Abstract

Exposure to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) is a well-established risk factor for suicidality in adolescence and young adulthood. However, the specific mechanisms underlying this relationship remain unclear. Existing research and theoretical frameworks suggest alterations in cognitive and affective processes may account for this association. Intolerance of uncertainty (IU) exacerbates negative affect and arousal states and may contribute to sustained distress. It is therefore plausible that ACEs may be associated with high IU, and in turn, high IU may be associated with increased suicide risk. The present study directly tests this hypothesis in a cohort of youth (18–19 years) with varying ACE exposure. Participants with and without a history of trauma (N=107) completed a battery of self-report questionnaires to assess ACEs, IU, and suicide risk. Results revealed ACEs were significantly associated with both IU and suicide risk. IU and suicide risk were also correlated. Importantly, findings demonstrated a significant indirect effect of ACEs on suicide risk through IU. Findings converge with broader literature on the relationship between childhood adversity and suicidality and extend previous research by highlighting IU as a mediator of this relationship, positing IU as a potentially viable target for suicide prevention among those with a history of ACEs.

Keywords: adverse childhood experiences, suicide risk, intolerance of uncertainty, youth

1. Introduction

Suicide is a pressing global health concern and a leading cause of death worldwide. Close to 1 million individuals around the world and approximately 46,000 individuals in the United States die by suicide annually, and an additional 1.4 million non-fatal suicide attempts are reported in the U.S. each year (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2023; World Health Organization [WHO], 2019). While suicide is a major threat across the lifespan, youth suicide rates have surged in recent years, and suicidal ideation and behavior among adolescents is endorsed at disproportional rates (Bilsen, 2018; Nock et al., 2013). Suicidal thoughts and behaviors frequently emerge during adolescence and suicide is the second leading cause of death in young people (Curtin et al., 2022; Hawton et al., 2012). These rates are alarming, given that more than half of adolescent deaths by suicide are first-time attempts (Bostwick et al., 2016), and in some instances, suicidal ideation is the only early indicator of risk (Klonsky et al., 2016). Unlike many leading causes of death, suicide is largely preventable when timely intervention is available. There is an urgent need to identify who may be at increased risk of suicide, particularly among youth, to aid in the development of more targeted and effective prevention and intervention strategies.

Decades of research have identified adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) as well-established risk factors for suicidal behavior in adolescence and early adulthood (Beautrais et al., 1996; Dube et al., 2001; Fuller-Thomson et al., 2016). ACEs refer to trauma and adversity, including abuse, neglect, and a range of household dysfunctions, experienced prior to age 18 (Dube et al., 2001). Population-based research has found the likelihood of strongly considering or attempting suicide in adulthood increased more than threefold in individuals with multiple self-reported ACEs compared to those with none (Thompson et al., 2019). There is a demonstrated correlation between ACEs and suicidal behavior throughout the lifespan that is proportional to the reported number of adverse experiences (Dube et al., 2001; Merrick et al., 2017). Additionally, ACEs have been strongly associated with suicide attempts among adolescents (Beautrais et al., 1996; van der Kolk et al., 1991).

Existing theory and research suggest the association between ACEs and suicide risk may, in part, be explained by changes in affective processes. Prior literature has demonstrated that young adults with exposure to multiple ACEs frequently exhibit increased impulsivity while experiencing distress and negative emotions (Shin et al., 2018), and individuals who die by suicide because of impulsive actions are more likely to have a history of childhood adversity (Zouk et al., 2006). The reported frequency of psychological distress also increases substantially with the number of ACEs experienced (Manyema et al., 2018). Long-term deficits in socioemotional processing have been observed in individuals with a history of ACEs, even when ACEs are determined to be mild in severity (Mirman et al., 2020). Both psychological distress and difficulty with socioemotional processing are connected to suicide risk (Bailey et al., 2011; Tang et al., 2018). Despite these findings and theoretical perspectives, the modifiable mechanisms by which these relationships occur remain unclear.

One possible mechanism by which ACEs may lead to increased suicide risk is intolerance of uncertainty (IU). IU is a tendency to respond to uncertain events and situations with negative cognitive, behavioral, and/or physiological reactions (Carleton, 2016). Individuals high in IU react negatively to uncertainty and have difficulty coping with unpredictable or ambiguous stressors. IU alters threat biases, attention processes, safety learning, probability calculations, and psychophysiological reactivity (Grupe & Nitchke, 2013). Maladaptive responses to uncertainty exacerbate negative affect and arousal states (Greco & Roger, 2003), which in turn underlies desires for escape, avoidance, and affective relief. Notably, ACEs are typically unpredictable and uncontrollable and therefore reflect real-life exposure to uncertainty. It is possible that ACEs could sensitize (at least some) individuals to uncertainty and foster the maladaptive beliefs and tendencies that are characteristic of high IU.

Given the existing support for the notion that exaggerated sensitivity to uncertainty contributes to maladaptive beliefs and responses (Grupe & Nitchke, 2013), it is plausible to consider a potential association between IU and suicidality. In the face of ambiguity, individuals high in IU have a tendency to perceive their circumstances as negative and overestimate the likelihood of negative outcomes, fueling distress and negative affect (Kleiman & Nock, 2018; McEvoy & Mahoney, 2012). Related, emotional relief and situational escape have been identified as two of the most common motives reported by individuals who have attempted suicide (Bryan et al., 2014). It is possible those with high IU experience frequent and persistent distress, and some may consider suicide a certain or predictable form of escape. In support of this association, several studies have demonstrated that individuals with a history of suicidal ideation exhibit abnormal responses to uncertain outcomes (Gorka et al., 2023; Lieberman et al., 2020). Together, the literature indicates that IU may be an important mediator of the association between ACEs and suicide risk, though no prior study to our knowledge has directly tested this hypothesis.

The present study aimed to address an important research gap by examining whether individual differences in IU mediate the association between ACEs and suicide risk in a cohort of youth with a wide range of ACEs. Consistent with prior literature, we hypothesized that childhood adversity would be positively associated with suicide risk. We further expected to uncover an indirect relationship between these factors through IU, at least in part, such that increased prevalence of ACEs would be associated with heightened IU, and in turn, heightened IU would be associated with greater risk for suicide.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

Participants were recruited via advertisements posted throughout the community (e.g., school campuses, community centers) and online and enrolled in a larger longitudinal study examining neurobiological mechanisms underlying the association between trauma exposure and psychopathology. Data were collected between June, 2021 and May, 2023. The protocol was approved by The Ohio State University Institutional Review Board and performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments. Participants were compensated monetarily for their time. All participants in the present study were required to be 16–19 years old and be able to provide written informed consent. Given that the aims of the larger study included prediction of initial onset of alcohol use disorder (AUD), participants were required to have had minimal alcohol exposure at baseline enrollment (i.e., self-reported consuming >1 but <100 standard alcoholic drinks in their lifetime) and be at-risk for the onset of AUD by virtue of self-reporting affiliation with risky peers and/or having access to alcohol. Exclusion criteria included current psychotropic medication use, any serious medical or neurological condition, lifetime history of mania or psychosis, active suicidal intent, lifetime history of any alcohol or substance use disorder, deafness, and pregnancy. A total of 107 adults, ages 18 and 19, met inclusionary criteria and were included in the present study. Participants completed a virtual screening session that included informed consent, diagnostic interviews, and a battery of self-report questionnaires. The sample’s clinical and demographic characteristics are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics and Characteristics

| Demographics | |

| Age in years | 18.55 (0.50) |

| Sex (% female) | 69.16% |

| Ethnicity (% Hispanic) | 11.22% |

| Education level (years) | 12.09 (0.91) |

| Trauma group (yes) | 57.94% |

| Race | |

| White | 66.36% |

| Black | 13.08% |

| Asian | 7.48% |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 0.00% |

| More than one race | 11.21% |

| Unknown | 1.87% |

| Lifetime DSM-5 Diagnoses | |

| Major Depressive Disorder | 57.01% |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | 10.28% |

| Social Anxiety Disorder | 17.76% |

| Panic Disorder | 0.93% |

| Specific Phobia | 3.74% |

| Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder | 26.17% |

| Alcohol Use Disorder | 0.00% |

| Substance Use Disorder | 0.00% |

| Self-Reported Behaviors and Clinical Symptoms | |

| Average SCS-R score | 9.94 (10.73) |

| Average ACES score | 3.28 (3.06) |

| Average IUS-12 score | 31.73 (10.19) |

| Lifetime history of suicidal ideation (% yes) | 57.00% |

| Lifetime history of suicide attempt (% yes) | 8.41% |

| Average number of lifetime alcoholic drinks | 39.83 (26.80) |

Note. SCS-R = Suicide Cognitions Scale – Revised; ACES = Adverse Childhood Experience Survey; IUS-12 = Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale – Short Form.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Adverse Childhood Experiences

Exposure to ACEs was assessed using the Adverse Childhood Experience Survey (ACES; Finkelhor et al., 2015), a retrospective self-report measure in which individuals are asked to report on a dichotomous (yes/no) scale whether they experienced various ACEs prior to the age of 18. The ACES measure is designed to capture exposure to 14 forms of adversity, including: (1) emotional abuse, (2) physical abuse, (3) sexual assault, (4) emotional neglect, (5) physical neglect, (6) parental separation/divorce, (7) domestic violence, (8) family substance misuse/abuse, (9) family mental illness, (10) parental incarceration, (11) poverty, (12) peer victimization, (13) social isolation, and (14) exposure to community violence. Item responses are summed to obtain a total ACES score ranging from 0 to 14, with higher scores indicating greater exposure to ACEs. Internal consistency for the ACES in the current study was good (α = .82).

2.2.2. Intolerance of Uncertainty

IU was assessed using the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale – Short Form (IUS-12; Carleton et al., 2007). The IUS-12, an abbreviated version of the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale (IUS; Freeston et al., 1994), is a 12-item questionnaire that evaluates responses to uncertainty, ambiguous situations, and the future. Respondents rate the extent to which each item is characteristic of them on a 5-point Likert scale with responses ranging from 1 (not at all characteristic of me) to 5 (entirely characteristic of me). Item responses are summed to create a total IUS-12 score ranging from 12 to 60, with higher scores indicating higher levels of IU. Internal consistency for the IUS-12 in the current study was excellent (α = .92).

2.2.3. Suicide Risk

Suicide risk was determined using the Suicide Cognitions Scale – Revised (SCS-R; Bryan et al., 2021). The SCS-R is a 16-item self-report measure used to evaluate suicidogenic thoughts and beliefs including hopelessness, perceived burdensomeness, entrapment, and unbearability (Bryan et al., 2014). Numerous studies have demonstrated that SCS-R scores are superior to traditional measures of suicide risk in predicting suicidal behaviors (Bryan et al., 2014, 2022; Rudd & Bryan, 2021). SCS-R scores also differentiate suicide attempters from non-attempters (Bryan et al., 2021, 2022; Rudd & Bryan, 2021). Respondents rate their level of agreement with each statement on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Item responses are summed to obtain a total SCS-R score ranging from 0 to 64, with higher scores reflecting increased vulnerability to suicidal behavior. Internal consistency for the SCS-R in the current study was excellent (α = .95).

2.3. Data Analysis Plan

There were no missing data in the dataset and ACES, IUS-12, and SCS-R scores were all normally distributed. We first examined associations between study variables using a series of Pearson’s correlations. A test of mediation was then conducted using PROCESS, an SPSS macro for path-analysis based modeling (Hayes, 2017). PROCESS (Model 4) provides bootstrapped bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals of the indirect effect using 5,000 bootstrapped samples (Hayes, 2017). According to Preacher and Hayes (2008), the indirect effect is significant if the confidence interval does not contain zero. ACES score was specified as the independent variable, IUS-12 total score as the mediator, and SCS-R total score as the dependent variable. Age and sex were included as model covariates.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptives and Correlations

ACES was positively correlated with IUS-12 (r = 0.25, p = .009) and SCS-R scores (r = 0.32, p < .001). IUS-12 scores and SCS-R scores were also positively correlated (r = 0.31, p = .001). There were no differences between males and females on any study variable. The average ACES score was 3.28, though ACES total ranged from 0 to 13. Peer victimization was the most frequently endorsed ACE and was reported by 51.40% of participants, followed by emotional abuse and emotional neglect (reported by 44.86% and 39.25% of participants, respectively).

Regarding suicide risk, 8.41% of participants reported a prior suicide attempt and 57.01% reported lifetime suicidal ideation. A total of 69.15% of participants experienced at least one DSM-5 Criterion A traumatic stressor. Additional descriptive statistics and sample characteristics are presented in Table 1.

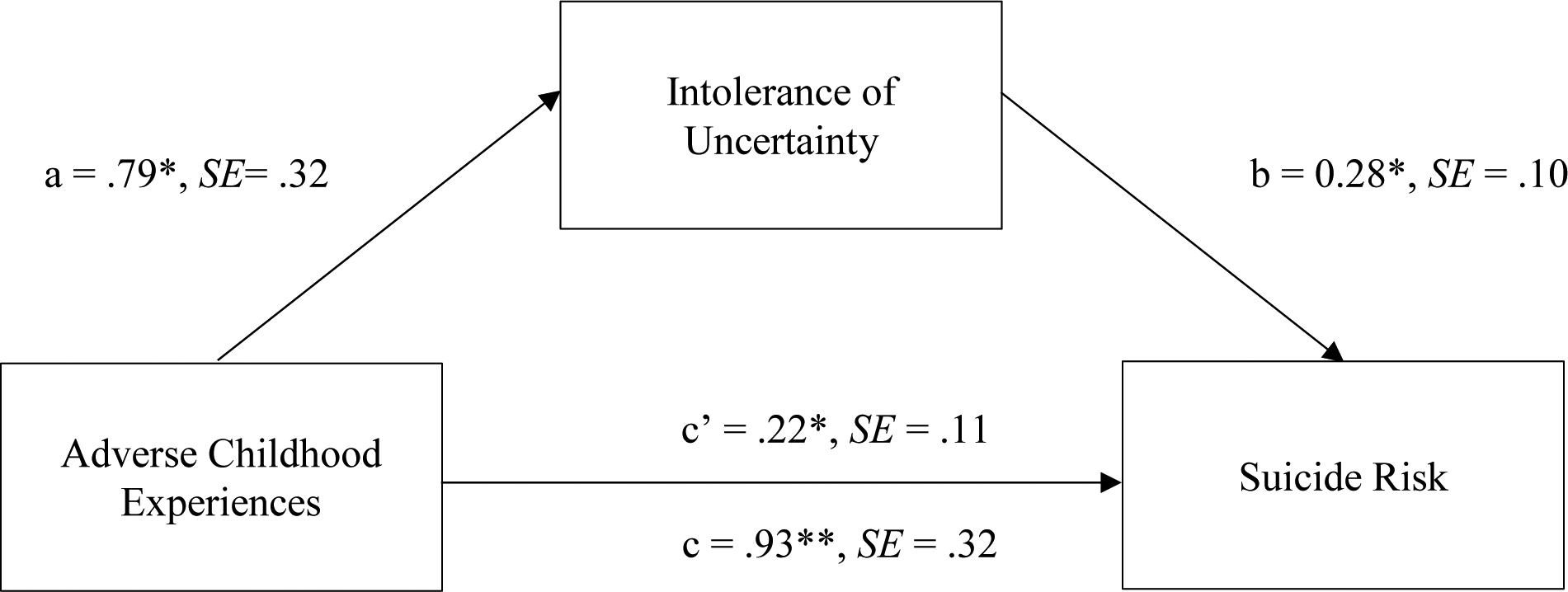

3.2. Mediation Model

Results revealed that greater ACES was associated with greater IUS-12 scores (a path: b = 0.78, SE=0.32, p=.016, 95% confidence interval, or CI = [0.15, 1.42]). Greater IUS-12 scores were also associated with greater SCS-R scores while controlling for ACES (b path: b = 0.28, SE = 0.10, p=.005, 95% CI = [0.09, 0.47]). As expected, there was a direct positive effect of ACES on SCS-R scores (c path: b = 0.93, SE=0.32, p = .005, 95% CI= [0.29, 1.57]). Most importantly, the overall mediation model was significant and there was an indirect effect of ACES on SCS-R scores through IUS-12 scores (c’ path: b=0.22, SE= 0.11, 95% CI = [0.03, 0.46]; Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Analysis of the effects of exposure to adverse childhood experiences on intolerance of uncertainty and suicide risk. Values represent unstandardized coefficients. *indicates p < .05; **indicates p < .01.

4. Discussion

Childhood adversity is a known risk factor for suicide, though the mechanisms underlying this association are not well understood. The present study was the first to our knowledge to examine the role of IU in the relationship between ACEs and suicide risk in a youth cohort. Results indicated that greater exposure to childhood adversity was associated with increased suicide risk, as expected. Importantly, analyses also revealed that intolerance of uncertainty significantly mediated this relationship, which suggests heightened IU may be one potential pathway through which ACEs increase suicide risk. These findings are consistent with our hypotheses and broadly corroborate theory and research suggesting that individual differences in tolerating and responding to uncertainty contribute to adverse outcomes in those exposed to adversity.

Results revealed that greater exposure to childhood adversity was significantly associated with greater suicide risk, consistent with prior studies (e.g., Dube et al., 2001; Fuller-Thomson et al., 2016). The present findings support and extend existing literature on the association between ACEs and suicide risk by demonstrating a general vulnerability to the negative consequences of early life adversity and highlighting long-term impacts of ACEs. Additionally, our research contributes novel insights by demonstrating this association using the SCS-R self-report measure. Unlike traditional measures of suicide risk which primarily assess frequency and severity of suicidal thoughts and behaviors, the SCS-R explores underlying cognitive aspects that heighten vulnerability to suicide (Bryan et al., 2014). The SCS-R has been shown to be a more sensitive and specific predictor of suicidal behavior compared to traditional measures of suicide risk, given its focus on measuring cognitive vulnerability to suicide by capturing maladaptive beliefs which tend to remain present even in the absence of active suicidal ideation (Bryan et al., 2014, 2022; Rudd & Bryan, 2021). Our results demonstrate a direct correlation between ACEs and cognitions that amplify risk of suicide. These findings provide new evidence for the profound impact of childhood adversity upon suicide vulnerability, thereby emphasizing the significance of early intervention and support to mitigate long-term effects of ACEs and promote well-being.

Results also revealed the relationship between ACEs and suicide risk was significantly mediated by IU. Specifically, we found that increased childhood adversity was associated with heightened IU, which was in turn associated with increased suicide risk. The present findings are reflective of prior literature on the role of IU in the development of various psychopathologies and adverse outcomes. Results are also consistent with the stress sensitization hypothesis, which suggests that exposure to prior stressors may increase vulnerability to adverse effects of subsequent stressors (Hammen et al., 2000). Previous exposure to adversity has been found to increase reactivity to subsequent stressors for some individuals. In the context of ACEs, which are often unpredictable and uncontrollable, repeated exposure during childhood may result in hypersensitivity to future stressors, resulting in a reduced ability to cope with uncertain situations and high IU. Difficulty tolerating uncertainty is associated with psychological distress and catastrophizing, which may contribute to increased negative affect and feelings of hopelessness (Deschênes et al., 2016; Shihata et al., 2016). Multiple studies suggest suicidal behavior functions as an avoidance-based response to negative emotions or situations. At least two prior studies have found situational escape and relief from negative emotions to be among the most frequently endorsed motives for attempting suicide (Bryan et al., 2013; May et al., 2020). IU may exacerbate the experience of emotional distress, and those with high IU may therefore turn to suicide as an immediate and predictable form of escape from uncertainty and negative affect that may continue indefinitely.

The relationship between these three factors highlights the importance of moving beyond addressing symptoms associated with suicidality and developing interventions that target mechanisms of suicide risk and behavior. Interventions that improve coping strategies for uncertainty may be particularly effective in reducing suicide risk among those with a history of ACEs. Laboratory-based research has found abnormal responses to uncertainty in those with suicidal ideation (e.g., Lieberman et al., 2020; Jollant et al., 2010), supporting the idea that IU may be a promising target for suicide prevention and intervention efforts. Moreover, at least two previous studies have directly tested the efficacy of therapeutic interventions with IU-focused components and found significant reductions in IU post-treatment (Hewitt et al., 2009; Shapiro et al., 2022). Targeting IU may also have broader implications for promoting mental health, given the status of IU as a risk factor for various psychiatric concerns, including anxiety disorders, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (Hayward et al., 2020).

The present study had numerous strengths, including a generally medically healthy sample, employment of well-validated measures, and a well-characterized sample. However, several limitations should be acknowledged. Firstly, the study focused on cumulative adversity without distinguishing between specific type of ACEs endorsed. There is growing recognition that adversity can be categorized into different domains, potentially leading to different psychiatric outcomes based on variations in neurobiological profiles (e.g., Jones et al., 2023; Kreutzer & Gorka, 2021; Mehra et al., 2022). It is therefore possible that the ACEs endorsed in this sample are disproportionately related to suicidality, and it may be important to differentiate based on type of adversity experienced. Secondly, a comprehensive list of ACEs has yet to be widely agreed upon. Our study may have assessed a different set of ACEs than previous studies, possibly limiting the generalizability of our results. Thirdly, our sample was primarily composed of Caucasian females. It is presently unclear whether sex influences IU development and maintenance, though previous research has shown biological sex may be related to how ACEs affect individuals across the lifespan (Gajos et al., 2022; Lee & Chen, 2017). Although we controlled for biological sex in our analyses, future studies should continue to investigate the extent to which biological sex influences the relationship between ACEs, IU, and suicide risk. It is also important to highlight the present data was collected in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, during a time marked by shifts in rates of IU and anxiety. It will be important to continue to examine the role of IU in mental health outcomes as the societal landscape changes. We also did not measure other factors that may impact IU and suicide risk such as current utilization of psychiatric services (though all participants were medication free). An important next step is to better understand the possible beneficial role that interventions may play in these associations.

In sum, the present findings indicate that IU is a potential pathway through which ACEs and suicide risk are related. Ultimately, these results converge with a broader literature on the relationship between childhood adversity and suicidality. Findings also extend previous literature to suggest IU as a mediator of this relationship and a viable suicide prevention target in those with a history of childhood adversity. By better understanding the underlying mechanisms of suicidal behavior, we can develop more effective interventions to prevent suicide and promote mental health, particularly those who have experienced childhood adversity.

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism [grant number R01AA028225] (principal investigator: S. M. Gorka).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Credit Authors Statement

SMG was the principal investigator of the study. EEJ helped develop the research question, interpreted the data, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. SMG led the primary analyses. CJB and NPA contributed to the development of the research question and assisted in data interpretation and manuscript preparation. All other authors contributed significantly to the discussion and revision of this work, including analysis, interpretation of results, proofreading, edits and approval for submission.

Declaration of Interests All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Allan NP, Gorka SM, Saulnier KG, & Bryan CJ (2023). Anxiety sensitivity and intolerance of uncertainty: Transdiagnostic risk factors for anxiety as targets to reduce risk of suicide. Current Psychiatry Reports, 25, 139–147. 10.1007/s11920-023-01413-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey RK, Patel TC, Avenido J, Patel M, Jaleel M, Barker NC, Khan JA, All S, & Jabeen S (2011) Suicide: Current Trends. Journal of the National Medical Association, 103(7), 614–617. 10.1016/S0027-9684(15)30388-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beautrais AL, Joyce PR, & Mulder RT (1996). Risk factors for serious suicide attempts among youths aged 13 through 24 years. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 35(9), 1174–1182. 10.1097/00004583-199609000-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilsen J (2018). Suicide and youth: Risk factors. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 540. 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostwick JM, Pabbati C, Geske JR, & McKean AJ (2016). Suicide attempt as a risk factor for completed suicide: Even more lethal than we knew. American Journal of Psychiatry, 173(11), 1094–1100. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.15070854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, Rudd MD, & Wertenberger E (2013). Reasons for suicide attempts in a clinical sample of active duty soldiers. Journal of Affective Disorders, 144(1–2), 148–152. 10.1016/j.jad.2012.06.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, Rudd MD, Wertenberger E, Etienne N, Ray-Sannerud BN, Morrow CE, Peterson AL, & Young-McCaughon S (2014). Improving the detection and prediction of suicidal behavior among military personnel by measuring suicidal beliefs: An evaluation of the Suicide Cognitions Scale. Journal of Affective Disorders, 159, 15–22. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jad.2014.02.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, May AM, Thomsen CJ, Allen MH, Cunningham CA, Wine MD, Taylor KB, Baker JC, Bryan AO, Harris JA, & Russell WA (2021). Psychometric evaluation of the Suicide Cognitions Scale – Revised (SCS-R). Military Psychology, 34(3), 269–279. 10.1080/08995605.2021.1897498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, Thomsen CJ, Bryan AO, Baker JC, May AM, & Allen MH (2022). Scores on the suicide cognitions scale-revised (SCS-R) predict future suicide attempts among primary care patients denying suicide ideation and prior attempts. Journal of Affective Disorders, 313, 21–26. 10.1016/j.jad.2022.06.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carleton RN (2016). Into the unknown: A review and synthesis of contemporary models involving uncertainty. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 39, 30–43. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carleton RN, Norton PJ, & Asmundson GJG (2007). Fearing the unknown: A short version of the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 21(1), 105–117. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). Suicide Data and Statistics. U. S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/suicide-data-statistics.html [Google Scholar]

- Curtin SC, Garnett MF, & Ahmad FB (2022). Provisional Numbers and Rates of Suicide by Month and Demographic Characteristics: United States, 2021. NVSS Vital Statistics Rapid Release; Report no. 24. 10.15620/cdc:120830 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deschênes SS, Dugas MJ, & Gouin J (2016). Intolerance of uncertainty, worry catastrophizing, and heart rate variability during worry-inducing tasks. Personality and Individual Differences, 90, 199–204. 10.1016/j.paid.2015.11.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Chapman DP, Williamson DF, & Giles WH (2001). Childhood abuse, household dysfunction, and the risk of attempted suicide throughout the life span: Findings from the adverse childhood experiences study. JAMA, 286(24), 3089–3096. 10.1001/jama.286.24.3089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Shattuck A, Turner H, & Hamby S (2015). A revised inventory of Adverse Childhood Experiences. Child Abuse & Neglect, 48, 13–21. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeston MH, Rhéaume J, Letarte H, Dugas MJ, & Ladouceur R (1994). Why do people worry? Personality and Individual Differences, 17(6), 791–802. 10.1016/0191-8869(94)90048-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller-Thomson E, Baird SL, Dhrodia R, & Brennenstuhl S (2016). The association between adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and suicide attempts in a population-based study. Child: Care, Health and Development, 42(5), 725–734. 10.1111/cch.12351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gajos JM, Leban L, Weymouth BB, & Cropsey KL (2022). Sex differences in the relationship between early adverse childhood experiences, delinquency, and substance use initiation in high-risk adolescents. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 38(1–2), 311–335. 10.1027/0269-8803/a000318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorka SM, Manzler CA, Jones EE, Smith RJ, & Bryan CJ (2023). Reward-related neural dysfunction in youth with a history of suicidal ideation: The importance of temporal predictability. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 158, 20–26. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2022.11.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greco V, & Roger D (2003). Uncertainty, stress, and health. Personality and Individual Differences, 34(6), 1057–1068. 10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00091-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grupe DW, & Nitschke JB (2013). Uncertainty and anticipation in anxiety: An integrated neurobiological and psychological perspective. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 14(7), 488–501. 10.1038/nrn3524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Henry R, & Daley SE (2000). Depression and sensitization to stressors among young women as a function of childhood adversity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(5), 782–787. 10.1037/0022-006X.68.5.782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawton K, Saunders KE, & O’Connor RC (2012). Self-harm and suicide in adolescents. The Lancet, 379(9834), 2373–2382. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60322-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt SN, Egan S, & Rees C (2009). Preliminary investigation of intolerance of uncertainty treatment for anxiety disorders. Clinical Psychologist, 13(2), 52–58. 10.1080/13284200802702056 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward LE, Vartanian LR, Kwok C, & Newby JM (2020). How might childhood adversity predict adult psychological distress? Applying the Identity Disruption Model to understanding depression and anxiety disorders. Journal of Affective Disorders, 265, 112–119. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.01.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jollant F, Lawrence NS, Olie E, O’Daly O, Malafosse A, Courtet P, &. Phillips ML (2010). Decreased activation of lateral orbitofrontal cortex during risky choices under uncertainty is associated with disadvantageous decision-making and suicidal behavior. NeuroImage, 51(3), 1275–1281. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.03.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones EE, Kreutzer KA, Manzler CA, Evans EG, & Gorka SM (2023). Type of trauma exposure impacts neural reactivity to errors. Journal of Psychophysiology. Advance online publication. 10.1027/0269-8803/a000318 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kleiman EM, & Nock MK (2018). Real-time assessment of suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Current Opinion in Psychology, 22, 33–37. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.07.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED, May AM, & Saffer BY (2016). Suicide, suicide attempts, and suicidal ideation. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 12(1), 307–330. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreutzer KA, & Gorka SM (2021). Impact of trauma type on startle reactivity to predictable and unpredictable threats. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 209(12), 899–904. 10.1097/NMD.0000000000001394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RD, & Chen J (2017). Adverse childhood experiences, mental health, and excessive alcohol use: Examination of race/ethnicity and sex differences. Child Abuse & Neglect, 69, 40–48. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman L, Petrey K, Shankman SA, Phan KL, & Gorka SM (2020). Heightened reactivity to uncertain threat as a neurobehavioral marker of suicidal ideation in individuals with depression and anxiety. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 155, 99–104. 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2020.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manyema M, Norris SA, & Richter LM (2018). Stress begets stress: The Association of Adverse Childhood Experiences with psychological distress in the presence of adult life stress. BMC Public Health, 18(1). 10.1186/s12889-018-5767-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May AM, Pachkowski MC, & Klonsky ED (2020). Motivations for suicide: Converging evidence from clinical and community samples. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 123, 171–177. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy PM, & Mahoney AEJ (2011). Achieving certainty about the structure of intolerance of uncertainty in a treatment-seeking sample with anxiety and depression. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 25(1), 112–122. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehra LM, Hajcak G, & Meyer A (2022). The relationship between stressful life events and the error-related negativity in children and adolescents. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 55, 101110. 10.1016/j.dcn.2022.101110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrick MT, Ports KA, Ford DC, Afifi TO, Gershoff ET, & Grogan-Kaylor A (2017). Unpacking the impact of adverse childhood experiences on adult mental health. Child Abuse & Neglect, 69, 10–19. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.03.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirman A, Bick AS, Kalla C, Canetti L, Segman R, Dan R, Ben Yehuda A, Levin N, & Bonne O (2020). The imprint of childhood adversity on emotional processing in high functioning young adults. Human Brain Mapping, 42(3), 615–625. 10.1002/hbm.25246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Green JG, Hwang I, McLaughlin KA, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, & Kessler RC (2013). Prevalence, correlates, and treatment of lifetime suicidal behavior among adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. JAMA Psychiatry, 70(3), 300–310. 10.1001/2013.jamapsychiatry.55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, & Hayes AF (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891. 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd MD, & Bryan CJ (2021). The Brief Suicide Cognitions Scale: Development and clinical application. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, Article 737393. 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.737393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro MO, Allan NP, Raines AM, & Schmidt NB (2022). A randomized control trial examining the initial efficacy of an intolerance of uncertainty focused psychoeducation intervention. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 45, 379–390. 10.1007/s10862-022-10002-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shihata S, McEvoy PM, Mullan BA, & Carleton RN (2016). Intolerance of uncertainty in emotional disorders: What uncertainties remain? Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 41, 115–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin SH, McDonald SE, & Conley D (2018). Profiles of Adverse Childhood Experiences and impulsivity. Child Abuse & Neglect, 85, 118–126. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.07.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang F, Byrne M, & Qin P (2018). Psychological distress and risk for suicidal behavior among university students in contemporary China. Journal of Affective Disorders, 228, 101–108. 10.1016/j.jad.2017.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson MP, Kingree JB, & Lamis D (2019). Associations of adverse childhood experiences and suicidal behaviors in adulthood in a U.S. nationally representative sample. Child: Care, Health and Development, 45(1), 121–128. 10.1111/cch.12617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Kolk BA, Perry JC, & Herman JL (1991). Childhood origins of self-destructive behavior. American journal of Psychiatry, 148(12), 1665–1671. 10.1176/ajp.148.12.1665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2019). Suicide in the world: Global health estimates. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/326948 [Google Scholar]

- Zouk H, Tousignant M, Seguin M, Lesage A, & Turecki G (2006). Characterization of impulsivity in suicide completers: Clinical, behavioral and Psychosocial Dimensions. Journal of Affective Disorders, 92(2–3), 195–204. 10.1016/j.jad.2006.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]