Abstract

The in vitro inhibitory effects of sitafloxacin (DU-6859a) and its three stereoisomers on bacterial DNA gyrase from Escherichia coli, topoisomerase IV from Staphylococcus aureus, and topoisomerase II from human placenta were compared. No correlation was observed between the inhibitory activities of quinolones against bacterial type II topoisomerases and those against human topoisomerase II. Sitafloxacin showed the most potent inhibitory activities against bacterial type II topoisomerases and the lowest activity against human type II topoisomerase.

Quinolone antibacterial agents have been used in therapy for various bacterial infections. The enzymic targets of quinolones are considered to be DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV (6, 7), which are essential enzymes responsible for controlling the topological state of DNA in DNA replication and transcription (16). DNA gyrase has ATP-dependent DNA supercoiling activity (8) and is a primary target of quinolones in the gram-negative species, such as Escherichia coli and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (3, 9, 15). In contrast, topoisomerase IV has an essential role in partitioning replicated chromosomes (13) and is more sensitive than DNA gyrase to some quinolones, such as levofloxacin and ciprofloxacin, in the gram-positive species, such as Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pneumoniae (5, 19, 22, 30).

Certain quinolones have been shown to interfere with the activity of eukaryotic type II topoisomerase (topoisomerase II) (23, 24), and their inhibitory potencies against topoisomerase II might be correlated with their cytotoxicities (11). Actually, Akahane et al. (1) reported that quinolones inhibited the proliferation of murine cells in a dose-dependent manner, and the cytotoxicities of quinolones correlated well with their inhibitory potencies against topoisomerase II. Therefore, it is justified to compare the inhibition by quinolones of the activity of DNA gyrase or topoisomerase IV with their inhibition of topoisomerase II activity. Our previous study demonstrated that levofloxacin, the l-isomer of ofloxacin, possessed a higher selectivity than ofloxacin and its d-isomer (11).

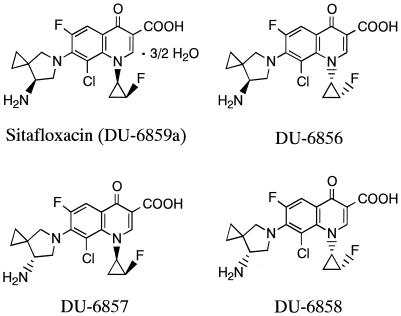

Sitafloxacin (also known as DU-6859a) {(−)-7-[(7S)-amino- 5-azaspiro(2,4)heptan-5-yl]-8-chloro-6-fluoro-1-[(1R,2S)-cis-2- fluoro-1-cyclopropyl]-1,4-dihydro-4-oxo-3-quinolinecarboxylic acid sesquihydrate}, a newly developed quinolone antibacterial agent, had more potent activity against a wide spectrum of bacteria (20, 25, 29) than levofloxacin and ciprofloxacin. Our previous studies demonstrated that DNA gyrase in E. coli is a primary target of sitafloxacin and that sitafloxacin recognizes topoisomerase IV preferentially over DNA gyrase in S. aureus (10, 30). In this study we focused on the inhibitory activities of sitafloxacin and its optical isomers DU-6856 {(−)-7-[(7S)-ami- no-5-azaspiro(2,4)heptan-5-yl]-8-chloro-6-fluoro-1-[(1S,2R)- cis-2-fluoro-1-cyclopropyl]-1,4-dihydro-4-oxoquinoline-3- carboxylic acid}, DU-6857 {(−)-7-[(7R)-amino-5-azaspiro(2,4) heptan-5-yl]-8-chloro-6-fluoro-1-[(1R,2S)-cis-2-fluoro-1- cyclopropyl]-1,4-dihydro-4-oxoquinoline-3-carboxylic acid}, and DU-6858 {(−)-7-[(7R)-amino-5-azaspiro(2,4)heptan-5-yl]-8-chloro-6-fluoro-1-[(1S,2R)-cis-2-fluoro-1-cyclopropyl]-1,4- dihydro-4-oxoquinoline-3-carboxylic acid} (14) against DNA gyrase from E. coli, topoisomerase IV from S. aureus, and topoisomerase II from human placenta.

The structures of sitafloxacin and its isomers are shown in Fig. 1. The quinolones tested in this study were synthesized at Daiichi Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan. Other chemicals were purchased from their respective manufacturers. The bacterial strains used in this study were reference strains and clinical isolates from several hospitals and laboratories in Japan. The MICs were determined by the microbroth dilution method recommended by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (21). The inoculum size was approximately 105 CFU/ml. The MIC was defined as the lowest drug concentration that prevented visible bacterial growth of the inoculum after incubation for 18 h at 37°C.

FIG. 1.

Structures of sitafloxacin and its stereoisomers.

The in vitro activities of sitafloxacin, its optical isomers (DU-6856, DU-6857, and DU-6858), levofloxacin, ofloxacin, and ciprofloxacin against a variety of reference strains and clinical isolates are given in Table 1. Among the quinolones tested, sitafloxacin had the greatest activity against members of the family Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, S. aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Streptococcus pyogenes, S. pneumoniae, and Haemophilus influenzae.

TABLE 1.

Antimicrobial activities of quinolonesa

| Organism | MIC (μg/ml)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STFX | DU-6856 | DU-6857 | DU-6858 | LVFX | OFLX | CPFX | |

| E. coli KL-16 | 0.008 | 0.016 | 0.031 | 0.063 | 0.031 | 0.063 | 0.008 |

| Citrobacter freundii IID 976 | 0.008 | 0.016 | 0.031 | 0.063 | 0.031 | 0.031 | ≦0.004 |

| Proteus vulgaris 08601 | ≦0.004 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.031 | 0.016 | 0.031 | 0.008 |

| Proteus mirabilis 08103 | 0.008 | 0.016 | 0.031 | 0.063 | 0.031 | 0.063 | 0.013 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae type 1 | 0.031 | 0.031 | 0.063 | 0.125 | 0.063 | 0.125 | 0.031 |

| Enterobacter cloacae 03400 | ≦0.004 | 0.008 | 0.031 | 0.063 | 0.031 | 0.031 | 0.016 |

| Serratia marcescens 10100 | 0.031 | 0.063 | 0.063 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.063 |

| P. aeruginosa PAO1 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.125 |

| Bacterium anitratum ATCC 19606 | 0.063 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 |

| H. influenzae 033803 960614 | 0.004 | 0.008 | 0.031 | 0.031 | 0.031 | 0.063 | 0.031 |

| S. aureus FDA 209-P | 0.008 | 0.016 | 0.063 | 0.063 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.25 |

| S. epidermidis 56500 | 0.063 | 0.063 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 |

| S. pyogenes G-36 | 0.063 | 0.125 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 2 | >2 | 2 |

| Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 19433 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 1 | 1 | 2 | >2 | 2 |

| S. pneumoniae J24 | 0.031 | 0.063 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

STFX, sitafloxacin; LVFX, levofloxacin; OFLX, ofloxacin; CPFX, ciprofloxacin.

Subunits A and B of DNA gyrase were purified separately from E. coli KL-16 by using novobiocin-epoxy-activated Sepharose 4B (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) column chromatography, as described previously (12). The specific activities of purified subunits A and B of DNA gyrase were 104 U/mg of protein. Subunits A and B of S. aureus topoisomerase IV were purified as fusion proteins separately with maltose-binding protein by the method described previously (30). Human topoisomerase II was purchased from TopoGEN, Inc. (Columbus, Ohio). Inhibitory activities of quinolones against type II topoisomerases were assayed electrophoretically as described previously (12, 30) with minor modifications. The gel was stained with ethidium bromide and photographed by using a UV light (302 nm) with a Gel Print 2000i/VGA (Bio Image Co., Ann Arbor, Mich.), and the brightness of bands was traced with an Image Analyzer (Bio Image). For the supercoiling assay of DNA gyrase, the reaction mixture (20 μl), containing subunits A and B (1 U of each, which brought 50% of the pBR322 plasmid to the supercoiled form), drug solution, 20 mM Tris hydrochloride (pH 7.5), 20 mM KCl, 4 mM MgCl2, 1 mM spermidine hydrochloride, 1 mM ATP, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 20 μg of bovine serum albumin per ml, and 0.2 μg of relaxed pBR322 plasmid DNA, was incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Each band was quantified, and the amount of supercoiled plasmid DNA treated with each concentration of quinolone was measured to determine the 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) against DNA gyrase. The IC50s against topoisomerase IV were determined as the drug concentrations that reduced the decatenation activity seen with drug-free controls by 50%. Additionally, for the relaxing assay of topoisomerase II, a reaction mixture (20 μl) containing 1 U of topoisomerase II (which brought 50% of the pBR322 plasmid to the relaxed form), 50 mM Tris hydrochloride (pH 7.5), 100 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ATP, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 0.5 mM EDTA, 30 μg of bovine serum albumin per ml, and 0.2 μg of supercoiled pBR322 was incubated at 37°C for 1 h. The IC50 of each quinolone against the relaxing activity of topoisomerase II was calculated by the same method as that for DNA gyrase.

MICs and inhibitory effects on topoisomerases are shown in Table 2. Sitafloxacin was twice as active against E. coli KL-16 as DU-6856, four times more active than DU-6857, and eight times more active than DU-6858. Against the supercoiling activity of E. coli DNA gyrase, the IC50s of sitafloxacin, DU-6856, DU-6857, and DU-6858 were 0.13, 0.18, 0.42, and 0.69 μg/ml, respectively. Thus, the anti-DNA gyrase activity of sitafloxacin was highest, followed by those of DU-6856, DU-6857, and DU-6858, in that order. There is a high correlation between the inhibitory effects of the quinolones on bacterial growth and the inhibition of DNA gyrase; the correlation coefficient, calculated by using a transformation of the data points of all the compounds tested, was 0.941.

TABLE 2.

Inhibitory effects of quinolones against type II topoisomerases

| Compound | IC50 ± SD (MIC) fora:

|

Selectivity

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gyr | Topo IV | Topo II | Topo II/Gyr | Topo II/Topo IV | |

| Sitafloxacin | 0.13 ± 0.01 (0.008) | 0.39 ± 0.15 (0.008) | 2,369 ± 101 | 18,221 | 6,022 |

| DU-6856 | 0.18 ± 0.02 (0.016) | 0.86 ± 0.22 (0.016) | 1,854 ± 20 | 10,298 | 2,164 |

| DU-6857 | 0.42 ± 0.01 (0.031) | 1.44 ± 0.07 (0.063) | 1,939 ± 147 | 4,616 | 1,346 |

| DU-6858 | 0.69 ± 0.10 (0.063) | 1.21 ± 0.06 (0.063) | 1,147 ± 80 | 1,663 | 951 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.39 ± 0.00 (0.031) | 2.36 ± 0.41 (0.25) | 1,854 ± 35 | 4,754 | 786 |

| Ofloxacin | 0.71 ± 0.07 (0.063) | 4.17 ± 1.25 (0.5) | 2,221 ± 48 | 3,129 | 532 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.32 ± 0.02 (0.008) | 2.83 ± 1.14 (0.25) | 325 ± 44 | 1,016 | 115 |

IC50s and MICs are expressed as micrograms per milliliter. Gyr, DNA gyrase from E. coli KL-16; Topo IV, topoisomerase IV from S. aureus FDA 209-P; Topo II, topoisomerase II from human placenta.

Against S. aureus FDA 209-P, sitafloxacin was twice as active as DU-6856 and eight times more active than DU-6857 and DU-6858. Against the decatenation activity of topoisomerase IV, the inhibitory activity of sitafloxacin was about twice as potent as that of DU-6856. DU-6857 and DU-6858 were about three times less active than sitafloxacin. There was also a significant correlation between the inhibitory effects on S. aureus growth and the inhibition of topoisomerase IV (correlation coefficient, 0.986).

On the other hand, the IC50s of four isomers against topoisomerase II from human placenta ranged from 1,147 to 2,369 μg/ml, and the inhibitory potency was lowest for sitafloxacin, followed by DU-6857, DU-6856, and DU-6858 in increasing order of potency. There was no correlation between the IC50 for any bacterial topoisomerase and that for mammalian topoisomerase II.

Eukaryotic topoisomerase II is known as an essential enzyme for cell growth (4). Because of the similarities in the biochemical mechanisms and amino acid sequences between DNA gyrase and mammalian topoisomerase II (17), the inhibition of human topoisomerase II by quinolones would be an undesirable side effect of antibacterial chemotherapy, and information on the relative selectivity toward bacterial target enzyme versus human topoisomerase II would be of significance. Fortunately, the compounds tested required higher concentrations to inhibit human topoisomerase II than to inhibit DNA gyrase or topoisomerase IV, and all the selectivity values of the compounds tested were greater than 100 (Table 2). Sitafloxacin proved to possess the highest relative selectivity for bacterial target enzyme versus human topoisomerase II among the compounds tested in this study.

It has been proposed that quinolones bind to a specific site on DNA in the DNA-enzyme complex (26–28). According to this model, differences in enzyme inhibitory potency are mainly determined by the strength of drug binding to a DNA receptor site on the enzyme-substrate complex, while the interaction of the C-7 substituent with the enzyme plays a supporting role (18). Yoshida et al. (31) have provided evidence showing that C-7 is in close contact with the so-called quinolone pocket in GyrB. Against DNA gyrase or topoisomerase IV, sitafloxacin and its C-7-7′(S)-isomer DU-6856 were more active than its C-7-7′(R)-isomers DU-6857 and DU-6858. These results suggested that C-7-7′(S)-isomers were more potent in the interaction between the C-7 substituent and the enzyme, compared to C-7-7′(R)-isomers. In the stereoisomeric derivatives of the N-1 substituent, cis-isomers were more potent than trans-isomers, as previously reported (2). In this study, sitafloxacin {C-1-([1R,2S]-cis-2-fluorocyclopropyl)} showed more-potent antibacterial activities against the bacterial enzymes, DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV, than its C-1-([1S,2R]-cis-2-fluorocyclopropyl) isomer DU-6856. This result suggested that the C-1-([1R,2S]-cis-2-fluorocyclopropyl) moiety has interactive potential with the receptor site on the DNA-enzyme complex. We plan to pursue further study of the difference in the ratios of binding of the isomers to DNA-topoisomerase II complex.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akahane K, Hoshino K, Sato K, Kimura Y, Une T, Osada Y. Inhibitory effects of quinolones on murine hematopoietic progenitor cells and eukaryotic topoisomerase II. Chemotherapy (Tokyo) 1991;37:224–226. doi: 10.1159/000238858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atarashi S, Imamura M, Kimura Y, Yoshida A, Hayakawa I. Fluorocyclopropyl quinolones. 1. Synthesis and structure-activity relationships of 1-(2-fluorocyclopropyl)-3-pyridonecarboxylic acid antibacterial agents. J Med Chem. 1993;36:3444–3448. doi: 10.1021/jm00074a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belland R J, Morrison S G, Ison C, Huang W M. Neisseria gonorrhoeae acquires mutations in analogous regions of gyrA and parC in fluoroquinolone-resistant isolates. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:371–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drlica K. Biology of bacterial deoxyribonucleic acid topoisomerases. Microbiol Rev. 1984;48:273–289. doi: 10.1128/mr.48.4.273-289.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferrero L, Cameron B, Crouzet J. Analysis of gyrA and grlA mutations in stepwise-selected ciprofloxacin-resistant mutants of Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1554–1558. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.7.1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferrero L, Cameron B, Manse B, Lagneaux D, Crouzet J, Famechon A, Blanche F. Cloning and primary structure of Staphylococcus aureus DNA topoisomerase IV: a primary target of fluoroquinolones. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:641–653. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gellert M. DNA topoisomerases. Annu Rev Biochem. 1981;50:879–910. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.50.070181.004311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gellert M, Mizuuchi K, O’Dea M H, Nash H A. DNA gyrase: an enzyme that introduces superhelical turns into DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1976;73:3872–3876. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.11.3872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heisig P. Genetic evidence for a role of parC mutations in development of high-level fluoroquinolone resistance in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:879–885. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.4.879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoshino K, Kitamura A, Morrissey I, Sato K, Kato J, Ikeda H. Comparison of inhibition of Escherichia coli topoisomerase IV by quinolones with DNA gyrase inhibition. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:2623–2627. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.11.2623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoshino K, Sato K, Akahane K, Yoshida A, Hayakawa I, Sato M, Une T, Osada Y. Significance of the methyl group on the oxazine ring of ofloxacin derivatives in the inhibition of bacterial and mammalian type II topoisomerases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:309–312. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.2.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoshino K, Sato K, Une T, Osada Y. Inhibitory effects of quinolones on DNA gyrase of Escherichia coli and topoisomerase II of fetal calf thymus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33:1816–1818. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.10.1816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kato J, Nishimura Y, Imamura R, Niki H, Hiraga S, Suzuki H. New topoisomerase essential for chromosome segregation in E. coli. Cell. 1990;63:393–404. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90172-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kimura Y, Atarashi S, Kawakami K, Sato K, Hayakawa I. (Fluorocyclopropyl)quinolones. 2. Synthesis and stereochemical structure-activity relationships of chiral 7-(7-amino-5-azaspiro[2,4]heptan-5-yl)-1-(2-fluorocyclopropyl)quinol one antibacterial agents. J Med Chem. 1994;37:3344–3352. doi: 10.1021/jm00046a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumagai Y, Kato J, Hoshino K, Akasaka T, Sato K, Ikeda H. Quinolone-resistant mutants of Escherichia coli DNA topoisomerase IV parC gene. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:710–714. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.3.710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luttinger A. The twisted ’life’ of DNA in the cell: bacterial topoisomerases. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:601–660. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lynn R, Giaever G, Swanberg S L, Wang J C. Tandem regions of yeast DNA topoisomerase II share homology with different subunits of bacterial gyrase. Science. 1986;233:647–649. doi: 10.1126/science.3014661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morrissey I, Hoshino K, Sato K, Yoshida A, Hayakawa I, Bures M G, Shen L L. Mechanism of differential activities of ofloxacin enantiomers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1775–1784. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.8.1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muñoz R, de la Campa A G. ParC subunit of DNA topoisomerase IV of Streptococcus pneumoniae is a primary target of fluoroquinolones and cooperates with DNA gyrase A subunit in forming resistance phenotype. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2252–2257. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.10.2252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakane T, Iyobe S, Sato K, Mitsuhashi S. In vitro antibacterial activity of DU-6859a, a new fluoroquinolone. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2822–2826. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.12.2822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. Approved standard M7-A3. 3rd ed. Villanova, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pan X S, Ambler J, Mehtar S, Fisher L M. Involvement of topoisomerase IV and DNA gyrase as ciprofloxacin targets in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2321–2326. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.10.2321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robinson M J, Martin B A, Gootz T D, McGuirk P R, Moynihan M, Sutcliffe J A, Osheroff N. Effects of quinolone derivatives on eukaryotic topoisomerase II. A novel mechanism for enhancement of enzyme-mediated DNA cleavage. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:14585–14592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robinson M J, Martin B A, Gootz T D, McGuirk P R, Osheroff N. Effects of novel fluoroquinolones on the catalytic activities of eukaryotic topoisomerase II: Influence of the C-8 fluorine group. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:751–756. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.4.751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sato K, Hoshino K, Tanaka M, Hayakawa I, Osada Y. Antimicrobial activity of DU-6859, a new potent fluoroquinolone, against clinical isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:1491–1498. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.7.1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shen L L, Baranowski J, Pernet A G. Mechanism of inhibition of DNA gyrase by quinolone antibacterials: specificity and cooperativity of drug binding to DNA. Biochemistry. 1989;28:3879–3885. doi: 10.1021/bi00435a038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shen L L, Kohlbrenner W E, Weigl D, Baranowski J. Mechanism of quinolone inhibition of DNA gyrase. Appearance of unique norfloxacin binding sites in enzyme-DNA complexes. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:2973–2978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shen L L, Mitscher L A, Sharma P N, O’Donnell T J, Chu D W, Cooper C S, Rosen T, Pernet A G. Mechanism of inhibition of DNA gyrase by quinolone antibacterials: a cooperative drug-DNA binding model. Biochemistry. 1989;28:3886–3894. doi: 10.1021/bi00435a039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tanaka M, Hoshino K, Hohmura M, Ishida H, Kitamura A, Sato K, Hayakawa I, Nishino T. Effect of growth conditions on antimicrobial activity of DU-6859a and its bactericidal activity determined by the killing curve method. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996;37:1091–102. doi: 10.1093/jac/37.6.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tanaka M, Onodera Y, Uchida Y, Sato K, Hayakawa I. Inhibitory activities of quinolones against DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV purified from Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2362–2366. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.11.2362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoshida H, Nakamura M, Bogaki M, Nakamura S. Mechanism of action of quinolones against Escherichia coli DNA gyrase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:839–845. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.4.839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]