Abstract

Patients with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-mutated non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) often develop resistance to current standard third-generation EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs); no targeted treatments are approved in the osimertinib-relapsed setting. In this open-label, dose-escalation and dose-expansion phase 1 trial, the potential for improved anti-tumor activity by combining amivantamab, an EGFR-MET bispecific antibody, with lazertinib, a third-generation EGFR TKI, was evaluated in patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC whose disease progressed on third-generation TKI monotherapy but were chemotherapy naive (CHRYSALIS cohort E). In the dose-escalation phase, the recommended phase 2 combination dose was established; in the dose-expansion phase, the primary endpoints were safety and overall response rate, and key secondary endpoints included progression-free survival and overall survival. The safety profile of amivantamab and lazertinib was generally consistent with previous experience of each agent alone, with 4% experiencing grade ≥3 events; no new safety signals were identified. In an exploratory cohort of 45 patients who were enrolled without biomarker selection, the primary endpoint of investigator-assessed overall response rate was 36% (95% confidence interval, 22–51). The median duration of response was 9.6 months, and the median progression-free survival was 4.9 months. Next-generation sequencing and immunohistochemistry analyses identified high EGFR and/or MET expression as potential predictive biomarkers of response, which will need to be validated with prospective assessment. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02609776.

Subject terms: Predictive markers, Clinical trials, Small-cell lung cancer

The combination of a bispecific antibody against EGFR and MET with a tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) in patients with TKI-relapsed, chemotherapy-naive, EGFR-mutated advanced NSCLC is safe and shows preliminary efficacy.

Main

Mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) are among the most common activating mutations in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), with exon 19 deletions (ex19del) and exon 21 L858R mutations accounting for approximately 85–90% of all cases1,2. The introduction of EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) to treat EGFR-mutant NSCLC has led to marked improvements in clinical outcomes, with response rates of 60–80%3–9. Osimertinib, a third-generation EGFR TKI, is the current standard of care for the treatment of EGFR ex19del and L858R NSCLC, with demonstrated median progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) of 18.9 months and 38.6 months, respectively9,10. Despite good initial disease control, patients nearly always develop resistance to osimertinib. Recent studies have evaluated chemotherapy plus immunotherapy and anti-angiogenic therapy in this patient population11, but no subsequent targeted therapeutic approaches without chemotherapy are approved in the osimertinib-relapsed setting.

Based on next-generation sequencing (NGS) of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) and tumor samples from patients who experience disease progression on osimertinib, identified mechanisms of resistance can be broadly divided into EGFR-dependent mechanisms (alterations preventing osimertinib inhibition of EGFR) and EGFR-independent mechanisms (activation of alternate signaling pathways or reprogramming, such as epithelial–mesenchymal transition and histologic transformations)12,13. The most prevalent EGFR-dependent mechanism of resistance to osimertinib is C797S mutation of the EGFR gene, which abrogates binding of osimertinib to the ATP binding site in the kinase domain14–16. Other EGFR-dependent resistance mechanisms that have been identified include L792X, G796X, L718Q and EGFR amplification12,13,15,17–19. Among EGFR-independent resistance mechanisms, MET amplification has been most frequently reported, with activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase or phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathways, gene fusions and histologic transformations also reported15,17–19. However, in up to 50% of patients who experience progression on osimertinib, no clear mechanism of resistance has been identified12,13.

Overcoming osimertinib resistance is further complicated by heterogeneous patterns of resistance and presence of co-occurring resistance mechanisms, which can occur even within a single patient20. Additionally, the mechanism of osimertinib resistance can be influenced by whether progression occurred in the first-line or second-line (post-EGFR TKI, T790M+) setting8,15,17–19. Given the complexity of osimertinib patterns of resistance, the inherent resistance of this population to immuno-oncology (IO) monotherapy and the lack of approved targeted therapies, current treatment guidelines recommend platinum-based chemotherapy regimens after progression on osimertinib21–23.

Amivantamab is a fully human bispecific antibody that binds to the EGFR and MET receptor to inhibit ligand binding, promote downregulation of cell surface receptors and induce Fc-dependent trogocytosis and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity24–27. Amivantamab has shown anti-tumor activity across diverse EGFR-driven and MET-driven NSCLC28,29, with a tolerable safety profile, and is approved for the treatment of patients with locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC with EGFR exon 20 insertion mutations, whose disease progressed on or after platinum-based chemotherapy28,30–32. Amivantamab, by binding extracellularly, provides a complementary mechanism to EGFR TKIs, with the combination simultaneously targeting both the extracellular and intracellular catalytic domains of EGFR. This potential for improved patient outcomes has been demonstrated in preclinical studies in the murine H1975-HGF xenograft model where greater tumor reductions and more durable disease control were observed when amivantamab was given in combination with lazertinib, a potent brain-penetrant third-generation EGFR TKI with efficacy against activating EGFR and T790M mutations, as compared to treatment with either agent alone33. Given the tolerable safety profiles of both amivantamab and lazertinib and the potential for improved anti-tumor activity, the amivantamab and lazertinib regimen was evaluated in the ongoing CHRYSALIS study, with preliminary efficacy assessed in patients with EGFR ex19del or L858R metastatic NSCLC whose disease progressed on osimertinib or another third-generation EGFR TKI but had not received cytotoxic chemotherapy in the metastatic setting (cohort E).

Results

Patients

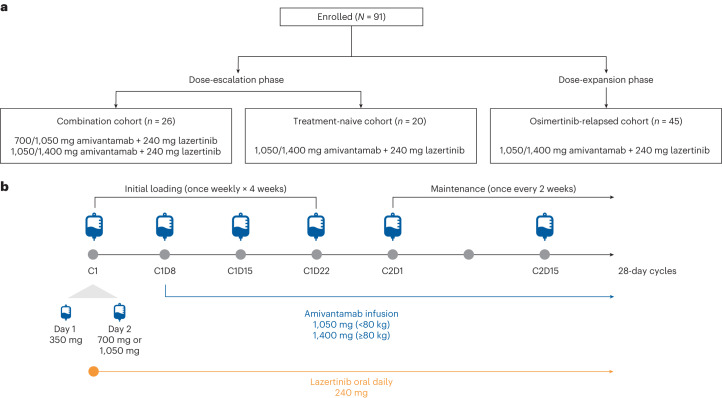

As of the data cutoff date of 19 April 2021 (enrollment start date, 3 December 2019), a total of 91 patients across three different cohorts from both the dose-escalation and dose-expansion phases of the CHRYSALIS study have received the amivantamab and lazertinib regimen (Fig. 1). In the dose-escalation phase, the combination cohort (n = 26), which was investigated only at sites in Korea, enrolled patients without restriction on prior therapies to evaluate amivantamab at an initial dose of 700 mg (1,050 mg for body weight ≥80 kg), followed by a second dose level of 1,050 mg (1,400 mg for body weight ≥80 kg) in combination with 240 mg of lazertinib. No dose-limiting toxicity was observed in the dose-escalation phase, and the recommended phase 2 combination dose (RP2CD) of 1,050 mg (1,400 mg for body weight ≥80 kg) of amivantamab + 240 mg of lazertinib was selected. After determination of the RP2CD, the Safety Evaluation Team agreed to further assess the tolerability of the RP2CD in a second cohort in Korea, which enrolled treatment-naive patients (n = 20). In parallel, the osimertinib-relapsed cohort (also known as cohort E) in the dose-expansion phase of the study enrolled patients globally whose disease had relapsed on osimertinib without intervening platinum-based chemotherapy (n = 45; Fig. 1a). The analysis presented here will focus on this osimertinib-relapsed cohort; however, the safety analysis will also include all 91 patients who received the amivantamab and lazertinib regimen in CHRYSALIS (combination cohort (n = 26), treatment-naive patients (n = 20) and the osimertinib-relapsed cohort (n = 45, also known as cohort E)). A full analysis of the other populations will be published separately.

Fig. 1. Patient flow diagram and regimen dosing schema.

a, Patient flow for the three cohorts from the dose-escalation and dose-expansion phases of CHRYSALIS. b, Dosing schema for amivantamab and lazertinib. Blue symbols indicate intravenous administration of an amivantamab dose.

The baseline patient demographics and disease characteristics for the osimertinib-relapsed cohort and all-treated population are presented in Table 1 (see Supplementary Table 1 for demographics and baseline disease characteristics for the combination cohort). In the osimertinib-relapsed cohort, the median age was 65 years (minimum–maximum, 39–85); 25 patients (56%) were women; and 19 patients (42%) were Asian. More patients harbored ex19del (69%) than L858R (31%) intrinsic mutations. Patients received a median number of two prior lines of therapy; all patients received a third-generation EGFR TKI, which was received as second-line therapy in 73% of patients. Thirteen patients (29%) had a history of brain lesions before receiving the first study dose.

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline disease characteristics

| Osimertinib-relapsed (n = 45) | All-treated population (N = 91) | |

|---|---|---|

| Median age, years (minimum–maximum) | 65 (39–85) | 61 (36–85) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 25 (56) | 52 (57) |

| Male | 20 (44) | 39 (43) |

| Race | ||

| Asian | 19 (42) | 65 (71) |

| White | 20 (44) | 20 (22) |

| Black | 2 (4) | 2 (2) |

| Multiple/not reported | 4 (9) | 4 (4) |

| ECOG PS | ||

| 0 | 12 (27) | 29 (32) |

| 1 | 33 (73) | 62 (68) |

| History of smoking | ||

| Yes | 20 (44) | 41 (45) |

| No | 25 (56) | 50 (55) |

| Median time from initial diagnosis to first dose, months (minimum–maximum) | 32 (5–98) | 24 (1–98) |

| Location of metastasesa | ||

| Lymph node | 18 (40) | 44 (48) |

| Bone | 19 (42) | 31 (34) |

| Brain | 13 (29) | 30 (33) |

| Liver | 8 (18) | 10 (11) |

| Adrenal gland | 4 (9) | 4 (4) |

| Other/not reported | 22 (49) | 47 (52) |

| Median prior lines of therapy (minimum–maximum) | 2 (1–4) | 2 (0–9) |

| EGFR primary mutation | ||

| Exon 19 deletion | 30 (67) | — |

| Exon 21 L858R | 14 (31) | — |

| Unknown | 1 (2) | — |

| Prior systemic therapy | 45 (100) | — |

| Platinum-based chemotherapyb | 7 (16) | 18 (20) |

| EGFR TKIa | ||

| 1st or 2nd generation | 33 (73) | 54 (59) |

| 3rd generation | 45 (100) | 53 (58) |

| Received as 1st line | 12 (27) | — |

| Received as 2nd line | 33 (73) | — |

| No prior therapy | 0 | 23 (25) |

Data are number of patients (%) unless otherwise noted.

aPatients could be counted in more than one category.

bSeven patients had limited platinum exposure (<two cycles) given before first EGFR TKI in the osimertinib-relapsed group.

Safety

At the 19 April 2021 data cutoff, the median duration of follow-up was 11.1 months (minimum–maximum, 1.0–15.0) for the osimertinib-relapsed cohort and 13.3 months (minimum–maximum, 0.5–23.7) for the all-treated population. The safety profile of the amivantamab and lazertinib regimen was similar in both of these cohorts and generally similar to safety previously described for amivantamab at its recommended phase 2 dose (RP2D) (ref. 31). Adverse events (AEs) reported in the dose-escalation combination cohort are presented in Supplementary Table 2.

In the osimertinib-relapsed cohort, rash-related AEs occurred in 36 patients (80%), with two patients (4%) experiencing grade ≥3 events (Table 2). Infusion-related reaction (IRR) was reported in 35 patients (78%) who all had events of grade 1 or 2 severity. IRRs occurred with the initial infusion on cycle 1, day 1 and did not lead to treatment discontinuations. Other frequently reported AEs were consistent with on-target anti-EGFR and anti-MET activity. AEs traditionally associated with EGFR inhibition included paronychia in 22 patients (49%), pruritus in 14 patients (31%), stomatitis in 12 patients (27%) and diarrhea in 10 patients (22%) (Table 2). AEs traditionally associated with MET inhibition of hypoalbuminemia and edema occurred in 17 patients (38%) each (Table 2). AEs of grade ≥3 severity were reported in 25 patients (56%), with seven patients (16%) experiencing grade ≥3 AEs that were considered to be treatment related (related to either or both amivantamab and lazertinib). The most common treatment-related grade ≥3 AEs were increased alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and paronychia, both reported in two patients (4%) each; both increased ALT events were resolved without treatment discontinuation. Serious AEs occurred in 17 patients (38%), of whom two (4%; one pneumonitis and one dermatitis) had events that were considered to be treatment related. Treatment-related AEs that led to dose reduction and treatment discontinuation of any study agent occurred in eight patients (18%; one increased ALT, one increased aspartate aminotransferase (AST), one headache, three paronychia, two rash and three dermatitis acneiform) and two patients (4%; one pneumonitis and one dermatitis), respectively. Treatment-related dose interruptions of any study agent occurred in 12 patients (27%). In one patient with worsening dyspnea, an unscheduled computed tomography scan at 4 weeks documented grade 3 pneumonitis in the setting of rapidly progressive disease (PD) in the left lung. Given the disease burden, the patient was not a candidate for intubation and died shortly after presentation, with death attributed to both PD and pneumonitis. Overall, no increased risk of pneumonitis or new safety signals were identified.

Table 2.

Adverse events

| Adverse events (≥10%), n (%) | Osimertinib-relapsed (n = 45) | All-treated (N = 91) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All-grade | Grade ≥3 | All-grade | Grade ≥3 | |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | ||||

| Rasha | 36 (80) | 2 (4) | 81 (89) | 6 (7) |

| Pruritus | 14 (31) | 0 | 31 (34) | 0 |

| Dry skin | 13 (29) | 0 | 16 (18) | 0 |

| Skin fissures | 7 (16) | 0 | 8 (9) | 0 |

| General disorders and administration-site conditions | ||||

| Infusion-related reaction | 35 (78) | 0 | 60 (66) | 1 (1) |

| Edemab | 17 (38) | 0 | 25 (27) | 0 |

| Fatiguec | 12 (27) | 0 | 21 (23) | 1 (1) |

| Pyrexia | 6 (13) | 0 | 12 (13) | 0 |

| Infections and infestations | ||||

| Paronychia | 22 (49) | 2 (4) | 58 (64) | 4 (4) |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | ||||

| Hypoalbuminemia | 17 (38) | 1 (2) | 42 (46) | 4 (4) |

| Decreased appetite | 6 (13) | 0 | 19 (21) | 0 |

| Hypocalcemia | 9 (20) | 0 | 14 (15) | 1 (1) |

| Hypomagnesemia | 6 (13) | 0 | 9 (10) | 0 |

| Hyponatremia | 5 (11) | 1 (2) | 8 (9) | 4 (4) |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | ||||

| Musculoskeletal paind | 19 (42) | 1 (2) | 39 (43) | 1 (1) |

| Muscle spasms | 5 (11) | 0 | 8 (9) | 0 |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | ||||

| Stomatitise | 12 (27) | 0 | 34 (37) | 0 |

| Nausea | 20 (44) | 0 | 28 (31) | 1 (1) |

| Constipation | 12 (27) | 0 | 19 (21) | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 10 (22) | 0 | 17 (19) | 1 (1) |

| Dyspepsia | 3 (7) | 0 | 12 (13) | 0 |

| Vomiting | 9 (20) | 0 | 10 (11) | 0 |

| Investigations | ||||

| Increased ALT | 8 (18) | 2 (4) | 29 (32) | 5 (5) |

| Increased AST | 10 (22) | 0 | 26 (29) | 2 (2) |

| Increased blood alkaline phosphatase | 5 (11) | 0 | 6 (7) | 0 |

| Nervous system disorders | ||||

| Paresthesia | 5 (11) | 0 | 23 (25) | 0 |

| Dizziness | 10 (22) | 0 | 19 (21) | 0 |

| Headachef | 9 (20) | 1 (2) | 11 (12) | 1 (1) |

| Respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders | ||||

| Dyspneag | 11 (24) | 3 (7) | 15 (16) | 4 (4) |

| Pulmonary embolism | 4 (9) | 3 (7) | 11 (12) | 3 (3) |

| Coughh | 4 (9) | 0 | 10 (11) | 0 |

| Vascular disorders | ||||

| Hemorrhagei | 6 (13) | 0 | 10 (11) | 0 |

| Hypotension | 5 (11) | 0 | 6 (7) | 0 |

| Blood and lymphatic system disorders | ||||

| Thrombocytopenia | 6 (13) | 0 | 8 (9) | 0 |

| Psychiatric disorders | ||||

| Anxiety | 5 (11) | 0 | 5 (5) | 0 |

aRash includes acne, dermatitis, dermatitis acneiform, eczema, eczema asteatotic, palmar–plantar erythrodysesthesia syndrome, perineal rash, rash, rash erythematous, rash maculo-papular, rash papular, rash vesicular, skin exfoliation and toxic epidermal necrolysis.

bEdema includes eyelid edema, face edema, generalized edema, lip edema, edema, edema peripheral, periorbital edema and peripheral swelling.

cFatigue includes asthenia and fatigue.

dMusculoskeletal pain includes arthralgia, arthritis, back pain, bone pain, musculoskeletal chest pain, musculoskeletal discomfort, musculoskeletal pain, myalgia, neck pain, non-cardiac chest pain, pain in extremity and spinal pain.

eStomatitis includes aphthous ulcer, cheilitis, glossitis, mouth ulceration, mucosal inflammation, pharyngeal inflammation and stomatitis.

fHeadache includes headache and migraine.

gDyspnea includes dypsnea and dyspnea exertional.

hCough includes cough, productive cough and upper airway cough syndrome.

iHemorrhage includes epistaxis, gingival bleeding, hematuria, hemoptysis, hemorrhage, mouth hemorrhage and mucosal hemorrhage.

Efficacy

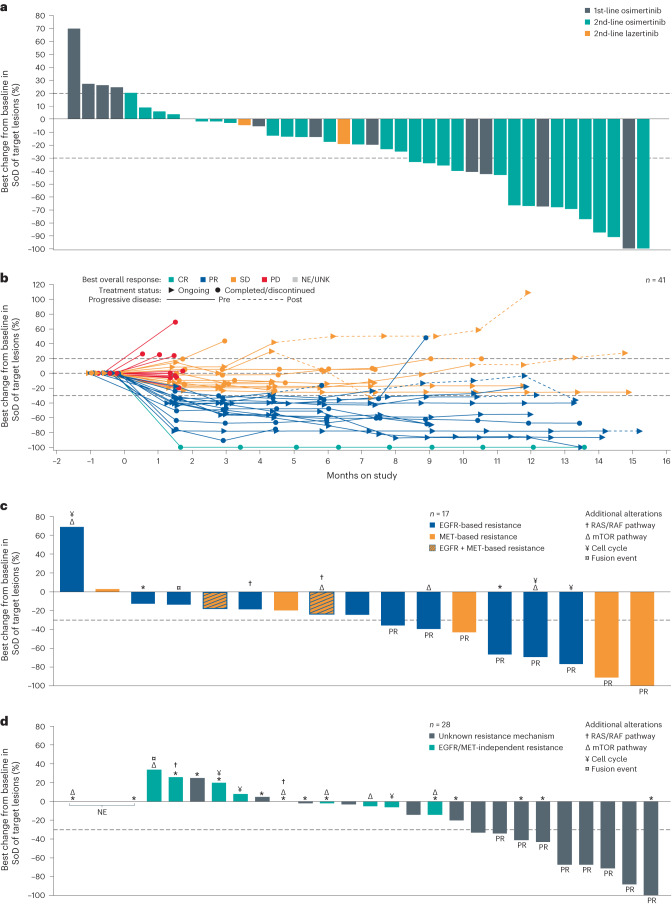

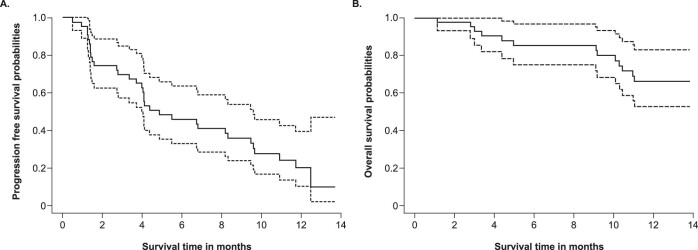

At a median follow-up of 11.1 months, the investigator-assessed overall response rate (ORR) in the osimertinib-relapsed cohort was 36% (95% confidence interval (CI), 22–51) with one complete response (CR) and 15 partial responses (PRs) (Table 3). ORRs were similar between patients who had received osimertinib as either first-line or second-line therapy (ORR of 33% (95% CI, 10–65) and 36% (95% CI, 21–55), respectively; Fig. 2a). For patients with EGFR ex19 del (n = 30) or L858R (n = 14), the ORR was 33% (95% CI, 17–53) and 43% (95% CI, 18–71), respectively. Most responses (14/16) were observed at the first disease assessment at 6 weeks. The median duration of response was 9.6 months (95% CI, 5.3–not calculable (NC)), with 11 patients (69%) achieving responses lasting ≥6 months (Fig. 2b). The clinical benefit rate (CBR), defined as CR, PR or stable disease (SD) for ≥11 weeks, was 64% (95% CI, 49–78). The median PFS was 4.9 months (95% CI, 3.7–9.5); for patients who had received osimertinib as either first-line or second-line therapy, median PFS was 6.8 months and 2.9 months, respectively (Extended Data Fig. 1a). Median OS was NC (Extended Data Fig. 1b). In total, three patients had documented central nervous system (CNS) progression, two with new lesions and one with progression of an existing lesion.

Table 3.

Investigator-assessed response per RECIST

| Osimertinib-relapsed (n = 45) | |

|---|---|

| ORRa (95% CI) | 36% (22–51) |

| CBRb (95% CI) | 64% (49–78) |

| Best response, n (%) | |

| CR | 1 (2) |

| PR | 15 (33) |

| SD | 14 (31) |

| PD | 11 (24) |

| NE | 4 (9) |

| mDOR, months (95% CI) | 9.6 (5.3–NC) |

| mPFS, months (95% CI) | 4.9 (3.7–9.5) |

| mOS, months (95% CI) | NC |

aProportion of patients who had CRs or PRs.

bProportion of patients who had CRs or PRs or SD for ≥11 weeks (corresponding to two disease assessments).

mDOR, median duration of response; mOS, median overall survival; mPFS, median progression-free survival; NE, not evaluable.

Fig. 2. Anti-tumor activity of amivantamab + lazertinib combination in part 2 expansion cohort E: osimertinib-relapsed NSCLC with common EGFR mutations (panels a and b) and among patients with and without identified EGFR-based and/or MET-based resistance (panels c and d).

a, Waterfall plot displaying best percent change from baseline in sum of lesion diameters among patients enrolled in the osimertinib-relapsed cohort by receipt of osimertinib/lazertinib as first-line (yellow) or second-line (blue/green) therapy. Teal bars denote patients who received the third-generation EGFR TKI lazertinib instead of osimertinib. Four patients did not have any post-baseline disease assessments and are not included in the plot. b, Spider plot displaying percent change from baseline in sum of diameters of target lesions over time in patients enrolled in the osimertinib-relapsed cohort. Best response of CR (green), PR (blue), SD (orange) and PD (red) are indicated. Gray lines represent patients who were not evaluable (NE). Four patients did not have any post-baseline disease assessments and are not included in the plot. c, Waterfall plot displaying best percent change from baseline in sum of diameters of target lesions among 17 patients with identified EGFR-based and MET-based osimertinib resistance mechanisms. d, Waterfall plot displaying best percent change from baseline in sum of diameters of target lesions among 28 patients with unknown or EGFR-independent and MET-independent osimertinib resistance mechanisms identified by NGS. Additional alterations identified in each patient are indicated by the symbols. Asterisks denote patients who did not have tumor NGS. SoD, sum of diameters; UNK, unknown.

Extended Data Fig. 1. (A) PFS and (B) OS K-M Curve.

In both K-M curves, the dotted lines represent the 95% confidence intervals. K-M, Kaplan-Meier; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression free survival.

Biomarker analyses

Given the known heterogeneity of osimertinib resistance, NGS was used to better understand tumor response to the amivantamab and lazertinib regimen and to explore potential biomarkers predictive of response in the osimertinib-relapsed cohort. Patient ctDNA and tumor tissue were available for NGS analysis in 44 of 45 patients and 29 of 45 patients, respectively. Genetic testing of these samples identified 17 patients (38%) who had EGFR-based and/or MET-based osimertinib resistance mutations or amplifications (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Table 3). Associated biomarker data for all 45 patients are provided in Supplementary Table 4. The most frequent alterations identified were EGFR C797S (n = 7; all cis); MET amplification (n = 5), with copy number variation (CNV) of 3, 4 (n = 2), 7 and 31; EGFR amplification (n = 3), with CNV of 8, 14 and 37; and EGFR L718X (n = 3) (Supplementary Table 3). Seven of these patients harbored more complex, heterogeneous alterations comprising both EGFR- and/or MET-dependent and -independent resistance mechanisms, including alterations in PIK3CA, KRAS and components of the cell cycle machinery. One patient harbored an FGFR3–TACC3 fusion in addition to an EGFR C797S mutation.

Among the 17 patients with EGFR-based and/or MET-based osimertinib resistance, eight achieved a response based on investigator assessment for an ORR of 47% (95% CI, 23–72), with a median duration of response of 10.4 months (95% CI, 2.7–NC). The CBR was 82% (95% CI, 57–96), and the median PFS was 6.7 months (95% CI, 3.4–12.5) (Supplementary Table 5). Three of five patients (60%) who were observed to have MET amplification after progression on osimertinib had confirmed responses to the amivantamab and lazertinib regimen, including one patient with a CR (Supplementary Table 6). Different response patterns were observed depending on the co-occurring EGFR/MET-independent resistance mechanisms, with responses observed in two of three patients with concurrent PIK3CA alterations and two of three patients with concurrent alterations in cell cycle machinery. Responses were not observed in patients with concurrent KRAS alterations or in the patient with an FGFR–TACC3 fusion (Supplementary Table 6).

Of the remaining 28 patients who did not have an identified EGFR-based and/or MET-based osimertinib resistance mechanism, 18 had unknown mechanisms (of these, one had neither tissue nor ctDNA and 13 had ctDNA testing but no tumor testing), and 10 had EGFR-independent and/or MET-independent resistance mechanisms, such as alterations in PIK3CA, KRAS and PTEN, and mutations in cell cycle genes, identified by NGS (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Table 7). The investigator-assessed ORR in this subgroup of patients was 29% (95% CI, 13–49), with eight of 28 patients achieving responses. The median duration of response was 8.3 months (95% CI, 2.6–NC). The CBR was 54% (95% CI, 34–73), and the median PFS was 4.1 months (95% CI, 1.4–9.5) (Supplementary Table 5). Among the 18 patients with unknown mechanisms of resistance, the ORR was 44% (95% CI, 22–69), and, among the 10 patients with EGFR-independent and/or MET-independent resistance mechanisms, no patient achieved a response. Of note, all eight patients who had a PR had unknown mechanisms of osimertinib resistance by NGS.

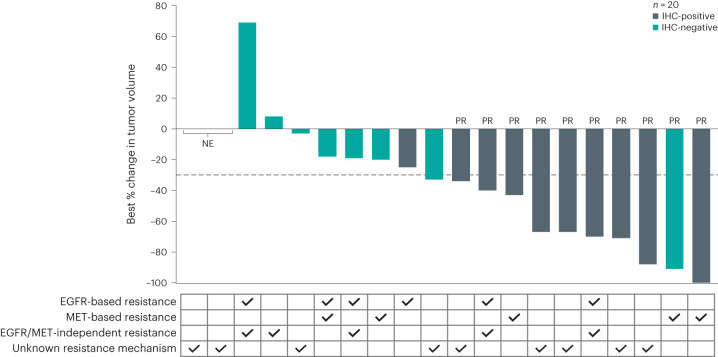

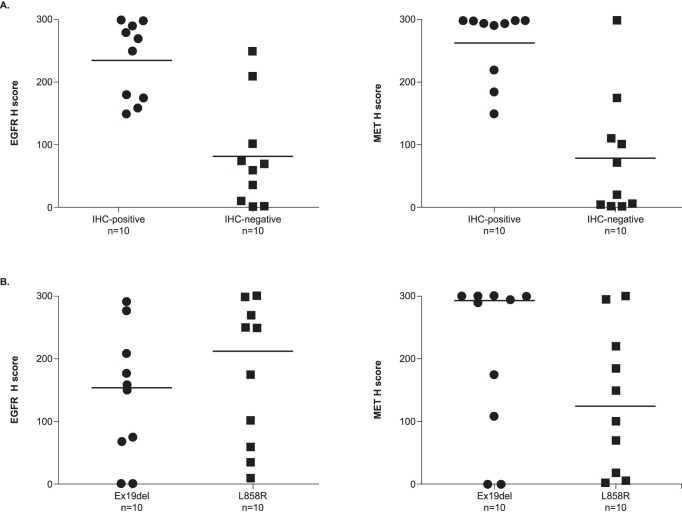

In addition to NGS, an immunohistochemistry (IHC)-based approach was undertaken in patients with sufficient remaining tumor samples (n = 20) to explore the association of EGFR and MET expression with tumor response. Representative images of IHC staining are provided in the supplement. By IHC testing, 10 patients were identified as having a combined H-score ≥400, up to a maximum 600 (referred to hereafter as ‘IHC-positive’) for EGFR and/or MET expression (Fig. 3). All patients who were IHC-positive had an H-score ≥150, of a maximum of 300, for both EGFR and MET. The average EGFR H-score in IHC-positive patients was 235, whereas the average in IHC-negative patients was 82. Similarly, average MET H-score in IHC-positive patients was 264 but only 78 in IHC-negative patients; breakdown by mutation type is also provided (Extended Data Fig. 2). Of the 20 patients included in this analysis, 10 had a confirmed PR (Fig. 3). In the 10 patients who were IHC-positive, nine had PRs, for an ORR of 90% (95% CI, 56–100) and a median duration of response of 9.7 months (95% CI, 2.6–NC). The CBR was 100% (95% CI, 69–100), and the median PFS was 12.5 months (95% CI, 4.0–NC) (Supplementary Table 5). Among the 10 patients who were IHC-negative, only one achieved a PR, for an ORR of 10% (95% CI, 0.3–45) and a duration of response of 2.7 months (95% CI, NC). The CBR was 50% (95% CI, 19–81), and the median PFS was 4.0 months (95% CI, 1.4–4.4). Although NGS has its utility, the IHC-positive cohort seemed to additionally identify a disparate patient population from NGS testing—responders who were IHC-positive included patients with genetic EGFR- and/or MET-dependent and -independent resistance as well as those with unknown resistance mechanism by NGS (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Anti-tumor activity in patients by IHC expression analysis and NGS-identified osimertinib resistance mechanisms.

Waterfall plot displaying best percent change from baseline in sum of diameters of target lesions among 20 patients who had tumor samples available for exploratory analysis using IHC staining for EGFR and MET expression. IHC-positive patients had combined EGFR and MET H-scores ≥400, and IHC-negative patients had combined EGFR and MET H-scores <400. The table below the waterfall plot indicates the type of resistance mechanism identified using NGS. Patients with both EGFR-based and EGFR/MET-independent resistance are categorized as having EGFR-based resistance (Fig. 2a).

Extended Data Fig. 2. Distribution of EGFR and MET H-Scores by (A) IHC status or (B) EGFR mutation type.

In each set of data points, the middle bar represents the mean. EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; Ex19del, Exon 19 deletion; IHC, immunohistochemistry.

Discussion

Patients with EGFR ex19del and L858R mutations receive osimertinib as part of standard-of-care therapy, in either the first-line or second-line setting; upon progression after osimertinib, the standard of care is platinum-based chemotherapy. Furthermore, salvage therapy with docetaxel after chemotherapy offers an ORR of only 14% (ref. 34), highlighting the need for additional therapies that can prolong disease control. Amivantamab’s mode of action, initiated through binding to the extracellular domain of EGFR and MET receptors, has the potential to target both EGFR-dependent and MET-dependent mechanisms of osimertinib resistance and, also in concert with tyrosine kinase inhibition by lazertinib, may lead to more potent inhibition of EGFR oncogenic signaling. The combination of TKIs targeting EGFR (osimertinib) and MET (savolitinib or tepotinib) in this patient population has similarly shown the benefit of targeting these pathways in EGFR-mutant NSCLC35,36.

Overall, the safety profile of the amivantamab and lazertinib regimen was tolerable and generally consistent with previous monotherapy experience of amivantamab31,37, demonstrating that the favorable safety profile of lazertinib enables combination with amivantamab. Among all patients treated with the amivantamab and lazertinib regimen, the most commonly reported toxicities were rash (89%) and IRRs (66%); the incidence of rash was higher than that previously reported with amivantamab (78%) or lazertinib monotherapy (37%) (refs. 31,38). Most on-target toxicities were of grade 1 or 2 severity, with low rates of grade ≥3 rash (7%) and diarrhea (1%) reported. There was no evidence of increased risk of pneumonitis, and no new safety signals were identified.

In the osimertinib-relapsed cohort, which was enrolled without biomarker selection, the investigator-assessed ORR was 36%, with anti-tumor activity observed in patients whose disease progressed after osimertinib therapy in the first-line or second-line setting. Furthermore, the median PFS was 4.9 months, which is similar to that observed with standard-of-care platinum-based chemotherapy39. In this population, the ORR for those with EGFR ex19 del (33%) and L858R (43%) was roughly numerically equivalent. Exploratory analysis by NGS identified EGFR-based and MET-based resistance mechanisms as potential biomarkers for response. However, half of the responders had unknown mechanisms of resistance or lower sensitivity in ctDNA (there were eight unknown responders; five of eight had both ctDNA and tumor NGS performed, and three of eight had ctDNA only), suggesting that reliance on NGS alone could potentially miss patients who might benefit from the amivantamab and lazertinib regimen. An exploratory IHC-based approach showed a potential association between high EGFR and/or MET expression and response to the amivantamab and lazertinib regimen. Retrospective IHC-based analysis appeared to have a stronger correlation with response than NGS, identifying responders who had EGFR- and/or MET-dependent and -independent resistance mechanisms as well as those who had mechanisms that were unknown. Notably, five of the nine responders did not have a clear genetic resistance mechanism, suggesting that IHC testing may identify potential responders despite the absence of an identifiable genetic resistance mechanism. Among the 16 responders in the osimertinib-relapsed cohort, eight had EGFR-based and/or MET-based resistance, and eight did not have resistance mechanisms identified through NGS, suggesting that at least some of the tumors with unknown resistance may reflect non-genetic mechanisms leading to TKI resistance but continued sensitivity to EGFR-directed and MET-directed inhibition by the combined action of amivantamab and lazertinib or the immune-based anti-tumor effects of amivantamab. Although promising, it should be noted that the H-score cutoffs for the determination of IHC-positive patients were determined retrospectively, and these potential biomarker strategies are being prospectively explored in the ongoing phase 1/1b CHRYSALIS-2 study (NCT04077463).

This study needs to be interpreted within its limitations. As a non-randomized, single-arm trial with no control arm, interpretation of the data requires historical comparison within the literature or with real-world evidence. The limited sample size of the study leads to lower-than-desired precision, which can impact interpretation and extrapolation. Additionally, the data presented here are not generalizable to all patients who progressed on osimertinib because the study enrolled only those who were also chemotherapy naive. Long-term safety of the amivantamab and lazertinib combination therapy may not be fully captured with the follow-up period explored in this study. Data with longer follow-up (median follow-up of 33.5 months) from this same study and combination in the front-line setting were recently presented, and the safety profile was consistent with previous reports40. Additionally, the ongoing phase 3 trials (MARIPOSA (NCT04487080), MARIPOSA-2 (NCT04988295) and PALOMA-3 (NCT05388669)) will provide a more comprehensive long-term representation of the safety of amivantamab and lazertinib combination therapy.

The activity of the combination after disease progression on or after osimertinib suggests that dual blockade of EGFR and MET by amivantamab can potentiate the initial anti-EGFR activity of lazertinib and may delay development of resistance through EGFR secondary resistance mutations and MET bypass pathways41, although direct comparison with single-agent lazertinib was not performed in this phase 1 trial. Additional studies to corroborate the results are currently underway. The CHRYSALIS-2 study (NCT04077463) is evaluating the amivantamab and lazertinib regimen in the post-platinum-based chemotherapy/post-osimertinib setting, with results demonstrating a consistent level of anti-tumor activity (ORR = 33% by blinded independent central review, with duration of response of 9.6 months)42, suggesting similar efficacy as observed in this current analysis. Similarly to this analysis, cohort D of the CHRYSALIS-2 study (NCT04077463) is investigating potential biomarker strategies and evaluating the amivantamab and lazertinib regimen in the post-osimertinib and chemotherapy-naive setting. In conclusion, the amivantamab and lazertinib regimen showed durable clinical activity in the osimertinib-relapsed setting, consistent with preclinical studies, suggesting improved anti-EGFR activity in osimertinib-resistant models. Exploratory NGS and IHC-based analyses suggest that these may represent biomarker strategies with the potential to enrich for a population of patients who are more likely to respond to the amivantamab and lazertinib regimen, and efforts to confirm these exploratory findings are ongoing.

Methods

Study design

CHRYSALIS is an ongoing, first-in-human, open-label, multicenter, dose-escalation (part 1) and dose-expansion (part 2) phase 1 study of amivantamab as monotherapy and as combination therapy in patients with advanced NSCLC (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02609776). Details on the monotherapy study design were previously described31. For the amivantamab and lazertinib regimen (Fig. 1b), eligible patients had Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) ≤1 and metastatic or unresectable NSCLC that was positive for EGFR ex19del or exon 21 L858R mutation based on local or central testing of ctDNA or tumor. For part 2, additional eligibility criteria included measurable disease according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) and disease that progressed after first-line or second-line treatment with a third-generation EGFR TKI (referred to as the osimertinib-relapsed cohort; previous progression on lazertinib was not exclusionary). Key exclusion criteria included previous treatment with anti-cancer immunotherapy for patients enrolled in the treatment-naive cohort and any previous treatment in the metastatic setting with therapy other than a first-generation, second-generation or third-generation EGFR TKI for the osimertinib-relapsed cohort (fewer than two cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy administered before the first EGFR TKI was allowed). Patients with untreated or asymptomatic brain metastases smaller than 1 cm in diameter at screening were eligible.

Part 1 dose escalation was implemented using a 3 + 3 design. Dosing was initiated at a dose level below the RP2D of amivantamab (700 mg for body weight <80 kg and 1,050 mg for body weight ≥80 kg) in combination with the RP2D of lazertinib (240 mg) and escalated to a second dose level of 1,050 mg of amivantamab for body weight <80 kg and 1,400 mg for body weight ≥80 kg in combination with 240 mg of lazertinib. Amivantamab was administered intravenously weekly during cycle 1 (28-d cycle) and then every other week thereafter. The first dose of amivantamab was split over 2 d, with 350 mg given on cycle 1, day 1 and the remainder of the full dose given on cycle 1, day 2. Lazertinib was given orally daily. The primary objective for part 1 was to determine the RP2CD. The primary objectives for part 2 were to evaluate the safety, tolerability and anti-tumor activity (ORR) of the amivantamab and lazertinib regimen at the RP2CD. Key secondary objectives included assessment of the clinical benefit, PFS and OS of the amivantamab and lazertinib regimen, and exploratory objectives included exploration of biomarkers predictive of clinical response from blood and tumor tissue.

Doses of amivantamab were administered intravenously once weekly for the first 4 weeks and then every other week for week 5 and beyond (Fig. 1b). To mitigate IRRs, the initial dose of amivantamab was given as a split dose of 350 mg on day 1 and the remainder of the dose on day 2. Lazertinib was given orally daily and before initiation of amivantamab infusion on days when amivantamab was also administered (Fig. 1b). Monitoring for IRRs during the initial dose and proactive infusion modifications were implemented to help mitigate IRRs31,43. Treatment continued until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity or withdrawal of consent. Treatment beyond RECIST-defined disease progression was allowed in cases of continued clinical benefit. Management of rash was recommended per protocol or in accordance with institutional guidelines31. The study was approved by institutional review boards at participating sites (Supplementary Table 8), and all patients provided written informed consent. The study was conducted in accordance with current International Council for Harmonization guidelines on Good Clinical Practice, consistent with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Sex/gender was determined based on self-report.

Study assessments

Disease was assessed by the investigator using computed tomography scans of the chest, abdomen, pelvis and any other disease location performed with intravenous contrast. Baseline brain magnetic resonance imaging was required at screening for patients enrolled in the dose-expansion cohort. Monitoring for CNS disease was performed in accordance with local practice. Tumor response was assessed by the investigator using RECIST version 1.1. AEs were graded according to National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.03.

Statistical analysis

The data cutoff date for this analysis was 19 April 2021. The protocol-defined final analysis for the osimertinib-relapsed cohort was to occur after enrollment of 100 patients; however, guidance from health authorities limited enrollment to 45 patients for this first-in-human study, which was opened under a single-agent investigational new drug (IND). Under the direction of health authorities, CHRYSALIS-2 (NCT04077463) was opened under a combination IND, which allowed for the recruitment of a larger patient population. Therefore, the analysis presented here is a final exploratory analysis that includes the 45 patients who were enrolled in the osimertinib-relapsed cohort (also known as cohort E). The safety population included patients who were treated with the amivantamab and lazertinib regimen across both parts of the study (patients from all three cohorts; Fig. 1a). The efficacy population for each cohort included patients who were treated with the amivantamab and lazertinib regimen and had at least two scheduled post-baseline disease assessments or had discontinued treatment for any reason.

ORR was calculated as the proportion of patients in the efficacy population who achieved CR or PR as assessed by the investigator using RECIST version 1.1. The null hypothesis for cohort E was ORR ≤25%, and the alternative hypothesis was ORR ≥40%. A sample size of 100 response-evaluable patients, assuming a non-evaluable rate of 10%, was needed for a power of 85% and a one-sided alpha of 2.5%; however, because the study stopped enrollment prematurely, hypothesis testing was not performed. CBR was calculated as the proportion of patients achieving CR or PR or SD for ≥11 weeks, corresponding to two disease assessments.

Data were summarized using descriptive statistics. Observed ORR and CBR are presented along with their two-sided 95% CIs. The 95% CIs were calculated using log transformation, assuming the log (survival rate) is a normal distribution. Time to event endpoints were summarized using Kaplan–Meier estimates and presented with their corresponding 95% CIs.

Biomarker analyses

NGS of pre-treatment tumor biopsies and plasma ctDNA were performed to elucidate the landscape of genomic alterations in patient tumors. Plasma samples were collected prospectively, before treatment, and were analyzed with Guardant360 (Guardant Health). Tumor biopsies were collected after progression on last anti-cancer therapy and before treatment with the amivantamab and lazertinib regimen. Tumor biopsy NGS was performed with the Oncomine Dx Target Test (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Expression of EGFR and MET on available patient tumor samples was measured by IHC analysis of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumor tissue collected after progression on last anti-cancer therapy and before treatment with the amivantamab and lazertinib regimen. Staining for MET was performed with the anti-MET rabbit monoclonal antibody SP44; samples were run on the Dako Link 48 autostainer with FLEX detection. Staining for EGFR was performed with the anti-EGFR rabbit monoclonal antibody D38B1. Tumor cell staining was determined by the H-score method, as previously described44. IHC analysis was performed at Mosaic Laboratories. IHC-positive was defined as having a combined H-score >400 based on a response operator curve analysis revealing that the combined H-score of 400 was found to optimize both sensitivity and specificity for predicting response to amivantamab and lazertinib combination therapy. Individual H-scores for each receptor (EGFR and MET) were also evaluated; a score of 150 for each receptor indicated that it was probably driven by relatively high H-scores of both receptors rather than predominantly by a high H-score of one receptor but not the other. These H-score cutoffs were derived retrospectively and based on the approaches of previous studies45–47; prospective clinical validation of this cutoff is required and is currently underway.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Online content

Any methods, additional references, Nature Portfolio reporting summaries, source data, extended data, supplementary information, acknowledgements, peer review information; details of author contributions and competing interests; and statements of data and code availability are available at 10.1038/s41591-023-02554-7.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Tables 1–8 and representative images of IHC staining panels a and b.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients who participated in the study and their families and caregivers; the physicians and nurses who cared for patients and supported this trial; and the staff members at the study sites and those involved in data collection and analyses. This clinical study was funded by Janssen R&D. Medical writing support was funded by Janssen Global Services and provided by T. T. Cao (Janssen Global Services) and Lumanity Communications.

Extended data

Author contributions

Conceptualization: J.-Y.H., S.-H.I.O., D.W.K., J.C.C., J.M.B., R.E.K., A.R., M.T., B.C.C., E.B.H., K.P. and S.W.K. Formal analysis: J.C.C., J.X., G.G. and K.P. Data curation: S.-H.I.O., P.L., K.P. and M.N. Methodology: J.X., G.G., B.C.C. and K.P. Writing: all authors.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Medicine thanks Ernest Nadal, Shengxiang Ren, Andrew Gray, Tony Mok and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary handling editors: Ulrike Harjes and Saheli Sadanand, in collaboration with the Nature Medicine team.

Data availability

Janssen has an agreement with the Yale Open Data Access (YODA) project to serve as the independent review panel for the evaluation of requests for clinical study reports and participant-level data from investigators and physicians for scientific research that will advance medical knowledge and public health. The project does not support requests to use data for non-scientific purposes, such as in pursuit of litigation or for commercial interests. Data will be made available after publication and approval by YODA of any formal requests with a defined analysis plan. For more information on this process or to make a request, visit the YODA project site at http://yoda.yale.edu (median response time for inquiries is 15 d). The data-sharing policy of Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson is available at https://www.janssen.com/clinical-trials/transparency.

Competing interests

B.C.C.: consulting or advisory role (Novartis, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche, Bristol Myers Squibb, Ono Pharmaceutical, Yuhan, Pfizer, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Takeda, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Medpacto, Blueprint Medicines, KANAPH Therapeutics, BridgeBio, Cyrus Therapeutics, Guardant Health and Oscotec); board of directors (Interpark Bio Convergence and J INTS BIO); research funding (Novartis, Bayer, AstraZeneca, MOGAM Institute, Dong-A ST, Champions Oncology, Janssen, Yuhan, Ono Pharmaceutical, Dizal Pharma, Merck Sharp & Dohme, AbbVie, Medpacto, GI Innovation, Eli Lilly, Blueprint Medicines and Interpark Bio Convergence); royalties (Champions Oncology); stock ownership (TheraCanVac, Gencurix, BridgeBio, KANAPH Therapeutics, Cyrus Therapeutics, Interpark Bio Convergence and J INTS BIO); founder (DAAN Biotherapeutics). D.-W.K.: travel, accommodations and expenses (Daiichi Sankyo and Amgen); research funding to institution (Alpha Biopharma, AstraZeneca/MedImmune, Hanmi, Janssen, Merus, Mirati Therapeutics, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Ono Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Roche/Genentech, Takeda, TP Therapeutics, Xcovery, Yuhan, Boehringer Ingelheim, Amgen and Daiichi Sankyo). A.I.S.: consulting or advisory role (Incyte, Amgen, Novartis, AstraZeneca/MedImmune, Mirati Therapeutics, Gritstone Oncology, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Takeda and Janssen); consulting or advisory role for institution (Array BioPharma, AstraZeneca/MedImmune, Merck and Bristol Myers Squibb); stock ownership (Eli Lilly); honoraria (CytomX Therapeutics, AstraZeneca/MedImmune, Merck, Takeda, Amgen, Janssen, Novartis, Bristol Myers Squibb and Bayer); research funding (LAM Therapeutics); research funding to institution (Roche, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Astellas Pharma, MedImmune, Novartis, Newlink Genetics, Incyte, AbbVie, Ignyta, LAM Therapeutics, Trovagene, Takeda, Macrogenics, CytomX Therapeutics, Astex Pharmaceuticals, Bristol Myers Squibb, LOXO Oncology, Arch Therapeutics, Gritstone Oncology, Plexxikon, Amgen, Daiichi Sankyo, ADC Therapeutics, Janssen, Mirati Therapeutics, Rubius and Synthekine); leadership role for institution (NEXT Oncology Virginia). J.E.G.: consulting or advisory role (AstraZeneca and Atara Biotherapeutics); honoraria (Bristol Myers Squibb and Celgene); speakers’ bureau (Bristol Myers Squibb); research funding to institution (Janssen); travel, accommodations and expenses (Atara Biotherapeutics, Bristol Myers Squibb and Celgene). E.B.H.: consulting or advisory role (Janssen, Revolution Medicines, and Ellipses Pharmaceuticals); research funding to institution (Revolution Medicines). S.-W.K.: consulting or advisory role (AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Ono Pharmaceutical, Bristol Myers Squibb, Amgen and Boehringer Ingelheim); speakers’ bureau (Boehringer Ingelheim and Amgen); research funding (AstraZeneca). R.E.S.: consulting or advisory role (AstraZeneca, EMD Serono, Blueprint Medicines, Daiichi Sankyo, Eli Lilly, Janssen Oncology, Macrogenics, Sanofi Aventis, Regeneron and Mirati Therapeutics); travel, accommodations and expenses (AstraZeneca); honoraria (AstraZeneca and Amgen); research funding to institution (Bristol Myers Squibb and MedImmune); research funding (Merck and AstraZeneca). E.K.C.: no relationships to disclose. K.H.L.: no relationships to disclose. A.M.: consulting or advisory boards (Janssen, Merck, Takeda, GSK and Genmab); honoraria (Chugai, Novartis Oncology, Faron Pharmaceuticals, Bayer and Janssen); expenses (Amgen and LOXO Oncology). J.-S.L.: consulting or advisory role (AstraZeneca and Ono Pharmaceutical). J.-Y.H.: consulting or advisory role (MSD Oncology, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Takeda and Pfizer); honoraria (Roche, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb and Takeda); research funding (Roche, Pfizer, Ono Pharmaceutical and Takeda). M.N.: consulting or advisory role (AstraZeneca, Caris Life Sciences, Daiichi Sankyo, Takeda, Novartis, EMD Serono, Pfizer, Eli Lilly, Genentech and Janssen); speakers’ bureau (Takeda and Blueprint Medicines); travel support (AnHeart Therapeutics). J.K.S.: consulting or advisory role (AstraZeneca, Janssen Oncology, Navire, Pfizer, Regeneron, Medscape and Takeda). S.-H.I.O.: advisory role (Elevation Oncology); stock ownership (Turning Point Therapeutics and Elevation Oncology); honorarium (Pfizer); advisory fees (BeiGene, Roche/Genentech, AstraZeneca, Takeda/ARIAD, Pfizer, Caris Life Science, Janssen, Daiichi Sankyo and Eli Lilly). P.L., J.M.B., J.C.C., A.R., G.G., J.X., M.T. and R.E.K.: employment and stock ownership (Johnson & Johnson). K.P.: consulting or advisory role (AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Ono Pharmaceutical, Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Blueprint Medicines, Amgen, Merck, LOXO Oncology, AbbVie, Daiichi Sankyo, Boehringer Ingelheim, Johnson & Johnson, Eisai and Puma Biotechnology); speakers’ bureau (Boehringer Ingelheim and AZD); and research funding (AstraZeneca and Merck Sharp & Dohme).

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41591-023-02554-7.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41591-023-02554-7.

References

- 1.Gazdar AF. Activating and resistance mutations of EGFR in non-small-cell lung cancer: role in clinical response to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Oncogene. 2009;28:S24–S31. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vyse S, Huang PH. Targeting EGFR exon 20 insertion mutations in non-small cell lung cancer. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2019;4:5. doi: 10.1038/s41392-019-0038-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maemondo M, et al. Gefitinib or chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer with mutated EGFR. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;362:2380–2388. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mok TS, et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:947–957. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosell R, et al. Erlotinib versus standard chemotherapy as first-line treatment for European patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (EURTAC): a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:239–246. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70393-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sequist LV, et al. Phase III study of afatinib or cisplatin plus pemetrexed in patients with metastatic lung adenocarcinoma with EGFR mutations. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013;31:3327–3334. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.2806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou C, et al. Erlotinib versus chemotherapy as first-line treatment for patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (OPTIMAL, CTONG-0802): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:735–742. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70184-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramalingam SS, et al. Osimertinib as first-line treatment of EGFR mutation-positive advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018;36:841–849. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.74.7576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soria JC, et al. Osimertinib in untreated EGFR-mutated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018;378:113–125. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1713137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramalingam SS, et al. Overall survival with osimertinib in untreated, EGFR-mutated advanced NSCLC. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:41–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1913662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu S, et al. Sintilimab plus bevacizumab biosimilar IBI305 and chemotherapy for patients with EGFR-mutated non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer who progressed on EGFR tyrosine-kinase inhibitor therapy (ORIENT-31): first interim results from a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23:1167–1179. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(22)00382-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leonetti A, et al. Resistance mechanisms to osimertinib in EGFR-mutated non-small cell lung cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 2019;121:725–737. doi: 10.1038/s41416-019-0573-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmid S, Li JJN, Leighl NB. Mechanisms of osimertinib resistance and emerging treatment options. Lung Cancer. 2020;147:123–129. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2020.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oxnard GR, et al. Assessment of resistance mechanisms and clinical implications in patients with EGFR T790M-positive lung cancer and acquired resistance to osimertinib. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:1527–1534. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.2969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Papadimitrakopoulou VA, et al. Analysis of resistance mechanisms to osimertinib in patients with EGFR T790M advanced NSCLC from the AURA3 study. Ann. Oncol. 2018;29:viii741. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy424.064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thress KS, et al. Acquired EGFR C797S mutation mediates resistance to AZD9291 in non-small cell lung cancer harboring EGFR T790M. Nat. Med. 2015;21:560–562. doi: 10.1038/nm.3854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Minari R, Bordi P, Tiseo M. Third-generation epidermal growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitors in T790M-positive non-small cell lung cancer: review on emerged mechanisms of resistance. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2016;5:695–708. doi: 10.21037/tlcr.2016.12.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ortiz-Cuaran S, et al. Heterogeneous mechanisms of primary and acquired resistance to third-generation EGFR inhibitors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016;22:4837–4847. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang Z, et al. Investigating novel resistance mechanisms to third-generation EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor osimertinib in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018;24:3097–3107. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-2310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roper N, et al. Clonal evolution and heterogeneity of osimertinib acquired resistance mechanisms in EGFR mutant lung cancer. Cell Rep. Med. 2020;1:100007. doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2020.100007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ettinger DS, et al. Non-small cell lung cancer, version 3.2022, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J. NatlCompr. Canc. Netw. 2022;20:497–530. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2022.0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Besse B, et al. 2nd ESMO Consensus Conference on Lung Cancer: non-small-cell lung cancer first-line/second and further lines of treatment in advanced disease. Ann. Oncol. 2014;25:1475–1484. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanna NH, et al. Therapy for stage IV non-small-cell lung cancer with driver alterations: ASCO and OH (CCO) joint guideline update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021;39:1040–1091. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.03570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moores SL, et al. A novel bispecific antibody targeting EGFR and cMet is effective against EGFR inhibitor-resistant lung tumors. Cancer Res. 2016;76:3942–3953. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-2833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neijssen J, et al. Discovery of amivantamab (JNJ-61186372), a bispecific antibody targeting EGFR and MET. J. Biol. Chem. 2021;296:100641. doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2021.100641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vijayaraghavan S, et al. Amivantamab (JNJ-61186372), an Fc enhanced EGFR/cMet bispecific antibody, induces receptor downmodulation and antitumor activity by monocyte/macrophage trogocytosis. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2020;19:2044–2056. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-20-0071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yun J, et al. Antitumor activity of amivantamab (JNJ-61186372), an EGFR-MET bispecific antibody, in diverse models of EGFR exon 20 insertion-driven NSCLC. Cancer Discov. 2020;10:1194–1209. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haura EB, et al. JNJ-61186372 (JNJ-372), an EGFR-cMet bispecific antibody, in EGFR-driven advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) J. Clin. Oncol. 2019;37:9009. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2019.37.15_suppl.9009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krebs M, et al. Amivantamab in patients with NSCLC with MET exon 14 skipping mutation: updated results from the CHRYSALIS study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022;40:9008. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2022.40.16_suppl.9008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.RYBREVANT (amivantamab-vmjw) injection, for intravenous use [prescribing information]. https://www.janssenlabels.com/package-insert/product-monograph/prescribing-information/RYBREVANT-pi.pdf (Janssen Biotech, Inc., 2021).

- 31.Park K, et al. Amivantamab in EGFR exon 20 insertion-mutated non-small-cell lung cancer progressing on platinum chemotherapy: initial results from the CHRYSALIS phase I study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021;39:3391–3402. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.00662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spira A, et al. OA15.03 Amivantamab in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with MET exon 14 skipping (METex14) mutation: initial results from CHRYSALIS. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2021;16:S874–S875. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2021.08.084. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leighl NB, et al. 1192MO Amivantamab monotherapy and in combination with lazertinib in post-osimertinib EGFR-mutant NSCLC: analysis from the CHRYSALIS study. Ann. Oncol. 2021;32:S951–S952. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.08.1797. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garon EB, et al. Ramucirumab plus docetaxel versus placebo plus docetaxel for second-line treatment of stage IV non-small-cell lung cancer after disease progression on platinum-based therapy (REVEL): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2014;384:665–673. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60845-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mazieres J, et al. Tepotinib+osimertinib for EGFRm NSCLC with MET amplification (METamp) after progression on first-line (1L) osimertinib: initial results from the INSIGHT 2 study. Ann. Oncol. 2022;33:S808–S869. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2022.08.054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sequist LV, et al. Osimertinib plus savolitinib in patients with EGFR mutation-positive, MET-amplified, non-small-cell lung cancer after progression on EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors: interim results from a multicentre, open-label, phase 1b study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:373–386. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30785-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ahn MJ, et al. Lazertinib in patients with EGFR mutation-positive advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: results from the dose escalation and dose expansion parts of a first-in-human, open-label, multicentre, phase 1–2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:1681–1690. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30504-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cho BC, et al. A phase 1/2 study of lazertinib 240 mg in patients with advanced EGFR T790M-positive NSCLC after previous EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2022;17:558–567. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2021.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mok TSK, et al. Nivolumab (NIVO)+ chemotherapy (chemo) vs chemo in patients (pts) with EGFR-mutated metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (mNSCLC) with disease progression after EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) in CheckMate 722. Ann. Oncol. 2022;33:1560–1597. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2022.10.350. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee, S. H. et al. Amivantamab and lazertinib in treatment-naïve EGFR-mutated advanced non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC): long-term follow-up and ctDNA results from CHRYSALIS. J. Clin. Oncol.41, https://ascopubs.org/doi/abs/10.1200/JCO.2023.41.16_suppl.9134 (2023).

- 41.Cho, B. C. et al. 1258O Amivantamab (JNJ-61186372), an EGFR-MET bispecific antibody, in combination with lazertinib, a 3rd-generation EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), in advanced EGFR NSCLC. Ann. Oncol.10.1016/j.annonc.2020.08.1572 (2020).

- 42.Shu CA, et al. Amivantamab and lazertinib in patients with EGFR-mutant non-small cell lung (NSCLC) after progression on osimertinib and platinum-based chemotherapy: updated results from CHRYSALIS-2. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022;40:9006. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2022.40.16_suppl.9006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Park K, et al. Management of infusion-related reactions (IRRs) in patients receiving amivantamab. Ann. Oncol. 2021;32:S981–S982. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.08.1852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.John T, Liu G, Tsao MS. Overview of molecular testing in non-small-cell lung cancer: mutational analysis, gene copy number, protein expression and other biomarkers of EGFR for the prediction of response to tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Oncogene. 2009;28:S14–S23. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guo R, et al. MET IHC is a poor screen for MET amplification or MET exon 14 mutations in lung adenocarcinomas: data from a tri-institutional cohort of the Lung Cancer Mutation Consortium. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2019;14:1666–1671. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pirker R, et al. EGFR expression as a predictor of survival for first-line chemotherapy plus cetuximab in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: analysis of data from the phase 3 FLEX study. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:33–42. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70318-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mazieres J, et al. Evaluation of EGFR protein expression by immunohistochemistry using H-score and the magnification rule: re-analysis of the SATURN study. Lung Cancer. 2013;82:231–237. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2013.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Tables 1–8 and representative images of IHC staining panels a and b.

Data Availability Statement

Janssen has an agreement with the Yale Open Data Access (YODA) project to serve as the independent review panel for the evaluation of requests for clinical study reports and participant-level data from investigators and physicians for scientific research that will advance medical knowledge and public health. The project does not support requests to use data for non-scientific purposes, such as in pursuit of litigation or for commercial interests. Data will be made available after publication and approval by YODA of any formal requests with a defined analysis plan. For more information on this process or to make a request, visit the YODA project site at http://yoda.yale.edu (median response time for inquiries is 15 d). The data-sharing policy of Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson is available at https://www.janssen.com/clinical-trials/transparency.