Abstract

Vitamin D3 metabolites block lipid biosynthesis by promoting degradation of the complex of sterol regulatory element-binding protein (SREBP) and SREBP cleavage-activating protein (SCAP) independent of their effects on the vitamin D receptor (VDR). We previously reported the development of KK-052, the first vitamin D-based SREBP inhibitor that mitigates hepatic lipid accumulation without VDR-mediated calcemic action in mice. Herein we extend our previous work to synthesize KK-052 analogues. Various substituents were introduced to the phenyl ring of KK-052, and two KK-052 analogues were found to exhibit more potent SREBP/SCAP inhibitory activity than KK-052, whereas they all lack VDR activity. These new KK-052 analogues may be suited for further development as VDR-silent SREBP/SCAP inhibitors.

Lack VDR activity and show potent SREBP/SCAP inhibitory activity.

Introduction

Vitamin D3 metabolites have various biological roles. The best-documented role of vitamin D3 is calcium homeostasis, cell differentiation, and immune responses through the stimulation of the vitamin D receptor (VDR).1–5 The most VDR active form of vitamin D3 is 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 [1α,25(OH)2D3], which is produced after two-step hydroxylation of vitamin D3 mainly through the liver, followed by the kidney. The binding of 1α,25(OH)2D3 to VDR promotes the transcription of VDR-responsive genes to exert such diverse biological activities. Several thousand vitamin D analogues have been synthesized, and eight synthetic vitamin D medicines have reached clinical use.6 Although they have a unique CD-ring side chain or a modified A-ring, the basic structure harbors three hydroxy groups at C1, C3, and C25 positions on a B-seco-steroidal scaffold, just like 1α,25(OH)2D3, to bind to the ligand binding domain (LBD) of VDR.7

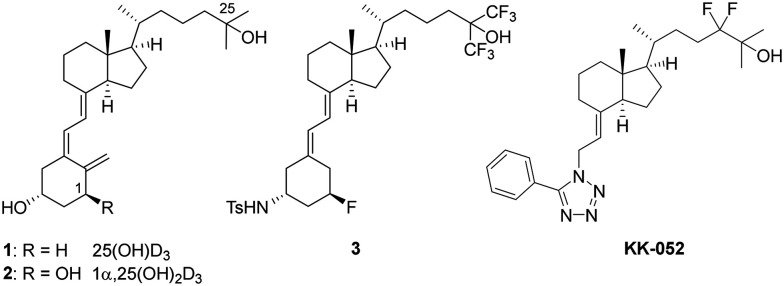

Our previous screening of endogenous molecules led to the identification of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 [25(OH)D3, 1, Fig. 1], 24,25(OH)2D3, and 1α,25(OH)2D3 (2) as inhibitors of sterol regulatory element-binding proteins (SREBPs),8 a family of transcription factors that regulate lipogenic genes.9–12 Mechanistic analyses suggested that vitamin D metabolites directly interact with SREBP cleavage-activating protein (SCAP), a specific escort protein of SREBPs, leading to the degradation of both SCAP and SREBP and consequent suppression of lipogenesis.8 Among the three vitamin D3 metabolites, 25(OH)D3 showed the highest SPREBP/SCAP degradation activity. This initial discovery suggested the 25(OH)D3-like structures as an unprecedented source of unique SREBP inhibitors. SREBP has now highly been regarded as a promising drug target for fatty liver diseases13 and cancers,14–16 which are characterized as having abnormal or increased lipid metabolism.17

Fig. 1. Structures of 25(OH)D3 (1), 1α,25(OH)2D3 (2), 1,3-bisfunctionalized 19-norvitamin D3 (3),19 and KK-052 (ref. 18) for SREBP/SCAP inhibition.

The utility of 25(OH)D3per se as an SREBP inhibitor in vivo is hampered by its VDR-mediated calcemic action, which is harmful above physiological concentrations.18 Synthetic vitamin D analogues selective for SREBP would provide a new set of SREBP inhibitors and represent a novel therapeutic application of vitamin D derivatives. Toward this goal, we previously reported the synthesis and biological evaluation of 25(OH)D3 analogues and found compound 3 and KK-052 as VDR-silent SREBP inhibitors (Fig. 1).18,19 Compound 3 selectively impaired SREBP/SCAP without eliciting VDR activity in cultured cells.19 However, the utility of 3in vivo was limited due to its residual calcemic activity at high doses and low bioavailability. KK-052 represents the first vitamin D-based SREBP inhibitor that has been demonstrated to mitigate hepatic lipid accumulation without calcemic action in mice. KK-052 maintained the ability of 25(OH)D3 to induce the degradation of SREBP and its escort protein SCAP but lacked in the VDR-mediated activity. KK-052 serves as a valuable compound for interrogating SREBP/SCAP in vivo and may represent an unprecedented translational opportunity of synthetic vitamin D analogues. In this study, we extend our previous efforts to synthesize KK-052 analogues with substituents on the phenyl ring at the o-, m-, and p-positions 7–14 (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. Synthetic route to new KK-052 analogues 7–14.

Results and discussion

Chemistry

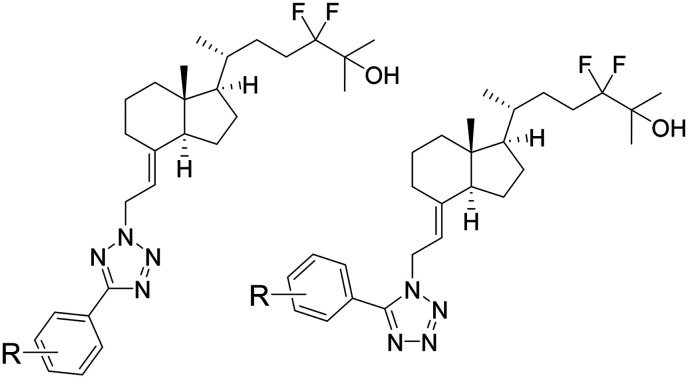

In Scheme 1, the synthetic route to KK-052 analogues is described.20 The starting material (4) was prepared by the reported procedure.21 Oxidation of the C8 hydroxy group followed by protection of the C25 tertiary hydroxyl group with a silyl group yielded 8-oxo-CD-ring (5). Next, we introduced the allyl alcohol unit to 5 using Horner–Emmons reaction with diethyl phosphonoacetate/NaH and subsequent DIBAL-H reduction to give 6. The key step for constructing the 5-phenyltetrazole units was achieved by the Mitsunobu reaction, and the consequent desilylation of the C25-hydroxy group resulted in the desired KK-052 analogues (7b–14b) along with their regioisomers (7a–14a).18 The structures of 7–14 are shown in Fig. 2–4.

Fig. 2. p-Substituted new KK-052 analogues.

Fig. 3. m-Substituted new KK-052 analogues.

Fig. 4. o-Substituted new KK-052 analogues.

VDR/SREBP activities in cultured cells

We examined the ability of the KK-052 analogues to stimulate VDR by using a VDR-responsive luciferase reporter.8,19 Although the p-substituted analogues 7–9 tend to show slight VDR activity, VDR-stimulating activities of the other analogues were much weaker than 25(OH)D3 (1) and as low as those of KK-052 or DMSO (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Effects of synthetic compounds 7–14 on VDR activation.18 All compounds showed negligible activity the same as the DMSO-negative control. CHO-K1 cells were transfected with the reporter gene in which the expression of luciferase was controlled by the vitamin D response element (VDRE), and treated with 5 μM of the compounds in a lipid-free medium. The same experiment using 25(OH)D3 (1) was performed as a control. Values are mean ± SD.

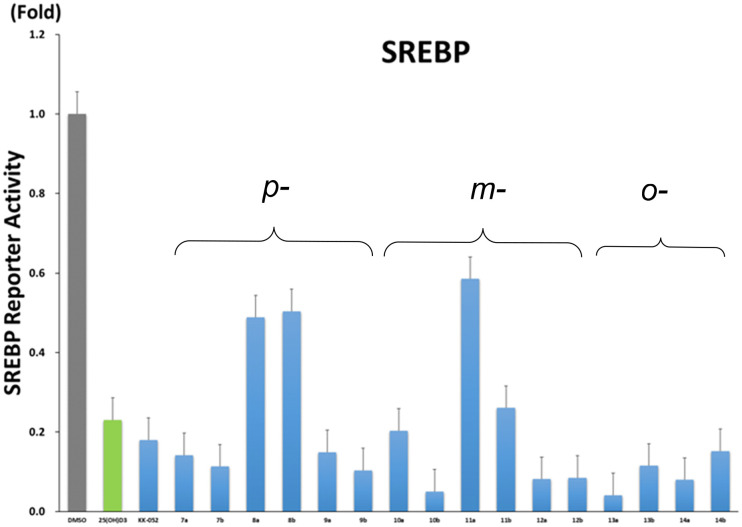

We next evaluated their ability to inhibit SREBP/SCAP by using a reporter gene in which the expression of luciferase was controlled by the sterol-responsive element (SRE). The analogues with bulky substituents (8 and 11) displayed weaker inhibitory activities than the others, consistent with a previous report.18 At the concentration of 5 μM, m-methyl analogue (10b) and o-chloro analogue (13a) showed more potent inhibitory activities than KK-052 and 1 (Fig. 6). To conduct a direct comparison between these two analogues and KK-052, we treated the reporter cells with varying concentrations of the compounds, including KK-052. As shown in Fig. 7, the IC50 values for 10b, 13a, and KK-052 were determined to be 1.4 μM, 2.0 μM, and 3.5 μM, respectively, indicating that 10b and 13a exhibit slightly greater potency than KK-052. Given that these two analogues are essentially devoid of VDR activity, 10b and 13a may be suited for further development as VDR-silent SREBP/SCAP inhibitors.

Fig. 6. Effects of synthetic compounds 7–14 on SREBP activation.18 All compounds except for a few (8a,b, 11a,b) showed strong inhibitory activity. CHO-K1 cells were transfected with the reporter gene in which the expression of luciferase was controlled by the sterol-responsive element (SRE) and treated with 5 μM of the compounds in a lipid-free medium. The same experiment using 25(OH)D3 (1) was performed as a control. Values are mean ± SD.

Fig. 7. Dose-dependent effects of KK-052 analogues on SREBP activation. CHO-K1 cells were transfected with the reporter gene in which the expression of luciferase was controlled by SRE and treated with various concentrations of the compounds in a lipid-free medium. Values are mean ± SD.

We also examined the effects of 10b and 13a on the protein levels of endogenous SCAP and exogenously expressed FLAG-SCAP in CHO-K1 cells. As shown in Fig. 8, western blot analyses indicated that both compounds led to a reduction in SCAP protein levels, similar to the effects of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 and KK-052. These results suggest that compounds 10b and 13a operate in a similar manner as 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 and KK-052.

Fig. 8. Effects of KK-052 analogues on the expression of endogenous SCAP (left panel) or overexpressed SCAP (right panel). Wild-type CHO-K1 cells or FLAG-SCAP (1–767)-overexpressing CHO-K1 cells were incubated in lipid-free medium containing 15 μM of each compound for 24 h. Immunoblots were performed with an anti-SCAP antibody or an anti-FLAG antibody.

Experimental

General procedure for synthesis of compounds 7–14: representative examples as 7a and 7b

To a solution of 5-(4-methylphenyl)-1H-tetrazole (29.5 mg, 0.184 mmol), Ph3P (52.7 mg, 0.201 mmol), and 24,24-difluoro-CD-ring (6)18 (42.4 mg, 0.092 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (3 mL) was added diisopropyl azodicarboxylate (88 μL, 1.9 M in toluene, 0.166 mmol) at 0 °C, and the mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 5 min and then at room temperature for 40 min. The mixture was evaporated in vacuo, and the residue was roughly purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel (hexane : EtOAc = 5 : 1–3 : 1) to obtain crude products (less polar and more polar products).

p-Toluenesulfonic acid monohydrate (109.6 mg, 0.576 mmol) was added to a solution of the above less polar crude product in MeOH (5 mL) and CH2Cl2 (2 mL). The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 h under air. p-Toluenesulfonic acid monohydrate (101.9 mg, 0.533 mmol) was added to the mixture and stirred at the same temperature for a further 30 min. After the reaction was quenched with H2O and saturated aqueous NaHCO3 at room temperature, the mixture was extracted with CH2Cl2 three times, dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated. The residue was purified on a preparative silica gel TLC plate (hexane : EtOAc = 3 : 1) to obtain 7a (13.5 mg, 30%) as a colorless oil.

7a

[α]27D + 35.9 (c 1.04, CHCl3); IR (neat) 3442, 1464, 1380, 1176, 1041, 1017, 830, 754 cm−1; 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.54 (s, 3H, H-18), 0.94 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 3H, H-21), 1.25–2.04 (m, 23H), 2.41 (s, 3H, p-CH3), 2.83–2.85 (m, 1H), 5.21–5.35 (m, 3H), 7.28 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 8.02 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 11.8, 18.6, 21.5, 22.0, 23.3, 23.6, 26.8, 27.4 (t, J = 24.4 Hz, C-23), 27.4, 29.1, 35.6, 40.1, 45.8, 50.1, 55.6, 56.1, 73.3 (t, J = 26.6 Hz, C-25), 111.8, 124.8, 125.5 (t, J = 246.3 Hz, C-24), 126.7, 129.5, 140.3, 147.7, 165.1 (tetrazole-C); HRMS (ESI+) calcd for C28H40N4OF2Na [M + Na]+ 509.3062, found 509.3075.

p-Toluenesulfonic acid monohydrate (203.6 mg, 1.07 mmol) was added to a solution of the above more polar crude product in MeOH (5 mL) and CH2Cl2 (2 mL). The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 70 min under air. After the reaction was quenched with H2O and saturated aqueous NaHCO3 at room temperature, the mixture was extracted with CH2Cl2 three times, dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated. The residue was purified on a preparative silica gel TLC plate (hexane : EtOAc = 1 : 1) to obtain 7b (12.7 mg, 28%) as a colorless oil.

7b

[α]27D + 41.3 (c 0.98, CHCl3); IR (neat) 3418, 1479, 1380, 1176, 1013, 826, 759 cm−1; 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.48 (s, 3H, H-18), 0.94 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H, H-21), 1.24–2.01 (m, 23H), 2.45 (s, 3H, p-CH3), 2.56–2.58 (m, 1H), 5.04–5.15 (m, 3H), 7.34 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 7.59 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 11.8, 18.6, 21.5, 22.1, 23.1, 23.6, 26.7, 27.3, 27.4 (t, J = 24.5 Hz, C-23), 28.9, 35.6, 40.0, 45.6, 45.6, 55.5, 56.1, 73.3 (t, J = 27.3 Hz, C-25), 113.1, 121.2, 125.4 (t, J = 245.6 Hz, C-24), 128.7, 129.8, 141.6, 146.2, 154.1 (tetrazole-C); HRMS (ESI+) calcd for C28H40N4OF2Na [M + Na]+ 509.3062, found 509.3079.

Western blot analysis

CHO-K1 cells were obtained from RIKEN BioResource Research Center. Cells were washed with cold PBS and lysed with RIPA buffer (Nacalai Tesque) containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Nacalai Tesque). The lysates were centrifuged at 20 000g for 15 min, and the protein concentration in each lysate was determined by a BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The lysates were mixed with 0.2 volume of 6 × SDS sample buffer (Nacalai Tesque) and incubated at room temperature for 1 h. The samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and blotted using specific antibodies. The specific bands were visualized using ImmunoStar Zeta (FUJIFILM) on an ImageQuant LAS4000 (GE Healthcare). Primary antibodies used for immunoblotting were as follows: mouse monoclonal anti-hamster-SCAP (IgG-9D5, Santa Cruz Biotechnology); mouse monoclonal anti-FLAG M2 (F1804, Sigma-Aldrich); mouse monoclonal anti-actin (IgG-AC-40, Abcam). The secondary antibody used for immunoblotting was anti-mouse IgG, HRP-linked antibody (Cell Signaling).

The other compounds 8a,b–14a,b were synthesized using the similar approach to 7a,b, and all synthetic procedures, compound characterization and spectra as well as luciferase reporter assay protocols are described in ESI† in detail.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we synthesized new KK-052 analogues 7–14 and evaluated their VDR activity and SREBP/SCAP inhibitory activity in cultured cells. The results revealed that m-methyl and o-chloro analogues (10b and 13a) lack VDR activity and show more potent SREBP/SCAP inhibitory activity than the other KK-052 analogues and 1. Further biological studies of these new analogues are in progress.

Author contributions

Design/conception of study: F. K., M. U., and A. K. Investigation: F. K., S. M., A. M., and Y. T. Original draft preparation: F. K. Writing – review and editing: A. K. and M. U. Supervision: A. K. and M. U. Funding acquisition: M. U. and A. K.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): M. U. has interests in FGH Biotech, Inc., a Houston-based company that exclusively licensed the technology described in this manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by AMED-CREST, The Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) with project No. JP15gm0710007h–JP19gm0710007h.

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available: Synthetic procedures, compound characterization and spectra. See DOI: https://doi.org/10.1039/d3md00352c

Notes and references

- Lori A. Plum L. A. DeLuca H. F. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2010;9:941–955. doi: 10.1038/nrd3318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veldurthy V. Wei R. Oz L. Dhawan P. Jeon Y. H. Christakos S. Bone Res. 2016;4:16041. doi: 10.1038/boneres.2016.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel S. Sitrin M. D. Nutr. Rev. 2008;66:S116–S124. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White J. H. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2012;13:21–29. doi: 10.1007/s11154-011-9195-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christakos S. Li S. De La Cruz J. Shroyer N. F. Criss Z. K. Verzi M. P. Fleet J. C. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2020;196:105501. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2019.105501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubodera N. Heterocycles. 2010;80:83–98. doi: 10.3987/REV-09-SR(S)3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rochel N. Wurtz J. M. Mitschler A. Klaholz B. Moras D. Mol. Cell. 2000;5:173–179. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80413-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asano L. Watanabe M. Ryoden Y. Usuda K. Yamaguchi T. Khambu B. Takashima M. Sato S. Sakai J. Nagasawa K. Uesugi M. Cell Chem. Biol. 2017;24:207–217. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2016.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown M. S. Goldstein J. L. Cell. 1997;89:331–340. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80213-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein J. L. DeBose-Boyd R. A. Brown M. S. Cell. 2006;124:35–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamisuki S. Mao Q. Abu-Elheiga L. Gu Z. Kugimiya A. Kwon Y. Shinohara T. Kawazoe Y. Sato S. Asakura K. Choo H.-Y. P. Sakai J. Wakil S. J. Uesugi M. Chem. Biol. 2009;16:882–892. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamisuki S. Shirakawa T. Kugimiya A. Abu-Elheiga L. Choo H.-Y. P. Yamada K. Shimogawa H. Wakil S. J. Uesugi M. J. Med. Chem. 2011;54:4923–4927. doi: 10.1021/jm200304y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimano H. Sato R. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2017;13:710–730. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2017.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Röhrig F. Schulze A. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2016;16:732–749. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin X. Demere Z. Nair K. Ali A. Ferraro G. B. Natoli T. Deik A. Petronio L. Tang A. A. Zhu C. Wang L. Rosenberg D. Mangena V. Roth J. Chung K. Jain R. K. Clish C. B. Vander Heiden M. G. Golub T. R. Nature. 2020;588:331–336. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2969-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M. Zhang J. Sampieri K. Clohessy J. G. Mendez L. Gonzalez-Billalabeitia E. Liu X.-S. Lee Y.-R. Fung J. Katon J. M. Menon A. V. Webster K. A. Ng C. Palumbieri M. D. Diolombi M. S. Breitkopf S. B. Teruya-Feldstein J. Signoretti S. Bronson R. T. Asara J. M. Castillo-Martin M. Cordon-Cardo C. Pandolfi P. P. Nat. Genet. 2018;50:206–218. doi: 10.1038/s41588-017-0027-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freed-Pastor W. A. Mizuno H. Zhao X. Langerød A. Moon S.-H. Rodriguez-Barrueco R. Barsotti A. Chicas A. Li W. Polotskaia A. Bissell M. J. Osborne T. F. Tian B. Lowe S. W. Silva J. M. Børresen-Dale A.-L. Levine A. J. Bargonetti J. Prives C. Cell. 2012;148:244–258. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawagoe F. Mendoza A. Hayata Y. Asano L. Kotake K. Mototani S. Kawamura S. Kurosaki S. Akagi Y. Takemoto Y. Nagasawa K. Nakagawa H. Uesugi M. Kittaka A. J. Med. Chem. 2021;64:5689–5709. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c02179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata A. Akagi Y. Asano L. Kotake K. Kawagoe F. Mendoza A. Masoud S. S. Usuda K. Yasui K. Takemoto Y. Kittaka A. Nagasawa K. Uesugi M. ACS Chem. Biol. 2019;14:2851–2858. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.9b00718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono K. Yoshida A. Saito N. Fujishima T. Honzawa S. Suhara Y. Kishimoto S. Sugiura T. Waku K. Takayama H. Kittaka A. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:7407–7415. doi: 10.1021/jo034787y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawagoe F. Mototani S. Yasuda K. Nagasawa K. Uesugi M. Sakaki T. Kittaka A. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2019;195:105477. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2019.105477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.