Abstract

PURPOSE

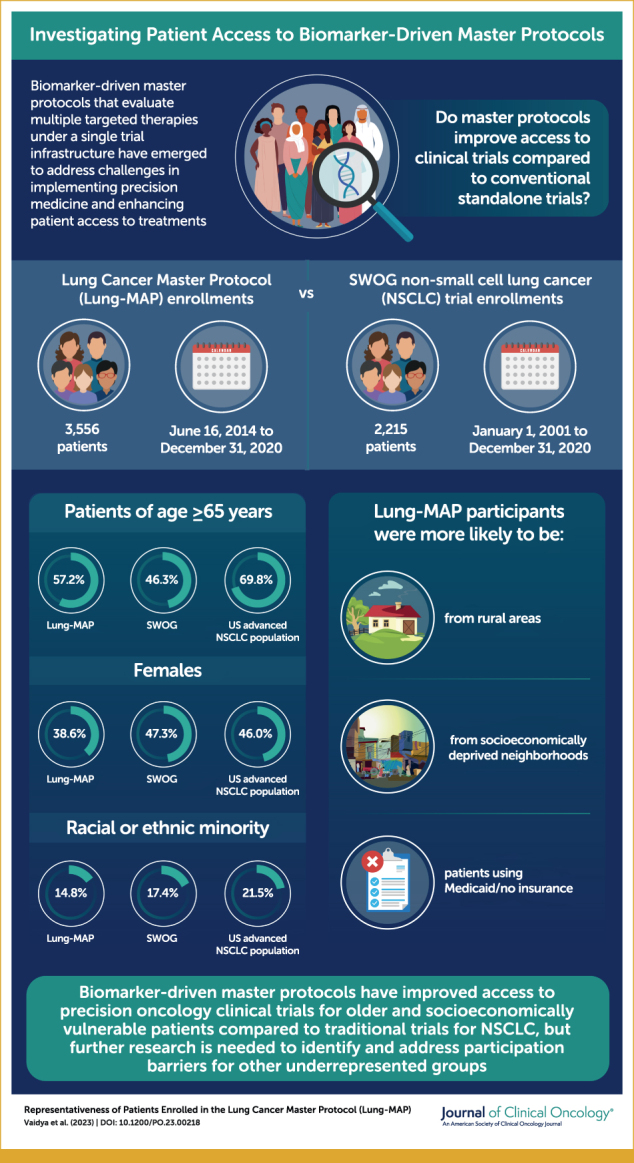

Lung Cancer Master Protocol (Lung-MAP), a public-private partnership, established infrastructure for conducting a biomarker-driven master protocol in molecularly targeted therapies. We compared characteristics of patients enrolled in Lung-MAP with those of patients in advanced non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) trials to examine if master protocols improve trial access.

METHODS

We examined patients enrolled in Lung-MAP (2014-2020) according to sociodemographic characteristics. Proportions for characteristics were compared with those for a set of advanced NSCLC trials (2001-2020) and the US advanced NSCLC population using SEER registry data (2014-2018). Characteristics of patients enrolled in Lung-MAP treatment substudies were examined in subgroup analysis. Two-sided tests of proportions at an alpha of .01 were used for all comparisons.

RESULTS

A total of 3,556 patients enrolled in Lung-MAP were compared with 2,215 patients enrolled in other NSCLC studies. Patients enrolled in Lung-MAP were more likely to be 65 years and older (57.2% v 46.3%; P < .0001), from rural areas (17.3% v 14.4%; P = .004), and from socioeconomically deprived neighborhoods (42.2% v 36.7%, P < .0001), but less likely to be female (38.6% v 47.2%; P < .0001), Asian (2.8% v 5.1%; P < .0001), or Hispanic (2.4% v 3.8%; P = .003). Among patients younger than 65 years, Lung-MAP enrolled more patients using Medicaid/no insurance (27.6% v 17.8%; P < .0001). Compared with the US advanced NSCLC population, Lung-MAP under represented patients 65 years and older (57.2% v 69.8%; P < .0001), females (38.6% v 46.0%; P < .0001), and racial or ethnic minorities (14.8% v 21.5%; P < .0001).

CONCLUSION

Master protocols may improve access to trials using novel therapeutics for older patients and socioeconomically vulnerable patients compared with conventional trials, but specific patient exclusion criteria influenced demographic composition. Further research examining participation barriers for under represented racial or ethnic minorities in precision medicine clinical trials is warranted.

Precision medicine master protocols conducted as a public-private partnership may improve trial access for patients.

INTRODUCTION

Progress in precision medicine has been accelerated by advancements in genome sequencing, creation of large, biologic databases, and development of computational methods to analyze these databases.1-3 The introduction of immunotherapy and targeted therapy drugs has improved patient outcomes2,4; in particular, development of therapies targeting specific tumor mutations in non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) has improved survival among patients whose tumors harbor these mutations.5 Yet, several barriers to implementing precision medicine at oncology clinics and improving patient access to these treatments remain.6,7 In addition, conducting clinical trials to evaluate new targeted therapies is challenging because of the need to screen large numbers of patients, selection and interpretation of biomarker tests, and patient- and practice-level financial concerns.8,9

CONTEXT

Key Objective

Biomarker-driven master protocols create a single clinical trial infrastructure to evaluate multiple molecularly targeted therapies, but it is unknown whether master protocols improve access to clinical trials. This study compared enrollment patterns for a master protocol (Lung Cancer Master Protocol [Lung-MAP]) conducted as a public-private partnership to conventionally conduct clinical trials for advanced non–small-cell lung cancer.

Knowledge Generated

Lung-MAP enrolled proportionally more older adults, patients from rural or socioeconomically deprived areas, and patients with Medicaid or no insurance compared with conventional, stand-alone clinical trials. However, female patients and patients of Asian race or Hispanic ethnicity were under represented.

Relevance

Master protocols may improve access to clinical trials in precision oncology for some patient groups that experience barriers to participating in clinical trials. Further examination and resolution of factors impeding access to novel therapeutics for under represented groups will improve generalizability of trial findings and access to novel therapies in clinical practice.

Biomarker-driven master protocols, which test multiple therapies matched to biomarkers under a single clinical trial infrastructure, were developed as a response to the challenges in conducting clinical trials of these new targeted therapies.10 One such master protocol, the Lung Cancer Master Protocol (Lung-MAP), was designed to evaluate novel targeted therapies for previously treated NSCLC. Lung-MAP is a part of the US National Cancer Institute's (NCI) precision medicine initiative and, to our knowledge, is the first protocol conducted within the NCI's adult National Clinical Trials Network (NCTN)11 as a public-private partnership. In addition to establishing infrastructure for clinical trials testing molecularly targeted therapies, Lung-MAP provides a framework for conducting master protocols to address unmet needs for therapeutics in other areas of oncology.9

Clinical trials provide evidence for the use of new treatments in clinical practice; therefore, proportionate representation of various patient groups is critical for the generalizability of trial findings. Patients belonging to racial or ethnic minorities have been found to be substantially under represented in pharmaceutical company–sponsored oncology drug trials12,13 and, to a lesser degree, in trials conducted within the NCTN.13,14 To our knowledge, there are no published data on whether master protocols using a public-private partnership approach improve access to clinical trials over conventional, stand-alone trials. Therefore, our goal was to compare patients enrolled in Lung-MAP with those enrolled in adult NCTN trials for advanced NSCLC by sociodemographic characteristics. We also examined whether Lung-MAP participants were representative of the US advanced NSCLC population.

METHODS

We examined accrual data for the Lung-MAP screening protocols—S1400 (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02154490) and LUNGMAP (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03851445). Details of the Lung-MAP screening protocol have been published previously.9,15 S1400 enrolled patients with squamous cell cancer (SCC) from June 2014 to January 2019, whereas LUNG-MAP opened in February 2019 and included all histologic types of NSCLC. We also examined accrual data for 10 phase II or III clinical trials for advanced NSCLC conducted by the SWOG Cancer Research Network. Lung-MAP enrollments were examined from June 16, 2014 to December 31, 2020, whereas SWOG NSCLC enrollments were examined over a 20-year period (January 1, 2001-December 31, 2020). The longer period was chosen for SWOG NSCLC trials to allow an adequate sample size for comparison with Lung-MAP. All trials included in this analysis were previously approved by an institutional review board (IRB) or by the NCI's central IRB. Written informed consent was obtained for all enrolled patients.

Accrual patterns were compared by sociodemographic characteristics and study site type between Lung-MAP and SWOG NSCLC trials. Patient-level demographic data from trial registration forms included age (18-64 v 65 years and older), sex (male v female), and patient-reported race (White, Black, Asian/Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaska Native) and ethnicity (Hispanic v not Hispanic). In addition, we defined a variable any minority race/ethnicity for patients who reported non-White race or Hispanic ethnicity. For both Lung-MAP and NSCLC trials, we examined baseline smoking status and tumor histology (SCC v non-SCC) by sex. We compared enrollments between the two groups by rurality (rural v urban). Rural residence was defined by matching patient residential zip codes with the 2013 Rural-Urban Continuum Codes published by the Economic Research Service of the US Department of Agriculture. Enrollments were also compared by the type of study site (academic v community). To compare enrollment by neighborhood socioeconomic deprivation, we linked patient zip code to the Area Deprivation Index (ADI; University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, 2019; 2013 version). The ADI score (range, 0-100) is a comprehensive measure composed of multiple indicators of neighborhood disadvantage in the domains of poverty, education, employment, and housing quality.16 We constructed quintiles of the ADI score on the basis of the national distribution of scores with the highest quintile (81-100), indicating the most deprived neighborhoods. ADI quintiles 4 and 5 were defined as neighborhoods with high socioeconomic deprivation. For patients younger than 65 years, we compared accrual patterns between Lung-MAP and other NSCLC trials by health insurance (Medicaid or no insurance v private insurance). This analysis excluded patients 65 years and older because of their uniform access to Medicare.

We compared demographics of Lung-MAP participants with those of the US advanced NSCLC population. To calculate demographic proportions in the US NSCLC population, we used data from the NCI's SEER program and the US Census data. We used the SEER Research Plus 18 Registries (SEER18) November 2020 Submission (2000-2018) in SEER*Stat17 (National Cancer Institute, version 8.4) to identify NSCLC cases diagnosed from 2014 to 2018 among individuals 18 years and older. Site, stage, and histology codes were used to identify incidence of advanced NSCLC. Specifically, lung and bronchus tumors with malignant behavior and distant stage were selected and NSCLC cases were identified on the basis of International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, third edition histologic codes published elsewhere.18 Incidence rates were calculated by age, sex, race, and ethnicity and adjusted to the US population (Vintage 2019 population data provided by the US Census Bureau through SEER*Stat) using a previously developed method.14 This adjustment allows SEER-based demographic proportions to better reflect the US population in terms of age, sex, race, and ethnicity.

To assess disparities in treatment access, we examined the subset of patients enrolled in the Lung-MAP screening protocol who enrolled in one of 15 Lung-MAP treatment substudies and compared them with patients enrolled in SWOG NSCLC trials and with the US NSCLC population. Lung-MAP's investigational component consists of independently conducted treatment substudies for biomarker-driven treatments and a nonmatch study for otherwise eligible patients not meeting the criteria for a biomarker-driven study.9

Finally, we conducted a sensitivity analysis comparing Lung-MAP participants with patients enrolled in SWOG advanced NSCLC trials between January 1, 2014 and December 31, 2020 to examine whether our primary findings were influenced by temporal confounding.

Statistical Analysis

To compare enrollment proportions by demographic and other characteristics between Lung-MAP and SWOG NSCLC trials, we used chi-squared tests. For comparisons between Lung-MAP and the US NSCLC population, the rates estimated for the US population were considered fixed and one-sample binomial tests were used for comparison. Two-tailed P values ≤.01 were considered statistically significant. Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) between August 2021 and May 2022.

RESULTS

Demographics

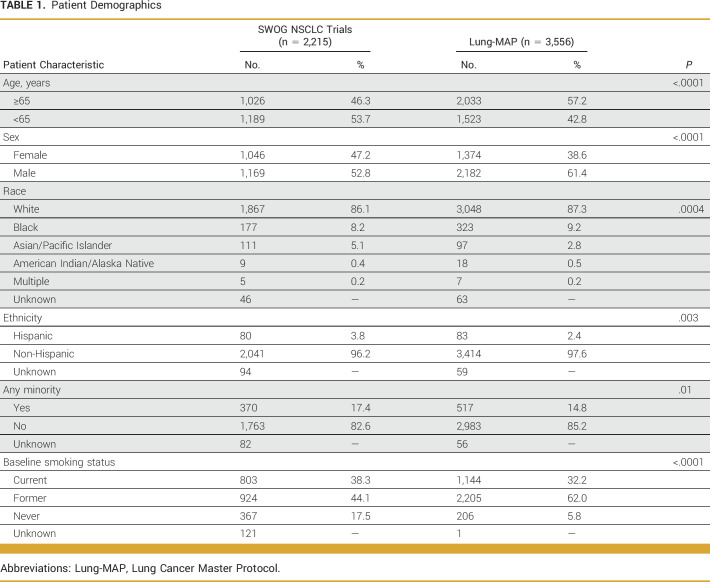

The primary analysis included 3,556 patients enrolled in the Lung-MAP screening protocol (S1400, LUNGMAP) and 2,215 patients enrolled in SWOG clinical trials for advanced NSCLC (Table 1, Appendix Table A1). Proportionally, more patients in Lung-MAP were 65 years and older compared with those in SWOG NSCLC trials (57.2% v 46.3%; P < .0001), but proportionally fewer patients were female (38.6% v 47.3%; P < .0001). A smaller proportion of patients of Asian/Pacific Islander race (2.8% v 5.1%; P < .0001) enrolled in Lung-MAP compared with other trials, but the proportions of Black (9.3% v 8.2%; P = .16) and American Indian/Alaska Native (0.5% v 0.4%; P = .59) patients were not different between Lung-MAP and SWOG NSCLC trials. Lung-MAP enrolled proportionally fewer patients of Hispanic ethnicity (2.4% v 3.8%; P = .003). Overall, the proportion of patients belonging to any racial or ethnic minority group differed between Lung-MAP and SWOG trials (14.8% v 17.4%; P = .01). Results from the comparison of Lung-MAP with SWOG NSCLC trial enrollments between 2014 and 2020 were similar (Appendix Table A2).

TABLE 1.

Patient Demographics

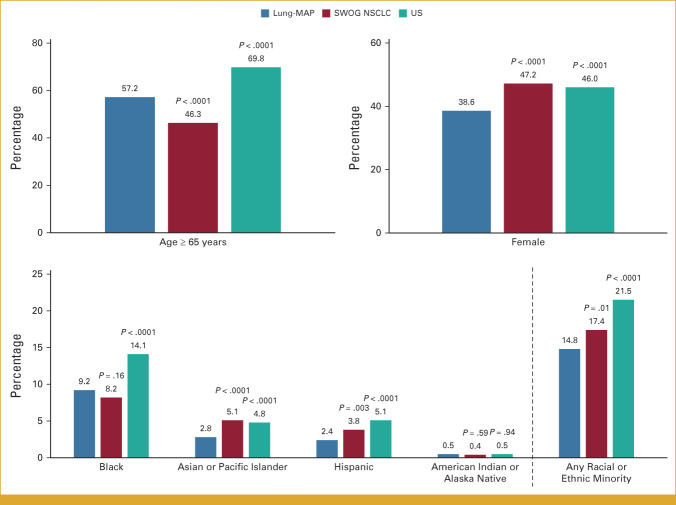

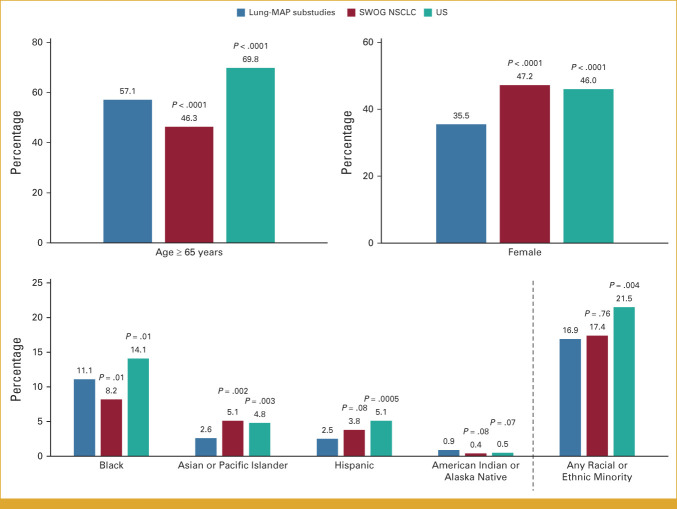

Patients 65 years and older account for almost 70% of the US advanced NSCLC population, higher than the corresponding proportion for Lung-MAP (57.2%; P < .0001; Fig 1). Female patients were under represented in Lung-MAP (38.6% v 46.0%; P < .0001), as were patients belonging to any racial or ethnic minority (14.8% v 21.5%; P < .0001). While enrollment of patients of American Indian/Alaska Native race matched the expected population proportion (0.5% v 0.5%; P = .94), patients of Black or Asian/Pacific Islander race or of Hispanic ethnicity were under represented (Fig 1).

FIG 1.

Comparison of demographics between Lung-MAP, SWOG NSCLC trials, and US NSCLC population. The bars show percentage of patients in each demographic subgroup. P values are shown for the comparison between Lung-MAP and SWOG NSCLC trials and Lung-MAP and US NSCLC population. Lung-MAP, Lung Cancer Master Protocol; NSCLC, non–small-cell lung cancer.

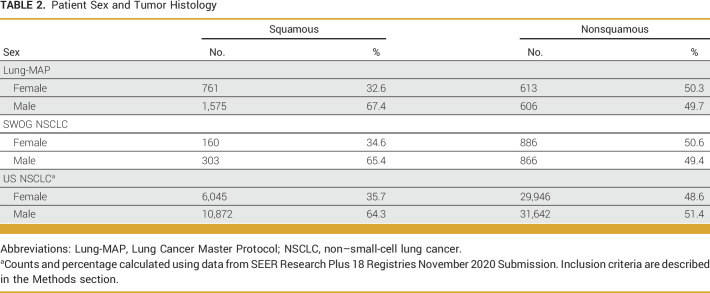

Smoking status differed between Lung-MAP and other NSCLC trials (P < .0001) with proportionally fewer Lung-MAP participants being never smokers (5.8% v 17.5%; Table 1). Among patients enrolled in Lung-MAP, 65.7% (n = 2,336) had SCC (Table 2). Female patients accounted for 32.6% (n = 761) of patients with SCC and 50.3% of patients with non-SCC (613 of 1,219). Among patients enrolled in SWOG NSCLC trials, 20.9% (n = 463) had SCC, of whom 34.6% were female (n = 160; Table 2). Finally, 21.6% of US NSCLC patients from SEER18 had SCC, of whom 35.7% were female (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Patient Sex and Tumor Histology

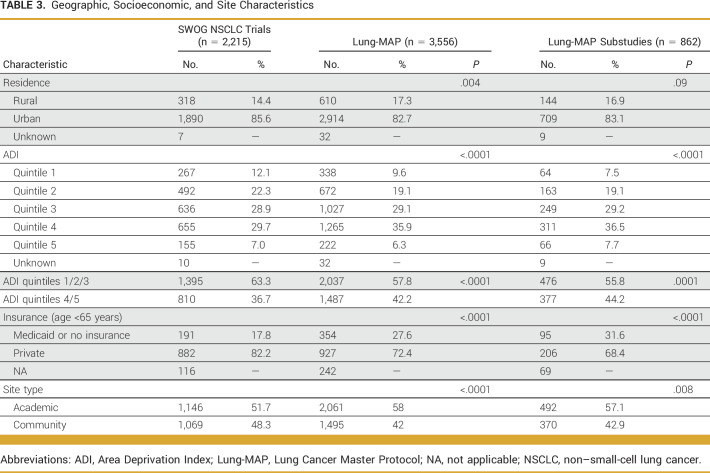

Socioeconomic and Site Characteristics

The majority of patients enrolled in Lung-MAP lived in urban areas, with 17.3% (n = 610) of patients in Lung-MAP living in rural areas. In comparison, 14.4% of patients in other NSCLC trials lived in rural areas (P = .004; Table 3). Over 40% of Lung-MAP participants lived in neighborhoods with highest socioeconomic deprivation (ADI quintiles 4 and 5) compared with other NSCLC trials (42.2% v 36.7%; P < .0001; Table 3). In the subset of patients younger than 65 years and with known insurance status, 27.6% (354 of 1,281) of Lung-MAP enrollees reported having Medicaid or no insurance, whereas the corresponding proportion was 17.8% (191 of 1,073) for other NSCLC trials (P < .0001; Table 3). Lung-MAP included proportionally more patients enrolled at academic sites compared with other NSCLC trials (58% v 51.7%; P < .0001). Results were similar when comparing enrollments between 2014 and 2020, but the findings for rural residence and insurance were no longer statistically significant (Appendix Table A2).

TABLE 3.

Geographic, Socioeconomic, and Site Characteristics

Lung-MAP Substudies

Results of the analysis comparing patients enrolled in Lung-MAP substudies with NSCLC trials and the US advanced NSCLC population were similar to results for the primary screening Lung-MAP protocol comparison (Fig 2). Patients enrolled in Lung-MAP substudies were more likely to be 65 years and older (P < .0001) and less likely to be female (P < .0001) or of Asian race (P = .002; Fig 2) compared with patients in other NSCLC trials. Patients enrolled in substudies included a larger proportion of patients reporting Black (11.1%) or American Indian/Alaska Native race (0.9%) relative to other NSCLC trials (8.2% and 0.4%, respectively), but the differences were statistically significant only for Black patients (P = .01). Consistent with the Lung-MAP screening protocol, Lung-MAP substudies enrolled proportionally more patients from neighborhoods with highest socioeconomic deprivation compared with other NSCLC trials (44.2% v 36.7%; P = .0001; Table 3) and a higher proportion of patients with Medicaid or no insurance among patients younger than 65 years (31.6% v 17.8%; P < .0001; Table 3).

FIG 2.

Comparison of demographics between Lung-MAP substudies, SWOG NSCLC trials, and the US NSCLC population. The bars show percentage of patients in each demographic subgroup. P values are shown for the comparison between Lung-MAP substudies and SWOG NSCLC trials and Lung-MAP and the US NSCLC population. Lung-MAP, Lung Cancer Master Protocol; NSCLC, non–small-cell lung cancer.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that a biomarker-driven master protocol for NSCLC improved access to novel therapeutics for older patients, rural patients, those with Medicaid/no insurance, and patients from socioeconomically deprived areas compared with conventional advanced NSCLC trials. Consistent with the existing literature on clinical trial participation,12,14,19 our comparison of Lung-MAP with the US advanced NSCLC population showed that females, older adults, and patients belonging to racial or ethnic minority groups were under represented in Lung-MAP.

Pre-2019 enrollment in Lung-MAP was restricted to patients with SCC, which occurs more frequently in males.20,21 This pattern was also observed among patients enrolled in Lung-MAP, with male patients accounting for two thirds of Lung-MAP participants with SCC. Moreover, a majority of Lung-MAP participants included in this analysis had SCC explaining the under representation of females in Lung-MAP compared with other NSCLC trials and with the US advanced NSCLC population. This is also consistent with our findings for other NSCLC trials, which enrolled proportionally more female patients, and most patients had non-SCC.

The under representation of patients of any racial or ethnic minority in Lung-MAP relative to the US advanced NSCLC populations echoes other findings on participation of minority populations in clinical trials.12,14,19 This under-representation can be attributed to lower enrollment of patients who were Asian/Pacific Islander or Hispanic. Both groups of patients have been found to have a high frequency of oncogenic driver mutations, particularly epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation.22,23 Asian and Hispanic patients were also found to be more likely to get EGFR testing.24,25 The eligibility criteria for Lung-MAP excluded patients harboring known EGFR and anaplastic lymphoma kinase fusion mutations,15 which might have contributed to the under representation of these patient groups. In addition, under representation of Hispanic patients might have also been influenced by concerns related to the financial burden of treatment, limited English proficiency, and lower health literacy.26,27 Further investigation of these factors may help improve representation of Hispanic patients in Lung-MAP and other precision medicine trials. We found that Black patients participated in the Lung-MAP screening protocol at rates similar to those for SWOG-led NSCLC trials. The proportion of Black patients who enrolled in a Lung-MAP treatment substudy was statistically significantly higher than enrollment of Black patients in SWOG NSCLC trials, but Black patients were still under represented relative to the US advanced NSCLC population. These findings emphasize the importance of offering an available trial to eligible patients, as such patients, regardless of their racial or ethnic background, agree to participate more than half the time.28

Diversity of clinical trial enrollment is critical because treatment efficacy and adverse events may vary across patient subgroups. It has been shown that pharmaceutical company–sponsored trials inadequately represent Black patients across several cancer types.13 In multiple industry-sponsored, global clinical trials of second-line immunotherapy for patients with advanced NSCLC, Black patients accounted for 2%-3% of enrolled patients,29-32 well below the proportion of Black patients enrolled in Lung-MAP. Of these studies, three reported the proportion of enrolled patients 65 years and older, which ranged from 41% to 47%29,30,32 and was proportionally lower than the enrollment of older adults in Lung-MAP. Thus, the public-private partnership approach to the evaluation of novel therapies may provide an opportunity to increase enrollment of under represented patient groups in trials and improve generalizability of trial findings.

Health insurance is a key determinant of the type of diagnostic screenings and therapies that patients with cancer may access. Several studies have shown that patients with NSCLC using Medicaid insurance25,33 or with Medicare-Medicaid dual eligibility34 have lower rates of biomarker testing compared with patients with private insurance or Medicare. Using data for patients with stage IV NSCLC from the California Cancer Registry, Maguire and colleagues demonstrated that patients with Medicaid or other non-Medicare public insurance were less likely to receive any systematic treatment, bevacizumab combinations, or tyrosine kinase inhibitors.35 Larson et al36 showed that patients with invasive NSCLC were less likely to receive treatment with erlotinib if they used Medicaid insurance. We found that Lung-MAP expanded access to biomarker testing and targeted therapies compared with other NSCLC trials, thereby helping address income and insurance-related disparities in precision medicine trials for NSCLC.

Residents of rural areas face multiple obstacles to receiving adequate medical care, including reduced access to providers, socioeconomic disadvantages, and lack of health insurance, placing them at a higher risk of poor health outcomes.37,38 Rural patients with NSCLC are less likely to receive biomarker testing36 and systemic therapy.39 Similar findings have been published for patients with NSCLC living in areas of higher poverty (or lower neighborhood socioeconomic status).34-36,40 The majority of patients included in our analysis were from urban areas and from areas of lower deprivation. However, we found that Lung-MAP improved access for patients from rural areas and from the most deprived neighborhoods over conventional NSCLC trials. The availability of Lung-MAP at a large number of sites, extensive outreach to site staff and patients, and allowing flexibility in screening and patient evaluation for trial eligibility9 are likely to be important factors for improving enrollment of patients with lower access to care.

While most patients receive cancer treatment at community hospitals,8 the majority of Lung-MAP participants are enrolled at academic sites, proportionally more than for SWOG NSCLC trials. This is consistent with the barriers to precision oncology implementation at community sites, including challenges related to biospecimen collection, test selection, and delays in receiving test results at the clinic level.6,7 In addition to flexibility in trial design, additional resources to resolve site-level barriers are required to improve access to precision oncology trials at community sites.

Our study has limitations. First, our comparison group of patients enrolled in SWOG NSCLC trials was from a longer time horizon, which might have resulted in temporal confounding, especially for comparisons of socioeconomic variables. For example, the opening of Lung-MAP coincided with the expansion of Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), which has been shown to have a nearly threefold increase in the proportion of patients using Medicaid in oncology clinical trials conducted by SWOG.41 Thus, national policy changes might have resulted in the increased proportion of patients with Medicaid enrolled in Lung-MAP compared with other NSCLC trials in our sample, which spanned the pre- and post-ACA periods. However, the longer time horizon was necessary to allow an adequate sample size for comparison. Moreover, our sensitivity analysis comparing SWOG NSCLC enrollments between 2014 and 2020 with Lung-MAP was consistent with the primary comparison. Second, we did not have data on individual-level income and education, which have been shown to affect patient participation in clinical trials.42 While ADI is a commonly used proxy measure, its emphasis on measures characterized in dollar values43 may underemphasize these key factors. Finally, we did not have access to nationally representative data on rurality or neighborhood deprivation for US patients with NSCLC and were, therefore, unable to compare these characteristics between Lung-MAP participants and the US NSCLC population.

In conclusion, the conduct of a biomarker-driven master protocol as a public-private partnership under the adult NCTN improved access to precision oncology clinical trials for older patients and socioeconomically vulnerable patients compared with conventionally conducted trials for NSCLC. However, older patients and patients of racial or ethnic minority remained under represented compared with the US cancer population, an important concern with respect to the adoption of these therapies in clinical practice. While eligibility criteria specific to the Lung-MAP protocol might have limited participation of female patients and Asian or Hispanic patients, further examination of other barriers to participation faced by these patient groups is warranted.

APPENDIX

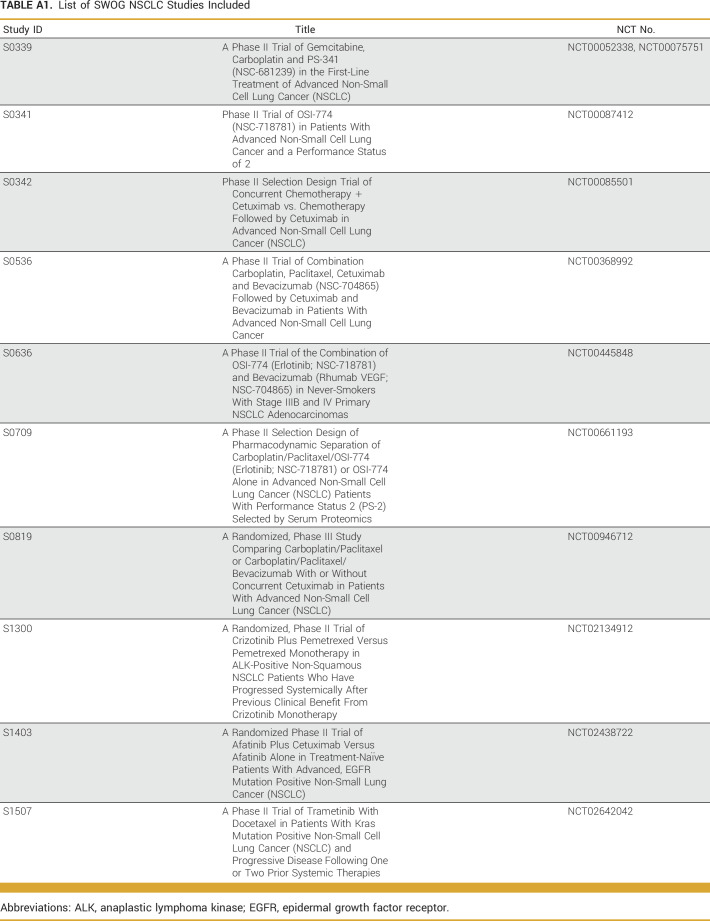

TABLE A1.

List of SWOG NSCLC Studies Included

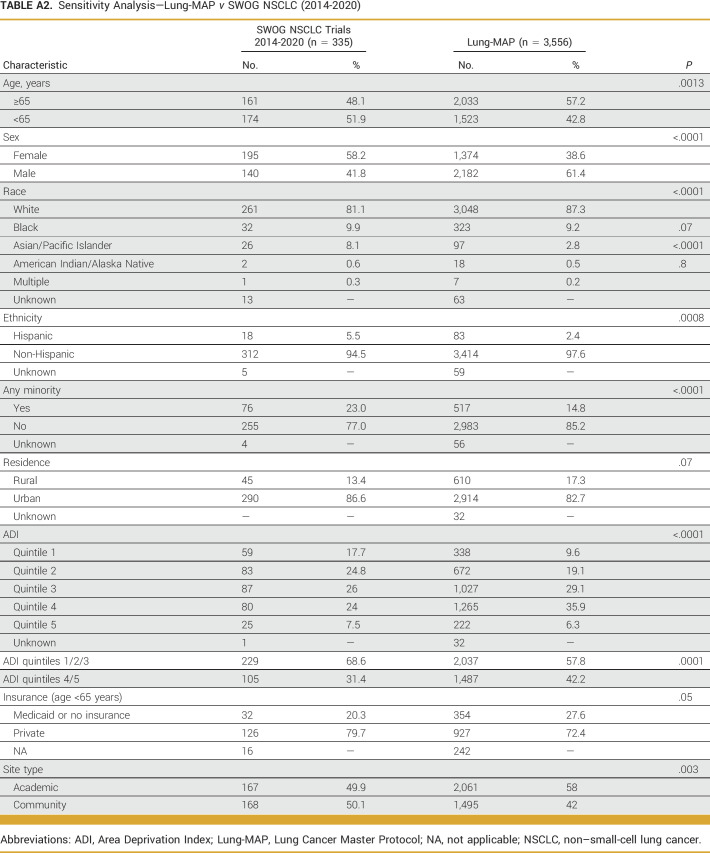

TABLE A2.

Sensitivity Analysis—Lung-MAP v SWOG NSCLC (2014-2020)

Roy S. Herbst

Leadership: Junshi Pharmaceuticals, Immunocore, American Association for Cancer Research, IASLC, Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer, SWOG

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Normunity, Checkpoint Therapeutics, Bolt Biotherapeutics, Immunocore

Consulting or Advisory Role: AstraZeneca, Genentech/Roche, Merck, Pfizer, AbbVie, Bristol Myers Squibb, Lilly, EMD Serono, Junshi Pharmaceuticals, Loxo, NextCure, Novartis, Sanofi, Seagen, Bolt Biotherapeutics, I-Mab, Mirati Therapeutics, Cybrexa Therapeutics, eFFECTOR Therapeutics, Candel Therapeutics, Oncternal Therapeutics, Xencor, Checkpoint Therapeutics, DynamiCure Biotechnology, Gilead/Forty Seven, HiberCell, Immune-Onc Therapeutics, Johnson and Johnson, Ocean Biomedical, OncoCyte, Refactor Health, Ribon Therapeutics, Janssen, Normunity, Regeneron, Revelar

Research Funding: AstraZeneca, Merck, Lilly, Genentech/Roche

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: American Cancer Society, IASLC, SWOG

David R. Gandara

Honoraria: Merck

Consulting or Advisory Role: AstraZeneca (Inst), Guardant Health (Inst), OncoCyte (Inst), IO Biotech (Inst), Roche/Genentech (Inst), Adagene (Inst), OncoHost (Inst)

Research Funding: Merck (Inst), Amgen (Inst), Genentech (Inst), AstraZeneca (Inst), Astex Pharmaceuticals (Inst)

Joel W. Neal

Honoraria: CME Matters, Clinical Care Options, Research to Practice, Medscape, Biomedical Learning Institute, Peerview, Prime Oncology, Projects in Knowledge, Rockpointe CME, MJH Life Sciences, Medical Educator Consortium, HMP Education

Consulting or Advisory Role: AstraZeneca, Genentech/Roche, Exelixis, Takeda, Lilly, Amgen, Iovance Biotherapeutics, Blueprint Medicines, Regeneron, Natera, Sanofi/Regeneron, D2G Oncology, Surface Oncology, Turning Point Therapeutics, Mirati Therapeutics, Gilead Sciences, AbbVie, Summit Therapeutics, Novartis, Novocure

Research Funding: Genentech/Roche (Inst), Merck (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Boehringer Ingelheim (Inst), Exelixis (Inst), Nektar (Inst), Takeda (Inst), Adaptimmune (Inst), GlaxoSmithKline (Inst), Janssen (Inst), AbbVie (Inst), Novocure (Inst)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Up To Date—Royalties

Ticiana A. Leal

Consulting or Advisory Role: Takeda, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, Bayer, EMD Serono, Merck, Boehringer Ingelheim, Blueprint Medicines, Genentech, Lilly, Janssen, Mirati Therapeutics, Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, Daiichi Sankyo/Astra Zeneca, Novocure, Amgen, Roche, Regeneron

Research Funding: Pfizer (Inst)

Jyoti D. Patel

Consulting or Advisory Role: AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Takeda Science Foundation, Genentech, Anheart Therapeutics

Konstantin H. Dragnev

Research Funding: Lilly (Inst), Merck (Inst), Roche/Genentech (Inst), Novartis (Inst), PharmaMar (Inst), Io Therapeutics (Inst), Molecular Templates (Inst), Amgen (Inst), Daiichi Sankyo/Astra Zeneca (Inst)

Saiama N. Waqar

Consulting or Advisory Role: AstraZeneca, Gilead Sciences

Research Funding: Pfizer (Inst), Daiichi Sankyo (Inst), Newlink Genetics (Inst), Xcovery (Inst), Vertex (Inst), Bristol Myers Squibb (Inst), Hengrui Therapeutics (Inst), Ignyta (Inst), AstraZeneca (Inst), Verastem (Inst), AbbVie (Inst), Roche (Inst), Lilly (Inst), Genentech (Inst), ARIAD (Inst), Loxo (Inst), Millennium (Inst), Elevation Oncology (Inst), Janssen (Inst), Cullinan Pearl (Inst), Ribon Therapeutics (Inst), Astellas Pharma (Inst)

Martin J. Edelman

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Biomarker Strategies, Creatv MicroTech

Consulting or Advisory Role: WindMIL, Flame Biosciences, Sanofi/Regeneron, Kanaph Therapeutics, Coherus Biosciences, GE Healthcare, BioAtla

Research Funding: Bristol Myers Squibb (Inst), Apexigen (Inst), Nektar (Inst), GlaxoSmithKline (Inst), Windmil (Inst), United Therapeutics (Inst)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Patent application for radiopharmaceutical to treat small cell lung cancer (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Nektar

Other Relationship: AstraZeneca/MedImmune, Boehringer Ingelheim, Takeda, Seagen, Anheart Therapeutics

Ellen V. Sigal

Consulting or Advisory Role: EQRx, GRAIL

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: AstraZeneca

Michael L. LeBlanc

Consulting or Advisory Role: Agios

Karen Kelly

Consulting or Advisory Role: AstraZeneca, Eisai, Sanofi

Research Funding: EMD Serono (Inst), Genentech (Inst), AbbVie (Inst), Regeneron (Inst), Astellas Pharma (Inst), Tizona Therapeutics, Inc (Inst), Lilly (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Amgen (Inst), Bristol Myers Squibb (Inst), Five Prime Therapeutics (Inst), Jounce Therapeutics (Inst)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Author Royalties for UpToDate, an evidence based, peer reviewed information resource, available via the web, desktop, and PDA

Jhanelle E. Gray

Honoraria: Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Merck, OncoCyte

Consulting or Advisory Role: AstraZeneca, Blueprint Medicines, Bristol Myers Squibb, EMD Serono, Lilly, Sanofi, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Loxo, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, AstraZeneca/MedImmune, Janssen Scientific Affairs, National Comprehensive Cancer Network, AbbVie, Regeneron

Research Funding: Merck (Inst), AstraZeneca (Inst), Bristol Myers Squibb (Inst), Boehringer Ingelheim (Inst), Genentech/Roche (Inst), G1 Therapeutics (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research (Inst), SWOG (Inst), Array BioPharma (Inst), ECOG-ACRIN (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Novartis, OncoCyte

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

DISCLAIMER

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

PRIOR PRESENTATION

Presented in part at the ASCO Annual Meeting, Chicago, IL, June 3-7, 2022.

SUPPORT

Supported by the National Institutes of Health (CA180888, CA180819, CA180820, CA180821, CA180868, CA189858, CA189821, CA189830, CA239767, CA189971, CA180826, CA180828, CA180846, and CA180858) and by AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Genentech, and Pfizer through the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health, in partnership with Friends of Cancer Research.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Riha Vaidya, Joseph M. Unger, Roy S. Herbst, Jyoti D. Patel, Martin J. Edelman, Ellen V. Sigal, Shakun Malik, Charles D. Blanke, Michael L. LeBlanc, Jhanelle E. Gray, Mary W. Redman

Financial support: Joseph M. Unger, Michael L. LeBlanc

Administrative support: Ticiana A. Leal, Stacey J. Adam, Shakun Malik, Charles D. Blanke, Michael L. LeBlanc, Jhanelle E. Gray

Provision of study materials or patients: David R. Gandara, Jyoti D. Patel, Karen Kelly, Mary W. Redman

Collection and assembly of data: Riha Vaidya, Lu Qian, Katherine Minichiello, Roy S. Herbst, Stacey J. Adam, Michael L. LeBlanc, Jhanelle E. Gray, Mary W. Redman

Data analysis and interpretation: Riha Vaidya, Joseph M. Unger, Lu Qian, Roy S. Herbst, David R. Gandara, Joel W. Neal, Ticiana A. Leal, Jyoti D. Patel, Konstantin H. Dragnev, Saiama N. Waqar, Martin J. Edelman, Charles D. Blanke, Karen Kelly, Jhanelle E. Gray, Mary W. Redman

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/po/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Roy S. Herbst

Leadership: Junshi Pharmaceuticals, Immunocore, American Association for Cancer Research, IASLC, Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer, SWOG

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Normunity, Checkpoint Therapeutics, Bolt Biotherapeutics, Immunocore

Consulting or Advisory Role: AstraZeneca, Genentech/Roche, Merck, Pfizer, AbbVie, Bristol Myers Squibb, Lilly, EMD Serono, Junshi Pharmaceuticals, Loxo, NextCure, Novartis, Sanofi, Seagen, Bolt Biotherapeutics, I-Mab, Mirati Therapeutics, Cybrexa Therapeutics, eFFECTOR Therapeutics, Candel Therapeutics, Oncternal Therapeutics, Xencor, Checkpoint Therapeutics, DynamiCure Biotechnology, Gilead/Forty Seven, HiberCell, Immune-Onc Therapeutics, Johnson and Johnson, Ocean Biomedical, OncoCyte, Refactor Health, Ribon Therapeutics, Janssen, Normunity, Regeneron, Revelar

Research Funding: AstraZeneca, Merck, Lilly, Genentech/Roche

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: American Cancer Society, IASLC, SWOG

David R. Gandara

Honoraria: Merck

Consulting or Advisory Role: AstraZeneca (Inst), Guardant Health (Inst), OncoCyte (Inst), IO Biotech (Inst), Roche/Genentech (Inst), Adagene (Inst), OncoHost (Inst)

Research Funding: Merck (Inst), Amgen (Inst), Genentech (Inst), AstraZeneca (Inst), Astex Pharmaceuticals (Inst)

Joel W. Neal

Honoraria: CME Matters, Clinical Care Options, Research to Practice, Medscape, Biomedical Learning Institute, Peerview, Prime Oncology, Projects in Knowledge, Rockpointe CME, MJH Life Sciences, Medical Educator Consortium, HMP Education

Consulting or Advisory Role: AstraZeneca, Genentech/Roche, Exelixis, Takeda, Lilly, Amgen, Iovance Biotherapeutics, Blueprint Medicines, Regeneron, Natera, Sanofi/Regeneron, D2G Oncology, Surface Oncology, Turning Point Therapeutics, Mirati Therapeutics, Gilead Sciences, AbbVie, Summit Therapeutics, Novartis, Novocure

Research Funding: Genentech/Roche (Inst), Merck (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Boehringer Ingelheim (Inst), Exelixis (Inst), Nektar (Inst), Takeda (Inst), Adaptimmune (Inst), GlaxoSmithKline (Inst), Janssen (Inst), AbbVie (Inst), Novocure (Inst)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Up To Date—Royalties

Ticiana A. Leal

Consulting or Advisory Role: Takeda, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, Bayer, EMD Serono, Merck, Boehringer Ingelheim, Blueprint Medicines, Genentech, Lilly, Janssen, Mirati Therapeutics, Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, Daiichi Sankyo/Astra Zeneca, Novocure, Amgen, Roche, Regeneron

Research Funding: Pfizer (Inst)

Jyoti D. Patel

Consulting or Advisory Role: AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Takeda Science Foundation, Genentech, Anheart Therapeutics

Konstantin H. Dragnev

Research Funding: Lilly (Inst), Merck (Inst), Roche/Genentech (Inst), Novartis (Inst), PharmaMar (Inst), Io Therapeutics (Inst), Molecular Templates (Inst), Amgen (Inst), Daiichi Sankyo/Astra Zeneca (Inst)

Saiama N. Waqar

Consulting or Advisory Role: AstraZeneca, Gilead Sciences

Research Funding: Pfizer (Inst), Daiichi Sankyo (Inst), Newlink Genetics (Inst), Xcovery (Inst), Vertex (Inst), Bristol Myers Squibb (Inst), Hengrui Therapeutics (Inst), Ignyta (Inst), AstraZeneca (Inst), Verastem (Inst), AbbVie (Inst), Roche (Inst), Lilly (Inst), Genentech (Inst), ARIAD (Inst), Loxo (Inst), Millennium (Inst), Elevation Oncology (Inst), Janssen (Inst), Cullinan Pearl (Inst), Ribon Therapeutics (Inst), Astellas Pharma (Inst)

Martin J. Edelman

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Biomarker Strategies, Creatv MicroTech

Consulting or Advisory Role: WindMIL, Flame Biosciences, Sanofi/Regeneron, Kanaph Therapeutics, Coherus Biosciences, GE Healthcare, BioAtla

Research Funding: Bristol Myers Squibb (Inst), Apexigen (Inst), Nektar (Inst), GlaxoSmithKline (Inst), Windmil (Inst), United Therapeutics (Inst)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Patent application for radiopharmaceutical to treat small cell lung cancer (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Nektar

Other Relationship: AstraZeneca/MedImmune, Boehringer Ingelheim, Takeda, Seagen, Anheart Therapeutics

Ellen V. Sigal

Consulting or Advisory Role: EQRx, GRAIL

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: AstraZeneca

Michael L. LeBlanc

Consulting or Advisory Role: Agios

Karen Kelly

Consulting or Advisory Role: AstraZeneca, Eisai, Sanofi

Research Funding: EMD Serono (Inst), Genentech (Inst), AbbVie (Inst), Regeneron (Inst), Astellas Pharma (Inst), Tizona Therapeutics, Inc (Inst), Lilly (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Amgen (Inst), Bristol Myers Squibb (Inst), Five Prime Therapeutics (Inst), Jounce Therapeutics (Inst)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Author Royalties for UpToDate, an evidence based, peer reviewed information resource, available via the web, desktop, and PDA

Jhanelle E. Gray

Honoraria: Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Merck, OncoCyte

Consulting or Advisory Role: AstraZeneca, Blueprint Medicines, Bristol Myers Squibb, EMD Serono, Lilly, Sanofi, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Loxo, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, AstraZeneca/MedImmune, Janssen Scientific Affairs, National Comprehensive Cancer Network, AbbVie, Regeneron

Research Funding: Merck (Inst), AstraZeneca (Inst), Bristol Myers Squibb (Inst), Boehringer Ingelheim (Inst), Genentech/Roche (Inst), G1 Therapeutics (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research (Inst), SWOG (Inst), Array BioPharma (Inst), ECOG-ACRIN (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Novartis, OncoCyte

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1. Collins FS, Varmus H. A new initiative on precision medicine. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:793–795. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1500523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Huey RW, Hawk E, Offodile AC. Mind the gap: Precision oncology and its potential to widen disparities. J Oncol Pract. 2019;15:301–304. doi: 10.1200/JOP.19.00102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Landry LG, Ali N, Williams DR, et al. Lack of diversity in genomic databases is a barrier to translating precision medicine research into practice. Health Aff. 2018;37:780–785. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Haslem DS, Norman SBV, Fulde G, et al. A retrospective analysis of precision medicine outcomes in patients with advanced cancer reveals improved progression-free survival without increased health care costs. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13:e108–e119. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2016.011486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Howlader N, Forjaz G, Mooradian MJ, et al. The effect of advances in lung-cancer treatment on population mortality. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:640–649. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1916623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cooper KE, Abdallah KE, Angove RSM, et al. Navigating access to cancer care: Identifying barriers to precision cancer medicine. Ethn Dis. 2022;32:39–48. doi: 10.18865/ed.32.1.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sadik H, Pritchard D, Keeling D-M, et al. Impact of clinical practice gaps on the implementation of personalized medicine in advanced non–small-cell lung cancer. JCO Precis Oncol. 2022;6:e2200246. doi: 10.1200/PO.22.00246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ersek JL, Black LJ, Thompson MA, et al. Implementing precision medicine programs and clinical trials in the community-based oncology practice: Barriers and best practices. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2018;38:188–196. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_200633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Redman MW, Papadimitrakopoulou VA, Minichiello K, et al. Biomarker-driven therapies for previously treated squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (Lung-MAP SWOG S1400): A biomarker-driven master protocol. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:1589–1601. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30475-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Woodcock J, LaVange LM. Master protocols to study multiple therapies, multiple diseases, or both. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:62–70. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1510062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Cancer Institute . NCTN: NCI’s National Clinical Trials Network. https://www.cancer.gov/research/infrastructure/clinical-trials/nctn . [Google Scholar]

- 12. Loree JM, Anand S, Dasari A, et al. Disparity of race reporting and representation in clinical trials leading to cancer drug approvals from 2008 to 2018. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5:e191870. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.1870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Unger JM, Hershman DL, Osarogiagbon RU, et al. Representativeness of Black patients in cancer clinical trials sponsored by the National Cancer Institute compared with pharmaceutical companies. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2020;4:pkaa034. doi: 10.1093/jncics/pkaa034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hutchins LF, Unger JM, Crowley JJ, et al. Underrepresentation of patients 65 years of age or older in cancer-treatment trials. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:2061–2067. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912303412706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Herbst RS, Gandara DR, Hirsch FR, et al. Lung master protocol (Lung-MAP)—A biomarker-driven protocol for accelerating development of therapies for squamous cell lung cancer: SWOG S1400. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:1514–1524. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kind AJH, Buckingham WR. Making neighborhood-disadvantage metrics accessible—The Neighborhood Atlas. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2456–2458. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1802313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Cancer Institute . Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program SEER*Stat Database: Incidence—SEER Research Data, 18 Registries, Nov 2020 Sub (1975-2018)—Linked to County Attributes—Time Dependent (1990-2019) Income/Rurality, 1969-2020 Counties, National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, Released April 2021, Based on the November 2020 Submission. https://seer.cancer.gov/data-software/documentation/seerstat/nov2020/ [Google Scholar]

- 18. Subramanian J, Morgensztern D, Goodgame B, et al. Distinctive characteristics of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in the young: A Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) analysis. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:23–28. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181c41e8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Duma N, Aguilera JV, Paludo J, et al. Representation of minorities and women in oncology clinical trials: Review of the past 14 years. J Oncol Pract. 2018;14:e1–e10. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2017.025288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ouellette D, Desbiens G, Emond C, et al. Lung cancer in women compared with men: Stage, treatment, and survival. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;66:1140–1143. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(98)00557-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Visbal AL, Williams BA, Nichols FC, et al. Gender differences in non–small-cell lung cancer survival: An analysis of 4,618 patients diagnosed between 1997 and 2002. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78:209–215. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2003.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Steuer CE, Behera M, Berry L, et al. Role of race in oncogenic driver prevalence and outcomes in lung adenocarcinoma: Results from the Lung Cancer Mutation Consortium. Cancer. 2016;122:766–772. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chapman AM, Sun KY, Ruestow P, et al. Lung cancer mutation profile of EGFR, ALK, and KRAS: Meta-analysis and comparison of never and ever smokers. Lung Cancer. 2016;102:122–134. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2016.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stein JN, Rivera MP, Weiner A, et al. Sociodemographic disparities in the management of advanced lung cancer: A narrative review. J Thorac Dis. 2021;13:3772–3800. doi: 10.21037/jtd-20-3450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Enewold L, Thomas A. Real-world patterns of EGFR testing and treatment with erlotinib for non-small cell lung cancer in the United States. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0156728. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Canedo JR, Wilkins CH, Senft N, et al. Barriers and facilitators to dissemination and adoption of precision medicine among Hispanics/Latinos. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:603. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-08718-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yeh VM, Bergner EM, Bruce MA, et al. Can precision medicine actually help people like me? African American and Hispanic perspectives on the benefits and barriers of precision medicine. Ethn Dis. 2020;30:149–158. doi: 10.18865/ed.30.S1.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Unger JM, Hershman DL, Till C, et al. “When offered to participate”: A systematic review and meta-analysis of patient agreement to participate in cancer clinical trials. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2020;113:244–257. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djaa155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous-cell non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:123–135. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1627–1639. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Herbst RS, Baas P, Kim D-W, et al. Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-L1-positive, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387:1540–1550. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01281-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rittmeyer A, Barlesi F, Waterkamp D, et al. Atezolizumab versus docetaxel in patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (OAK): A phase 3, open-label, multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;389:255–265. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32517-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gross CP, Meyer CS, Ogale S, et al. Associations between Medicaid insurance, biomarker testing, and outcomes in patients with advanced NSCLC. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2022;20:479–487.e2. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2021.7083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kehl KL, Lathan CS, Johnson BE, et al. Race, poverty, and initial implementation of precision medicine for lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;111:431–434. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djy202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Maguire FB, Morris CR, Parikh-Patel A, et al. Disparities in systemic treatment use in advanced-stage non–small cell lung cancer by source of health insurance. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2019;28:1059–1066. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-18-0823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Larson KL, Huang B, Chen Q, et al. EGFR testing and erlotinib use in non-small cell lung cancer patients in Kentucky. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0237790. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yabroff KR, Han X, Zhao J, et al. Rural cancer disparities in the United States: A multilevel framework to improve access to care and patient outcomes. JCO Oncol Pract. 2020;16:409–413. doi: 10.1200/OP.20.00352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Shugarman LR, Sorbero MES, Tian H, et al. An exploration of urban and rural differences in lung cancer survival among Medicare beneficiaries. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:1280–1287. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.099416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Johnson AM, Hines RB, Johnson JA, et al. Treatment and survival disparities in lung cancer: The effect of social environment and place of residence. Lung Cancer. 2014;83:401–407. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Norris RP, Dew R, Sharp L, et al. Are there socio-economic inequalities in utilization of predictive biomarker tests and biological and precision therapies for cancer? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2020;18:282. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01753-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Unger JM, Xiao H, Vaidya R, et al. The Medicaid expansion of the Affordable Care Act and participation of patients with Medicaid in cancer clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40:6505. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2023.2800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Unger JM, Hershman DL, Albain KS, et al. Patient income level and cancer clinical trial participation. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:536–542. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.4553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hannan EL, Wu Y, Cozzens K, et al. The neighborhood Atlas Area Deprivation Index for measuring socioeconomic status: An overemphasis on home value. Health Aff. 2023;42:702–709. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2022.01406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]