Abstract

International donors and UN agencies emphasise the importance of human rights as a key determinant of HIV vulnerability and of access, uptake and retention in HIV prevention and treatment services. Yet, the extent to which HIV researchers are incorporating rights into their research, the specific rights being examined and the frequency of research assessing rights-based approaches, is unknown.

Methods

We examined all articles published in the five highest impact-factor HIV journals: (1) Lancet HIV; (2) AIDS and Behavior; (3) AIDS; (4) Journal of the International AIDS Society (JIAS); and (5) Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (JAIDS), between 1 January 2017 and 31 December 2022, for reference to ‘human right(s)’ or ‘right(s)’. We analysed articles to assess: (1) what populations were identified in relation to specific human rights concerns; (2) what specific rights were mentioned; (3) whether researchers cited specific legal frameworks; and (4) if and what types of rights-based interventions were examined.

Results

Overall, 2.8% (n=224) of the 8080 articles reviewed included a mention of ‘human right(s)’ or ‘right(s)’. Forty-two per cent of these (n=94) were original research articles. The most common key population discussed was men who have sex with men (33 articles), followed by sex workers (21 articles) and transgender people (14 articles). Of the 94 articles, 11 mentioned the right to health and nine referenced reproductive rights. Few articles identified a specific authority—whether in national, regional or international law—for the basis of the rights cited. Fourteen articles discussed rights-based interventions.

Conclusion

Despite global recognition of the importance of human rights to HIV outcomes, few HIV researchers publishing in the top five cited HIV journals include attention to human rights, or rights-based interventions, in their research. When rights are mentioned, it is often without specificity or recognition of the legal basis for human rights.

Keywords: HIV, systematic review

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

The protection of human rights is recognised by international donors and UN agencies as critical to achieving HIV goals and as central to multiyear strategies to achieve an ‘end of AIDS’.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Few articles published between 2017 and 2022 in five HIV journals examine the impact of human rights interventions, or specific rights abuses, on HIV outcomes. Those that do mention human rights rarely identify specific rights or their legal source.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

Positive or negative human rights environments can act as powerful structural mediators of biomedical, behavioural and community-based HIV interventions. More detailed attention to rights environments and evaluation of rights-based interventions may help explain variation in progress to end AIDS and inform more effective approaches.

Introduction

The 1983 Denver Principles, developed by ‘the advisory committee of the People with AIDS’, articulated five rights of those living with HIV:

(The right) to as full and satisfying sexual and emotional lives as anyone else.

(The right) to quality medical treatment and quality social service provision without discrimination of any form including sexual orientation, gender, diagnosis, economic status or race.

(The right) to full explanations of all medical procedures and risks, to choose or refuse their treatment modalities, to refuse to participate in research without jeopardising their treatment and to make informed decisions about their lives.

(The right) to privacy, to confidentiality of medical records, to human respect and to choose who their significant others are.

(The right) to die—and to LIVE—in dignity.1

These rights, to health, to non-discrimination, to information, to privacy and confidentiality and to dignity, are core principles of international human rights treaties, starting with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 1948.2 The Denver Principles put forward a radical subjectivity and launched a recognition that addressing the HIV epidemic required respect for human rights and partnership with communities most affected.

Following the example of anticolonial movements in India, the US civil rights movement, the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa and the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo in Argentina, HIV activists engaged in civil disobedience and at times used dramatic tactics—die-ins, blocking or storming various government office buildings and interrupting scientific conferences and news programmes—to draw attention and to call for respect for rights and redress for injustice.3 Community-based organisations and non-governmental organisations designed rights-based interventions, addressing stigma and discrimination and targeting legal and political determinants that influence vulnerability to infection and access to prevention and treatment.4 Realising human rights and gender equality was also identified by the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS (UNAIDS) as critical to achieve an end to the HIV epidemic.5

Yet, these goals have been elusive and even in places where overall HIV incidence is decreasing the continued political and social exclusion of key populations—sex workers, transgender people, gay and bisexual men and other men who have sex with men, people who inject drugs, and prisoners—has hindered progress in efforts to end the AIDS.6 According to UNAIDS, key populations and their sexual partners accounted for 70% of the new HIV infections in 2021, despite being less than 5% of the global population.5 Punitive laws and practices that target these populations can increase their vulnerability to infection, limit access to treatment and threaten their lives.6 Thus, UNAIDS, the UN Development Programme (UNDP) and the Global Fund to Fight HIV, TB and malaria promote programmes to address inequities, social exclusion and human rights in their HIV strategic plans.7–9 Specific human rights indicators for achieving these goals include that less than 10% of countries criminalise sex work, the possession of small amounts of drugs or same-sex sexual behaviour. Another human rights-related indicator is that less than 10% of people living with HIV and key populations should lack access to legal services by 2025.9

However, despite these rights-based programmes, indicators and goals, human rights research published in HIV focused academic journals—including the analysis of the impact of rights violations and rights protections on vulnerability to HIV infection, as well as access to and retention in treatment—is rare. To better understand the degree and the characteristics of HIV and human rights research published in leading HIV journals, we conducted a targeted literature review of the five most-cited HIV journals.

Methods

We searched SCOPUS for articles published in the five highest impact-factor HIV journals: (1) Lancet HIV; (2) AIDS and Behavior; (3) AIDS; (4) Journal of the International AIDS Society (JIAS); and (5) Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (JAIDS), between 1 January 2017 and 31 December 2022, containing the terms ‘human right(s)’ or ‘right(s)’.

Among articles initially identified, we reviewed each article and excluded those that did not include at least one of the terms within the main body of the article (excluding references, author’s affiliations or copyright text). We next divided articles into research articles or other formats (eg, commentary, profile, letters, viewpoints, etc.).

Finally, we analysed each remaining research article to assess: (1) what populations were identified in relation to specific human rights concerns; (2) what specific rights were referenced; (3) whether researchers referenced specific legal frameworks; and (4) if and what types of rights-based interventions were examined. Articles were examined independently by each author. Differences in categorization or interpretation were resolved through discussion until consensus was reached.

Results

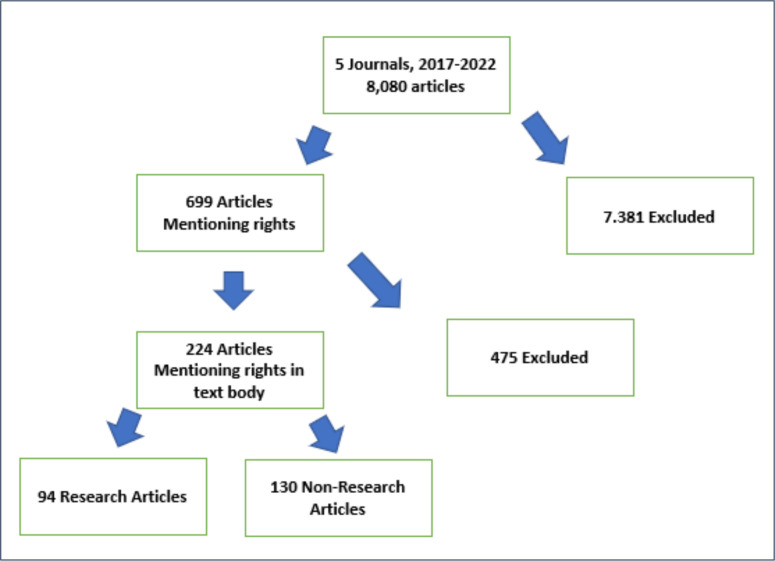

Overall, 2.8% (n=224) of the 8080 articles published in the five most highly cited journals over a 6-year period included a mention of ‘human right(s)’ or ‘right(s)’. Forty-two per cent of these (n=94) were original research articles and 58% (n=130) were of another format (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Selection of articles.

Examining the number of research articles mentioning human rights by journal and year, we found that the overall number of articles varied little over the time period (average: 15.7; range: 10–21). More biomedically oriented HIV journals, such as AIDS and Lancet HIV, rarely published research articles mentioning human rights, while broader interdisciplinary journals such as JIAS and JAIDS published research articles mentioning human rights somewhat more frequently, and AIDS and Behavior, which includes an explicit focus on behavioural research in its stated aims, published more than 60% of all articles identified (table 1).

Table 1.

Number of research articles Mentioning ‘human right(s)’ or ‘rights’ in main text by journal and year

| Year | JIAS | Lancet HIV | AIDS | JAIDS | AIDS and Behavior | Total |

| 2017 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 5 | 14 |

| 2018 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 12 | 21 |

| 2019 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 10 | 16 |

| 2020 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 15 |

| 2021 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 10 |

| 2022 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 18 |

| Total | 16 (17%) | 5 (5%) | 1 (1%) | 14 (15%) | 58 (62%) | 94 (100%) |

Further analysis of the 94 research articles mentioning ‘human right(s)’ or ‘right(s)’ examined the specific populations studied, the specific rights referred to and the extent to which authors referenced specific legal frameworks or rights-based interventions.

Whose rights?

Articles mentioning rights most often focused on men who have sex with men (33 articles), followed by sex workers (often female sex workers) (21 articles) and transgender people (usually transgender women) (14 articles). Adolescents (12 articles), people who inject drugs (7 articles), women (5 articles), serodiscordant couples (4 articles), potential parents or parents living with HIV (3 articles), people who are incarcerated (2 articles), refugees and migrant population (2 articles) and older adults (1 articles) were also identified. Thirteen articles mentioned the rights of people living with HIV generally.

What rights?

The specific rights discussed varied widely. Of the 94 articles referring to rights, 11 mentioned the right to health, either broadly or less often with mention of specific elements of the right to health. However, even when articles were more specific, authors did not always define the right to health in a comprehensive manner, as in an article in JIAS that referred to the right to inclusive healthcare and necessary and appropriate health services10—components of the right to health that more fully include rights of non-discrimination and the availability, accessibility, acceptability and of high quality of healthcare.11

Nine articles referenced reproductive rights for serodiscordant couples or women living with HIV and family planning.12–20 This was also referred to by some authors as the ‘right to bear children’. Sexual rights were often mentioned without more specificity. For example, the only substantive reference to rights in a 2022 article that explored the role of pleasure in sexual decision-making for transgender sex workers, was the claim that ‘prevention interventions must …include considerations of sexual well-being, satisfaction and rights’.21 The authors did not explicitly define sexual rights or identify bodily autonomy as a right, nor how consideration of sexual rights should be addressed in prevention interventions.

Another vague reference to human rights was mention of the ‘right to refuse’, which was discussed in eight articles, some referring to the right to refuse treatment, right to refuse testing and the right to confidentiality (such as not sharing test results without consent). There were also five articles referencing human rights violations without identifying a specific right being violated: for example, a 2017 article on the impact of physical and sexual violence on female sex workers in Cote d’Ivoire mentions that ‘sustained violence’ is a human rights violation.22

What authority is identified for human rights?

Few articles reviewed identified a specific authority—whether in national, regional or international law—for the basis of the rights cited. For example, articles included claims such as ‘people living with HIV have the right to healthcare’ or ‘interventions must protect human rights’ without mentioning specific government obligations or limitations of the referenced rights. Among articles discussing men who have sex with men and transgender women, there were frequent references to ‘LGBT rights’ as a way to describe a broad range of rights (both civil and political rights as well as economic and social rights) that are relevant to the discrimination and criminalisation that many LGBTQ+ individuals face.

As an example of how rights are discussed discursively instead of within an analytical framework, in Johnston et al,23 the authors focus on the high prevalence of HIV among MSM and sexual minority adolescent boys in Indonesia. While the authors mention in the abstract that ‘structural factors…restrict rights of young MSM’, no further mention of rights is made in the article, nor analysis of how rights restrictions specifically influence HIV risk.23 In the study by Vu and Misra,24 which focused on female sex workers in Tanzania, rights are mentioned three times. Twice the authors mention the need to promote human rights of sex workers, and once they mention the need for sex worker education on rights. Although the authors mention rights in the context of the need to decriminalise sex work and prevent police harassment, there is no mention of the specific rights, or the basis of those rights, that would ground such claims.24

Specific legal frameworks (or guidelines) were mentioned in four of the reviewed research articles. A 2018 paper in AIDS and Behavior that examined the risk environment for female sex workers discussed labour rights with definitions from the International Labor Organization.25 Another paper in AIDS and Behavior used WHO and UNAIDS guidelines for sexual and reproductive rights in their discussion of women living with HIV who wish to become parents.16 A 2019 paper in AIDS and Behavior on HIV risk factors and syndemic experiences of the LGBTQ+ community in Jamaica mentions guidelines from the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and specific legal statutes in Jamaica.26 A 2018 paper on the HIV treatment cascade in South Africa mentioned their national Bill of Rights, which includes the right to live free from discrimination.27 None of the articles reviewed referenced international human rights treaties, the foundation of modern human rights law.

How are rights-based HIV interventions described?

Fourteen of the 94 articles which mention rights discussed rights-based interventions, but only four discussed these interventions in depth. Most mentioned rights intervention in the introduction or conclusion in a general statement like ‘rights-based interventions are needed’. An exception was a 2021 paper in AIDS and Behavior on the results of the Advocacy and other Community Tactics Project, which addressed barriers to HIV care for gay and bisexual men and transgender women in seven countries (Burundi, Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Zimbabwe, Dominican Republic and Jamaica).28 An article by DeBeck et al, which presented a systematic review of criminalisation of people who use drugs, also includes a brief mention of human rights-based approaches to harm reduction in Australia.29

Discussion

In 1996, The Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights and UNAIDS adopted International Guidelines on HIV and Human Rights.30 They were intended to illustrate a rights-based framework to guide the response to HIV, recognising that an extensive array of human rights affect vulnerability to HIV infection and that protecting these rights are critical to a successful HIV response (box 1).

Box 1. Key human rights relevant to the HIV response.

The rights to non-discrimination, equal protection and equality before the law.

The right to life.

The right to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health.

The right to liberty and security of person.

The right to freedom of movement.

The right to seek and enjoy asylum.

The right to privacy.

The right to freedom of opinion and expression and the right to freely receive and impart information.

The right to freedom of association.

The right to work.

The right to marry and to found a family.

The right to equal access to education.

The right to an adequate standard of living.

The right to social security, assistance and welfare.

The right to share in scientific advancement and its benefits.

The right to participate in public and cultural life.

The right to be free from torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.

However, our review found that HIV research, reflected in five prominent HIV journals, rarely identifies rights as determinants. When they do, rights are often referred to in vague ways and with little awareness of their relation to law and state obligation. In the articles we reviewed, rights were most often mentioned only briefly, in the introduction or conclusion of the article.

When rights were mentioned, they were often attributed to the rights of specific groups rather than the experience of individuals—for example, as an exposure variable. This both weakens any analysis of the impact of human rights on HIV vulnerability and ignores the intersectional nature of individuals assigned to a specific ‘key population’. Less often, broad mention is made to the importance of interventions that are ‘rights-based’, omitting details of what rights and how interventions can increase respect for individuals’ rights. Without research clearly linking the protection of human rights to the vulnerability of individuals to HIV infection and to treatment access, uptake and retention, HIV researchers, programme implementors and donors are only able to invoke right-based approaches rather than measure their effectiveness.

Framing the vulnerability of a specific population in terms of specific human rights both clarifies potential areas for intervention and elucidates the obligations of state actors. For example, criminalising homosexuality, as in some countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, violates the rights of LGBTQ+ individuals under national, regional and international human rights law, including the right to health, as well as the rights to freedom of expression and association, privacy, equality and non-discrimination, guaranteed in both regional agreements (such as the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, the Maputo Protocol on the Rights of Women in Africa and the East African Community HIV and AIDS Prevention and Management Act), and in international treaties (such as the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women).

Access to medicines (including harm reduction, antiretroviral medicines and pre-exposure prophylaxis) has also been recognised as an essential component of the right to health.31 The Committee against Torture, the Special Rapporteurs on Torture and on Health and the Committee on the Rights of the Child have all raised concerns about the failure to provide adequate and appropriate health services to people who use drugs and the use of detention and forced labour in lieu of voluntary, community-based and evidence-based approaches, which they identify as potentially amounting to cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment.32 The right to HIV medicines and the right to be free from violence have similarly been articulated by human rights experts, drawing on state obligations in international treaties, regional agreements and national constitutions.33 34

While it is easier for researchers to include a passing mention of the rights of a population or the right to health than to identify where these rights originate, what authority they have, and how the realisation of these rights affect HIV vulnerability, vague references to rights do little to advance our understanding of HIV vulnerability or of effective HIV interventions. Similarly, referencing terms such as ‘social justice’ or ‘equity’ without further context, has limited value in advancing our knowledge of vulnerability and effective responses.

Despite the lack of attention to rights in the journal articles reviewed, scholars are critically examining the impact of human rights at an ecological and individual level. Studies have examined the correlation between human rights treaty ratification by countries and child survival and other health indicators.35 36 Researchers have also used modelling to examine the relationship between the criminalisation of key populations such as sex workers, LGBTQ+ populations and persons who use drugs and HIV prevalence. For example, Shannon et al found that the elimination of sexual violence against sex workers in Kenya and Canada could avert 17% and 20% of HIV infections, respectively, over a decade. Decriminalisation of sex work would avert 33%–46% of HIV infections, greater than the number of infections averted from scaling up ART among FSWs and their clients or increasing coverage of sex worker-led outreach.37

Strathdee et al, found that over a 5-year period, HIV prevalence could be reduced by 41% in Odessa (Ukraine), 43% in Karachi (Pakistan) and 30% in Nairobi (Kenya) through a 60% reduction of the unmet need of programmes for opioid substitution, needle exchange and antiretroviral therapy. Elimination of laws prohibiting opioid substitution with concomitant scale-up could prevent 14% of HIV infections in Nairobi.38 In Zambia, research on HIV and TB in prisons examined access to testing and treatment as well as variables related to the right to due process (including the length of time before detainees saw a judge, access to bond or bail, and overall length of time awaiting trial).39

Each of these interventions could be defined without regard to human rights, but each is firmly grounded in protecting rights—to the highest attainable standard of health, freedom from violence, access to evidence-based medicines, and so on. By identifying these interventions as both effective and rights-based, governments are less able to dismiss their obligation to implement these interventions. International donor agencies, such as PEPFAR and the Global Fund, have increasingly recognised the importance of rights-based interventions that promote rights literacy and facilitate the protection of individual rights.

For example, in Mozambique, PEPFAR has funded initiatives to train healthcare providers in human rights, implement community-led monitoring of human rights violations, increase patient legal literacy and address harmful gender norms.40 The Global Fund to Fight HIV, TB and malaria launched in 2017 the Breaking Down Barriers initiative, that provides funding for programmes addressing human rights barriers to HIV, TB and malaria services in 20 countries. The initiative has supported the training of sex workers and other key populations to serve as peer paralegals, to prevent police harassment and intimidation and to advocate for access to prevention and treatment as well as the right to safe labour practices and sexual health services.41 As more international funding is placed into these types of programmes, it is critical that HIV researchers measure and report on their impact.

Conclusion

From the start of the HIV epidemic, HIV activists have emphasised that protecting human rights is critical to HIV prevention and ensuring access to treatment. They have also highlighted the importance of human rights to reducing global health inequities and to mobilising social movements. Researchers from a broad range of disciplines have examined these relationships, describing mechanisms of vulnerability, political determinants of access to HIV prevention and treatment and innovative rights-based interventions.42–58 Yet, between 2017 and 2022, the most cited HIV journals rarely mentioned human rights, and when rights were mentioned, they were nearly always referred to imprecisely and without reference to their legal basis.

Explicitly identifying human rights, as well as the state obligations related to them, is needed to ‘close the gap’ in reaching global HIV goals, and in furthering the development of new approaches to global health practice.59 Identifying human rights as a determinant of health, and then building interventions that promote human rights and facilitate redress for those whose rights have been violated fosters accountability of governments (and government actors such as police and health workers), donors, corporations and others whose power allow them to act with impunity. This struggle for freedom against the abuse of power and demand for local, autonomous decision-making is also at the heart of efforts to decolonise global health, and the longstanding work of activists demanding community empowerment and decision-making. Studying the relationship between human rights and HIV prevention and treatment helps render visible the political and social responses needed to end AIDS. By aligning HIV efforts with an explicit understanding of human rights, HIV interventions will be able to expand their reach and increase their effectiveness.

Acknowledgments

KH would like to acknowledge the financial support provided by the Dornsife School of Public Health and the Graduate College Doctoral Fellowship Program for her doctoral studies.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Stephanie M Topp

Twitter: @joeamon

Contributors: JJA conceptualised the article. KH and JJA conducted the literature review and developed the first draft and subsequent revision. JJA accepts full responsibility for the finished work and the decision to publish and had access to all data.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

No data are available.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Advisory Committee of People With AIDS . The Denver principles [Internet]. 1983. Available: https://data.unaids.org/pub/externaldocument/2007/gipa1983denverprinciples_en.pdf [Accessed 11 Nov 2022].

- 2.United Nations General Assembly . Universal declaration of human rights. Internet; 1948, Report No: 302. United Nations 14–25.Available: http://www.multiculturalaustralia.edu.au/doc/unhrights_1.pdf

- 3.Amon JJ, Friedman E. Human rights advocacy for global health. In: Gostin LO, Meier BM, eds. Foundations of Global Health & Human Rights. New York: Oxford Univ Press, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4.UNAIDS . Key programmes to reduce stigma and discrimination and increase access to justice in national HIV responses [Internet]. Geneva Switzerland:; 2012. Available: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/Key_Human_Rights_Programmes_en_May2012_0.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 5.IN DANGER . Internet. UNAIDS Global AIDS Update 2022. Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, 2022. Available: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2022-global-aids-update-summary_en.pdf [accessed 17 Sep 2022]. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amon JJ, Eba P, Sprague L, et al. Defining rights-based indicators for HIV epidemic transition. PLoS Med 2018;15:e1002720. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.UNDP . Internet. Connecting the Dots: Towards a More Equitable, Healthier and Sustainable Future: UNDP HIV and Health Strategy 2022-2025. Geneva Switzerland: United Nations Development Programme, 2022. Available: https://www.undp.org/publications/connecting-dots-towards-more-equitable-healthier-and-sustainable-future-undp-hiv-and-health-strategy-2022-2025 [accessed 30 Oct 2022]. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Global Fund . Internet. Fighting Pandemics and Building a Healthier and More Equitable World: Global Fund Strategy (2023-28). The Global Fund to Fight HIV, TB, and Malaria, 2022. Available: https://www.theglobalfund.org/en/strategy/ [Google Scholar]

- 9.UN AIDS . Global AIDS strategy 2021-2026 [Internet]. 2021. Available: https://www.unaids.org/en/Global-AIDS-Strategy-2021-2026 [Accessed 12 Jul 2022].

- 10.van der Elst EM, Mudza R, Onguso JM, et al. A more responsive, multi-pronged strategy is needed to strengthen HIV healthcare for men who have sex with men in a decentralized health system: qualitative insights of a case study in the Kenyan coast. J Int AIDS Soc 2020;23:e25597. 10.1002/jia2.25597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Office of the High Commisioner for Human Rights . General Comment No. 14 on the Right to the Highest Attainable Standard of Health [Internet]. Geneva, 2000. Available: chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.refworld.org/pdfid/4538838d0.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwartz SR, Bassett J, Mutunga L, et al. HIV incidence, pregnancy, and implementation outcomes from the Sakh’Umndeni safer conception project in South Africa: a prospective cohort study. The Lancet HIV 2019;6:e438–46. 10.1016/S2352-3018(19)30144-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simon KR, Flick RJ, Kim MH, et al. Family testing: an index case finding strategy to close the gaps in pediatric HIV diagnosis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2018;78 Suppl 2:S88–97. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mindry D, Wanyenze RK, Beyeza-Kashesya J, et al. Safer conception for couples affected by HIV: structural and cultural considerations in the delivery of safer conception care in Uganda. AIDS Behav 2017;21:2488–96. 10.1007/s10461-017-1816-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mantell JE, Cooper D, Exner TM, et al. Emtonjeni—A structural intervention to integrate sexual and reproductive health into public sector HIV care in Cape town, South Africa: results of a phase II study. AIDS Behav 2017;21:905–22. 10.1007/s10461-016-1562-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duff P, Kestler M, Chamboko P, et al. Realizing women living with HIV’s reproductive rights in the era of ART: the negative impact of non-Consensual HIV disclosure on pregnancy decisions amongst women living with HIV in a Canadian setting. AIDS Behav 2018;22:2906–15. 10.1007/s10461-018-2111-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goggin K, Hurley EA, Wagner GJ, et al. Changes in providers’ self-efficacy and intentions to provide safer conception counseling over 24 months. AIDS Behav 2018;22:2895–905. 10.1007/s10461-018-2049-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khidir H, Psaros C, Greener L, et al. Developing a safer conception intervention for men living with HIV in South Africa. AIDS Behav 2018;22:1725–35. 10.1007/s10461-017-1719-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stanton AM, Bwana M, Owembabazi M, et al. Sexual and relationship benefits of a safer conception intervention among men with HIV who seek to have children with serodifferent partners in Uganda. AIDS Behav 2022;26:1841–52. 10.1007/s10461-021-03533-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mathenjwa M, Khidir H, Milford C, et al. Acceptability of an intervention to promote viral suppression and serostatus disclosure for men living with HIV in South Africa: qualitative findings. AIDS Behav 2022;26:1–12. 10.1007/s10461-021-03278-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Naz-McLean S, Clark JL, Reisner SL, et al. Decision-making at the intersection of risk and pleasure a qualitative inquiry with Trans women engaged in sex work in Lima Peru. AIDS Behav 2022;26:843–52. 10.1007/s10461-021-03445-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lyons CE, Grosso A, Drame FM, et al. Physical and sexual violence affecting female sex workers in Abidjan, Côte D’Ivoire: prevalence, and the relationship with the work environment, HIV and access to health services. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017;75:9–17. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnston LG, Soe P, Widihastuti AS, et al. Alarmingly high HIV prevalence among adolescent and young men who have sex with men (MSM) in urban Indonesia. AIDS Behav 2021;25:3687–94. 10.1007/s10461-021-03347-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vu L, Misra K. High burden of HIV Syphilis and HSV-2 and factors associated with HIV infection among female sex workers in Tanzania implications for early treatment of HIV and pre-exposure prophylaxis (prep). AIDS Behav 2018;22:1113–21. 10.1007/s10461-017-1992-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leddy AM, Underwood C, Decker MR, et al. Adapting the risk environment framework to understand substance use, gender-based violence, and HIV risk behaviors among female sex workers in Tanzania. AIDS Behav 2018;22:3296–306. 10.1007/s10461-018-2156-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Logie CH, Wang Y, Marcus N, et al. Syndemic experiences, protective factors, and HIV Vulnerabilities among lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender persons in Jamaica. AIDS Behav 2019;23:1530–40. 10.1007/s10461-018-2377-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scheibe A, Grasso M, Raymond HF, et al. Modelling the UNAIDS 90-90-90 treatment cascade for gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men in South Africa: using the findings of a data triangulation process to map a way forward. AIDS Behav 2018;22:853–9. 10.1007/s10461-017-1773-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller RL, Rutledge J, Ayala G. Breaking down barriers to HIV care for gay and bisexual men and transgender women: the advocacy and other community tactics (ACT) project. AIDS Behav 2021;25:2551–67. 10.1007/s10461-021-03216-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DeBeck K, Cheng T, Montaner JS, et al. HIV and the criminalisation of drug use among people who inject drugs: a systematic review. Lancet HIV 2017;4:e357–74. 10.1016/S2352-3018(17)30073-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS . International Guidelines on HIV/AIDS and Human Rights [Internet]. Geneva: United Nations, 2006. Available: http://data.unaids.org/Publications/IRC-pub07/jc1252-internguidelines_en.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jürgens R, Csete J, Amon JJ, et al. People who use drugs, HIV, and human rights. The Lancet 2010;376:475–85. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60830-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Amon JJ, Pearshouse R, Cohen JE, et al. Compulsory drug detention in East and Southeast Asia: evolving government, UN and donor responses. Int J Drug Policy 2014;25:13–20. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bhatt V. n.d. A human right to HIV prevention: pre-exposure prophylaxis and the right to health. SSRN Journal 10.2139/ssrn.3976856 Available: 10.2139/ssrn.3976856 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Carvalho B da, Fonseca F, Villardi P, et al. Fighting for prep: the politics of recognition and redistribution to access AIDS medicines in Brazil. In: Bernays S, Bourne A, Kippax S, et al., eds. Remaking HIV Prevention in the 21st Century: The Promise of TasP, U=U and PrEP [Internet]. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2021: 73–87. 10.1007/978-3-030-69819-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Palmer A, Tomkinson J, Phung C, et al. Does ratification of human-rights treaties have effects on population health The Lancet 2009;373:1987–92. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60231-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tait CA, Parnia A, Zewge-Abubaker N, et al. Did the UN convention on the rights of the child reduce child mortality around the world? an interrupted time series analysis. BMC Public Health 2020;20:707. 10.1186/s12889-020-08720-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shannon K, Strathdee SA, Goldenberg SM, et al. Global epidemiology of HIV among female sex workers: influence of structural determinants. The Lancet 2015;385:55–71. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60931-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Strathdee SA, Hallett TB, Bobrova N, et al. HIV and risk environment for injecting drug users: the past, present, and future. The Lancet 2010;376:268–84. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60743-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Todrys KW, Amon JJ, Malembeka G, et al. Imprisoned and imperiled: access to HIV and TB prevention and treatment, and denial of human rights, in zambian prisons. J Int AIDS Soc 2011;14:8. 10.1186/1758-2652-14-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.PEPFAR-Mozambique . Country operational plan (COP 2022): strategic direction summary [Internet]. US State Department; 2022. Available: https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Mozambique-COP22-SDS-.pdf [Accessed 2 Jan 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hinman K, Sun N, Amon JJ. Ensuring access to justice: the need for community paralegals to end AIDS by 2030. J Int AIDS Soc 2023;26:e26146. 10.1002/jia2.26146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pillay N, Chimbga D, Van Hout MC. Gender inequality, health rights, and HIV/AIDS among women prisoners in Zimbabwe. Health Hum Rights 2021;23:225–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kendall T, Capin JA, Damji N, et al. Community mobilization to promote and protect the sexual and reproductive rights of women living with HIV in Latin America. Health Hum Rights 2020;22:213–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sircar NR, Maleche AA. Assessing a human rights-based approach to HIV testing and partner notification in Kenya: a qualitative study to examine how Kenya’s policies and practices implement a rights-based approach to health. Health Hum Rights 2020;22:167–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Andrews C, Reuter TK, Marsh L, et al. Intimate partner violence, human rights violations, and HIV among women in Nairobi, Kenya. Health Hum Rights 2020;22:155–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Logie CH, Lacombe-Duncan A, Kenny KS, et al. Associations between police harassment and HIV vulnerabilities among men who have sex with men and transgender women in Jamaica. Health Hum Rights 2017;19:147–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Amon JJ, Kasambala T. Structural barriers and human rights related to HIV prevention and treatment in Zimbabwe. Glob Public Health 2009;4:528–45. 10.1080/17441690802128321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McGranahan M, Nakyeyune J, Baguma C, et al. Rights based approaches to sexual and reproductive health in low and middle-income countries: a systematic review. PLoS One 2021;16:e0250976. 10.1371/journal.pone.0250976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lyons CE, Schwartz SR, Murray SM, et al. The role of sex work laws and stigmas in increasing HIV risks among sex workers. Nat Commun 2020;11. 10.1038/s41467-020-14593-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Leddy AM, Mantsios A, Davis W, et al. Essential elements of a community empowerment approach to HIV prevention among female sex workers engaged in project Shikamana in Iringa. Culture, Health & Sexuality 2020;22:111–26. 10.1080/13691058.2019.1659999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stangl AL, Singh D, Windle M, et al. A systematic review of selected human rights programs to improve HIV-related outcomes from 2003 to 2015: what do we know? BMC Infect Dis 2019;19:209. 10.1186/s12879-019-3692-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Strömdahl S, Onigbanjo Williams A, Eziefule B, et al. An assessment of stigma and human right violations among men who have sex with men in Abuja, Nigeria. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 2019;19:7. 10.1186/s12914-019-0190-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kerr T, Small W, Ayutthaya PPN, et al. Experiences with compulsory drug detention among people who inject drugs in Bangkok, Thailand: A qualitative study. Int J Drug Policy 2018;52:32–8. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shen T, Csete J. HIV, sex work, and law enforcement in China. Health Hum Rights 2017;19:133–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zahn R, Grosso A, Scheibe A, et al. Human rights violations among men who have sex with men in Southern Africa: comparisons between legal contexts. PLoS One 2016;11:e0147156. 10.1371/journal.pone.0147156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mason K, Ketende S, Peitzmeier S, et al. Stigma, human rights violations, health care access, and disclosure among men who have sex with men in the Gambia. Journal of Human Rights Practice 2015;7:139–52. 10.1093/jhuman/huu026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Decker MR, Crago A-L, Chu SKH, et al. Human rights violations against sex workers: burden and effect on HIV. The Lancet 2015;385:186–99. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60800-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Amon JJ. The political epidemiology of HIV. J Int AIDS Soc 2014;17:19327. doi:19327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cohen J. A time for optimism? Decolonizing the determinants of health [Internet]. Health and Human Rights Journal 2020. Available: https://www.hhrjournal.org/2020/11/a-time-for-optimism-decolonizing-the-determinants-of-health/ [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No data are available.