Abstract

Our sense of smell enables us to navigate a vast space of chemically diverse odor molecules. This task is accomplished by the combinatorial activation of approximately 400 odorant G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) encoded in the human genome1-3. How odorants are recognized by odorant receptors (ORs) remains mysterious. Here we provide mechanistic insight into how an odorant binds a human odorant receptor. Using cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM), we determined the structure of active human OR51E2 bound to the fatty acid propionate. Propionate is bound within an occluded pocket in OR51E2 and makes specific contacts critical to receptor activation. Mutation of the odorant binding pocket in OR51E2 alters the recognition spectrum for fatty acids of varying chain length, suggesting that odorant selectivity is controlled by tight packing interactions between an odorant and an odorant receptor. Molecular dynamics simulations demonstrate propionate-induced conformational changes in extracellular loop 3 activate OR51E2. Together, our studies provide a high-resolution view of chemical recognition of an odorant by a vertebrate OR, providing insight into how this large family of GPCRs enables our olfactory sense.

INTRODUCTION

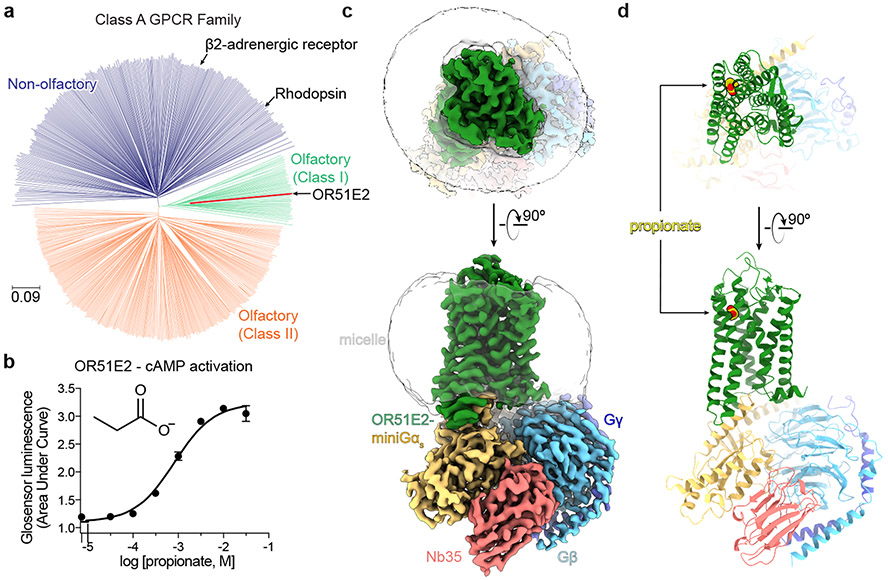

Our sense of smell relies on our ability to detect and discriminate a vast array of volatile odor molecules. The immense chemical diversity of potential odorants, however, poses a central challenge for the olfactory system of all animals. In vertebrates, the vast majority of odorants are detected by odorant receptors (ORs), which are G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) expressed in olfactory sensory neurons (OSNs) projecting from the olfactory epithelium to the olfactory bulb in the brain1,3. To detect and discriminate the vast diversity of potential odorants4, the OR gene family has expanded dramatically in vertebrate genomes, with some species encoding thousands of OR genes5. In humans, the approximately 400 functional ORs constitute half of the broader class A GPCR family (Fig. 1a)6-8.

Figure 1. Structure of human odorant receptor OR51E2.

a) Phylogenetic tree of human Class A GPCRs, including both non-olfactory (blue) and odorant receptors. Odorant receptors are further divided into Class I (green) and Class II (orange). OR51E2 is a Class I OR. The phylogenetic distance scale is represented on the left bottom corner (the distance represents 9% differences between sequences). b) Real-time monitoring of cAMP concentration assay showing that human OR51E2 responds to the odorant propionate. Data points are mean ± standard deviation from n = 4 replicates. Cryo-EM density map (c) and ribbon model (d) of active human OR51E2 bound to propionate (yellow spheres). OR51E2 is fused to miniGαs and bound to both Gβγ and the stabilizing nanobody Nb35.

Odorant stimulation of ORs activates signaling pathways via the stimulatory G protein Golf, which ultimately leads to excitation of OSNs9. Each OR can only interact with a subset of all potential odorants. Conversely, a single odorant can activate multiple ORs2. This principle of molecular recognition enables a central neural logic of olfaction where the perception of smell arises from the combinatorial activity of multiple unique ORs that respond to an individual odorant2. Because each mature OSN expresses only a single OR gene10, understanding how an individual OR is activated provides direct insight into the sensory coding of olfaction.

To understand olfaction at a fundamental level, we need a structural framework describing how odorants are recognized by ORs. Although recent structures of insect odorant-gated ion channels have begun to decipher this molecular logic11,12, the molecular rules that govern odorant recognition in vertebrate ORs are likely distinct and remain obscure. Here, we used cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) to determine the structure of a human OR activated by an odorant. This structure reveals specific molecular interactions that govern odorant recognition and provides a foundation for understanding how odorant binding activates ORs to instigate cellular signaling.

Structure of odorant bound OR51E2

Several challenges have limited structural interrogation of vertebrate ORs, including low expression levels in heterologous systems, low solubility of most volatile odorants, and precipitous instability of purified ORs13-16. We therefore sought to identify a human OR that overcomes these challenges. We prioritized a subset of ORs that are also expressed in tissues outside of OSNs with chemoreceptive functions that are independent of olfaction17. The ability of these ORs to function in non-olfactory tissue suggested that they may be more amenable to expression in heterologous cell expression systems that lack olfactory-tissue specific chaperones14. In a second line of reasoning, we prioritized Class I (so called “fish-like”) ORs as these receptors generally recognize water-soluble odorants18. By contrast, Class II ORs tend to respond to more hydrophobic odorants. Additionally, Class I ORs induce decreased levels of endoplasmic reticulum stress compared to Class II ORs19, and are therefore likely to yield increased expression in heterologous cells. Finally, we prioritized ORs that are conserved across evolution, potentially because they recognize odorants that are critical for animal survival across many species5. We reasoned that such ORs may be more constrained by evolution for stability. With this approach, we identified human OR51E2 as an ideal candidate for structure determination (Extended Data Fig. 1). OR51E2 is a Class I OR that responds to the short chain fatty acid propionate20 (Fig. 1a,b). In addition to its olfactory function, OR51E2 and its mouse ortholog Olfr78 are expressed in several other tissues to enable chemoreception of short chain fatty acids21-26. Consistent with our reasoning, OR51E2 emerged as one of the most highly expressed ORs in HEK293T cells among hundreds of human and mouse ORs that we have previously tested13.

To further stabilize OR51E2, we aimed to isolate OR51E2 in a complex with a heterotrimeric G protein. ORs couple with the two highly homologous stimulatory G proteins Gαolf and Gαs. In mature OSNs, ORs activate Gαolf to stimulate cAMP production via adenylyl cyclase9. In immature OSNs, ORs activate adenylyl cyclase via Gαs to drive accurate anterior-posterior axon targeting27. Furthermore, OR51E2 signals via Gαs outside of the olfactory system in tissues lacking Gαolf 22. The ability of OR51E2 to signal physiologically via Gαs, combined with the availability of a nanobody (Nb35) that stabilizes GPCR-Gαs complexes28, prompted us to focus on purifying an OR51E2-Gs complex. To do so, we generated an OR51E2 construct with a C-terminally fused “miniGɑs” protein. The miniGɑs protein is engineered to trap the receptor-interacting conformation of Gɑs in the absence of any guanine nucleotide29. Fusion of the miniGs to OR51E2 fully blocked propionate stimulated cAMP signaling in HEK293T cells (Extended Data Fig. 2b). We surmised that miniGαs tightly engages the seven transmembrane (7TM) core of OR51E2 to preclude endogenous Gɑs coupling and cAMP production.

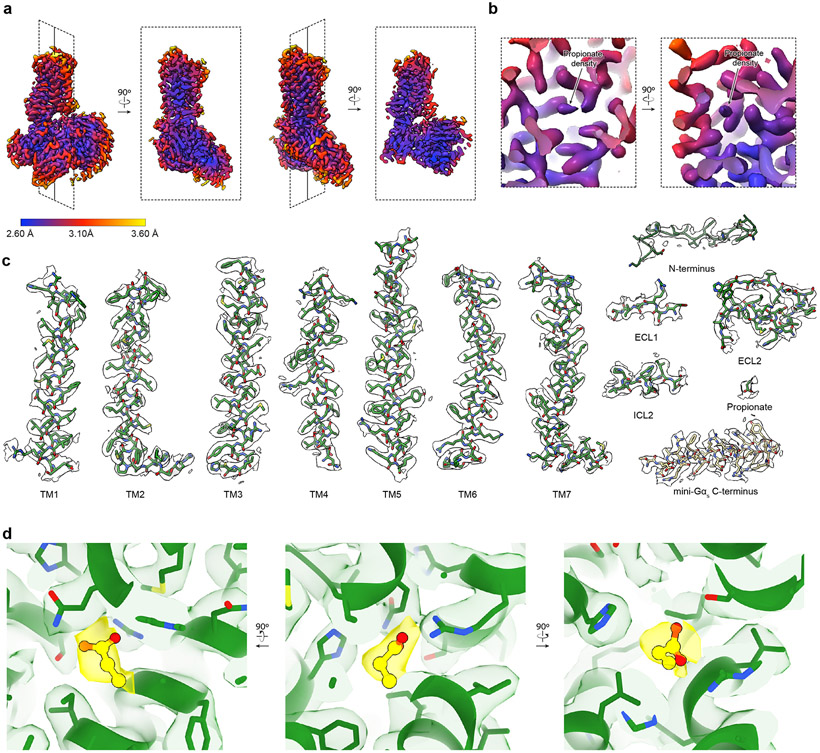

We purified OR51E2-miniGs in the presence of 30 mM propionate, and then further generated a complex with recombinantly purified Gβ1γ2 and Nb35 (Extended Data Fig. 2a and c). The resulting preparation was vitrified and analyzed by single particle cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) (Extended Data Fig 3 and Extended Data Table 1), which yielded a 3.1 Å resolution map of OR51E2 bound to the Gs heterotrimer. We additionally generated a map with focused refinement on only the 7TM domain of OR51E2, which afforded improved map resolution of the binding site and extracellular loops of the receptor (Extended Data Fig. 3e). The resulting reconstructions allowed us to model the OR51E2 7TM domain, the propionate ligand, and the Gs heterotrimer (Fig. 1c,d and Extended Data Fig. 4a-c).

Odorant binding pocket

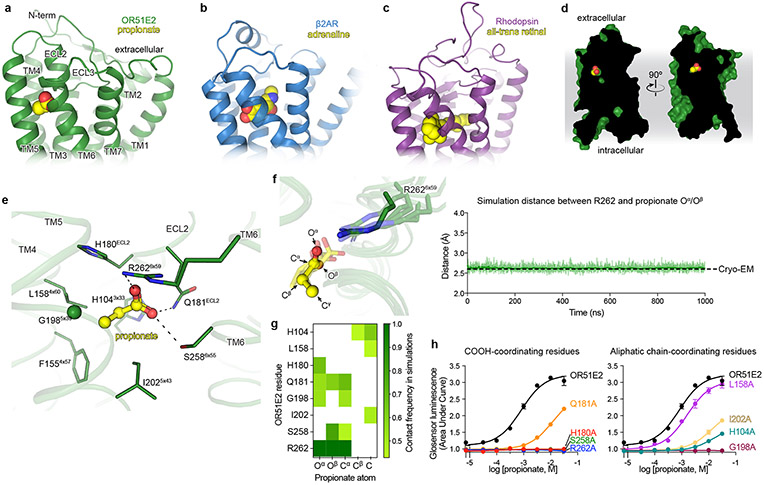

We identified cryo-EM density for propionate in a region bounded by transmembrane helices (TM) 3, 4, 5, and 6 in OR51E2 (Fig. 2a and Extended Data Fig. 4b,d). The propionate odorant binding pocket in OR51E2 is in a similar general region as ligand binding pockets in two prototypical Class A GPCRs: the adrenaline binding site in the β2-adrenergic receptor (β2-AR)30 and all-trans retinal in rhodopsin31 (Fig. 2a-c). Compared to the β2-AR and rhodopsin, the odorant binding pocket in OR51E2 is smaller and does not engage TM2 and TM7. Extensive packing of the OR51E2 N-terminus with extracellular loops 1 and 2 (ECL1 and ECL2) diminishes the potential size of the odorant binding pocket. Notably, unlike many class A GPCRs with diffusible agonists, the binding pocket for propionate is fully occluded from the extracellular milieu (Fig. 2d).

Figure 2. Odorant binding pocket in OR51E2.

Comparison of propionate binding site in OR51E2 (a) to two other prototypical Class A GPCRs, the β2-adrenergic receptor (β2AR) bound to adrenaline (PDB 4LDO)30 (b) and rhodopsin bound to all-trans retinal (PDB 6FUF)31 (c). Propionate primarily contacts TM4, TM5, TM6 and ECL2. By contrast adrenaline and all-trans retinal make more extensive contacts with other GPCR transmembrane helices. d) The binding site of propionate in active OR51E2 is occluded from extracellular solvent. e) Close-up view of propionate binding site in OR51E2. f) Representative molecular dynamics simulations snapshots of OR51E2 bound to propionate are shown as transparent sticks and overlaid on the cryo-EM structure. Displayed are the last snapshots of each simulation replicate, after 1000 ns of simulation time. R2626x59 makes a persistent contact with propionate over 1000 ns of an individual simulation (see Extended Data Fig. 8 for data on other simulation replicates. The complete MD simulation statistics are given in Supplementary Information Table 1 to 6). The minimum distance between any of R2626x59 sidechain nitrogens and propionate oxygens is shown. g) Heatmap of contact frequencies of interaction between OR51E2 binding site residues and propionate atoms (as labeled in (f)) obtained from five independent molecular dynamics simulations each 1 μs long (total time 5 μs). Contact frequency cutoff between receptor residue and ligand atoms were set at 40%. h) Alanine mutagenesis analysis of propionate-contacting residues in OR51E2 using a real-time monitoring of cAMP concentration assay. Data points are mean ± standard deviation from n = 3 experiments.

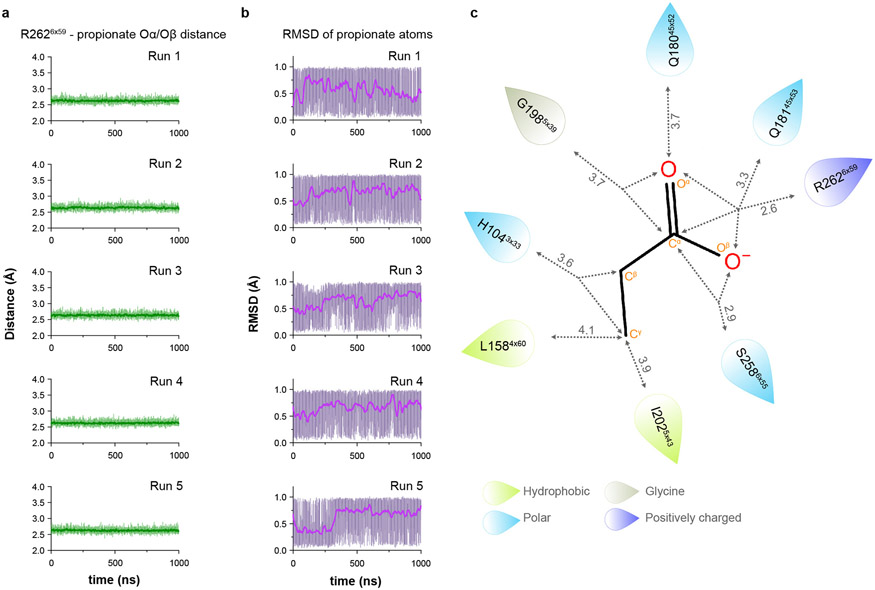

Propionate makes several contacts within the OR51E2 odorant binding pocket. The carboxylic acid of propionate engages R2626x59 (superscript numbers indicate generic GPCR numbering following the revised Ballesteros-Weinstein system for Class A GPCRs32-34) in TM6 as a counter-ion. The same propionate functional group also engages in hydrogen bonding interactions with S2586x55 and Q18145x53 in ECL2 (Fig. 2e). We used molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to understand whether these interactions are stable. We performed five 1 μs simulations of OR51E2 bound to propionate, but in the absence of the Gs heterotrimer. During these simulations, we observed that the carboxylic group of propionate forms a persistent interaction with R2626x59, with an average distance that is identical to that observed in the cryo-EM structure (Fig. 2f and Extended Data Fig. 5). Simulations also supported persistent interactions between the propionate carboxylic group and S2586x55, with additional contacting residues outlined in Fig 2g. Indeed alanine mutations for these carboxylic group coordinating residues, with the exception of Q18145x53, abolished propionate induced activation of OR51E2 (Fig. 2h).

The van-der Waals contacts between the propionate aliphatic group and OR51E2 are governed by tight packing interactions. The aliphatic portion of propionate contacts residues in TM3 (H1043x33), TM4 (F1554x57 and L1584x60), and TM5 (G1985x39 and I2025x43). Unlike the persistent contacts observed for the oxygens in the carboxylic acid group, interactions between specific propionate carbon atoms and aliphatic residues in OR51E2 were more dynamic in simulations (Fig. 2g) and showed minimal contact with F1554x57. However, alanine mutations to G1985x39, I2025x43 and H1043x33 decreased propionate activity at OR51E2, suggesting that there are specific spatial requirements for propionate to bind and activate the receptor. By contrast, propionate is only moderately less efficacious at OR51E2 with the L1584x60A mutation (Fig. 2h), likely because this residue only engages the distal Cγ carbon of propionate. OR51E2 therefore recognizes propionate with specific ionic and hydrogen bonding interactions combined with more distributed van der Waals interactions with tight shape complementarity.

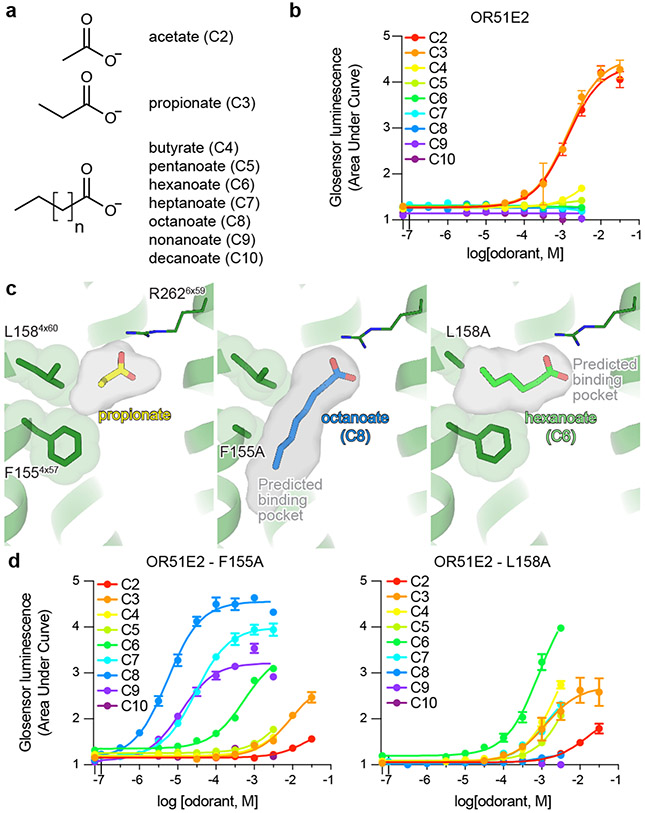

Tuning odorant receptor selectivity

Many ORs are capable of responding to a wide diversity of chemically distinct odorants2,20. Class I ORs, by contrast, are generally more restricted to carboxylic acid odorants35. We tested the selectivity of OR51E2 for fatty acid odorants of various chain lengths to understand how structural features in the receptor lead to odorant specificity. Consistent with previous reports25,36, we identified that acetate (C2) and propionate (C3) activate OR51E2 with millimolar potency (Fig. 3a,b). By contrast, longer chain length fatty acids (C4-C10) were either poorly or not active at OR51E2.

Figure 3. Tuning OR51E2 odorant selectivity.

a,b) OR51E2 responds selectively to the short chain fatty acids acetate and propionate as measured by a cAMP production assay. c) Docked poses of octanoate (C8) and hexanoate (C6) are shown in the predicted binding cavities of homology modeled OR51E2 mutants F1554x57A and L1584x60A. Binding pocket cavities are shown as gray surface. Replacement of F1554x57 and L1584x60 with alanine is predicted to yield a binding pocket with increased volume capable of accommodating longer chain fatty acids. d) The F1554x57A and L1584x60A mutations in OR51E2 lead to increased sensitivity to long chain fatty acids. Conversely, the potency for acetate and propionate is reduced for these two mutants. Data points in b and d are mean ± standard deviation from n = 4 experiments.

We speculated that the selectivity of OR51E2 for short chain fatty acids arises from the restricted volume of the occluded binding pocket (31 Å3), which would accommodate short chain fatty acids like acetate and propionate but would preclude binding of fatty acids with longer aliphatic chain lengths (Fig. 3c). We therefore hypothesized that the volume of the binding pocket acts as a selectivity determinant for fatty acid chain length. To directly test this hypothesis, we designed two mutations that are predicted to result in increased binding pocket volumes while maintaining the specific contacts with R2626x59 important for fatty acid activation of OR51E2. More specifically, we mutated two residues that are proximal to the carbon chain of propionate: F1554x57 and L1584x60. Computational modeling of the F1554x57A and L1584x60A mutations predicted pocket volumes of 90 Å3 and 68 Å3 respectively, suggesting that both mutants should sufficiently accommodate fatty acids with longer chain length (Fig. 3c). Indeed in cAMP assays, both the F1554x57A and L1584x60A OR51E2 mutants were broadly responsive to longer chain fatty acids (Fig. 3d, Extended Data Table 2 and 3). The size of each binding pocket was correlated with the maximum chain length tolerated and, additionally, which chain length has the greatest potency. For example, F1554x57A is responsive to a range of fatty acids (C2-C9), with octanoate (C8) displaying maximal potency and efficacy. By contrast, hexanoate (C6) is the most efficacious agonist at the L1584x60A mutant. For both of these mutations, the potency of acetate and propionate is reduced compared to OR51E2, suggesting that tight packing interactions with the aliphatic chain is an important determinant of agonist potency.

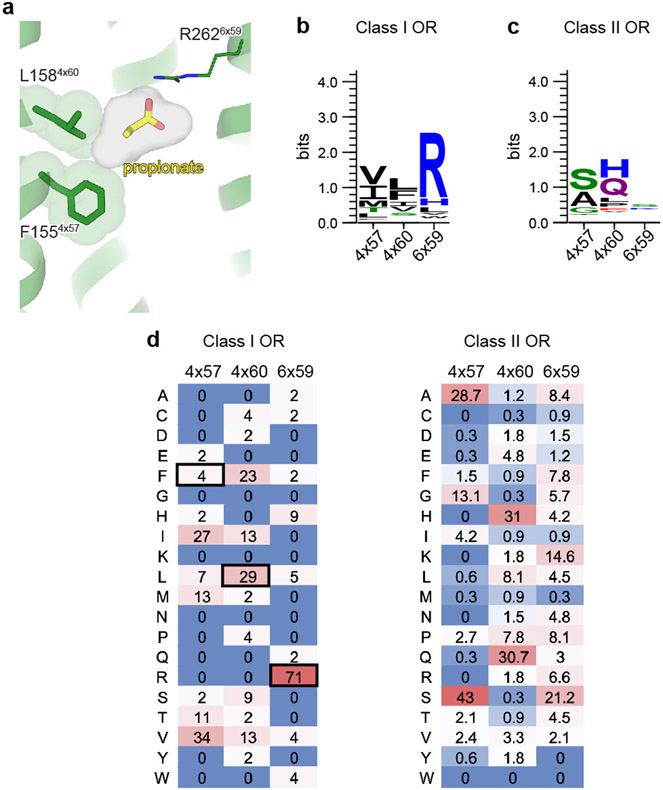

We next examined the conservation of selectivity-determining residues in both human Class I and Class II ORs. Reflecting its importance in carboxylic acid recognition, arginine is highly conserved in the 6x59 position in most human Class I ORs (Class I 71% vs Class II 7%) (Extended Data Fig. 6). Positions 4x57 and 4x60 in all human Class I ORs are constrained to aliphatic amino acids of different size (V/I/L/M/F, Class I >80% vs Class II <15%). By contrast, none of these positions have similar constraints in Class II ORs. We surmise that the conserved residue R6x59 may anchor odorants in many Class I OR binding pockets, while diversity in the 4x57, 4x60, and other binding pocket positions tune the binding pocket to enable selective recognition of the remainder of the molecule. Indeed OR51L1 and OR51E1 contain substitutions at either 4x57, 4x60 or other binding pocket residues, which likely enables these receptors to respond to longer chain fatty acids20. Two features may therefore drive odorant recognition for Class I ORs: 1) hydrogen-bonding or ionic interactions that anchor polar features of odorants to conserved OR binding pocket residues, and 2) van-der Waals interactions of diverse aliphatic residues in the OR binding pocket that define a closed volume having a geometry that closely matches the shape of cognate odorants.

Activation mechanisms of OR51E2

Odorant binding to ORs is predicted to cause conformational changes in the receptor that enable G protein engagement. Our strategy to stabilize OR51E2 with miniGs precluded structure determination of inactive OR51E2 in the absence of an odorant. We therefore turned to comparative structural modeling, mutagenesis studies, and molecular dynamics simulations to understand the effect of propionate binding on the conformation of OR51E2.

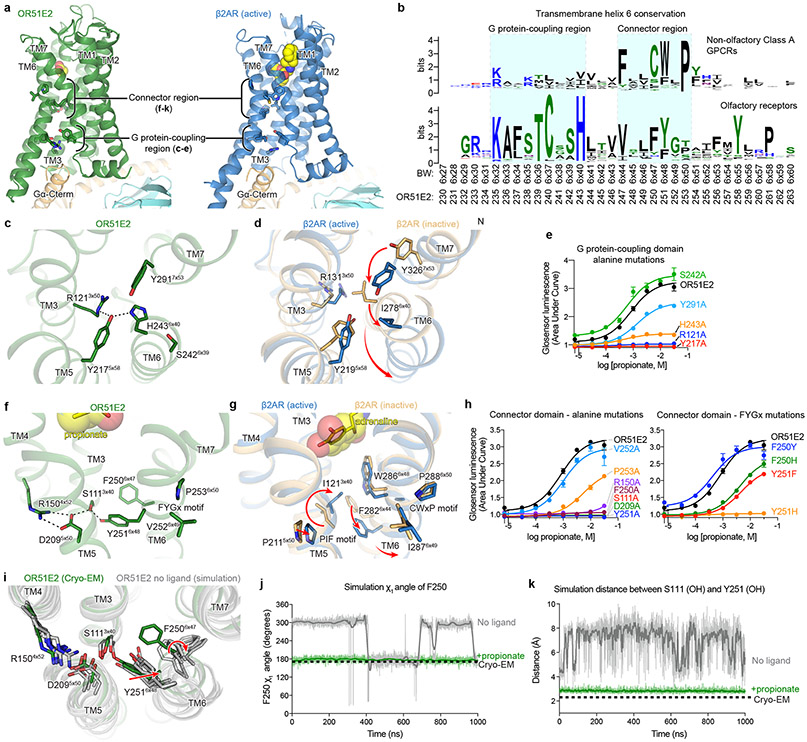

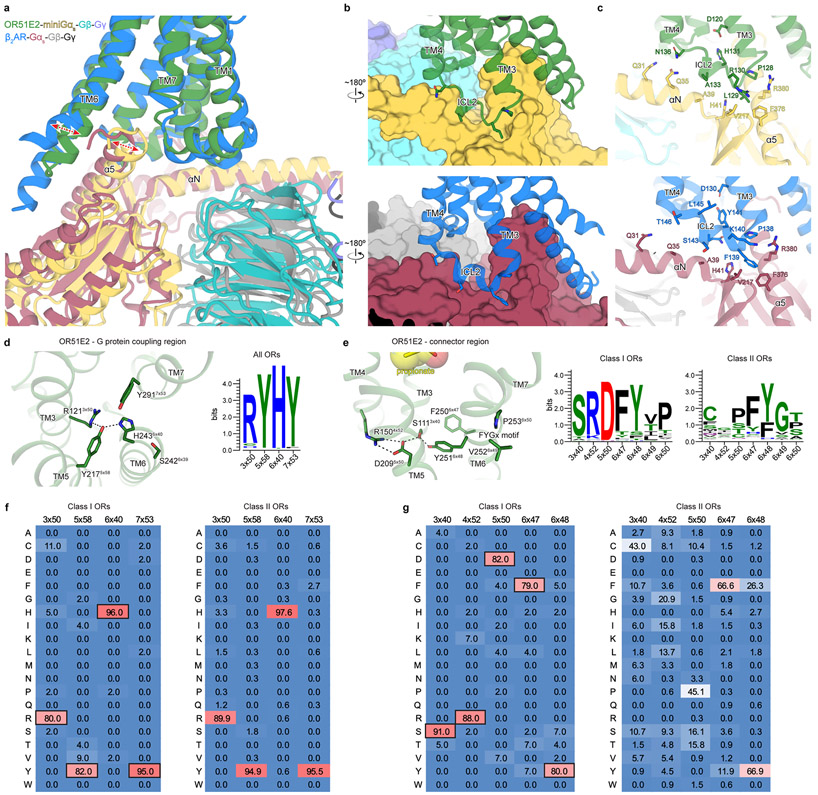

Comparison of active OR51E2 to Gs-coupled, active state β2-adrenergic receptor (β2-AR) demonstrated that both receptors engage the G protein with a similar overall orientation of the 7TM domain and Gαs (Fig. 4a and Extended Data Fig. 7). A central hallmark of Class A GPCR activation is an outward displacement and rotation of TM6 in the cytoplasmic side of the receptor, which is accompanied by more subtle movement of the other TM helices37-39. These conformational changes create a cavity for the G protein C-terminal α-helix. Prior structural biology studies have identified two regions conserved in Class A GPCRs that are critically important for allosteric communication between the agonist binding site and the G protein-binding site: a connector region that is adjacent to the ligand binding site and a G protein-coupling region adjacent to the Gαs C-terminal α-helix37 (Fig. 4a). We aimed to understand how propionate binding to OR51E2 stabilizes these regions in an active conformation. Although the overall conformation of OR51E2 and β2-AR are similar (root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of 3.1 Å over all resolved Cα atoms, see Supplementary Table 8), the specific sequences that define the G protein-coupling and connector regions are distinct between ORs and non-olfactory Class A GPCRs. Comparison of sequence conservation in TM6 between human ORs and non-olfactory Class A GPCRs revealed a highly conserved motif (KAFSTCxSH6x40) in the G protein coupling region in ORs that is absent in non-odorant receptors (Fig. 4b). By contrast, the highly conserved CWxP6x50 motif in the connector region of Class A GPCRs is absent in ORs. Instead ORs contain the previously described FYGx6x50 motif in the connector region40 (Fig. 4f,g).

Figure 4. Activation mechanism of OR51E2.

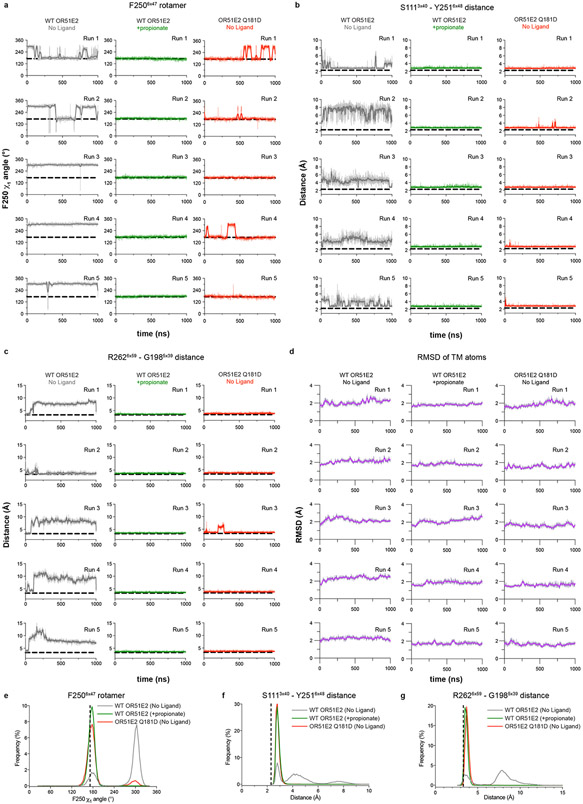

a) Ribbon diagram comparing structures of propionate-bound OR51E2-miniGs complex (green) to BI-167107 bound β2AR-Gs complex (blue, PDB 3SN6). For both receptors, the connector region couples conformational changes at the ligand binding site with the G protein-coupling region. b) Weblogo depicting conservation of transmembrane helix 6 in either human odorant receptors or human non-olfactory Class A GPCRs. Amino acid numbering for OR51E2 and Ballosteros-Weinsten (BW) are indicated. Close-up view of the G protein-coupling domain in active OR51E2 (c) and both active and inactive β2AR (d). Activation of β2AR is associated with an inward movement of TM7 and a contact between Y2195x58 and Y3267x53. In OR51E2, H2436x40 interacts with Y2175x58 in the active state. e) Alanine mutagenesis of G protein-coupling domain residues in OR51E2 using a real-time cAMP concentration assay. Close-up views of the connector region in active OR51E2 (f) and both active and inactive β2AR (g). h) Mutagenesis of connector region residues in OR51E2 using a real-time cAMP concentration assay. i) Molecular dynamics simulations of OR51E2 with propionate removed. Snapshots displayed are the last snapshot from each of the five independent simulation replicates after 1000 ns of simulation time. Simulations show increased flexibility of TM6 in the connector region residues. Snapshots extracted from unbiased clustering analysis of the entire ensemble of MD trajectories show similar structural changes as these last snapshots (see Methods section, Supplementary Table 7 and Supplementary Fig. 1). Molecular dynamics trajectories for a representative simulation showing rotation of side chain rotamer angle of F2506x47 (j) and minimum distance between S1113x40 and Y2516x48 hydroxyl groups (k) performed with or without propionate over the course of 1000 ns MD simulation (see Extended Data Fig. 8 for simulation replicates). Thick traces represent smoothed values with an averaging window of 8 nanoseconds; thin traces represent unsmoothed values. Data points in e and h are mean ± standard deviation from n = 4 experiments.

Closer inspection of the G protein-coupling region in OR51E2 revealed a unique hydrogen-bonding network between the highly conserved residues R1213x50 in TM3, H2436x40 in TM6 and Y2175x58 in TM5 that is not observed in other Class A GPCRs (Fig. 4c,d). Activation of the β2-AR is associated with an inward movement of TM7 that positions Y3167x53 within a water-mediated hydrogen bonding distance of Y2195x58; this movement leads to outward movement of TM6 by displacing the aliphatic I2786x40 residue (Fig. 4d). Given the high conservation of R3x50, H6x40 and Y5x58 across all ORs (89%, 97% and 93%, respectively, Extended Data Fig. 7), we propose that this contact is important in stabilizing the OR active conformation. Indeed, alanine mutagenesis of OR51E2 residues in the G protein coupling region show a dramatic loss of activity for H2436x40, Y2175x58, and R1213x50 mutants associated with poor receptor expression (Fig. 4e and Extended Data Table 2). Mutation of Y2917x53 in OR51E2, by contrast, has a more modest effect on propionate activity.

We next examined the connector region of OR51E2 directly adjacent to the propionate binding site (Fig. 4f). Activation of the β2-AR is associated with a rearrangement of the PIF motif between positions I3x40 (TM3), P5x50 (TM5), and F6x44 (TM6), which leads to an outward displacement of TM6 at the intracellular side. This coordinated movement has been shown in the majority of class A GPCRs by comparative analysis of available active and inactive state structures37-39. Conservation at the PIF positions is low in ORs, suggesting an alternative mechanism. In OR51E2, we observe an extended hydrogen bonding network between Y2516x48 of the OR-specific FYGx motif and residues in TM3 (S1113x40), TM4 (R1504x52), and TM5 (D2095x50). Notably, the intramembrane ionic interaction between D2095x50 and R1504x52 is likely only conserved in Class I ORs (Class I: D5x50-82%, R4x52-88%, Class II: D5x50-0.3%, R4x52-0%, Extended Data Fig. 7). Alanine mutagenesis of most residues in this connector region of OR51E2 abolishes response to propionate (Fig. 4h), in part because mutations in this region dramatically decrease receptor expression (Extended Data Table 2). More conservative substitutions to F2506x47 or Y2516x48 also show impairment in OR51E2 function, suggesting that the specific contacts observed in active OR51E2 are important for robust receptor activation.

We turned to molecular dynamics simulations to examine how ligand binding influences the conformation of the connector region. After removing the G protein, we simulated OR51E2 with and without propionate in the binding site. For each condition, we performed five 1 μs simulations. OR51E2 simulated with propionate remains in a conformation similar to the cryo-EM structure. In the absence of propionate, the connector region of OR51E2 displays more flexibility in simulations (Fig. 4i and Extended Data Fig. 8). In both of these conditions, we do not observe deactivation of OR51E2, likely because this transition requires greater than 1 μs of simulation time41. We observed two motions in the FYGx motif associated with this increased conformational heterogeneity: a rotameric flexibility of F2506x47 between the experimentally observed conformation and alternative rotamers and a disruption of a hydrogen bond between Y2516x48 and S1113x40 (Fig. 4j,k and Extended Data Fig. 8). Simulations without propionate show that the distance between the hydroxyl groups of Y2516x48 and S1113x40 is >4 Å, indicating the loss of a hydrogen bond that was observed in both the cryo-EM structure of OR51E2 and the MD simulations with propionate (Fig. 4k and Extended Data Fig. 8). Based on structural comparison to other Class A GPCRs, mutagenesis studies, and molecular dynamics simulations, we therefore propose that odorant binding stabilizes the conformation of an otherwise dynamic FYGx motif to drive OR activation.

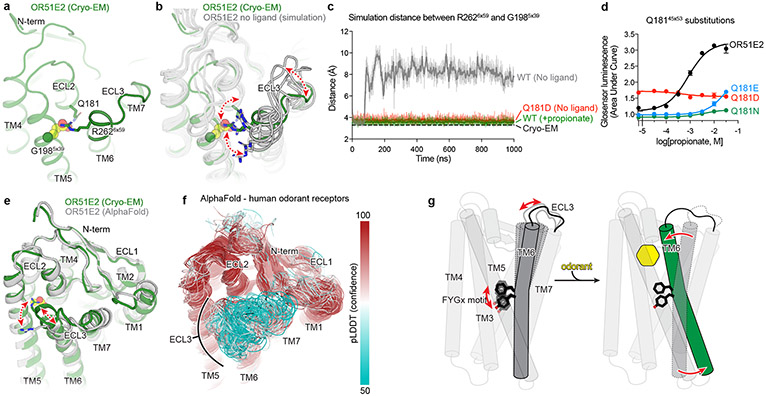

Structural dynamics of ECL3 in OR function

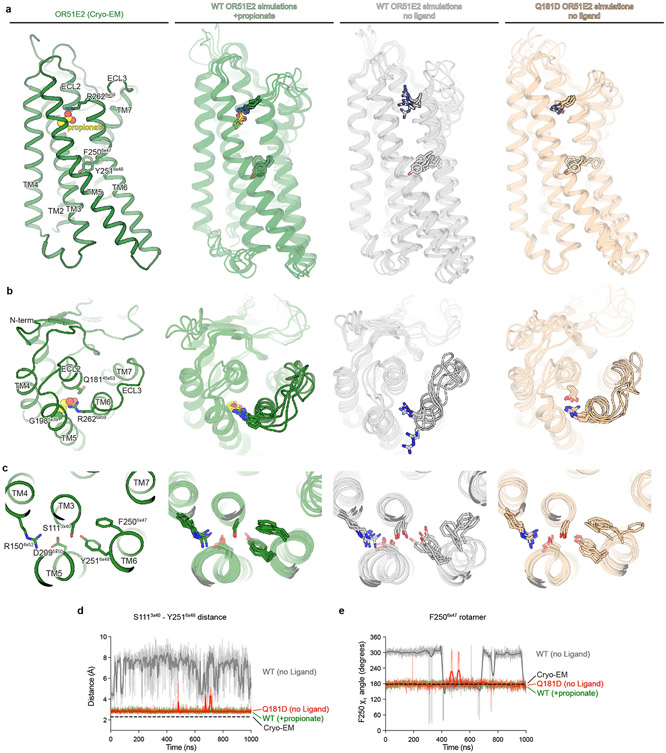

Odorant receptors display substantial sequence variation in extracellular loop 3 (ECL3), a region previously shown to be critical for recognition of highly diverse odorants42,43 . We therefore aimed to understand the involvement of ECL3 in propionate binding to OR51E2, and more generally, how ECL3 may drive the conformational changes in TM6 necessary for OR activation (Fig. 5). In our structure of OR51E2, ECL3 is directly coupled to odorant binding via a direct interaction between the carboxylic acid moiety of propionate and the ECL3 adjacent residue R2626x59 (Fig. 5a). In order to investigate the role of R2626x59 in maintaining the conformation of ECL3 by binding the odorant, we analyzed simulations of OR51E2 performed without propionate. In the absence of coordination with the carboxylic acid group of propionate, R2626x59 showed a marked increase in flexibility, with an outward movement of up to 8 Å away from the ligand binding site (Fig. 5b and c). This movement is accompanied by displacement of ECL3 away from the odorant binding pocket.

Figure 5: Structural dynamics of ECL3 in OR function.

a) Residue R2626x59 in ECL3 makes a critical contact with propionate. Residue Q18145x53 in ECL2 is highlighted. b) Molecular dynamics simulations of OR51E2 with propionate removed shows increased flexibility of R2626x59. Representative snapshots are displayed from five independent simulation replicates after 1000 ns of simulation time. c) In simulations of wild-type (WT) OR51E2 bound to propionate, the minimum distance between R2626x59 and G1985x39 heavy atoms is stable and similar to the cryo-EM structure. Simulations of WT OR51E2 without propionate (no ligand) show increased minimum distance between R2626x59 and G1985x39. In simulations of Q18145x53D mutant without propionate, the minimum distance between R2626x59 and G1985x39 is similar to WT OR51E2 bound to propionate. Minimum distance was measured between R2626x59 sidechain atoms and G1985x39 main chain atoms (excluding the hydrogens) over the course of 1000 ns MD simulation (see Extended Data Fig. 8 for simulation replicates). Thick traces represent smoothed values with an averaging window of 8 nanoseconds; thin traces represent unsmoothed values. d) Conservative mutagenesis of Q18145x53 shows that the Q18145x53D mutant is constitutively active, potentially because it substitutes a carboxylic acid in the OR51E2 binding pocket. e) Comparison of cryo-EM structure of OR51E2 with the AlphaFold2 predicted structure shows high similarity in the extracellular domain with the exception of the ECL3 region. The AlphaFold2 model shows an outward displacement of R2626x59 and ECL3 similar to simulations of apo OR51E2. f) AlphaFold2 predictions for all human odorant receptors show low confidence in the ECL3 region and high confidence in other extracellular loops. g) A model for ECL3 as a key site for odorant receptor activation.

To test whether inward movement of R2626x59 is itself sufficient to activate OR51E2, we designed a gain-of-function experiment. We hypothesized that introduction of an acidic residue in the binding pocket with an appropriate geometry may substitute for the carboxylic acid of propionate and coordinate R2626x59. Indeed, substitution of Asp in position 45x53 (Q18145x53D) of OR51E2 yielded increased cAMP basal activity (Fig. 5d). By contrast, introduction of Glu in the same position (Q18145x53E) rendered OR51E2 largely inactive, suggesting the requirement for a precise coordination geometry for R2626x59. Substitution with the larger Gln (Q18145x53N) rendered OR51E2 completely unresponsive to propionate, either by sterically blocking R2626x59 or by displacing propionate itself. In simulations of OR51E2 with the Q18145x53D substitution, R2626x59 is persistently engaged toward the ligand binding site (Fig. 5b). Furthermore, this inward movement of R2626x59 and ECL3 is accompanied by activation-associated conformational changes in the connector domain of OR51E2 (Extended Data Fig. 9), perhaps explaining the basal activity of Q18145x53D mutant. Inward movement of ECL3 is therefore sufficient to activate OR51E2.

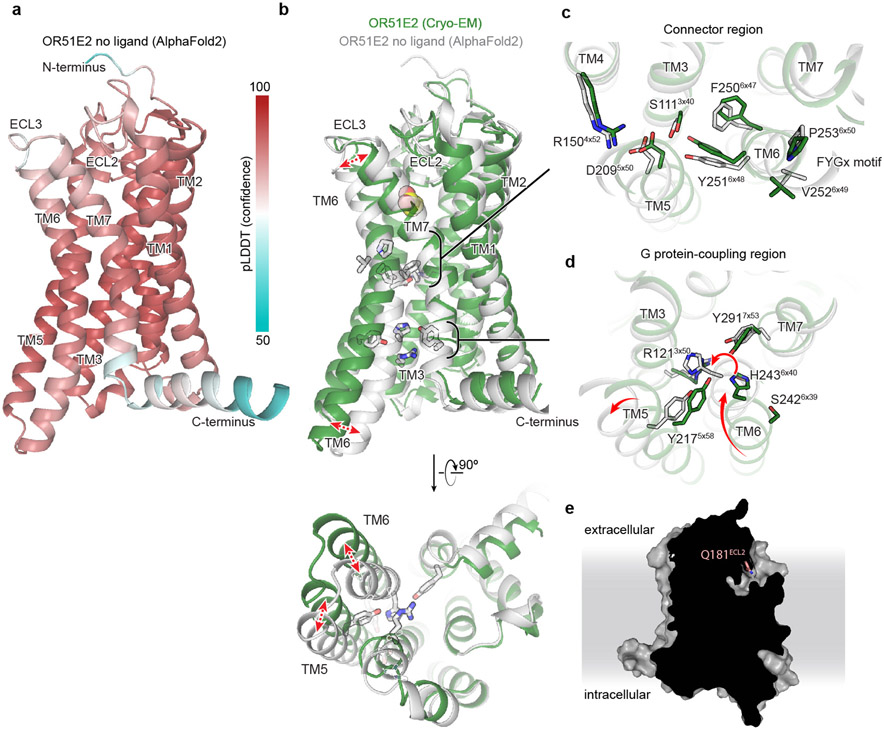

Because conformational changes in ECL3 are critical to OR51E2 activation, we speculated that this region may provide a common activation mechanism across the OR family. To probe this notion, we examined structural predictions of all human odorant receptors by AlphaFold244. We first compared the AlphaFold2 prediction for OR51E2 with the cryo-EM structure, which yielded a high degree of agreement reflected in a RMSD of 1.3 Å for Cα atoms. Importantly, the AlphaFold2 predicted structure of OR51E2 appears to be in an intermediate or inactive conformation characterized by outward displacement of R2626x59 and ECL3, a G protein-coupling domain in the inactive conformation, and TM6 more inwardly posed compared to active OR51E2 (Fig 5e and Extended Data Fig. 10). We next examined the predicted structures of all human ORs, which revealed a largely shared topology for the extracellular region for the broader family (Fig. 5f). Indeed, the per-residue confidence score from AlphaFold2 (predicted local distance difference test, pLDDT) for the N terminus, ECL1, and ECL2 are predicted with high confidence for the most ORs. By contrast, ECL3 shows lower pLDDT scores. Because low pLDDT scores correlate with disordered protein regions44, we surmise that, in the absence of odorant binding, the structure of ECL3 is less constrained compared to the rest of the odorant binding pocket for the broader OR family. Similar to OR51E2, odorant binding may therefore stabilize ECL3 to drive receptor activation for the broader OR family.

Discussion

We propose the following model for OR51E2 activation (Fig. 5g). In the unbound state, the extracellular segment of TM6 is dynamic. Upon binding of propionate, TM6 rotates inward towards the 7TM domain and is stabilized via a direct coordination of the propionate carboxylic acid via R2626x59. The conserved FYGx motif in TM6 acts as a structural pivot point around which TM6 rotates to displace the intracellular end of TM6 from the TM-core and open the canonical active G protein-binding site. Although specific interactions between the propionate aliphatic chain and residues within the binding site are important for achieving full potency of the odorant response, OR51E2 is constitutively active when an aspartate residue (Q18145x53D) is introduced in the binding pocket. This suggests that the observed rotation of TM6 mediated by coordination of R2626x59 with a stable anionic group in the binding site, in itself is sufficient for receptor activation. While this model remains speculative due to the lack of an experimentally-determined inactive-state structure of OR51E2, it integrates the findings from unique structural features of ORs compared to other Class A GPCRs, molecular dynamics simulations, and mutagenesis studies. A similar mechanism may be responsible for the activation of most Class I ORs, a large majority of which recognize carboxylic acids and contain an arginine at position 6x59. The mechanism of activation of Class II ORs, which recognize a broader range of volatile odorants and lack R6x59, could be potentially distinct.

Our work illuminates the molecular underpinnings of odorant recognition in a vertebrate Class I OR. While the full breadth of potential odorants that activate OR51E2 remains to be characterized, profiling of known fatty acid odorants suggests that OR51E2 is narrowly tuned to short chain fatty acids20,25. Propionate binds OR51E2 with two types of interactions - specific ionic and hydrogen bonding interactions that anchor the carboxylic acid, and more nonspecific hydrophobic contacts that rely on shape complementarity with the aliphatic portion of the ligand. We demonstrate that the specific geometric constraints imposed by the occluded OR51E2 odorant binding pocket are responsible, in part, for this selectivity. Molecular recognition in OR51E2 is therefore distinct from the distributed hydrophobic interactions that mediate odorant recognition at an insect odorant-gated ion channel12. We anticipate that the molecular mechanism we define here for OR51E2 is likely to extend to other Class I ORs that recognize polar, water soluble odorants with multiple hydrogen bond acceptors and donors. Molecular recognition by more broadly tuned ORs, and the larger Class II OR family, however, remains to be defined.

The structural basis of ligand recognition for OR51E2 also provides insight into evolution of the OR family. Unlike most vertebrate OR genes that have evolved rapidly via gene duplication and diversification, OR51E2 is one of a few ORs with strong evolutionary conservation within different species5. This constraint may result from recognition of odorants important for survival or from vital non-olfactory roles of OR51E2 activity detecting propionate and acetate, the main metabolites produced by the gut microbiota. Molecular recognition of propionate by OR51E2 may therefore represent a unique example of specificity within the broader OR family. While future work will continue to decipher how hundreds of ORs sense an immensely large diversity of odorants, our structure and mechanistic insight into OR51E2 function provides a new foundation to understand our sense of smell at an atomic level.

ONLINE METHODS

Expression and purification of OR51E2-miniGs protein

Human OR51E2 (Uniprot: Q9H255) was cloned into pCDNA-Zeo-TetO, a custom pcDNA3.1 vector containing a tetracycline inducible gene-expression cassette45. The construct included an N-terminal influenza hemagglutinin signal sequence and the FLAG (DYKDDDK) epitope tag. The construct further included the miniGs399 protein5, which was fused to the C-terminus of OR51E2 with a human rhinovirus 3C (HRV 3C) protease cleavage sequence flanked by Gly-Ser linkers.

The resulting construct (OR51E2-miniGs399) was transfected into 1 L of inducible Expi293F-TetR cells (unauthenticated and untested for mycoplasma contamination, Thermo Fisher) using the ExpiFectamine 293 Transfection Kit (Thermo Fisher) as per manufacturer’s instructions. After 16 hours, protein expression was induced with 1 μg/mL doxycycline hyclate (Sigma Aldrich), and the culture was placed in a shaking incubator maintaining 37°C and a 5% CO2 atmosphere. After 36 hours cells were harvested by centrifugation and stored at −80°C.

For receptor purification, cells were thawed and hypotonically lysed in 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.50, 1 mM EDTA, 30 mM sodium propionate (Sigma Aldrich), 100 μM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP, Fischer Scientific), 160 μg/mL benzamidine, 2 μg/mL leupeptin for 15 minutes at 4°C. Lysed cells were harvested by centrifugation at 16,000 x g for 15 min, and immediately dounce-homogenized in ice-cold solubilization buffer comprising 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.50, 300 mM NaCl, 1% (w/v) Lauryl Maltose Neopentyl Glycol (L-MNG, Anatrace), 0.1% (w/v) cholesteryl hemisuccinate (CHS, Steraloids), 30 mM sodium propionate, 5 mM adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP, Fischer Scientific), 2 mM MgCl2, 100 μM TCEP, 160 μg/mL benzamidine, and 2 μg/mL leupeptin. The sample was stirred for 2 hours at 4°C, and the detergent-solubilized fraction was clarified by centrifugation at 20,000 x g for 30 min. The detergent-solubilized sample was supplemented with 4 mM CaCl2 and incubated in batch with homemade M1-FLAG-antibody conjugated CNBr-sepharose under slow rotation for 1.5 hours at 4°C. The sepharose resin was transferred to a glass column and washed with 20 column volumes ice-cold buffer comprising 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.50, 300 mM NaCl, 0.05% (w/v) L-MNG, 0.005% (w/v) CHS, 30 mM sodium propionate, 2.5 mM ATP, 4 mM CaCl2, 2 mM MgCl2, and 100 μM TCEP. This was followed by 10 column volumes of ice-cold 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.50, 150 mM NaCl, 0.0075% (w/v) L-MNG, 0.0025% glyco-diosgenin (GDN, Anatrace), 0.001% (w/v) CHS, 30 mM sodium propionate, 4 mM CaCl2, and 100 μM TCEP. Receptor containing fractions were eluted with ice-cold 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.50, 150 mM NaCl, 0.0075% (w/v) L-MNG, 0.0025% (w/v) GDN, 0.001% (w/v) CHS, 30 mM sodium propionate, 5 mM EDTA, 100 μM TCEP, and 0.2 mg/mL FLAG peptide. Fractions containing OR51E2-miniGs399 fusion protein were concentrated in a 50 kDa MWCO spin filter (Amicon) and further purified over a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL (Cytiva) size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) column, which was equilibrated with 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.50, 150 mM NaCl, 0.005% (w/v) GDN, and 0.0005% CHS, 30 mM sodium propionate, and 100 μM TCEP. Fractions containing monodisperse OR51E2-miniGs399 were combined and concentrated in a 50 kDa MWCO spin filter prior to complexing with Gβ1γ2 and Nb35.

Expression and purification of Gβ1γ2

A baculovirus was generated with the pVLDual expression vector encoding both the human Gβ1 subunit with a HRV 3C cleavable N-terminal 6x His-tag and the untagged human Gγ2 subunit, in Spodoptera frugiperda Sf9 insect cells (unauthenticated and untested for mycoplasma contamination, Expression Systems). For expression, Trichoplusia ni Hi5 insect cells (unauthenticated and untested for mycoplasma contamination, Expression Systems) were infected at a density of 3.0 x 106 cells/mL with high titer Gβ1γ2-baculovirus, and grown at 27 °C with 130 rpm shaking. After 48 hours, cells were harvested and resuspended in lysis buffer comprising 20 mM HEPES, pH 8.00, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol (β-ME), 20 μg/mL leupeptin, and 160 μg/mL benzamidine. Lysed cells were pelleted at 20,000 x g for 15 min, and solubilized with 20 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 100 mM sodium chloride, 1% (w/v) sodium cholate (Sigma Aldrich), 0.05% (w/v) n-dodecyl-β-D-maltopyranoside (DM, Anatrace), and 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol (β-ME). Solubilized Gβ1γ2 was clarified by centrifugation at 20,000 x g for 30 min, and was then incubated in batch with HisPur Ni-NTA resin (Thermo Scientific). Resin-bound Gβ1γ2 was washed extensively, before detergent was slowly exchanged on-column to 0.1% (w/v) L-MNG, and 0.01% (w/v) CHS. Gβ1γ2 was eluted with 20 mM HEPES pH 7.50, 100 mM NaCl, 0.1% (w/v) L-MNG, 0.01% (w/v) CHS, 300 mM imidazole, 1 mM DL-Dithiothreitol (DTT), 20 μg/mL leupeptin, and 160 μg/mL benzamidine. Fractions containing Gβ1γ2 were pooled and supplemented with homemade 3C protease before overnight dialysis into buffer comprised of 20 mM HEPES pH 7.50, 100 mM NaCl, 0.02% (w/v) L-MNG, 0.002% (w/v) CHS, 1 mM DTT, and 10 mM imidazole. Uncleaved Gβ1γ2 was removed by batch incubation with Ni-NTA resin, before the unbound fraction containing cleaved Gβ1γ2 was dephosphorylated by treatment with lambda phosphatase (New England Biolabs), calf intestinal phosphatase (New England Biolabs), and antarctic phosphatase (New England Biolabs) for 1 hour at 4°C. Geranylgeranylated Gβ1γ2 heterodimer was isolated by anion exchange chromatography using a MonoQ 4.6/100 PE (Cytiva) column, before overnight dialysis in 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.50, 100 mM NaCl, 0.02% (w/v) L-MNG, and 100 μM TCEP. Final sample was concentrated on a 3 kDa MWCO spin filter (Amicon), and 20% (v/v) glycerol was added before flash freezing in liquid N2 for storage at −80°C.

Expression and purification of Nb35

DNA encoding Nb35 (described by Rasmussen et al.6) was cloned into a modified pET-26b expression vector harboring a C-terminal His-tag followed by a Protein C (EDQVDPRLIDGK) affinity tag. The resulting DNA was transformed into competent Rosetta2 (DE3) pLysS Escherichia coli (UC Berkeley QB3 MacroLab) and inoculated into 100 ml Luria Broth supplemented with 50 μg/mL kanamycin, which was cultured overnight with 220 rpm shaking at 37°C. The following day, the starter culture was inoculated into 8 x 1 L of Terrific Broth supplemented with 0.1% (w/v) dextrose, 2 mM MgCl2, and 50 μg/mL kanamycin which were further cultured at 37°C with shaking. Nb35 expression was induced at OD600 = 0.6, by addition of 400 μM Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG, GoldBio) and lowering the incubator temperature to 20°C. After 21 hours of expression, cells were harvested by centrifugation and were resuspended in SET Buffer comprising 200 mM tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane (Tris, Sigma Aldrich), pH 8.00, 500 mM sucrose, 0.5 mM EDTA, 20 μg/mL leupeptin, 160 μg/mL benzamidine, and 1 U benzonase. After 30 minutes of stirring at RT, hypotonic lysis was initiated by a 3-fold dilution with deionized water. Following 30 minutes of stirring at RT, ionic strength was adjusted to 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM CaCl2, and 2 mM MgCl2 and the lysate was cleared by centrifugation at 20,000 x g for 30 min. The cleared lysate was incubated in batch with homemade anti-Protein C antibody coupled CNBr-sepharose under slow rotation. The resin was extensively washed with buffer comprising 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.50, 300 mM NaCl, and 2 mM CaCl2, and Nb35 was eluted with 20 mM HEPES pH 7.50, 100 mM NaCl, 0.2 mg/mL Protein C peptide, and 5 mM EDTA. Nb35 containing fractions were concentrated in a 10 kDa MWCO spin filter (Amicon) and further purified over a Superdex S75 Increase 10/300 GL column (Cytiva) SEC column equilibrated with 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.50, and 100 mM NaCl. Fractions containing monodisperse Nb35 were concentrated and supplemented with 20% glycerol prior to flash freezing in liquid N2 for storage at −80°C.

Preparation of the active-state OR51E2-Gs complex

To prepare the OR51E2-Gs complex, a 2-fold molar excess of purified Gβ1γ2 and Nb35 was added to the SEC purified OR51E2-miniGs399 followed by overnight incubation on ice. The sample was concentrated on a 50 kDa MWCO spin filter (Amicon), and injected onto a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL SEC column, equilibrated with 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.50, 150 mM NaCl, 0.0075% (w/v) L-MNG, 0.0025% (w/v) GDN, 0.001% (w/v) CHS, and 30 mM sodium propionate. Fractions containing the monomeric OR51E2-Gs complex were concentrated on a 100 kDa MWCO spin filter immediately prior to cryo-EM grid preparation.

Cryo-EM vitrification, data collection, and processing

2.75 μL of purified OR51E2-Gs complex was applied to glow discharged 300 mesh R1.2/1.3 UltrAuFoil Holey gold support films (Quantifoil). Support films were plunge-frozen in liquid ethane using a Vitrobot Mark IV (Thermo Fisher) with a 10 s hold period, blot force of 0, and blotting time varying between 1-5 s while maintaining 100% humidity and 4°C. Vitrified grids were clipped with Autogrid sample carrier assemblies (Thermo Fisher) immediately prior to imaging. Movies of OR51E2-Gs embedded in ice were recorded using a Titan Krios Gi3 (Thermo Fisher) with a BioQuantum Energy Filter (Gatan) and a K3 Direct Electron Detector (Gatan). Data were collected using SerialEM 3.846 running a 3 x 3 image shift pattern at 0° stage tilt. A nominal magnification of 105,000 x with a 100 μm objective was used in super-resolution mode with a physical pixel size of 0.81 Å pixel−1. Movies were recorded using dose fractionated illumination with a total exposure of 50 e− Å−2 over 60 frames yielding 0.833 e− Å−2 frames−1.

16,113 super-resolution movies were motion-corrected and Fourier cropped to physical pixel size using UCSF MotionCor247. Dose-weighted micrographs were imported into cryoSPARC v3.2 (Structura Biotechnology48), and contrast transfer functions were calculated using the Patch CTF Estimation tool. A threshold of CTF fit resolution > 5 Å was used to exclude low quality micrographs. Particles were template picked using a 20 Å low-pass filtered model that was generated ab initio from data collected during an earlier 200 kV screening session. 8,884,130 particles were extracted with a box size of 288 pixels binned to 72 pixels and sorted with the Heterogeneous Refinement tool, which served as 3D classification with alignment. Template volumes for each of the four classes were low-pass filtered to 20 Å and comprised an initial OR51E2-Gs volume as well as three scrambled volumes obtained by terminating the Ab-Initio Reconstruction tool before the first iteration. The resulting 1,445,818 particles were re-extracted with a box size of 288 pixels binned to 144 pixels and sorted by an additional round of Heterogeneous Refinement using two identical initial models and two scrambled models. 776,527 particles from the highest resolution reconstruction were extracted with an unbinned box size of 288 pixels, and were subjected to Homogeneous Refinement followed by Non-Uniform Refinement. Particles were exported using csparc2star.py from the pyem v0.5 script package49, and an inclusion mask covering the 7TM domain of OR51E2 was generated using the Segger tool in UCSF ChimeraX v1.2550 and the mask.py tool in pyem v0.5. Particles and mask were imported into Relion v3.051 and sorted by several rounds of 3D classification without image alignment, where the number of classes and tau factor were allowed to vary. The resulting 204,438 particles were brought back into cryoSPARC and subjected to Non-Uniform Refinement. Finally, Local Refinement using an inclusion mask covering the 7TM domain was performed, using poses/shift gaussian priors with S.D. of rotational and shift magnitudes limited to 3° and 2 Å respectively.

Model building and refinement

Model building and refinement were carried out using an Alphafold244 predicted structure as a starting model, which was fitted into the OR51E2-Gs map using UCSF ChimeraX. A draft model was generated using ISOLDE52 and was further refined by iterations of real space refinement in Phenix v1.1953 and manual refinement in Coot v0.9.254. To identify a propionate binding site, we considered general overlap with other Class A GPCR binding pockets, general diversity of ORs within the region bounded by ECL2, TM5, and TM6, and a prior study that observed loss of activity of carboxylic acids for a R6x59 mutant for the OR51E2 ortholog OR51E142. With these constraints, we identified a non-proteinacious density near R2626x59 in sharpened maps of the OR51E2-Gs complex. The propionate model and rotamer library were generated with the PRODRG server55 and docked using Coot to place the carboxylic acid of propionate near R2626x59. The resulting model was extensively refined in Phenix. Final map-model validations were carried out using Molprobity v4.5 and EMRinger in Phenix.

Site Directed Mutagenesis

Generation of OR51E2 mutants was performed as described previously56. Forward and reverse primers coding for the mutation of interest were obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies. Two successive rounds of PCR using Phusion polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific: F-549L) were performed to amplify ORs with mutations. The first round of PCR generated two fragments, one containing the 5’ region upstream of the mutation site and the other the 3’ downstream region. The second PCR amplification joined these two fragments to produce a full ORF of the odorant receptor. PCR products with desired length were gel purified and cloned into the MluI and NotI sites of mammalian expression vector pCI (Promega) that contains rho-tag. Plasmids were purified using the Thomas Scientific (1158P42) miniprep kit with modified protocol including phenol-chloroform extraction before column purification.

cAMP signaling assays

The GloSensor cAMP assay (Promega) was used to determine real-time cAMP levels downstream of OR activation in HEK293T cells, as previously described57. HEK293T cells (authenticated by short tandem repeat profiling and tested negative for mycoplasma contamination) were cultured in Minimum Essential Media (MEM, Corning) supplemented by 10 % Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS,Gibco), 0.5 % Penicillin-Streptomycin (Gibco) and 0.5 % Amphotericin B (Gibco). Cultured HEK293T cells were plated the day before transfection at 1/10 of 100 % confluence from a 100 mm plate into 96-well plates coated with poly D lysine (Corning). For each 96-well plate, 10 μg pGloSensor-20F plasmid (Promega) and 75 μg of Rho-tagged OR in the pCI mammalian expression vector (Promega) were transfected 18 to 24 h before odorant stimulation using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen: 11668019) in MEM supplemented by 10% FBS. On stimulation day, plates were injected with 25 μl of GloSensor substrate (Promega) and incubated for 2 hours in the dark at room temperature and in a odor-free environment. Odorants were diluted to the desired concentration in CD293 media (Gibco) supplemented with copper (30 μM CuCl2, Sigma-Aldrich) and 2 mM L-glutamine (Gibco) and pH adjusted to 7.0 with a 150 mM solution of sodium hydroxide (Sigma-Aldrich). After injecting 25 μl of odorants in CD293 media into each well, GloSensor luminescence was immediately recorded for 20 cycles of monitoring over a total period of 30 minutes using a BMG Labtech POLARStar Optima plate reader. The resulting luminescence activity was normalized to a vector control lacking any OR, and the OR response was obtained by summing the response from all 20 cycles to determine an area under the curve (AUC). Dose-dependent responses of ORs were analyzed by fitting a least squares function to the data using GraphPrism 9.

Evaluating Cell Surface Expression

Flow-cytometry was used to evaluate cell surface expression of odorant receptors as described previously58. HEK293T cells were seeded onto 35-mm plates (Greiner Bio-One) with approximately 3.5 x 105 cells (25 % confluency). The cells were cultured overnight. After 18 to 24 hours, 1200 ng of ORs tagged with the first 20 amino acids of human rhodopsin (rho-tag) at the N-terminal ends59 in pCI (Promega) and 30 ng eGFP were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen: 11668019). 18 to 24 hours after transfection, the cells were detached and resuspended using Cell stripper (Corning) and then transferred into 5 mL round bottom polystyrene (PS) tubes (Falcon) on ice. The cells were spun down at 4°C and resuspended in phosphate buffered saline (PBS, Gibco) containing 15 mM NaN3 (Sigma-Aldrich) and 2% FBS (Gibco). They were stained with 1/400 (v/v) of primary antibody mouse anti rhodopsin clone 4D2 (Sigma-Aldrich: MABN15) and allowed to incubate for 30 minutes then washed with PBS containing 15 mM NaN3 and 2% FBS. The cells were spun again and then stained with 1/200 (v/v) of the phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated donkey anti-mouse F(ab’)2 fragment antibody (Jackson Immunologicals: 715-116-150) and allowed to incubate for 30 minutes in the dark. To label dead cells, 1/500 (v/v) of 7-Amino-actinomycin D (Calbiochem: 129935) was added. The cells were then immediately analyzed using a BD FACSCanto II flow cytometer with gating allowing for GFP positive, single, spherical, viable cells and the measured PE fluorescence intensities were analyzed and visualized using Flowjo v10.8.1. Normalizing the cell surface expression levels of the OR51E2 mutants was performed using wild-type OR51E2 which showed robust cell surface expression and empty plasmid pCI which demonstrated no detectable cell surface expression.

Molecular dynamics simulations

All MD simulations were performed using the GROMACS package60 (version 2021) with the CHARMM36m forcefield61 starting from the OR51E2 EM structure with and without propionate. The G protein was removed in all these simulations. The GPCR structures were prepared by Maestro (version 13.0.135, Schrödinger) “protein preparation wizard” module62. The missing side chains and hydrogen atoms were added. Furthermore, protein chain termini were capped with neutral acetyl and methylamide groups, and histidine protonated states were assigned, after which minimization was performed. The simulation box was created using CHARMM-GUI63. We used the PPM 2.0 function of OPM (Orientation of proteins in membranes)64 structure of OR51E2 for alignment of the transmembrane helices of protein structure and inserted into a 75% palmitoyl-oleoyl-phosphatidylcholine (POPC) / 25% Cholesteryl hemisuccinate deprotonated (CHSD) bilayer. The CHSDs were placed around the GPCR structure. TIP3P water model was used for solvation and 0.15 M potassium chloride ions were added for neutralization. The final system dimensions were about 85 Å × 85 Å × 115 Å. The system was minimized with position restraints (10 kcal/mol/Å2) on all heavy atoms of GPCR and ligand, followed by a 1 ns heating step which raise the temperature from 0K to 310K in NVT ensemble with Nosé-Hoover thermostat65. Then we performed a single long equilibration for lipid and solvent (1000 ns) in NPT ensemble. During the heating step and the long equilibration, position restraints were placed of 10 kcal/mol-Å2 applied on the receptor, propionate and POPC/CHSD for the first 1 ns. Later, the restraint on lipids was reduced from 5 kcal/mol-Å2 to 0 kcal/mol-Å2 in steps of 1 kcal with 5 ns of simulations per step. Then the POPC/CHSD were allowed to freely move during the rest of the long equilibration and the final snapshot was used as the initial conformation for equilibrating the protein and ligand. The position restraints were applied on the protein (backbone and side chain) and ligand starting at 5 kcal/mol-Å2 reducing to 0 kcal/mol-Å2 in steps of 1 kcal/mol-Å2 with 5 ns of simulation per step. The last snapshot of the equilibration step was used as initial conformation for five production runs with random seeds. This snapshot was also used as reference conformation for all the RMSD in coordinates. The pressure was controlled using Parrinello-Rahman method66 and the simulation system was coupled to 1 bar pressure bath. In all simulations LINCS algorithm is applied on all bonds and angles of waters with 2 fs time step used for integration. We used a cut-off of 12 Å for non-bond interaction and particle mesh Ewald method67 to treat long range L-J interaction. The MD snapshots were stored at every 20 ps interval. Trajectories were visualized with VMD v1.9.3 and PyMOL (Molecular Graphics System, Version 2.5 Schrödinger) and analyzed using the GROMACS package (version 2016/2019). All MD analysis was done on the aggregated trajectories for each system from the 5 runs (total 5 × 1 μs = 5 μs). Heatmaps and other MD related plots were generated with Graphpad Prism 9, whereas structural figures were generated using PyMOL. Summary of the statistics for all the properties (residue distances, rotamer angle and RMSD in coordinates) calculated from the aggregated MD simulation trajectories are presented in Supplementary Tables 1-6.

Molecular dynamics analysis

Ligand-receptor interactions

Contact frequencies were calculated using the “get_contacts” module (https://getcontacts.github.io/). The following interaction types were calculated between ligand and receptor: hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic and van der Waals interactions.

Calculation of Residue Distances

For the distance between two residues, we used gmx mindist (GROMACS package 2016/2019), which calculates the minimal distance between two atoms (e.g., sidechain, Cɑ, oxygens, nitrogens) of one of each residue over time. Distance analysis on the static structures were done using the measurement tool in PyMOL. Chosen atoms for distance calculations are described in each legend.

Rotamer Analysis of F250

For the rotamer analysis of residues of interest, we used the VMD tcl script “Calculate_dihedrals” (https://github.com/ajasja/calculate_dihedrals).

Representative Snapshots and Conformational Clustering

We show the final snapshot from every replicate simulation for each system (end of 1000ns simulation for each replicate) in Fig. 2f, 4i, Fig. 5b and Extended Data Fig. 9a,b and c as a single frame after 1000 ns of simulation time. We also performed an unbiased analysis of the structural changes using unsupervised clustering of simulation ensembles to examine the conformational heterogeneity of molecular dynamics simulations. We clustered the aggregated trajectories by applying the single linkage method on the transmembrane helix backbone atoms (gmx cluster, GROMACS package 2016/2019). An RMSD cutoff for clustering was set at 0.8 Å for propionate-bound WT OR51E2 simulations, 0.85 Å for no-ligand WT OR51E2 simulations and 0.85 Å for no-ligand Q18145x53D OR51E2 simulations. Resulting cluster populations are shown in Supplementary Table 7. The top populated cluster(s) from the clustering analysis (that covered >90% of the MD snapshots) were used to extract the representative snapshots for each conformational cluster shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. The structural changes observed in the last snapshot of each replicate are similar to the changes observed in the cluster representative structures as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 1. Thus an unbiased approach of analyzing the large scale MD simulation ensemble led to similar conclusions on the conformational changes deduced from the last snapshot.

Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD)

The gmx rms (GROMACS package 2016/2019) function was used to determine whether simulations were stable. We used the transmembrane backbone of OR51E2 by selecting the following residues: 23-50 (TM1), 57-86 (TM2), 93-126 (TM3), 137-164 (TM4), 191-226 (TM5), 230-264 (TM6), and 269-294 (TM7). As reference, we used the equilibrated MD structure of propionate bound, apo and Q18145x53D OR51E2. In order to assess the stability of the ligand in the binding pocket over time, the RMSD of propionate was calculated using the equilibrated MD structure of propionate-bound as a reference.

Generating OR51E2 mutant structural models, docking of C6 and C8 ligands and procedure for calculating the volume of the ligand binding pocket

The volume and surface area of the propionate binding pocket in OR51E2 was calculated using the Maestro SiteMap module68,69. Three structures were used for the volume calculation: 1) the OR51E2 cryo-EM structure bound to propionate, 2) the OR51E2-L158A model bound to hexanoate, 3) the OR51E2-F155A model bound to octanoate. To prepare the L158A and F155A structural models we used the Maestro mutation function to introduce the substitutions onto the cryo-EM structure of OR51E2; these models were then energy minimized using the ProteinPreparationWizard module using default parameters62. We then used Maestro Glide Docking70-72 to dock hexanoate and octanoate into the resulting models of OR51E2-L158A and OR51E2-F155A, respectively. We prepared the docking grid box for both OR51E2-L158A and OR51E2-F155A by defining a box centered at propionate, with a box length of 2.5 nm. Glide ligand docking was performed using XP precision and default parameters to yield a model for OR51E2-L158A bound to hexanoate and OR51E2-F155A bound to octanoate. To calculate ligand binding site volumes using the SiteMap module, we defined the ligand binding pocket as the residues within 6 Å around selected ligand (propionate/hexanoate/octanoate) with at least 15 site points (probes) per reported site. The grid size for the probes was set to 0.35 Å. Using this approach, the calculated volumes for wild-type OR51E2, OR51E2-L158A, and OR51E2-F155A were 31 Å3, 68 Å3, and 90 Å3 , respectively.

Phylogenetic tree

A phylogenetic tree of human Class A GPCRs was made by analyzing 677 full-length sequences. Of these, 390 sequences were from odorant receptors (56 Class I ORs and 334 Class II ORs), while 287 were from non-olfactory Class A GPCRs. Sequences were aligned with ClustalX/ClustalW 2.173 on Jalview 2.11.2.574. In the transmembrane regions, motifs conserved in all Class A GPCRs (TM1 - GN1x50; TM2 - LxxxD2x50, P2x59; TM3 - C3x25, DR3x50Y; TM4 - W4x50; TM5 - P5x50, Y5x58xxI5x61; TM7 - NP7x50xxY) were aligned. The case of TM6 is less obvious as ORs and non-olfactory GPCRs do not share a common amino acid motif in this helix. As proposed originally by de March et al.33, and supported by structural comparison of OR51E2 to β2AR, we aligned the CWLP6x50 motif of the non-olfactory class A GPCRs with the FYGx6x50 OR motif.

This structure based alignment is consistent with generic residue numbering provided in the latest iteration of GPCRdb75. For helix 8, we initially aligned the conserved residue F8x50 from non-olfactory Class A GPCRs and the corresponding residue hydrophobic residues V/I/M at position 8x50 in ORs (I8x50 in OR51E2). Further confidence in helix 8 alignment was gained by alignment of positions 8x46 (R in 84% of ORs), 8x47 (N in 84% of ORs), 8x48 (K in 69% of ORs) and 8x53 (A in 76% of ORs). Alignment of the intracellular and extracellular loops was also driven by conserved residues when available. For the intracellular loops (ICL), L12x50 in ICL1 and P34x50 in ICL2 are conserved between ORs and non-olfactory Class A GPCRs. ICL3 harbors significant variation in non-olfactory Class A GPCRs. In ORs, ICL3 is very short, so S6x26 (76% conserved in ORs) was used to align the intracellular end of TM6. For the extracellular loops (ECL), ECL1 does not contain residues common between ORs and non-olfactory class A GPCRs. ECL1 was therefore aligned by matching the conserved residue W23x50 in non-olfactory class A GPCR with the residues K/R/N, which are moderately conserved in ORs (52/15/9 %, respectively). This alignment was further supported with the more conserved position 23x52 (I in 94% of ORs) and 23x53 (S in 79% of ORs). For ECL2, we used C45x50, which is conserved between non-olfactory Class A GPCRs and ORs; additionally, the OR specific residues C45x40 and C45x60 were used to align OR sequences. Finally, ECL3 is not conserved within the class A GPCR family so only aligned to fit between TM6 and TM7. On R studio 202.07.01, alignment reading and matrix of distance between sequences (by sequence identity) calculation were performed with the Biostrings 2.66.076 and seqinr 4.2-2377 packages. Neighbor-Joining tree and tree visualization were realized with packages ape 5.6-278 and ggtree 3.6.279 and the tree is plotted unrooted with the daylight method.

Extended Data

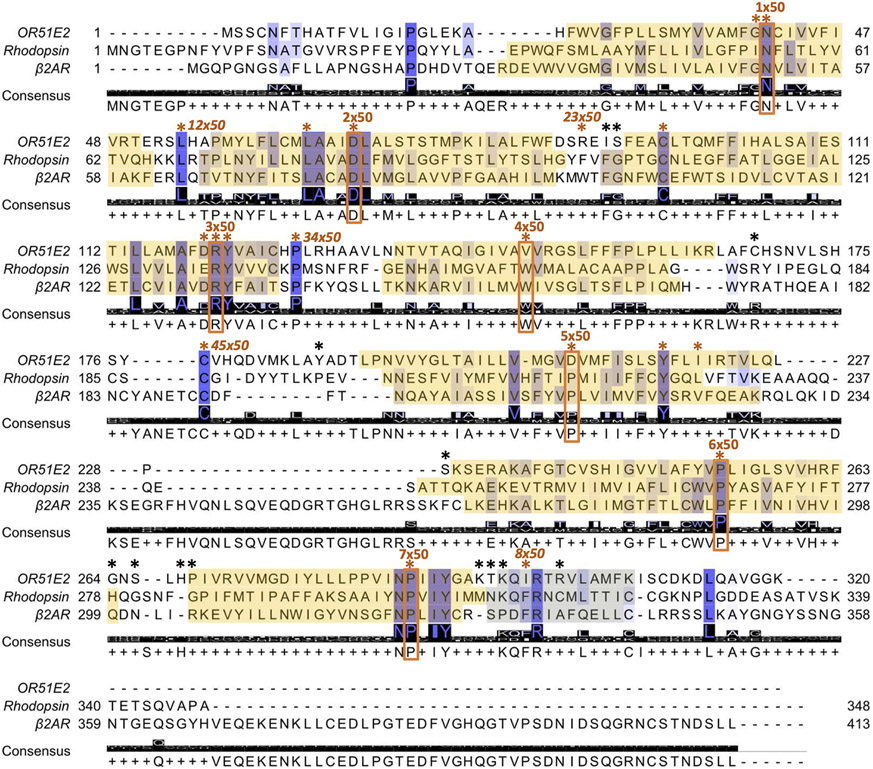

Extended Data Figure 1.

Alignment of OR51E2, rhodopsin and β2 adrenergic receptor (β2AR) amino acid sequences as described in part by de March et al.33 and implemented on GPCRdb75. Conservation is highlighted from low (white) to high (dark blue) and the consensus amino acid is shown. Transmembrane domains are boxed in yellow. The most conserved residue in class A GPCRs for each transmembrane domain is boxed and labeled in orange. Residues used to align OR and Class A GPCR sequences are highlighted by asterisks, which are colored orange when the residue is common to all Class A GPCRs and black when it is specific to ORs. The most conserved residues used for numbering of the intracellular and extracellular loops are also indicated in italic when available. Generic numbers follow the revised Ballesteros-Weinstein numbering for Class A GPCRs32,34

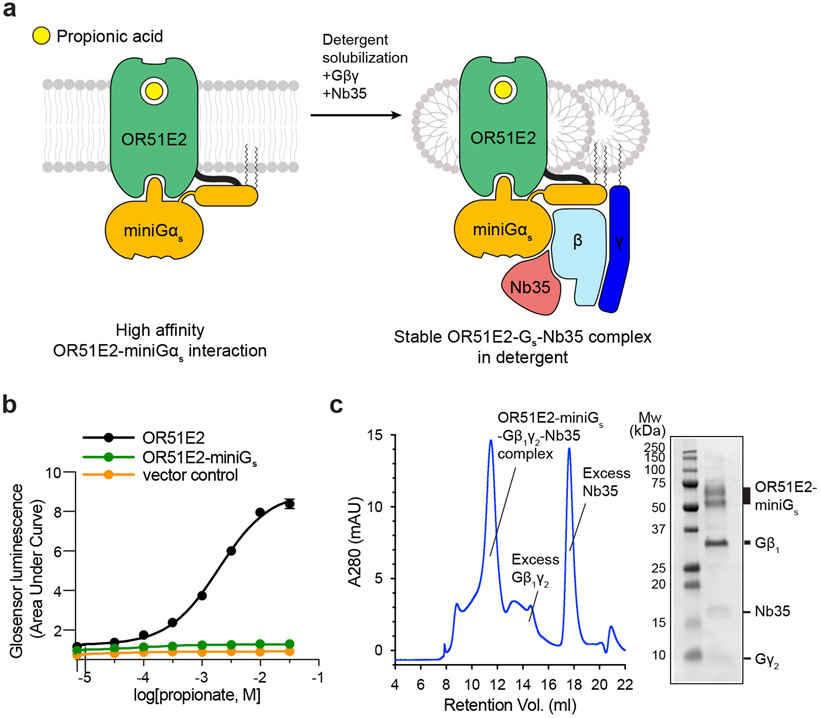

Extended Data Figure 2. Biochemical preparation of OR51E2-Gs complex bound to propionate.

a) Schematic outlining the strategy for stabilization and purification of the activated OR51E2-Gs complex bound to propionate. b) GloSensor cAMP assay demonstrating that fusion of miniGs to OR51E2 blocks activation of endogenous Gs in response to treatment with propionate, suggesting that miniGs couples to the OR51E2 transmembrane core. Data points are the mean of analytical replicates from a representative experiment. Error bars represent the standard deviation between replicates (n=4). c) Size-exclusion chromatogram of purified OR51E2-Gs-Nb35 complex used for structure determinations shown together with a representative SDS-PAGE gel analysis of the collected fraction containing the OR51E2-Gs-Nb35 complex. We observe two bands for OR51E2, likely due to heterogeneous glycosylation of the receptor N-terminus.

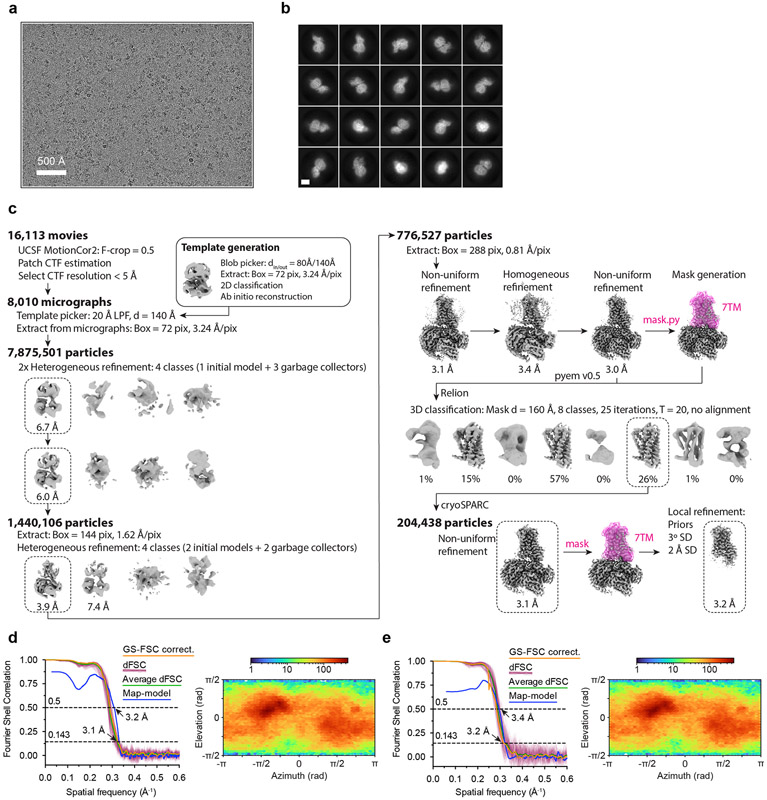

Extended Data Figure 3. Cryo-EM data processing for OR51E2-Gs.

a) A representative cryo-EM micrograph from the curated OR51E2-Gs dataset (n = 8,010) obtained from a Titan Krios microscope. b) A subset of highly populated, reference-free 2D-class averages are shown. Scale bar is 50 Å. c) Schematic showing the image processing workflow for OR51E1-Gs. Initial processing was performed using UCSF MotionCor2 and cryoSPARC. Particles were then transferred using the pyem script package49 to RELION for alignment-free 3D classification. Finally, particles were processed in cryoSPARC using the non-uniform and local refinement tools. Dashed boxes indicate selected classes, and 3D volumes of classes and refinements are shown along with global Gold-standard Fourier Shell Correlation (GSFSC) resolutions. d, e) Map validation for the OR51E2-Gs (d) globally refined, and (e) locally refined cryo-EM maps. GSFSC curves are calculated in cryoSPARC, and shown together with directional FSC (dFSC) curves generated with dfsc.0.0.1.py as previously described80. Map-model correlations calculated in the Phenix suite are also shown. Arrows indicate map and map-model resolution estimates at 0.143 and 0.5 correlation respectively. Euler angle distributions calculated in cryoSPARC are also provided for each map.

Extended Data Figure 4. Cryo-EM density and atomic model.

a) Orthogonal views of local resolution for the globally refined map of OR51E2-Gs calculated with the local resolution estimation tool in cryoSPARC. b) Close-up view showing the local resolution of the propionate binding site. c) Representative cryo-EM densities from the 3D reconstruction of OR51E2 from a sharpened, globally refined map of OR51E2-Gs at a map threshold of 0.635. Shown are the transmembrane helices and loop regions of OR51E2 as well as the C-terminal helix of miniGαs. d) Close-up view of cryo-EM density (yellow sticks and density) supporting propionate binding pose using a sharpened map locally refined around only the 7TM domain of OR51E2 at map threshold of 1.0.

Extended Data Figure 5. Interactions between propionate and OR51E2 in molecular dynamics simulations.

a) Minimum distance plot between R2626x59 and propionate from 5 independent runs at different velocities (top to bottom). Minimum distance was measured between guanidinium nitrogens of R2626x59 and oxygens of propionate. Thick trace represents smoothed values with an averaging window of 8 nanoseconds; thin trace represents unsmoothed values. b) Root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) values of production simulation runs for propionate calculated with reference to the equilibrated structure of OR51E2 prior to 1 μs production simulation from 5 independent runs at different velocities (top to bottom). c) Minimum distances (Ȧ) between ligand heavy atoms and residue side chain heavy atoms (hydrogen bond and van der Waals contacts combined) are shown in gray. Gray dashed arrows highlight the interactions made between a certain receptor residue and ligand atom(s). All distances are shown as means from n = 5 independent runs (at different velocities) each 1 μs long. Standard deviation of measurement for each of the residue-ligand distance are as follows; 0.03 Å (R2626x59), 0.10 Å(S2586x55), 0.16 Å (I2025x43), 0.12 Å (G1985x39), 0.23 Å (Q18145x53), 0.23 Å (H18045x52), 0.25 Å (L1584x60), and 0.14 Å (H1043x33).

Extended Data Figure 6. Conservation of residues within the odorant binding pocket.

a) View of propionate-contacting residues. Conservation weblogo of key residues in Class I (b) and Class II ORs (c). d) The percentage of receptors harboring a given amino acid at each position are shown for all human Class I and Class II ORs. OR51E2 residues at each position are indicated by a black box.

Extended Data Figure 7. Analysis of active state structure of OR51E2.

a) Structural comparison of G protein interaction for OR51E2 (green) and β2-adrenergic receptor (β2AR in blue, PDB code: 3SN6). b) Close-up views of intracellular loop 2 (ICL2) interaction with the Gαs subunit shown in surface representation. c) interactions between residues in ICL2 and the αN and α5 helices of the Gαs subunit. d) G protein-coupling region of OR51E2 is shown along with a weblogo (right) highlighting conservation of key residues for all human ORs. e) Residues that participate in the extended interaction hydrogen bonding network between TM3, TM4, TM5, and TM6 are conserved in human Class I ORs, but not in Class II ORs. f,g) The percentage of receptors harboring a given amino acid at each position are shown for all human Class I and Class II ORs at the G protein-coupling region and connector regions. OR51E2 residues at each position are indicated by a black box.

Extended Data Figure 8. OR51E2 molecular dynamics simulation trajectories.

a-c) Simulation trajectories for WT and Q18145x53D OR51E2 are shown in a-c. Five independent runs at different velocities are shown for each condition (top to bottom). a) F2506x47 χ1 angle over replicate simulations. b) Minimum distance between oxygen atoms of the hydroxyl groups in the side chains of S111 and Y2516x48 over replicate simulations. c) Minimum distance between R2626x59 sidechain atoms and G1985x39 mainchain atoms (excluding the hydrogens) for replicate simulations. d) Root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) values for TM backbone atoms in the transmembrane helices (see methods) calculated with reference to the equilibrated structure of the no ligand and propionate bound OR51E2 simulations, as well as for simulations of Q18145x53D OR51E2 from 5 independent MD simulation replicates (top to bottom). Thick traces represent smoothed values with an averaging window of 8 nanoseconds; thin traces represent unsmoothed values. e-f) Aggregate frequency distributions are shown for F2506x47 χ1 angle (e), minimum distance between heavy atoms of the hydroxyl groups of S1113x40 and Y2516x48 (f), and minimum distance between R2626x59 sidechain heavy atoms and G1985x39 main chain heavy atoms (excluding hydrogens) (g) using all five simulation replicates for each condition.

Extended Data Figure 9. Molecular dynamics snapshots of OR51E2.

a) Comparison of cryo-EM structure of propionate-bound OR51E2 with representative snapshots from simulations of WT OR51E2 with propionate, WT OR51E2 without ligand, and Q18145x53D OR51E2 without ligand. Notably, OR51E2 does not transition to the inactive conformation in any of these simulations. b) Close-up views of OR51E2 binding site and ECL3 region in the cryo-EM structure and simulations. In propionate-bound MD simulations of WT OR51E2, R2626x59 persistently forms an ionic interaction with propionate. In simulations of WT OR51E2 with propionate removed, R2626x59 is flexible. Introduction of Asp in position 45x53 (Q18145x53D) stabilizes R2626x59 in an active-like state by a direct ionic interaction. c) Close-up views of OR51E2 connector region shows increased flexibility of WT OR51E2 simulated without propionate. This flexibility is decreased for the Q18145x53D mutant. In a-c, displayed snapshots are the last 1000th ns snapshots from each simulation replicate. d and e) Molecular dynamics trajectories from representative simulations to highlight structural organization of connector region. d) Minimum distance between S1113x40 and Y2516x47 hydroxyl groups is comparable for Q18145x53D and propionate-bound WT OR51E2. e) Rotamer angle of F2506x47is comparable for Q18145x53D and propionate-bound WT OR51E2. Simulations were performed with or without propionate over the course of 1000 ns (see Extended Data Fig. 8 for replicates of simulation trajectories). Thick traces represent smoothed values with an averaging window of 8 nanoseconds; thin traces represent unsmoothed values.

Extended Data Figure 10. AlphaFold2 model of OR51E2.

a) AlphaFold2 predicted structure of OR51E2. The pLDDT confidence metric is shown highlighting relatively high confidence in the transmembrane regions and extracellular loops. b) AlphaFold2 predicted structure of unbound OR51E2 (gray) superimposed onto the experimentally determined structure of propionate-bound OR51E2 in the active state (green cartoon and yellow spheres). In the AlphaFold2 model, TM6 is inwardly displaced compared to the active structure. Closeup views of (c) the Connector region and (d) the G protein-coupling region are provided. e) Slice through surface representation of AlphaFold2 predicted OR51E2, suggests solvent accessibility of the ligand binding site in the inactive state.

Extended Data Table 1.

Cryo-EM data collection, refinement, and validation statistics.

| Propionate-bound | |

|---|---|

| OR51E2-Gs | |

| EMDB: Full map | EMD-28896 |

| EMDB: 7TM map | EMD-28900 |

| RCSB PDB: Model | 8F76 |

| Data collection | |

| Microscope | Thermo Scientific Krios G3i |

| Detector | Gatan K3 with Gatan |

| BioQuantum Energy filter | |

| Voltage (kV) | 300 |

| Magnification | 105,000 |

| Defocus range (μm) | −1.0 to −2.1 |

| Pixel size, physical (Å) | 0.81 |

| Total exposure (e−/Å2) | 50 |

| Frame exposure (e−/Å2/frame) | 0.833 |

| Images, number of | 16,113 |

| Frames/image, number of | 60 |

| Initial particles, number of | 7,875,501 |

| Final particles, number of | 204,438 |

| Symmetry imposed | C1 |

| Map sharpening, B factor (Å2) | |

| Full map | −140.2 |

| 7TM map | −162.8 |

| Map resolution, masked (Å) | |

| Full map | 3.1 |

| 7TM map | 3.2 |

| FSC threshold | 0.143 |

| Refinement | |

| Initial model used (AlphaFold code) | Q9H255 |

| Model resolution (Å) | 3.2 |

| FSC threshold | 0.5 |

| Model composition | |

| Chains | 6 |

| Non-hydrogen atoms | 8,176 |

| Protein residues | 1,038 |

| Ligands | 1 |

| B factors (Å2) | |

| Protein | 37.96 |

| Ligand | 38.56 |

| R.m.s. deviations | |

| Bond length (Å) | 0.005 |

| Bond angles (°) | 0.873 |

| Validation | |

| MolProbity score | 1.51 |

| Clash score | 5.64 |

| EMRinger score | 3.50 |

| Rotamer outliers (%) | 0 |

| Ramachandran plot | |

| Favored (%) | 96.76 |

| Allowed (%) | 3.24 |

| Disallowed (%) | 0.00 |

Extended Data Table 2.

Expression and pharmacodynamic constants for OR51E2 variants.

| Propionate activity in GloSensor cAMP assay | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface expression (mean) |

EC50 (mM, mean) |

pEC50 (−log M, mean ± S.E.M.) |

Emax (mean ± S.E.M.) |

Activity index (Emax * pEC50) |

|

| WT | 8,490 | 0.824 | 3.08 ± 0.053 | 3.24 ± 0.049 | 9.98 |

| H104A | 4,130 | 17.1 | 1.77 ± 0.77 | 1.74 ± 0.63 | 3.08 |

| S111A | 112 | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. |

| R121A | 192 | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. |

| R150A | 163 | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. |

| F155A | 8,700 | 12.3 | 1.91 ± 0.77 | 2.51 ± 0.099 | 4.79 |

| L158A | 5,250 | 1.6 | 2.8 ± 0.42 | 3.05 ± 0.43 | 8.53 |

| H180A | 4,570 | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. |

| Q181A | 7,340 | 12.4 | 1.91 ± 0.32 | 2.68 ± 0.49 | 5.11 |

| Q181D | 9,140 | 38.9 | 1.41 ± 0.12 | 2.59 ± 0.25 | 3.65 |

| Q181E | 8,750 | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. |

| Q181N | 4,910 | 3.9 | 2.41 ± 0.11 | 1.15 ± 0.016 | 2.77 |

| G198A | 5,960 | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. |

| I202A | 9,730 | 13.7 | 1.86 ± 0.050 | 2.25 ± 0.060 | 4.2 |

| D209A | 112 | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. |

| Y217A | 97.6 | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. |

| S242A | 10,300 | 0.615 | 3.21 ± 0.080 | 3.48 ± 0.071 | 11.2 |

| H243A | 260 | 0.459 | 3.34 ± 0.095 | 1.39 ± 0.015 | 4.64 |

| F250H | 2,420 | 4.12 | 2.39 ± 0.036 | 3.01 ± 0.066 | 10.2 |

| F250Y | 3,450 | 0.423 | 3.37 ± 0.096 | 2.68 ± 0.039 | 6.38 |

| Y251A | 114 | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. |

| Y251F | 1,500 | 4.72 | 2.33 ± 0.031 | 2.39 ± 0.029 | 5.56 |

| Y251H | 254 | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. |

| V252A | 6,610 | 1.01 | 3.00 ± 0.085 | 2.97 ± 0.076 | 8.91 |

| P253A | 1,460 | 5.53 | 2.26 ± 0.05 | 2.32 ± 0.047 | 5.23 |

| S258A | 7,230 | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. |

| R262A | 9,290 | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. |

| Y291A | 3,080 | 1.4 | 2.85 ± 0.042 | 2.50 ± 0.031 | 7.13 |

| mock | 49.4 | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. |

n.r. = no response (fit R2 < 0.90)

Extended Data Table 3.

Pharmacodynamic constants for fatty acid series at OR51E2 variants.

| EC50 (μM, mean) |

pEC50 (−log M, mean ± S.E.M.) |

Emax (mean ± S.E.M.) |

Activity index (Emax * pEC50) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT OR51E2 | ||||

| Acetate (C2) | 1,360 | 2.87 ± 0.05 | 4.35 ± 0.07 | 12.5 |

| Propionate (C3) | 1,404 | 2.85 ± 0.06 | 4.52 ± 0.09 | 12.9 |

| Butyrate (C4) | 8,737 | 2.06 ± 0.33 | 2.85 ± 0.90 | 5.9 |

| Pentanoate (C5) | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. |

| Hexanoate (C6) | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. |

| Heptanoate (C7) | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. |

| Octanoate (C8) | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. |

| Nonanoate (C9) | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. |

| Decanoate (C10) | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. |

| OR51E2 - F155A | ||||

| Acetate (C2) | 28,800 | 1.54 ± 0.16 | 1.94 ± 0.16 | 2.98 |

| Propionate (C3) | 9,130 | 2.04 ± 0.59 | 2.86 ± 0.081 | 5.83 |

| Butyrate (C4) | 5,260 | 2.28 ± 0.21 | 2.28 ± 0.33 | 5.19 |

| Pentanoate (C5) | 7,290 | 2.14 ± 0.24 | 2.96 ± 0.67 | 6.33 |

| Hexanoate (C6) | 543 | 3.27 ± 0.045 | 3.46 ± 0.065 | 11.3 |

| Heptanoate (C7) | 29.8 | 4.53 ± 0.020 | 3.99 ± 0.023 | 18.1 |

| Octanoate (C8) | 5.46 | 5.26 ± 0.028 | 4.56 ± 0.032 | 24.0 |

| Nonanoate (C9) | 12.1 | 4.92 ± 0.074 | 3.22 ± 0.051 | 15.8 |

| Decanoate (C10) | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. |

| OR51E2 - LI58A | ||||

| Acetate (C2) | 15,300 | 1.82 ± 0.087 | 2.14 ± 0.092 | 3.90 |

| Propionate (C3) | 1,300 | 2.89 ± 0.10 | 2.70 ± 0.081 | 7.80 |

| Butyrate (C4) | 2,890 | 2.54 ± 0.056 | 4.28 ± 0.22 | 10.9 |

| Pentanoate (C5) | 7,380 | 2.13 ± 0.13 | 4.38 ± 0.69 | 9.33 |

| Hexanoate (C6) | 859 | 3.07 ± 0.042 | 4.78 ± 0.12 | 14.7 |