Abstract

Patient: Male, 35-year-old

Final Diagnosis: Cerebral venous thrombosis • secondary polycythemia • subarachnoid hemorrhage

Symptoms: Acute headache • hemiparesis

Clinical Procedure: Magnetic resonance angiography of head and neck • magnetic resonance venography of head

Specialty: Neurology

Objective:

Unusual clinical course

Background:

Cerebral ischemia and hemorrhages were reported to be the main complications of polycythemia vera (PV). The relationship between PV and increased risk of the cerebrovascular events has been established. Some patients with secondary polycythemia have thromboembolic events comparable to those of PV. However, secondary polycythemia that leads to cerebrovascular events is uncommon.

Case Report:

A 35-year-old man without any prior medical history presented with mild clinical acute ischemic stroke and polycythemia. The patient then showed worsening neurological deficits that were later attributed to the concurrent cerebral venous thrombosis, which led to malignant cerebral infarction with hemorrhagic transformation, and subarachnoid hemorrhage. His polycythemia appeared to be secondary to bacterial infection. The treatments for the secondary polycythemia were first phlebotomy and intravenous hydration, followed by intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotics. PV was excluded because the JAK2 V617F mutation was absent, the patient’s peripheral blood smear suggested secondary polycythemia due to bacterial infection, and there were improvements in hemoglobin, erythrocyte count, and hematocrit after intravenous antibiotics. At the 1-month follow-up, he was moderately dependent, and hemoglobin, erythrocyte count, and hematocrit were within normal limits, without receiving any further phlebotomy or cytoreductive agents.

Conclusions:

This case highlights the plausible causation of secondary polycythemia that could lead to concomitant cerebral thrombosis and hemorrhagic events. The diagnosis of cerebral venous thrombosis should be considered in a patient who presents with headache, focal neurological deficits, polycythemia, and normal head computed tomography scan.

Key words: Cerebral Hemorrhage, Cerebral Infarction, Intracranial Thrombosis, Polycythemia, Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

Background

Polycythemia vera (PV) is a myeloproliferative neoplasm characterized by an increase in red blood cell mass, which can lead to thrombotic events [1]. PV was reported to be the cause of some vascular diseases, including cerebral ischemic and hemorrhagic events, in several studies [2–10]. According to these reports, PV has been established to increase the risk of cerebrovascular events. In comparison, secondary polycythemia involves overproduction of erythrocytes due to various etiologies ranging from genetic abnormalities to secondary to other diseases [11]. Recently, cases of secondary polycythemia were reported to be increasing clinically [12,13]. Secondary polycythemia is defined as preserved increase of hemoglobin and/or hematocrit without JAK2 V617F mutation and non-subnormal serum erythropoietin level [13]. Some patients with secondary polycythemia have thromboembolic events comparable to those of PV. The risk of thrombosis events in secondary polycythemia was reported to be comparable to those of low-risk PV patients [12], particularly if the diagnosis was not made before the thromboembolic event [13]. A low-risk PV patient is defined as age <60 years old without a previous thrombosis event [14]. Although uncommon, secondary polycythemia can lead to cerebrovascular events, such as ischemic stroke and cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT) [15–18]. Here, we present a rare case of a 35-year-old man with secondary polycythemia who developed concomitant CVT, which led to hemorrhagic transformation of acute cerebral infarction, and subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Case Report

A 35-year-old man without any prior medical history presented with sudden intermittent mild-to-moderate intensity headache in the occipital region, which was temporarily relieved after taking over-the-counter pain killers. One day later, he developed numbness in the left side of his body and slight weakness in his left upper and lower limbs, for which he went to the emergency room (ER). His National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) was 3. The patient worked as a carpenter performing moderate physical work, smoked tobacco rarely, and denied the use of hormone therapy or recreational drugs. There was no history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, previous thromboembolism, atrial fibrillation, malignancy, weight loss, Human Immunodeficiency Virus infection or its risk factors, and no other chronic lung or cardiac diseases. There was no family history of thromboembolism, polycythemia, or malignancy.

He presented in the ER with Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) 15, normal body weight, and all vital signs were within normal range. A non-contrast head computed tomography scan (CT scan) revealed very mild cerebral edema, particularly in the right hemisphere of the brain (Figure 1). Increased hemoglobin (19.3 g/dL), erythrocytosis (5.97×106/µL), increased hematocrit (58.3%), and increased D-dimer (643 ng/mL) were abnormal findings in his blood work. His peripheral blood smear showed normochromic normocytic erythrocytosis, as well as relative neutrophilia with reactive neutrophils and monocytes, which suggest secondary polycythemia due to bacterial infection. Despite intravenous hydration and therapeutic phlebotomy within 24 h of admission, his hemoglobin (19.3 g/dL), erythrocyte count (6.08×106/µL), and hematocrit (60.8%) were still above the normal ranges. He tested negative for JAK2 V617F mutation. Due to the limited resources in our facilities, we could not further test for serum erythropoietin level and mutations in exon 12 of JAK2. He received oral aspirin 80 mg daily for secondary stroke prevention.

Figure 1.

First non-contrast head CT scan. The patient’s first non-contrast head CT scan on the second day following his neurological deficits showed mild cerebral edema without any intracerebral infarction or hemorrhage, ASPECT score 10. Red arrows indicate cerebral edema.

On the following day, he had worsening weakness of his left limbs and after a few hours, he was somnolent. NIHSS was 15. A non-contrast head CT scan was repeated, showing subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) in the right parietal region, malignant cerebral infarction in the right frontotemporoparietal regions, and intracerebral hemorrhagic transformation in the right basal ganglia, accompanied by diffuse cerebral edema (Figure 2). His antiplatelet therapy was stopped, and he was started on intravenous infusion of hyperosmotic solution mannitol with daily tapering-off doses, oral nimodipine, and oral folic acid. One day after commencement of therapy, he was fully conscious. Broad-spectrum antibiotics of ceftriaxone were given intravenously for 5 days while waiting for blood and urine cultures. The antibiotics were discontinued after negative bacterial culture.

Figure 2.

Second non-contrast head CT scan. The patient’s second non-contrast head CT scan on the 4th day after his firs neurological deficits showing subarachnoid hemorrhage in right parietal region (green arrows), intracerebral hemorrhage in right basal ganglia (yellow arrows) that causes midline shift to the left, and cerebral infarction in right frontotemporoparietal regions (blue arrows) with ASPECT score 1.

The patient also underwent brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), magnetic resonance arteriography (MRA), and magnetic resonance venography (MRV) on the 10th day of his hospital stay (Figures 3–5). His brain MRA showed no aneurysms (Figure 4), suggesting that his SAH might have occurred spontaneously without arterial abnormality. There were clear indications of CVT identified in the patient’s left transverse and sigmoid sinuses in the brain MRV (Figure 5). Investigations such as toxicological screening, thrombophilia tests, and immunoserological tests were not performed. Oral anticoagulant warfarin was then started along with physiotherapy and occupational therapy. His blood work evaluation showed improvement in his hemoglobin (17.3 g/dL), erythrocyte count (5.38×106/µL), and hematocrit (52.8%). The patient was discharged with NIHSS 11 on the 14th day of his hospital stay.

Figure 3.

Brain MRA axial T2 showing cerebral infarction in right frontotemporoparietal regions (blue arrows) with hemorrhagic transformation in right basal ganglia (yellow arrows) without any midline shift.

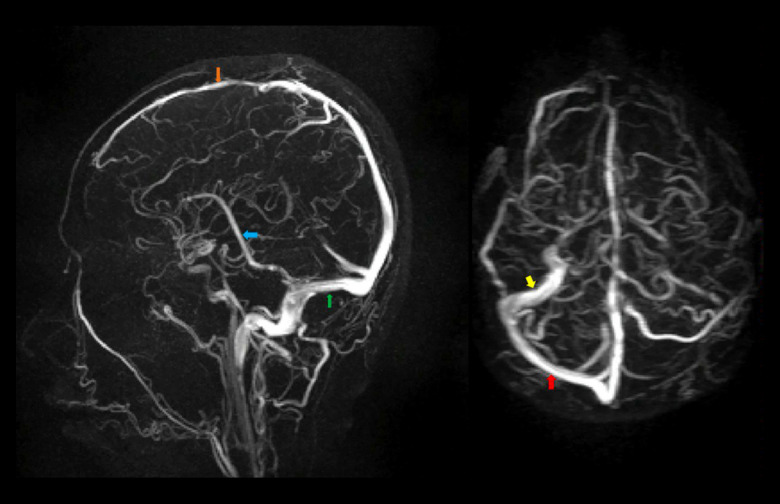

Figure 4.

Brain MRA showing normal bilateral medial, anterior, and posterior cerebral arteries, vertebral arteries, anterior and posterior communicating arteries, internal carotid arteries, as well as basilar arteries, without aneurysms.

Figure 5.

Brain MRV showing non-visualization of left transverse and sigmoid sinuses with normal visualization of superior (orange arrow) and inferior sagittal sinuses (blue arrow), straight sinus (green arrow), and right transverse (red arrow) and sigmoid sinuses (yellow arrow).

The 1-month follow-up after discharge showed NIHSS 10, moderately dependent. He also underwent bone marrow puncture, which showed increased granulopoiesis, thrombopoiesis, and erythropoiesis, with multilineage dysplasia. At that time, his blood marker evaluations for hemoglobin (15.7 g/dL), erythrocyte count (4.92×106/µL), and hematocrit (47%) were within normal limits.

Discussion

A 35-year-old man presented with no previous medical history or family medical history, and no current atrial fibrillation, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or peripheral arterial/venous diseases. This patient showed NIHSS 3 on his first admission with no sign of infarction, and no early signs of hemorrhagic transformation in his first head CT scan, such as loss of the density contrast of the lentiform nucleus and insular ribbon, hemispheric sulcus effacement, or hyperdense middle cerebral artery [19,20]. However, the mild cerebral edema in his first CT scan suggested a possible ongoing cerebral ischemic process.

At this point, there were no risk factors or current medical issues that could predict the hemorrhagic transformation in this patient, except for his secondary polycythemia. On the day when he had worsening neurological deficits, the NIHSS worsened to 15, showing a symptomatic hemorrhagic transformation since his NIHSS increased by >4 points in the first 36 h of stroke onset [21]. The worsening condition was later proved to be caused by the malignant cerebral infarction and intracerebral hemorrhagic transformation as well as SAH in his second head CT scan. According to the European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study (ECASS), the hemorrhagic transformation could be categorized into small parenchymal hemorrhage since the intracerebral hemorrhage covered <30% of the infarct area and showed a mild mass effect [22].

After the finding of the CVT in this patient, the clinical manifestations could be better explained. The thrombosis in his left transverse sinus may have increased venous and capillary pressure, which later may have decreased perfusion in his brain and led to ischemic injury. This, in turn, may have caused cytotoxic cerebral edema due to the intracellular swelling. The damage in the blood-brain barrier leads to vasogenic edema and leakage to the interstitial spaces. The increased cerebral venous pressure then can cause intraparenchymal hemorrhaging [23]. Accordingly, we suggest that the CVT in this patient led to his malignant cerebral infarction and hemorrhagic transformation despite its contralateral location to the thrombosed sinus transversus.

The exact cause of the SAH in this patient remains unknown, although there was a report of a rare case of cortical SAH in transverse sinus thrombosis [24]. The subarachnoid hemorrhage due to CVT may be different from those of arterial origins, since it is usually localized in the cerebral convexity and does not involve the basal cisterns, accompanied by hemorrhagic venous infarction due to venous hypertension, and caused by local inflammatory response of the CVT [24–26]. In these cases, SAH usually occurred in the neighboring region of the thrombosed veins. However, in our patient, the SAH was located in the right parietal convexity area and the thrombosed vein was located in his left transverse sinus. The possibility of the venous-causing SAH could also be supported by the normal cerebral MRA of this patient and the non-involvement of the basal cistern. However, an arterial origin of the SAH could still be considered since there were no signs of venous hemorrhage in his MRV and the contralateral location of the hemorrhage to the thrombosed transverse sinus.

According to the 2016 revised World Health Organization diagnostic criteria for PV, all 3 major criteria or the first 2 major criteria and the minor criterion should be present to definitively diagnose PV [1]. The major criteria are: hemoglobin >16.5 g/dL in men or >16 g/dL in women or hematocrit >49% in men or >48% in women; bone marrow tri-lineage proliferation with pleomorphic mature megakaryocytes; and the presence of JAK2 mutation. The minor criterion is a subnormal serum erythropoietin level. Unfortunately, serum erythropoietin level and mutations in exon 12 of JAK2 were not examined due to the hospital’s limited resources, which might challenge the exclusion of PV. However, the reasons the patient was diagnosed with secondary polycythemia were as follows: the absence of JAK2 V617F mutation despite the first and second major criteria of PV, the patient’s peripheral blood smear suggested secondary polycythemia due to bacterial infection, and the improvement in hemoglobin, erythrocyte count, and hematocrit after intravenous antibiotics were given without any routine cytoreduction agents or phlebotomy. However, in the limited-resources setting in which not all screening tests could be performed, the etiologies of polycythemia due to genetic, malignancy, or smoking could not be dismissed.

The treatment strategy in this patient was adjusted once the hemorrhagic transformation of cerebral infarction and SAH were found. Mannitol was administered to reduce the brain edema as well as the possible mass effect from the intracerebral hemorrhage. Nimodipine was administered to prevent the cerebral vasospasm due to the subarachnoid hemorrhage. After the finding of the cerebral sinus venous thrombosis, oral anticoagulants were also started. Concerning the polycythemia treatment, intravenous fluid hydration and phlebotomy were first chosen to reduce red blood cell mass and prevent further thrombosis. However, these treatments did not immediately improve the blood work markers. After peripheral blood smears showed possible bacterial infection and JAK2 mutation was negative, the infection source was investigated by culturing the patient’s blood and urine while intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotics were started. However, we could not confirm the source of infection in this patient. No further clinical, laboratory, and imaging examinations’ results were suggestive of infection. The patient’s blood markers evaluation for polycythemia were improved following our protocol guidelines to prevent further cardiovascular and major thrombosis events without any further treatments of phlebotomy or cytoreductive agents [27].

Our report is limited due to the insufficient data from genetic, toxicological, and non-hematological malignancy screening. In addition, we did not find any specific bacteria in the blood and urine cultures that would support the diagnosis of bacterial infection in this patient. However, the serial hemoglobin and hematocrit, as well as the peripheral blood smear data, supported the possibility of secondary polycythemia due to a non-specific bacterial infection. Since we found both polycythemia and CVT at the patient’s presentation, we considered that the polycythemia preceded the CVT. Learning from this case, we recommend further investigations for the diagnosis of CVT in a patient that presents with headache, focal neurological deficits, polycythemia, and normal head CT scan, because this is a life-threatening condition that can lead to cerebral ischemia, hemorrhagic transformation, and even SAH, which would in turn can increase morbidity.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the presentation of CVT that leads to malignant cerebral ischemia, hemorrhagic transformation, and possible SAH in a relatively young man with secondary polycythemia is uncommon. This case highlights the plausible causation of secondary polycythemia, which led to the concomitant cerebral thrombosis and hemorrhagic events. The diagnosis of cerebral venous thrombosis should be considered in a patient that presents with headache, focal neurological deficits, polycythemia, and normal head CT scan.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher

Declaration of Figures’ Authenticity

All figures submitted have been created by the authors who confirm that the images are original with no duplication and have not been previously published in whole or in part.

References:

- 1.Vannucchi AM, Guglielmelli P, Tefferi A. Polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia: Algorithmic approach. Curr Opin Hematol. 2018;25(2):112–19. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0000000000000402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Opherk C, Brüning R, Pellkofer HL, et al. Subarachnoid hemorrhage and diplopia as initial presentation of polycythemia vera. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2005;19(4):279–80. doi: 10.1159/000084372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abdel-Rahman I, Murphy C. Recurrent ischaemic stroke unveils polycythaemia vera. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2014-207625. bcr2014207625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crespo AM, Abraira L, Guanyabens N, et al. Recurrent stroke with rapid development of intracranial stenoses in polycythemia vera. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016;25(4):e41–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2015.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ren S, Gao F, Chen Z, Wang Z. A case report of cerebral infarction caused by polycythemia vera. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97(52):e13880. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000013880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen L, Xiao H, Hu Z. Cerebral hemorrhage of a 50-year-old female patient with polycythemia vera. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2019;28(8):e110–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2019.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chow LC, Chew LP, Leong TS, et al. Thrombosis and bleeding as presentation of COVID-19 infection with polycythemia vera: A case report. SN comprehensive clinical medicine. 2020;2:2406–10. doi: 10.1007/s42399-020-00537-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cao YY, Cao J, Bi ZJ, et al. Hemorrhagic transformation after acute ischemic stroke caused by polycythemia vera: Report of two case. World J Clin Cases. 2021;9(25):7551. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i25.7551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hasui H, Iseki T, Ueno Y, et al. Recurrent and multiple intracerebral hemorrhages in polycythemia vera secondary to myelofibrosis: A case report and literature review. Case Rep Neurol. 2022;14:274–80. doi: 10.1159/000525171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuznetsova PI, Raskurazhev AA, Shabalina AA, et al. Red blood cell morphodynamics in patients with polycythemia Vera and stroke. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(4):2247. doi: 10.3390/ijms23042247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haider MZ, Anwer F. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Secondary polycythemia. [Updated 2023 May 8]. [cited 2023 Jul 20]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK562233/ [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krečak I, Holik H, Zekanovi I, et al. Thrombotic risk in secondary polycythemia resembles low-risk polycythemia vera and increases in specific subsets of patients. Thromb Res. 2022;209:47–50. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2021.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nguyen E, Harnois M, Busque L, et al. Phenotypical differences and thrombosis rates in secondary erythrocytosis versus polycythemia vera. Blood Cancer J. 2021;11(4):75. doi: 10.1038/s41408-021-00463-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Triguero A, Pedraza A, Pérez-Encinas M, et al. Low-risk polycythemia vera treated with phlebotomies: Clinical characteristics, hematologic control and complications in 453 patients from the Spanish Registry of Polycythemia Vera. Ann Hematol. 2022;101(10):2231–39. doi: 10.1007/s00277-022-04963-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nagaraju SP, Bairy M, Attur RP, Sambhaji CJ. Cerebral venous thrombosis and secondary polycythemia in a case of nephrotic syndrome. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2016;27(2):391–94. doi: 10.4103/1319-2442.178575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou M, Liu X, Li L. Secondary polycythaemia from chronic hypoxia is a risk for cerebral thrombosis: A case report. BMC Neurology. 2023;23(1):1–4. doi: 10.1186/s12883-023-03277-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corse AK, Kurtis H. Ischemic stroke caused by secondary polycythemia and incidentally-found renal cell carcinoma: A case report. Am J Case Rep. 2018;19:638–41. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.909322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pandian JD, Sebastian IA, Sidhu A. Acute ischaemic stroke in secondary polycythaemia due to complex congenital cyanotic heart disease. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12(10):e231261. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2019-231261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang J, Yang Y, Sun H, Xing Y. Hemorrhagic transformation after cerebral infarction: current concepts and challenges. Ann Transl Med. 2014;2(8):81. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2014.08.08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jaillard A, Cornu C, Durieux A, et al. Hemorrhagic transformation in acute ischemic stroke: the MAST-E study. Stroke. 1999;30(7):1326–32. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.7.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spronk E, Sykes G, Falcione S, et al. Hemorrhagic transformation in ischemic stroke and the role of inflammation. Front Neurol. 2021;12:661955. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.661955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fiorelli M, Bastianello S, von Kummer R, et al. Hemorrhagic transformation within 36 hours of a cerebral infarct: Relationships with early clinical deterioration and 3-month outcome in the European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study I (ECASS I) cohort. Stroke. 1999;30(11):2280–84. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.11.2280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tadi P, Behgam B, Baruffi S. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Cerebral venous thrombosis. 2022 Jun 17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arévalo-Lorido JC, Carretero-Gómez J. Cerebral venous thrombosis with subarachnoid hemorrhage: A case report. Clin Med Res. 2015;13(1):40–43. doi: 10.3121/cmr.2014.1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cuvinciuc V, Viguier A, Calviere L, et al. Isolated acute nontraumatic cortical subarachnoid hemorrhage. Am J Neuroradiol. 2010;31:1355–62. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kato Y, Takeda H, Furuya D, et al. Subarachnoid hemorrhage as the initial presentation of cerebral venous thrombosis. Intern Med. 2010;49:467–70. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.49.2789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marchioli R, Finazzi G, Specchia G, et al. Cardiovascular events and intensity of treatment in polycythemia vera. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:22–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1208500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]