Summary

Starch accounts for up to 90% of the dry weight of rice endosperm and is a key determinant of grain quality. Although starch biosynthesis enzymes have been comprehensively studied, transcriptional regulation of starch‐synthesis enzyme‐coding genes (SECGs) is largely unknown. In this study, we explored the role of a NAC transcription factor, OsNAC24, in regulating starch biosynthesis in rice. OsNAC24 is highly expressed in developing endosperm. The endosperm of osnac24 mutants is normal in appearance as is starch granule morphology, while total starch content, amylose content, chain length distribution of amylopectin and the physicochemical properties of the starch are changed. In addition, the expression of several SECGs was altered in osnac24 mutant plants. OsNAC24 is a transcriptional activator that targets the promoters of six SECGs; OsGBSSI, OsSBEI, OsAGPS2, OsSSI, OsSSIIIa and OsSSIVb. Since both the mRNA and protein abundances of OsGBSSI and OsSBEI were decreased in the mutants, OsNAC24 functions to regulate starch synthesis mainly through OsGBSSI and OsSBEI. Furthermore, OsNAC24 binds to the newly identified motifs TTGACAA, AGAAGA and ACAAGA as well as the core NAC‐binding motif CACG. Another NAC family member, OsNAP, interacts with OsNAC24 and coactivates target gene expression. Loss‐of‐function of OsNAP led to altered expression in all tested SECGs and reduced the starch content. These results demonstrate that the OsNAC24‐OsNAP complex plays key roles in fine‐tuning starch synthesis in rice endosperm and further suggest that manipulating the OsNAC24‐OsNAP complex regulatory network could be a potential strategy for breeding rice cultivars with improved cooking and eating quality.

Keywords: NAC transcription factor, starch biosynthesis, endosperm, transcriptional regulation, rice grain quality

Introduction

Starch is the most abundant form of reserve carbohydrate in higher plants, and it accounts for up to 90% of the dry weight of the rice endosperm. Starch is a mixture of complex water‐insoluble glucan polymers that consists mainly of two forms: basically linear amylose and highly branched amylopectin (Keeling and Myers, 2010; Zeeman et al., 2010). The composition and physicochemical properties of these two types of starch polymers are closely related to the cooking and eating quality of rice grains (Huang et al., 2021; Jeon et al., 2010; Zeeman et al., 2010). Of the two, the amylose content (AC) is one of the most important factors that affects the cooking and eating quality of rice. Generally, rice with a lower AC is softer after cooking than rice with a higher AC. Therefore, cultivating rice varieties with low to intermediate AC (10%–20%) is a major target for improving rice cooking and eating quality (Huang et al., 2020a, 2021; Li et al., 2016; Tian et al., 2009).

Starch biosynthesis in cereal endosperm is a complex biochemical process involving the coordination of multiple enzymes (James et al., 2003; Jeon et al., 2010). After decades of in‐depth research, the enzymes involved in starch biosynthesis in endosperm and their functions are now well characterized. ADP‐glucose pyrophosphorylase (AGPase) is the rate‐limiting enzyme in the initial stage of starch biosynthesis, converting glucose‐1‐phosphate into the activated glucosyl donor ADP‐glucose (ADPG) for subsequent starch synthesis (Jeon et al., 2010; Keeling and Myers, 2010). In cereals, AGPase is a heterotetramer (α2β2) that is composed of two large subunits (LSUs) and two small subunits (SSUs; Ballicora et al., 2004; Jeon et al., 2010). Studies have shown that when OsAGPL2, a gene that encodes the LSU of AGPase, and OsAGPS2, which encodes the SSU of AGPase, are mutated, starch synthesis is dramatically reduced in the rice endosperm and small, round starch granules accumulate, leading to a wrinkled endosperm phenotype (Tuncel et al., 2014). In the rice endosperm, granule‐bound starch synthase I (OsGBSSI), encoded by the Waxy (Wx)/OsGBSSI gene, is a major enzyme responsible for amylose synthesis (Sano, 1984; Wang et al., 1990). Loss‐of‐function of OsGBSSI eliminates amylose production and results in opaque white endosperm, indicating that the essential role of OsGBSSI is in amylose synthesis (Terada et al., 2002). Unlike amylose, amylopectin synthesis requires a variety of enzymes including soluble starch synthases (SSs), starch branching enzymes (SBEs) and debranching enzymes (DBEs). There are a total of nine SS isoenzymes in rice, including OsSSI, OsSSIIa, OsSSIIb, OsSSIIc, OsSSIIIa, OsSSIIIb, OsSSIVa, OsSSIVb and OsSSV, and each has a distinct preference for the elongation of amylopectin molecules of different chain lengths (Bahaji et al., 2014; Irshad et al., 2021; Jeon et al., 2010; Keeling and Myers, 2010). SBEs (OsSBEI, OsSBEIIa and OsSBEIIb) are responsible for the formation of branch points via α‐1,6‐glycoside bonds, while DBEs (OsISA1, OsISA2, OsISA3 and OsPUL) function in removing improper or excessively branched chains by hydrolysing the α‐1,6‐glycoside bonds (Dinges et al., 2003; Fujita et al., 1999; Guan et al., 1997; Han et al., 2007; Li et al., 2009; Nakamura, 2002; Nakamura et al., 1996). When these amylopectin‐synthesis enzymes are dysfunctional, the development of the rice endosperm is affected. For instance, down‐regulation or loss‐of‐function of one or more of the OsSSIIa, OsSSIIIa, OsSSIVb, OsSBEI, OsSBEIIb and OsISA1 genes will result in obvious defects in starch synthesis and starch granule formation, which leads to abnormal endosperm (Crofts et al., 2017; Fujita et al., 2003, 2007, 2009; Lee et al., 2017; Satoh et al., 2003; Tanaka et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2011a; Zhou et al., 2016). Plastidial phosphorylase (OsPho1) is thought to extend the chain length of the oligosaccharide primer during the initial stage of starch synthesis at low temperatures. Mutation of the OsPho1 gene leads to a severe reduction in starch accumulation, smaller starch granules and seeds with shrunken endosperm at 20 °C, while seeds develop normally at 30 °C (Satoh et al., 2008).

At present, several transcription factors (TFs) involved in the regulation of rice starch synthesis have been identified. OsBP5, a TF in the MYC family, binds to the Wx promoter and co‐regulates the expression of Wx with its interacting protein OsEBP‐89, which then affects the content of amylose in rice (Zhu et al., 2003). OsbZIP58 promotes starch biosynthesis by binding and activating six starch‐synthesis enzyme‐coding genes (SECGs); loss‐of‐function mutations in OsbZIP58 caused a decrease in the total starch content, altered chain length distribution of amylopectin and chalky endosperm (Wang et al., 2013). The heterotrimer complex NF‐YB1‐YC12‐bHLH144 directly activates the expression of the Wx gene to regulate AC and grain quality (Bello et al., 2019). The OsMADS14‐NF‐YB1 heterodimer directly promotes the expression of Wx and OsAGPL2 to regulate the contents of amylose and total starch (Feng et al., 2022). Mutations in NF‐YB1 and OsMADS14 both result in reduced AC and chalky endosperm (Bello et al., 2019; Feng et al., 2022). RSR1, which encodes an AP2/EREBP TF, participates in regulating AC and the fine structure of amylopectin by negatively regulating the expression of several SECGs (Fu and Xue, 2010). In addition, other types of proteins also participate in regulating rice starch synthesis at the transcriptional and protein levels. For example, FLO2 encodes a nuclear‐localized TPR‐binding protein that can interact with bHLH TFs to regulate the expression of SECGs (She et al., 2010). However, despite the aforementioned findings, the molecular mechanisms involved in the regulation of starch biosynthesis in rice endosperm are still largely unknown.

NAC TFs, one of the largest family of plant‐specific TFs, are found in a wide variety of plants and play important roles in all aspects of plant growth and development. To date, more than 150 NAC family members have been identified in rice, and several of them are reported to participate in root development, leaf senescence, biotic and abiotic stress responses, phytohormone signal transduction and so on (Kim et al., 2016; Nuruzzaman et al., 2010, 2013; Olsen et al., 2005b). Recently, there is emerging evidence to show that NAC TFs bind directly to the promoters of SECGs to regulate starch biosynthesis in cereal endosperm (Gao et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2019). For instance, ZmNAC128 and ZmNAC130 transactivate the maize brittle2 gene (which encodes the AGPase small subunit) (Zhang et al., 2019), OsNAC20 and OsNAC26 activate transcription of the OsSSI and OsPUL genes in rice (Wang et al., 2020), and TaNAC019 transactivates the expression of the TaSSIIa gene in wheat (Gao et al., 2021).

In this study, we characterized a NAC family TF, OsNAC24 (LOC_Os05g34310), which is highly expressed in the immature endosperm of rice grains. Loss‐of‐function of OsNAC24 resulted in changes in the expression of several SECGs, which moderately affected starch biosynthesis; although the composition, structure and physicochemical properties of starch are changed, there were no negative effects on endosperm appearance and starch granule morphology. Further studies showed that OsNAC24 regulates starch synthesis mainly through the activation of OsGBSSI and OsSBEI expression. Moreover, another NAC family member, OsNAP, interacts with OsNAC24 to enhance the expression of target genes. These results provide new insights into the transcriptional regulatory mechanisms of starch synthesis in rice endosperm and suggest a potential approach to improve rice cooking and eating quality by manipulating the regulatory network of the OsNAC24‐OsNAP complex.

Results

Loss‐of‐function of OsNAC24 alters starch biosynthesis in rice endosperm

To identify new regulators of starch biosynthesis in rice endosperm, we screened rice gene expression databases and selected several genes that are highly or specifically expressed in immature rice endosperm. One of these candidate genes, named OsNAC24 (LOC_Os05g34310), encodes a NAC TF. To study the function of OsNAC24 in rice, we generated osnac24 mutants using CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing technology in the japonica cultivar ‘Nipponbare’. The four small guide RNAs targeted the promoter (T1 and T2) and the first (T3) and second (T4) exons of the OsNAC24 gene (Figure S1a). We obtained three independent lines, osnac24‐1, osnac24‐2 and osnac24‐3, in the T0 generation (Figure S1a and Table S1). DNA sequencing analysis showed that osnac24‐1 contained 9‐bp, 19‐bp and 2‐bp deletions in the first, second and fourth target sites, respectively, resulting in the production of a 95‐amino acid polypeptide due to the premature stop codon generated by a frameshift mutation. osnac24‐2 contained a 1‐bp insertion in the first target site and a 555‐bp deletion encompassing the second to fourth target sites. osnac24‐3 contained a 2‐bp deletion in the first target site and a 582‐bp deletion that removed the region between the second and fourth target sites. Both osnac24‐2 and osnac24‐3 have lost their original translational start codons and are predicted to produce truncated proteins lacking 104 amino acids at the N terminus by initiating translation from the ATG at nucleotides 313–315 in the coding sequence. Subsequently, we isolated homozygous mutants without T‐DNA in the T2 populations, which eliminated potential nonspecific effects due to the insertion of foreign DNA sequences (Figure S1b). qRT‐PCR analysis showed that the expression levels of OsNAC24 in the endosperms of the three mutants were <0.1 of that in the wild‐type (WT) at 7 days after flowering (DAF, Figure S1c). Moreover, no OsNAC24 protein could be detected in mutant endosperms by Western blotting using an OsNAC24‐specific antibody (Figure S1d). These results indicated that all three onac24 mutants were knockout mutants.

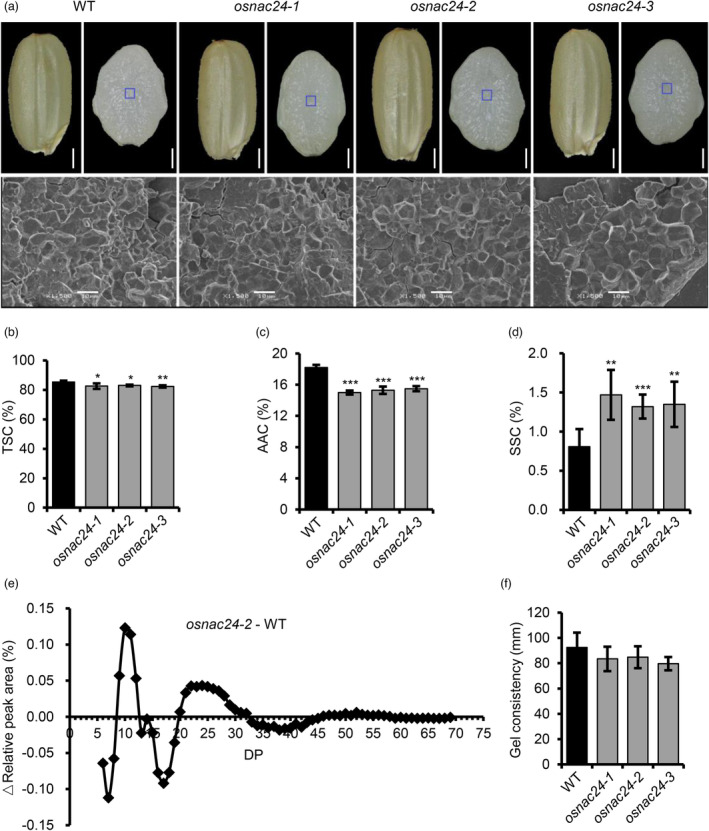

The endosperms of the three osnac24 mutants were semitransparent in appearance with no chalkiness, which was the same as observed in WT seeds (Figure 1a). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) of transverse sections of mature endosperm revealed that starch granules in the osnac24 mutants were tightly packed irregular polyhedrons and were indistinguishable from WT starch granules (Figure 1a). However, the total starch content (TSC) and apparent amylose content (AAC) decreased from 85.3% to 82.3%–83.0% and 18.2% to 15.0%–15.5%, respectively (Figure 1b,c). Corresponding to the changes in TSC and AAC, the soluble sugar content (SSC) increased from 0.8% to 1.3%–1.5% (Figure 1d). To evaluate the effects of the osnac24 mutations on the fine structure of amylopectin, the chain length distribution of amylopectin was analysed using high‐performance anion‐exchange chromatography (HPAEC). The starches from the osnac24 mutants had a significantly lower proportion of short chains of degree of polymerization (DP) 16–19 and long chains of DP 35–42, whereas the proportions of short chains of DP 10–12 and intermediate chains of DP 21–30 increased significantly (Figure 1e). We found that the starch gel consistency did not differ significantly between WT and the osnac24 mutants (Figure 1f) while the enthalpy change (ΔH) values of starches from all three osnac24 mutants were higher than in the WT (Table S2). Collectively, these results indicate that loss‐of‐function of OsNAC24 has a slight effect on starch biosynthesis in rice endosperm, but has no significant effects on endosperm appearance and starch granule morphology.

Figure 1.

Mutation of OsNAC24 alters starch biosynthesis in rice endosperm. (a) Brown rice grains and cross sections of grains (upper panel), and starch granules (lower panel) from the wild‐type (WT) ‘Nipponbare’ and the three osnac24 mutants. The blue boxes indicate the central area of the mature endosperms where starch granules were analysed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Scale bars = 1 mm (brown rice grains in the upper panels); 0.5 mm (grain cross sections in the upper panels); 10 μm (lower panels). (b‐d) Total starch content (TSC), apparent amylose content (AAC) and soluble sugar content (SSC), respectively, in endosperms of WT and the osnac24 mutants. (e) Difference in the amylopectin chain length distribution between WT and osnac24‐2 starches. (f) Gel consistency of starches from WT and the osnac24 mutants. Values in (b), (c), (d) and (f) are given as mean ± SD of five biological replicates. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, Student's t‐test.

Gene expression pattern of OsNAC24 and subcellular localization of the OsNAC24 protein

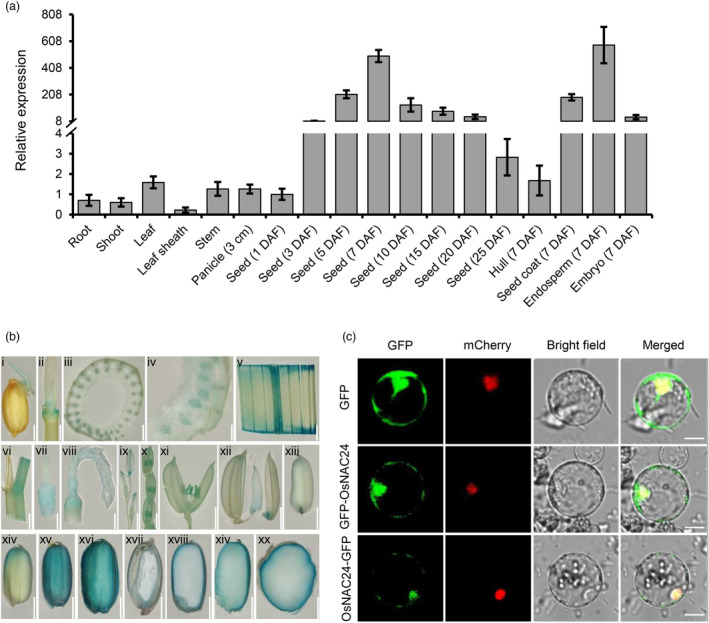

In order to further understand the function of OsNAC24 in rice, we investigated the expression pattern of OsNAC24 in ‘Nipponbare’ plants. qRT‐PCR analyses revealed that OsNAC24 was expressed ubiquitously in all tissues examined, including roots and shoots at the vegetative stage and leaves, leaf sheathes, stems, young panicles and seeds at the reproductive stage (Figure 2a). The expression of OsNAC24 in developing seeds was significantly higher than that in other tissues, and it peaked at 7 DAF. Moreover, the highest level of OsNAC24 expression was detected in endosperms, and the expression was also higher in seed coats than in embryos and hulls at 7 DAF (Figure 2a). To examine OsNAC24 gene expression in more detail, we generated transgenic plants carrying an OsNAC24 promoter‐β‐glucuronidase (GUS) fusion construct and performed histochemical GUS analysis on the tissues. We found that OsNAC24 is weakly expressed in coleoptiles, nodes, leaves, leaf sheathes, young panicles, spikelets and anthers (Figure 2bi–xi), but it is predominantly expressed in developing seeds (Figure 2bxii–xx). These results agree with the expression pattern determined by qRT‐PCR.

Figure 2.

Expression pattern and subcellular localization of OsNAC24. (a) Relative expression levels and expression profile of OsNAC24 in ‘Nipponbare’. Total RNA was extracted from roots and shoots at 7 days after germination, from leaves, leaf sheathes, stems and young panicles before flowering, and from developing seeds. Actin1 was used as an internal control for gene expression normalization from the qRT‐PCR data. Data are mean ± SD of four biological replicates. (b) OsNAC24 promoter‐GUS expression pattern in transgenic plants. GUS expression in coleoptiles at 1 day after germination (i), nodes (Terada et al.), cross sections of nodes (iii and iv), leaves and leaf sheathes (v and vi), young panicles (vii and viii), spikelets (ix‐xi), endosperms at 3 DAF (xii), 5 DAF (xiii), 7 DAF (xiv), 10 DAF (xv) and 15 DAF (xvi), vertical sections of endosperms at 5 DAF (xvii), 7 DAF (xviii) and 10 DAF (xiv) and cross section of endosperm at 15 DAF (xx). Scale bars = 2 mm (i, ii, v–viii, xi–xiv); 0.4 mm (iii and iv); 5 mm (ix and x); and 1 mm (xx). (c) Subcellular localization of OsNAC24. GFP, GFP‐OsNAC24 and OsNAC24‐GFP fusion genes under control of the CaMV 35S promoter were expressed transiently in rice protoplasts. The mCherry‐NLS fusion, which is mCherry fused with the NLS peptide of OsNAP (VTGKRKRSSD), was co‐expressed to indicate the nuclei. Scale bars = 10 μm. DAF, days after flowering.

Protein structure prediction using cNLS Mapper (http://nls‐mapper.iab.keio.ac.jp/cgi‐bin/NLS_Mapper_form.cgi) showed that there are no nuclear localization signals (NLSs) present in the sequence of the OsNAC24 protein. To investigate the subcellular localization of OsNAC24, the OsNAC24 gene coding sequence was cloned upstream and downstream of the GFP gene under control of the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S (CaMV 35S) promoter to give C‐ and N‐terminal OsNAC24‐GFP protein fusions. We transiently expressed these constructs in rice protoplasts and found that the green fluorescence signals from both the C‐ and N‐ terminal fusion proteins were distributed in the cytosol and the nucleus (Figure 2c).

OsNAC24 functions as a transcription activator

Sequence analysis showed that OsNAC24 encodes a putative protein of 310 amino acid residues and that this protein contains a typical, highly conserved NAC domain in the N terminus and a variable regulatory region in the C terminus (Figure 3a and Figure S2). The NAC domain is further divided into five subdomains, A to E. Previous phylogenetic analysis of NAC TFs in rice has shown that OsNAC24 belongs to the Va (1)/NAP subfamily of NAC proteins (Liang et al., 2014), which has six members in rice (Figure S2). Transcriptional activation assays showed that the activation domain is localized in the C‐terminal region of OsNAP, whereas the C and D subdomains function as a transcriptional repressor to reduce the activation ability of the C terminus (Liang et al., 2014). In order to investigate the transactivation ability of OsNAC24, we performed a yeast one‐hybrid assay. We found that the full‐length OsNAC24 possesses strong transcriptional activation activity, indicating that it is a transcriptional activator (Figure 3b). Deletion analysis showed that amino acids 219–233 are essential for the transcriptional activation activity of OsNAC24, confirming that the activation domain is located in the C‐terminal region (Figure 3b). To determine whether the NAC subdomains of OsNAC24 have repression activity, we constructed plasmids ΔN2 to ΔN9, which contain various lengths of the truncated NAC domain. All truncated fragments showed similar activation activities to the full‐length NAC domain, indicating that the subdomains do not have transcriptional repression activity (Figure 3c). Interestingly, the C‐terminal region alone did not display any transactivation activity. When any of the truncated NAC domains were fused to the C‐terminal region, the resulting proteins showed similar transcriptional activation activity to that of the full‐length NAC domain (Figure 3c), implying that transcriptional activation activity of the C terminus depends on N‐terminal subdomains. These results indicate that OsNAC24 functions as a transcriptional activator and further suggest that NAC proteins participate in diverse regulatory mechanisms.

Figure 3.

Transcriptional activation activity assay of OsNAC24 and truncated OsNAC24 proteins. (a) Schematic diagram showing the structure of the OsNAC24 protein; A‐E indicate the five NAC subdomains. Numbers indicate the positions of the amino acid residues within the protein. (b) Diagrams showing the structure of C‐terminal truncated OsNAC24 proteins (left) and their transcriptional activation activities in yeast cells (right). Full‐length and truncated coding sequences of the OsNAC24 gene were fused in frame to the 3′‐end of GAL4 DNA‐binding domain sequence (GAL4 BD) in the pGBKT7 vector to construct the effector vectors. The empty pGBKT7 vector was used as the negative control. All effector vectors were transformed into yeast strain Y2HGold. AbA, Aureobasidin A. (c) Schematic diagrams showing the structures of N‐terminal truncated OsNAC24 proteins (left) and their transcriptional activation activities (right). The full‐length and truncated coding sequences of OsNAC24 gene were fused in frame to the 3′‐end of the LexA DNA‐binding domain (LexA BD) in the pEG202 vector to construct the effector vectors. A plasmid in the which GAL4 activation domain (GAL4 AD) was fused to the LexA BD was used as the positive control, and the empty pEG202 vector was used as the negative control. All effector vectors were co‐transformed with the reporter vector pSH18‐34 into yeast strain EGY48.

Mutation of OsNAC24 affects the expression of starch‐synthesis enzyme‐coding genes

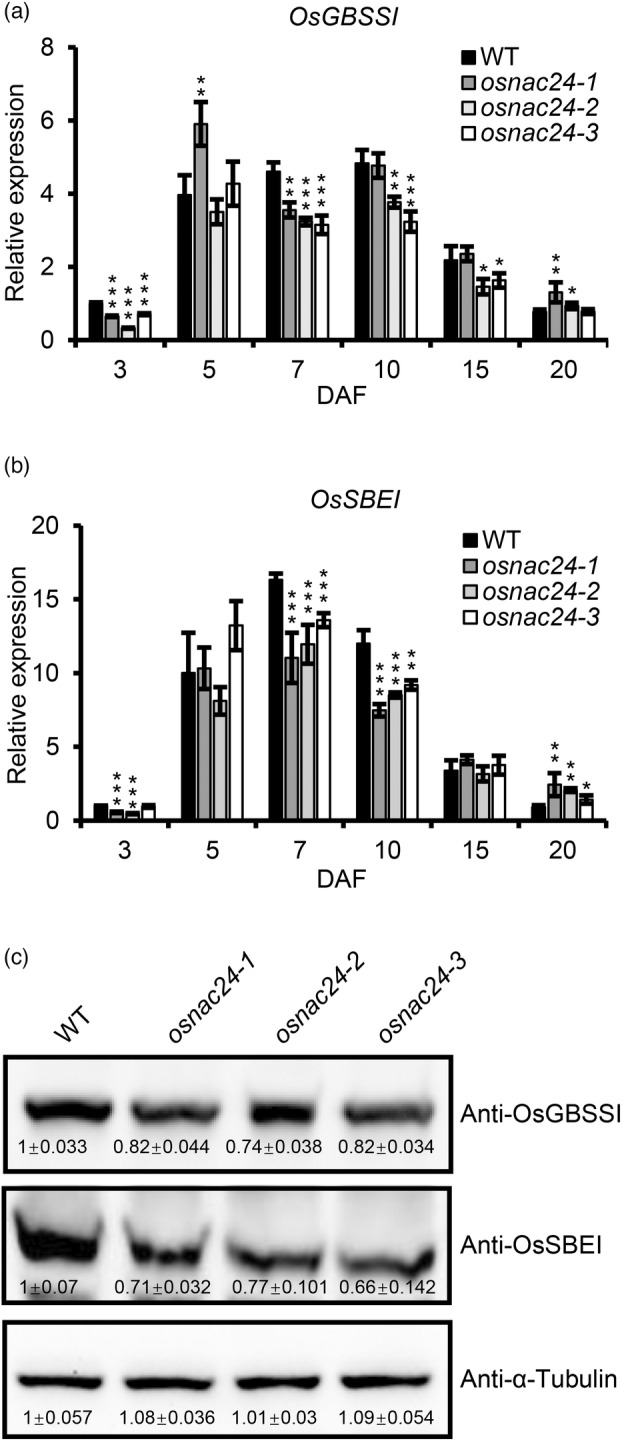

Because starch biosynthesis is altered in the osnac24 mutants, we hypothesized that the loss‐of‐function of OsNAC24 may affect the expression of genes which encode starch‐synthesis enzymes. Some SECGs, such as OsAGPS2b, OsAGPL2, OsGBSSI, OsSSI, OsSSIIa, OsSSIIIa, OsSSIVb, OsSBEI, OsSBEIIb, OsISA1, OsISA2 and OsPho1, are thought to play essential roles in starch biosynthesis, because their transcripts increase rapidly after 3 DAF, when starch synthesis begins in the endosperm (Ohdan et al., 2005). Several genes, including OsGBSSI, OsSBEI, OsSSIIIa and OsSSIVb, were down‐regulated in osnac24 mutant endosperm at 5 to 10 DAF, while OsSSI was up‐regulated (Figure 4a,b and Figure S3). The expression levels of several genes were also changed in the osnac24 mutants at other times, although the expression levels were relatively lower during those days. For example, OsGBSSI, OsAGPS2b, OsAGPL2, OsSSIIIa and OsSSIVb were down‐regulated at 3 DAF, and OsSSIIa was down‐regulated at 3 DAF and up‐regulated at 20 DAF. We further compared the protein contents of these starch‐synthesis enzymes between the WT and the mutants at 7 DAF (Figure 4c and Figure S4), when the expression of OsNAC24 was at its highest level (Figure 2a). Consistent with the gene expression levels, the protein abundances of OsGBSSI and OsSBEI were lower in the osnac24 mutants. However, there were no significant differences in the protein contents of OsSSI, OsSSIIIa and OsSSIVb between the WT and the mutants. It is worth noting that the reduction in OsGBSSI protein content was consistent with the decrease in the amylose contents in the osnac24 mutants (Figure 1c). Moreover, the pattern of changes in chain length distribution in the osnac24 mutants (Figure 1e) was similar to the ossbe1 mutant, in which the proportions of short chains with DP 12 to 21 and long chains with DP ≥37 were decreased while the proportions of short chains with DP ≤10 and intermediate chains with DP 24 to 34 were increased (Satoh et al., 2003). Therefore, it is reasonable to think that the changes in amylose content and the amylopectin chain length profiles in the osnac24 mutants were mainly caused by the reduction in the contents of the OsGBSSI and OsSBEI proteins.

Figure 4.

Expression of OsGBSSI and OsSBEI was decreased in the osnac24 mutants. (a and b) Expression profiles of OsGBSSI and OsSBEI in developing endosperm. Total RNA was extracted from endosperms at 3, 5, 7, 10, 15 and 20 DAF. UBQ10 was used as the internal control for normalization of gene expression. Data are the mean ± SD of four biological replicates. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, Student's t‐test. (c) Western blot analysis of OsGBSSI and OsSBEI in developing endosperm. Total proteins were extracted from 7 DAF endosperms of WT and the three osnac24 mutants, separated by SDS‐PAGE, transferred to PVDF membranes and detected with the corresponding antibodies. Each lane was loaded with 50 μg of total endosperm proteins. The experiments were conducted three times independently, with similar results each time. α‐Tubulin was used as the loading control. Data are the mean ± SD of three biological replicates.

OsNAC24 regulates expression of starch‐synthesis enzyme‐coding genes by directly binding to their promoters

To test whether SECGs are direct targets of OsNAC24, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP‐seq) analysis. We generated transgenic plants overexpressing OsNAC24 (Figure S5a,b) and collected endosperms at 7–9 DAF for the ChIP‐seq assay. All genes directly bound by OsNAC24 were analysed and nine genes encoding starch‐synthesis enzymes were identified (Table S3). OsAGPS1, OsSSIIb and OsSSIIIb were not analysed in the osnac24 mutants because the expression of these three genes declines to very low levels after 5 DAF in WT plants (Ohdan et al., 2005). For the other six genes, the expression of OsSBEIIb was not changed, while the expression levels of OsAGPS2 (OsAGPS2b is one of the transcripts encoded by OsAGPS2), OsAGPL2, OsSSIIa, OsSSIVb and OsSBEI were different in the osnac24 mutants (Figure 4 and Figure S3).

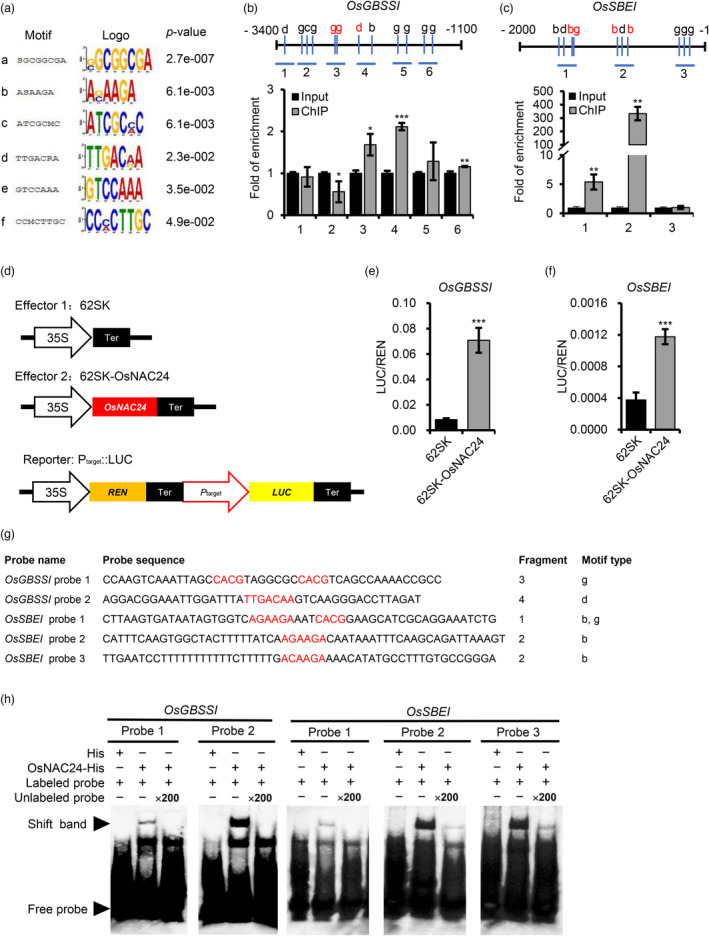

De novo motif analysis of the ChIP‐enriched regions by MEME‐ChIP (https://meme‐suite.org/meme/doc/meme‐chip.html?man_type=web) identified six candidate OsNAC24‐binding motifs, which we designated a to f (Figure 5a). Generally, NAC TFs preferentially bind to the core‐binding motif CACG (Olsen et al., 2005a). We next analysed the promoter sequences of the SECGs in which the expression was changed in the osnac24 mutants. We found that the b, c, d and CACG (hereafter termed motif g) motifs are present in the promoter regions of six genes: OsGBSSI, OsSBEI, OsAGPS2, OsSSI, OsSSIIIa and OsSSIVb (Figure 5b,c and Figure S6a–d). To ascertain whether OsNAC24 binds to these promoters, we performed quantitative PCR‐based chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP‐PCR) assays using the same endosperm materials used in the ChIP‐seq analysis. We found that at least one DNA fragment containing OsNAC24‐binding motifs was enriched for each of the six genes, demonstrating that OsNAC24 regulates the expression of these genes by directly binding to their promoters in vivo (Figure 5b,c and Figure S6a–d).

Figure 5.

OsNAC24 binds directly to the promoters of the OsGBSSI and OsSBEI genes and activates their transcription. (a) Enrichment of six motifs (Bahaji et al.) in the OsNAC24‐direct target promoters identified by MEME‐ChIP software. (b and c) Binding of OsNAC24 to the promoters of OsGBSSI and OsSBEI shown by ChIP‐PCR assays. Since the first intron is located at −1160 bp to −38 bp upstream of the translation initiation codon in the OsGBSS1 gene, the sequence from −3400 bp to −1100 bp upstream of the translation initiation codon of OsGBSS1 was analysed. The upper panels show schematic diagrams of the OsGBSS1 and OsSBEI promoters. Blue vertical lines indicate the possible OsNAC24‐binding motifs. The lower‐case letters above the vertical lines indicate the types of motifs from (a). Red letters indicate the motifs analysed by EMSA in (g) and (h). Blue horizontal lines indicate the PCR amplicons used in the ChIP‐PCR assays. The lower panels show the relative fold enrichment of the promoter fragments of OsGBSS1 and OsSBEI determined by the ChIP‐PCR assay with an anti‐OsNAC24 antibody. The Actin1 promoter was used as the internal control. Data are mean ± SD of three replicates. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, Student's t‐test. (d) Schematic diagrams of the effector and reporter constructs used in the dual‐luciferase assays. 35S, CaMV 35S promoter; REN, Renilla luciferase gene; LUC, firefly luciferase gene; P target, target gene promoter; Ter, transcriptional terminator. (e and f) Transcriptional activation of OsGBSSI and OsSBEI expression by OsNAC24 in rice protoplasts. The LUC gene was driven by the OsGBSSI (about −3400 bp to −1 bp of the start codon) and OsSBEI (about −2000 bp to −1 bp of the start codon) promoters, respectively. The tested promoters are indicated above each panel. Relative luciferase activities (LUC/REN) were measured in rice protoplasts co‐transfected with different combinations of effector and reporter plasmids. The empty 62SK vector was used as the negative control. Data are mean ± SD of four replicates. ***P < 0.001, Student's t‐test. (g) Probes used in the EMSAs. Motif sequences are shown in red. ‘Fragment’ indicates the promoter regions analysed in (b) and (c), and ‘Motif type’ refers to the motifs shown in part (a). (h) EMSAs were used to analyse the binding of OsNAC24 to motifs b, d and g in the promoters of OsGBSSI and OsSBEI. Probes were labelled with biotin. The unlabelled probes were added at a 200‐fold molar excess of the labelled probes. Black arrowheads indicate the shifted bands (up) and the free probe bands (down).

To confirm the role of OsNAC24 in regulating the expression of six SECGs, we performed transient transcription dual‐luciferase assays using the promoters of these genes (Figure 5d). After co‐transfection with the reporter vectors, the relative luciferase activities of rice protoplasts containing the 62SK‐OsNAC24 construct were higher than in protoplasts transfected with the empty vector 62SK (Figure 5e,f and Figure S6e–g). These results indicate that OsNAC24 binds to the promoters of the OsGBSS1, OsSBEI, OsAGPS2, OsSSI and OsSSIIIa genes to activate their expression in vivo. However, OsNAC24 did not transactivate the expression of OsSSIVb (Figure S6h).

OsNAC24 regulates starch synthesis mainly through the direct activation of OsGBSS1 and OsSBEI expression (Figure 4 and Figure 5b–f). ChIP‐PCR assays revealed that motifs b, d and g are present in the enriched fragments from the OsGBSS1 and OsSBEI gene promoter regions (Figure 5b,c). To determine whether OaNAC24 binds to these motifs, we performed electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs). Competitive EMSAs showed that motif d (TTGACAA) of the OsGBSS1 gene promoter and motif b (AGAAGA and ACAAGA) of the OsSBEI gene promoter were preferentially bound by OsNAC24, while motif g (CACG) of the OsGBSS1 gene promoter and motif b and g of the OsSBEI gene promoter were bound by OsNAC24 weakly (Figure 5g,h). Motif g was also present in the enriched fragments from the promoters of the OsAGPS2, OsSSI, OsSSIIIa and OsSSIVb genes (Figure S6a–d), and the EMSAs showed that OsNAC24 preferentially binds to motif g of the OsSSI gene promoter (Figure S7), implying that sequences flanking these core‐binding sites may affect the relative OsNAC24‐binding strength.

Competitive binding assays showed that OsNAC24 binds specifically to motifs d (TTGACAA) and g (CACG) that are located in the OsGBSS1 promoter region (Figure 5g,h). The binding specificity was further evaluated by mutating the motif sequences. When these motifs were mutated, OsNAC24 was unable to bind to either motif d or g (Figure S8a,b). The point mutation analyses of both motifs showed that mutations in the second nucleotide (A) of motif g and the sixth nucleotide (A) of motif d significantly decreased the binding capacity of OsNAC24, indicating that these two nucleotides are essential for OsNAC24 to bind to DNA (Figure S8c,d).

Overexpression of OsNAC24 causes chalky endosperm and increased amylose content

ChIP‐PCR and dual‐luciferase assays showed that OsNAC24 binds to the promoters of OsGBSSI and OsSBEI and activates their expression (Figure 5b–f). In order to better understand the function of OsNAC24, we analysed the starch granule morphology and starch content in OsNAC24‐overexpression plants. Unlike the semitransparent endosperm of WT grains, mature grains of the overexpression plants exhibited chalky endosperm phenotypes, mainly due to chalkiness in the central and dorsal parts of the endosperms (Figure S5c). SEM analysis of endosperm transverse sections revealed that WT starch granules are irregular polyhedrons and are densely packed, whereas the starch granules in grains from the overexpression plants were smaller, spherical and loosely packed (Figure S5c). There were no significant differences in TSC between the WT and overexpressing plants (Figure S5d). However, the AAC was increased in the endosperm of the overexpression plants compared with the WT (Figure S5e). These results indicate that overexpression of OsNAC24 changes starch composition and starch granule morphology, which subsequently affects endosperm appearance.

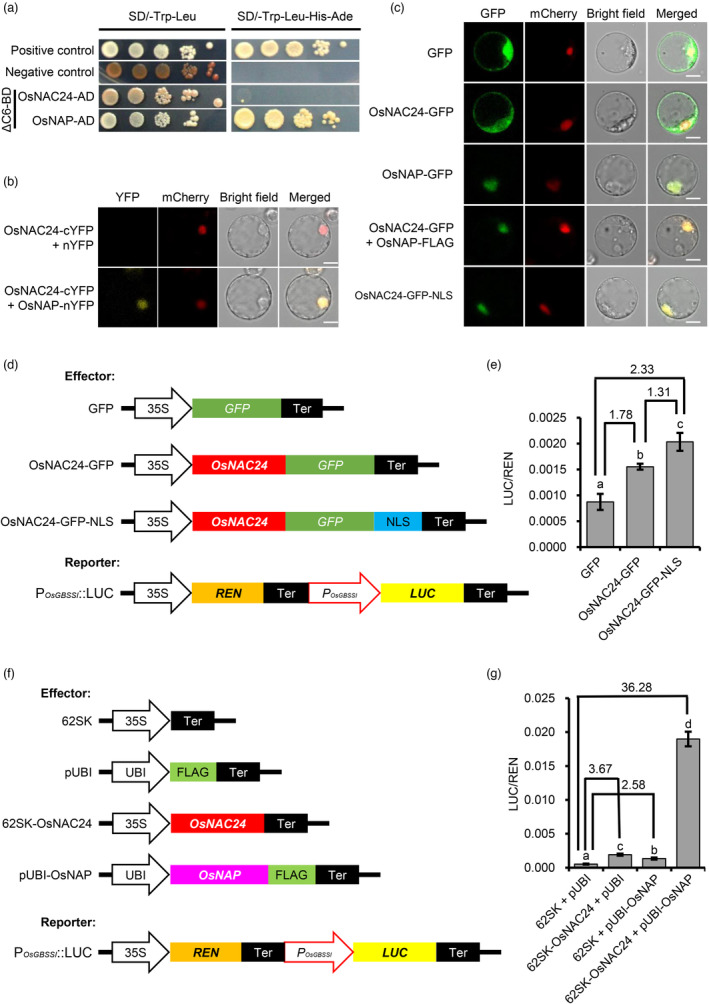

OsNAP interacts with OsNAC24 and promotes nuclear translocation of OsNAC24

To identify proteins that may interact with OsNAC24, we performed yeast two‐hybrid screening using the truncated OsNAC24 protein, ∆C6, as bait. The ∆C6 protein has no transcriptional activation activity due to the deletion of amino acids 219–310 (Figure 3b). The identified positive interacting proteins included OsNAP, which belongs to the same Va (1)/NAP subfamily as OsNAC24. The possible physical interaction between OsNAC24 and OsNAP was examined using yeast two‐hybrid (Y2H) and bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) assays. Y2H assays showed that OsNAC24 can interact with OsNAP in yeast cells, but not with itself (Figure 6a). In the BiFC experiments, the yellow fluorescent protein signal was detected in the nuclei of rice protoplasts (Figure 6b), confirming a direct interaction between OsNAC24 and OsNAP.

Figure 6.

OsNAP interacts with OsNAC24 and facilitates nuclear localization and transactivation activity of OsNAC24. (a) Yeast two‐hybrid assay of the interaction between OsNAC24 and OsNAP. Yeast cells transformed with pGBKT7‐53 and pGADT7‐T were used as the positive control, and yeast transformed with pGBKT7‐Lam and pGADT7‐T were used as the negative control. (b) Bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) analysis of the interaction between OsNAC24 and OsNAP. Scale bars, 10 μm. (c) The effects of OsNAP and a nuclear localization sequence (NLS) on the subcellular localization of OsNAC24 in rice protoplasts. The mCherry‐NLS fusion was co‐expressed with the OsNAC24 and OsNAP constructs to indicate the nuclei in (b) and (c). Scale bars, 10 μm. (d) and (f) Schematic diagrams of the effector and reporter constructs used in the dual‐luciferase assays. 35S, CaMV 35S promoter; UBI, UBIQUITIN gene promoter; REN, Renilla luciferase gene; LUC, firefly luciferase gene; P OsGBSSI , OsGBSSI gene promoter; Ter, transcriptional terminator; FLAG, FLAG epitope tag. (e) and (g) Dual‐luciferase assays in rice protoplasts. The LUC gene was driven by the OsGBSSI promoter (about −3400 bp to −1 bp of the start codon). Relative luciferase activities (LUC/REN) were measured in rice protoplasts co‐transfected with different combinations of effector and reporter plasmids. Data are mean ± SD of four replicates. Significant differences were determined by the one‐way ANOVA with the post hoc Dunnett's multiple comparisons test. The different lower‐case letters indicate significant differences at P < 0.05.

We next examined the effect of OsNAP on the subcellular localization of OsNAC24. We transiently expressed the OsNAP‐GFP fusion protein in rice protoplasts and found that the fusion protein localizes to the nucleus (Figure 6c), which confirmed a previous finding that OsNAP is a nuclear‐localized protein (Zhou et al., 2013). Unlike OsNAP, the OsNAC24‐GFP fusion localized to both the cytosol and nucleus (Figures 2c and 6c). However, when co‐expressed with OsNAP‐FLAG, the OsNAC24‐GFP protein was exclusively localized to the nucleus (Figure 6c). These results indicate that OsNAP facilitates the localization of OsNAC24 to the nucleus.

Nuclear translocation of OsNAC24 and co‐expression of OsNAC24 and OsNAP enhance OsGBSSI expression

Protein sequence analysis using cNLS Mapper identified a putative NLS peptide, VTGKRKRSSD, in the C terminus of the OsNAP protein. When this peptide was fused to OsNAC24‐GFP and transiently expressed in rice protoplasts, the fluorescent signal was observed only in the nuclei (Figure 6c), confirming that VTGKRKRSSD is a functional NLS domain. To determine the effect of nuclear translocation of OsNAC24 on the transcription of target genes such as OsGBSSI, we performed dual‐luciferase assays using the same GFP, OsNAC24‐GFP and OsNAC24‐GFP‐NLS constructs that were used in the subcellular localization experiments (Figure 6c,d). After co‐transfection of rice protoplasts with P OsGBSSI ::LUC, the relative luciferase activities of protoplasts expressing OsNAC24‐GFP and OsNAC24‐GFP‐NLS were 1.78‐ and 2.33‐fold higher, respectively, than in protoplasts expressing only GFP (Figure 6e), indicating that nuclear translocation of OsNAC24 enhances the expression of OsGBSSI. We further investigated the effect of co‐expressing OsNAC24 and OsNAP on OsGBSSI transcription. Dual‐luciferase assays showed that the relative luciferase activities of OsNAC24 and OsNAP were 3.67‐ and 2.58‐fold higher than in the control, respectively, while the relative luciferase activity was 36.28‐fold higher than in the control when OsNAC24 and OsNAP were co‐expressed in rice protoplasts (Figure 6f,g). These results indicate that the increase in OsGBSSI expression can be attributed to the nuclear translocation of OsNAC24 and the coactivation of OsGBSSI by the interaction of OsNAC24 and OsNAP, and the coactivation has a major effect on OsGBSSI expression.

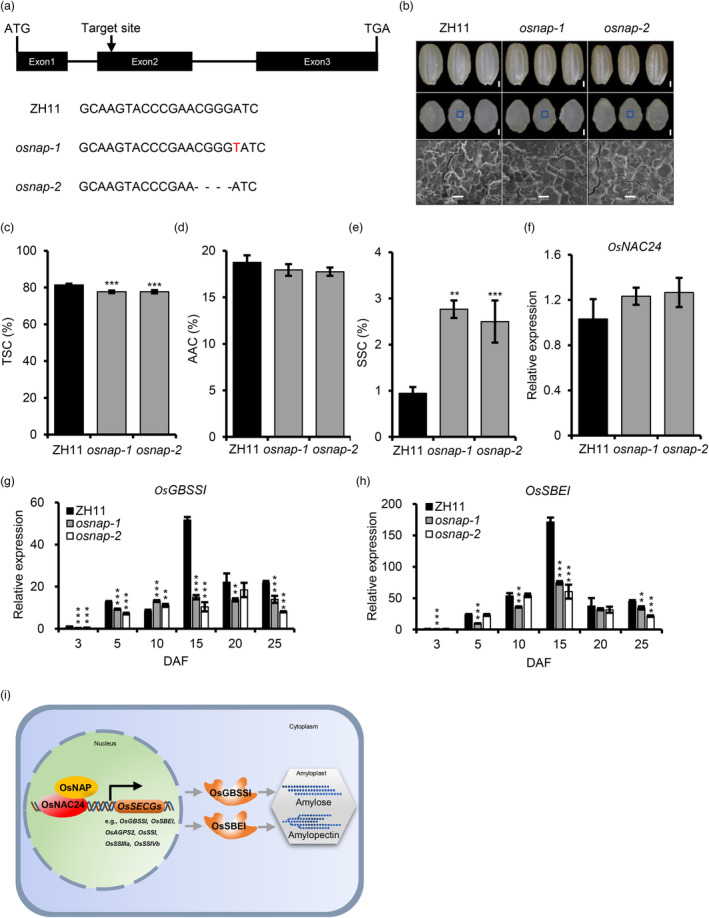

OsNAP regulates starch biosynthesis in developing rice endosperm

A dual‐luciferase assay indicated that OsNAP binds to the promoter of OsGBSSI and activates its transcription (Figure 6g). To assess the potential role of OsNAP in starch biosynthesis, we made a CRISPR/Cas9 construct expressing a sgRNA that targets the second exon of the OsNAP gene and transformed it into the japonica cultivar ‘Zhonghua11’ (ZH11). We identified two mutants, osnap‐1 and osnap‐2, that carried a 1 bp insertion and a 4 bp deletion in the target sequence, respectively. These mutations were predicted to generate truncated peptides in which 78 and 76 amino acids were identical to the OsNAP sequence, respectively (Figure 7a and Table S1). Similar to the osnac24 mutants, there were no obvious differences in endosperm appearance and starch granule morphology between the WT and osnap mutants (Figure 7b). Although the AAC was similar between WT and the osnap mutants, TSC was reduced and SSC was increased in the osnap mutants (Figure 7c–e), indicating that starch biosynthesis is altered in the mutants. qRT‐PCR assays showed that there were no changes in the transcript level of OsNAC24 in the osnap mutants, suggesting that OsNAP only affects the subcellular localization of OsNAC24 and has no effect on the expression of the OsNAC24 gene (Figure 7f). However, there were changes in the relative expression of all tested SECGs in the osnap mutants (Figure 7g,h and Figure S9), indicating that OsNAP indeed participates in the regulation of starch biosynthesis in rice endosperm. To further assess the function of OsNAC24 and OsNAP, four double mutants were generated by crossing the osnac24 and osnap single mutants. The grain appearance and starch granule morphology were unchanged in double mutants, while the TSC and AAC were lower than in the osnac24 single mutants except osnac24‐3 osnap‐1, and the SSC was increased in all the double mutants (Figure S10). Notably, the expression of OsGBSSI and OsSBEI was lower than in the osnac24 single mutants (Figure S11), confirming that they are targets of the OsNAC24‐OsNAP complex.

Figure 7.

OsNAP regulates starch biosynthesis in developing rice endosperm. (a) Construction of the osnap mutants by CRISPR/Cas9‐mediated genome editing. Upper panel, schematic diagram of the OsNAP gene. Black boxes and black lines represent the exons and introns, respectively. The position of the CRISPR/Cas9 target site in exon 2 is indicated by the arrow. Lower panel, alignment of the CRISPR/Cas9 target sequences from the WT and the osnap‐1 and osnap‐2 mutants. A 1‐bp insertion is indicated in red, and a 4‐bp deletion is indicated by dashes. (b) Brown rice grains (upper panel), cross sections of grains (middle panel) and starch granules (lower panel) from the WT and the osnap mutants. The blue boxes indicate the central area of the mature endosperms where the starch granules were examined by SEM. Scale bars = 1 mm (upper panels); 0.5 mm (upper panels); 10 μm (lower panels). (c‐e) Total starch content (TSC), apparent amylose content (AAC) and soluble sugar content (SSC), respectively, in endosperms of the WT and the osnap mutants. Data are mean ± SD of five replicates. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, Student's t‐test. (f) Relative expression of OsNAC24 in endosperms of the osnap mutants at 7 DAF. (g and h) Expression profiles of OsGBSSI and OsSBEI in developing endosperms of WT and the osnap mutants. Total RNA was extracted from endosperms at 3, 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 DAF. (f‐h) ACTIN was used as the internal control for expression normalization. Data are mean ± SD of four biological replicates. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, Student's t‐test. (i) Proposed model for the regulation of starch biosynthesis by the OsNAC24‐OsNAP complex. OsNAC24 binds directly to the promoters of six SECGs: OsGBSSI, OsSBEI, OsAGPS2, OsSSI, OsSSIIIa and OsSSIVb, and regulates amylose and amylopectin synthesis in developing rice endosperm mainly through OsGBSSI and OsSBEI. OsNAP interacts with OsNAC24 and coactivates the expression of target genes.

Discussion

In rice endosperm, multiple enzymes are coordinately involved in starch synthesis. In this study, we identified a NAC family protein, OsNAC24, which fine‐tunes starch synthesis mainly through OsGBSSI and OsSBEI. OsNAC24 directly targets the promoters of six SECGs and regulates their expression. We showed that OsNAP interacts with OsNAC24 and coactivates the expression of its target genes (Figure 7i).

OsNAC24 and OsNAP fine‐tune starch synthesis without affecting endosperm appearance

Changes in the functions or activities of starch‐synthesis enzymes and their regulators usually have severe effects on starch synthesis and generally result in defects in endosperm development. For example, endosperms from the osagpl2 mutants are severely shrivelled because the catalytic and allosteric regulatory properties of AGPase are significantly impaired (Tuncel et al., 2014). Disruption of the wx/osgbssI locus not only results in the total or nearly total absence of amylose but also produces opaque white grains (Terada et al., 2002). The transcription factors OsbZIP58, NF‐YB1 and OsMADS14 directly regulate the expression of SECGs in rice endosperm; however, loss‐of‐function of these TFs not only alters the content and physicochemical properties of starch but also affects the endosperm appearance (Bello et al., 2019; Feng et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2013).

In the osnac24 mutants, TSC and AAC were decreased (Figure 1b,c), the chain length distribution of amylopectin was altered (Figure 1e), and the ΔH values of the starch were increased (Table S2). Although the composition, structure and physicochemical properties of starch were changed, there were no changes in starch granule morphology and endosperm appearance in the osnac24 mutants (Figure 1a). In the osnap mutants, the TSC was decreased and SSC was increased, indicating that starch synthesis was disturbed (Figure 7c,e). However, the mature grains from the osnap mutants had semitransparent endosperm, which was indistinguishable from that of WT (Figure 7b). These results imply specific roles for OsNAC24 and OsNAP in fine‐tuning starch synthesis.

A previous study reported that osnac20/26 double mutants exhibit reduced grain size and weight with a floury endosperm phenotype and reduced starch accumulation (Wang et al., 2020). However, single mutations in either OsNAC20 or OsNAC26 do not affect endosperm appearance, which is similar to our finding that grains from both the osnac24 and osnap mutants have endosperms that appear normal. These findings reveal that NAC transcription factors play important roles in fine‐tuning starch synthesis in rice endosperm.

OsNAC24 targets a distinct subset of genes that encode starch‐synthesis enzymes

Based on the expression patterns in developing rice endosperm, 27 SECGs can be assigned to four groups (Ohdan et al., 2005). Group 1 genes are thought to function in the synthesis of glucan primers or initiation of starch granules. Genes in Groups 2 and 3 are thought to play major roles in endosperm starch synthesis, and Group 4 genes are thought to responsible for starch synthesis in the pericarp. In this study, we analysed the genes in Groups 2 and 3 and found that the expression of eight genes was altered in the osnac24 mutants (Figure 4a,b and Figure S3). ChIP‐PCR assays revealed that OsNAC24 binds to the promoters of six genes in vivo (Figure 5b,c and Figure S6a–d), indicating that OsNAC24 directly regulates the expression of OsGBSSI, OsSBEI, OsAGPS2b, OsSSI, OsSSIIIa and OsSSIVb, while it regulates OsAGPL2 and OsSSIIa expression indirectly.

Several TFs have been reported to directly regulate the expression of SECGs in rice endosperm, including OsBP5, OsbZIP58, NF‐YB1, OsNAC20, OsNAC26 and OsMADS14 (Bello et al., 2019; Feng et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2013, 2020; Zhu et al., 2003). Among them, OsBP5 and NF‐YB1 only target the promoter of OsGBSSI to regulate the synthesis of amylose (Bello et al., 2019; Zhu et al., 2003). Similar to OsNAC24, OsbZIP58 also regulates both amylose and amylopectin synthesis, but its target genes are OsAGPL3, OsGBSSI, OsSSIIa, OsSBEI, OsSBEIIb and OsISA2 (Wang et al., 2013). OsMADS14 binds to the promoters of OsAGPL2 and OsGBSSI (Feng et al., 2022). Both OsNAC20 and OsNAC26 alone can target the promoters of OsAGPS2b, OsAGPL2, OsSSI, OsSBEI and OsPUL (Wang et al., 2020). In this study, we also showed that OsNAP can promote the transcription of OsGBSSI in rice protoplasts (Figure 6g). Further identification of additional target genes of OsNAP in endosperm cells will help to elucidate the complexity and diversity of the mechanisms that regulate starch biosynthesis.

OsNAC24 regulates starch synthesis mainly through OsGBSSI and OsSBEI

In rice protoplasts, OsNAC24 activates the expression of OsGBSS1, OsSBEI, OsAGPS2 and OsSSIIIa (Figure 5e,f and Figure S6e,g). Moreover, the expression of these four genes was down‐regulated in osnac24 mutants (Figure 4a,b and Figure S3a,e). These results are consistent with the transcriptional activation activity of OsNAC24 (Figure 3b). However, although OsSSIVb expression was also down‐regulated in the osnac24 mutants (Figure S3f), OsNAC24 could not significantly activate the expression of this gene in protoplasts (Figure S6h). In addition, OsNAC24 activated the expression of OsSSI in protoplasts (Figure S6f), but OsSSI was up‐regulated in the osnac24 mutants (Figure S3c). The inconsistencies between the expression levels of OsSSI and OsSSIVb in the osnac24 mutants and the transactivation activities of OsNAC24 in rice protoplasts imply that more complex regulatory mechanisms may exist in plant cells, which deserves further study in the future.

Western blot analysis revealed that, among the analysed proteins, the protein contents of OsGBSSI and OsSBEI were decreased (Figure 4c). Therefore, although OsNAC24 directly targets the promoters of six genes, OsNAC24 regulates amylose and amylopectin synthesis mainly through OsGBSSI and OsSBEI. Except for OsGBSSI and OsSBEI, changes in the expression levels of other genes did not lead to a corresponding increase or decrease in their respective protein contents. The disconnect between changes in protein contents and gene expression levels may be attributed to both post‐transcriptional and post‐translational modifications. There are several pieces of evidence to show that the abundance of one protein can be affected by that of other enzymes. For example, the protein content of SBEIIb is decreased in starch granules in the maize su2 − mutant, which lacks a functional SSIIa protein (Grimaud et al., 2008).

OsNAC24 binds to two specific motifs as well as the core NAC‐binding motif

Previous studies identified the core NAC‐binding motif, CACG (Olsen et al., 2005a; Tran et al., 2004). In this study, sequence analysis revealed that there are multiple CACG motifs in the promoter regions of each of the OsNAC24 target genes (Figure 5b,c and Figure S6a–d). EMSAs showed that OsNAC24 binds to some CACG motifs in these genes with different strengths (Figure 5h and Figure S7), suggesting that the activation effect of OsNAC24 on the transcription of each target gene may be different.

Several studies have reported that NAC proteins can bind to specific motifs that differ from the core motif (Olsen et al., 2005a; Sakuraba et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2019). For example, four NAC proteins from maize and rice with high sequence similarity, ZmNAC128, ZmNAC130, OsNAC20 and OsNAC26, all bind to a common sequence, ACGCAA, to coordinate starch and protein synthesis (Wang et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2019). In the present study, EMSA showed that motif d, TTGACAA, in fragment 4 of the OsGBSS1 promoter and motif b, ASAAGA, in fragment 2 of the OsSBEI promoter, are preferentially bound by OsNAC24 (Figure 5h). These sequences do not contain CACG and its reverse complement CGTG and, at least to our knowledge, are specific for OsNAC24. The core and OsNAC24‐specific binding motifs provide diverse selectivity for OsNAC24 to regulate its target genes.

Since amylose content is the primary determinant of rice grain quality, especially in terms of eating and cooking quality, Waxy/OsGBSSI is the main target for rice quality improvement. In addition to identifying more natural Wx alleles, creating novel beneficial alleles using gene editing technology is an efficient strategy to fine‐tune amylose content (Huang et al., 2020a). For example, by editing the cis‐elements in the Wx b promoter, six new alleles with slightly reduced Wx expression were generated (Huang et al., 2020b). In addition to the predicted cis‐elements, only binding motifs for OsBP5, OsbZIP58, NF‐YB1 and OsMADS14 were identified in the Waxy/OsGBSSI gene promoter (Bello et al., 2019; Feng et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2003). The identification of OsNAC24‐binding motifs provides novel targets for the improvement of grain quality by fine‐tuning starch synthesis in rice grains.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

The japonica rice cultivar ‘Nipponbare’ was used in transformation experiments with all OsNAC24 genetic constructs. The japonica cultivar ‘Zhonghua11’ was used to generate the osnap mutants. To generate the osnac24 osnap double mutants, two osnac24 mutants, osnac24‐2 and osnac24‐3, were crossed with two osnap mutants, osnap‐1 and osnap‐2, respectively. The F1 plants were subsequently backcrossed to ‘Nipponbare’ three times to generate BC3F1 plants, and then four homozygous double mutants, osnac24‐2 osnap‐1, osnac24‐3 osnap‐1, osnac24‐2 osnap‐2 and osnac24‐3 osnap‐2, were selected from the BC3F2 progeny. Paddy field conditions: plants were grown at the experimental stations in Shanghai, China (121°24′ E, 31°00′ N) during the summer season, or at Lingshui, China (110°00′ E, 18°31′ N) during the winter season under natural conditions mainly for phenotype analysis, gene expression studies and seed production. Greenhouse conditions: plants were grown at 28 °C with an 11‐h light/13‐h dark photoperiod mainly for seedling cultivation and gene expression assays.

Plasmid construction and transformation

For the CRISPR/Cas9 constructs, four target sites, 5′‐GGCAAAGATGAGTCAGGTG‐3′, 5′‐TCGATACTCCGCCGGTATG‐3′, 5′‐TCCTTGCCTGTCTTGCCAA‐3′ and 5’‐CTCAGCGGCGTCAGGCTTT‐3′ were designed for OsNAC24, and one target site, 5′‐GCAAGTACCCGAACGGGATC‐3′, was designed for OsNAP. The sgRNA sequences were synthesized, and the CRISPR/Cas9 constructs were generated following a previously published protocol (Xie et al., 2017). For overexpression of OsNAC24, a DNA fragment that included 2 kb of sequence upstream of the start codon, the ORF, and 1 kb of sequence downstream of the stop codon was amplified from genomic DNA of ‘Nipponbare’ and cloned into the pCAMBIA1300 vector. For the promoter‐driven GUS reporter, 2 kb of genomic sequence upstream of the start codon was amplified from genomic DNA of ‘Nipponbare’ and cloned into the pCAMBIA1300‐GN vector. All of the recombinant plasmid vectors were introduced into Agrobacterium strain EHA105 and used to transform different rice cultivars. For the subcellular localization experiments, the CDSs of OsNAC24 and OsNAP were amplified from cDNA pools of 7 DAF endosperm, and the fragments were cloned into PA7‐GFP in frame with the GFP gene sequence. For the dual‐luciferase reporter assay, the CDS of OsNAC24 was cloned into pGreenII‐62SK driven by the CaMV 35S promoter, and the promoter regions of the target genes were cloned into pGreenII‐0800‐LUC upstream of the luciferase gene. For transient expression assays in protoplasts, the OsNAP CDS was cloned into PA7‐FLAG in frame with the FLAG epitope to construct OsNAP‐FLAG. For the BiFC assays, the CDSs of OsNAC24 and OsNAP were fused in frame with cYFP and nYFP, respectively. All the plasmids for transient expression assays were transformed into rice protoplast by the PEG‐mediated method as described previously (Zhang et al. 2011b). All primers used in this study are given in Table S4.

qRT‐PCR analysis

All rice tissues were either freshly collected or had been previously frozen in liquid nitrogen, and total RNA was extracted using the RNAprep Pure Plant Kit (Tiangen Biotech). One μg of total RNA was used as the template, and first‐strand cDNA was synthesized using the PrimeScript™ II 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (TaKaRa). 0.2 μg cDNA was used as the template in 20 μL reaction volumes, and the amplifications were performed using a CFX Connect Real‐Time PCR Detection System (Bio‐Rad). Rice UBIQUITIN10 (OsUBQ10) or ACTIN1 was used as the internal control for normalization of gene expression.

Immunoblot analysis

Total proteins from 7 DAF endosperm (three endosperms for each sample) were extracted as described previously (Liu et al., 2014) and quantified using the Bradford method. Equivalent amounts of total proteins (50 μg) from each sample were separated by denaturing SDS‐PAGE. Polyacrylamide gels containing the same samples were further used for both Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining and Western blot detection. The monoclonal antibody anti‐α‐Tubulin was produced by YEASEN Biotechnology Co., Ltd and was used at a dilution of 1:1000. Other polyclonal antibodies were produced against synthetic peptides by CoWin Biosciences. The sequences of the synthetic peptides are given in Table S5. The dilution ratios were as follows: antibodies against OsGBSSI, OsSSI, OsSBEI, OsSBEIIb and OsPho1 were used at 1:5000 dilutions, and antibodies against OsNAC24, OsAGPS2b, OsAGPL2, OsSSIIa, OsSSIIIa, OsSSIVb, OsISA1 and OsISA2 were used at a dilution of 1:1000.

Scanning electron microscopy

Mature rice seeds were dehulled and dried for 2 days at 37 °C. The endosperms were then cut down the middle with a knife, and the transverse sections were fixed and coated with gold. The starch grains in the transverse sections were observed under a scanning electron microscope (JSM‐6360LV; JEOL).

Determination of starch content and physicochemical properties

Mature seeds were dehulled and polished and then ground to fine powder and filtered with a sifter (150 mesh). The TAC was measured using the Total Starch Assay Kit (Megazyme). The AAC was measured using a previously described method (Liu et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2013). The concentration of soluble sugars was measured using the anthrone‐sulphuric acid colorimetry method (Wang et al., 2013). Determination of the amylopectin chain length distribution was performed as previously described (Zhang et al., 2016). The gelatinization temperature was measured using a previously described method (Zhu et al., 2010). Determination of gel consistency was performed as described in the National Standard of the People's Republic of China GB/T 22294–2008.

Yeast 1‐hybrid (Y1H) and yeast 2‐hybrid (Y2H) assays

For Y1H assays, the full‐length OsNAC24 CDS and various C‐terminal and N‐terminal deletions for truncated proteins were cloned into the pGBKT7 and pEG202 vectors, respectively, to make in‐frame protein fusions with the GAL4 BD and the LexA BD, respectively. Constructs in pGBKT7 were transformed into the yeast strain Y2HGold (Clontech), and the strains were grown on SD/−Trp + X‐α‐Gal culture medium (with or without AbA). Constructs in the pEG202 vector were transformed into yeast strain EGY48 and grown on SD/‐Ura‐His culture medium (with X‐Gal). For Y2H assays, the truncated OsNAC24 (ΔC6) was fused with GAL4 BD as bait, while the full‐length OsNAC24 and OsNAP coding sequences were fused with GAL4 AD as prey. The bait and prey vectors were then co‐transformed into Y2HGold and grown on SD/−Trp‐Leu or SD/−Trp‐Leu‐His‐Ade culture media. Yeast transformation was performed following the manufacturer's (Clontech) instructions.

ChIP assays

Fresh endosperms at 7 DAF to 9 DAF from OsNAC24‐overexpression plants were split into two pieces and immediately cross‐linked in formaldehyde solution (1%, m/V); a total of approximately 5 g of endosperm were prepared in this manner. The subsequent operations were performed as described previously (Gendrel et al., 2005). ChIP‐DNA libraries were constructed and sequenced by Shanghai Biotechnology Corporation. ChIP‐PCR was performed by primers flanking the binding motifs of the target promoters, and the promoter of ACTIN1 was used as the internal control.

Dual‐luciferase reporter assay

The CDSs of the OsNAC24 and OsNAP genes were cloned into expression vectors including pGreen‐62SK, PA7‐GFP and PA7‐FLAG driven by the CaMV 35S promoter. The promoter regions of the target genes were cloned into pGreen‐0800‐LUC just upstream of the LUC coding sequence. The plasmid constructs were co‐transformed as needed into rice protoplasts, and after overnight incubation, the protoplasts were collected and luciferase activity was measured using the Dual‐Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs)

OsNAC24 was fused with a His tag by cloning the OsNAC24 CDS into the pET‐32a vector (Novagen); the OsNAC24‐His fusion protein was expressed in the ROSETTA (D3) strain of E. coli and purified on a Ni‐NTA column (Qiagen). The DNA fragments that were enriched in the ChIP‐PCR assay were synthesized and labelled using the Biotin 3′ End DNA Labeling Kit (Thermo Fisher scientific). The purified proteins and labelled probes were used in EMSAs with the LightShift Chemiluminescent EMSA Kit (Thermo Fisher scientific). The probes selected for mutation assays were synthesized and labelled at the 5′ ends with Cy5 fluorochrome by BioSune. The end‐labelling and EMSA operations were performed according to the kit manufacturer's instructions.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFD1200103), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31971862, 31825019, 31771754), the Department of Science and Technology of Jiangsu Province (BE2022336, BM2022008‐02), the Guangdong Province Key Research and Development Program (2018B020202012), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2021M692723), and the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Author contributions

J.‐P. Gao and X.‐L. Cai conceived the project and designed the study. S.‐K. Jin, L.‐N. Xu, Y.‐J. Leng, M.‐Q. Zhang, Q.‐Q. Yang, S.‐L. Wang, S.‐W. Jia, T. Song, R.‐A. Wang and T. Tao performed experiments. S.‐K. Jin, Q.‐Q. Liu, X.‐L. Cai and J.‐P. Gao analysed and interpreted the data. S.‐K. Jin and J.‐P. Gao wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supporting information

Figure S1 Generation and identification of the osnac24 mutants in ‘Nipponbare’.

Figure S2 Amino acid sequence alignment of NAC TF family members in the Va (1)/NAP subfamily.

Figure S3 Expression profiles of starch‐synthesis enzyme‐encoding genes in developing endosperm in the WT ‘Nipponbare’ and the three osnac24 mutants.

Figure S4 Protein contents of starch‐synthesis enzymes in developing endosperms of the osnac24 mutants.

Figure S5 Generation and identification of OsNAC24‐overexpression (OE) plants.

Figure S6 ChIP‐PCR and dual‐luciferase assays of OsAGPS2, OsSSI, OsSSIIIa and OsSSIVb.

Figure S7 OsNAC24 directly binds to the promoters of the OsAGPS2, OsSSI, OsSSIIIa and OsSSIVb genes.

Figure S8 OsNAC24 binds to the g and d motifs in the OsGBSSI promoter.

Figure S9 Expression profiles of starch‐synthesis enzyme‐coding genes in developing endosperms of the WT ZH11 and the two osnap mutants.

Figure S10 Mutation of both OsNAC24 and OsNAP further reduces the total starch content and apparent amylose content in rice endosperm.

Figure S11 Expression profiles of genes encoding starch‐synthesis enzymes in developing endosperm of the wild‐type ‘Nipponbare’, the two osnac24 mutants and the four osnac24 osnap double mutants.

Table S1 Amino acid sequences of the OsNAC24 and OsNAP proteins in WT and mutant plants generated using CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing technology.

Table S2 Effects of the three osnac24 mutations on the gelatinization properties of starch.

Table S3 Starch‐synthesis enzyme‐encoding genes identified by ChIP‐seq.

Table S4 Names and sequences of oligonucleotide primers used in the four types of experiments described in this study.

Table S5 Amino acid sequences of synthetic peptides used as antigens for the preparation of polyclonal antibodies in this study.

Acknowledgements

We thank Yao‐Guang Liu (South China Agricultural University) for kindly providing the CRISPR/Cas9 vectors. We also thank Xiao‐Shu Gao, Xiao‐Yan Gao, Ji‐Qin Li and Zhi‐Ping Zhang (CAS Center for Excellence in Molecular Plant Sciences) for their assistance with confocal laser microscopy and scanning electron microscopy.

Contributor Information

Xiu‐Ling Cai, Email: xlcai@yzu.edu.cn.

Ji‐Ping Gao, Email: jpgao@yzu.edu.cn.

References

- Bahaji, A. , Li, J. , Sánchez‐López Á.M., Baroja‐Fernández, E. , Muñoz, F.J. , Ovecka, M. , Almagro, G. , Montero, M. , Ezquer, I. , Etxeberria, E. , et al. (2014). Starch biosynthesis, its regulation and biotechnological approaches to improve crop yields. Biotechnol. Adv. 32:87–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballicora, M.A. , Iglesias, A.A. and Preiss, J. (2004) ADP‐glucose pyrophosphorylase: A regulatory enzyme for plant starch synthesis. Photosynth. Res. 79, 1–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bello, B.K. , Hou, Y. , Zhao, J. , Jiao, G. , Wu, Y. , Li, Z. , Wang, Y. et al. (2019) NF‐YB1‐YC12‐bHLH144 complex directly activates Wx to regulate grain quality in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Biotechnol. J. 17, 1222–1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crofts, N. , Sugimoto, K. , Oitome, N.F. , Nakamura, Y. and Fujita, N. (2017) Differences in specificity and compensatory functions among three major starch synthases determine the structure of amylopectin in rice endosperm. Plant Mol. Biol. 94, 399–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinges, J.R. , Colleoni, C. , James, M.G. and Myers, A.M. (2003) Mutational analysis of the pullulanase‐type debranching enzyme of maize indicates multiple functions in starch metabolism. Plant Cell 15, 666–680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng, T. , Wang, L. , Li, L. , Liu, Y. , Chong, K. , Theißen, G. and Meng, Z. (2022) OsMADS14 and NF‐YB1 cooperate in the direct activation of OsAGPL2 and Waxy during starch synthesis in rice endosperm. New Phytol. 234, 77–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu, F.F. and Xue, H.W. (2010) Coexpression analysis identifies Rice Starch Regulator1, a rice AP2/EREBP family transcription factor, as a novel rice starch biosynthesis regulator. Plant Physiol. 154, 927–938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita, N. , Kubo, A. , Francisco, P.B., Jr. , Nakakita, M. , Harada, K. , Minaka, N. and Nakamura, Y. (1999) Purification, characterization, and cDNA structure of isoamylase from developing endosperm of rice. Planta 208, 283–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita, N. , Kubo, A. , Suh, D.S. , Wong, K.S. , Jane, J.L. , Ozawa, K. , Takaiwa, F. et al. (2003) Antisense inhibition of isoamylase alters the structure of amylopectin and the physicochemical properties of starch in rice endosperm. Plant Cell Physiol. 44, 607–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita, N. , Yoshida, M. , Kondo, T. , Saito, K. , Utsumi, Y. , Tokunaga, T. , Nishi, A. et al. (2007) Characterization of SSIIIa‐deficient mutants of rice: the function of SSIIIa and pleiotropic effects by SSIIIa deficiency in the rice endosperm. Plant Physiol. 144, 2009–2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita, N. , Toyosawa, Y. , Utsumi, Y. , Higuchi, T. , Hanashiro, I. , Ikegami, A. , Akuzawa, S. et al. (2009) Characterization of pullulanase (PUL)‐deficient mutants of rice (Oryza sativa L.) and the function of PUL on starch biosynthesis in the developing rice endosperm. J. Exp. Bot. 60, 1009–1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y. , An, K. , Guo, W. , Chen, Y. , Zhang, R. , Zhang, X. , Chang, S. et al. (2021) The endosperm‐specific transcription factor TaNAC019 regulates glutenin and starch accumulation and its elite allele improves wheat grain quality. Plant Cell 33, 603–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendrel, A.V. , Lippman, Z. , Martienssen, R. and Colot, V. (2005) Profiling histone modification patterns in plants using genomic tiling microarrays. Nat. Methods 2, 213–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimaud, F. , Rogniaux, H. , James, M.G. , Myers, A.M. and Planchot, V. (2008) Proteome and phosphoproteome analysis of starch granule‐associated proteins from normal maize and mutants affected in starch biosynthesis. J. Exp. Bot. 59, 3395–3406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan, H. , Li, P. , Imparl‐Radosevich, J. , Preiss, J. and Keeling, P. (1997) Comparing the properties of Escherichia coli branching enzyme and maize branching enzyme. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 342, 92–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han, Y. , Sun, F.J. , Rosales‐Mendoza, S. and Korban, S.S. (2007) Three orthologs in rice, Arabidopsis, and Populus encoding starch branching enzymes (SBEs) are different from other SBE gene families in plants. Gene 401, 123–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L. , Sreenivasulu, N. and Liu, Q. (2020a) Waxy editing: Old meets new. Trends Plant Sci. 25, 963–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L. , Li, Q. , Zhang, C. , Chu, R. , Gu, Z. , Tan, H. , Zhao, D. et al. (2020b) Creating novel Wx alleles with fine‐tuned amylose levels and improved grain quality in rice by promoter editing using CRISPR/Cas9 system. Plant Biotechnol. J. 18, 2164–2166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L. , Tan, H. , Zhang, C. , Li, Q. and Liu, Q. (2021) Starch biosynthesis in cereal endosperms: An updated review over the last decade. Plant Commun. 2, 100237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irshad, A. , Guo, H. , Rehman, S.U. , Wang, X. , Wang, C. , Raza, A. , Zhou, C. et al. (2021) Soluble starch synthase enzymes in cereals: An updated review. Agronomy 11, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- James, M.G. , Denyer, K. and Myers, A.M. (2003) Starch synthesis in the cereal endosperm. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 6, 215–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon, J.S. , Ryoo, N. , Hahn, T.R. , Walia, H. and Nakamura, Y. (2010) Starch biosynthesis in cereal endosperm. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 48, 383–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeling, P.L. and Myers, A.M. (2010) Biochemistry and genetics of starch synthesis. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 1, 271–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.J. , Nam, H.G. and Lim, P.O. (2016) Regulatory network of NAC transcription factors in leaf senescence. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 33, 48–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y. , Choi, M.S. , Lee, G. , Jang, S. , Yoon, M.R. , Kim, B. , Piao, R. et al. (2017) Sugary endosperm is modulated by starch branching enzyme IIa in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Rice (N Y) 10, 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.F. , Zhang, G.Y. , Dong, Z.W. , Yu, H.X. , Gu, M.H. , Sun, S.S. and Liu, Q.Q. (2009) Characterization of expression of the OsPUL gene encoding a pullulanase‐type debranching enzyme during seed development and germination in rice. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 47, 351–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, H. , Prakash, S. , Nicholson, T.M. , Fitzgerald, M.A. and Gilbert, R.G. (2016) The importance of amylose and amylopectin fine structure for textural properties of cooked rice grains. Food Chem. 196, 702–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang, C. , Wang, Y. , Zhu, Y. , Tang, J. , Hu, B. , Liu, L. , Ou, S. et al. (2014) OsNAP connects abscisic acid and leaf senescence by fine‐tuning abscisic acid biosynthesis and directly targeting senescence‐associated genes in rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 111, 10013–10018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D. , Wang, W. and Cai, X. (2014) Modulation of amylose content by structure‐based modification of OsGBSS1 activity in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Biotechnol. J. 12, 1297–1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, Y. (2002) Towards a better understanding of the metabolic system for amylopectin biosynthesis in plants: rice endosperm as a model tissue. Plant Cell Physiol. 43, 718–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, Y. , Umemoto, T. , Ogata, N. , Kuboki, Y. , Yano, M. and Sasaki, T. (1996) Starch debranching enzyme (R‐enzyme or pullulanase) from developing rice endosperm: purification, cDNA and chromosomal localization of the gene. Planta 199, 209–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuruzzaman, M. , Manimekalai, R. , Sharoni, A.M. , Satoh, K. , Kondoh, H. , Ooka, H. and Kikuchi, S. (2010) Genome‐wide analysis of NAC transcription factor family in rice. Gene 465, 30–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuruzzaman, M. , Sharoni, A.M. and Kikuchi, S. (2013) Roles of NAC transcription factors in the regulation of biotic and abiotic stress responses in plants. Front. Microbiol. 4, 248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohdan, T. , Francisco, P.B., Jr. , Sawada, T. , Hirose, T. , Terao, T. , Satoh, H. and Nakamura, Y. (2005) Expression profiling of genes involved in starch synthesis in sink and source organs of rice. J. Exp. Bot. 56, 3229–3244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, A.N. , Ernst, H.A. , Leggio, L.L. and Skriver, K. (2005a) DNA‐binding specificity and molecular functions of NAC transcription factors. Plant Sci. 169, 785–797. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, A.N. , Ernst, H.A. , Leggio, L.L. and Skriver, K. (2005b) NAC transcription factors: structurally distinct, functionally diverse. Trends Plant Sci. 10, 79–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakuraba, Y. , Kim, Y.S. , Han, S.H. , Lee, B.D. and Paek, N.C. (2015) The arabidopsis transcription factor NAC016 promotes drought stress responses by repressing AREB1 transcription through a trifurcate feed‐forward regulatory loop involving NAP. Plant Cell 27, 1771–1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sano, Y. (1984) Differential regulation of waxy gene expression in rice endosperm. Theor. Appl. Genet. 68, 467–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh, H. , Nishi, A. , Yamashita, K. , Takemoto, Y. , Tanaka, Y. , Hosaka, Y. , Sakurai, A. et al. (2003) Starch‐branching enzyme I‐deficient mutation specifically affects the structure and properties of starch in rice endosperm. Plant Physiol. 133, 1111–1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh, H. , Shibahara, K. , Tokunaga, T. , Nishi, A. , Tasaki, M. , Hwang, S.K. , Okita, T.W. et al. (2008) Mutation of the plastidial alpha‐glucan phosphorylase gene in rice affects the synthesis and structure of starch in the endosperm. Plant Cell 20, 1833–1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- She, K.C. , Kusano, H. , Koizumi, K. , Yamakawa, H. , Hakata, M. , Imamura, T. , Fukuda, M. et al. (2010) A novel factor FLOURY ENDOSPERM2 is involved in regulation of rice grain size and starch quality. Plant Cell 22, 3280–3294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, N. , Fujita, N. , Nishi, A. , Satoh, H. , Hosaka, Y. , Ugaki, M. , Kawasaki, S. et al. (2004) The structure of starch can be manipulated by changing the expression levels of starch branching enzyme IIb in rice endosperm. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2, 507–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terada, R. , Urawa, H. , Inagaki, Y. , Tsugane, K. and Iida, S. (2002) Efficient gene targeting by homologous recombination in rice. Nat. Biotechnol. 20, 1030–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Z. , Qian, Q. , Liu, Q. , Yan, M. , Liu, X. , Yan, C. , Liu, G. et al. (2009) Allelic diversities in rice starch biosynthesis lead to a diverse array of rice eating and cooking qualities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106, 21760–21765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran, L.S. , Nakashima, K. , Sakuma, Y. , Simpson, S.D. , Fujita, Y. , Maruyama, K. , Fujita, M. et al. (2004) Isolation and functional analysis of Arabidopsis stress‐inducible NAC transcription factors that bind to a drought‐responsive cis‐element in the early responsive to dehydration stress 1 promoter. Plant Cell 16, 2481–2498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuncel, A. , Kawaguchi, J. , Ihara, Y. , Matsusaka, H. , Nishi, A. , Nakamura, T. , Kuhara, S. et al. (2014) The rice endosperm ADP‐glucose pyrophosphorylase large subunit is essential for optimal catalysis and allosteric regulation of the heterotetrameric enzyme. Plant Cell Physiol. 55, 1169–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.Y. , Wu, Z.L. , Xing, Y.Y. , Zheng, F.G. , Guo, X.L. , Zhang, W.G. and Hong, M.M. (1990) Nucleotide sequence of rice waxy gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 18, 5898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.C. , Xu, H. , Zhu, Y. , Liu, Q.Q. and Cai, X.L. (2013) OsbZIP58, a basic leucine zipper transcription factor, regulates starch biosynthesis in rice endosperm. J. Exp. Bot. 64, 3453–3466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J. , Chen, Z. , Zhang, Q. , Meng, S. and Wei, C. (2020) The NAC transcription factors OsNAC20 and OsNAC26 regulate starch and storage protein synthesis. Plant Physiol. 184, 1775–1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie, X. , Ma, X. , Zhu, Q. , Zeng, D. , Li, G. and Liu, Y.G. (2017) CRISPR‐GE: A convenient software toolkit for CRISPR‐based genome editing. Mol. Plant 10, 1246–1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeeman, S.C. , Kossmann, J. and Smith, A.M. (2010) Starch: its metabolism, evolution, and biotechnological modification in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 61, 209–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G. , Cheng, Z. , Zhang, X. , Guo, X. , Su, N. , Jiang, L. , Mao, L. et al. (2011a) Double repression of soluble starch synthase genes SSIIa and SSIIIa in rice (Oryza sativa L.) uncovers interactive effects on the physicochemical properties of starch. Genome 54, 448–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. , Su, J. , Duan, S. , Ao, Y. , Dai, J. , Liu, J. , Wang, P. et al. (2011b) A highly efficient rice green tissue protoplast system for transient gene expression and studying light/chloroplast‐related processes. Plant Methods 7, 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C. , Zhou, L. , Zhu, Z. , Lu, H. , Zhou, X. , Qian, Y. , Li, Q. et al. (2016) Characterization of grain quality and starch fine structure of two Japonica rice (Oryza Sativa) cultivars with good sensory properties at different temperatures during the filling stage. J. Agric. Food Chem. 64, 4048–4057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z. , Dong, J. , Ji, C. , Wu, Y. and Messing, J. (2019) NAC‐type transcription factors regulate accumulation of starch and protein in maize seeds. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 116, 11223–11228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y. , Huang, W. , Liu, L. , Chen, T. , Zhou, F. and Lin, Y. (2013) Identification and functional characterization of a rice NAC gene involved in the regulation of leaf senescence. BMC Plant Biol. 13, 132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H. , Wang, L. , Liu, G. , Meng, X. , Jing, Y. , Shu, X. , Kong, X. et al. (2016) Critical roles of soluble starch synthase SSIIIa and granule‐bound starch synthase Waxy in synthesizing resistant starch in rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 113, 12844–12849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y. , Cai, X.L. , Wang, Z.Y. and Hong, M.M. (2003) An interaction between a MYC protein and an EREBP protein is involved in transcriptional regulation of the rice Wx gene. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 47803–47811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, L.J. , Liu, Q.Q. , Sang, Y. , Gu, M.H. and Shi, Y.C. (2010) Underlying reasons for waxy rice flours having different pasting properties. Food Chem. 120, 94–100. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 Generation and identification of the osnac24 mutants in ‘Nipponbare’.

Figure S2 Amino acid sequence alignment of NAC TF family members in the Va (1)/NAP subfamily.

Figure S3 Expression profiles of starch‐synthesis enzyme‐encoding genes in developing endosperm in the WT ‘Nipponbare’ and the three osnac24 mutants.

Figure S4 Protein contents of starch‐synthesis enzymes in developing endosperms of the osnac24 mutants.

Figure S5 Generation and identification of OsNAC24‐overexpression (OE) plants.

Figure S6 ChIP‐PCR and dual‐luciferase assays of OsAGPS2, OsSSI, OsSSIIIa and OsSSIVb.

Figure S7 OsNAC24 directly binds to the promoters of the OsAGPS2, OsSSI, OsSSIIIa and OsSSIVb genes.

Figure S8 OsNAC24 binds to the g and d motifs in the OsGBSSI promoter.