Abstract

Introduction:

Since 2004, the Children’s Oral Health Initiative (COHI) has been working in many First Nations and Inuit communities in Canada to address oral health disparities, specifically early childhood caries (ECC). The COHI community-based approach improves early childhood oral health (ECOH) by balancing prevention with minimally invasive dentistry. The goal is to reduce the burden of oral disease, mainly by minimizing the need for surgery. We investigated program success in First Nations communities in the province of Manitoba, from the perspective of COHI staff.

Methods:

First Nations community-based dental therapists and dental worker aides participated in three focus groups and an in-depth semistructured interview. The collected data were thematically analyzed.

Results:

Data from 22 participants yielded converging and practitioner-specific themes. Participants reported that dental therapists and dental worker aides provide access to basic oral care in their communities including oral health assessments, teeth cleaning, fluoride varnish applications and sealants. The participants agreed that education, information sharing and culturally appropriate parental engagement are crucial for continuous support and capacity building in the community programs. Low enrolment, difficulty accessing homes and getting consent, limited human resources as well as lack of educational opportunities for dental worker aides were identified challenges.

Conclusion:

Overall, the participants reported that the COHI program positively contributes to ECOH in First Nations communities. However, increased community-based training for dental workers, community awareness about the program, and engagement of parents to facilitate culturally appropriate programming and consent processes are critical to improving program outcomes.

Keywords: qualitative research, early childhood oral health, Indigenous people, dental care for children, community-based oral health, oral health promotion, Manitoba, Canada

Highlights

The Children’s Oral Health Initiative (COHI) program is contributing to the promotion of early childhood oral health in Manitoba First Nations communities.

COHI workers network with existing community programs and provide dental services, preventive oral health education and care through home and school visits.

Difficulty accessing homes and getting consent, poor housing conditions, limited resources and inadequate training of dental worker aides are barriers to providing effective preventive oral health care.

Increased community awareness, participation and support of workers are crucial to the effectiveness of the COHI program.

Access to timely treatment of early childhood caries and increased and sustained oral health through COHI may help reduce the incidence or severity of caries.

Introduction

The Children’s Oral Health Initiative (COHI) began as a community-based intervention in 2004. Sponsored by the federal government, COHI was implemented nationally by the First Nations and Inuit Health Branch (FNIHB) of Indigenous Services Canada in many First Nations and Inuit communities to promote early childhood oral health (ECOH) and prevent early childhood caries (ECC). This population health program was established to address the oral health inequities and disparities affecting Indigenous Peoples in Canada.1,2 ECC in First Nations and Inuit children often progresses to severe early childhood caries (S-ECC).3,4 COHI is directed towards children aged 0 to 7 years, their caregivers and pregnant women. Interventions include preventive and non-surgical care in community-based settings.5

As a community-based initiative, COHI emphasizes community ownership, with the health service administrations of participating communities hiring and supporting dental worker aides who deliver services within the community. This approach is in keeping with First Nations’ self-governance and self-determination goals in health care6,7 and recommendations of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.8

The First Nations and Inuit Health Branch (FNIHB) of Indigenous Services Canada is responsible for providing the resources to support the implementation of COHI in communities in most Canadian provinces, including Manitoba.9 COHI workers, that is, dental hygienists, therapists and aides, are hired through First Nations organizations or First Nations bands in those communities that have assumed responsibility for managing their health services; FNIHB operates COHI in other First Nations and Inuit communities.

COHI dental worker aides act as the community members’ link to oral health care; they liaise and network with individuals and programs, raise oral health awareness and provide oral health education, collaborate with and schedule appointments with dental therapists and dental hygienists, and conduct general health promotion and disease prevention activities such as applying fluoride varnish.5

Previous evaluations of the COHI program targeted parents and caregivers with children in the program to assess their perspectives on the program’s effectiveness in increasing access to preventive dental services.10 The long-term effect of the services of COHI dental worker aides on access to the program’s preventive dental services was also measured.11 These studies reported that the program successfully increased access to oral health care.10,11 The parents and caregivers who participated in one of these studies suggested that a community-based oral health prevention strategy had had a beneficial effect on the oral health knowledge and behaviours of the entire community.10 Mathu-Muju et al.11 also found that dental worker aides promoted enrolment and facilitated access to preventive dental services, especially where the program had been uninterrupted and consistently implemented over several years.

Until now, COHI workers’ perspectives on their services as dental therapists, hygienists and aides have not been explored. In this current study, our aim was to evaluate the success of the COHI program in Manitoba First Nations communities through the observations and experiences of community-based COHI staff. The findings could inform decision-making regarding continuation, modifications and expansion of COHI to more First Nations and Inuit communities. Our overall objectives were to explore COHI worker’s attitudes towards and experiences with the program, and to determine their perspectives on the impact the program has on First Nations and Inuit children’s dental health, including what makes COHI successful and what the challenges are in delivering COHI.

Methods

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for the study was obtained from University of Manitoba Human Research Ethics Board (HS19539 - H2016: 096) and the Health Information and Research Governance Committee (HIRGC) at the First Nations Health and Social Secretariat of Manitoba (FNHSSM).

Study design and participant selection

This qualitative study consisted of one key informant in-depth interview and three separate, but consecutive, focus groups with COHI workers. We used purposive (criterion) sampling to select information-rich cases. FNIHB or individual First Nations organizations or bands in Manitoba employed all the COHI workers eligible to participate in this study. FNIHB helped the research team with purposive sampling and direct referrals of participants. This sampling method was deemed appropriate as FNIHB had an existing relationship with all the prospective participants.

In December 2019, the research team invited community-based COHI workers employed in Manitoba to participate in the focus groups in Winnipeg, Manitoba. We used grounded theory methodology to facilitate understanding of participants’ experiences with the COHI program and determine their perspectives on the effect of the initiative on young First Nations and Inuit children’s dental health. In this process, data were collected through interviews and preliminary analyses concurrently, with emerging themes applied to guide the next round of data collection sessions. Such constant comparisons are a key element in the grounded theory approach. Concepts and themes were constructed from the experiences and perspectives shared by participants in the study.

Study participants

Twenty-two COHI workers participated in the focus groups and interview. A key informant who was both a COHI coordinator and a hygienist and who worked with multiple First Nation communities was interviewed separately for their in-depth knowledge as they were unable to attend the focus groups.

Focus groups were in person and the key informant interview was conducted via telephone. Each focus group had seven participants, and sessions were approximately 90 minutes long. The focus groups were conducted at the RBC Convention Centre in Winnipeg, Manitoba, during a COHI training session. The participants received a small honorarium in appreciation for their time and participation.

The focus group procedure and interview guide were reviewed and approved by the research team. Study information and consent forms were administered prior to starting the sessions. The participants were told that their participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw their consent at any time during the focus group and leave the session.

Data collection and analysis

Demographic questionnaires were administered at the start of the sessions, before the focus groups and the interview. The questionnaires were not shared with the qualitative researcher until all data had been collected, and the participants did not identify themselves or others throughout the focus group sessions.

The qualitative researcher (GK-A), a female from outside the communities with over 5years of experience as a qualitative researcher, facilitated the focus group sessions along with two note takers. GK-A also conducted the key informant interview. Her not being a COHI worker put her in a position where she was able to generate themes and concepts without preconceived notions.

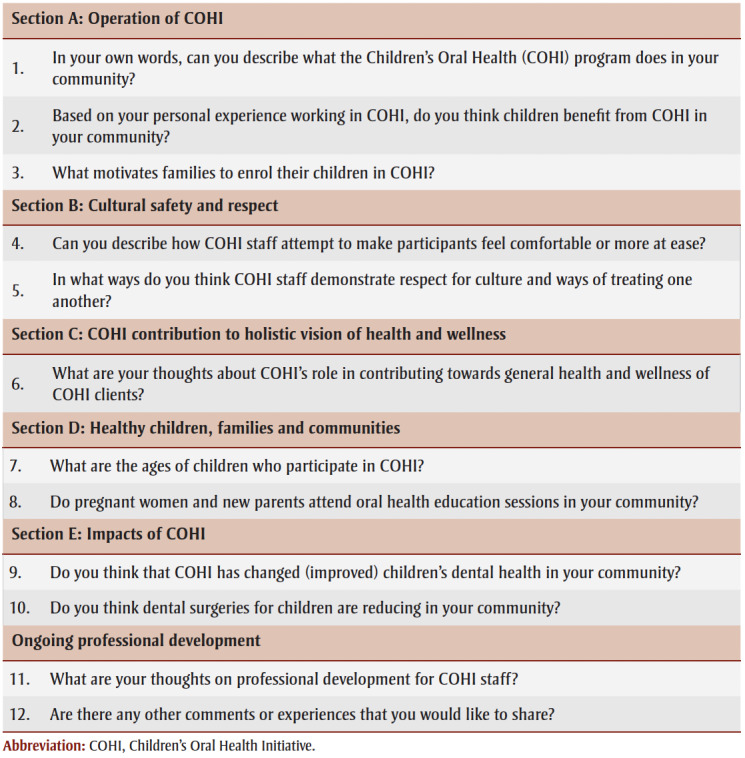

All the participants responded to 12 open-ended interview questions (shown in Table 1 ) to elucidate attitudes, beliefs and values associated with their work. The interview guide was validated through triangulation and consultation with experts in the field. Data were generated primarily through group interactions. The interview questions were intended as a guide, and the participants were encouraged to talk freely about the topic on their own terms.

Table 1. Interview guide for focus groups and the key-informant interview.

|

The participants had a chance to review the notes taken during the focus groups and provide feedback. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Transcribed data arising from the focus groups and key informant interview were reviewed for accuracy, manually coded and assessed for distinct ideas and key themes by the qualitative reviewer (GK-A). The thematic analysis was completed with the goal of understanding the COHI workers’ experiences and to determine their perspectives on the impact of COHI on young First Nations and Inuit children’s dental health.

Data were uploaded and further analyzed using NVivo qualitative software version12 (QSR International Pty Ltd., Melbourne, AU).12

Results

Demographic data

Of the 22 COHI workers who participated in the focus group discussions and interview, only 17 completed their demographic questionnaires. Fourteen participants identified as First Nation. Seven COHI workers were dental therapists, two were dental assistants, one was a dental hygienist, three were dental worker aides and one was a dentist. One participant indicated that she was trained as a “community health educator.” Two did not specify their level of training.

Except for one participant, who represented six First Nations communities, and another who represented 11, participants represented one community each. Overall, approximately 25 First Nation communities were represented.

The mean (SD) age of the participants was 47.4 (10.8) years (range: 25–62 years). Sixteen were female and one preferred not to disclose their sex/gender. Participants had worked in the program for an average (SD) of 11.4 (3.5) years (range: 3–15 years).

Key themes

Key themes identified by the qualitative researcher based on data from the focus groups and the key informant interview, with detailed quotes supporting each, are shown in Table 2 .

Table 2. COHI workers’ attitudes towards and opinions of the impact of the COHI program.

Results from the thematic analysis of the focus groups and interview are presented in two over-arching categories: COHI workers’ attitudes and opinions on the impact of COHI on communities; and COHI workers’ challenges when delivering the COHI program.

Thematic analysis: COHI workers’ attitudes and opinions on the impact of the program on communities

All COHI workers said they primarily target children aged 0 to 7 years old. They also work with expectant mothers and mothers of newborns. According to one participant:

COHI is designed to provide preventive oral care for children from 0 to 7 years old. In the schools, [we’re] seeing the children from nursery to Grade 2, and [in the] community, parents of children 0 to 4. [D00TPST]

Some participants said that they extend their services to older children. According to one:

Yes, I am supposed to do COHI, but I don’t limit my classroom presentations to Grade 2. I go all the way through to Grade 12 […] That’s the only way I know that they’re still getting the information. [A003]

The participants said that they provide dental services so that clients do not have to wait for care. They raise awareness of the importance of oral hygiene in young children, educating the children and their parents on oral health. They also distribute oral hygiene products where needed and conduct home and school visits to bring oral health information to parents and teachers.

The participating dental therapists described how the pressure to provide treatment often overshadowed COHI prevention and oral health promotion activities. As a result, they welcomed the support of dental worker aides’ in expanding the educational aspects of ECOH:

I’ve worked in the field as a dental therapist for very many years and all this COHI stuff always fell on us as a dental therapist to do it on our own. The biggest advantage of COHI is having a COHI aide that takes off your shoulders all the one-on-ones with the prenatal [moms], the one-on-ones with the parents, the presentations and doing all the networking in the community […] That takes a load off you for the preventative portion of your program. [C006]

Dental therapists said that they work alone, without dental worker aides, and tend to focus more on activities in the clinics, only sometimes extending their work to schools. Overall, they considered that COHI is helping to arrest ECC. All the participants reported seeing positive changes, with the COHI program doing what can be done to reach more people in the communities with services:

[By] doing the annual fluorides, like we do three times a year, if we can […] I see a lot of arrested decay […] I see the extractions in [the] Grade 3s have come down quite a bit … So yeah, I do see [that] it’s effective. [A007]

Thematic analysis: Challenges in delivering community-based oral health promotion and care

Some participants said that they face challenges in delivering services in the communities, finding it difficult to get access to homes and schools, to conduct oral health assessments or educational sessions with parents. Accessing homes may be hampered by an inability to locate where clients and patients live and not having enough time to include home visits in the schedule; families could be reluctant or embarrassed to be visited at home. COHI workers also expressed concerns about their safety and not knowing what may happen if they go to visit people at their homes, especially where dog attacks have been reported. Some believed patients should be directed to the local clinics for all preventive oral care:

I don’t […] do home visits, [the dental worker aide] doesn’t […] do home visits... because there’s [been] nurses that have gone out and they’ve had dog bites and stuff like that… some people don’t feel comfortable. [B003]

Like, I don’t feel comfortable, someone just pulling up [into] my driveway and saying hi, I want to put varnish in your kid’s mouth. Ok, well, no. And that’s why the clinics are there […] I don’t think we have to chase [clients]. [B003]

COHI workers reported the need for advocates in schools and community environments supporting the program:

There is one community... The principal is totally against a toothbrushing program... He said, “The more we do in the school, the less the parents are doing at home.” It kind of took me by surprise because the first question he asked me was, “How are the kids’ teeth?” I had only seen a few but I had seen worse, so I said they seem to be not too bad. He took that and thought, “Okay, well we don’t need a toothbrushing program. [D00TPST]

Another challenge to the effective delivery of COHI was the shortage of COHI workers and the need for more training of the available dental worker aides. Dental therapists said they did not prioritize home visiting because of their busy schedules. According to one therapist:

I’m not from the communities that I work in. I don’t know where anybody lives, and I don’t have a dental aid or anybody from the community that can take time out of their job to show me where anyone lives. Also… I usually have [clients/students] back [in] their class to get ready to go home by like 10 to 3 [...] that’s the only time I see adults in the community, is after school hours. [B001]

Participants also reported that housing conditions are sometimes a barrier to caregivers adhering to oral health information. The COHI workers were concerned that the anticipatory guidance they provide during their education sessions is not being adopted and followed by parents:

Oh, you can train [parents/caregivers] all you want, [it] doesn’t mean they’re going to do it. Their number one reason [is that they] don’t have time or [they] don’t have a sink in [their] bathroom. [B005]

Another genuine concern is that parents and caregivers in the communities have normalized the treatment of ECC under general anesthesia:

I also find that it is almost like a rite of passage. It’s just like we’ve got to have surgery done before we start school. Just like getting your immunizations. [A004]

The parents think that [general anesthesia] is a normal part of life, part of childhood. [B005]

Like, most of the children that I see […] already have gone through [general anesthesia]. [C001]

The loss of patient follow-up during referrals was a significant challenge. Participants said communication and coordination between community-based COHI workers and off-reserve dentists and dental offices is poor. For example, dentists and dental offices send patients requiring follow-up care back to their home communities without adequate documentation or preliminary information from the community-based dental workers:

After the surgery some of the providers that do the treatment in the city do tell the parents to go in for an assessment in 2 weeks… but it doesn’t get done. [Dental offices] send a report to the regional office and that report is sent to us. But sometimes [these] are like a month after the surgery [the 2-week period doesn’t really happen]. And sometimes there is no report at all from the office. [A001]

The participants also reported difficulties and delays in obtaining consent forms before providing preventive oral care. Consent forms are mostly handed out to students in schools to be delivered to parents and then returned. Forms sometimes get lost in transit. Having more dental worker aides who can work more directly with families will be beneficial to getting timely consent by answering phone and community entry questions:

I think if I can get the dental worker aide more involved, then she would be a great asset to phone people, to be the go-to person for parents to phone and ask questions, to get consent forms. The schools are very cooperative, they will send out consent forms […] but sporadically. If I go into the community, there will be maybe 3 or 4 more consent forms coming in, so they trickle in. While I’m in the community, when I fly in, I like to stay a little longer […] to allow time to send the consent forms out again, so there is time for them to come in while I’m in the community […] Having said that, it doesn’t allow time for those extra consent forms to come in and see those children at the same time. [D00TPST]

Some participants said they are worried that there is not enough awareness of the program in the communities even after several years. Some dental therapists and worker aides reported feelings of despair as they worked hard to curb ECC, and yet the number of children with tooth decay was still high:

You’re creating more awareness in the community about dental health so they’re receiving treatment sooner, at a younger age, but that doesn’t necessarily mean the health of the children is improving because they’re still getting decay. It’s just being treated sooner […] the stats and the dmft [cumulative count of the number of decayed, missing and filled primary teeth due to caries] is not really changing […] I’m saying [that] COHI is making a difference, but slowly. [C005]

Overall, the participants considered the program to be helpful. They said that the changes expected of the program may not be massive, but they are addressing oral health problems in the communities:

I think it’s working, it’s not […] overwhelming, like in your face, a big spat change, but it’s slowly addressing small problems of the bigger issue… I am First Nation; I grew up in isolation, I know exactly what we’re faced with […] But I love what I do. We try and get what we can done, and having the second set of hands to reach more people, I guess, within the working day helps. [C005]

COHI workers’ descriptions of the challenges and barriers to effective delivery of oral health promotion and care are shown in Table 3 .

Table 3. COHI program challenges and barriers according to COHI workers.

Discussion

Investments in community-based health care to promote local control of care and improve Indigenous health outcomes are essential.13,14 The COHI program was implemented, in 2004, in an effort to decrease the burden of ECC in Indigenous children.5

In this study, we evaluated the experiences of community-based COHI workers as well as their perspectives on the impact of the program on First Nations children and their families in Manitoba. The study participants said the COHI program helps to support ECOH and prevent ECC in First Nations communities. This complements the view of parents and caregivers of program beneficiaries.10 The participants described their specific tasks as benefiting children by providing opportunities to affect ECOH positively.5

A key reason for the ongoing successes of the COHI program is the sustained presence of dental worker aides in participating communities.5,11 Dental worker aides provide culturally sensitive oral health promotion activities and community outreach and engagement components, working alongside dental therapists, who focus on preventive dental procedures and, where available, dentists. The dental worker aide’s role is essential in community-based oral health. They facilitate access to dental care and leverage social capital through knowledge of the community’s culture and language, striving to reach children at schools and families at home and networking with other community health and social programs.15,16

Community-based oral health promotion activities are needed to support ECOH in Indigenous communities.17 Hodgins et al.18 previously evaluated the role of dental health support workers in promoting oral health in the community and linking targeted families with young children to a dental practice, as part of the Childsmile program in Scotland. Their findings suggest that children who received dental health support workers’ intervention were more likely to attend a dental practice and to do so earlier than those who did not receive such an intervention.18 This highlights the value of dental worker aides in building bridges between the community and the dental care provider.

Access to culturally safe health care is a significant challenge for rural and remote Indigenous communities.19-21 Dental services provided in communities through COHI mitigate lengthy waits for care at dental offices outside of clients’ communities. Community-based COHI workers create awareness of the importance of oral hygiene in young children, educating children and their parents on oral health. They also distribute oral hygiene products where needed and conduct home and school visits to bring oral health information to parents and teachers.

Culturally sensitive oral health promotion by Indigenous champions, in the manner provided by COHI workers,22 takes into account social determinants of pediatric oral health.23 The health promotion builds on existing cultural knowledge and practices to prevent ECC in Indigenous communities.24 COHI workers and therapists, many of whom are from the communities where they work, are sensitive to local conditions and holistic needs of the people they serve. Workers in the program understand and have pointed out that social determinants and parents’ choices and behaviours go hand in glove; therefore, education must meet the right conditions to enable change. For example, people who are educated in the behaviours best suited to preventing ECC must be able to afford the products to support recommended oral hygiene.

A study evaluating the perspectives of dental therapists practising in Alaska’s Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta reported that the community and oral health care providers noticed the benefits of the community-based education provided by the dental therapists and the improvement in access to dental care and knowledge about oral health over the years.25 As in our study, Chi et al.25 noted the benefit of having oral health care providers who understand the culture and needs of the local communities. Another study conducted in Alaska’s Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta reported that the number of dental treatment days provided in the community by dental therapists was negatively associated with extractions and positively associated with preventive care utilization for children and adults, demonstrating the importance of dental therapists in oral health promotion in underserved communities.26

Recruiting and training more dental professionals so that they could function effectively in their roles would help build capacity, addressing some of the existing challenges. Information could be delivered through community-based workshops27 and ongoing interprofessional collaboration across programs with similar goals of enhancing community-based resilience.28

Large communities may benefit from more dental worker aides to work with families and their children. Dental therapists and dental worker aides can proactively explain program availability and benefits. Awareness is key in health promotion and may serve the program by building on known avenues of community learning through interactions between people, with other community programs and through online sources.17

In a previous study by the same research team, parents in communities in Manitoba suggested the best ways to disseminate oral health-related information. These included information sheets and visual teaching aids in local languages plus the use of social media, provision of oral health products through community programs, and home visits for hands-on teaching.17 In the present study, difficulty accessing homes was described as a barrier to delivering preventive oral health care, with COHI workers being concerned for their safety. A well-coordinated home visit, pre-visit phone calls, and virtual conferencing (where possible and appropriate) may help improve home access.

By increasing awareness among more families in communities, dental worker aides obtain more parental and caregiver consent for their children’s enrolment in the program. To enroll children in the COHI program, parents and caregivers sign the required consent forms. However, COHI workers must be careful that all consent requested and obtained respect local protocols and individual expectations.29 Meeting parents in person to explain the program and obtain written or oral consent would likely yield better enrolment than the current process of children being sent home with consent forms that lack sufficient context.

Participants also raised concerns about referring patients for follow-up care in the community after surgeries under general anesthesia. As some children require advanced oral care that cannot be performed by COHI staff, the program and staff need to build and maintain relationships with dental providers and specialists outside of the communities. More robust communication between COHI workers and dental offices could help improve patient referral pathways and enhance community-based follow-up schedules.

Strengths and limitations

Our study is the first to assess the perspectives of COHI community-based workers on the contribution and impact of the COHI program. The study provides an in-depth and first-hand account of structural and cultural determinants of health in the First Nations communities as they relate to children’s oral health. COHI dental worker aides are knowledge keepers whose self-reported opinions and challenges provide valuable contributions to strategies aimed at improving the effectiveness of COHI programs.

However, although the qualitative approach to our study provides critical experiential insights of workers representing 25 First Nation communities altogether, the results may not be generalizable to other First Nations communities. In addition, some participants may have felt that some of the questions were leading, thereby influencing their responses. Further studies are needed to evaluate the impact of COHI workers’ contribution on children’s oral health by measuring changes in dental disease outcomes, such as the rate of dental surgery under general anesthesia and the proportion of children utilizing dental care in the communities.

Conclusion

Success with ECOH in Indigenous communities must continue to enhance culturally appropriate approaches to oral health that support both parents and children and ensure uptake. Dental worker aides are crucial to oral health promotion in First Nations communities, as they are usually from the communities, understand the local context, may speak the language, understand the culture and, in time, can become a household name in the community as the oral health educator.

Overall, COHI workers who participated in this qualitative study agreed that the COHI program delivers oral health services that result in meaningful ECC prevention and ECOH promotion in First Nations communities. Despite the favourable impact, some key issues still need to be addressed, such as improved and standardized training of workers and continuous support and capacity building in the ongoing community involvement.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Manitoba First Nations and Inuit Health Branch (FNIHB) for helping to recruit participants for this study. We acknowledge and thank participants for their time and insights.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

The Canadian Institutes of Health Research supported this work [Population Health Intervention Research Operating Grant number FRN 145125, 2016].

Authors’ contributions and statement

RJS and MM: Conceptualization, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Analysis, Writing – Original draft.

GK-A: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – Original draft, Writing – Review & Editing.

JE, PW, HTN, MB, AH, KH-S, LS, WMF, KY, OOO, MEKM, VCJ: Visualization, Writing – Original draft, Writing – Review & Editing.

The content and views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.

References

- Schroth RJ, McNally M, Harrison R, et al. Pathway to oral health equity for First Nations, Metis, and Inuit Canadians: knowledge exchange workshop. J Can Dent Assoc. 2015:f1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally M, Martin D, et al. First Nations, Inuit and Mtis health: considerations for Canadian health leaders in the wake of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada report. Healthc Manage Forum. 2017;30((2)):117–22. doi: 10.1177/0840470416680445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Early childhood caries in Indigenous communities. Pediatrics. 2011;127((6)):1190–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agnello M, Marques J, Cen L, et al, et al. Microbiome associated with severe caries in Canadian First Nations children. J Dent Res. 2017;96((12)):1378–85. doi: 10.1177/0022034517718819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathu-Muju KR, McLeod J, Walker ML, Chartier M, Harrison RL, et al. The Children’s Oral Health Initiative: an intervention to address the challenges of dental caries in early childhood in Canada’s First Nation and Inuit communities. Can J Public Health. 2016:e188–93. doi: 10.17269/cjph.107.5299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harfield SG, Davy C, McArthur A, Munn Z, Brown A, Brown N, et al. Characteristics of Indigenous primary health care service delivery models: a systematic scoping review. Global Health. 2018;14((1)):12–93. doi: 10.1186/s12992-018-0332-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavoie JG, Kornelsen D, Wylie L, et al, et al. Responding to health inequities: Indigenous health system innovations. Glob Health Epidemiol Genom. 2016 doi: 10.1017/gheg.2016.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. United Nations. 2008 Available from: https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/wp-content/uploads/sites/19/2018/11/UNDRIP_E_web.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer J, Singhal S, Ghoneim A, et al, et al. University of Toronto. Toronto(ON): 2022. Environmental scan of publicly financed dental care in Canada: 2022 update. [Google Scholar]

- Mathu-Muju KR, McLeod J, Donnelly L, Harrison R, MacEntee MI, et al. The perceptions of First Nation participants in a community oral health initiative. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2017;76((1)):1364960–93. doi: 10.1080/22423982.2017.1364960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathu-Muju KR, Kong X, Brancato C, McLeod J, Bush HM, et al. Utilization of community health workers in Canada’s Children’s Oral Health Initiative for Indigenous communities. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2018;46((2)):185–93. doi: 10.1111/cdoe.12352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyoon-Achan G, Schroth R, et al, et al. Healthy Smile, Happy Child: partnering with Manitoba First Nations and Metis communities for better early childhood oral health. AlterNative. 2021;17((2)):265–74. [Google Scholar]

- Lavoie JG, Forget EL, Prakash T, Dahl M, Martens P, O’Neil JD, et al. Have investments in on-reserve health services and initiatives promoting community control improved First Nations' health in Manitoba. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71((4)):717–24. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavoie JG, Dwyer J, et al. Implementing Indigenous community control in health care: lessons from Canada. Aust Health Rev. 2016;40((4)):453–8. doi: 10.1071/AH14101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salehyar MH, Keenan L, Patterson S, Amin M, et al. Conceptual understanding of social capital in a First Nations community: a social determinant of oral health in children. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2015:25417–8. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v74.25417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villarosa AC, Villarosa AR, Salamonson Y, et al, et al. The role of Indigenous health workers in promoting oral health during pregnancy: a scoping review. BMC Public Health. 2018;18((1)):381–8. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5281-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyoon-Achan G, Schroth RJ, Sanguins J, et al, et al. Early childhood oral health promotion for First Nations and Mtis communities and caregivers in Manitoba. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2021;41((1)):14–24. doi: 10.24095/hpcdp.41.1.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgins F, Sherriff A, Gnich W, Ross AJ, Macpherson LM, et al. The effectiveness of Dental Health Support Workers at linking families with primary care dental practices: a population-wide data linkage cohort study. BMC Oral Health. 2018;18((1)):191–24. doi: 10.1186/s12903-018-0650-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavoie JG, Phillips-Beck W, Kinew KA, Sinclair S, Kyoon-Achan G, Katz A, Policy J, et al. Is geographical isolation associated with poorer outcomes for northern Manitoba First Nation communities. Int Indig Policy J. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- Kyoon-Achan G, Lavoie J, Kinew KA, Ibrahim N, Sinclair S, Katz A, et al. What changes would Manitoba First Nations like to see in the primary healthcare they receive. Healthc Policy. 2019;15((2)):85–99. doi: 10.12927/hcpol.2019.26069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourassa C, et al. Addressing the duality of access to healthcare for Indigenous communities: racism and geographical barriers to safe care. Healthc Pap. 2018;17((3)):6–10. doi: 10.12927/hcpap.2018.25507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwynn J, Skinner J, Dimitropoulos Y, et al, et al. Community based programs to improve the oral health of Australian Indigenous adolescents: a systematic review and recommendations to guide future strategies. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20((1)):384–10. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05247-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca MA, Avenetti D, North Am, et al. Social determinants of pediatric oral health. Dent Clin North Am. 2017;61((3)):519–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2017.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cidro J, Zahayko L, Lawrence H, McGregor M, McKay K, et al. Traditional and cultural approaches to childrearing: preventing early childhood caries in Norway House Cree Nation, Manitoba. Rural Remote Health. 2014:2968–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi DL, Hopkins S, Zahlis E, et al, et al. Provider and community perspectives of dental therapists in Alaska's Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta: a qualitative programme evaluation. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2019;47((6)):502–12. doi: 10.1111/cdoe.12492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi DL, Lenaker D, Mancl L, Dunbar M, Babb M, et al. Dental therapists linked to improved dental outcomes for Alaska Native communities in the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta. J Public Health Dent. 2018;78((2)):175–82. doi: 10.1111/jphd.12263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macintosh AC, Schroth RJ, Edwards J, Harms L, Mellon B, Moffatt M, et al. The impact of community workshops on improving early childhood oral health knowledge. Pediatr Dent. 2010;32((2)):110–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis WR, Dietz WH, et al. A new framework for addressing adverse childhood and community experiences: the building community resilience model. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17((7s)) doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2016.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baydala LT, Worrell S, Fletcher F, Letendre S, Letendre L, Ruttan L, et al. “Making a place of respect”: Lessons learned in carrying out consent protocol with First Nations elders. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2013:135–43. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2013.0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]