Abstract

Background:

Inadequate differentiated diagnostic features of predominantly colonic inflammatory bowel diseases i.e., ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s colitis, may lead to inexact diagnosis of “indeterminate colitis”. About 15% of indeterminate colitis patients are diagnosed at colonoscopy, in colonic biopsies, and/or at colectomy. Managing outcomes of indeterminate colitis, given its unpredictable clinical presentation, depends on future diagnosis of colitis, Crohn’s colitis or ulcerative colitis.

Objective:

Overview the diagnostic efficacy of ectopic colonic ileal metaplasia and human α-defens 5 (DEFA5 alias HD5) for accurate delineation of indeterminate colitis into authentic Crohn’s colitis and/ or ulcerative colitis.

Design:

We describe a targeted protein for potentially differentiating indeterminate colitis into an accurate clinical subtype diagnosis of inflammatory bowel diseases i.e., ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s colitis.

Patients:

Twenty-one patients with the clinically inexact diagnosis of indeterminate colitis were followed, reassessed and data analyzed.

Main outcome measures:

We observed that (i) some patients had their original diagnosis changed from indeterminate colitis to either ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s colitis; and (ii) human α-defensin 5 is aberrantly overexpressed in Crohn’s colitis.

Results:

Fifteen of the twenty-one (71.4%) patients with indeterminate colitis had their inconclusive diagnosis changed; nine patients changed to ulcerative colitis and six to Crohn’s colitis. In human colon surgical samples, Human α-defensin-5 was significantly upregulated in Crohn’s colitis. In addition, Human α-defensin 5 processing enzyme, matrix metalloptotease-7 was inversely expressed compared to Human α- Defensin 5.

Limitation:

Due to the sequence homology of the α-defensin class of proteins, preceding efforts to raise antibodies (Abs) against DEFA5 have limitations to produce adequate specificity. The Abs used in previous assays recognizes the α-defensins, active α-defensins 5 and inactive pro- α-defensins 5. Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) to determine specificity and sensitivity of α-defensins 5, which is diagnostic of CC disease, and NOT other α-defensins is the limitation to overcome.

Conclusion:

It is feasible to differentiate ulcerative colitis from Crohn’s colitis among patients with inexact diagnosis of indeterminate colitis using Human α-defensin 5 as a molecular biosignature delineator.

Keywords: inflammatory bowel disease, indeterminate colitis, Ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s colitis, Human alpha-defensin 5

Introduction

Inadequate differentiated diagnostic features of the two predominantly colonic inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) i.e., ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s colitis (CC), may lead to an inexact/inconclusive diagnosis of indeterminate colitis (IC). 1,2 Managing phenotypic outcomes of IC, given its unpredictable clinical presentation and disease course, is challenging in endoscopic medicine. 1,2 A significant subgroup of IBD patients are misdiagnosed or are delayed to be diagnosed even when a combined state-of-the-art classification system of clinical, endoscopic, radiologic and histologic tools is used. 1,2 The objective of this overview is to discuss about the identified molecular-biomarkers that is likely to help clinicians more accurately differentiate the inexact IC diagnosis into authentic UC or CC. 3,4 In order to fulfill these objective, surgical human colon tissues was assayed for aberrant expression of proteins. These analyses provide quantitative and qualitative data about cellular systems, can potentially delineate diseases within the same organ during the patient's first biopsy visit to the clinic and may offer insight into potential causes of inflammation in CC. 3,4 Human α-defensin–5 (DEFA5 alias HD5) was the only gene to show up in both the microarray and the NanoString PCR array demonstrated that DEFA5 was increased 118-fold in CC versus UC, compared to 31-fold analyzed by microarray. 5

In colorectal surgery, the distinction between UC and CC is of utmost importance when determining a patient’s candidacy for pouch surgery, the restorative proctocolectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (RPC-IPAA). 6) Approximately 15-30% of patients whose UC or IC is surgically treated resolved with an ultimate diagnosis of CC, for which surgery may have been contraindicated. 7,8 Construction of RPC-IPAA in these patients often is painstaking due to multiple postoperative complications and may result in pouch failure range from 5% to 18% when the ultimate diagnosis is CC with significant morbidity. 7, 9,10 Change of diagnosis of IC to UC or CC is also observed in patients with IBD before colectomy, 11,12 as is the development of de novo Crohn’s ileitis after surgical intervention. 10 Incorrect diagnosis and treatment course carries potential morbidity from inappropriate and unnecessary surgeries, 8,13 and underscores the necessity of research efforts aimed at a more accurate diagnosis of the IBD. 3,4 This paper discusses a potential diagnostic molecular biomarker for delineating IC into an accurate clinical diagnosis of authentic UC or CC prior to appropriate care intervention. 3,4,14 These successful studies are the first of their kind to use DEFA5 in the colon microenvironment to delineate the IBD subtypes. The gene for DEFA5 was the single highest overexpressed gene in the CC profile.

DEFA5 is a human protein that is encoded by the DEFA5 gene and is highly expressed in secretory granules of Paneth cells of the small intestine (ileum). 15 DEFA5 is a microbicidal and cytotoxic peptide involved in host defense mechanisms and is responsible for non-specific killing of microbes. 15,16

In determining levels of DEFA5 in the IBD, we overviewed its possible mechanism. It is known that MMP-7 is responsible for cleaving and activating DEFA5. 17,18,19 Although MMP-7 did not show up on the microarray, we sought to determine if levels of MMP-7 were also aberrant in IBD. Our data indicate that there is not a significant change in the levels of MMP-7 between UC and CC except when comparing moderate and severe CC to mild UC, but we observed an inverse relationship between levels of DEFA5 and Pro-MMP-7 in the IBD. The relationship between high levels of DEFA5 and low levels of MMP-7 in CC seems to suggest that there may be a dysfunction in the activation pathway of DEFA5 processing in CC, and therefore, gives us a potential mechanism for inflammation in CC.

To date, there is no available single molecular biomarker that has proven to have the desired diagnostic qualities in IBD. In this overview, we provide DEFA5 as a possible signature biomarker to solve the diagnostic ambiguity and delay in IBD. Several lines of evidence herein presented suggest that the use of DEFA5, also abbreviated as HD5, as a biomarker to molecularly differentiate CC from UC in otherwise inexact IC diagnosis is a conceptual innovative strategy for identifying appropriate patients with colonic IBD for recommended surgical treatment regimens.

Methods

Clinical Samples:

Studies were approved by the Meharry Medical College (IRB file number: 100916AM206) and Vanderbilt University (IRB file numbers: 080898 and 100581) Institutional Ethical Review Board Committees and conducted in accordance with the Second International Helsinki Declaration. 7,20 Informed consent in the initial studies was given, and participation was voluntary. The patients used in the studies were adults with definitive UC, CC and IC. 3,4 Full thickness surgical colectomy tissue samples were analyzed as previously described. 3,4

Diagnostic criteria for inflammatory bowel disease

Pathology teams at Meharry Medical College (BRB, SDJ) and Vanderbilt University Schools of Medicine (MKW) used the following protocol criteria for the final surgical pathology reporting.

Criteria for ulcerative colitis:

Characteristic pattern of involvement of colon, worse distally in untreated patients; lack of perianal or fistulizing disease; no granulomas, except in association with ruptured/injured crypts; no transmural lymphoid aggregates or other transmural inflammation; no involvement of terminal ileum, except mild “backwash ileitis” in cases with severe cecal involvement and no pyloric metaplasia in terminal ileum.

Criteria for Crohn’s disease:

Involvement of other sites in GI tract (skip lesions, segmental disease); perianal or fistulizing disease; granulomas, not in association with ruptured/injured crypts and terminal ileum involvement.

Criteria for indeterminate colitis:

Distribution favors UC, but focal transmural inflammation, or inflammation in ileum more than expected in backwash ileitis and no fistulizing disease.

Vanderbilt Patient Medical Records Database:

The availability of a detailed IBD patient database registry at VUMC makes chart review and follow-up surveillance possible. Medical records data on patient demographics, preoperative variables prior to and after the time of RPC-IPAA surgery, surveillance endoscopic and clinical findings, and medical and surgical treatment history are able to be retrieved retrospectively. Further, VUMC has many health centers of practices located throughout greater Nashville metropolitan area and parts of Kentucky that provide referrals to the IBD center.

Indeterminate colitis clinical retrospective study:

A retrospective investigation was conducted to identify a cohort of patients diagnosed with IC and registered in the IBD Center at VUMC. Twenty-one patients, initially classified as IC at the time of diagnosis between years 2000 - 2007, were identified and reevaluated for disease course in 2014 after a mean surveillance follow-up of 8.7±3.7 (range, 4-14) years in order to identify the rates of diagnosis resolution to UC or CC. Diagnosis for each patient was determined based on standard clinical and pathologic features as described in the diagnostic criteria in the methods section. 18,21 Three gastrointestinal pathologists blinded to clinical diagnosis reconciled and confirmed colitis diagnosis for each patient and represented a consensus among treating physicians. Patients who clinically did not change and maintained the IC diagnosis were molecularly tested for IBD phenotype precision.

cDNA microarray:

Whole-transcriptome microarray with RNA extracted and pooled from human full thickness colon samples from UC and CC patients (n = 5/group) (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) as previously described. 22,23

nCounter gene expression:

_RNA from experimental and control cell was processed following NanoString (NanoString Technologies Inc., Seattle, WA) recommended procedure to determine gene expression level according to the manufacturer protocol. 20,24

Real-Time RT-PCR:

qPCR was used to measure transcript levels of DEFA5 and MMP-7 for MicroRNA signatures to differentiate CC from UC as previously described. 5, 25,26,27 RNA was extracted from three human colon biopsy samples from moderate UC and CC and diverticulitis (DV) as a non-IBD control (RNeasy Miniprep Kit, Qiagen, CA). cDNA was generated using iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Predesigned TaqMan probes (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) were purchased for HD5, MMP-7, and GAPHD control and all samples were run in triplicate using a CFX96 real-time PCR thermocycler (Bio-Rad). Data were analyzed according to the ΔΔC† method of analysis.

Western blot and immunohistochemistry:

Western blot was utilized to assess any differences of DEFA5 and MMP-7 at the protein level as previously described (28) (29). Protein was extracted from a minimum of 10 colon biopsy samples from mild, moderate, and severe UC; mild, moderate, and severe CC; and non-IBD DV control. Whole cell lysates were extracted from full-thickness colon samples using T-PER (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Bradford Assays (Bio-Rad) were run to determine protein concentration, and protein was loaded onto a 4-20% SDS-PAGE tris/glycine gel (Bio-Rad). Proteins were transferred to PVDF (Bio-Rad) and western blots for DEFA5, Pro-MMP-7, and β-actin loading control were performed with primary and secondary antibodies (Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Blots were visualized with Opti-4CN colorimetric detection kit (Bio-Rad) and imaged with ChemiDoc XRS+ imaging system (Bio-Rad). Band intensities were measured and data analysis performed with Image Lab Software (Bio-Rad).

Five colon tissue protein extracts and staining of DEFA5 per disease by IHC was done as previously described. Quantification of DEFA5 staining was analyzed manually by microscopy / automatically quantified using Nikon's Eclipse Ti microscope with built-in NIS-Elements Advanced Research software (NEARAS). 22,28

NEARAS Technology for Quantification of IHC Staining:

Nikon Elements Advanced Research Software (NEARAS) (Melville, NY) was used to manually calculate the number of cells with DEFA5 staining in IHC tissue slides. 22,28 A mean intensity threshold of 20 to 255 intensity units was established to eliminate a false positive signal from background staining. A circularity parameter of 0.5 to 1 and equivalent diameter of 5-15 micrometer was used to select for cells. All threshold parameters were used in each image to count the number of DEFA5 positive cells in tissue samples.

Statistical analysis:

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism v6 software (30) qRT-PCR, IHC DEFA5 counts, and DEFA5 vs. MMP-7 protein analysis was examined by applying a two-tailed Student’s t test with the Welch correction, respectively (qRT-PCR and IHC = unpaired; DEFA5 vs. MMP-7 analysis = paired). Western blots were analyzed by ANOVA followed by Fisher’s test for multiple comparisons. For all statistical analyses, p< 0.05 indicated a statistical significance.

Results

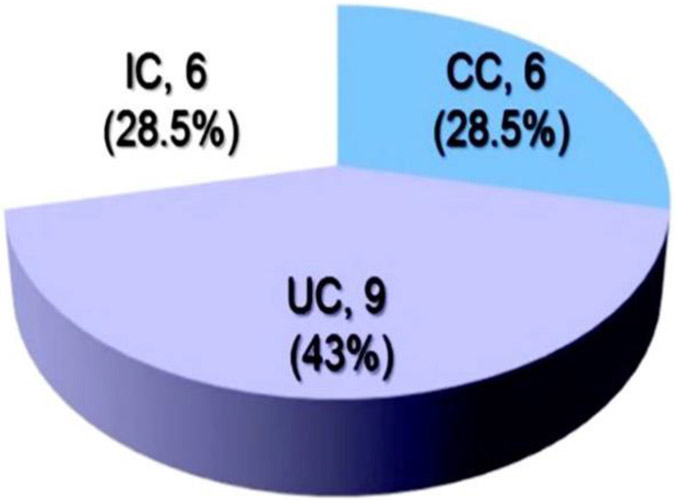

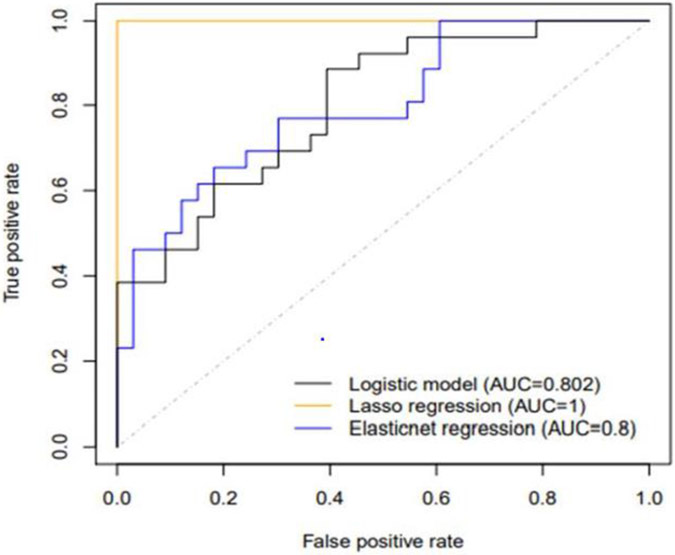

Twenty-one (#21) patients, Table 1 who were diagnosed with IC were reevaluated after a surveillance follow-up period was 8.7±3.7 (range, 4-14) years. Seventy-one percent (#15) of the patient with the original IC diagnosis changed. Forty three percent (# 9) changed to UC and another 28.5% (# 6) to CC, respectively, Table 1 and Fig. 1. Twenty nine percent (# 9) patients remained with the inexact diagnosis of IC, Table 1 and Fig. 1. When the initial biopsies obtained from the 6 unchanged patients were analyzed for DEFA5 IHC NEARAS count profile tests, all reconciled with the final diagnosis chart reviewed in the Database. Among these patients with IC, statistical analysis of DEFA5 was a reliable differentiator to determine positive predictive values (PPV) in patient tissue was 95.8% for CC and only 76.9% for UC, Fig. 2. These data indicate that DEFA5 could be developed into a reliable diagnostic tool to better distinguish CC and UC among IC patient cohort.

Table 1:

Results from patients with the diagnosis of indeterminate colitis samples that were surveyed: Column (i) original diagnosis by a pathologist, (ii) diagnosis by an attending physician (iii) diagnosis using molecular biomarker test, DEFA5 staining (each + represents 100 staining spot counts), and (iv) patient clinical outcomes. Adapted with modification from Williams et al., 5 under the terms of conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license.

| Attending Pathologist Diagnosis |

Attending Gastroenterologist Diagnosis |

Patient Outcomes New Diagnosis |

Mean Area Fraction of DEFA5 (%) NEARES count |

|---|---|---|---|

| IC | IC | CC | 80 |

| IC | UC | UC | 10 |

| IC | UC | UC | 10 (Second opinion) |

| IC | UC | UC | 20 |

| IC | UC | UC | 20 (Second opinion) |

| IC | IC | UC | 20 |

| IC | UC | UC | 20 |

| IC | CC | UC | 10 |

| IC | CC | UC | 10 |

| IC | UC | CC | 70 (Second opinion) |

| IC | UC | CC | 70 |

| IC | UC | UC | 20 |

| IC | CC | CC | 90 |

| IC | IC | CC | 80 |

| IC | CC | CC | 80 |

| IC | UC | UC | 10 |

| IC | CC | CC | 100 |

| IC | UC | UC | 20 |

| IC | CC | CC | 100 |

| IC | IC | UC | 20 |

| IC | IC | CC | 100 |

| IC | IC | UC | 10 |

| IC | UC | UC | 20 |

Fig 1: Depict diagnostic ambiguity, uncertainty and inaccuracy of IC in IBD clinical setting.

A, Twenty-one IC patients were followed for approximately ten years. At the end of the 10 year period, 28.5% of the patients could still not be delineated into a precise diagnosis of either UC or C. Immunohistochemistry staining for DEFA5 agrees with final diagnostic outcome in a sample of IC patients even when there was no agreement with the attending physician. Adapted from Williams et al. 5 under the terms of conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license.

Fig 2:

Statistical analysis to determine positive predictive values (PPVs) of DEF5 in patient tissue are 95.8% for CC and only 76.9% for UC. Chi squared analysis shows significant relatedness between high levels of DEFA5 and a diagnosis of CC (p<0.0001). These data indicate that DEFA5 could be developed into a diagnostic tool to better distinguish CC from UC. This indicates that IC could be circumvented and eradicated for good. Adapted from Williams et al. 5 under the terms of conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license.

Discussion

Diagnostic ambiguity and delay among IBD patients with IC has remained a major challenge in endoscopic medicine 31,32,33,34,35 and colorectal surgery. 36,37,38 The central medical challenge is the discrimination of inexact IC diagnosis into the specific IBD subtypes (UC or CC) with accuracy, as it affects surgical care of patients. 36,37,38 Experiences reveals 28.5% of patients with inexact IC diagnosis still retained their IC diagnosis after a mean follow-up period of 8.7±3.7 years (range: 4-14), Fig. 2B (5) (39). Diagnosis of IC into accurate diagnosis of authentic UC or CC is of paramount importance when determining a patient’s candidacy for pouch surgery, the RPC-IPAA. Further, incorrect diagnosis and treatment carry potential morbidity from inappropriate and unnecessary surgery and cost. The overall colonic IBD diagnosed as IC has not changed over the past 60 years, revealing persistent diagnostic uncertainty, thereby confounding effective therapies. 5, 27

A standard surgical procedure for treating UC, RPC-IPAA typically does not benefit and can be harmful to most CC patients because of higher rates of pouch failure. Therefore, it is important for surgeons to choose the appropriate treatment for their IBD patients 40, 41, especially IC into authentic UC or CC. Unfortunately, current methods for diagnosing colonic IBD are painstakingly inaccurate and have not changed over 60 years. 42,43 Up to 15% of IBD cases are classified as IC when the established criteria for UC and CC are non-definitive. 5,43 In another 15% of IBD cases, authentic CC is not evident prior to colectomy. 1, 44 Therefore, a total of 30% of colonic IBD patients are not accurately diagnosed in a timely manner. 1,44 Much of the diagnostic uncertainty arises from overlapping features that make CC appear like UC. 45,46 Key differences in tissue inflammation, damage, and prognosis, which suggest distinctive etiopathogenic processes and mechanisms responsible for their respective features, can clinically and histologically be challenging to interpret. 43,47 Intestinal wall thickening is segmental in CC but continuous in UC. 45,48 UC causes inflammation and ulceration of the mucosal and, to a lesser degree, the submucosae linings of the colon and rectum. 45 Furthermore, CC differs from UC in that it may cause inflammation deeper within the four colonic layers (transmural inflammation and skip lesions). 49,50 CC may also affect other organs through fistulation. 49,50 Unfortunately, during the prodromal stages of the disease, all these features are obscure in 30% of cases confounding the treatment regimens. 45,46 The surgical treatment options and indications for UC and CC differ significantly; for instance, UC patients need to undergo RPC-IPAA for cure which largely is contraindicated in patients with CC. 6,51,52 Therefore, it is important to accurately identify the IBD subtypes UC or CC and categorize inexact diagnosis of IC into authentic either UC or CC when determining a patient’s candidacy for RPC-IPAA surgery.

To circumvent the diagnosis ambiguity and delay in IBD clinical setting we analyzed colonic surgical pathology samples of patients with unambiguous CC and UC undergoing colectomy in connection with RPC. 3,4 We identified and compared those protein profiles which had the necessary (i) specificity; (ii) sensitivity; (iii) discriminatory; and (iv) predictive capacity to determine the heterogeneity of IBD. 3,4 These molecules are independent of tissue (mucosa, submucosa, or both) and appear to represent a disease-specific marker. 3,4. Further, in this study, we were able to molecularly delineate UC and CC with molecular signatures of DEFA5 using IHC and quantified by NEARAS.

To date, there is no diagnostic “Gold standard” tool for IBD. Differentiating UC and CC among patients with IC has remained a major challenge in endoscopic medicine. 53,54 Patients with CC are mistakenly diagnosed and RPC-operated as definitive UC in 15% of IBD patients because of overlap in the clinical findings. 13,55,56,57 Further, most IC patients who undergo RPC for presumed UC, are subsequently found to develop a recurrent de novo Crohn’s ileitis in the ileal pouch. 13,58 This is a serious consequence that may hinder the restoration of intestinal continuity and its intractable nature leads to subsequent pouch failure, 7,8,59 often requiring pouch diversion or excision with a permanent terminal-ileostomy. 13,56,60,61,62,63,64,65 This has negative psycho-sociological implications and poorer quality of life. 60,66

Curative treatment for UC is often surgical. 67 Success of RPC surgery is largely dependent on careful patient selection combined with meticulous surgical technique and diagnostic accuracy. 68 Available clinical presentations and experience to date suggest that it is difficult to identify patients with CC who are likely to have a successful outcome after RPC surgery. 13,56 However, in a highly selected patient with CC, RPC has been indicated. 69 Our biomolecular marker model may ultimately be used to select those patients with CC who are potential candidate for this sphincter preserving operation, RPC. Thus, RPC operation may be considered and should remain a careful option for certain subgroup of patients with CC, 69 but an acceptable care option for patients with UC and for those IC patients who are predicted to develop UC. 6,70

UC and CC share many demographic and clinical features yet present significant differences in tissue inflammation and damage, suggesting a distinct etiopathogenic trigger. 71 Currently, little is known about the molecular differences distinguishing UC and CC. 3,4 Trends in the IBD field focus on genetic susceptibility, role of normal flora, inflammatory processes, and interactions between normal flora and the immune response. 72 Even though current research is promising, there have been no definitive answers to date to help clinicians differentiate between the two diseases when current diagnostics prove inadequate and result in a diagnosis of IC. As incidence and prevalence of IBD increases across the world, it is becoming even more important to find molecular markers of disease to accurately distinguish between CC and UC. 3,4 Our studies led to the discovery of DEFA5 as a potential biomarker for CC and that may be a diagnostic signature that may efficiently distinguish CC from UC as “Gold Standard” tool in IBD phenotype precision. In addition to a novel diagnostic indicator for IBDs, we also propose a dysregulation in the activation of DEFA5 in IBD. Due to the low levels of MMP-7 in moderate and severe CC, it is possible that DEFA5 is remaining localized in the tissue in its inactive form, which could be cause for an increase in damage to the epithelial lining and potentially even a dysregulation in the levels and make-up of gut flora. Future studies will also focus on discovering if there is a causative relationship of these two proteins.

Contrary, in line with the discussed data herewith presented, it is evidently observed in a newly assembled cohort that patients with “Crohn’s ileitis (CI)” are characterized with a deficiency of DEFA5, (73) as shown by a reduced expression and secretion of the Paneth cell defensing DEFA and, is a fundamental feature of CI. In Crohn’s colitis (CC), mutually opposed, the reverse is true. We found DEFA5 to be the most predominantly expressed antimicrobial peptide. Lawrance at al. 14 had similar observation when they examined global gene expression profiles of inflamed colonic tissue using DNA microarrays. The results identified several genes with altered expression between UC and CD. DEFA5 gene was the most highly expressed in CD. Unfortunately, MMP-7 was not mentioned but MMP-1, 3 and 12 transcripts were significantly higher in UC than the control (p < 0.05). The definitive CC and CI diseases do not share demographic and clinical features and/or molecular biometrics of tissue inflammation and damage suggesting distinct etiology and mechanisms. This is intriguing and needs further elucidation. These studies have reconciled all IC patient samples into authentic either UC or CC using DEFA5 and patient outcomes, Table 1 and Fig. 1.

Early timely diagnosis accuracy leads to appropriate therapeutic options and will aid in determining candidates for RPC-IPAA and avoid unnecessary surgeries. 13,56 We have identified that DEFA5 can differentiate CC and UC amomg IC patients with the first clinic visit endoscopy biopsy without ambiguity or delay. Overall, significant differences in expression profiles of 546 genes identified CC and UC as distinct molecular entities and as yet unexplored pathobiologies and IBD-predisposing candidate genes. 5

Conclusion

DEFA5 expressed differentially in IBD and that aberrant expression, localization, and/or activation of DEFA5 underlies the tissue inflammation and damage associated with authentic CC form of colitis. DEFA5 is a reliable signature to distinguishCC from UC among IC patient cohort. It is promosing to use DEFA5 to determine patient candidacy for RPC-IPAA surgery.

Limitation

The high degree of similarity of DEFAs implies that antibodies against DEFA5 may not be specific enough to distinguish DEFA5 from other DEFAs. The rate limiting step is the generation of monoclonal antibodies to the DEFA5 peptides. We are confident that antibodies against the segments of DEFA5, dones 1A8 and 4FD will be successful. 74,75, 76 We have verified that the antibodies used to generate the data (DEFA5 – Sigma HPA015775) were indeed directed against DEFA5.

Acknowledgements

Support: Research Foundation, American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, Limited Project Grant (LPG-086); NIH/NIDDK R21DK095186; 3U54 CA091408–09S1; U54RR026140; U54MD007593; UL1 RR024975. NIH/grants U54 MD007593, G12 MD007586, U54 CA163069, R24 DA036420, and S10 RR0254970.

The authors are thankful to CRA, from the Meharry Research Concierge Services (supported by NIH grants U54MD007593 and UL1TR000445) for comments, suggestions and for language editing; J. Shawn Goodwin, Ph.D., for guidance in NEARAS microscopy; Jeremy Norris, Ph.D., for guidance in managing FFPE samples and for critical reading of manuscript for intellectual content; Jon H. Lowrance, Ph.D., for critical reading and comments for intellectual content.

Abbreviations

- IBD

inflammatory bowel disease

- IC

Indeterminate colitis

- UC

Ulcerative colitis

- CC

Crohn’s colitis

- CD

Crohn's disease

- CI

Crohn’s ileitis

- DV

Diverticulitis

- NEARAS

Nikon Element Advance Research Analysis Software

- RPC

restorative proctocolectomy

- IPAA

ileal pouch-anal anastomosis

- H & E

hematoxylin and eosin

- HD5

Human Defensin 5α

- ROC

receiver operator characteristic

- MMC

Meharry Medical College

- VU

Vanderbilt University

- VUMC

Vanderbilt University Medical Center

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None

Writing Assistance: None

Conference presentation: Presented, in part, at The Annual Congress of The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, Hollywood, Florida May 2–6, 2009, Receiving Award for best Basic Science Poster Presentation, The New Jersey Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons; at Annual Congress of The Digestive Disease Week, New Orleans, LA, May 2–5, 2010; at The Annual Congress of The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, Minneapolis, MN, May 15–19, 2010; at The 102nd Annual Congress, the American Association for Cancer Research, Orlando Florida 2–6 April, 2011; at the Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities Conference, Bethesda North, Rockville, MD, July 12–15, 2011; at NCI Translational Science Conference “From Molecular Information to Cancer Medicine”, Washington, DC, July 28–29, 2011; at The 103nd Annual Congress, the American Association for Cancer Research, Chicago, IL 31 March– 4 April, 2012; at AACR Special Conference on Molecular Targeted Therapies: Mechanisms of Resistance, San Diego, CA May 9–12, 2012; at the Fifth AACR Conference on The Science of Cancer Health Disparities San Diego, CA October 27–30, 2012; at The Annual congress of The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, 30 April–4 May, 2016, Receiving Award for Best Clinical Podium Presentation, The New England Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, Los Angeles, CA; at Keystone Symposia on Molecular and Cellular Biology, Host and the Environment in IBD: Scientific Advances Leading to New Therapeutics (A2), Taos, New Mexico, Jan 13–17, 2019; The Annual Scientific Meeting, The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, Tampa, Florida April 30–May 4, 2022 and The annual Scientific Meeting, The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, Seattle, Washington, June 3–6, 2023.

Category: Colonic Inflammatory Bowel Disease (the colitides)

References

- 1.Burakoff R Indeterminate colitis: clinical spectrum of disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38(5 Suppl 1):S41–3. DOI: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000123991.13937.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carvalho RS, Abadom V, Dilworth HP, Thompson R, Oliva-Hemker M, Cuffari C. Indeterminate colitis: a significant subgroup of pediatric IBD. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2006;12(4):258–62. DOI: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000215093.62245.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.M'Koma AE, Seeley EH, Washington MK, Schwartz DA, Muldoon RL, Herline AJ, Wise PE, Caprioli RM. Proteomic profiling of mucosal and submucosal colonic tissues yields protein signatures that differentiate the inflammatory colitides. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17(4):875–83. DOI: 10.1002/ibd.21442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seeley EH, Washington MK, Caprioli RM, M'Koma AE. Proteomic patterns of colonic mucosal tissues delineate Crohn's colitis and ulcerative colitis. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2013;7(7-8):541–9. DOI: 10.1002/prca.201200107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams AD, Korolkova OY, Sakwe AM, Geiger TM, James SD, Muldoon RL, et al. Human alpha defensin 5 is a candidate biomarker to delineate inflammatory bowel disease. PloS one. 2017;12(8):e0179710. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.M'Koma AE, Wise PE, Muldoon RL, Schwartz DA, Washington MK, Herline AJ. Evolution of the restorative proctocolectomy and its effects on gastrointestinal hormones. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22(10):1143–63. DOI: 10.1007/s00384-007-0331-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shen B, Remzi FH, Brzezinski A, Lopez R, Bennett AE, Lavery IC, et al. Risk factors for pouch failure in patients with different phenotypes of Crohn's disease of the pouch. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2008;14(7):942–8. DOI: 10.1002/ibd.20409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shen B, Remzi FH, Lavery IC, Lashner BA, Fazio VW. A proposed classification of ileal pouch disorders and associated complications after restorative proctocolectomy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6(2):145–58. DOI: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ricardo AP, Kayal M, Plietz MC, Khaitov S, Sylla P, Dubinsky MC, et al. Predictors of pouch failure: A tertiary care inflammatory bowel disease centre experience. Colorectal Dis. 2023. DOI: 10.1111/codi.16589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shen B. Crohn's disease of the ileal pouch: reality, diagnosis, and management. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2009;15(2):284–94. DOI: 10.1002/ibd.20661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malaty HM, Mehta S, Abraham B, Garnett EA, Ferry GD. The natural course of inflammatory bowel disease-indeterminate from childhood to adulthood: within a 25 year period. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2013;6:115–21. DOI: 10.2147/CEG.S44700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malaty HM, Fan X, Opekun AR, Thibodeaux C, Ferry GD. Rising incidence of inflammatory bowel disease among children: a 12-year study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;50(1):27–31. DOI: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181b99baa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keighley MR. The final diagnosis in pouch patients for presumed ulcerative colitis may change to Crohn's disease: patients should be warned of the consequences. Acta Chir Iugosl. 2000;47(4 Suppl 1):27–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lawrance IC, Fiocchi C, Chakravarti S. Ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease: distinctive gene expression profiles and novel susceptibility candidate genes. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10(5):445–56. DOI: 10.1093/hmg/10.5.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang C, Shen M, Gohain N, Tolbert WD, Chen F, Zhang N, et al. Design of a potent antibiotic peptide based on the active region of human defensin 5. J Med Chem. 2015;58(7):3083–93. DOI: 10.1021/jm501824a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chileveru HR, Lim SA, Chairatana P, Wommack AJ, Chiang IL, Nolan EM. Visualizing attack of Escherichia coli by the antimicrobial peptide human defensin 5. Biochemistry. 2015;54(9):1767–77. DOI: 10.1021/bi501483q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson CL, Schmidt AP, Pirila E, Valore EV, Ferri N, Sorsa T, et al. Differential Processing of {alpha}- and {beta}-Defensin Precursors by Matrix Metalloproteinase-7 (MMP-7). J Biol Chem. 2009;284(13):8301–11. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M809744200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vandenbroucke RE, Vanlaere I, Van Hauwermeiren F, Van Wonterghem E, Wilson C, Libert C. Pro-inflammatory effects of matrix metalloproteinase 7 in acute inflammation. Mucosal Immunol. 2014;7(3):579–88. DOI: 10.1038/mi.2013.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mastroianni JR, Costales JK, Zaksheske J, Selsted ME, Salzman NH, Ouellette AJ. Alternative luminal activation mechanisms for paneth cell alpha-defensins. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(14):11205–12. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M111.333559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Puri KS, Suresh KR, Gogtay NJ, Thatte UM. Declaration of Helsinki, 2008: implications for stakeholders in research. J Postgrad Med. 2009;55(2):131–4. DOI: 10.4103/0022-3859.52846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cook MG, Dixon MF. An analysis of the reliability of detection and diagnostic value of various pathological features in Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1973;14(4):255–62. DOI: 10.1136/gut.14.4.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Antonatos C, Panoutsopoulou M, Georgakilas GK, Evangelou E, Vasilopoulos Y. Gene Expression Meta-Analysis of Potential Shared and Unique Pathways between Autoimmune Diseases under Anti-TNFalpha Therapy. Genes (Basel). 2022;13(5). DOI: 10.3390/genes13050776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schaudy E, Lietard J, Somoza MM. Enzymatic Synthesis of High-Density RNA Microarrays. Curr Protoc. 2023;3(2):e667. DOI: 10.1002/cpz1.667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Novianti PW, Jong VL, Roes KC, Eijkemans MJ. Factors affecting the accuracy of a class prediction model in gene expression data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2015;16:199. DOI: 10.1186/s12859-015-0610-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Atanassova A, Georgieva A. Circulating miRNA-16 in inflammatory bowel disease and some clinical correlations - a cohort study in Bulgarian patients. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2022;26(17):6310–5. DOI: 10.26355/eurrev_202209_29655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schaefer JS, Attumi T, Opekun AR, Abraham B, Hou J, Shelby H, et al. MicroRNA signatures differentiate Crohn's disease from ulcerative colitis. BMC immunology. 2015;16:5. DOI: 10.1186/s12865-015-0069-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams AD, Sakwe AM, D Smoot DT, Washington MK, Ballard BR, Geiger TM, M'Koma AE. Indeterminate Colitis Precision into Crohn's Colitis and Ulcerative Colitis Using Molecular Biometrics. Dis Colon Rectum 2016;59(5):E92–E93. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Myers JN, Schaffer MW, Korolkova OY, Williams AD, Gangula PR, M'Koma AE. Implications of the Colonic Deposition of Free Hemoglobin-alpha Chain: A Previously Unknown Tissue By-product in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20(9):1530–47. DOI: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gmyr V, Bonner C, Lukowiak B, Pawlowski V, Dellaleau N, Belaich S, et al. Automated digital image analysis of islet cell mass using Nikon's inverted eclipse Ti microscope and software to improve engraftment may help to advance the therapeutic efficacy and accessibility of islet transplantation across centers. Cell Transplant. 2015;24(1):1–9. DOI: 10.3727/096368913X667493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, Gatsonis CA, Glasziou PP, Irwig L, et al. STARD 2015: an updated list of essential items for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies. Bmj. 2015;351:h5527. DOI: 10.1373/clinchem.2015.246280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ricciuto A, Fish JR, Tomalty DE, Carman N, Crowley E, Popalis C, et al. Diagnostic delay in Canadian children with inflammatory bowel disease is more common in Crohn's disease and associated with decreased height. Arch Dis Child. 2018;103(4):319–26. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2017-313060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ricciuto A, Mack DR, Huynh HQ, Jacobson K, Otley AR, deBruyn J, et al. Diagnostic Delay Is Associated With Complicated Disease and Growth Impairment in Paediatric Crohn's Disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2021;15(3):419–31. DOI: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjaa197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jackson KL, Stocchi L, Duraes L, Rencuzogullari A, Bennett AE, Remzi FH. Long-Term Outcomes in Indeterminate Colitis Patients Undergoing Ileal Pouch-Anal Anastomosis: Function, Quality of Life, and Complications. J Gastrointest Surg. 2017;21(1):56–61. DOI: 10.1007/s11605-016-3306-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Novacek G, Grochenig HP, Haas T, Wenzl H, Steiner P, Koch R, et al. Diagnostic delay in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in Austria. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2019;131 (5-6):104–12. DOI: 10.1007/s00508-019-1451-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology H, Nutrition, Colitis Foundation of A, Bousvaros A, Antonioli DA, Colletti RB, et al. Differentiating ulcerative colitis from Crohn disease in children and young adults: report of a working group of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition and the Crohn's and Colitis Foundation of America. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;44(5):653–74. DOI: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31805563f3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murrell ZA, Melmed GY, Ippoliti A, Vasiliauskas EA, Dubinsky M, Targan SR, et al. A prospective evaluation of the long-term outcome of ileal pouch-anal anastomosis in patients with inflammatory bowel disease-unclassified and indeterminate colitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52(5):872–8. DOI: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e31819f5d4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Melton GB, Kiran RP, Fazio VW, He J, Shen B, Goldblum JR, et al. Do preoperative factors predict subsequent diagnosis of Crohn's disease after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for ulcerative or indeterminate colitis? Colorectal Dis. 2010;12(10):1026–32. DOI: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.02014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sagar PM, Dozois RR, Wolff BG. Long-term results of ileal pouch-anal anastomosis in patients with Crohn's disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39(8):893–8. DOI: 10.1007/BF02053988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rana T, Korolkova OY, Rachakonda G, Williams AD, Hawkins AT, James SD, et al. Linking bacterial enterotoxins and alpha defensin 5 expansion in the Crohn's colitis: A new insight into the etiopathogenetic and differentiation triggers driving colonic inflammatory bowel disease. PloS one. 2021;16(3):e0246393. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246393. eCollection 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lightner AL, Jia X, Zaghiyan K, Fleshner PR. IPAA in Known Preoperative Crohn's Disease: A Systematic Review. Dis Colon Rectum. 2021;64(3):355–64. DOI: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000001918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lavryk OA, Stocchi L, Shawki S, Aiello A, Church JM, Steele SR, et al. Redo IPAA After a Failed Pouch In Patients With Crohn's Disease: Is It Worth Trying? Dis Colon Rectum. 2020;63(6):823–30. DOI: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000001644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ananthakrishnan AN, Kwon J, Raffals L, Sands B, Stenson WF, McGovern D, et al. Variation in treatment of patients with inflammatory bowel diseases at major referral centers in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(6):1197–200. DOI: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tremaine WJ. Is indeterminate colitis determinable? Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2012;14(2):162–5. DOI: 10.1007/s11894-012-0244-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brown CJ, Maclean AR, Cohen Z, Macrae HM, O'Connor BI, McLeod RS. Crohn's disease and indeterminate colitis and the ileal pouch-anal anastomosis: outcomes and patterns of failure. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48(8):1542–9. DOI: 10.1007/s10350-005-0059-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Conrad K, Roggenbuck D, Laass MW. Diagnosis and classification of ulcerative colitis. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13(4-5):463–6. DOI: 10.1016/j.autrev.2014.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Laass MW, Roggenbuck D, Conrad K. Diagnosis and classification of Crohn's disease. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13(4-5):467–71. DOI: 10.1016/j.autrev.2014.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tremaine WJ. Review article: Indeterminate colitis--definition, diagnosis and management. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25(1):13–7. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jevon GP, Madhur R. Endoscopic and histologic findings in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2010;6(3):174–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nosti PA, Stahl TJ, Sokol AI. Surgical repair of rectovaginal fistulas in patients with Crohn's disease. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;171(1):166–70. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2013.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nielsen OH, Rogler G, Hahnloser D, Thomsen OO. Diagnosis and management of fistulizing Crohn's disease. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;6(2):92–106. DOI: 10.1038/ncpgasthep1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.M'Koma AE. Serum biochemical evaluation of patients with functional pouches ten to 20 years after restorative proctocolectomy. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2006;21(7):711–20. DOI: 10.1007/s00384-005-0076-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.M'Koma AE. Observation on essential biochemical data profile in connection with restorative proctocolectomy in humans. Vitamin B12 and fat absorption cited. Dissertation Thesis. 2001:1–126. URI: http://hdl.handle.net/10616/38656 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee H, Westerhoff M, Shen B, Liu X. Clinical Aspects of Idiopathic Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Review for Pathologists. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016;140(5):413–28. DOI: 10.5858/arpa.2015-0305-RA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.M'Koma AE. Diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease: Potential role of molecular biometrics. World J gastrointest surg. 2014;6(11):208–19. DOI: 10.4240/wjgs.v6.i11.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Feakins RM. Ulcerative colitis or Crohn's disease? Pitfalls and problems. Histopathology. 2014;64(3):317–35. DOI: 10.1111/his.12263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wagner-Bartak NA, Levine MS, Rubesin SE, Laufer I, Rombeau JL, Lichtenstein GR. Crohn's disease in the ileal pouch after total colectomy for ulcerative colitis: findings on pouch enemas in six patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184(6):1843–7. DOI: 10.2214/ajr.184.6.01841843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Price AB. Overlap in the spectrum of non-specific inflammatory bowel disease--'colitis indeterminate'. J Clin Pathol. 1978;31(6):567–77. DOI: 10.1136/jcp.31.6.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mortellaro VE, Green J, Islam S, Bass JA, Fike FB, St Peter SD. Occurrence of Crohn's disease in children after total colectomy for ulcerative colitis. J Surg Res. 2011;170(1):38–40. DOI: 10.1016/j.jss.2011.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tulchinsky H, Hawley PR, Nicholls J. Long-term failure after restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis. Ann Surg. 2003;238(2):229–34. DOI: 10.1097/01.sla.0000082121.84763.4c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tan HT, Morton D, Connolly AB, Pringle W, White M, Keighley MR. Quality of life after pouch excision. Br J Surg. 1998;85(2):249–51. DOI: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00582.x.61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Meucci G, Bortoli A, Riccioli FA, Girelli CM, Radaelli F, Rivolta R, et al. Frequency and clinical evolution of indeterminate colitis: a retrospective multi-centre study in northern Italy. GSMII (Gruppo di Studio per le Malattie Infiammatorie Intestinali). Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;11(8):909–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jong VL, Novianti PW, Roes KC, Eijkemans MJ. Selecting a classification function for class prediction with gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2016, 15;32(12):1814–22. DOI: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Deutsch AA, McLeod RS, Cullen J, Cohen Z. Results of the pelvic-pouch procedure in patients with Crohn's disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1991;34(6):475–7. DOI: 10.1007/BF02049932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Grobler SP, Hosie KB, Affie E, Thompson H, Keighley MR. Outcome of restorative proctocolectomy when the diagnosis is suggestive of Crohn's disease. Gut. 1993;34(10):1384–8. DOI: 10.1136/gut.34.10.1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mylonakis E, Allan RN, Keighley MR. How does pouch construction for a final diagnosis of Crohn's disease compare with ileoproctostomy for established Crohn's proctocolitis? Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44(8):1137–42. DOI: 10.1007/BF02234634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Das P, Smith JJ, Tekkis PP, Heriot AG, Antropoli M, John Nicholls R. Quality of life after indefinite diversion/pouch excision in ileal pouch failure patients. Colorectal Dis. 2007;9(8):718–24. DOI: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2007.01216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fornaro R, Caratto M, Barbruni G, Fornaro F, Salerno A, Giovinazzo D, et al. Surgical and medical treatment in patients with Acute Severe Ulcerative Colitis. J Dig Dis. 2015;16(10):558–67. DOI: 10.1111/1751-2980.12278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ikeuchi H, Nakano H, Uchino M, Nakamura M, Noda M, Yanagi H, et al. Safety of one-stage restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48(8):1550–5. DOI: 10.1007/s10350-005-0083-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Le Q, Melmed G, Dubinsky M, McGovern D, Vasiliauskas EA, Murrell Z, et al. Surgical outcome of ileal pouch-anal anastomosis when used intentionally for well-defined Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19(1):30–6. DOI: 10.1002/ibd.22955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cohan JN, Ozanne EM, Sewell JL, Hofer RK, Mahadevan U, Varma MG, et al. A Novel Decision Aid for Surgical Patients with Ulcerative Colitis: Results of a Pilot Study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2016;59(6):520–8. DOI: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Podolsky DK. Inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(6):417–29. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMra020831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Corfield AP, Wallace HM, Probert CS. The molecular biology of inflammatory bowel diseases. Biochem Soc Trans. 2011;39(4):1057–60. DOI: 10.1042/BST0391057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Courth LF, Ostaff MJ, Mailander-Sanchez D, Malek NP, Stange EF, Wehkamp J. Crohn's disease-derived monocytes fail to induce Paneth cell defensins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(45):14000–5. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1510084112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.MKoma AE, inventor; Meharry Medical College, assignee. Methods for diagnosing and treating inflammatory bowel disease. United States of America Patent 11,427,852. 2022. https://patents.google.com/patent/US11427852B2/en

- 75.M'Koma AE, Sakwe AM, inventors; Meharry Medical College, assignee. Targeted HD5 antibody and assay methods for diagnosing and treating inflammatory bowel disease. United States of America Patent App 16/622,259. 2021. https://patents.google.com/patent/WO2018237064A1/en

- 76.M'Koma AE, Sakwe AM, Blum DL, Hawkins AT, Alexander LD, Hildreth JE. eP713 - Clones 1A8 and 4FD Targeted anti-DEFA5 mAbs Sensitive and Specific Immunereactive Bioassays for IBD Diagnostics. American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (ASCRS) Annual Scientific Meeting, Seattle Convention Center, June 3-6, 2023. https://www.eventscribe.net/2023/ASCRS23/fsPopup.asp?efp=UUFJSE5KTVExOTE2Ng&PresentationID=1186777&rnd=0.2277816&mode=presin [Google Scholar]