Harmful and helpful roles of astrocytes in spinal cord injury (SCI): SCI induce gradable sensory, motor and autonomic impairments that correlate with the lesion severity and the rostro-caudal location of the injury site. The absence of spontaneous axonal regeneration after injury results from neuron-intrinsic and neuron-extrinsic parameters. Indeed, not only adult neurons display limited capability to regrow axons but also the injury environment contains inhibitors to axonal regeneration and a lack of growth-promoting factors. Amongst other cell populations that respond to the lesion, reactive astrocytes were first considered as only detrimental to spontaneous axonal regeneration. Indeed, astrocytes, that form the outer layer of the glial scar, play a predominant mechanical role as a barrier to axonal regeneration. However, evidence also attests to the beneficial functions of astrocytes after SCI. For instance, the glial scar barrier also limits the spread of inflammation and the extension of the lesion. Following SCI, astrocytes undertake significant molecular changes. We have earlier identified in mice that approximately 10% of resident mature astrocytes located in the vicinity of the lesion site naturally transdifferentiate into a neuronal phenotype (Noristani et al., 2016). Besides, SCI-induced converted astrocytes display an augmented expression of a neural stem cell marker, fibroblast growth factor receptor 4 (Fgfr4) (Noristani et al., 2016). FGFR (including FGFR4) is crucial during neuronal differentiation and FGF4, a ligand of FGFR4, is essential for astrocyte dedifferentiation into neural stem cells. Thus we recently, investigated whether increasing SCI-induced Fgfr4-upregulation within astrocytes may improve recovery and tissue preservation (Bringuier et al., 2023). We first showed an increased βIII-tubulin expression in astrocytes resulting from lentiviral-mediated astrocytic Fgfr4 over-expression. RNAseq analysis of converted astrocytes (astrocytes expressing βIII-tubulin) revealed a concomitant upregulation of neurogenic pathways and downregulation of Notch signaling. Both mechanisms are consistent with astrocyte-to-neuron conversion. Second, using open field and CatWalk® behavioral analysis, we highlighted that the enhancement of Fgfr4 specifically in astrocytes just after a lateral hemisection of the spinal cord improves motor recovery in mice. Interestingly, we observed that Fgfr4 over-expression-induced improvements are sex-dependent for fine motricity. We also observed a better gross motor function recovery in females as compared to males. This sexually dimorphic response correlates with a decrease in lesion volume in females conversely to males. We then concentrated our histological investigations on females only and we show that caudal to the lesion, Fgfr4 over-expression preserves myelin and reduces glial reactivity (Bringuier et al., 2023).

In vivo reprogramming of astrocytes in physiological and pathological circumstances: Astrocyte conversion into neurons may compensate for neuronal death and/or limit tissue structure alteration. Both mechanisms may participate in the repair of impaired functions in pathological conditions (see review in Janowska et al., 2019). In vivo enforced differentiation of embryonic stem cells or reprogramming of glial cells into neurons using transcription factors and morphogens was achieved in several physiological and pathological contexts. However, glial cells conversely to embryonic stem cells, do not require several stages of differentiation since glia and neurons derive from common progenitors (reviewed in Janowska et al., 2019). It had been thus emphasized that targeting glia for cell conversion instead of stem cells may limit tumorigenesis risk (Janowska et al., 2019). In vivo reprogramming of glial cells into neurons had been investigated for almost 20 years. After a T8 lateral spinal cord hemisection in adult mice, astrocyte conversion into doublecortin-positive cells was induced by enforced lentiviral-mediated Sox2 astrocytic expression. Approximately 5% of resident astrocytes converted to DCX+/βIII-tubulin+ neuroblasts further gives rise to mature neurons (Su et al., 2014). In a recent follow-up investigation using cervical dorsal hemisection of the spinal cord, enforced Sox2 expression in NG2 cells induced conversion into neuroblasts and eventually into neurons (Tai et al., 2021). Importantly, it also reduced glial scarring and promoted functional recovery (Tai et al., 2021). Therefore, in central nervous system injury, converting reactive astrocytes had been achieved through enforced expression of ectopic genes or fate-determining transcription factors that are not naturally expressed by astrocytes. Tumorigenesis risks had been associated with the delivery/induction of broad transcription factors (such as c-myc, Klf4, or OCT3/4) involved in cell reprogramming that may represent oncogenic factors (reviewed in Janowska et al., 2019). Consequently, targeting a gene, that is endogenously over-expressed by SCI, such as Fgfr4, may decrease the risk of tumorigenesis and/or induction of detrimental cell conversion as compared to transcription factors. Indeed, transcription factors may induce less specific effects due to their broader role. Interestingly, the conversion of astrocytes in other cell types than neurons also led to beneficial effects. In a mouse model of demyelination, astrocytes had been converted into oligodendroglia using miR-302/367. miR-302/367 is involved in many biological processes including cell proliferation, cell differentiation and reprogramming and maintenance of pluripotency in embryonic stem cells and induced pluripotent stem cells. This resulted in an enhancement of remyelination and functional recovery (Ghasemi-Kasman et al., 2018). Likewise, continuous intrathecal delivery of the epidermal growth factor Neuregulin-1 converted reactive astrocytes into oligodendrocyte lineage cells, promoted remyelination, and improved motor function recovery in a rat model of SCI (Ding et al., 2021).

The transcription factor DLX2 had been recently shown to induce the differentiation of astrocytes into induced neural progenitor cells that further differentiate into multilineage cells in the adult rodent brain (Zhang et al., 2022). First, the authors demonstrated that DLX2 induces neurogenesis from resident astrocytes. Indeed, 2 and 3 weeks after astrocytic lentiviral mediated expression of DLX2, a large number of cells expressed the induced neural progenitor cells marker ASCL1+ (achaete-scute family BHLH transcription factor 1). Four weeks after induction, ASCL1+-cells further became neuroblasts expressing doublecortin (DCX). Twelve weeks after injection, DCX+ cells eventually differentiated into GABAergic neurons. Second, astrocytes-derived induced neural progenitor cells gave rise to glial cells. Indeed, by 12 weeks after injection, half of DLX2-induced cells converted into astrocytes and oligodendrocytes. Studies remain to be done to understand the role of DLX2 in astrocyte reprogramming. However, it seems that DLX2 resembles the regulation of key genes during adult neurogenesis more than embryonic neurogenesis (Zhang et al., 2022). Along this line, the DLX2 homeobox genes had been reported as participating in the regulation of GABAergic neuron phenotype. Therefore, DLX2 enhancement in the context of central nervous system injury, in particular SCI, is an attractive strategy to elicit the reprogramming of astrocytes not only into neurons but also into oligodendrocytes that may promote remyelination at a later stage after injury. Additionally, the suppression of Notch signaling seems to be mandatory for DLX2-induced reprogramming into neurons (Zhang et al., 2022). This is consistent with previous findings, including ours (Bringuier et al., 2023), demonstrating that a down-regulation of Notch is necessary for neuronal differentiation. Besides, the time window of reprogramming is an important parameter. Astrocytes have been acknowledged for their beneficial role at an early stage after injury and it had then been already suggested that converting astrocytes into neurons (Janowska et al., 2019) or oligodendrocytes at a later stage after injury represents an attractive strategy. It would indeed preserve and prolonged astrocytic early beneficial role after injury. Moreover, the highly inflammatory environment observed early after injury may be not optimal to convert astrocytes-to-neurons conversely to a later time window. Based on our work, Fgfr4 over-expression at subacute or even chronic stages may be a good strategy since we observed an SCI-induced upregulation of Fgfr4 mRNA up to 2 weeks and of FGFR4 protein expression up to 6 weeks after lesion (the latest time points investigated) (Noristani et al., 2016).

Sex influence on astrocytic response after injury: Several studies have identified sexual dimorphisms in astrocytes both in physiological and pathological conditions. However, only very few studies concentrated on sex difference in the astrocytic response to an injury. Following traumatic brain injury either an increased astrogliosis was reported in males only (Villapol et al., 2017) or an increased astrocytic reactivity associated with a lower hypertrophy was observed in females as compared to males (Jullienne et al., 2018). After traumatic brain injury, the proportion of astrocytes expressing the C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 was higher in males (Acaz-Fonseca et al., 2015). Interestingly, we observed a sex-dependent response to the overexpression of the astrocytic expression of Fgfr4 after SCI. Only females displayed an improvement in gross motor function and fine motricity recovery was sex-dependent (Bringuier et al., 2023). This may either reflect a global sex-dependent response to SCI or an intrinsic difference in the astrocytic response. Consistent with the latest hypothesis, a sexual dimorphism had been observed in the nucleus tractus solitarius of the brain stem with a higher expression of FGFR2 and FGFR4 in females than in males (Chen et al., 2020).

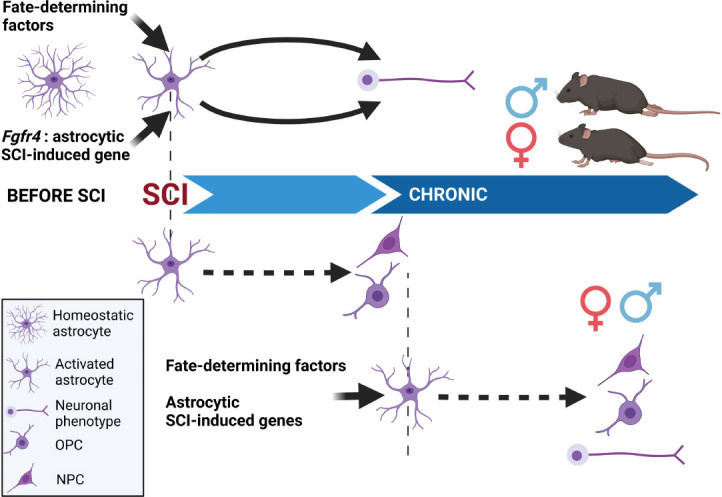

In vivo cytotherapy through astrocyte reprogramming into different cell types including neurons and oligodendrocytes has been achieved via the modulation of small molecules, genes, transcription factors, and microRNAs (Figure 1). In SCI and other disorders, challenging studies remain to be done to understand the mechanisms of endogenous and induced astrocyte reprogramming. Also, the identification of optimal time windows, which may vary on the type of converted cell, may permit to develop longitudinal therapeutic strategies. Finally, physiological and pathological environments are governed by a sexual dimorphism this is thus essential to investigate possible sex-dependent responses to astrocyte modulation.

Figure 1.

In vivo reprogramming of astrocytes after spinal cord injury: present and perspectives.

Following SCI, reprogramming astrocytes to neurons had been achieved using fate-determining factors that were either not naturally induced (or even expressed) by astrocytes or naturally induced by the injury. Interestingly, the functional response to Fgfr4-induced astrocyte reprogramming displayed a sexual dimorphism with a better-improved motor recovery observed in females. For future experiments, it is thus mandatory to investigate outcomes in both sexes. It may also be of interest to convert astrocytes in neurons but also oligodendrocytes, either using a single inducer or a cocktail of inducers. Knowing the highly inflammatory environment early after injury, inducing an astrocytic conversion at a later stage after injury may also be of interest. Created with BioRender.com. Fgfr4: Fibroblast growth factor receptor 4; NPC: neural progenitor cell; OPC: oligodendrocyte precursor cell; SCI: spinal cord injury.

This work was supported by the patient organizations “Verticale” (to YNG and FEP).

Additional file: Open peer review reports 1 (90.8KB, pdf) and 2 (90.3KB, pdf) .

Footnotes

Open peer reviewers: Giacomo Masserdotti, Ludwig-Maximilians University, Germany; Feng-Quan Zhou, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, USA.

P-Reviewers: Masserdotti G, Zhou FQ; C-Editors: Zhao M, Liu WJ, Qiu Y; T-Editor: Jia Y

References

- 1.Acaz-Fonseca E, Duran JC, Carrero P, Garcia-Segura LM, Arevalo MA. Sex differences in glia reactivity after cortical brain injury. Glia. 2015;63:1966–1981. doi: 10.1002/glia.22867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bringuier CM, Noristani HN, Perez JC, Cardoso M, Goze-Bac C, Gerber YN, Perrin FE. Up-regulation of astrocytic Fgfr4 expression in adult mice after spinal cord injury. Cells. 2023;12:528. doi: 10.3390/cells12040528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen P, Xu B, Feng Y, Li KX, Liu Z, Sun X, Lu XL, Wang LQ, Chen YW, Fan XX, Yang XL, Wang N, Qiao GF, Li BY. FGF-21 ameliorates essential hypertension of SHR via baroreflex afferent function. Brain Res Bull. 2020;154:9–20. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2019.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ding Z, Dai C, Zhong L, Liu R, Gao W, Zhang H, Yin Z. Neuregulin-1 converts reactive astrocytes toward oligodendrocyte lineage cells via upregulating the PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway to repair spinal cord injury. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021;134:111168. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.111168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghasemi-Kasman M, Zare L, Baharvand H, Javan M. In vivo conversion of astrocytes to myelinating cells by miR-302/367 and valproate to enhance myelin repair. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2018;12:e462–472. doi: 10.1002/term.2276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Janowska J, Gargas J, Ziemka-Nalecz M, Zalewska T, Buzanska L, Sypecka J. Directed glial differentiation and transdifferentiation for neural tissue regeneration. Exp Neurol. 2019;319:112813. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2018.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jullienne A, Salehi A, Affeldt B, Baghchechi M, Haddad E, Avitua A, Walsworth M, Enjalric I, Hamer M, Bhakta S, Tang J, Zhang JH, Pearce WJ, Obenaus A. Male and female mice exhibit divergent responses of the cortical vasculature to traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2018;35:1646–1658. doi: 10.1089/neu.2017.5547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noristani HN, Sabourin JC, Boukhaddaoui H, Chan-Seng E, Gerber YN, Perrin FE. Spinal cord injury induces astroglial conversion towards neuronal lineage. Mol Neurodegener. 2016;11:68. doi: 10.1186/s13024-016-0133-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Su Z, Niu W, Liu ML, Zou Y, Zhang CL. In vivo conversion of astrocytes to neurons in the injured adult spinal cord. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3338. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tai W, Wu W, Wang LL, Ni H, Chen C, Yang J, Zang T, Zou Y, Xu XM, Zhang CL. In vivo reprogramming of NG2 glia enables adult neurogenesis and functional recovery following spinal cord injury. Cell Stem Cell. 2021;28:923–937. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2021.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Villapol S, Loane DJ, Burns MP. Sexual dimorphism in the inflammatory response to traumatic brain injury. Glia. 2017;65:1423–1438. doi: 10.1002/glia.23171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang Y, Li B, Cananzi S, Han C, Wang LL, Zou Y, Fu YX, Hon GC, Zhang CL. A single factor elicits multilineage reprogramming of astrocytes in the adult mouse striatum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022;119:e2107339119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2107339119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.