Abstract

Background

Malnutrition is a global health issue that affects all age groups and regions. The integration of malnutrition screening into community pharmacy practices help address malnutrition. Community pharmacies, with their accessibility and reach, are well-suited to provide essential malnutrition screening services, contributing to improved public health outcomes.

Objective

The research objectives encompass evaluating community pharmacists' knowledge, screening proficiency, range of malnutrition services provided, and competence in identifying patients at risk of malnutrition.

Method

The study used a cross-sectional design to gather data from CPs in Kaduna State, Nigeria, using an online, self-administered, semi-structured questionnaire. Convenience sampling was used, and the data were evaluated using descriptive statistics.

Results

Eighty five percent of the 80 CPs who took the survey and provided responses practiced in urban areas. Approximately 37% and 18% of pharmacists, respectively, had a good and fair understanding of therapeutic nutrition. Additionally, while 33% of pharmacists provided nutritional advice in response to a prescription, 41% of them did so based on specific observations. Patients with severe dehydration (28%), infants and children with growth impairment (25%), and neonates with low birth weight (20%) were identified as high-risk. A little over 30% of survey participants thought patients should have both dietary and medical treatment. Additionally, 34% of pharmacists reported nutritional supplements had a positive impact on public health, while 28% believed they should be sold in pharmacies under pharmacist supervision.

Conclusion

Study findings revealed knowledge gaps in addressing malnutrition among CPs. While they play a significant role, improvements are needed in understanding therapeutic nutrition and providing advice. Identifying high-risk patients and recognizing the value of nutritional supplements can enhance public healthcare services and patient well-being.

1. Introduction

Malnutrition is a significant global health challenge, affecting people across all age groups and regions.1 It encompasses various forms, including undernutrition, overnutrition (obesity), and micronutrient deficiencies. Poverty amplifies the risk of, and risks from, malnutrition. People who are poor are more likely to be affected by different forms of malnutrition.1 Malnutrition increases health care costs, reduces productivity, and slows economic growth, which can perpetuate a cycle of poverty and ill-health.1

Child malnutrition is a pressing global health issue, with an estimated 19 million preschool-aged children severely malnourished, predominantly in the World Health Organization (WHO) South-East Asia and African regions.2 This condition not only poses a severe risk to childhood morbidity and mortality but also has long-term implications, including poor intellectual growth and suboptimal work capacity. Shockingly, dietary-related factors contribute to 35% of the 7.6 million deaths among children under the age of 5 each year, with 4.4% of these fatalities specifically attributed to severe wasting.2 Child malnutrition, particularly severe acute malnutrition, remains a significant contributor to child mortality worldwide.1

Moreover, malnutrition is not limited to children; one in every two older adults faces the risk of malnutrition. Regardless of age or socio-economic status, malnutrition occurs when the body does not receive the necessary balance of calories and nutrients to maintain health.3 In essence, it can affect anyone, and the prevalence of malnutrition in older adults is compounded by age-related factors.3 The global concern surrounding nutrition is evident in the staggering impact of unhealthy dietary standards on public health. According to WHO, these standards play a significant role in the prevalence of non-communicable diseases, ultimately impeding societal growth and development.2 Africa, a continent particularly affected by this challenge, faces a critical issue with less than half of its healthcare facilities providing standardized malnutrition screening and counseling services.4

In the Joint International Pharmacy Federation (FIP)/WHO guidelines, pharmacists are recognized as having a responsibility to promote, evaluate, and enhance community health.5 Community Pharmacists (CPs) occupy a unique position, characterized by their accessibility without the need for prior appointments, making them ideal sources of health advice and counseling for the community.6

Utilizing nutritional counseling in conjunction with medication therapy provides an excellent opportunity to offer dietary guidance and suggest essential dietary supplements.7 As the consumption of supplements and dietary additives surges globally, pharmacies are major providers of these products, emphasizing the critical role of pharmacists in advising patients on their safe use.8

Despite dietitians' specialization in nutritional guidance, community pharmacies are often the first point of contact for patients concerned about weight management.9 This trend necessitates a focus on the role of CPs in enhancing nutritional support.

While similar studies have been conducted in countries like the United Kingdom, Egypt, and Northern Ireland,7,9,10 no reports have emerged from West Africa, let alone Nigeria. Targeted populations, including geriatric, pediatric, and medically compromised patients, stand to benefit from these services, potentially elevating the standards of healthcare pharmacy practice.11

The integration of malnutrition management into community pharmacy practice represents a recent endeavor to expand primary care services.11 Given the rising use of nutritional and dietary supplements by patients worldwide, community pharmacies serve as vital sources of these products. Therefore, it is imperative that CPs possess the knowledge and expertise to guide patients safely in their utilization.

Malnutrition transcends national boundaries, affecting both industrialized and developing nations and resulting in poor health outcomes, including increased morbidity and mortality, hindered cognitive growth, and compromised immune function.12 Consequently, CPs play a pivotal role in identifying, evaluating, and treating malnutrition within the communities they serve, making it imperative to assess their knowledge, skills, and competency in this domain.

In this context, our study objectives were to evaluate the competency of CPs in identifying and managing malnourished patients in Kaduna State, Nigeria. By identifying potential gaps in their knowledge and skills, we seek to contribute to the improvement of patient outcomes.

2. Method

An online, self-administered, semi-structured questionnaire was employed in this cross-sectional study. The questionnaire comprised 26 open-ended and closed-ended questions spread across five sections. Data were collected from January to April 2023, focusing on community pharmacists (CPs) in Kaduna State, Nigeria. Eligible participants were actively practicing CPs in Kaduna State, regardless of their primary working area, and were required to hold a minimum qualification of a Bachelor's degree in pharmacy (B. Pharm).

The sample size was determined based on established data, indicating a total population of 175 CPs in Kaduna State in 2016.13 To efficiently gather participants, we employed a convenience sampling approach. Initially targeting a sample size of 120 with a 95% confidence level and 5% confidence interval using an online survey calculator,14 accessibility constraints led to a final eligible participant pool of only 80 CPs.

The sample frame consisted of graduates, postgraduates, Ph.D. holders, post-doctoral fellows, and professors working as CPs. These pharmacists were conveniently selected from both urban and rural areas of Kaduna State, Nigeria.

2.1. Data collection

The questionnaire was designed to assess the malnutritional services offered by CPs by collecting detailed information on their knowledge, attitudes, and practice in addressing malnutrition. During the development process, the following steps were taken:

Literature review: The questionnaire was developed following an extensive review of relevant literature on malnutrition management, community pharmacist roles, and the use of the most modern assessment techniques.7., 8, 9, 10.

Content Validation: To ensure the validity and reliability of the survey tool, a pilot test was conducted with a group of 10 CPs who were excluded from the main study. Their feedback was collected to identify any ambiguities, omissions, or irrelevant questions, and necessary adjustments were made based on their input. Additionally, as part of the pilot study, expert opinions were sought using face and content validity. Experts in the fields of community pharmacy practice, nutrition, and healthcare were consulted to confirm the questionnaire's applicability, validity, and reliability. Their valuable feedback contributed to the refinement of the questions, ensuring comprehensive coverage of all essential aspects of malnutrition management.

The survey was divided into five sections: demographic information, basic knowledge, attitudes, practices, and challenges. It provided a thorough assessment of participants' knowledge, beliefs, and practices about malnutrition management. There were a variety of question types in the survey, including open-ended, closed-ended, and Likert-scale items.

Section A, demographics data: CPs age, gender, educational background, areas of practice, employment history, and place of practice were all gathered in the demographic section.

Section B, Basic Knowledge: The questions in this section assessed the CPs' knowledge related to therapeutic nutrition, micro and macro nutrients, food and drug interactions, and dietary supplements. Participants were asked to describe their understanding of each aspect.

Section C, Attitude: This section aimed to assess CPs' attitudes toward therapeutic nutrition and dietary supplements. Participants were asked to indicate their opinions on the role of pharmacists in nutritional assessment and the importance of nutritional advice in patient care.

Section D, Practice: The practice section examined the participants' current practices related to malnutrition management. Questions were included to determine whether they screened patients for malnutrition, assessed nutritional risk, and provided nutritional advice and services.

Section E, Challenges and Barriers: The final section sought to identify barriers that hindered CPs from providing nutritional services effectively. Participants were asked to express their opinions on the challenges they faced and strategies to overcome them.

Google Forms were used for data gathering. The forms were created in a logical sequence with multiple question types, ensuring a smooth flow and easy interpretation of responses. The survey link was distributed to target respondents via several channels (pharmacist-only social media platforms such as WhatsApp and Facebook), and participants could save their progress and return to complete the poll later. The form also collected data in real time and saved it in a Google Sheets file. Validation standards assured correct answers, as well as data security and privacy.

The data collected from Google were exported to Microsoft Excel for scrubbing. Statistical Package for Social Sciences Version 22 (IBM SPSS Version 22) was used for analysis. Categorical variables were analyzed using descriptive statistics, and inferences were made.

Due to nature of questionnaire administration using email addresses, there was no accounting for non-response error, missing or multiple entries.

2.2. Ethical considerations

To protect participants' privacy and ensure data integrity, we maintained pseudo-anonymity and confidentiality by only collecting their email addresses. This was done to prevent duplicate entries, as Google Forms requires email addresses for this purpose.

Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Kaduna Ministry of Health for ethics, Ref: MOH/ADM/744/VOL 1/1155 (NHREC/17/03/2018).

3. Results

The study included 89 CPs, only 80 of whom were from Kaduna State, with a response rate of 66.6%. Approximately 76 (95%) of CPs worked in cities, 4 (5%) in rural regions, and 56% and 7.5% had 5 years and over 21 years of professional experience, respectively (Table 1). All of the participants agreed that pharmacists should have a role in nutritional assessment.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of CPs.

| Demographic Variables | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| What age group do you fall under? | 21–30 years | 29 | 36.2 |

| 31–40 years | 40 | 50.0 | |

| 41–50 years | 5 | 6.3 | |

| 51 and above | 6 | 7.5 | |

| Gender | Female | 33 | 41.3 |

| Male | 47 | 58.7 | |

| Educational level (highest completed) | Post-doctoral | 1 | 1.3 |

| Post- graduate MSc | 28 | 35.0 | |

| Graduate B. Pharm | 48 | 60.0 | |

| Graduate Pharm. D | 3 | 3.7 | |

| Work experience | 0–5 years | 46 | 57.5 |

| 11–15 years | 5 | 6.3 | |

| 16–20 years | 2 | 1.3 | |

| 21 and above | 6 | 4.0 | |

| 6–10 years | 21 | 13.9 | |

| Location of practice | Rural | 4 | 5.0 |

| Urban | 76 | 95.0 | |

| Do you think pharmacist have any role in nutritional assessment? | YES | 80 | 100.0 |

| Sources of Nutritional Information Frequencies | Undergraduate | 44 | 22.3% |

| Postgraduate | 12 | 6.1% | |

| Books and Journals | 47 | 23.9% | |

| Workshops and seminars | 35 | 17.8% | |

| Internet | 57 | 28.9% | |

| Recipe books | 1 | 0.5% | |

| Experiences with professional | 1 | 0.5% | |

⁎ B. Pharm: Bachelor of Pharmacy, Pharm. D: Doctor of Pharmacy.

3.1. Knowledge

The self-assessment of CPs using the six point Likert-scale, revealed that 20% of CPs had good knowledge of therapeutic nutrition, and 17% had fair knowledge. In terms of macro- and micronutrient knowledge, 19% and 15%, respectively, exhibited good and fair knowledge (Table 2). As shown in Fig. 1, 69% and 18% of respondents, respectively, defined therapeutic nutrition as the use of food to treat or prevent disease, and that it required a physician's prescription.

Table 2.

CPs knowledge of therapeutic nutrition, macro and micro nutrients.

| Knowledge | I don't know | Poor | Fair | Average | Good | Excellent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Describe your knowledge regarding the following: [Therapeutic nutrition (e.g. plan diet for Infants, elderly, diabetic patients etc.)] | 11 (7.3) | 11 (7.3) | 14 (19.3) | 11 (7.3) | 30 (19.9) | 3 (2) |

| Describe your knowledge regarding the following: [Micro and macro nutrients (Proteins, Amino acids, zinc, Iron etc.)] | 6 (4) | 7 (4.6) | 12 (7.9) | 20 (13.2) | 29 (19.2) | 6 (4) |

Fig. 1.

Knowledge of CPs on management of malnutrition.

3.2. Attitude

Respondents' attitudes toward therapeutic nutrition indicated that 30.8% agreed that most patients would receive a combination of both drug and nutritional advice.

About 15 % (14.7%) agreed that it was the role of a dietician and physician, while 41% of the CPs provided patients with nutritional advice based on certain observations (such as malnutrition and obesity). Approximately 33% gave nutritional advice, usually according to prescription (patients with diabetes, hypertension, and gout) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Attitude of CPs toward therapeutic nutrition.⁎

| Attitude Statements | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Attitude Toward Therapeutic Nutrition | It is part of pharmacists duties | 68 (32.2%) |

| It is the role of physician and dietician | 31 (14.7%) | |

| It is more important than drugs in some conditions | 47 (22.3%) | |

| Most times patients will be given a combination of nutritional and medicinal therapies | 65 (30.8%) | |

| Attitude Toward Dietary Supplements | It has a positive impact on public health | 73 (33.8%) |

| It should be dispensed according to the nutritionist or physician | 33 (15.3%) | |

| It should be sold in pharmacies under pharmacists supervision | 60 (27.8%) | |

| Price is important factor for recommending supplements to customers | 49 (22.7%) | |

| I don't know | 1 (0.5%) | |

| Nutritional Advice | Upon request | 45 (23.3%) |

| Depending on certain observation (malnutrition- obesity) | 78 (40.4%) | |

| Usually according to the prescription (patient with diabetes/HT/gout) | 66 (34.2%) | |

| Never/ None | 1 (0.5%) | |

| Others (When a patient presents with certain symptoms of deficiency, often to help them live healthy, also when patients have certain chronic conditions as SCD) | 3 (1.6%) | |

| I will get back to you | 1 (0.7%) | |

| Refer to a dietician | 16 (10.6%) | |

| Refer to a doctor | 1 (0.7%) | |

| Refer to a Nutritional centre | 9 (6%) | |

| Search for the required information | 53 (35.1%) | |

HT: Hypertension, SCD: Sickle Cell Disease.

3.3. Practice

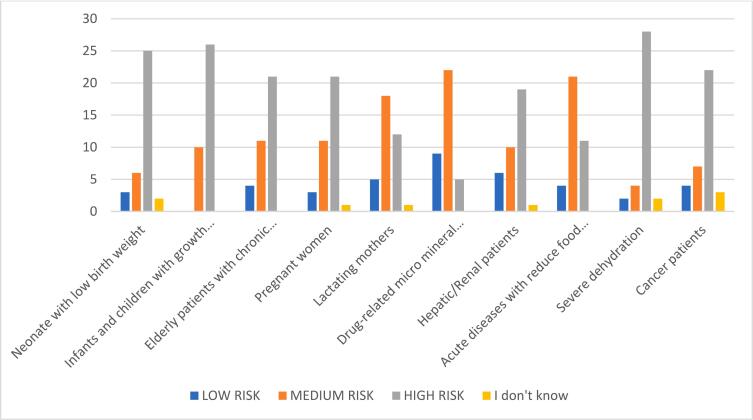

Fifty-five percent of CPs (55%, n = 44) screened patients for malnutrition, whereas 45% (n = 36) did not. Twenty one percent (n = 17) of patients with unexpected weight loss were accessed using body weight and Body Mass Index (BMI), whereas only 11% (n = 9) used laboratory data (PCV: Packed Cell Volume, FBC: Full Blood Count, Hb: Haemoglobin, etc.). Patients with severe dehydration (28%), infants and children with growth retardation (25%), and neonates with low birth weight (20%) were among those at high risk of malnutrition (Fig. 2). Diet-related cases were the most common nutritional concerns seen at community pharmacies (17.3%), and the services provided by CPs were primarily weight management for obese patients (21%), as well as macronutrient supplements (11.1%) (Table 4).

Fig. 2.

Risk assessment of patient for malnutrition.

Table 4.

Risk assessment of patients for malnutrition.

| VARIABLES | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Nutritional Assessment Methods | Assessing patient with Unintentional weight lost using body weight and BMI | 33 (20.9%) |

| Assessment of patients with Acute illness with risk of malnutrition (e.g. diarrhoea, vomiting) | 33 (20.9%) | |

| Patients with Reduce food intake | 24 (15.2%) | |

| Use of Laboratory investigations (FBC, PCV, Hb etc.) | 18 (11.4%) | |

| Assessment of patients Psychological state (e.g. stress, depression) | 22 (13.9%) | |

| Midarm upper arm Circumference Tape measurement for children | 28 (17.7%) | |

| Screening Patient for Malnutrition | Assessing patient with Unintentional weight lost using body weight and BMI | 33 (20.9%) |

| Assessment of patients with Acute illness with risk of malnutrition (e.g. diarrhoea, vomiting) | 33 (20.9%) | |

| Patients with Reduce food intake | 24 (15.2%) | |

| Use of Laboratory investigations (FBC, PCV, Hb etc.) | 18 (11.4%) | |

| Assessment of patients' Psychological state (e.g. stress, depression) | 22 (13.9%) | |

| Midarm upper arm Circumference Tape measurement for children | 28 (17.7%) | |

| Patients at risk of malnutrition? | Under nutrition | 28 (16.2%) |

| Over nutrition (such as Obesity) | 25 (14.5%) | |

| Diet-related diseases (diabetes, heart disease, stroke etc.) | 30 (17.3%) | |

| Dehydration | 26 (15.0%) | |

| Protein-Energy Malnutrition (Kwashiorkor and Marasmus) | 18 (10.4%) | |

| Iron deficiency Anaemia | 21 (12.1%) | |

| Vitamin deficiency | 25 (14.5%) | |

| Common Nutritional Cases Seen in Community | Under nutrition | 28 (16.2%) |

| Over nutrition (such as Obesity) | 25 (14.5%) | |

| Diet-related diseases (diabetes, heart disease, stroke etc.) | 30 (17.3%) | |

| Dehydration | 26 (15.0%) | |

| Protein-Energy Malnutrition (Kwashiorkor and Marasmus) | 18 (10.4%) | |

| Iron deficiency Anaemia | 21 (12.1%) | |

| Vitamin deficiency | 25 (14.5%) | |

| Services Provided by Community Pharmacists | weight management (for obese patients) | 33 (20.4%) |

| recommending ready to use therapeutic food | 19 (11.7%) | |

| rehydration solution for malnutrition | 28 (17.3%) | |

| Micronutrients | 18 (11.1%) | |

| lipid-based nutrients supplements | 9 (5.6%) | |

| Macro-nutrients supplements | 17 (10.5%) | |

| Referred to nearby nutritional centre | 16 (9.9%) | |

| Local food nutritional advise | 22 (13.6%) | |

| Category of Cases Managed by CPs | LOW RISK | 26 (45.6%) |

| MEDIUM RISK | 26 (45.6%) | |

| HIGH RISK | 5 (8.8%) | |

⁎ PCV: Packed Cell Volume, FBC: Full Blood Count, Hb: Haemoglobin.

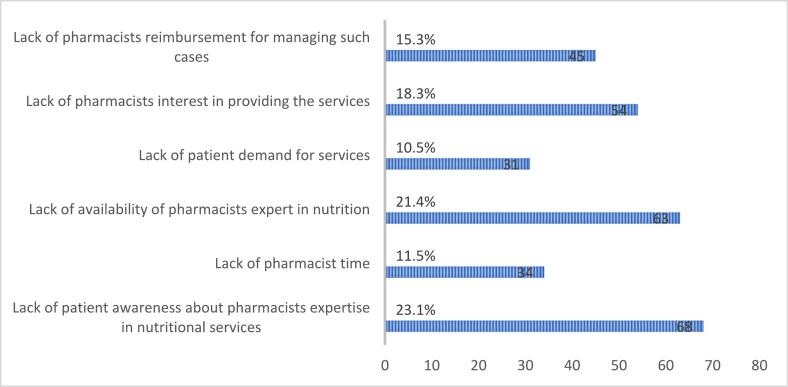

3.4. Barriers and solutions

Over 50% of the CPs (n = 40) identified the following barriers to providing nutritional services in community pharmacies: a lack of pharmacists' interest in providing the services, a lack of availability of pharmacists' experts in nutrition, and a lack of patient awareness about pharmacists' expertise in nutritional services (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

CPs' barriers to evaluating malnourished patients.

Furthermore, over 50% of CPs suggested solutions to overcome these challenges were: reimbursement strategies for providing these services, government or non-government support for community pharmacies; improving pharmacists communication skills; an established counseling area in community pharmacies for privacy; improving pharmacists knowledge of therapeutic nutrition; and increased public awareness about community pharmacies capability to provide these services (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Strategy to overcome barriers in evaluating malnourished patients.

4. Discussion

The importance of nutritional guidance and therapy has been increasingly recognized in modern healthcare, leading to a higher demand for dietary supplements and the expectation that healthcare providers will possess knowledge in this field. Despite their potential role in promoting therapeutic nutrition and addressing malnutrition, CPs often limit their involvement in dispensing drugs and offering counseling. This study examined the knowledge, practices, and attitudes of CPs in Nigeria's rural and urban areas on therapeutic nutrition and malnutrition and examined their willingness to offer nutritional recommendations to their patients. Findings indicated that the participants agreed that pharmacists can play a role in providing nutritional recommendations.

CPs understanding of therapeutic nutrition appears less comprehensive than that of micro- and macronutrients. The results revealed that only 37% of pharmacists had good knowledge and 18% had fair knowledge of therapeutic nutrition. Because of their understanding of the sensitive nature of probable harm, CPs are more concerned with providing drug-related counseling to their patients, whereas nutrients are likely perceived as less harmful. This is consistent with the findings of a previous study in Egypt, in which most pharmacists rated their knowledge of therapeutic nutrition as average.7 Two studies conducted in the United States also reported that while nearly half of pharmacists considered their knowledge of dietary supplements (DS) to be somewhat adequate or average, only a small percentage were very satisfied.15,16

This study also explored the attitudes of CPs in Nigeria toward dietary supplements and their role in promoting public health. What is surprising is the extent to which the price and knowledge of dietary supplements influence their recommendations to patients. The results showed that approximately half of the pharmacists believed that dietary supplements had a positive impact on public health, and 23% considered price an important factor in recommending supplements to customers. These attitudes are similar to the findings of an Ethiopian survey conducted in 2019, which reported that 37% of CPs agreed to recommend supplements to customers and that price played an important role.8 In another survey in Ireland, pharmacist attitudes supported the implementation of recommendations from health professionals or dietitians.10 These findings are similar to ours, which estimated about 33% of pharmacists' attitudes toward providing nutritional advice based on prescriptions.17 Among the pharmacists, 28% agreed that dietary supplements should be sold under supervision. This result indicated that CPs have a role in dispensing nutritional supplements in pharmacies, even if it is significantly less than the result reported in a study done in Ethiopia (51% of pharmacists).8

According to the findings, 30% of participants reported that patients typically received a combination of dietary and medical treatments. Most healthcare professionals were aware of the benefits of using nutritional therapy alongside medication to treat patients. Although there is limited published work that directly supports these findings, some studies were related to the concept of nutritional therapy and dietary interventions. For instance, a study by Cena and Philips (2016),18 suggested that dietary interventions can have a positive impact on health outcomes. However, these studies do not specifically address the combination of dietary and medical treatments mentioned in the survey, which may be an important area for future research. Another study conducted in Jordan indicated that CPs were willing to offer nutritional advice as a part of their overall care plan and understood the importance of taking dietary supplements into account while treating patients with certain disorders, such as diabetes.19 An article published in British Medical Journal (2022) states that nutrition was poorly integrated into medical education, implying that more education and training in this area may be required.20

It is solely the role of a physician or nutritionist to give nutritional advice, according to about 15% of the respondents. These data raise the possibility that some CPs may feel ill-equipped to counsel patients about diet because they lack the appropriate training. It is nevertheless, concerning that some pharmacists believe they lack the knowledge required to counsel patients on nutrition. This is consistent with the findings of Kelly and colleagues (2022),15 who discovered that many pharmacists thought their nutrition knowledge was inadequate and that they lacked confidence in making dietary recommendations to patients. According to some studies, pharmacists offer nutritional guidance less frequently. For example, a Saudi Arabian study21 discovered that only 18% of pharmacists reported offering nutritional counseling to patients. Similar findings were found in the United States (US), where only 26% of pharmacists reported offering their patients nutrition-related services such as education and counseling.22 These contradictory findings show that there may be geographical disparities in pharmacy practices and attitudes toward nutritional therapy. However, the majority of research supports the idea that pharmacists are ready to provide nutritional counseling to patients based on particular observations and prescriptions and are conscious of the importance of incorporating nutritional treatment into patient care. It will take more research to corroborate this conclusion.

It is obviously helpful that pharmacists provide nutritional advice based on observations such as malnutrition and obesity. This implies that pharmacists should understand the need to assess patients' nutritional status and provide appropriate advice. This is congruent with the findings of Kelly and colleagues (2013),23 who discovered that pharmacists' engagement in recognizing and treating malnutrition in hospitalized patients improved patient outcomes. Similarly, CPs who provide nutritional advice based on prescriptions for patients with diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, and gout play an important role in helping patients manage their conditions and improve their overall health. This shows that CPs are prepared to offer dietary recommendations as part of a patient's overall care plan and are conscious of the significance of taking dietary aspects into account when treating patients with specific diseases. This is in line with research by Ballister and colleagues (2020),24 which demonstrated that CP's engagement in the care of diabetic patients led to improved patient outcomes. Overall, the attitudes of CPs toward therapeutic nutrition point to the fact that many pharmacists value nutritional therapy in patient care and are prepared to give recommendations based on specific observations and prescriptions.

Another interesting result showed that just over half of the pharmacists (55%) screened patients for malnutrition, whereas 45% did not. Of the malnutrition screenings, only 21% used body weight and body mass index, and only 11% used laboratory values, such as PCV, FBC, and Hb. A review of studies on the role of pharmacists in nutrition care found that, while pharmacists have knowledge and interest in nutrition care, there is a lack of systematic screening for malnutrition and underutilization of nutrition interventions in community pharmacies.23,25 The low use of laboratory values for the detection of malnutrition identified in our research is also consistent with previous findings. A study conducted in India found that pharmacists do not routinely use laboratory values to detect malnutrition.26 Another study discusses the unexplored path of the role of pharmacists in nutrition management and suggests that pharmacists can engage in research and analysis to provide valuable evidence-based, cost-effective dietary recommendations to communities, which can help mitigate malnutrition.14,26 Another article further suggests that pharmacists can specialize in nutrition and obtain certification to counsel patients about diet and nutrition.27 This highlights the need for education and training programs for pharmacists to enhance their role in nutritional care.

Perhaps the most interesting finding is, pharmacists identified patients with severe dehydration, infants and children with growth impairment, and newborns with low birth weight as being at high risk of malnutrition. Our findings also demonstrated that common nutritional cases seen in community pharmacies were related to diet (17%), and the service provided most frequently was weight management for obese patients (21%). Highlights of the current findings include the identification of patients at risk of severe dehydration, growth impairment, and low birth weight as indicators of malnutrition risk. To prevent severe or chronic malnutrition, a study by Chermesh and colleagues (2011) emphasized the importance of identifying individuals at risk.28 Another study by Chiba and colleagues, (2021) highlights the importance of health support pharmacies (HSPs) in providing nutritional health promotion and education, emphasizing the need for pharmacists to receive training in these areas to improve patient outcomes.29

Less than half of the pharmacists (11%) provided services related to micronutrient supplements. One study in Northern Ireland found a lack of nutrition education among community pharmacists, indicating a need for improved training.10 Post-training, improvements in nutritional knowledge and self-efficacy were observed. The study suggests advancing nutrition education in pharmacy training and developing coordination structures for micronutrient deficiency control programs in Nigeria.30

In addition, earlier studies have shown that challenges, such as patient disinterest and a lack of awareness, are frequently encountered when providing nutritional services in community pharmacies. According to a study done in Malaysia, pharmacists assessed the biggest hurdles to providing nutrition-related services to be a lack of patient demand, a lack of time, and inadequate compensation.31 Another study conducted in the United Kingdom reported that CPs identified a lack of training time and financial incentives as obstacles to providing dietary advice to patients.32

The solutions outlined by pharmacists in this survey—enhancing knowledge about therapeutic nutrition and developing private counseling spaces in pharmacies—are in line with earlier research. According to a systematic review of research on the benefits of pharmacy-based interventions on patient nutrition-related outcomes,32,33 pharmacist-led interventions such as nutrition education and counseling can dramatically enhance patient nutrition habits.

Finally, the findings revealed that more than 50% of pharmacists thought that the biggest obstacles to offering nutritional services were a lack of motivation, a shortage of nutrition experts, and patients' ignorance about pharmacist nutrition competence. The results of this research are consistent with this.33

4.1. Strengths and limitations of the study

We believe that this is the first study to specifically examine CPs' knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors about therapeutic nutrition and malnutrition in Nigeria. The study's greatest strength is the intradisciplinary cohort that was used, which allowed for the investigation of CPs with years of experience. Additionally, the research was conducted in both urban and rural areas, demonstrating the diversity of experience.

Limitations to this study: Data collection may be skewed due to self-reported responses. The sample size was small (80 participants); therefore, the results cannot be generalized to all Nigerian CPs. A comprehensive study is needed to understand the demographics and other factors that affect CPs' knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding therapeutic nutrition and malnutrition. Another potential limitation of online surveys is that individuals must have internet access and be willing to participate. This may exclude individuals who do not have reliable internet connectivity or those who are less comfortable with technology.

5. Conclusion

These findings underline the need to enhance CPs awareness in order to improve their knowledge and practices in the management of malnutrition. While some CPs were involved in malnutrition screening and nutrition-related services, there is a need for greater assistance and resources to increase their ability to deliver nutritional services and raise patient awareness of these services. Furthermore, pharmacists should understand the significance of monitoring patients' nutritional condition and providing relevant guidance. In order to provide the best care for malnourished patients, policies fostering collaboration among pharmacists, physicians, and dieticians should be implemented.

Funding

No financial assistance was received for this study. However, the authors would like to acknowledge the valuable contributions of their colleagues, who provided feedback and suggestions during the proofreading process.

Use AI tools

The manuscript was proofread using the following AI tools to improve the language clarity and comprehension:

1. CHATGPT and

2. Quilbot

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Fact Sheets - Malnutrition World Health Organization (WHO). June 9, 2021. 2021. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malnutrition Accessed September 24, 2023.

- 2.World Health Organization, WHO Report of the Technical Consultation on Measuring Healthy Diets: Concepts, Methods and Metrics: Virtual Meeting, 18–20 May 2021. 2021. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/351048/9789240040274-eng.pdf?sequence=1 Accessed September 24, 2023.

- 3.Malnutrition in the Elderly | Resource Center | Aegis Living Aegis Living - Senior Assisted Living and Memory Care. 2019. https://www.aegisliving.com/resource-center/malnutrition-among-the-elderly/ Accessed September 13, 2023.

- 4.UNICEF . UNICEF; 2023. Nearly one million children under 5 in the central Sahel facing severe wasting in 2023.https://www.unicef.org/wca/press-releases/nearly-one-million-children-under-5-central-sahel-facing-severe-wasting-2023-unicef Retrieved May 2, 2023. Accessed September 24, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joint FIP/WHO guidelines on good pharmacy practice: standards for quality of pharmacy services WHO Technical Report Series, Geneva, No. 961. 2011. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/330978/DI311-15-26-eng.pdf Annux 8. Accessed September 24, 2023.

- 6.Agomo Chijioke O. The role of community pharmacists in public health: a scoping review of the literature. J Pharm Health Serv Res. 2012;3(1):25–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1759-8893.2011.00074.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Medhat M., Sabry N., Ashoush N. Knowledge, attitude and practice of community pharmacists towards nutrition counseling. Int J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;42:1456–1468. doi: 10.1007/s11096-020-01106-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Emiru Yohannes Kelifa, et al. Nutrition and Dietary Supplements; 2019. Community pharmacists’ knowledge, attitude, and professional practice behaviors towards dietary supplements: results from multi-center survey in Ethiopia; pp. 59–68. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Browne Sarah, Kelly Lucy, Geraghty Aisling A., et al. Healthcare professionals’ perceptions of malnutrition management and oral nutritional supplement prescribing in the community: a qualitative study. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2021;44:415–423. doi: 10.1016/j.clnesp.2021.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Douglas Pauline L., McCarthy Helen, McCotter Lynn E., et al. Nutrition education and community pharmacy: a first exploration of current attitudes and practices in Northern Ireland. Pharmacy. 2019;7(1):27. doi: 10.3390/pharmacy7010027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lamb Christopher A., Parr John, Lamb Elizabeth I.M., Warren Matthew D. Adult malnutrition screening, prevalence and management in a United Kingdom hospital: cross-sectional study. Br J Nutr. 2009;102(4):571–575. doi: 10.1017/S0007114509236038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aburrow A.J., Micklam J., Bowhill J., Wallis K., Parsons E.L. Role of community pharmacies in raising awareness of malnutrition in older people. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2017;22:134. https://wessexahsn.org.uk/img/projects/Community%20Pharmacy%20Poster%20AA%20PDF-1480456210.pdf Accessed September 24, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oseni Yejide Olukemi, Oseni Yejide Olukemi. Pharmacists’ distribution in Nigeria; implication in the provision of safe medicines and pharmaceutical care. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2017;9(10):49–54. doi: 10.22159/ijpps.2017v9i10.20454. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.SurveyMonkey 2023. https://www.surveymonkey.com/ SurveyMonkey Inc.

- 15.Kelly Dervla, Chawke Jacqueline, Keane Megan, Conway Helen, Douglas Pauline, Griffin Anne. An exploration of the self-perceived nutrition competencies of pharmacists. Explor Res Clin Soc Pharm. 2022;8:100203. doi: 10.1016/j.rcsop.2022.100203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clauson Kevin A., McQueen Cydney E., Shields Kelly M., Bryant Patrick J. Knowledge and attitudes of pharmacists in Missouri regarding natural products. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67(1/4):301. https://www.proquest.com/openview/8b5801d6da75ead16a6970abfa2ee5cd/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=41120 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunn Jeffery D., Cannon H. Eric, Lewis Tamara, Shane-McWhorter Laura. Development of a Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) Pharmacy and Therapeutics (PandT) Subcommittee and CAM Guide for Providers. J Manag Care Pharm. 2005;11(3):252–258. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2005.11.3.252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cena Hellas, Calder Philip C. Defining a healthy diet: evidence for the role of contemporary dietary patterns in health and disease. Nutrients. 2020;12(2):334. doi: 10.3390/nu12020334. PMID: 32012681; PMCID: PMC7071223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Taani Ghaith M., Ayoub Nehad M. A baseline survey of community pharmacies’ workforce, premises, services and satisfaction with medical practitioners in Jordan. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75(9) doi: 10.1111/ijcp.14487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Downer Sarah, Berkowitz Seth A., Harlan Timothy S., Olstad Dana Lee, Mozaffarian Dariush. Food is medicine: actions to integrate food and nutrition into healthcare. BMJ. 2020;369 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2482. PMID: 32601089; PMCID: PMC7322667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alshahrani Ali. Knowledge, attitudes, and practice of community pharmacists towards providing counseling on vitamins, and nutritional supplements in Saudi Arabia. AIMS Public Health. 2020;7(3):697. doi: 10.3934/publichealth.2020054. PMID: 32968687; PMCID: PMC7505785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meier Megan, Singh Reshmi L., Thyagarajan Baskaran. Consumer’s opinion on a pharmacist’s role in nutritional counseling. Innov Pharm. 2021;12(2) doi: 10.24926/iip.v12i2.3634. PMID: 34345515; PMCID: PMC8326700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tappenden Kelly A., Quatrara Beth, Parkhurst Melissa L., Malone Ainsley M., Fanjiang Gary, Ziegler Thomas R. Critical role of nutrition in improving quality of care: an interdisciplinary call to action to address adult hospital malnutrition. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113(9):1219–1237. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2013.05.015. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2212267213006412 ISSN 2212-2672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ballister Briana, Hernandez Rebecca L., Quffa Lieth H., Franck Andrew J. Clinical pharmacy specialist collaborative management and prescription of diabetes medications with cardiovascular benefit. J Pharm Pract. 2022;08971900221144399 doi: 10.1177/08971900221144399. 36469659 Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.International Pharmaceutical Federation Nutrition and weight management services: A toolkit for pharmacists. 2021. https://www.fip.org/file/4986 Retrieved from.

- 26.Singla Neelam, Jindal Avani, Mahapatra Debarshi Kar. Role of pharmacist in nutrition management-the unexplored path. Ind J Pharm Pract. 2023;16(2) https://ijopp.org/sites/default/files/InJPharPract-16-2-83.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pharm D., Leheny Shelby. Counsel patients about diet and nutrition. Pharmacy Times Pharmacy Times October. 2019;17:2019. https://www.pharmacytimes.com/view/counsel-patients-about-diet-and-nutrition [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chermesh Irit, Papier Irena, Karban Amir, Kluger Yoram, Eliakim Rami. Identifying patients at risk for malnutrition is a MUST: A multidisciplinary approach. e-SPEN, Eur e-J Clin Nutr Metabo. 2011;6(1) doi: 10.1016/j.eclnm.2010.09.002. e41-e44. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chiba Tsuyoshi, Tanemura Nanae, Nishijima Chiharu. Determination of the awareness about and need for health support pharmacies as the provider of consultation service about nutrition education and diet-related health promotion by health professionals in Japan. Nutrients. 2021;14(1):165. doi: 10.3390/nu14010165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anjorin Olufolakemi, Okpala Oluchi, Adeyemi Olutayo. Coordinating Nigeria’s micronutrient deficiency control programs is necessary to prevent deficiencies and toxicity risks. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2019;1446(1):153–169. doi: 10.1111/nyas.14055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beshir Semira A., Hamzah Nur Hamimi Bt. Health promotion and health education: perception, barriers and standard of practices of community pharmacists. Int J Health Promot Educ. 2014;52(4):174–180. doi: 10.1080/14635240.2014.888809. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cork T., Guard H., Jones C., Allinson M., White S. Community pharmacists’ perspectives on malnutrition screening and support: a qualitative study. Int J Pharm Pract. 2016;24(3):3–7. https://eprints.keele.ac.uk/id/eprint/2766/1/Cork,%20Guard,%20Jones,%20Allinson%20&%20White%20-%20RPS%20abstract%202016.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coutureau C., Slimano F., Mongaret C., Kanagaratnam L. Impact of pharmacists-led interventions in primary care for adults with type 2 diabetes on HbA1c levels: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(6):3156. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19063156. 8. PMID: 35328842; PMCID: PMC8949021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]