Abstract

Objective: This study examines trends in the mortality of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias in China from 1990 to 2019. Methods: The data were drawn from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (GBD 2019), and an age–period–cohort model was used for analysis. Results: The net drift was .152% (95% confidence interval [CI]: .069%, .235%) per year for men (P < .05) and .024% (95% CI: −.078%, .126%) per year for women. The local drift values were below 0 in both genders for people aged 45–54 years (P < .05), and above 0 for males aged 60–94 years and females aged 60–79 years (P < .05). In the same birth cohort, the risk of mortality of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias exponentially increases with age for both genders. Conclusion: More rapid and effective efforts are needed to mitigate the substantial impact of Alzheimer's and other dementias on the health of China’s elderly.

Keywords: age–period–cohort analysis, Alzheimer’s disease and dementias, time trend, China

Introduction

“Dementia” is a collective term for progressive brain syndromes that affect memory, thinking, behavior, and emotions and can reduce a person's ability to perform everyday activities. 1 It is estimated that 50 million people worldwide lived with dementia in 2018, the most recent year for which figures are available, and driven by an aging population, the number is expected to more than triple to 152 million by 2050. 2 Dementia carries enormous economic costs because people with dementia are generally in a state of being disabled and dependent. 3 Alzheimer's disease and other dementias, the world's fifth-leading cause of death, caused an estimated $1 trillion in economic losses worldwide in 2018. 4

In China, Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias have become a central public health issue. It is estimated that in 2015 there were more than 9.5 million people with dementia in China, accounting for 20% of dementia cases in the world. And the number of dementia patients in China is expected to rise to more than 16 million by 2030. 3

Multiple studies have found that the dementia mortality rate in China has changed over time. The crude mortality rate for Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias rose, while the age-standardized mortality decreased, from 2009 to 2015. 3 For individuals aged 65 years and older, the age-standardized dementia mortality rate decreased from 2006 to 2009, before rising through 2012. 5 However, there has been no comprehensive analysis of the possible reasons underlying the temporal trends. Furthermore, long-term research into the trend of dementia mortality is still lacking in China.

To address these problems, this study examines the long-term trends in the mortality of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias in China from 1990 to 2019 using data from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (GBD 2019) and employing an age–period–cohort (APC) framework. The findings from this study can help inform efforts for the active prevention and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias in China.

Methods

Data Source

The data used in this study were extracted from the GBD 2019, which is a comprehensive dataset that captures incidence, prevalence, and mortality by age and gender for more than 300 diseases and injuries across 204 countries and territories. 6 Data used to estimate deaths due to Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias in China primarily included surveillance data from the China Disease Surveillance Points (DSPs) system (covers 24.3% of the total population of the country since 2013) and vital registration (VR) data (accounting for roughly 8% of the national population) collected by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); these two systems are well designed and would provide a nationally representative picture of diseases in China.7,8 All of the deaths and causes of death (CoD) information were collected and reported via the Mortality Registration and Reporting System. Trained doctors filled in the “Death Certificate,” where the diseases that led to death and the earlier cause will be recorded, but only the root cause of death, defined as the earliest disease that causes other diseases to be causal, will be included in the statistical analysis of the CoD. 9

Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias were defined in this study according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders III, IV or 5, or ninth and 10th revisions of International Classification of Diseases (ICD) (F00-F02.0, F02.8-F03.9, G30-G31.1, G31.8-G31.9 for ICD-10, and 290-290.9, 294.1-294.9, 331-331.2 for ICD-9). 6 The definition of “death from ad and other dementias” in this study means that ad and other dementias are the earliest disease or injury in a series of pathological events that directly lead to death.

Statistical Analysis

To distinguish the effects of age, period, and cohort on the mortality changes of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias, an APC model was used in the study. The APC model is a method that considers the potential for data aggregated over age, period, and cohort because they are linearly dependent, as in Cohort = Period - Age. The core form of the APC model is as follows 10

where the time effects, , , and , are functions of the respective time indices in this non-parametric model. 10 In the APC model, age effects indicate different risks across different life stages, period effects reflect exposure risk of the entire population during a specific period, and cohort effects indicate risks of different birth cohorts. 11

For the APC model, the following parameters were estimated. Net drift refers to the overall annual percentage change over time. 12 Local drift refers to the annual percentage change in a specific age group. 12 The longitudinal age curves of mortality indicate the fitted longitudinal age-specific rates in the reference cohort after adjusting for period deviations. 11 Period (or cohort) relative risk (RR) represents the RR value relative to the reference period (or cohort), after adjusting for the effects of age and non-linear cohort (or period).

For the APC analysis, the mortality data were divided into consecutive 5-year periods from 1990–1994 (median 1992) to 2015–2019 (median 2017) and successive 5-year age groups from 40–44 to 90–94 years old. The GBD 2019 did not capture Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias in individuals under 40 years old, and recorded individuals over the age of 95 years as one group, those age cohorts were not considered in this study. We obtained the estimable parameters through the APC Web Tool. 13 The central age group, period, and birth cohort were defined as the reference. All statistical tests were 2-sided, in which P-values less than .05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Trends of the Mortality for Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias by Gender From 1990 to 2019

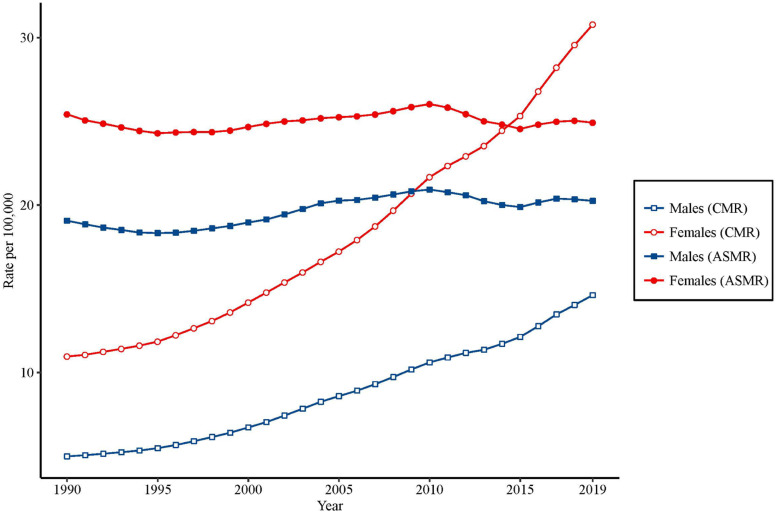

Figure 1 shows trends of the crude and the age-standardized mortality rates for Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias by gender from 1990 to 2019. Although the crude mortality rates (CMRs) for Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias rose from 5.0 to 14.6 per 100 000 individuals for males and 11.0 to 30.8 per 100 000 individuals for females from 1990 to 2019, the age-standardized mortality rates (ASMRs) showed generally stable trends in both genders, from 19.1 to 20.3 per 100 000 for males and 25.4 to 24.9 per 100 000 for females from 1990 to 2019.

Figure 1.

Trends of the Age-Standardized Mortality Rates and Crude Mortality Rates per 100 000 People for Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias by Gender in China From 1990 to 2019.

Local Drift with Net Drift Values for the Mortality of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias by Gender in China

Figure 2 shows the overall annual percentage change (net drift) in mortality of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, as well as the annual percentage change for specific age groups (local drifts) by gender from 1990 to 2019. The net drift was .152% (95% confidence interval [CI]: .069%, .235%) per year for males (significantly with P < .05) and .024% (95% CI: −.078%, .126%) per year for females. The local drift values were below 0 in both genders for people aged 45–54 years, and above 0 for males aged 60–94 years and females aged 60–79 years (significantly with P < .05).

Figure 2.

Age Group-Specific Annual Percent Change (local drift) with the Overall Annual Percent Change (net drift) in the Mortality Rate and the Corresponding 95% Confidence Intervals for Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias in Both Genders in China.

The Longitudinal Age Curves of the Mortality for Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias by Gender in China

Figure 3 shows the longitudinal age curves of the mortality for Alzheimer's disease and other dementias by gender. For people in the same cohort, the risk of death caused by Alzheimer's disease and other dementias showed an accelerated increase with age in both males and females. These curves can be expressed as rate = .027×e0.132×mean_age for men (R-squared = .982) and rate = .027×e0.135×mean_age for women (R-squared = .976). This indicated that the RR of mortality for Alzheimer's disease and other dementias in each life stage from age 40–44 to 90–94 years was 952.0 for men and 970.5 for women compared with the previous life stage.

Figure 3.

Longitudinal Age Curves of the Mortality and the Corresponding 95% CI (some of CIs were too narrow to show in the figure) for Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias by Gender in China. Period RRs and Cohort RRs of the Mortality for Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias by Gender in China. CI: Confidence Intervals.

Figures 4 and 5 show the estimated period and cohort RRs by gender. The period RRs were found to have similar patterns in both genders, where there was a period of increase between 1995 and 2010, with a peak between 2005 and 2010, after which there was a decline. Cohort RRs in general followed upward patterns for both genders for those born before 1950, but the cohort RRs did not significantly change for men born after 1955 and women born after 1960.

Figure 4.

Period Relative Risks of the Mortality and 95% Confidence Intervals for Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias by Gender in China.

Figure 5.

Cohort Relative Risks of the Mortality and 95% Confidence Intervals for Alzheimer’s Disease and other Dementias by Gender in China.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first published study to investigate the long-term mortality trends of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias in China and to examine age-, period- and cohort-specific effects using the APC framework by gender. Our results indicate that while ASMRs of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias show a stable trend among women and scant growth among men, CMR for both men and women rose substantially from 1990 to 2019. The mortality of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias decreased for people in both genders aged 45–54 years, and increased among males aged 60–94 years and females aged 60–79 years between 1990 and 2019.

This study found differences between the ASMR and CMR of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias among both women and men, which may attributable to the aging of the Chinese population. Due to the increase in life expectancy and the decline in fertility caused by China's one-child policy, the Chinese population has been rapidly aging. 14 Meanwhile, as shown in Figure 3, the mortality of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias increases significantly in older age.

As a result, the growth of the elderly population in China has led to a rapid increase in CMR. According to a national survey conducted by the National Bureau of Statistics of China, the total number of people aged 65 years and over in China was 167 million, accounting for 11.9% of the total population in 2018. 15 It is estimated that by 2050 the number of people aged over 65 years in China will reach 400 million, accounting for 26.9% of the total population, 14 a development that can be expect to contribute to the rise of CMR.

Aging is the greatest demographic risk factor for Alzheimer's disease and other dementias. 16 Besides genetics, a number of age-related acquired factors increase the risk of developing Alzheimer's disease and other dementias, include cerebrovascular diseases, hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and dyslipidemia. 17 Due to physiological changes, accumulation of exposure to risk factors and unhealthy lifestyle habits, these acquired factors are more likely to occur in the elderly, thereby increasing the risk of mortality for Alzheimer's disease and other dementias. At the same time, the elderly are more prone to stress, 18 depression, 19 and inadequate sleep, which all contribute to developing Alzheimer's disease and other dementias.

The results of this study are consistent with those of previous studies,20,21 which found that women are more vulnerable than men to developing Alzheimer's disease and other dementias, possibly as a result of gender differences in brain structure, brain development, function, and biochemistry. 20 Our study also found that the mortality for Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias increased in the older age groups (60–94 years for men and 60–79 years for women) in China during the past 30 years. Considering the ongoing aging of China’s elderly population, Alzheimer's disease and other dementias may substantially burden China’s health and social care systems.

The period effect reflects the immediate impact of social factors on the mortality of disease. 22 Our results show that the period effect has a tendency to rise at the beginning and then decline in later years. This may be related to a series of reforms introduced by the Chinese government since 2003 to make health care more accessible.23,24 These reforms have made treatment for Alzheimer-related chronic diseases more accessible, thereby reducing exposure to acquired factors related to Alzheimer's disease and other dementias, as well as reducing the risk of death from Alzheimer's disease and other dementias.

Meanwhile, the Chinese government has increased its financial investment in public health services since the healthcare reforms in 2009, which intending to re-establish the universal healthcare system which would provide affordable basic health care to everyone. 25 Measures such as providing health education and health-management services for patients with chronic diseases may reduce to a certain extent the exposure to risk factors of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. 26 The cohort effect reflects the changes in the risk of disease among different birth cohorts. 22

The results show that for people born in recent years, the risk of mortality for Alzheimer's disease and other dementias has not risen. This may be related to investment in chronic diseases prevention in China in recent decades. The effort has increased awareness of chronic diseases prevention and treatment,27,28 thereby reducing the development of some dementias by controlling chronic diseases and promoting the early detection of mild cognitive impairment. This may also be related to the improvement of education in China in recent decades. China's education expansion policy has contributed to an improvement in the average number of years of schooling, as well as a sharp decrease in education inequality. 29 This education strategy is one way of combating Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. 30

It is worth noting that although we estimated the period effect and cohort effect separately, it is challenging to interpret them separately in the real world due to the confounding effects. 11 Period effects may affect certain age groups differently and may lead to cohort effects. Furthermore, individuals from different cohorts born in different periods may have mixed effects on the period effect.

The number of people suffering from Alzheimer's disease in China exceeded any other country in the world in 2010. 31 For many years before, however, both scholarly research and the media tended to focus on diseases with higher mortality rates in China, such as cardiovascular disease and cancer, 31 leading to a general lack of awareness about the serious consequences of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. The prevalence of dementia in China is comparable to that of high-income countries, but patients do not seek health care as frequently as patients in high-income countries, and throughout the health services there are few who are trained to recognize and manage this disease. 31 Notably, the definition of “death from ad and other dementias” in this study is that ad and other dementias are the earliest disease or injury in a series of pathological events that directly lead to death. When defining the root cause of death, the doctors have received training, and the CDC reviewed the data, verified, and corrected the problems. However, there may be phenomena such as incomplete chain of death causes lead to the root cause of death cannot be determined as Alzheimer's and other dementias, or there is no formal clinical diagnosis for some older adults who have cognitive decline, etc., thus the mortality rate in this result may be underestimated.

These challenges have substantially burdened not just individuals and families, but society as a whole, with emotional, financial, and social impacts. 31 With the continued rise of chronic diseases related to dementia, 32 Alzheimer's disease and dementia will increasingly affect the health of China's elderly. Sufficient resources should therefore be provided at the national, local, family, and individual levels, including the provision of specialized care to ensure timely and appropriate prevention, diagnosis, and treatment.33,34

In addition, public awareness campaigns should be held to eliminate common misunderstandings about dementia. Furthermore, medical staff should be properly trained in the management of dementia, and have the ability to evaluate, diagnose, treat or refer, and to educate patients and their care givers.31,35 A key policy priority should be planning for the long-term care of patients with dementia and to evaluate the delivery mode of community care. 36 And last, more research should be done to improve the understanding of social and environmental risk factors of dementia.31,37-39

It should be noted that there are some limitations to this study. First, we did not include in our analysis those under 40 years old and over 95 years old, given the data included the GBD. Second, this study did not analyze the differences between urban and rural areas in China, again because of the data on mortality for Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias included in the GBD. Considering the high prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia in China’s rural areas, 40 additional analysis is warranted. Finally, the data of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias in this study were estimates at the national macro level, and the macro-level explanations may not be applicable to individuals. Further individual-based research is needed to confirm related hypotheses raised in this study.

Conclusion

Over the past 30 years, the CMR of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias in China has trended upward. Although Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias mortality have decreased among men and women, in terms of annual percentage change, for those aged 45–54 years, the mortality of men aged 60–94 years and women aged 60–79 years has increased. Taking into account China's aging population and the increase in chronic diseases related to Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, the current trend can be expected to place an increasingly heavy burden on China's health care system. Greater systemic efforts are therefore needed to mitigate the increasing impact of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias on China’s elderly.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed the financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported in part by a research grant (72004103) from the National Natural Science Foundation of China.

ORCID iD

Wanyue Dong https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5502-3857

References

- 1.Wong SL, Gilmour H, Ramage-Morin PL. Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias in Canada. Health Rep. 2016;27(5):11-16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patterson C. World Alzheimer Report 2018: The State of the Art of Dementia Research: New Frontiers. London, UK: Alzheimer’s Disease International; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bo Z, Wan Y, Meng SS, et al. The temporal trend and distribution characteristics in mortality of Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia in China: Based on the National Mortality Surveillance System (NMS) from 2009 to 2015. PLoS One. 2019;14(1):e0210621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.GBD . Global, regional, and national burden of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet Neurol 2019;18(1):88-106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yin P, Feng X, Astell-Burt T, et al. Temporal trends and geographic variations in dementia mortality in China between 2006 and 2012. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2016;30(4):348-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.GBD 2019 Diseases Injuries Collaborators . Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396(10258):1204-1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cui F, Shen L, Li L, et al. Prevention of chronic hepatitis B after 3 decades of escalating vaccination policy, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23(5):765-772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu S, Wu X, Lopez AD, et al. An integrated national mortality surveillance system for death registration and mortality surveillance, China. Bull World Health Organ. 2016;94(1):46-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Population and Health Science Data Sharing Platform . The data-center of China public health science. https://www.phsciencedata.cn/Share/en/index.jsp. https://www.phsciencedata.cn/Share/en/index.jsp. Published 2020. Accessed 07/20, 2021.

- 10.Fannon Z, Nielsen B. Age-period-cohort models. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Economics and Finance. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. https://oxfordre.com/economics/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190625979.001.0001/acrefore-9780190625979-e-495. (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Z, Hu S, Sang S, Luo L, Yu C. Age-period-cohort analysis of stroke mortality in China. Stroke. 2017;48(2):271-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gao D, Zou Z, Zhang W, Chen T, Cui W, Ma Y. Age-period-cohort analysis of HIV mortality in China: Data from the global burden of disease study 2016. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):7065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenberg PS, Check DP, Anderson WF. A web tool for age-period-cohort analysis of cancer incidence and mortality rates. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2014;23(11):2296-2302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fang EF, Scheibye-Knudsen M, Jahn HJ, et al. A research agenda for aging in China in the 21st century. Ageing Res Rev. 2015;24(Pt B):197-205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.He X, Song M, Qu J, et al. Basic and translational aging research in China: present and future. Protein & Cell. 2019;10(7):476-484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Institute on Aging . Alzheimer’s Disease Progress Report 2014–2015: Advancing Research Toward a Cure. Bethesda: National Institute on Aging; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mayeux R, Stern Y. Epidemiology of Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lavretsky H, Newhouse PA. Stress, inflammation, and aging. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20(9):729-733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alexopoulos GS. Depression in the elderly. Lancet. 2005;365(9475):1961-1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mazure CM, Swendsen J. Sex differences in Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15(5):451-452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oveisgharan S, Arvanitakis Z, Yu L, Farfel J, Schneider JA, Bennett DA. Sex differences in Alzheimer’s disease and common neuropathologies of aging. Acta Neuropathol. 2018;136(6):887-900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang J, Zhang Y, Luo L, Meng R, Yu C. Global mortality burden of cirrhosis and liver cancer attributable to injection drug use, 1990-2016: An age-period-cohort and spatial autocorrelation analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15(1):170. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15010170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wagstaff A, Yip W, Lindelow M, Hsiao WC. China’s health system and its reform: A review of recent studies. Health Econ. 2009;18(suppl 2):S7-S23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang S, Cheung DSK, Leung AYM. Overview of dementia care under the three-tier long-term care system of China. Public Health Nurs. 2019;36(2):199-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu H, Emsley R, Dunn G. China’s 2009 health reform: What implications could be drawn for the NHS foundation trusts reform? Health Policy and Technology. 2013;2(2):61-68. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ministry of Health . National Basic Public Health Service Standards. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/jws/s3581r/200910/fe1cdd87dcfa4622abca696c712d77e8.shtml?from=singlemessage. Published 2009. Accessed 06/10, 2020.

- 27.Bundy JD, He J. Hypertension and related cardiovascular disease burden in China. Ann Glob Health. 2016;82(2):227-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cai L, Li X, Cui W, You D, Golden AR. Trends in diabetes and pre-diabetes prevalence and diabetes awareness, treatment and control across socioeconomic gradients in rural southwest China. J Public Health. 2018;40(2):375-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang J, Huang X, Liu X. An analysis of education inequality in China. Int J Educ Dev. 2014;37:2-10. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qiu C, Fratiglioni L. Aging without dementia is achievable: Current evidence from epidemiological research. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;62(3):933-942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chan KY, Wang W, Wu JJ, et al. Epidemiology of Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia in China, 1990-2010: A systematic review and analysis. Lancet. 2013;381(9882):2016-2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bai R, Wu W, Dong W, Liu J, Yang L, Lyu J. Forecasting the populations of overweight and obese chinese adults. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes.: Targets Ther. 2020;13:4849-4857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hipgrave D. Perspectives on the progress of China’s 2009 - 2012 health system reform. J Glob Health. 2011;1(2):142-147. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chan KY. A health policy and systems approach to addressing the growing burden of noncommunicable diseases in China. J Glob Health. 2011;1(1):28-31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Allotey P, Reidpath DD, Yasin S, Chan CK, de-Graft Aikins A. Rethinking health-care systems: A focus on chronicity. Lancet. 2011;377(9764):450-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu Q, Chow JC. Exploring the community-based service delivery model: Elderly care in China. Int Soc Work. 2011;54(3). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beaglehole R, Bonita R, Horton R, et al. Priority actions for the non-communicable disease crisis. Lancet. 2011;377(9775):1438-1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Russ TC, Batty GD, Hearnshaw GF, Fenton C, Starr JM. Geographical variation in dementia: systematic review with meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41(4):1012-1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jia L, Quan M, Fu Y, et al. Dementia in China: Epidemiology, clinical management, and research advances. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(1):81-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jia J, Wang F, Wei C, et al. The prevalence of dementia in urban and rural areas of China. Alzheimer's Dementia. 2014;10(1):1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]