Abstract

Background

Previous studies have demonstrated that pre-exercise suppresses anxiety-like behavior, but the effects of different exercise times on vascular dementia induced anxiety-like behavior have not been well investigated.

Objective

The present study aims to investigate the underlying neurochemical mechanism of different pre-vascular-dementia exercise times on 5-HT and anxiety-like behavior in rats with vascular dementia.

Methods

32 Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats were randomly divided into 4 groups: sham group (S group, n = 8), vascular dementia group (VD group, n = 8), 1-week physical exercise and vascular dementia group (1WVD group, n = 8), and 4 weeks physical exercise and vascular dementia group (4WVD group, n = 8). 1 week and 4 weeks of voluntary wheel running were used as pre-exercise training. The vascular dementia model was established by bilateral common carotid arteries occlusion (BCCAo) for 1 week. But bilateral common carotid arteries were not ligated in the sham group. The level of hippocampal 5-HT was detected with in vivo microdialysis coupled with high-performance liquid chromatography (MD-HPLC). Elevated plus maze (EPM), open field (OF), and light/dark box test were used to test anxiety-like behavior.

Results

Compared with the C group, the hippocampal 5-HT was significantly decreased in the VD group after 1 week of ligated operation. The hippocampal 5-HT levels in 1WVD and 4WVD groups were substantially higher than the level in the VD group. The hippocampal 5-HT level has no significant difference among C, 1WVD, and 4WVD. Behavioral data suggested that the rats in the VD group developed obvious anxiety-like behavior after 1 week of ligation surgery. Still, the rats in 1WVD and 4WVD groups did not show significant anxiety-like behavior.

Conclusion

Both 1 week and 4 weeks of voluntary running wheel exercise can inhibit the anxiety-like behavior in rats with vascular dementia by upregulating 5-HT levels in the hippocampus in the VD model.

Keywords: exercise, vascular dementia, hippocampal, 5-HT, anxiety-like behavior

Introduction

Vascular dementia (VD) is generally believed as the second leading form of dementia after Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and is responsible for around 15% of all dementia patients.1-3 94% VD patients with severe dementia were the most likely to be anxious. 72% of VD patients and 38% of those with AD had 2 or more anxiety symptoms. 4 The anxiety prevalence may be higher in vascular dementia than in Alzheimer’s Disease. The anxiety also associated with poor quality of life and behavioral disturbances. Until recently, little attention has been paid to anxiety symptoms in dementia. 5 Considering that anxiety is associated with an increased risk of VD, treating any of them might reduce the other’s prevalence and incidence. 6

Currently, although all approved anti-AD/VD drugs have been demonstrated as useful in some (but not all) measures, their effect size was relatively small, their heterogeneity was observed in many studies,7,8 and their side effects usually were inevitable. Thus, non-drug treatments have attracted more attention recently. 9 Numerous studies have examined the positive effects of physical exercise intervention on improving anxiety-like behavior in the stroke model.10,11 A previous study found that 4 weeks of physical exercise produced a neuroprotective effect on cognition and behavior in rats with vascular dementia. 12 In addition, our study also found that both 1 week and 4 weeks of exercise preconditioning ameliorates cognitive impairment and anxiety-like behavior via regulation of dopamine in ischemia rats. 13 However, the neurochemical mechanism underlying the effect of exercise pretreatment improving anxiety-like behavior in rats with vascular dementia has not been thoroughly investigated yet.

One distal amygdalar projection target implicated in anxiety-related behaviors is the ventral hippocampus (vHPC).14,15 The vHPC shares robust reciprocal connections with the basolateral nucleus of the amygdala.16,17 Subsequent studies have concluded that the ventral, but not the dorsal, hippocampus is required for the expression of anxiety-related behaviors in the elevated plus-maze (EPM) and open-field test (OFT).18-20 Serotonin (5-HT) is associated with regulating anxiety, reward processing, stress, and mood.21,22 It has been shown that optogenetic stimulation of the median raphe nucleus increased 5-HT neuronal activity and increased the release of 5-HT in the vHPC. 23 Moreover, pharmacological studies have shown that rats undergoing amphetamine withdrawal fail to exhibit stress-induced increases in 5-HT release in the vHPC and show heightened anxiety-like behaviors. 24 Therefore, the hippocampal 5-HT levels are closely related to the production of anxious behaviors.

Although previous studies have demonstrated that 4-week exercise preconditioning significantly improves anxiety behavior in rats with vascular dementia, whether 1-week and 4-week active wheel running can prevent the anxiety-like behavior by modulating hippocampal 5-HT levels in rats with vascular dementia has not been demonstrated. Therefore, the present study investigates different exercise times on hippocampal 5-HT and anxiety-like behavior in rats with vascular dementia.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (3 months of age, weighting 280–320g) were enrolled in this study and randomly divided into the following 4 groups: control group (C group, n = 8), vascular dementia group (VD group, n = 8), 1 week of physical exercise and vascular dementia group (1WEVD group, n = 8), and 4 weeks of physical exercise and vascular dementia group (4WEVD group, n = 8). The rats in 1WEVD and 4WEVD groups were received 1 week and 4 weeks of voluntary wheel running, respectively. Then, all rats except the C group were received bilateral common carotid artery occlusion (BCCAO) to establish the VD model. After 1 week, all rats received a neurological evaluation by “Zea-Longa” 5-point scale to determine VD model was successful or not. Hippocampal 5-HT samples were collected with in vivo microdialysis and were detected by using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Elevated plus maze (EPM), open field (OF), and light/dark box test were used to test anxiety-like behavior. All rats were housed under a 12-h light/dark cycle with sufficient food and water. The institutional animal ethical committee of the Capital University of Physical Education and Sports, Beijing, China approved all procedures and protocols. An experiments timeline in each group is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

A timeline in each group. “+" represents rats who received exercise intervention or/and VD operation and subsequent test; "-" represents no.

Physical Exercise Intervention

The rats in 1WEVD and 4WEVD groups were housed individually with 1 running wheel per animal to assure running distance. The rats had free access to the running wheel for 1 week or 4 weeks, respectively. Daily wheel revolutions were recorded digitally and average running distance was obtained per week.

Establishment of Vascular Dementia Model

Bilateral common carotid artery occlusion was carried out in the rats to establish a vascular dementia model.25,26 The animals were anesthetized with chloral hydrate (8% emulsified isoflurane, i. p.). A midline incision was made to expose the bilateral common carotid arteries. The exposed carotid arteries were tightly ligated with 4-0 silk sutures. Throughout the surgery, the rats' body temperature was maintained at 37°C with a heating pad. 27 After 1 week, neurological evaluation was performed and scored on the “Zea-Longa” 5-point scale. 28 A score between 1 and 4 indicates successful modeling of VD. Rats not showing neurological defects were excluded from the study. In addition, rats that scored 1 to 3 points were selected and used for this experiment. (Table 1).

Table 1.

“Zea-Longa” 5-point scale.

| Point | Symptom |

|---|---|

| 0 | No neurological deficit |

| 1 | Failure to extend left forepaw fully |

| 2 | Circling to the left |

| 3 | Falling to the left |

| 4 | No spontaneous walking with a depressed level of consciousness |

| 5 | Death |

Behavioral Test

Twenty-four hours after establishing VD mode, animals were subjected to behavioral tests. The behavioral tests were conducted sequentially in the EPM, OF, and light/dark box, with an interval of 24 hours between each test. The EPM analyzed anxiety-like behavior by determining animals' emotional responses to external stressful stimuli. 29 The EPM was made of black polypropylene and had 2 opposing open arms (25 × 8 cm), 2 opposing closed arms (25 × 8 × 20 cm), and a central platform (8 × 8 × 8 cm) shaped like a cross. The maze was 50 cm above the ground. Individual rats were placed in the center, their heads pointing toward one of the closed arms. All 4 paws entering an arm were defined as an open or closed arms entry. Animals were left in the EPM for 5 min to assess arm entry, and the number of entries open arms and the percentage of open arms time were analyzed, and the results were expressed in the form of mean ± standard deviation.

The open-field test (OF) was used to determine animals' spontaneous locomotor activity. 30 The OF test was conducted 24 hours after EPM. The OF was performed in a 50 × 50 cm open field surrounded by 50 cm high walled Plexiglas chambers in standard room lighting conditions. The individual rat was placed in the center and given 5 minutes to explore the arena. The number and timing of accesses to the central region were analyzed in the OF and the results were expressed in the form of mean ± standard deviation.

The light/dark box was also used to test anxiety-like behavior in rats 24 hours after the OF. 31 In brief, it consists of 2 dark Plexiglas chambers of the same size (23 cm x 15 cm x 15 cm). The lightbox has a transparent lid illuminated by a 100-W table lamp. Animals could cross from one box to the other through a small hole in the wall. Each rat was placed in the illuminated box and observed for 5 minutes after entering the dark box. The rat with 4 paws in the next box was considered to have changed compartments. The behavioral variables analyzed were time spent in the illuminated box (seconds) and the number of transitions between light and dark compartments.

The behavioral tests were conducted in an isolated behavioral testing room within the animal facility to avoid external distractions. Investigators observed animal behavior via a video monitor in another room. Shanghai Mobile Datum Information Technology Co., Ltd. provided the apparatus and analysis software used in the behavioral tests. Rats were housed in the testing room for at least 1 hour before the experiments to adapt to the experimental environment. The animals were uninformed about the test situation and were only used once. 32 All behavior tests equipment was cleaned with a 75% ethyl alcohol solution after each testing.

Neurotransmitter Measurement

The level of hippocampal 5-HT was measured by microdialysis coupled with high-performance liquid chromatography (MD-HPLC). First, the animals were anesthetized with chloral hydrate (8% emulsified isoflurane, i. p.) and placed in a stereotaxic frame with the incisor-bar set at 3.3 mm below the interaural line for the flat skull position. According to standard stereotaxic procedures, a microdialysis guide cannula was implanted into the hippocampus (AP: −5.6, L: ± 4.6, V: + 4.1, relative to bregma). Next, the perfusion syringes were loaded with fresh aCSF, and probes were allowed to equilibrate for an additional 1 h at a flow rate of 1 μl/min. Then, extracellular fluid was collected in an EP tube (with 15 μL of 10 mmol HCL). Rats were sacrificed after the microdialysis experiment. Hippocampal 5-HT in the microdialysate samples was analyzed for 5-HT content in an HPLC system equipped with an isocratic pump (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, U.S.A., Waters 515, flow 1 mL/min), RP-18 column (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, U.S.A., Xterra, 5 μM particle size, 2.1 × 100 mm, Waters), and an amperometric detector (BAS Inc, West Lafayette, IN, U.S.A., LC-4B, oxidation potential .5 V).

Statistical Analysis

All data in this study are presented as the mean ± SD. Differences in the behavioral tests, neurological defect scores, and 5-HT levels in different groups were analyzed using one-way ANOVA, followed by the Bonferroni test for intergroup comparisons. The average distance was analyzed by using an independent sample t-test. All statistical tests were performed with SPSS 20.0 and GraphPad Prism 8. All differences were considered significant at P < .05.

Results

VD Model’s Neurological Evaluation

Figure 2 shows the neurological defect score in each group. Our results showed that the neurological defect score in VD, 1WVD, and 4WVD groups was significantly higher than in the C group [F(3,28)=6.75, P = .001]. But there was no significant difference between VD, 1WVD, and 4WVD groups (P > .05). It indicated that the vascular dementia model was successfully established in our experiment.

Figure 2.

The neurological defect score in each group. ** P < .01 vs C group.

The Running Distance in 1WVD and 4WVD Groups

As shown in Figure 3, the average running distance in 1 WVD and 4WVD groups was 878.73 ± 203.65 m and 948.61 ± 162.61 m. There is no significant difference between 1WVD and 4WVD groups (t(14)= 55.25, P = .347, d = −.49). Our data indicated that volunteer running exercise interventions were successful in our experiment.

Figure 3.

Average distance in WVD and 4WVD groups.

Elevated Plus Maze

Figure 4A shows the entries into open arms in each group after VD. The percent time in the 4 groups had a significant difference [F(3,28) = 6.566, P = .002], and Bonferroni multiple comparisons post hoc tests showed that the entries into open arms of C, 1WVD, and 4WVD group were significantly greater when compared with the VD group (P < .01). There was no significant difference among C, 1WVD, and 4WVD groups (P > .05). Figure 4B shows the percent time of open arms in each group after VD. The percent time in the 4 groups had a significant difference [F(3,28)=14.822, P = .00005], and Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons post hoc test showed that the percent time of C, 1WVD, and 4WVD group was significantly longer when compared with the VD group (P < .01). There was no significant difference among C, 1WVD, and 4WVD groups (P > .05).

Figure 4.

(A) The entries into open arms in each group after VD. ** P < .05 compared with C group, ** P < .01 compared with VD group. (B): The percent time of open arms in each group after VD. ** P < .001 compared with C, 1WVD, and 4WVD groups.

Open Field Test

Figure 5A shows the entries into the center area in the open field test. The entries into the center area in the 4 groups had significant differences [F(3,28)=7.897, P = .001]. Bonferroni multiple comparisons post hoc test showed that the entries into the center area of C, 1WVD, and 4WVD group were significantly greater when compared with VD group (P < .01). There was no significant difference among C, 1WVD, and 4WVD groups (P > .05). Figure 5B shows the time in each group’s center area after VD. The time in the center area had a significant difference [F(3,28)=4.016, P=.017]. Bonferroni multiple comparisons post hoc test showed that the entrance numbers of C and 4WVD group were significantly greater when compared with VD group (P < .01). There was no significant difference among C, 1WVD, and 4WVD groups (P > .05).

Figure 5.

(A): The entries into the center area of 4 groups in the open field test. ** P < .01 compared with C, 1WVD, and 1WVD groups. (B): The time in the center area in the open field test. ** P < .05 compared with the VD group.

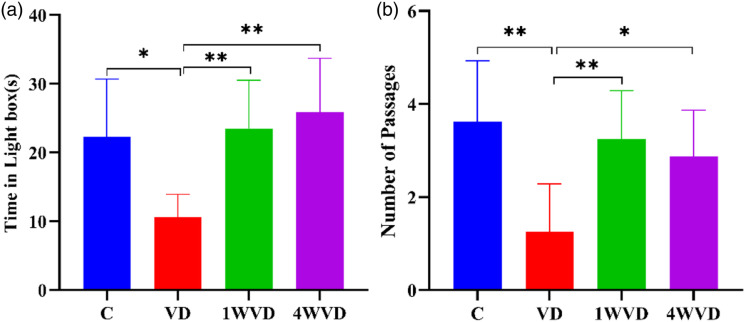

The Light/Dark Box Test

Figure 6A shows the percent time in the lightbox of each group after VD. The percent time in the 4 groups had a significant difference [F(3,28)=7.668, P = .001]. Bonferroni multiple comparisons post hoc test showed that the percent time of C, 1WVD, and 4WVD groups was significantly longer when compared with the VD group (P < .05). There was no significant difference among C, 1WVD, and 4WVD groups (P > .05). Figure 6B shows the number of passages in each group after VD. The number of passages in the 4 groups had a significant difference [F(3,28)=7.259, P = .001], and Bonferroni multiple comparisons post hoc test showed that the entrance numbers of C, 1WVD, and 4WVD group were significantly greater when compared with the VD group (P < .01). There was no significant difference among C, 1WVD, and 4WVD groups (P > .05).

Figure 6.

(A): The percent of time in a lightbox in each group after VD. * P < .05 compared with VD group, ** P < .01 compared with VD group. (B): The number of passages in each group. ** P < .01 compared with the VD group. ** P < .01 compared with the 4WVD group.

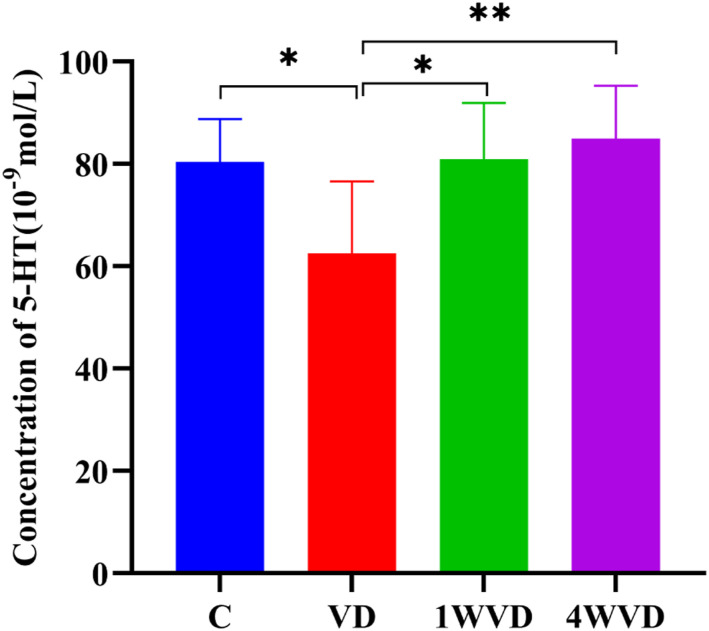

HT Level in Each Group

Figure 7 shows the 5-HT level in each group. The 5-HT level in the 4 groups had a significant difference [F(3,28)=6.381, P = .002]. Bonferroni multiple comparisons post hoc test showed that the 5-HT level of C, 1WVD, and 4WVD group was significantly higher when compared with the VD group (P < .05). There was no significant difference among C, 1WVD, and 4WVD groups (P > .05).

Figure 7.

The hippocampal 5-HT level in each group. ** P < .01, * P < .05 compared with VD group.

Discussion

Vascular dementia (VD) is considered as one of the most common causes of dementia after Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Anxiety states often accompany the cognitive impairment in clinical and in vivo studies.33-35

Previous studies often used elevated plus maze, open-field test, and light/dark box to evaluate anxiety-like behavior in rats. 36 Thus, we also chose the above 3 tests to assess anxiety-like behavior in this experiment. Our results found that the percent time and entries into open arms in elevated plus maze test, the time and entries into the center area in the open field test, and the time and number of passages in the light/dark box test were significantly shorter in rats with vascular dementia than that in C group. Therefore, we believe that vascular dementia rats develop anxiety-like behavior.

Consistently with previous studies, 1 study found that rats induced anxiety-like behavior and decreased exploratory activity in open field tests compared to age-matched controls, 37 our preliminary research reported that the time spent of open arms in the molar loss group was significantly shorter 38 ; the present study used all 3 tests to determine more accurately the presence of anxiety-like behavior in rats with vascular dementia. In addition, our previous experiments also used the open field to discriminate anxiety-like behavior in rats, which produced inconsistent results with our present experimental results. Our preliminary study found that the time in the center of VD rats was significantly increased. 39 The reasons for the above results may be: (1) a new software evaluation system was used in this experiment; (2) unlike the results of the previous study, the neurobehavioral scores after modeling in this experiment were lower; (3) the results of some studies confirmed that the use of chloral hydrate to anesthetize animals might cause changes in the emotions and neurotransmitters of rats, so different anesthetic drugs are used. 40

Furthermore, our results also show the hippocampal 5-HT in the VD group was significantly decreased, and 1 or 4 weeks of voluntary running wheel exercise significantly inhibit the decline of hippocampal 5-HT. The earlier study observed the significant falls in 5-HT were found on the operated side in the group with right common carotid artery occlusion and there was also a trend for 5HT to fall on the unoperated side 41 ; the above result is consistent with our study. Besides, previous studies have found that 16 days of treadmill exercise upregulated the levels of 5-HT, 5-HT1AR, and BDNF in rats with ischemia. 42 And another research found that acute exercise stimulated 5-HT release in the hippocampus of food-deprived rats. 43 Our experiment results, consistent with the previous reports, indicate that exercise can increase 5-HT release in the rat brain or attenuate 5-HT decrease induced by VD.

Existing evidence suggests that decreases in hippocampal 5-HT levels were believed to induce anxiety-like behaviors of rats.44,45 Our and previous studies have shown that hippocampal 5-HT exhibited significantly decrease after VD, which is associated with multiple mechanisms such as inflammation and oxidative stress responses.46,47 However, it is worth mentioning the positive effect of exercise treatment for VD by multiple mechanisms, such as enhancing the expression of nervous factors and improving synaptic plasticity. 10 As a common form of exercise, volunteer running exercise is an active and spontaneous exercise that can be carried out according to the living habits and characteristics of rats, and it has a better positive effect in terms of emotional function.48,49 Thus, we also choose volunteer running exercise as an intervention to treat anxiety behavior in the vascular dementia model. Several papers have emphasized the beneficial effects of exercise on releasing anxiety status, including (but not limited to) increased neurogenesis, enhanced synaptic plasticity, and relieved neuroinflammation.50-52 In addition, new evidence has shown that aerobic exercise upregulates the BDNF-serotonin systems in rats. 53 Therefore, we suggest that the above factors are responsible for exercise suppressing anxiety-like behavior and 5-HT changes after VD in our experiment.

In summary, this study shows that different physical exercises intervention, such as 1 week and 4 weeks of voluntary running, can inhibit the development of anxiety-like behaviors by suppressing the reduction of 5-HT in the VD model.

But this study still has several drawbacks. On the one hand, it is unclear whether exercise increases hippocampal 5-HT level by the neural-protective effect of neurons, thus improving anxiety-like behaviors in the vascular dementia model. The related immunohistochemistry evidence will be investigated in our further research studies. On the other hand, it is worth mentioning that there was no difference between 1 week and 4 weeks of voluntary running exercise that improved anxiety-like behaviors after VD in hippocampal 5-HT level and neural behavior aspect. Whether there is a difference in other neurochemical aspects needs to be explored further.

Conclusion

1 week and 4 weeks of voluntary running exercise can improve anxiety-like behaviors in VD rats. It is presumed that the mechanism may be related to the neuroprotective effect of exercise, which can maintain 5-HT levels in hippocampal brain regions in the vascular dementia model.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-1-aja-10.1177_15333175221082743 for Different Exercise Time on 5-HT and Anxiety-like Behavior in the Rat With Vascular Dementia in Yongzhao Fan, Linlin Zhang, Xiaoyang Kong, Kun Liu and Hao Wu in American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease & Other Dementias®

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-2-aja-10.1177_15333175221082743 for Different Exercise Time on 5-HT and Anxiety-like Behavior in the Rat With Vascular Dementia in Yongzhao Fan, Linlin Zhang, Xiaoyang Kong, Kun Liu and Hao Wu in American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease & Other Dementias®

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support by the NSF of China (Grant Nos. 21475089), Innovation Platform of Beijing Municipality (PXM2015014206000053, PXM2015014206000051), S, National Key Research and Development of China (Nos. 2018YFF0300603).

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the NSF of China (Grant Nos. 21475089), Innovation Platform of Beijing Municipality (PXM2015014206000053, PXM2015014206000051), S, National Key Research and Development of China (Nos. 2018YFF0300603).

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

ORCID iD

Yongzhao Fan, PhD https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9073-8361

References

- 1.Borges-Machado F, Ribeiro Ó, Sampaio A, Marques-Aleixo I, Meireles J, Carvalho J. Feasibility and Impact of a Multicomponent Exercise Intervention in Patients With Alzheimer's Disease: A Pilot Study. Am J Alzheimer's Dis Other Dementias. 2019;34(2):95-103. doi: 10.1177/1533317518813555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jongsiriyanyong S, Limpawattana P. Mild Cognitive Impairment in Clinical Practice: A Review Article. Am J Alzheimer's Dis Other Dementias. 2018;33(8):500-507. doi: 10.1177/1533317518791401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kalaria RN, Maestre GE, Arizaga R, et al. Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia in developing countries: Prevalence, management, and risk factors. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7(9):812-826. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70169-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ballard C, Neill D, O’Brien J, McKeith IG, Ince P, Perry R. Anxiety, depression and psychosis in vascular dementia: Prevalence and associations. J Affect Disord. 2000;59(2):97-106. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00057-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seignourel PJ, Kunik ME, Snow L, Wilson N, Stanley M. Anxiety in dementia: a critical review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008;28(7):1071-1082. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Santabárbara J, Lipnicki DM, Olaya B, et al. Association between anxiety and vascular Dementia Risk: New evidence and an updated meta-analysis. J Clin Med. 2020;9(5):1368. doi: 10.3390/jcm9051368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kavirajan H, Schneider LS. Efficacy and adverse effects of cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine in vascular dementia: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(9):782-792. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70195-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Korczyn AD, Vakhapova V, Grinberg LT. Vascular dementia. J Neurol Sci. 2012;322(1-2):2-10. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2012.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dimitriou T-D, Verykouki E, Papatriantafyllou J, Konsta A, Kazis D, Tsolaki M. Non-Pharmacological interventions for the anxiety in patients with dementia. A cross-over randomised controlled trial. Behav Brain Res. 2020;390:112617. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2020.112617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dong J, Zhao J, Lin Y, et al. Exercise improves recognition memory and synaptic plasticity in the prefrontal cortex for rats modelling vascular dementia. Neurol Res. 2018;40(1):68-77. doi: 10.1080/01616412.2017.1398389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gallaway P, Miyake H, Buchowski M, et al. Physical activity: A viable way to reduce the risks of mild cognitive impairment, Alzheimer's disease, and vascular dementia in older adults. Brain Sci. 2017;7(2):22. doi: 10.3390/brainsci7020022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi D-H, Lee K-H, Lee J. Effect of exercise-induced neurogenesis on cognitive function deficit in a rat model of vascular dementia. Mol Med Rep. 2016;13(4):2981-2990. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.4891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fan Y, Wang Y, Ji W, Liu K, Wu H. Exercise preconditioning ameliorates cognitive impairment and anxiety-like behavior via regulation of dopamine in ischemia rats. Physiol Behav. 2021;233:113353. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2021.113353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.File SE, Gonzalez LE. Anxiolytic effects in the plus-maze of 5-HT1A-receptor ligands in dorsal raphé and ventral hippocampus. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1996;54(1):123-128. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(95)02108-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McHugh SB, Deacon RMJ, Rawlins JNP, Bannerman DM. Amygdala and ventral hippocampus contribute differentially to mechanisms of fear and anxiety. Behav Neurosci. 2004;118(1):63-78. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.118.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O'Donnell P, Grace A. Synaptic interactions among excitatory afferents to nucleus accumbens neurons: hippocampal gating of prefrontal cortical input. J Neurosci. 1995;15(5 Pt 1):3622-3639. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-05-03622.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pikkarainen M, Ronkko S, Savander V, Insausti R, Pitkanen A. Projections from the lateral, basal, and accessory basal nuclei of the amygdala to the hippocampal formation in rat. J Comp Neurol. 1999;403(2):229-260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bannerman DM, Deacon RMJ, Offen S, Friswell J, Grubb M, Rawlins JNP. Double dissociation of function within the hippocampus: spatial memory and hyponeophagia. Behav Neurosci. 2002;116(5):884-901. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.116.5.884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kheirbek MA, Drew LJ, Burghardt NS, et al. Differential control of learning and anxiety along the dorsoventral axis of the dentate gyrus. Neuron. 2013;77(5):955-968. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.12.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kjelstrup KG, Tuvnes FA, Steffenach H-A, Murison R, Moser EI, Moser M-B. Reduced fear expression after lesions of the ventral hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci Unit States Am. 2002;99(16):10825-10830. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152112399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang D, Tian H-l., Cui X, et al. Effects of Jian-Pi-Zhi-Dong Decoction on the Expression of 5-HT and Its Receptor in a Rat Model of Tourette Syndrome and Comorbid Anxiety. Med Sci Mon Int Med J Exp Clin Res. 2020;26:e924658. doi: 10.12659/MSM.924658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Millan MJ. The neurobiology and control of anxious states. Prog Neurobiol (Oxf). 2003;70(2):83-244. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(03)00087-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abela AR, Browne CJ, Sargin D, et al. Median raphe serotonin neurons promote anxiety-like behavior via inputs to the dorsal hippocampus. Neuropharmacology. 2020;168:107985. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2020.107985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tu W, Cook A, Scholl JL, et al. Serotonin in the ventral hippocampus modulates anxiety-like behavior during amphetamine withdrawal. Neuroscience. 2014;281:35-43. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu K, Yu P, Lin Y, Wang Y, Ohsaka T, Mao L. Online electrochemical monitoring of dynamic change of hippocampal ascorbate: toward a platform for in vivo evaluation of antioxidant neuroprotective efficiency against cerebral ischemia injury. Anal Chem. 2013;85(20):9947-9954. doi: 10.1021/ac402620c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu K, Lin Y, Yu P, Mao L. Dynamic regional changes of extracellular ascorbic acid during global cerebral ischemia: Studied with in vivo microdialysis coupled with on-line electrochemical detection. Brain Res. 2009;1253:161-168. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.11.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kwon KJ, Kim MK, Lee EJ, et al. Effects of donepezil, an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, on neurogenesis in a rat model of vascular dementia. J Neurol Sci. 2014;347(1-2):66-77. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2014.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang G, Liu A, Zhou Y, San X, Jin T, Jin Y. Panax ginseng ginsenoside-Rg2 protects memory impairment via anti-apoptosis in a rat model with vascular dementia. J Ethnopharmacol. 2008;115(3):441-448. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Felix-Ortiz AC, Beyeler A, Seo C, Leppla CA, Wildes CP, Tye KM. BLA to vHPC inputs modulate anxiety-related behaviors. Neuron. 2013;79(4):658-664. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peng Y, Feng S-F, Wang Q, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen preconditioning ameliorates anxiety-like behavior and cognitive impairments via upregulation of thioredoxin reductases in stressed rats. Prog Neuro Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatr. 2010;34(6):1018-1025. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller SM, Piasecki CC, Lonstein JS. Use of the light-dark box to compare the anxiety-related behavior of virgin and postpartum female rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2011;100(1):130-137. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang L-L, Wang J-J, Liu Y, et al. GPR26-deficient mice display increased anxiety- and depression-like behaviors accompanied by reduced phosphorylated cyclic AMP responsive element-binding protein level in central amygdala. Neuroscience. 2011;196:203-214. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.08.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Becker E, Orellana Rios CL, Lahmann C, Rücker G, Bauer J, Boeker M. Anxiety as a risk factor of Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia. Br J Psychiatr. 2018;213(5):654-660. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2018.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Santabárbara J, Lipnicki DM, Olaya B, et al. Association between Anxiety and Vascular Dementia Risk: New Evidence and an Updated Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med. 2020;9(5):1368. doi: 10.3390/jcm9051368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu J, Sun J, Wang F, et al. Neuroprotective Effects ofClostridium butyricumagainst Vascular Dementia in Mice via Metabolic Butyrate. BioMed Res Int. 2015;2015:1-12. doi: 10.1155/2015/412946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Belovicova K, Bogi E, Csatlosova K, Dubovicky M. Animal tests for anxiety-like and depression-like behavior in rats. Interdiscipl Toxicol. 2017;10(1):40-43. doi: 10.1515/intox-2017-0006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Venkat P, Chopp M, Zacharek A, et al. White matter damage and glymphatic dysfunction in a model of vascular dementia in rats with no prior vascular pathologies. Neurobiol Aging. 2017;50:96-106. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2016.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang L, Feng Y, Ji W, Liu J, Liu K. Effect of voluntary wheel running on striatal dopamine level and neurocognitive behaviors after molar loss in rats. Behav Neurol. 2017;2017:1-6. doi: 10.1155/2017/6137071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang L, Fan Y, Kong X, Hao W. Neuroprotective effect of different physical exercises on cognition and behavior function by dopamine and 5-HT level in rats of vascular dementia. Behav Brain Res. 2020;388:112648. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2020.112648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Herrmann K, Flecknell P. Retrospective review of anesthetic and analgesic regimens used in animal research proposals. ALTEX. 2019;36(1):65-80. doi: 10.14573/altex.1804011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harrison MJ, Marsden CD, Jenner P. Effect of experimental ischemia on neurotransmitter amines in the gerbil brain. Stroke. 1979;10(2):165-168. doi: 10.1161/01.str.10.2.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lan X, Zhang M, Yang W, et al. Effect of treadmill exercise on 5-HT, 5-HT1A receptor and brain derived neurophic factor in rats after permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion. Neurol Sci. 2014;35(5):761-766. doi: 10.1007/s10072-013-1599-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meeusen R, Thorré K, Chaouloff F, et al. Effects of tryptophan and/or acute running on extracellular 5-HT and 5-HIAA levels in the hippocampus of food-deprived rats. Brain Research. 1996;740(1-2):245-252. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)00872-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guimarães FS, Del Bel EA, Padovan CM, Netto SM, de Almeida RT. Hippocampal 5-HT receptors and consolidation of stressful memories. Behav Brain Res. 1993;58(1-2):133-139. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(93)90098-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Graeff FG, Guimarães FS, De Andrade TGCS, Deakin JFW. Role of 5-HT in stress, anxiety, and depression. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1996;54(1):129-141. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(95)02135-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Iadecola C. The pathobiology of vascular dementia. Neuron. 2013;80(4):844-866. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Román GC, Erkinjuntti T, Wallin A, Pantoni L, Chui HC. Subcortical ischaemic vascular dementia. Lancet Neurol. 2002;1(7):426-436. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(02)00190-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ke Z, Yip SP, Li L, Zheng X-X, Tong K-Y. The effects of voluntary, involuntary, and forced exercises on brain-derived neurotrophic factor and motor function recovery: a rat brain ischemia model. PLoS One. 2011;6(2):e16643. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Robison LS, Popescu DL, Anderson ME, et al. The effects of volume versus intensity of long-term voluntary exercise on physiology and behavior in C57/Bl6 mice. Physiol Behav. 2018;194:218-232. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2018.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kondo M, Nakamura Y, Ishida Y, Shimada S. The 5-HT3 receptor is essential for exercise-induced hippocampal neurogenesis and antidepressant effects. Mol Psychiatr. 2015;20(11):1428-1437. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lourenco MV, Frozza RL, de Freitas GB, et al. Exercise-linked FNDC5/irisin rescues synaptic plasticity and memory defects in Alzheimer's models. Nat Med. 2019;25(1):165-175. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0275-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Piao C-S, Stoica BA, Wu J, et al. Late exercise reduces neuroinflammation and cognitive dysfunction after traumatic brain injury. Neurobiol Dis. 2013;54:252-263. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pietrelli A, Matković L, Vacotto M, Lopez-Costa JJ, Basso N, Brusco A. Aerobic exercise upregulates the BDNF-Serotonin systems and improves the cognitive function in rats. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2018;155:528-542. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2018.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-1-aja-10.1177_15333175221082743 for Different Exercise Time on 5-HT and Anxiety-like Behavior in the Rat With Vascular Dementia in Yongzhao Fan, Linlin Zhang, Xiaoyang Kong, Kun Liu and Hao Wu in American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease & Other Dementias®

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-2-aja-10.1177_15333175221082743 for Different Exercise Time on 5-HT and Anxiety-like Behavior in the Rat With Vascular Dementia in Yongzhao Fan, Linlin Zhang, Xiaoyang Kong, Kun Liu and Hao Wu in American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease & Other Dementias®