Abstract

Citrus medica is a horticultural crop grown in different parts of the world. The plant leaves have medicinal importance in traditional medicine for the treatment of various diseases. The leaves are an underutilised part of the plant, despite having various bioactive compounds with health benefits, with phytochemical analysis having revealed the presence of flavonoids, fatty acids, alkaloids, terpenoids, glycosides, carbohydrates and phytosterols. The biochemical constituents were identified using Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) and gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS), which confirmed the presence of terpenoids, alcohols, alkanes, phytosterols and fatty acids. Among these, methyl 8, 11, 14-heptadecatrienoate is a linolenic acid, and α-linolenic acid, trimethylsilyl ester and levulinic acid are the predominant compounds belonging to the omega-3 fatty acid group, which has known health benefits. Further, the antimicrobial activity of C. medica plant leaves were tested against certain food-borne pathogens and showed significant results. The minimum inhibitory concentrations ranged from 6.09 mg/mL to 390 mg/mL for bacterial organisms and 48.75 mg/mL to 390 mg/mL for fungal organisms. The antioxidant activity values were 300 μg/mL and 450 μg/mL by 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) and 3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid (ABTS) assay, respectively. The methanolic extract from the C. medica leaves also showed anticancer activity against MCF7 breast cancer cell lines, with an IC50 value of material for developing a healthy processed food such as nutraceuticals and functional foods.

Keywords: Antifungal, Antimicrobial, Antioxidant Activity, Flavonoids, Omega-3 Fatty Acids

Highlights.

Antimicrobial activity of the Citrus medica leaves extract was tested against Staphylococcus aureus and Candida albicans was analysed through SEM. The extract is a rich source of bioactive compounds showed good antimicrobial, antioxidant and anticancer activity.

The GC-MS analysis of leaf extract of Citrus medica revealed the presence of omega fatty acids which are considered to be as important as food supplements for boosting the immunity and also scavenging of free radicals.

The active principles such as methyl 8, 11, 14-hepta decatrienoate which is a linolenic acid, α-linolenic acid trimethyl silyl ester and levulinic acid are the predominant compounds belongs to omega-3 fatty acids group with health benefits can be used in various food products that results in health benefits.

INTRODUCTION

Increased consumption of processed foods and exposure to stress have both been linked to the increased prevalence of several chronic diseases (Shridhar et al. 2015; Khan et al. 2010). Further, the human body harbours microorganisms that can cause disease (Caputo et al. 2018). Risk of these diseases can be reduced by consumption of natural ingredients such as fruits, leaves and vegetables that contain biochemical constituents, mineral components, dietary fibers and vitamins (Rafiq et al. 2018; Kausar et al. 2019). Natural foods available in the nature are functional to some extent (Varzakas et al. 2016). However, some foods are now being examined for its health benefits to reduce the risk of chronic diseases (Alissa & Ferns 2012). The biochemical constituents have the ability to treat various ailments such as cardiovascular diseases, cancer, gastrointestinal disorders and physiological functions like lowering triglycerides and glucose control in blood (Asif 2011; Eilat-Adar et al. 2013; McClements & Xiao 2017; Eswaraiah et al. 2020).

Synthetic drugs used to treat these diseases can also affect healthy cells and cause adverse side effects (Karimi et al. 2015; Madigan & Karhu 2018). An alternative to these synthetic drugs is natural foods such as fruit and vegetables, which are natural sources of dietary fiber, vitamins and minerals (Bhaskarachary 2016). Compared with synthetic drugs, many fruits and vegetables deliver enhanced health benefits that exceed their nutritional value, termed functional foods, with biologically active substances such as antioxidants (Abuajah et al. 2015). Earlier studies also proved the relationship between functional ingredients of the food and health of wellbeing. The biochemical constituents of some functional foods positively impact health by reducing the risk of chronic diseases providing treatments for medical conditions such as cancer, cardiovascular disease and gastrointestinal disorders (Keservani et al. 2010; Das et al. 2012).

Developing functional foods which are supplements with added ingredients is currently a research priority in the developing world (Keservani et al. 2010). The natural food ingredients with antibacterial, antioxidant and anticancer properties have more importance in food processing industries (Cirmi et al. 2017; Adnan, Bibi, et al. 2014; Eswaraiah et al. 2019). Citrus plants have rich of bioactive molecules extracted from various parts of the plant used to treat a range of medical disorders (Lv et al. 2015; Chaudhari et al. 2016). Citrus medica plant extract has been used to treat arthritis, asthma, headaches, abdominal pain, intestinal parasites and psychological problems (Panara et al. 2012). C. medica leaves are rich in essential oils have huge demand in market and also the usage of these compounds increasing day by day. The C. medica plant is widely used in Chinese traditional medicine (Aliyah et al. 2017). This current study investigated the antimicrobial, antioxidant and anticancer properties of C. medica leaf extract. The antimicrobial property was tested against food borne pathogens, biochemical constituents by GC-MS analysis, antioxidant activity using DPPH and ABTS assay and anticancer activity against MCF7 breast cancer cell line.

METHODS

Collection of Plant Sample

The leaves of Citrus medica (Citron-Dabbakaya), plant was collected from agricultural fields, Vijayawada, Krishna (Dt), Andhra Pradesh, India. Fresh leaves are collected during the winter season in the month of January 2018. The collected leaf samples were packed in plastic bags and transported to Biotechnology laboratory, Vignan’s Foundation for Science Technology and research for further work.

Sample Preparation and Extraction of The Phytochemicals

Leaf samples were washed with sterile water to remove dust and foreign particles. The leaves were dried at 40°C in a hot-air oven for 3 days and then powdered. The Soxhlet extraction method was employed to extract the phytochemicals, using 100 g of powdered sample and 200 mL of methanol solvent at 12h intervals over three successive days at 65°C. For every hour, 3 cycles were run to extract the maximum number of compounds. After extraction, the methanol solvent was evaporated using a rotary evaporator under reduced pressure at 25°C for 1 h. The crude extract became a semi-solid mass and this was stored in Falcon tubes prior to further study (Adnan, Umer, et al. 2014).

Phytochemical Screening of Citrus Leaves Extracts

The crude extract was tested for presence of phytochemicals such as alkaloids, glycosides, saponins, phenolic compounds, steroids, flavonoids, tannins, anthraquinones, amino acids, carbohydrates, terpenoids and phytosterols in the leaf sample (Ali et al. 2018).

Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

The functional groups of phytochemical compounds in the crude extract were identified using Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) performed on a SHIMADZU FTIR–8400S. The crude extract 10 mg is mixed with 100 mg of KBr salt and compressed into thin pellet using mortar and pestle. The sample is loaded into spectroscope and the results were recorded at frequencies of 500 cm−1 to 4,000 cm−1 (Ashok Kumar & Ramaswamy 2014).

Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry

The phytochemical constituents in the crude extract were identified using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis, performed on Agilent© 7890A-5975C equipment (Agilent Technologies, USA) using an HP 5 MS capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm). The injection port conditions were: sample injected = 1 μL; carrier gas = helium with a flow rate of 1.2 mL/min; and temperature = 250°C. The GC column temperature was programmed initially at 80°C for 1 min, then the temperature was increased to 200°C at a rate of 15°C/min, further increased to 300°C at a rate of 5°C, and then maintained at 300°C for 5 min. The MS conditions were: temperature of the ion source = 230°C; ionisation energy = 70 eV; and a scan range of 50 amu–800 amu. The sample is prepared using methanol solvent and filtered. 50 μL of the sample is taken in 1.5 mL of autosampler and loaded into the injector port. The separated biochemical constituents were compared with the mass spectra in the NIST library (Rahman et al. 2019).

Antimicrobial Activity Assay

Selection of indicator organisms and culture media

The antimicrobial activity of the leaf extract was performed by selecting the food borne pathogens such as bacteria and fungi. For antibacterial assay, indicator organisms are Staphylococcus aureus (MTCC 3103), Escherichia coli (MTCC 9537), Enterobacter aerogenes (MTCC 8558), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (MTCC 10306), Klebsiella pneumoniae (MTCC 10309), Salmonella typhi (MTCC 3224), Shigella flexneri (MTCC 9543), and Bacillus subtilis (MTCC 1305) were collected from Microbial Type Culture Collection (MTCC), Chandigarh, India. Nutrient agar medium and Muller Hinton agar medium was used for maintenance of cultures and antimicrobial activity, respectively. For antifungal assay, fungal cultures are Fusarium oxysporum (NCIM 1043), Aspergillus niger (NCIM 512), Penicillium citrinum (NCIM 766), Trichoderma viridae (NCIM 1051), and Candida albicans (NCIM 3471) were collected from National Collection of Industrial Microorganisms (NCIM), Pune, India.

Agar Well Diffusion and Disk Diffusion Assay for Antimicrobial Activity

The selected indicator organisms were grown in a nutrient-broth medium and seeded for assay. Muller–Hinton agar plates (100 mm × 15 mm size) were prepared with 25 mL of medium and the inocula were seeded on the agar surface using the spread plate method. After lawn preparation, 4-mm-deep wells were created and loaded with 100 μL (1.6 × 108 CFU/mL) of crude citrus-leaf extract (methanol) before the plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 h. The zone of inhibition was then measured and compared to both the positive control––ampicillin antibiotic––and the negative control––dimethyl sulfoxide (Sah et al. 2011). The selected fungal indicator organisms were grown in a Potato Dextrose Broth medium for 5 days to 7 days at 28°C–30°C. Muller–Hinton agar plates were prepared and seeded with inocula using a sterile swab dipped in culture suspension. The inoculated plates were then dried before applying the disks. Sterile disks were placed in 10 μL of crude leaf extract for 30 min and were then placed on the surface of the agar and incubated at 28°C for 5 days. The zone of inhibition was measured and compared to the positive control––fluconazole antibiotic––and the negative control––dimethyl sulfoxide. The procedure was repeated for three replicates and the mean values are calculated (Agarwal et al. 2015).

Determination of Minimum Inhibitory Concentration

First, 10-mL measures of Mueller–Hinton broth medium were sterilised by autoclaving before being cooled and inoculated with 100 μL (1.6 × 108 CFU/mL) of microbial cell suspension and 100 μL of plant extract (methanol) of known concentration. The concentrations of crude leaf extract used in this experiment were 0.76, 1.52, 3.05, 6.09, 12.18, 24.38, 48.75, 97.50, 195.00 and 390.00 mg/mL. The contents of the test tubes were mixed well and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. The procedure was repeated for three replicates and the mean values are calculated. The lowest concentration of crude leaf extract to inhibit the growth of microorganisms was calculated according to the method of Mummed et al. (2018), with some modifications.

Antagonistic Activity Against Staphylococcus aureus and Candida albicans

The selected indicator organisms S. aureus and C. albicans were grown in nutrient broth and Sabouraud dextrose broth respectively at 35°C for 8 h (Li et al. 2019). After 8 h of incubation, the cells were separated by centrifugation at 5,000 rpm and suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer with a pH of 7.4. The suspension (108 CFU/mL) was mixed with leaf extract and incubated for 4 h. The cells were separated by centrifugation and washed with PBS buffer, then fixed with glutaraldehyde (2.5%) and stored at 4°C for 30 min. A 50% to 100% graded series of ethanol was used to dehydrate the sample for 15 min per concentration before the cells were imaged using an S-3700N scanning electron microscope (SEM, Hitachi, Hitachi City, Japan).

Antioxidant Activity Assay

DPPH assay

The antioxidant potential of the C. medica leaf extract was measured by 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) assay––a protocol suitable for the determination. Various concentrations of extract were prepared, in test tubes, ranging from 100 μg/mL to 1,000 μg/mL made up to a volume of 3 mL using 70% methanol. A 1-mL aliquot of 100-μM DPPH solution was added to each test tube, the mixture then shaken vigorously and incubated for 30 min. the absorbance was measured at 517 nm. Ascorbic acid was used as the control. All tests were performed in triplicate. The radical-scavenging activity was expressed as the inhibition percentage and was calculated using a standard formula. The antioxidant activity was also expressed as an IC50 value (Sonboli et al. 2010).

ABTS assay

The antioxidant activity of C. medica leaf extract was measured by 2,2’-azinobis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid (ABTS) assay. The reaction (1:1 v/v) was prepared via the oxidation of ABTS and potassium persulfate, with reaction allowed for 16 h under dark conditions. The mixture was then diluted with methanol until it achieved absorbance values of 1.0–1.5 at 734 nm. The leaf extract (0.1 mL) was mixed with 3.9 mL of ABTS solution and allowed to react for 2 h under dark conditions before the absorbance values were measured at 734 nm using a spectrophotometer. The results were expressed as a percentage of inhibition using the equation described for the DPPH method (Shah & Mehta 2018).

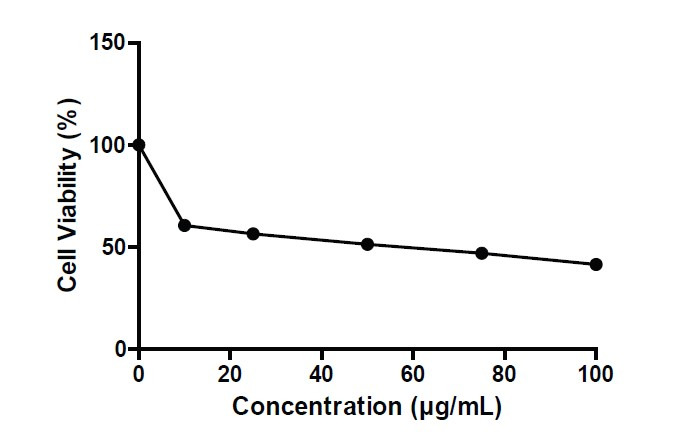

Antiproliferative Activity of Citrus medica

A recognised MCF-7 breast cancer cell line was procured from the National Centre for Cell Science, Pune, India. Using RPMI-1640 medium, the cancer cells were sub-cultured in culture flasks and passaged every three days. The cells were then seeded in 24 well plates for 3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazolyl-2)-2, 5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. A series of crude leaf extract concentrations, ranging from 0 to 100 μg/mL, was prepared. First, the cells were trypsinzed and treated with trypan blue. Using a hemocytometer, the cells were counted and seeded at a density of 5.0 × 103 cells/well in 96 well plates, then incubated at 37°C overnight. The medium was then replaced with fresh medium and 100 μL of different concentrations of crude leaf extract were added. The cells were incubated for 48 h, after which fresh medium and MTT solution (0.5 mg/mL) were added to each well. The cells were then incubated for a further 3 h, after which the absorbance values were measured at 570 nm using a microplate reader. The percentage growth inhibition and corresponding IC50 values were generated from the dose-response curve using Origin software (Stockert et al. 2018).

RESULTS

Phytochemical Screening

During the present study, the phytochemical constituents were identified by performing various tests and found the presence of alkaloids, glycosides, flavonoids, steroids, terpenoids, carbohydrates and phenolic compounds (Table 1). There is an absence of saponins, anthraquinones and tannins.

Table 1.

Phytochemical analysis of methanolic extract of C. medica.

| Sample no. | Phytochemical | Inference |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alkaloids | + |

| 2 | Glycosides | + |

| 3 | Saponins | − |

| 4 | Steroids | + |

| 5 | Flavonoids | + |

| 6 | Tannins | − |

| 7 | Anthraquinones | − |

| 8 | Carbohydrates | + |

| 9 | Phenolics | + |

| 10 | Terpenoids | + |

| 11 | Phytosterols | + |

Notes: + indicates Present; – indicates Absent

FTIR and GC–MS

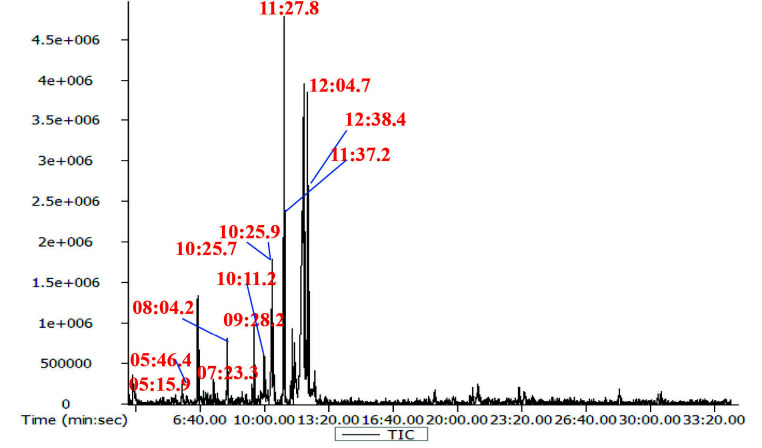

The FTIR analysis revealed the presence of various functional groups and biochemical classes of compounds in the leaf extract (Table 2). Fig. 1 presents the GC–MS spectra, showing various peaks representing different bioactive compounds.

Table 2.

FTIR analysis of phytoconstituents of methanol leaf extract of C. medica.

| Wave number (cm−1) | Possible bonds | Intensity |

|---|---|---|

| 503.44, 549.73, 569.02, 582.52, | C-I stretching and C-Br stretching | Strong |

| 669.32, 704.04, | C-Cl stretching, C=C bending | Strong |

| 1026.16, 1141.90, | C=O stretch | Strong |

| 1271.13, 1315.50, 1336.71 | C-N stretch | Medium-weak |

| 1408.08, 1433.16, 1518.03, 1579.75 | C=C stretch | Medium-weak |

| 1639.55 | N-H bending | Medium |

| 1872.94, 1911.52,1988.68 | C-H bending | Weak |

| 2065.83, 2090.91, | N=C=S stretching | Strong |

| 2162.27 | S-C=N stretch | Strong |

| 2224.00 | C=N stretch | Weak |

| 2266.43 | N=C=O stretch | Strong |

| 2526.83,2596.27,2708.15, 2854.74, 2916.47, 3001.34 | O-H stretching | Strong |

| 3419.9, 3444.98 | N-H stretch | Medium |

Figure 1.

GC–MS analysis of C. medica leaves.

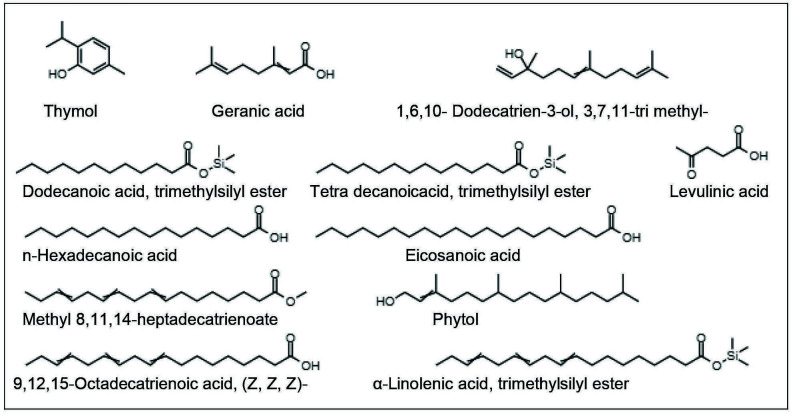

The compounds were identified from the methanolic extract of the C. medica leaves, as indicated in Table 3 and Fig. 2.

Table 3.

GC-MS analysis for leaf extract of C. medica.

| Sample no. | Name | Formula | RT | (RI) | (SI) | NIST-RI | CAS number | Integrated peak area | Exact mass |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Thymol | C10H14O | 05:15.9 | 1195.3 | 929 | 1266 | 89-83-8 | 170323 | 150.1045 |

| 2 | Geranic acid | C10H16O2 | 05:46.4 | 1253.3 | 949 | 1342 | 459-80-3 | 3879701 | 168.115 |

| 3 | 1,6,10-dodecatrien-3-ol,3,7,11-tri methyl- | C15H26O | 07:23.3 | 1445.8 | 960 | 1545 | 40716-66-3 | 5746258 | 222.1984 |

| 4 | Dodecanoic acid, trimethylsilylester | C15H32O2Si | 08:04.2 | 1532.7 | 839 | 1590 | 55520-95-1 | 1234539 | 272.2172 |

| 5 | Tetradecanoic acid, trimethylsilylester | C17H36O2Si | 09:28.2 | 1722.5 | 948 | 1840 | 18603-17-3 | 11499156 | 300.2485 |

| 6 | Levulinic acid | C5H8O3 | 10:11.2 | 1817.6 | 999 | 1823 | 123-76-2 | 3355465 | 116.0473 |

| 7 | n-hexadecanoic acid | C16H32O2 | 10:25.7 | 1847.3 | 865 | 1964 | 57-10-3 | 72544533 | 256.2402 |

| 8 | Eicosanoic acid | C20H40O2 | 10:25.9 | 1847.7 | 828 | 2359 | 506-30-9 | 72437943 | 312.3028 |

| 9 | Methyl 8,11,14-heptadecatrienoate | C18H30O2 | 11:27.8 | 1966.9 | 865 | 2002 | 155273-05-5 | 17068620 | 278.2246 |

| 10 | Phytol | C20H40O | 11:37.2 | 1984.2 | 888 | 2045 | 150-86-7 | 4333265 | 296.3079 |

| 11 | 9,12,15-octadecatrienoic acid, (Z, Z, Z)- | C18H30O2 | 12:04.7 | 2031.3 | 946 | 2073 | 463-40-1 | 296511194 | 278.2246 |

| 12 | α-linolenic acid, trimethylsilyl ester | C21H38O2Si | 12:38.4 | 2087.1 | 768 | 2191 | 97844-13-8 | 15316759 | 350.2641 |

Notes: RT = Retention time; RI = Retention index; SI = Similarity index

Figure 2.

Structures of compounds identified by GC-MS analysis.

Antimicrobial Activity

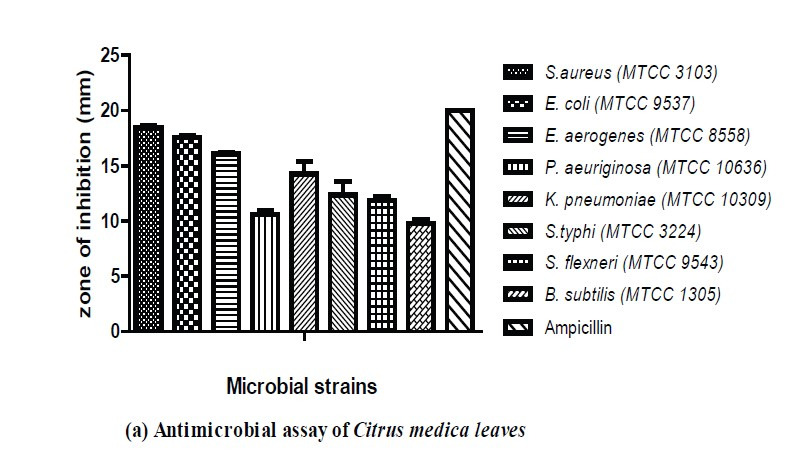

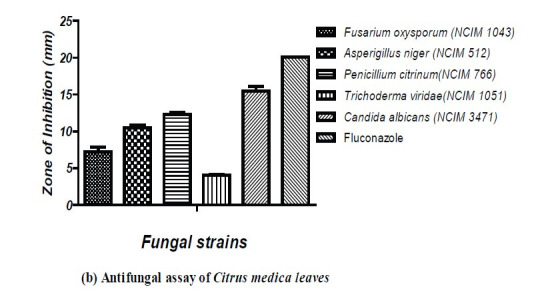

The antimicrobial activity of the methanolic extract was tested against selected indicator organisms, with the results provided in Figs. 3a and 3b. These show that the highest antimicrobial activity was observed for the strain Staphylococcus aureus (18.46 ± 0.04 mm), followed by Escherichia coli (17.53 ± 0.06 mm), Enterobacter aerogenes (16.06 ± 0.06 mm), and Klebsiella pneumonia (14.26 ± 1.6 mm). Moderate inhibition was observed for the strains Salmonella typhi (12.36 ± 2.0 mm), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (10.6 ± 0.9 mm), Shigella flexneri (11.9 ± 0.06 mm), and Bacillus subtilis (9.8 ± 0.06 mm). The results were compared with the ampicillin control. From the antifungal assay, it was found that Candida albicans (15.46 ± 1.2 mm) is very sensitive to the C. medica extract, followed by Penicillium citrinum (12.3 ± 0.09 mm), Aspergillus niger (10.46 ± 1.0 mm), and Fusarium oxysporum (7.26 ± 1.2 mm). The strain Trichoderma viride (4.06 ± 0.04 mm) was less sensitive to the extract compared with the standard drug fluconazole. All the results are written as mean of three individual observations ± SD.

Figure 3.

(a) Antimicrobial activity of C. medica leaf extract; (b) Antifungal activity of C. medica leaf extract.

Minimum Inhibitory Concentration

The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of C. medica leaf extract was determined and the values found to range from 6.09 mg/mL to 390 mg/mL. High antibacterial activity was observed for the MIC value of 6.09 mg/mL against E. coli, S. aureus and E…aerogenes. For the fungal cultures, considerable antibacterial activity was observed at a MIC value of 48.75 mg/mL against C. albicans (Table 4).

Table 4.

MIC values of C. medica leaf extract versus selected indicator organisms.

| Sample no. | Indicator organism | MIC concentration (mg/mL) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Staphylococcus aureus | 6.09 ± 0.00 |

| 2 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 195 ± 0.00 |

| 3 | Enterobacter aerogenes | 6.09 ± 0.00 |

| 4 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | 12.18 ± 0.00 |

| 5 | Escherichia coli | 6.09 ± 0.00 |

| 6 | Salmonella typhi | 48.75 ± 0.00 |

| 7 | Shigella flexneri | 48.75 ± 0.00 |

| 8 | Bacillus subtilis | 390 ± 0.00 |

| 9 | Fusarium oxysporum | 390 ± 0.00 |

| 6 | Aspergillus niger | 195 ± 0.00 |

| 7 | Penicillium citrinum | 97.5 ± 0.00 |

| 8 | Trichoderma viride | 390 ± 0.00 |

| 9 | Candida albicans | 48.75 ± 0.00 |

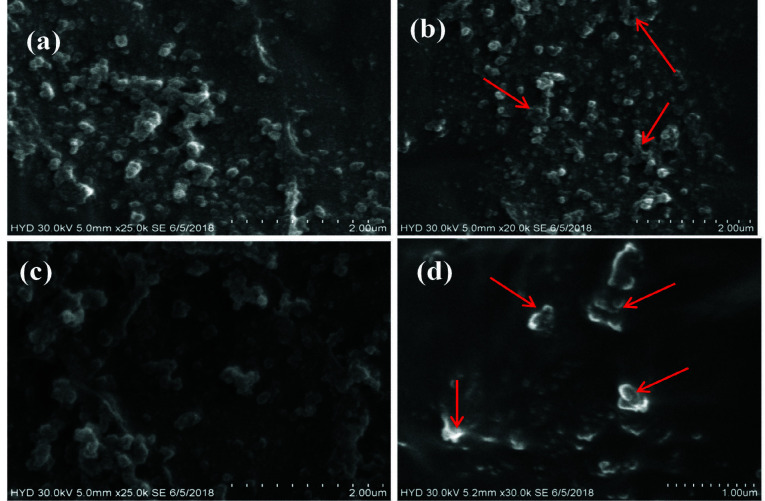

Antagonistic Activity Against S. aureus and C. albicans

Antagonistic activity was evaluated against the food-borne pathogens S. aureus and C. albicans. The effect of C. medica leaf extract on the cell morphology of S. aureus and C. albicans was investigated using a scanning electron microscope (at 50,000× magnification) by comparing the morphological features of both treated and untreated cells. Untreated S. aureus cells presented as aggregations of rounded cells (Fig. 4a), whereas the treated cells varied in size and shape and demonstrated some cell shrinkage (Fig. 4b). The untreated cells of C. albicans were characterised by their regular round or oval shapes Fig. 4c), whereas the treated cells were characterised by ruptured hyphae and cell membranes (Fig. 4d).

Figure 4.

Antagonistic activity of Citrus medica leaf extract on S. aureus and C. albicans. (a) Untreated cells of S. aureus; (b) Treated cells of S. aureus; (c) Untreated cells of C. albicans; and (d) Treated cells of C. albicans.

Antioxidant Activity Assay

The methanolic extract of C. medica demonstrated strong antioxidant activity by reducing the formation of DPPH radicals by 50% at an IC50 value of 300 μg. The mean IC50 value of ascorbic acid was found to be 50 μg. In the case of the ABTS assay, the free-radical ABTS inhibition by methanolic extract was found to be 450 μg (Table 5).

Table 5.

IC50 values for C. medica leaf extract (antioxidant assay).

| Sample no. | Extract type | IC50 value(μg) | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| DPPH radical assay | ABTS radical assay | ||

| 1 | Methanolic extract | 300 | 450 |

| 2 | Ascorbic acid | 50 | 60 |

The methanolic extract of C. medica plant leaves was evaluated for its antiproliferative activity against the MCF7 breast cancer cell line by MTT assay. An inhibition of viable MCF7 cells counted after treatment with the extract was observed. The results revealed that the cell line viability was decreased gradually with an increase in sample concentration. The maximum reduction in cells was found at a concentration of 100 μg/mL, with the viability being 41.473%. The IC50 value was 60.044 μg/mL at 48 h on the MCF7 cell line (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Cytotoxic activity of methanolic extract of C. medica plant leaves against MCF7 cell lines.

DISCUSSION

Citrus leaves are rich in various biochemical compounds particularly phenolic compounds and flavonoids (Khettal et al. 2017). The phytochemicals screened in the citrus leaf extract are alkaloids, flavonoids, carbohydrates, glycosides, terpenoids and phenolic compounds. In recent study by Chhikara et al. (2018) also reported the presence of alkaloids, glycosides, flavonoids and steroids in the leaves of C. medica. In another study by Patil (2017) reported the presence of alkaloids, steroids, glycosides and phenols in the citrus plant. The FTIR analysis study revealed the presence of functional groups such as halogen compounds (C-I, C-Br and C-Cl stretching), primary and secondary alcohols (C=O stretch), aromatic amine (C-N stretch), aromatic compounds (C=C stretch, C-H bending), amines (N-H bending and N-H stretch), thiocyanate (S-C=N stretch), isothiocyanate (N=C=S stretching), isocyanate (N=C=O stretch), nitrile compounds (C=N stretch) and carboxylic acids (O-H stretching) represented in Table 2. In previous study, Onyeyirichi et al. (2014) reported that the Citrus medica Limonium leaf essential oil consists of alcohols, amines, alkyl halides and alkanes.

Further, the GC-MS analysis showed 12 major peaks (Fig. 1) and the details of compounds are shown in Table 3. The major peak compounds are methyl 8,11,14-heptadecatrienoate, 9,12,15-octadecatrienoic acid, (Z, Z, Z)-, α-linolenic acid trimethylsilyl ester and phytol. The compounds with biological activity identified are thymol (antioxidant), geranic acid (pheromone and antiseptic material), dodecanoic acid, trimethylsilyl ester (surfactant) n-hexa decanoic acid (anti-inflammatory) (Nagoor et al. 2017; Greene et al. 2019; Qiao & Qiao 2013; Aparna et al. 2012). The compound 1, 6, 10-dodecatrien-3-ol, 3, 7, 11-tri methylis also known as nerolidol which is a flavour enhancer and levulinic acid is an additive (Chan et al. 2016; Zhou et al. 2020). The other compound is eicosanoic acid (Arachidonic acid), which is a saturated fatty acid (omega-6-fatty acid) and starting material for synthesis of prostaglandins (Powell & Rokach 2015). Apart from these, the abundant compounds with application in food industry are phytol, methyl 8, 11, 14-hepta decatrienoate, 9,12,15-octadeca trienoic acid, (Z, Z, Z)- and α-linolenic acid, trimethylsilyl ester. Phytol is a precursor for synthesis of vitamin E and Vitamin K (Byju et al. 2017). Methyl 8, 11, 14-hepta decatrienoate and 9,12,15-Octadeca trienoic acid, (Z, Z, Z)- both are having same molecular formula (C18H30O2) called as linolenic acid. The linolenic acid and α-linolenic acid, trimethyl silyl ester are the essential omega 3- fatty acids group highly concentrated in plant oils (Blondeau et al. 2015). The linolenic acid and alpha linolenic acids have been reported to inhibit the synthesis of prostaglandins leads to reduced inflammation in various chronic disorders (Glick & Fischer 2013). In recent study, Aliyah et al. (2017) found the presence of citral, limonene, linalool, citronella, geranyl acetate, 2-hexadecen-1-ol,3,7,11,15-tetramethyl- [R[R*R*-(E]] (cas) phytol in leaf essential oils. The variation of the compounds present in the plant leaves is due to changes in geographical, physiological and environmental factors. From FTIR analysis and GC–MS analysis it was found that the C. medica leaves consist of alcohols, alkanes, terpenoids, phytosterols and fatty acids. In another study reported by Lv et al. (2015) found that the citrus fruits also contain the ingredients such as flavonoids, phenolic compounds, terpenoids, polysaccharides and amino acids. The compounds present in the C. medica leaves extract are similar to the biochemical constituents present in the fruits, which are beneficial to human health.

The antimicrobial activity was studied against the selected food borne pathogens. In support of the findings of this study, the inhibition of microbial growth by C. medica extract has previously been demonstrated for S. aureus (Aliyah et al. 2017; Sah et al. 2011; Li et al. 2019), E. coli (Li et al. 2019), B. subtilis (Li et al. 2019) and C. albicans (Aliyah et al. 2017). However, Sah et al. (2011) also failed to detect any inhibition of growth of P. aeruginosa, K. pneumoniae, E. coli, P. vulgaris, A. niger, A. flavus and C. albicans when exposed to C. medica extract. Further, previous studies have also found that C. medica extract inhibited the growth of some microorganisms not tested during this study, including E. faecalis (Sah et al. 2011), M. luteus (Li et al. 2019) and P. acne (Aliyah et al. 2017). In addition to this, the antagonistic activity was evaluated by selecting the S. aureus and C. albicans through Scanning electron microscopy and found changes in morphology, ruptured cell membranes and leakage of cellular constituents were observed. Similar type of study by Li et al. (2019) was reported for E. coli and S. aureus treated with citron essential oil.

In our body, the free radicals are produced and reacts with tissue causes oxidative damage. Our body has complex system of antioxidant defense mechanism of enzymes such as catalase, glutathione peroxidase and superoxide dismutase. However, under certain conditions, there is an imbalance occurs due to excessive production of free radicals results in oxidative stress (Khettal et al. 2017). Antioxidants are the chemicals that inhibits the oxidation and counteract the oxidative damage (Shah & Mehta 2018). Many studies illustrate the importance of natural antioxidants usage in the food processing industry and medical fields. The natural antioxidants have protective role against the reactive oxygen species due to the presence of bioactive compounds. In the present study, the methanolic extract was examined for in-vitro antioxidant activity through DPPH assay and ABTS assay. For DPPH assay and ABTS assay the IC50 values are found to be 300 μg and 450 μg, respectively. There are no reports available related to anticancer activity of C. medica leaves. In this study, the anticancer activity was evaluated against MCF-7 breast cancer cell line. In previous study by Entezari et al. (2009) reported the anti-mutagenicity and anticancer effect of citrus fruit juice.

CONCLUSION

A GC–MS analysis of C. medica leaves confirmed the presence of various bioactive compounds with biological activity and food applications. The C. medica leaf extract showed good antioxidant, anticancer and antimicrobial activity against food-borne pathogens. The abundant compounds present in the extract were linolenic acid and α-linolenic acid trimethylsilyl ester compounds belonging to the omega-3 fatty acid group. Omega-3 fatty acids have a beneficial role in cancer-related complications, as well as having antioxidant properties. Omega-6 fatty acid––eicosanoic acid plays a beneficial role in acting against inflammation and cardiovascular disease. This study indicates the potential for the development of C. medica extract as a natural functional food supplement for reducing the risk of chronic diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge Vignan’s Foundation for Science, Technology and Research and DST- FIST (LSI-576/2013) for providing the facilities to carry out this work.

Footnotes

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

Mikkili Indira: Conceptualisation, writing, original draft preparation, validation.

Karlapudi Abraham Peele: Data curation, visualisation.

K.B.S. Vimala: Investigation.

P. Satya kavya: Investigation, draft preparation.

Isana Sravya: Investigation.

Kodali Vidya Prabhakar: Visualisation, supervision.

Srirama Krupanidhi: Project administration, supervision.

T. C. Venkateswarulu: Conceptualisation, methodology, supervision.

REFERENCES

- Abuajah CI, Ogbonna AC, Osuji CM. Functional components and medicinal properties of food: A review. Journal of Food Science and Technology. 2015;52(5):2522–2529. doi: 10.1007/s13197-014-1396-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adnan M, Bibi R, Mussarat S, Tariq A, Shinwari ZK. Ethnomedicinal and phytochemical review of Pakistani medicinal plants used as antibacterial agents against Escherichia coli. Annals of Clinical Microbiology and Antimicrobials. 2014;13(1):40. doi: 10.1186/s12941-014-0040-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adnan M, Umer A, Ahmad I, Hayat K, Shakeel S. In vitro evaluation of biological activities of Citrus leaf extracts. Sains Malaysiana. 2014;43(2):185–194. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal RK, Gupta S, Mittal G, Khan F, Roy S, Agarwal A. Antifungal susceptibility testing of dermatophytes by agar-based disk diffusion method. International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences. 2015;4:430–436. [Google Scholar]

- Ali S, Khan MR, Sajid M. Phytochemical investigation and antimicrobial appraisal of Parrotiopsisj acquemontiana (Decne) Rehder. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2018;18(1):43. doi: 10.1186/s12906-018-2114-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alissa EM, Ferns GA. Functional foods and nutraceuticals in the primary prevention of cardiovascular diseases. Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism. 2012;2012:569486. doi: 10.1155/2012/569486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aliyah, Himawan A, Rante H, Ningsih DR. GC-MS analysis and antimicrobial activity determination of Citrus medica L. var proper leaf essential oil from South Sulawesi against skin pathogen microorganism. Materials Science and Engineering Conference Series. 2017;259(1):012001. doi: 10.1088/1757-899X/259/1/012001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aparna V, Dileep KV, Mandal PK, Karthe P, Sadasivan C, Haridas M. Anti-inflammatory property of n-hexadecanoic acid: structural evidence and kinetic assessment. Chemical Biology and Drug Design. 2012;80(3):434–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2012.01418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashok Kumar R, Ramaswamy M. Phytochemical screening by FTIR spectroscopic analysis of leaf extracts of selected Indian medicinal plants. International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences. 2014;3(1):395–406. [Google Scholar]

- Asif M. The role of fruits, vegetables, and spices in diabetes. International Journal of Nutrition, Pharmacology Neurological Diseases. 2011;1(1):27. doi: 10.4103/2231-0738.77527. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhaskarachary K. Traditional foods, functional foods and nutraceuticals. Proceedings of the Indian National Science Academy. 2016;82(5):1565–1577. doi: 10.16943/ptinsa/2016/48888. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blondeau N, Lipsky RH, Bourourou M, Duncan MW, Gorelick PB, Marini AM. Alpha-linolenic acid: An omega-3 fatty acid with neuroprotective properties-ready for use in the stroke clinic? Biomed Research International. 2015;2015:519830. doi: 10.1155/2015/519830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byju K, Vasundhara G, Anuradha V, Nair SM, Kumar NC. Presence of phytol, a precursor of vitamin E in Chaetomorpha antinnina. Mapana Journal of Sciences. 2013;12(2):57–65. doi: 10.12723/mjs.25.6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caputo L, Quintieri L, Cavalluzzi MM, Lentini G, Habtemariam S. Anti-microbial and anti-biofilm activities of citrus water-extracts obtained by microwave-assisted and conventional methods. Biomedicines. 2018;6(2):70. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines6020070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan WK, Tan LTH, Chan KG, Lee LH, Goh BH. Nerolidol: A sesquiterpene alcohol with multi-faceted pharmacological and biological activities. Molecules. 2016;21(5):529. doi: 10.3390/molecules21050529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhari SY, Ruknuddin G, Prajapati P. Ethno medicinal values of Citrus genus: A review. Medical Journal of Dr.DY Patil University. 2016;9(5):560. doi: 10.4103/0975-2870.192146. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chhikara N, Kour R, Jaglan S, Gupta P, Gat Y, Phangal A. Citrus medica: Nutritional, phytochemical composition and health benefits: A review. Food and Function. 2018;9(4):1978–1992. doi: 10.1039/C7FO02035J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirmi S, Maugeri A, Ferlazzo N, Gangemi S, Calapai G, Schumacher U, Navarra M. Anticancer potential of citrus juices and their extracts: A systematic review of both preclinical and clinical studies. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2017;8:420. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das L, Bhaumik E, Raychaudhuri U, Chakraborty R. Role of nutraceuticals in human health. Journal of Food Science and Technology. 2012;49(2):173–183. doi: 10.1007/s13197-011-0269-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eilat-Adar S, Sinai T, Yosefy C, Henkin Y. Nutritional recommendations for cardiovascular disease prevention. Nutrients. 2013;5(9):3646–3683. doi: 10.3390/nu5093646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Entezari M, Majd A, Falahian F, Mehrabian S, Hashemi M, Ardeshiri LA. Antimutagenicity and anticancer effects of Citrus medica fruit juice. Acta Medica Iranica. 2009;47(5):373–377. [Google Scholar]

- Eswaraiah G, Peele KA, Krupanidhi S, Indira M, Kumar RB, Venkateswarulu TC. GC-MS analysis for compound identification in leaf extract of Lumnitzera racemosa and evaluation of its in vitro anticancer effect against MCF7 and HeLa cell lines. Journal of King Saud University-Science. 2020;32(1):780–783. doi: 10.1016/j.jksus.2019.01.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eswaraiah G, Venkateswarulu TC, Krupanidhi S, Abraham Peele K, Indira M, Venkata Narayana A. GC-MS analysis for leaf extract of Suaeda nudiflora and screening of their invitro antiproliferative effect against MCF7 and Hela cells. Agriculture Research and Technology: Open Acess Journal. 2019;22(1):556187. doi: 10.19080/ARTOAJ.2019.22.556187. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glick NR, Fischer MH. The role of essential fatty acids in human health. Journal of Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2013;18(4):268–289. doi: 10.1177/2156587213488788. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greene JR, Merrett KL, Heyert AJ, Simmons LF, Migliori CM, Vogt KC, Koppisch AT. Scope and efficacy of the broad-spectrum topical antiseptic choline geranate. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(9):e0222211. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0222211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi A, Majlesi M, Rafieian-Kopaei M. Herbal versus synthetic drugs: Beliefs and facts. Journal of Nephropharmacology. 2015;4(1):27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kausar T, Hanan E, Ayob O, Praween B, Azad ZRAA. A review on functional ingredients in red meat products. Bioinformation. 2019;15(5):358. doi: 10.6026/97320630015358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keservani RK, Kesharwani RK, Vyas N, Jain S, Raghuvanshi R, Sharma AK. Nutraceutical and functional food as future food: A review. Der Pharmacia Lettre. 2010;2(1):106–116. [Google Scholar]

- Khan N, Afaq F, Mukhtar H. Lifestyle as risk factor for cancer: Evidence from human studies. Cancer Letters. 2010;293(2):133–143. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khettal B, Kadri N, Tighilet K, Adjebli A, Dahmoune F, Maiza-Benabdeslam F. Phenolic compounds from Citrus leaves: Antioxidant activity and enzymatic browning inhibition. Journal of Complementary and Integrative Medicine. 2017;14(1):1–13. doi: 10.1515/jcim-2016-0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li ZH, Cai M, Liu YS, Sun PL, Luo SL. Antibacterial activity and mechanisms of essential oil from Citrus medica L. var. sarcodactylis. Molecules. 2019;24(8):1577. doi: 10.3390/molecules24081577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv X, Zhao S, Ning Z, Zheng H, Shu Y, Tao O, Liu Y. Citrus fruits as a treasure trove of active natural metabolites that potentially provide benefits for human health. Chemistry Central Journal. 2015;9(1):68. doi: 10.1186/s13065-015-0145-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madigan M, Karhu E. The role of plant-based nutrition in cancer prevention. Journal of Unexplored Medical Data. 2018;3:9. doi: 10.20517/2572-8180.2018.05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McClements DJ, Xiao H. Designing food structure and composition to enhance nutraceutical bioactivity to support cancer inhibition. Seminars in Cancer Biology. 2017;46:215–226. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2017.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mummed B, Abraha A, Feyera T, Nigusse A, Assefa S. In-vitro antibacterial activity of selected medicinal plants in the traditional treatment of skin and wound infections in Eastern Ethiopia. BioMed Research International. 2018;2018:1862401. doi: 10.1155/2018/1862401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagoor Meeran MF, Javed H, Al Taee H, Azimullah S, Ojha SK. Pharmacological properties and molecular mechanisms of thymol: Prospects for its therapeutic potential and pharmaceutical development. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2017;8:380. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onyeyirichi I, Ogechi N, Oche O, Jerry U, Gero M. Evaluation of chemical constituent of Citrus medica limonum leaf essential oil. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Scientific Innovation. 2014;3(4):306–309. doi: 10.7897/2277-4572.034161. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Panara K, Joshi K, Nishteswar K. A review on phytochemical and pharmacological properties of Citrus medica Linn. International Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biological Archive. 2012;3(6):1292–1297. [Google Scholar]

- Patil M. Quantification of phytochemical constituents and in vitro antioxidant activity in the leaves of Citrus medica. International Journal of Current Pharmaceutical Research. 2017;9(5):119–123. doi: 10.22159/ijcpr.2017v9i5.22153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Powell WS, Rokach J. Biosynthesis, biological effects, and receptors of hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids (HETEs) and oxoeicosatetraenoic acids (oxo- ETEs) derived from arachidonic acid. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)- Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids. 2015;1851(4):340–355. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2014.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao W, Qiao Y. The relationship between the structure and properties of amino acid surfactants based on glycine and serine. Journal of Surfactants and Detergents. 2013;16(6):821–828. doi: 10.1007/s11743-012-1432-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rafiq S, Kaul R, Sofi SA, Bashir N, Nazir F, Nayik G. Citrus peel as a source of functional ingredient: A review. Journal of the Saudi Society of Agricultural Sciences. 2018;17(4):351–358. doi: 10.1016/j.jssas.2016.07.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman A, Siddiqui SA, Oke-Altuntas F, Okay S, Gul F, Demirtas I. Phenolic profile, essential oil composition and bioactivity of Lasia spinosa (L.) Thwaites, Brazilian Archives of Biology and Technology. 2019;62(6):e19170757. doi: 10.1590/1678-4324-2019170757. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sah AN, Juyal V, Melkani AB. Antimicrobial activity of six different parts of the plant Citrus medica Linn. Pharmacognosy Journal. 2011;3(21):80–83. doi: 10.5530/pj.2011.21.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shah BB, Mehta AA. In-vitro evaluation of antioxidant activity of D-Limonene. Asian Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 2018;4:883–887. doi: 10.31024/ajpp.2018.4.6.25. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shridhar G, Rajendra N, Murigendra H, Shridevi P, Prasad M, Mujeeb MA, Arun S, Neeraj D, Vikas S, Suneel D, Vijay K. Modern diet and its impact on human health. Journal of Nutrition and Food Sciences. 2015;5(6):1000430. doi: 10.4172/2155-9600.1000430. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sonboli A, Mojarrad M, Ebrahimi SN, Enayat S. Free radical scavenging activity and total phenolic content of methanolic extracts from male inflorescence of Salix aegyptiaca grown in Iran. Iranian Journal of Pharmaceutical Research. 2010;9(3):293. doi: 10.22037/IJPR.2010.869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockert JC, Horobin RW, Colombo LL. Tetrazolium salts and formazan products in cell biology: Viability assessment, fluorescence imaging, and labeling perspectives. Acta Histochemica. 2018;20(3):159–167. doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2018.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varzakas T, Zakynthinos G, Verpoort F. Plant food residues as a source of nutraceuticals and functional foods. Foods. 2016;5(4):88. doi: 10.3390/foods5040088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M, Doyle MP, Chen D. Combination of levulinic acid and sodium dodecyl sulfate on inactivation of foodborne microorganisms: A review. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 2020;60(15):2526–2531. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2019.1650249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]