Abstract

Background and study aims Simethicone is useful as premedication for upper endoscopy because of its antifoaming effects. We aimed to evaluate the effect of timing of simethicone administration on mucosal visibility.

Patients and methods In this multicenter, randomized, endoscopist-blinded study, patients scheduled for upper endoscopy were randomized to receive 40 mg simethicone at the following time points prior to the procedure: 20 to 30 minutes (early group), 0 to 10 minutes (late group) or 20 mg simethicone at both time points (split-dose group). Images were taken from nine predefined locations in the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum before endoscopic flushing. Each image was scored on mucosal visibility by three independent endoscopists on a 4-point scale (lower scores indicating better visibility), with adequate mucosal visibility defined as a score ≤ 2. Primary outcome was the percentage of patients with adequate total mucosal visibility (TMV), reached if all median subscores for each location were ≤ 2.

Results A total of 386 patients were included (early group: 132; late group: 128; split-dose group: 126). Percentages of adequate TMV were 55%, 42%, and 61% in the early, late, and split-dose group, respectively ( P < 0.01). Adequate TMV was significantly higher in the split-dose group compared to the late group ( P < 0.01), but not compared to the early group ( P = 0.29). Differences between groups were largest in the stomach, where percentages of adequate mucosal visibility were higher in the early (68% vs 53%, P = 0.03) and split-dose group (69% vs 53%, P = 0.02) compared to the late group.

Conclusions Mucosal visibility can be optimized with early simethicone administration, either as a single administration or in a split-dose regimen.

Keywords: Precancerous conditions & cancerous lesions (displasia and cancer) stomach; Barrett's and adenocarcinoma; Preparation, quality and logistical aspects; Quality management; Diagnosis and imaging (inc chromoendoscopy, NBI, iSCAN, FICE, CLE)

Introduction

Clear visualization of the gastrointestinal mucosal surface is essential for adequate upper endoscopy. Previous research has shown that in patients with upper gastrointestinal cancers, misdiagnosis during previous endoscopy is not uncommon, with missing rates ranging between 6.0% to 9.4% 1 2 3 4 5 6 . Misdiagnosis can be partly attributed to lesions overlooked by endoscopists 6 7 . Optimal mucosal visibility, therefore, may not only shorten total procedure time, as it reduces the need for washing and suctioning, but might also improve early detection of small neoplastic lesions.

Standard preparation for upper endoscopy includes a fasting period 8 9 , with or without the use of premedication. Premedication for upper endoscopy may include antifoaming agents and mucolytic agents. While in most East Asian countries administration of premedication is strongly recommended and has become standard of care 10 11 , it is not uniformly implemented in the United States and Europe.

Simethicone (which is a mixture of polydimethylsiloxane and silicon dioxide) is one of the substances frequently used as premedication for upper endoscopy. In the majority of previous studies, it has shown to improve mucosal visibility compared to no premedication or water only 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 . Simethicone has an antifoaming effect because it lowers the surface tension of air bubbles, thereby causing the coalescence of small bubbles into larger ones. Several dosages of simethicone have been studied over the years, and dosages ranging from 40 to 1000 mg all have shown to improve mucosal visibility 12 13 17 20 24 . Fewer data are available on the timing of simethicone as premedication for upper endoscopy.

Therefore, the aim of the current study was to evaluate the effect of timing of simethicone as premedication for upper endoscopy on mucosal visibility.

Patients and methods

Study design

This prospective, endoscopist-blinded, parallel-group randomized clinical trial with a superiority study design was performed in two different community hospitals in the Netherlands between February 2020 and February 2022. All participants signed informed consent prior to enrollment in the study. The medical ethics review boards of the two participating hospitals approved the trial, after which it was registered in the Dutch Trial Register (www.trialregister.nl; NL8383). The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and reported according to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines for parallel-group randomized studies 27 .

Participants

Patients were considered eligible if they: (1) had reached an age of 18 years or older; and (2) were scheduled for an elective upper endoscopy. Under the original protocol, only patients undergoing endoscopy with sedation were eligible. During the trial, the study team decided patients could be included regardless of the use and type of sedation, as the use of sedation would be unlikely to influence our outcome measurements (the trial protocol was amended accordingly and reviewed by the medical ethics review board).

Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) previous upper gastrointestinal surgery; (2) achalasia; (3) known stenosis of the upper gastrointestinal tract;(4) known gastroparesis; (5) allergies to simethicone; and (6) pregnancy.

Endoscopic procedures

Participants were randomly assigned to one of three parallel study groups after arrival at the Endoscopy Department: the early group, late group, and split-dose group. The early group received 40 mg simethicone in 5 mL water on arrival at the endoscopy department and 5 mL water in the endoscopy suite shortly before endoscopy; the late group received 5 mL water on arrival at the endoscopy department and 40 mg simethicone in 5 mL water in the endoscopy suite shortly before endoscopy; and the split-dose group received 20 mg simethicone in 5 mL water on arrival at the endoscopy department and 20 mg simethicone in 5 mL water in the endoscopy suite shortly before endoscopy. Time of intake was reported for both drinks. Of note, the mucolytic agent N-acetylcysteine was not part of the premedication as this is not standard practice in our hospitals.

All endoscopies were performed by four experienced endoscopists (R.V., J.B., L.A.H., B.W.). Endoscopic images were captured at nine predefined locations before flushing: the proximal esophagus, distal esophagus, corpus (antegrade position), antrum, angulus (in partial inversion) corpus including greater curvature (retroflex position), cardia (in inversion), duodenal bulb, and the descending part of the duodenum. Suctioning of fluid in the stomach was allowed to avoid pulmonary aspiration. During the procedure, the endoscopist scored his or her satisfaction for cleanness of the mucosa on a scale from 1 to 10, with 1 being least satisfaction and 10 complete satisfaction.

Thereafter, the endoscopist was asked to start flushing with water until adequate mucosal views were obtained in the duodenum, stomach, and esophagus. An endoscopic flushing pump was used for this purpose. The number of flushes and the total flushing time required to achieve adequate mucosal views were recorded. Total procedure time and endoscopic findings were also recorded.

Mucosal visibility score

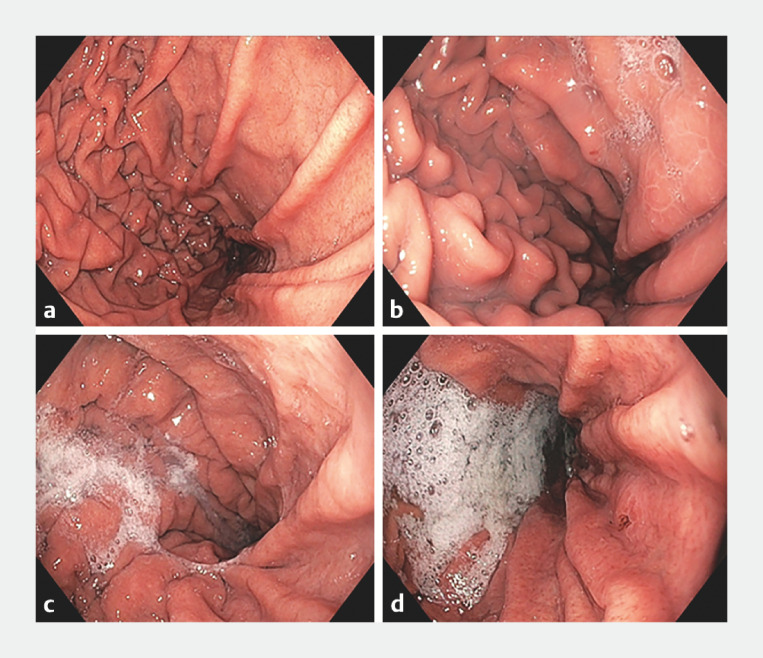

Two independent, experienced endoscopists (A.B. and L.A.H.), blinded to the timing of administration of simethicone, scored all still images using a 4-point scale previously described by Basford et al ( Fig. 1 ) 20 :

Fig. 1.

Mucosal visibility score examples for one predefined location (corpus antegrade position). a Score 1: no adherent mucus and clear views. b Score 2: a thin coating of mucus that does not obscure views. c Score 3: mucus/bubbles partially obscuring views. d Score 4: heavy mucus/bubbles obscuring views.

No adherent mucus and clear views of the mucosa.

A thin coating of mucus that did not obscure views of the mucosa.

Some mucus/bubbles partially obscuring views of the mucosa (i.e. a small mucosal lesion might be missed without flushing).

Heavy mucus/bubbles obscuring views of the mucosa (i.e. extensive flushing is needed to avoid missing small mucosal lesions).

The endoscopists did not receive formal training prior to their assessments. In case of discrepancies between the two reviewers, the images were also scored by a third independent endoscopist (A.A-T.), and the median of the three readings was used as the final score.

Per individual patient, mucosal visibility was evaluated on three different levels: 1) total mucosal visibility (TMV), defined as adequate if each score of the nine predefined locations was ≤ 2 and considered inadequate if the score was ≥ 3 for one or more locations; 2) per organ (i.e. esophagus, stomach, duodenum), with mucosal visibility defined as adequate if all scores for the predefined locations in that specific organ were ≤ 2 and considered inadequate if the score was ≥ 3 for one or more locations in the concerning organ; and 3) for each of the nine predefined locations, with mucosal visibility defined as adequate if the score for the still images of that particular location was ≤ 2. A score ≥ 3 was considered inadequate.

Outcomes

The predefined primary outcome for this study was the percentage of patients with adequate TMV. Predefined secondary outcomes were: 1) the percentage of patients with adequate mucosal visibility for each organ separately; 2) the percentage of patients with adequate mucosal visibility for each of the nine predefined locations; 3) the satisfaction of the performing endoscopist concerning the cleanness of the mucosa, as assessed during the procedure; 4) the total flushing time; 5) the number of fluid flushes; and 6) the percentage of patients with newly detected dysplastic or neoplastic lesions during endoscopy.

In post-hoc analyses, we also evaluated the percentage of patients with a mucosal visibility score of 4 for at least one of the nine locations and the percentage of patients with adequate mucosal visibility (i.e. TMV and mucosal visibility per organ separately) in relation to the recorded time of simethicone administration before endoscopy.

Sample size

Our sample size calculation was based on a pilot in our own patient population consisting of 59 patients, assigned to the three study groups based on the day of the endoscopy program: the early group, late group, and split-dose group. One blinded endoscopist assessed nine endoscopic images in the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum on the mucosal visibility scale described by Basford et al 20 . Adequate TMV in this pilot was 14% for the early group, and 26% and 67% for the late and split-dose groups, respectively. Because in most Dutch hospitals the administration of simethicone shortly before upper endoscopy is the current standard of care, we considered the late group as the reference group. To demonstrate an increase of 20% in adequate TMV in the other study groups, the calculated sample size for each group was 119 patients (power of 80%, two-sided 1.7% significance level (5%/3) using Bonferroni correction rather than Hommel’s method for multiplicity adjustment 28 , assuming 10% dropout rate), resulting in 393 patients in total.

Randomization

After the nurse practitioner or research fellow obtained consent, patients were randomized into one of three study groups on arrival at the endoscopy department on the day of the procedure. We performed 1:1:1 block-randomization with block-sizes of six to create three parallel groups, stratified by performing endoscopist. The randomization was performed by a nurse practitioner or research fellow. The random allocation sequence was generated using the randomization website https://www.sealedenvelope.com . We used the REDCap randomization module to guide the randomization process 29 .

Blinding

The endoscopists performing the endoscopies and the independent endoscopists scoring the images for TMV were blinded to the randomization process.

Statistical methods

Means with standard deviations were used for normally distributed variables, and medians with 25 th and 75 th percentiles (p25-p75) for variables with a skewed distribution. Categorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages of total.

The percentages of adequate TMV in the study groups were compared using Chi-square tests. Subanalyses per organ and for each predefined location were performed in the same manner. Mean time of fluid flushing, and mean number of additional fluid flushes required to achieve adequate mucosal views were compared using One-Way Anova or Kruskal Wallis test, depending on the distribution. The percentage of newly diagnosed lesions was compared using a Chi-square test, as well as the percentage of patients with a mucosal visibility score of 4 in at least one of the nine locations. The percentage of adequate mucosal visibility scores in relation to the recorded time of simethicone administration was analyzed using a Chi-square test for trend in proportions. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. In case of multiple comparisons, adjusted P values derived using Hommel’s method were derived and reported 30 . Therefore, P < 0.05 represents statistically significant findings.

As this was a clinical trial, missing data were limited to a very small number of patients (3%) and observations (< 0.1%). Therefore, no imputation methods were used to handle missing data. Observations with missing values are listed as frequencies and percentages of total. R version 3.5.1 for Windows was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

Patient characteristics

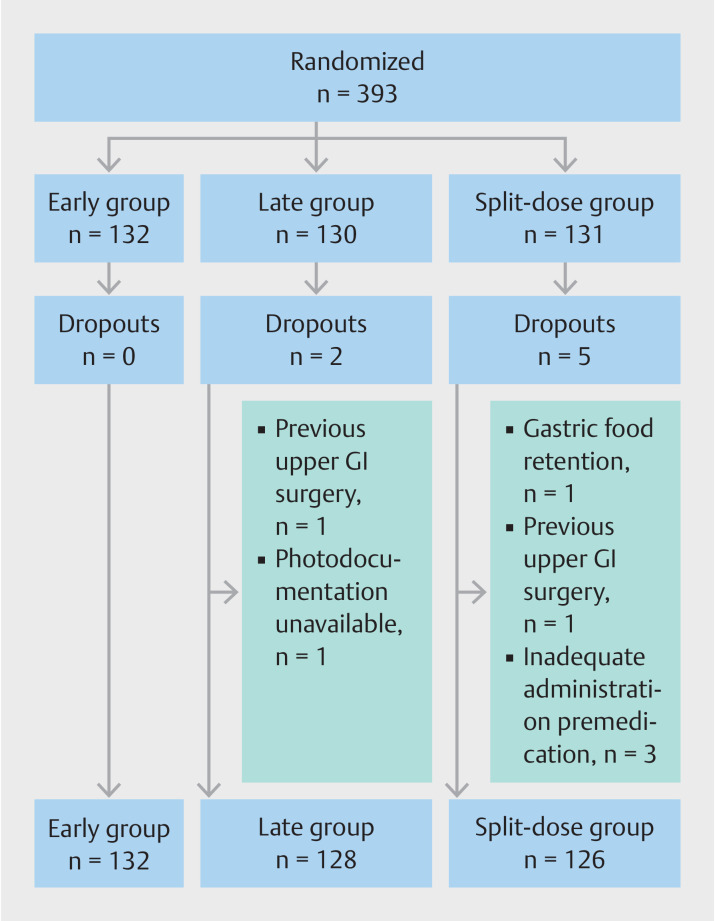

Of the 393 randomized patients, 132 were randomized in the early group, 130 in the late group, and 131 in the split-dose group. Seven patients were excluded; two patients were excluded because of not meeting the eligibility criteria and five patients due to procedural failures ( Fig. 2 ). Therefore, 386 patients were included in the final analysis. Patient baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1 . Most included patients were male (70%) and the mean age was 66 years. The main indications for endoscopy were Barrett’s esophagus (BE) or follow-up after treatment of BE neoplasia, which accounted for 68% of all endoscopies. Eighteen percent of patients used medication that could affect gastric emptying, without significant differences between study groups. While more than half of endoscopies were performed by the same endoscopist, the number of endoscopies per study group was similar for each performing endoscopist separately due to the stratified randomization ( Table 1 ).

Fig. 2.

Patient flow diagram.

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of the included patients and their endoscopies.

| Total (n = 386) | Early group (n = 132) | Late group (n = 128) | Split-dose group (n = 126) | |

| *Metoclopramide, ondansetron, erythromycin, domperidone, opioids, levodopa, tricyclic antidepressants, beta-agonists, anticholinergics. GI, gastrointestinal; NA, not applicable; p25-p75, 25 th to 75 th percentile; SD, standard deviation. | ||||

| Baseline characteristics patients | ||||

| Age , mean (SD) | 66 (12) | 66 (12) | 67 (13) | 66 (12) |

| Male , n (%) | 269 (70) | 92 (70) | 91 (71) | 86 (68) |

| ASA classification , n (%) | ||||

| I | 34 (9) | 10 (8) | 12 (9) | 12 (10) |

| II | 320 (83) | 115 (87) | 104 (81) | 101 (80) |

| III | 32 (8) | 7 (5) | 12 (9) | 13 (10) |

| Indication endoscopy , n (%) | ||||

| Barrett’s esophagus | 127 (33) | 46 (35) | 40 (31) | 41 (33) |

| Follow-up after treatment Barrett’s esophagus | 137 (35) | 42 (32) | 49 (38) | 46 (37) |

| Dyspepsia/epigastric pain | 41 (11) | 13 (10) | 14 (11) | 14 (11) |

| Gastroesophageal reflux | 21 (5) | 6 (5) | 7 (5) | 8 (6) |

| Anemia | 12 (3) | 5 (4) | 5 (4) | 2 (2) |

| Screening malignancy | 12 (3) | 5 (4) | 3 (2) | 4 (3) |

| Dysphagia | 6 (2) | 1 (0.8) | 2 (2) | 3 (2) |

| Suspected upper GI bleeding | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Suspected celiac disease | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Other | 28 (7) | 14 (11) | 8 (6) | 6 (5) |

| Diabetes mellitus , n (%) | 53 (14) | 22 (17) | 19 (15) | 12 (10) |

| Medication affecting gastric emptying *, n (%) | 68 (18) | 17 (13) | 28 (22) | 23 (18) |

| Baseline characteristics endoscopy | ||||

| Performing endoscopist | ||||

| Endoscopist 1 | 211 (55) | 70 (53) | 70 (55) | 71 (56) |

| Endoscopist 2 | 84 (22) | 28 (21) | 28 (22) | 28 (22) |

| Endoscopist 3 | 55 (14) | 19 (14) | 18 (14) | 18 (14) |

| Endoscopist 4 | 43 (11) | 15 (11) | 14 (11) | 14 (11) |

| Sedation , n (%) | ||||

| Midazolam/fentanyl | 239 (62) | 80 (61) | 82 (64) | 77 (61) |

| Propofol | 79 (20) | 27 (20) | 27 (21) | 25 (20) |

| No sedation | 68 (18) | 25 (19) | 19 (15) | 24 (19) |

| Timing simethicone , minutes, median (p25-p75) | ||||

| First simethicone drink | 25 (19–33) | NA | 25 (19–33) | |

| Second simethicone drink | NA | 8 (6–10) | 8 (6–9) | |

| Duration endoscopy , minutes, median (p25-p75) | 8 (5–13) | 8 (5–12) | 9 (6–14) | 9 (5–14) |

Mucosal visibility scores

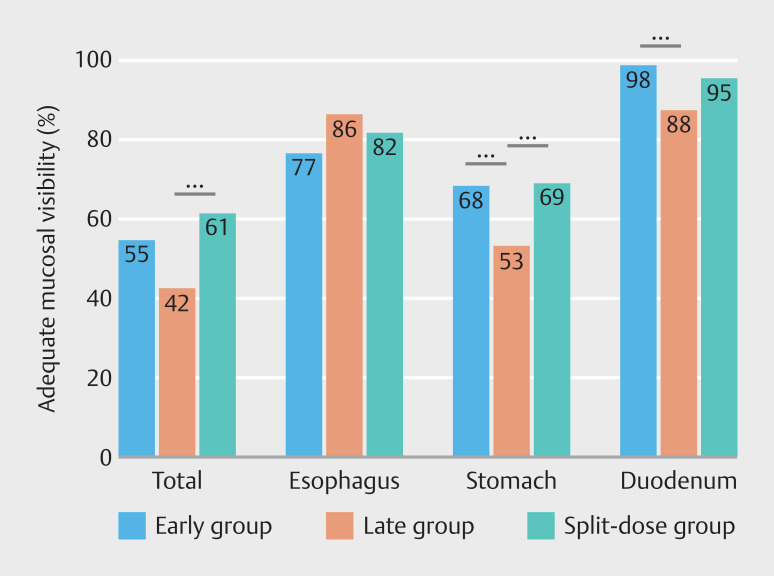

In 183 of the 386 included patients (47%), the TMV was considered adequate ( Table 2 ). TMV was assessed as adequate in 72 (55%), 54 (42%), and 77 patients (61%) in the early, late, and split-dose groups, respectively ( P < 0.01). The percentage of adequate TMV in the late group was significantly lower compared to the split-dose group (42% vs 61%, P < 0.01), but not for the late group compared to the early group (42% vs 55%, P = 0.09) ( Fig. 3 ).

Table 2 Primary and secondary outcomes.

| Total (n = 386) | Early group (n = 132) | Late group (n = 128) | Split-dose group (n = 126) | P value | ||

| *Newly detected lesions in esophagus stomach, duodenum after flushing. † Adjusted P values using Hommel’s correction method. TMV, total mucosal visibility; p25-p75, 25 th to 75 th percentile; SD, standard deviation. | ||||||

| Primary outcome | ||||||

| Adequate TMV , n (%) | 183 (47) | 72 (55) | 54 (42) | 77 (61) | < 0.01 |

Early vs. late = 0.09

†

Early vs. split-dose = 0.29 † Late vs. split-dose < 0.01 † |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||

| Adequate mucosal visibility esophagus , n (%) | 314 (81) | 101 (77) | 110 (86) | 103 (82) | 0.15 | |

| Adequate mucosal visibility stomach , n (%) | 245 (63) | 90 (68) | 68 (53) | 87 (69) | 0.01 |

Early vs. Late = 0.03

†

Early vs. split-dose = 0.88 † Late vs. split-dose = 0.02 † |

| Adequate mucosal visibility duodenum , n (%) | 362 (94) | 130 (98) | 112 (88) | 120 (95) | < 0.01 |

Early vs. late < 0.01

†

Early vs. split-dose = 0.13 † Late vs. split-dose = 0.06 † |

| Satisfaction performing endoscopist , median (SD) | 7.0 (6.0–8.0) 2 (0.5%) missing | 7.0 (6.5–8.0) 1 (0.8%) missing | 7.0 (6.0–8.0) 1 (0.8%) missing | 8.0 (6.0–8.0) | 0.62 | |

| Flushing time , seconds, median (p25-p75) | 39 (20–60) 3 (0.8%) missing | 38 (20–58) | 40 (22–62) 3 (2%) missing | 39 (17–60) | 0.73 | |

| Number of additional flushes , median (p25-p75) | 3 (2–5) 3 (0.8%) missing | 3 (2–5) | 4 (3–5) 3 (2%) missing | 3 (2–5) | 0.36 | |

| Detected dysplastic lesions *, n (%) | 41 (11) | 16 (12) | 12 (9) | 13 (10) | 0.77 | |

Fig. 3.

Percentages adequate total mucosal visibility (TMV) and adequate mucosal visibility per organ. Adequate TMV was defined as a score ≤ 2 for all nine of the predefined locations. Adequate mucosal visibility per organ was defined as a score ≤ 2 for each of the respective predefined locations in the esophagus, stomach or duodenum separately. Early group = 40 mg simethicone 20 to 30 minutes prior to gastroscopy. Late group = 40 mg simethicone 0 to 10 minutes prior to gastroscopy. Split-dose group = 20 mg simethicone 20 to 30 minutes, and 20 mg simethicone 0 to 10 minutes prior to gastroscopy. *** denotes statistical significance.

Differences in adequate mucosal visibility per organ were most pronounced in the stomach ( Table 2 , Fig. 3 ). Both the early and split-dose groups had higher percentages of adequate mucosal visibility in the stomach compared to the late group (68% vs 53%, P = 0.03 and 69% vs 53%, P = 0.02). As for the duodenum, only the early group scored higher in adequate mucosal visibility than the late group (98% vs 88%, P < 0.01), whereas this was not the case for scores in the split-dose group compared to the late group (95% vs 88%, P = 0.06). There were no significant differences among groups regarding adequate mucosal visibility of the esophagus. The distributions of mucosal visibility scores for each of the nine predefined locations separately are shown in Supplementary Table S1 .

A mucosal visibility score of 4 (i.e. heavy mucus/bubbles obscuring views of the mucosa for which extensive flushing is needed) was given for at least one location in the esophagus, stomach and duodenum in 50 individual patients (13%). In the late group, 24 patients (19%) received a score of 4 for at least one of the predefined locations, compared to 15 (11%) in the early group and 11 (9%) in the split-dose group ( P = 0.047).

Endoscopic parameters

Median satisfaction scores for the performing endoscopists concerning the cleanness of the mucosa during the endoscopy were 8.0 (p25-p75 6.0–8.0) for the split-dose group, as opposed to a median score 7.0 for both the early (p25-p75 6.5–8.0) and late groups (p25-p75 6.0–8.0) ( P = 0.62).

In the total cohort, a median of 39 seconds of flushing was necessary in a median of three flushes to achieve clear mucosal views in the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum, without significant differences between study groups. In addition, there were no significant differences in the percentage of newly detected (pre)cancerous lesions in the esophagus, stomach, or duodenum ( P = 0.77).

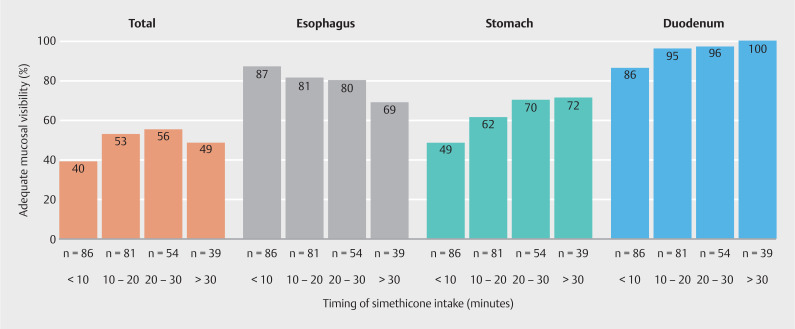

Simethicone administration time

Fig. 4 demonstrates the percentages of adequate mucosal visibility for patients randomized to the early and late groups only (n = 260) in relation to the recorded time of simethicone administration before endoscopy. The percentage of adequate TMV was highest when simethicone was administered between 20 to 30 minutes prior to upper endoscopy. For the esophagus, the highest percentage of adequate mucosal visibility was seen when a short time interval was used between simethicone intake and upper endoscopy (0–10 minutes), with decreasing percentages when the time interval increased ( P = 0.02 for trend). For both the stomach and duodenum, percentages of adequate mucosal visibility increased with an increasing time interval between simethicone administration and the start of the procedure ( P < 0.01 for trend).

Fig. 4.

Adequate mucosal visibility (%) in all patients (n = 260) randomized to either the early group (n = 132) or the late group (n = 128) in relation to the measured time (minutes) of simethicone administration prior to endoscopy. Early group = 40 mg simethicone scheduled at 20 to 30 minutes prior to gastroscopy. Late group = 40 mg simethicone scheduled at 0 to 10 minutes prior to gastroscopy. Of note: patients included in the split-dose group are not represented in this figure. Adequate total mucosal visibility was defined as a score ≤ 2 for all nine of the predefined locations. Adequate mucosal visibility per organ was defined as a score ≤ 2 for each of the respective predefined locations in the esophagus, stomach or duodenum separately.

Discussion

The presence of mucus and foam in the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum can hamper thorough assessment of the mucosal surface. An adequate pre-procedure preparation may help to improve mucosal visibility. In this multicenter, single-blind, randomized trial, we aimed to clarify the effect of timing of simethicone administration as premedication for upper endoscopy in relation to mucosal visibility. We compared three different simethicone intake regimens: early intake (20–30 minutes prior to endoscopy), late intake (0–10 minutes prior to endoscopy), and split-dose intake (20–30 minutes and 0–10 minutes prior to endoscopy). Our study demonstrated that overall, clearest mucosal views were obtained when simethicone was administered early (i.e. 20–30 minutes before endoscopy), either in a split-dose regimen or as a single dose. Although the highest percentage of adequate TMV was found in the split-dose group, the difference between the split-dose and early groups failed to reach statistical significance.

Current guidelines provide recommendations on fasting for solids and fluids, although the routine use of premedication prior to upper endoscopy is, unlike bowel preparation for colonoscopy 31 32 , not uniformly advised. Without specific guideline recommendations, the use of premedication varies considerably in daily practice. A relatively low dosage of simethicone was administered in a 5-mL solution in our study, according to the standard of care in our practices. Many studies have been published on the effects of simethicone as premedication for upper endoscopy. Irrespective of the dosage used, the vast majority of studies demonstrated clear beneficial effects of simethicone on improving mucosal visibility compared to placebo, including a reduction in total flushing and total procedure times 14 15 16 17 19 21 23 .

Fewer data are available on the optimal administration time for simethicone. Two studies have been published on the timing of premedication; however, assessing gastric mucosal visibility only. Sun et al. studied different time intervals for simethicone intake and concluded that a time interval of 31 to 60 minutes resulted in the best gastric visibility 33 . Woo et al. investigated a premedication mixture of pronase, dimethylpolysiloxane, and sodium bicarbonate, and found that the optimal time interval was between 10 to 30 minutes before upper endoscopy 34 . To our knowledge, our trial is the first primarily designed to evaluate the effect of timing of simethicone intake on the complete upper gastrointestinal tract.

Subsequently, we found that the effect of timing of simethicone intake is different for the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum. In the esophagus, decreasing percentages of adequate mucosal visibility with increasing time between simethicone intake and the start of the endoscopy were observed. On the contrary, for the stomach and duodenum, the percentage of adequate mucosal visibility scores increased with increasing time of intake. The highest percentage of adequate TMV in the split-dose group, therefore, is a logical consequence deriving from these findings, demonstrating the results of a balanced approach to maximize the effect in the esophagus, stomach and duodenum altogether.

How should our findings influence clinical practice? We demonstrated that impaired mucosal visualization occurred frequently in the stomach. Extensive cleansing of the gastric mucosa is particularly challenging and time-consuming as compared to the esophagus or duodenum, and longer procedure time can cause more discomfort in patients. At the same time, lesions in the stomach can be subtle and easy to overlook if they are covered by bubbles 3 6 . For practical reasons, simethicone administration strategies, therefore, may mainly focus on improving gastric mucosal visibility, with standard simethicone administration 20 to 30 minutes prior to upper endoscopy. In case of known or suspected esophageal pathology (e.g. if the endoscopy is performed in the context of BE surveillance), a second dose of simethicone administered 0 to 10 minutes prior to the procedure may be considered.

The main strengths of our study are its randomized, endoscopist-blinded design and the high-quality data collection. To reduce the level of subjectivity, mucosal visibility scores were derived from still images, assessed by three independent, blinded endoscopists. Lastly, the complete esophagus, stomach, and duodenum were explored and assessed regarding mucosal visibility, using nine standard photo documentation locations mentioned by the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guideline on performance measures for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy 9 .

Nonetheless, several limitations should be taken into account while interpreting the results of this study. First, when our study was conducted, no validated scoring tool was available to evaluate mucosal visibility during upper endoscopy. Many different scores have been used in previous studies. We chose to use the scoring system previously described by Basford et al 20 , based on the possibility of missing small mucosal lesions rather than required flushing volume. In our opinion, this is a more clinically relevant scale. However, in a recent study, a standardized scoring tool was found to have strong evidence of validity for the assessment of gastric and duodenal mucosal visibility 35 . Second, because two of the participating endoscopists were BE expert endoscopists in a tertiary referral hospital, the majority of study participants were BE patients. This will account for the high percentage of newly diagnosed dysplastic lesions in this study. Apart from this, we believe the results of our study can be generalized to all patients undergoing elective upper endoscopy. Third, we did not include a study arm without premedication, nor did we study the effect of timing of simethicone administration at different dosages. Considering that the beneficial effects of simethicone compared to placebo have been demonstrated in previous studies, it was decided to focus solely on simethicone administration time. As for dosage, low-dose simethicone was used in this study because it is routinely used in our practices. However, none of the study arms showed adequate TMV above 70%. The TMV might have been improved if we had used higher simethicone dosages. Fourth, this study was not designed nor powered to detect differences in dysplastic lesions during upper endoscopy. Dysplastic lesions were recorded after all study procedures were completed, i.e. when the performing endoscopists had obtained adequate mucosal views through water flushing. Evaluating the effect of different simethicone administration times on detection of dysplastic lesions in the upper gastrointestinal tract would require an extremely large sample size. Therefore, we used mucosal visibility as a surrogate endpoint. Finally, we did not evaluate the role of mucolytic agent N-acetylcysteine in addition to simethicone, because in most Western countries this is not typically used.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this randomized trial demonstrated that timing of small-volume simethicone as premedication in upper endoscopy is of particular importance for mucosal visibility. To optimize mucosal visibility in daily practice, simethicone can best be administered 20 to 30 minutes prior to upper endoscopy, either as a single administration or in a split-dose regimen.

Acknowledgement

We thank K. van der Meulen (nurse practitioner) and M. Poot (nurse practitioner) for their help recruiting study participants.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest B.L.A.M. Weusten is a consultant for Pentax Medical, has received a speaker’s fee from Pentax Medical and has received research funding from Aqua Medical and Pentax Medical. The remaining authors disclose no conflicts.

Supporting information

References

- 1.Beck M, Bringeland EA, Qvigstad G et al. Gastric cancers missed at upper endoscopy in central Norway 2007 to 2016 – a population-based study. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13:5628. doi: 10.3390/cancers13225628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Januszewicz W, Witczak K, Wieszczy P et al. Prevalence and risk factors of upper gastrointestinal cancers missed during endoscopy: A nationwide registry-based study. Endoscopy. 2022;54:653–660. doi: 10.1055/a-1675-4136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pimenta-Melo AR, Monteiro-Soares M, Libânio D et al. Missing rate for gastric cancer during upper gastrointestinal endoscopy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;28:1041–1049. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodríguez de Santiago E, Hernanz N, Marcos-Prieto HM et al. Rate of missed oesophageal cancer at routine endoscopy and survival outcomes: A multicentric cohort study. United European Gastroenterol J. 2019;7:189–198. doi: 10.1177/2050640618811477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Putten M, Johnston BT, Murray LJ et al. ‘Missed’ oesophageal adenocarcinoma and high-grade dysplasia in Barrett’s oesophagus patients: A large population-based study. United European Gastroenterol J. 2018;6:519–528. doi: 10.1177/2050640617737466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yalamarthi S, Witherspoon P, McCole D et al. Missed diagnoses in patients with upper gastrointestinal cancers. Endoscopy. 2004;36:874–879. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-825853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manfredi G, Pedaci M, Iiritano E et al. Impact of improved upper endoscopy quality on detection of gastric precancerous lesions. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;35:285–287. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000002513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Early DS, Lightdale JR, Vargo JJ et al. Guidelines for sedation and anesthesia in GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;87:327–337. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2017.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bisschops R, Areia M, Coron E et al. Performance measures for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy: A European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Quality Improvement Initiative. Endoscopy. 2016;48:843–864. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-113128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gotoda T, Uedo N, Yoshinaga S et al. Basic principles and practice of gastric cancer screening using high-definition white-light gastroscopy: Eyes can only see what the brain knows. Digestive Endoscopy. 2016;28:2–15. doi: 10.1111/den.12623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiu PWY, Uedo N, Singh R et al. An Asian consensus on standards of diagnostic upper endoscopy for neoplasia. Gut. 2019;68:186–197. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-317111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang WK, Yeh MK, Hsu HC et al. Efficacy of simethicone and N-acetylcysteine as premedication in improving visibility during upper endoscopy. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology (Australia) 2014;29:769–774. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elvas L, Areia M, Brito D et al. Premedication with simethicone and N-acetylcysteine in improving visibility during upper endoscopy: A double-blind randomized trial. Endoscopy. 2017;49:139–145. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-119034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Song M, Kwek ABE, Law NM et al. Efficacy of small-volume simethicone given at least 30 min before gastroscopy. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther. 2016;7:572–578. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v7.i4.572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krishnamurthy V, Joseph A, Venkataraman S et al. Simethicone and N-acetyl cysteine combination as premedication before esophagogastroduodenoscopy: Double-blind randomized controlled trial. Endosc Int Open. 2022;10:E585–E592. doi: 10.1055/a-1782-2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keeratichananont S, Sobhonslidsuk A, Kitiyakara T et al. The role of liquid simethicone in enhancing endoscopic visibility prior to esophagogastroduodenoscopy ( EGD): J Med Assoc Thai. 2010;93:892–897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahsan M, Babaei L, Gholamrezaei A et al. Simethicone for the preparation before esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Diagn Ther Endosc. 2011;2011:484532. doi: 10.1155/2011/484532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Asl SMKH, Sivandzadeh GR. Efficacy of premedication with activated Dimethicone or N-acetylcysteine in improving visibility during upper endoscopy. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4213–4217. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i37.4213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Banerjee B, Parker J, Waits W et al. Effectiveness of preprocedure simethicone drink in improving visibility during esophagogastroduodenoscopy: a double-blind, randomized study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1992;15:264–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Basford P, Brown J, Gadeke L et al. A randomized controlled trial of pre-procedure simethicone and N-acetylcysteine to improve mucosal visibility during gastroscopy – NICEVIS. Endosc Int Open. 2016;04:E1197–E1202. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-117631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mahawongkajit P, Kanlerd A. A prospective randomized controlled trial comparing simethicone, N-acetylcysteine, sodium bicarbonate and peppermint for visualization in upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Surg Endosc. 2021;35:303–308. doi: 10.1007/s00464-020-07397-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sajid MS, Rehman S, Chedgy F et al. Improving the mucosal visualization at gastroscopy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials reporting the role of Simethicone ± N-acetylcysteine. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;3:1–8. doi: 10.21037/tgh.2018.05.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bertoni G, Gumina C, Conigliaro R et al. Randomized placebo-controlled trial of oral liquid simethicone prior to upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Endoscopy. 1992;24:268–270. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1010479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blanco C, Barreto-Guevara MI, Walteros-Gordillo YL et al. Cohorts of premedication for endoscopy of the upper gastrointestinal tract with simethicone, n-acetylcysteine, hedera helix and visual scale validation. Rev Colomb Gastroenterol. 2021;36:39–50. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manfredi G, Bertè R, Iiritano E et al. Premedication with simethicone and N-acetylcysteine for improving mucosal visibility during upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in a Western population. Endosc Int Open. 2021;9:E190–E194. doi: 10.1055/a-1315-0114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Monrroy H, Vargas JI, Glasinovic E et al. Use of N-acetylcysteine plus simethicone to improve mucosal visibility during upper GI endoscopy: a double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;87:986–993. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2017.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 Statement: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ. 2010;340:698–702. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vickerstaff V, Omar RZ, Ambler G. Methods to adjust for multiple comparisons in the analysis and sample size calculation of randomised controlled trials with multiple primary outcomes. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2019;19:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12874-019-0754-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hommel G. A stagewise rejective multiple test procedure based on a modified Bonferroni test. Biometrika. 1988;75:383–386. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hassan C, East J, Radaelli F et al. Bowel preparation for colonoscopy: European society of gastrointestinal endoscopy (ESGE) guideline-update 2019. Endoscopy. 2019;51:775–794. doi: 10.1055/a-0959-0505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saltzman JR, Cash BD, Pasha SF et al. Bowel preparation before colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:781–794. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sun X, Xu Y, Zhang X et al. Simethicone administration improves gastric cleanness for esophagogastroduodenoscopy: a randomized clinical trial. Trials. 2021;22:4–10. doi: 10.1186/s13063-021-05527-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Woo JG, Kim TO, Kim HJ et al. Determination of the optimal time for premedication with pronase, dimethylpolysiloxane, and sodium bicarbonate for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;47:389–392. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3182758944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khan R, Gimpaya N, Vargas JI et al. The Toronto Upper Gastrointestinal Cleaning Score: a prospective validation study. Endoscopy. 2023;55:121–128. doi: 10.1055/a-1865-4180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.