Abstract

Context

Transgender and gender diverse (TGD) individuals often seek gender-affirming hormone therapy (GAHT). While receipt of GAHT has been associated with improved well-being, the risk of GAHT discontinuation and its reasons are not well known.

Objective

There were two main objectives: (1) To investigate the proportion of TGD individuals who discontinue therapy after an average of 4 years (maximum 19 years) since GAHT initiation; and (2) to explore reasons for GAHT discontinuation. This was a retrospective cohort study at academic centers providing care to TGD adolescents and adults. TGD individuals prescribed estradiol or testosterone between January 1, 2000, and January 1, 2019, were included. GAHT continuation was ascertained using a 2-phase process. In phase 1, Kaplan–Meier survival analyses were used to examine likelihood of GAHT discontinuation and compare discontinuation rates by age and sex assigned at birth. In phase 2, reasons for stopping GAHT were investigated by reviewing records and by contacting study participants who discontinued therapy. The main outcome measures were incidence and determinants of GAHT discontinuation.

Results

Among 385 eligible participants, 231 (60%) were assigned male at birth and 154 (40%) were assigned female at birth. Less than one-third of participants (n = 121) initiated GAHT prior to their 18th birthday, constituting the pediatric cohort (mean age 15 years), and the remaining 264 were included in the adult cohort (mean age 32 years). In phase 1, 6 participants (1.6%) discontinued GAHT during follow-up, and of those only 2 discontinued GAHT permanently (phase 2).

Conclusion

GAHT discontinuation is uncommon when therapy follows Endocrine Society guidelines. Future research should include prospective studies with long-term follow-up of individuals receiving GAHT.

Keywords: transgender, hormone therapy, estradiol, testosterone

Gender-affirming hormone therapy (GAHT) is often used to help transgender and gender diverse (TGD) adolescents and adults achieve desired feminization or masculinization (1, 2). Endocrine Society guidelines recommend the use of GAHT in TGD people when the adults can articulate persistent incongruent gender identity or when youth have a confirmed TGD identity by a multidisciplinary team (3). GAHT includes steroid hormones such as testosterone or estrogen or medications such as gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists or spironolactone to lower endogenous levels of sex steroid hormones (3, 4). The literature on persistence of GAHT in TGD adolescents and adults is sparse but has important implications since sex steroid hormones may have impacts on cardiovascular, bone health, and fertility outcomes with long-term use (4–9). Individuals who stop GAHT for any reason may need medical and social support in terms of stopping/changing hormone therapy, social retransitioning, and reversal interventions (10). Limited literature on transgender adolescents (11, 12) and adults (11, 13) has shown that the majority of patients who are started on GAHT continue taking GAHT for extended periods of time. Little is known about the factors that prompt some TGD individuals to discontinue GAHT. In clinical practice, a small number of adolescents request to discontinue GAHT. According to Turban and Keuroghlian (14), the process of transitioning, including temporary use of GAHT, may play an important part in gender exploration. In some cases, however, GAHT discontinuation can be the result of external factors, such as unaccepting social environments. It is important to note that discontinuation of GAHT is not the same as detransitioning or retransitioning. The terms detransition or retransition have a broader definition that includes stopping or reversal of transitioning either socially, medically, surgically, or legally (15). In this paper we use the term retransitioning to describe reversal of gender identity to achieve a state that is more congruent with sex assigned at birth. It is important to emphasize that not all persons who discontinue GAHT may do so for the purpose of retransitioning.

The objectives of this study were to (1) investigate what proportion of TGD participants may discontinue therapy after GAHT initiation and (2) examine factors associated with GAHT discontinuation. For the purpose of this article, we will define GAHT as the use of sex steroid hormones estradiol and testosterone only.

Materials and Methods

Research Ethics

The study was approved by the institutional review boards of the participating institutions. Owing to the retrospective design of the study and deidentified data, informed consent was not required for the medical records review for phase 1 of the study. The participants who were contacted during phase 2 of the study provided verbal consent.

Study Overview and Data Collection

The study included TGD participants who initiated GAHT at 2 specialized academic centers, 1 center providing pediatric care and the other primarily focused on TGD adults. Both centers administered GAHT using the medical care model according to the guidelines from Endocrine Society and Standards of Care by the World Professional Association of Transgender Health (WPATH) (3, 16, 17). According to the medical care model, to qualify for GAHT, a qualified mental health practitioner is required to confirm that (1) the patient has persistent gender dysphoria; (2) any coexisting psychological problems that could interfere with treatment were reasonably controlled; and (3) the patient has the mental capacity to provide informed consent for gender-affirming treatments. For adolescents, the mental health provider also has to confirm that any social problems that could interfere with the family's ability to consent or adhere to treatment have been addressed (16).

The study was divided into 2 phases. Phase 1 involved retrospective analysis of data abstracted from the electronic medical records to assess the continuation or discontinuation of GAHT. Phase 2 involved contacting individual participants with evidence of GAHT discontinuation status to ascertain reasons for stopping the treatment. The secondary objective of phase 2 was to determine GAHT continuation status among persons who stopped receiving care or were lost to follow-up at the participating clinical centers.

In phase 1, the charts of all TGD participants age 12 years and older who were prescribed GAHT at Emory Healthcare or Children's Healthcare of Atlanta from January 1, 2000, to January 1, 2019 were reviewed. For the pediatric cohort, International Classification of Diseases 10th revision codes F64.0, F64.1, F64.2, F64.8, and F64.9 were used to identify TGD youth eligible for inclusion in the study. All subjects who were prescribed estradiol or testosterone according to the Endocrine Society guidelines and had a documented TGD identity were included. Participants receiving only GnRH analogs, progestins, or spironolactone, or drugs other than testosterone or estrogen were excluded. Participants receiving hormone therapy for differences of sexual development were excluded as well. Based on chart review, provider notes, and medication refills, the subjects still taking GAHT as of January 1, 2019, were classified as continuing GAHT. If the participant disenrolled from the participating clinical centers, the date of last visit was recorded. If the participant had discontinued GAHT, then the reason, if documented in the chart, was recorded along with the date of the last GAHT prescription.

During phase 2, reasons for stopping GAHT were investigated by reviewing relevant records and by contacting study participants who discontinued therapy. Participants were contacted via email on file to request study participation. If participant did not deny participation, they were contacted by phone. If there was no email on file, the eligible person was contacted by phone directly. The participants were called for a maximum of 3 times. In addition to contacting participants with evidence of GAHT discontinuation, we sent emails to persons who disenrolled from the participating clinical centers and whose GAHT continuation status following disenrollment was unknown.

Quantitative Data Analysis (Phase 1)

The overall study population was divided into 2 age groups. Those who initiated GAHT prior to their 18th birthday represented the pediatric cohort, and those who started GAHT later in life were included in the adult cohort. The 2 age cohorts were compared with respect to socio-demographic characteristics, which included sex assigned at birth (male vs female), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic Whites, non-Hispanic Blacks, Hispanics, Other, and Unknown), and health insurance status (private/self-pay, public, uninsured, and unknown). Each comparison was accompanied by a chi-square test for statistical significance.

The likelihood of GAHT discontinuation was examined via time to event analyses. Each participant was followed from GAHT initiation, or from January 1, 2000, if they started GAHT prior to that date. The follow-up continued until the event of interest (GAHT discontinuation), disenrollment from the participating clinical center (defined as last visit without evidence of stopping GAHT) or study end (January 1, 2019). For persons whose follow-up was less than 1 month (n = 5), the total observation was rounded up to 1 month. The analysis of GAHT discontinuation was carried out by constructing Kaplan–Meier survival curves and the probabilities of this event across groups were compared using a log-rank test.

The results of all statistical tests were expressed as 2-sided P values, using a cutoff of .05 to define statistical significance. All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS statistical software version 28.0 (Chicago, IL)

Qualitative Data Analysis (Phase 2)

If the participant had discontinued GAHT, the information on reason of GAHT discontinuation obtained from medical records or phone calls was recorded and summarized. GAHT receipt status among persons who disenrolled from participating sites was documented and summarized in a similar fashion.

Sensitivity Analysis

The goal of sensitivity analysis was to assess the impact of differential GAHT discontinuation rates in persons who completed follow-up and those who disenrolled from the participating clinical sites. To achieve this goal, the data were reanalyzed by adding information on participants who were lost to follow-up, but recontacted in phase 2 of the study. For individuals who reported still receiving GAHT during the interview, the follow-up was extended to the end of the study (January 1, 2019). For those who reported GAHT discontinuation, the event of interest was assumed to coincide with the time of the last visit.

Results

Characteristics of Study Participants

A total of 385 eligible TGD were prescribed GAHT (estradiol or testosterone) between January 1, 2000, and January 1, 2019 (Table 1). A little less than one-third of all participants (n = 121) initiated GAHT prior to their 18th birthday constituting the pediatric cohort, and the remaining 264 participants were included in the adult cohort. The mean age at the start of GAHT was 32 years in the adult cohort and 15 years in the pediatric cohort. The proportion of transmasculine individuals in the pediatric cohort (55%) was significantly higher than in the corresponding proportion (33%) in the adult cohort (P < .01). The distributions of race/ethnicity categories also differed significantly (P < .01) between groups. Compared with their adult counterparts, the pediatric cohort members included a greater proportion of non-Hispanic Whites (69% vs 55%) and Hispanics (7% vs 2%), but substantially lower proportion of non-Hispanic Blacks (7% vs 20%). The 2 groups were not significantly different with respect to insurance type (P = .87). As the number of nonbinary individuals was extremely small, we did not present the results for binary vs nonbinary gender identities.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic characteristics of all study participants (n = 385)

| Participant | All participants | Pediatric cohort | Adult cohort | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| characteristics | n | %a | n | %a | n | %a | |

| Sex assigned as birth | |||||||

| Female | 154 | 40.0 | 67 | 55.4 | 87 | 33.0 | <.01 |

| Male | 231 | 60.0 | 54 | 44.6 | 177 | 67.0 | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

| Non-Hispanic Whites | 230 | 59.7 | 84 | 69.4 | 146 | 55.3 | |

| Non-Hispanic Blacks | 61 | 15.8 | 9 | 7.4 | 52 | 19.7 | <.01 |

| Hispanics | 14 | 3.6 | 8 | 6.6 | 6 | 2.3 | |

| Otherb | 10 | 2.6 | 4 | 3.3 | 6 | 2.3 | |

| Unknown | 70 | 18.2 | 16 | 13.2 | 54 | 20.5 | |

| Insurance | |||||||

| Private/Self-pay | 279 | 72.5 | 90 | 74.4 | 189 | 71.6 | .87 |

| Public | 55 | 14.3 | 17 | 14.0 | 38 | 14.4 | |

| Uninsured | 32 | 8.3 | 8 | 6.6 | 24 | 9.1 | |

| Not reported | 19 | 4.9 | 6 | 5.0 | 13 | 4.9 | |

| Total | 385 | 100 | 121 | 31.4 | 264 | 68.6 | |

Column percentages, except total row.

Includes Asians/Pacific Islanders and American Indians/Alaska Natives.

Analysis of GAHT Discontinuation (Phase 1)

The interval between GAHT initiation and the end of follow-up ranged from a minimum of less than 1 month to a maximum of 228 months. The average duration of follow-up was 51 months; 24 months in the pediatric cohort and 64 months in the adult cohort. The corresponding median (interquartile range) values were 32 (15-73) for the overall cohort, 21 (8-33) for the pediatric cohort, and 48 (19-93) for the adult cohort.

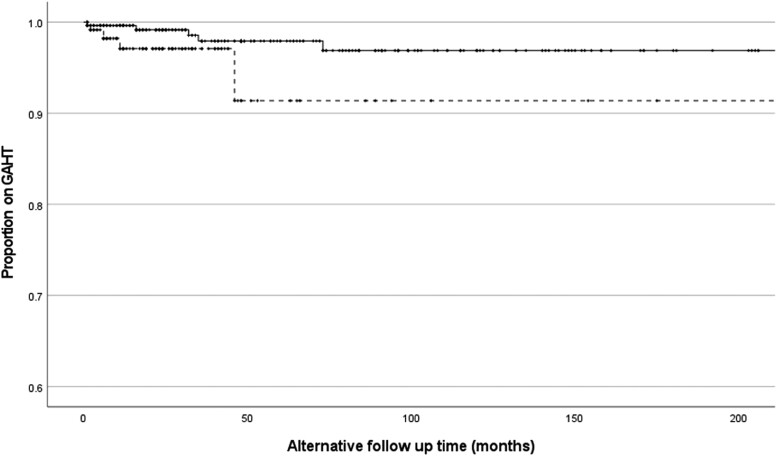

Only 6 participants (1.6%) discontinued GAHT during phase 1, and out of those 5 were members of the adult cohort. Similarly, 5 of the participants who discontinued GAHT during phase 1 were assigned male sex at birth and only 1 was assigned female sex at birth. The Kaplan–Meier survival curves comparing likelihood of GAHT discontinuation by age and sex assigned at birth are shown in Figs. 1 and 2, respectively. Neither difference was statistically significant.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves comparing proportion of continuing GAHT by age. Dotted line represents pediatric group with GAHT initiation age ≤17 years (1 event). Solid line represents adult group with GAHT initiation age 18+ years (5 events). Log-rank P = .82. GAHT, gender-affirming hormone therapy.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves comparing proportion of continuing GAHT by sex assigned at birth. Dotted line represents participants assigned female at birth (1 event). Solid line represents participants assigned male at birth (5 events). Log-rank P = .36. GAHT, gender-affirming hormone therapy.

Reasons for GAHT Discontinuation and Information Obtained From Disenrolled Participants (Phase 2)

As shown in Table 2, 2 of the 6 participants who discontinued GAHT did so due to change in gender identity (2 participants), financial barriers (2 participants), venous thrombosis (1 participant), and “bullying by peers” (1 participant). Among 4 participants who provided additional information via email or telephone, 2 had discontinued GAHT permanently while the remining 2 had only temporarily stopped, and later resumed, therapy. Both individuals who had stopped GAHT permanently (a transgender male and a transgender female) returned to the gender identity that matched their sex assigned at birth, and both indicated not regretting initiating therapy because they viewed it is an important part of understanding their gender identity.

Table 2.

Qualitative information pertaining to patients who stopped GAHT during follow-up (phase 2)

| Case number | Age at GAHT initiation (years) | Sex assigned at birth | GAHT duration (months) | Race | Documented reason for discontinuation in the EMR | Additional information obtained from emails or phone calls |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 43 | Male | 73 | White | Retransitioned to sex assigned at birth. Underwent mastectomy for breast growth from the effect of estradiol and started testosterone therapy | Participant was gaining too much weight, had weakness and mental confusion on estradiol and therefore stopped taking it. Stopped living as affirmed gender |

| 2 | 30 | Male | 35 | Black | Lack of health insurance | Briefly discontinued GAHT due to housing and insurance issues but resumed GAHT for the most part |

| 3 | 29 | Male | 26 | Black | Stopped estradiol as unable to afford clinic visits. Obtained spironolactone on the streets | Unable to contact by email or phone |

| 4 | 16 | Male | 2 | White | Stopped taking estradiol for unknown reasons | Initially stopped GAHT due to bullying by peers. Recently restarted hormones as participant always identified as a female. |

| 5 | 55 | Male | 31 | White | Developed deep vein thrombosis leading to stopping estradiol | Unable to contact by email or phone |

| 6 | 37 | Female | 15 | Black | Diagnosed with sarcoidosis, but unknown why stopped testosterone | Stopped taking testosterone as had a change of heart and started identifying as a female. Also had cystic changes to ovary which made her stop testosterone |

Abbreviations: EMR, electronic medical records; GAHT, gender-affirming hormone therapy

Of the 77 TGD individuals who disenrolled from the participating clinical sites prior to study completion, 26 were later contacted and provided additional information about their GAHT status (Fig. 3). Among those 26, 88.5% (n = 23) were still on GAHT. Of the 3 participants who reported stopping therapy, 1 did so due to insurance issues, 1 stopped GAHT temporarily to conceive a baby, and 1 discontinued testosterone to transition to a nonbinary gender. None of these 3 participants retransitioned to the gender congruent with sex assigned at birth.

Figure 3.

In the phase 1 of the study, out of 385 participants, 302 were still on GAHT as of January 1, 2019. There were 77 transgender individuals who did not have a documented follow-up prior to January 1, 2019, and 6 individuals who were documented to have discontinued GAHT. During the phase 2 of the study, 26 out of 77 individuals who did not have a follow-up documented were able to be reached out to and 4 out of 6 individuals who had documentation of discontinuing GAHT were able to be reached out to. Twenty-three out of 77 individuals who did not have a follow-up documented and were able to be reached out to and were continuing GAHT. GAHT, gender-affirming hormone therapy.

Sensitivity Analysis

After adding information on 26 disenrolled patients contacted during phase 2, the Kaplan–Meier survival curves included a total of 9 GAHT discontinuation events. In the pediatric cohort the total number of events increased to 4, and in the adult cohort the number events remained the same. Five of the participants who discontinued GAHT in the sensitivity analyses were assigned male sex at birth and 4 were assigned female sex at birth. The results of sensitivity analyses are summarized in the Figs. 4 and 5. Neither log-rank test was statistically significant; however, the results of sensitivity analysis by age suggested higher, but statistically insignificant, likelihood of GAHT discontinuation in the pediatric patients relative their adult counterparts.

Figure 4.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves comparing proportion of continuing GAHT by age after including additional 26 patients who were lost to follow-up and contacted later. Dotted line represents pediatric group with GAHT initiation age ≤17 years (4 events). Solid line represents adult group with GAHT initiation age 18+ years (5 events). Log-rank P = .09. GAHT, gender-affirming hormone therapy.

Figure 5.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves comparing proportion of continuing GAHT by sex assigned at birth after including additional 26 patients who were lost to follow-up and contacted later. Dotted line represents participants assigned female at birth (4 events). Solid line represents participants assigned male at birth (5 events). Log-rank P = .53. GAHT, gender-affirming hormone therapy.

Use of GnRH Agonists

None of the patients with evidence of GnRH agonists use discontinued GAHT. These data are limited to only 1 of the participating clinical centers, which contributed 82 out of 121 pediatric participants.

Discussion

In this retrospective cohort study, less than 2% of TGD people receiving GAHT discontinued therapy during follow-up, and of those only 2 reported stopping it permanently. In addition, 3 of 77 participants who disenrolled from the participating sites also reported stopping GAHT, but the true frequency of therapy discontinuation in this group cannot be determined because we were able to contact only 26 of the 77 persons who no longer received care at our clinics. The reported reasons for discontinuation were more commonly related to external factors such as insurance issues, conceiving a baby, and medical complications, as opposed to a change in gender identity.

All cohort members received gender dysphoria evaluation prior to starting GAHT in accordance with the Endocrine Society guidelines and the Standards of Care by the WPATH (3, 17). The participants were initiated on GAHT and monitored by the endocrinology specialists following a referral from a primary care provider and/or self-referred following an evaluation by a mental health provider. As provision of GAHT following a recommended medical model of care may lead to higher rates of therapy adherence, these findings may not be generalizable to an informed consent model of GAHT (18). The informed consent model focuses on the patient's ability to understand risks and benefits of prescribing GAHT (19). While the informed consent model may allow easier access to GAHT and higher satisfaction, no studies to date have compared outcomes of the 2 models of care (20, 21).

Literature on continuation and persistence of GAHT use in TGD individuals is limited but suggests that discontinuation of GAHT is not common. A recent analysis of the data from a US Military Healthcare System found that the 4-year GAHT continuation rate was 70.2%. In that study, transfeminine individuals had a higher continuation rate than transmasculine individuals. Of note, TGD individuals who started hormones as adolescents in that study had a higher continuation rate than TGD individuals who started as adults (12). In a large cohort study with 720 participants from the Amsterdam Cohort of Gender Dysphoria, 98% TGD individuals who had started GAHT in adolescence continued to use GAHT at the follow-up into the adulthood (11). A large sample study conducted in England revealed that a small percentage of 5.3% of TGD individuals discontinued either pubertal suppression or GAHT and retransitioned to sex assigned at birth from 2 pediatric endocrine liaison clinics. The proportion of discontinuation higher in the under 16 years of age group compared with the ≥16-year age group (22).

There is also scarcity of studies that identify the reasons for GAHT discontinuation from either external factors or due to pure retransition. The available publications include a few case reports (14, 23–26) and 1 cross- sectional study (27). In the cross-sectional study, Turban and colleagues (27) observed that 13% of TGD adults participating in a US survey reported past history of retransitioning. The study divided the factors leading to retransition into 2 broad categories: external factors (eg, lack of acceptance in the society) and internal factors (eg, fluctuations in self-identity). Out of 13% individuals who reported retransitioning, only 16% reported an internal driving factor. It is important to note that not all TGD individuals in that study were on GAHT and some had only pursued social transition. Those who reported a history of retransition were less likely to have ever accessed gender-affirming hormones (27). Wiepjes et al analyzed data from a Dutch cohort of TGD people followed for over 30 years, and found that only 0.6% of trans-women and 0.3% of trans-men who underwent gonadectomy experienced regret (13). In an online anonymous survey focused on individuals who stopped medical transition, the most frequently endorsed reason for retransitioning was change in the respondent's personal definition of male and female and newly found comfort with the sex assigned at birth (60.0%) (28). It is important to note that the study survey was shared on social media, professional listservs, and via snowball sampling and thus included many participants who were either self-treated, did not have a confirmed TGD identity, or were not managed by specialists. In another small study with 28 participants, MacKinnon et al described various reasons for retransition, such as an evolving understanding of gender identity or health concerns. A few participants in that study expressed regret, and the majority were pleased with the results of gender-affirming medical or surgical treatments (29).

Taken together the available literature indicates that the rate of hormone discontinuation is extremely low and there is no single reason for hormone discontinuation. TGD individuals who decide to retransition do not fit a particular profile. It is difficult to assess prior to starting GAHT whether someone will discontinue treatment but it is important to counsel the patients and families about the rare possibility of this happening in future.

Our data indicate that the large majority of adolescents who initiated GAHT remained on GAHT. To our knowledge no clinical study has described profiles of adolescents who regret the initial decision of taking GAHT. It is important to note, however, that none of the pediatric cohort participants who stopped GAHT in our study expressed regret about receiving therapy. Only 1 of these participants stopped GAHT permanently, and none retransitioned to the gender congruent with sex assigned at birth. For these reasons, our study does not support delaying initiating GAHT until adulthood for adolescents diagnosed with gender dysphoria and meet other criteria for initiation of GAHT. The American Academy of Pediatrics, the Endocrine Society, WPATH, Pediatric Endocrine Society, and the Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine all recognize the medical necessity of GAHT and endorse such treatments (3, 17, 30–32). In view of the recent rise in legislation aiming to ban GAHT, the fact that some patients end up retransitioning should not be used as a justification for withholding this treatment from all TGD adolescents with established gender dysphoria (33).

An important limitation of our study is the relatively limited success of contacting all study subjects, especially those who disenrolled prior to the end of follow-up. The sensitivity analyses demonstrated the results may change if all participants were followed for the entire study period. Our cohort ascertained from 2 specialized endocrinology practices that rely on medical model of GAHT administration is likely not representative of all TGD people in the United States. As such, these findings may not be generalizable to other health care settings, especially those that rely on an informed consent model. Our findings may also not be generalizable to nonbinary individuals. It should be emphasized that some nonbinary individuals discontinue GAHT after attaining certain goals (eg, lowering of the voice, facial hair with testosterone use) (17). It is also important to note that the mean age of GAHT initiation among adults in our cohort was 32 years, higher than expected based on current experience. The older than expected age of GAHT initiation in our study may have 2 explanations. First, by going back to year 2000, the data may represent historical rather than current practices. Second, it is safe to presume that individuals whose date of GAHT initiation was recorded as January 1, 2000, started therapy prior to that date. These limitations notwithstanding, it is important to point out that our study presents one of the first attempts to examine the likelihood and determinants of GAHT discontinuation in both adult and pediatric populations.

Conclusion

Our study indicates that the majority of TGD individuals who start GAHT adhere to prescribed therapy. Although our sensitivity analyses indicate some uncertainty regarding rates of GAHT discontinuation, they did not affect the overall conclusion. Prior to initiating GAHT patients should be counseled about the possibility of stopping therapy for a variety of reasons, including retransitioning. As individuals who retransition may be more likely to abstain from follow-up, the providers should offer support in nonjudgmental fashion and understand the social stigma associated with retransitioning. Further research into the diverse experiences of people who retransition is necessary as this knowledge will promote a more comprehensive gender-affirming medical care model.

Abbreviations

- GAHT

gender affirming hormone therapy

- GnRH

gonadotropin releasing hormone

- TGD

transgender and gender diverse

Contributor Information

Pranav Gupta, Department of Pediatrics, Division of Endocrinology, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA 30322, USA; Department of Pediatrics, Division of Endocrinology, Children's Healthcare of Atlanta, Atlanta, GA 30322, USA.

Briana C Patterson, Department of Pediatrics, Division of Endocrinology, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA 30322, USA; Department of Pediatrics, Division of Endocrinology, Children's Healthcare of Atlanta, Atlanta, GA 30322, USA.

Lena Chu, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA 30322, USA.

Sarah Gold, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA 30322, USA.

Seth Amos, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA 30322, USA.

Howa Yeung, Department of Dermatology, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA 30322, USA.

Michael Goodman, Rollin's School of Public Health, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA 30322, USA.

Vin Tangpricha, Department of Medicine, Division of Endocrinology, Metabolism and Lipids, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA 30322, USA; Atlanta VA Medical Center, Decatur, GA 30300, USA.

Funding

This research was supported by Washaw Fellow Research Award from the Emory Department of Pediatrics, Emory University School of Medicine and Children's Healthcare of Atlanta. Dr. Tangpricha receives support from National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health, Award Number UL1TR002378. Past and current research support for Drs. Goodman and Tangpricha includes contract AD-12-11-4532 from the Patient Centered Outcome Research Institute, grant R21HD076387 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and grant R01AG066956 from the National Institute of Aging. Dr. Goodman received honorarium from Georgetown University for participating in the “Georgetown Sexuality and Medicine Workshop”. Dr. Goodman provides scientific consultation through Epidemiologic Research and Methods (ERM), LLC; none of his consulting through ERM is related to the topic of the current study. Dr. Yeung is supported in part by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases under award number K23 AR075888 and L30 AR076081. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial disclosures.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. T'Sjoen G, Arcelus J, Gooren L, Klink DT, Tangpricha V. Endocrinology of transgender medicine. Endocr Rev. 2019;40(1):97‐117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Krebs D, Harris RM, Steinbaum A, et al. Care for transgender young people. Horm Res Paediatr. 2022;95(5):405‐414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hembree WC, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Gooren L, et al. Endocrine treatment of gender-dysphoric/gender-incongruent persons: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(11):3869‐3903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Klein DA, Paradise SL, Goodwin ET. Caring for transgender and gender-diverse persons: what clinicians should know. Am Fam Physician. 2018;98(11):645‐653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Maraka S, Singh Ospina N, Rodriguez-Gutierrez R, et al. Sex steroids and cardiovascular outcomes in transgender individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(11):3914‐3923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Getahun D, Nash R, Flanders WD, et al. Cross-sex hormones and acute cardiovascular events in transgender persons: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(4):205‐213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Singh-Ospina N, Maraka S, Rodriguez-Gutierrez R, et al. Effect of sex steroids on the bone health of transgender individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(11):3904‐3913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schagen SEE, Wouters FM, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Gooren LJ, Hannema SE. Bone development in transgender adolescents treated with GnRH analogues and subsequent gender-affirming hormones. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105(12):e4252‐e4263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Neblett MF II, Hipp HS. Fertility considerations in transgender persons. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2019;48(2):391‐402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vandenbussche E. Detransition-related needs and support: a cross-sectional online survey. J Homosex. 2022;69(9):1602‐1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. van der Loos MATC, Hannema SE, Klink DT, den Heijer M, Wiepjes CM. Continuation of gender-affirming hormones in transgender people starting puberty suppression in adolescence: a cohort study in The Netherlands. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2022;6(12):869‐875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Roberts CM, Klein DA, Adirim TA, Schvey NA, Hisle-Gorman E. Continuation of gender-affirming hormones among transgender adolescents and adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022;107(9):e3937‐e3943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wiepjes CM, Nota NM, de Blok CJM, et al. The Amsterdam cohort of gender dysphoria study (1972-2015): trends in prevalence, treatment, and regrets. J Sex Med. 2018;15(4):582‐590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Turban JL, Keuroghlian AS. Dynamic gender presentations: understanding transition and “de-transition” among transgender youth. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2018;57(7):451‐453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Irwig MS. Detransition among transgender and gender-diverse people-an increasing and increasingly complex phenomenon. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022;107(10):e4261‐e4262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Coleman E, Bockting W, Botzer M, et al. Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-nonconforming people, version 7. Int J Transgend. 2012;13(4):165‐232. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Coleman E, Radix AE, Bouman WP, et al. Standards of care for the health of transgender and gender diverse people, version 8. Int J Transgend Health. 2022;23(Supp 1):S1‐S259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Parkinson P. Adolescent gender dysphoria and the informed consent model of care. J Law Med. 2021;28(3):734‐744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cavanaugh T, Hopwood R, Lambert C. Informed consent in the medical care of transgender and gender-nonconforming patients. AMA J Ethics. 2016;18(11):1147‐1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Spanos C, Grace JA, Leemaqz SY, et al. The informed consent model of care for accessing gender-affirming hormone therapy is associated with high patient satisfaction. J Sex Med. 2021;18(1):201‐208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Solanki P, Colon-Cabrera D, Barton C, et al. Gender-affirming hormone therapy for the trans, gender diverse, and nonbinary community: coordinating world professional association for transgender health and informed consent models of care. Transgend Health. 2023;8(2):137‐148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Butler G, Adu-Gyamfi K, Clarkson K, et al. Discharge outcome analysis of 1089 transgender young people referred to paediatric endocrine clinics in England 2008-2021. Arch Dis Child. 2022;107(11):1018‐1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Expósito-Campos P, Gómez-Balaguer M, Hurtado-Murillo F, García-Moreno RM, Morillas-Ariño C. Medical detransition following transgender identity reaffirmation: two case reports. Sex Health. 2022;18(6):498‐501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Marchiano L. Gender detransition: a case study. J Anal Psychol. 2021;66(4):813‐832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Levine SB. Transitioning back to maleness. Arch Sex Behav. 2018;47(4):1295‐1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gribble KD, Bewley S, Dahlen HG. Breastfeeding grief after chest masculinisation mastectomy and detransition: a case report with lessons about unanticipated harm. Front Glob Womens Health. 2023;4:1073053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Turban JL, Loo SS, Almazan AN, Keuroghlian AS. Factors leading to “detransition” among transgender and gender diverse people in the United States: a mixed-methods analysis. LGBT Health. 2021;8(4):273‐280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Littman L. Individuals treated for gender dysphoria with medical and/or surgical transition who subsequently detransitioned: a survey of 100 detransitioners. Arch Sex Behav. 2021;50(8):3353‐3369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. MacKinnon KR, Kia H, Salway T, et al. Health care experiences of patients discontinuing or reversing prior gender-affirming treatments. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(7):e2224717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rafferty J; Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health; Committee on Adolescence; Section on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health and Wellness . Ensuring comprehensive care and support for transgender and gender-diverse children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2018;142(4):e20182162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lopez X, Marinkovic M, Eimicke T, Rosenthal SM, Olshan JS. Statement on gender-affirmative approach to care from the pediatric endocrine society special interest group on transgender health. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2017;29(4):475‐480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine . Recommendations for promoting the health and well-being of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender adolescents: a position paper of the Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine. J Adolesc Health. 2013; 52(4):506‐510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Barbee H, Deal C, Gonzales G. Anti-transgender legislation-a public health concern for transgender youth. JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176(2):125‐126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.