Abstract

Background and aims

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is characterized by several clinically important prognostic parameters, including portal vein thrombosis (PVT), tumor multifocality, and serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels, in addition to maximum tumor diameter (MTD). However, associations among these parameters have not been thoroughly examined. Thus, the study aimed to investigate the correlations among these HCC characteristics in a prospectively collected database.

Methods

An 8080 HCC patient database derived from our weekly HCC council meeting was examined with respect to the correlations at baseline patient presentation between increases in MTD and changes in the percentage of patients with PVT, multifocality, or AFP levels.

Results

The percentage of patients with PVT and with multifocality (tumor nodule numbers ≥3) significantly increased with enlarging MTD, regardless of the serum AFP level, showing the independence of PVT and multifocality on AFP. The percentage of patients with multifocality increased with enlarging MTD, in the presence or absence of PVT, showing the independence of multifocality from PVT. Therefore, discordance was found between different tumor parameters.

Conclusions

A statistically significant association was found between PVT and MTD and between multifocality and MTD, all three of which are independent of AFP. PVT and multifocality appeared to be independent of each other. Although PVT and multifocality were independent of AFP, they were also augmented with high serum AFP levels. The results suggest the possibility of multiple pathways of tumor progression in the later stages of HCC development.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), Portal vein thrombosis (PVT), Multifocality, Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), Heterogeneity

1. Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) tends at presentation to be beyond curative surgical intervention in most patients. It is characterized by several tumor characteristics that are thought to reflect aggressive biology and thus poor prognosis.1, 2, 3 These include, but are not limited to, tumor size or maximum tumor diameter (MTD), tumor multifocality, macroscopic invasion of the portal vein by tumor (PVT), leading to thrombosis that is observed on scans, and serum levels of alpha-fetoprotein (AFP). The first three (i.e., MTD, multifocality, and PVT) are observed radiologically. Thus, all four characteristics can be evaluated on routine clinical testing. Others, including tumor mutation burden, microsatellite instability, and newer genomics, are also thought to be prognostically important,4 but require specialized laboratory-based studies. This study aimed to assess the relationships between these four prognostic parameters to evaluate the heterogeneity of clinical HCC. We used information available to practicing clinicians (radiology and laboratory indices of HCC aggressiveness) to evaluate the evidence for the interconnectedness or otherwise among these aggressiveness characteristics. We found a significant relationship between MTD and both PVT and multifocality. These latter two characteristics appeared to be independent of each other, and all three appeared to be independent of AFP. These results suggest the presence of more than one progenitor cell and reflect considerable tumor heterogeneity. This heterogeneity may be considered in HCC classification systems and treatment selection.

2. Methods

2.1. Ethical approval

Database management conformed to legislation on privacy, and this study conforms to the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approval for this retrospective study on deceased cases and de-identified patients with HCC. This work was approved for a waiver by Ethics Committee of the Inonu University Faculty of Medicine (Institutional Review Board Approval No. 2022–3905) and waiver from obtaining written informed consent for these deceased and de-identified patients, in accordance with local guidelines and owning to the study’s retrospective nature.

2.2. Patient data

A database derived from our weekly HCC council meeting was examined for baseline tumor characteristics, which included 1747 adult (Table 1A, aged 63.28 ± 11.84, range 22–88 years) Turkish non-surgical patients with HCC, mainly from the Malatya region and surrounding provinces and are predominantly hepatitis B-based, who had macroscopic PVT, and baseline tumor parameter data from CT scans of MTD, number of tumor nodules, and baseline serum AFP levels. Another 6333 patients without macroscopic PVT were examined (Table 1B). The diagnosis was made either through tumor biopsy or according to the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases/European Association for the Study of the Liver guidelines. Nearly all patients had Child–Pugh class A or B and received locoregional therapy, except for a few who received only the best supportive care.

Table 1.

Comparisons of the number of tumor nodules among MTD in HCC patients (N = 8080) with PVT (+) (A) and PVT (−) (B).

| Parameters | MTD (cm) |

P-value^ | Comparisons (P-value)Ψ | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤2.0 | 2.1–5.0 | 5.1–8.0 | 8.1–11.0 | ||||||||

| (a) | (b) | (c) | (d) | (b) vs. (a) | (c) vs. (a) | (d) vs. (a) | (c) vs. (b) | (d) vs. (b) | (d) vs. (c) | ||

| (A) PVT + (n = 1747) | |||||||||||

| # Tumor nodules (%) | <0.001 | 0.434 | 0.003 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| #Nodule (1) | 45 (37.82) | 167 (31.69) | 131 (28.54) | 139 (21.65) | 0.210 | 0.060 | 0.001 | 0.282 | <0.001 | 0.010 | |

| #Nodule (2) | 44 (36.97) | 211 (40.04) | 135 (29.41) | 81 (12.62) | 0.533 | 0.124 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| #Nodule (≥3) | 30 (25.21) | 149 (28.27) | 193 (42.05) | 422 (65.73) | 0.490 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| (B) PVT− (n = 6333) | |||||||||||

| # Tumor nodules (%) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| #Nodule (1) | 1182 (66.89) | 1850 (57.51) | 401 (44.51) | 167 (37.28) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.030 | |

| #Nodule (2) | 430 (24.34) | 917 (28.50) | 230 (25.53) | 76 (16.96) | 0.001 | 0.502 | <0.001 | 0.072 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| #Nodule (≥3) | 155 (8.77) | 450 (13.99) | 270 (29.97) | 205 (45.76) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

Data are shown as n (%). Percentages may not total 100 because of rounding.

Abbreviations: HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; MTD, maximum tumor diameter; PVT, portal vein thrombosis.

^Chi-square test.

Ψtest for pairwise comparisons of proportions.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Patient parameters were reported as means ± standard deviations for continuous variables and as frequencies and percentages (%) for categorical variables. The normality of the distribution of quantitative variables was tested using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. To test the association among the groups, the Chi-square test for categorical variables was used. The Chi-square method for trend was performed to evaluate the trend between categorical levels for PVT positive (PVT+) and focality (foci 1, 2, and ≥3). For the continuous variable AFP (median), the non-parametric test for trend across ordered groups was used. The test for pairwise comparisons of proportions was used to compare differences in proportions between the categories examined. To evaluate the variation in the increase for the percentage of PVT + or multifocality, the equation of the interpolating line for each modification of variation of the increase was used. The variation of medians of AFP, percentage of PVT+, and percentage of focality (foci 1, 2, and ≥3) in relation to the increase in MTD was calculated both as a percentage variation from the first category of MTD (≤4.0 cm) and by a proportionality factor. This proportionality factor represents how many times the value of the single factor increased with enlarging MTD compared with the first category of MTD. Linear regression was used for testing trends in the tumor indices of PVT and multifocality in relation to MTD in categories of patients with HCC.

The probability level of a two-tailed error was 0.05.

All statistical analyses were made using Stata version 17 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Multifocality in relation to MTD

We initially focused on the relationship between tumor focality and MTD. Table 1 shows that both for participants with macroscopic PVT (PVT+) and without PVT (PVT−), a relationship was found between the number of tumor nodules and MTD, with statistical significance in both cases (P < 0.001). Thus, an increase in tumor multifocality did not depend on the presence of PVT. The examination of each nodule in patients with or without PVT showed an increase in the percentage of multifocality (≥3 tumor nodules) in relation to the tumor size (Table 1). The percentage of patients with only a single tumor nodule decreased with increased MTD. Interestingly, the trends in the percentage of patients with PVT decreases for very small nodules (column a) as the number of nodules increases; however, the trend for the percentage of patients with PVT increases for very large tumors (column d) as the number of nodules increases. This table emphasizes the complete dissociation of the number of nodules from PVT, since Table 1B only includes patients without PVT. Among patients with MTD having tumors measuring 8.1–11.0 cm (column d), 65.73% had multifocality (≥3 tumor nodules) in the PVT + group, and 45.76% still had multifocality in the PVT− group.

3.2. Multifocality in relation to PVT

Table 2B, Table 2A shows an increase in the percentage of patients with PVT as focality increases, in both patients with higher serum AFP levels (>200 IU/mL, Table 2A) and patients with low serum AFP levels (≤200 IU/mL, Table 2B). Thus, the association between PVT and MTD was independent of serum AFP levels. Table 2B expands the findings of Table 2A, that is, the percentage of patients with PVT, with an increase in tumor multifocality in relation to increases in MTD, in both patients with high serum AFP (Table 2A) or low serum AFP levels (Table 2B). The proportion of patients with PVT increased with each increase in MTD, that is, in patients with both high and low AFP levels. Notably, the PVT increases with enlarging MTD in patients with single tumor nodules Table 2B, Table 2AB, first row). Although the percentage of patients with PVT having two nodules was higher than those with one nodule, by and large, a slight increase was noted in patients with PVT having ≥3 nodules versus 2 nodules Table 2B, Table 2AB, second row versus third row). Again, the increase in the proportion of patients with PVT and enlarging MTD was independent of AFP levels and did not strongly relate to tumor focality because the increase occurred in patients with both single and multiple tumors.

Table 2B.

Comparisons of the percentage of PVT (+) among patients with HCC having different MTDs for single categories of the number of tumor nodules. All patients with AFP ≤200 (IU/mL) (n = 5775).

| Parameters | Total | MTD (cm) |

P-value^ | Comparisons (P-value) Ψ | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤2.0 | 2.1–5.0 | 5.1–8.0 | 8.1–11.0 | |||||||||

| (a) | (b) | (c) | (d) | (b)vs(a) | (c)vs(a) | (d)vs(a) | (c)vs(b) | (d)vs(b) | (d)vs(c) | |||

| (i) 1 Nodule | ||||||||||||

| PVT (+) (%) | 252 (7.78) | 35 (3.21) | 102 (6.14) | 60 (17.86) | 55 (36.67) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| (ii) 2 Nodules | ||||||||||||

| PVT (+) (%) | 254 (16.12) | 23 (5.68) | 124 (14.27) | 71 (31.70) | 36 (46.15) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.020 |

| (iii) ≥3 Nodules | ||||||||||||

| PVT (+) (%) | 307 (31.91) | 15 (11.03) | 68 (18.23) | 77 (35.81) | 147 (61.76) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Data are shown as n (%).

Abbreviations: AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; MTD, maximum tumor diameter; PVT, portal vein thrombosis.

^Chi-square test.

Ψtest for pairwise comparisons of proportions.

Table 2A.

Comparisons of the percentage of PVT (+) among patients with HCC having different MTDs for single categories of the number of tumor nodules. All patients with AFP>200 (IU/mL) (n = 2305).

| Parameters | Total | MTD (cm) |

P-value^ | Comparisons (P-value)Ψ | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤2.0 | 2.1–5.0 | 5.1–8.0 | 8.1–11.0 | |||||||||

| (a) | (b) | (c) | (d) | (b)vs(a) | (c)vs(a) | (d)vs(a) | (c)vs(b) | (d)vs(b) | (d)vs(c) | |||

| (i) 1 Nodule | ||||||||||||

| PVT (+) (%) | 230 (27.22) | 10 (7.35) | 65 (18.21) | 71 (36.22) | 84 (53.85) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.001 |

| (ii) 2 Nodules | ||||||||||||

| PVT (+) (%) | 217 (39.60) | 21 (30.43) | 87 (33.59) | 64 (45.39) | 45 (56.96) | <0.001 | 0.610 | 0.030 | 0.001 | 0.020 | <0.001 | 0.100 |

| (iii) ≥3 Nodules | ||||||||||||

| PVT (+) (%) | 487 (53.40) | 15 (30.61) | 81 (35.84) | 116 (46.77) | 275 (70.69) | <0.001 | 0.470 | 0.030 | <0.001 | 0.010 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Data are shown as n (%).

Abbreviations: AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; MTD, maximum tumor diameter; PVT, portal vein thrombosis.

^Chi-square test.

Ψtest for pairwise comparisons of proportions.

3.3. Variation of AFP, PVT, and focality in relation to MTD

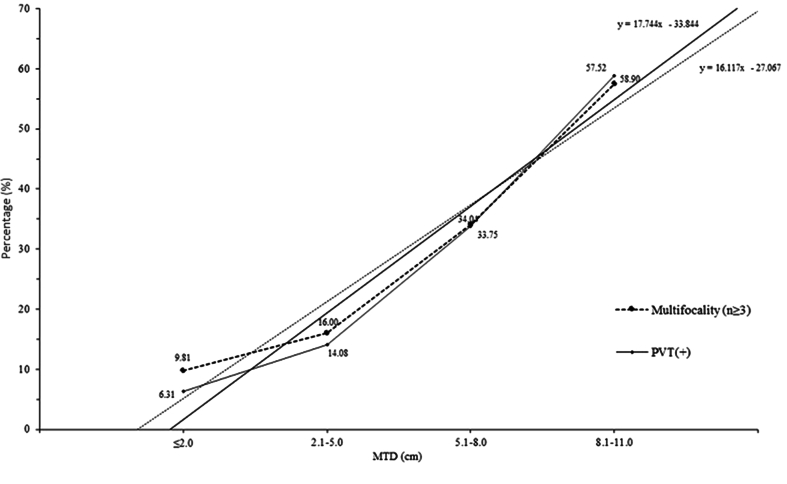

The extent of the changes in serum AFP levels, percentage of PVT, and percentage of focality were then determined in relation to the extent of changes in MTD (Table 3). This was done by determining whether the extent of the changes in each parameter was proportional to the extent of the increase in MTD (proportionality factor). The proportionality factors for AFP, percentage of PVT and multifocality (≥3) nodules, were all >1 for each parameter, indicating that their increases were proportionately greater than the MTD increases. The greatest proportionalities were found with AFP, followed by PVT and multifocality (≥3 foci), which were similar to each other. With the increase in MTD, both percentage of patients with PVT and percentage of patients with multifocality (≥3 foci) increased in both absolute and proportionality terms, in patients with both high and low serum AFP levels, indicating that serum AFP did not influence the percentage of PVT or multifocality. Fig. 1 shows the increase in the percentage of PVT and multifocality with enlarging MTD, with a significant trend. Furthermore, PVT and multifocality are nearly independent of each other with increasing tumor size, with tumor size below 5.1–8.0 cm. For larger tumors, not many differences are evident. In fact, a slight intersection was found between the two trend lines.

Table 3.

Variation in AFP, PVT (+), and focality for a single focal number in relation to MTD as categories. All in patients with HCC having AFP ≤200 IU/mL (A) and AFP >200 IU/mL (B).

| Interval MTD (cm) | Increase in MTD (cm)a | AFP (IU/mL) (median) | Proportionality factor from the first median value | PVT (+) (%) | Proportionality factor from the first median value | Nodule # (1) (%) | Proportionality factor from the first median value | Nodule # (2) (%) | Proportionality factor from the first median value | Nodule # (≥3) (%) | Proportionality factor from the first median value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) AFP ≤ 200 (IU/mL) | |||||||||||

| ≤4.0 | Ref. | 9.76 | – | 6.68 | – | 60.55 | – | 31.75 | – | 7.70 | – |

| 4.1–6.0 | 2 | 11.71 | 1.20 | 20.29 | 3.04 | 50.04 | 0.83 | 35.24 | 1.11 | 14.72 | 1.91 |

| 4.1–8.0 | 4 | 11.99 | 1.23 | 23.33 | 3.49 | 46.96 | 0.78 | 34.81 | 1.10 | 18.23 | 2.37 |

| 4.1–10.0 | 6 | 11.80 | 1.21 | 26.52 | 3.97 | 45.63 | 0.75 | 33.35 | 1.05 | 21.03 | 2.73 |

| 4.1–12.0 | 8 | 11.80 | 1.21 | 31.01 | 4.64 | 43.51 | 0.72 | 30.39 | 0.96 | 26.10 | 3.39 |

| (B) AFP > 200 (IU/mL) | |||||||||||

| ≤4.0 | Ref. | 875.63 | – | 23.00 | – | 45.87 | – | 35.81 | – | 18.31 | – |

| 4.1–6.0 | 2 | 2032.00 | 2.32 | 35.55 | 1.55 | 32.71 | 0.71 | 34.07 | 0.95 | 33.22 | 1.81 |

| 4.1–8.0 | 4 | 2517.45 | 2.88 | 39.74 | 1.73 | 34.49 | 0.75 | 31.30 | 0.87 | 34.20 | 1.87 |

| 4.1–10.0 | 6 | 2881.00 | 3.29 | 44.66 | 1.94 | 34.44 | 0.75 | 29.23 | 0.82 | 36.34 | 1.98 |

| 4.1–12.0 | 8 | 3515.00 | 4.01 | 51.07 | 2.22 | 30.78 | 0.67 | 23.82 | 0.66 | 45.40 | 2.48 |

Abbreviations: AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; MTD, maximum tumor diameter; PVT, portal vein thrombosis.

Increase in MTD compared with the reference MTD.

The proportionality factor relates the values of the AFP, PVT (+), and focality for a single focal number corresponding to the category of the tumor size with respect to the value referred to the first category of MTD.

This proportionality factor represents how many times the values of AFP, PVT (+), and focality for single focal number increase with increasing tumor size, compared with the first category of MTD (≤4.0 cm).

Fig. 1.

Trends in the tumor indices of PVT and multifocality in relation to MTD in categories of patients with HCC. Y axis, patients with multifocality (≥3) (% of patients) (P < 0.0001), PVT (+) (% of patients) (P < 0.0001); X axis, MTD. Abbreviations: HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; MTD, maximum tumor diameter; PVT, portal vein thrombosis.

3.4. Relationship between PVT and MTD among different serum AFP bands

The percentage of patients with PVT was compared according to MTD and stratified according to five AFP bands, which including ≤100,101∼≤200, 201∼≤400, 401∼≤800, and >800 IU/mL (Table 4). Although the percentage of patients with PVT increased with enlarging MTD in each AFP band, at any given MTD, little discernible difference was found in the percentage of patients with PVT as the serum AFP levels increased from 101∼ ≤200 to >800 IU/mL. Thus, the association of PVT with MTD was again found to be independent of the serum AFP levels.

Table 4.

Comparisons of the percentage of PVT (+) among patients with HCC and different MTDs for single categories of AFP (IU/mL). All patients with #Nodule (1) (n = 4082).

| Parameters | Total | MTD (cm) |

P-value a | Comparisons (P-value) b | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤2.0 |

2.1–5.0 |

5.1–8.0 |

8.1–11.0 |

|||||||||

| (a) | (b) | (c) | (d) | (b)vs(a) | (c)vs(a) | (d)vs(a) | (c)vs(b) | (d)vs(b) | (d)vs(c) | |||

| AFP ≤ 100 | ||||||||||||

| PVT (+) (%) | 219 (7.28) | 34 (3.32) | 89 (5.75) | 49 (16.01) | 47 (35.07) | <0.001 | 0.003 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 101 ≤ AFP ≤ 200 | ||||||||||||

| PVT (+) (%) | 33 (14.54) | 1 (1.47) | 13 (11.50) | 11 (36.67) | 8 (50.00) | <0.001 | 0.003 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.007 | 0.003 | 0.380 |

| 201 ≤ AFP ≤ 400 | ||||||||||||

| PVT (+) (%) | 27 (14.75) | 3 (5.66) | 10 (11.49) | 7 (26.92) | 7 (41.18) | 0.001 | 0.210 | 0.020 | 0.005 | 0.100 | 0.020 | 0.340 |

| 401 ≤ AFP ≤ 800 | ||||||||||||

| PVT (+) (%) | 21 (15.79) | 0 (0) | 12 (16.90) | 6 (30.00) | 3 (42.86) | 0.004 | – | – | – | 0.240 | 0.180 | 0.550 |

| AFP > 800 | ||||||||||||

| PVT (+) (%) | 182 (34.40) | 7 (14.58) | 43 (21.61) | 58 (38.67) | 74 (56.06) | <0.001 | 0.230 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.001 | <0.001 | 0.003 |

Data are shown as n (%).

Abbreviations: AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; MTD, maximum tumor diameter; PVT, portal vein thrombosis.

Chi-square test.

test for pairwise comparisons of proportions.

4. Discussion

Many studies have reported prognostic factors of HCC, which are broadly divided into liver damage and tumor factors. The best-studied tumor factors are the maximum tumor size or MTD, PVT, tumor multifocality, and serum AFP levels secreted by HCC cells.5, 6, 7 Despite this, <50% of patients with HCC in most series have high AFP levels, which has limited sensitivity and specificity.8, 9, 10 Nevertheless, high AFP levels are regarded as reflecting poor prognosis and a risk factor for liver transplantation in patients with HCC.11,12 However, why it is a poor prognosis factor or what mechanisms of HCC biology that high serum AFP levels reflect is unclear. Despite being associated with larger tumors, many studies have reported patients with large HCCs who do not have high AFP levels.6,7,10 Thus, high AFP levels may represent a subset of patients with HCC, or only one of the several possible HCC growth cascades.

Similarly, the probability of patients having PVT has increased with enlarging MTD;13 however, the mechanisms underlying this relationship are also unclear. Both PVT and multifocality represent the motility and invasiveness of HCC cells. In PVT, the portal vein or its tributaries are invaded, and in multifocality, invasion occurs in the liver parenchyma in areas close to the primary HCC. Another path to multifocality is that cirrhotic nodules are potentially pre-malignant and may produce synchronous or metachronous multiple primary tumors. Given the above four features of HCC aggressiveness, assessing whether they were related appeared reasonable. Table 1 shows two main findings. In Table 1A (PVT + group), multifocality (≥3 tumor nodules) increased with enlarging MTD. This was also found in Table 1B (PVT− group), thus dissociating a consistent relationship between PVT and multifocality. It also showed the dissociation in another way because patients with only a single nodule could also have PVT. Table 2B, Table 2A expands the relationship of PVT to multifocality but adds in the prism both AFP and MTD. In Table 2B, Table 2AA and B, the proportion of patients with PVT increased in relation to an increase in both MTD and focality, both for patients with high and low serum AFP levels. Thus, AFP was not necessary for the increase in percent PVT as the MTD enlarged, even though it augmented MTD enlargement. Similarly, percent PVT increased even if a single nodule grew, regardless of AFP, although the percent PVT was also greater in patients with high AFP levels. These results are consistent with the idea that high serum AFP levels might augment the increase in both PVT and multifocality that occurs with enlarging MTD (Table 3A versus 3B), although it is not necessary for either PVT or multifocality. Given that AFP does not clearly have liver growth properties, it is unlikely to directly participate in MTD enlargement. As shown in Table 3A and published in an unrelated study,6,7 large HCCs can grow in the absence of high AFP levels. With time and tumor progression, the pool of AFP-positive cells may expand (increase in serum AFP levels) but may also de-differentiate or trans-differentiate (decrease in serum AFP levels). For example, some HCC cell lines show an epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM)-positive cancer stem cell phenotype that expresses high AFP.14 A study on epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition showed that epithelial-type HCC cells had strong AFP expression, whereas mesenchymal phenotype HCC cells can have nearly undetectable AFP levels.15 Furthermore, regarding trends (Fig. 1), no strong intersection was found between multifocality and PVT but separate processes. The lack of a relationship between AFP and MTD or PVT is reinforced by the findings of Table 4. The columns show that for any MTD, the increase in PVT changes is small (2–3 folds) compared with the increase in serum AFP levels (8-fold), as shown in the rows.

Thus, the effects of high AFP levels on HCC biology and prognosis are likely to be indirect because they relate poorly to MTD, PVT, or focality, as shown here. Alternatively, they may relate to some other prognostically important factors that have not been measured here. Since nearly 50% of patients with HCC have high serum AFP levels,16 HCCs can be considered heterogeneous, and patients with high or low serum AFP levels may represent different HCC subsets, thus slightly different in principle from patients with breast cancer having high or low hormone receptor levels (estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2) and different biology. Since high AFP levels predict poor prognosis in multiple HCC studies, its actions are on parameters not measured here, or at least not directly. Even though it is not necessary for HCC growth, PVT, or multifocality, which can all increase in patients with low serum AFP levels (Table 2B, Table 2A, Table 3, Table 4), it could still be an augmenter for any of them, which is consistent with the data in these tables.

PVT, and to a lesser extent tumor multifocality, is a major adverse prognostic factor for patients with HCC. Both of these characteristics involve tumor invasion and migration through the tissue, i.e., through the portal vein wall (PVT) and liver parenchyma (tumor multifocality). The proportionality factors to MTD of each are comparable (Table 3A); however, when plotted graphically, they do not intersect (Fig. 1), suggesting that they may be independent if the processes are comparable. Why they are predictors of poor outcomes is also unclear, although PVT is also associated with poorer residual liver function,6,13 either as a cause or a consequence. Furthermore, patients with HCC die as a result of liver damage, tumor growth, or both, as reflected in most classification systems.17

Possibly the simplest interpretation of these findings is that PVT/multifocality, MTD, and AFP represent different processes that are derived from different subclones. The only consistent relationship is between the increase in MTD and the increase in percent PVT/multifocality. Thus, MTD/multifocality increases could arise from an increase in the number of progenitor cells that accompany MTD enlargement; however, the role of a high AFP level and its contribution to decreased survival in patients with HCC has yet to be clarified. However, a recent study showed that AFP inhibits apoptosis and cell autophagy; alters cell cycle, several cyclins, and signal transduction; is involved in matrix degradation, which is a necessary aspect of cell migration; and can inhibit both lymphocyte and macrophage function.18

Most likely, PVT and multifocality have separate, though similarly, changing originator cells because multifocality can occur in the absence of PVT (Table 1) and PVT can develop in the presence of single HCCs with different MTD Table 2B, Table 2A. However, PVT can also develop in the presence of multifocality (same tables); just as percent multifocality can increase with enlarging MTD in the presence or absence of PVT (Table 1A and B).

These results suggest the existence of at least two types of progenitor cells, one each for PVT and one for multifocality. They appear to increase with MTD enlargement. Their existence may be amplified by high serum AFP levels, although both percent PVT and percent multifocality can increase with enlarging MTD, even in the absence of high serum AFP levels. Accordingly, an originator or stem cell drives HCC growth through its proliferation. Some of its descendent cells subsequently acquire the ability to migrate and/or invade tissue, or possibly, more than one type of progenitor cell is present from the beginning, and under pressure from the growth of the initial mass, these cells then start to proliferate, with some having invasive properties. The latter hypothesis implies that more than one progenitor cell type can explain the clinical observations. Indeed, several cancer progenitor cell phenotypes have been described, having various combinations of proteins, including AFP and EpCAM.19 If true, the therapeutic killing of cancer cells using a single drug might be insufficient for effective HCC control. Several drugs with their specific target growth pathways might be needed, or more likely, the use of different classes of agents from those used at present that might target HCC invasiveness in a non-hepatotoxic manner because HCCs usually arise on a chronically damaged liver, which is thus sensitive to further damage by cancer therapies. In general, tumors do not kill their hosts by growth alone but by growth and spread. Thus, therapeutic agents that might be useful include those that induce the differentiated hepatocyte phenotype or modulate the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, which is a characteristic of tumor aggressiveness.20,21 These findings of discordance between HCC parameters suggest considerable heterogeneity and support the idea that more than one progenitor cell may be involved. This has implications for classification systems and possibly the need for multiple treatment types for advanced HCCs. HCCs are also in a state of dynamic change, with an increase in size being associated with changes in tumor number and PVT (tumor evolution),22,23 both with and without associated inflammation, suggesting the involvement of more than one growth pathway.7 While this study is limited by its retrospective nature and only four tumor factors are studied.

5. Conclusion

In the study, a statistically significant association could be found between PVT and MTD and between multifocality and MTD, but all three of which are independent of AFP. Multiple pathways of tumor progression in the later stages of HCC development should be considered.

Strobe statement

The authors have read the STROBE statement – checklist of items, and the manuscript was prepared according to its checklist of items.

Authors’ contributions

Brian I. Carr: concepting ideas and writing; Vito Guerra: biostatistics and paper proof reading; Volkan Ince, Burak Isik and Sezai Yilmaz: data collection. All authors have read and agreed to the submitted version of the manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH grant CA 82723 (Brian I. Carr).

Footnotes

Edited by Yuxia Jiang and Peiling Zhu.

References

- 1.Ouida K., Ohtsuki T., Obata H., et al. Natural history of hepatocellular carcinoma and prognosis in relation to treatment. Study of 850 patients. Cancer. 1985;56:918–928. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142. 19850815)56:4<918::aid-cncr2820560437>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Subramanian S., Kelley R.K., Venook A.P. A review of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) staging systems. Chin Clin Oncol. 2013;2:33. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2304-3865.2013.07.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carr B.I., Guerra V., Giannini E.G., et al. A liver index and its relationship to indices of HCC aggressiveness. J Integr Oncol. 2016;5:178. doi: 10.4172/2329-6771.1000178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Refolo M.G., Messa C., Guerra V., Carr B.I., D’Alessandro R. Inflammatory mechanisms of HCC development. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12:641. doi: 10.3390/cancers12030641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carr B.I., Guerra V. Validation of a liver index and its significance for HCC aggressiveness. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2017;48:262–266. doi: 10.1007/s12029-017-9971-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carr B.I., Guerra V., Donghia R., et al. Identification of clinical phenotypes and related survival in patients with large HCCs. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13:592. doi: 10.3390/cancers13040592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carr B.I., Bag H.G., Akkiz H., et al. Identification of 2 large size HCC phenotypes, with and without associated inflammation. Clin Pract. 2022;19:1953–1958. doi: 10.37532/fmcp.2022.19(4).1953-1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giannini E.G., Marenco S., Borgonovo G., et al. Alpha-fetoprotein has no prognostic role in small hepatocellular carcinoma identified during surveillance in compensated cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2012;56:1371–1379. doi: 10.1002/hep.25814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zong J., Fan Z., Zhang Y. Serum tumor markers for early diagnosis of primary hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. 2020;7:413–422. doi: 10.2147/JHC.S272762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pang R.W., Joh J.W., Johnson P.J., Monden M., Pawlik T.M., Poon R.T. Biology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:962–971. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9730-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ince V., Akbulut S., Otan E., et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: malatya experience and proposals for expanded criteria. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2020;51:998–1005. doi: 10.1007/s12029-020-00424-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Magro B., Pinelli D., De Giorgio M., et al. Pre-transplant alpha-fetoprotein > 25.5 and its dynamic on waitlist are predictors of HCC recurrence after liver transplantation for patients meeting Milan criteria. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13:5976. doi: 10.3390/cancers13235976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akkiz H., Carr B.I., Kuran S, et al. Macroscopic portal vein thrombosis in HCC patients. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;2018 doi: 10.1155/2018/3120185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo Z., Li L.Q., Jiang J.H., Ou C., Zeng L.X., Xiang B.D. Cancer stem cell markers correlate with early recurrence and survival in hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:2098–2106. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i8.2098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamada S., Okumura N., Wei L., et al. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition is associated with shorter disease-free survival in hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:3882–3890. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3779-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li C., Zhang Z., Zhang P., Liu J. Diagnostic accuracy of des-gamma-carboxy prothrombin versus α-fetoprotein for hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review. Hepatol Res. 2014;44:E11–E25. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Couto O.F., Dvorchik I., Carr B.I. Causes of death in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:3285–3289. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-9750-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zheng Y., Zhu M., Li M. Effects of alpha-fetoprotein on the occurrence and progression of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2020;146:2439–2446. doi: 10.1007/s00432-020-03331-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamashita T., Ji J., Budhu A., et al. EpCAM-positive hepatocellular carcinoma cells are tumor-initiating cells with stem/progenitor cell features. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1012–1024. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang L., Yang Y.D., Fu L., et al. CLDN3 inhibits cancer aggressiveness via Wnt-EMT signaling and is a potential prognostic biomarker for hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2014;5:7663–7676. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sengez B., Carr B.I., Alotaibi H. EMT and inflammation: crossroads in HCC. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2023;54:204–212. doi: 10.1007/s12029-021-00801-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carr B.I., Guerra V., Donghia R., Yilmaz S. Trends in tumor indices in relation to increased hepatocellular carcinoma size: evidence for tumor evolution as a function of growth. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2020;51:1215–1219. doi: 10.1007/s12029-020-00530-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carr B.I., Guerra V., Donghia R., et al. Changes in hepatocellular carcinoma aggressiveness characteristics with an increase in tumor diameter. Int J Biol Markers. 2021;36:54–61. doi: 10.1177/1724600821996372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]