Abstract

Rapid, quantitative, and objective determination of the susceptibilities of human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) clinical isolates to ganciclovir has been assessed by an assay that uses a fluorochrome-labeled monoclonal antibody to an HCMV immediate-early antigen and flow cytometry. Analysis of the ganciclovir susceptibilities of 25 phenotypically characterized clinical isolates by flow cytometry demonstrated that the 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50s) of ganciclovir for 19 of the isolates were between 1.14 and 6.66 μM, with a mean of 4.32 μM (±1.93) (sensitive; IC50 less than 7 μM), the IC50s for 2 isolates were 8.48 and 9.79 μM (partially resistant), and the IC50s for 4 isolates were greater than 96 μM (resistant). Comparative analysis of the drug susceptibilities of these clinical isolates by the plaque reduction assay gave IC50s of less than 6 μM, with a mean of 2.88 μM (±1.40) for the 19 drug-sensitive isolates, IC50s of 6 to 8 μM for the partially resistant isolates, and IC50s of greater than 12 μM for the four resistant clinical isolates. Comparison of the IC50s for the drug-susceptible and partially resistant clinical isolates obtained by the flow cytometry assay with the IC50s obtained by the plaque reduction assay showed an acceptable correlation (r2 = 0.473; P = 0.001), suggesting that the flow cytometry assay could substitute for the more labor-intensive, subjective, and time-consuming plaque reduction assay.

We have entered an era of effective therapy for many viral diseases (7, 8, 12, 18). However, with the advent of long-term therapy for the treatment of acute viral infections and prophylaxis of recurrent viral infections, the emergence of drug-resistant clinical isolates has become a common problem (2, 3, 9, 10, 13, 15, 16, 20). Both genotypic and phenotypic assays have been used to determine resistance. Current genotypic methods for determining antiviral susceptibility depend on knowledge of the specific mutations that lead to resistance (4–6, 23, 24, 33). However, since each of the antiviral targets has a three-dimensional structure, mutations distant from the known mutations or the active site may lead to drug resistance. Furthermore, in many cases, multiple mutations, each of which is insufficient to mediate resistance, may be required to generate resistant virus. Hence, genetic analysis with primers directed against known mutations may not detect all possible expressions of resistance. A phenotypic measure of drug resistance may be a more reliable indicator for determining the susceptibilities of virus isolates to antiviral compounds. Currently used phenotypic assays include plaque reduction assays for herpes simplex viruses (16) and human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) (1, 21, 33, 34) and a variety of tissue culture assays that measure inhibition of virus replication or antigen expression for HCMV (17, 30) and human immunodeficiency virus (19). These phenotypic assays are time-consuming, labor-intensive, and often very subjective.

Fluorescent dyes that bind to nucleic acids and fluorochrome-labeled monoclonal antibodies directed against viral antigens have been used in conjunction with flow cytometry to quantitate the number of virus-infected cells, as well as viral antigen expression and DNA synthesis within those cells (14, 25, 26, 29, 31, 32). Flow cytometric analysis of the synthesis of immediate-early or late antigens in cells infected with HCMV laboratory strains and clinical isolates after 144 or 168 h of incubation in the presence of various concentrations of ganciclovir has been used to determine ganciclovir susceptibility (22, 27). These phenotypic drug susceptibility assays that count the number of antigen-positive cells in the absence and presence of antiviral compounds have several advantages over the plaque reduction assay. These include automation, speed, ease of analysis, objectivity, and the ability to analyze a larger portion of the sample to be tested, yielding a more accurate assessment of drug susceptibility. However, they are not more rapid than the plaque reduction assay.

The HCMV immediate-early antigen is synthesized a few hours after infection of fibroblasts (28). Detection of immediate-early antigen synthesis would reflect virus replication at an earlier time postinoculation than detection of late-antigen synthesis. Since ganciclovir blocks HCMV DNA replication, it will have no effect on the synthesis of the immediate-early antigen during the first round of virus replication (18, 27). However, in the presence of inhibitory concentrations of ganciclovir, subsequent rounds of HCMV replication would be blocked, decreasing the percentage of cells synthesizing the immediate-early antigen. This reasoning was used to develop a more rapid procedure for determining the ganciclovir susceptibilities of HCMV clinical isolates. Here we report on the use of this more rapid method (96 versus 168 h) for determining the ganciclovir susceptibilities of HCMV clinical isolates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell cultures and virus-infected cells.

Human embryonic lung fibroblasts (MRC-5) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (CCL 171), and human foreskin fibroblasts were obtained from Viromed (Minneapolis, Minn.). The cells were cultured as described previously (27). Well-characterized, paired ganciclovir-sensitive (isolate V379354) and ganciclovir-resistant (isolate V917401) HCMV clinical isolates were obtained from A. Erice (15), and partially resistant (isolate K8313) and resistant (isolate MR11979) (6) clinical isolates were obtained from W. L. Drew and were provided to us by the Division of AIDS-sponsored Virology Quality Assurance Program. Ganciclovir-sensitive (isolate MG) and ganciclovir-resistant (isolate OBR) clinical isolates were obtained from N. Lurain (23). Additional clinical isolates were obtained from the Clinical Microbiology Laboratories at the Albany Medical Center Hospital, Albany, N.Y., and Rush Presbyterian St. Luke’s Medical Center, Chicago, Ill. All clinical isolates were propagated as described previously (27). The susceptibility of each of these clinical isolates to ganciclovir was determined by the plaque reduction assay (1) with the following results: GU was ganciclovir resistant, MAL was partially ganciclovir resistant, and the other isolates were ganciclovir sensitive. Known genotypic and phenotypic characteristics of some of these clinical isolates are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Previously characterized HCMV clinical isolates

| Isolate | Genotypea | Phenotypeb,c | IC50 (μM)b | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MR11979 | POL C412 POL M802 UL97 W603 | GCV, FOS, and HPMPC resistant | GCV, >50; FOS, 870; HPMPC, 24 | 6 |

| V379354 (C9208)e | WTd | GCV, FOS, and HPMPC sensitive | GCV, 3.42; FOS, 96.54; HPMPC, 0.30 | 15 |

| V917401 (C9209)e | POL A552 POL A841 UL97 V460 | GCV resistant; FOS and HPMPC sensitive | GCV, 43.06; FOS, 179.91; HPMPC, 0.6 | 15 |

| K8313 | NDf | Partially GCV resistant | GCV, 12 | 27 |

| MAL | ND | Partially GCV resistant | GCV, 7.93 | Table 3 |

| OBR | UL97 S595 | GCV resistant, FOS and HPMPC sensitive | GCV, 20; FOS, 150; HPMPC, 0.5 | 23 |

| MG | WT | GCV, FOS, and HPMPC sensitive | GCV, 5; FOS, 100; HPMPC, 0.5 | 23 |

| GU | ND | GCV resistant, FOS sensitive | GCV, 13.2; FOS, 198.4g | Table 3 |

| JD | WT | GCV sensitive, FOS sensitive | GCV, 3.0; FOS, 149.9g | Table 3 |

Genotypes were determined by sequencing the UL97 and POL regions of the viral isolates.

Phenotypes and IC50s were determined by plaque reduction assays.

GCV, ganciclovir; FOS, foscarnet; HPMPC, cidofovir.

WT, wild type.

C9208 and C9209 are plaque-purified derivatives of V379354 and V917401, respectively.

ND, not determined.

Unpublished foscarnet plaque reduction assay data.

Ganciclovir.

A 5 mM stock of ganciclovir in sterile water was provided to participating laboratories by the Virology Quality Assurance Program and was used in these experiments as described previously (27).

Plaque reduction assays.

A modification of the standard plaque reduction assay was used (1). Approximately 100 HCMV-infected cells were added to MRC-5 cell monolayers overlaid with medium containing six twofold dilutions of ganciclovir (0 to 96 μM) in 24-well plates. Since clinical isolates remain cell associated and cause infection by cell-to-cell spread, no agarose overlay was required. The effect of ganciclovir on the plaque formation of each clinical isolate was analyzed in quadruplicate. After 7 days of incubation, the monolayers were fixed with formaldehyde and stained with crystal violet, and the number of foci was counted with a light microscope. The number of foci at each ganciclovir concentration was averaged, and the percent reduction in the number of foci at each drug concentration was calculated.

Ganciclovir susceptibility assay by flow cytometry.

A modification of a previously described flow cytometry procedure was used (27). Cell monolayers were infected at a low multiplicity of infection (MOI), and the effect of ganciclovir on the percentage of cells synthesizing the immediate-early antigen was determined at 96 h postinfection. In brief, 105 virus-infected cells were added directly to medium containing concentrations of ganciclovir ranging from 0 to 96 μM, overlaying cell monolayers in 25-cm2 flasks. After incubation at 37°C for 96 h, the cells were harvested, permeabilized with methanol, and treated with a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled monoclonal antibody (MAB810; Chemicon International, Inc., Temecula, Calif.) to an HCMV immediate-early antigen. After incubation at 37°C for 1 h and washing, 7-amino-actinomycin D (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.), which stains the cell-associated DNA used to identify intact cells, was added, and the cells were analyzed for the percentage of HCMV-antigen positive cells by flow cytometry. For each experiment, one 25-cm2 flask containing a monolayer of cells was used for each drug concentration.

For the time course study, HCMV-infected cells were incubated at 37°C for the stated times, harvested, permeabilized, and treated with either the FITC-labeled monoclonal antibody to the immediate-early antigen (MAB810; Chemicon International, Inc.) or the FITC-labeled monoclonal antibody to an HCMV late antigen (MAB8127; Chemicon International, Inc.). Further treatment and analysis were as described above for the cells treated with the immediate-early antigen.

Data analysis.

The ImmunoCount II program of the Ortho Diagnostic Systems, Inc., CytoronAbsolute (Ortho Diagnostic Systems, Inc., Raritan, N.J.), the Lysis II software with the FACScan, and the Cell Quest software with the FACSCalibur flow cytometers (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, Inc., San Jose, Calif.) were used to analyze and plot the flow cytometry data. Because the virus-infected cells in the inoculum remain throughout the experiment, the percentage of HCMV-infected cells that react with fluorochrome-labeled monoclonal antibodies in the flow cytometry assay does not go to zero even in the presence of inhibitory concentrations of ganciclovir. Therefore, an inhibitory sigmoid Emax model was used to estimate the 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50s) for flow cytometry assay data. For consistency, it was also used to calculate IC50s for the plaque reduction assay data. The model was implemented in the ADAPT II program of D’Argenio and Schumitzky (11). The two assays were compared by determination of the bias and precision of the flow cytometry assay relative to those of the plaque reduction assay. The bias of each sample was calculated as the mean percent error, as follows: [(flow cytometry assay IC50 − plaque reduction assay IC50) × 100]/plaque reduction assay IC50. The precision of each sample was calculated as mean absolute percent error, as follows: [|flow cytometry assay IC50 − plaque reduction assay IC50| × 100]/plaque reduction assay IC50.

RESULTS

Time course for the synthesis of the HCMV antigens.

The time after infection when immediate-early and late antigens could be detected in cells infected with a ganciclovir-sensitive HCMV clinical isolate (isolate V379354) and the effect of ganciclovir on the percentage of cells synthesizing each of these antigens at various times postinfection were determined. The data are presented in Table 2. At 24 h postinfection, 16.9% of the cells were HCMV immediate-early antigen positive and 2.0% of the cells were HCMV late-antigen positive. Increasing concentrations of ganciclovir did not significantly affect the percentage of immediate-early- or late-antigen-positive cells, suggesting that antigen expression at 24 h postinfection resulted from the virus-infected cells in the inoculum and represents the background associated with this experimental procedure. At 48 h postinfection, the proportion of HCMV immediate-early-antigen-positive cells was 34.1% in the absence of ganciclovir, whereas in the presence of 6 and 12 μM ganciclovir, the proportions of HCMV immediate-early-antigen-positive cells were 23.2 and 20.2%, respectively. At 48 h postinfection, the percentage of cells expressing the late antigen did not increase. By 72 h postinfection, 64.1% of the cells were HCMV immediate-early antigen positive, whereas in the presence of 6 or 12 μM ganciclovir, only 34.5 and 26.5% of the cells were HCMV immediate-early antigen positive, respectively. Late-antigen synthesis was still minimal at 72 h postinfection. By 96 h postinfection, the percentage of HCMV immediate-early-antigen-positive cells approached a maximum (78.3%) in the absence of drug, while 27.8 and 23.4% of the cells expressed the immediate-early antigen in the presence of 6 and 12 μM ganciclovir, respectively. At this time, the percentage of late-antigen-positive cells was still minimal, but late-antigen synthesis was apparent at 120 and 144 h postinfection. The flow cytometry-based ganciclovir IC50 for this clinical isolate was 4.21 μM by using either the immediate-early-antigen-positive cells at 96 h postinfection or the late-antigen-positive cells at 144 h postinfection. The ganciclovir IC50 for this clinical isolate measured by flow cytometry was similar to the IC50 (3.42 μM) obtained by the plaque reduction assay by others (15) (Table 1) and in this investigation (5.52 μM ganciclovir; Table 3). Analysis of the time course of immediate-early and late-antigen synthesis and the effect of ganciclovir on the percentage of cells synthesizing these antigens were similar for several other ganciclovir-sensitive HCMV clinical isolates (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Time course of effect of ganciclovir on the percentage of antigen-positive V379354-infected cells

| Time (h) postin- fection | Ganciclovir concn (μM) | % IE Ag + cellsa | IC50 (μM) for IE Ag + cellsb | % Late Ag + cellsc | IC50 (μM) for late Ag + cells |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 | 0 | 16.9 | 2.0 | ||

| 6 | 14.3 | 1.9 | |||

| 12 | 15.7 | 1.8 | |||

| 48 | 0 | 34.1 | 2.1 | ||

| 6 | 23.2 | 1.4 | |||

| 12 | 20.2 | 1.4 | |||

| 72 | 0 | 64.1 | 3.3 | ||

| 6 | 34.5 | 6.61 | 1.8 | 7.84 | |

| 12 | 26.5 | 1.6 | |||

| 96 | 0 | 78.3 | 4.3 | ||

| 6 | 27.8 | 4.21 | 1.7 | 4.64 | |

| 12 | 23.4 | 1.4 | |||

| 120 | 0 | 83.1 | 19.4 | ||

| 6 | 39.1 | 5.55 | 4.0 | 3.31 | |

| 12 | 31.8 | 3.2 | |||

| 144 | 0 | 77.2 | 26.2 | ||

| 6 | 39.2 | 6.12 | 6.9 | 4.21 | |

| 12 | 27.8 | 3.2 |

IE Ag + cells, immediate-early-antigen-positive cells. The percentage of antigen-positive cells was derived from one flow cytometric analysis.

IE Ag, immediate-early antigen.

Late Ag + cells, late-antigen-positive cells. The percentage of antigen-positive cells was derived from one flow cytometric analysis.

TABLE 3.

Comparison of results of flow cytometry and plaque reduction assays

| Clinical isolate | IC50 (μM)

|

Ganciclovir phenotypea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flow cytometry assayb | Plaque reduction assayc | ||

| V917401 | >96 | >96 | R |

| MR11979 | >96 | >96 | R |

| OBR | >96 | 20 | R |

| GU | >96 | 13.2 | R |

| MAL | 8.48 | 7.93 | PR |

| K8313 | 9.79 | 9.21 | PR |

| V379354 | 3.27 | 5.52 | S |

| SAG | 6.66 | 5.65 | S |

| MG | 4.51 | 5.00 | S |

| VIL | 1.14 | 1.62 | S |

| TUC | 1.28 | 1.86 | S |

| GRO | 5.72 | 3.05 | S |

| LAN | 4.20 | 2.26 | S |

| COP | 6.65 | 3.62 | S |

| MAC | 6.30 | 4.02 | S |

| BRO | 6.53 | 4.20 | S |

| PHI | 3.91 | 1.32 | S |

| LAP | 4.82 | 2.33 | S |

| HOW | 1.39 | 2.18 | S |

| PER | 1.75 | 2.27 | S |

| MCI | 4.54 | 2.30 | S |

| LA | 2.48 | 1.17 | S |

| JD | 5.50 | 3.00 | S |

| FK-1 | 6.28 | 1.75 | S |

| FK-3 | 5.13 | 1.78 | S |

The phenotype was based on the results of the plaque reduction assay. R, resistant; PR, partially resistant; S, sensitive.

Data are from a single analysis.

Data are from a single plaque reduction assay performed in quadruplicate. The well-to-well variation in the numbers of PFU at the same drug concentration was less than 10%.

Flow cytometric analysis of the effect of ganciclovir on immediate-early antigen synthesis.

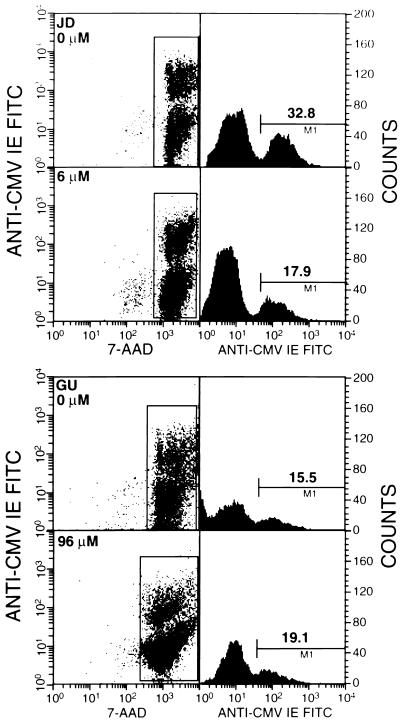

Since the percentage of immediate-early-antigen-positive cells approached a maximum at 96 h postinfection (Table 2), the percentage HCMV immediate-early-antigen-positive cells at 96 h postinfection was selected as the flow cytometry parameter used to determine the susceptibilities of the HCMV clinical isolates to ganciclovir. Figure 1 illustrates the use of flow cytometry to determine the effect of ganciclovir on the synthesis of the immediate-early antigen at 96 h postinfection in cells infected with a ganciclovir-sensitive clinical isolate (isolate JD; ganciclovir IC50, 3.0 μM; Table 1) or a ganciclovir-resistant clinical isolate (isolate GU; ganciclovir IC50, 13.2 μM; Table 1). In the absence of ganciclovir, 32.8% of the cells infected with the JD isolate and 15.5% of the cells infected with the GU isolate expressed the immediate-early antigen. In the presence of 6 μM ganciclovir, the percentage of immediate-early-antigen-positive cells in the JD-infected culture was reduced to 17.9%, whereas the percentage of antigen-positive cells in the GU-infected culture was not reduced even in the presence of 96 μM ganciclovir. These results demonstrate the feasibility of using fluorochrome-labeled monoclonal antibody to an HCMV immediate-early antigen and flow cytometry to distinguish between ganciclovir-susceptible and ganciclovir-resistant HCMV clinical isolates.

FIG. 1.

Effect of ganciclovir on immediate-early (IE) antigen synthesis. Human foreskin fibroblast cells were infected with a ganciclovir-sensitive clinical isolate (isolate JD) or a ganciclovir-resistant clinical isolate (isolate GU) in the absence or presence of ganciclovir, and the percentage of antigen-positive cells was determined at 96 h postinfection by flow cytometry. For cells infected with isolate JD, the proportion of antigen-positive cells was reduced from 32.8% in the absence of drug to 17.9% in the presence of 6 μM drug. For cells infected with isolate GU, there was no reduction in the percentage of antigen-positive cells even in the presence of 96 μM ganciclovir. 7-AAD, 7-amino-actinomycin D.

Determination of ganciclovir susceptibility of clinical isolates by flow cytometric analysis of immediate-early antigen expression.

The ganciclovir susceptibilities of 25 HCMV clinical isolates were determined by both the flow cytometry assay at 96 h postinfection and the plaque reduction assay at 7 days postinfection. The data are presented in Table 3. Flow cytometric analysis of the 25 clinical isolates showed that 19 were ganciclovir sensitive (ganciclovir IC50s, less than 7 μM), 2 were partially resistant (IC50s, between 8 and 10 μM), and 4 were resistant (IC50s, greater than 96 μM). The plaque reduction assay of the same 25 clinical isolates showed that 19 were sensitive (ganciclovir IC50s, less than 6 μM), 2 were partially resistant (IC50s, between 7 and 10 μM), and 4 were resistant (IC50s, greater than 12 μM). The IC50s determined from flow cytometric analysis of immediate-early antigen synthesis compared favorably to the IC50s obtained for these clinical isolates by the plaque reduction assay (Table 3) and with previously published results (Table 1). For example, the IC50s for the ganciclovir-resistant clinical isolates with mutations in both the UL97 and POL genes, V917401 and MR11979, are similar by the flow cytometry assay and the plaque reduction assay (Table 3), and the IC50s for both isolates agree with the published data for these clinical isolates (Table 1). The ganciclovir IC50s for ganciclovir-sensitive isolate V379354 were 3.27 μM by the flow cytometry assay, 5.52 μM by the plaque reduction assay (Table 3), and 3.42 μM by the published plaque reduction assay (Table 1). Therefore, there is good agreement between the flow cytometry assay data, the plaque reduction assay data, and the previously published plaque reduction assay data.

Comparison of flow cytometry assay data with plaque reduction assay data.

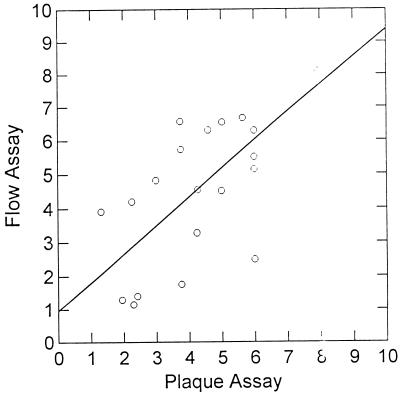

When all of the flow cytometry assay results (dependent variable) were compared with the plaque reduction assay results (independent variable), there was an excellent correlation between assays (flow cytometry assay IC50 = 1.03 × plaque reduction assay IC50 + 7.12; r2 = 0.579; P = 0.001). Data for two isolates were observed to be outliers. The IC50s were 13.2 and 20 μM, respectively, by the plaque reduction assay, and the IC50s were greater than 96 μM by the flow cytometry assay. It should be noted, however, that both assays classified these isolates as being in the resistant range. When only sensitive and partially resistant isolates are examined, it is clear that the results of the flow cytometry assay show good agreement with the results of the plaque reduction assay (Fig. 2; flow cytometry assay IC50 = 0.753 × plaque reduction assay IC50 + 2.17; r2 = 0.473; P = 0.001). When examining all of the data, the flow cytometry assay data always typed the clinical isolates in the same category (sensitive, partially resistant, or resistant) as the plaque reduction assay did. Consequently, there were no misclassification errors engendered by the use of the flow cytometry assay. The mean bias of the flow cytometry assay relative to that of the plaque reduction assay for all 25 isolates (Table 3) was 91.0%, and the mean precision was 104.6%. For the partially resistant and sensitive isolates only (n = 21), these values were 60.4 and 76.6%, respectively. For sensitive isolates (n = 19), they were 66.3 and 84.2%, respectively.

FIG. 2.

Regression line for IC50s determined by plaque reduction assay and flow cytometry assay of fully sensitive and partially sensitive clinical isolates tested. Each point is the result of a single determination. The equation of the line was y = 0.0753 × x + 0.217 (r2 = 0.473; P = 0.001).

Reproducibility of the flow cytometry susceptibility assay.

To determine the reproducibility of the assay, the ranges and standard deviations of the IC50s for a number of drug-resistant and drug-sensitive clinical isolates were determined by multiple independent analyses by the flow cytometry assay. The results are presented in Table 4. Ganciclovir IC50s of greater than 96 μM were obtained for the two drug-resistant clinical isolates each time that they were analyzed. The IC50s for the ganciclovir-sensitive clinical isolates were in the sensitive range, with acceptable standard deviations. For clinical isolate K8313, the mean IC50 was 9.01 μM, confirming that it is partially resistant. However, a range of IC50s with a large standard deviation was reported for the isolate, suggesting the difficulty of determining drug susceptibilities of partially resistant clinical isolates by this method. The plaque reduction assay also yields a broad range of IC50s for this clinical isolate (data not shown). Thus, for sensitive and resistant clinical isolates, the flow cytometry drug susceptibility assay is reproducible.

TABLE 4.

Reproducibility of IC50 determinations

| Clinical isolate | Na | Mean of IC50 (μM of ganciclovir) | Range of IC50s (μM of ganciclovir) | SD (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MR11979 | 10 | >96 | >96 | |

| V917401 | 10 | >96 | >96 | |

| V379354 | 8 | 5.63 | 4.21–6.18 | 0.985 |

| K8313 | 8 | 9.01 | 4.31–16.16 | 4.721 |

| PER | 6 | 5.12 | 2.55–6.50 | 1.319 |

| MCI | 4 | 5.40 | 4.38–6.26 | 0.956 |

| GRO | 4 | 7.45 | 5.73–8.84 | 1.580 |

N, number of replicates.

DISCUSSION

We have developed a rapid, quantitative, and objective assay system for measuring the ganciclovir susceptibilities of HCMV clinical isolates. The assay is based on the flow cytometric analysis of the effect of ganciclovir on the percentage of HCMV-infected cells synthesizing the HCMV immediate-early antigen at 96 h postinfection. By the flow cytometry assay, ganciclovir IC50s for ganciclovir-sensitive clinical isolates was between 1.14 and 6.66 μM, with a mean of 4.32 μM and a standard deviation of ±1.92. For ganciclovir-resistant clinical isolates ganciclovir IC50s were greater than 96 μM. The IC50s measured by the flow cytometry assay did not differ significantly from the IC50s obtained by plaque reduction assays for these clinical isolates. Moreover, the effect of ganciclovir on the percentage of cells expressing the immediate-early antigen was detectable by flow cytometry at 96 h postinfection, making this a more rapid method for measuring antiviral drug susceptibility than the plaque reduction assay, which requires at least 7 days of incubation before analysis.

To accurately determine the susceptibilities of clinical isolates by this assay, a sufficient number of virus-infected cells should be added to the monolayer so that approximately 25 to 50% of the cells in the monolayer show cytopathic effects (CPEs) after 96 h of incubation in the absence of ganciclovir. Since different HCMV clinical isolates replicate with different efficiencies, the time required for the cells in the monolayer to show 25 to 50% CPE in the absence of ganciclovir will vary. In our experience, most clinical isolates will yield this amount of a CPE within 96 h postinfection in the absence of ganciclovir. Even when the monolayer shows less than a 25% CPE at 96 h postinfection in the absence of drug, a reduction in the percentage of cells expressing the immediate-early antigen in the presence of drug can be detected and an accurate IC50 can be determined. However, daily microscopic examination of infected cell monolayers will determine the optimal time for harvesting in each experiment. Increasing the MOI from 0.1 to 1.0 will not improve the assay because the increased background due to the input infected cells will mask the reduction in the number of cells expressing the immediate-early antigen in the presence of inhibitory concentrations of ganciclovir. Furthermore, at a high MOI with HCMV, ganciclovir has no effect on immediate-early antigen synthesis (27).

The performance of the flow cytometry assay was acceptable, with the IC50 determined by the flow cytometry assay correlating significantly with the values determined by the reference plaque reduction assay. It should be noted, however, that the regression analysis data for all 25 isolates may be misleading, because this relationship is driven by the two isolates for which ganciclovir IC50s were greater than 96 μM by both assays. Nonetheless, when only data for sensitive and intermediate isolates are examined (n = 21), the regression is still significant (Fig. 2). When the new assay is evaluated by calculating the bias and precision relative to those of the plaque reduction assay, it is clear that the flow cytometry assay tends to give values which are higher than those given by the plaque reduction assay. These higher values may be due to the high sensitivity of the flow cytometry assay and to the fact that the flow cytometry assay measures the effects of antiviral drugs on the synthesis of the immediate-early antigen, which does not require virus replication for its synthesis, whereas the plaque reduction assay measures the effect of antiviral drugs on virus replication. Therefore, it is possible for some virus-infected cells to express the immediate-early antigen in the absence of virus replication because viral DNA synthesis, which is blocked by ganciclovir, is not required for immediate-early antigen synthesis. The mean biases for all isolates, for the sensitive plus intermediate isolates, and for the sensitive isolates alone were 91.0, 60.4, and 66.3%, respectively. To put this in perspective, if the plaque reduction assay reported a value of 2.9 μM (the mean for the sensitive isolates), the flow cytometry assay would, on average, report values of between 4.6 and 5.5 μM. This change in the reported IC50s is likely to have little clinical significance. There were no misclassification errors on the part of the flow cytometry assay, by which resistant viruses were always typed as resistant and sensitive viruses were always typed as sensitive. The largest errors observed were conservative ones, in which IC50s for two of the resistant isolates were greater than 96 μM by flow cytometry, while the IC50s were 13.2 and 20 μM by the plaque reduction assay. On balance, the ease, speed, and objectivity of the flow cytometry assay coupled with acceptable performance make it suitable for widespread introduction into laboratories concerned with evaluation of the resistance of HCMV to antiviral agents.

One drawback to this technology as it is currently formulated is the significant background caused by the input virus-infected cells, which prevents the percentage of antigen-positive cells from reaching zero in the presence of inhibitory concentrations of ganciclovir. By using cell-free virus as the inoculum, this problem could be eliminated from the assay. However, fresh clinical isolates of HCMV are not cell free and the production of cell-free virus from cells infected with fresh clinical isolates requires multiple passage in cell culture followed by the release of virus by freeze-thaw or sonication procedures. Experiments are in progress to determine the feasibility of using cell-free virus derived from clinical isolates in this rapid, quantitative assay.

Further development of this technology could yield a broadly applicable procedure for the determination of drug sensitivity of any organism that replicates in cultured cells and for which appropriate monoclonal antibodies directed toward pathogen-associated antigens are available. The initial cost of a flow cytometer will make this assay available only to large laboratories with this sophisticated equipment. However, for those laboratories with flow cytometers, of which there are many, savings in time and labor may make this assay a viable replacement for the standard plaque reduction assay.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Mary Ann Czerniewski, Ann Ogden-McDonough, Betty A. Olson, William Kabat, Janelle Hunt, and Elizabeth Dennis for technical assistance.

This work was supported in part by grants AI32367 and AI41690 and contracts NO1-HD33162, NO1-AI35172, and NO1-AI15104 from the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.AIDS Clinical Trials Group. Antiviral susceptibility assay for CMV: plaque reduction method. ACTG Viral Co-Pathogens Working Group consensus procedure. AIDS Clinical Trials Group.

- 2.Arts E, Wainberg M A. Mechanisms of nucleoside analog antiviral activity and resistance during human immunodeficiency virus reverse transcription. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:527–540. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.3.527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chatis P, Crumpacker C S. Resistance of herpesviruses to antiviral drugs. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:1589–1595. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.8.1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chou S, Erice A, Jordan M C, Vercellotti G M, Michels K R, Talarico C L, Stanat S C, Biron K K. Analysis of the UL97 phosphotransferase coding sequence in clinical cytomegalovirus isolates and identification of mutations conferring ganciclovir resistance. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:576–583. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.3.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chou S, Geuntzel S, Michels K R, Miner R C, Drew W L. Frequency of UL97 phosphotransferase mutations related to ganciclovir resistance in clinical cytomegalovirus isolates. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:239–254. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.1.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chou S, Marousek G, Guentzel S, Follansbee S E, Poscher M E, Lalezari J P, Miner R C, Drew W L. Evolution of mutations conferring multidrug resistance during prophylaxis and therapy for cytomegalovirus disease. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:786–789. doi: 10.1086/517302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crumpacker C S. Molecular targets of antiviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:163–172. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198907203210306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crumpacker C S. Ganciclovir. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:721–729. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199609053351007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crumpacker, C. S. 1996. Drug resistance in cytomegalovirus: current knowledge and implications for patient management. J. Acquired Immune Defic. Syndr. 12(Suppl. 1):S18. [PubMed]

- 10.D’Aquila R T, Johnson V A, Wells S L, Japour A J, Kurtizkes D R, DeGruttola V, Reichelderfer P S, Combs R W, Crumpacker C S, Kahn J O, Richman D D for the AIDS Clinical Trials Group Protocol 116B/117 Team and the Virology Committee Resistance Working Group. Zidovudine resistance and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 disease progression during antiretroviral therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:401–408. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-6-199503150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D’Argenio D Z, Schumitzky A. ADAPT II user’s guide: pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic systems analysis software. Los Angeles, Calif: Biomedical Simulations Resources; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Clercq E. In search of a selective antiviral chemotherapy. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:674–693. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.4.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drew W L, Minor R C, Busch D F, Follansbee S E, Gullett J, Mehalko S G, Gordon S M, Owen W F, Jr, Mathews T R, Buhles W C, DeArmond B. Prevalence of resistance in patients receiving ganciclovir for serious cytomegalovirus infection. J Infect Dis. 1991;163:716–719. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.4.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elmendorf S, McSharry J J, Laffin J, Fogleman D, Lehman J M. Detection of an early cytomegalovirus antigen with two color quantitative flow cytometry. Cytometry. 1988;9:254–260. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990090311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Erice A, Gil-Roda C, Perez J-L, Balfour H H, Jr, Sannerud K J, Hanson M N, Boivin G, Chou S. Antiviral susceptibilities and analysis of UL97 and DNA polymerase sequences of clinical cytomegalovirus isolates from immunocompromised patients. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:1087–1092. doi: 10.1086/516446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Erlich K S, Mills J, Chatis P, Mertz G J, Bush D, Follansbee S, Grant R M, Crumpacker C S. Acyclovir-resistant HSV infections in patients with AIDS. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:293–296. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198902023200506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gerna F, Sarasini A, Percivalle E, Zavattoni M, Baldanti F, Revello M G. Rapid screening for resistance to ganciclovir and foscarent resistance of primary isolates of human cytomegalovirus from culture positive blood samples. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:738–741. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.3.738-741.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirsch M S, Kaplan J C, D’Aquila R T. Antiviral agents. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P, editors. Fields virology. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven Press; 1996. pp. 431–466. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Japour A J, Mayer D L, Johnson V A, Kuritzkes D R, Beckett L A, Arduino J-M, Lane J, Black R J, Reichelderfer P S, D’Aquila R T, Crumpacker C S the RV-43 Study Group; the AIDS Clinical Trials Group Virology Committee Resistance Working Group. Standardized peripheral blood mononuclear cell culture assay for determination of drug susceptibilities of clinical human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:1095–1101. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.5.1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Japour A J, Wells S L, D’Aquila R T, Johnson V A, Richman D D, Coombs R W, Reichelderfer P S, Kahn J O, DeGruttola V, Crumpacker C S, Kuritzkes D T for the AIDS Clinical Trials Group 116B/117 Study Team and the Virology Committee Resistance Working Group. Prevalence and clinical significance of zidovudine resistance mutations in human immunodeficiency virus isolated from patients following long-term zidovudine treatment. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:1172–1179. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.5.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jokela J, Erice A, Stanat S, Drew W L, Spector S, Weinberg A, Gilliam B, Yen-Lieberman B, Manischewitz J, Pollard R, Landry M, Chou S, Biron K, Reichelderfer P S, Britt W, Crumpacker C. Abstracts of the 2nd National Conference on Human Retroviruses. 1995. A standardized plaque reduction assay for CMV antiviral susceptibility, abstr. 283. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lipson S M, Soni M, Biondo F X, Shepp D H, Kaplan M H, Sun T. Antiviral susceptibility testing-flow cytometric analysis (AST-FCA) for the detection of cytomegalovirus drug resistance. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1997;28:123–129. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(97)00040-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lurain N S, Ammons H C, Kapell K S, Yeldandi V V, Garrity E R, O’Keefe J P. Molecular analysis of human cytomegalovirus strains from two lung transplant recipients with the same donor. Transplantation. 1996;62:497–502. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199608270-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lurain N S, Thompson K D, Holmes E W, Read G S. Point mutations in the DNA polymerase gene of human cytomegalovirus that result in resistance to antiviral agents. J Virol. 1992;66:7146–7152. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.12.7146-7152.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McSharry J J. Uses of flow cytometry in virology. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1994;7:576–604. doi: 10.1128/cmr.7.4.576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McSharry J J. Flow cytometry based antiviral resistance assays. Clin Immunol Newsl. 1995;15:113–119. [Google Scholar]

- 27.McSharry J J, Lurain N S, Drusano G L, Landay A, Manischewitz J, Nokta M, O’Gorman M, Shapiro H M, Weinberg A, Reichelderfer P S, Crumpacker C S. Flow cytometric determination of ganciclovir susceptibility of human cytomegalovirus clinical isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:958–964. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.4.958-964.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mocarski E S., Jr . Cytomegaloviruses and their replication. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Fields virology. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippencott-Raven Publishers; 1996. pp. 2447–2492. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pavic I, Hartmann A, Zimmermann A, Michel D, Hampl W, Schleyer I, Mertens T. Flow cytometric analysis of herpes simplex virus type 1 susceptibility to acyclovir, ganciclovir, and foscarnet. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2686–2692. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.12.2686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pepin J-M, Simon F, Dussault A, Collin G, Dazza M-C, Brun-Vezinet F. Rapid detection of human cytomegalovirus susceptibility to ganciclovir directly from clinical specimen primocultures. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:2917–2920. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.11.2917-2920.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosenthal K S, Hodnichak C N, Summers J L. Flow cytometric evaluation of anti-herpes drugs. Cytometry. 1987;8:392–395. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990080408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schols D, Snoeck R, Neyts J, DeClercq E. Detection of immediate early, early and late antigens of human cytomegalovirus by flow cytometry. J Virol. 1989;26:247–254. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(89)90107-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stanat S C, Reardon J E, Erice A, Jordan M C, Drew W L, Biron K K. Ganciclovir-resistant cytomegalovirus clinical isolates: mode of resistance to ganciclovir. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:2191–2197. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.11.2191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wentworth B B, French L. Plaque assay of cytomegalovirus strains of human origin. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1970;135:253–258. doi: 10.3181/00379727-135-35031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]