Abstract

Mycoplasma hominis mutants were selected stepwise for resistance to ofloxacin and sparfloxacin, and their gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE quinolone resistance-determining regions were characterized. For ofloxacin, four rounds of selection yielded six first-, six second-, five third-, and two fourth-step mutants. The first-step mutants harbored a single Asp426→Asn substitution in ParE. GyrA changes (Ser83→Leu or Trp) were found only from the third round of selection. With sparfloxacin, three rounds of selection generated 4 first-, 7 second-, and 10 third-step mutants. In contrast to ofloxacin resistance, GyrA mutations (Ser83→Leu or Ser84→Trp) were detected in the first-step mutants prior to ParC changes (Glu84→Lys), which appeared only after the second round of selection. Further analysis of eight multistep-selected mutants of M. hominis that were previously described (2) revealed that they carried mutations in ParE (Asp426→Asn), GyrA (Ser83→Leu) and ParE (Asp426→Asn), GyrA (Ser83→Leu) and ParC (Ser80→Ile), or ParC (Ser80→Ile) alone, depending on the fluoroquinolone used for selection, i.e., ciprofloxacin, norfloxacin, ofloxacin, or pefloxacin, respectively. These data indicate that in M. hominis DNA gyrase is the primary target of sparfloxacin whereas topoisomerase IV is the primary target of pefloxacin, ofloxacin, and ciprofloxacin.

Fluoroquinolones are broad-spectrum antibiotics used for the treatment of a wide range of infections. Among these antimicrobial agents, ofloxacin (OFX) and ciprofloxacin (CFX) show good activity against mycoplasmas. However, sparfloxacin (SFX), one of the recently commercialized fluoroquinolones, was found to exhibit improved activity against these wall-less organisms and appeared to be one of the most potent (32). The main targets of quinolones are two members of the topoisomerase II family, DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV, which are both essential for bacterial viability (12, 19).

Quinolone resistance appears to be due mainly to mutational alterations of the target enzymes: mutations in (i) the quinolone resistance-determining region (QRDR) of the GyrA (3, 6, 7, 8, 13, 17, 23, 35) and GyrB (17, 23, 37) subunits of DNA gyrase and (ii) similar regions of the ParC (3, 7–9, 13, 15, 23, 24, 34) and ParE (5, 26) subunits of topoisomerase IV. Several studies with various bacteria have assessed the primacy of gyrase or topoisomerase IV as the primary target of fluoroquinolones. In Escherichia coli, DNA gyrase is thought to be the primary target of various quinolones, including nalidixic acid, norfloxacin (NFX), OFX, and CFX (5, 11, 19). Similar results have been reported for the CFX resistance of other gram-negative bacteria, such as Neisseria gonorrhoeae (3), Klebsiella pneumoniae (7), and Haemophilus influenzae (13). Inversely, topoisomerase IV was identified as the primary target of CFX in the gram-positive bacteria Staphylococcus aureus (8, 9, 34) and Streptococcus pneumoniae (23, 24, 31). Interestingly, a recent study by Pan and Fisher (25) indicated that in S. pneumoniae, gyrase is the primary target of SFX.

In a previous study (2), eight multistep NFX-, pefloxacin (PFX)-, OFX-, and CFX-resistant mutants of Mycoplasma hominis were selected in broth medium and their GyrA and GyrB QRDRs were characterized. We now present data on the status of the ParC and ParE QRDRs of these multistep-selected mutants. Also in this report, we describe the characterization of GyrA, GyrB, ParC, and ParE QRDRs of stepwise-selected OFX- and SFX-resistant mutants. Our data indicate that in M. hominis, topoisomerase IV is the primary target of OFX whereas gyrase is the primary target of SFX.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and vectors.

E. coli JM109 was used as the host for cloning experiments and for amplification of recombinant plasmids. M. hominis reference strain PG21 was used for selection of quinolone-resistant mutants. Mycoplasmas were grown at 37°C in Hayflick modified agar or broth medium supplemented with arginine (2).

Antibiotics and determination of MICs.

Antibiotics were purchased from the following manufacturers: NFX, Marion-Merrell-Dow, Levallois-Perret, France; PFX and SFX, Rhône-Poulenc-Rorer, Vitry-sur-Seine, France; OFX, Roussel Uclaf, Paris, France; CFX, Bayer-Pharma, Puteaux, France. MICs of different fluoroquinolones were determined by the metabolic inhibition method performed with 96-well microtiter plates as previously described (2).

Selection of fluoroquinolone-resistant mutants of M. hominis PG21.

Stepwise selection of OFX- and SFX-resistant mutants was performed by plating approximately 2 × 107 color-changing units of strain PG21 onto Hayflick modified agar medium containing various concentrations of OFX or SFX. After 48 h of incubation at 37°C, resistant colonies were grown in liquid medium containing the same fluoroquinolone concentration and used for the next round of selection. The frequency of mutation was determined as the number of colonies appearing on the plate with the antibiotic divided by the number of colonies in the inoculum.

DNA isolation.

Isolation of plasmid DNA was carried out with the Wizard Plus SV minipreps DNA purification system (Promega) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Large-scale preparation of mycoplasmal genomic DNA was performed as previously described (2). For small-scale preparation, mycoplasma cells from a 3-ml culture were collected by centrifugation and resuspended in 500 μl of STE buffer (100 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 1 mM EDTA). Cells were lysed by adding 25 μl of 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate. The lysate was heated at 65°C for 15 min and then treated with 100 μg of RNase for 30 min at 37°C. The DNA was further purified by phenol-chloroform deproteinization and ethanol-acetate precipitation and finally resuspended in 50 μl of sterile water.

PCR experiments.

Resistant mutants were examined by PCR and sequencing for changes in the QRDRs of gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE. PCRs were carried out with a Perkin Elmer Cetus thermal cycler with 100 ng of template DNA and each primer at 1 μM as described elsewhere (2). Oligonucleotides MH3 (5′-TATGG TATGAGTGAACTTGG-3′) and MH4 (5′-AATTAGGGAAACGTGATGGC-3′) previously described (2), were used to amplify a 349-bp gyrA fragment stretching from position 148 to position 496 (E. coli coordinates). A 223-bp gyrB fragment stretching from position 2099 to position 2321 was amplified with primers MH6 (5′-CTTCCTGGAAAATTAGCAGAC-3′) and MH7 (5′-CTGTGCCTAAGGCGTGAATCA-3′), which were designed from the published sequence of the M. hominis gyrB gene (20). A 5′ parC fragment was initially obtained from M. hominis PG21 by amplification with primers MH8 and MH10, deduced from the sequences of two conserved motifs, DGLKPVQ and GYATDIP, of S. aureus ParC (9). From the sequence of this amplified fragment, two primers MH11 (5′-TATTCAATGTGAAATTTAC-3′) and MH13 (5′-CAGAGTCATCAAAGTTTGG-3′), were used to amplify a 310-bp parC fragment from position 164 to position 477 (E. coli coordinates). In the case of parE, we initially amplified an M. hominis PG21 DNA fragment with primers based on the conserved motifs, TKDGGTH and ALPPLYK, of S. aureus ParE (9). From the nucleotide sequence of this PCR product, primers MH27 (5′-CTTTCAGGAAAATTAACT CCT-3′) and MH28 (5′-ATCAGTGTCAGCATCTGTCAT-3′) were used to amplify a 297-bp parE fragment from position 1252 to position 1545 (E. coli coordinates).

DNA sequencing and sequence analysis.

The parC and parE DNA fragments of M. hominis PG21 were cloned in E. coli by using pGEM-T Easy Vector System II (Promega). For each PCR product, the DNA inserts of three individual clones were sequenced on both strands. PCR products of quinolone-resistant strains were purified and directly sequenced on both strands as previously described (2).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequence data reported here will appear in the GenBank nucleotide sequence database under accession no. AF025688 (parC) and AF025687 (parE).

RESULTS

QRDRs of the gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE genes of M. hominis.

We have recently amplified and characterized two DNA fragments of M. hominis PG21 containing the GyrA and GyrB QRDRs (2). To characterize the ParC and ParE QRDRs, two pairs of degenerate primers were designed from the amino acid sequences of conserved regions of the GrlA (ParC) and GrlB (ParE) proteins of S. aureus (9) and used to amplify genomic DNA of M. hominis PG21. As expected, two amplification products of 435 and 297 bp were obtained, and their nucleotide sequences were determined (Fig. 1).

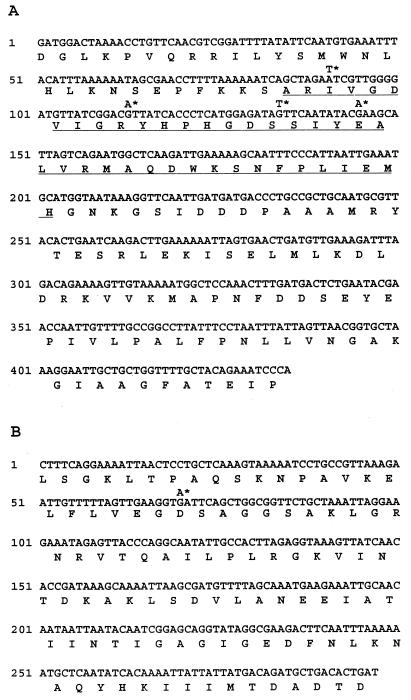

FIG. 1.

Nucleotide and amino acid sequences of the MH8-MH10-amplified DNA fragment of the parC gene (A) and the MH28-MH29-amplified DNA fragment of the parE gene (B) of M. hominis. The region corresponding to the gyrA QRDR of E. coli is underlined (A). Asterisks indicate the mutations found in quinolone-resistant mutants of M. hominis.

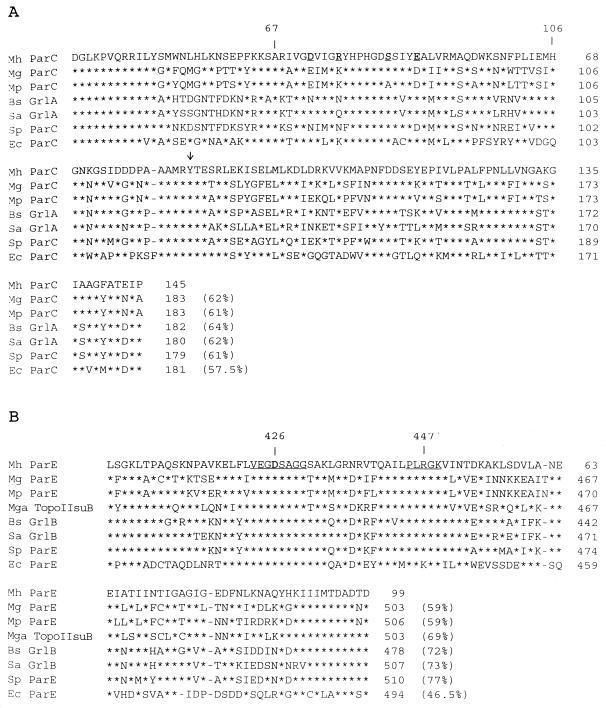

As shown in Fig. 2A and Table 1, the amino acid sequence of the 435-bp DNA fragment has a higher percentage of identity with homologous regions of ParC proteins from M. genitalium, Bacillus subtilis, S. aureus, and E. coli than with GyrA sequences of the same bacteria. Furthermore, His45 (E. coli numbering), which is specifically conserved in GyrA, and Gln42 (E. coli numbering), which is specifically conserved in ParC, are also present in the corresponding sequences of M. hominis (Fig. 2A) (31). The ParC sequence of M. hominis shares a higher degree of homology with those of the gram-positive bacteria B. subtilis, S. aureus, and S. pneumoniae than with that of the gram-negative bacterium E. coli (Fig. 2A). The ParC sequence of M. hominis was found to share 62% identical amino acids with that of M. genitalium and 61% with that of M. pneumoniae.

FIG. 2.

Alignment of the M. hominis (Mh) ParC (A) and ParE (B) sequences with those of M. genitalium (Mg) (10), M. pneumoniae (Mp) (16), B. subtilis (Bs) (27), S. aureus (Sa) (9), S. pneumoniae (Sp) (24), and E. coli (Ec) (18). The sequence of M. gallisepticum (Mga) topoisomerase II subunit B (28) also is included in comparisons in panel B. The arrow in panel A indicates the Tyr residue involved in DNA binding. The region corresponding to the E. coli GyrA QRDR (residues 67 to 106) (A) and positions 426 and 447, corresponding to the E. coli GyrB QRDR (B), are indicated. The ParE conserved motifs VEGDSAGG and PL(R/K)GK are underlined. Residues involved in quinolone resistance in M. hominis are underlined and in boldface type. Asterisks indicate identical amino acids, and dashes indicate gaps introduced to maximize similarities. Percentages of identical amino acids are in parentheses.

TABLE 1.

Sequence identities between the M. hominis ParC and ParE QRDRs and homologous regions of ParC, GyrA, ParE, and GyrB from various speciesa

| M. hominis protein | % Amino acid identity

|

|||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

M. genitalium

|

B. subtilis

|

S. aureus

|

S. pneumoniae

|

E. coli

|

||||||||||||||

| ParC | ParE | GyrA | GyrB | GrlA | GrlB | GyrA | GyrB | GrlA | GrlB | GyrA | GyrB | ParC | ParE | ParC | ParE | GyrA | GyrB | |

| ParC | 62 | 55 | 64 | 60 | 62 | 59 | 61 | 57.5 | 53 | |||||||||

| ParE | 59 | 51.5 | 72 | 60.5 | 73 | 59.5 | 77 | 46.5 | 53.5 | |||||||||

The data shown are from the following references: M. genitalium, 10; B. subtilis, 22 and 27, S. aureus, 9 and 21; S. pneumoniae, 24; E. coli, 1, 18, and 30. The ParC and GyrA sequences correspond to residues 36 to 181 and 39 to 183 of E. coli ParC and GyrA, respectively. The ParE and GyrB sequences correspond to residues 397 to 494 and 403 to 502 of E. coli ParE and GyrB, respectively.

In Fig. 2B and Table 1, the deduced amino acid sequence of the 297-bp fragment shows a higher percentage of identity with the ParE sequences of M. genitalium, B. subtilis, and S. aureus than with the GyrB counterparts of the same organisms. Like ParC, the M. hominis ParE sequence shares a higher percentage of identity with ParE (GrlB) of S. pneumoniae, S. aureus, and B. subtilis than with ParE of E. coli (Fig. 2B). Among members of the class Mollicutes, the ParE sequence of M. hominis was found to be more related to that of M. gallisepticum (69% identity), an animal mycoplasma, than to those of the human mycoplasmas M. genitalium and M. pneumoniae (59% identity).

From these sequence comparison data, we conclude that the 435- and 297-bp amplified DNA fragments correspond, respectively, to the QRDRs of the parC and parE genes of M. hominis.

Mutations of the gyrase and topoisomerase IV genes in OFX-resistant mutants of M. hominis.

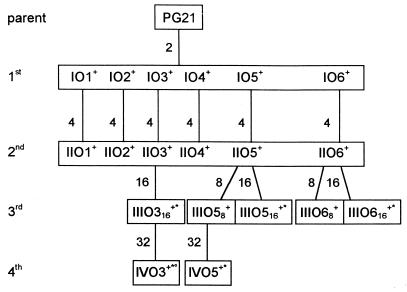

Spontaneous fluoroquinolone-resistant mutants of M. hominis were selected by plating reference strain PG21 onto agar medium containing various concentrations of OFX (Fig. 3). Thus, six independent groups of first- and second-step mutants (IO1 to IO6 and IIO1 to IIO6), five independent groups of third-step mutants (IIIO316, IIIO58, IIIO516, IIIO68, and IIIO616), and two independent groups of fourth-step mutants (IVO3 and IVO5) were obtained at frequencies ranging from 10−6 to 10−7.

FIG. 3.

Relationships among M. hominis PG21 and fluoroquinolone-resistant mutants IO1 to IVO5, selected by stepwise exposure to ofloxacin. First-, second-, third-, and fourth-step mutants are designated by the prefixs I, II, III, and IV, respectively. The numbers outside the boxes indicate the OFX concentrations (in micrograms per milliliter) used in the selection steps. The superscripts +, *, and ° indicate the presence of mutations in parE, gyrA, and parC, respectively (see Table 2).

For these OFX-resistant mutants, the MICs of five fluoroquinolones were determined and the QRDRs of GyrA, ParC, GyrB, and ParE were characterized. As shown in Table 2, first-step mutant group IO1 to IO6 shared the same low-level quinolone resistance, with a two- to fivefold increase in the MICs of all of the five fluoroquinolones tested. For each one of the first-step mutants, one single (G→A) base mutation leading to an Asp→Asn substitution was found in the parE gene. This substitution is located in a highly conserved region of ParE which represents the GyrB QRDR counterpart. The substituted aspartic acid corresponds to positions 426 and 420 in the E. coli GyrB and ParE numberings, respectively. For second-step mutant group IIO1 to IIO6, an additional twofold increase in the fluoroquinolone MICs was noted (Table 2). However, none of these second-step mutants carried additional changes in any of the four topoisomerase genes. After the third round of selection, gyrA mutations were detected in mutants IIIO316, IIIO516, and IIIO616, selected on the highest OFX concentration (16 μg/ml), while mutants IIIO58 and IIIO68, selected on 8 μg/ml, did not present any additional change. Mutants IIIO316, IIIO516, and IIIO616 all had, in addition to the parE mutation, the same C→T mutation, leading to a Ser83→Leu substitution in the GyrA protein. Interestingly, these mutants are characterized by a dramatically increased MIC of SFX (2 to 4 μg/ml), compared to IIIO58 and IIIO68 (0.1 μg/ml). The results suggest that in these OFX-selected mutants, the Ser83→Leu substitution in the GyrA protein is responsible for high-level resistance to SFX. None of the third-step mutants were found to carry mutations in parC or gyrB. Finally, studying fourth-step mutant group IVO3 and IVO5 revealed that mutant IVO5, derived from IIIO58, harbored an additional C→G mutation, leading to a Ser(TCA)-to-Trp(TGA) change (underlined) at position 83 of the GyrA QRDR. An increase in fluoroquinolone MICs was also observed for this mutant. In particular, the SFX MIC (4 μg/ml) was 40-fold higher than that (0.1 μg/ml) of mutant IIIO58, which has the parE mutation only. Surprisingly, the other fourth-step mutant, IVO3, displayed a peculiar quinolone resistance profile with no increase in the MICs of NFX and PFX, and two- and fourfold-decreased MICs of CFX and SFX, respectively. Sequence analyses of mutant IVO3 revealed that it carries an additional G→T mutation, leading to a Asp(GAT)-to-Tyr(TAT) substitution at position 69 of the ParC QRDR (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of OFX-selected mutants of M. hominisa

| Group and strain | MIC (μg/ml)

|

Mutationb in QRDR of:

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NFX | PFX | OFX | CFX | SFX | GyrA | GyrB | ParC | ParE | |

| Parent M. hominis PG21 | 8 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.01 | ||||

| First-step mutants IO1–IO6 | 16 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 0.02 | None | None | None | Asp426→Asn |

| Second-step mutants IIO1–IIO6 | 32 | 16 | 4 | 2 | 0.05 | None | None | None | Asp426→Asn |

| Third-step mutants | |||||||||

| IIIO316 | 64 | 16 | 32 | 16 | 4 | Ser83→Leu | None | None | Asp426→Asn |

| IIIO58 | 32 | 16 | 8 | 2 | 0.1 | None | None | None | Asp426→Asn |

| IIIO516 | 64 | 16 | 32 | 16 | 2 | Ser83→Leu | None | None | Asp426→Asn |

| IIIO68 | 32 | 16 | 8 | 2 | 0.1 | None | None | None | Asp426→Asn |

| IIIO616 | 32 | 16 | 32 | 8 | 2 | Ser83→Leu | None | None | Asp426→Asn |

| Fourth-step mutants | |||||||||

| IVO3 | 64 | 16 | 32 | 8 | 1 | Ser83→Leu | None | Asp69→Tyr | Asp426→Asn |

| IVO5 | 64 | 32 | 32 | 16 | 4 | Ser83→Trp | None | None | Asp426→Asn |

Laboratory strains IO1 to IVO5 were derived from parent wild-type strain PG21 by stepwise selection.

M. hominis GyrA, ParC, and ParE residues are numbered in accordance with the E. coli GyrA, ParC, and GyrB coordinates.

The data presented in Table 2 indicate that M. hominis mutants selected stepwise for OFX resistance acquired mutations first in topoisomerase IV (ParE) and that high-level resistance to OFX was associated with additional mutations in gyrase (GyrA).

GyrA and ParC mutations in stepwise-selected SFX-resistant mutants of M. hominis.

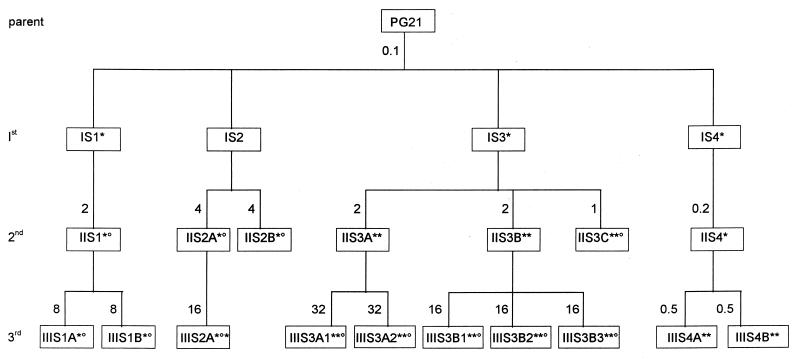

To assess the possibility that quinolones have different primary targets within the same species, M. hominis mutants were selected stepwise for resistance to SFX. The scheme for selection of SFX-resistant mutants is summarized in Fig. 4. By following this procedure, four independent sets of first-step mutants and five independent sets of second- and third-step mutants were obtained with mutation frequencies ranging from 10−6 to 3 × 10−6. For these SFX-resistant strains, the MICs of five fluoroquinolones (NFX, PFX, OFX, CFX, and SFX), as well as the status of the QRDRs of their gyrA, parC, gyrB, and parE genes, were determined (Table 3).

FIG. 4.

Relationships among M. hominis PG21 and fluoroquinolone-resistant mutants IS1 to IIIS4B, selected by stepwise exposure to SFX. First-, second-, and third-step mutants are designated by the prefixes I, II, and III, respectively. The numbers outside the boxes indicate the SFX concentrations (in micrograms per milliliter) used in the selection steps. The superscripts * and ° indicate the presence of mutations in gyrA and parC, respectively (see Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Characteristics of SFX-selected mutants of M. hominisa

| Group and strain | MIC (μg/ml)

|

Mutation(s)b in QRDR of:

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NFX | PFX | OFX | CFX | SFX | GyrA | GyrB | ParC | ParE | |

| Parent M. hominis PG21 | 4 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.02 | ||||

| First-step mutants | |||||||||

| IS1 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.5 | Ser83→Leu | None | None | None |

| IS2 | 4 | 2 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.1 | None | None | None | None |

| IS3 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | Ser84→Trp | None | None | None |

| IS4 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.1 | Ser84→Trp | None | None | None |

| Second-step mutants | |||||||||

| IIS1 | 16 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 4 | Ser83→Leu | None | Glu84→Lys | None |

| IIS2A | 8 | 4 | 16 | 16 | 4 | Ser83→Leu | None | Glu84→Lys | None |

| IIS2B | 8 | 4 | 16 | 16 | 4 | Ser83→Leu | None | Glu84→Lys | None |

| IIS3A | 32 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 4 | Ser84→Trp, Ser83→Leu | None | None | None |

| IIS3B | 32 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 4 | Ser84→Trp, Ser83→Leu | None | None | None |

| IIS3C | 8 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | Ser84→Trp, Ser83→Leu | None | Arg73→His | None |

| IIS4 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0.2 | Ser84→Trp | None | None | None |

| Third-step mutants | |||||||||

| IIIS1A | >128 | 32 | 64 | 64 | 16 | Ser83→Leu | None | Glu84→Lys | None |

| IIIS1B | >128 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 16 | Ser83→Leu | None | Glu84→Lys | None |

| IIIS2A | 64 | 8 | 16 | 16 | 16 | Ser83→Leu, Ser84→Trp | None | Glu84→Lys | None |

| IIIS3A1 | 128 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 32 | Ser84→Trp, Ser83→Leu | None | Glu84→Lys | None |

| IIIS3A2 | 128 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 32 | Ser84→Trp, Ser83→Leu | None | Glu84→Lys | None |

| IIIS3B1 | 128 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 16 | Ser84→Trp, Ser83→Leu | None | Glu84→Lys | None |

| IIIS3B2 | 128 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 16 | Ser84→Trp, Ser83→Leu | None | Glu84→Lys | None |

| IIIS3B3 | 128 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 32 | Ser84→Trp, Ser83→Leu | None | Glu84→Lys | None |

| IIIS4A | 16 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 2 | Ser84→Trp, Ser83→Leu | None | None | None |

| IIIS4B | 32 | 16 | 4 | 8 | 2 | Ser84→Trp, Ser83→Leu | None | None | None |

Laboratory strains IS1 to IIIS4B were derived from parent wild-type strain PG21 by stepwise selection.

M. hominis GyrA and ParC residues are numbered in accordance with the E. coli GyrA and ParC coordinates.

Three of the four first-step mutants, IS1, IS3, and IS4, have a mutation in the GyrA QRDR. Mutant IS1 was found to carry a Ser(TCA)-to-Leu(TTA) change at position 83, while IS3 and IS4 had a Ser(TCA)-to-Trp(TGA) change at position 84. Mutants IS1 and IS3 exhibited 2- to 4-fold-increased MICs of NFX, PFX, OFX, and CFX and, interestingly, a 25-fold increase in the MIC of SFX (0.5 μg/ml). However mutant IS4, which shares the same Ser84→Trp change as IS3, exhibited only a fivefold increase in the MIC of SFX (0.1 μg/ml). Surprisingly, in mutant IS2, exhibiting twofold-increased MICs of PFX and CFX and, especially, a fivefold increased MIC of SFX (0.1 μg/ml), no mutation could be detected in the QRDR of any of the four topoisomerase genes.

At the second round of selection, mutant IIS1 carried an additional change of Glu(GAA)-to-Lys(AAA) at position 84 in the ParC QRDR. This mutation was associated with twofold-increased MICs of NFX, PFX, and CFX and four- and eightfold-increased MICs of OFX and SFX, respectively. Mutants IIS2A and IIS2B, derived from IS2, showed a significant increase in the MICs of OFX and CFX (16-fold) and of SFX (40-fold) but only twofold-increased MICs of NFX and PFX. In these two second-step mutants, both gyrA and parC mutations were detected. Mutants IIS2A and IIS2B both harbored a Ser83(TCA)-to-Leu(TTA) change in GyrA and a Glu84(GAA)-to-Lys(AAA) substitution in ParC. Among the three second-step mutants derived from IS3, two, IIS3A and IIS3B, exhibited the same quinolone resistance profile with two- to eightfold-increased MICs, and the same GyrA QRDR status, with an additional Ser(TCA)-to-Leu(TTA) change at position 83. The third one, IIS3C, exhibited only a twofold increase in the quinolone MICs, in spite of two additional changes of Ser83(TCA) to Leu(TTA) in GyrA and Arg73(CGT) to His(CAT) in ParC. Finally, the last second-step mutant, IIS4, exhibiting a twofold increase in the MICs of OFX and SFX, did not harbor any additional change in the QRDRs. However, it should be noted that the SFX concentration used for the selection of IIS4 (0.2 μg/ml) was only slightly higher than the MIC of SFX for parent strain IS4 (0.1 μg/ml).

All 10 third-step mutants that were examined carried at least two mutations, either both in the gyrA QRDR or one in gyrA and the other in parC. Mutants IIIS1A and IIIS1B, like parent strain IIS1, had a Ser83→Leu substitution in GyrA and a Glu84→Lys change in ParC. However, they exhibited 4- to 16-fold-increased MICs compared to the parent strain. In third-step mutant IIIS2A, which exhibited a fourfold-increased SFX MIC (16 μg/ml), an additional Ser(TCA)-to-Trp(TGA) change was detected at position 84 of the GyrA QRDR. All five third-step mutants, IIIS3A1 to IIIS3B3, harbored two alterations (Ser84→Trp and Ser83→Leu) in GyrA and one (Glu84→Lys) in ParC which was not detected in the IIS3A and IIS3B parent strains. These mutants exhibited 4- to 16-fold-increased MICs, depending on the fluoroquinolone tested. Finally, the high-level resistance to SFX (2 μg/ml) of mutants IIIS4A and IIIS4B, derived from IIS4, was found to be associated with the two Ser84→Trp and Ser83→Leu alterations in the GyrA QRDR. Interestingly, none of the 21 SFX-resistant mutants were found to carry mutations in the gyrB or parE gene.

To summarize, the data presented in Table 3 indicate that during stepwise selection of SFX-resistant mutants, mutations occurred first in the gyrA gene, prior to those in parC.

ParC and ParE mutations in eight multistep-selected resistant strains of M. hominis PG21.

In previous studies, eight CFX-, NFX-, OFX-, and PFX-resistant mutants of M. hominis were selected after 12 passages in liquid medium containing subinhibitory concentrations of quinolones. The MICs of five fluoroquinolones for these mutants were determined, and the gyrA and gyrB QRDRs of every mutant were characterized (2). Four of them, N3, N7, O7, and O9, harbored a Ser83→Leu substitution in GyrA, whereas the other four (C1, C6, P1, and P4) did not. None of the eight mutants was found to carry mutations in GyrB. Interestingly, CFX-resistant strains C1 and C6 and PFX-resistant strains P1 and P4 exhibited a lower level of quinolone resistance, especially SFX resistance, than NFX- and OFX-resistant strains N3, N7, O7, and O9 carrying the GyrA mutation. To further characterize these mutants, we have now examined the status of the ParC and ParE QRDRs (Table 4). A G→T mutation, leading to a Ser→Ile substitution at position 80, was detected in the ParC QRDR of O7, O9, P1, and P4. Also, a G→A mutation, leading to an Asp→Asn change at position 426 (E. coli gyrB numbering), was detected in the ParE QRDR of C1, C6, N3, and N7. Thus, strains O7 and O9, exhibiting the highest SFX MIC (4 μg/ml), have two mutations, not only a Ser83→Leu substitution in GyrA but, in addition, a Ser80→Ile change in the ParC QRDR. Strains N3 and N7 (SFX MIC of 1 μg/ml) also harbored two mutations, the Ser83→Leu substitution in GyrA and the Asp426→Asn change in the ParE QRDR.

TABLE 4.

Characteristics of eight multistep fluoroquinolone-resistant mutants of M. hominisa

| M. hominis PG21 passage | Mutant | MIC (μg/ml)

|

Mutationb in QRDR of:

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NFX | PFX | OFX | CFX | SFX | GyrA | GyrB | ParC | ParE | ||

| Before passage | 8 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.01 | |||||

| After 12 passages in: | ||||||||||

| CFX | C1 | 64 | 32 | 16 | 16 | 0.2 | None | None | None | Asp426→Asn |

| C6 | 64 | 32 | 16 | 16 | 0.5 | None | None | None | Asp426→Asn | |

| NFX | N3 | 128 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 1 | Ser83→Leu | None | None | Asp426→Asn |

| N7 | 128 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 1 | Ser83→Leu | None | None | Asp426→Asn | |

| OFX | O7 | 128 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 4 | Ser83→Leu | None | Ser80→Ile | None |

| O9 | 128 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 4 | Ser83→Leu | None | Ser80→Ile | None | |

| PFX | P1 | 128 | 32 | 16 | 4 | 0.05 | None | None | Ser80→Ile | None |

| P4 | 128 | 32 | 16 | 4 | 0.05 | None | None | Ser80→Ile | None | |

From reference 2.

M. hominis GyrA, ParC, and ParE residues are numbered in accordance with the E. coli GyrA, ParC, and GyrB coordinates.

The data in Table 4, for mutants that were subjected to multistep selection for resistance to CFX, OFX, or PFX, as well as the data of Table 2, for mutants that were selected stepwise for resistance to OFX, indicate that, in these experiments, mutations in ParC and ParE occurred first, prior to those in GyrA.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we have used degenerate primers, designed from consensus amino acid motifs, to amplify and characterize the QRDRs of the parC and parE genes of M. hominis. In agreement with the phylogenetic origin of mollicutes (33), the ParC and ParE QRDRs of M. hominis, like the GyrA QRDR (2), showed a higher percentage of identity with the ParC and ParE QRDRs of the gram-positive bacteria B. subtilis, S. aureus, and S. pneumoniae than with those of E. coli. Within the class Mollicutes, the sequence of the ParE QRDR of M. hominis was found to be more closely related to that of M. gallisepticum, an animal mycoplasma, than to those of the human mycoplasmas M. pneumoniae and M. genitalium.

Following characterization of the QRDRs of gyrA and gyrB and the parC and parE genes of M. hominis (2, this study), several experiments were conducted to study targeting of DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV by fluoroquinolones. We have first characterized the QRDRs of the gyrA, parC, gyrB, and parE genes in M. hominis mutants selected stepwise for resistance to OFX. The results showed that stepwise selection of M. hominis for OFX resistance involves separate sequential mutations in topoisomerase IV and gyrase. A ParE mutation, the Asp426→Asn substitution, was associated with the first step of resistance to OFX, with low-level resistance. In contrast, GyrA mutations occurred in the third- and the fourth-step mutants exhibiting high-level resistance to fluoroquinolones. Thus, the primacy of ParE mutations over those in GyrA strongly suggests that topoisomerase IV is the primary target of OFX in M. hominis.

Recent studies with S. pneumoniae indicated that different quinolones can have different targets in the same bacterial species (25). To determine the situation in M. hominis, we also characterized mutants which were selected stepwise for resistance to SFX. In contrast to OFX-resistant mutants, most of the first-step SFX-resistant mutants harbored a change in the GyrA QRDR, while ParC mutations were detected only in second- and third-step mutants. These results indicate that, in M. hominis, as in S. pneumoniae (25), DNA gyrase is the primary target of SFX.

In previous studies, eight quinolone-resistant M. hominis mutants were obtained by multistep selection (2). Among these, NFX- and OFX-resistant mutants carried a Ser83→Leu mutation in GyrA, whereas CFX- and PFX-resistant mutants did not. Further characterization of these eight mutants revealed that they carried mutations in ParE, GyrA and ParE, GyrA and ParC, or ParC, depending on the fluoroquinolone used for selection, i.e., CFX, NFX, OFX, or PFX, respectively. The data presented in Table 4 suggest that topoisomerase IV is the primary target of CFX and PFX, since mutations in ParE (CFX-resistant mutants) or ParC (PFX-resistant mutants), but not in GyrA or GyrB, were detected. Interestingly, OFX-resistant mutants were found to harbor a Ser80→Ile ParC mutation which was not detected in OFX-resistant mutants selected stepwise on agar medium. Conversely, the Asp426→Asn ParE mutation, detected as early as the first step in OFX-resistant mutants selected on agar medium, was not found in the OFX-resistant mutants obtained by multistep selection in broth culture.

Regardless of the drug used for selection, hot spots for quinolone resistance have been found to be mutated in M. hominis mutants selected in vitro. Concerning the GyrA protein, amino acid Ser83 was replaced with a hydrophobic residue, i.e., leucine or tryptophan. A Ser84 change to the nonpolar residue tryptophan has never been described before. In E. coli (35), as well as in S. aureus (29), the amino acid at position 84 was replaced with a proline. Mutations in the ParC QRDRs of PFX-, OFX-, and SFX-resistant mutants of M. hominis yielded Ser→Ile and Glu→Lys amino acid changes at positions 80 and 84, respectively. Substitutions at these positions have been previously described in many fluoroquinolone-resistant isolates of other bacteria (3, 7, 8, 13, 15, 23). In contrast, two ParC substitutions seemed to be unique features of M. hominis mutants. One, Asp69→Tyr, was found in fourth-step OFX-resistant mutant IVO3 (Table 2), and the other, Arg73→His, was detected in second-step SFX-resistant mutant IIS3C (Table 3). It is noteworthy that no significant variation in cell growth was noticed between mutants IVO3 and IIS3C and their parental strains, suggesting that gyrase activity was not affected by these mutations. The fact that these mutants displayed unusual quinolone resistance patterns, in particular, that mutant IVO3 exhibited decreased CFX and SFX MICs, is not understood. The involvement of these unusual ParC mutations, Asp69→Tyr and Arg73→Lys, in quinolone resistance has to be confirmed. In contrast, the Asp426→Asn mutation in the ParE QRDR of CFX-, NFX-, and OFX-resistant mutants was detected at a position that was previously shown to be essential for quinolone resistance in the GyrB or ParE QRDR of various bacteria (17, 23, 26, 37).

Scrutinizing the data on stepwise-selected OFX- and SFX-resistant mutants of M. hominis revealed some peculiar features. In contrast with the thought that the stepwise selection procedure generates a single mutation for each selection step, SFX mutants IIS2A, IIS2B, and IIS3C (Table 3) have acquired two additional mutations in a single step. Similar results were obtained with CFX-selected mutants of S. pneumoniae (25, 31). However, since the resistant clones were grown in broth medium with the same concentration of antibiotic to ensure resistance, the possibility that the second mutation occurred just before replating cannot be excluded. Data in Tables 2 and 3 also showed that in all of the OFX second-step mutants, IIO1 to IIO6 (Table 2), and in SFX-resistant mutants IS2, IIIS1A, and IIIS1B (Table 3), the increase in the MICs did not correlate with the acquisition of new mutations in the GyrA or topoisomerase IV QRDR. In these cases, it is likely that other mechanisms of resistance are involved in providing the observed phenotype of these strains. Possibilities include additional mutations elsewhere in topoisomerase genes, a quinolone efflux system such as the gene norA described in S. aureus (36), or a multiple antibiotic resistance operon such as the mar operon of E. coli (14). The occurrence of such a mechanism in M. hominis mutants has not been investigated yet.

Interestingly, the cross-resistance profiles of SFX mutants (Table 3) and OFX mutants (Table 2) of M. hominis mirrored each other. The Ser83→Leu or Ser84→Trp GyrA mutations in IS1, IS3, and IS4 altered the MIC of OFX significantly less than the MIC of SFX. Conversely, the Asp426→Asn ParE substitution increased the OFX MIC significantly but not the SFX MIC. These observations are in good agreement with the fact that in M. hominis, SFX and OFX have different primary targets, gyrase for SFX and topoisomerase IV for OFX.

In E. coli, several studies have shown DNA gyrase to be the primary target of quinolones, with parC-mediated resistance being detectable only in gyrA mutants (15, 19). Inversely, topoisomerase IV was found to be the primary target in the gram-positive bacterium S. aureus (8, 9, 34). Similar results were described for CFX resistance in S. pneumoniae (23, 24, 31). However, recent studies have given evidence that such a dichotomy between gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria is not the rule. In S. pneumoniae, SFX was found to target primarily the DNA gyrase (25). However, in S. aureus, genetic (34) and biochemical (4) studies have shown that topoisomerase IV is the primary target of fluoroquinolones such as CFX, NFX, and SFX but not of OFX. Similarly, our results indicate that in M. hominis, DNA gyrase is the primary target of SFX whereas topoisomerase IV is the primary target of PFX, OFX, and CFX. From these studies, the fact that the quinolone structure can determine relative topoisomerase targeting of quinolones has now been established. Therefore, the use of a single quinolone as the leader compound for susceptibility testing and resistance studies can be misleading, since quinolones interact differently with the gyrase-DNA complex.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Emmanuelle Cambau for helpful comments and critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adachi T M, Mizuuchi M, Robinson E A, Apella E, O’Dea M H, Gellert M, Mizuuchi K. DNA sequence of the Escherichia coli gyrB gene: application of a new sequencing strategy. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:771–784. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.2.771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bébéar C M, Bové J M, Bébéar C, Renaudin J. Characterization of Mycoplasma hominis mutations involved in resistance to fluoroquinolones. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:269–273. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.2.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belland R J, Morrison S G, Ison C, Huang W H. Neisseria gonorrhoeae acquires mutations in analogous regions of gyrA and parC in fluoroquinolone-resistant isolates. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:371–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blanche F, Cameron B, Bernard F-X, Maton L, Manse B, Ferrero L, Ratet N, Lecoq C, Goniot A, Bisch D, Crouzet J. Differential behaviors of Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli type II DNA topoisomerases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2714–2720. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.12.2714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breines D M, Ouabdesselam S, Ng E Y, Tankovic J, Shah S, Soussy C J, Hooper D C. Quinolone resistance locus nfxD of Escherichia coli is a mutant allele of the parE gene encoding a subunit of topoisomerase IV. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:175–179. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.1.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cullen M E, Wyke A W, Kuroda R, Fisher L M. Cloning and characterization of a DNA gyrase A gene from Escherichia coli that confers clinical resistance to 4-quinolones. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33:886–894. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.6.886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deguchi T, Fukuoka A, Yasuda M, Nakano M, Ozeki S, Kanematsu E, Nishino Y, Ishihara S, Ban Y, Kawada Y. Alterations in the GyrA subunit of DNA gyrase and the ParC subunit of topoisomerase IV in quinolone-resistant clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:699–701. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.3.699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferrero L, Cameron B, Crouzet J. Analysis of gyrA and grlA mutations in stepwise-selected ciprofloxacin-resistant mutants of Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1554–1558. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.7.1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrero L, Cameron B, Manse B, Lagneaux D, Crouzet J, Framechon A, Blanche F. Cloning and primary structure of Staphylococcus aureus DNA topoisomerase IV: a primary target of fluoroquinolones. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:641–653. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fraser C M, Gocayne J D, White O, Adams M D, Clayton R A, Fleischmann R D, Bult C J, Kerlavage A R, Sutton G, Kelley J M, Fritchman J L, Weidman J C, Small K V, Sandusky M, Fuhrmann J, Nguyen D, Utterback T R, Saudek D M, Phillips C A, Merrick J M, Tomb J F, Dougherty B A, Bott K F, Hu P-C, Lucier T S, Peterson S N, Smith H O, Hutchison III C A, Venter J C. The minimal gene complement of Mycoplasma genitalium. Science. 1995;270:397–403. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5235.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gellert M, Mizuuchi K, O’Dea M H, Itoh T, Tomisawa J. Nalidixic acid resistance: a second genetic character involved in DNA gyrase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:4772–4776. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.11.4772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gellert M, Mizuuchi K, O’Dea M H, Nash H A. DNA gyrase: an enzyme that introduces superhelical turns into DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1976;73:3872–3876. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.11.3872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Georgiou M, Munoz R, Roman F, Canton R, Gomez-Lus R, Campos J, De La Campa A G. Ciprofloxacin-resistant Haemophilus influenzae strains possess mutations in analogous positions of GyrA and ParC. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1741–1744. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.7.1741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldman J D, White D G, Levy S B. Multiple antibiotic resistance (mar) locus protects Escherichia coli from rapid cell killing by fluoroquinolones. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1266–1269. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.5.1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heisig P. Genetic evidence for a role of parC mutations in development of high-level fluoroquinolone resistance in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:879–885. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.4.879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Himmelreich R, Hilbert H, Plagens H, Pirkl E, Li B C, Herrmann R. Complete sequence analysis of the genome of the bacterium Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:4420–4429. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.22.4420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ito H, Yoshida H, Bogaki-Shonai M, Niga T, Hattori H, Nakamura S. Quinolone resistance mutations in the DNA gyrase gyrA and gyrB genes of Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:2014–2023. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.9.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kato J, Nishimura Y, Imamura R, Niki H, Hiraga S, Suzuki H. New topoisomerase essential for chromosome segregation in E. coli. Cell. 1990;63:393–404. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90172-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khodursky A B, Zechiedrich E L, Cozzarelli N R. Topoisoerase IV is a target of quinolones in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:11801–11805. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.25.11801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ladefoged S A, Christiansen G. Sequencing analysis reveals a unique gene organization in the gyrB region of Mycoplasma hominis. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5835–5842. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.18.5835-5842.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Margerrison E E C, Hopewell R, Fisher L M. Nucleotide sequence of the Staphylococcus aureus gyrB-gyrA locus encoding the DNA gyrase A and B proteins. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1596–1603. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.5.1596-1603.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moriya S, Ogasawara N, Yoshikawa H. Structure and function of the region of the replication origin of the Bacillus subtilis chromosome. III. Nucleotide sequence of some 10,000 base pairs in the origin region. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13:2251–2265. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.7.2251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pan X-S, Ambler J, Mehtar S, Fisher L M. Involvement of topoisomerase IV and DNA gyrase as ciprofloxacin targets in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2321–2326. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.10.2321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pan X-S, Fisher L M. Cloning and characterization of the parC and parE genes of Streptococcus pneumoniae encoding topoisomerase IV: role in fluoroquinolone resistance. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4060–4069. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.14.4060-4069.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pan X-S, Fisher L M. Targeting of DNA gyrase in Streptococcus pneumoniae by sparfloxacin: selective targeting of gyrase or topoisomerase IV by quinolones. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:471–474. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.2.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perichon B, Tankovic J, Courvalin P. Characterization of a mutation in the parE gene that confers fluoroquinolone resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1166–1167. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.5.1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rose M, Entian K-D. New genes in the 170° region of the Bacillus subtilis genome encode DNA gyrase subunits, a thioredoxin, a xylanase and an amino acid transporter. Microbiology. 1996;142:3097–3101. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-11-3097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Skamrov A V, Feoktistova E S, Bibilashvili R S. Cloning and analysis of the nucleotide sequence of the segment in the Mycoplasma gallisepticum genome containing the gene for the ATP-binding subunit of DNA topoisomerase type II (topIIB) Mol Biol. 1995;29:308–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sreedharan S, Oram M, Jensen B, Peterson L R, Fisher L M. DNA gyrase gyrA mutations in ciprofloxacin-resistant strains of Staphylococcus aureus: close similarity with quinolone resistance mutations in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:7260–7262. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.12.7260-7262.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swanberg S L, Wang J C. Cloning and sequencing of the Escherichia coli gyrA gene coding for the A subunit of DNA gyrase. J Mol Biol. 1987;197:729–736. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90479-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tankovic J, Perichon B, Duval J, Courvalin P. Contribution of mutations in gyrA and parC genes to fluoroquinolone resistance of mutants of Streptococcus pneumoniae obtained in vivo and in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2505–2510. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.11.2505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Waites K B, Duffy L B, Schmid T, Crabb D, Pate M S, Cassell G H. In vitro susceptibilities of Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Mycoplasma hominis, and Ureaplasma urealyticum to sparfloxacin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:1181–1185. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.6.1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Woese C R. Bacterial evolution. Microbiol Rev. 1987;51:221–271. doi: 10.1128/mr.51.2.221-271.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamagashi J-I, Kojima T, Oyamada Y, Fujimoto K, Hattori H, Nakamura S, Inoue M. Alterations in the DNA topoisomerase IV grlA gene responsible for quinolone resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1157–1163. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.5.1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoshida H, Bogaki M, Nakamura M, Nakamura S. Quinolone resistance-determining region in the DNA gyrase gyrA gene of Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:1271–1272. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.6.1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoshida H, Bogaki M, Nakamura M, Ubukata K, Konno M. Nucleotide sequence and characterization of the Staphylococcus aureus norA gene, which confers resistance to quinolones. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6942–6949. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.12.6942-6949.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoshida H, Bogaki M, Nakamura M, Yamanaka L M, Nakamura S. Quinolone resistance-determining region in the DNA gyrase gyrB gene of Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:1647–1650. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.8.1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]