Summary

Background

With the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 variants resistant to monoclonal antibody therapies and limited global access to therapeutics, the evaluation of novel therapeutics to prevent progression to severe COVID-19 remains a critical need.

Methods

Safety, clinical and antiviral efficacy of inhaled interferon-β1a (SNG001) were evaluated in a phase II randomized controlled trial on the ACTIV-2/A5401 platform (ClinicalTrials.govNCT04518410). Adult outpatients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection within 10 days of symptom onset were randomized and initiated either orally inhaled nebulized SNG001 given once daily for 14 days (n = 110) or blinded pooled placebo (n = 110) between February 10 and August 18, 2021.

Findings

The proportion of participants reporting premature treatment discontinuation was 9% among SNG001 and 13% among placebo participants. There were no differences between participants who received SNG001 or placebo in the primary outcomes of treatment emergent Grade 3 or higher adverse events (3.6% and 8.2%, respectively), time to symptom improvement (median 13 and 9 days, respectively), or proportion with unquantifiable nasopharyngeal SARS-CoV-2 RNA at days 3 (28% [26/93] vs. 39% [37/94], respectively), 7 (65% [60/93] vs. 66% [62/94]) and 14 (91% [86/95] vs. 91% [83/81]). There were fewer hospitalizations with SNG001 (n = 1; 1%) compared with placebo (n = 7; 6%), representing an 86% relative risk reduction (p = 0.07). There were no deaths in either arm.

Interpretation

In this trial, SNG001 was safe and associated with a non-statistically significant decrease in hospitalization for COVID-19 pneumonia.

Funding

The ACTIV-2 platform study is funded by the NIH. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UM1 AI068634, UM1 AI068636 and UM1 AI106701. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Keywords: Inhaled interferon, SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, ACTIV-2, Randomized clinical trial

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Exogenous interferons (IFN) represent a promising therapy for COVID-19 given their role in initiating the antiviral response in the respiratory tract and in vitro activity against SARS, MERS-CoV, and SARS-CoV-2. In addition, several studies have reported that insufficient type I IFN responses may play a role in progression to severe COVID-19, suggesting that type I IFN administration may be beneficial in preventing adverse outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infection. We searched PubMed, EMBASE, ClinicalTrials.gov, and the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform using the search terms COVID-19 OR SARS-CoV-2 OR severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 AND treatment AND interferon (Therapy/Broad [filter]) AND (Clinical Trial [filter]) from inception to February 2023. Among studies with published results, seven clinical trials enrolled hospitalized patients and randomized participants to receive type I IFN (IFN-beta 1a or 1b, either subcutaneous or orally inhaled), and three trials enrolled outpatients and randomized participants to receive subcutaneous type III IFN (Peginterferon Lambda).

Added value of this study

This study adds to other studies of IFN in COVID-19 by evaluating orally-inhaled nebulized IFN-β1a and evaluating both safety and efficacy in adult outpatients with mild-to-moderate COVID-19. In this phase 2 randomized, double-blind, pooled-placebo-controlled multicenter trial in 220 participants, orally-inhaled SNG001 did not accelerate the clearance of nasopharyngeal SARS-CoV-2 RNA nor did it decrease the time to symptom improvement. However, the proportion of participants who were hospitalized (1% vs. 6%) or had grade 3 or higher treatment emergent adverse events (3.6% vs. 8.2%) was numerically lower for SNG001 compared to placebo.

Implications of all the available evidence

The signal of fewer adverse events and lower numbers of hospitalizations in participants randomized to SNG001 compared with placebo warrant further evaluation in a larger phase 3 study powered to evaluate the efficacy of SNG001 to prevent progression to severe COVID-19.

Introduction

COVID-19 represents one of the most significant infectious threats to global public health in over a century. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 monoclonal antibodies administered soon after SARS-CoV-2 infection were shown to significantly reduce COVID-19-related hospitalizations and all-cause mortality early during the pandemic.1, 2, 3, 4 However, SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern have emerged with resistance to each of the monoclonal antibodies that have been used clinically.5 Clinical trials of direct acting antivirals, including remdesivir, nirmatrelvir plus ritonavir, and molnupiravir have also demonstrated a reduction in hospitalization among outpatients with mild-to-moderate COVID-19 who, based upon age and/or comorbid conditions, were at high-risk for progression to severe disease.6, 7, 8 However, the need for intravenous infusion of remdesivir, drug-drug interactions associated with nirmatrelvir/ritonavir, and a relatively reduced clinical efficacy of molnupiravir, heightens the need to evaluate additional therapeutics to prevent the progression to severe COVID-19.6, 7, 8

Exogenous interferon (IFN) is a promising therapeutic option against SARS-CoV-2 given data suggesting that endogenous IFN production may be impaired in individuals with progressive disease.9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 Early reports found that inborn errors of type I IFN immunity, including autosomal recessive IFNAR1 deficiency, were more common in patients with life-threatening COVID-19 pneumonia.9,12,15,16 Patients with COVID-19 pneumonia were also more likely to have neutralizing auto-antibodies against type I IFNs.17 These data suggest that insufficient type I IFN responses may play a role in disease progression of COVID-19, and that type I IFN administration may be beneficial in preventing adverse outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infection. The potential for type I IFN to have antiviral activity is supported by in vitro studies demonstrating inhibition of replication of multiple coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-2.11,13,14,16,18

Clinical trials of IFN therapeutics for COVID-19 have produced mixed results. Randomized controlled trials of subcutaneous IFN-β in hospitalized participants showed clinical benefit in some but not all studies.19, 20, 21, 22 Nebulized inhaled IFN-β (SNG001) was shown to be beneficial for hospitalized COVID-19 patients in a Phase 2 study,23 and has been shown to result in a robust local antiviral response in the lungs24 while limiting systemic exposure to IFN-β, which is associated with flu-like symptoms.25 More recently, a phase 3 randomized placebo-controlled trial of subcutaneous pegylated IFN-lambda (a type III IFN) in adult outpatients with SARS-CoV-2 infection who were at high risk for severe disease, and within seven days of symptom onset, demonstrated a 50% reduction in hospitalization or emergency department visit compared with placebo recipients suggesting that early administration of exogenous IFN might be beneficial.26

With the continued circulation of SARS-CoV-2 variants and limitations of current therapeutics, novel therapeutics to reduce time to improvement of symptoms, decrease viral replication, and prevent the progression to severe COVID-19 are needed. Here, we report the safety, virologic, and clinical outcomes of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial of nebulized orally-inhaled SNG001 in adult outpatients with mild-to-moderate COVID-19.

Methods

Trial design and oversight

ACTIV-2/A5401 (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT04518410) is a randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter phase 2/3 adaptive platform trial for the evaluation of therapeutics for adult outpatients with COVID-19 as previously described (see Supplementary Methods for the ACTIV-2/A5401 protocol).27 All participants for this phase 2 analysis were enrolled in the U.S. across 25 outpatient clinical research sites (listed in Supplementary Notes). The phase 2 component of ACTIV-2/A5401 was designed to evaluate safety and determine the efficacy of investigational agents to reduce the time to improvement in COVID-19 symptoms through study day 28 and reduce SARS-CoV-2 RNA from nasopharyngeal (NP) swabs through day 14. Findings from the double-blind placebo-controlled phase 2 evaluation of SNG001 are presented here.

Ethics

The protocol was approved by a central institutional review board (IRB), Advarra, with additional local IRB approval if required by participating sites. All participants provided written informed consent.

Participants

Adult outpatients 18 years and older, with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection by an FDA-authorized antigen or nucleic acid test from an upper respiratory sample collected within 10 days prior to study entry, self-reported COVID-19 symptoms (subjective fever or feeling feverish, cough, shortness of breath or difficulty breathing at rest or with activity, sore throat, body pain or muscle pain/aches, fatigue, headache, chills, nasal obstruction or congestion, nasal discharge, nausea or vomiting, diarrhea, and/or documented temperature >38 °C) within 24 h of study entry and symptom onset no more than 10 days from study entry were eligible for enrollment. During the study, symptom duration for eligibility was decreased from 10 (Protocol V3.0) to 8 (V4.0) to 7 (V6.0) days from study entry (Supplementary Protocols). At study launch, enrollment in the ACTIV-2 platform phase 2 studies was stratified by individuals at protocol-defined “lower” or “higher” risk of progression to severe COVID-19. During the study, the definition of high risk was updated to exclude individuals who had completed the primary series of an effective COVID-19 vaccine (Supplementary Protocols). Due to the availability of monoclonal antibody therapies found to be effective in reducing hospitalizations in high-risk adults with COVID-19, enrollment in the ACTIV-2 platform phase 2 studies was later restricted to individuals at “lower” risk of progression to severe COVID-19 (Supplementary Protocol). Participants who were pregnant, breastfeeding, or on chronic continuous supplemental oxygen were excluded. Complete eligibility criteria are provided in the Supplementary Protocol. Study entry was within 48 h of screening/consent and could have been performed on the same day as screening.

Randomization and blinding

Participants were randomized centrally at the time of enrollment using a web-based system and stratified by duration of symptoms prior to study entry (≤5 days vs. >5 days) and risk of progression to severe COVID-19 (higher vs. lower). Randomization occurred in two steps. In step 1, participants were randomized, with equal probability, to one of the investigational agent groups that was open to enrollment at the time (including agents with different routes of administration) for which they were eligible using random block size of four. Immediately following this first randomization step, the second randomization was to active agent or placebo within the randomized investigational agent group assigned in the first step, using a ratio of r:1, where r was the number of agents a participant was eligible to receive in step 1. Site staff and investigators were not blinded to agent group but, with the exception of unblinded pharmacists, were blinded to randomized treatment (i.e., active vs. placebo). For analysis, a pooled placebo control group was constructed and included all participants who received placebo in the trial who were concurrently eligible to be randomized to SNG001 (Fig. 1).

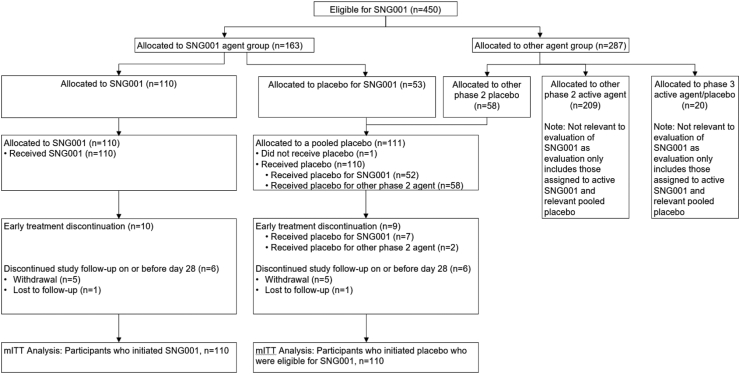

Fig. 1.

Consort diagram. The modified intent-to-treat (mITT) population consists of 220 participants who received at least one dose of study treatment, including 110 who received SNG001, 52 who received placebo for SNG001, and 58 who were eligible to receive SNG001 but were allocated to another phase 2 placebo. One additional participant was allocated to placebo for SNG001 but did not initiate treatment.

SNG001 and placebo administration

SNG001 (two pre-filled syringes each of 0.65 mL of interferon-β1a (SNG001) at a concentration of 12 MIU/mL) and placebo for SNG001 (two pre-filled syringes of 0.65 mL placebo solution) were self-administered as a single nebulized dose delivered over approximately 4 min via the Aerogen Ultra Nebulizer device once a day for 14 days. Further information about the investigational products are provided in the study protocol (Supplementary Methods). Study participants were trained by study staff to use the Aerogen Ultra device on day 0 (day of first dose) and shown an instructional YouTube video (Supplementary Notes). The first dose was administered either at the study site or at the participant’s home, with the remaining doses taken at home. Participants who were in the constructed pooled placebo group and randomized to other agent placebos, received placebos that were either orally or intravenously-administered. All participants and site staff were blinded to treatment allocation.

Adverse event and symptom assessments

Adverse event (AE) assessments were conducted during in person visits on study days 0, 3, 7, 14, and 28. Adverse events of special interest (AESI) included grade ≥2 palpitations during the dosing period and up to 24 h after last dose and grade ≥3 bronchospasm within 4 h of investigational agent/placebo administration.

Participants completed a daily study diary from day 0 (prior to first dose) through day 28 and recorded 13 targeted COVID-19 symptoms as absent, mild, moderate, or severe; symptoms included feeling feverish, cough, shortness of breath or difficulty breathing at rest or with activity, sore throat, body pain or muscle pain/aches, fatigue, headache, chills, nasal obstruction or congestion, nasal discharge (runny nose), nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

Virology

NP swabs were collected by research staff at days 0, 3, 7, and 14 using standardized swabs and collection procedures. Day 28 swabs were also initially collected, but starting in protocol v7.0, day 28 swabs were removed from the schedule of events and dropped from the primary virology outcome measure due to the high number of samples with results below the LLoQ. Samples were frozen, stored at −80 °C, and SARS-CoV-2 RNA measured at a central laboratory (University of Washington) using a quantitative Abbott m2000sp/rt platform.27,28 The assay limit of detection was 1.4 log10 copies/mL, lower limit of quantification (LLoQ) was 2 log10 copies/mL, and upper limit of quantification (ULoQ) was initially 7, then 8 log10 copies/mL. For samples with RNA levels greater than ULoQ, the assay was rerun with dilutions to obtain a quantitative value.

Serum and plasma biomarkers

Markers of inflammation and coagulation including lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), C-reactive protein (CRP), ferritin, D-dimer, prothrombin time (PT)/International normalized ratio (INR), activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), and fibrinogen were measured in real-time by a central clinical laboratory (PPD® Laboratory Services Global Central Labs) at days 0, 7, and 28.

Primary and secondary outcomes

The primary outcome measures included: 1) development of a grade 3 or higher treatment-emergent adverse event (TEAE) through day 28; 2) time to symptom improvement through 28 days of 13 targeted COVID-19 symptoms, defined as time from entry (day 0) to the first of two consecutive days where all symptoms reported as moderate or severe at day 0 were recorded as absent or mild, and all symptoms reported as mild or absent at day 0 were recorded as absent; and 3) SARS-CoV-2 RNA below LLoQ from NP swabs at days 3, 7, and 14.

Key secondary outcomes included the composite of all-cause hospitalization or death through day 28 and quantitative levels of SARS-CoV-2 RNA from NP swabs through day 28. Additional secondary outcomes included time-averaged total daily symptom scores from days 0 to 28, time-averaged shortness of breath or difficulty breathing scores from days 0 to 28, time to return to usual health for 2 consecutive days, time to return to usual health for 4 consecutive days, time to all symptoms absent for 4 consecutive days, number of missed doses, percentage of doses that were missed, and grade 2 or higher TEAEs. Daily total symptom scores were calculated by summing the scores for each symptom with absent scored as 0, mild as 1, moderate as 2, and severe as 3 (possible range of 0–39). The symptom diary also asked if they had returned to their pre-COVID-19 health (yes/no response).

Power analysis and sample size calculation

The planned sample size for phase 2 was 220 participants and was powered based on the primary virology outcome. With 110 participants in each arm and 100 participants in each arm with NP swabs available, there would be at least 82% power to detect a 20% absolute increase in the proportion of participants with SARS-CoV-2 RNA < LLoQ on a given day in the SNG001 arm compared to the placebo control arm using a two-sided 5% type I error rate.

Statistical analysis

The analysis population included all randomized participants who initiated SNG001 or concurrent pooled placebo.

The proportion of participants with grade 3 or higher TEAEs through day 28 was compared between arms using Fisher’s exact test due to small event numbers. The proportion of participants experiencing a grade 2 or higher TEAE was compared between arms using log-binomial regression and summarized with a risk ratio and corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). Serious adverse events (SAEs) and AESI were summarized descriptively by arm.

The proportion of participants with SARS-CoV-2 RNA < LLoQ was compared between arms across measurement times (days 3, 7, and 14) using Poisson regression. The regression model adjusted for day 0 log10-transformed SARS-CoV-2 RNA level and was fit using generalized estimating equations to handle repeated measures with an independent working correlation structure and robust standard errors. A risk ratio and 95% CI was summarized at each time. A joint test for an association across all post-entry study visits was assessed using a two-sided Wald test. Quantitative SARS-CoV-2 RNA levels were compared between arms using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests separately at each post-entry visit; undetectable results were analyzed as the lowest rank and values above the limit of detection but below the lower limit of quantification were analyzed as the second lowest rank.

The time to symptom improvement and other symptom-based time to event outcomes were compared between arms using the Gehan–Wilcoxon test. The time-averaged total symptom score and time-averaged shortness of breath or difficulty breathing score were also compared using a Wilcoxon test.

The cumulative probability of hospitalization or death through day 28 was estimated for each arm using Kaplan–Meier methods. Due to a small number of hospitalizations or deaths, the proportion who were hospitalized or died due to any cause through day 28 was compared between arms using Fisher’s exact test.

The proportion who missed at least one dose of SNG001 or placebo for SNG001 was compared between arms using log-binomial regression and summarized with a risk ratio (RR), a corresponding 95% CI, and a p-value based on the Wald test. The percentage of missed doses was compared between arms using a Wilcoxon test. Analysis of adherence was restricted to participants who received SNG001 or placebo for SNG001.

All tests were two-sided with 5% type I error rate. No adjustment was made for multiple comparisons across outcome measures. Statistical analyses were conducted in SAS 9.4.

Role of funding

The study sponsor, the NIH Division of AIDS, participated in the design of the study and reviewed and approved the protocol prior to study initiation. Oversight and responsibility for data collection were delegated by the sponsor to PPD clinical research, a Contract Research Organization (CRO). Safety laboratories and inflammatory and coagulation biomarkers were measured at PPD Laboratory Services Global Central Labs. A sponsor representative (ACJ) reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Results

Participant population and adherence to SNG001 or its placebo

A total of 110 participants were randomized to SNG001 and 111 to pooled placebo from 25 U.S. sites between February 10 and August 18, 2021 (Fig. 1). One participant randomized to placebo did not receive study medication and was excluded from all analyses. Among the 110 placebo recipients, 52 (47%) were randomized to placebo for SNG001 and 58 (53%) were randomized to a placebo for a different agent. The median age was 39 years, 55% reported female sex at birth, 55% identified as Hispanic/Latino, 10% as Black or African American, and 62% reported ≤5 days of symptoms at enrollment (Table 1). Most participants enrolled (94 [85%] in the SNG001 arm and 91 [83%] in the pooled placebo arm) did not meet the protocol definition of higher risk of progression to severe COVID-19. Most participants were not vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2, including 83% of participants randomized to placebo and 76% randomized to SNG001.

Table 1.

Baseline participant characteristics.

| SNG001 (N = 110) |

Placebo (N = 110) |

Total (N = 220) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), n (%) | |||

| <60 years | 106 (96%) | 103 (94%) | 209 (95%) |

| ≥60 years | 4 (4%) | 7 (6%) | 11 (5%) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 40 (31, 49) | 39 (33, 50) | 39 (32, 49) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Female | 66 (60%) | 54 (49%) | 120 (55%) |

| Male | 44 (40%) | 56 (51%) | 100 (45%) |

| Gender identity, n (%) | |||

| Cis-gender | 110 (100%) | 109 (99%) | 219 (>99%) |

| Transgender spectrum | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (<1%) |

| Race, n (%)a | |||

| White | 85 (78%) | 90 (82%) | 175 (80%) |

| Black or African American | 13 (12%) | 8 (7%) | 21 (10%) |

| Asian | 3 (3%) | 4 (4%) | 7 (3%) |

| Multiracial or other | 8 (7%) | 8 (7%) | 16 (7%) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 58 (53%) | 64 (58%) | 122 (55%) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 52 (47%) | 46 (42%) | 98 (45%) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), median (Q1, Q3) | 26.5 (24.1, 30.8) | 27.6 (24.7, 30.8) | 27.3 (24.5, 30.8) |

| Days from symptom onset to study day 0, n (%) | |||

| ≤5 days | 67 (61%) | 70 (64%) | 137 (62%) |

| >5 days | 43 (39%) | 40 (36%) | 83 (38%) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 5 (3, 6) | 4 (3, 6) | 5 (3, 6) |

| Higher risk of severe COVID-19 progression, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 16 (15%) | 19 (17%) | 35 (16%) |

| No | 94 (85%) | 91 (83%) | 185 (84%) |

| History of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 26 (24%) | 19 (17%) | 45 (20%) |

| No | 84 (76%) | 91 (83%) | 175 (80%) |

Race information was missing for one participant.

Twelve (5%) participants (6 SNG001, 6 pooled placebo) discontinued the study before day 28. Among participants who initiated SNG001 (n = 110) or its placebo (n = 52), 9% in the SNG001 arm and 13% receiving SNG001 placebo prematurely discontinued treatment. The mean percentage of missed doses (3.6% SNG001, 5.6% placebo; p = 0.07) and proportion with any missed doses (12.7% SNG001, 21.2% placebo; p = 0.17) was numerically lower among SNG001 participants than its placebo (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table S1).

Safety

There were 13 participants with a reported grade 3 or higher TEAE through day 28, including 4 (3.6%) SNG001 and 9 (8.2%) pooled placebo participants (p = 0.25) (Table 2). Grade 2 or higher TEAEs were reported by 24 (21.8%) SNG001 participants and 30 (27.3%) pooled placebo participants (risk ratio 0.80 [95% CI: 0.50, 1.28]; p = 0.35). Detailed summaries of grade 2 or higher TEAEs through day 28 by arm are provided in Supplementary Table S2. No participants experienced an AESI. Eight participants had an SAE, 1 (1%) among SNG001 participants and 7 (6%) among placebo participants, all of which were hospitalizations due to COVID-19. There were no deaths through day 28.

Table 2.

Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAE) through day 28.

| SNG001 (N = 110) |

Placebo (N = 110) |

Analysis result | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TEAEs, n (%) | |||

| Grade 1 | 14 (13) | 12 (11) | |

| Grade 2 | 20 (18) | 21 (19) | |

| Grade 3 | 4 (4) | 8 (7) | |

| Grade 4 | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | |

| Grade 5 (death) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Serious adverse events, n (%) | 1 (1) | 7 (6) | |

| Adverse events of special interesta, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Grade 3 or higher TEAE, n (%) | 4 (3.6) | 9 (8.2) | |

| Risk ratio | 0.44 | ||

| p-value (Fisher’s exact test) | p = 0.25 | ||

| Risk difference | −4.5% | ||

| Grade 2 or higher TEAE, n (%) | 24 (21.8) | 30 (27.3) | |

| Risk ratio [95% CI] | 0.80 [0.50, 1.28] | ||

| p-value (Wald test) | p = 0.35 | ||

| Risk difference [95% CI] | −5.5% [−16.8%, 5.9%] |

Table summarizes number of participants with at least one TEAE through day 28. Summaries by TEAE grade are based on the highest adverse event grade through day 28 for each participant.

The proportion of participants with Grade 3 or higher TEAEs was compared between arms using Fisher’s exact test. Risk ratios and risk differences were summarized, but confidence intervals were not calculated due to small number of events.

The proportion of participants with Grade 2 or higher TEAEs was compared using log-binomial regression and summarized with a risk ratio (RR), 95% Confidence Interval (CI), and p-value based on the Wald test. In addition, the difference in proportions was calculated, with 95% Wald CI based on the normal approximation to the binomial distribution.

Adverse Events of Special Interest included Grade ≥2 palpitations during the dosing period and up to 24 h after last dose and Grade ≥3 bronchospasm within 4 h of investigational agent/placebo administration.

Clinical outcomes

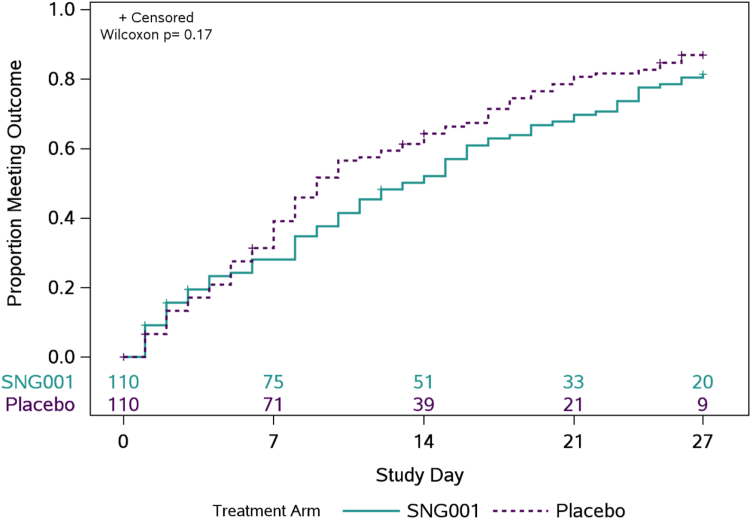

The median (Q1, Q3) time to symptom improvement was 13 (6, 24) days for SNG001 and 9 (5, 19) days for pooled placebo (p = 0.17) (Fig. 2). The estimated proportion of participants not meeting the definition of symptom improvement by 27 days was 19% for SNG001 and 13% for placebo.

Fig. 2.

Time (days) to all targeted symptoms improved from day 0 for two consecutive days. The primary clinical outcome was time to symptom improvement through 28 days of 13 targeted COVID-19 symptoms. The cumulative proportion of participants with all symptoms improved for 2 consecutive days was calculated using Kaplan–Meier methods. Numbers above the x-axis indicates the number of participants still in follow-up who have not previously had two consecutive days with all targeted symptoms improved.

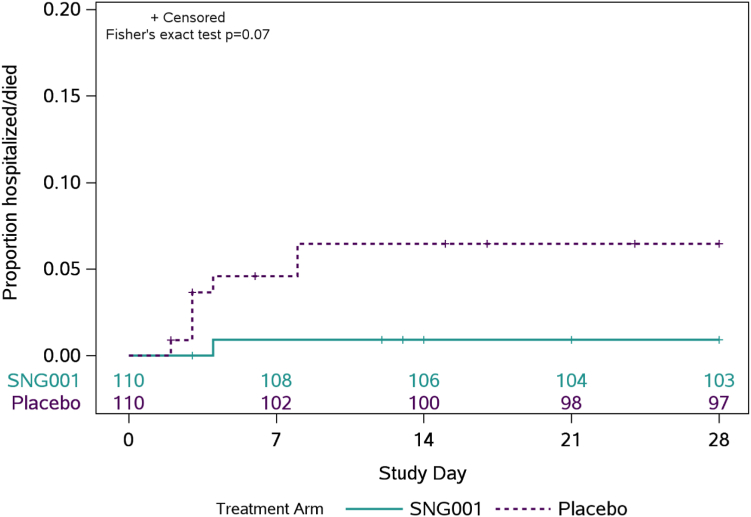

Fewer SNG001 participants (n = 1; 1%) were hospitalized relative to placebo (n = 7; 6%), (p = 0.07) (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table S3). All hospitalizations were due to COVID-19 pneumonia and were among unvaccinated individuals who did not meet the protocol definition of being at higher risk of progression to severe COVID-19. The median age (48 vs. 39 years) and proportion who were Hispanic/Latino (88% vs. 55%) were both higher among the hospitalized participants compared to the overall study population. Hospitalizations occurred a median of 3.5 days following study entry (range 2–8 days).

Fig. 3.

Cumulative incidence of hospitalization or death through day 28. Cumulative incidence of hospitalization or death is estimated by Kaplan–Meier method. Hospitalization is defined as ≥24 h of acute care, in a hospital or similar acute care facility, including Emergency Rooms or temporary facilities instituted to address medical needs of those with severe COVID-19 during the COVID-19 pandemic, through day 28. There were no deaths through day 28. Numbers above the x-axis indicates the number of participants still in follow-up who have not been hospitalized or died.

There was no evidence of treatment arm differences for other secondary clinical outcomes, including time to return to usual health for two consecutive days, time to return to usual health for four consecutive days, time to symptom absence for four consecutive days, time-averaged total symptom score, time-averaged shortness of breath or difficulty breathing score, or time-averaged total symptom score restricted to participants reporting moderate or severe shortness of breath or difficulty breathing at enrollment (Supplementary Table S4). When analysis was restricted to those individuals who were randomized within 5 days of symptom onset, observed differences in the proportion hospitalized and time to symptom improvement between SNG001 and placebo recipients were similar to overall findings (Supplementary Figures S1 and S2).

SARS-CoV-2 RNA levels

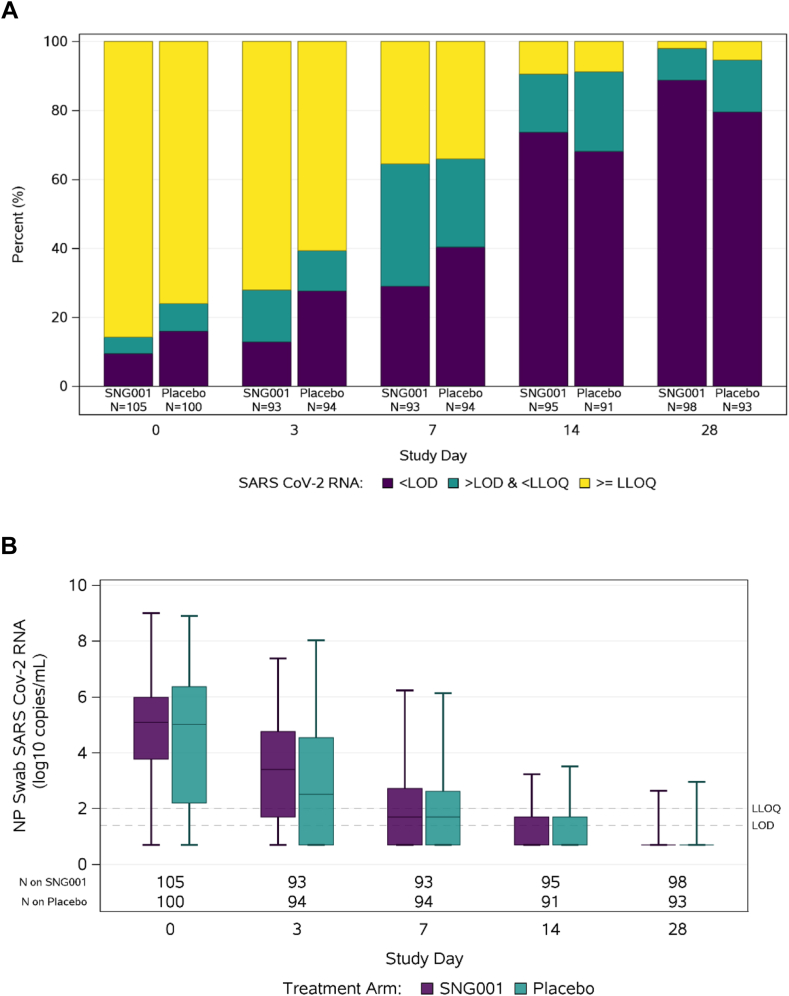

SARS-CoV-2 RNA analysis were restricted to participants with results available at a given timepoint. At day 0, the proportion with SARS-CoV-2 RNA levels < LLoQ from NP swabs was 14% [15/105] in the SNG001 arm vs. 24% [24/100] in the placebo arm (Fig. 4A, Supplementary Table S5). The observed proportion of participants with SARS-CoV-2 RNA < LLoQ from NP swabs was lower among SNG001 participants at day 3 compared to placebo (28% [26/93] vs. 39% [37/94], respectively) but similar on days 7 (65% [60/93] vs. 66% [62/94]) and 14 (91% [86/95] vs. 91% [83/91]). Differences in the proportion of participants with SARS-CoV-2 RNA < LLoQ from NP swabs between arms were not statistically significant at day 3, 7, or 14 (RR 0.74, 1.02, and 1.05 adjusted for log10 SARS-CoV-2 RNA level at day 0; joint Wald test p = 0.41). There was no significant difference between arms in quantitative NP SARS-CoV-2 RNA levels at any timepoint (Fig. 4B, Supplementary Table S6). Findings regarding NP SARS-CoV-2 RNA levels were similar when analysis was restricted to those individuals who were randomized within 5 days of symptom onset (Supplementary Figure S3).

Fig. 4.

SARS-CoV-2 RNA levels from nasopharyngeal swabs by study visit. (A) The primary virologic outcome was proportion of participants with SARS-CoV-2 RNA below lower limit of quantification (LLoQ) from nasopharyngeal (NP) swabs at days 3, 7, and 14 between participants randomized to SNG001 and placebo. (B) Comparison of SARS-CoV-2 RNA levels between participants randomized to SNG001 or placebo at study entry and days 3, 7, 14, and 28, with horizontal line = median, box = interquartile range, whiskers = minimum/maximum. SARSCoV-2 RNA was measured using a quantitative Abbott m2000sp/rt platform with a limit of detection (LOD) of 1.4 log10 copies/mL, lower limit of quantification (LLoQ) of 2 log10 copies/mL, and upper limit of quantification (ULoQ) of initially 7, then 8 log10 copies/mL.

Given the chance imbalance in the proportion of participants with SARS-CoV-2 RNA levels < LLoQ from NP swabs, the proportion of participants < LLoQ on Day 3, 7, and 14 was compared between arms in a post-hoc analysis adjusting for log10 SARS-CoV-2 RNA level at day 0 and restricted to participants with quantifiable viral load at day 0. In this analysis, there was no difference in the proportion of participants with SARS-CoV-2 RNA levels < LLoQ from NP swabs between SNG001 and placebo at day 3 (19% [15/79] and 23% [15/65], respectively; RR 0.82 [95% CI: 0.43, 1.53]), day 7 (58% [46/79] and 59% [37/63], respectively; RR 0.98 [95% CI: 0.75, 1.29]) or day 14 (88% [69/78] and 89% [55/62], respectively; RR 0.99 [95% CI: 0.87, 1.13]) (Supplementary Table S7). Similarly, when analysis of quantitative NP SARS-CoV-2 RNA levels were limited to only those participants with quantifiable viral load at day 0, there was no difference in median (IQR) SARS-CoV-2 levels in NP swabs from SNG001 or placebo recipients at day 0, 3, 7, or 14 (Supplementary Table S8). In a post-hoc analysis among participants with quantifiable viral load at day 0 comparing quantitative SARS-CoV-2 RNA levels at day 3 (adjusted for day 0 values) using a linear regression model accounting for left-censoring of values below the LLoQ, there was no significant difference in the change in log10-tranformed day 3 SARS-CoV-2 RNA levels between SNG001 and placebo [adjusted mean change for participants with a day 0 RNA of 5 log10 copies/mL: −1.51 log10 copies/mL for SNG001 and −1.79 log10 copies/mL for placebo; adjusted mean difference: 0.27 log10 copies/mL; 95% CI: −0.28, 0.82].

Inflammatory and coagulation biomarkers

There were significant differences between SNG001 and placebo in the median fold change between days 0 and 7 in CRP, LDH, and fibrinogen levels (1.09 vs. 0.44, p < 0.001; 1.09 vs. 1.02, p = 0.032; 1.00 vs. 0.90, p = 0.003, respectively) (Supplementary Table S9). The median fold changes over time were similar in both arms by day 28 post treatment.

Discussion

In this phase 2 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled evaluation of orally nebulized SNG001 for the treatment of predominantly lower risk and unvaccinated adults with acute mild-to-moderate COVID-19, SNG001 was safe and associated with similar numbers of adverse events, but did not accelerate the clearance of nasopharyngeal SARS-CoV-2 RNA nor lead to a quicker time to symptom improvement compared with placebo. However, participants randomized to SNG001 had fewer hospitalizations compared with participants randomized to placebo, although the difference was not statistically significant.

The similar number of adverse events, including the primary safety endpoint of grade 3 or higher treatment emergent adverse events, compared with placebo support the safety profile of SNG001 in adults with mild-to-moderate COVID-19. There was also a lower number of hospitalizations among participants randomized to SNG001 compared with placebo. All 8 hospitalizations were due to COVID-19 and occurred among lower risk, unvaccinated, individuals. Hospitalization rates among unvaccinated persons in May 2021 were reported to be 17.7 times higher than vaccinated persons supporting the role of unvaccinated status as a risk factor for progression to severe disease including hospitalization.29 Although not powered to detect a difference in progression to severe COVID-19, the reduction in hospitalization among SNG001 compared with placebo recipients warrants further evaluation in a larger study.

This study adds to other clinical trials of IFN by focusing early in the course of infection when antiviral strategies are likely to be most effective and by its unique delivery–directly to the lower respiratory tract, the site of severe COVID-19. The lack of clinical benefit of therapeutic interferons in many clinical trials of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 including ACTT-3 and Solidarity21,22 may be in part due to the timing of drug administration. Since SARS-CoV-2 replication peaks early, at or around the time of symptom onset, antivirals are likely most effective when delivered early in the infection time course as seen with monoclonal antibodies and direct acting antivirals therapies.2,3,6,7 While participants in the ACTT-3 trial were enrolled a mean of 8.7 days from symptom onset, participants in the SNG001 arm of the ACTIV-2 trial were enrolled a mean of 4.7 days from symptoms onset.22 Indeed, early treatment with subcutaneous interferon beta-1b started within the first week of symptoms when given along with lopinavir/ritonavir and ribavirin, or, more recently, when given along with remdesivir, has shown benefit in alleviating symptoms and/or shortening viral shedding.19,20 Similarly, Peginterferon Lambda delivered subcutaneously in “high risk” COVID-19 outpatients randomized a mean 3.3 days from symptom onset demonstrated a significant reduction in hospitalization and/or emergency room visits; this effect was predominantly seen among the subgroup of participants randomized within 3 days of symptom onset.30 As both type I and type III IFN activate the same dominant JAK-STAT signaling pathway and can inhibit SARS-CoV-2 both in vitro and in vivo, these studies together support protective roles for administration of both exogenous type I (IFN-β1a or b) and type III (Peginterferon Lambda) IFN early in COVID-19.11,13,16,31

An important difference between our trial and other trials of therapeutic interferons is the site of drug delivery. While IFN-β1a was delivered via a subcutaneous injection in ACTT-3 and Solidarity in 3–4 doses, SNG001 in this study and in a prior study of hospitalized patients25 is orally inhaled via a nebulizer directly to the lower respiratory tract—the primary site of infection driving severe COVID-19—in 14 doses. The site of drug delivery has important implications for interpreting the lack of antiviral efficacy in the current study as viral sampling occurs in a different location from drug delivery. In this study, we observed no statistically significant difference in nasal shedding at days 3, 7, or 14, similar to trials of subcutaneous IFN-β1a in hospitalized patients and in a phase 2 study of subcutaneous pegylated IFN-λ in outpatients with COVID-19.22,32 Given the route of SNG001 delivery (oral inhalation with lower respiratory tract penetration), the nasopharynx receives little or no direct delivery of SNG001—this could have contributed to the absence of an antiviral difference between active agent and placebo in NP swabs while also possibly preventing progression to severe disease by inducing an antiviral state in the lower respiratory tract.

We observed a significant increase in the median fold change of inflammatory markers, CRP, LDH and fibrinogen, all of which are acute phase reactants, during treatment with SNG001 compared with those receiving placebo. The increase in these markers of inflammation and coagulation are consistent with the pro-inflammatory mechanism of action of interferon and could potentially explain the lack of benefit in time to symptom improvement between groups. The increases in CRP, LDH, and fibrinogen were transient however, and returned to similar levels as placebo by day 28.

While the strengths of this study include a randomized, placebo-controlled design with standardized virology and symptom assessment, there are limitations that should be considered when interpreting these results. Foremost, the phase 2 studies within the ACTIV-2 platform are powered on the primary virologic outcome and not designed to detect a difference in hospitalizations. Additionally, most participants enrolled did not meet the protocol definition of higher risk for severe COVID-19 further limiting the ability to detect a difference in this outcome. In addition, 80% of participants enrolled were unvaccinated limiting the evaluation of efficacy in a vaccinated population. While, this trial enrolled participants a mean 4.7 days from symptom onset—earlier than participants in other IFN trials including Solidarity and ACTT 3, this is later than trials evaluating other investigational outpatient therapeutics that demonstrated an antiviral effect, including nirmatrelvir/ritonavir, molnupiravir, remdesivir, and peginterferon Lambda.

Access to diagnostics, vaccines and therapeutics has been a significant challenge throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. SNG001 is a self-administered, nebulized, inhaled, therapeutic that can be delivered at home. However, the requirements for electricity to power the nebulizing device and training are potential barriers to treatment. Although a 14-day course was used in this and prior studies of SNG001, the optimal duration of therapy is not known. Importantly, all hospitalizations occurred by 8 days from enrollment potentially suggesting that a shorter duration of treatment could be possible.

In conclusion, orally inhaled nebulized SNG001 was safe and well tolerated but did not reduce SARS-CoV-2 RNA levels in the nasopharynx, nor decrease time to improvement of COVID-19 symptoms in outpatients with mild-to-moderate COVID-19. A signal of fewer hospitalizations with SNG001 compared to placebo warrants further investigation as a therapeutic to prevent progression to severe COVID-19.

Contributors

P.J., K.W.C., M.J.G., M.D.H., C.Mo., M.J.M., P.D.M., A.C.J., J.Z.L., C.F., C.Mc., D.A.W., E.S.D., J.J.E., J.S.C., U.S., D.M.S., and W.F. conceived and designed the research. P.J., K.W.C., J.Z.L., D.A.W., E.S.D., U.S., D.M.S., and W.F. generated data. M.J.G., M.D.H., C.Mo., and C.Mc. analyzed the data. P.J., K.W.C., M.J.G., M.D.H., C.Mo., M.J.M., P.D.M., A.C.J., J.Z.L., C.F., C.Mc., D.A.W., E.S.D., J.J.E., J.S.C., U.S., D.M.S., and W.F. interpreted the data. P.J., K.W.C., M.J.G., and W.F. drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Data sharing statement

The authors confirm that all data underlying the findings are fully available. Data are available under restricted access due to ethical restrictions. Access can be requested by submitting a data request at https://submit.mis.s-3.net/ and will require the written agreement of the AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG) and the manufacturer of the investigational product. Requests will be addressed as per ACTG standard operating procedures. Completion of an ACTG Data Use Agreement may be required.

Declaration of interests

P.J. has received research funding to the institution from NIH/NIAID.

K.W.C. has received research funding to the institution from NIH/NIAID and Merck Sharp & Dohme; has served as a consultant for Pardes Biosciences; and has received honoraria for CME from International Antiviral Society-USA.

M.J.G. has received research funding to the institution from NIH/NIAID.

M.D.H. has received research funding to the institution from NIH/NIAID.

C.M. has received research funding to the institution from NIH/NIAID.

M.J.M. has received research funding to the institution from NIH/NIAID.

P.D.M. is an employee of Synairgen; Synairgen covered cost of supplying SNG001 and placebo for the study; Patents filed in relation to use of SNG001 to treat viral lung disease; Shareholder.

A.C.J. report no competing interests.

J.Z.L. has received research funding to the institution from NIH/NIAID.

C.F. has received research funding to the institution from NIH/NIAID.

C.Mc. has received research funding to the institution from NIH/NIAID.

D.A.W. has received funding to the institution to support research and honoraria for advisory boards and consulting from Gilead Sciences, Eli Lilly, and Merck.

E.S.D. receives consulting fees from Gilead Sciences, Merck, and GSK/ViiV and research support through the institution from Gilead Sciences and GSK/ViiV.

J.J.E. has received research funding to the institution from NIH/NIAID; is an ad hoc consultant to GSK/VIR, Merck, Gilead; data monitoring committee (DMC) chair for Adagio Phase III studies.

W.F. has received research funding to the institution from Ridgeback Biopharmaceuticals, served on adjudication committees for Janssen, Syneos, served as a consultant for Roche and Merck, and has received honoraria for CME from Medlearning group.

J.S.C. has received research funding to the institution from NIH/NIAID; has consulted for Merck and Company.

U.S. has received research funding to the institution from NIH/NIAID and Pfizer; Scientific advisory board Burroughs Wellcome Fund.

D.M.S. has received research funding to the institution from NIH/NIAID; has consulted for the following companies VxBiosciences, Model Medicines, Bayer Pharmaceuticals, Lucira, Pharma Holdings, and Evidera.

Acknowledgements

We thank the study participants, site staff, site investigators, and the entire ACTIV-2/A5401 study team; the AIDS Clinical Trials Group; the ACTG Laboratory Center; Frontier Science; the Harvard Center for Biostatistics in AIDS Research (CBAR) and ACTG Statistical and Data Analysis Center (SDAC); the ACTIV-2 Community Advisory Board (CAB); the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID)/Division of AIDS (DAIDS); the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health and the Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines (ACTIV) partnership; and the PPD clinical research business of Thermo Fisher Scientific. We also thank the members of the ACTIV-2/A5401 data and safety monitoring board.

Footnotes

Collaborators: ACTIV-2/A5401 Study Team, See list of Study site investigators in the Supplementary Material.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102250.

Contributor Information

William Fischer, Email: WFischer@med.unc.edu.

ACTIV-2/A5401 Study Team:

Kara Chew, David (Davey) Smith, Eric Daar, David Wohl, Judith Currier, Joseph Eron, Arzhang Cyrus Javan, Michael Hughes, Carlee Moser, Mark Giganti, Justin Ritz, Lara Hosey, Jhoanna Roa, Nilam Patel, Kelly Colsh, Irene Rwakazina, Justine Beck, Scott Sieg, Jonathan Li, Courtney Fletcher, William Fischer, Teresa Evering, Rachel Bender Ignacio, Sandra Cardoso, Katya Corado, Prasanna Jagannathan, Nikolaus Jilg, Alan Perelson, Sandy Pillay, Cynthia Riviere, Upinder Singh, Babafemi Taiwo, Joan Gottesman, Matthew Newell, Susan Pedersen, Joan Dragavon, Cheryl Jennings, Brian Greenfelder, William Murtaugh, Jan Kosmyna, Morgan Gapara, Akbar Shahkolahi, Mark J. Main, Gerald Pierone, Juliana Elliott, Jeffrey Jacobson, Leila Hojat, Julie Pasternak, Jonathan Berardi, Celine Arar, Yevgeniy Bukhman, Manish Jain, Eugene Bukhman, Sadia Shaik, Timothy Hatlen, Kelly Dooley, Becky Becker, Adaliah Wilkins, Jose Pérez, Eloy Roman, Heriberto Fernández, Keila Hoover, James Renfroe, Mauney Weldon, Genei Bougher, Carlos Malvestutto, Heather Harber, Robyn Cicarella, Gene Neytman, Jack Herman, Craig Herman, Mariam Aziz, Joan Swiatek, Divya Pathak, Madhu Choudhary, Jennifer Sullivano, Olayemi Osiyemi, Myriam Izquierdo, Odelsey Torna, Aleen Khodabakhshian, Samantha Fortier, Constance Benson, Steven Hendrickx, Rosemarie Ramirez, Anne Luetkemeyer, Suzanne Hendler, Dennis Dentoni-Lasofsky, Mario Castro, Leslie Spikes, Chase Hall, Jonathan Oakes, Amy James Loftis, Pablo Tebas, William Short, Sarah McGuffin, Chris Jonsson, Rachel Presti, and Alem Haile

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Chen P., Nirula A., Heller B., et al. SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody LY-CoV555 in outpatients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:229–237. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2029849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gottlieb R.L., Nirula A., Chen P., et al. Effect of bamlanivimab as monotherapy or in combination with etesevimab on viral load in patients with mild to moderate COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;325:632–644. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.0202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gupta A., Gonzalez-Rojas Y., Juarez E., et al. Early treatment for Covid-19 with SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody sotrovimab. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1941–1950. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2107934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weinreich D.M., Sivapalasingam S., Norton T., et al. REGN-COV2, a neutralizing antibody cocktail, in outpatients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:238–251. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2035002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Imai M., Ito M., Kiso M., et al. Efficacy of antiviral agents against omicron subvariants BQ.1.1 and XBB. N Engl J Med. 2023;388:89–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2214302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gottlieb R.L., Vaca C.E., Paredes R., et al. Early remdesivir to prevent progression to severe Covid-19 in outpatients. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:305–315. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2116846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hammond J., Leister-Tebbe H., Gardner A., et al. Oral nirmatrelvir for high-risk, nonhospitalized adults with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:1397–1408. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2118542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jayk Bernal A., Gomes da Silva M.M., Musungaie D.B., et al. Molnupiravir for oral treatment of Covid-19 in nonhospitalized patients. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:509–520. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2116044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blanco-Melo D., Nilsson-Payant B.E., Liu W.C., et al. Imbalanced host response to SARS-CoV-2 drives development of COVID-19. Cell. 2020;181:1036–1045.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan J.F., Chan K.H., Kao R.Y., et al. Broad-spectrum antivirals for the emerging Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J Infect. 2013;67:606–616. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2013.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cinatl J., Morgenstern B., Bauer G., Chandra P., Rabenau H., Doerr H.W. Treatment of SARS with human interferons. Lancet. 2003;362:293–294. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13973-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clementi N., Ferrarese R., Criscuolo E., et al. Interferon-beta-1a inhibition of severe acute respiratory syndrome-Coronavirus 2 in vitro when administered after virus infection. J Infect Dis. 2020;222:722–725. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Falzarano D., de Wit E., Martellaro C., Callison J., Munster V.J., Feldmann H. Inhibition of novel beta coronavirus replication by a combination of interferon-alpha2b and ribavirin. Sci Rep. 2013;3:1686. doi: 10.1038/srep01686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hensley L.E., Fritz L.E., Jahrling P.B., Karp C.L., Huggins J.W., Geisbert T.W. Interferon-beta 1a and SARS coronavirus replication. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:317–319. doi: 10.3201/eid1002.030482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Q., Bastard P., Liu Z., et al. Inborn errors of type I IFN immunity in patients with life-threatening COVID-19. Science. 2020;370 doi: 10.1126/science.abd4570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sheahan T.P., Sims A.C., Leist S.R., et al. Comparative therapeutic efficacy of remdesivir and combination lopinavir, ritonavir, and interferon beta against MERS-CoV. Nat Commun. 2020;11:222. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13940-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bastard P., Rosen L.B., Zhang Q., et al. Autoantibodies against type I IFNs in patients with life-threatening COVID-19. Science. 2020;370 doi: 10.1126/science.abd4585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dahl H., Linde A., Strannegard O. In vitro inhibition of SARS virus replication by human interferons. Scand J Infect Dis. 2004;36:829–831. doi: 10.1080/00365540410021144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hung I.F., Lung K.C., Tso E.Y., et al. Triple combination of interferon beta-1b, lopinavir-ritonavir, and ribavirin in the treatment of patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19: an open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2020;395:1695–1704. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31042-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tam A.R., Zhang R.R., Lung K.C., et al. Early treatment of high-risk hospitalized coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients with a combination of interferon beta-1b and remdesivir: a phase 2 open-label randomized controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2023;76:e216–e226. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciac523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.WHO Solidarity Trial Consortium. Pan H., Peto R., et al. Repurposed antiviral drugs for Covid-19 - interim WHO solidarity trial results. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:497–511. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2023184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalil A.C., Mehta A.K., Patterson T.F., et al. Efficacy of interferon beta-1a plus remdesivir compared with remdesivir alone in hospitalised adults with COVID-19: a double-bind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9:1365–1376. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00384-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Monk P.D., Marsden R.J., Tear V.J., et al. Safety and efficacy of inhaled nebulised interferon beta-1a (SNG001) for treatment of SARS-CoV-2 infection: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9:196–206. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30511-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Djukanovic R., Harrison T., Johnston S.L., et al. The effect of inhaled IFN-beta on worsening of asthma symptoms caused by viral infections. A randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:145–154. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201312-2235OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gottberg K., Gardulf A., Fredrikson S. Interferon-beta treatment for patients with multiple sclerosis: the patients' perceptions of the side-effects. Mult Scler. 2000;6:349–354. doi: 10.1177/135245850000600510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reis G., Moreira Silva E.A.S., Medeiros Silva D.C., et al. Early treatment with pegylated interferon lambda for Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2023;388:518–528. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2209760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chew K.W., Moser C., Daar E.S., et al. Antiviral and clinical activity of bamlanivimab in a randomized trial of non-hospitalized adults with COVID-19. Nat Commun. 2022;13:4931. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-32551-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berg M.G., Zhen W., Lucic D., et al. Development of the RealTime SARS-CoV-2 quantitative laboratory developed test and correlation with viral culture as a measure of infectivity. J Clin Virol. 2021;143 doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2021.104945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Havers F.P., Pham H., Taylor C.A., et al. COVID-19-associated hospitalizations among vaccinated and unvaccinated adults 18 years or older in 13 US States, January 2021 to April 2022. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182:1071–1081. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.4299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reis G., Moreira Silva E.A.S., Medeiros Silva D.C., et al. Early treatment with pegylated interferon lambda for COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2023;388:518–528. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2209760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lazear H.M., Schoggins J.W., Diamond M.S. Shared and distinct functions of type I and type III interferons. Immunity. 2019;50:907–923. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jagannathan P., Andrews J.R., Bonilla H., et al. Peginterferon lambda-1a for treatment of outpatients with uncomplicated COVID-19: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Nat Commun. 2021;12:1967. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-22177-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.