ABSTRACT

In a context of recently decreasing childhood immunization coverage and low uptake of COVID-19 vaccines in Bulgaria, this study measures vaccine hesitancy among general practitioners (GPs) in the country, as they are central to forming patients’ attitudes. In 2022, a face-to-face survey was conducted through a simple random sample from an exhaustive national database of Bulgarian GPs. This study measured attitudes on vaccine importance, safety, and effectiveness, and attitudes toward the Bulgarian immunization schedule. Information was collected on demographic and GP practice characteristics and possible predictors of vaccine confidence in order to test for associations with attitudes toward immunization. GP attitudes toward vaccines and the immunization schedule in Bulgaria were generally positive. Among 358 respondents, 351 (98%,95%CI96–99%) strongly agreed/agreed that vaccines are important, 352 (98%,95%CI96–99%) that vaccines are effective, and 341 (95%,95%CI93–97%) that vaccines are safe. 347 respondents (97%,95%CI95–98%) affirmed that “it’s good that vaccines from the children’s immunization schedule are mandatory”, and 331 (92%,95%CI89–95%) agreed with the statement “Bulgaria’s childhood immunization has my approval”. Trust in information from official institutions was among the strongest predictors of vaccine confidence. Respondents’ vaccine confidence levels are within the ranges reported by GPs in other European countries and above those reported within the general Bulgarian population. GPs’ vaccine confidence is highly associated with trust in official institutions. It is important to maintain trust in official institutions and to support GPs in communicating vaccine knowledge with patients so that vaccine hesitancy in the general population is countered.

KEYWORDS: Vaccine hesitancy, vaccine hesitancy among GP, vaccine confidence, predictors of vaccine hesitancy, trust

Introduction

Vaccine hesitancy (VH) can manifest in refusal of available vaccines, delay in acceptance, or acceptance with doubts about a vaccine. As a driver of suboptimal vaccination coverage and outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases, the issue has attracted increasing attention from the scientific community. In 2019 VH was recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO) as one of the key threats to global health, and during the COVID-19 pandemic, VH was identified as a driver of low COVID-19 vaccination uptake in some countries.1–6 VH in the general population has been subject to numerous studies,7,8 but fewer studies are focused on general practitioners (GPs), who are a trusted primary source of information on vaccines and have a pivotal role in determining patient behavior.8–17 Detailed studies on VH within various contexts are important for devising effective measures to tackle the issue, as the determinants of VH vary by country.

The Vaccine Confidence Project™ was established in 2010 to better understand growing vaccine skepticism around the world. It measures vaccine confidence through a set of key questions and captures changes through the years, focusing on over 50 countries from all WHO regions of the planet. A comparison of data from this project collected in 2015 and 2022 has demonstrated a global decline in confidence during this period. Significant decreases were identified in 46 out of 55 studied countries.18 The dynamic around the COVID-19 vaccines posed additional challenges to vaccine confidence.19,20 Populations of countries within the WHO European region are more vaccine-hesitant than in other regions.19,20 Eastern European countries in particular are witnessing large reductions in vaccine confidence,17,18 which indicates a need to better understand confidence in this context.

A global vaccine confidence study from 2016 placed Bulgaria among countries with relatively low levels of confidence in the general population, particularly with regard to attitudes toward the safety and effectiveness of vaccines.19,21,22 The latest study for Bulgaria (2022) demonstrated a further decline in confidence. Specifically, respondent agreement with three key statements decreased between 2016 and 2022. In 2016, 78% of respondents agreed that vaccines are important for children, and in 2022 only 63% agreed. Agreement with the statement “Vaccines are safe” fell from 66 to 58%, and agreement with the statement “Vaccines are effective” fell from 73 to 65%.19,21,22 The measured change for Bulgaria was significant.18 In the context of this decline, currently, Bulgaria is one of the countries in the EU that have the lowest levels of trust in the safety and effectiveness of vaccines,17 relatively lower approval of MMR and HPV vaccines, and lowest approval of seasonal influenza vaccine and COVID-19 vaccines.17 It can be concluded that in 2022 the country is one of the member states with the highest level of hesitancy among the general population.

It is important to note, that positive attitudes toward vaccines decreased among young respondents (under 35s y. o).17,18 Attitudes among young respondent groups who are likely to become parents in the near future are important for the uptake of childhood immunizations.17,18 Bulgaria is one of the countries where the gap in positive attitudes between youngest and oldest groups is large and increasing, with younger groups demonstrating a clearly lower confidence.17 The decline in vaccine confidence among younger populations after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic is documented also in other studies.23 This further underscores the need to collect more in-depth knowledge on attitudes among GPs as well as communication practices among GPs who are a key source of information for current and future parents.

In Bulgaria, most childhood vaccinations are mandatory and administrative vaccination coverage has remained relatively high, with some anecdotal reports of delays in vaccination or falsified vaccination documents. Still, there is a drop in administrative coverage with some mandatory vaccines of 1–2% between 2010 and 2019.24 In this period, there were two measles outbreaks in the country – one in 2009–2012 and one in 2017.25,26 Notably, coverage with diphtheria and tetanus toxoid with pertussis-containing vaccine (DTP3), 3rd dose of polio-containing vaccine (Pol3) and first dose of measles and rubella-containing vaccine (MCV1 and RCV1) fell to 89% by 2021 in the context of the pandemic, creating further risk for vaccine-preventable disease outbreaks.24 In addition, Bulgaria and other countries of similar context in the same geographic region had low COVID-19 vaccination uptake, even though COVID-19 vaccines were available and accessible. As of 16 June 2023, COVID-19 primary course vaccine uptake in Bulgaria is the lowest among countries in the European Union/European Economic Area (EU/EEA), at 30.1% (EU/EEA Cumulative primary course uptake is 75.6%).27 The drop in administrative coverage for mandatory childhood vaccinations before and during the pandemic, as well as the low uptake of the voluntary COVID-19 vaccination, underscore the urgent need to understand vaccine hesitancy in Bulgaria better, in order to provide an evidence base for measures to prevent further outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases and to improve the country’s pandemic preparedness.

The Vaccine Confidence Project, have already looked at VH in the general population of Bulgaria. Bulgarian researchers also outline attitudes among parents, and findings point toward low knowledge of vaccine-preventable diseases and doubts about the safety of vaccines.28 In addition, two recent international studies looked into health and care workers attitudes in Bulgaria in 2020 and 2022, through a sample of 100 health and care workers’ from various professional backgrounds and indicated higher confidence among them than among the general population.17 However, hesitancy among general practitioners has not been studied in detail in Bulgaria.28–30 Hesitancy among GPs is an important element to study, as it can pose central issues with addressing VH among the general population and parents.31–34 If we perceive hesitancy as a barrier to recommending vaccines, understanding factors that predict VH among GPs’ is crucial for tailoring better strategies for improving immunization coverage. General practitioners have a pivotal role in administrating, consulting about mandatory children vaccination and reaching those who are hesitant. They are a trusted source of information about vaccines, and recommendations from GPs are among the most effective strategies to address vaccine hesitancy.35 The aim of the present study was to investigate vaccine hesitancy among Bulgarian general practitioners and to possibly identify factors that serve as predictors of their general vaccine hesitancy.

Materials and methods

Population surveyed and procedure

A cross-sectional face-to-face quantitative survey was conducted among Bulgarian GPs in June-July 2022. The inclusion criteria for participation in the study were that the general practitioner has enrolled children (0–18 y.o.) in his practice. This study excluded those who did not have children in their practice (0–18 y.o.). In short, a random sample of 2002 units was drawn from the exhaustive database of Bulgarian GPs available from the website of the Bulgarian National Health Insurance Fund (BNHIF) (which included 3862 GPs). All units of the random sample of 2002 GPs were contacted in order to: 1/verify the contact details; 2/check the inclusion criteria; and 3/confirm they are willing to participate (as preliminary expectations were that ⅓ of our sample has children in their practice and that the response rate is 50%). A total of 993 GPs (50% of all contacted GPs) could be contacted and had children in their practice, out of whom 875 agreed to participate (88% acceptance rate). Among them, 358 were selected on a random basis to participate in face-to-face interviews. The sample size necessary to estimate a proportion with 95% confidence and a margin of error of 5%, assuming a proportion of 0.5 and a population size equal to the actual finite population number of GPs, as available from the national database (3862 GPs), was 350. Design effect was not incorporated as this was a simple random sample from a complete sampling frame. Eight cases were added to ensure coverage of 350 participants if data was missing and cases needed to be deleted. For the studied 358 participants the confidence interval is 95% and the error level is 4.9%. The survey design and questionnaire were prepared by the study team, while the data collection was carried out by an external contractor (Global Metrix). The interviewers were trained on the questionnaire before the face-to-face interviews. The quality and validity of the data collected by the external contractor were ensured through the participation of a member of the team (Veronika Dimitrova) in checking the conduct of the interviews. The data was checked by the study team for missing data and inconsistencies between variables before proceeding with the statistical analysis.

Questionnaire

The team of the study developed the questionnaire after reviewing relevant literature, conducting qualitative semi-structured interviews with 15 Bulgarian GPs and discussing the questions with a multidisciplinary group of experts in public health and social science. The questionnaire was pilot-tested with 20 GPs before finalization and roll-out. It consisted of two parts, focused on attitudes toward vaccination and communication styles. The first part, which is the focus of this publication, aimed to register attitudes toward vaccines and mandatory childhood vaccination in Bulgaria, levels of trust in institutions and pharmaceutical companies, and core demographic and GP practice variables.

Core demographic and GP practice variables were measured through a set of questions about the profile of the respondent: settlement of the practice (region and type of settlement), age, gender, number of patients enrolled, number of children aged 0–18 in the practice, specialty of the physician, type of the practice (individual or group).

General attitudes toward vaccines were measured through three questions from the four-question core survey developed by Larson et al. for the Vaccine Confidence ProjectTM and used in comparative international studies on vaccine confidence: “vaccines are important for children to have,” “overall I think vaccines are safe,” “overall I think vaccines are effective.”19,21 Attitudes toward the vaccination schedule in Bulgaria were measured through four statements: “it is good that vaccines from the children’s immunization schedule are mandatory,” “Bulgaria’s childhood immunization schedule has my approval,” “all vaccines in the childhood immunization schedule are important,” “most of the diseases, for which there are mandatory vaccines, are dangerous.” Responses for all these statements were rated on a 5-point Likert scale. To probe for behavioral outcomes of GP attitudes, the study team added two questions as follows: (1) “Are there children in your practice who have missed mandatory vaccinations for which they are eligible due to delay or refusal?” with possible answers “Yes” or “No;” and (2) “How often do you recommend vaccines which are not in the mandatory vaccination schedule” with 5-point Likert scale for frequency (ranging from “Always” to “Never”). The second question was posed because in Bulgaria there are vaccines outside of the mandatory vaccination schedule which are still recommended by the Ministry of Health (MoH) for population groups including children.

Levels of trust were measured through the 5-point Likert scale applied to a set of questions, measuring trust in information on vaccines, provided by various institutions, including Bulgarian expert and policy-making institutions (the Bulgarian Ministry of Health (MoH) and other institutions under the regulation of MH (Regional Health Inspectorates, Bulgarian Drug Agency, National Center of Infectious and Parasitic Diseases, and National Center of Public Health and Analyses), international expert bodies (WHO and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC)), pharmaceutical companies, and other general practitioners. In addition, to complement the study with data on primary preferred sources of information, the study team added a question where respondents had to mark their three main preferred sources of information among a list of possible answers.

Additional questions were also added, that could be linked to detected levels of hesitancy including: “have you had, in the last 5 years, experience with diseases for which there are mandatory vaccines” and “have you observed serious vaccine side effects (SAEs), potentially linked to hospitalization and long-term sequelae, in the last 5 years.”36 As well, two questions on parental attitudes were included as follows “Do parents of children in your practice express vaccine hesitancy with regard to the mandatory childhood vaccines?” and “Have you observed changes in parental attitudes after the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic?”

The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for internal consistency reliability for Likert scales and subscales of the questionnaire was calculated to be 0.74.

Statistical methods

A check for representativeness was performed, comparing the distribution by type of settlement of the sample of respondents to the same distribution of the general GP population (as obtained from the database of the BNHIF).

Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to examine if variables are normally distributed, and based on the sample distribution, quantitative variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation (mean ± SD) or median (interquartile (IQ) range 25th percentile; 75th percentile). Categorical variables were presented as absolute numbers and totals (n), as well as percentages (%).

For the purposes of this study, outcome variables were defined аs the seven statements measuring general attitudes toward vaccines and attitudes toward mandatory vaccinations in Bulgaria. The responses to each Likert-scale question were dichotomized into positive and non-positive (including “neither agree nor disagree” or no response). Chi-square test and z-test were used to probe for associations between explanatory and outcome variables, and variables where association was detected (p < .05) or suspected (p < .20) were input into a binomial logistic regression model. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for the fixed effects were calculated. Odds ratios greater than one represent an association between explanatory variables and positive vaccine sentiment and vice versa. The p-values <.05 were considered statistically significant for all statistical tests. The systematization, processing, and analysis of the data were performed using SPSS v.26 for Windows (IBM Corp. Released 2019. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp).

Results

The test for representativeness of the sample showed that the distribution of the sample by type of settlement is almost identical to the distribution of the general GP population by type of settlement. More specifically, 18% of the surveyed GP population works in the capital (Sofia), 41% - in regional capital cities, 27% in small towns and 13% in villages, and the corresponding distribution in the general population of GPs is 19%, 42%, 27% and 13%.

Among the 358 respondents (88% response rate, median age 58 years, 71% female), 78.5% had one specialty, and the rest had two or more specialties. The most common specialty was General Medicine (230, 64.2%), followed by Pediatrics (113, 31.6%). The majority of participants were practicing in a solo practice (318, 88.8%), with a median of 1700 patients (1250–2310 (25th–75th percentile)), and a median of 400 children in the practice (130–650 (25th–75th percentile)) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Personal and professional characteristics of the participants of the study.

| Variable | Results |

|---|---|

| Personal characteristics | |

| Age median (25th percentile; 75th percentile) | 58 y.o (52 y.o; 63 y.o) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 103 (28.8) |

| Female | 255 (71.2) |

| Specialty*, n (%) | |

| General Medicine | 230 (64.2) |

| Pediatrics | 113 (31.6) |

| Internal Medicine | 87 (24.3) |

| Other | 12 (3.4) |

| Number of specialties | |

| One | 281 (78.5) |

| Two or more | 77 (21.5) |

| Location of practice, n (%) | |

| Capital | 66 (18.4) |

| Regional city | 147 (41.1) |

| Small town | 98 (27.4) |

| Village | 47 (13.1) |

| Professional characteristics | |

| Type of practice, n (%) | |

| Solo practice | 318 (88.8) |

| Group practice | 40 (11.2) |

| Number of patients in the practice, n (%) | |

| 1–1000 | 63 (17.6) |

| 1001–2000 | 175 (48.9) |

| 2001–3000 | 88 (24.6) |

| 3001–4000 | 15 (4.2) |

| >4001 | 11 (3.1) |

| No information | 6 (1.7) |

| Number of children in the practice (aged 0–18 y. o.), n (%) | |

| 1–200 | 120 (33.5) |

| 201–400 | 70 (19.6) |

| 401–600 | 65 (18.2) |

| 601–1000 | 68 (19.0) |

| >1001 | 30 (8.4) |

| No information | 5 (1.4) |

| Children in the practice as percent of all patients | |

| 1–10% | 91 (25.4) |

| 11–20 | 84 (23.5) |

| 21–30 | 75 (20.9) |

| 31–40 | 49 (13.7) |

| 41–50 | 29 (8.1) |

| 51–100 | 25 (7.0) |

*Option to list more than one specialty.

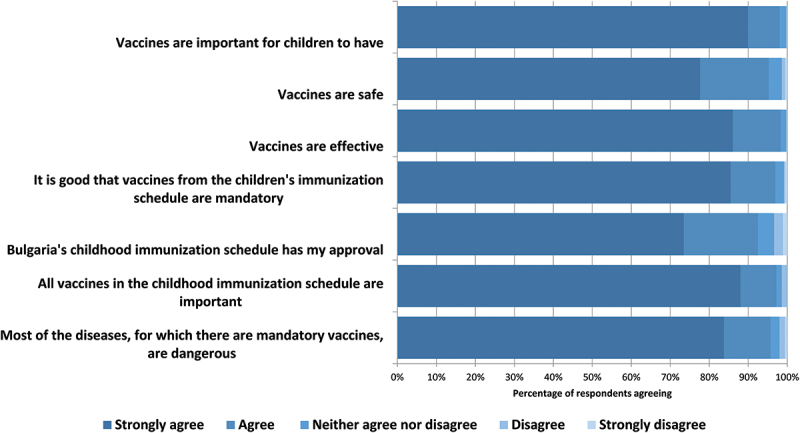

Attitudes toward vaccines are generally positive − 351 (98% 95%CI 96–99%) of the respondents strongly agreed or agreed that vaccines are important for children to have, 352 (98% 95%CI 96–99%) that vaccines are effective, and 341 (95% 95%CI 93–97%) that vaccines are safe. Most of the GPs approve of the vaccination schedule in Bulgaria − 347 (97% 95%CI 95–98%) affirm that “it’s good that vaccines from the children’s immunization schedule are mandatory” and 348 (97%, 95%CI 95–98%) that “all vaccines in the childhood immunization schedule are important,” with a slightly lower percentage 92% (331 respondents, 95%CI 89–95%) strongly agreeing or agreeing with the statement “Bulgaria’s childhood immunization has my approval.” 343 (96%, 95%CI 93–97%) of the GPs support the statement “Most of the diseases for which there are mandatory vaccines are dangerous” (Figure 1). In terms of the two questions aiming to probe for behavioral outcomes, 144 (40%, 95%CI 35–45%) of doctors shared that they have children in their practice who have missed vaccinations. In addition, while a predominant proportion of doctors express positive general attitudes toward vaccines and the mandatory vaccination schedule, a smaller percentage, 75% (268, 95%CI 70–79%) state that they always or often recommend vaccines that are not in the mandatory vaccination schedule.

Figure 1.

Distribution of responses to key questions measuring general attitudes toward vaccines and attitudes toward the vaccination schedule among Bulgarian GPs in 2022.

240 (67%) of the physicians say that the parents in their practice have expressed hesitations regarding mandatory vaccines and 154 (43%) observe that there is a change in parental attitudes after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Among GPs, 32 (9.0%) shared that they have had experience with a vaccine-preventable disease in their practice in the last five years, and 20 (5.6%) state that they have had a patient with a severe adverse event following vaccination, potentially related to hospitalization or need for treatment in the last 5 years. The 20 GPs that have observed a severe adverse event had a total of 13 236 children registered in their practices as of 2022, and having observed a severe adverse event following vaccination in the last five years, taking into account a total denominator of over 172 415 children (total number of respondents pediatric patients), is not unexpected with the known vaccine safety profile.

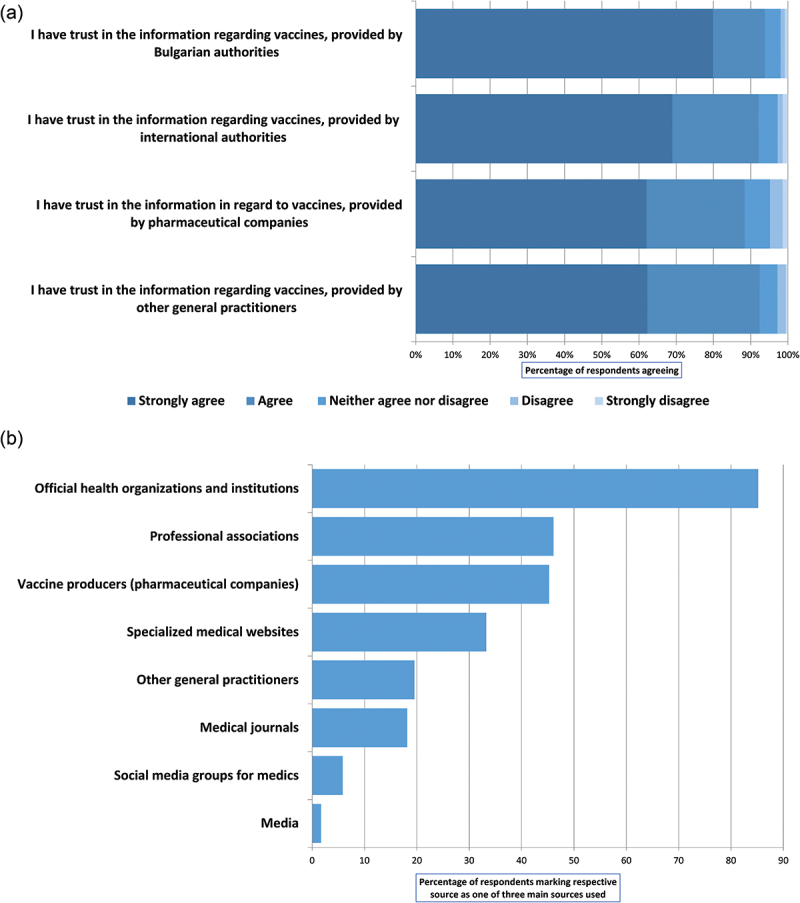

With regards to levels of trust in various information sources, 94% (336) and 92% (330) of respondents express trust in the information regarding vaccines, provided by national public health authorities and international expert organizations, and 88% (315) trust the information regarding vaccines, provided by pharmaceutical companies. 93% (331) trust the information provided by other general practitioners (Figure 2(a)). The most preferred sources of information were: official health organizations and institutions (among the three top sources for 85% (305) of respondents); professional associations (the Bulgarian Medical Association, the National Association of General Practitioners) (46%, 165), and vaccine producers (pharmaceutical companies) (45%, 162) (Figure 2(b)).

Figure 2.

(a) Distribution of responses to questions measuring trust in various sources of information on vaccines among Bulgarian GPs. (b) Preferred sources of information on vaccines (respondents were asked to mark their three main preferred sources from a multiple-choice list).

Relationships with vaccine confidence index items

The study demonstrates a consistent association between four explanatory variables (trust in information provided by national, international authorities and pharmaceutical companies and recommendation of non-mandatory vaccinations), and all key outcome variables measuring general attitudes toward vaccination. There was an association between the trust of the respondents in the information received from official sources (WHO, ECDC, MoH) and pharmaceutical companies, and their positive attitude toward vaccines in terms of importance, safety and effectiveness (p < .001) (Table 2). The greater the trust is, the less hesitant are the GPs. Trust in the information provided by other GPs is not related to the statement about the importance of the vaccine, but is linked with the statements about the safety and effectiveness of vaccines – the greater the trust, the greater the confidence about the effectiveness and safety of vaccines (p < .001). In addition, respondents who never recommend non-mandatory vaccines are more inclined to have doubts about the importance, safety and effectiveness of vaccines (p < .001).

Table 2.

Univariate analysis of the potential predictors on GPs’ behavior.

| Importance |

p–value | Safety |

p–value | Effectiveness |

p–value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agree | Disagree | Agree | Disagree | Agree | Disagree | ||||

| Gender, n (%) | |||||||||

| Male | 101 (98.0) | 2 (2.0) | .991 | 97 (94.2) | 6 (5.8) | .543 | 100 (97.1) | 3 (2.9) | .247 |

| Female | 250 (98.0) | 5 (2.0) | 244 (95.7) | 11 (4.3) | 252 (98.8) | 3 (1.2) | |||

| Age groups, n (%) | |||||||||

| 31–40 y | 11 (100) | 0 (0) | .920 | 11 (100) | 0 (0) | .817 | 11 (100) | 0 (0) | .317 |

| 41–50 y | 54 (98.2) | 1 (1.8) | 52 (94.5) | 3 (5.5) | 55 (100) | 0 (0) | |||

| 51–60 y | 160 (97.5) | 4 (2.5) | 155 (94.5) | 9 (5.5) | 159 (97.0) | 5 (3.0) | |||

| >61 y | 122 (98.4) | 2 (1.6) | 119 (96.0) | 5 (4.0) | 123 (99.2) | 1 (0.8) | |||

| Number of patients in the practice, n (%) | |||||||||

| 1–1000 | 61 (96.8) | 2 (3.2) | .846 | 60 (95.2) | 3 (4.8) | .934 | 60 (95.2) | 3 (4.8) | .242 |

| 1001–2000 | 171 (97.7) | 4 (2.3) | 167 (95.4) | 8 (4.6) | 174 (99.4) | 1 (0.6) | |||

| 2001–3000 | 87 (98.9) | 1 (1.1) | 83 (94.3) | 5 (5.7) | 86 (97.7) | 2 (2.3) | |||

| 3001–4000 | 15 (100) | 0 (0) | 14 (93.3) | 1 (6.7) | 15 (100) | 0 (0) | |||

| >4001 | 11 (100) | 0 (0) | 11 (100) | 0 (0) | 11 (100) | 0 (0) | |||

| Number of children in the practice, n (%) | |||||||||

| 1–200 | 115 (95.8) | 5 (4.2) | .240 | 111 (92.5) | 9 (7.5) | .335 | 116 (96.7) | 4 (3.3) | .442 |

| 201–400 | 70 (100) | 0 (0) | 70 (100) | 0 (0) | 70 (100) | 0 (0) | |||

| 401–600 | 63 (96.9) | 2 (3.1) | 62 (95.4) | 3 (4.6) | 64 (98.5) | 1 (1.5) | |||

| 601–800 | 42 (100) | 0 (0) | 40 (95.2) | 2 (4.8) | 42 (100) | 0 (0) | |||

| 801–1000 | 26 (100) | 0 (0) | 25 (96.1) | 1 (3.9) | 26 (100) | 0 (0) | |||

| >1001 | 30 (100) | 0 (0) | 28 (93.3) | 2 (6.7) | 29 (96.7) | 1 (3.3) | |||

| Percentage of children in the practice, n (%) | |||||||||

| 1–10% | 86 (94.5) | 5 (5.5) | .141 | 83 (91.2) | 8 (8.8) | .083 | 88 (96.7) | 3 (3.3) | .409 |

| 11–20% | 83 (98.8) | 1 (1.2) | 81 (96.4) | 3 (3.6) | 82 (97.6) | 2 (2.4) | |||

| 21–30% | 74 (98.7) | 1 (1.3) | 74 (98.7) | 1 (1.3) | 75 (100) | 0 (0) | |||

| 31–40% | 49 (100) | 0 (0) | 47 (95.9) | 2 (4.1) | 49 (100) | 0 (0) | |||

| 41–50% | 29 (100) | 0 (0) | 29 (100) | 0 (0) | 29 (100) | 0 (0) | |||

| 51–100% | 25 (100) | 0 (0) | 22 (88) | 3 (12) | 24 (96) | 1 (4) | |||

| Settlement of the practice, n (%) | |||||||||

| Capital city | 64 (97) | 2 (3) | .400 | 60 (90.9) | 6 (9.1) | .114 | 64 (97) | 2 (3) | .287 |

| Regional city | 146 (99.3) | 1 (0.7) | 139 (94.5) | 1 (5.5) | 146 (99.3) | 1 (0.7) | |||

| Small town | 96 (97.9) | 2 (2.1) | 97 (98.9) | 2 (1.1) | 97 (98.9) | 2 (1.1) | |||

| Village | 45 (95.7) | 2 (4.3) | 45 (95.7) | 2 (4.3) | 45 (95.7) | 2 (4.3) | |||

| Number of specialties, n (%) | |||||||||

| One | 275 (97.9) | 6 (2.1) | .885 | 267 (95) | 14 (5) | .899 | 275 (97.9) | 6 (2.1) | .427 |

| Two or more | 76 (98.7) | 1 (1.3) | 74 (96.1) | 3 (3.9) | 77 (100) | 0 (0) | |||

| Type of practice, n (%) | |||||||||

| Solo practice | 312 (98.1) | 6 (1.9) | .792 | 303 (95.3) | 15 (4.7) | .937 | 313 (98.4) | 5 (1.6) | .667 |

| Group practice | 39 (97.5) | 1 (2.5) | 38 (95) | 2 (5) | 39 (97.5) | 1 (2.5) | |||

| Have you had cases of VPD due to delay or refusal?, n (%) | |||||||||

| Yes | 31 (96.9) | 1 (3.1) | .617 | 31 (96.9) | 1 (3.1) | .651 | 31 (96.9) | 1 (3.1) | .310 |

| No | 320 (98.1) | 6 (1.9) | 310 (95.1) | 16 (4.9) | 310 (95.1) | 16 (4.9) | |||

| How often do you recommend non–mandatory vaccine?, n (%) | |||||||||

| Always | 104 (98.1) | 2 (1.9) | .000 * | 104 (98.1) | 2 (1.9) | .000 | 105 (99.1) | 1 (0.9) | .000 * |

| Often | 161 (99.4) | 1 (0.6) | 158 (97.5) | 4 (2.5) | 161 (99.4) | 1 (0.6) | |||

| Rarely | 67 (100) | 0 (0) | 62 (92.5) | 5 (7.5) | 66 (98.5) | 1 (1.5) | |||

| Never | 19 (82.6) | 4 (13.4) | 17 (73.9) | 6 (26.1) | 20 (86.9) | 3 (13.1) | |||

| Have you observed SAEs possibly related to hospitalization? | |||||||||

| Yes | 320 (98.1) | 6 (1.9) | .313 | 310 (95.1) | 16 (4.9) | .258 | 321 (98.5) | 5 (1.5) | .235 |

| No | 31 (96.9) | 1 (3.1) | 31 (96.9) | 1 (3.1) | 31 (96.9) | 1 (3.1) | |||

| Are there more hesitant parents after COVID–19?, n (%) | |||||||||

| Yes | 234 (97.5) | 6 (2.5) | .288 | 226 (94.2) | 14 (5.8) | .169 | 235 (97.9) | 5 (2.1) | .392 |

| No | 117 (99.1) | 1 (0.9) | 115 (97.4) | 3 (2.6) | 117 (99.1) | 1 (0.9) | |||

| Is there a change in parent’s attitudes towards vaccines?, n (%) | |||||||||

| Yes | 150 (97.4) | 4 (2.6) | .446 | 140 (90.9) | 14 (9.1) | .001 | 149 (96.7) | 5 (3.3) | .044 * |

| No | 201 (98.5) | 3 (1.5) | 201 (98.5) | 3 (1.5) | 203 (99.5) | 1 (0.5) | |||

| I have trust in the information on vaccines from official authorities (WHO, ECDC) | |||||||||

| Yes | 326 (92.9) | 25 (7.1) | .000 | 318 (93.3) | 23 (6.7) | .001 | 329 (93.5) | 23 (6.5) | .000 |

| No | 4 (57.1) | 3 (42.9) | 12 (70.6) | 5 (17.9) | 1 (16.7) | 5 (83.3) | |||

| I have trust in the information on vaccines from Bulgarian official authorities (MoH and others, n (%) | |||||||||

| Yes | 332 (98.8) | 4 (1.2) | .000 | 324 (96.4) | 12 (3.6) | .000 | 334 (99.4) | 2 (0.6) | .000 |

| No | 19 (86.4) | 3 (13.6) | 17 (77.3) | 5 (22.7) | 18 (81.8) | 4 (18.2) | |||

| I have trust in the information on vaccines from pharmaceutical companies | |||||||||

| Yes | 309 (99) | 3 (1.0) | .000 | 302 (96.8) | 10 (3.2) | .000 | 311 (99.7) | 1 (0.3) | .000 |

| No | 42 (91.3) | 4 (8.7) | 39 (84.8) | 7 (15.2) | 41 (89.1) | 5 (10.9) | |||

| I have trust in the information on vaccines from other GPs, n (%) | |||||||||

| Yes | 325 (98.2) | 6 (1.8) | .495 | 318 (96.1) | 13 (3.9) | .011 | 328 (99.1) | 3 (0.9) | .000 |

| No | 26 (96.3) | 1 (3.7) | 23 (85.2) | 4 (14.8) | 24 (88.9) | 3 (11.1) | |||

| Are there children in your practice which have missed mandatory vaccinations for which they are eligible due to delay or refusal? | |||||||||

| Yes | 209 (97.7) | 5 (2.3) | .525 | 205 (95.8) | 9 (4.2) | .556 | 211 (98.6) | 3 (1.4) | .622 |

| No | 142 (98.6) | 2 (1.4) | 136 (94.4) | 8 (5.6) | 141 (97.9) | 3 (2.1) | |||

| It’s good the vaccines are mandatory |

p–value | All vaccines from the schedule are important |

p–value | I generally approve the Bulgarian immunization calendar |

p–value | Generally, the diseases for which there are mandatory vaccines are dangerous |

p–value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agree | Disagree | Agree | Disagree | Agree | Disagree | Agree | Disagree | |||||

| Gender, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| Male | 99 (96.1) | 4(3.9) | .572 | 98 (95.1) | 5 (4.9) | .133 | 89 (86.4) | 14 (13.6) | .006 | 99 (96.1) | 4 (3.9) | .854 |

| Female | 248 (97.2) | 7 (2.8) | 250 (98.0) | 5 (2.0) | 242(94.9) | 13 (5.1) | 244 (95.7) | 11 (4.3) | ||||

| Age groups, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| 31–40 y. | 11 (100) | 0 (0) | .560 | 10 (90.9) | 1 (9.1) | .266 | 10 (90.9) | 1 (9.1) | .319 | 10 (90.9) | 1 (9.1) | .041 |

| 41–50 y. | 53 (96.4) | 2 (3.6) | 53 (96.4) | 2 (3.6) | 52 (94.5) | 3 (5.5) | 49 (89.1) | 6 (10.9) | ||||

| 51–60 y. | 157 (95.7) | 7 (4.3) | 158 (96.3) | 6 (2.7) | 147 (89.6) | 17 (10.4) | 159 (96.9) | 5 (3.1) | ||||

| >61 y. | 122 (98.4) | 2 (1.6) | 123 (99.2) | 1 (0.8) | 118 (95.2) | 6 (4.8) | 121 (97.6) | 3 (2.4) | ||||

| Number of patients in the practice, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| 1–1000 | 60 (95.2) | 3 (4.8) | .833 | 60 (95.2) | 3 (4.8) | .790 | 58 (92.1) | 5 (7.9) | .120 | 58 (92.1) | 5 (7.9) | .121 |

| 1001–2000 | 170 (97.1) | 5 (2.9) | 170 (97.1) | 5 (2.9) | 162 (92.6) | 13 (7.4) | 171 (97.7) | 4 (2.3) | ||||

| 2001–3000 | 85 (96.6) | 3 (3.4) | 86 (97.7) | 2 (2.3) | 82 (93.2) | 6 (6.8) | 84 (95.4) | 4 (4.6) | ||||

| 3001–4000 | 15 (100) | 0 (0) | 15 (100) | 0 (0) | 15 (100) | 0 (0) | 13 (86.7) | 2 (13.3) | ||||

| >4001 | 11 (100) | 0 (0) | 11 (100) | 0 (0) | 8 (72.7) | 3 (27.3) | 11 (100) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Number of children in the practice, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| 1–200 | 114(95) | 6 (5.0) | .702 | 112 (93.3) | 8 (6.7) | .321 | 107 (89.2) | 13 (10.8) | .104 | 113 (94.2) | 7 (5.8) | .038* |

| 201–400 | 69 (98.6) | 1 (1.4) | 70 (100) | 0 (0) | 66 (94.3) | 4 (5.7) | 70 (100) | 0 (0) | ||||

| 401–600 | 63 (96.9) | 2 (3.1) | 64 (98.5) | 1 (1.5) | 63 (96.9) | 2 (3.1) | 63 (96.9) | 2 (3.1) | ||||

| 601–800 | 41 (97.6) | 1 (2.4) | 42 (100) | 0 (0) | 41 (97.6) | 1 (2.4) | 42 (100) | 0 (0) | ||||

| 801–1000 | 26 (100) | 0 (0) | 26 (100) | 0 (0) | 24 (92.3) | 2 (7.7) | 23 (88.5) | 3 (11.5) | ||||

| >1001 | 29 (96.7) | 1 (3.3) | 29 (96.7) | 1 (3.3) | 25 (83.3) | 5 (16.7) | 27 (90) | 3 (10) | ||||

| Percentage of children in the practice, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| 1–10% | 86 (94.5) | 5 (5.5) | .686 | 85 (93.4) | 6 (6.6) | .093 | 82 (90.1) | 9 (9.9) | .210 | 86 (94.5) | 5 (5.5) | .224 |

| 11–20% | 82 (97.6) | 2 (2.4) | 81 (96.4) | 3 (3.6) | 76 (90.5) | 8 (9.5) | 80 (95.2) | 4 (4.8) | ||||

| 21–30% | 73 (97.3) | 2 (2.7) | 75 (100) | 0 (0) | 72 (96) | 3 (4) | 74 (98.7) | 1 (1.3) | ||||

| 31–40% | 48 (97.9) | 1 (2.1) | 49 (97.9) | 0 (0) | 48 (97.9) | 1 (2.1) | 47 (95.9) | 2 (4.1) | ||||

| 41–50% | 29 (100) | 0 (0) | 29 (100) | 0 (0) | 27 (93.1) | 2 (6.9) | 29 (100) | 0 (0) | ||||

| 51–100% | 24 (96) | 1 (4) | 24 (96) | 1 (4) | 21 (84) | 4 (16) | 22 (88) | 3 (12) | ||||

| Settlement of the practice, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| Capital city | 62 (94) | 4 (6) | .147 | 63 (95.4) | 3 (4.6) | .764 | 63 (95.4) | 3 (4.6) | .574 | 61 (92.4) | 5 (7.6) | .144 |

| Regional city | 146 (99.3) | 1 (0.7) | 144 (97.9) | 3 (2.1) | 137 (93.2) | 3 (6.8) | 139 (99.3) | 3 (0.7) | ||||

| Small town | 94 (95.9) | 4 (4.1) | 95 (96.9) | 3 (3.1) | 89 (90.8) | 3 (9.2) | 97 (99) | 3 (1) | ||||

| Village | 45 (95.7) | 2 (4.3) | 46 (97.9) | 1 (2.1) | 42 (89.4) | 1 (10.6) | 46 (97.9) | 1 (2.1) | ||||

| Number of specialties, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| One | 272 (97.9) | 9 (2.1) | .947 | 272 (97.9) | 9 (2.1) | .655 | 257 (91.4) | 24 (8.6) | .373 | 268 (95.4) | 13 (4.6) | .864 |

| Two or more | 75 (97.4) | 2 (2.6) | 76 (98.7) | 1 (1.3) | 74 (96.1) | 3 (3.9) | 75 (97.4) | 3 (2.6) | ||||

| Type of practice, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| Solo practice | 308 (96.8) | 10 (3.2) | .824 | 309 (97.2) | 9 (2.8) | .905 | 295 (92.8) | 23 (7.2) | .532 | 304 (95.6) | 14 (4.4) | .571 |

| Group practice | 39 (97.5) | 1 (2.5) | 39 (97.5) | 1 (2.5) | 36 (90) | 4 (10) | 39 (97.5) | 1 (2.5) | ||||

| Have you had cases of VPD due to delay or refusal?, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 30 (93.7) | 2 (6.3) | .275 | 32 (100) | 0 (0) | .315 | 29 (90.6) | 3 (9.4) | .681 | 32 (100) | 0 (0) | .215 |

| No | 317 (97.2) | 9 (2.8) | 316 (96.9) | 10 (3.1) | 302 (92.6) | 24 (7.4) | 311 (95.4) | 15 (4.6) | ||||

| How often do you recommend non–mandatory vaccine?, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| Always | 105 (99.0) | 1 (1.0) | .000* | 104 (98.1) | 2 (1.9) | .000* | 102 (96.2) | 4 (3.8) | .000 | 102 (96.2) | 4 (3.8) | .036* |

| Often | 159 (98.1) | 3 (1.9) | 161 (99.4) | 1 (0.6) | 155 (95.7) | 7 (4.3) | 159 (98.1) | 3 (1.9) | ||||

| Rarely | 65 (97.0) | 2 (3.0) | 64 (95.5) | 3 (4.5) | 58 (85.6) | 9 (14.4) | 62 (92.5) | 5 (7.5) | ||||

| Never | 18 (78.3) | 5 (21.7) | 19 (82.6) | 4 (17.4) | 16 (69.6) | 7 (30.4) | 20 (86.9) | 3 (13.1) | ||||

| Have you observed SAEs possibly related to hospitalization?, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 317 (97.2) | 9 (2.8) | .275 | 316 (96.9) | 10 (3.1) | .315 | 302 (92.6) | 24 (7.4) | .681 | 311 (95.4) | 15 (4.6) | .215 |

| No | 30 (93.7) | 2 (6.3) | 32 (100) | 0 (0) | 29 (90.6) | 3 (9.4) | 32 (100) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Are there more hesitant parents after COVID–19?, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 230 (95.8) | 10 (4.2) | .087 | 232 (96.7) | 8 (3.3) | .377 | 219 (91.2) | 21 (8.8) | .217 | 230 (95.8) | 10 (4.2) | .975 |

| No | 117 (99.1) | 1 (0.9) | 116 (98.3) | 2 (1.7) | 112 (94.9) | 6 (5.1) | 113 (95.8) | 5 (4.2) | ||||

| Is there a change in parent’s attitudes towards vaccines?, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 146 (94.8) | 8 (5.2) | .043 | 148 (96.1) | 6 (3.9) | .271 | 141 (91.5) | 13 (8.5) | .575 | 149 (96.7) | 5 (3.3) | .439 |

| No | 201 (98.5) | 3 (1.5) | 200 (98.0) | 4 (2.0) | 190 (93.1) | 14 (6.9) | 194 (95.1) | 10 (4.9) | ||||

| I have trust in the information on vaccines from official authorities (WHO, ECDC) | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 325 (93.7) | 22 (6.3) | .000 | 326 (93.7) | 22 (6.3) | .000 | 309 (93.4) | 22 (6.6) | .004 | 317 (92.4) | 26 (7.6) | .417 |

| No | 5 (45.5) | 6 (54.5) | 4 (40) | 6 (60) | 21 (77.8) | 6 (22.2) | 13 (86.7) | 2 (13.3) | ||||

| I have trust in the information on vaccines from Bulgarian official authorities (MoH and others),n (%) | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 331 (98.5) | 5 (1.5) | .000 | 330 (98.2) | 6 (1.8) | .000 | 314 (93.4) | 22 (6.6) | .005 | 322 (95.8) | 14 (4.2) | .932 |

| No | 16 (72.7) | 6 (27.3) | 18 (81.8) | 4 (18.2) | 17 (77.3) | 5 (22.7) | 21 (95.4) | 1 (4.6) | ||||

| I have trust in the information on vaccines from pharmaceutical companies, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 308 (98.7) | 4 (1.3) | .000 | 309 (99.0) | 3 (1.0) | .000 | 294 (94.2) | 18 (5.8) | .001 | 299 (95.8) | 13 (4.2) | .954 |

| No | 39 (84.8) | 7 (15.2) | 39 (84.8) | 7 (15.2) | 37 (80.4) | 9 (19.6) | 44 (95.6) | 2 (4.4) | ||||

| I have trust in the information on vaccines from other GPs, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 324 (97.9) | 7 (2.1) | .000 | 325 (98.2) | 6 (1.8) | .000 | 307 (92.7) | 24 (7.3) | .465 | 318 (96.1) | 13 (3.9) | .386 |

| No | 23 (85.2) | 4 (14.8) | 23 (85.2) | 4 (14.8) | 24 (88.9) | 3 (11.1) | 25 (92.6) | 2 (7.4) | ||||

| Are there children in your practice which have missed mandatory vaccinations for which they are eligible due to delay or refusal? | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 210 (98.1) | 4 (1.9) | .108 | 209 (97.7) | 5 (2.3) | .523 | 197 (92.0) | 17 (8.0) | .725 | 203 (94.8) | 11 (5.2) | .274 |

| No | 137 (95.1) | 7 (4.9) | 139 (96.5) | 5 (3.5) | 134 (93.0) | 10 (7.0) | 140 (97.2) | 4 (2.8) | ||||

*More than 25 % of cells have expected couts less than 5

There was an association between the perceived safety of vaccines and the question of whether there is a change in parent’s attitudes toward vaccines after the emergence of COVID-19 (p = .001). Those who consider that there is no change, have fewer doubts about vaccine safety. This possibly means that those who are more confident in vaccines safety are less sensitive about parental hesitancy.

For all other variables, no relationships were identified.

Relationships with variables measuring attitudes toward Bulgarian immunization schedule

There was an association between the trust of the respondents in the information received from official sources (WHO, ECDC, MoH) and pharmaceutical companies, and positive responses on the statements “it’s good that vaccines are mandatory,” “all vaccines from the schedule are important” and “I generally approve the Bulgarian immunization calendar (p < .01).

Trust in the information provided by other GPs was associated with positive responses only on the statements “it’s good that vaccines are mandatory” and “all vaccines from the schedule are important” (p < .001).

In addition, the more often respondents tend to recommend non-mandatory vaccinations, the more inclined they are to agree with the statement “I generally approve of the Bulgarian immunization calendar” (p < .001).

No association was established between most explanatory variables and responses to the statement “generally, diseases for which there are mandatory vaccines are dangerous.” An exception is the association between the age of the respondent and responses to this statement. Respondents in the age group 41–50 were less likely to agree with the statement (p < .05)

In general, although approval of the mandatory vaccination schedule in Bulgaria is high, female respondents are more likely to accept the immunization schedule (p < .01).

There is a relationship between the observed change in parental attitudes toward vaccines after the emergence of COVID-19 and the statement “it’s good the vaccines are mandatory” - GPs who think there was no change in parental attitudes are more inclined to approve of the mandatory approach to vaccinations.

For all other variables, no relationships were identified.

Regression analysis

Table 3 illustrates the findings of the binominal logistic models used to study the relationship between the respondents’ characteristics, working environment, behavioral variables, and attitudes regarding vaccinations. GPs in regional practices were more likely than their colleagues in small communities to agree that vaccines, included in the immunization schedule, are important (OR = 55.37, 95% CI 3.90–786.07). Males were less likely than females to endorse the immunization schedule (OR = 0.42, 95% CI 0.18–0.99). GPs who never advise non-mandatory vaccinations are less likely to agree that vaccines are safe and effective, and less likely to agree with the mandatory approach to vaccination (Table 3). GPs that frequently advocated non-mandatory vaccinations were more inclined to approve the vaccination schedule and to appreciate the severity of diseases included in the schedule (OR = 8.11, 95% CI 2.30–28.60; OR = 6.88, 95% CI 1.05–45.12). Doctors who consider the parents in their practice did not change their attitudes toward vaccines following the COVID-19 outbreak were more likely to believe vaccines are safe (OR = 5.56 and 95% CI 1.24–25.05). Physicians who did not trust in information provided by pharmaceutical companies on vaccines were less likely to affirm that vaccines are safe (OR = 0.20, 95% CI 0.04–0.95) and effective (OR = 0.07, 95% CI 0.01–0.88), to recognize the importance of vaccines included in the immunization schedule (OR = 0.07, 95% CI 0.01–.41), or to approve the overall vaccination schedule in Bulgaria (OR = 0.30, 95% CI 0.09–0.96).

Table 3.

Binominal logistic regression results – Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI), predictive power and quality of the model (R2).

| Importance R2 = 22.4% |

Safety R2 = 33.0% |

Effectiveness R2 = 52.4% |

Mandatoriness R2 = 48.0% |

Vaccine Calendar (VC) Importance R2 = 44.7% |

Vaccine Schedule approval R2 = 21.2% |

Severity of diseases included in VC R2 = 17.7% |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||||

| Female (baseline) | N/A** | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||

| Male | 0.69 (0.13–3.79) | 0.42 (0.18–0.99)* | |||||

| Age groups | |||||||

| 31–40 y. | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.25 (0.02–3.10) |

| 41–50 y. | 0.25 (0.06–1.17) | ||||||

| 51–60 y. | 0.65 (0.15–2.89) | ||||||

| >61 y. (baseline) | |||||||

| Number of children in the practice | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | 0.99 (0.99–1.00) | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) |

| Settlement of the practice | |||||||

| Village (baseline) | |||||||

| Capital city | N/A | 0.36 (0.05–2.82) | N/A | 0.63 (0.05–7.31) | 6.57 (0.79–54.70) | N/A | 0.45 (0.05–4.48) |

| Regional city | 0.32 (0.04–2.71) | 9.44 (0.18–493.15) | 55.37 (3.90–786.07)* | 0.40 (0.04–3.61) | |||

| Small town | 1.82 (0.11–29.93) | 0.32 (0.03–3.94) | 8.66 (0.962–77.98) | 1.8 (0.10–31.33) | |||

| Have you had cases of VPD? | |||||||

| Yes (baseline) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| No | 1.54 (0.14–16.74) | ||||||

| How often do you recommend non–mandatory vaccine? | |||||||

| Never (baseline) | N/A | N/A | |||||

| Rarely | 5.75 (1.09–30.19)* | 37.52 (0.87–1615.06)* | 14.88 (1.11–199.85)* | 2.14 (0.62–7.37) | 2.14 (0.38–11.99) | ||

| Often | 14.61 (2.74–77.86)* | 45.82 (1.87–1122.34)* | 27.28 (3.32–224.25)* | 8.11 (2.30–28.60)* | 6.88 (1.05–45.12)* | ||

| Always | 12.61 (1.80–88.46)* | 7.57 (0.47–123.28) | 41.31 (2.84–601.73)* | 9.34 (2.25–38.81)* | 3.20 (0.56–18.38) | ||

| Are there more hesitant parents after COVID–19? | |||||||

| Yes (baseline) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| No | 4.31 (0.35–53.16) | ||||||

| Is there a change in parent’s attitudes towards vaccines? | |||||||

| Yes (baseline) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |||

| No | 5.56 (1.24–25.05)* | 4.06 (0.26–64.56) | 1.16 (0.18–7.59) | ||||

| I have trust in the information on vaccines from official authorities | |||||||

| Yes (baseline) | N/A | ||||||

| No | 0.25 (0.03–2.210) | 0.99 (0.11–8.66) | 0.53 (0.03–8.16) | 0.19 (0.02–1.92) | 1.20 (0.15–9.69) | 0.74 (0.16–3.32) | |

| I have trust in the information on vaccines from pharmaceutical companies | N/A | ||||||

| Yes (baseline) | |||||||

| No | 0.23 (0.03–1.81) | 0.20 (0.04–0.95)* | 0.07 (0.01–0.88)* | 0.26 (0.03–2.38) | 0.07 (0.01–.41)* | 0.30 (0.09–0.96)* | |

| I have trust in the information on vaccines from other GPs | |||||||

| No (baseline) | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||||

| Yes | 0.35 (0.05–2.41) | 0.08 (0.01–1.74) | 0.39 (0.05–3.21) | 0.12 (0.02–0.80)* |

*p–value < .05.

**Variable did not meet the model assumptions for inclusion.

Discussion

This study is the first to investigate the attitudes toward immunization of a relatively large, representative sample of Bulgarian general practitioners. Vaccine confidence among Bulgarian general practitioners is high, both in terms of general attitudes toward vaccines and in terms of approval of the specific immunization schedule in Bulgaria. Confidence in official information sources on vaccines is also relatively high among Bulgarian GPs.

In our study, 95% of respondents strongly agreed or agreed that vaccines are safe, and 98% that vaccines are effective and important. Respondents’ agreement with these statements from the vaccine confidence project (namely “vaccines are safe”, “vaccines are effective” and “vaccines are important for children to have”) are similar to those reported by a small sample of nurses and physicians in Bulgaria, among whom 96% agreed that vaccines are safe and effective, and 99% agreed that vaccines are important, with attitudes remaining stable between 2018 and 2022.17 Respondents agreement with these statements are also within ranges reported in 2018 among GPs from 10 other European countries where between 94 and 100% of GPs strongly agree or agree that vaccines are safe, between 94 and 100%, that vaccines are effective, and between 93 and 100% – that vaccines are important for children to have. GPs confidence in vaccines, as measured through these key questions, is above the vaccine confidence of the Bulgarian general population, summarized in a study from 2022, where 61% of respondents agreed that vaccines are safe, 68%, that vaccines are effective, and 65% that vaccines are important. Overall our study demonstrates similar attitudes between Bulgarian GPs and GPs elsewhere in Europe, and higher confidence among Bulgarian GPs in comparison to the general population in the country.

Overall GP trust in information on vaccines provided by official authorities is also high in Bulgaria, compared to GP’s trust in official authorities from other contexts such as France.9 While there are no studies on trust among the Bulgarian general population regarding vaccine information from official sources, the current study demonstrates that GPs trust in official authorities is higher than the trust in authorities of parents measured in other contexts.8–10,36–38 This discrepancy can be interpreted through the official position of general practitioners – GPs are representatives of the medical authorities and at the same time they are the main persons in charge of the administration of mandatory vaccines. Trust is an important element of the very fabric of these institutions, fostering cooperation and collaboration between individual institutional actors.

Thus, expectedly, trust in information provided by official authorities and pharmaceutical companies also came up in our study as one of the strongest predictors of vaccine confidence, as measured through GPs opinion about the importance, safety and efficacy of vaccines. These findings are consistent with results from other countries where distrust toward official institutions contributes to VH.9,39,40

The propensity to recommend non-mandatory vaccines is also a predictor of vaccine confidence, both in our study and in other studies.15 The answer to the question if GPs recommend non-mandatory vaccines in the context of low vaccine hesitancy among GPs could be interpreted as an administrative burden, reluctance to communicate and vaccinate hesitant patients. That is why it should be considered the organizational and communicational aspects related to recommendations and parental VH are possibly more important for addressing VH in Bulgaria.

Approval of the mandatory character, schedule, importance of vaccines and affirmation of the statement that diseases, prevented through the Bulgarian immunization plan, are dangerous, are also high. Similarly, to general vaccine confidence, confidence in the specific immunization schedule of the country is linked to trust in pharmaceutical companies and the propensity to recommend non-mandatory vaccines. At the same time, trust in official sources of information did not come up as a reliable predictor of approval of the immunization schedule. Some other factors did affect the approval of the immunization schedule. For example, practicing in a regional city and trusting the information provided by other GPs came up as positive predictors of agreeing with the importance of the Bulgarian immunization schedule. Approval of the schedule is also linked to female gender. Assessment of the severity of diseases for which there are mandatory vaccines used is associated with the frequency of recommendations. These results can’t be compared with existing research for other countries, because of the differences in measurement and variation in mandatory schedules. This study found that personal and professional characteristics are linked to the attitudes toward the calendar, except for gender and type of settlement.

Of note, certain factors associated with vaccine confidence in other studies did not come up as predictors in ours. While other studies have shown various personal and practice characteristics associated with VH among GPs, this study did not observe such links.9,10,41,42 Other types of predictors in the existing publications are experience with vaccine-preventable diseases and serious adverse events following vaccination – GPs having treated such diseases in their practice are less hesitant, and those who observed serious adverse events are more hesitant.9 Although this study included such questions it could not confirm an association between these predictors on hesitancy.

Vaccine confidence, approval of the immunization schedule in Bulgaria, and trust in official sources of information on vaccines are high among GPs in the country. At the same time, vaccine confidence among the general population in the country is low when compared to other countries, both globally and in Europe. Possibly the place in the global map of VH of Bulgaria and the country’s lowering vaccine uptake may be linked to reasons, different from GPs attitudes toward mandatory vaccines. These reasons may be as organizational and communication aspects of the work of GPs, and the effect of the shifting media environment. Taking into account the findings of this study, it is important to continue the ongoing institutional work in maintaining the high trust in official authorities among GPs, which is a central predictor of vaccine confidence. It is important to also improve the institutional support for GPs in their central role of communication with patients. GPs’ confidence in vaccines is high in Bulgaria therefore GPs are a possible channel for communication and vaccine-supporting messages in the country. This underscores the need to develop and implement evidence-based strategies to support their efforts to communicate with patients in a way which fosters higher vaccine confidence among the general population.

A number of strategies to support the immunization activities of GPs have been tried and described in the literature, although not all of them are evaluated for effectiveness. Examples of some strategies are: vaccination cards,43 reminder and recall messages,44 public service announcements,34 the provision of resources that support communication (e.g. Brochures, posters, lists of trusted websites),45,46 specialist immunization clinic consultation,47 health education exercises for parents or pregnant women43 and broader media campaigns (video and radio messages, etc.) Specific strategies for communication between GPs and patients that have been tested for effectiveness include motivational interviewing and presumptive communication.48–50 In the context of decreasing population trust in vaccines, a multitude of strategies should be implemented. In Bulgaria, guidelines including a summary of the principles of motivational interviewing have been developed and the discussion regarding vaccine confidence between GPs, regional health authorities, NGOs and the Ministry of Health has gained traction in the last years, particularly after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Information from this study has already been shared with various stakeholders, including the Ministry of Health, GPs and regional health authorities, to support them in devising evidence-based strategies.

There are several limitations to our study. First of all, participants responded to the questionnaire based on their self-reported behaviors. Even though the questionnaire is anonymous, reporting bias or social desirability bias cannot be excluded. Furthermore, the participation in the study was voluntary – it is also possible that people who were interested in and concerned about the present issue of VH might have been more disposed to respond to this questionnaire. In addition, the study provides a general overview of vaccine confidence. Further studies on the topic could delve deeper into the confidence toward various specific vaccines. Nonetheless, this is the first representative study in Bulgaria to investigate the attitudes of GPs toward mandatory childhood immunization and despite its limitations, it can be used as a basis for evidence-based recommendations and as a starting point for future studies.

Funding Statement

The study is financed by the Bulgarian National Science Fund – under the project “Childhood immunizations: a challenge to contemporary Bulgarian society (An investigation of communication issues arising between pediatricians and parents, aimed at identifying adequate measures to improve immunization coverage in Bulgaria)” (NO KP-06-OPR03/15, 19.12.2018].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Ethical statement

The Sofia University Ethical Committee reviewed and approved the research [decision: 93-В-155/27.6.2022). All participants have given informed consent to participate voluntarily and confidentially in the study.

References

- 1.Khubchandani J, Sharma S, Price JH, Wiblishauser MJ, Sharma M, Webb FJ.. COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy in the United States: a rapid national assessment. J Community Health. 2021;46(2):270–14. doi: 10.1007/s10900-020-00958-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Georgakopoulou T, Horefti E, Vernardaki A, Pogka V, Gkolfinopoulou K, Triantafyllou E, Tsiodras S, Theodoridou M, Mentis A, Panagiotopoulos T, et al. Ongoing measles outbreak in Greece related to the recent European-wide epidemic. Epidemiol Infect. 2018;146(13):1692–8. doi: 10.1017/S0950268818002170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deal A, Halliday R, Crawshaw AF, Hayward SE, Burnard A, Rustage K, Carter J, Mehrotra A, Knights F, Campos-Matos I, et al. Migration and outbreaks of vaccine-preventable disease in Europe: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21(12):e387–e98. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00193-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barret AS, Ryan A, Breslin A, Cullen L, Murray A, Grogan J, Bourke S, Cotter S. Pertussis outbreak in northwest Ireland, January – June 2010. Eurosurveillance. 2010;15(35). https://www.eurosurveillance.org/content/10.2807/ese.15.35.19654-en. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization . Poliomyelitis in Tajikistan: first importation since Europe certified polio-free. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2010;85(18):157–8. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/241555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization . Ten Threats to global health in 2019 [Homepage on the Internet. 2019. https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019.

- 7.SAGE Working Group . Report of the Sage Working Group on vaccine hesitancy [Homepage on the Internet]. 2014. https://www.asset-scienceinsociety.eu/sites/default/files/sage_working_group_revised_report_vaccine_hesitancy.pdf.

- 8.Collange F, Zaytseva A, Pulcini C, Bocquier A, Verger P. Unexplained variations in general practitioners’ perceptions and practices regarding vaccination in France. Eur J Public Health. 2019;29(1):2–8. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cky146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verger P, Fressard L, Collange F, Gautier A, Jestin C, Launay O, Raude J, Pulcini C, Peretti-Watel P. Vaccine hesitancy among general practitioners and its determinants during controversies: a national cross-sectional survey in France. EBioMedicine. 2015;2(8):891–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karafillakis E, Dinca I, Apfel F, Cecconi S, Wűrz A, Takacs J, Suk J, Celentano LP, Kramarz P, Larson HJ, et al. Vaccine hesitancy among healthcare workers in Europe: a qualitative study. Vaccine. 2016;34(41):5013–20. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ohannessian R, Constantinou P, Chauvin F. Health policy analysis of the non-implementation of HPV vaccination coverage in the pay for performance scheme in France. Eur J Public Health. 2019;29(1):23–7. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cky173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agrinier N, Le Maréchal M, Fressard L, Verger P, Pulcini C. Discrepancies between general practitioners’ vaccination recommendations for their patients and practices for their children. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2017;23(5):311–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2016.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilson RJI, Vergélys C, Ward J, Peretti-Watel P, Verger P. Vaccine hesitancy among general practitioners in Southern France and their reluctant trust in the health authorities. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-Being. 2020;15(1):1757336. doi: 10.1080/17482631.2020.1757336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Killian M, Detoc M, Berthelot P, Charles R, Gagneux-Brunon A, Lucht F, Pulcini C, Barbois S, Botelho-Nevers E. Vaccine hesitancy among general practitioners: evaluation and comparison of their immunisation practice for themselves, their patients and their children. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016;35(11):1837–43. doi: 10.1007/s10096-016-2735-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paterson P, Meurice F, Stanberry LR, Glismann S, Rosenthal SL, Larson HJ. Vaccine hesitancy and healthcare providers. Vaccine. 2016;34(52):6700–6. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Communication on immunisation – building trust [Homepage on the Internet] . 2012. [accessed 2023 Jul 5]. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/communication-immunisation-building-trust.

- 17.de Figueiredo A, Eagan RL, Hendrickx G, Karafillakis E, van Damme P, Larson HJ. State of vaccine confidence in the EU (2022) [Homepage on the Internet]. [accessed 2023 Sep 2]. https://health.ec.europa.eu/publications/state-vaccine-confidence-eu-2022_en.

- 18.Wiegand M, Eagan RL, Karimov R, Lin L, Larson HJ, de Figueiredo A. Global declines in vaccine confidence from 2015 to 2022: a large-scale retrospective analysis [Homepage on the Internet]. 2023. [accessed 2023 Sep 2]. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=4438003.

- 19.Larson HJ, De Figueiredo A, Xiahong Z, Schulz WS, Verger P, Johnston IG, Cook AR, Jones NS. The state of vaccine confidence 2016: global insights through a 67-country survey. EBioMedicine. 2016;12:295–301. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.08.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Figueiredo A, Simas C, Karafillakis E, Paterson P, Larson HJ. Mapping global trends in vaccine confidence and investigating barriers to vaccine uptake: a large-scale retrospective temporal modelling study. Lancet. 2020;396(10255):898–908. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31558-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larson HFA, Karafillakis E, Rawal M. State of vaccine confidence in the EU 2018. Luxembourg: European Union 2018; 2018. doi: 10.2875/241099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vaccine Confidence Index Map [Homepage on the Internet] . The Vaccine Confidence Project. [accessed 2023 Sep 3]. https://www.vaccineconfidence.org/vci/map/.

- 23.Siani A, Tranter A. Is vaccine confidence an unexpected victim of the COVID-19 pandemic? Vaccine. 2022;40(50):7262–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.10.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.WHO/UNICEF estimates of national immunization coverage [Homepage on the Internet] . [accessed 2023 Jul 5]. https://www.who.int/teams/immunization-vaccines-and-biologicals/immunization-analysis-and-insights/global-monitoring/immunization-coverage/who-unicef-estimates-of-national-immunization-coverage.

- 25.Muscat M, Marinova L, Mankertz A, Gatcheva N, Mihneva Z, Santibanez S, Kunchev A, Filipova R, Kojouharova M. The measles outbreak in Bulgaria, 2009–2011: an epidemiological assessment and lessons learnt. Eurosurveillance. 2016;21(9):30152. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.9.30152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kurchatova A, Krumova S, Vladimirova N, Nikolaeva-Glomb L, Stoyanova A, Kantardjiev T, Gatcheva N. Preliminary findings indicate nosocomial transmission and Roma population as most affected group in ongoing measles B3 genotype outbreak in Bulgaria, March to August 2017. Eurosurveillance. 2017;22(36):30611. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2017.22.36.30611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.COVID-19 vaccine tracker | European centre for disease prevention and control [Homepage on the Internet] . [accessed 2023 Jul 5]. https://vaccinetracker.ecdc.europa.eu/public/extensions/COVID-19/vaccine-tracker.html#uptake-tab.

- 28.Hadzhieva S/X. Factors shaping attitudes to immunization among parents of children up to the age of seven//Фактори, формиращи нагласите за имунизиране и ваксиниране сред родители на деца до 7 - годишна възраст [Homepage on the Internet]. 2019. [accessed 2023 Jul 5]. http://repository.mu-varna.bg/handle/nls/509.

- 29.Serbezova A, Mangelov M, Zaykova K, Nikolova S, Zhelyazkova D, Balgarinova N. Knowledge and attitude toward COVID-19 vaccines amongst medical, dental and pharmacy students. A cross-sectional study from Bulgaria. Biotechnol Biotechnol Equip. 2021;35(1):2024–32. doi: 10.1080/13102818.2022.2041097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rangelova V, Kevorkyan A, Raycheva R, Amudzhiyan D, Aleksandrova M, Sariyan S. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards the influenza vaccine among adult population in Plovdiv, Bulgaria. Arch Balk Med Union. 2021;56(3):329–35. doi: 10.31688/ABMU.2021.56.3.06. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pavlovic D, Sahoo P, Larson HJ, Karafillakis E. Factors influencing healthcare professionals’ confidence in vaccination in Europe: a literature review. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2022;18(1):2041360. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2022.2041360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Verger P, Collange F, Fressard L, Bocquier A, Gautier A, Pulcini C, Raude J, Peretti-Watel P. Prevalence and correlates of vaccine hesitancy among general practitioners: a cross-sectional telephone survey in France, April to July 2014. Eurosurveillance. 2016;21(47):30406. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.47.30406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alasmari A, Larson HJ, Karafillakis E. A mixed methods study of health care professionals’ attitudes towards vaccination in 15 countries. Vaccine. 2022;12:100219. doi: 10.1016/j.jvacx.2022.100219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gilkey MB, McRee A-L. Provider communication about HPV vaccination: a systematic review. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12(6):1454–68. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2015.1129090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Callaghan T, Washburn D, Goidel K, Nuzhath T, Spiegelman A, Scobee J, Moghtaderi A, Motta M. Imperfect messengers? An analysis of vaccine confidence among primary care physicians. Vaccine. 2022;40(18):2588–603. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gobert C, Semaille P, Van Der Schueren T, Verger P, Dauby N. Prevalence and determinants of vaccine hesitancy and vaccines recommendation discrepancies among general practitioners in French-speaking parts of Belgium. Vaccines. 2021;9(7):771. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9070771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee C, Whetten K, Omer S, Pan W, Salmon D. Hurdles to herd immunity: distrust of government and vaccine refusal in the US, 2002–2003. Vaccine. 2016;34(34):3972–8. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Verger P, Scronias D. Changes in general practitioners’ attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccination after first interim results: a longitudinal approach in France. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17(10):3408–12. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1943990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yaqub O, Castle-Clarke S, Sevdalis N, Chataway J. Attitudes to vaccination: a critical review. Social Sci Med. 2014;112:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raude J, Fressard L, Gautier A, Pulcini C, Peretti-Watel P, Verger P. Opening the ‘vaccine hesitancy’ black box: how trust in institutions affects French GPs’ vaccination practices. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2016;15(7):937–48. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2016.1184092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Downey L, Tyree PT, Huebner CE, Lafferty WE. Pediatric vaccination and vaccine-preventable disease acquisition: associations with care by complementary and alternative Medicine providers. Matern Child Health J. 2010;14(6):922–30. doi: 10.1007/s10995-009-0519-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McPhillips HA, Davis RL, Marcuse EK, Taylor JA. The rotavirus vaccine’s withdrawal and physicians’ trust in vaccine safety mechanisms. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155(9):1051. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.9.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oku A, Oyo-Ita A, Glenton C, Fretheim A, Ames H, Muloliwa A, Kaufman J, Hill S, Cliff J, Cartier Y, et al. Communication strategies to promote the uptake of childhood vaccination in Nigeria: a systematic map. Glob Health Action. 2016;9(1):30337. doi: 10.3402/gha.v9.30337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lwembe S, Green SA, Tanna N, Connor J, Valler C, Barnes R. A qualitative evaluation to explore the suitability, feasibility and acceptability of using a ‘celebration card’ intervention in primary care to improve the uptake of childhood vaccinations. BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17(1):101. doi: 10.1186/s12875-016-0497-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith MJ. Promoting vaccine confidence. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2015;29(4):759–69. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2015.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Frew PM, Chung Y, Fisher AK, Schamel J, Basket MM. Parental experiences with vaccine information statements: implications for timing, delivery, and parent-provider immunization communication. Vaccine. 2016;34(48):5840–4. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Forbes TA, McMinn A, Crawford N, Leask J, Danchin M. Vaccination uptake by vaccine-hesitant parents attending a specialist immunization clinic in Australia. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2015;11(12):2895–903. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2015.1070997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Opel DJ, Heritage J, Taylor JA, Mangione-Smith R, Salas HS, DeVere V, Zhou C, Robinson JD. The architecture of provider-parent vaccine discussions at health supervision visits. Pediatrics. 2013;132(6):1037–46. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-2037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dempsey AF, O’Leary ST. Human papillomavirus vaccination: narrative review of studies on how providers’ vaccine communication affects attitudes and uptake. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(2, Supplement):S23–S7. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2017.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reno JE, O’Leary S, Garrett K, Pyrzanowski J, Lockhart S, Campagna E, Barnard J, Dempsey AF. Improving provider communication about HPV vaccines for vaccine-hesitant parents through the use of motivational interviewing. J Health Commun. 2018;23(4):313–20. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2018.1442530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]