Abstract

Necrosis is a localized area of tissue death followed by degradation of tissue by hydrolytic enzymes released from the dead cells, resulting in swelling of organelles, rupture of the plasma membrane, eventual cell lysis, and leakage of intracellular contents into the surrounding tissue. It is always accompanied by an inflammatory reaction. Necrosis is caused by various factors such as hypoxia, physical factors, chemical agents, immunological agents, and microbial agents. Still now, there is no literature review regarding the necrotic lesions of the oral cavity. In this paper, the oral lesions associated with necrosis are categorized under the headings such as odontogenic cysts, odontogenic tumors, salivary gland pathology, and epithelial malignancies. In addition, the histopathological significance of necrosis in oral lesions has been discussed. By suggesting that spotting necrosis in the histopathology aids in determining the diagnosis, tumor behavior, and prognosis of oral lesions.

Keywords: Histopathology, necrosis, oral lesions

INTRODUCTION

Cells are active participants in their environment. Cell injury occurs when cells experience extreme stress to the point or when they are exposed to inherently damaging agents or have intrinsic abnormalities that are harmful to them. Injury may develop through a stage that can be reversed or end with cell death.[1] Cell death is a process, which leads to a point of no return. Necrosis was derived from the Greek word nekrosis, which meant “death.”[2] However, cell death differs from necrosis. Necrosis is a pathological process that follows cell death and is visible to the naked eye, while cell death starts microscopically.

Concepts of necrosis

Necrosis may begin as a result of a process known as “oncosis.” The term oncosis is derived from the Greek word ónkos, which means swelling. Oncosis occurs when the mitochondria within a cell are damaged beyond recovery by toxins or hypoxia, which results in swelling of the cell organelles, and plasma membrane rupture. Followed by, the initiation of autolysis occurs through the liberation of hydrolytic enzymes from lysosomes and the spillage of intracellular contents into the surrounding tissue leading to tissue damage.[1]

Unlike apoptosis, which is caused by intrinsic signals, necrosis is caused by an overwhelming noxious stimulus from outside the cell such as hypoxia, physical agents, chemical agents, biological agents, or immunological reactions. It is almost always associated with inflammatory responses due to the release of heat shock proteins, uric acid, ATP, DNA, and nuclear proteins, which cause inflammasome activation and the secretion of the proinflammatory cytokine interleukin-1 beta (IL1). Pathways of signal transduction and catabolic mechanisms may be involved in the precise control of necrotic cell death.[3]

There is growing evidence that caspase-independent cell death pathways are active in physiological and pathological conditions, despite the long-held belief that necrosis only happens in extreme situations such as severe hypoxia and hyperthermia. Necrosis has a physiological function in several signaling events, including ovulation, the death of chondrocytes involved in bone growth along the long axis, intestinal cell turnover, and several pathological conditions such as Excitotoxicity, Ischemia-Reperfusion injury, Bacterial and viral infections.[3]

Necroptosis, pyroptosis, and ferroptosis are a few examples of the several types of controlled necrosis that have been identified.[4] Normally, necrosis is not associated with caspase activation. Toll-like receptor (TLR)-3 and TLR-4 agonists, tumor necrosis factor (TNF), specific microbial infections, and T-cell receptors can all lead to necroptosis, a type of necrosis that causes rupturing of dead cells and releasing intracellular components by triggering an innate immune response.[5] Caspases involved in pyroptosis, a recently identified mode of programmed cell death, are responsible for this process. Reactive oxygen species accumulate to hazardous levels as a result of the iron-dependent cell death process known as ferroptosis.[6] Ferroptosis can be caused by phospholipid peroxidation and iron metabolism dysregulation.[7]

The changes that occur in the nucleus in necrosis are 1. shrinking of the nucleus (pyknosis) caused by water loss from the nucleus to the cytoplasm. 2. Karyolysis (the nuclear chromatin appears to be dissolved and gradually fades from sight). 3. Karyorrhexis (fragmentation of nucleus).[1]

Cytoplasmic changes occur in necrosis consist of the release of autolytic enzymes, which rapidly dissolve intracellular organelles, giving the cytoplasm a homogeneous appearance that becomes intensely eosinophilic, resulting in loss of cellular features and tissue architecture.[2]

Types of necrosis

Many morphologically distinct types of tissue necrosis, namely, coagulative, liquefactive, caseous, gangrenous, which can be dry or wet, fat, and fibrinoid, may offer clues regarding the underlying etiology.[1]

Coagulative necrosis, in which the structure of the cell is maintained. Under microscope, the cells exhibit enucleation, eosinophilia, and intact structure.

Liquefactive necrosis: When hydrolytic enzymes break down dead cells, they lose their structural integrity and change into a viscous mass. This is known as liquefactive necrosis. Most bacterial infections also have this appearance, and the buildup of such necrotic material is known as pus.

The term “caseous necrosis” refers to the whitish color of the necrotic area, and the word “caseous” means “cheese-like.” This necrosis takes place in tuberculous infection, and the necrotic area is referred to as granuloma.

Fat necrosis occurs when pancreatic enzymes are released, causing the fat cells in the peritoneal cavity to liquefy. These liquefied fat cells then combine with calcium to generate areas that are white and chalky, a process known as saponification. On microscopic examination, this appears as basophilic calcium deposits on the edges of the necrotic fat cells.

Fibrinoid necrosis: This kind of necrosis damages blood vessels because immune complexes that have accumulated inside the blood vessel walls generate fibrin leaks. This discoloration is visible as an amorphous bright pink substance.[4]

Gangrenous necrosis is a clinical term for ischemic necrosis of the limbs. It comes in two varieties: dry (ischemia causing coagulative necrosis) and wet (ischemia with superimposed bacterial infection leading to liquefactive necrosis).

Necrosis has also been observed in oral lesions, either as a pathognomonic finding or as one of the findings. In this paper, the oral lesions associated with necrosis are categorized under the following headings.[8,9,10,11]

Categorization of necrosis in various oral lesions

1. Pulpal and periodontal diseases

Pulpitis, necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (NUG), necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis (NUP).

2. Chemical injuries

Aspirin, phenol, hydrogen peroxide.

3. Infections

Bacterial—Diphtheria, syphilis, tuberculosis, noma, leprosy, cat scratch disease, pyostomatitis vegetans.

Viral—HSV, HZV, herpangina, hand, foot, and mouth disease, measles, covid.

Fungal—Mucormycosis, coccidioidomycosis, sporotrichosis, aspergillosis.

4. Soft tissue tumors

Lipoma, Kaposi's sarcoma, benign fibrous histiocytoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, hemangiopericytoma.

5. Odontogenic cysts and tumors

Radicular cyst, calcifying odontogenic cyst, simple bone cyst, ameloblastic carcinoma, clear cell odontogenic carcinoma, and ghost cell odontogenic carcinoma.

6. Epithelial malignancy

Squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, sino nasal undifferentiated carcinoma.

7. Salivary gland lesions

Pleomorphic adenoma, Warthin's tumor, canalicular adenoma, sialoblastoma, sebaceous carcinoma, mucoepidermoid carcinoma, oncocytic carcinoma, small-cell carcinoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma, Carcinoma ex-pleomorphic adenoma, adenocarcinoma, oncocytoma, salivary duct carcinoma, necrotizing sialo metaplasia, necrotizing sialadenitis, myoepithelial carcinoma.

8. Bone lesions

Osteomyelitis, osteonecrosis, giant cell tumor of bone, osteosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, cemento-osseous dysplasia, chondroblastoma, chondrosarcoma.

9. Dermatological lesions

Erythema multiforme, Steven-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, systemic lupus erythematosus, discoid lupus erythematosus, paraneoplastic pemphigus.

10. Allergic and immunological diseases

Wegener's granulomatosis, recurrent aphthous ulcers, midline lethal granuloma, Bechet syndrome.

11. Diseases of the muscle

Myasthenia gravis, focal myositis.

12. T-cell neoplasms

Extranodal NK/t-cell lymphoma.

13. Miscellaneous—

Anesthetic necrosis, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, electric burn.

Mechanisms of necrosis in various oral lesions

Pulpal and periodontal diseases

Pulpitis

Inflammatory edema compresses the blood vessels of the pulp and the pulp undergoes ischemic necrosis.[9]

NUG, NUP

When the patient's immune system is compromised, micro-organisms, particularly fusobacteria and spirochete species, produce inflammation, which promotes the proliferation of the micro-organisms and eventually results in the necrosis of the supporting tissues of the teeth.[12]

Chemical injuries

Aspirin, phenol, hydrogen peroxide (Coagulation of proteins).[9]

Infections

Bacterial—As soon as the bacteria enter the body, they start to multiply and release toxins that damage tissue and reduce blood supply to the area, causing necrosis.[9]

Viral—The underlying mechanism seems to be vasculitis brought on by a viral infection, which may begin in the neurovascular bundles of the trigeminal nerve branches and spread to neighboring vessels with persistent infection. As a result, the tissue supplied by the damaged artery may therefore develop localized ischemic necrosis.[13]

Fungal—The fungus invades the blood vessels and proliferates leading to thrombosis that subsequently causes necrosis of hard and soft tissues.[14]

Necrosis in neoplasms

Necrosis occurs in neoplasms may be due to

Inadequate nutrient supply to tumor cells as a result of an imbalance between tumor growth and angiogenesis.

The host's cytotoxic immune response to the tumor.

Downregulation of programmed (apoptotic) cell death by the tumor itself.[15]

In epithelial malignancy, it is postulated that vascular collapse, high interstitial pressure, and/or rapid tumor development exceeding its blood supply result in persistent ischemia (i.e., hypoxia, low pH, low glucose, and high lactate) within tumors, which leads to tumor necrosis.

The most prevalent cancer-related illness, anemia, further diminishes the blood's ability to transport oxygen. Mitosis failure or dysregulation, which results in cell death, is thought to cause mitotic catastrophe. Researchers suggested that the tumor necrosis seen in high-grade carcinomas may be caused by a mitotic catastrophe brought on by hypoxic stress.[16]

Significance of necrosis in oral lesions

The presence of necrosis in various oral lesions is listed in Table 1 as either:

Table 1.

Significance of necrosis in oral lesions

| Necrosis as a Pathognomonic Finding | Necrosis as an Indicator of Aggressive Behavior | Necrosis as a Prognostic Indicator |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Tuberculosis 2. Osteomyelitis 3. Necrotizing sialometaplasia and necrotizing sialadenitis. 4. Salivary duct carcinoma. 5. Mucormycosis. 6. Erythema multiforme. 7. Osteonecrosis 8. Aspergillosis 9. NUG 10. Wegener's granulomatosis. |

1. Adenoid cystic carcinoma. 2. Squamous cell carcinoma 3. Clear cell odontogenic carcinoma. 4. Mucoepidermoid carcinoma. 5. Carcinoma ex-pleomorphic adenoma. |

1. Ameloblastic carcinoma. 2. Ewing's sarcoma and osteosarcoma. 3. Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma. 4. Steven-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. |

I. Necrosis as a pathognomonic finding

Among the above said oral lesions, some of them are listed below showing necrosis as a pathognomonic finding which is very helpful in the diagnosis of oral lesions.

1. Tuberculosis

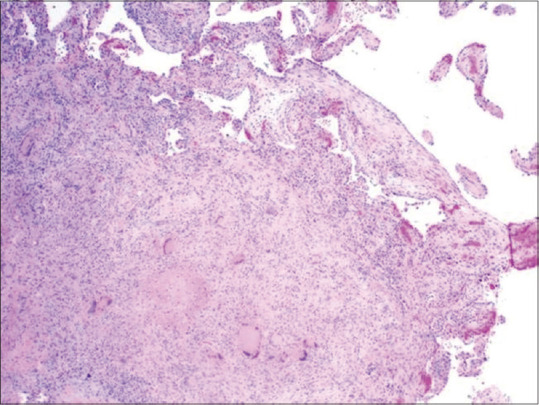

Caseous necrosis, which is considered to be the pathophysiological hallmark of tuberculosis, is caused by the death of macrophage cells by Mycobacterium tuberculosis.[9] The peculiar histopathologic appearance is caused by a cell-mediated hypersensitivity reaction.[17] Formation of granuloma exhibiting foci of caseous necrosis surrounded by lymphocytes, epithelioid cells, and multinucleated giant cells were shown in Figure 1.[18]

Figure 1.

Histopathological image showing tuberculosis characterized by the formation of granuloma exhibiting foci of caseous necrosis surrounded by lymphocytes and Langhans giant cells (H&E stain, ×100) (courtesy of pathologyoutlines.com. https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/imgau/lungnontumorTBMicroLi2.jpg)[18]

2. Osteomyelitis

The infection causes the marrow tissue to become acutely inflamed, and the resulting inflammatory exudate spreads throughout the marrow cavities. This results in thrombosis, blood flow obstruction, and necrosis of the bone by compressing blood vessels in the bone, sequestrum formation. A sequestrum is a fragment of necrotic bone that has disintegrated from the surrounding healthy tissue and is surrounded by pus.[9] An involucrum, or reactive shell of new bone, develops around the sequestrum. The pus is formed by the liquefaction of necrotic tissue, dead and dying inflammatory cells, and bacteria, and it may fill the marrow spaces.[19] According to histopathology, necrotic bone makes up the majority of the lesion.[9] The bone exhibits bacterial colonization, peripheral resorption, and a loss of the osteocytes from their lacunae. Necrotic debris and inflammatory infiltration can be visible around the bone's edge and in the Haversian canals.[9]

3. Necrotizing sialo metaplasia and Necrotizing sialadenitis

The histological feature of the lesion is reflected in the name necrotizing sialometaplasia (NS). The coagulation-induced necrosis of glandular acini and squamous metaplasia of its ducts are the microscopic characteristics of NS.[20] There is mucin pooling, and the inflammatory infiltration is composed of neutrophils, macrophages, and less frequently, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils.[20]

The prominent squamous metaplasia in the regenerating necrotic acini and ducts found in NS is the fundamental histological distinction between NS and necrotizing sialadenitis. Microscopy in necrotizing sialadenitis reveals ductal shrinkage and loss, although squamous metaplasia is typically little or non-existent.[21]

4. Salivary duct carcinoma

Histopathologically, the growth pattern is cribriform, with central comedo necrosis and tumor cell proliferation.[22] The eosinophilic cytoplasm is in abundance, and the tumor cells contain large pleomorphic nuclei with prominent nucleoli. Salivary duct cancer is typically diagnosed by comedo necrosis.[23] A type of necrosis that affects the glands and is characterized by central luminal inflammation and devitalized cells; which may undergo calcification similar to ductal carcinoma of the breast. The intraductal component has fenestrated Roman bridge-like enlarged salivary ducts without a clear lobular arrangement.[23]

5. Mucormycosis

Extensive necrosis with numerous large (6–30 μm in diameter), branching, and non-septate hyphae at the periphery are seen upon histopathologic examination of the lesional tissue.[24] The hyphae typically branch at 90-degree angles. Without a doubt, the propensity of fungi for invasion of small blood vessels accounts for the significant tissue damage and necrosis associated with this disease. Due to the disruption of the normal blood flow to the tissue, infarction, and necrosis occur. Thus, angioinvasion with vessel thrombosis and tissue necrosis is the pathological hallmark of mucormycosis.[25]

6. Erythema multiforme

The earliest pathological feature of drug hypersensitivity-related reactions is keratinocyte necrosis. Necrotic basal keratinocytes may be seen in association with subepithelial or intraepithelial vesiculation.[26] The characteristic “target” or “iris” lesion, which is the pathognomonic feature of EM, is a skin lesion with a central blister or necrosis with concentric rings of varying color.[27]

7. Osteonecrosis

Presence of necrotic bone, osteocyte loss, and empty lacunae are the hallmarks of osteonecrosis of the jaws.[28] A typical pattern of cell death and the complex process of bone production and resorption defines osteonecrosis.[28]

8. Aspergillosis

Black or yellow necrotic tissue on an ulcer base over the palate or in the posterior tongue is the characteristic feature of oral aspergillosis.[29] Invasive aspergillosis tissue sections display a variety of branching, septate hyphae that range in size from three to four μm. These hyphae have the propensity to infiltrate nearby tiny blood arteries (arterioles) branch out at an acute angle.[30] Aspergillosis hyphae toxins aid in blood vessel wall penetration and cause thrombosis, which causes infarction and necrosis. Vascular occlusion frequently causes the distinctive pattern of necrosis that is associated with this disease. In addition to necrosis, a granulomatous inflammatory response might be anticipated in the immunocompetent host.[30]

9. Necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis

The characteristic clinical feature is painful necrosis of the interdental papillae and the gingival margins, and the formation of craters covered with a gray pseudo membrane.[31] The clinical presentation of ANUG reflects its histopathology.[31] From the surface to the deeper levels of the lesion, four distinct layers have been described by (Listgarten et al. 1965).[32] They include 1. A bacterial area of fibrous mesh made up of epithelial cells, leukocytes, and a variety of bacterial cells, such as rods, fusiform bacteria, and spirochetes, are the most superficial. 2. There is a neutrophil-rich zone that is deeper and contains more leukocytes, spirochetes, and bacterial cells. 3. Necrotic zone with spirochetes, fusiform bacteria, and fragmented cells. 4. Spirochetes have infiltrated the deepest layer.[32]

10. Wegener's granulomatosis

Wegener's granulomatosis appears as a pattern of mixed inflammation centered around the blood vessels. Transmural inflammation is seen in involved vessels, and there are frequent areas of strong neutrophil infiltration, necrosis, and nuclear dust as well (leukocytoclastic vasculitis).[33] A variable mixture of histiocytes, lymphocytes, eosinophils, and multinucleated giant cells make up the inflammatory cellular infiltrate in the connective tissue adjacent to the vessel.[33]

II. Necrosis may act as an indicator of aggressive behavior in tumors

In addition to this, necrosis has a significant role in indicating aggressive behavior as well as prognosis in some tumors.

Solid tumors can grow to a particular size before developing poor vascularization in their core parts, which leads to tumor necrosis. Due to poor vascularization and accompanying metabolic stresses such as hypoxia and food starvation, foci of cell death are frequently seen in the core regions of solid tumors. Since the morphology of dead tumor cells appears to be necrotic, these foci of cell death are referred to as tumor necrosis. Tumor hypoxia, an important hallmark of aggressive cancers, is related to a more stimulatory microenvironment with increased angiogenesis and inflammation as co-existing responses. Tumor necrosis is commonly associated with aggressive tumor development and metastasis.[6] Tumor necrosis has been repeatedly associated with larger, higher grade tumors, and tumors with higher proliferative activity and it is believed that tumor necrosis represents an indirect indicator of biologically aggressive tumor behavior.[6]

1. Adenoid cystic carcinoma (AdCC)

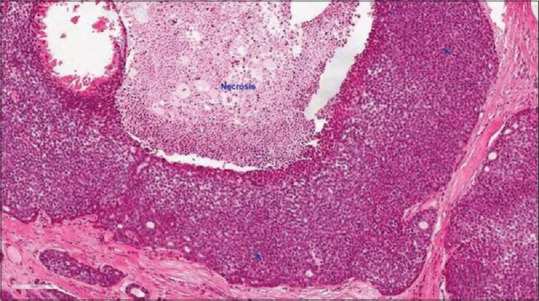

A high-grade malignant salivary gland tumor is nearly often accompanied by aggressive clinical behavior. Both the tubular and cribriform types of AdCC have a less aggressive clinical behavior than the solid variant.[34] Histopathologically, regions of necrosis as well as cellular pleomorphism and mitoses were shown in Figure 2,35] which are typically absent in other forms of AdCC and may be observed in the center of solid tumor islands.[36]

Figure 2.

Histopathological image showing Adcc characterized by tumor necrosis, frequent mitoses (arrows) and marked nuclear atypia with prominent central nucleoli (H&E stain, ×200) (courtesy of pathologyoutlines.com, https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/imgau/salivaryglandsadenoidcysticXu05new.jpg)[35]

2. Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)

Tumor necrosis is a common occurrence in aggressive cancers when tumor development exceeds the rhythm of neovascularization. Tumor necrosis is frequently accompanied by a chronic inflammatory state, which may lead to aggressive tumor activity.[37] Extended histological analyses that include tumor/stroma ratio, immune infiltration at the front of invasion, tumor budding, and tumor necrosis can be a straightforward, approachable strategy to gather more data on tumor aggressiveness in the skin and mucosal SCC affecting the head and neck regions.[37]

3. Clear cell odontogenic carcinoma (CCOC)

The recurrence cases of CCOC demonstrated localized tumor necrosis, indicating its tumor grade advancement. According to this finding, histological necrosis in CCOC may serve as a sign of aggressive behavior.[38]

4. Mucoepidermoid carcinoma (MEC)

Several histopathological parameters include intra-cystic component of <20%, four or more mitotic figures per ten high-power fields, neural invasion, necrosis, and cellular anaplasia, were evaluated for their potential relevance in tumor behavior in high-grade MEC.[38] Therefore, the evaluation of tumor necrosis may be helpful in estimating the aggressive behavior of MEC.[39]

5. Carcinoma ex-pleomorphic adenoma (CA-ex-PA)

Both the benign and malignant PA components can be seen in CA-ex-PA's histopathological characteristics. Perhaps even the PA component of CA-ex-PA has played a central role, along with a few areas of malignant transformation characterized by nuclear pleomorphism, aberrant mitotic patterns, hemorrhage, and necrosis was seen. Necrosis, severe stromal hyalinization, hypercellularity, cellular atypia, enhanced mitotic activity, and cellular infiltration to the capsular zone are histopathological findings that are frequently associated with malignant transformation in PA.[40] Clinically aggressive behavior from the cancer component may be possible.[40] A necrotic center, thick, uneven walls, and infiltrating margins on CT were characteristics of the aggressive area in the carcinoma ex-pleomorphic adenoma. Therefore, it was believed that the image's uneven ring enhancement reflected this histopathologic state.[41]

III. Necrosis as a prognostic indicator

It is believed that tumor necrosis, which is frequently associated with aggressive tumor growth and metastasis, is thought to be an indication of poor prognosis in patients with breast, lung, and kidney cancer. Tumor necrosis has been associated with aggressive tumor behavior and decreased survival in patients with small-cell lung carcinoma,[42] glioblastoma,[43] small hepatocellular carcinoma,[44] gastrointestinal stromal tumor,[45] and malignant mesothelioma.[46]

Necrosis also has prognostic significance in oral lesions and is listed below.

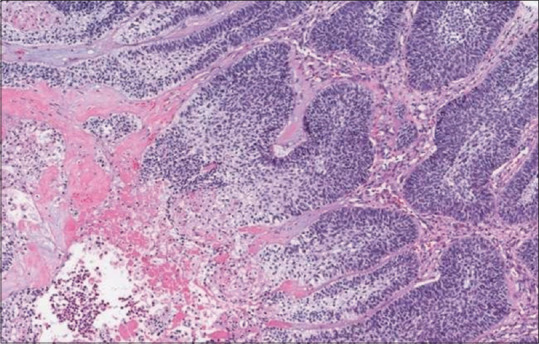

1. Ameloblastic carcinoma (AC)

AC secondary type appears to be associated with recurrence and mortality, implying that it is more aggressive than AC primary type. In the AC secondary type, tumors with clear cells and those with plexiform pattern, hyperchromatism, mitosis, and necrosis were linked to higher degree of recurrence and death.[47] Depending on the type of AC, the histological characteristics may have varied prognostic significance. AC exhibiting tumor necrosis were shown in Figure 3.[48] From the above findings, necrosis may have prognostic importance.[47]

Figure 3.

Histopathological image showing ameloblastic carcinoma exhibiting tumor necrosis. (H&E stain, ×200) (courtesy of pathologyoutlines.com, https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/imgau/mandiblemaxillawhoMagliocca1b.jpg)[48]

2. Ewing's sarcoma and Osteosarcoma

The correlation of the histopathologic tumor response with clinical outcome is a well-established routine investigation in patients with osteosarcoma and Ewing's sarcoma. The Huvos grading system provides a semi-quantitative histological evaluation of the tumor response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in which the amount of necrosis relative to the remaining viable tumor is reported.

The four grades included were

Grade 1: little or no necrosis.

Grade 2: necrosis of 50%–90%.

Grade 3: necrosis between 90% and 99%.

Grade 4: 100% necrosis.

The necrosis of tumor resection, especially when >90%, is regarded as a powerful positive prognostic indicator for survival in patients with high-grade bone sarcomas.[49] Thus, effective stratification of these patients using a histological scoring system is useful and plays an important role in the management of these patients.[49]

3. Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma.

Tumor necrosis is associated with a worse prognosis in several solid cancers. The degree of tumor necrosis influenced outcome in NK/T-cell lymphoma patients.[50] Tumor necrosis and complete resection are concluded to be novel independent prognostic factors in patients with upper aerodigestive tract.[50]

4. Steven-johnson syndrome and Toxic epidermal necrolysis

There are few apoptotic keratinocytes in the epithelium in the early stages of Steven-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermolysis necrosis, which quickly progress to full-thickness necrosis with subepidermal detachment.[51] Patients with Steven-Johnson syndrome have a mortality rate of five to ten %, while those with toxic epidermal necrolysis have a mortality rate of 30–40%, depending on the extent of mucocutaneous necrosis.[51]

CONCLUSION

Necrosis is a localized area of tissue death caused by hydrolytic enzymes secreted from the dead cells. In this review, we have analyzed histopathologically the necrosis and its significance in various oral lesions. Usually, necrosis is an ignored part, but we have highlighted its impact on three aspects such as diagnosis, tumor behavior, and prognosis of various oral lesions. We conclude that spotting necrosis in the histopathology aids in determining the diagnosis, tumor behavior, and prognosis of oral lesions.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kumar V, Abbas AK, Aster JC, Cotran RS, Robbins SL. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2015. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zong WX, Thompson CB. Necrotic death as a cell fate. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1–15. doi: 10.1101/gad.1376506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duprez L, Vanlangenakker N, Festjens N, Van Herreweghe F, Vanden Berghe T, Vandenabeele P. Necrosis: Molecular mechanisms and physiological roles. In: Yin X-M, Dong Z, editors. Essentials of Apoptosis : A Guide for Basic and Clinical Research. 2nd ed. New York, NY, USA: Humana Press; 2009. pp. 599–633. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khalid N, Azimpouran M. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Jan, Necrosis. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557627/ . [Last accessed on 2023 Mar 06] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu Z, Jiang N, Su W, Zhuo Y. Necroptosis: A novel pathway in neuroinflammation. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:701564. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.701564. 10.3389/fphar.2021.701564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu ZG, Jiao D. Necroptosis, tumor necrosis and tumorigenesis. Cell Stress. 2019;4:1–8. doi: 10.15698/cst2020.01.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang D, Li Y, Du C. Evidence of pyroptosis and ferroptosis extensively involved in autoimmune diseases at the single-cell transcriptome level. J Transl Med. 2022;2:363. doi: 10.1186/s12967-022-03566-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gnepp DR, Ellis GL, Auclair PL. Surgical Pathology of the Salivary Glands. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1991 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rajendran A, Sivapathasundharam B, Shafer WG. 7th ed. New Delhi: Elsevier; 2012. Shafer's Text Book of Oral Pathology. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, Bouquot JE. 3rd ed. St. Louis Mo: Saunders/Elsevier; 2009. Text book of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gnepp DR. 2nd ed. Elsevier: 2009. Diagnostic Surgical Pathology of the Head and Neck. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Novak MJ. Necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:74–8. doi: 10.1902/annals.1999.4.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaminskyy V, Zhivotovsky B. To kill or be killed: How viruses interact with the cell death machinery. J Intern Med. 2010;267:473–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2010.02222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Narayanan Ml S, Narayanan CD, Kindo AJ, Arora A, Haridas PA. Fatal fungal infection: The living dead. J Surg Case Rep. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1093/jscr/rju104. rju104. 10.1093/jscr/rju104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lotfi R, Kaltenmeier C, Lotze MT, Bergmann C. Until death do us part: Necrosis and oxidation promote the tumor microenvironment. Transfus Med Hemother. 2016;43:120–32. doi: 10.1159/000444941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caruso RA, Branca G, Fedele F, Irato E, Finocchiaro G, Parisi A, et al. Mechanisms of coagulative necrosis in malignant epithelial tumors (Review) Oncol Lett. 2014;8:1397–402. doi: 10.3892/ol.2014.2345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al Shammari B, Shiomi T, Tezera L, Bielecka MK, Workman V, Sathyamoorthy T, et al. The extracellular matrix regulates granuloma necrosis in tuberculosis. J Infect Dis. 2015;212:463–73. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li H, Schulte JJ. Tuberculosis. [Last accessed on 2023 May 30]. PathologyOutlines.com. website. Available from: https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/imgau/lungnontumorTBMicroLi2.jpg .

- 19.Momodu II, Savaliya V. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Osteomyelitis. Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532250/ . [Last accessed on 2023 Jan 16] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salvado F, Nobre MA, Gomes J, Maia P. Necrotizing sialometaplasia and bulimia: A case report. Medicina (Kaunas) 2020;56:188. doi: 10.3390/medicina56040188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ko YC, Philipone E, Florin W, Heinz MJ, Rosenberg S, Yudell R. Subacute necrotizing sialadenitis: A series of three cases and literature review. Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:425–8. doi: 10.1007/s12105-016-0714-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zainab H, Sultana A, Jahagirdar P. Denovo high grade salivary duct carcinoma: A case report and review of literature. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11:ZD10–2. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/29195.10210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramna TR, Mathew J, Wasim PKM, Namboodiripad APC, Mukunda A, Mohan A. Salivary duct carcinoma of parotid gland. Oral Maxillofac Pathol J. 2016;7:752–4. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sree Lakshmi I, Kumari BS, Jyothi C, Devojee M, Padma Malini K, Sunethri P, et al. Histopathological study of mucormycosis in post COVID-19 patients and factors affecting it in a tertiary care hospital. Int J Surg Pathol. 2023;31:56–63. doi: 10.1177/10668969221099626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rai S, Misra D, Misra A, Jain A, Jain P, Dhawan A. Palatal mucormycosis masquerading as bacterial and fungal osteomyelitis: A rare case report. Contemp Clin Dent. 2018;9:309–13. doi: 10.4103/ccd.ccd_743_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hafsi W, Badri T. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Erythema Multiforme. Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470259/ . [Last accessed on 2023 Mar 16] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mounica IL, Tejaswi K, Chennaiah T, Thanmai JV. Erythema multiforme: Integrating the superfluous diagnosis to a veracious conclusion (case report) Pan Afr Med J. 2020;37:129. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2020.37.129.25295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aghaloo TL, Dry SM, Mallya S, Tetradis S. Stage 0 osteonecrosis of the jaw in a patient on denosumab. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;72:702–16. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peral-Cagigal B, Redondo-González LM, Verrier-Hernández A. Invasive maxillary sinus aspergillosis: A case report successfully treated with voriconazole and surgical debridement. J Clin Exp Dent. 2014;6:e448–51. doi: 10.4317/jced.51571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buckingham SJ, Hansell DM. Aspergillus in the lung: Diverse and coincident forms. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:1786–800. doi: 10.1007/s00330-002-1813-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malek R, Gharibi A, Khlil N, Kissa J. Necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis. Contemp Clin Dent. 2017;8:496–500. doi: 10.4103/ccd.ccd_1181_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Listgarten MA. Electron microscopic observations on the bacterial flora of acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis. J periodontol (1930) 1965;36:328–39. doi: 10.1902/jop.1965.36.4.328. Doi: 10.1902/jop.1965.36.4.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schilder AM. Wegener's Granulomatosis vasculitis and granuloma. Autoimmun Rev. 2010;9:483–7. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dutta A, Arun P, Arun I. Adenoid cystic carcinoma with transformation to high grade carcinomatous and sarcomatoid components: A rare case report with review of literature. Head Neck Pathol. 2020;14:1094–104. doi: 10.1007/s12105-019-01120-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu B. Adenoid cystic carcinoma. PathologyOutlines.com. website. Available from: https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/imgau/salivaryglandsadenoidcysticXu05new.jpg . [Last accessed on 2023 May 30]

- 36.Singaraju M, Singaraju S, Patel S, Sharma S. Adenoid cystic carcinoma: A case report and review of literature. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2022;26(Suppl 1):S26–9. doi: 10.4103/jomfp.jomfp_458_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Caruntu A, Moraru L, Lupu M, Ciubotaru DA, Dumitrescu M, Eftimie L, et al. Assessment of histological features in squamous cell carcinoma involving head and neck skin and mucosa. J Clin Med. 2021;10:2343. doi: 10.3390/jcm10112343. 10.3390/jcm10112343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brandwein M, Said-Al-Naief N, Gordon R, Urken M. Clear cell odontogenic carcinoma: Report of a case and analysis of the literature. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128:1089–95. doi: 10.1001/archotol.128.9.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nance MA, Seethala RR, Wang Y, Chiosea SI, Myers EN, Johnson JT, et al. Treatment and survival outcomes based on histologic grading in patients with head and neck mucoepidermoid carcinoma. Cancer. 2008;113:2082–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khalesi S. A review of carcinoma ex-pleomorphic adenoma of the salivary glands. Int J Pathol Clin Res. 2016;2:043. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Som PM, Brandwein-Gensler. MS Anatomy and pathology of the salivary gland. In: Som PM, Curtin HD, editors. Text book of Head and Neck Imaging. 5th ed. Vol. 2. St Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2011. pp. 2525–35. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Swinson DE, Jones JL, Richardson D, Cox G, Edwards JG, O'Byrne KJ. Tumour necrosis is an independent prognostic marker in non-small cell lung cancer: Correlation with biological variables. Lung Cancer. 2002;37:235–40. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(02)00172-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goncalves CS, Lourencco T, Xavier-Magalhaaes A, Pojo M, Costa BM. Terry Lichtor., editor. Mechanisms of aggressiveness in glioblastoma: Prognostic and potential therapeutic insights. Evolution of the Molecular Biology of Brain Tumors and the Therapeutic Implications. InTech. 2013:387–431. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ling YH, Chen JW, Wen SH, Huang CY, Li P, Lu LH, et al. Tumor necrosis as a poor prognostic predictor on postoperative survival of patients with solitary small hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2020;20:607. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-07097-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yi M, Xia L, Zhou Y, Wu X, Zhuang W, Chen Y, et al. Prognostic value of tumor necrosis in gastrointestinal stromal tumor: A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019;98:e15338. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000015338. 10.1097/MD.0000000000015338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rosen LE, Karrison T, Ananthanarayanan V, Gallan AJ, Adusumilli PS, Alchami FS, et al. Nuclear grade and necrosis predict prognosis in malignant epithelioid pleural mesothelioma: A multi-institutional study. Mod Pathol. 2018;31:598–606. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2017.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Casaroto AR, Toledo GL, Filho JL, Soares CT, Capelari MM, Lara VS. Ameloblastic carcinoma, primary type: Case report, immunohistochemical analysis and literature review. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:1515–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Magliocca K, Martinez A. Ameloblastic carcinoma. PathologyOutlines.com. website. Available from: https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/imgau/mandiblemaxillawhoMagliocca1b.jpg . [Last accessed on 2023 May 30]

- 49.Jetley S, Jairajpuri ZS, Rana S, Walvir NM, Khetrapal S, Khan S, et al. Tumor histopathological response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in bone sarcomas: A single-institutional experience. Int J Health Allied Sci. 2020;9:240–5. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Song MK, Chung JS, Yhim HY, Lim SN, Kim SJ, Han YH, et al. Tumor necrosis and complete resection has significant impacts on survival in patients with limited-stage upper aerodigestive tract NK/T cell lymphoma. Oncotarget. 2017;8:79337–46. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.18107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zimmerman D, Dang NH. Stevens–Johnson Syndrome (SJS) and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (TEN): Immunologic Reactions. Oncologic Critical Care. 2019:267–80. [Google Scholar]