Abstract

Objectives

This article aims to examine the association between a shared decision-making (SDM) clinical communication training program and documentation of SDM for patients with life-limiting illness (LLI) admitted to intensive care.

Methods

This article used a prospective, longitudinal observational study in a tertiary intensive care unit (ICU). Outcomes included the proportion of patients with SDM documented on an institutional Goals of Care Form during hospital admission, as well as characteristics, outcomes, and factors associated with an SDM admission.

Intervention

Clinical communication skills training (iValidate) and clinical support program are the intervention for this study.

Results

A total of 325 patients with LLI were admitted to the ICU and included in the study. Overall, 184 (57%) had an SDM admission, with 79% of Goals of Care Form completed by an iValidate-trained doctor. Exposure to an iValidate-trained doctor was the strongest predictor of an ICU patient with LLI having an SDM admission (odds ratio: 22.72, 95% confidence interval: 11.91–43.54, p < 0.0001). A higher proportion of patients with an SDM admission selected high-dependency unit–level care (29% vs. 12%, p < 0.001) and ward-based care (36% vs. 5%, p < 0.0001), with no difference in the proportion of patients choosing intensive care or palliative care. The proportion of patients with no deterioration plan was higher in the non-SDM admission cohort (59% vs. 0%, p < 0.0001).

Conclusions

Clinical communication training that explicitly teaches identification of patient values is associated with improved documentation of SDM for critically ill patients with LLI. Understanding the relationship between improved SDM and patient, family, and clinical outcomes requires appropriately designed high-quality trials randomised at the patient or cluster level.

Keywords: Shared decision-making, Values, Life-limiting illness, Communication, Goal concordant care, Autonomy

1. Introduction

Discordance exists between doctors and patients or surrogates for what information is considered relevant to decision-making in the event of clinical deterioration.[1], [2], [3] Doctors tend to discuss treatments,2,3 whereas patients and surrogates prefer to discuss lifestyle outcomes and the effect of treatment options on what is valued in their lived experience.1,2 Patients, and particularly surrogates, experience decisional conflict when treatments are the focus of goals of care discussions.3 This conflict may manifest as disagreement between doctors and patients or their surrogates or reduction of choices to a binary decision—“wanting everything done” or “do nothing.”[4], [5], [6]

Patients with life-limiting illness (LLI) are commonly admitted to hospital and are at a high risk of deterioration and subsequent intervention-based, complex, end-of-life care. This care is at risk of being burdensome, nonbeneficial, and nonconcordant with patients’ goals and values.7 LLI is an established concept that refers to three clinical trajectories: metastatic or untreatable cancer, end-stage organ failure, and functional decline.[8], [9], [10] Shared decision-making (SDM), where an ethical imperative for respecting patient autonomy6,11 leads to the integration of patient goals and values into treatment decisions and care provided, is advocated in this setting.12 The benefits of SDM, including an association with reduced unexpected intensive care unit (ICU) admissions,13,14 have been described in various clinical contexts.15,16

Operationalising SDM requires several components, including identification and exploration of patient goals and values,11,12 clinician recommendation of treatment options that align with patient values,17 and shared deliberation for treatment decisions.18 Training healthcare professionals is recognised as the most effective intervention for establishing SDM in clinical practice.19 However, there is a lack of evidence regarding the clinical efficacy of teaching strategies.[19], [20], [21]

We have previously described a clinical communication training program that incorporates patient values with concordant medical advice as required components of SDM.19 The primary aim of this study was to examine the association between the implementation of an SDM clinical communication training program and documentation of SDM for patients with LLI admitted to intensive care. The secondary aim was to describe the characteristics, outcomes, and factors associated with SDM.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design, setting, and sample

We performed a longitudinal study in a tertiary ICU at an academic hospital servicing a population of approximately 500 000 people in South Western Victoria, Australia. Ethics approval was obtained from the institutional human research ethics committee before commencing the study. The study included all adult patients with LLI admitted to the ICU between October 2016 and July 2018. The patient cohort included in this study was prospectively identified through daily auditing of the ICU and hospital electronic admission databases by research coordinators. Patients were only included for the index hospital admission.

LLI indicators were adapted from the UK Gold Standards Framework prognostic indicators, the Supportive and Palliative Care Indicators Tool,9 and have been validated in our hospital population.22 Patients were classified into clinical indicators that identify patients who are likely to die in the next 12 months.23 Full details of the indicators are provided in Supplemental Figure 1.1.

2.2. Data collection

Data collected from the electronic medical record included patient demographics, clinical information, admission diagnosis, presence of an advance care plan (ACP), intensive care interventions, hospital outcome, 90-day hospital readmission, and outcome. One-year survival was collected through national death index data linkage. Study data were managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools.24,25

Patients were categorised into one of the two groups: having SDM during their hospital admission (SDM admission) or no SDM during their hospital admission (non-SDM admission). The definition of SDM required all components of an SDM process to be documented on the hospital Goals of Care Form (GOCF) in the electronic medical record during the index hospital admission. The GOCF combines documentation of an SDM process with the institutional “Resuscitation and Treatment Limitations” document and is primarily used to guide care decisions in the event of acute clinical deterioration (Supplemental Figure 1.2). The components of SDM required for patients to be categorised as an SDM admission included: (i) identification of patient values; (ii) medical advice aligned to patient values; and (iii) concordant treatment decision and deterioration plan. The deterioration plan indicated the level of care to be provided in the event of clinical deterioration. These were intensive care, high-dependency care, ward-level care, or palliative care (Supplemental Figure 1.3). Patients with more than one GOCF during the hospital admission were defined as an “SDM admission” if at least one form met the study definition of SDM.

All GOCFs during a patient's index hospital admission were assessed for documentation of SDM components and included in the analysis. The assessment of SDM was performed by SM and YM and reviewed by three clinical investigators (NO, NS, and CC). Information regarding the level of experience and completion of the iValidate communication skills training for medical doctors was collected by cross-reference of data on the form (date, time, and name of the doctor) and the iValidate workshop participant database. GOCFs without signatures or illegible printed names were excluded from analysis.

2.3. Intervention

The iValidate program is an education and clinical support program.14,26 The education program is based on the Calgary-Cambridge framework for clinical communication27 and teaches communication skills for SDM in patients with LLI. It uses evidence-based adult education pedagogy with interactive, small-group scenario-based role-play workshops.27 The education includes instruction and evaluation of documentation of the SDM process on the institutional GOCF (Supplemental Figure 1.2).

The clinical support program included screening and nudges in the daily ICU multidisciplinary meeting; visual aids for staff, visitors, and patients; and regular audit and feedback to staff regarding GOCF documentation. The program commenced in August 2015, with all ICU registrars since 2015 required to complete the iValidate program. The program is accredited by the College of Intensive Care Medicine of Australia and New Zealand and has trained over 400 ICU registrars. In addition, junior medical staff members from medical and surgical specialties and emergency medicine have been trained throughout the organisation during the study period. Consequently, GOCFs are completed by iValidate-trained doctors inside and outside the ICU.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Data were assessed for normality and reported as frequency (%), mean (standard deviation) for normally distributed data, and median (interquartile range) otherwise. Group comparisons were performed using chi-square tests for equal proportion, a student t-test for normally distributed data, and a Wilcoxon rank-sum test otherwise.

Multivariable analysis adjusting for a priori determined variables (age, gender, diagnosis) was performed using generalised linear modelling with a binomial distribution and logit link function, with patients treated as a random effect and results reported as odds ratios (ORs; 95% confidence interval [CI]). Analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA), and a two-sided p value of 0.05 was used to indicate statistical significance.

3. Results

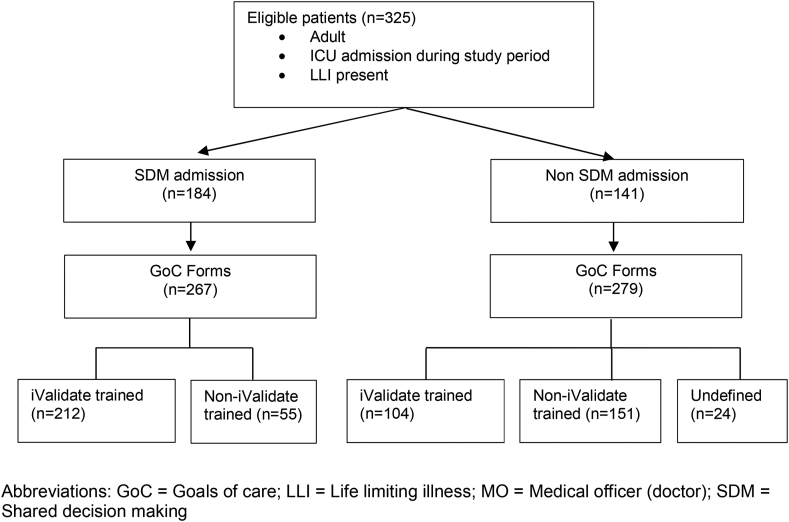

A total of 325 patients with LLI were admitted to the ICU and had 546 GOCFs completed during the study period. One hundred and eighty-four (57%) patients were defined as having an SDM admission, with 267 GOCFs identified in this cohort, of which 212 (79%) were completed by an iValidate-trained doctor. The remaining 141 (43%) patients were defined as having a non-SDM admission, with 279 GOCFs identified, of which 104 (37%) were completed by an iValidate-trained doctor (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Patient flow and Goals of Care Form (GoCF). GoC, Goals of Care; LLI, life-limiting illness; MO, medical officer (doctor); SDM, shared decision-making.

The comparison of demographics and characteristics of patients with an SDM admission to those of a non-SDM admission is provided in Table 1. Patients with an SDM admission were older, less likely to have a cancer admission, more likely to have exacerbation of chronic lung disease, and less likely to have been admitted to the ICU from operating theatres. There was no difference between groups in terms of severity of illness score or ICU interventions.

Table 1.

Demographics and characteristics by shared decision-making status.

| SDM admission | Non-SDM admission | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 184 | 141 | |

| Age | 69.2 ± 11.4 | 64.9 ± 12.8 | 0.002 |

| Female sex | 85 (46.2) | 65 (46.1) | 1.0 |

| APACHE 3 score | 68.6 ± 30.1 | 65.1 ± 29.2 | 0.3 |

| Prehospital accommodation | |||

| Home | 145 (78.8) | 122 (86.5) | 0.07 |

| Residential aged care | 10 (5.4) | 8 (5.7) | 0.9 |

| Other | 29 (15.8) | 11 (7.8) | 0.03 |

| LLI category | |||

| Cancer | 37 (20.1) | 42 (29.8) | 0.04 |

| Frailty | 75 (40.8) | 43 (30.5) | 0.06 |

| Organ failure | 72 (39.1) | 56 (39.7) | 0.9 |

| Admission diagnosis | |||

| Pneumonia | 20 (10.9) | 8 (5.7) | 0.1 |

| Cancer | 11 (6.0) | 21 (14.9) | 0.008 |

| Chronic heart failure | 4 (2.2) | 2 (1.4) | 0.7 |

| Chronic obstructive lung disease | 38 (20.7) | 11 (7.8) | 0.001 |

| Renal failure | 4 (2.2) | 5 (3.5) | 0.5 |

| Neurological | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Infection | 16 (8.7) | 7 (5.0) | 0.2 |

| Frailty/fall | 3 (1.6) | 4 (2.8) | 0.5 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 7 (3.8) | 2 (1.4) | 0.2 |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 3 (1.6) | 4 (2.8) | 0.5 |

| Elective surgery | 19 (10.3) | 28 (19.9) | 0.02 |

| Other | 57 (31.0) | 46 (32.6) | 0.8 |

| ICU admission source | |||

| Emergency department | 81 (44.0) | 48 (34.0) | 0.07 |

| MET call | 39 (21.2) | 20 (14.2) | 0.1 |

| Ward | 28 (15.2) | 32 (22.7) | 0.09 |

| Elective surgery | 9 (4.9) | 29 (20.6) | <0.0001 |

| Other hospital | 26 (14.1) | 10 (7.1) | <0.05 |

| Other | 1 (0.5) | 2 (1.4) | 0.6 |

| ICU treatment | |||

| Mechanical ventilation received | 55 (29.9) | 43 (30.5) | 0.9 |

| Mechanical ventilation duration (days) | 0 [0–12.8] | 0 [0–7.18] | 0.9 |

| Renal replacement therapy | 15 (8.2) | 16 (11.3) | 0.3 |

Note: Data are reported as number (%), mean (± standard deviation), or median [interquartile range].

Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit; LLI, life-limiting illness; SDM, shared decision-making.

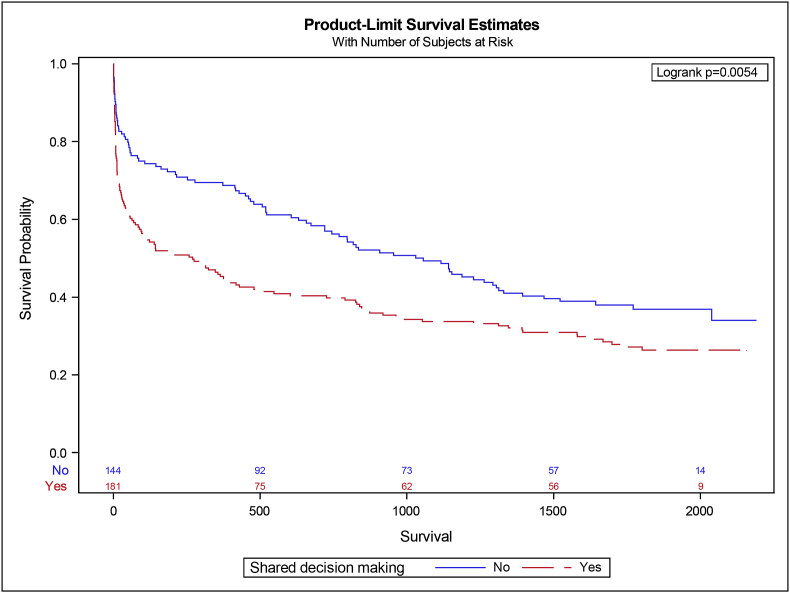

A comparison of outcomes between patients with an SDM admission and non-SDM admission is presented in Table 2. Patients with an SDM admission were more likely to have a medical emergency team call (40% vs. 27%, p < 0.01) and to be referred for palliative care (21% vs. 9%, p = 0.002). The SDM admission cohort had a longer ICU length of stay (2.5 [1.3–4.4] days vs. 2.0 [1.1–3.7] days, p = 0.04) and hospital length of stay (9.8 [5.7–16.4] days vs. 8.0 [4.9–13.4] days, p = 0.04). There was no difference in ICU survival. However, the SDM admission cohort had lower survival for both hospital discharge (67% vs. 80%, p = 0.007) and 1-year survival (Fig. 2). The SDM admission group was less likely to be discharged home (41% vs. 60%, p = 0.001).

Table 2.

Patient outcomes by shared decision-making status.

| SDM admission | Non-SDM admission | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 184 | 141 | |

| Hospital outcomes | |||

| MET call | 74 (40.2) | 38 (27.0) | 0.01 |

| Code blue | 7 (3.8) | 2 (1.4) | 0.2 |

| ICU LOS | 2.52 [1.28–4.41] | 1.99 [1.05–3.69] | 0.04 |

| Hospital LOS | 9.78 [5.76–16.4] | 8.03 [4.94–13.4] | 0.04 |

| ICU survival | 150 (81.5) | 118 (83.7) | 0.6 |

| Hospital survival | 124 (67.4) | 114 (80.2) | 0.007 |

| ICU readmission | 12 (6.5) | 5 (3.5) | 0.2 |

| Palliative care referral | 39 (21.2) | 12 (8.5) | 0.002 |

| 90-day outcomes | |||

| Survival | 95 (55.9) | 90 (70.9) | 0.008 |

| Hospital-free days | 53.7 [0–78.7] | 71.1 [37.2–82.3] | 0.002 |

| Hospital readmission | 66 (35.9) | 64 (45.4) | 0.08 |

| Discharge destination | |||

| Home | 75 (40.8) | 84 (59.6) | 0.001 |

| Residential aged care | 20 (10.9) | 17 (12.1) | 0.7 |

| Rehab | 17 (9.2) | 9 (6.4) | 0.4 |

| Other | 12 (6.5) | 4 (2.8) | 0.1 |

Note: Data are reported as number (%), mean (+ standard deviation) or median [interquartile range].

Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit; LOS, length of stay; MET, medical emergency team; SDM, shared decision-making.

Fig. 2.

Survival analysis of patients by shared decision-making admission status.

The comparison of GOCF documentation for patients with an SDM admission to that of those with non-SDM admission is provided in Table 3. The SDM admission cohort had more GOCFs documented per patient (2 [1–2] vs. 0 [0–1], p < 0.0001) and was more likely to have a GOCF completed by an iValidate-trained doctor (91% vs. 27%, p < 0.0001). The documentation of all components of the SDM process was low for patients in the non-SDM admission cohort (decision-making capacity, 36%; values, goals, and preferences, 23%; and medical advice, 26%). The deterioration treatment decision differed between cohorts, with a higher proportion of the SDM admission cohort selecting high-dependency-level care (29% vs. 12%, p < 0.001) and ward-based care (36% vs. 5%, p < 0.0001), while there was no difference in the proportion of treatment decision for intensive care or palliative care. The proportion of patients with no deterioration plan was higher in the non-SDM admission cohort (59% vs. 0%, p < 0.0001).

Table 3.

Characteristics of goals of care documentation by shared decision-making status.

| SDM | Non-SDM | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 184 | 141 | |

| Before ACP | 45 (24.5) | 28 (19.9) | 0.3 |

| GoCF per patient | 2 [1–2] | 0 [0–1] | <0.0001 |

| GoCF completed by iValidate-trained clinician | 167 (90.8) | 38 (26.9) | <0.0001 |

| Components of GoCF | |||

| Decision-making capacity | 182 (98.9) | 50 (35.5) | <0.0001 |

| Values goals and preferencesa | 184 (100) | 33 (23.4) | <0.0001 |

| Medical advice offereda | 184 (100) | 36 (25.5) | <0.0001 |

| Deterioration treatment decision | |||

| ICU | 35 (19.0) | 25 (17.7) | 0.8 |

| HDU | 54 (29.3) | 17 (12.1) | <0.0001 |

| Ward-based care | 66 (35.9) | 7 (5) | <0.0001 |

| Palliative care | 29 (15.8) | 9 (6.4) | 0.009 |

| Not identified | 0 (0) | 83 (58.9) | <0.0001 |

Note: Data are reported as number (%) or median [interquartile range].

Abbreviations: ACP, advance care plan; GoCF, Goals of Care Form; HDU, high-dependency unit; ICU, intensive care unit; SDM, shared decision-making.

Necessary components of shared decision-making taught in iValidate.

After multivariate analysis, the factors independently associated with an SDM admission were exposure to an iValidate-trained doctor (OR: 22.72, 95% CI: 11.91–43.54, p < 0.0001), increasing age (OR: 1.03, 95% CI: 1.0–1.06, p = 0.03), and a diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (OR: 6.25, 95% CI: 1.58–24.79) or pneumonia (OR: 5.2, 95% CI: 1.22–22.28) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis of shared decision-making versus no shared decision-making.

| Label | Odds ratio univariate | P | Odds ratio multivariate | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | . | 0.0003 | 0.03 | |

| COPD vs. cancer | 6.6 (2.45–17.77) | 6.25 (1.58–24.79) | ||

| Surgery vs. cancer | 1.3 (0.51–3.3) | 1.28 (0.37–4.5) | ||

| Other vs. cancer | 2.31 (1.04–5.14) | 1.69 (0.6–4.78) | ||

| Pneumonia vs. cancer | 4.77 (1.59–14.3) | 5.2 (1.22–22.28) | ||

| Infection vs. cancer | 4.36 (1.38–13.77) | 3.38 (0.77–14.87) | ||

| Age | 1.03 (1.01–1.05) | 0.002 | 1.03 (1–1.06) | 0.03 |

| iValidate-trained doctor | 21.72 (11.58–40.74) | <0.0001 | 22.77 (11.91–43.54) | <0.0001 |

Note: Data are reported as odds ratio (95% confidence interval).

Abbreviation: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

4. Discussion

4.1. Main findings

We found the documentation of goals of care by a doctor trained in an SDM clinical communication training program was the factor most strongly associated with critically ill patients with an LLI participating in SDM during their hospital admission. The characteristics, deterioration plans, and outcomes of patients with an SDM admission differed to non-SDM admission patients. The nature of this relationship and effect of SDM on patient and hospital outcomes require examination through prospective randomised trials.

4.2. Relationship to previous studies

Although SDM is considered crucial for high-quality patient-centred care,28 translation to clinical care is not occurring.19 While the number of training programs for SDM has increased internationally,19 evidence for the best format, method, and content is lacking.29,30 With communication skills training for doctors identified as the most effective intervention to improve SDM,19 a focus on how best to achieve this is required.

This study reports the efficacy of a program that teaches and implements SDM in acute clinical care, emphasises a value-based approach to scaffold the decision-making process, promotes patient autonomy, emphasises doctor and patient or surrogate consensus, and decreases the risk of unconscious steering by clinicians.31,32 The iValidate model has a clear stepwise structured approach to goals of care conversations that is aligned to the documentation. This approach has been operationalised through an evidence-based education framework for communication skills that teaches the process of information gathering from patients or their surrogate before treatment options are discussed.26,27,33

Models for enacting SDM have commonly endorsed discussing treatment options before gathering information regarding patient values.33,34 Discussion of options before understanding what patients value for living well can result in reductionist decisions (such as choosing “everything”) by patients and/or surrogates.[4], [5], [6] Discussing treatment options after exploration of patient values in goals of care conversation increases the likelihood that treatment options are relevant to what the patient values for living well. Initial exploration of patient values encourages doctors to focus clinical information to outcomes rather than treatments12 and is preferred by patients and surrogates in goals of care conversations for potential end-of-life events.2 The SDM program in this study incorporated the documentation of patient values identified before discussion of treatment options into the assessment of SDM.

Checking for mutual understanding at the conclusion of the conversation ensures alignment of values and treatments and avoids mismatched expectations for outcomes. Together with values exploration, the communication model taught in iValidate requires documentation of “consensus”—between doctor and patient and/or surrogate—for the treatment decision and any limitations of care. While this study did not compare teaching models, there was a difference in documentation of patient values and provision of medical advice in the SDM cohort and this was strongly associated with exposure to iValidate-trained doctors. This association supports the theoretical program model and efficacy as a clinical intervention.

The provision of SDM is important for critically ill patients with LLI. In this population, the risk of deterioration or death during hospital admission or subsequent months is high.13 As a result, ensuring care that is offered and provided is concordant with patients’ values, goals, and preferences is crucial. In this study, engagement in an SDM process was associated with both an increase in patients with an LLI choosing care with restrictions in the event of future deterioration and a decrease in patients with no plan for care in the event of future deterioration. This is important as it may prevent a default to intensive care–level support that is discordant with patient values and preferences.

The relationship between SDM and patient choices and outcomes is important from a person-centred, clinical and health utilisation perspective. In this study, an association between an SDM admission, increased hospital length of stay, and decreased long-term survival was observed. The nature of this relationship cannot be established in this study design. It is plausible that the SDM admission group, who were older, with a lower proportion of surgical patients, and more chronic lung disease, had a higher risk of complex care and death. Also, medical staff may have recognised this risk and focussed SDM efforts on this population. It is also possible an SDM approach led to patients choosing or experiencing longer periods of low-intensity hospital stay and reduced survival, through active decisions aligned to their values. From previous work, we identified patients prioritise other values such as dignity and independence over “living as long as possible”4,35,36; therefore, reduced survival may not be considered a bad outcome by some patients.2 This requires exploration through appropriately designed trial methodology.

4.3. Strengths and limitations

While this study described an association between communication training and SDM, not all GOCFs completed by iValidate-trained doctors met SDM criteria. This may represent a longitudinal process that occurs in doctor and patient communication, where the components of SDM are explored and discovered over the course of an ICU or hospital admission. This theory is supported by the increased number of GOCFs in the SDM admission cohort. Also, it is possible that other evidence of SDM conversations was present elsewhere in the patients’ medical record. However, previous research has demonstrated that this is uncommon.13,14,22

Another limitation of this study is the absence of patient voice related to the impact of SDM. We did capture and analyse documentation of patients' expressed values in the GOCF. Also, we did not use a validated measure for SDM, making comparison to other clinical SDM interventions difficult. However, documentation on the GOCF provides clear evidence of the components of SDM and deterioration treatment plans for clinical deterioration. Finally, this was a single-centre study with unique documentation and policies for goals of care documentation. Therefore, external validation issues exist and may not be transferrable to other sites.

5. Conclusions

This study provides evidence that clinical communication training in SDM that explicitly teaches identification of patient values is associated with improved SDM for critically ill patients with LLI. Understanding the relationship between improved SDM and patient, family, and clinical outcomes requires appropriately designed high-quality trials randomised at the patient or cluster level.

Conflict of interest

All authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Credit authorship statement

SM– Planning, data collection, data analysis, primary manuscript development and revision, development of tables and figures, guarantor of overall content

NO – Planning, manuscript development and revision, data analysis, development of tables and figures

DK – Planning, data analysis, manuscript revision

AH – Planning, data analysis, manuscript revision

MB – Data analysis, biostatistics, tables revision, manuscript revision

YM – Data collection, manuscript revision

NS – Planning, manuscript revision

CC – Manuscript revision

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgements

In Memoriam of Prof Trisha L Dunning (AM RN, CDE, MEd, PhD, FACN) who contributed to this body of research and was the primary supervisor for SM. Prof Dunning has been part of the iValidate program from the beginning and played a central role in the planning and development of the research program.

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of ICU project manager Ms Gerry Keeley and ICU research nurses Alison Bone and Tania Elderkin (in Memoriam) who assisted with the data collection for this project. The iValidate educators and Advance Care Planning teams who are passionate about the education of doctors to improve patient-centred care and shared decision-making at Barwon Health are integral to reinforcing the message about value-based conversations.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccrj.2023.04.005

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Fried T.R., Tinetti M.E., Iannone L., O'Leary J.R., Towle V., Van Ness P.H. Health outcome prioritization as a tool for decision making among older persons with multiple chronic conditions. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(20):1854–1856. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.424. 2011/11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hawkins N.A., Ditto P.H., Danks J.H., Smucker W.D. Micromanaging death: process preferences, values, and goals in end-of-life medical decision making. Gerontologist. 2005;45(1):107–117. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heyland D.K., Heyland R., Dodek P., You J.J., Sinuff T., Hiebert T., et al. Discordance between patients stated values and treatment preferences for end-of-life care: results of a multicentre survey. BMJ Support Palliative Care. 2016 doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2015-001056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corke C., Gwini S.-M., Milnes S., de Jong B., Orford N. Treatment choice when faced with high risk of poor outcome–and response to decisions made by surrogates on their behalf. Med Res Arch. 2020;8(11) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scheunemann L.P., Cunningham T.V., Arnold R.M., Buddadhumaruk P., White D.B. How clinicians discuss critically ill patients' preferences and values with surrogates: an empirical analysis. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(4):757. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scheunemann L.P., Ernecoff N.C., Buddadhumaruk P., Carson S.S., Hough C.L., Curtis J.R., et al. Clinician-family communication about patients' values and preferences in intensive care units. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(5):676–684. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glass K.E., Wills C.E., Holloman C., Olson J., Hechmer C., Miller C.K., et al. Shared decision making and other variables as correlates of satisfaction with health care decisions in a United States national survey. Patient Educ Counsel. 7//2012;88(1):100–105. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomas K., et al. 2014. The National GSF Centre's guidance for clinicians to support earlier recognition of patients nearing the end of life.http://www.goldstandardsframework.org.uk/cd-content/uploads/files/General%20Files/Prognostic%20Indicator%20Guidance%20October%202011.pdf 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Highet G., Crawford D., Murray S.A., Boyd K. Development and evaluation of the supportive and palliative care indicators tool (SPICT): a mixed-methods study. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2014;4(3):285–290. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2013-000488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lynn J. Serving patients who may die soon and their families: the role of hospice and other services. JAMA. 2001;285(7):925–932. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.7.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gulbrandsen P., Clayman M.L., Beach M.C., Han P.K., Boss E.F., Ofstad E.H., et al. Shared decision-making as an existential journey: aiming for restored autonomous capacity. Patient Educ Counsel. 2016;99(9):1505–1510. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mapes M.V., DePergola P.A., McGee W.T. Patient-centered care and autonomy: shared decision-making in practice and a suggestion for practical application in the critically ill. J Intensive Care Med. 2020;35(11):1352–1355. doi: 10.1177/0885066619870458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orford N.R., Milnes S., Simpson N., Keely G., Elderkin T., Bone A., et al. Effect of communication skills training on outcomes in critically ill patients with life-limiting illness referred for intensive care management: a before-and-after study. BMJ Support Palliative Care. 2017 doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2016-001231. bmjspcare-2016-001231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orford N.R., Milnes S.L., Lambert N., Berkeley L., Lane S.E., Simpson N., et al. Prevalence, goals of care and long-term outcomes of patients with life-limiting illness referred to a tertiary ICU. Crit Care Resuscitat. 2016;18(3):181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aggarwal Y., Baharani J. End-of-life decision making: withdrawing from dialysis: a 12-year retrospective single centre experience from the UK. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2014;4(4):368–376. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2013-000554. December 1, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenwax L., McNamara B., Murray K., McCabe R., Aoun S., Currow D. Hospital and emergency department use in the last year of life: a baseline for future modifications to end-of-life care. Med J Aust. 2011;194(11):570–573. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2011.tb03106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vermunt N., Elwyn G., Westert G., Harmsen M., Olde Rikkert M., Meinders M. Goal setting is insufficiently recognised as an essential part of shared decision-making in the complex care of older patients: a framework analysis. BMC Fam Pract. 2019/06/06 2019;20(1):76. doi: 10.1186/s12875-019-0966-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elwyn G., Vermunt N.P.C.A. Goal-based shared decision-making: developing an integrated model. J Patient Exp. 2020;7(5):688–696. doi: 10.1177/2374373519878604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Légaré F., Adekpedjou R., Stacey D., Turcotte S., Kryworuchko J., Graham I.D., et al. Interventions for increasing the use of shared decision making by healthcare professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;7 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006732.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.France Lé garé P.T.-L. Twelve myths about shared decision making. Patient Educ Counsel. 2014;96:281–286. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Truog R. Translating research on communication in the intensive care unit into effective educational strategies. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(3):976–977. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181cc1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Milnes S., Orford N.R., Berkeley L., Lambert N., Simpson N., Elderkin T., et al. A prospective observational study of prevalence and outcomes of patients with Gold Standard Framework criteria in a tertiary regional Australian Hospital. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2015;9:92–99. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2015-000864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lunney J.R., Lynn J., Hogan C. Profiles of older medicare decedents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(6):1108–1112. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris P.A., Taylor R., Minor B.L., Elliott V., Fernandez M., O'Neal L., et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inf. 2019;95 doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harris P.A., Taylor R., Thielke R., Payne J., Gonzalez N., Conde J.G. A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inf. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simpson N., Milnes S., Martin P., Phillips A., Silverman J., Keely G., et al. Validate: a communication-based clinical intervention in life-limiting illness. BMJ Support Palliative Care. 2019 doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2018-001669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kurtz S., Silverman J., Draper J. CRC Press; 2016. Teaching and learning communication skills in medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Agbadjé T.T., Elidor H., Perin M.S., Adekpedjou R., Légaré F. Towards a taxonomy of behavior change techniques for promoting shared decision making. Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/s13012-020-01015-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berkhof M., van Rijssen H.J., Schellart A.J., Anema J.R., van der Beek A.J. Effective training strategies for teaching communication skills to physicians: an overview of systematic reviews. Patient Educ Counsel. 2011;84(2):152–162. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Diouf N.T., Menear M., Robitaille H., Guérard G.P., Légaré F. Training health professionals in shared decision making: update of an international environmental scan. Patient Educ Counsel. 2016;99(11):1753–1758. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Austin C.A., Mohottige D., Sudore R.L., Smith A.K., Hanson L.C. Tools to promote shared decision making in serious illness: a systematic review. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(7):1213–1221. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dale D.C. Poor prognosis in elderly patients with cancer: the role of bias and undertreatment. J Support Oncol. 2003;1(4 Suppl 2):11–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Makoul G., Clayman M.L. An integrative model of shared decision making in medical encounters. Patient Educ Counsel. 2006;60(3):301–312. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elwyn G., Frosch D., Thomson R., Joseph-Williams N., Lloyd A., Kinnersley P., et al. Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(10):1361–1367. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2077-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Milnes S., Corke C., Orford N., Bailey M., Savulescu J., Wilkinson D. Patient values informing medical treatment: a pilot community and advance care planning survey. BMJ Support Palliative Care. 2017 doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2016-001177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Milnes S.L., Mantzaridis Y., Simpson N.B., Dunning T.L., Kerr D.C., Ostaszkiewicz J.B., et al. Values, preferences and goals identified during shared decision making between critically ill patients and their doctors. Crit Care Resuscitat. 2021;23(1):76–85. doi: 10.51893/2021.1.OA7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.