Abstract

Sexual minority women (SMW; e.g., lesbian, bisexual) report higher rates of almost every negative physical health (e.g., asthma, arthritis, cardiovascular disease), mental health (e.g., depression, anxiety), and substance use outcome compared to heterosexual women. Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) have been identified as risk factors for negative health outcomes. Despite this, no study to date has synthesized existing literature examining ACEs and health outcomes among SMW. This gap is important because SMW are significantly more likely than heterosexual women to report every type of ACE and a higher total number of ACEs. Therefore, using a scoping review methodology, we sought to expand understanding of the relationship between ACEs and health outcomes among SMW. Using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for. Scoping Reviews protocol, we searched five databases: Web of Science, PsycInfo, CINAHL, PubMed, and Embase for studies published between January 2000 and June 2021 that examined mental health, physical health, and/or substance use risk factors and outcomes among adult cisgender SMW who report ACEs. Our search yielded 840 unique results. Studies were screened independently by two authors to determine eligibility, and 42 met full inclusion criteria. Our findings provide strong evidence that ACEs are an important risk factor for multiple negative mental health and substance use outcomes among SMW. However, findings were mixed with respect to some health risk behaviors and physical health outcomes among SMW, highlighting the need for future research to clarify these relationships.

Keywords: adverse childhood experiences, sexual minority women, physical health, mental health, substance use

Introduction

A rapidly growing body of literature documents substantial sexual orientation-related physical and mental health disparities. Compared to heterosexual women, sexual minority women (SMW; e.g., lesbian, bisexual, other non-heterosexual identity) are at higher risk of negative substance use and mental health issues. For example, they report higher rates of tobacco use (Caceres et al., 2019; Conron et al., 2010; Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2013; Matthews et al., 2014) and higher rates of almost every measure of alcohol misuse (e.g., alcohol dependence, heavy episodic drinking, intoxication) (Hughes et al., 2020). In an earlier systematic review, King and colleagues (2008) found that compared to heterosexual women, SMW had 3.42 times the risk of any substance use disorder (SUD), 3.50 times the risk of drug dependence, and 4.00 times the risk of alcohol dependence (King et al., 2008). These authors also found substantial mental health disparities. Specifically, SMW had 2.13 times the risk for past-12-month depression and 1.66 times the risk for past-12-month anxiety compared to their heterosexual counterparts (King et al., 2008). More recent reviews, such as those of Plöderl and Tremblay (2015) and Wittgens et al. (2022), have documented similarly large disparities between heterosexual and SMW’s outcomes. In addition, SMW have higher rates of many physical health conditions, such as asthma, arthritis, and cardiovascular disease (Caceres et al., 2017; Conron et al., 2010; Dilley et al., 2010; Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2012; Simoni et al., 2017; Veldhuis et al., 2019); body mass index of 25 or above (Caceres et al., 2019; Conron et al., 2010; Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2013; Simoni et al., 2017); higher hemoglobin A1C values (which increases risk of Type 2 diabetes) (Caceres et al., 2019); and poorer self-reported physical and mental health (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2012, 2013; Simoni et al., 2017; Wallace et al., 2011).

Disparities in SMW’s health are often attributed to sexual minority (SM) stress, which is the predominant theory of how stressors related to identifying as a SM (e.g., discrimination, stigma, internalized homophobia) contribute to negative health outcomes among SM people (Meyer, 2003). Further, preliminary research has documented that SMW who hold multiple marginalized identities and are exposed to multiple intersecting forms of oppression (e.g., racism, sexism, homophobia, xenophobia) (Crenshaw, 1990) are at even greater risk for poor health outcomes (Aranda et al., 2015; Balsam et al., 2011; Bowleg et al., 2003; Caceres et al., 2021; Li et al., 2015; Ramirez & Paz Galupo, 2019; Veldhuis et al., 2020).

Although SM stress is the most commonly cited explanation for SMW’s heightened risk, it does not fully account for sexual orientation-related health disparities. Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs, e.g., childhood sexual abuse [CSA], childhood physical abuse [CPA], childhood poverty, incarceration of a family member, witnessing violence) have been identified as key risk factors in the development of negative health outcomes among people in the general population. For example, studies across diverse samples of adults in the general population have found that ACEs are associated with myriad negative physical health, mental health, and substance use outcomes (Iniguez & Stankowski, 2016; Mersky et al., 2013; Monnat & Chandler, 2015). In one U.S. national sample, ACEs were associated with poor self-rated health, functional limitations, diabetes, and heart attack as adults (Monnat & Chandler, 2015). In a large, regional sample of adults, there was a dose-response relationship between the number of ACEs and moderate to heavy drinking, drug use, depressed affect, and suicide attempts (Merrick et al., 2017).

However, far fewer studies have examined the relationship between ACEs and negative health outcomes among SMW. This gap is important because SMW appear to be more likely than heterosexual women to report several ACEs, including CPA, CSA, neglect, household dysfunction, and bullying (Alvy et al., 2013; Austin et al., 2008a; Friedman et al., 2011; Giano et al., 2020; McCabe et al., 2020a, 2020b; Merrick et al., 2018; Wilsnack et al., 2008; Zou & Andersen, 2015). For example, in a national sample of U.S. adults, reports of CPA were highest among lesbian (45.5%) and bisexual (47.5%) women, and women unsure of their sexual identity (51.6%), compared to 32.9% of heterosexual women (McCabe et al., 2020b). Additionally, there is some evidence that SMW experience a greater number of types of ACEs (Austin et al., 2008a, 2020b; Zou & Andersen, 2015) and more severe forms of childhood victimization than heterosexual women (Alvy et al., 2013; Wilsnack et al., 2012). Specifically, in one recent study, McCabe et al. (2020b) found that lesbian and bisexual women consistently reported significantly higher numbers of ACEs compared to heterosexual women, with lesbian and bisexual women reporting an average of 2.8 (95% CI [2.5, 3.1]) and 3.3 (95% CI [2.9, 3.6]) compared to heterosexual women, who reported an average of 2.1 (2.0–2.1) ACEs. With respect to severity of ACEs, Alvy and colleagues (2013) found that compared to heterosexual women, SMW reported more severe forms of CPA (e.g., being beaten, punched, or choked) and Wilsnack and colleagues (2012) found that they reported more severe forms of CSA (e.g., earlier age of onset, greater frequency, longer duration). While few studies to date have examined factors contributing to SMW’s increased risk of ACEs, preliminary research suggests that SMW may be more likely to engage in gender non-conforming behaviors or expression which may, in turn, place them at greater risk for ACEs (Lehavot & Simoni, 2014; Roberts et al., 2005; Rosario et al., 2022). However, there is no consensus of opinion on why SMW report higher rates of ACEs compared to heterosexual women, highlighting a need for future research in this area.

Despite the growing number of studies focusing on ACES among SMW, to our knowledge, there have been no reviews summarizing the current state of the literature on ACEs and health outcomes among SMW—a necessary step toward a greater understanding of SMW’s heightened risk of negative health outcomes and the development of targeted prevention and/or intervention strategies. Therefore, we conducted a scoping review guided by the following research question: “What is the current state of knowledge about the links between ACEs and mental health, physical health, and substance use among SMW?” We also aimed to identify gaps and weaknesses in the existing literature to guide future research and to support recommendations for research, policy, and practice to address sexual orientation-related health disparities among women.

Methods

Protocol and Eligibility Criteria

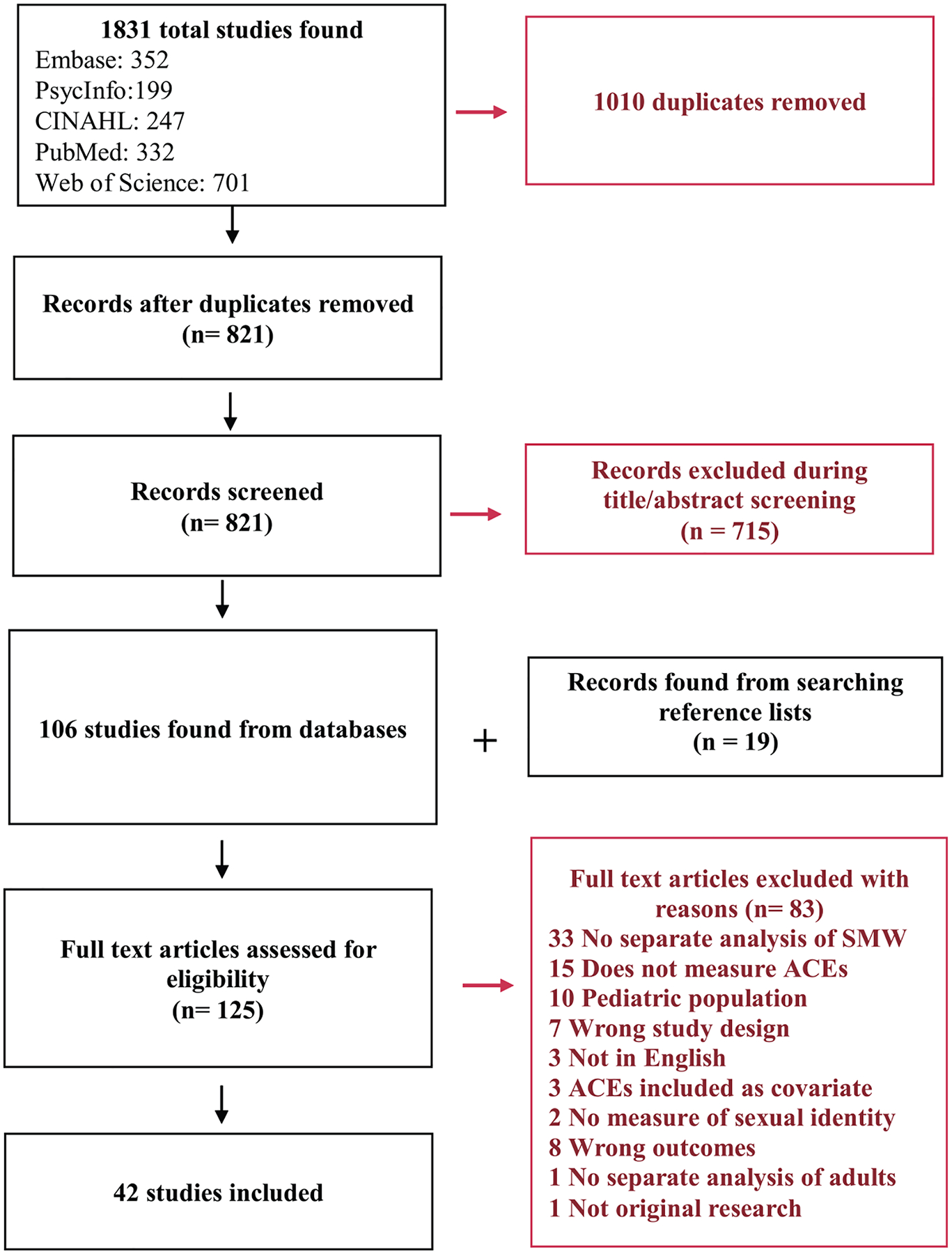

Following the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) guidelines for conducting scoping reviews (Peters et al., 2020), we developed a protocol (available upon request from the corresponding author) to screen articles for study inclusion (see Figure 1). Inclusion criteria included empirical, quantitative, or mixed methods peer-reviewed studies published in English between January 2000 and June 2021 examining mental health, physical health, and/or substance use risk factors and outcomes among adult (ages 18 or older) cisgender SMW who report ACEs. We selected 2000 as the beginning year of study inclusion given that the U.S. Institute of Medicine released its landmark report focused on lesbian health research 1 year earlier (Solarz, 1999), which resulted in substantial growth of research focused on SM women’s health. We included studies of women who identified as lesbian, bisexual, mostly heterosexual, or another non-heterosexual identity (we did not include studies that assessed only sexual attraction and/or behavior). We only included studies that used identity to measure minority sexual orientation (rather than sexual attraction or behavior) as minority-specific stress has been shown to be most strongly and consistently associated with identification as a SM, rather than attraction or behavior (Krueger et al., 2018). Studies that included both SM individuals who were younger and older than age 18 or included sexual minority men (SMM), but reported outcomes for adult SMW separately, were eligible for inclusion. Studies that focused exclusively on transgender or nonbinary individuals were excluded unless the study also assessed and reported on sexual identity. Additionally, studies were excluded if they did not assess ACEs, or if ACEs were included as a covariate, not a primary exposure variable.

Figure 1.

PRISMA-ScR table.

In July 2021, we searched five databases (Web of Science, PsycInfo, CINAHL, PubMed, and Embase). Table 1 shows the search terms used across databases (slight modifications were made to the organization of the search query to meet requirements of individual databases). Our search resulted in 1,831 references. Duplicate references were removed using Covidence, an online systematic review manager, resulting in 821 unique references. Next, two authors independently conducted a title/abstract screening and removed studies that did not meet eligibility criteria. At this stage, there was approximately 92% agreement between authors. We then examined the reference lists of each article meeting inclusion criteria to identify additional articles, resulting in 19 additional studies. We screened 125 studies for eligibility via full-text review. In the full-text review stage, there was 83% agreement between authors. A third researcher resolved discrepancies in inclusion/exclusion decisions during the abstract and full-text screening stage. We removed an additional 84 studies during full-text screening, leaving 42 for the final review. Reasons for exclusion during the full-text review stage included: study results aggregated across groups (e.g., sexual identity groups, age groups, or SMW and SMM) and ACEs not explicitly or separately measured (e.g., included only a lifetime trauma variable).

Table 1.

Search Terms.

| Concept | Search Terms |

|---|---|

| Adverse childhood experiences | (neglect OR “household dysfunction” OR “incarcerated relative” OR “incarcerated family member” OR “parental criminal behavior” OR “parental incarceration” OR “emotional abuse” OR “physical abuse” OR “childhood physical abuse” OR “physical punishment” OR “emotional maltreatment” OR “physical trauma” OR “family violence” OR “abused child” OR “child endangerment” OR “psychological abuse” OR “household mental illness” OR “parental mental disorder” OR “household alcohol and drug abuse” OR “parent* alcoholism” OR divorce OR “parent* separation” OR “toxic stress” OR “verbal abuse” OR CPA or “domestic violence” OR “intimate partner violence” OR “child sexual abuse” OR csa OR “sexual abuse” OR “sex abuse” OR “intrafamilial sexual abuse” OR “extrafamilial sexual abuse” OR “child sexual victimization” OR polyvictimization OR “child* sexual maltreatment” OR “child* physical maltreatment” OR “child* emotional maltreatment” OR “child* maltreatment” OR “child* trauma” OR “child* sexual maltreatment” OR molestation OR incest OR “child abuse” OR “child* sexual abuse” OR “child* sexual victimization” OR “child sexual assault” OR “adverse childhood experience* OR ACEs” OR “child* adversity” OR “adverse childhood events”) |

| Sexual minority women | (“sexual AND gender minorities” OR “sexual minority” OR “sexual minorities” OR lesbian* OR queer* OR pansexual* OR asexual* OR lgbt OR lgb* OR lgbtq OR lgbtqia OR “GLB” OR “homosexual female” OR “homosexual females” OR “homosexual women” OR “homosexual woman” OR “female homosexuality” OR “same-sex relationships” OR “same-sex female relationships” OR “mostly heterosexual women” OR “sexual orientation” OR “queer women” OR “bisexual female”) |

| Physical health | (“health outcome*” OR “physical health” OR “sleep problem” OR asthma OR “sleep disorder,” “cardiovascular disease” OR obesity OR “sleep disturbance” OR hypertension OR morbidity OR “allostatic load” OR cancer OR disease OR death OR injury OR pain OR headache OR weight OR “somatic complaints” OR “chronic pain” OR “immune functioning” OR “respiratory illness” OR accidents OR “traumatic brain injury” OR diabetes OR “health status” OR “health status indicators” OR symptoms OR headache* OR epilepsy OR migraine OR “coronary heart disease,” stroke OR “gallbladder disease” OR osteoarthritis OR “sleep apnea” OR “respiratory problems” OR dyslipidemia OR tobacco OR AIDS OR HIV OR diet OR nutrition OR nicotine OR “kidney disease” OR STI OR “sexually transmitted infection” OR “sexually transmitted disease” OR STD OR fatigue OR gastrointest* OR “heart failure”) |

| Mental health/substance use | (“mental health problems” OR “psychological distress” OR “mental disorder*” OR “mental health outcomes” OR “mental health” OR “mental illness*” OR emotional problems OR anxiety OR depress* OR psycho* OR psychiat* OR suicide* OR “self-harm” OR NSSI OR “non-suicidal self-injurious behavior” OR “post-traumatic stress disorder” OR GAD or bipolar OR manic OR MDD or PTSD OR “substance use” OR “substance misuse” OR “substance-related disorder*” OR “drug OR addiction*” OR alcohol* OR “substance abuse” OR “illicit drug*” OR “illegal drug” OR cannab* OR hemp OR weed OR THC OR marijuana OR smok* OR amphetamine* OR meth OR methamphetamine* OR “crystal meth” OR ice OR ecstasy OR MDMA OR molly OR cocaine OR crack OR opiate* OR opioid* OR LSD OR “lysergic acid diethylamide” OR hallucinogen* OR inhalant* OR heroin OR ketamine) |

Data Extraction, Analysis, and Synthesis

Using JBI methodology (Peters et al., 2020), we charted the data using a data extraction form developed by the full team of authors. Each author conducted data charting independently; however, all studies were reviewed in duplicate to ensure internal consistency in review procedures. For each study, we charted the following: study design, sample size, participant demographics, dependent variable(s), independent variable(s), and main outcomes. Data were then summarized by major themes and gaps in the literature were identified.

Results

Description of Included Studies

Table 2 provides an overview of the included studies (e.g., sample characteristics, study design). The range of sample sizes of the included studies was 85 to 36,309, with a median of 703 and a mean of 5,273. Twenty-two studies included heterosexual comparison groups, and the remainder included only sexual minorities in their samples. Of the 42 included articles, 11 focused exclusively on mental health outcomes, 13 on alcohol and/or other substance use, 13 on physical health outcomes, two on revictimization and other experiences of violence, two focused on both mental health and alcohol use, one focused on mental and physical health, and one examined financial health (defined as having the economic resources to meet one’s basic physical needs). Thirty-seven studies used cross-sectional and four used longitudinal designs. Two of the studies employed mixed methods and the remainder used solely quantitative methods. Most (n = 39) studies were conducted in the U.S. Three studies were conducted outside of the U.S., one included participants from both the U.S. and Canada (Crump & Byers, 2017), another was based exclusively in Canada (Persson et al., 2015), and the third in Australia (Zietsch et al., 2012).

Table 2.

Overview of Study Design and Sample Characteristics.

| Author | Location, Design, and Sample Type | ACE Measure (Validated, Single Item, etc.) | Hetero Comparison Group | Sample Size (n) | Age (Range, Mean, Standard Deviation) | Sexual Identity | Race/Ethnicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andrés-Hyman et al. (2004) | U.S. cross-sectional, non-probability | CSA: validated measure (structured clinical interview) | Yes | 257 | Range: 17–58, M: 32.13, SD: 9.16 | Asexual: 3.4%, Bisexual: 3.1%, Lesbian: 7.4%, Heterosexual: 82.5%, Uncertain: 2.3% | Black: 7.4%, White: 77%, Latinx: 10.2%, Other: 5.5% |

| Flynn et al. (2016) | U.S., cross-sectional, probability | CPA, CSA, CN: 1 item for each | Yes | 34,175 | Men—SM: M: 45.5, (0.94SE), heterosexual: M: 47.3 (0.20), Women—SM:M: 39.0 (0.81), heterosexual: M: 49.1 (0.20) | Men: SM: 0.8%, Heterosexual: 41.3%, Women—SM: 0.9%, Heterosexual: 57% | White men—SM: 75.1% heterosexual: 71.3% Non-white men SM: 25%, heterosexual: 28.7% White Women—SM: 69.7%, heterosexual: 70.8%, Non-White women—SM: 30.3% heterosexual: 29.3% |

| Gold et al. (2011) | U.S. cross-sectional, non-probability | CPA: validated measure LEQ (Long, 1999) | No | 237 | Range: 16–77, M: 33.56, SD: 12.47 | Lesbian: 51.5%, gay men: 48.5% | Black: 9%, White: 71%, Latinx: 8%, Asian: 3%, Native American: 1%, Mixed: 2%, Other: 6% |

| Lehavot et al. (2014) | U.S. cross-sectional, non-probability | CEA, CPA, CSA, EN and PN validated measure CTQ (Bernstein et al., 1998) | Yes | 699 | M: 49.74, SD: 14.04 | Lesbian: 29% Bisexual: 8%, Heterosexual: 63% | Black: 3.9%, White: 85%, Latinx: 4.6%, Other: 6.5% |

| Lehavot and Simpson (2014) | U.S. cross-sectional, non-probability | CEA, CPA, CSA, EN and PN validated measure CTQ (Bernstein et al., 1998) | Yes | 706 | M: 47.32, SD: 13.76 (for SM sub-sample) | 37% lesbian or bisexual | Black: 3%, White: 82%, Latinx: 6%, Other: 9% |

| Matthews et al. (2002) | U.S. cross-sectional, non-probability | CSA: 1 item w/follow up question | Yes | 829 | M: 43 years, SD: 10.8 | Lesbian: 66.3% Heterosexual: 33.7% | Black: 14.2%, White: 74.5%, Other: 10.4% |

| Zietsch et al. (2012) | Australia, cross-sectional twin study, non-probability | Risky family environment: 5 items, CSA: 4 items, CPA: 3 items, not validated | Yes | 9,884 | Sample 1: Range: 23–39, M: 29.9, SD: 2.5, Sample 2: Range: 27–37, M: 31.8, SD: 2.5 | 3.3% of women in the sample were “non-heterosexual” | not reported |

| Persson et al. (2015) | Canada, cross-sectional, non-probability | CSA, CPA, and CEA: litem w/follow up question | Yes | 388 women | Range: I8–66,M: 24.40, SD: 6.40 | Heterosexual: 48.5% mostly heterosexual: 13.7%, bisexual: 16.5% mostly lesbian: 0.08% lesbian: 13.1% | English Canadian 63%, French Canadian 13%, Other: 24% |

| Sigurvinsdottir and Ullman (2016) | U.S. longitudinal, non-probability | CSA: validated measure (modified version of the SES [Koss & Gidycz, 1985]) | Yes | 905 | Range: 18–71, M bisexual: 35.05, M heterosexual: 40.35 | Heterosexual: 810 Bisexual: 95 |

Black: 47%, White: 35%, Asian: 2% Other: 10%, Multiracial: 6%, Latinx: 13% |

| Morris and Balsam (2003) | U.S., cross-sectional, non-probability | CSA: 4 items, not validated | No | 2,431 | Range: 15–83, M: 36 | Sexual orientation ranges from 0 (only lesbian) to 100 (only heterosexual) 0: 44%, 1–10: 18%, 11–20: 8%, 21–50: 26%, 51–100: 3% | Black: 10%, White: 75%, Latinx: 7% American Indian: 4%, AAPI: 3%, Other or no response: 2% |

| Robohm et al. (2003) | U.S., cross-sectional, mixed methods, non-probability | CSA: 1 item w/follow up question | No | 227 | M: 20.30 years SD: 1.73, Range: 18–23 | All identified as LGB | White: 80.2%, People of Color: 19.8% |

| Roberts et al. (2005) | U.S., cross-sectional, non-probability | CSA: measure not described | No | 1,139 | No M/SD, 15–24: 12%, 25–34: 27% 35–44: 31%, 45–54: 21%, 55+: 9% | 100% lesbian | Black: 4%, White: 74%, Multi/other: 16%, Jewish: 3%, Latin: 2%, AAPI: 0.4%, Native American: 0.4% |

| Wilsnack et al. (2008) | U.S., cross-sectional, non-probability | CSA using criteria developed by Wyatt (1985) and Vogeltanz et al. (1999) | Yes | 953 | Range: 21–70 | 42.5% SMW, 57.5% Heterosexual | 68.8% White in NSHLEW, 51.3% White in CHLEW (no other race/ethnicity info reported) |

| Hughes et al. (2007) | U.S., cross-sectional, non-probability | CSA: 1 item, CPA: 1 item w/follow up question | No | 447 | M: 37.5, Range: 18–83 | Bisexual: 2.5%, Lesbian: 97.1%, Queer: 0.22%, Refused: 0.22% | 28% Black, 47% White, 20% Latinx 5% AAPI, Native American, or multiracial |

| Hughes et al. (2001) | U.S., mixed methods, cross-sectional, non-probability | CSA: 1. 8-Item measure w/follow-up, categorized according to Wyatt (1985) 2. 1 Item of self-perceived CSA; 3. Number of CSA experiences | Yes | 120 women | M: 40 years | Lesbian: 52.5% Heterosexual: 47.5% | Heterosexual-Black: 28%, White: 39%, Latinx: 23%, Other: 11%, Lesbian—Black: 27%, White: 37%, Latinx: 27%, Other: 10% |

| Hughes et al. (2014) | U.S., cross-sectional, non-probability | CSA: 8-item measure with follow-up, categorized according to Wyatt (1985), CPA: 1 item w/follow up question, PN: 1 item | Yes | 1573 | Range: 18–94, M: 45.18, SD: 1.21 | Only heterosexual: 64.4% mostly heterosexual: 4.6% bisexual: 1.7%, mostly lesbian: 7.9%, Lesbian: 20.7% | Black: 20%, White: 65.3%, Latinx: 11.6%, Other: 3.1% |

| Johnson et al. (2013) | U.S., longitudinal, non-probability | Parental drinking problems: 1 item CSA: 1 item, self-perceived CSA | No | 447 | Range: 18–83, M: 37.5 SD: 11.7 | 100% lesbian | Black: 28%, White 47%, Latinx: 20% AAPI, Native American, or multiracial 5% |

| Reisner et al. (2013) | U.S., cross-sectional, non-probability | Any CA: 1 item | Yes | 2,653 | Range: 18–71, M: 31.7; (total sample at the clinic, including participants who are not in the study sample) | Males—gay: 59.9%, bisexual: 4.3% other SMM: 5.2%, heterosexual: 30.6% Females—lesbians: 27.1%, bisexual 7.9%, other SMW: 7.2%, heterosexual: 57.9% | Black—Males: 5.2%, Females: 7.3%, White—Males: 81.3%, Females: 73.0%, Latinx—Males: 6.3%, Females: 6.1%, Other—Males: 7.2%, Females: 13.7% |

| Drabble et al. (2013) | U.S., cross-sectional, probability | CSA: 1 item (Sorenson et al., 1987) CPA: 1 item derived from the CTS (Strauss, 1990) | Yes | 11,169 | M only heterosexual: 45.8, heterosexual w/same-sex partners: 40.6, bisexual: 33.6, lesbian: 40.3 | Only heterosexual: 96% heterosexual w/same-sex partners: 1.6%, bisexual: 1.3%, Lesbian: 1.1% | Not reported |

| Hequembourg et al. (2013) | U.S., cross-sectional, non-probability | CSA: 6 items validated (Finkelhor & Browne, 1985; Miller et al., 1993) | No | 205 | Range: 18–35, M: 24.5, SD: 4.4 | Lesbian: 47.8%, Bisexual: 52.2% | Black: 21.0%, White: 65.9%, Latinx: 4.9% |

| Gilmore et al. (2014) | U.S., cross-sectional, non-probability | CSA: 2 items from the TLEQ (Kubany et al., 2000) | No | 4,119 | Range: 18–25, M: 20.88 (SD: 2.11) | Bisexual: 49.9%, lesbian: 36.3%, queer: 6.2%, questioning: 2.3%, other: 4.8% | Black: 12.4%, White: 70.5%, Asian; 3.5% Multiracial: 7.5%, Other: 6.1% |

| Talley et al. (2016) | U.S., cross-sectional, non-probability | CSA: 1, CPA: 1 w/follow up question | Yes | 332 | Range: 18–30, M: 20.88, SD = 2.86 | Only heterosexual: 61.1%, mostly heterosexual: 21.4%, bisexual: 6.6%, mostly lesbian: 3.0%, only lesbian: 7.8% | 11% Black, ~84% White, 5% Asian 5% Latinx |

| Yuan et al. (2014) | U.S. cross-sectional, non-probability | CPA, CSA, PN, CEA: validated measure (CTQ short form) | No | 294 | Men M: 37.97 (SD 10.54, range: 20–63) women M: 38.98 (SD 10.42, range: 18–62) | 100% of participants identified as two spirit | 100% American Indian or Alaska Native |

| McCabe et al. (2020a) | U.S., cross-sectional, probability | Household dysfunction: 6 items, not validated | Yes | 36,309 | No M/SD, four age groups: 18–29, 30–44, 45–64, <65 | Heterosexual (96%−97%), 3.0% of men and 3.6% of women identified as aSM | White, Black, Latinx, other (did not report percentages) |

| T. Hughes et al. (2010a) | U.S., cross-sectional, non-probability | CSA: 1 item w/follow up question, CN: 1 item CPA: 1 item | Yes | 34,653 | No M/SD, 20–24: 7.6%, 25–44: 38.5%, 45–64: 34.6%, <65: 19.3% | 0.85% lesbian/gay, 0.62% bisexual, 0.46% unsure | 29% POC (71% White, 11% Black, 4% Asian, 12% Latinx, 2% Native American) |

| Hughes et al. (2010b) | U.S., cross-sectional, non-probability | CSA: 8-item measure with three follow-up questions based on Wyatt (1985) | Yes | 502 | Range: 21–79 | Only heterosexual: 52.7%, mostly heterosexual: 3.4%, bisexual: 1.7%, mostly lesbian: 10.5% only lesbian: 31.8% | Not reported |

| Aaron and Hughes (2007) | U.S., cross-sectional, non-probability | CSA: 1 item of self-perceived CSA | No | 416 | 18–83, <30: 30.8%, 31–40: 28.8%, 41–50: 23.1%, >51: 17.3% | 100% lesbian | White: 50%, Black: 29%, Latinx: 21 % |

| Lee et al. (2020) | U.S., cross-sectional, probability | 4 ACEs: food insecurity, drugs, CPA, and CEA (Felitti et al., 1998) | No | 453 | 18–24: 25.2%, 25–44: 49.0%, 45–64: 22.5%, <65: 3.3% | Heterosexual 0.4% lesbian or gay 59.8% bisexual 38.9%, not specified: 0.9% | White 67.5% Black: 20.8% American Indian or Alaska Native: 1.3%, Asian 2.0%, Pacific Islander: 0.2%, Other: 8.2% |

| Smith et al. (2010) | U.S., cross-sectional, non-probability | CSA: 2 items, not previously validated | Yes | 867 | Heterosexual: 35–64, M: 47.9 (±7.6), Lesbian: M: 47.4 (±7.1) | heterosexual (45.2%), lesbian (54.8%) | 92% white, 8% Black |

| Matthews et al. (2013) | U.S., cross-sectional, non-probability | CPA: 1 item w/follow up question | No | 328 | M: 37.4 | 70.1% lesbian, 26.8% mostly lesbian, 3.1 % bisexual | Black: 25.6% White: 55.5% Latinx: 18.9% |

| Sweet and Welles (2012) | U.S., cross-sectional, probability | Frequency of CSA, not previously validated | Yes | Women 19,605 Men 14,297 |

Women—20–30: 17.4% 31–40: 18.7% 41–50: 20.9% 51–60: 17%, 60+: 26% Men −20–30: 19% 31–40: 19.8%, 41–50: 21.8%, 51–60: 17.2%, 60+: 21.8% |

Women: lesbian: 0.6%, bisexual: 0.8%, heterosexual w same-sex partners 1.5%, heterosexual w same sex attraction: 4.6%, only heterosexual: 92.5% Men: gay: 1.1%, bisexual: 0.4%, heterosexual w same-sex partners: 2.4%, heterosexual w same-sex attraction: 1.8%, only heterosexual: 94.3% | Women-Black: 12.0%, Native American: 2.3%, AAPI: 4.1%, Latinx: 10.9% White: 70.7%, Men—Black: 10.0%, Native American: 2.0%, AAPI: 4.3%, Latinx: 12.3%, White: 71.4% |

| Caceres et al. (2019) | U.S., cross-sectional, non-probability | CA- CPA: 1 item, CSA: 8 items (Wyatt, 1985), PN: 1 item | No | 547 | Range: 18–75, mean not reported | Lesbian: 59%, bisexual: 25%, Mostly lesbian: 16% | White: 38.6%, Black: 35.8%, Latina 21.9%, Other: 3.7% |

| Wright (2018) | U.S., cross-sectional, non-probability | CSA: 1 item (Prevent Child Abuse America, 2013) | No | 85 | M: 28.3 (SD: 7.29) Range not reported | Lesbian: 57.6%, gay: 1.2%, bisexual: 29.4% queer: 3.7%, same sex attracted: 4.7%, other 2.4% | White: 81.2%, Black: 9.4%, latinx: 2.4%, biracial: 4.7%, other: 2.4% |

| Crump and Byers (2017) | Canada and U.S., cross-sectional, non-probability | CSA: 1. Fondling but no attempted or completed penetration and 2. Attempted or completed penetration; based on the CSAQ (Lemieux & Byers, 2008) | No | 299 | 18–57 M: 28.40 SD: 9.20 | Lesbian: 55.2%, Bisexual: 13.7%, Queer/unlabeled: 31.1% | White: 82.21%), Other 53 (17.79%) |

| Katz-Wise et al. (2014) | U.S., longitudinal, non-probability | CSA: 2 items from the SES (Koss & Gidycz, 1985) CPA: 4 from the CTS (Straus, 1979), CEA: 2 from the CAQ Witnessing physical or verbal abuse: 2 items not validated | Yes | 13,952 | Data were included from 9 waves—in the first wave, participants were 12–14 years, in the last wave, participants were 20–25 years. | For women, 80.7% completely heterosexual, 15.9% mostly heterosexual, 2.1 % bisexual, and 1.3% lesbian/gay | Women: 93% white, Non-white: 7% |

| Sweet et al. (2013) | U.S., longitudinal, probability | Frequency of CSA (based on 4 items, not validated) | Yes | 33,902 | Age for the full sample is not reported | Sexual identity not reported for full sample. 2.9% of SMW reported past year HIV/STI | Race/ethnicity is not reported for the full sample |

| Lehavot and Simoni (2011) | U.S., cross-sectional, non-probability | CEA, CPA, and CSA, and EN and PN from the CTQ (Bernstein et al., 1998) | No | 1,224 | Range: 18–86 M: 33.77, SD: 12.24 | Lesbian: 45%, gay: 5%, bisexual: 29%, queer: 17%, two-spirit: 2%, other: 3% | 6% Black, 76% white, 4% Latinx, 4% Asian, 1% American Indian, 9% multiracial, 1% other |

| Greene et al. (2019) | U.S., cross-sectional, non-probability | CSA measure not described | No | 691 | Split by screening status Received screening 43.4 ± 14.5, Did not receive screening 39.2 ± 12.6 |

Received screening—lesbian: 32.9% bisexual: 7.7%, other: 2.8%, Did not receive screening—lesbian: 37.3%, bisexual: 15.1% other: 4.3% | Received screening—Black: 13.5%, White: 19.5% Latinx: 8.5% Other: 1.7% Did not receive screening—White: 18.4% Black: 22.1%, Latinx: 14.0%, Other: 2.2% |

| Andersen et al. (2014) | U.S., cross-sectional, non-probability | CA: CSA: number of items not reported, categorized according to Wyatt (1985) CPA: 1 item follow up | Yes | 940 women | Range: 21–70, only heterosexual: 38.3 (12.74), lesbian: (10.67), mostly heterosexual: 34.93 (14.43), bisexual: 30.05 (7.67) | Only heterosexual: 51.2%, Mostly heterosexual: 4.5%, Bisexual: 1.2%, Lesbian: 41.9%, Bisexual: 1.2% | Black: 21.2%, White: 60.7%, AAPI: 2.0%, Latinx: 13.4% Native American: 0.4%, Other: 2.4% |

| Hyman (2000) | U.S., cross-sectional, non-probability | CSA: 2 items, each with three follow-up questions, not validated | No | 1,889 | Range: 22–80 80% between 25 and 44 |

All participants identified as lesbians | White: 88%, Black: 6%, Latinx: 4%, small numbers identified as Native and Asian but numbers not reported |

| Austin et al. (2008b) | U.S., cross-sectional, probability sample | CSA: number items not reported, adapted from (Leserman, 2005) | Yes | 391 women | Range: 18–24 M: 21 | Mostly heterosexual: 42%, only heterosexual: 30% bisexual: 15%, mostly lesbian: 9%, only lesbian: 3% | Latinx: 47%, Black: 37%, White: 15%, Other: 1% |

| Han et al. (2013) | U.S., cross-sectional, non-probability | CSA: LEQ (Long, 1999) | No | 239 | Range: 16–77, M: 33.56years SD: 12.47 | Lesbian: 51 %, gay men: 49% | Black: 8.5%, White: 64.8% Latinx: 7.7% Asian: 2.8%, Native American: 1.2%, Mixed: 1.6%, Other: 5.3% |

Note. AAPI = Asian American and Pacific Islanders; ACE = Adverse Childhood Experience; CA = Child abuse; CAQ = Childhood Abuse Questionnaire; CEA = Childhood Emotional Abuse; CN = Childhood Neglect; CPA = Child Physical Abuse; CSA = Childhood Sexual Abuse; EN = Emotional Neglect; PN = Physical Neglect; LGB = lesbian, gay, bisexual; LEQ = Life Experiences Questionnaire; CSAQ = Childhood Sexual Abuse Questionnaire; CTQ = CT Questionnaire; CTS = Conflict Tactics Scale; POC: People of Color.

Some studies used validated scales to measure exposure to ACEs; five used batteries of questions from Wyatt’s (1985) revised Wyatt Sex History Questionnaire (Aaron & Hughes, 2007; Hughes et al., 2001, 2007, 2010b; Wilsnack et al., 2008), four used Bernstein and colleagues (1998) full or shortened Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (Katz-Wise et al., 2014; Lehavot et al., 2014; Lehavot & Simpson, 2014; Yuan et al., 2014), one study used CSA questions from Long (1999)’s Life Experiences Questionnaire (Gold et al., 2011), another used Kubany et al.’s (2000) Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire (Gilmore et al., 2014), one used the Conflict Tactics Scale developed by Strauss (1990) (Drabble et al., 2013), and another Koss and Gidycz’s (1985) Sexual Experiences Survey (Sigurvinsdottir & Ullman, 2016). The majority of studies used a single question or a set of investigator- or clinician-developed questions regarding specific ACEs, some of which were adapted from validated scales. One study did not specify how exposure to ACEs was measured (Greene et al., 2019).

A range of theoretical frameworks guided the studies (see Table 3). Researchers used Minority Stress Theory as a guiding framework in 15 of the studies (Caceres et al., 2019; Drabble et al., 2013; Flynn et al., 2016; Hequembourg et al., 2013; T. L. Hughes et al., 2001; T. L. Hughes et al., 2014; T. Hughes et al., 2010a; T. L. Hughes et al., 2010b; Katz-Wise et al., 2014; Lehavot & Simpson, 2014; McCabe et al., 2020a; Persson et al., 2015; Sigurvinsdottir & Ullman, 2016; Wilsnack et al., 2008; Wright, 2018), and four studies used Self-Medication Hypothesis (Gilmore et al., 2014; Johnson et al., 2013; Lehavot et al., 2014; Talley et al., 2016). The following theories or frameworks were each used in one study: Emotional Processing Theory (Gold et al., 2011), the Traumagenic Dynamics Model (Crump & Byers, 2017), traumatic sexualization (Robohm et al., 2003), which is part of the Traumagenic Dynamics model, the Social Norms Approach to Drinking (Gilmore et al., 2014), Intersectionality Theory (Greene et al., 2019), common cause explanations (Zietsch et al., 2012), protective measures theory (Smith et al., 2010), life course (Reisner et al., 2013), and socialization and human capital formulations of financial earnings (Hyman, 2000). However, 15 of the included studies did not explicitly mention a theoretical framework (Aaron & Hughes, 2007; Andersen et al., 2014; Andrés-Hyman et al., 2004; Austin et al., 2008b; Han et al., 2013; Hughes et al., 2007; Lehavot & Simoni, 2011; Matthews et al., 2002, 2013; Morris & Balsam, 2003; Roberts et al., 2005; Sweet & Welles, 2012; Sweet et al., 2013; Yuan et al., 2014).

Table 3.

Theoretical Frameworks, Prevalence of Abuse, and Study Outcomes.

| Author | Theoretical Framework | Independent Variable | Dependent Variable | Prevalence of Abuse | Main Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental Health | |||||

| Andrés-Hyman et al. (2004) | None specified | Demographic variables (e.g., education) | PTSD symptoms | CSA: 100% of participants (a criteria for admission to treatment program where participants were recruited) | Asexual women recognized the least number of intrusive and total PTSD symptoms compared to heterosexual, lesbian, and bisexual subgroups. Compared to non-Latinx Caucasian women, Latinx women recognized fewer intrusive PTSD symptoms. |

| Flynn et al. (2016) | Minority stress (Meyer, 2003) | CSA, CPA, CN | Attempted suicide | CSA: SM women: 37%, heterosexual:10.3%, CPA: SM women 11.1%, heterosexual: 3.9%, CN: SM women 10.4%, heterosexual: 3.4% | For men and women, CSA mediated the relationship between LGB identity and attempted suicide. For women only, CPA also mediated this relationship. |

| Gold et al. (2011) | Emotional processing theory (Foa & Riggs, 1993; Foa & Rothbaum, 2001) | CPA | Depression, PTSD, EA, IH | Lesbian: CPA 26.2% CSA 26.2% | Compared to gay men, lesbians were significantly more likely to recognize CPA. Lesbians reporting CPA were also more likely to report lifetime sexual victimization than those who did not (chi square p < .05). Lesbian CPA survivors reported more symptoms of depression (t test p < .05), greater PTSD symptoms (t test p < .001), and greater EA (t test p < .01) than those who did not report CPA. However, lesbian CPA survivors did not differ from nonvictims on measures of IH. In lesbians, CPA was not associated with IH nor was IH found to mediate the relationship between CPA and depression or PTSD. CPA and EA predicted depression when entered individually in the regression analysis. However, when entered together, CPA no longer predicted depression, whereas EA remained significant, suggesting complete mediation. When examining PTSD, both CPA and EA predicted PTSD when entered in the regression individually and when entered together. When examining CPA through EA, the indirect effect was between 0.67 and 4.50 (95% CI), significant with p < .05. |

| Gilmore et al. (2014) | Social norms approach to drinking and self-medication hypothesis | CSA severity | Drinking norms and behavior, ASA | CSA without penetration: 16.20% CSA with penetration: 22.00% | Higher CSA severity was associated with more severe alcohol-involved adult sexual assault and with more severe physically forced adult sexual assault. Higher CSA severity had an indirect relationship with higher drinking behaviors and higher drinking norms. Higher alcohol-involved ASA severity was associated with higher drinking norms and behavior. |

| Hughes et al. (2007) | None specified | CSA, CPA, parental drinking problems, parental strictness | Lifetime alcohol abuse, psychological distress (via age at first heterosexual intercourse) | Lesbians: CSA 31%, CPA 22%, Parental drinking problems (one parent 32%, two parents 4%) | Among lesbian women, CSA had a direct relationship with alcohol abuse and CPA had a direct relationship with psychological distress. CSA had an indirect relationship with elevated risk of lifetime alcohol abuse through negative effects on age at first heterosexual intercourse. Parent-related variables (i.e., parental strictness and parental drinking problems) were directly associated with lifetime psychological distress, which was directly associated with lifetime alcohol abuse. Age of drinking onset mediated the association between parental drinking problems and lifetime alcohol abuse and lifetime psychological distress. |

| Matthews et al. (2002) | None specified | Physical violence, CSA, stress, social support, coping strategies | Depressive symptoms | CSA: lesbian: 45% heterosexual: 41 % |

Education, race, sexual identity, CSA, physical abuse, global stress, current stress, coping skills, and emotionality were associated with one or more correlates of depressive distress among lesbian and heterosexual women. Education, sexual orientation, CSA, physical abuse, and emotionality were associated with suicide attempts, while the other variables were not significantly associated. Associations between independent variables and depressive symptoms differed between lesbian and heterosexual women (i.e., different variables had significant associations based on sexual identity). Reported suicide attempts were substantially higher among lesbian than heterosexual women. |

| Morris and Balsam (2003) | None specified | CSA | Sexual revictimization and mental health | CSA: 39.3% | Of participants who reported CSA, 25.7% reported that the abuse was perpetrated by a relative and 23.7% by an acquaintance. CSA was found to predict current psychological distress. Multiple forms of victimization more strongly predicted current psychological distress. Individuals who experienced sexual abuse in childhood were also significantly more likely to report adult physical abuse and ASA. |

| Persson et al. (2015) | Mentions minority stress (Meyer, 2003) | CA, risky sexual behavior, sexual identity disclosure | depression and anxiety | CA: non-monosexual women: 33.6% Monosexual women: 15.5% |

The relationships of sexual identity with depression and anxiety were mediated by sexual orientation disclosure and risky sexual behavior: lower levels of disclosure and higher levels of risky sexual behavior were positively associated with higher depression and anxiety. CA did not moderate the relationships between sexual identity or sexual behavior with depression, anxiety, or risky sexual behavior. |

| Robohm et al. (2003) | Finkelhor and Browne (1985) CSA survivors experience “traumatic sexualization” (i.e., sexuality shaped in a confusing way) | CSA | Emotional/behavioral difficulties, feelings about one’s sexuality and coming out | CSA: 37.9% | Individuals who reported CSA also reported significantly more emotional/behavioral difficulties than those who did not report CSA. Of the individuals who reported CSA, 46.4% indicated that the experience of CSA affected their feelings about their sexuality or how they came out. |

| Zietsch et al. (2012) | Common cause (shared genetic or environmental etiology) explanations | Risky childhood family environment, CSA, CPA | Depression | Family dysfunction: SM: males: 41%, females: 42% heterosexual: males: 24%, females: 30%, CSA SM: males: 12%, females: 24%, heterosexual: males: 4.2%, females 11%, CPA SM: males: 38%, females: 40% heterosexual: males: 40%, females: 27%, | Sexual minorities had significantly higher rates of depression in the study sample. Twin pairs with one heterosexual and one sexual minority had higher rates of depression than hetero pairs. (2) CSA partially explained the correlation between sexual orientation and depression. |

| Substance use | |||||

| Drabble et al. (2013) | References minority stress theory (Meyer, 2003) in the introduction | CSA, CPA, ASA, physical abuse in adulthood, lifetime victimization | HD | CPA: only heterosexual: 18.3%, heterosexual w same sex partners: 24.5%, bisexual: 35.5%, lesbian: 31.3% CSA: only heterosexual: 10.6%, heterosexual w same sex partners: 18%, bisexual: 25.5%, lesbian:23% | Women with same-sex partners, regardless of sexual identity (i.e., lesbian, bisexual, heterosexual) reported higher rates of lifetime victimization than heterosexual women without same-sex partners. 2. SMW had higher odds of HD than only heterosexual women. Physical and sexual CV were strongly associated with HD. Odds of HD were higher among SMW; this relationship was not fully attenuated by adding demographics and victimization into the model, suggesting that victimization only partially explains elevated HD among SMW. |

| Hequembourg et al. (2013) | No a priori theory, although minority stress theory (Meyer, 2003) was used in discussion | CSA | risky alcohol use | CSA: 51.2% | 75.2% of women reported at least one day of heavy episodic drinking in the last 6 months. There was a significant relationship between adult victimization severity and bisexual identity, more severe CSA, more lifetime sex partners, and higher alcohol severity scores. Bisexual women reported more severe adult victimization, greater revictimization, riskier drinking patterns, and more lifetime male sexual partners than lesbian counterparts. |

| Hughes et al. (2010b) | References minority stress theory (Meyer, 2003) | CSA, ASA, Revictimization | HD | CSA: heterosexual 17%, mostly lesbian 42%, bisexual 40%, only lesbian 39%, mostly heterosexual 33% | Levels of HD were significantly higher among SMW (mostly heterosexual M = 1.50, bisexual M = 1.89, mostly lesbian M = 1.42, only lesbian M = 1.08) than heterosexual women (M = 0.74). Heterosexual women reported the least victimization. Of all groups, bisexual women reported the highest revictimization. HD differed by victimization history. Compared to SMW without a history of sexual trauma (M = 0.88) and those who reported one form of trauma (ASA only, M = 0.85), women with a history of adulthood revictimization reported significantly higher HD (M = 1.35). Sexual identity significantly moderated the relationship between victimization and HD (F[12,792{=1.99, p = .02}]) after controlling for demographics and age of drinking onset. Bisexual women who reported CSA alone had the highest level of HD. |

| Hughes et al. (2001) | No a priori theory, references minority stress theory (Meyer, 2003) | Sexual orientation, CSA, ASA | Lifetime alcohol abuse, CSA | Wyatt CSA: lesbian: 68%, heterosexual: 47%, Self-perceived CSA: lesbian: 37%, heterosexual: 19% | Compared to heterosexual women, lesbian women reported more childhood sexual experiences and were more likely to both meet CSA criteria and to perceive that they had experienced CSA. Among lesbian and heterosexual women, CSA was associated with lifetime alcohol abuse. |

| Hughes et al. (2010a) | References minority stress theory (Meyer, 2003) | CSA, Childhood neglect, CPA | SUDs | CSA: lesbian 34.7%, bisexual 38.8%, not sure 9.2%, heterosexual 10.3%, CPA: lesbian 11.3%, bisexual 11.1%, not sure 4.5%, heterosexual 3.8% Neglect: lesbian 12.4%, bisexual 8.7%, Not sure 7.1%, heterosexual 3.4% | Compared to heterosexual women, bisexual women were more likely to report CSA, CPA, partner violence, and non-partner violence, whereas lesbian women were only more likely to report CSA. Compared to heterosexual and unsure women, lesbian and bisexual women were twice as likely to meet criteria for any past year SUD and to report any victimization. Among lesbian women, prevalence of SUDs was higher for those reporting CPA, CN, and partner violence. Among bisexual women, SUD prevalence was higher for those reporting CSA, partner violence, and assault with a weapon. Reporting CN strengthened the association between lesbian identity and alcohol dependence. |

| Hughes et al. (2014) | Minority Stress (Meyer, 2003) | Lifetime victimization xperiences | HD, depression | CSA: 35.5%, CPA: 39.5%, Parental drinking problems: 27.2% | Number of types of victimization (of six total types) was significantly associated with HD. Each additional type of victimization reported by participants corresponded with 20% increased odds of HD. Compared to participants who did not report victimization, those who experienced CV were significantly more likely to report depression. |

| Johnson et al. (2013) | Self-medication hypothesis versus impaired functioning | Parental Drinking, CSA | HD | CSA: 32.3% | There was no significant association between CSA and age of drinking onset. At Wave 1, there was a significant association between CSA and depression. |

| McCabe et al. (2020a) | No a priori theory, minority stress theory (Meyer, 2003) used in the discussion to explain gender differences | Household dysfunction | DSM-5 Alcohol, tobacco, and other SUDs | Parental/household history of alcohol or drug problems—lesbian/Gay: 34.7%, Bisexual: 34.0%, Not sure: 37.1%, Heterosexual: 26.2% | The risk of SUDs was the same for individuals reporting one indicator of household dysfunction and those who reported multiple indicators of household dysfunction. This was somewhat moderated by sexual identity (marginal significance at p < .05). The “not sure” subgroup (SM) had the highest risk, followed by bisexuals, then gay/lesbian, then discordant heterosexual, then concordant heterosexual. SM had consistently higher ACE means and risk of comorbid disorders than heterosexual, especially concordant heterosexuals. |

| Lehavot et al. (2014) | Discussed self-medication hypothesis in the discussion | CPA, CSA, CEA, EN, and PN | Alcohol misuse | CTQ Score: Heterosexual: 1.96 (0.83), Lesbian/bisexual: 2.28 (0.93) | SMW were more likely to report CV compared to heterosexual veterans and greater severity of CV. SMW also had higher levels of alcohol misuse, greater number of depressive symptoms, and worse PTSD. Path analysis revealed that CV was associated with depressive symptoms, PTSD symptoms, and alcohol misuse. Sexual identity was indirectly associated with alcohol misuse via CT and depression, civilian physical victimization and PSTD, and military physical victimization/depression/PSTD. |

| Lehavot and Simpson (2014) | Minority stress (Meyer, 2003) | CA, ASA, military trauma or stress, adult physical victimization | PTSD and depression | CTQ Score: Heterosexual: 1.97 (0.84), Lesbian/bisexual: 2.28 (0.93) | Lesbian and bisexual women were more likely to report CV compared to heterosexual women. In logistic regression models, CT and trauma experienced during the military added the most variance to models of PTSD and depression. |

| Reisner et al. (2013) | Life course framework (Pearlin et al., 2005) | Any CA | Substance misuse | CA: lesbian: 26.2%, Bisexual: 36.2%, Other SM: 22.2%, heterosexual: 13% | Disparities in substance misuse for heterosexual vs. lesbian/bisexual women, with SMW reporting greater substance abuse. CA was significantly associated with lifetime substance abuse for all participants. However, disparities in substance misuse were attenuated by adding CA to the regression model. |

| Roberts et al. (2005) | No theory but mentioned risk factors for alcohol (e.g., lesbians may be more likely to socialize in bars) | CSA | Use and abuse of alcohol | CSA and alcoholism: 67% CSA and no alcoholism; 47% | 71% of lesbian women in the sample reported that they currently drink alcohol. 28% self-reported not being a “normal” drinker, 7% said others “complain or worry” about their drinking, 14% that they “feel bad about their drinking,” 22% that they are not “always able to stop drinking” when they want to, 3% that they have “trouble at work due to drinking”, 3% that have been “arrested for drunk driving, and 12% that they are an alcoholic. No statistical analyses performed.” |

| Sigurvinsdottir and Ullman (2016) | Minority stress (Meyer, 2003) and intersectional minority stress | CSA | Sexual assault recovery (depression and PTSD) | CSA 65.9% | Only data from bisexual and heterosexual female respondents were analyzed. Participants who experienced CSA and/or adult revictimization reported a higher number of PTSD symptoms than other participants. Looked at trajectory of PTSD recovery by sexual identity and found that black bisexual women had the highest number of PTSD symptoms. |

| Talley et al. (2016) | No a priori theory, although self-medication hypothesis mentioned in the discussion | CSA and CPA | Alcohol and other drug use and internalizing symptoms | CSA: mostly heterosexual 19%, bisexual 50%, only heterosexual 11%, mostly lesbian 11%, lesbian 20% CPA: only heterosexual 4%, mostly heterosexual 18%, bisexual 27%, mostly lesbian 0%, lesbian 4% | Compared to mostly heterosexual women, bisexual women were more likely to report CSA, whereas no other sexual identity subgroups significantly differed from mostly heterosexual women. Compared to only heterosexual women, mostly heterosexual women were more likely to report CPA. Mostly heterosexual did not differ significantly from all other sexual identity subgroups. Mostly heterosexual women were more likely to report lifetime substance abuse (e.g., tobacco, marijuana) and AUD than only heterosexual women. No regression analyses were done to examine associations between CSA, sexual identity, and AUD. |

| Wilsnack et al. (2008) | Environmental, social role, and minority stress theory (Meyer, 2003) | CSA | Drinking levels (mean ounces ethanol per day), HD | CSA: only heterosexual: 28.8%, Mostly heterosexual: 41.9%, Bisexual: 73.8%, Mostly lesbian: 57.9%, Only lesbian: 59.1% | Compared to every SMW group, heterosexual women abstained more from alcohol use and were lower in all HD indicators (e.g., heavy drinking, lifetime problem consequences, concerns about having a drinking problem, receiving help for a drinking problem, dependence). Compared to all other subgroups (e.g., heterosexual, only lesbian, mostly lesbian), bisexual women recognized more HD indicators, past year depression, and lifetime depression. Bisexual women were also most likely to report CSA. |

| Yuan et al. (2014) | No a priori theory. Proximal stressors hypothesized to explain the lack of association between CT and alcohol misuse | CT (i.e., CPA, PN, CSA, CEA) | Alcohol misuse | CSA TS women: 70.1%, TS men: 50.8%, CPA TS women: 68.4%, TS men: 62.7% PN TS women: 70.1%, TS men: 61.6%, EN-TS women: 46.2%, TS men: 34.5%, CEA TS women 71.4%, TS men 60.5% | Among two-spirit participants, women reported higher levels of all forms of abuse than men including CSA, CPA, PN, EN, and CEA. There were no significant associations between CSA and substance-related outcomes (i.e., alcohol dependence, hazardous and harmful use, binge drinking). Further, the relationship between number of ACEs and past-year binge drinking or spree drinking was not significant. |

| Physical Health | |||||

| Aaron and Hughes (2007) | None specified | CSA | BMI | CSA: 31% of total sample. Latinx women (40%), Black women (33%), White women: 26% | More Latinx women and Black women reported CSA than White women (p = .05). BMI was or >25 among 57% of the sample. Among women who reported CSA, mean BMI was significantly higher (29.4) than among women who did not (27.1, p < .01). Obesity was significantly higher among women who reported CSA (39%) versus women who did not report CSA (25%, p = .0004). Obesity and severe obesity were also significantly higher among Black (33%, 11%) and Latinx lesbians (23%, 5%) than White lesbians (15%, 7%, p < .001). Women who reported CSA had higher odds of obesity (OR = 1.9, 95% CI [1.1, 3.4]) and severe obesity (OR = 2.3, [1.1, 5.2]) when controlling for sociodemographic variables. |

| Lee et al. (2020) | Minority stress (Meyer, 2003) and Health Equity Promotion Framework (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2014) | Childhood food insecurity, childhood exposure to drug abuse, CPA, CEA | Smoking | Not reported | For SGM adults (all genders combined, age 18–24) who experienced CPA, the unadjusted odds of smoking were 2.03 (CI [1.02, 4.05]) times higher than among those who did not experience CPA; there was no significant difference in odds of smoking among young SGM adults based on childhood food insecurity, substance abuse in the home, or CEA. Among adults (age 25+), there were no significant associations between any ACEs and smoking. Among bisexual adults (all genders), those who reported substance abuse in the home had 1.45 [1.01, 2.09] times higher odds of smoking than those who did not. Those who reported CPA had 1.54 [1.07, 2.24] times higher odds of smoking than those who did not. There was no significant difference in odds of smoking among bisexual adults based on food insecurity or CEA. ACEs were not associated with smoking among lesbians. |

| Smith et al. (2010) | Protective measures theory (CSA survivors maintain higher BMI to protect against sexualization) (Gustafson & Sarwer, 2004) | CSA | Obesity | Intrafamilial CSA: 16.2% heterosexual women, 29.6% lesbian women Extrafamilial CSA: 14.3% heterosexual 30.7%, lesbian women |

In the full sample, odds of obesity were 1.94 (CI [1.39, 2.72]) times higher among those who reported intrafamilial CSA and 1.46 (CI [1.04, 2.06]) times higher among those who reported extrafamilial CSA, adjusting for sexual identity and whichever form of CSA was not the independent variable being analyzed. In multiple logistic regression models, intrafamilial CSA was the only form of abuse (i.e., intrafamilial CSA, extrafamilial CSA, and ASA) significantly associated with obesity (AOR 1.58, CI [1.10, 2.27]). Having a bachelor’s degree or higher was protective against obesity for extrafamilial CSA and adult SA, whereas household income of $75,000 or higher was protective in all models. |

| Matthews et al. (2013) | None specified | CPA | Current smoking, age of smoking onset, health status | CPA 21.5% of SMW | There were no significant associations between sexual identity with CPA, health status, age of smoking onset, or current smoking. 25% were current smokers, mean age of smoking onset was 19–20, and mean perceived health was fair to good. CPA was significantly indirectly associated with self-reported health status, mediated by age of smoking onset and current smoking status. |

| Sweet and Welles (2012) | None specified | CSA | HIV/STI risk | CSA: bisexual 43.5%, lesbian 38.1%, heterosexual w/same-sex partners: 28%, heterosexual w/same-sex attraction but no partners: 17%, heterosexual w/no same-sex attraction or partners: 14.2% | Compared to heterosexual women with no same-sex attraction or partners, bisexual women had 5.3 times the odds of sometimes/frequent CSA, lesbians had 3.4 times the odds, heterosexual women with same-sex partners had 2.9 times the odds, and heterosexual women with same-sex attraction but not same-sex partners had 1.6 times the odds of reporting CSA. Among SMW, those who reported CSA “almost never” were 7.1 times as likely and those who reported CSA sometimes/frequently were 3.8 times as likely to have an HIV or STI diagnosis in the past 12 months compared to SMW who reported no CSA. |

| Caceres et al. (2019) | Minority stress (Meyer, 2003) and Traumatic Stress Model of Cardiovascular Disease (Dedert et al., 2010) | CA, adult trauma, lifetime trauma | Psychosocial and behavioral risk factors, self-reported cardiometabolic risk) | 1 type: 40.2%, 2 types: 33.3%, 3 types: 6.8% | Compared to white SMW, SMW of color reported higher CT rates. Compared to SMW aged 18 to 30, SMW aged 41 to 75 reported higher rates of CT. SMW who completed graduate school were less likely to report CT than those with less education. There were significant associations between all forms of trauma and probable PTSD diagnosis and lower perceived social support. All forms of trauma were significantly associated with depression. CT was significantly associated with higher odds of past-3-month overeating. When controlling for demographics and psychosocial and behavioral risk factors, there remained a significant association between CT and diabetes. |

| Wright (2018) | Minority stress (Meyer, 2003) | CSA | Attitudes toward obesity and BMI | CSA: 37.6% | 35.3% had BMI ≥ 30, with a mean BMI of 28.9 (SD: 8.47) with mean attitude scores showing high acceptance of obese people. There were no significant associations between CSA and attitudes toward obesity or between BMI and attitudes toward obesity, although there was a negative association between CSA and BMI (i.e., SMW who reported CSA had lower BMI). Neither BMI nor CSA predicted attitudes toward obesity, nor was there an interaction between BMI and CSA. There were no differences in attitudes toward obesity based on combinations of BMI and CSA. |

| Crump and Byers (2017) | Traumagenic Dynamics Model (Finkelhor & Browne, 1985) | CSA | Frequency/duration of sex, thoughts during sex, sexual desire, esteem, satisfaction, and anxiety | CSA involving fondling only: 18%, CSA involving vaginal/anal/oral penetration: 14% | SMW who reported penetrative CSA were significantly more likely to report adolescent/adult sexual abuse compared to SMW who reported fondling CSA and those who reported no CSA (77%, 56%, and 32%, respectively). There were significant differences between the four groups (no lifetime sexual abuse, adolescent/adult sexual abuse only, CSA limited to fondling, CSA involving attempted/completed penetration on sexual desire, sexual satisfaction, and automatic sexual thoughts, but not on frequency, duration, sexual esteem, or sexual anxiety. SMW reporting penetrative CSA had significantly lower desire and satisfaction and more frequent negative automatic thoughts compared to the other groups. |

| Katz-Wise et al. (2014) | Minority stress (Meyer, 2003) | Sexual identity; CA, weight-related behaviors, demographic variables | 1 year change in BMI | 1 Type: lesbian 19.2%, bisexual 16.5%, mostly heterosexual 21.8%, only heterosexual 17.8% 2 Types: lesbian 17.3%, bisexual 14.7%, mostly heterosexual 14.7%, only heterosexual 10.1% 3 to 4 Types: lesbian 13.5%, bisexual 19.4% mostly heterosexual 12.1%, only heterosexual 5.5% | Compared to heterosexual women, bisexual women had larger 1-year increases in BMI. 2. Child abuse and weight-related behaviors slightly attenuated the relationship between sexual orientation and BMI. |

| Sweet et al. (2013) | None specified | CSA | HIV/STI incidence | Not reported | Individuals reporting CSA had higher odds of a mental health disorder and AUD. Compared to heterosexual women who reported no CSA, SMW had higher risk of HIV/STI incidence (1.9 times the risk for SMW who reported no CSA, 8.3 times for SMW who reported experiencing CSA rarely, and 6.3 times the risk for SMW who reported sometimes/frequent CSA). The relationship between CSA and HIV/STI risk was more than 34% mediated by mental health among SMW sometimes/frequently abused. |

| Lehavot and Simoni (2011) | None specified | 5 types of CA | Chronic physical health problems, ASA, smoking | CEA: 59%, CPA: 35%, CSA 40%, EN: 61%, PN: 41% | 45% of women reporting any form of CA reported ASA, compared to 20% of those not reporting any CA (p < .01). CA had a significant direct association with ASA, smoking, and physical health problems. ASA was not associated with smoking or physical health problems, controlling for CA. Smoking did not mediate the relationship between CA and chronic physical health problems. |

| Greene et al. (2019) | Intersectionality theory (Crenshaw, 1990) | CPA, CSA | Past-year cervical cancer screening | CSA: 38.4% CPA: 23.3% | CPA was one of six predictor variables deemed most important (out of 25 potential variables initially) in predicting self-report of past-year Pap. SMW who did not report CA, along with women under 62, who began drinking before age 14, who had health insurance, who reported lower internalized homonegativity, and had fewer than 28 lifetime sexual partners, were less likely to report a past-year Pap test (30%). |

| Andersen et al. (2014) | None specified | CSA, CPA, cumulative CV | Physical health problems | CSA: bisexual 71.4%, lesbian 59.2%, mostly heterosexual 43.9%, heterosexual 31.2% CPA: bisexual 40.9%, lesbian 21.6%, mostly heterosexual 19.0%, heterosexual 9.4% | Bisexual, lesbian, and mostly heterosexual women had higher CSA and CPA than heterosexual women (p < .001). Neither CSA nor CPA were independently associated with physical health problems, adjusting for demographics and health correlates. Women who reported both CSA and CPA were 1.44 times (95% CI [0.99, 2.10], p = .056) more likely to report physical health problems than those who didn’t report either CA. Sexual identity did not moderate the association between victimization and physical health problems. |

| Multiple Health and Social Outcomes | |||||

| Hyman (2000) | Used a model (Frank & Gertler, 1991) combining socialization and human capital formulations of earnings | CSA | Physical health, mental health, educational attainment, economic welfare | Not reported | Among lesbian women, CSA survivors were more likely to have poorer physical and mental health and to earn less money; additionally, they were less likely to earn a college degree. Extrafamilial CSA by a stranger and intrafamilial CSA with coercion were the most strongly associated with lower earnings both directly and indirectly, through physical and mental health and education. Intrafamilial CSA without coercion was indirectly associated with lower earnings through physical and mental health and education. Extrafamilial CSA with a known perpetrator was not associated with lower earnings. |

| Revictimization and other experiences of interpersonal violence | |||||

| Austin et al. (2008b) | None specified | Sexual identity | Sexual risk indicators | CSA: 45% mostly heterosexual, 15% heterosexual | Mostly heterosexual women were more likely to have experienced CSA, and to report having an STI compared to heterosexual women. Mostly heterosexual women also reported an earlier age at first intercourse and more sexual partners than heterosexual women. CSA did not mediate the relationship between sexual identity and these sexual risk factors. |

| Han et al. (2013) | None specified | CSA, alcohol use, PTSD | ASA | CSA only: 22.1% Adulthood revictimization and CSA: 13.9% | Alcohol use was the best predictor of ASA among lesbians. CSA was the best predictor of ASA among gay men. |

Note. CA = Child abuse; CSA = childhood sexual abuse; CPA = child physical abuse; CN = childhood neglect; CEA = childhood emotional abuse; TS = two-spirit; IH = internalized homophobia; EA = experiential avoidance; EN = emotional neglect; PN = physical neglect; CTQ = CT Questionnaire; SUDs = substance use disorders; AUD = alcohol use disorder; HD = hazardous drinking; CV = childhood victimization; CT = childhood trauma; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; ACE = adverse childhood experiences (ACEs); BMI = Body Mass Index; CI = confidence interval; LGB = lesbian, gay, bisexual; SM = sexual minority; SMW = sexual minority women.

In the following five sections, study findings are synthesized and categorized by themes.

Mental Health.

Eleven studies examined the relationship between ACEs and negative mental health outcomes, including suicidal thoughts and/or behavior (e.g., attempts/ideation) (Flynn et al., 2016; Matthews et al., 2002), symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Andrés-Hyman et al., 2004; Caceres et al., 2019; Gold et al., 2011; Lehavot & Simpson, 2014; Sigurvinsdottir & Ullman, 2016), depression (Hughes et al., 2014; Persson et al., 2015; Zietsch et al., 2012), emotional/behavioral difficulties (Robohm et al., 2003), psychological distress (Hughes et al., 2007; Morris & Balsam, 2003), and experiential avoidance (i.e., the desire to avoid emotions, cognitions, or body sensations related to painful events) (Gold et al., 2011). Overall, the results of these studies indicate that ACEs are significantly associated with depression, psychological distress, PTSD symptoms, and suicidal ideation and attempts among SMW.

Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors

Matthews et al. (2002) and Flynn et al. (2016) examined the relationship between CPA and CSA and suicidal thoughts and behaviors (e.g., ideation and attempts). In their study of 829 lesbian and heterosexual women, Matthews et al. (2002) found that CSA was significantly associated with suicidal ideation among all participants; however, CSA was only significantly associated with suicide attempts among lesbian women. Similarly, CPA was associated with suicidal ideation among all participants, but CPA was only associated with suicide attempts among lesbian women. In Flynn et al. (2016)’s study of 34,175 SM and heterosexual men and women, CSA mediated the relationship between lesbian, gay, bisexual (LGB) identity and attempted suicide for men and women; CPA mediated the relationship between sexual identity and suicide for SMW only.

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Four studies examined the relationship between CSA and symptoms of PTSD. In a study of 257 SMW and heterosexual women CSA survivors, Andrés Hyman et al. (2004) found that asexual women reported the lowest number of intrusive and total PTSD symptoms among all groups (i.e., asexual, heterosexual, lesbian, and bisexual). Further, compared with African American/Black, White, and other racial/ethnic minority women, Latina women reported the fewest intrusive PTSD symptoms. In a longitudinal study of the relationship between race, sexual identity, and PTSD symptoms, Sigurvinsdottir and Ullman (2016) found that Black bisexual women and non-Black bisexual women reported the highest levels of PTSD symptoms compared to all heterosexual women. Lehavot et al. (2014) found in their sample of 706 SM and heterosexual veterans that lesbian and bisexual women were more likely than heterosexual women to report childhood victimization (i.e., CPA, CSA, childhood emotional abuse, emotional neglect, and physical neglect). In logistic regression models, childhood trauma and trauma experienced during military service added the most variance to models examining PTSD and depression. Finally, in a study of lifetime trauma, cardiometabolic risk, and psychosocial risk factors, Caceres et al. (2019) found significant associations between all forms of trauma (CPA, CSA, childhood parental neglect, physical abuse, sexual abuse, and intimate partner violence) and probable PTSD diagnosis. Study participants who reported trauma (i.e., childhood and/or adult) also reported lower perceived social support.

Depression

In an Australian study examining mental health in twin pairs (N = 9884 individuals), in both male and female twins, pairs of one heterosexual and one SM twin had higher rates of depression than did pairs of heterosexual twins. CSA partially explained the correlation between sexual identity and depression (Zietsch et al., 2012). There were no differences based on sex. In a study conducted with a community-based sample of SMW, Caceres et al. (2019) found that childhood and lifetime trauma were significantly associated with higher odds of depression (OR: 1.41; CI [1.12, 1.77]). Persson et al. (2015) examined the relationship between sexual identity and depression and anxiety in a sample of 388 heterosexual and SM women. The relationships of sexual identity with depression and anxiety were mediated by sexual orientation disclosure and risky sexual behavior: lower levels of disclosure and higher levels of risky sexual behavior were positively associated with higher levels of depression and anxiety. Childhood abuse did not mediate this relationship. The authors hypothesized that the lack of association may have been due to collapsing three childhood abuse variables (CSA, CPA, and psychological abuse), potentially masking differences between the forms of abuse assessed. Johnson et al. (2013) found a direct relationship between CSA and depression in a sample of 443 SMW. Additionally, using data from a pooled sample in a study of SMW in Chicago and women from a national general population study (that included both heterosexual and SM women), Hughes and colleagues (2014) found that compared to participants who did not report victimization, those who reported childhood victimization (i.e., CSA, CPA, parental neglect) were significantly more likely to report depression.

Other Psychological Outcomes

Using data from a national U.S. sample of 2,431 SMW, Morris and Balsam (2003) found that history of CSA was associated with current psychological distress (measured using a scale developed by Derogatis & Spencer, 1982). In a study of 227 lesbian and bisexual women, Robohm et al. (2003) found that SMW who reported CSA reported significantly more emotional/behavioral difficulties than those who did not report CSA. Gold et al. (2011) compared lesbian women and gay men, and found that lesbian women were more likely to endorse CPA; those reporting CPA were more likely to report lifetime sexual victimization. Lesbian CPA survivors also reported more symptoms of depression and PTSD (e.g., experiential avoidance or the desire to avoid emotions, cognitions, or body sensations related to painful events) than those who did not report CPA. Among lesbian women, CPA was not associated with internalized homophobia, nor did internalized homophobia mediate the relationship between CPA and depression or PTSD symptoms. However, experiential avoidance mediated the relationships between CPA and depression and CPA and PTSD. Finally, Hughes et al. (2007) found that CPA had a direct relationship with psychological distress (defined as combination of two negative mood states: depression and anxiety).

Substance Use.

Fifteen studies examined the relationship between ACEs and substance use-related problems (Drabble et al., 2013; Gilmore et al., 2014; Hughes et al., 2007, 2010a, 2010b; Lehavot et al., 2014; McCabe et al., 2020a; Reisner et al., 2013; Roberts et al., 2005; Wilsnack et al., 2008; Yuan et al., 2014). Of these, 11 focused exclusively on alcohol-related outcomes and four examined both alcohol and other drug use outcomes. Five of the fifteen studies used data from the Chicago Health and Life Experiences of Women (CHLEW) study, a longitudinal study of more than 800 SMW (447 from Wave 1 and a supplemental sample of 368 SMW added in Wave 3). Together, results of these studies provide compelling evidence that ACES are associated with substance use outcomes among SMW.

In a small pilot study, Hughes et al. (2001) found that compared to heterosexual women (n = 57), lesbian women (n = 63) reported more forms of CSA (range = 0–8; e.g., sexual kissing, fondling, intercourse), were more likely to meet criteria for CSA based on Wyatt’s (1985) definition, and to define their experiences as CSA. Among both lesbian and heterosexual women, CSA was associated with lifetime alcohol abuse. Using data from an internet-based survey of 699 U.S. veterans, Lehavot et al. (2014) examined mediators of sexual orientation-related disparities in alcohol misuse among heterosexual and SM women veterans. Lesbian and bisexual women were more likely than their heterosexual counterparts to report childhood victimization (emotional, physical, and sexual abuse; emotional and physical neglect) and more severe forms of victimization. They were also more likely to report alcohol misuse, greater number of depressive symptoms, and worse symptoms of PTSD. Path analysis revealed that childhood victimization was associated with depressive symptoms, PTSD symptoms, and alcohol misuse. Minority sexual identity was also indirectly associated with alcohol misuse via childhood trauma and depression, civilian physical victimization and PSTD, and military physical victimization, depression, and PSTD. Similarly, in a national sample of 4,119 SMW, Gilmore et al. (2014) found that more severe forms of CSA (i.e., involving penetration) were indirectly associated with greater number of drinks consumed per week and higher perceived peer norms for drinking (i.e., estimation of the number of drinks that lesbian/bisexual women consume daily).

In a study of 1,139 lesbian women from the Boston Lesbian Health Project, Roberts et al. (2005) found that 12% self-identified as alcoholic. Among these participants, 67% reported CSA, compared with 47% of those who did not report alcoholism. No results of statistical analyses were reported in this study. In a later study using a community sample of SM and heterosexual men and women, Reisner et al. (2013) found that lesbian and bisexual women reported greater substance misuse than heterosexual women, and that sexual orientation-related disparities in substance misuse were mediated by childhood abuse.

Using data from a college sample of 332 women, Talley et al. (2016) found that compared with all other sexual identity subgroups (i.e., exclusively gay/lesbian, mostly lesbian, mostly heterosexual, and exclusively heterosexual), bisexual women were most likely to report CSA. Mostly heterosexual women were more likely to report lifetime substance abuse (e.g., tobacco, marijuana) and meet criteria for alcohol use disorder than exclusively heterosexual women. No information about associations among CSA, sexual identity, and alcohol use disorder was reported—reducing the ability to make inferences about sexual orientation-related disparities in substance use in this study sample.

Using data from the National Alcohol Survey, Drabble et al. (2013) examined sexual identity differences in the relationship between CPA and CPA and adult physical and sexual victimization with hazardous drinking among women (N = 11,169). SMW had higher odds of hazardous drinking than exclusively heterosexual women. Regardless of sexual identity, women who reported histories of having a same-sex partner were more likely to report lifetime victimization than heterosexual women without such histories. Even when controlling for victimization, significant sexual orientation-related disparities in hazardous drinking remained, suggesting that victimization only partially explains elevated hazardous drinking among SMW.

Using data from a U.S.-based sample, the National Epidemiologic Survey of Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), Hughes et al. (2010a) examined victimization (i.e., CSA and adult sexual assault (ASA) and SUD in a sample of 34,653 heterosexual and SM women and men. Compared to heterosexual women, bisexual women were more likely to report CSA, CPA, intimate partner violence, and non-partner violence, whereas lesbian women were only more likely to report CSA. Compared to heterosexual women and those unsure about their sexual identity, both lesbian and bisexual women were twice as likely to meet criteria for any past-year SUD and to report any form of victimization (childhood or adulthood). Among lesbian women, the prevalence of SUDs was higher among those who reported CPA, childhood neglect, and intimate partner violence. Among bisexual women, SUD prevalence was higher among those who reported CSA, partner violence, and assault with a weapon. Reporting childhood neglect strengthened the association between lesbian identity and alcohol dependence. In a later study using NESARC data, McCabe et al. (2020a) examined associations among childhood household dysfunction (e.g., an adult in the home was a problem drinker or alcoholic), sexual identity, alcohol, tobacco, and other SUDs in adulthood. Results indicated a curvilinear relationship between the number of indicators of household dysfunction and each SUD, suggesting that there were no differences in the probability of developing a SUD between participants (both male and female) who reported one type of household dysfunction and those who reported multiple types. Further, even when accounting for household dysfunction, SMW had a higher risk of alcohol use disorders, tobacco use disorders, and other SUDs than heterosexual women. Finally, Yuan and colleagues (2014) found no significant associations between CSA and substance-related outcomes (i.e., alcohol dependence, hazardous and harmful alcohol use, binge drinking) among SMW in a study of Two-Spirit identified individuals (a term used by North American indigenous people who identify as having both feminine and masculine spirit).