes JM, Simons M. 2007. The extracellular matrix and blood vessel formation: not just a scaffold. J Cell Mol Med 11: 176–205. 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2007.00031.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards M, Pal S, Sjoberg E, Martinsson P, Venkatraman L, Claesson-Welsh L. 2021. Intra-vessel heterogeneity establishes enhanced sites of macromolecular leakage downstream of laminin α5. Cell Rep 35: 109268. 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigor RR, Beard R, Litovka OP, Yuan SY. 2012. Interleukin-1β-induced barrier dysfunction is signaled through PKC-θ in human brain microvascular endothelium. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 302: C1513–C1522. 10.1152/ajpcell.00371.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risau W, Flamme I. 1995. Vasculogenesis. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 11: 73–91. 10.1146/annurev.cb.11.110195.000445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe RG, Weiss SJ. 2008. Breaching the basement membrane: Who, when and how? Trends Cell Biol 18: 560–574. 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]