Abstract

Background

SBO is a potentially life-threatening condition that often affects older patients. Frailty, more than age, is expected to play a crucial role in predicting SBO prognosis in this population. This study aims to define the influence of Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) on mortality and major complications in patients ≥80 years with diagnosis of SBO at the emergency department (ED).

Methods

All patients aged ≥80 years admitted to our ED for SBO from January 2015 to September 2020 were enrolled. Frailty was assessed through the CFS, and then analyzed both as a continuous and a dichotomous variable. The endpoints were in-hospital mortality and major complications.

Results

A total of 424 patients were enrolled. Higher mortality (20.8% vs 8.6%, p<0.001), longer hospital stay (9 [range 5–14] days vs 7 [range 4–12] days, p=0.014), and higher rate of major complications (29.9% vs 17.9%, p=0.004) were associated with CFS ≥7. CFS score and bloodstream infection were the only independent prognostic factors for mortality (OR 1.72 [CI: 1.29–2.29], p<0.001; OR 4.69 [CI: 1.74–12.6], p=0.002, respectively). Furthermore, CFS score, male sex and surgery were predictive factors for major complications (OR 1.41 [CI: 1.13–1.75], p=0.002; OR 1.67 [CI: 1.03–2.71], p=0.038); OR 1.91 [CI: 1.17–3.12], p=0.01; respectively). At multivariate analysis, for every 1-point increase in CFS score, the odds of mortality and the odds of major complications increased 1.72-fold and 1.41-fold, respectively.

Conclusion

The increase in CFS is directly associated with an increased risk of mortality and major complications. The presence of severe frailty could effectively predict an increased risk of in-hospital death regardless of the treatment administered. The employment of CFS in elderly patients could help the identification of the need for closer monitoring and proper goals of care.

Keywords: Small bowel obstruction (SBO), Frailty, Elderly, Emergency surgery, Non-operative management (NOM)

Introduction

Small bowel obstruction (SBO) accounts for 15% of emergency department (ED) admissions for abdominal pain and its burden is estimated to be higher in patients older than 80 years [1–3]. Adhesions, hernias, and neoplasms are the leading causes of SBO in nine out of ten patients [4]. Therefore, the occurrence of SBO increases proportionally with the age of patients requiring ED admission [4]. Furthermore, despite a similar clinical presentation, the observed mortality is much higher in octogenarians than in younger patients, due to the remarkable rate of cardiovascular and metabolic comorbidities [5].

The burden of SBO in older patients is even more relevant considering that, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), the segment of the population older than 80 years is expected to triple in the next decades, reaching 426 million people worldwide by 2050 [6].

Nevertheless, geriatric patients represent a heterogeneous population in terms of physical and neurological performances, comorbidities, and resilience to acute insults [7, 8]. Consequently, prognosis and mortality after SBO may vary widely [7, 8].

To overcome the mismatch between chronological age, comorbidities, and older patients’ general health status and prognosis, the concept of frailty was proposed [9, 10]. In particular, the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) is a viable and reproducible tool for assessing frailty [11], and its reliability as an independent predictor of mortality has already been validated for elective and emergency surgical and nonsurgical populations [12–17]. However, its effectiveness for SBO in octogenarians remains unproven in the emergency setting.

This study aims to define the influence of frailty through CFS on mortality and major complications in patients ≥ 80 years or older with a proven diagnosis of SBO at the ED.

Methods

Study Design

This is a single-centre, prospective, observational cohort study, performed in the ED of a tertiary care University Hospital (Fondazione Policlinico Universitario “Agostino Gemelli” IRCCS of Rome) with an average attendance of about 75,000 patients per year (more than 87% adults).

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

After the approval of the Institutional Review Board (Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemelli IRCCS, Rome, Italy, ID: 5121/2022), all patients aged ≥80 years consecutively admitted to our ED for SBO from January 2015 to September 2020 were enrolled, regardless of operative or non-operative management (NOM).

The denial to participate in the study and the lack of a complete frailty assessment represented exclusion criteria.

The clinical records of the eligible patients were retrospectively collected from a prospectively maintained databases and identified using the International Classification of Disease, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes [18], as follows: 560.0, 560.80, 560.81, 560.89, 560.90.

Study Variables

The following demographic and clinical data were collected: age and gender; frailty assessed via CFS as reported by Rockwood et al. [11], clinical presentation at admission (abdominal pain, fever, vomit, gastrointestinal bleeding), vital signs (heart rate, blood pressure, peripheral oxygen saturation, body temperature) and laboratory results (haemoglobin, white blood cells count, serum glucose and creatinine, prothrombin time test, fibrinogen), clinical history and comorbidities (coronary artery disease, chronic heart failure, cerebrovascular disease, dementia, peripheral artery disease, connective tissue disease, cirrhosis, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, malignancy), including Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) [19], aetiology (malignancies, surgical adhesions, hernias, volvulus), 30-day mortality, length of hospital stay (LOS), calculated from the time of ED admission to discharge or death, major complications, defined as the need for prolonged stay into intensive care unit (> 96 h), the occurrence of sepsis (defined according to sepsis-3 criteria [20]) or peritonitis, and death.

Small Bowel Obstruction Assessment

SBO was diagnosed after ED admission through clinical examination, laboratory tests, and imaging. Specifically, SBO diagnosis was radiologically confirmed by an abdominal CT scan in all patients. NOM, surgical management, and their timing were previously described [21]. With ‘interventional procedure’, any interventional endoscopic or radiological procedure with drainage insertion was considered (i.e. bowel decompression, fluid evacuation).

Clinical Frailty Scale Assessment

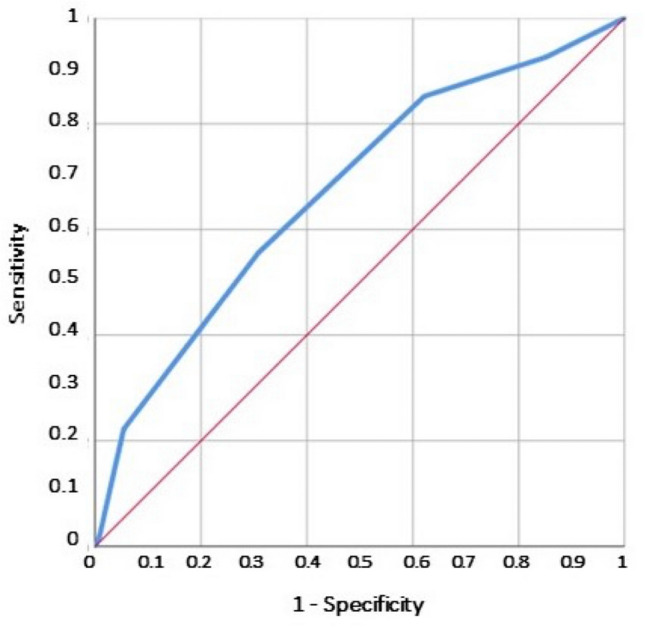

Frailty was assessed by the CFS [11]. CFS was analyzed both as a continuous and a dichotomous variable. In the latter case, patients were divided into two groups according to CFS: mild or moderately frail for CFS ≤6, and severely frail in case of CFS ≥ 7. The obtained CFS score was evaluated for overall accuracy in identifying patients at risk of frailty by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. The sensitivity and specificity were identified for each score level by ROC analysis. The optimal dividing cut-off associated with CFS score was obtained by Youden's index, and a two-sided p-value ≤ 0.05 was regarded as significant. The best discriminating value was ≥ 7 which corresponds to severe frailty (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Receiver operating characteristics analysis (ROC) of the Clinical Frailty Score (CFS) for the prediction of all-cause in-hospital death. According to the Youden index J, the best discriminating value was ≥ 7 which corresponds to severe frailty

Study Endpoints

The endpoints of this study were the occurrence of in-hospital death and the cumulative occurrence of major complications (defined as the occurrence of any among septic shock, need for ICU admission, and death).

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were reported as median (interquartile range) and compared by the Mann–Whitney U test. Categorical variables were reported as absolute numbers (percentage) and statistically compared by the chi-square test (with Fisher test if appropriate). Multiple comparisons were assessed for false discovery rate (FDR) by the Benjamini–Hocheberg method.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed to test the specificity and sensitivity of the CFS predicting endpoints (in-hospital mortality and major complications). ROC Youden’s index J was used to determine the best cut-off values for CFS to define outcomes. The c-statistic evaluates CFS discrimination and represents the area under the ROC curve (AUC). A value of 0.5 is equivalent to chance; a value of 1.0 indicates perfect discrimination. Nevertheless, the CFS score was also included in the multivariate analysis as a continuous variable, achieving the odds of increased risk for each point of CFS value.

The variables reaching statistical significance at univariate analysis were considered for the multivariate logistic regression model. Multivariate models excluded the single items composing any derived variable, both to avoid model overfitting and parameter overestimation. The risk of intrahospital death and major complications was expressed as odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidential interval (CI). A 2-sided p ≤ 0.05 was considered significant in all the analyses.

Data were analyzed by SPSS v25® (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Patients’ Characteristics

During the study period, a total of 424 patients ≥ 80 years (239 females and 185 males with a median age of 85 years) were admitted to our ED with a diagnosis of SBO. The clinical and demographic characteristics of the study population are reported in Table 1. Overall, 280 patients (66%) had a CFS score between 1 and 6, and 144 patients (34%) had a CFS score of 7–9.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of enrolled patients according to the frailty as assessed by the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) at the emergency department admission

| All cases N 424 |

CFS 1-6 N 280 |

CFS 7-9 N 144 |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 85 [82–89] | 84 [81–87] | 88 [84–91] | <0.001 |

| Female | 239 (56.4%) | 167 (59.6%) | 72 (50%) | 0.037 |

| ED presentation | ||||

| Fever | 361 (85.1%) | 240 (85.7%) | 121 (84%) | 0.37 |

| Abdominal pain | 281 (66.3%) | 201 (71.8%) | 80 (55.6%) | 0.001 |

| Vomit | 209 (49.3%) | 145(51.8%) | 64 (44.4%) | 0.092 |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 22 (5.2%) | 16 (5.7%) | 6 (4.2%) | 0.33 |

| Treatment | ||||

| Medical treatment | 246 (58.1%) | 157 (56.1%) | 89 (61.8%) | |

| Percutaneous procedures | 18 (4.2%) | 10 (3.6%) | 8 (5.6%) | 0.17 |

| Ostomy creation | 56 (13.2%) | 31 (11.1%) | 47 (32.6%) | 0.05 |

| Surgery (overall) | 160 (37.7%) | 113 (40.3%) | 47 (32.6%) | 0.073 |

| Coexistent acute infections | ||||

| Bloodstream infection | 23 (5.4%) | 17 (6.1%) | 6 (4.2%) | 0.28 |

| Any infections | 73 (17.2%) | 40 (14.3%) | 33 (22.9%) | 0.019 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| CCI | 6 [4–8] | 6 [4–7] | 7 [5–7] | <0.001 |

| CFS | 6 [5–7] | 5 [5–6] | 7 [7–8] | <0.001 |

| History of CAD | 60 (14.2%) | 40 (14.3%) | 20 (13.9%) | 0.52 |

| CHF | 45 (10.6%) | 23 (8.2%) | 22 (15.3%) | 0.021 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 32 (7.5%) | 19 (6.8%) | 13 (9.0%) | 0.26 |

| Dementia | 50 (11.8%) | 16 (5.7%) | 34 (23.6%) | <0.001 |

| COPD | 58 (13.7%) | 37 (13.2%) | 21 (14.6%) | 0.401 |

| Chronic Kidney disease | 67 (15.8%) | 35 (12.5%) | 32 (22.2%) | 0.008 |

| Diabetes | 48 (11.3%) | 33 (11.8%) | 15 (10.4%) | 0.673 |

| Oncological disease | 166 (39.2%) | 106 (37.9%) | 60 (41.7%) | 0.25 |

| Metastatic Cancer | 64 (15.1%) | 28 (10%) | 36 (25%) | <0.001 |

| Aetiology | ||||

| Malignancy | 120 (28.3%) | 71 (25.4%) | 49 (34%) | 0.04 |

| Surgical adhesions | 61 (14.4%) | 50 (17.9%) | 11 (7.6%) | 0.003 |

| Hernia | 35 (8.3%) | 28 (10%) | 7 (4.9%) | 0.047 |

| Volvulus | 19 (4.5%) | 10 (3.6%) | 9 (6.3%) | 0.155 |

| Perforation | 16 (3.8%) | 11 (3.9%) | 5 (3.5%) | 0.525 |

| Outcomes | ||||

| Death (all causes) | 54 (12.7%) | 24 (8.6%) | 30 (20.8%) | <0.001 |

| Length of stay (LOS) | 8 [5–13] | 7 [4–12] | 9 [5–14] | 0.014 |

| Major complications | 84 (19.8%) | 38 (13.6%) | 46 (31.9%) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; CFS, Clinical Frailty Scale; CAD, coronary artery disease; CHF, chronic heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

The most common clinical signs at ED admission were fever (85.1%) and abdominal pain (66.3%), but only the latter was significantly more frequent in the group including non-to-moderately frail patients (p=0.001). Moreover, patients with severe frailty (CFS ≥7) were characterized by higher median CCI (7 [range 5–7] vs 6 [range 4–7], p<0.001).

Malignancies represented the most frequent aetiology in the severely frail group (34% vs 25.4%, p=0.04) while a higher incidence of surgical adhesions and hernias was found in mild-to-moderately frail patients (17.9% vs 7.6%, p=0.003; and 10% vs 4.9%, p=0.047, respectively).

Comparing outcomes, higher mortality (20.8% vs 8.6%, p<0.001), longer LOS (9 [range 5–14] days vs 7 [range 4–12] days, p=0.014), and a higher rate of major complications (29.9% vs 17.9%, p=0.004) were significantly associated with higher frailty index (CFS ≥7). At the same time, an ostomy was needed significantly more frequently in patients with severe frailty (p=0.05).

Factors Associated with Mortality

The association of the study variables with mortality is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Factors associated with mortality

| Survived N 370 |

Deceased N 54 |

Univariate p value | Odds Ratio [95% interval] | Multiv. p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFS 1–6 | 256 (69.2%) | 24 (44.4%) | |||

| CFS 7–9 | 114 (30.8%) | 30 (55.6%) | <0.001 | ||

| CFS | 6 [5–7] | 7 [6–7] | <0.001 | 1.72 [1.29–2.29] | <0.001 |

| Age | 85 [82–89] | 85 [81–91] | 0.468 | ||

| Sex (male) | 153 (41.4%) | 32 (59.3%) | 0.013 | 1.73 [0.93–3.23] | 0.084 |

| ED presentation | |||||

| Fever | 55 (14.9%) | 8 (14.8%) | 0.59 | ||

| Abdominal pain | 249 (67.3%) | 32 (59.3%) | 0.15 | ||

| Vomit | 185 (50%) | 24 (44.4%) | 0.27 | ||

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 17 (4.6%) | 5 (9.3%) | 0.134 | ||

| Perforation | 11 (3%) | 5 (9.3%) | 0.04 | 2.37 [0.71–7.89] | 0.158 |

| Treatment | |||||

| Medical treatment | 213 (57.6%) | 33 (61.1%) | |||

| Percutaneous procedures | 15 (4.1%) | 3 (5.6%) | 0.408 | ||

| Ostomy creation | 50 (13.5%) | 6 (11.1%) | |||

| Surgery (overall) | 142 (38.4%) | 18 (33.3%) | 0.289 | ||

| Coexistent acute infections | |||||

| Bloodstream infection | 14 (3.8%) | 9 (16.7%) | 0.001 | 4.69 [1.74–12.6] | 0.002 |

| Any infections | 62 (16.8%) | 11 (20.4%) | 0.31 | ||

| Comobidities | |||||

| CCI | 6 [4–8] | 6 [5–8] | 0.273 | ||

| CFS | 6 [5–7] | 7 [6–7] | <0.001 | ||

| History of CAD | 51 (13.8%) | 9 (16.7%) | 0.35 | ||

| CHF | 38 (10.3%) | 7 (13%) | 0.34 | ||

| Cerebrovascular disease | 27 (7.3%) | 5 (9.3%) | 0.39 | ||

| Dementia | 41 (11.1%) | 9 (16.7%) | 0.166 | ||

| COPD | 50 (13.5%) | 8 (14.8%) | 0.465 | ||

| Chronic kidney disease | 59 (15.9%) | 8 (14.8%) | 0.509 | ||

| Oncological disease | 144 (38.9%) | 22 (40.7%) | 0.454 | ||

| Metastatic cancer | 55 (14.9%) | 9 (16.7%) | 0.43 | ||

| Aetiology | |||||

| Malignancy | 100 (27%) | 20 (37%) | 0.088 | ||

| Non malignant | 102 (27.6%) | 3 (5.6%) | <0.001 | 0.21 [0.06–0.71] | 0.012 |

| (i) Adhesions | 60 (16.2%) | 1 (1.9%) | 0.001 | ||

| (ii) Hernia | 34 (9.2%) | 1 (1.9%) | 0.045 | ||

| (iii) Volvulus | 18 (4.9%) | 1 (1.9%) | 0.027 | ||

Abbreviations: CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; CFS, Clinical Frailty Scale; CAD, coronary artery disease; CHF, chronic heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

At univariate analysis, CFS score (p<0.001), CFS ≥7 (p<0.001), male sex (p=0.013), intestinal perforation (p=0.04), and bloodstream infections (p=0.001) were significantly associated with higher mortality. Conversely, as far as aetiology is concerned, surgical adhesions (p=0.001), hernia (p=0.045), and volvulus (p=0.027) were associated with a lower mortality rate, whereas malignancy (p=0.088) was associated with a higher death rate.

After the adjustment for covariates, only CFS score (OR 1.72 [CI: 1.29–2.29], p<0.001) and blood stream infection (OR 4.69 [CI: 1.74–12.6], p=0.002) emerged as independent risk factors for mortality, whereas non malignant aetiology (OR 0.21 [CI: 0.06–0.71], p=0.012) resulted as protective factor at multivariate analysis. For every 1-point increase in CFS score, the odds of mortality increased 1.72-fold.

Factors Associated with the Occurrence of Major Complications

The association of the study variables with complications is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Factors associated with cumulative major complications (death, sepsis, admission to ICU)

| NOT major complications N 340 | Major complications N 84 | Univariate p value | Odds ratio [95% interval] | Multiv. p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFS 1–6 | 242 (71.2%) | 38 (45.2%) | |||

| CFS 7–9 | 98 (28.8%) | 46 (54.8%) | |||

| CFS value | 6 [5–7] | 6 [6–7] | 0.002 | 1.41 [1.13–1.75] | 0.002 |

| Age | 85 [82–89] | 85 [81–91] | 0.485 | ||

| Sex (Male) | 134 (40.5%) | 51 (54.8%) | 0.014 | 1.67 [1.03–2.71] | 0.038 |

| ED presentation | |||||

| Fever | 47 (13.8%) | 16 (19.0%) | 0.228 | ||

| Abdominal pain | 235 (69.1%) | 46 (54.8%) | 0.013 | 0.69 [0.42–1.13] | 0.141 |

| Vomit | 171 (50.3%) | 38 (45.2%) | 0.407 | ||

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 17 (5.0%) | 5 (6.0%) | 0.725 | ||

| Perforation | 12 (3.5%) | 4 (4.8%) | 0.596 | ||

| Treatment | |||||

| Medical treatment | 205 (61.9%) | 41 (44.1%) | 0.471 | ||

| Percutaneous procedures | 11 (3.3%) | 7 (7.5%) | 0.005 | ||

| Ostomy | 39 (11.5%) | 17 (20.2%) | 0.034 | ||

| Surgery (overall) | 124 (36.5%) | 36 (42.9%) | 0.012 | 1.91 [1.17–3.12] | 0.010 |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| CCI | 6 [4–8] | 7 [5–9] | 0.045 | 0.97 [0.86–1.09] | 0.649 |

| History of CAD | 43 (12.6%) | 17 (20.2%) | 0.074 | ||

| CHF | 33 (9.7%) | 12 (14.3%) | 0.222 | ||

| Cerebrovascular disease | 24 (7.1%) | 8 (9.5%) | 0.440 | ||

| Dementia | 35 (10.3%) | 15 (17.9%) | 0.054 | ||

| COPD | 48 (14.1%) | 10 (11.9%) | 0.597 | ||

| Diabetes | 31 (9.1%) | 17 (20.2%) | 0.004 | ||

| Chronic kidney disease | 55 (16.2%) | 12 (14.3%) | 0.671 | ||

| Oncological disease | 127 (37.4%) | 43 (46.4%) | 0.127 | ||

| Metastatic cancer | 47 (13.8%) | 17 (20.2%) | 0.141 | ||

| Aetiology | |||||

| Malignancy | 88 (25.9%) | 32 (38.1%) | 0.026 | 1.53 [0.78–2.97] | 0.213 |

| Non malignant | 90 (27.2%) | 15 (16.1%) | 0.029 | ||

| (i) Surgical Adhesions | 56 (16.5%) | 5 (6.0%) | 0.014 | ||

| (ii) Hernia | 31 (9.1%) | 4 (4.8%) | 0.194 | ||

| (iii) Volvulus | 16 (4.7%) | 3 (3.6%) | 0.653 | ||

Abbreviations: CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; CFS, Clinical Frailty Scale; CAD, coronary artery disease; CHF, chronic heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Higher CFS (p=0.022), male sex (p=0.014), patients presenting with abdominal pain (p=0.013), higher CCI (p=0.045), diabetes (p=0.004), and those with a malignant aetiology (p=0.026) had a higher rate of occurrence of major complications. Conversely, those with surgical adhesions had a lower rate of major complications (p=0.014).

Surgical treatment (p=0.012), including the need for ostomy creation (p=0.034), and percutaneous procedures (p=0.005) were significantly associated with major complications at univariate analysis.

After adjusting for covariates, only CFS score (OR 1.41 [CI: 1.13–1.75], p=0.002), male sex (OR 1.67 [CI: 1.03–2.71], p=0.038), and surgical treatment (OR 1.91 [CI: 1.17–3.12], p=0.01) were independently predictive of the risk of major complications at multivariate analysis. More specifically, for every 1-point increase in CFS score, the odds of having major complications increased 1.41-fold.

Graphical representation of the adjusted odds for death and major complications were separately calculated for surgical interventions both in the group of patients with low to moderate frailty, and in the group with severe frailty (Fig. 2). Surgery was not associated with in-hospital death in CFS 1-7 and CFS 6-9 groups (OR 1.017 [0.409–2.580] and OR 1.44 [0.549–3.788], respectively).

Fig. 2.

Graphical representation of the adjusted odds for death and major complications calculated for surgical interventions separately in the group of patients with low to moderate frailty, and in the group with severe frailty. Surgery was not associated with in-hospital death in CFS 1-7 and CFS 6-9 groups (OR 1.017 [0.409–2.580] and OR 1.44 [0.549–3.788], respectively). Conversely, surgery was associated with a significant increase in the odds for cumulative major complications in the CFS 7-9 group (CFS 7-9 group: OR 4.02 [1.701–9.499]; CFS 1-6 group: OR 1.19 [0.553–2.557])

Conversely, surgical treatment was associated with a significant increase in the odds for cumulative major complications in the CFS 7-9 group (OR 4.02 [1.701–9.499]).

Discussion

In the present study, we evaluated the outcomes of 424 consecutive octogenarians admitted to the ED with a diagnosis of SBO according to their frailty status, as defined by the CFS. This study represents one of the few attempts in the current literature to evaluate the association between frailty and the outcomes of geriatric patients admitted to the ED with a diagnosis of SBO, and the only experience evaluating these patients through the CFS tool.

SBO is a potentially life-threatening condition that often affects older patients. Due to the progressive ageing of the general population, the incidence of SBO is expected to grow in the next decades, as the occurrence of its leading causes, such as adherence resulting from previous surgery, hernias, and neoplasms, reaches its peak in geriatric patients [1–4, 6].

The management of SBO in this population can be challenging, as a consequence of the higher complexity of elderly patients in terms of comorbidities and capacity to cope with acute stress [5]. Very few studies have shown a higher risk of mortality and complications in octogenarians as compared to younger patients [8, 22–24]. Nevertheless, the geriatric population is widely heterogeneous [7, 8], and stratifying the risk of death and complications after a diagnosis of SBO has become of paramount importance to provide appropriate care and tailored treatment to this group of patients.

As demonstrated by our recent experience [21], the management of SBO in the elderly requires more than just a ‘copy and paste’ of recommendations and guidelines designed for younger patients and, in selected elderly patients with multiple comorbidities or functional impairments, a NOM should always be considered [25, 26], and a comprehensive geriatric assessment is necessary to optimize the diagnostic and clinical strategies [27, 28].

Moreover, as demonstrated by several studies in the current literature, age “as itself” does not represent a comprehensive indicator of the functional reserve of older patients, as it does not provide any reliable information on their comorbidities and general condition [7, 8]. For this reason, the ‘frailty’ concept was introduced as an attempt to encompass the decline in physiologic functions and reduced resilience to internal and external stressors leading to an increased risk of poorer outcomes in the geriatric population [16, 17, 29].

The CFS represent a simple, reproducible, and validated tool for frailty assessment [11, 14], to overcome the complexity of formal evaluations and time-consuming specialized tests, often unavailable in the clinical setting [29–38]. In our study, we found a significantly higher mortality, a longer LOS and a higher rate of complications in the cohort of severely frail patients, regardless of the type of treatment performed. Moreover, CFS was an independent prognostic factor of mortality (p<0.001) in the analysed population. Conversely, neither age nor comorbidities were significantly associated to increased mortality in the same patients. On the other hand an increased CFS, male gender and surgery were independently predictive of the risk of major complications. Furthermore, a a point-by-point increase in the CFS score lead to a 1.72-fold and 1.41-fold increase in mortality and major complications, respectively.

These results were not surprising. First of all, both data and common sense suggest increased mortality and morbidity for frail patients undergoing abdominal operations. Secondly, when NOM of SBO is chosen as the first line treatment, it may cause harmful effects on patients’ nutritional status due to the prolonged fasting in a population that is at high risk of malnutrition even before presentation to the emergency room [39, 40], eventually leading to adverse outcomes if the surgical operation is finally performed [39, 40].

Unfortunately, no dedicated recommendations addressing the best management of SBO in frail patients are present in the current international reference guidelines [41].

Our results are in line with those of a recent study by Hwang et al. [42], where the outcomes in terms of mortality and morbidity of 264,670 patients over the age of 65 were investigated. The authors found that frail patients were twice as likely to die as compared to the non-frail population (10% vs 5%, p<0.001). Moreover, frailty was found as an independent predictor of in-hospital mortality (aOR 1.82; 95% CI 1.64–2.039), along with other factors such as ethnicity, male gender, increasing age, lower socio-economic status, and undergoing a surgical operation. Nevertheless, the authors employed the Colon Cancer Frailty Index (CCFI) [43] instead of CFS, to stratify their patients into frail vs non-frail ones, making the comparison with our results less obvious.

Therefore, the CFS could reasonably allow the surgeon to better discriminate a surgical procedure or a NOM. Nevertheless, we suggest that this scale must not ignore the physical examination and the case-by-case patient assessment, which remains a fundamental part of the surgeon's evaluation, frequently based on surgeon training and experience.

Study Limitations

Our study has undoubtedly some limitations. First of all, his retrospective design may have caused potential biases in patients’ inclusion and data analysis. Nevertheless, including not only patients who have undergone surgical procedures but also those who were managed with a NOM may have avoided the active exclusion of frailer patients not eligible for invasive procedures.

Secondly, despite the CFS was analyzed both as a continuous and a dichotomous variable, it should be underlined that considering CFS as a dichotomic variable (the analysis was carried out considering patients with CFS ≤6 and severely frail patients with CFS ≥7 as two distinguished groups) needs validation by future research. Thirdly, although fair, the sample size of the present study was limited, thus limiting the statistical power of our results. Indeed, a sample size of 588 and 786 patients would have been needed in order to reach a statistical power of 0.8 and 0.9, respectively. Finally, this study focused on short-term prognosis and complications, with no evaluation of long-term outcomes.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our results demonstrated that, in patients ≥80 years with SBO, the presence of severe frailty through a CFS ≥7 could effectively predict an increased risk of death regardless of the treatment administered and a higher risk risk of major complications for patients undergoing surgical procedures. Furthermore, an increasing CFS score is directly associated with an increased risk of mortality and major complications. Therefore, CFS should be considered a useful tool to assess frailty for elderly patients, helping the identification of the need for closer monitoring and the proper goals of care for each patient, avoiding unnecessary and possibly harmful treatments. Other variables, such as the aetiology of SBO, time to operation, and time to enteral nutrition, should be considered to further address the challenges in the management of the growing geriatric population with SBO and improve their outcomes. Future multicenter studies are needed to define dedicated recommendations for octogenarians with SBO to confirm our findings.

Author Contributions

All authors made substantiable contributions to the conception of the work, the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data; drafted the work and revised it critically for important intellectual content; and approved the version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Declarations

Ethics Approval

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and later versions.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Vito Laterza and Marcello Covino share first authorship. Sergio Alfieri and Fausto Rosa share senior authorship.

References

- 1.Catena F, De Simone B, Coccolini F, Di Saverio S, Sartelli M, Ansaloni L. Bowel obstruction: a narrative review for all physicians. World J Emerg Surg. 2019;14:20. doi: 10.1186/s13017-019-0240-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foster NM, McGory ML, Zingmond DS, Ko CY. Small bowel obstruction: a population-based appraisal. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203:170–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spangler R, Van Pham T, Khoujah D, Martinez JP. Abdominal emergencies in the geriatric patient. Int J Emerg Med. 2014;7:43. doi: 10.1186/s12245-014-0043-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper Z, Mitchell SL, Gorges RJ, Rosenthal RA, Lipsitz SR, Kelley AS. Predictors of Mortality Up to 1 Year After Emergency Major Abdominal Surgery in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:2572–2579. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanson TG, O'Keefe KP. Evaluation of abdominal pain in the elderly. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1996;14:615–627. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8627(05)70270-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO. Ageing and health. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health (accessed on

- 7.Fabbri E, Zoli M, Gonzalez-Freire M, Salive ME, Studenski SA, Ferrucci L. Aging and Multimorbidity: New Tasks, Priorities, and Frontiers for Integrated Gerontological and Clinical Research. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16:640–647. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ball CG, Murphy P, Verhoeff K, Albusadi O, Patterson M, Widder S, Hameed SM, Parry N, Vogt K, Kortbeek JB, et al. A 30-day prospective audit of all inpatient complications following acute care surgery: How well do we really perform? Can J Surg. 2020;63:E150–E154. doi: 10.1503/cjs.019118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joseph B, Orouji Jokar T, Hassan A, Azim A, Mohler MJ, Kulvatunyou N, Siddiqi S, Phelan H, Fain M, Rhee P. Redefining the association between old age and poor outcomes after trauma: The impact of frailty syndrome. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;82:575–581. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet. 2013;381:752–762. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62167-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, Bergman H, Hogan DB, McDowell I, Mitnitski A. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ. 2005;173:489–495. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hewitt J, Moug SJ, Middleton M, Chakrabarti M, Stechman MJ, McCarthy K, Older Persons Surgical Outcomes, C Prevalence of frailty and its association with mortality in general surgery. Am J Surg. 2015;209:254–259. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2014.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosa F, Covino M, Russo A, Salini S, Forino R, Della Polla D, Fransvea P, Quero G, Fiorillo C, La Greca A, et al. Frailty assessment as independent prognostic factor for patients >/=65 years undergoing urgent cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Dig Liver Dis. 2022;55(4):505–12. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2022.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hewitt J, Long S, Carter B, Bach S, McCarthy K, Clegg A. The prevalence of frailty and its association with clinical outcomes in general surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing. 2018;47:793–800. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afy110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parmar KL, Law J, Carter B, Hewitt J, Boyle JM, Casey P, Maitra I, Farrell IS, Pearce L, Moug SJ, et al. Frailty in Older Patients Undergoing Emergency Laparotomy: Results From the UK Observational Emergency Laparotomy and Frailty (ELF) Study. Ann Surg. 2021;273:709–718. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Covino M, Russo A, Salini S, De Matteis G, Simeoni B, Della Polla D, Sandroni C, Landi F, Gasbarrini A, Franceschi F. Frailty Assessment in the Emergency Department for Risk Stratification of COVID-19 Patients Aged >/=80 Years. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021;22:1845–1852. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2021.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Covino M, Salini S, Russo A, De Matteis G, Simeoni B, Maccauro G, Sganga G, Landi F, Gasbarrini A, Franceschi F. Frailty Assessment in the Emergency Department for Patients >/=80 Years Undergoing Urgent Major Surgical Procedures. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2022;23:581–588. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2021.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gautam N, Bessette L, Pawar A, Levin R, Kim DH. Updating International Classification of Diseases 9th Revision to 10th Revision of a Claims-Based Frailty Index. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2021;76:1316–1317. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glaa150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, Gold J. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47:1245–1251. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, Bellomo R, Bernard GR, Chiche JD, Coopersmith CM, et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3) JAMA. 2016;315:801–810. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosa F, Covino M, Fransvea P, Quero G, Pacini G, Fiorillo C, Simeoni B, La Greca A, Sganga G, Franceschi F, et al. Management of Small Bowel Obstruction (SBO) in older adults (>80 years): a propensity score-matched analysis on predictive factors for a (un)successful non-operative management (NOM) Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2022;26:7219–7228. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202210_29914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fabbian, F.; De Giorgi, A.; Ferro, S.; Lacavalla, D.; Andreotti, D.; Ascanelli, S.; Volpato, S.; Occhionorelli, S. Post-Operative All-Cause Mortality in Elderly Patients Undergoing Abdominal Emergency Surgery: Role of Charlson Comorbidity Index. Healthcare (Basel)2021, 9, 10.3390/healthcare9070805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Duning T, Ilting-Reuke K, Beckhuis M, Oswald D. Postoperative delirium - treatment and prevention. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2021;34:27–32. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0000000000000939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bentrem DJ, Cohen ME, Hynes DM, Ko CY, Bilimoria KY. Identification of specific quality improvement opportunities for the elderly undergoing gastrointestinal surgery. Arch Surg. 2009;144:1013–1020. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2009.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quero G, De Sio D, Covino M, Fiorillo C, Laterza V, Schena CA, Rosa F, Menghi R, Carbone L, Piccioni A, et al. Adhesive small bowel obstruction in octogenarians: A 6-year retrospective single-center analysis of clinical management and outcomes. Am J Surg. 2022;224:1209–1214. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2022.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosa, F.; Covino, M.; Schena, C.A.; Quero, G.; Franceschi, F.; Sganga, G.; Alfieri, S. Successful Nonoperative Management (NOM) in Elderly Patients with Adhesive Small Bowel Obstruction (ASBO): a Cross-Sectional Analysis. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery2023, 10.1007/s11605-023-05771-0. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Quero G, Covino M, Laterza V, Fiorillo C, Rosa F, Menghi R, Fransvea P, Cozza V, Sganga G, Franceschi F, et al. Adhesive small bowel obstruction in elderly patients: a single-center analysis of treatment strategies and clinical outcomes. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2021;56:784–790. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2021.1921256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ozturk E, van Iersel M, Stommel MM, Schoon Y, Ten Broek RR, van Goor H. Small bowel obstruction in the elderly: a plea for comprehensive acute geriatric care. World J Emerg Surg. 2018;13:48. doi: 10.1186/s13017-018-0208-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vermeiren S, Vella-Azzopardi R, Beckwee D, Habbig AK, Scafoglieri A, Jansen B, Bautmans I, Gerontopole Brussels Study , g Frailty and the Prediction of Negative Health Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17:1163 e1161–1163 e1117. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2016.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Farhat JS, Velanovich V, Falvo AJ, Horst HM, Swartz A, Patton JH, Jr, Rubinfeld IS. Are the frail destined to fail? Frailty index as predictor of surgical morbidity and mortality in the elderly. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;72:1526–1530. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182542fab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Richards SJG, Frizelle FA, Geddes JA, Eglinton TW, Hampton MB. Frailty in surgical patients. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2018;33:1657–1666. doi: 10.1007/s00384-018-3163-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McIsaac DI, MacDonald DB, Aucoin SD. Frailty for Perioperative Clinicians: A Narrative Review. Anesth Analg. 2020;130:1450–1460. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maxwell CA, Patel MB, Suarez-Rodriguez LC, Miller RS. Frailty and Prognostication in Geriatric Surgery and Trauma. Clin Geriatr Med. 2019;35:13–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2018.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gleason LJ, Benton EA, Alvarez-Nebreda ML, Weaver MJ, Harris MB, Javedan H. FRAIL Questionnaire Screening Tool and Short-Term Outcomes in Geriatric Fracture Patients. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18:1082–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chia-Hui Chen C, Yang YT, Lai IR, Lin BR, Yang CY, Huang J, Tien YW, Chen CN, Lin MT, Liang JT, et al. Three Nurse-administered Protocols Reduce Nutritional Decline and Frailty in Older Gastrointestinal Surgery Patients: A Cluster Randomized Trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20:524–529 e523. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2018.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eamer G, Al-Amoodi MJH, Holroyd-Leduc J, Rolfson DB, Warkentin LM, Khadaroo RG. Review of risk assessment tools to predict morbidity and mortality in elderly surgical patients. Am J Surg. 2018;216:585–594. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2018.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Amrock LG, Neuman MD, Lin HM, Deiner S. Can routine preoperative data predict adverse outcomes in the elderly? Development and validation of a simple risk model incorporating a chart-derived frailty score. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;219:684–694. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Theou O, Brothers TD, Mitnitski A, Rockwood K. Operationalization of frailty using eight commonly used scales and comparison of their ability to predict all-cause mortality. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:1537–1551. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ho JW, Wu AH, Lee MW, Lau SY, Lam PS, Lau WS, Kwok SS, Kwan RY, Lam CF, Tam CK, et al. Malnutrition risk predicts surgical outcomes in patients undergoing gastrointestinal operations: Results of a prospective study. Clin Nutr. 2015;34:679–684. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2014.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mosquera C, Koutlas NJ, Edwards KC, Strickland A, Vohra NA, Zervos EE, Fitzgerald TL. Impact of malnutrition on gastrointestinal surgical patients. J Surg Res. 2016;205:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2016.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ten Broek RPG, Krielen P, Di Saverio S, Coccolini F, Biffl WL, Ansaloni L, Velmahos GC, Sartelli M, Fraga GP, Kelly MD, et al. Bologna guidelines for diagnosis and management of adhesive small bowel obstruction (ASBO): 2017 update of the evidence-based guidelines from the world society of emergency surgery ASBO working group. World J Emerg Surg. 2018;13:24. doi: 10.1186/s13017-018-0185-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hwang F, Crandall M, Smith A, Parry N, Liepert AE. Small bowel obstruction in older patients: challenges in surgical management. Surg Endosc. 2023;37:638–644. doi: 10.1007/s00464-022-09428-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pandit V, Khan M, Martinez C, Jehan F, Zeeshan M, Koblinski J, Hamidi M, Omesieta P, Osuchukwu O, Nfonsam V. A modified frailty index predicts adverse outcomes among patients with colon cancer undergoing surgical intervention. Am J Surg. 2018;216:1090–1094. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2018.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]