ABSTRACT

Listeria monocytogenes is ubiquitously found in nature and can easily enter food-processing facilities due to contaminations of raw materials. Several countermeasures are used to combat contamination of food products, for instance, the use of disinfectants that contain quaternary ammonium compounds, such as benzalkonium chloride (BAC) and cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB). In this study, we assessed the potential of the commonly used wild-type strain EGD-e to adapt to BAC and CTAB under laboratory growth conditions. All BAC-tolerant suppressors exclusively carried mutations in fepR, encoding a TetR-like transcriptional regulator, or its promoter region, likely resulting in the overproduction of the efflux pump FepA. In contrast, CTAB tolerance was associated with mutations in sugR, which regulates the expression of the efflux pumps SugE1 and SugE2. L. monocytogenes strains lacking either FepA or SugE1/2 could still acquire tolerance toward BAC and CTAB. Genomic analysis revealed that the overproduction of the remaining efflux system could compensate for the deleted one, and even in the absence of both efflux systems, tolerant strains could be isolated, which all carried mutations in the diacylglycerol kinase-encoding gene lmo1753 (dgkB). DgkB converts diacylglycerol to phosphatidic acid, which is subsequently reused for the synthesis of phospholipids, suggesting that alterations in membrane composition could be the third adaptation mechanism.

IMPORTANCE

Survival and proliferation of Listeria monocytogenes in the food industry are ongoing concerns, and while there are various countermeasures to combat contamination of food products, the pathogen still successfully manages to withstand the harsh conditions present in food-processing facilities, resulting in reoccurring outbreaks, subsequent infection, and disease. To counteract the spread of L. monocytogenes, it is crucial to understand and elucidate the underlying mechanism that permits their successful evasion. We present various adaptation mechanisms of L. monocytogenes to withstand two important quaternary ammonium compounds.

KEYWORDS: Listeria, biocides, efflux pumps, QACs

INTRODUCTION

Listeria monocytogenes is one of the most successful foodborne pathogens worldwide. In high-risk groups such as immunocompromised individuals, the elderly, or pregnant women, an infection can cause invasive listeriosis, resulting in a hospitalization rate of ~95% and a fatality rate of ~13% (1, 2). Due to its ability to persist in a wide range of environmental stresses found in the food-processing industry, infection of L. monocytogenes is often associated with ingestion of contaminated ready-to-eat foods, such as ice cream (3), cheese (4), or processed meat (5). The pathogen poses a threat not only due to its ability to withstand common stresses such as extreme temperatures, pH, or high salt concentrations (up to 20%) but also due to its potential to adapt to biocides that are commonly found in disinfectants or sanitizers used in food-processing plants (6). The most frequently used antimicrobial component in disinfectants is a mixture of quaternary ammonium compounds (QACs) that are characterized by its ammonium ion linked to either an alkyl or aryl group. The chain length of QACs determines the antimicrobial potency; hence, a length of C14 or C16 is ideally used against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, respectively (7). L. monocytogenes strains with decreased sensitivity to QACs have been isolated from different locations around the world (8 – 14). This adaptation frequently resulted in cross-adaptation to other disinfectants and antimicrobial agents such as gentamycin, kanamycin, or ciprofloxacin (8, 9, 13, 15 – 18), emphasizing the importance of elucidating the underlying genetic basis. Two of the most extensively used QACs are benzalkonium chloride (BAC) and cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) (19, 20). While a variety of different mechanisms have been linked to increased tolerance toward BAC in isolated L. monocytogenes strains, to our knowledge, no previous research has investigated the underlying genetics of CTAB tolerance, which is often merely mentioned in association with cross-adaptation toward BAC (21 – 23).

Several factors have been identified in L. monocytogenes strains isolated from food-processing facilities that are associated with the presence or overexpression of efflux systems that aid in extruding the toxic compounds from the intracellular space. Determinants for BAC tolerance are often found on genetic elements and include genes encoding efflux pumps such as the qacH gene, located on the transposon Tn6188 (22, 23), the emrE gene, located on the genomic island LGI1 (24), or the bcrABC operon, which encodes the TetR-family transcriptional regulator BcrA and two small multidrug resistance (SMR) efflux pumps, BcrB and BcrC (25 – 27). The sugRE1E2 operon (sug operon) was analyzed as a chromosomal counterpart of bcrABC in the laboratory wild-type (wt) strain EGD-e and was correspondingly found to be important for tolerance toward QACs such as BAC and CTAB. The genes of the sug operon code for the TetR-family regulator SugR and the two SMR efflux pumps SugE1 and SugE2. The self-repressor SugR negatively regulates the operon in the absence of BAC, and accordingly, both SugE1 and SugE2 showed increased expression in the presence of the QAC (21). In addition, several studies showed increased expression of the major facilitator superfamily transporter MdrL in isolated as well as BAC-adapted L. monocytogenes strains, suggesting a direct contribution of this transporter to BAC tolerance (9, 28). However, a clean deletion of the transporter in EGD-e only resulted in a growth defect in the presence of BAC but no change in the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC). Additionally, its role in the export of cefotaxime and ethidium bromide (EtBr), which was previously described, could not be confirmed for the laboratory model strain (29, 30). It has to be mentioned that the tolerance in L. monocytogenes isolates from food-processing facilities or L. monocytogenes strains that were adapted to QAC in the laboratory was often transient and lost after passaging the strains in the absence of QAC stress. In contrast, the chromosomally encoded multidrug and toxic compound (MATE) efflux pump FepA was recently identified as the dominant, stable mode of tolerance for BAC in a screen of over 60 produce-associated L. monocytogenes and other Listeria species strains that were adapted to BAC by serially passaging them in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth containing increasing BAC concentrations (31). An independent study of biocide-adapted strains further supported these findings by showing that 94% of the adapted strains possessed mutations in the gene coding for the TetR-like transcriptional regulator FepR that was previously shown to repress its own expression and the expression of the efflux pump encoding gene fepA (32). The identified mutations in fepR were thus proposed to increase expression of FepA, resulting in enhanced tolerance toward BAC, as well as norfloxacin and ciprofloxacin (16).

Here we show that the laboratory wild-type strain EGD-e readily acquires stable mutations in the transcriptional regulator fepR and that the successional overexpression of the efflux pump FepA is responsible for the increased tolerance toward BAC, CTAB, ciprofloxacin, and gentamycin. We further successfully evolved suppressors in the presence of CTAB, which exclusively carried mutations in the TetR-like transcriptional regulator sugR, resulting in the overexpression of the SMR efflux pumps SugE1 and SugE2. L. monocytogenes strains lacking either fepA or sugE1/2 could still acquire tolerance toward CTAB and BAC by overexpressing the remaining efflux system. In addition, we could further evolve BAC- and CTAB-tolerant strains in the absence of the two major QAC efflux systems, which acquired mutations in a putative diacylglycerol kinase.

RESULTS

Isolation of BAC-tolerant L. monocytogenes strains

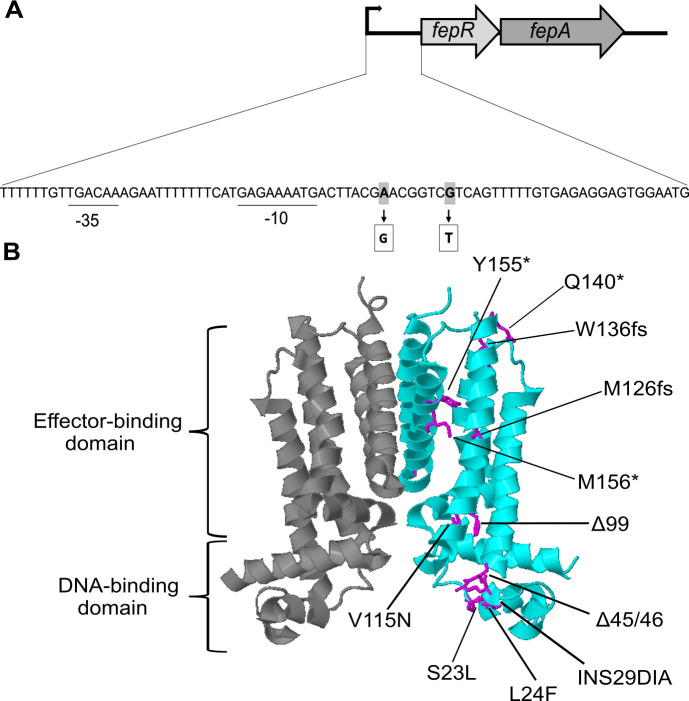

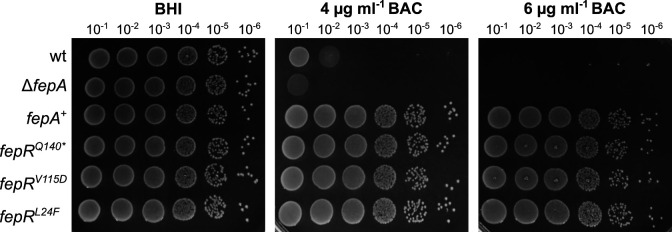

The L. monocytogenes wild-type strain EGD-e was propagated on BHI agar plates supplemented with BAC to obtain genetically adapted strains. The wild-type strain could still grow in the presence of 2-µg/mL BAC but was unable to grow on BHI agar plates containing higher BAC concentrations. However, single colonies appeared on plates containing 4- and 6-µg/mL BAC after 24 h, which likely acquired mutations to cope with the BAC stress. Since previous studies revealed that BAC-adapted L. monocytogenes isolates frequently mutate fepR, encoding the transcriptional regulator FepR, we first amplified the fepR gene and the fepR promoter region and analyzed the sequence using Sanger sequencing. Indeed, all adapted strains acquired mutations in fepR or its promoter region (Fig. 1). The transcriptional regulator FepR possesses a helix-turn-helix (HTH) domain between residues 23 and 42, which is required for DNA binding. In addition, a putative substrate-binding pocket was predicted to be located in the vicinity of residues 60, 100, 101, 104, 105, 119, 123, 126, 156, 159, 160, and 163 (32). We identified seven BAC-tolerant strains with point mutations, amino acid insertions, or deletions in the DNA-binding site (S23L, L24F, INS29DIA, and Δ45–46) and two with mutations or amino acid deletions in the putative substrate-binding site (V115D and Δ99). Nine BAC-tolerant strains had mutations leading to a frameshift or the production of a truncated FepR protein (M126fs, W137fs, N170fs, Q140*, Y155*, and G157*). We additionally isolated two suppressors that had base exchanges in the promoter region of the fepRA operon (G-27T and A-33G). All these mutations likely result in a reduced binding activity of the regulator or a decreased or abolished activity of FepR. For further analysis, we focused on the BAC-tolerant strains EGD-e fepRQ140* , EGD-e fepRV115D , and EGD-e fepRL24F . FepRQ140* is a truncated version of the FepR protein with an intact DNA-binding domain, which might still be able to bind to the fepRA promoter region and regulate the expression of the operon. Strains EGD-e fepRV115D and EGD-e fepRL24F produce FepR proteins with an amino acid substitution in the putative substrate-binding pocket and DNA-binding domain, respectively, that likely affect the substrate recognition or the binding of FepR to the fepRA promoter. The TetR-family transcriptional regulator FepR represses the expression of the MATE family efflux pump FepA (16). Hence, loss of function of the regulator subsequently leads to enhanced fepA expression. To verify that overproduction of FepA results in increased tolerance toward BAC, the isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible plasmid pIMK3-fepA was constructed and introduced into the wild-type strain (fepR+ ). In addition, a fepA deletion strain (ΔfepA) was constructed to determine its tolerance toward BAC. Indeed, drop dilution assays revealed that while the deletion of fepA led to slightly increased susceptibility toward BAC, overexpression of the transporter led to a significant increase in BAC tolerance, similar to that of the three selected fepR mutant strains (Fig. 2).

FIG 1.

Mutations in the transcriptional regulator encoding gene fepR. (A) Genetic organization of the fepRA operon in L. monocytogenes EGD-e. The fepRA operon is composed of genes coding for the transcriptional regulator FepR and the MATE efflux pump FepA. The predicted promoter region is displayed along with the −10 and −35 regions (underlined). The base exchanges of the two suppressors in the fepR promoter are shown in gray. (B) The dimeric protein structure of the transcriptional regulator FepR (PDB: 5ZTC) was modified using Geneious Prime v.2021.0.1 (Biomatters Ltd., New Zealand). Single monomers are depicted in dark gray and cyan. Mutated amino acids are shown in magenta. Mutations leading to a stop codon are indicated with an asterisk, and frameshift mutations are abbreviated with an fs. Amino acid insertions are indicated by INS and deletion by the Δ symbol.

FIG 2.

Increased BAC tolerance of fepR suppressors. Drop dilution assays of L. monocytogenes strains EGD-e (wt), the fepA deletion strain LJR261 (ΔfepA), a wt strain containing the IPTG-inducible pIMK3-fepA plasmid LJR265 (fepA +), and the suppressor mutants LJR208 (fepRQ140* ), LJR211 (fepRV115D ), and LJR218 (fepRL24F ). Cells were propagated on BHI plates or BHI plates containing 4- and 6-µg/mL BAC, and plates were incubated overnight at 37°C. Plates were supplemented with 1-mM IPTG to induce expression of FepA in the fepA + strain. A representative image of at least three biological replicates is shown.

Mutations in FepR alter DNA binding

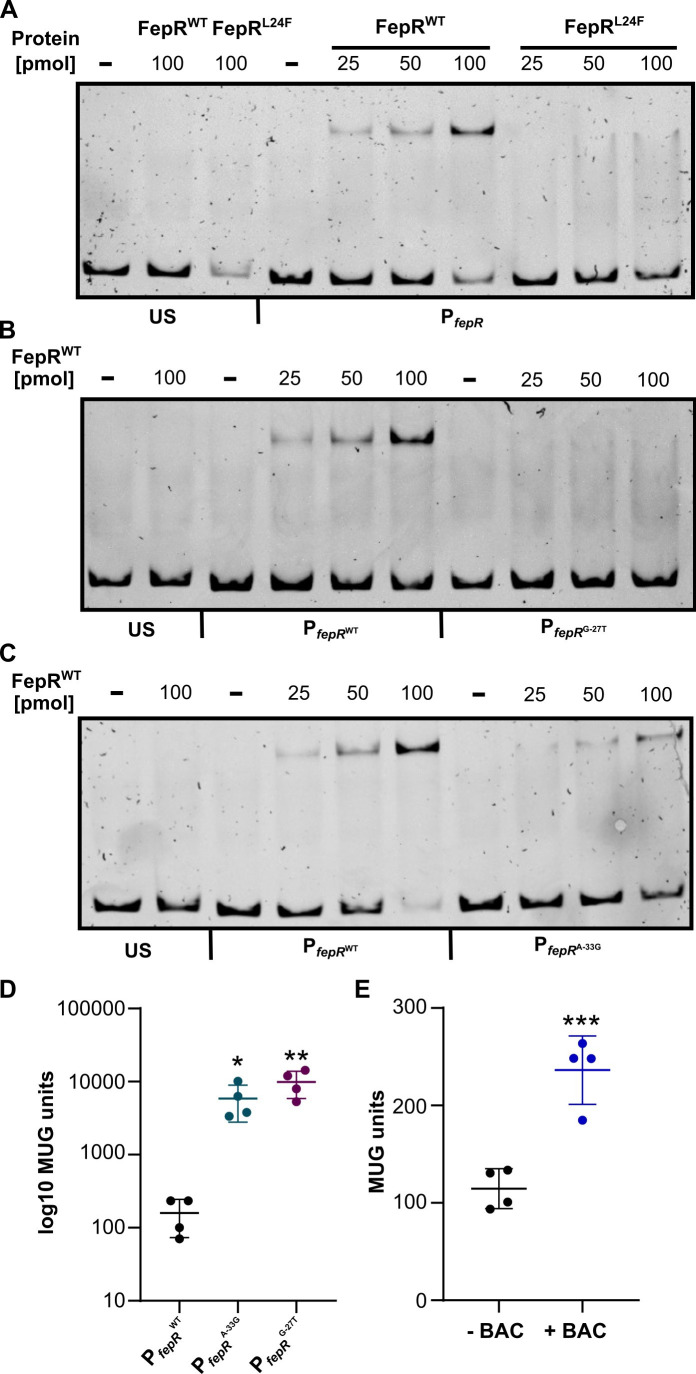

According to structure predictions, the HTH motif of FepR, which is required for the interaction with DNA, is located between residues 23 and 42. Hence, we assumed that the mutation L24F has a negative effect on DNA binding by FepR. Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) were performed to assess if DNA binding of FepRL24F to the promoter region of the fepRA operon is altered. Indeed, in the concentration range used, no DNA-protein complexes could be detected for FepRL24F in comparison to FepRwt (Fig. 3A), indicating that the mutation L24F decreased DNA-binding affinity of FepR. Binding of the two proteins to an unspecific DNA sequence from within the operon was not observed (Fig. 3A). We then tested the binding affinity of FepRwt to the mutated promoter regions of the fepRA operon of the BAC-tolerant strains EGD-e PfepR G-27T and EGD-e PfepR A-33G . The base exchange from G to T 27 bp upstream of the start codon completely abolished binding of FepRwt at the tested protein concentrations (Fig. 3B). Likewise, decreased binding affinity of FepRwt was observed when the promoter region contained an A to G substitution 33 bp before the start codon, but to a lesser extent then the G-27T promoter mutation (Fig. 3C). We further compared the promoter activity of the wild-type and mutated fepR promoters and determined their response to subinhibitory concentrations of BAC using β-galactosidase activity assays. Both PfepR G-27T and PfepR A-33G showed significantly increased promoter activity in comparison to the wild-type promoter (Fig. 3D). PfepR G-27T hereby showed a higher activity than PfepR A-33G, which is in accordance with the difference in FepR-binding capability (Fig. 3B through D). Increased β-galactosidase activity could be measured when EGD-e PfepR-lacZ was grown in the presence of BAC (Fig. 3E), indicating that the expression of fepRA is slightly induced in response to BAC.

FIG 3.

Interaction of FepR with the fepRA promoter and PfepR promoter activity. (A) Increasing concentrations of recombinant His-FepRwt (lanes 5–7) or His-FepRL24F (lanes 8–10) were incubated with a 150-bp fragment containing the promoter of the fepRA operon. (B) Increasing concentrations of FepRwt were incubated with either the wild-type promoter region (PfepR wt ) or the promoter region with a base exchange from G to T 27 bp upstream of the ATG (PfepR G-27T ). (C) Incubation of FepRwt with either PfepR wt or the promoter region with a base exchange from A to G 33 bp upstream of the ATG (PfepR A-33G ). A short DNA sequence amplified from within the operon was incubated with 100 pmol FepRwt or FepRL24F and was included on each gel to exclude US binding of the two proteins. Reactions without protein were used as an additional control (−). (D and E) Promoter activity assays. (D) EGD-e pPL3e-PfepR wt-lacZ, EGD-e pPL3e-PfepR A-33G-lacZ, and EGD-e pPL3e-PfepR G-27T-lacZ were grown for 5 h in BHI medium, and the promoter activity was determined by β-galactosidase activity assays as described in Materials and Methods. Log10 of the MUG units is plotted to visualize the values obtained for EGD-e pPL3e-PfepR wt-lacZ. (E) Bacteria from a midlogarithmic culture of strain EGD-e pPL3e-PfepR wt-lacZ were grown for 2 h in the presence or absence of 2.5 µg/mL BAC. The PfepR promoter activity was determined by β-galactosidase activity assays as described in Materials and Methods. For statistical analysis, one-way analysis of variance coupled with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test was performed (* P ≤ 0.05; ** P ≤ 0.01; *** P ≤ 0.001). MUG, 4-methyl-umbelliferyl-β-D-galactopyranoside; US, unspecific.

Ethidium bromide is a substrate for the efflux pump FepA

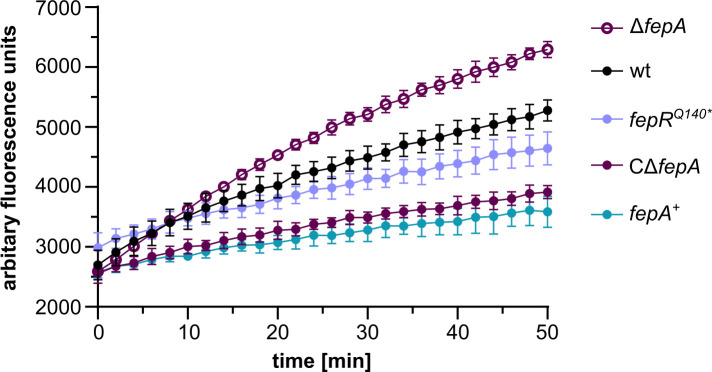

Previous work has shown that the deletion of fepR resulted in an increased ethidium bromide resistance (16). To assess whether this resistance can be explained by the overproduction of FepA, an EtBr accumulation assay was performed with the wild-type, ΔfepA, fepA+ , the EGD-e fepRQ140* suppressor mutant, and a ΔfepA complementation strain. This assay revealed that a strain lacking the efflux pump FepA accumulated more EtBr as the wild-type strain (Fig. 4). In contrast, the more gradual slope of the EGD-e fepRQ140* suppressor indicates a slightly reduced accumulation. Similarly, a significantly reduced accumulation of EtBr was observed for the ΔfepA complementation strain and the fepA overexpression strain (fepA+ ) (Fig. 4), suggesting that FepA is able to export EtBr.

FIG 4.

EtBr accumulation assay. Accumulation of EtBr by L. monocytogenes EGD-e (wt), the fepRQ140* suppressor strain (LJR208), a ΔfepA mutant strain (LJR261), a CΔfepA, and a fepA overexpression strain (fepA +) was measured at an excitation wavelength of 500 nm and an emission wavelength of 580 nm for 50 min. The average values and standard deviations of three independent experiments are depicted.

FepA contributes to cross-resistance and tolerance toward cetyltrimethylammonium bromide

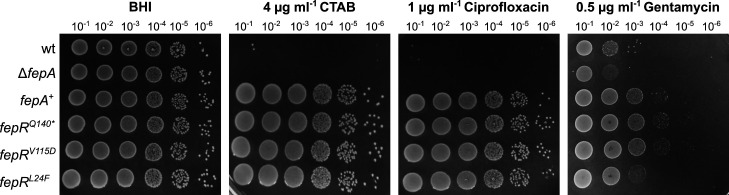

The MATE efflux pump FepA has been previously associated with fluoroquinolone resistance. We thus wondered whether the BAC-tolerant strains are also more tolerant toward other antimicrobials such as the fluoroquinolone antibiotic ciprofloxacin, the aminoglycoside gentamycin, the cephalosporin cefuroxime, or the surfactant CTAB. Indeed, growth experiments revealed that the mutations in fepR, and hence overexpression of FepA, additionally conferred resistance toward ciprofloxacin and gentamycin and increased tolerance toward CTAB (Fig. 5) but not toward cefuroxime (data not shown). Similar results were obtained for the fepA+ strain, which artificially overproduces FepA (Fig. 5). Interestingly, we observed suppressor formation in the wild-type strain on plates containing CTAB, which has not been described so far.

FIG 5.

Cross-resistance of fepR mutant strains. Drop dilution assays of L. monocytogenes strains EGD-e (wt), the fepA deletion strain LJR261 (ΔfepA), a wt strain containing the IPTG-inducible pIMK3-fepA plasmid LJR265 (fepA +), and the suppressor mutants LJR208 (fepRQ140* ), LJR211 (fepRV115D ), and LJR218 (fepRL24F ). Cells were propagated on BHI plates or BHI plates containing 4-µg/mL CTAB, 1-µg/mL ciprofloxacin, or 0.5-µg/mL gentamycin. All plates were supplemented with 1-mM IPTG to induce expression of fepA in the fepA + strain. Plates were incubated overnight at 37°C. A representative image of at least three biological replicates is shown.

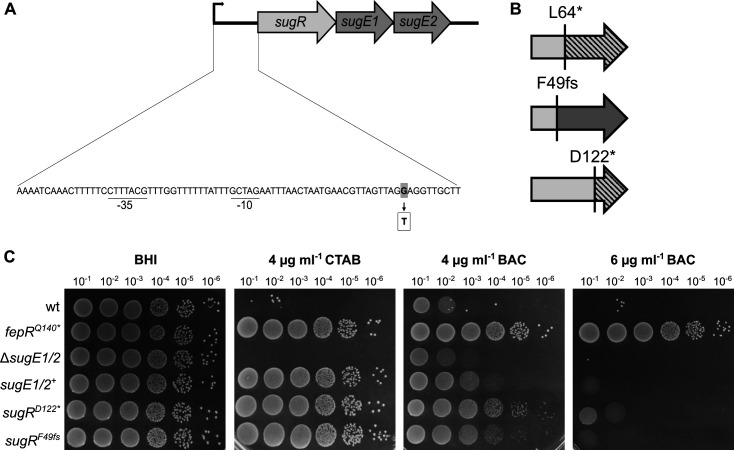

Mutations in sugR confer resistance toward CTAB

For the isolation of CTAB-tolerant L. monocytogenes strains, the wild-type strain EGD-e was propagated onto BHI plates containing varying CTAB concentrations. Growth of the wild-type was diminished at concentrations above 1-µg/mL CTAB, and CTAB-tolerant strains were isolated in the presence of 2 and 4 µg/mL of CTAB. The genome sequence of two and seven of the CTAB-tolerant strains isolated from 2 and 4 µg/mL, respectively, was determined by whole-genome sequencing (WGS) to identify the underlying mutations. All of these strains solely carried mutations in the coding or promoter region of sugR, encoding a TetR-family transcriptional regulator (Fig. 6A and B). Four of the CTAB-tolerant strains had a 1-bp deletion leading to a frameshift after phenylalanine at position 49; four strains carried point mutations leading to a premature stop after 64 or 122 amino acids; and one strain carried a point mutation in the sugR promoter region. SugR is encoded in an operon together with sugE1 and sugE2, coding for two SMR efflux pumps. Deletion of the regulator sugR leads to the overexpression of SugE1 and SugE2 and by this to an increased tolerance toward QACs, including BAC and CTAB (21). However, to our knowledge, this is the first time that strains were isolated that acquired mutations in sugR under CTAB treatment. To assess the impact of SugE1 and SugE2 on BAC and CTAB tolerance, drop dilution assays were performed with a strain lacking both efflux pumps, a sugE1/2 overexpression strain (sugE1/2 +), the two CTAB-tolerant strains EGD-e sugRD122* and EGD-e sugRF49fs , as well as the wild-type strain. The BAC-tolerant strain EGD-e fepR Q140* was included as a control. sugE1/2 +, as well as the two CTAB-tolerant strains, showed a growth advantage on BHI plates supplemented with CTAB and BAC in comparison to the wild-type and ΔsugE1/2 deletion strains. However, EGD-e sugRD122* and EGD-e sugRF49fs were unstable in the presence of BAC as they readily formed suppressors, while the growth of EGD-e fepRQ140* was not affected by BAC (Fig. 6C). Our results, therefore, indicate that FepA and SugE1/2 are the dominant efflux pumps for BAC and CTAB, respectively. In comparison to the fepR-associated suppressors, no cross-resistance toward gentamycin and ciprofloxacin was observed in association with the overproduction of SugE1/2 (Supplementary Material 1).

FIG 6.

Acquired CTAB tolerance due to mutations in sugR. (A) Genetic organization of the sug operon in L. monocytogenes EGD-e with the predicted promoter region including the −10 and −35 regions (underlined). The sug operon contains genes coding for the transcriptional regulator SugR and the two SMR efflux pumps SugE1 and SugE2. Base exchange from one of the suppressors is displayed in gray (adapted from Jiang et al. [21]). (B) Mutations in the sugR gene (depicted in light gray) in strains isolated in the presence of CTAB. Dark gray color depicts part of the gene/protein that is affected by the frameshift. The deleted parts of the protein are shown as dashed lines. (C) Drop dilution assays of L. monocytogenes strains EGD-e (wt), a sugE1/2 deletion strain (ΔsugE1/2), a wt strain containing the IPTG-inducible pIMK3-sugE1/2 plasmid LJR301 (sugE1/2 +), and the suppressor mutants sugRD122* (LJR248) and sugRF49fs* (LJR258). The fepRQ140* suppressor mutant (LJR208) was used as a control. Cells were propagated on BHI plates or BHI plates containing 4-µg/mL CTAB and 4- and 6-µg/mL BAC. All plates were supplemented with 1-mM IPTG to induce the expression of sugE1/2 in the sugE1/E2 + strain. Plates were incubated overnight at 37°C. A representative image of at least three biological replicates is shown.

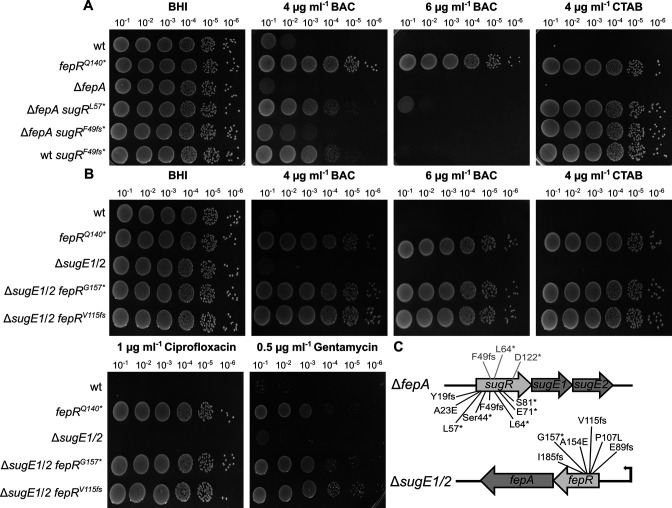

SugE1/2 and FepA can partially compensate for each other in the presence of biocide stress

In an attempt to identify further tolerance mechanisms, the two deletion strains ΔfepA and ΔsugE1/2 were again adapted to BAC and CTAB. ΔsugE1/2 readily formed suppressors in the presence of 6-µg/mL BAC and 4-µg/mL CTAB within a day. The ΔfepA strain evolved suppressors in the presence of 4- and 6-µg/mL CTAB within a day, while it took 2 d to isolate BAC-tolerant suppressors (5-µg/mL BAC). To assess if overproduction of FepA and SugE1/2 can compensate for the lack of SugE1/2 or FepA, respectively, isolated suppressors were screened for mutations in the respective transcriptional regulator. Indeed, all isolated ΔsugE1/2 suppressors carried mutations in the fepR gene, regardless of the selective pressure (Fig. 7C). Similarly, all ΔfepA isolates had mutations in the sugR gene, most of which led to either a premature stop or a frameshift. A similar growth behavior could be observed for the ΔfepA and ΔsugE1/2 suppressors as compared to the BAC- and CTAB-tolerant wild-type strains (Fig. 2, 5, and 7A and B). ΔfepA sugRL57* and ΔfepA sugRF49fs showed enhanced tolerance in presence of 4-µg/mL CTAB and 4-µg/mL BAC, while only minor growth was observed in presence of 6-µg/mL BAC. Interestingly, the wild-type strain harbouring the F49fs mutation in sugR seems to be slightly more tolerant toward BAC than the corresponding ΔfepA strain (Fig. 7A). In addition, no cross-resistance toward ciprofloxacin and gentamycin was observed for ΔfepA sugRL57* and ΔfepA sugRF49fs (Supplementary Material 1). In contrast, ΔsugE1/2 fepRG157* and ΔsugE1/2 fepRV115fs showed similar growth as the wild-type strain carrying the fepRQ140* mutation, where not only increased tolerance toward BAC and CTAB was observed but also cross-resistance toward ciprofloxacin and gentamycin (Fig. 7B). These results indicate that FepA and SugE1/2 can at least partially compensate for each other.

FIG 7.

SugE1/2 and FepA can partially compensate for each other in the presence of biocide stress. (A) Drop dilution assays of L. monocytogenes strains EGD-e (wt), the fepA deletion strain (ΔfepA), and the suppressor mutants ΔfepA sugRL57 *(LJR280), ΔfepA sugRF49fs (LJR267), and wt sugRF49fs (LJR258). The fepRQ140* suppressor mutant (LJR208) was used as a control. Cells were propagated on BHI plates or BHI plates containing 4- and 6-µg/mL BAC or 4 µg mL−1 CTAB and incubated overnight at 37°C. (B) Drop dilution assays of L. monocytogenes strains EGD-e (wt), the sugE1/2 deletion strain (ΔsugE1/2), and the suppressor mutants ΔsugE1/2 fepRG157* (LJR270) and ΔsugE1/2 fepRV115fs (LJR276), isolated on CTAB and BAC, respectively. The fepRQ140* suppressor mutant was used as a control. Cells were propagated on BHI plates or BHI plates supplemented with 4- and 6-µg/mL BAC, 4-µg/mL CTAB, 1-µg/mL ciprofloxacin, or 0.5-µg/mL gentamycin and were incubated overnight at 37°C. A representative image of at least three biological replicates is shown. (C) Acquired sugR and fepR mutations in the ΔfepA or ΔsugE1/2 background, respectively. The mutations that were previously identified in the wild-type background are depicted in gray.

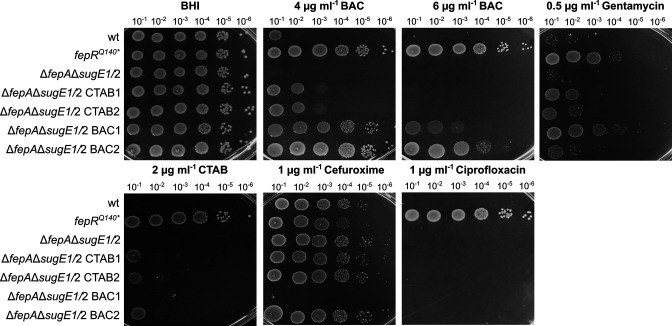

Strains lacking the two major QAC efflux systems can still acquire tolerance

To assess whether L. monocytogenes possesses a third mechanism to adapt to QACs, the ΔfepA ΔsugE1/2 double deletion strain was constructed and propagated in the presence of BAC and CTAB. Interestingly, no suppressor formation was observed on BHI plates containing 6-µg/mL BAC or 4-µg/mL CTAB, which were previously used to isolate BAC- und CTAB-tolerant strains, likely due to the absence of two important efflux systems. However, the ΔfepAΔsugE1/2 deletion strain could still adapt to 5-µg/mL BAC and 2-µg/mL CTAB. Genomic alterations for two BAC-tolerant and two CTAB-tolerant strains were determined by WGS. Interestingly, all tolerant isolates acquired mutations in lmo1753 encoding a putative diacylglycerol kinase and Sanger sequencing of additional mutants likewise identified mutations in lmo1753. The phenotype of the suppressors slightly varied in the presence of different stresses. The two CTAB-tolerant strains ΔfepAΔsugE1/2 CTAB1 and ΔfepAΔsugE1/2 CTAB2 showed only slightly increased tolerance on plates containing 2-µg/mL CTAB and 4-µg/mL BAC. In contrast, the BAC-tolerant strain ΔfepAΔsugE1/2 BAC2 could grow to some extent in the presence of CTAB and showed enhanced growth even in the presence of up to 6-µg/mL BAC as compared to the wild-type strain and the ΔfepAΔsugE1/2 deletion strain (Fig. 8). Apart from the mutation in lmo1753, this suppressor carried a mutation in the promoter region of lmo1682, encoding a putative multidrug efflux pump whose overexpression is likely responsible for the increased BAC tolerance. The BAC-tolerant strain ΔfepAΔsugE1/2 BAC1 also showed an enhanced tolerance toward BAC as compared with the ΔfepAΔsugE1/2 deletion strain; however, no growth advantage could be observed on BHI plates containing CTAB (Fig. 8). Interestingly, ΔfepAΔsugE1/2 BAC1 was more sensitive toward the antibiotic cefuroxime in comparison with the parental and wild-type strain, as well as an increased tolerance to gentamycin similar to EGD-e fepRQ140* (Fig. 8). Remarkably, we could identify neither additional mutations for ΔfepAΔsugE1/2 BAC1 apart from the mutation in lmo1753, which is identical to the mutation in ΔfepA ΔsugE1/2 CTAB1 and CTAB2, nor indications of gene amplification events that could explain the distinct phenotype. No cross-adaptation toward ciprofloxacin was observed for any of the ΔfepAΔsugE1/2 suppressors (Fig. 8).

FIG 8.

QAC tolerance of the ΔfepAΔsugE1/2 deletion strain. Drop dilution assays of L. monocytogenes strains EGD-e (wt); the fepA sugE1/2 deletion strain (ΔfepAΔsugE1/2); the two suppressor mutants that were isolated in the presence of CTAB, LJR327 (ΔfepAΔsugE1/2 lmo1753K19fs , short CTAB1) and LJR328 (ΔfepAΔsugE1/2 lmo1753K19fs , short CTAB2); and the two suppressor mutants that were isolated in the presence of BAC, LJR326 (ΔfepAΔsugE1/2 lmo1753K19fs , short BAC1) and LJR330 (ΔfepAΔsugE1/2 lmo1753V225fs Plmo1682 G-37A , short BAC2). A representative image of at least three biological replicates is shown.

DISCUSSION

Survival and proliferation of L. monocytogenes in the food industry is an ongoing concern, and while there are various countermeasures to combat the contamination of food products, such as osmotic stress, extreme temperatures, or the use of disinfectants, the pathogen still successfully manages to withstand the harsh conditions present in food-processing facilities, resulting in reoccurring outbreaks. To counteract the spread of L. monocytogenes, it is crucial to understand and elucidate the underlying mechanism that permits their successful evasion. Outbreaks are often associated with strains that tolerate below working concentrations of QACs, such as BAC or CTAB, the most commonly used active agents in disinfectants (33). In this study, we assessed the ability of the laboratory wild-type strain EGD-e to adapt to low levels of BAC and CTAB under laboratory growth conditions. Since previous studies have focused on the analyses of L. monocytogenes isolates, which exhibit a high frequency of genomic variations, our findings using the laboratory model strain represent a more generalized assessment. While previously isolated strains often merely acquired a transient tolerance toward QACs that was lost after passaging of the strains in the absence of the stress, potentially due to overexpression of efflux pumps, our strains readily formed stable suppressors that allowed growth in the presence of BAC and CTAB. Treatments with subinhibitory levels of QACs and other antibiotics induces the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can subsequently attack the bacterial DNA, resulting in either single- or double-strand breaks or mutations. ROS-induced mutations often cause an overexpression of efflux systems, thereby enhancing the tolerance toward the respective antimicrobial, which potentially results in additional cross-resistance (34 – 36). It is currently unknown whether the genomic alterations in our suppressors were caused by DNA damage due to oxidative stress induced by QACs or whether they were acquired spontaneously. L. monocytogenes possesses more than 200 efflux pumps, several of which are overproduced in response to QAC stress, such as MdrL or Lde (29, 30, 37, 38). If the mutations of our BAC- and CTAB-tolerant isolates would be caused by oxidative stress, we would assume to find more than one mutated QAC-tolerance determinant-encoding gene. Further experiments are required to verify this hypothesis.

In our study, BAC-tolerant L. monocytogenes strains exclusively carried mutations in fepR, which encodes a transcriptional regulator. These findings are in accordance with previous studies, which focussed on serially adapted isolated L. monocytogenes and Listeria species strains that were exposed to BAC or ciprofloxacin stress and likewise found that the majority of strains acquired mutations in fepR (18, 31, 32). FepR has just recently been identified as one important genome-encoded determinant for BAC-tolerance (32). Due to this, there are currently no data available on the prevalence of fepR mutations in BAC-tolerant L. monocytogenes isolates from the environment or food industry. However, for several L. monocytogenes isolates, the BAC-tolerance mechanism has not yet been identified or is not fully understood (8, 13, 14, 27, 39, 40). FepR is a TetR-like transcriptional regulator that negatively regulates the fepRA operon, which encodes the regulator itself as well as the MATE family efflux pump FepA (16). Strains that carried a mutation in fepR, as well as strains that artificially overexpressed the efflux pump FepA, exhibited increased tolerance not only toward BAC but also toward CTAB, ciprofloxacin, and gentamycin, indicating that extrusion by the transporter is rather unspecific. This observation further supports the previous hypothesis that de-repression of fepA is the reason for the observed QAC tolerance (16, 18, 31, 32). We further substantiated this hypothesis by showing that a mutation in the DNA-binding domain of FepR resulted in decreased binding to the promoter of the fepRA operon in comparison with the wild-type FepR protein. Likewise, mutations in the fepRA promoter region resulted in reduced binding of the wild-type FepR and, thus, to increased promoter activity. This enhanced promoter activity could then result in an enhanced production of FepA and subsequent export of BAC. Interestingly, we did not identify any mutations in either of the two chromosomally located efflux pumps, MdrL or Lde, which were previously described to be involved in QAC adaptation and whose expression is commonly upregulated in tolerant L. monocytogenes isolates (29, 30, 37, 38). This was the case even in the absence of FepA and/or SugE1/2, suggesting that neither plays a significant role in BAC or CTAB tolerance under the tested conditions. Altogether, we can conclude that the acquisition of mutations in fepR and the associated elevation of FepA levels and activity are the dominant modes of tolerance toward BAC in the EGD-e wild-type strain. In contrast, suppressors isolated in the presence of CTAB stress solely acquired mutations in the sugR gene, coding for a different transcriptional regulator. Unexpectedly, none of the isolated CTAB suppressors carried mutations in the fepR gene. SugR is involved in the repression of the two SMR efflux pumps SugE1 and SugE2, which were previously shown to confer tolerance toward QACs such as BAC, CTAB, or didecyldimethylammonium chloride in L. monocytogenes. Accordingly, expression of the efflux system was shown to be induced in the presence of BAC, suggesting that BAC can inhibit the SugR-dependent repression of sugE1/2 (21). Similarly to previous findings, the overexpression of SugE1/2 either due to mutations in its repressor or artificial induction did not result in any further cross-adaptation in contrast to suppressors with fepR mutations (16, 18, 21). Cross-resistance was also observed for Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Escherichia coli isolates after BAC adaptation. While P. aeruginosa isolates acquired tolerance toward polymyxin B and other antibiotics, BAC-adapted E. coli strains exhibited increased MIC for ampicillin and/or ciprofloxacin (41, 42). This raises the question, if CTAB should be used more frequently in commercial disinfectants than BAC to prevent the emergence of multiresistant strains. We also found that although both efflux systems could compensate for the loss of the other, overexpression of FepA results in a higher BAC tolerance than overexpression of SugE1/2, suggesting that the two efflux systems do not have specific substrates, but that the affinity seems to differ for the two QACs, BAC and CTAB. We further evolved a strain that lacks the two major QAC efflux systems, FepA and SugE1/2, to identify additional tolerance mechanisms. QAC stress leads to the overproduction of several efflux pumps in P. aeruginosa and E. coli (41, 43). As already indicated above, L. monocytogenes encodes over 200 efflux pumps in its genome, some of which likely respond to the presence of QACs, especially when the two main efflux systems, FepA and SugE1/2, are absent. We thus expected to identify mutations that cause the overproduction of other efflux pumps such as MdrL or Lde, which have previously been associated with QAC tolerance (29, 30, 37, 38). To our surprise, all isolated suppressors acquired mutations in lmo1753, which does not code for an additional efflux system. Instead, lmo1753 shares 64% sequence identity and 87.2% similarity with the gene coding for the diacylglycerol kinase DgkB from Bacillus subtilis, which contributes to the biosynthesis of lipoteichoic acids (LTAs) by recycling the toxic intermediate phosphatidic acid (44, 45). This finding indicates that SugE1/2 and FepA are the key BAC and CTAB efflux systems in the L. monocytogenes wild-type strain EGD-e. LTAs make up a great portion of the gram-positive cell wall and have been shown to play crucial roles in cellular growth, morphology, and division. They are anchored to the cell membrane and mainly consist of a polyglycerolphosphate backbone that contributes to the overall negative surface charge of the cell (46). The negatively charged backbone can be masked by decoration with positively charged D-alanylation. This decoration can be rather flexible and can fluctuate according to environmental and cellular cues, allowing adjustment of the cellular surface charge and hence variation in the cation homeostasis of the membrane (47). A decrease in cellular surface charge was previously associated with the survival of adapted E. coli strains in the presence of BAC, as they carried mutations in lpxM, encoding an enzyme involved in lipid A biosynthesis (42). Likewise, an increased negative surface charge was shown to be beneficial in a high-level BAC-tolerant Pseudomonas fluorescence strain (48). It is tempting to speculate that mutations in lmo1753 result in altered LTA synthesis followed by a distorted negative surface charge subsequently hindering binding of the positively charged head groups of BAC and CTAB. While the activity of DgkB has often mainly been discussed in the context of LTA biosynthesis, phosphatidic acid can also be utilized for the production of other glycolipids and phospholipids, including cardiolipin, lysyl-phosphatidylglycerol, or phosphatidylethanolamine. Likewise, diacylglycerol, the substrate of DgkB, is aside from LTA biosynthesis also crucial for the production of triglucosyldiacyl-glycerol (49). Hence, aberrant DgkB activity might generally result in an altered lipid profile. Besides efflux systems, changes in fatty acid composition and concomitant altered membrane fluidity have been proposed to contribute to QAC tolerance in several organisms. A study from 2002 described a tolerant L. monocytogenes isolate that showed a slight shift in the length of fatty acids (14). General alterations of the fatty acid profile and content were likewise associated with QAC tolerance in Serratio marcescens (50) and P. aeruginosa (51, 52). It remains elusive how mutations in lmo1753 contribute to QAC tolerance, but our findings highlight the ability of L. monocytogenes to adapt to QAC via an export-independent mechanism. One of the ΔfepA ΔsugE1/2 suppressors showed enhanced tolerance toward BAC in comparison to the other isolated mutants with the same genetic background. Interestingly, the strain acquired, in addition to the mutation in lmo1753, a mutation in the promoter region of lmo1682, which encodes a putative major facilitator family transporter. To our knowledge, no function was assigned for this transporter so far; however, our study suggests that it might be involved in the export of BAC. Further analysis of the transporter is required to elucidate its role in the efflux of QACs.

It has to be mentioned that all suppressors were isolated on BHI complex medium and in the presence of below working concentrations of BAC and CTAB. Those rather ideal conditions are not commonly found in food-processing facilities. However, similar BAC concentrations are often found in hard-to-reach places when disinfectants are not properly applied and concentrations of approximately 0.5 µg/mL were, for instance, reported in household wastewater, creating an environment that allows adaptation of the pathogen prior to entering food-processing plants (36). Altogether, our study supported previous findings that designated the efflux pump FepA as the major BAC extrusion system in L. monocytogenes. We further showed that SugE1/2 plays a similar role for CTAB tolerance and that both systems are the two main efflux systems for BAC and CTAB. Our suppressor screen also revealed the ability of L. monocytogenes to acquire tolerance independent of the presence and/or overexpression of efflux systems, likely due to alterations in the lipid profile, which will be further analyzed in the future.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

All strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Supplementary Material 1. Escherichia coli strains were grown in lysogeny broth (LB) medium and L. monocytogenes strains in brain heart infusion medium at 37°C unless otherwise stated. If appropriate, antibiotics and supplements were added to the medium at the following concentrations: for E. coli cultures, ampicillin (Amp) at 100 µg/mL, kanamycin (Kan) at 50 µg/mL, and for L. monocytogenes strains, chloramphenicol at 7.5 µg/mL, Kan at 50 µg/mL, erythromycin (Erm) at 5 µg/mL and IPTG at 1 mM.

Strain and plasmid construction

All primers used in this study are listed in Supplementary Material 1. For the markerless in-frame deletion of fepA (lmo2087) and sugE1/2 (lmo0853-lmo0854), approximately 1-kb DNA fragments upstream and downstream of the fepA gene were amplified by PCR using the primer pairs LMS484/LMS485 and LMS486/LMS487 (fepA) and JR247/JR248 and JR249/JR250 (sugE1/2). The resulting PCR products were fused in a second PCR using primers LMS485/LMS487 (fepA) and JR247/JR250 (sugE1/2). The products were cut with KpnI and SalI and ligated into pKSV7 that had been cut with the same enzymes. The resulting plasmids, pKSV7-ΔfepA and pKSV7-ΔsugE1/2, were recovered in E. coli XL1-Blue, yielding strains EJR230 and EJR229, respectively. Plasmids pKSV7-ΔfepA and pKSV7-ΔsugE1/2 were transformed into L. monocytogenes EGD-e, and the genes were deleted by allelic exchange according to a previously published method (53), yielding strains EGD-e ΔfepA (LJR261) and EGD-e ΔsugE1/2 (LJR262), respectively. For the construction of the ΔfepAΔsugE1/2 double deletion strain, plasmid pKSV7-ΔsugE1/2 was transformed into EGD-e ΔfepA, and sugE1/2 was deleted by allelic exchange, resulting in strain LJR329. For the construction of pIMK3-fepA and pIMK3-sugE1/2, the fepA and sugE1/2 genes were amplified using the primer pairs LMS478/LMS479 and JR262/JR263, respectively. Fragments were cut with enzymes NcoI and SalI and ligated into plasmid pIMK3 that had been cut with the same enzymes. The resulting plasmids pIMK3-fepA and pIMK3-sugE1/2 were recovered in E. coli XL10-Gold yielding strains EJR227 and EJR259, respectively. Both plasmids were transformed into L. monocytogenes strain EGD-e, resulting in the construction of strains LJR231 and LJR301, respectively, in which the expression of fepA and sugE1/2 is under the control of an IPTG-inducible promoter. For the construction of a fepA complementation strain, plasmid pIMK3-fepA was transformed into EGD-e ΔfepA, yielding strain LJR265.

For the construction of pWH844-fepA, the fepA gene was amplified with primer pairs FD1/FD2 using EGD-e wild-type DNA or the DNA of suppressor strain LJR218 as template. The PCR fragments were digested with BamHI and SalI and ligated into pWH844 that had been cut with the same enzymes. The resulting plasmids, pWH844-fepRWT and pWH844-fepRL24F , were recovered in XL10-Gold, yielding strains EJR242 and EJR248, respectively.

For the construction of promoter lacZ fusions, the promoter region of fepR was amplified with primers FD5 and FD6 using genomic DNA of the L. monocytogenes wild-type strain EGD-e or the BAC-tolerant strains EGD-e PfepR G-27T (LJR188) or EGD-e PfepR A-33G (LJR215) as template DNA. The PCR fragments were digested with BamHI and SalI and ligated into plasmid pPL3e-lacZ, which contains the promoterless lacZ gene. The resulting plasmids, pPL3e-PfepR-lacZ, pPL3e-PfepR G-27T-lacZ, and pPL3e-PfepR A-33G-lacZ, were recovered in E. coli DH5α yielding strains EJR257, EJR258, and EJR260, respectively. Plasmids pPL3e-PfepR-lacZ, pPL3e-PfepR G-27T-lacZ, and pPL3e-PfepR A-33G-lacZ were subsequently transformed into EGD-e, yielding strains EGD-e pPL3e-PfepR-lacZ (LJR336), EGD-e pPL3e-PfepR G-27T-lacZ (LJR302), and EGD-e pPL3e-PfepR A-33G-lacZ (LJR303).

Generation of suppressors and whole-genome sequencing

For the generation of BAC-adapted suppressors, stationary or exponentially grown EGD-e cultures were selected on BHI plates containing 4- or 6-µg/mL BAC. For the stationary grown EGD-e cultures, overnight cultures were adjusted to an OD600 of 0.1, and 100 µL was plated on BHI plates containing 4-µg/mL BAC. For exponentially grown cultures, overnight cultures of EGD-e were adjusted to an OD600 of 0.1 and grown until they reached an OD600 of 0.3–0.5. Cultures were then adjusted to an OD600 of 0.1, and 100 µL was plated on BHI plates containing 4- and 6-µg/mL BAC. The plates were incubated at 37°C overnight, and single colonies were restreaked twice on 4- and 6-µg/mL BAC, respectively. For adaptation of the wild-type strain to CTAB, as well as EGD-e ΔfepA, EGD-e ΔsugE1/2, and EGD-e ΔfepA ΔsugE1/2 to BAC and CTAB, overnight cultures of the different strains were adjusted to an OD600 of 0.1 and grown to an OD600 of 0.3–0.5. Cultures were adjusted again to an OD600 of 0.1, and 100 µL was plated on BHI plates supplemented with 4-, 5-, or 6-µg/mL BAC and 2- or 4-µg/mL CTAB. Plates were incubated at 37°C overnight or in the case of EGD-e ΔfepA and EGD-e ΔfepA ΔsugE1/2 in the presence of BAC for 2 d. Again, single colonies were restreaked twice on BHI plates supplemented with the selective pressure they were originally isolated from. Genomic DNA of a selection of BAC- and CTAB-adapted strains was isolated and either prescreened for mutations in fepR or sugR, or sent to SeqCoast Genomics (Portsmouth, NH, USA) for whole-genome sequencing. The genome sequences were determined by short read sequencing (150-bp paired end) using an Illumina MiSeq system (San Diego, CA, USA). The reads were trimmed and mapped to the L. monocytogenes EGD-e reference genome (NC_003210) using the Geneious prime v.2021.0.1 (Biomatters Ltd., New Zealand). Single-nucleotide polymorphisms with a variant frequency of at least 90% and a coverage of more than 25 reads were considered as mutations. All identified mutations were verified by PCR amplification and Sanger sequencing. The whole-genome sequencing data were deposited at the European Nucleotide Archive under accession number PRJEB62646.

Drop dilution assay

Overnight cultures of the indicated L. monocytogenes strains were adjusted to an OD600 of 1. IPTG and Kan were supplemented to the overnight cultures of strains carrying pIMK3-plasmids. Serial dilutions (5 µL) of each culture were spotted on BHI agar plates, BHI agar plates containing 4-µg/mL BAC, 6-µg/mL BAC, 2-µg/mL CTAB, 4-µg/mL CTAB, 1-µg/mL ciprofloxacin, 0.5-µg/mL gentamycin, or 1-µg/mL cefuroxime. Where indicated, plates were supplemented with 1-mM IPTG. Images of plates were taken after 20–24 h of incubation at 37°C. Drop dilution assays were repeated at least three times.

Ethidium bromide assay

The ethidium bromide assay was performed as previously described with minor modifications (54). Briefly, overnight cultures of the indicated L. monocytogenes strains were diluted to an OD600 of 0.05 in fresh BHI medium and grown until an OD600 of 0.4–0.6. Cells of 2 mL were harvested by centrifugation at 1,200 × g for 5 min, washed once in 1-mL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer (pH 7.4) and finally resuspended in 1 mL PBS buffer (pH 7.4). Next, the OD600 of each sample was adjusted to 0.3 in PBS (pH 7.4), and 180 µL was transferred into the wells of a black 96-well plate. Twenty microliters of 50-µg/mL ethidium bromide was added to each well, and the absorbance was measured using the Synergy Mx microplate reader (BioTek) at 500-nm excitation and 580-nm emission wavelengths for 50 min.

Expression and purification of His-FepR

For the overexpression of His-FepR and His-FepRL24F, plasmids pWH844-fepR and pWH844-fepRL24F were transformed into E. coli strain BL21, and the resulting strains were grown in LB supplemented with Amp at 37°C. At an OD600 of 0.6–0.8, the expression of his-fepR and his-fepRL24F was induced by the addition of 1- mM IPTG, and the strains were grown for another 2 h at 37°C. Cells were collected by centrifugation at 11,325 × g for 10 min, washed once with 1× cell disruption buffer (ZAP; 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl), and the cell pellet was stored at −20°C until further use. The cell pellets were resuspended in 1× ZAP buffer, and the cells were passaged three times (18,000 lbf/in2) through an HTU DIGI-F press (G. Heinemann, Schwäbisch Gmünd, Germany). The cell debris was subsequently collected by centrifugation at 46,400 × g for 30 min. The supernatant was subjected to a Ni2+ nitrilotriacetic acid column (IBA, Göttingen, Germany), and His-FepA and His-FepAL24F were eluted using an imidazole gradient. Elution fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and selected fractions were subsequently dialyzed against 1× ZAP buffer with a spatula pinch of EDTA at 4°C overnight. Protein concentrations were determined by a Bradford protein assay (55) using the Bio-Rad protein assay dye reagent concentrate. Bovine serum albumin was used for a standard curve. The protein samples were stored at 4°C until further use. Two independent purifications were performed for each protein.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

EMSAs were performed as described elsewhere with minor modifications (56). Briefly, a 150-bp DNA fragment containing the fepR promoter was amplified using primers FD3 and FD4 from genomic DNA isolated from the wild-type strain EGD-e or EGD-e PfepR G-27T (LJR188) and EGD-e PfepR A-33G (LJR215). For the comparison of the binding abilities of His-FepR and His-FepRL24F to the fepR promoter, 25, 50, and 100 pmol of each protein were mixed with 250 pmol fepR promotor DNA. To compare the binding ability of His-FepR to the wild-type and the mutated fepR promoters, 25, 50, and 100 pmol of His-FepR were mixed with 250-pmol DNA of either the wild-type or the mutated fepR promoters. Apart from DNA and protein, 20-µL binding reactions contained 1 µL of DNA loading dye (50% glycerol, 0.1% bromophenol blue, 1× Tris-acetate-EDTA (TAE) and H2O), 50 mM NaCl, 2 µL 10× Tris-acetate buffer (250 mM Tris-base in H2O, set to pH 5.5 with acetic acid), 0.15 mM bovine serum albumin, 2.5 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol and 20 mM DTT. The samples were incubated for 5 min at 25°C and subsequently separated on 8% native Tris-acetate gels (6% polyacrylic acid, 1× Tris-acetate buffer, 0.15% ammonium persulfate, and 0.83% tetramethylethylenediamine) in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) buffer (0.05 M Tris base, 0.05 M boric acid, 1-mM Na2EDTA, and pH 10). A prerun of the gels was performed for 90 min at 50 V before the samples were loaded. The run was performed at 50 V for 2.5 h. The gels were stained in 50 mL 0.5× TBE buffer containing 5 µL HDGreen Plus DNA dye (INTAS, Göttingen, Germany) for 5 min and washed for 5 min with 0.5× TBE-buffer, rinsed three times with water and then washed with water for 30 min. The DNA bands were visualized using a Gel Doc XR+ (Bio Rad, Munich, Germany).

β-Galactosidase assays

For the comparison of the activity of the wild-type and mutated fepR promoters, overnight cultures (supplemented with Erm) of the indicated L. monocytogenes strains were diluted to an OD600 of 0.05 in BHI medium and grown for 5 h at 37°C. To determine the response of the fepR promoter to BAC, overnight cultures of EGD-e PfepR-lacZ were diluted to an OD600 of 0.05 in BHI medium and were grown at 37°C to an OD600 of 0.5 (±0.05). The culture was divided into two flasks and incubated for an additional 2 h at 37°C in the presence of 2.5 µg/mL BAC or in the absence of BAC. The final OD600 was measured for all cultures prior sample collection. For both assays, 1 mL of the corresponding cultures was collected, resuspended in 100-µL assay buffer with Triton X-100 (ABT buffer) (60 mM K2HPO4, 40 mM KH2PO4, 100 mM NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100; pH 7), snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until further use. The sample preparation was performed as described previously (57, 58). Briefly, samples were thawed, and 10-fold dilutions were prepared in ABT buffer. Fifty microliters of each dilution was mixed with 10 µL of 0.4-mg/mL 4-methyl-umbelliferyl-β-D-galactopyranoside (MUG) substrate (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) that was prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide and incubated for 60 min at room temperature in the dark. A reaction containing ABT buffer and the MUG substrate was used as negative control. After the incubation time, 20 µL of each reaction was transferred into the wells of a black 96-well plate containing 180µL ABT buffer, and fluorescence values were determined using a Synergy Mx microplate reader (BioTek) at 366-nm excitation and 445-nm emission wavelengths. A standard curve was obtained using 0.015625–4.0 µM of the fluorescent 4-methylumbelliferone standard. β-Galactosidase units, or MUG units, were calculated as (pmol of substrate hydrolyzed × dilution factor)/(culture volume in mL × OD600 × reaction time in min). The amount of hydrolyzed substrate was determined from the standard curve as (emission reading – y intercept)/slope.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Servier Medical Art for providing the cell membrane illustration. We are grateful to Julia Busse for technical assistance and thank Prof. Jörg Stülke for providing laboratory space, equipment, and consumables.

We are grateful to the Göttingen Center for Molecular Biosciences for financial support. This work was funded by the German research foundation grant RI 2920/3-1 to J.R.

L.M.S.: investigation, formal analysis, conceptualization, methodology, supervision, validation, visualization, and writing (original draft); F.D. and L.M.D.S.M.: investigation, formal analysis, and writing (review and editing); J.R.: Investigation, formal analysis, conceptualization, supervision, funding acquisition, visualization, and writing (original draft).

The authors declare no conflict of interest. All co-authors have seen and agree with the contents of the manuscript, and there is no financial interest to report.

Contributor Information

Jeanine Rismondo, Email: jrismon@gwdg.de.

Kalliopi Rantsiou, University of Turin, Gruglisco, Turin, Italy .

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

The following material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1128/spectrum.01441-23.

Graphical abstract.

Table S1 and S2; Figures S1 and S2.

ASM does not own the copyrights to Supplemental Material that may be linked to, or accessed through, an article. The authors have granted ASM a non-exclusive, world-wide license to publish the Supplemental Material files. Please contact the corresponding author directly for reuse.

REFERENCES

- 1. Allerberger F, Wagner M. 2010. Listeriosis: a resurgent foodborne infection. Clin Microbiol Infect 16:16–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.03109.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. EFSA and ECDC . 2022. The European union one health 2021 zoonoses report. European Food Safety Authority. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rietberg K, Lloyd J, Melius B, Wyman P, Treadwell R, Olson G, Kang M-G, Duchin JS. 2016. Outbreak of Listeria monocytogenes infections linked to a pasteurized ice cream product served to hospitalized patients. Epidemiol Infect 144:2728–2731. doi: 10.1017/S0950268815003039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Carlin CR, Roof S, Wiedmann M. 2022. Assessment of reference method selective broth and plating media with 19 Listeria species highlights the importance of including diverse species in Listeria method evaluations. J Food Prot 85:494–510. doi: 10.4315/JFP-21-293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thomas J, Govender N, McCarthy KM, Erasmus LK, Doyle TJ, Allam M, Ismail A, Ramalwa N, Sekwadi P, Ntshoe G, Shonhiwa A, Essel V, Tau N, Smouse S, Ngomane HM, Disenyeng B, Page NA, Govender NP, Duse AG, Stewart R, Thomas T, Mahoney D, Tourdjman M, Disson O, Thouvenot P, Maury MM, Leclercq A, Lecuit M, Smith AM, Blumberg LH. 2020. Outbreak of listeriosis in south Africa associated with processed meat. N Engl J Med 382:632–643. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1907462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Osek J, Lachtara B, Wieczorek K. 2022. Listeria monocytogenes - how this pathogen survives in food-production environments? Front Microbiol 13:866462. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.866462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zinchenko AA, Sergeyev VG, Yamabe K, Murata S, Yoshikawa K. 2004. DNA compaction by divalent cations: structural specificity revealed by the potentiality of designed quaternary diammonium salts. Chembiochem 5:360–368. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200300797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Aase B, Sundheim G, Langsrud S, Rørvik LM. 2000. Occurrence of and a possible mechanism for resistance to a quaternary ammonium compound in Listeria monocytogenes. Int J Food Microbiol 62:57–63. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(00)00357-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Romanova NA, Wolffs PFG, Brovko LY, Griffiths MW. 2006. Role of efflux pumps in adaptation and resistance of Listeria monocytogenes to benzalkonium chloride. Appl Environ Microbiol 72:3498–3503. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.5.3498-3503.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Romanova N, Favrin S, Griffiths MW. 2002. Sensitivity of Listeria monocytogenes to sanitizers used in the meat processing industry. Appl Environ Microbiol 68:6405–6409. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.12.6405-6409.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Soumet C, Ragimbeau C, Maris P. 2005. Screening of benzalkonium chloride resistance in Listeria monocytogenes strains isolated during cold smoked fish production. Lett Appl Microbiol 41:291–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2005.01763.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Meier AB, Guldimann C, Markkula A, Pöntinen A, Korkeala H, Tasara T. 2017. Comparative phenotypic and genotypic analysis of swiss and finnish Listeria monocytogenes isolates with respect to benzalkonium chloride resistance. Front Microbiol 8:397. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lundén J, Autio T, Markkula A, Hellström S, Korkeala H. 2003. Adaptive and cross-adaptive responses of persistent and non-persistent Listeria monocytogenes strains to disinfectants. Int J Food Microbiol 82:265–272. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(02)00312-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. To MS, Favrin S, Romanova N, Griffiths MW. 2002. Postadaptational resistance to benzalkonium chloride and subsequent physicochemical modifications of Listeria monocytogenes. Appl Environ Microbiol 68:5258–5264. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.11.5258-5264.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Guérin A, Bridier A, Le Grandois P, Sévellec Y, Palma F, Félix B, Roussel S, Soumet C. 2021. Exposure to quaternary ammonium compounds selects resistance to ciprofloxacin in Listeria monocytogenes. Pathogens 10:220. doi: 10.3390/pathogens10020220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Guérin F, Galimand M, Tuambilangana F, Courvalin P, Cattoir V. 2014. Overexpression of the novel MATE fluoroquinolone efflux pump FepA in Listeria monocytogenes is driven by inactivation of its local repressor FepR. PLoS One 9:e106340. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rakic-Martinez M, Drevets DA, Dutta V, Katic V, Kathariou S. 2011. Listeria monocytogenes strains selected on ciprofloxacin or the disinfectant benzalkonium chloride exhibit reduced susceptibility to ciprofloxacin, gentamicin, benzalkonium chloride, and other toxic compounds. Appl Environ Microbiol 77:8714–8721. doi: 10.1128/AEM.05941-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bland R, Waite-Cusic J, Weisberg AJ, Riutta ER, Chang JH, Kovacevic J. 2021. Adaptation to a commercial quaternary qmmonium compound Sanitizer leads to cross-resistance to select antibiotics in Listeria monocytogenes isolated from fresh produce environments. Front Microbiol 12:782920. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.782920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jiang X, Yu T, Liang Y, Ji S, Guo X, Ma J, Zhou L. 2016. Efflux pump-mediated benzalkonium chloride resistance in Listeria monocytogenes isolated from retail food. Int J Food Microbiol 217:141–145. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2015.10.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Martínez-Suárez JV, Ortiz S, López-Alonso V. 2016. Potential impact of the resistance to quaternary ammonium disinfectants on the persistence of Listeria monocytogenes in food processing environments. Front Microbiol 7:638. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jiang X, Ren S, Geng Y, Yu T, Li Y, Liu L, Liu G, Wang H, Shi L. 2020. The sug operon involves in resistance to quaternary ammonium compounds in Listeria monocytogenes EGD-e. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 104:7093–7104. doi: 10.1007/s00253-020-10741-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Müller A, Rychli K, Muhterem-Uyar M, Zaiser A, Stessl B, Guinane CM, Cotter PD, Wagner M, Schmitz-Esser S. 2013. Tn6188 - a novel transposon in Listeria monocytogenes responsible for tolerance to benzalkonium chloride. PLoS One 8:e76835. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Müller A, Rychli K, Zaiser A, Wieser C, Wagner M, Schmitz-Esser S. 2014. The Listeria monocytogenes transposon Tn6188 provides increased tolerance to various quaternary ammonium compounds and ethidium bromide. FEMS Microbiol Lett 361:166–173. doi: 10.1111/1574-6968.12626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kovacevic J, Ziegler J, Wałecka-Zacharska E, Reimer A, Kitts DD, Gilmour MW. 2016. Tolerance of Listeria monocytogenes to quaternary ammonium sanitizers is mediated by a novel efflux pump encoded by emrE. Appl Environ Microbiol 82:939–953. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03741-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Elhanafi D, Dutta V, Kathariou S. 2010. Genetic characterization of plasmid-associated benzalkonium chloride resistance determinants in a Listeria monocytogenes strain from the 1998-1999 outbreak. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:8231–8238. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02056-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dutta V, Elhanafi D, Kathariou S. 2013. Conservation and distribution of the benzalkonium chloride resistance cassette bcrABC in Listeria monocytogenes. Appl Environ Microbiol 79:6067–6074. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01751-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Minarovičová J, Véghová A, Mikulášová M, Chovanová R, Šoltýs K, Drahovská H, Kaclíková E. 2018. Benzalkonium chloride tolerance of Listeria monocytogenes strains isolated from a meat processing facility is related to presence of plasmid-borne bcrABC cassette. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 111:1913–1923. doi: 10.1007/s10482-018-1082-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yu T, Jiang X, Zhang Y, Ji S, Gao W, Shi L. 2018. Effect of benzalkonium chloride adaptation on sensitivity to antimicrobial agents and tolerance to environmental stresses in Listeria monocytogenes Front Microbiol 9:2906. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mata MT, Baquero F, Pérez-Díaz JC. 2000. A multidrug efflux transporter in Listeria monocytogenes. FEMS Microbiol Lett 187:185–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09158.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jiang X, Yu T, Xu Y, Wang H, Korkeala H, Shi L. 2019. MdrL, a major facilitator superfamily efflux pump of Listeria monocytogenes involved in tolerance to benzalkonium chloride. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 103:1339–1350. doi: 10.1007/s00253-018-9551-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bolten S, Harrand AS, Skeens J, Wiedmann M. 2022. Nonsynonymous mutations in fepR are associated with adaptation of Listeria monocytogenes and other Listeria spp. to low concentrations of benzalkonium chloride but do not increase survival of L. Monocytogenes and other Listeria spp. after exposure to benzalkonium chloride concentrations recommended for use in food processing environments. Appl Environ Microbiol 88:e0048622. doi: 10.1128/aem.00486-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Douarre P-E, Sévellec Y, Le Grandois P, Soumet C, Bridier A, Roussel S. 2022. FepR as a central genetic target in the adaptation to quaternary ammonium compounds and cross-resistance to ciprofloxacin in Listeria monocytogenes. Front Microbiol 13:864576. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.864576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Weber DJ, Rutala WA, Sickbert-Bennett EE. 2007. Outbreaks associated with contaminated antiseptics and disinfectants. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 51:4217–4224. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00138-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kohanski MA, DePristo MA, Collins JJ. 2010. Sublethal antibiotic treatment leads to multidrug resistance via radical-induced mutagenesis. Mol Cell 37:311–320. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nakata K, Tsuchido T, Matsumura Y. 2011. Antimicrobial cationic surfactant, cetyltrimethylammonium bromide, induces superoxide stress in Escherichia coli cells. J Appl Microbiol 110:568–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2010.04912.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tezel U, Pavlostathis SG. 2015. Quaternary ammonium disinfectants: microbial adaptation, degradation and ecology. Curr Opin Biotechnol 33:296–304. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2015.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jiang X, Zhou L, Gao D, Wang Y, Wang D, Zhang Z, Chen M, Su Y, Li L, Yan H, Shi L. 2012. Expression of efflux pump gene Lde in ciprofloxacin-resistant foodborne isolates of Listeria monocytogenes. Microbiol Immunol 56:843–846. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2012.00506.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Godreuil S, Galimand M, Gerbaud G, Jacquet C, Courvalin P. 2003. Efflux pump Lde is associated with fluoroquinolone resistance in Listeria monocytogenes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 47:704–708. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.2.704-708.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mereghetti L, Quentin R, Marquet-Van Der Mee N, Audurier A. 2000. Low sensitivity of Listeria monocytogenes to quaternary ammonium compounds. Appl Environ Microbiol 66:5083–5086. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.11.5083-5086.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ebner R, Stephan R, Althaus D, Brisse S, Maury M, Tasara T. 2015. Phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of Listeria monocytogenes strains isolated during 2011–2014 from different food Matrices in Switzerland. Food Control 57:321–326. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2015.04.030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kim M, Weigand MR, Oh S, Hatt JK, Krishnan R, Tezel U, Pavlostathis SG, Konstantinidis KT. 2018. Widely used benzalkonium chloride disinfectants can promote antibiotic resistance. Appl Environ Microbiol 84:e01201-18. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01201-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nordholt N, Kanaris O, Schmidt SBI, Schreiber F. 2021. Persistence against benzalkonium chloride promotes rapid evolution of tolerance during periodic disinfection. Nat Commun 12:6792. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-27019-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Jia Y, Lu H, Zhu L. 2022. Molecular mechanism of antibiotic resistance induced by mono- and twin-chained quaternary ammonium compounds. Sci Total Environ 832:155090. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.155090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jerga A, Lu Y-J, Schujman GE, de Mendoza D, Rock CO. 2007. Identification of a soluble diacylglycerol kinase required for lipoteichoic acid production in Bacillus subtilis. J Biol Chem 282:21738–21745. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703536200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Matsuoka S, Hashimoto M, Kamiya Y, Miyazawa T, Ishikawa K, Hara H, Matsumoto K. 2011. The Bacillus subtilis essential gene dgkB is dispensable in mutants with defective lipoteichoic acid synthesis. Genes Genet Syst 86:365–376. doi: 10.1266/ggs.86.365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Campeotto I, Percy MG, MacDonald JT, Förster A, Freemont PS, Gründling A. 2014. Structural and mechanistic insight into the Listeria monocytogenes two-enzyme lipoteichoic acid synthesis system. J Biol Chem 289:28054–28069. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.590570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Percy MG, Gründling A. 2014. Lipoteichoic acid synthesis and function in gram-positive bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol 68:81–100. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-091213-112949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Nagai K, Murata T, Ohta S, Zenda H, Ohnishi M, Hayashi T. 2003. Two different mechanisms are involved in the extremely high-level benzalkonium chloride resistance of a Pseudomonas fluorescens strain. Microbiol Immunol 47:709–715. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2003.tb03440.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hashimoto M, Seki T, Matsuoka S, Hara H, Asai K, Sadaie Y, Matsumoto K. 2013. Induction of extracytoplasmic function sigma factors in Bacillus subtilis cells with defects in lipoteichoic acid synthesis. Microbiology (Reading) 159:23–35. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.063420-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Chaplin CE. 1952. Bacterial resistance to quaternary ammonium disinfectants. J Bacteriol 63:453–458. doi: 10.1128/jb.63.4.453-458.1952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Guerin-Mechin L, Dubois-Brissonnet F, Heyd B, Leveau JY. 2000. Quaternary ammonium compound stresses induce specific variations in fatty acid composition of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int J Food Microbiol 55:157–159. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(00)00189-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Jones MV, Herd TM, Christie HJ. 1989. Resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to amphoteric and quaternary ammonium biocides. Microbios 58:49–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Camilli A, Tilney LG, Portnoy DA. 1993. Dual roles of plcA in Listeria monocytogenes pathogenesis. Mol Microbiol 8:143–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01211.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kaval KG, Hahn B, Tusamda N, Albrecht D, Halbedel S. 2015. The PadR-like transcriptional regulator LftR ensures efficient invasion of Listeria monocytogenes into human host cells. Front Microbiol 6:772. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Bradford MM. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 72:248–254. doi: 10.1006/abio.1976.9999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Dhiman A, Bhatnagar S, Kulshreshtha P, Bhatnagar R. 2014. Functional characterization of WalRK: a two-component signal transduction system from Bacillus anthracis. FEBS Open Bio 4:65–76. doi: 10.1016/j.fob.2013.12.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Gründling A, Burrack LS, Bouwer HGA, Higgins DE. 2004. Listeria monocytogenes regulates flagellar motility gene expression through MogR, a transcriptional repressor required for virulence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:12318–12323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404924101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Rismondo J, Halbedel S, Gründling A. 2019. Cell shape and antibiotic resistance are maintained by the activity of multiple FtsW and RodA enzymes in Listeria monocytogenes. mBio 10:e01448-19. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01448-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Graphical abstract.

Table S1 and S2; Figures S1 and S2.