ABSTRACT

There is an urgent need to develop new antifungals due to the increasing prevalence of multidrug-resistant fungal infections and the recent emergence of COVID-19-associated candidiasis. A good study model for evaluating new antifungal compounds is Candida glabrata, an opportunistic fungal pathogen with intrinsic resistance to azoles (the most common clinical drugs for treating fungal infections). The aim of the current contribution was to conduct in vitro tests of antifungal metabolites produced by the bacteria Streptomyces albidoflavus Q, identify their molecular structures, and utilize several techniques to provide evidence of their therapeutic target. S. albidoflavus was isolated from maize rhizospheric soil in Mexico and identified by phylogenomic analysis using a 92-gene core. Of the 66 metabolites identified in S. albidoflavus Q by a liquid chromatography-high resolution mass spectrometry (LC-HRMS) metabolomic analysis of the lyophilized supernatant, six were selected by the Way2drug server based on their in silico binding to the likely target, 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-CoA reductase (HMGR, the key enzyme in the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway). Molecular modeling studies show a relatively high binding affinity for the CgHMGR enzyme by two secondary metabolites: isogingerenone B (diaryl heptanoid) and notoginsenoside J (polycyclic triterpene). These secondary metabolites were able to inhibit ergosterol synthesis and affect yeast viability in vitro. They also caused alterations in the ultrastructure of the yeast cytoplasmic membrane, as evidenced by transmission electron microscopy. The putative target of isogingerenone B and notoginsenoside J is distinct from that of azole drugs (the most common clinical antifungals). The target for the latter is the lanosterol 14 alpha-demethylase enzyme (Erg11).

IMPORTANCE

Multidrug resistance has emerged among yeasts of the genus Candida, posing a severe threat to global health. The problem has been exacerbated by the pandemic associated with COVID-19, during which resistant strains of Candida auris and Candida glabrata have been isolated from patients infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus. To confront this challenge, the World Health Organization has invoked scientists to search for new antifungals with alternative molecular targets. This study identified 66 metabolites produced by the bacteria Streptomyces albidoflavus Q, 6 of which had promising properties for potential antifungal activity. The metabolites were tested in vitro as inhibitors of ergosterol synthesis and C. glabrata growth, with positive results. They were also found to damage the cytoplasmic membrane of the fungus. The corresponding molecular structures and their probable therapeutic target were established. The target is apparently distinct from that of azole drugs.

KEYWORDS: antifungal, multi-drug resistance, Candida glabrata, Streptomyces albidoflavus, WGS, metabolomics, ergosterol, HMGR (EC 1.1.1.34), cytoplasmic membrane, actinomycete, actinobacteria, plant-associated metabolites

INTRODUCTION

Many fungal infections are difficult to treat, such as those caused by yeasts of the genus Candida spp. when associated with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (1) (https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/covid-fungal.html), or certain other infections. The treatment of difficult fungal infections is further complicated by the growing prevalence of multidrug resistance among Candida species, rendering the common clinical drugs (e.g., amphotericin B, azoles, and echinocandins) ineffective and creating a severe threat to global health (2). To respond to this crisis, a multidisciplinary approach is needed that includes the search for sources of new antifungals with alternative molecular targets, the rational design and development of new drugs and vaccines, and accurate and timely diagnoses (https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance).

Among the Candida infections, which have become more frequent in recent years, C. albicans is the predominant cause of invasive infections (3). Invasiveness can also characterize healthcare-associated infections by C. glabrata, C. parapsilosis, C. krusei, and recently the multidrug-resistant C. auris (3). C. glabrata is a pathogenic yeast intrinsically resistant to azoles, and its recent pan-echinocandin-resistant clinical isolates are associated with the COVID-19 pandemic (2, 3). For this reason, it has become a model used in research to test new antifungal compounds for their effectiveness against pathogenic Candida species.

Bacteria of the Actinomycetes class, especially of the genus Streptomyces, are a possible source of new antifungals with alternative molecular targets. They produce numerous secondary metabolites with antifungal, antibacterial, and antiviral activities, including alkaloids, pigments, and toxins (4, 5). These metabolites are encoded by groups of genes denominated biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs). In Streptomyces, antimicrobial metabolites are encoded by hundreds of BGCs, including those classified as cryptic, silent, and dormant (6 – 9). Methods have been found to activate the biosynthesis of such metabolites (10 – 12). Indeed, the study of antifungals produced by actinobacteria of the Streptomyces genus over the last several years (13) has led to the successful identification, elaboration, and application of amphotericin B, natamycin, and nystatin (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Examples of antifungal compounds generated by actinobacteria of the genus Streptomyces spp., including commercial compounds and those in the developmental phase a

| Strain of Streptomyces spp. | Antifungal compound | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Streptomyces noursei | Nystatin (polyene) (commercial) | Campoy and Adrio (13). Doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2016.11.019 |

| Streptomyces nodosus | Amphotericin (polyene) (commercial) | Campoy and Adrio (13). Doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2016.11.019 |

| Streptomyces natalensis | Natamycin (polyene) (commercial) | Campoy and Adrio (13). Doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2016.11.019 |

| Streptomyces rimosus | Unknown | Lu et al. (14). Doi: 10.1002/jobm.201500666 |

| Streptomyces mutabilis | 2,4-Di-tert-butilfenol | Belghit et al. (15). Doi: 10.1016/j.mycmed.2016.03.001 |

| Streptomyces spp. ERI-04 | Unknown | Valanarasu et al. (16). Doi: 10.1016/j.mycmed.2010.09.001 |

| Streptomyces spp. MTCC 5680 | Macrolide polyene (PN00053) | Vartak et al. (17). Doi: 10.1111/lam.12229 |

| Streptomyces spp. SNM55 | Mohangamides A | Bae et al. (18). Doi: 10.1021/ol5037248 |

| Streptomyces albus J1074 | Surogamides | Xu et al. (19). Doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b02716 |

| Acyl-surugamides | ||

| Albucyclones | ||

| Albuquinone |

All the information was taken from the original reference article.

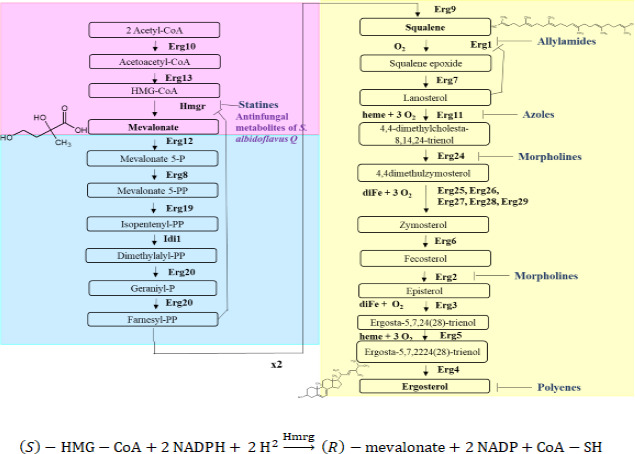

CgHMGR has been proposed as an alternative therapeutic target for new antifungals (20 – 23). It participates in the mevalonate biosynthesis pathway, the first module of the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway (Fig. 1) (24). Since ergosterol plays a critical role in the homeostasis and function of the cytoplasmic membrane, the enzymes involved in its biosynthetic pathway are promising targets for the design of new antifungals (21, 25) (Fig. 1).

Fig 1.

The biosynthetic pathway of ergosterol in yeasts, divided into three modules: the mevalonate pathway (in pink), the farnesyl pyrophosphate pathway (in blue), and the last step leading to ergosterol (in yellow). Enzymes, intermediates, inhibitors, and the requirements for oxygen, heme, and iron are indicated. Inhibitors are listed with their respective target: statins bind with HMGR, allylamines with Erg1, azoles with Erg11, morpholines with Erg2 and Erg24, and polyenes with ergosterol. 3-Hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-CoA reductase (HMGR) is the proposed target for secondary metabolites produced by Streptomyces albidoflavus. Below the boxes, the reaction described is catalyzed by the HMGR enzyme with NADPH as a cofactor.

Besides the antifungals from Streptomyces already in clinical use (e.g., amphotericin B, nystatin, and natamycin), the existence of other possibly useful antifungal compounds has been evidenced as well. However, many reports on such metabolites have left various factors undefined, including the strain and species of Streptomyces from which they are derived, the chemical structure of the active compound, and the therapeutic target (Table 1). In the current contribution, the Streptomyces strain isolated from rhizospheric soil of Mexican maize was identified as S. albidoflavus Q by phylogenomic analysis. Possible antifungal metabolites were discovered by metabolomic analysis. Plausible biosynthetic pathways involved in their synthesis are suggested. The CgHMGR enzyme is proposed as the likely therapeutic target of the metabolites tested in vitro based on their inhibition of ergosterol synthesis and experiments with growth recovery. These metabolites caused alterations in the cytoplasmic membrane, reduced the levels of ergosterol, and decreased the viability of C. glabrata. The probable mechanism of interaction between the antifungal metabolites and CgHMGR was defined by molecular modeling of the ligands and a thorough examination of the alterations generated in the yeast cytoplasmic membrane.

RESULTS

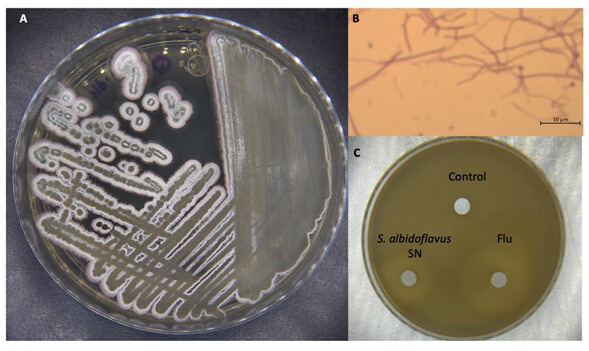

Phenotypic characteristics of Streptomyces albidoflavus Q

First, the phenotype of the bacterial strain was identified. The colonial morphology was characteristic of actinobacteria (i.e., powdery-looking dry colonies), while microscopic morphology evidenced a Gram-positive bacteria with filamentous structures (Fig. 2A and B). The S. albidoflavus Q supernatant, which was obtained, lyophilized, and resuspended in sterile water (see Materials and Methods), exhibited inhibition of the confluent growth of fluconazole-resistant C. glabrata (Fig. 2C).

Fig 2.

Phenotypic characteristics of Streptomyces albidoflavus Q. The strain was inoculated onto solid GAE medium and incubated at 28°C for 15 days. (A) Its colonial morphology is characteristic of actinobacteria. (B) The microscopic morphology corresponds to a Gram-positive bacteria with filamentous structures (1,000×). (C) S. albidoflavus metabolites inhibited C. glabrata growth. The supernatant (SN) of S. albidoflavus Q was concentrated by lyophilization and resuspended. Fluconazole (Flu) and water served as the positive and negative controls, respectively, for the inhibition of yeast growth (the modified M44 CLSI method).

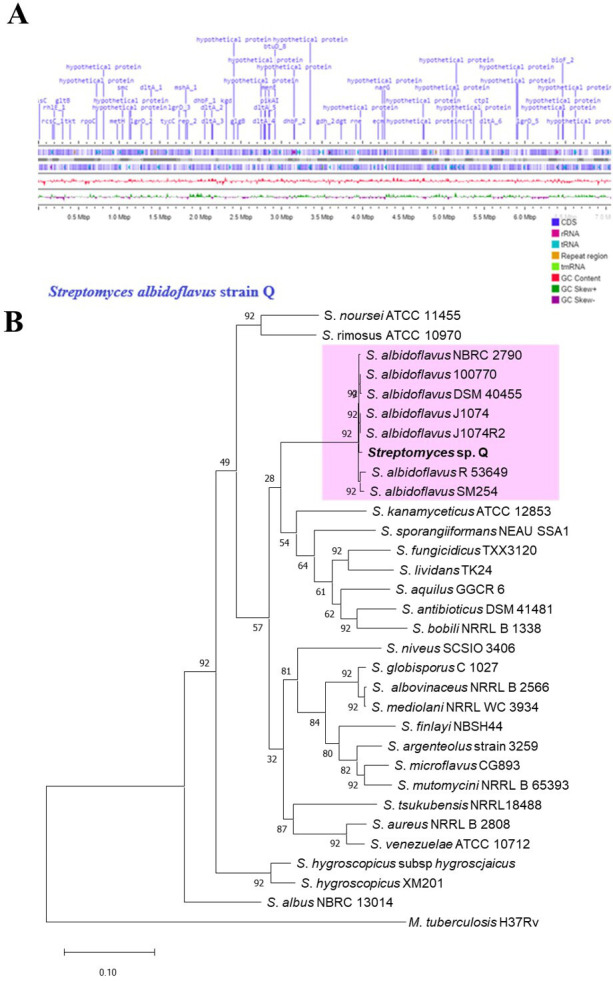

Whole-genome sequencing of Streptomyces albidoflavus Q and phylogenomic analysis

The quality control of the assembly estimated the total length of the contigs to be 6.95 Mbp for S. albidoflavus Q, with a G+C content of approximately 73% and an N50 of 425,381. There were 6,007 CDS, 6 rRNA, 96 tRNA, and 1 tmRNA (Fig. 3A).

Fig 3.

General features of the Streptomyces albidoflavus Q genome and the phylogenetic tree. (A) A linear representation of S. albidoflavus Q genome contigs was obtained with Proksee (https://proksee.ca). The scale is expressed in megabases (Mbp), and two dark blue lines denote forward and reverse strand CDSs, respectively. Some genes are portrayed in violet with the default setting of Proksee. The tRNA (blue arrows), rRNA (magenta arrows), and tmRNA (green arrows) are shown with violet lines. The content (in pink) and skew (in dark green and violet) of gene clusters are illustrated. (B) The phylogenomic tree of S. albidoflavus Q was inferred by concatenated alignment of 92 core genes (UBCGs). Gene support indices (GSIs) and percentage bootstrap values are given at branching points. Bars represent 0.10 substitution per position.

The species of this actinobacteria was identified through a phylogenomic analysis (see Materials and Methods). The phylogenomic tree was constructed with the up-to-date bacterial core gene (UBCG) software, which uses 92 concatenated genes to generate a maximum likelihood tree with gene support index values (Fig. 3B). Sequences of Streptomyces spp. and S. albidoflavus strains from other ecosystems, such as rhizosphere soil, marine soil, and the gut of an ant, are stored in the NCBI server.

Antifungal activity of the lyophilized supernatant of Streptomyces albidoflavus Q on Candida glabrata

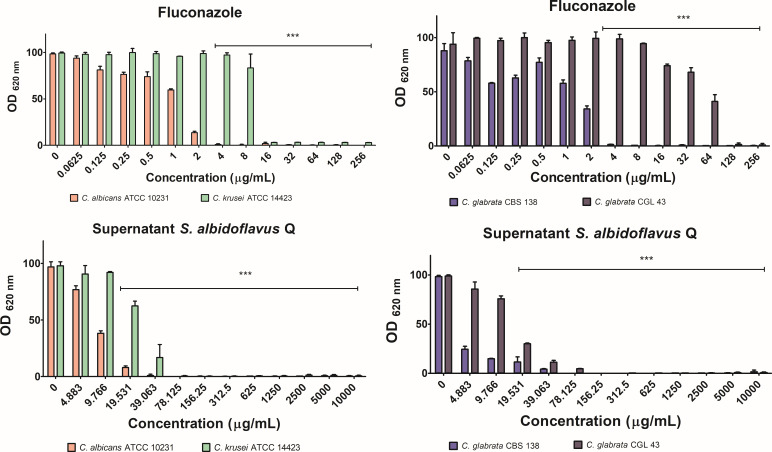

C. glabrata CGL 43 was adopted as the study model due to its intrinsic resistance to fluconazole. The controls consisted of two strains susceptible to the same antifungal drug: another strain of C. glabrata (CBS 138) and a C. albicans strain (ATCC 10231). C. krusei, which like C. glabrata CGL 43 is resistant to fluconazole, also served as a control (Fig. 4).

Fig 4.

Inhibition of the growth of Candida spp. While growth without any inhibitor served as the negative control, fluconazole was used as the positive control of inhibitory activity. The optical density was determined in a Thermo Scientific Multiskan FC microplate photometer at 620 nm (OD620) after incubation at 37°C for 24 h. The quantification of growth was expressed as the average ± standard deviation (SD) of optimal density values from three independent assays. Significant differences were analyzed by two-way ANOVA. ***P < 0.001.

Although fluconazole acts on the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway, its therapeutic target is not HMGR, but rather the enzyme encoded by ERG11 (lanosterol 14 alpha-demethylase). This enzyme participates in one of the last steps of ergosterol synthesis (Fig. 1). Fluconazole was used as a positive control.

For the evaluation of inhibition, the lyophilized supernatant of S. albidoflavus Q was applied at different concentrations. As the concentration increased, the growth of the yeast strain decreased, indicating a concentration-response effect (Fig. 4). A determination was made of the minimum inhibitory concentration that inhibits the growth of Candida spp. by 50% (MIC50) and 70–90% (MIC70-90). S. albidoflavus Q metabolites were able to inhibit the growth of C. glabrata CGL 43. The MIC50 and MIC70-90 values were lower than those of fluconazole (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

MIC50 and MIC70-90 values of fluconazole and the lyophilized supernatant of S. albidoflavus Q in relation to four Candida spp.

| C. albicans ATCC 10231 | C. krusei ATCC 14423 | C. glabrata CBS 138 | C. glabrata CGL 43 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibitor | MIC50 | MIC70–90 | MIC50 | MIC70–90 (µg/mL) | MIC50 | MIC70–90 | MIC50 | MIC70-90 |

| Control a | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Fluconazole | 1.25 | 2 | 12 | 16 | 1.25 | 2 | 50 | 64 |

| Lyophilized supernatant | 7.1 | 19.5 | 23.5 | 39.05 | 3.22 | 4.8 | 14.15 | 39.1 |

The negative control consisted of the yeast culture without any inhibitor. The dashes indicate the lack of effect on the yeast strains in the absence of an inhibitor.

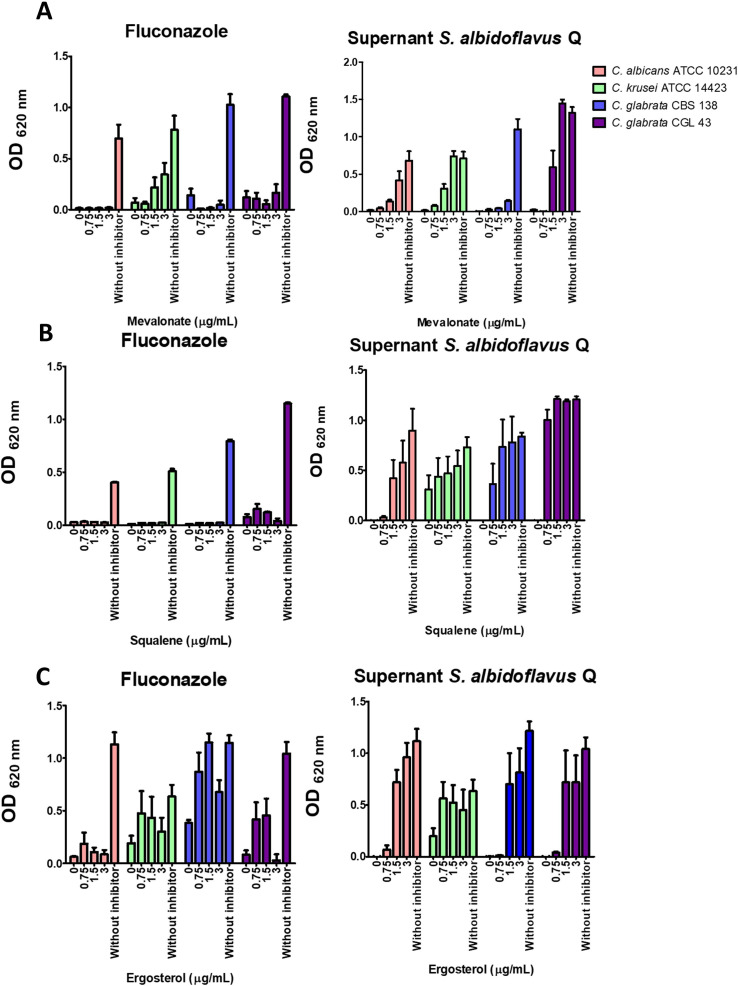

Candida spp. growth recovery by adding mevalonate, squalene, or ergosterol

A yeast growth recovery experiment explored the possibility that the secondary metabolites produced by S. albidoflavus Q affect ergosterol biosynthesis in C. glabrata. The antifungal metabolites were applied at the previously established sublethal concentrations (MIC70-90). The antifungal compounds inhibited the growth of the yeasts, but the addition of exogenous mevalonate, squalene, or ergosterol to the culture medium resulted in growth recovery for most yeast strains. In the case of the lyophilized supernatant as the antifungal, the growth recovery of the yeast increased with higher concentrations of exogenous mevalonate, squalene, or ergosterol. The recovery was not as evident with C. glabrata CBS 138 (Fig. 5). When the yeasts were treated with fluconazole, growth recovery was only observed with ergosterol, as expected (since the azoles act on the Erg11 enzyme, which is in the last stage of the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway). C. albicans ATTC 10231 did not show recovery with ergosterol.

Fig 5.

A Candida spp. growth rescue assay was carried out. The yeasts were first treated with fluconazole or the metabolites of S. albidoflavus at sublethal concentrations, followed by the addition of exogenous mevalonate, squalene, or ergosterol to the culture medium. Following both initial treatments, ergosterol caused Candida spp. to undergo growth recovery. Squalene and mevalonate promoted growth recovery of Candida spp. after treatment with S. albidoflavus metabolites but not after treatment with fluconazole. The yeasts without antifungal treatment served as the control. Yeast growth was quantified by optical density in a Thermo Scientific Multiskan FC microplate photometer at 620 nm (OD620) upon completion of incubation at 37°C for 24 h. The values are expressed as the average of three independent assays ± SD. The basal growth value was established with the control (the yeast without any inhibitor). Significant differences were analyzed by two-way ANOVA. ***P < 0.001.

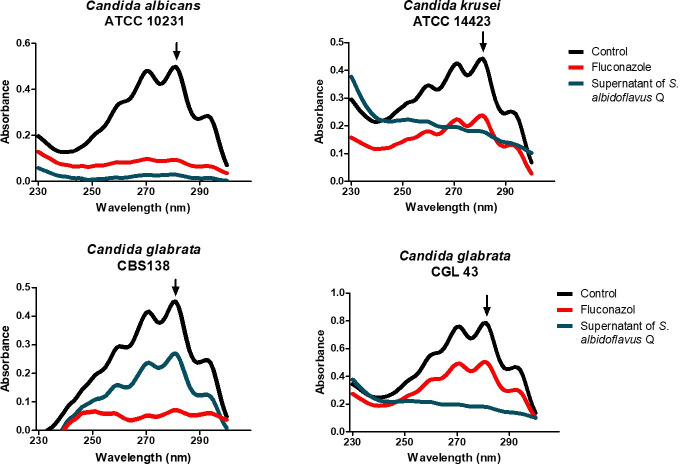

Effect of S. albidoflavus Q metabolites on ergosterol synthesis in Candida spp. species

A possible association between the inhibition of growth and the concentration of ergosterol in Candida spp. species was examined with each of the two treatments (the lyophilized supernatant and fluconazole as the control). The absorption spectra of the control displayed the characteristic four peaks of sterols (Fig. 6). The lyophilized supernatant at sublethal concentrations caused reduced ergosterol levels in 100 mg samples of the yeasts.

Fig 6.

Effect of the lyophilized supernatant of Streptomyces albidoflavus Q on the concentration of ergosterol in Candida spp. species. The different species were grown in YPD liquid yeast medium and treated with sublethal concentrations of the inhibitors. The control was the growth of the yeasts in the absence of any inhibitor. The yeasts were incubated at 37°C for 18 h under constant shaking at 200 rpm. The concentration of the extracted sterols (in the n-heptane layer) was determined by spectrophotometrically scanning them (from 230 to 300 nm). The extraction of total sterols was performed on a 100 mg sample of yeast.

The absorption peak at 281.5 nm was used to quantify the ergosterol concentration, allowing for the calculation of the percentage of inhibition of its synthesis. Compared to fluconazole, the metabolites of the supernatant of S. albidoflavus Q afforded a greater percentage of inhibition of ergosterol in the yeasts (Table 3). This result suggests that the target site of the metabolites is located at some stage of the ergosterol biosynthetic pathway.

TABLE 3.

Percentage of ergosterol inhibition found in the distinct species of Candida spp. after treatment with fluconazole or the lyophilized supernatant of S. albidoflavus Q, or in the absence of treatment (the control)

| C. albicans ATCC 10231 | C. krusei ATCC 14423 | C. glabrata CBS 138 | C. glabrata CGL 43 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control a | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fluconazole | 60 | 15 | 41 | 29 |

| Lyophilized supernatant | 89 | 89 | 100 | 66 |

The control consisted of the yeast cultivated in the absence of an antifungal. Each Candida spp. was subjected to a sublethal concentration of fluconazole or the lyophilized supernatant of S. albidoflavus Q. The yeasts were incubated at 37°C for 18 h under constant shaking at 200 rpm.

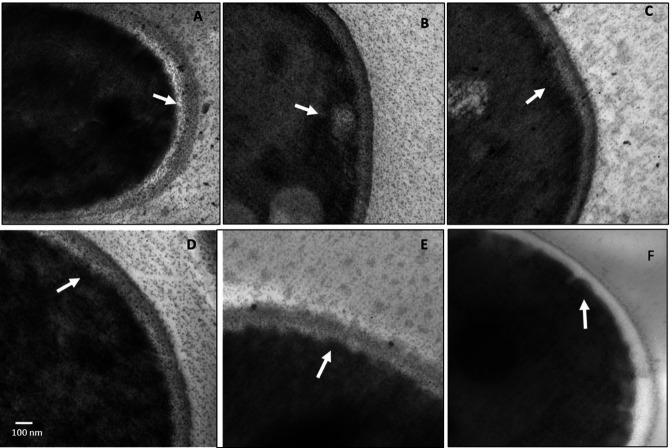

Effect of the S. albidoflavus Q supernatant on the cytoplasmic membrane structure of C. glabrata

Unlike the untreated control, yeasts treated with a sublethal concentration of fluconazole or the lyophilized supernatant of S. albidoflavus Q showed morphological changes. The yeasts were treated with inhibitors and examined by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). In the micrograph of the yeasts treated with the S. albidoflavus Q supernatant, the cellular membrane exhibited invaginations, probably caused by antifungal metabolites produced by the bacterium (Fig. 7). Fluconazole was used as the positive control.

Fig 7.

Image of Candida glabrata treated with the S. albidoflavus Q supernatant, taken with a transmission electron microscope. Micrographs: (A–C) of C. glabrata CBS 138 and (D–F) of C. glabrata CGL 43. (A and D) Without treatment (negative control); (B and E) treated with fluconazole (positive control); (C and F) treated with the lyophilized supernatant of S. albidoflavus Q. The arrows indicate the cytoplasmic membrane with (C and F) and without (A and D) treatment. The yeasts were each treated with sublethal concentrations of the antifungals at 37°C for 18 h in YPD liquid yeast medium.

Toxicity of the supernatant tested in the Galleria mellonella model

The possible toxicity of the metabolites found in the supernatant of S. albidoflavus Q was evaluated by using the Galleria mellonella model. However, no toxicity was observed, as shown by the 50% DMSO toxicity control (Table S2).

Metabolomics of Streptomyces albidoflavus Q

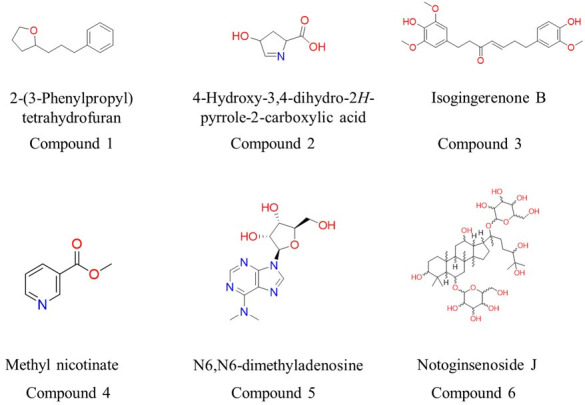

Based on a metabolomic study of the lyophilized supernatant of S. albidoflavus Q, at least 66 metabolites were identified (Fig. S1). They were analyzed by the Way2drug server (http://way2drug.com/passonline/) to find potential inhibitors of CgHMGR. The corresponding chemical structures are shown in Fig. 8.

Fig 8.

Structures of metabolites with potential inhibitory activity on CgHMGR. First, 66 secondary metabolites were found in the lyophilized supernatant of S. albidoflavus Q through metabolomic analysis. Subsequently, they were examined by using the web resource PASS Online, deposited in server Way2Drug (http://way2drug.com/passonline/), which selected the most probable inhibitors.

M-BGCs and metabolism in S. albidoflavus Q

Detailed analysis of the S. albidoflavus Q genome sequence using antiSMASH 4.0 and manual curation suggests the existence of 38 BGCs that encode diverse special metabolites (Table 4). Notoginsenoside J (compound 6; Fig. 8) has a triterpenoid structure similar to hopanoids. Hence, the metabolite bacterial core gene (M-BCG) present in the sequence of region 1.4 could possibly be related to the biosynthesis pathway of this compound. Other characteristics of the compound are discussed below.

TABLE 4.

Known/predicted metabolites and the most similar BGCs in S. albidoflavus Q, determined with antiSMASH a

| Region | Type | Most similar BGCs | Percent of similarity | MIBiG BGC ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 | NPR-metallophore, NPRS | Griseobactin | 100 | BGC0000368 |

| 1.2 | Terpene, NRPS | Valinomycin/Montanastatin | 13 | BGC0001043 |

| 1.3 | T1PKS, NRPS | SGR PTMs/SGR PTM Compound b/SGR PTM Compound c/SGR PTM Compound d/ | 100 | BGC0001043 |

| 1.4 | Terpene | Hopene | 76 | BGC0000663 |

| 2.1 | NRPS-independent siderophore | Desferriozamine B | 100 | BGC0000941 |

| 3.1 | Terpene | Geosmin | 100 | BGC0001181 |

| 3.2 | Terpene | Julichrome Q3-3/Julichrome Q3-5 | 25 | BGC0002012 |

| 4.1 | Terpene | Isprenieratene | 75 | BGC0001456 |

| 4.2 | T3PKS | Valinomycin/ Montanastatin | 34 | BGC0001846 |

| 4.3 | T1PKS | Candicidin | 33 | BGC0000034 |

| 6.1 | NRPS, T2PKS | Fredericamycin A | 93 | BGC0000224 |

| 7.1 | Lanthipeptide class III | AmfS | 80 | BGC0000496 |

| 9.1 | NRPS | Cyclofaulkamycin | 75 | BGC0002358 |

| 10.1 | T1PKS, NRPS, Lanthipeptide class II | Candicidin | 95 | BGC0000034 |

| 12.1 | Ectoine | Ectoine | 100 | BGC0000853 |

| 20.1 | LAP, NRPS | Surogamide A/Surogamide D | 63 | BGC0001792 |

| 28.1 | NPRS | Surogamide A/Surogamide D | 57 | BGC0001792 |

BGC, biosynthetic gene cluster; MIBiG BGC ID, minimal information for the identification of a biosynthetic gene cluster; NRPS, non-ribosomal peptide synthetase; LAP, linear azol(in)e-containing peptides; T1PKS, type 1 polyketide synthase; T2PKS, type 2 polyketide synthase; T3PKS, type 3 polyketide synthase.

Docking study of the secondary metabolites identified as potential inhibitors of CgHMGR

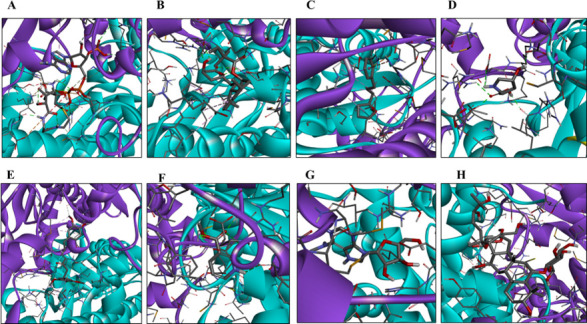

A coupling analysis was performed to test the hypothesis of possible interactions between the antifungal metabolites of S. albidoflavus Q and CgHMGR. The results show low binding energy values (reflecting a high affinity between the ligands and the protein), which would explain the inhibition of enzyme growth and, likewise, the decrease in ergosterol levels as well as alterations in the cytoplasmic membrane. First, the structure of the protein (CaHMGR) was built in 3D and then verified. The theoretical model was validated with a Ramachandran plot for C. albicans HMGR (CaHMGR) and CgHMGR. Of the total amino acids, those in the favorable region constituted 90.1% and 93.1%, respectively, which indicates good reliability of the structure (Fig. S2). Subsequently, the 3D structures were used for docking studies to explore the recognition of CgHMGR by the secondary metabolites. The 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-CoA substrate (HMG-CoA) of the HMGR enzyme was docked with a known inhibitor, simvastatin, as the binding control. The theoretical interaction of each secondary metabolite with CgHMGR is expressed as the binding energy (the values are listed in Table 5). The schematic binding mode of the ligands with the enzyme is illustrated in Fig. 9. Isogingerenone B was the metabolite with the highest binding energy. Its binding to the enzyme was based on hydrogen bonding, Van der Waals forces, and π-sigma, π-anion, and alkyl interactions. Notoginsenoside J showed the second highest binding energy, followed by N6,N6-dimethyladenosine.

TABLE 5.

Docking results of the binding mode between metabolites produced by S. albidoflavus Q at the catalytic site of the CgHMGR enzyme a

| Molecules | Bindig energy (kcal/mol) | Interacting residues | Interactions |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl CoA (HMG-CoA) |

−9.1 | Asn A: 810, Ile A: 956, Gly A: 919, Gln A: 920, His B: 906, Asn B: 909, Leu B: 1013, Asn A: 810 | Conventional hydrogen bond |

| Cys A: 678, Ala A: 677, Thr B: 710, Gly A: 808, Met A: 811, Gly A: 957, Gly A: 959, Gly A: 954, Met A: 807, Asp A: 921, Val A: 953, Thr A: 960, Ser A: 813, Met A:809, Ala B: 1007, Ser B: 717, Lys A: 845, Asp A:844, Leu B: 1004, Leu B: 1008, Leu B: 714, His B: 1012, Val B: 1014. | Van der Waals | ||

| Gly A: 958, Cys B: 713. | Carbon-hydrogen bond | ||

| Glu B: 711, Gln B: 1015, Lys B: 889, Arg A: 742. | Attractive charge | ||

| Ala A: 806. | Pi-Alkyl | ||

| Simvastatin | −8.2 | Asn A: 810, Asn B:909, Asp A: 844, Arg A: 742. | Conventional hydrogen bond |

| Cys B: 713, Leu B: 1013, Ala B: 1007, Leu B 1004 | Alkyl | ||

| Val B: 1014, Gly B: 712, Gln B:1015, Leu B: 714, Glu B: 711, Ser B:717, His B: 906, Lys A: 846, Lys A: 845, Ala B:905, Ser A: 838, Met A: 809, Ser A: 209. | Van der Waals | ||

| 2-(3-Phenylpropyl)-tetrahydrofuran (Compound 1) | −6.2 | Lys B: 889, Lys A: 846, Ala B:905, Lys A: 845, Asn B: 909, Glu B: 711, Leu B: 714, Ser B: 717, Cys B: 713, Gly B: 712, Leu B: 1013, Ser A: 838 | Van der Waals |

| Arg A: 742, Asp A: 844 | Pi Anion/Cation | ||

| Leu B: 1004 | Pi-sigma | ||

| His B: 906, Leu B: 1004 | Alkyl | ||

| 4-Hydroxy-3,4-dihydro-2H-pyrrole-2-carboxylic acid (Compound 2) |

−5.4 | Lys B: 889, Lys A: 846, Leu B: 1004, His B: 906, Lys A: 845, His B: 906, Lys A: 845, Asn B:909, Leu B: 1013. | Van der Waals |

| Ser A: 838, Ala B: 905, Arg A: 742, Asp A: 844, Glu B: 711 | Conventional hydrogen bond | ||

| Isogingerenone B (Compound 3) | −8.3 | Asn B: 909, His B: 906, Arg A: 742 | Conventional hydrogen bond |

| Lys A: 845, Ser A: 838, Asp A: 844, Asp A: 921, Thr B: 710, Thr A: 960, Gly A: 919, Gly A: 957, Gly A: 958. | Van der Waals | ||

| Leu B: 714, Leu B: 1004, Met A: 809, Met A: 807. | Alkyl | ||

| Leu B: 1013 | Pi-Sigma | ||

| Glu B: 711 | Pi-Anion | ||

| Methyl nicotinate (Compound 4) | −5.8 | Tyr A: 630, Val A: 682, Asn A: 681 | Conventional hydrogen bond |

| Glu A: 630, Arg A: 646, Tyr A: 671, Phe A: 675, Glu A: 680, Gly A: 676, Cys A: 679, Val A: 674. | Van der Waals | ||

| N6, N6-dimethyladenosine (Compound 5) | −7.6 | Asp A: 844, Lys B: 889, Ala B: 905. | Conventional hydrogen bond. |

| Glu B: 711, Leu B: 1013, Gly B: 712. | Carbon-hydrogen bond | ||

| His B: 906, Ser A: 838, Leu B: 1008, Asn A: 840, Arg A: 742, Leu B: 1004, Arg A: 742, Met A: 809*, Ser A: 813. Asn A: 810*, Cys B: 713, Asn B: 909, Lys A: 845, His B: 906. | Van der Waals | ||

| Notoginsenoside J (Compound 6) | −7.8 | His B: 1012, Ser B: 717, Cys B: 713 | Conventional hydrogen bond |

| His B: 876 | Pi-donor hydrogen bond | ||

| Arg B: 720, Ser B: 1003, Leu B: 1004, Ala B: 1007, Leu B: 1013, Gln B: 1015, Met B: 719, Ala B: 716, Tyr A: 630, Asn A: 681, Glu A: 633, Phe A: 675, Lys A: 679, Gly A: 676, Ala A: 677. Gly B: 712, Lys B: 876, | Van der Waals |

The binding energy is expressed as kCal/mol (ΔG). HMG-CoA, the natural substrate of the enzyme HMGR, and simvastatin were used as binding controls. Modeling analysis of the CgHMGR protein suggests a dimer conformation. The marked aa correspond to the A or B chain of the dimer. The aa belonging to the ENVIG dimerization motif are indicated in bold, the aa of the EGCLVAS substrate binding motif are underlined, and the aa of the DAMGMN* cofactor binding motif are indicated with an asterisk.

Fig 9.

For each of the metabolites identified as potential inhibitors of HMGR, a schematic illustration portrays the binding mode of the ligand with the CgHMGR enzyme. The predicted binding mode of HMG-CoA (A), simvastatin (B), compound 1 (C), compound 2 (D), compound 3 (E), compound 4 (F), compound 5 (G), and compound 6 (H). The α-helix and β-strand structures are depicted as ribbons, colored in cyan (subunit a) and purple (subunit b). The amino acids that interact with the ligand and the ligand itself are represented as sticks. The figure was created by Celia-Esthela Bautista-Crescencio with Discovery Studio 2021 client software.

DISCUSSION

The emergence of multidrug-resistant strains of fungi and their ability to cause nosocomial outbreaks of infection in immunocompromised patients has become an increasingly severe problem. Another global challenge that has emerged in the last couple of years is the appearance of polymicrobial infections (viruses, bacteria-fungi) associated with SARS-Cov-2/COVID and HIV/AIDS (2, 26). The emergence of drug-resistant strains of Candida is particularly problematic due to the limited existing treatment options, consisting of only a few antifungal drug families (27). The discovery of new antifungals with alternative therapeutic targets should contribute to the mitigation of these problems.

Regarding antifungal metabolites from actinobacteria, some are already clinical drugs (e.g., amphotericin B, nystatin, and natamycin) (Table 1). The development of new antifungal compounds derived from microorganisms faces the challenge of defining the chemical structure of such molecules as well as their therapeutic target and binding mode. Moreover, the identification of species of Streptomyces strains capable of generating antifungal metabolites can be complicated by the necessity of examining more than four molecular markers (28). The latter problem has been resolved with phylogenomic analysis, which is based on whole-genome sequencing (WGS) with a 92-gene core. By means of this technique, S. albidoflavus was established as the species of Streptomyces Q responsible for producing the present antifungal compounds.

Since one of the objectives of this study was to search for inhibitors of the HMGR enzyme, a growth recovery assay was carried out to try to infer which block of enzymes of the ergosterol synthesis pathway is involved in the inhibition caused by the S. albidoflavus Q metabolites (Fig. 1). The growth recovery of C. glabrata with mevalonate, squalene, and ergosterol suggests that the S. albidoflavus Q metabolites affect the first module of the ergosterol biosynthetic pathway (Fig. 1) (21, 23, 24, 29). C. albicans ATCC 10231 did not show growth recovery with ergosterol, perhaps because of the distinct sterol uptake responses between yeasts like Schizosaccharomyces pombe, C. glabrata, and C. albicans (30). On the contrary, the difference between the C. glabrata CBS 138 and CGL 43 strains in regard to growth recovery with mevalonate might be associated with the distinct genetic background of the two strains, the first of which is susceptible and the second is resistant to fluconazole (23). The regulation of the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway could vary from one Candida species to another (24, 30).

Considering the growth recovery with mevalonate, the decrease in ergosterol levels (Table 2), and the alteration of the cytoplasmic membrane of C. glabrata, the secondary metabolites produced by S. albidoflavus Q likely act by inhibiting the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway and in particular the CgHMGR enzyme (31). The latter enzyme is a key and limiting step in ergosterol synthesis (32) (Fig. 1).

Therefore, a selection process was carried out to identify the probable candidates for the inhibition of ergosterol among the 66 compounds identified by LC-HRMS metabolomic analysis. Six compounds with the greatest probability of interacting with the CgHMGR enzyme were selected as possible inhibitors by using the Way2Drug server (http://way2drug.com/passonline/) (Fig. 8). These secondary metabolites were tested in silico for their capacity to bind to the CgHMGR enzyme. According to the docking study (Fig. S1), the secondary metabolites isogingerenone B (compound 3) and notoginsenoside J (compound 6) interact with CgHMGR with high binding energy.

Isogingerenone B produced by Zingiber officinale was proposed in a previous report as a potential antifungal compound (33). However, the molecular target was not explored and its antifungal activity was not evaluated in Candida strains resistant to azoles.

In another study, molecular modeling analysis suggested that isogingerenone may bind to the fatty acid synthase enzyme, a marker protein in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (34). It has also been documented that this compound acts preferentially on senescent cells and thus has senolytic activity (35). Finally, isogingerenone B has the structure of a diarylheptanoid (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Gingerenone-B), closely related to the structures of curcumins and flavonoids. The applications of the latter compounds of plant origin have been widely documented in medicine and food processing (36). Overall, this evidence warrants further research on the pharmaceutical applications of isogingerenone B derived from S. albidoflavus Q.

The S. albidoflavus Q strain was herein isolated from rhizospheric maize soil in Mexico (37). Although the role of S. albidoflavus Q metabolites in the ecology of the bacterium is outside of the scope of the current contribution, there is a relevant precedent: the relation of antifungal compounds of Streptomyces griseus with the control of the phytopathogenic fungus Fusarium. S. griseus S4–7 was initially isolated from the strawberry rhizosphere as a microbial agent responsible for suppressing Fusarium wilt in soil (38). Among the genes of S. griseus proposed to participate in the antifungal activity against Fusarium are those linked to the synthesis of diarylheptanoid and gingerol, compounds closely related to the chemical structure of isogingerenone B of S. albidoflavus Q. Thus, it would be interesting to investigate the effect of antifungal S. albidoflavus Q metabolites on phytopathogenic fungi of maize. In this sense, there are reports on polyphenolic metabolites of Streptomyces clavuligerus (associated initially with plants) and their possible biosynthetic routes, identified through genetic engineering techniques and special conditions for expressing some cryptic genes (39).

Notoginsenoside J (compound 6), the other S. albidoflavus Q metabolite identified as a potential antifungal agent, has been previously evaluated for antioxidant (40), anti-tumor, anti-fatigue, anti-inflammatory (41), and anti-atherosclerosis activities (42). However, the molecular target of notoginsenoside is unknown (43). According to the present analysis, the CgHMGR enzyme is a plausible target. Notoginsenoside J is a glycosylated triterpenoid with a chemical structure similar to the Streptomyces hopanoids (44, 45). Polycyclic triterpenes, members of the terpene family, are synthesized by the cyclization of squalene, and the biosynthesis pathway is highly conserved in bacteria and certain eukaryotes (46). Hence, it would not be surprising if the production of hopanoids and notoginsenosides share some enzymes of the same biosynthesis pathway. The biosynthesis pathway of triterpenoids in actinobacteria has been defined and is related to the mevalonate pathway (47). Some genes involved in this pathway have been identified in S. avermitilis (https://www.genome.jp/kegg-bin/show_pathway?sma00909). The enzymes that putatively participate in the glycosylation of triterpenoids in S. clavuligerus have also been described (39). The BGCs contained in S. albidoflavus Q were herein analyzed to explore their biosynthetic capacity by matching them with the metabolites detected in this study (Table 4). Subsequently, some putative terpenoid pathways in the S. albidoflavus Q genome were established with the antiSMASH tool. A putative squalene cyclase was identified and related to the biosynthesis of hopenes in the S. albidoflavus Q genome (https://mibig.secondarymetabolites.org/repository/BGC0000663/index.html#r1c1).

On the contrary, it has been observed in yeasts (as in mammals) that sterol synthesis is highly regulated at the transcription, translation, and post-translation levels, as is the inhibition of sterols by the intermediate or final products of the enzymatic activity of the biosynthesis pathway (Fig. 1) (24, 31). Therefore, it would be interesting to examine the role of triterpenoids from S. albidoflavus Q in regulating the enzymes involved in the synthesis of ergosterol in yeasts and in the regulation of triterpenoid synthesis in actinobacteria.

Isogingerenone and notoginsenosides have been associated mainly with plants (33, 43), but compounds such as coumarins have also been identified in the extracts of Streptomyces spp. by metabolomic analyses (48). Naringenin, another antifungal compound that was initially known for its plant origin, is generated by Streptomyces clavuligerus (39, 49).

In the current in silico study, N6,N6-dimethyladenosine (compound 5) showed the third highest binding free energy when docked with CgHMGR. It has been used as an inhibitor of AKT signaling in various lung cancer cell lines (50). In Actinomycete Mycobacterium bovis, this molecule may be responsible for the post-transcriptional modification of tRNAs (51). Further research is necessary on N6,N6-dimethyladenosine considering the scant number of reports on this molecule in the literature. The possible interaction of this metabolite with the amino acids of the NADPH cofactor binding motif of the CgHMGR protein is discussed below.

The docking analysis of six S. albidoflavus Q metabolites gives important clues as to their binding mode (Table 4). The three most conserved motifs for the protein of fungal HMGR enzymes are ENVIG dimerization (680–684 residues), EGCLVAS substrate binding (711–717 residues), and cofactor DAMGMN binding (807–812 residues). The role of these amino acids in the activity of CgHMGR has also been assessed through the evaluation of point mutants in each of the enzyme motifs (22).

Methyl-nicotinate (compound 4) might affect the dimerization of CgHMGR given its interaction with the amino acid residues of the ENVIG dimerization motif of the enzyme. 2-(3-Phenylpropyl)-tetrahydrofuran, 4-hydroxy-3,4-dihydro-2H-pyrrole-2-carboxylic acid, isogingerenone B, and notoginsenoside J (compounds 1, 2, 3, and 6, respectively) may interact with the amino acid residues of the EGCLVAS substrate-binding domain, as well as with the control molecules HMG-CoA (an HMGR substrate) and simvastatin (an HMGR inhibitor).

The docking analysis suggests that the secondary metabolite N6,N6-dimethyladenosine (compound 5) interacts with some amino acids of the DAMGMN cofactor-binding motif of the enzyme (22). Hence, this compound could possibly compete with NADPH, the natural cofactor of the enzyme. Regarding compound 2, synthetic substituted pyrroles are known to act as antifungals by inhibiting CgHMGR activity and ergosterol synthesis (23).

There are few reports on the strains of S. albidoflavus that produce antifungal metabolites. The S. albidoflavus C247 strain was isolated from soil samples in Korea, but its identification was based only on the sequence of the 16S rDNA molecular marker, and its antifungal activity was determined by inhibition of the formation of Rhizoctonia solani mycelium (52). A non-polyene antifungal antibiotic from S. albidoflavus PU 23 was also described (53).

Since ergosterol is an essential constituent of the fungal plasma membrane (54), the inhibition of one or more key enzymes of the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway has been considered as an important element for antifungal drugs (24). Squalene epoxidase (Erg 1) targets allylamines, a noncompetitive inhibitor (55). Azoles, the most common antifungal for treating invasive fungal infections, target the lanosterol 14 alpha-demethylase enzyme (Erg11) (56). Polyenes interact with the ergosterol surface and form pores in the plasmatic membrane (57). Micrographs of the cytoplasmic membrane of C. glabrata treated with sublethal concentrations of the supernatant of S. albidoflavus Q evidence alterations in the cytoplasmic membrane of the yeasts, similar to those caused by fluconazole, an ergosterol inhibitor (56, 58).

According to the results of the current contribution, CgHMGR is probably the molecular target of antifungal S. albidoflavus Q metabolites, which inhibited the growth of C. glabrata, diminished its ergosterol synthesis, and altered its cytoplasmic membrane. These metabolites were identified and used in molecular modeling, which showed their interaction with the CgHMGR enzyme.

In the future, it will be necessary to carry out metabolomics studies on yeasts treated with S. albidoflavus purified metabolites capable of inhibiting the HMGR enzyme or other enzymes of the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway. The synthesis of sterols in mammals and yeasts is a highly regulated process through all stages of the flow of genetic information and at the biochemical level (32). Metabolomic studies on the effect of fluconazole treatment of C. albicans have shown an increase in the central carbon and a decrease in the synthesis of intermediate amino acids, suggesting a rerouting of metabolic pathways. The function of these metabolomic changes is still not clear. As aforementioned, they may represent previously unrecognized mechanisms of the metabolic alteration of C. albicans induced by fluconazole (59).

The metabolites present in the supernatant of S. albidoflavus Q did not show toxicity, according to the Galleria mellonella model currently used. However, it will be necessary to evaluate possible toxicity when the compounds with antifungal activity have been purified and their activity and potency verified.

Conclusion

The species of actinobacteria isolated from rhizospheric maize soil was identified as S. albidoflavus. The genome of S. albidoflavus Q exhibited characteristics typical of an actinobacterial genome: a high percentage of G+C and linear topology. The sequence herein generated and deposited in the Genbank (PRJNA886754) will allow for further analysis of the WGS. The biosynthetic pathways of the metabolites of interest can then be established through metabolic engineering, expression analysis, and the development of mutants to verify the genes involved in the synthesis of the antifungal compounds.

It was presently demonstrated that S. albidoflavus Q produces secondary metabolites with antifungal activity, evidenced by reduced yeast viability, decreased ergosterol level, and alterations in the yeast cytoplasmic membrane ultrastructure. Such effects are carried out by targeting the ergosterol pathway and probably the HMGR enzyme. This conclusion is based on the decrease in the level of ergosterol and the posterior growth recovery of Candida spp. with mevalonate, squalene, and ergosterol. The secondary metabolites isogingerenone B (compound 3) and notoginsenoside J (compound 6) interact in silico with the substrate-binding EGCLVAS motif of the CgHMGR protein with high binding energy, supporting the in vitro experimental results.

After identifying potential antifungal compounds, their rational design involves chemical modifications to achieve more potent, more target-specific, and less toxic molecules, followed by their in vitro testing on Candida species. Subsequently, the derivatives can be examined for their safety, toxicity, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics, and finally tested in clinical trials.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strain and culture media

The Streptomyces Q strain belongs to a collection of around 300 isolates of actinobacteria from different soils and Mexican plants, which is stored in the Molecular Biology of Bacteria and Yeast Lab of the Escuela Nacional de Ciencias Biológicas of the Instituto Politécnico Nacional in Mexico. This strain was selected for its ability to inhibit the growth of C. glabrata.

S. albidoflavus Q was grown in GAE medium (2% glucose, 1% asparagine, 0.5% yeast extract, 0.5% K2HPO4, 0.5% MgSO4, and 0.01% FeSO4) for 15 days at 28°C under constant agitation at 250 rpm. Subsequently, the biomass was separated by centrifugation at refrigeration temperature, and the supernatant was lyophilized. The resulting supernatant was solubilized in sterilized ultrapure MilliQTM water and then concentrated at 100 mg/mL (wt/vol). The morphology and purity of the colony of Streptomyces Q were verified on solid GAE medium (2% bacteriological agar).

C. glabrata CBS 138 and CGL 43 (phenotypes susceptible and resistant to fluconazole, respectively) were employed to examine the antifungal effect and ergosterol inhibition promoted by the S. albidoflavus Q metabolites. The C. glabrata CBS138 used in this study was kindly provided by Bernard Dujon from the Instituto Pasteur-Paris. C. glabrata CGL 43 belongs to the collection of our laboratory and was isolated from a patient with HIV from the Civil Hospital of Guadalajara and donated by Dr. Fernando Velarde Rivera. On the contrary, C. albicans ATCC 10231 and C. krusei ATCC 14423 served as the control of susceptibility and resistance to fluconazole, respectively. The yeasts were grown in extract-peptone-dextrose YPD liquid yeast medium (1% yeast extract, 2% dextrose, and 2% casein peptone) at 37°C under constant agitation at 250 rpm. The strains were stored at –70°C in 50% (vol/vol) anhydrous glycerol (Sigma-Aldrich) to await the testing of the metabolites as fungal inhibitors.

Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) of Streptomyces albidoflavus sp Q and phylogenetic analysis

After the S. albidoflavus Q strain was grown, the DNA was extracted with the Zymo Research Soil Microbe DNA Miniprep kit. The whole-genome sequencing was performed by using Illumina Hiseq4000 (Novogene, Sacramento, CA, USA). The reads underwent trimming with Trimmomatic (60) before conducting a search for the sequences of the PhiX phage in the genome of the Streptomyces Q (61). The genome was assembled on SPAdes software (62), and the assembly quality was evaluated with the QUAST program (63).

The phylogenomic tree of Streptomyces spp. was created by aligning 92 genes (core genome) on UBCG software (64). The genome sequences of the following strains were taken as an outgroup from NCBI: S. albidoflavus strain DSM 40455 (NZ_PKLO01000004.1), S. albidoflavus strain J1074 (CP004370.1), S. albidoflavus strain J1074/R2 (GCA_013693715.1), S. albidoflavus strain NBRC 100770 (PKLL01000003.1), S. albidoflavus strain NBRC 12790 (PKLN01000043.1), S. albidoflavus strain R-53649 (FWFA01000334.1), S. albidoflavus strain SM254 (NZ_CP014485.1), S. albovinaceus strain NRRL B-2566 (NZ_MUAX01000001.1), S. albus strain NBRC 13014 (NZ_BBQG01000095.1), S. antibioticus strain DSM 41481 (NZ_CM007717.1), S. aquilus strain GGCR-6 (NZ_CP034463.1), S. argenteolus strain 3259 Ga0365441_101 (NZ_VIWQ01000001.1), S. aureus strain NRRL B-2808 (NZ_LIPQ01000001.1), S. bobili strain NRRL B-1338 (NZ_MUBA01000001.1), S. fungicidicus strain TXX3120 (NZ_CP023407.1), S. finlayi strain NBSH44 (NZ_CP045702.1), S. globisporus C-1027 (NZ_CP013738.1), S. hygroscopicus strain XM201 (NZ_CP018627.1), S. hygroscopicus subsp. hygroscopicus strain OsiSh-2 (NZ_MDFG01000001.1), S. kanamyceticus strain ATCC 12853 (NZ_CP023699.1), S. lividans TK24 (NZ_CP009124.1), S. mediolani strain NRRL WC-3934 (NZ_JOJK01000001.1), S. microflavus strain CG 893 (NZ_OAOR01000042.1), S. mutomycini strain NRRL B-65393 (NZ_MAPV01000001.1), S. niveus strain SCSIO 3406 (NZ_CP018047.1), S. noursei ATCC 11455 (NZ_CP011533.1), S. rimosus strain ATCC 10970 (NZ_CP023688.1), S. sporangiiformans strain NEAU-SSA 1 C1723 (NZ_VCHX02000184.1), S. tsukubaensis strain NRRL 18488 (NZ_CP029197.1), S. venezuelae ATCC 10712 (NZ_CP029197.1), and Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv (NC_000962.3).

Prediction of the biosynthetic gene clusters that encode the metabolites

Specialized metabolite biosynthetic gene clusters M-BGC were predicted with antiSMASH 4.0. c (65).

Antifungal activity of the lyophilized supernatant of S. albidoflavus Q on Candida spp.

The modified microplate dilution method described by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) was used to determine the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of the lyophilized supernatant of S. albidoflavus Q (23, 66). Briefly, stock solutions were prepared with the lyophilized supernatant in RPMI 1640 medium (Sigma-Aldrich). The yeasts were then grown in YPD liquid yeast medium at 37°C for 24 h. The pre-inoculum OD620 = 0.6 was established before performing serial 1:1,000 dilutions to obtain the inoculum. Solutions of the supernatant or fluconazole (the inhibition control) were placed in microplates and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. The absorbance was read in a Thermo Scientific Multiskan FC microplate spectrophotometer at 620 nm (23).

Antifungal activity of S. albidoflavus supernatant by disk diffusion

Yeast antifungal susceptibility was tested by disk diffusion in SDA medium. Fluconazole and water were used as the inhibition control and non-inhibition control, respectively. Sub-lethal concentrations were tested in the disks. The yeast was incubated at 37°C for 24 h, according to the CLSI protocol (modified) (https://clsi.org/standards/products/microbiology/documents/m44/).

Candida spp. growth recovery with mevalonate, squalene, and ergosterol

A growth recovery experiment was carried out to verify that the lyophilized supernatant affects yeast viability by inhibiting ergosterol biosynthesis. Another objective of this experiment was to try to infer the enzyme or block of enzymes inhibited by the metabolites present in the supernatant of Streptomyces Q. Thus, the yeasts were treated with sublethal concentrations (MIC70-90, determined by the CLSI M27-A3 protocol) of an inhibitor, followed by the addition of mevalonate, squalene, or ergosterol (Fig. 1). Briefly, to each well of the microplates was added the concentration corresponding to the MIC70-90 of each inhibitor (the lyophilized supernatant of S. albidoflavus Q or fluconazole), which was elaborated with 80 µL of a yeast suspension adjusted to 1 to 5 × 106 UFC/mL and diluted 1:1,000 with RPMI 1640 medium (Sigma-Aldrich). Next, a stock solution was prepared for each of the growth recovery compounds (mevalonate, squalene, and ergosterol; Sigma-Aldrich) by dissolving 120 µg/mL in Tween 80/ethanol (1:1) (Sigma-Aldrich). Subsequently, 20 µL of this solution was added to each well, resulting in a final concentration of 6, 3, or 1.5 µg/mL of mevalonate, squalene, or ergosterol, respectively. The controls consisted of yeast cultures treated with the vehicle only (in the absence of any antifungal compound, the growth control) and those treated with an antifungal but without sterol (the growth recovery control) (23).

The statistical analyses were performed, and graphs were constructed with GraphPad Prism 5.0. After calculating the mean of three replicates ± SD, differences between groups were examined with two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), using the Bonferroni correction and a 95% confidence interval. Statistical significance was considered at P < 0.001 (22, 23, 29).

Quantification of ergosterol in Candida spp.

Total sterols were extracted with a slightly modified version of the methodology reported by the authors of the references (67, 68, 68). Briefly, Candida spp. yeasts were grown in YPD yeast medium by incubation at 28°C for 24 h under constant agitation at 200 rpm. The cell culture was prepared by adjusting it to an optical density of 0.3 (AS620) in a different flask containing 5 mL of YPD yeast medium and then adding ultrapure MilliQTM water to control the lyophilized supernatant (IC70-90). Simvastatin and fluconazole served as the inhibition controls. For each treatment, both yeasts were incubated at 37°C for 18 h under constant shaking at 200 rpm. The cells were harvested by centrifugation and washed with sterile distilled water. Subsequently, each tube was adjusted to 100 mg of total yeast cells (wet weight) before adding 3 mL of an alcoholic potassium hydroxide solution (25 g of KOH and 35 mL distilled water, brought to 100 mL with absolute ethanol) in a vortex for 1 min to extract the sterols. The cell suspensions were incubated at 85°C for 1 h. The sterols were extracted with 1 mL of sterile distilled water and 2 mL of n-heptane by vigorously mixing the solution in a vortex for 3 min. The n-heptane layer was spectrophotometrically scanned between 230 and 300 nm (BioSpectrometer, Eppendorf). The presence of ergosterol (the As281.5 peak) and 24 dihydroxy-ergosterol (the As230 peak) [24 (28) DHE], a late intermediate, can be appreciated by the characteristic four-peaked spectrum indicating sterol absorption. This technique is also able to reveal a decrease in the level of ergosterol. The absence of detectable levels is evidenced by a flattening of the curve (23, 67 – 69).

Transmission electron Microscopy of Candida glabrata

The antifungals at MIC70-90 were added to the culture media of C. glabrata CBS 138 and CGL43. Untreated cells served as the control for healthy membrane maintenance, and cells treated with fluconazole served as the control of cellular damage. The cells were centrifuged and washed twice with PBS Sörensen, then fixed by incubation with 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 1 h, post-fixed with 1% OsO4 in PBS at 4°C for 30 min, thoroughly washed with PBS, gradually dehydrated in an increasing ethanol series, and embedded in Spurr resin. The resin was polymerized at 60°C for 24 h and sectioned on an ultramicrotome Leica Ultracut R apparatus (Leica Microsystems, Heidelberg, Germany). The sections were recovered on copper grids, stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and examined under a Jeol 2000EX transmission electron microscope (Jeol, Tokyo, Japan) at 80 kV (70).

Metabolomic analysis with UHPLC-MS/MS data acquisition

For the UHPLC/Q-TOF-MS study, about 10 mg of the lyophilized supernatant of S. albidoflavus strain Q was placed in an Agilent 1290 Infinity II system coupled with a 6545A Q-TOF with a dual AJS ESI source (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), which was used in the positive mode in a standard mass range (m/z 3,200). The elution was carried out at 25 ± 0.5°C by using water (solvent A) and methanol (solvent B) with the following gradient: 100%A from 0 to 7 min, 40%A from 7 to 10 min, and 100%A with a 3 min re-equilibration time. The flow rate of the mobile phase was 0.6 mL/min with an injection volume of 20 µL for each sample. The organic phase was separated in an Agilent Zorbax AQUA, 4.6 × 150 mm2 column for 5 µM particles. During all LC-MS/MS analyses, samples were kept at 4°C. The raw data obtained by UHPLC/Q-TOF-MS/MS were converted into mzData by means of Agilent MassHunter Workstation Software Qualitative Analysis, version B.07.00, build 7.7.7024.29 SP2 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The parameters selected were those available for a UHPLC/UHD Q-TOF MS/MS, which included an m/z tolerated deviation of 15 ppm, a peak width from 5 to 20 s, a signal/noise threshold of 6, and an mzdiff of 0.01, mzwid of 0.015, bw of 5, and minfrac and minsamp of 0.5 and 1, respectively (71).

The secondary metabolites identified were analyzed for possible biological activity with the web resource PASS Online deposited in Way2Drug server (http://way2drug.com/passonline/) (72). Way2drug is a resource made up of various web services that are useful for the prediction of bioactivity of low molecular weight organic compounds. By simply drawing the chemical structure or entering the InChI code or Smiles code, the program performs the calculations of two parameters, Pa and Pi, that represent the probability of activity and inactivity of a compound, respectively. It is based on the local correspondence premise, according to which the biological activity of a drug-like organic compound may have effects similar to other compounds with a like structure. Using this concept, they developed a consistent system of neighborhood-focused atom descriptors including MNA Way2drug has been implemented in various SAR/QSAR/QSPR modeling approaches (72).

Docking of the secondary metabolites identified as potential inhibitors of CgHMGR

Homology modeling was performed by the Swiss-Model server (73), utilizing the sequence of HMGR of C. glabrata (Cg-HMGR, NCBI accession number XP_449268.1) and the crystallographic structure of human HMGR as a template (PDB entry 1DQ9, resolution 2.8 Å). The quality of the model was evaluated by determining the stereochemical restrictions with the Ramachandran plot constructed on PROCHECK (74). The protein preparations were obtained by following a standard protocol for the removal of co-crystallized ligands and water molecules. Polar hydrogens were added for all receptor atoms and computed to assess hydrogen-bonding interactions. All the other parameters were kept at their default settings (75). The structure was energetically minimized and equilibrated by means of molecular dynamic simulations on Autodock tools. The three-dimensional structure of the ligands was drawn in ChemSketch (www.acdlabs.com) and then subjected to energy optimization and minimization with GaussView 5.0 (76). The catalytic pocket was calculated with the server CASTp (http://sts.bioe.uic.edu/castp/index.html?3trg) (77). The ligands were docked at each receptor using a grid box of 36 Å3 centered in the catalytic pocket. The grid center for both proteins was X = 25.244 Å, Y = 12.841 Å, and Z = 7.184 Å. Docking results were computed in Autodock Vina (78) based on an exhaustiveness of four hundred one mode. The docking controls were HMG-CoA (the enzyme substrate) and simvastatin (an inhibitor of HMGR).

Toxicity of the supernatant in the Galleria mellonella model

The toxicity test began by injecting an initial dose of the supernatant (5 mg/kg body weight) into five larvae. Larva mortality was recorded daily for five days. If three or more larvae died, the compound was assigned to the highest class of toxicity (GHS 1). If three or more larva survived, the initial dose was retested on a new group of larvae. If three or more larvae were again found to survive, a higher dose (25 mg/kg body weight) was tested. The experiment continued until a toxic dose was established. If the compound was not toxic at the highest dose (2,000 mg/kg), the compound was established as nontoxic (79). Isotonic saline solution was used as the control of nontoxicity and DMSO as the control of toxicity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

C.B.-C. and A.C.-R. appreciate the graduate scholarship awarded by CONACyT and the scholarship complements furnished by the SIP-IPN (BEIFI). The authors acknowledge funding from SIP20231481, SIP20231480, SIP2022074, and SIP20220795 CONACyT 283225.

J.C.-B., C.H.-R., and L.V.-T. are fellows of the Estímulos al Desempeño de los Investigadores (EDI)-IPN and Comisión de Operación y Fomento de Actividades Académicas (COFAA)-IPN programs. M.J.F.-V. was hired at the IPN by the PICPAE recruitment program and is a fellow of the EDI-IPN.

We thank Bruce Allan Larsen for proofreading the manuscript. We are grateful to Dr. Edgar Oliver Lopez-Villegas from the Unidad de Microscopía de la Escuela Nacional de Ciencias Biológicas, del Instituto Politécnico Nacional, for his advice and help in the treatment of samples and obtaining microphotographs by TEM, and to M. en C. Alma Alicia Ortiz Morales from Laboratorio de Diseño y Desarrollo de Nuevos Fármacos e Innovación Biotecnológica (Laboratory for the Design and Development of New Drugs and Biotechnological Innovation), SEPI-Escuela Superior de Medicina del Instituto Politécnico Nacional, for her advice and treatment of samples for metabolomic analysis.

Conceptualization by L.V.-T. and C.H.-R.; writing-original draft preparation by C.B.-C. and L.V.-T.; writing-review and editing by C.B.-C., L.V.-T., and C.H.-R.; antifungal susceptibility test by C.B.-C.; phylogenetic analysis by C.B.-C.; docking analysis by C.B.-C. and A.C.-R.; WGS. analysis by C.B.-C., C.O., and C.H.-R.; metabolomics analysis by C.B.-C., M.J.F.-V., and J.C.-B; project administration by L.V.-T. and C.H.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

César Hernández-Rodríguez, Email: chdez38@hotmail.com.

Lourdes Villa-Tanaca, Email: mvillat@ipn.mx.

Edward Sionov, Agricultural Research Organization Volcani Center, Rishon LeZion, Israel .

DATA AVAILABILITY

The S. albidoflavus Q genome sequence generated was deposited in GenBank under BioProject number PRJNA886754 and annotation number GCA_025630915.1.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

The following material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1128/spectrum.01271-23.

Table S1, Fig. S1, and Fig. S2.

ASM does not own the copyrights to Supplemental Material that may be linked to, or accessed through, an article. The authors have granted ASM a non-exclusive, world-wide license to publish the Supplemental Material files. Please contact the corresponding author directly for reuse.

REFERENCES

- 1. Lai C-C, Chen S-Y, Ko W-C, Hsueh P-R. 2021. Increased antimicrobial resistance during COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Antimicrob Agents 57:106324. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2021.106324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pristov KE, Ghannoum MA. 2019. Resistance of Candida to azoles and echinocandins worldwide. Clin Microbiol Infect 25:792–798. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2019.03.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tortorano AM, Prigitano A, Morroni G, Brescini L, Barchiesi F. 2021. Candidemia: evolution of drug resistance and novel therapeutic approaches. Infect Drug Resist 14:5543–5553. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S274872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barka EA, Vatsa P, Sanchez L, Gaveau-Vaillant N, Jacquard C, Meier-Kolthoff JP, Klenk H-P, Clément C, Ouhdouch Y, van Wezel GP. 2016. Taxonomy physiology, and natural products of actinobacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 80:1–43. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00019-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Xu L, Ye K-X, Dai W-H, Sun C, Xu L-H, Han B-N. 2019. Comparative genomic insights into secondary metabolism biosynthetic gene cluster distributions of marine Streptomyces. Mar Drugs 17:498. doi: 10.3390/md17090498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nett M, Ikeda H, Moore BS. 2009. Genomic basis for natural product biosynthetic diversity in the actinomycetes. Nat Prod Rep 26:1362–1384. doi: 10.1039/b817069j [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Baba MS, Mohamad Zin N, Ahmad SJ, Mazlan NW, Baharum SN, Ahmad N, Azmi F. 2021. Antibiotic biosynthesis pathways from endophytic Streptomyces SUK 48 through metabolomics and genomics approaches. Antibiotics (Basel) 10:969. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10080969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ceniceros A, Cuervo L, Méndez C, Salas JA, Olano C, Malmierca MG. 2021. A multidisciplinary approach to unraveling the natural product biosynthetic potential of a Streptomyces strain collection isolated from leaf-cutting ants. Microorganisms 9:2225. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9112225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gavriilidou A, Kautsar SA, Zaburannyi N, Krug D, Müller R, Medema MH, Ziemert N. 2022. Compendium of specialized metabolite biosynthetic diversity encoded in bacterial genomes. Nat Microbiol 7:726–735. doi: 10.1038/s41564-022-01110-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bauman KD, Butler KS, Moore BS, Chekan JR. 2021. Genome mining methods to discover bioactive natural products. Nat Prod Rep 38:2100–2129. doi: 10.1039/d1np00032b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cuervo L, Méndez C, Salas JA, Olano C, Malmierca MG. 2022. Volatile compounds in actinomycete communities: a new tool for biosynthetic gene cluster activation, cooperative growth promotion, and drug discovery. Cells 11:3510. doi: 10.3390/cells11213510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. El-Hawary SS, Hassan MHA, Hudhud AO, Abdelmohsen UR, Mohammed R. 2023. Elicitation for activation of the actinomycete genome's cryptic secondary metabolite gene clusters. RSC Adv 13:5778–5795. doi: 10.1039/d2ra08222e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Campoy S, Adrio JL. 2017. Antifungals. Biochem Pharmacol 133:86–96. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2016.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lu D, Ma Z, Xu X, Yu X. 2016. Isolation and identification of biocontrol agent Streptomyces rimosus M527 against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cucumerinum. J Basic Microbiol 56:929–933. doi: 10.1002/jobm.201500666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Belghit S, Driche EH, Bijani C, Zitouni A, Sabaou N, Badji B, Mathieu F. 2016. Activity of 2,4-Di-tert-butylphenol produced by a strain of Streptomyces mutabilis isolated from a Saharan soil against Candida albicans and other pathogenic fungi. J Mycol Med 26:160–169. doi: 10.1016/j.mycmed.2016.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Valanarasu M, Kannan P, Ezhilvendan S, Ganesan G, Ignacimuthu S, Agastian P. 2010. Antifungal and antifeedant activities of extracellular product of Streptomyces spp. ERI-04 isolated from Western Ghats of Tamil Nadu. J Mycol Med 20:290–297. doi: 10.1016/j.mycmed.2010.09.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vartak A, Mutalik V, Parab RR, Shanbhag P, Bhave S, Mishra PD, Mahajan GB. 2014. Isolation of a new broad spectrum antifungal polyene from Streptomyces sp. MTCC 5680. Lett Appl Microbiol 58:591–596. doi: 10.1111/lam.12229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bae M, Kim H, Moon K, Nam S-J, Shin J, Oh K-B, Oh D-C. 2015. Mohangamides A and B, new dilactone-tethered pseudo-dimeric peptides inhibiting Candida albicans isocitrate lyase. Org Lett 17:712–715. doi: 10.1021/ol5037248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Xu F, Nazari B, Moon K, Bushin LB, Seyedsayamdost MR. 2017. Discovery of a cryptic antifungal compound from Streptomyces albus J1074 using high-throughput elicitor screens. J Am Chem Soc 139:9203–9212. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b02716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Westermeyer C, Macreadie IG. 2007. Simvastatin reduces ergosterol levels, inhibits growth and causes loss of mtDNA in Candida glabrata. FEMS Yeast Res 7:436–441. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2006.00194.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Andrade-Pavón D, Sánchez-Sandoval E, Rosales-Acosta B, Ibarra JA, Tamariz J, Hernández-Rodríguez C, Villa-Tanaca L. 2014. The 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme-A reductases from fungi: a proposal as a therapeutic target and as a study model. Rev Iberoam Micol 31:81–85. doi: 10.1016/j.riam.2013.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Andrade-Pavón D, Ortiz-Álvarez J, Sánchez-Sandoval E, Tamariz J, Hernández-Rodríguez C, Ibarra JA, Villa-Tanaca L. 2019. Inhibition of recombinant enzyme 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase from Candida glabrata by α-asarone-based synthetic compounds as antifungal agents. J Biotechnol 292:64–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2019.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Madrigal-Aguilar DA, Gonzalez-Silva A, Rosales-Acosta B, Bautista-Crescencio C, Ortiz-Álvarez J, Escalante CH, Sánchez-Navarrete J, Hernández-Rodríguez C, Chamorro-Cevallos G, Tamariz J, Villa-Tanaca L. 2022. Antifungal activity of fibrate-based compounds and substituted pyrroles that inhibit the enzyme 3-hydroxy-methyl-glutaryl-CoA reductase of Candida glabrata (CgHMGR), thus decreasing yeast viability and ergosterol synthesis. Microbiol Spectr 10:e0164221. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.01642-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jordá T, Puig S. 2020. Regulation of ergosterol biosynthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes 11:795. doi: 10.3390/genes11070795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Elias D, Toth Hervay N, Jacko J, Morvova M, Valachovic M, Gbelska Y. 2022. Erg6p is essential for antifungal drug resistance, plasma membrane properties and cell wall integrity in Candida glabrata. FEMS Yeast Res 21:foac045. doi: 10.1093/femsyr/foac045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Noël de Tilly A, Tharmalingam S. 2022. Review of treatments for oropharyngeal fungal infections in HIV/AIDS patients. Microbiol Res 13:219–234. doi: 10.3390/microbiolres13020019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ksiezopolska E, Gabaldón T. 2018. Evolutionary emergence of drug resistance in Candida opportunistic pathogens. Genes 9:461. doi: 10.3390/genes9090461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Guo Y, Zheng W, Rong X, Huang Y. 2008. A multilocus phylogeny of the Streptomyces griseus 16S rRNA gene clade: use of multilocus sequence analysis for streptomycete systematics. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 58:149–159. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.65224-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Macreadie IG, Johnson G, Schlosser T, Macreadie PI. 2006. Growth inhibition of Candida species and Aspergillus fumigatus by statins. FEMS Microbiol Lett 262:9–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00370.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zavrel M, Hoot SJ, White TC. 2013. Comparison of sterol import under aerobic and anaerobic conditions in three fungal species, Candida albicans, Candida glabrata, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eukaryot Cell 12:725–738. doi: 10.1128/EC.00345-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Andrade-Pavón D, Cuevas-Hernández RI, Trujillo-Ferrara JG, Hernández-Rodríguez C, Ibarra JA, Villa-Tanaca L. 2017. Recombinant 3-hydroxy 3-methyl glutaryl-CoA reductase from Candida glabrata (rec-CgHMGR) obtained by heterologous expression, as a novel therapeutic target model for testing synthetic drugs. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 182:1478–1490. doi: 10.1007/s12010-017-2412-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Burg JS, Espenshade PJ. 2011. Regulation of HMG-CoA reductase in mammals and yeast. Prog Lipid Res 50:403–410. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2011.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Endo K, Kanno E, Oshima Y. 1990. Structures of antifungal diarylheptenones, gingerenones A, B, C and isogingerenone B, isolated from the rhizomes of Zingiber officinale. Phytochemistry 29:797–799. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(90)80021-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ghaeidamini Harouni M, Rahgozar S, Rahimi Babasheikhali S, Safavi A, Ghodousi ES. 2020. Fatty acid synthase, a novel poor prognostic factor for acute lymphoblastic leukemia which can be targeted by ginger extract. Sci Rep 10:20952. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-78089-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Moaddel R, Rossi M, Rodriguez S, Munk R, Khadeer M, Abdelmohsen K, Gorospe M, Ferrucci L. 2022. Identification of gingerenone A as a novel senolytic compound. PLoS One 17:e0266135. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0266135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ganapathy G, Preethi R, Moses JA, Anandharamakrishnan C. 2019. Diarylheptanoids as nutraceutical: a review. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol 19:101109. doi: 10.1016/j.bcab.2019.101109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rios-Galicia B, Villagómez-Garfias C, De la Vega-Camarillo E, Guerra-Camacho JE, Medina-Jaritz N, Arteaga-Garibay RI, Villa-Tanaca L, Hernández-Rodríguez C. 2021. The Mexican giant maize of Jala landrace harbour plant-growth-promoting rhizospheric and endophytic bacteria. 3 Biotech 11:447. doi: 10.1007/s13205-021-02983-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cho HJ, Kwon YS, Kim D-R, Cho G, Hong SW, Bae D-W, Kwak Y-S. 2017. wblE2 transcription factor in Streptomyces griseus S4-7 plays an important role in plant protection. Microbiologyopen 6:e00494. doi: 10.1002/mbo3.494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Shaikh AA, Nothias L-F, Srivastava SK, Dorrestein PC, Tahlan K. 2021. Specialized metabolites from ribosome engineered strains of Streptomyces clavuligerus. Metabolites 11:239. doi: 10.3390/metabo11040239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Li X, Lin H, Zhang X, Jaspers RT, Yu Q, Ji Y, Forouzanfar T, Wang D, Huang S, Wu G. 2021. Notoginsenoside R1 attenuates oxidative stress-induced osteoblast dysfunction through JNK signalling pathway. J Cell Mol Med 25:11278–11289. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.17054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Li Q, Wang L, Fang X, Zhao L. 2022. Highly efficient biotransformation of notoginsenoside R1 into ginsenoside Rg1 by Dictyoglomus thermophilumβ-xylosidase Xln-DT. J Microbiol Biotechnol 32:447–457. doi: 10.4014/jmb.2111.11020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zhu L, Gong X, Gong J, Xuan Y, Fu T, Ni S, Xu L, Ji N. 2020. Notoginsenoside R1 upregulates miR-221-3p expression to alleviate ox-LDL-induced apoptosis, inflammation, and oxidative stress by inhibiting the TLR4/NF-κB pathway in HUVECs. Braz J Med Biol Res 53:e9346. doi: 10.1590/1414-431x20209346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 43. Liu H, Yang J, Yang W, Hu S, Wu Y, Zhao B, Hu H, Du S. 2020. Focus on notoginsenoside R1 in metabolism and prevention against human diseases. Drug Des Devel Ther 14:551–565. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S240511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ghimire GP, Koirala N, Sohng JK. 2015. Activation of cryptic hop genes from Streptomyces peucetius ATCC 27952 involved in hopanoid biosynthesis. J Microbiol Biotechnol 25:658–661. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1408.08058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Seipke RF, Loria R. 2009. Hopanoids are not essential for growth of Streptomyces scabies 87-22. J Bacteriol 191:5216–5223. doi: 10.1128/JB.00390-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Santana-Molina C, Rivas-Marin E, Rojas AM, Devos DP. 2020. Origin and evolution of polycyclic triterpene synthesis. Mol Biol Evol 37:1925–1941. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msaa054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kuzuyama T. 2017. Biosynthetic studies on terpenoids produced by Streptomyces. J Antibiot 70:811–818. doi: 10.1038/ja.2017.12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wu C, Zhu H, van Wezel GP, Choi YH. 2016. Metabolomics-guided analysis of isocoumarin production by Streptomyces species MBT76 and biotransformation of flavonoids and phenylpropanoids. Metabolomics 12:90. doi: 10.1007/s11306-016-1025-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Álvarez-Álvarez R, Botas A, Albillos SM, Rumbero A, Martín JF, Liras P. 2015. Molecular genetics of naringenin biosynthesis, a typical plant secondary metabolite produced by Streptomyces clavuligerus. Microb Cell Fact 14:178. doi: 10.1186/s12934-015-0373-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Vaden RM, Oswald NW, Potts MB, MacMillan JB, White MA. 2017. FUSION-guided hypothesis development leads to the identification of N6,N6-dimethyladenosine, a marine-derived AKT pathway inhibitor. Mar Drugs 15:75. doi: 10.3390/md15030075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Chan CTY, Chionh YH, Ho C-H, Lim KS, Babu IR, Ang E, Wenwei L, Alonso S, Dedon PC. 2011. Identification of N6,N6-dimethyladenosine in transfer RNA from Mycobacterium bovis Bacille Calmette-Guérin. Molecules 16:5168–5181. doi: 10.3390/molecules16065168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Islam MR, Jeong YT, Ryu YJ, Song CH, Lee YS. 2009. Isolation, identification and optimal culture conditions of Streptomyces albidoflavus C247 producing antifungal agents against Rhizoctonia solani AG2-2. Mycobiology 37:114–120. doi: 10.4489/MYCO.2009.37.2.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Augustine SK, Bhavsar SP, Kapadnis BP. 2005. A non-polyene antifungal antibiotic from Streptomyces albidoflavus PU 23. J Biosci 30:201–211. doi: 10.1007/BF02703700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Beni A, Soki E, Lajtha K, Fekete I. 2014. An optimized HPLC method for soil fungal biomass determination and its application to a detritus manipulation study. J Microbiol Methods 103:124–130. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2014.05.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ruckenstuhl C, Lang S, Poschenel A, Eidenberger A, Baral PK, Kohút P, Hapala I, Gruber K, Turnowsky F. 2007. Characterization of squalene epoxidase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae by applying terbinafine-sensitive variants. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 51:275–284. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00988-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Berkow EL, Lockhart SR. 2017. Fluconazole resistance in Candida species: a current perspective. Infect Drug Resist 10:237–245. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S118892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Serhan G, Stack CM, Perrone GG, Morton CO. 2014. The polyene antifungals, amphotericin B and nystatin, cause cell death in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by a distinct mechanism to amphibian-derived antimicrobial peptides. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 13:18. doi: 10.1186/1476-0711-13-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Sorgo AG, Heilmann CJ, Dekker HL, Bekker M, Brul S, de Koster CG, de Koning LJ, Klis FM. 2011. Effects of fluconazole on the secretome, the wall proteome, and wall integrity of the clinical fungus Candida albicans. Eukaryot Cell 10:1071–1081. doi: 10.1128/EC.05011-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]