Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) on cadmium (Cd) fractions and microbial biomass in a calcareous soil spiked with Cd under cultivated (Zea mays L.) and uncultivated regime subject to soil leaching condition. Expanding investigations related to soil–plant interactions on metal-contaminated soils with insights on microbial activity and associated soil toxicity perspective provides novel perspectives on using metal-chelating agents for soil remediation.

Methods

The experimental factors were three levels of Cd contamination (0, 25, and 50 mg kg−1 soil) and three levels of NTA (0, 15, and 30 mmol L−1) in loamy soil under maize-cultured and non-cultured conditions. During the experiment, the adding NTA and leaching processes were performed three times.

Results

The results showed that the amount of leached Cd decreased in cultivated soil compared to uncultivated soil due to partial uptake of soluble Cd by plant roots and changes in Cd fractions in soil, so that Cd leached in Cd50NTA30 was 9.2 and 6.1 mg L−1, respectively, in uncultivated and cultivated soils. Also, Cd leached in Cd25NTA30 was 5.7 and 3.1 mg L−1 respectively, in uncultivated and cultivated soils. The best treatment in terms of chemical and microbial characteristics of the soil with the high percentage of Cd removed from the soil was Cd25NTA30 in cultivated soil. In Cd25NTA30 compared to Cd25NTA0 in cultivated soil, pH (0.25 unit), microbial biomass carbon (MBC, 65.0 mg kg−1), and soil respiration (27.5 mg C-CO2 kg−1 24 h−1) decreased, while metabolic quotient (qCO2, 0.05) and dissolved organic carbon (DOC, 20.0 mg L−1) increased. Moreover, the changes of Cd fractions in Cd25NTA30 in cultivated soil compared to uncultivated soil were as follows; the exchangeable Cd (F1, 0.27 mg kg−1) and Fe/Mn-oxide-bounded Cd (F4, 0.15 mg kg−1) fractions increased, in contrast, carbonate-Cd (F2, 2.67 mg kg−1) and, organically bounded Cd (F3, 0.06 mg kg−1) fractions decreased. NTA had no significant effect on the residual fraction (F5).

Conclusion

The use of NTA, especially in calcareous soils, where most of the Cd is bound to calcium carbonate, was able to successfully convert insoluble fractions of Cd into soluble forms and increase the removal efficiency of Cd in the phytoremediation method. NTA is a non-toxic chelating agent to improve the accumulation of Cd in maize.

Keywords: Available cadmium, Calcium carbonate, Soil remediation, Leaching, Biodegradable chelators

Introduction

In recent years, the potentially toxic elements (PTEs) in the soils are one of the most important concerns due to their toxic effects on agricultural products. Among the pollution of PTEs in soil, Cd is more important due to its high mobility. The Cd accumulates in high quantities in plant leaves, and can easily enter the human food chain [1–3].

The soluble and insoluble forms of Cd in the soil determine the amount of Cd absorbed by the plant or leached from the soil [4]. The mobility and transport of Cd in the soil depend on some factors such as pH, CaCO3, organic matter (OM), etc. [2, 5–9]. In the low pH of the soil, the bioavailability of Cd is high [4] and increases the uptake of Cd by the plant roots or the removal of Cd from the rhizosphere during leaching. In contrast, the adsorption of Cd on the soil particles increases due to the enhancement of the electronegativity of soil particles under high pH conditions [10]. In calcareous soils, one of the most limiting factors in reducing the dissolution of Cd is the presence of high CaCO3 in the soil and the consequent precipitation of Cd with carbonate compounds [11–13]. Besides, the OMs with their hydroxyl and carbonyl groups can also be bound with Cd in the soil to form a stable organic chelate containing Cd, and reduce the mobility of Cd [6, 9, 14].

The rhizosphere is a dynamic environment for plant interactions with soil and microorganisms in altering the availability of heavy metals (HMs). Studies have shown that chelating agents affect soil properties such as pH, organic compounds, and the type and population of microorganisms, thereby increasing the availability of HMs [15, 16]. Microorganisms also increase plant root access to heavy metals and increase their uptake by promoting plant growth [17, 18], so, they are effective in enhancing phytoremediation efficiency.

Phytoremediation is a low-cost technology with a small environmental impact for the remediation of PTEs-contaminated soils [19–21]. According to the report of Cristaldi et al. [22], the phytoremediation method involves a much lower cost compared to the Vitrification, Landfilling, Chemical treatment, and Electrokinetics methods. For example, the cost of phytoremediation to restore a polluted land is estimated at 100,000 euros ha−1, while restoring the same area by physical/chemical methods requires 1–2 million [23].

Maize (Zea mays L.) is widely used in the phytoremediation of Cd in contaminated soils due to its high biomass and Cd accumulation ability [24]. Moreover, it has been reported that the cultivation of energy maize can lead to the production of significant amounts of renewable energy [25]. In this regard, due to the low efficiency of this technology, chelate agents can be applied with plant cultivation, so the choice of a chelator can be one of the most important factors affecting the performance of phytoremediation of PTEs. Some of the chelating agents are ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA), nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA), and ethylenediaminedisuccinic acid (EDDS) [26–28].

The use of chelating agents with low biodegradability such as EDTA and DTPA can significantly enhance PTEs accumulation in plants, but cause contamination in the soil and water due to their high stability and persistence in the environment [27–30]. In contrast, the use of compounds such as NTA and EDDS has drawn more interest among researchers because of their high biodegradability and eco-friendly nature, moreover, they stimulate PTEs uptake by plants and enhance their mobility in soil [26, 31–33]. Studies have shown that NTA is more successful compared to EDDS in refining Cd from marine sediments [34]. NTA with a half-life varying from 2 to 7 days is effectively degradable by the microbial population [35, 36]. In addition, the use of NTA at the farm scale to increase phytoremediation efficiency is economical [37]. These authors reported that NTA is more efficient for Cd removal compared to some organic acids and other chelating agents with low biodegradability [34, 36, 38]. NTA can significantly reduce the amount of Cd absorption by soil particles due to its high reactivity with PTEs in soil [4]. Xie et al. [4] reported that NTA mobilizes exchangeable Cd, Cd bounded to carbonates, and organic matter in Cd-contaminated soil. Also, Song et al. [34] stated that NTA is an organic substance with the carboxyl functional group, so it easily reacts with soil organic matter.

Sharma et al. [39] studied the phytoextraction of soil Cd by using four biodegradable chelators of ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid (EGTA), EDDS, NTA, and citric acid (CA). They reported that Cd toxicity decreased plant growth while using chelates increased Cd accumulation in the plant and reduced the toxic effect of Cd on that. Also, Hai et al. [40] reported that EDTA, EDDS, and NTA effectively increased the absorption of As, Cd, Cu, Pb, and Zn by ryegrass, however, the effect of EDTA in increasing the accumulation of PTEs was greater compared to EDDS and NTA. Moreover, Wang et al. [33] showed that the use of GLDA and NTA was effective in the washing of PTEs, however, they reported that applying a combination of GLDA and NTA was more beneficial compared to the use single of a chelating agent in the remove of PTEs.

In calcareous soils in arid regions, the precipitate of Cd by CaCO3 and high uptake of Cd into soil particles caused by high pH lead to low bioavailability of Cd [41], so, the study of Cd fractions is necessary to determine the effectiveness of phytoremediation in this condition. Based on these results and previous related studies, our study addresses the following questions: (i) does the application of NTA affect the chemical and biological changes of Cd-contaminated calcareous soil? (ii) how does the application of NTA in the soil in maize-cultured and non-cultured conditions affect the soil Cd fractions? Finding the answers to these questions is a solution to the removal of soil Cd from high-risk areas with the help of phytoremediation and indicates the efficacy of NTA in the distribution of soil Cd fractions. Therefore, the aims of this study were to research the chemical fractions and availability of Cd, and some soil properties and microbial activities in a calcareous soil subject to leaching after using NTA in maize cultivation compared to uncultivated soil.

Materials and methods

Soil sampling and preparation of Cd-spiked soil

A soil sample was collected from the top layer (0–30 cm) of the agricultural fields of Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz, Iran. Soil samples were air-dried and passed through a 2 mm sieve and analyzed to measure some physical and chemical properties (Table 1). Detailed information about the area of study and soil characteristics are given in Mehrab et al. [12].

Table 1.

Physical and chemical properties of the studied soil [30]

| Parameter | Clay | Silt | Sand | OM | CCE | pH | ECe | CEC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| unit | (%) | - | (dS m−1) | (cmol+ kg−1) | ||||

| Value | 21.4 | 38.0 | 40.6 | 0.71 | 41.3 | 7.7 | 2.45 | 12.6 |

| Parameter | Total N | Available P | Available K | Total Cd | DTPA-extractable Cd | DTPA-extractable Fe | DTPA-extractable Zn | DTPA-extractable Cu |

| unit | (g kg−1) | (mg kg−1) | ||||||

| Value | 0.6 | 13.5 | 173.2 | 0.55 | 0.20 | 2.54 | 0.51 | 0.73 |

OM, organic matter; CEC, cation exchange capacity; EC, electrical conductivity; CCE, calcium carbonate equivalent; AP, Available P; AK, Available K

The CdCl2.2.5H2O solution was used to prepare artificially Cd-spiked soils at concentrations of Cd 25 and 50 mg kg−1. Detailed information on the preparation of Cd-spiked soils and the incubation period is given in Mehrab et al. [12]. At the end of the incubation period, to extract DTPA-extractable Cd, diethylene-triamine-pentaacetic acid (DTPA) buffered at pH 7.3 was used [42]. The DTPA-extractable Cd as bioavailable Cd of Cd-spiked soils (Cd25 and Cd50) was determined 15.2 and 30.1 mg kg−1, respectively. Concentrated HNO3 and 30% H2O2 were used to digest soil and determine total Cd [43]. Also, Tessier’s method was used to measure Cd chemical fractions in the Cd-spiked soils [44]. This procedure separated the Cd fractions as F1, F2, F3, F4, and F5, which are exchangeable Cd, Cd bound to carbonates, Cd bound to Fe–Mn oxides, Cd bound to OM, and residual fractions, respectively. The concentrations of total Cd, DTPA-extractable Cd, and Cd fractions were determined by atomic absorption (Analytikjena contract AA 300, Germany) with ppm accuracy after dilution of concentrated samples. In the present study, in spiked soils (Cd25 and Cd50) used for the greenhouse experiments, the percentage of Cd in F1, F2, F3, F4, and F5 was 4.5, 67.5, 1.2, 18, and 6%, respectively.

Greenhouse experiments

The present experiment was performed at the greenhouse of Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz, Iran, in a completely randomized design, with a factorial arrangement of treatments. The treatments consisted of 18 treatments in the combination of three factors: (i) Cd-spiked soil with three levels (0, 25, and 50 mg kg−1soil), (ii) NTA application with three levels (0, 15, and 30 mmol per pot), and (iii) soil condition (cultivated and non-cultivated soils). Due to the reports about the high level of Cd contamination in some agricultural soils in Iran [45, 46] and other parts of the world including the Mediterranean region [47, 48], in the present experiment, contaminated soils with high levels of Cd were prepared. In addition, the levels of applied NTA were selected according to phytoremediation experiments in similar soils [49]. For each pot, 8 kg of soil was used and then maize seeds were planted in half of the pots (as the maize cultivation treatments). The pH of NTA solutions (15 and 30 mmol L−1) was severely acidic (pH = 2.5–2.6). The first step of adding NTA solutions to the soil was 4 weeks after cultivation and the other two steps were every two weeks. Also, additional water for Cd leaching was added 7 days after NTA application, and drainage water of irrigation events was collected to measure Cd concentration (by atomic absorption). During the growth period, the plants were kept in the greenhouse at a temperature and humidity of 22 ± 3 and 50 ± 5, respectively. Urea, triple superphosphate, and potassium sulfate fertilizers were used in the soil to supply nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium to the plant. Also, micronutrient elements were used in the form of micro-chelate through foliar spraying according to the needs of the plant during the growth period. After 60 days from the beginning of growth, the plants were cut from 5 mm above the soil surface, and their Cd concentration was determined. A soil sample from the rhizosphere was collected and kept at 4 °C to analyze microbial biomass carbon (MBC) and respiration in the soil. Some details about the fertilizers used and maize growing conditions are given in Mehrab et al. [12]. The non-cultivated pots received the same amount of NTA in the definite time and were also irrigated at the same time as the cultivated pots.

Plant and soil analysis

After washing with distilled water, the plant shoots and roots were oven-dried to analyze Cd in the plant. 1 g plant subsample (shoots and roots) was digested in 10 mL of HNO3 (65%) and 5 mL of H2O2 (30%) [50], and then Cd concentration in the plant was determined by atomic absorption (Analytikjena contract AA 300, Germany).

Also, soil pH was measured in a ratio of soil:deionized water (1:1) [51]. The solution of 0.5 M K2SO4 was used to extract the dissolved organic carbon (DOC) [52]. Also, for determining soil MBC, moist soil was exposed to chloroform for 24 h for removing the fumigant then the soil was extracted with 0.5 M K2SO4 by 30 min of shaking; a non-fumigated control was extracted under the same conditions at the time fumigation commenced [53]. Then, a CHNS analyzer (Vario EL III, Germany) was used to measure DOC and MBC in the extracted solution. Soil respiration was determined by measuring the emission of CO2 from the soil after 24 h incubation at 25 °C [54]. In this method, the tube containing the soil sample was exposed NaOH solution, then, CO2 produced was absorbed in NaOH and quantified by titration with HCl. The qCO2 (metabolic quotient) was calculated with the ratio of soil respiration to MBC [55]. Also, total Cd, DTPA-extractable Cd, and Cd chemical fractions in the soil were determined by the same methods described in section “soil sampling and preparation of Cd-spiked soil”. To determine the recovery rate, a percentage of the total Cd extracted by the five sequential fractions was used. The amount of Cd recovery in cultivated and uncultivated soils was in the range of 82.8–97.1% and 83.7–98.2%, respectively.

Statistical analysis

The SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences—version 16) was used for statistical analysis, and Duncan’s Multiple Range Test (DMRT) at a probability level of 5% was used for the means comparison of treatments. Also, the drawing of graphs was carried out by Excel software.

Results and discussion

Cd uptake by the plant

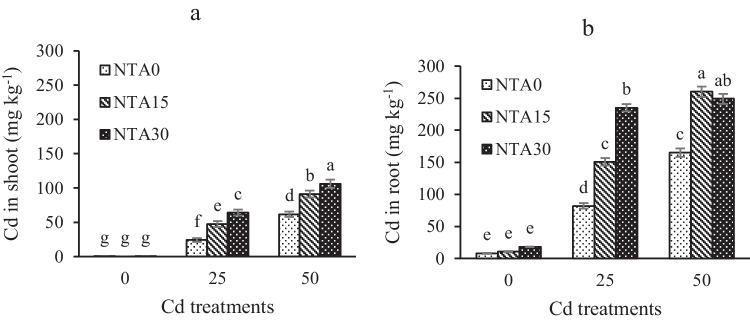

The concentrations of NTA and Cd were effective in increasing the Cd uptake from the soil by plants. The highest concentration of Cd in the plant was observed in Cd50NTA30. The concentration of Cd in the shoot was increased about 100 fold in Cd50NTA30 compared to Cd50NTA0, while this value was 13 fold in the root (Figs. 1a, b). The use of NTA in the soil by increasing the absorbable forms of Cd caused an increase in the accumulation of Cd in plant organs. Studies have shown that the formation of NTA-Cd complexes in Cd-contaminated soil prevents the reabsorption of Cd into soil particles and facilitates the transfer of Cd to the plant roots [4, 21]. Detailed information about the chemical forms and subcellular distribution of Cd in plants after NTA application and the reduction of the dry weight of plant biomass with the increase of Cd concentration in plant tissue is given in Mehrab et al. [12]. Cd concentration in the treatments is shown in Figs. 1a, b. In general, NTA increased the uptake of Cd by the maize and affected the distribution of Cd in plant organs [12].

Fig. 1.

Cd concentration in shoot (a) and root (b) of the plant. Different letters show the significant difference according to Duncan’s test at 5% probability level (Means ± SD, n = 4)

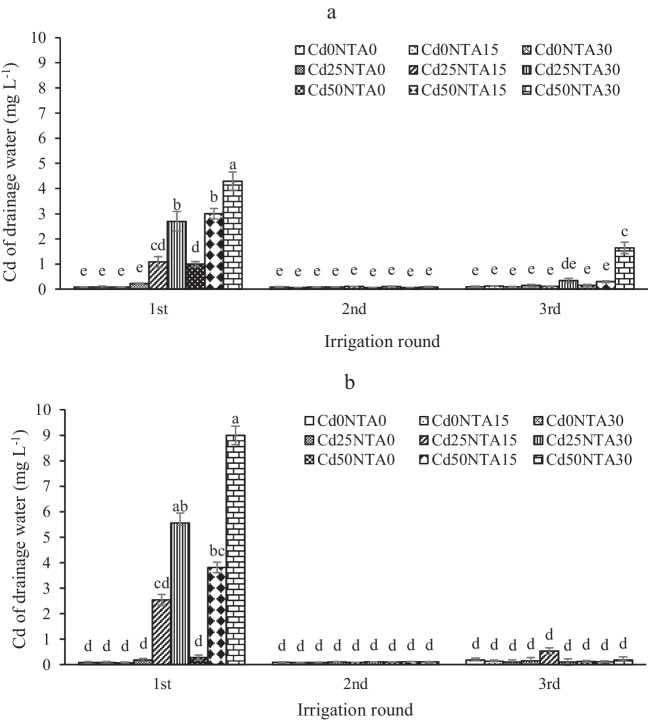

Cd leached from the soil

In general, the highest concentration of leached Cd was observed in the first round of irrigation in both cultivated and uncultivated soils (Figs. 2a, b). In the current study, in the first round of leaching, the highest amount of leached Cd was observed in Cd50NTA30 with 4.3 and 9 mg L−1 in cultivated and uncultivated soils, respectively (Figs. 2a, b), while the total Cd leached in during three rounds of leaching in these treatments was 6 and 9.4 mg L−1, respectively (Figs. 7a, b). Increasing the concentration of soil Cd and NTA used was effective in increasing the leached Cd in the first round of leaching but had no significant effect on leached Cd in the second and third rounds (except for Cd50NA30 at the third round in cultivated soil). Similarly, Zhang and Zhang [56] studied two soils with sandy and loamy textures and reported that increasing the irrigation rounds in the soil reduces the leaching of Cu, Zn, Cd, and Pb. Some detailed information about the effect of maize on the decreased Cd leached is given in Mehrab et al. [12]. According to the results, the uptake of the soluble Cd by plants and the change of Cd fractions distribution due to the plant roots in cultivated soil caused a bit decrease in the concentration of leached Cd in cultivated soil compared to uncultivated soil, however, this difference was not significant (Table 2). In general, NTA leads to an increase in the Cd concentration in the solution phase during leaching. Due to its hydroxyl functional group, NTA can react with the surface of soil particles and releases Cd into the soil solution [4]. In addition, because most of the soluble Cd was removed from the soil in the first round of leaching and less soluble Cd remained in the soil, there was less Cd in the drainage water in the second and third rounds of leaching. Also, the increase of Cd in the drainage water was seen in the third round of leaching in the Cd50NTA30 treatment in the cultivated soil, which is probably due to the change of Cd fraction of the less soluble to more soluble during the growth period of the plant.

Fig. 2.

Cd leached from the cultivated (a) and uncultivated (b) soils. Different letters show the significant difference according to Duncan’s test at 5% probability level (Means ± SD, n = 4)

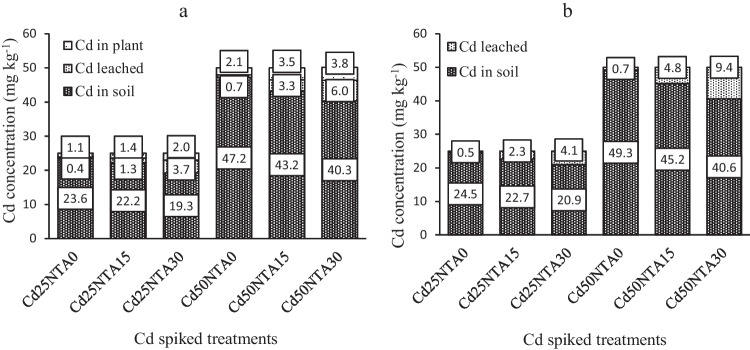

Fig. 7.

The balance of Cd in the soil, drainage water, and plant in cultivated soil (a), and the soil and drainage water in uncultivated soil (b)

Table 2.

The independent-samples t-test results of some properties in the studied soil

| Properties | Mean | Mean Difference | t | Sig. (2-tailed) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultivated soil | Uncultivated soil | ||||

| Cd leached | 1.833 | 2.671 | -0.838 | -0.669 | 0.515 |

| pH | 7.000 | 7.252 | -0.252 | -3.417 | 0.004 |

| DOC | 65.504 | 29.865 | 35.639 | 8.730 | 0.000 |

| MBC | 395.220 | 198.451 | 196.777 | 12.137 | 0.000 |

| Soil respiration | 2.152 | 1.191 | 96.166 | -11.487 | 0.000 |

| qCO2 | 0.545 | 0.601 | -0.056 | -9.443 | 0.000 |

| DTPA-extractable Cd | 5.241 | 7.055 | -1.813 | -0.715 | 0.486 |

| F1 | 0.569 | 0.204 | 0.365 | 2.473 | 0.025 |

| F2 | 9.390 | 13.178 | -3.788 | -0.784 | 0.445 |

| F3 | 0.232 | 0.493 | -0.261 | -2.510 | 0.023 |

| F4 | 8.630 | 5.197 | 3.432 | 1.225 | 0.243 |

| F5 | 1.254 | 1.278 | -0.023 | -0.045 | 0.965 |

DOC, dissolved organic carbon; MBC, microbial biomass carbon; qCO2, metabolic quotient; F1, exchangeable; F2, bound to carbonates; F3, bound to organic matter; F4, bound to iron-manganese oxides; F5, residual fractions

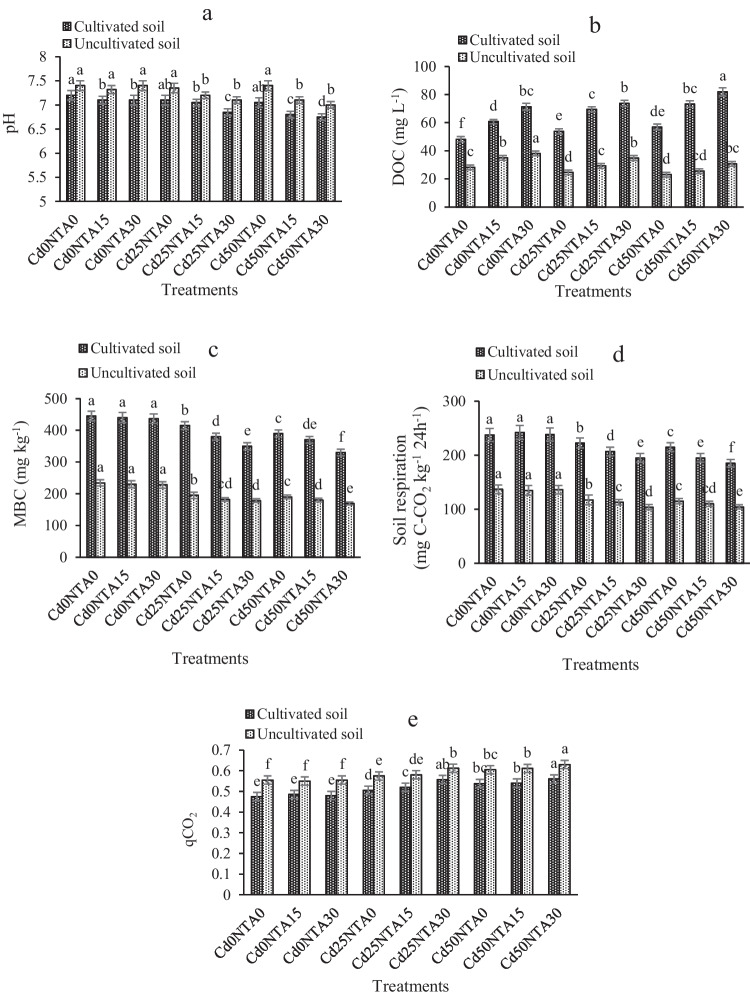

Soil pH and DOC

Soil pH in cultivated soil was significantly lower than that in uncultivated soil, while the amount of DOC was significantly higher in cultivated soil compared to uncultivated soil (Table 2). Soil microorganisms decompose root compounds and secretions [5]. Continuous degradation of these substances by microorganisms leads to an increase in the concentration of organic matter in rhizosphere soils. Therefore, in cultivated soil, the pH decreased and DOC increased. In other studies, an increase in DOC and a decrease in pH have been attributed to plant root secretions [5, 57, 58].

The lowest soil pH was observed in Cd50NTA30. The value of pH in Cd50NTA30 compared to Cd0NTA0 decreased by about 0.45 unit in cultivated soil and 0.25 unit in uncultivated soil (Fig. 3a). It is well known that the properties of the rhizosphere affect the mobility of HMs. After NTA application, the pH of cultivated soil decreased more than the pH of uncultivated soil. That can be attributed to the reaction of plant roots to the increasing concentration of soluble Cd in the soil. The studies have shown by increasing the level of Cd contamination in the rhizosphere of maize, the secretion of some organic acids, especially citrate, as well as exudation of proteins, sugars, and amino acids increased by the plant roots [59, 60]. Also, the reduction of pH can be attributed to the acidic pH of NTA solutions (see section “greenhouse experiments”). Lower soil pH increases Cd mobility. Some studies have reported a decrease in pH after the application of NTA [29] due to the exchange of hydrogen ions in the NTA structure. Li et al. [61] studied the rhizosphere of bean plants and observed that the pH decreased by 1.66 units in the cultivated soil compared to uncultivated soil.

Fig. 3.

pH (a), DOC (b), MBC (c), soil respiration (d) and qCO2 (e) in the soil at the end of experiment. Different letters show the significant difference according to Duncan’s test at 5% probability level (Means ± SD, n = 4)

By adding NTA to the soil, the amount of DOC increased in both cultivated and uncultivated soils. Also, increasing the level of Cd contamination increased DOC in cultivated soil, while Cd contamination decreased DOC in uncultivated soils (Fig. 3b). The highest amount of DOC was observed in cultivated soil in Cd50NTA30 about 82 mg L−1 and in uncultivated soil in Cd0NTA30 about 38 mg L−1 (Fig. 3b). Since the growth and activity of microorganisms, which affect the decomposition of soil organic matter, decrease with increasing levels of HM contamination in the soil [62], so with increasing Cd concentration in the soil DOC concentration was decreased. In contrast, by increasing the level of soil contamination from 25 to 50 mg kg−1 of Cd in the presence of plant roots, the amount of DOC increased, and the pH and MBC decreased. These results can be attributed to the plant's tolerance mechanism to HMs and their reduced uptake.

Also, through the secretion of organic acids by maize roots and the production of complexes of organic acids with Cd, the absorption of Cd by the plant is reduced [5, 63]. Pinto et al. [60] by studying the rhizosphere of maize reported that with increasing Cd contamination in the soil, citrate secretion from maize roots increased and caused the formation of organic Cd complexes, thus reducing the availability of Cd to the plant. An increase in DOC after using NTA and EDTA in the soil was also reported by Meers et al. [64] and Usman et al. [65]. The increase of DOC with the use of chelator can be also attributed to the power of these compounds in the formation of complexes with organic matter. But the most important factor is that NTA is a soluble organic compound, and after the decomposition of NTA in the soil, the amount of DOC measured increases. So, the amount of dissolved organic carbon (DOC) in the soil can indicate the amount of degraded chelate. Meers et al. [64] also used DOC levels in the soil as a proxy of how much chelator is left over time. The findings of Xie et al. [4] in uncultivated soil and Zhang et al. [58] in cultivated soil also showed that the amount of DOC increased with increasing NTA application.

Microbial activities in the rhizosphere

MBC, soil respiration, and qCO2 were considered indicators of microbial activity. The amount of MBC and soil respiration in cultivated soil were significantly higher than that in uncultivated soil, while the amount of qCO2 was significantly lower in cultivated soil than that in uncultivated soil (Table 2). These results can be attributed to the higher concentration of Cd in uncultivated soil compared to cultivated soil, in which Cd toxicity has reduced microbial activity.

In the present study, the interaction of the concentration of Cd and NTA in the soil caused a significant reduction in MBC and soil respiration and a significant increase in qCO2. The amount of MBC and soil respiration were lowest in Cd50NTA30, while qCO2 was highest in Cd50NTA30. The amount of MBC in Cd50NTA30 compared to Cd0NTA0 decreased by 25 and 30% in cultivated and uncultivated soils, respectively (Fig. 3c). These values for respiration were 21 and 24% in cultivated and uncultivated soils, respectively (Fig. 3d). In contrast, the amount of qCO2 in Cd50NTA30 compared to Cd0NTA0 increased 18 and 13% in cultivated and uncultivated soils, respectively (Fig. 3e). The results also showed that NTA didn't have a significant effect on microbial activity, so, NTA alone had no effect on MBC, soil respiration, and qCO2. In contrast, the amount of MBC and soil respiration decreased after the use of NTA in Cd-spiked soil, which can be attributed to the increase in Cd mobility with the application of NTA and causing toxicity.

As observed in the present study, the amount of qCO2 in the soil has increased with higher levels of Cd and NTA application. The amount of qCO2 can change whit changes in substrate, microbial community, or in the physiological status of the microbial community [66]. Studies have shown that the amount of qCO2 is generally higher with increasing of the concentration of HMs in the soil [67, 68] because despite the decrease in microbial biomass and respiration under HM stress, the rate of respiration to microbial biomass increases (qCO2). After increasing the solubility of Cd in soil, Cd can combine with active protein groups and decrease the growth of microorganisms [17, 69, 70]. Few microorganisms are able to grow and maintain activities even under stressful conditions of high PTEs-spiked soil. Therefore, increasing the release of Cd ions in the presence of NTA causes toxicity to some soil microorganisms and inhibits microbial growth and activity. Zhang et al. [58] reported that soil MBC and respiration decreased in the plant rhizosphere in Pb-spiked soil. According to their findings, adding NTA to a Pb-spiked soil decreased MBC and respiration in the soil.

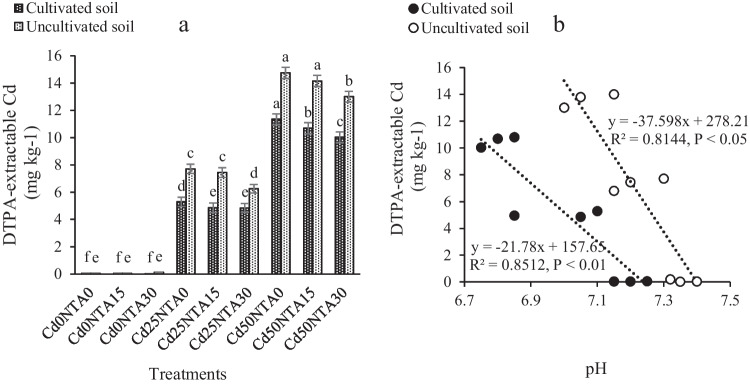

Availability and fractions of Cd in the soil

The maximum amount of DTPA-extractable Cd was observed in Cd50NTA0, while the reduction of DTPA-extractable Cd was observed in Cd50NTA15 and Cd50NTA30 compared to Cd50NTA0 (Fig. 4a). The amount of DTPA-extractable Cd in Cd50NTA30 compared to Cd50NTA0 decreased 16% in cultivated soil and 11% in uncultivated soil. The amount of DTPA-extractable Cd in the cultivated soil was a bit lower than that of the uncultivated soil due to plant root secretions and the uptake of part of the available Cd by the plant (Table 2). Soil Cd is easily converted into a soluble form after using NTA and the formation of the NTA-Cd complex, so, it was absorbed by the plant or removed from the soil during leaching.

Fig. 4.

DTPA-extractable Cd in the soil at the end of the experiment (a) and linear regressions between DTPA-extractable Cd and pH when averaged across treatments (b). Different letters show the significant difference according to Duncan’s test at 5% probability level (Means ± SD, n = 4)

In the current study, the application of NTA30 in the spiked soils caused a decrease in DTPA-extractable Cd at the end of experiments. The presence of organic-metal bonds between chelate and metal compounds causes metal to be less exposed to colloids, hydroxides, and oxides, thus preventing its precipitation and stabilization in the soil. During the leaching process, the carboxyl groups in the NTA react with the hydroxyl groups on the surface of the soil particles to form esters and increase the moving of Cd to the soil solution [4]. Studies have shown that the most important factor influencing the mobility of Cd is pH [5, 71, 72]. A decrease of 0.2 units of the pH causes a 3–fivefold increase in the unstable Cd in soil [5]. As acidity decreases, immobile forms of Cd, such as Cd in combination with Fe and Mn oxides and carbonates, are converted to exchangeable and soluble forms [73]. In the current study, soil pH was lower after the application of NTA15 and NTA30 compared to NTA0 (Fig. 3a). It can cause further solubility of Cd in the treatments containing NTA. This result is supported by the strong correlation between DTPA-extractable Cd and soil pH (R2 = 0.85, P < 0.01, Fig. 4b) and (R2 = 0.81, P < 0.05, Fig. 4b) in cultivated and uncultivated soils, respectively.

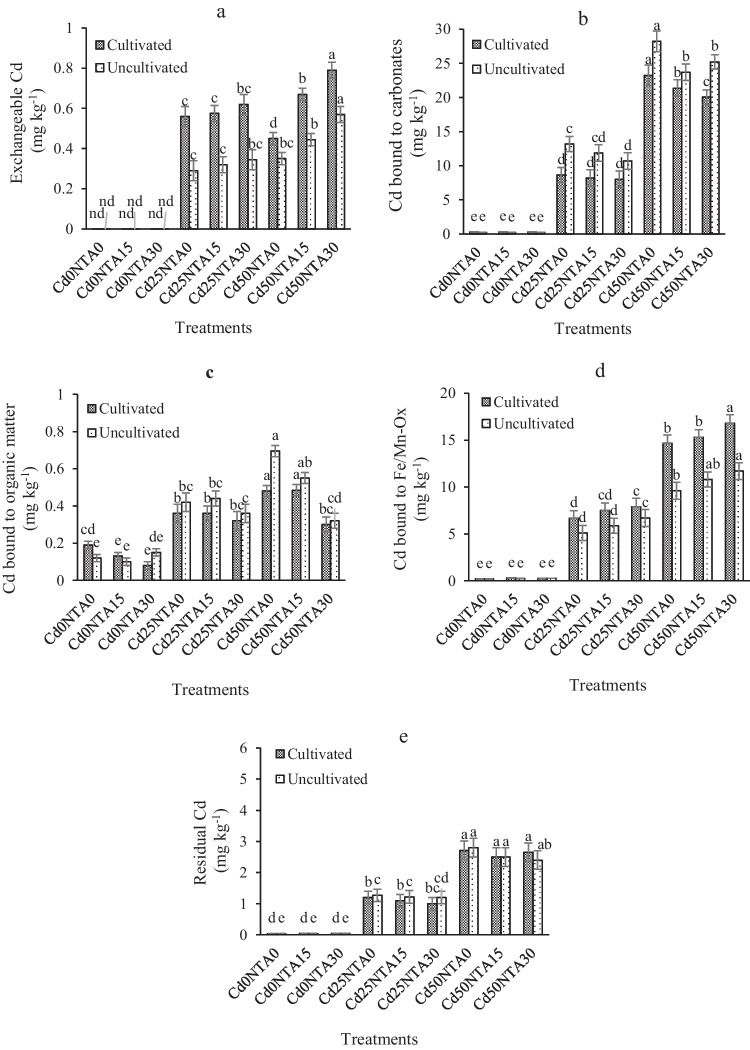

In the present study, the concentration of exchangeable Cd (F1) in Cd0NTA0, Cd0NTA15, and Cd0NTA30 treatments in both cultivated and uncultivated soils was less than the measurable limit of the atomic absorption spectrometry. The amount of F1 in cultivated soil was significantly higher than that in uncultivated soils (Table 2). The high concentrations of F1 were observed in Cd50NTA30 and Cd25NTA30, while Cd50NTA30 was 38% higher in cultivated soil compared to uncultivated soil, and Cd25NTA30 was 60% higher in cultivated soil compared to uncultivated soil (Fig. 5a). These results can be attributed to the presence of plant roots and the secretion of organic acids that create significantly decreased pH and increases F1 in the cultivated soil (Table 2). With increasing NTA application, F1 and F2 in spiked soils increased and decreased, respectively.

Fig. 5.

The concentration of Cd fractions in the cultivated and uncultivated soils. F1, exchangeable (a); F2, bound to carbonates (b); F3, bound to organic matter (c); F4, bound to iron-manganese oxides (d); F5, residual fractions (e). Different letters show the significant difference according to Duncan’s test at 5% probability level (Means ± SD, n = 4)

The amount of F2 in Cd50NTA30 decreased by 20% in cultivated soil compared to uncultivated soil, while this value in Cd25NTA30 decreased by 25% in cultivated soil compared to uncultivated soil (Fig. 5b). NTA application with acidic properties (see section “greenhouse experiments”) and specific conditions of the rhizosphere can decrease soil pH (Fig. 3a) and subsequently increase the solubility of carbonates. In calcareous soils at high pH conditions, Cd is not easily mobile, and there is more amount of F2. The sites of Cd adsorption in calcareous soils are clay and CaCO3 [74]. The fraction of CdCO3 in the calcareous soil is very sensitive to pH and can easily change to other forms of Cd in the soil by the change of soil pH [75, 76]. Other studies have also confirmed the increase in the soluble and exchangeable form of HMs after the use of various chelators (NTA, EDTA, and DTPA) [4, 77].

The concentration of F3 decreased with increasing NTA application (Fig. 5c). The amount of F3 decreased in Cd50NTA30 compared to Cd50NTA0 by 37% in cultivated soil and 53% in uncultivated soil (Fig. 5c). These values were 11 and 14% for Cd25NTA0 compared to Cd25NTA0, respectively. The reason for lower F3 in cultivated soil compared to uncultivated soil is the presence of plant and root secretions, which increases DOC, decreases the pH of the rhizosphere (Table 2), and subsequently increases the dissolution of Cd and changes F3 to F1. The organic fraction of Cd in the soil is formed through the formation of Cd bonds with organic matter through ion exchange, adsorption, and chelation reactions [9]. NTA as an external organic matter can increase Cd activity in the soil through the formation of the NTA-Cd complex and thus reduce the uptake of Cd by the sites of soil particles, thereby improving the biological access of Cd in soil. NTA is a low molecular weight organic matter and contains carboxyl functional groups that can be complex with Cd [18, 34] and cause the release of Cd and reduce Cd bounded to organic matter and carbonates.

The amount of F4 in Cd50NTA30 compared to Cd50NTA0 was increased by 17% in cultivated soil and 27% in uncultivated soil (Fig. 5d). This value in Cd25NTA30 compared to Cd25NTA0 was 18% in cultivated soil and 31% in uncultivated soil. The high amount of F4 in treatments containing NTA can be attributed to the formation of Cd bonded with Fe/Mn oxides under the influence of NTA application. The reduction of the relative percentage of F2 and F3 in the soil and the oxidative deformation (Fig. 6) can be another reason for the increase in F4. Cd is normally strongly adsorbed on the surface of Fe/Mn oxide components and bound to them [78]. Cd bounded to Fe/Mn oxides is a relatively stable bond [4, 78]. Therefore, NTA molecules are not well able to break the bonds between Cd and Fe/Mn oxides. The results also showed that the concentration of F5 in spiked soils before and after the experiments was similar (< 10%), and NTA treatments could not have a significant effect on the changes of this fraction (Fig. 5e). The reason for the ineffectiveness of the NTA in the change of residual Cd can be attributed to the fact that this form of Cd is trapped in silicate minerals. Due to its high affinity of Cd to soil oxide compounds, it is also possible that Cd bounds to Fe oxides [4, 78], and all these factors cause the same amount of F5 at the beginning and end of the experiments.

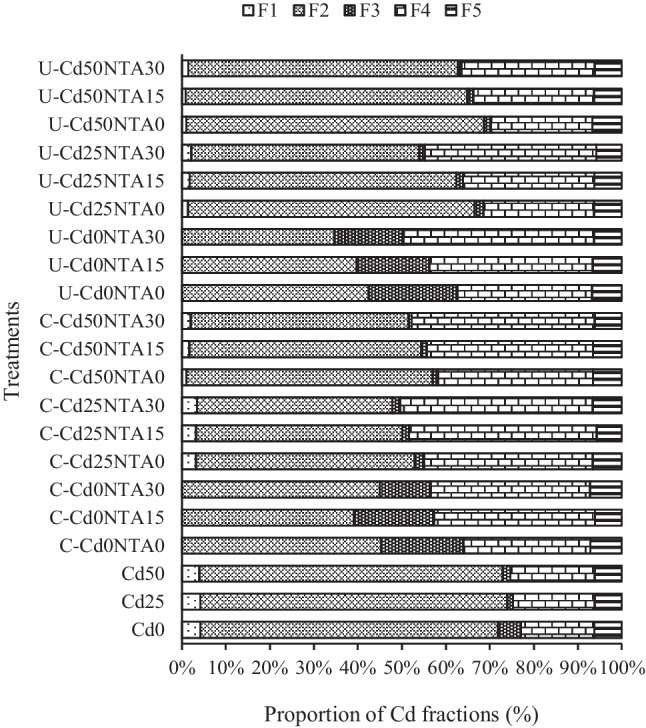

Fig. 6.

The proportion of Cd fractions in the soil before and after the experiments. Letters C and U mean cultivated soil and uncultivated soil. F1, exchangeable; F2, bound to carbonates; F3, bound to organic matter; F4, bound to iron-manganese oxides; F5, residual fractions

According to the results, the proportion of Cd fractions in the soil before and after the experiments changed (Fig. 6). The changes in the proportion of Cd fractions in cultivated soil were greater compared to uncultivated soil. At the end of the experiments, in Cd-contaminated soil, a significant decrease was observed in the proportion of F2, while the proportion of F4 increased significantly. In fact, it seems that the plants selectively remove the easily available fractions (F1 and F2) first, and this is not replenished by shifting from the other Cd fractions in the soil. So maize cultivation could already have a contamination stabilizing effect (by removing the bioavailable fractions) and Cd removing (pollution removing by overall mass of plant during phytoremediation). In uncultivated soil, most of the exchangeable and carbonate fractions of Cd (F1 and F2) were also removed during leaching and these changes intensified with the increasing NTA application.

In general, in both the cultivated and uncultivated soils, F1 (as the most available form of Cd) was negatively correlated with F2 and F3, as well as positively correlated with F4 (Table 3). Significant intensities of these correlations were higher in soil with 50 mg of Cd contamination compared to soil with 25 mg of Cd contamination. No significant correlation was observed in F5 with other fractions (Table 3).

Table 3.

Pearson correlation coefficients (r) between Cd fractions in the soil (n = 12)

| Cultivated soil | Uncultivated soil | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 | |

| Cd25 | ||||||||||

| F1 | 1 | -0.685* | -0.454 ns | 0.636 ns | 0.174 ns | 1 | -0.451 ns | -0.876** | 0.722* | 0.245 ns |

| F2 | 1 | 0.090 ns | -0.796* | 0.197 ns | 1 | 0.519 ns | -0.849** | 0.147 ns | ||

| F3 | 1 | -0.524 ns | -0.331 ns | 1 | -0.774* | -0.120 ns | ||||

| F4 | 1 | -0.115 ns | 1 | -0.139 ns | ||||||

| F5 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Cd50 | ||||||||||

| F1 | 1 | -0.803** | -0.753* | 0.871** | -0.129 ns | 1 | -0.619 ns | -0.804** | 0.862** | 0.120 ns |

| F2 | 1 | 0.558 ns | -0.763* | -0.153 ns | 1 | 0.815** | -0.870** | 0.157 ns | ||

| F3 | 1 | -0.917** | 0.322 ns | 1 | -0.833** | 0.131 ns | ||||

| F4 | 1 | -0.279 ns | 1 | 0.145 ns | ||||||

| F5 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

**, and * show correlation is significant at the probability levels of 0.05, and 0.01 respectively, and ns denotes that the value is not significant. F1, exchangeable; F2, bound to carbonates; F3, bound to organic matter; F4, bound to iron manganese oxides; F5, residual fractions

Cadmium balance

The balance of Cd in the soil, drainage water, and plant is shown in Fig. 7. According to the results of Figs. 7a, b, in cultivated soil, the amount of Cd taken up by plants, leached from the soil, and remained in the soil was 8, 14.8, and 77.2% in Cd25 and 7.6, 12, and 80.6% in Cd50, respectively. While in uncultivated soil, the amount of Cd leached from the soil and remained in the soil was 16.4 and 83.6% in Cd25 and 18.8 and 81.2% in Cd50, respectively. The results showed that in Cd50NTA30, the amount of Cd in cultivated soil with 40.3 mg kg−1 (80.6%) was not different from the amount of Cd in uncultivated soil with 40.6 mg kg−1 (81.2%), while in Cd25NTA30, the amount of Cd in cultivated and uncultivated soils was 19.3 mg kg−1 (77.2%) and 20.9 mg kg−1 (83.6%), respectively. According to these results at the end of experiments, the difference between the amount of soil Cd in cultivated and uncultivated soils was 0.3 mg kg−1 (0.6%) in Cd50NTA30, while this amount was 1.6 mg kg−1 (6.4%) in Cd25NTA30. This indicates that at very high levels of Cd in the soil (50 mg kg−1) and in the presence of higher doses of NTA (30 ml L−1) phytoremediation is not very effective in increasing the efficiency of Cd removal from the soil. These results can be attributed to the reduction of root growth and plant Cd uptake in Cd50NTA30 under the influence of high Cd toxicity and NTA application.

Conclusions

The results showed that NTA didn’t have a significant effect on MBC, soil respiration, and qCO2 (metabolic quotient) in non-spiked soil, while MBC and soil respiration decreased in Cd-spiked soil due to the increasing Cd dissolution and subsequent toxicity in the presence of NTA followed by adverse effects on microbial activity. However, the respiration rate decreased with less intensity compared to MBC, so the amount of qCO2, which is calculated through the ratio of soil respiration to MBC, was increased in the conditions of Cd toxicity in soil. Because soil microorganisms need more energy to maintain their biomass, so, the rate of respiration to MBC (as the qCO2) increased. The amount of DOC by using NTA had a significant increase especially in cultivated soil compared to uncultivated soil (due to the secretion of plant roots). NTA is a dissolved organic compound so the DOC measured to a large extent corresponds with the NTA itself. Also, due to the acidic composition of NTA and the presence of plant roots, pH was significantly reduced and the dissolution of Cd in calcareous soil was increased. Moreover, the chelating properties of NTA with Cd increased successfully the dissolution of Cd in the soil and increased the Cd uptake by plants. The highest percentage of soil Cd removal was observed in Cd25NTA30 (22.8%) in cultivated soil, while the percentage of Cd removed from soil decreased in Cd50NTA30 (19.4%) due to the high toxicity of soil Cd and reduced Cd uptake by the plant. This result is due to the change of Cd fractions in the soil under the influence of NTA and plant roots as the use of NTA, especially in cultured soil, had a significant increase in F1 by decreasing F2, and F3 (change fractions F2 and F3 to F1). NTA has a high tendency to formation of chelate with Cd bound to carbonate and organic compounds in the soil, therefore increasing the dissolution of F2 and F3. In addition, after increasing the dissolution of Cd by NTA or by organic acids in the rhizosphere, part of the soluble Cd is absorbed by the plant or removed from the soil by leaching. The Cd bound to Fe oxides due to its high affinity for soil oxide compounds (F4), while NTA had no significant effect on F5 changes because the residual form of Cd is almost permanently trapped between the clay silicate sites and is out of reach of NTA. NTA is an effective chelating agent to improve the accumulation of Cd in maize. So, the removal of Cd from the cultivated soil was higher than that from the uncultivated soil under leaching. However, more experiments are needed to investigate changes in the microbial community and enzymes, especially the rhizosphere of maize, to increase a deeper insight into the role of microbes and rhizosphere enzymes in the Cd phytoremediation with NTA in contaminated soils. Focusing on identifying maize different genes, those that are more successful in producing secondary metabolites for confronting Cd toxicity can also help grow maize in Cd-contaminated soils, as a result, the effectiveness of phytoremediation increases.

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the financial and scientific support of the Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz, Iran (Grant No. SCU.AS99.692). The authors also acknowledge the scientific support of the Ghent University of Belgium and the University of Kalyani of India.

Authors' contributions

[Narges Mehrab]: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing, Project administration; [Mostafa Chorom]: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision, Project administration; [Mojtaba Norouzi Masir]: Writing—Review & Editing; [Jayanta Kumar Biswas]: Writing—Review & Editing; [Marcella Fernandes de Souza]: Writing—Review & Editing, improvement of quality of the manuscript's English language; [Erik Meers]: Writing—Review & Editing.

Funding

This study was funded by the Research Vice Chancellor of Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz, Iran (Grant No. SCU.AS99.692).

Data availability

The data and materials will be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

The authors are fully aware of this submission and have consented to publish the manuscript in this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Chamannejadian A, Sayyad G, Moezzi A, Jahangiri A. Evaluation of estimated daily intake (EDI) of cadmium and lead for rice (Oryza sativa L.) in calcareous soils. Iran J Environ Health Sci Eng. 2013;10(1):1–5. doi: 10.1186/1735-2746-10-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang X, Duan S, Wu Q, Yu M, Shabala S. Reducing cadmium accumulation in plants: structure–function relations and tissue-specific operation of transporters in the spotlight. Plants. 2020;9(2):223. doi: 10.3390/plants9020223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xie H, Ma Y, Wang Y, Sun F, Liu R, Liu X, et al. Biological response and phytoremediation of perennial ryegrass to halogenated flame retardants and Cd in contaminated soils. J Environ Chem Eng. 2021;9(6):106526. doi: 10.1016/j.jece.2021.106526. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xie X, Yang S, Liu H, Pi K, Wang Y. The behavior of cadmium leaching from contaminated soil by nitrilotriacetic acid: Implication for Cd-contaminated soil remediation. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2020;231(4):1–12. doi: 10.1007/s11270-020-04545-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bali AS, Sidhu GPS, Kumar V. Root exudates ameliorate cadmium tolerance in plants: a review. Environ Chem Lett. 2020;18(4):1243–1275. doi: 10.1007/s10311-020-01012-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Egene CE, Van Poucke R, Ok YS, Meers E, Tack F. Impact of organic amendments (biochar, compost and peat) on Cd and Zn mobility and solubility in contaminated soil of the Campine region after three years. Sci Total Environ. 2018;626:195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaheen SM, Antoniadis V, Kwon EE, Biswas JK, Wang H, Ok YS, et al. Biosolids application affects the competitive sorption and lability of cadmium, copper, nickel, lead, and zinc in fluvial and calcareous soils. Environ Geochem Health. 2017;39(6):1365–1379. doi: 10.1007/s10653-017-9927-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tavili A, Hassanabadi F, Jafari M, Azarnivand H, Motesharezadeh B, Jahantab E. Phytoremediation ability of H. strobilaceum and S. herbacea around an industrial town. J Environ Health Sci Eng. 2021;19(2):1713–21. doi: 10.1007/s40201-021-00725-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Poucke R, Ainsworth J, Maeseele M, Ok YS, Meers E, Tack F. Chemical stabilization of Cd-contaminated soil using biochar. Appl Geochem. 2018;88:122–130. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeochem.2017.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zeng F, Ali S, Zhang H, Ouyang Y, Qiu B, Wu F, et al. The influence of pH and organic matter content in paddy soil on heavy metal availability and their uptake by rice plants. Environ Pollut. 2011;159(1):84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2010.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khodaverdiloo H, Han FX, HamzenejadTaghlidabad R, Karimi A, Moradi N, Kazery JA. Potentially toxic element contamination of arid and semi-arid soils and its phytoremediation. Arid Land Res Manag. 2020;34(4):361–391. doi: 10.1080/15324982.2020.1746707. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mehrab N, Chorom M, NorouziMasir M, de Souza MF, Meers E. Alteration in chemical form and subcellular distribution of cadmium in maize (Zea mays L.) after NTA-assisted remediation of a spiked calcareous soil. Arab J Geosci. 2021;14(21):1–14. doi: 10.1007/s12517-021-08639-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mehrab N, Chorom M, NorouziMasir M, de Souza MF, Meers E. Effect of soil application of biochar produced from Cd-enriched maize on the available Cd in a calcareous soil. Environ Earth Sci. 2022;81(18):1–13. doi: 10.1007/s12665-022-10586-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cui JL, Luo CL, Tang CWY, Chan TS, Li XD. Speciation and leaching of trace metal contaminants from e-waste contaminated soils. J Hazard Mater. 2017;329:150–158. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.12.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li T, Di Z, Islam E, Jiang H, Yang X. Rhizosphere characteristics of zinc hyperaccumulator Sedum alfredii involved in zinc accumulation. J Hazard Mater. 2011;185(2–3):818–823. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.09.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhan J, Li T, Zhang X, Yu H, Zhao L. Rhizosphere characteristics of phytostabilizer Athyrium wardii (Hook.) involved in Cd and Pb accumulation. Ecot Environ Safety. 2018;148:892–900. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2017.11.070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ayangbenro AS, Babalola OO. A new strategy for heavy metal polluted environments: a review of microbial biosorbents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(1):94. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14010094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang K, Liu Y, Song Z, Wang D, Qiu W. Chelator complexes enhanced Amaranthus hypochondriacus L. phytoremediation efficiency in Cd-contaminated soils. Chemosphere. 2019;237:124480. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.124480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Asad SA, Farooq M, Afzal A, West H. Integrated phytobial heavy metal remediation strategies for a sustainable clean environment-A review. Chemosphere. 2019;217:925–941. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hauptvogl M, Kotrla M, Prčík M, Pauková Ž, Kováčik M, Lošák T. Phytoremediation potential of fast-growing energy plants: challenges and perspectives–a review. Pol J Environ Stud. 2020;29(1):505–516. doi: 10.15244/pjoes/101621. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xiao R, Ali A, Wang P, Li R, Tian X, Zhang Z. Comparison of the feasibility of different washing solutions for combined soil washing and phytoremediation for the detoxification of cadmium (Cd) and zinc (Zn) in contaminated soil. Chemosphere. 2019;230:510–518. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.05.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cristaldi A, Conti GO, Jho EH, Zuccarello P, Grasso A, Copat C, et al. Phytoremediation of contaminated soils by heavy metals and PAHs. A brief review. Env Technol Innov. 2017;8:309–26. doi: 10.1016/j.eti.2017.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gabriele I, Race M, Papirio S, Esposito G. Phytoremediation of pyrene-contaminated soils: A critical review of the key factors affecting the fate of pyrene. J Environ Manage. 2021;293:112805. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.112805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rizwan M, Ali S, Qayyum MF, Ok YS, Zia-ur-Rehman M, Abbas Z, et al. Use of maize (Zea mays L.) for phytomanagement of Cd-contaminated soils: a critical review. Environ Geochem Health. 2017;39(2):259–77. doi: 10.1007/s10653-016-9826-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meers E, Van Slycken S, Adriaensen K, Ruttens A, Vangronsveld J, Du Laing G, et al. The use of bio-energy crops (Zea mays) for ‘phytoattenuation’of heavy metals on moderately contaminated soils: a field experiment. Chemosphere. 2010;78(1):35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen L, Yang J-Y, Wang D. Phytoremediation of uranium and cadmium contaminated soils by sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) enhanced with biodegradable chelating agents. J Clean Prod. 2020;263:121491. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121491. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meers E, Lesage E, Lamsal S, Hopgood M, Vervaeke P, Tack F, et al. Enhanced phytoextraction: I. Effect of EDTA and citric acid on heavy metal mobility in a calcareous soil. Int J Phytoremediation. 2005;7(2):129–42. doi: 10.1080/16226510590950423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pinto IS, Neto IF, Soares HM. Biodegradable chelating agents for industrial, domestic, and agricultural applications—a review. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2014;21(20):11893–11906. doi: 10.1007/s11356-014-2592-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Han R, Dai H, Zhan J, Wei S. Clean extracts from accumulator efficiently improved Solanum nigrum L. accumulating Cd and Pb in soil. J Clean Prod. 2019;239:118055. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Masoudi F, Shirvani M, Shariatmadari H, Sabzalian MR. Performance of new biodegradable chelants in enhancing phytoextraction of heavy metals from a contaminated calcareous soil. J Environ Health Sci Eng. 2020;18(2):655–664. doi: 10.1007/s40201-020-00491-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meers E, Hopgood M, Lesage E, Vervaeke P, Tack F, Verloo M. Enhanced phytoextraction: in search of EDTA alternatives. Int J Phytorem. 2004;6(2):95–109. doi: 10.1080/16226510490454777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meers E, Ruttens A, Hopgood M, Lesage E, Tack F. Potential of brassic rapa, cannabis sativa, helianthus annuus and Zea mays for phytoextraction of heavy metals from calcareous dredged sediment derived soils. Chemosphere. 2005;61(4):561–572. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2005.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang K, Liu Y, Song Z, Khan ZH, Qiu W. Effects of biodegradable chelator combination on potentially toxic metals leaching efficiency in agricultural soils. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2019;182:109399. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2019.109399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Song Y, Ammami M-T, Benamar A, Mezazigh S, Wang H. Effect of EDTA, EDDS, NTA and citric acid on electrokinetic remediation of As, Cd, Cr, Cu, Ni, Pb and Zn contaminated dredged marine sediment. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2016;23(11):10577–10586. doi: 10.1007/s11356-015-5966-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bai W. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. Harbin, China: IOP Publishing; 2018. Effects of Application of NTA and EDTA on Accumulation of Soil Heavy Metals in Chrysanthemum. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lan J, Zhang S, Lin H, Li T, Xu X, Li Y, et al. Efficiency of biodegradable EDDS, NTA and APAM on enhancing the phytoextraction of cadmium by Siegesbeckia orientalis L grown in Cd-contaminated soils. Chemosphere. 2013;91(9):1362–7. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.01.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou J, Dang Z, Chen N, Xu S, Xie Z. Influence of NTA on accumulation and chemical form of copper and zinc in maize. J Agro-Environ Sci. 2007;26(2):453–457. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Soleimani M, Hajabbasi MA, Afyuni M, Akbar S, Jensen JK, Holm PE, et al. Comparison of natural humic substances and synthetic ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid and nitrilotriacetic acid as washing agents of a heavy metal–polluted soil. J Environ Qual. 2010;39(3):855–862. doi: 10.2134/jeq2009.0292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sharma P, Rathee S, Ahmad M, Raina R, Batish DR, Singh HP. Comparison of synthetic and organic biodegradable chelants in augmenting cadmium phytoextraction in Solanum nigrum. Int J Phytoremed. 2022;20:1–10. doi: 10.1080/15226514.2022.2133081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hai NNS, Sanderson P, Qi F, Du J, Nong NN, Bolan N, et al. Effects of chelates (EDTA, EDDS, NTA) on phytoavailability of heavy metals (As, Cd, Cu, Pb, Zn) using ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum Lam.) Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2022;29(28):42102–16. doi: 10.1007/s11356-022-19877-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yanai J, Zhao F-J, McGrath SP, Kosaki T. Effect of soil characteristics on Cd uptake by the hyperaccumulator Thlaspi caerulescens. Environ Pollut. 2006;139(1):167–175. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2005.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lindsay WL, Norvell WA. Development of a DTPA soil test for zinc, iron, manganese, and copper. Soil Sci Soc Am J. 1978;42(3):421–428. doi: 10.2136/sssaj1978.03615995004200030009x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gapta P. Soil, plant, water, and fertilizer analysis. 2. New Dehli, India: Agrobios; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tessier A, Campbell PG, Bisson M. Sequential extraction procedure for the speciation of particulate trace metals. Anal Chem. 1979;51(7):844–851. doi: 10.1021/ac50043a017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mohsenzadeh F, Mohammadzadeh R. Phytoremediation ability of the new heavy metal accumulator plants. Environ Eng Geosci. 2018;24(4):441–450. doi: 10.2113/EEG-2123. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hesami R, Salimi A, Ghaderian SM. Lead, zinc, and cadmium uptake, accumulation, and phytoremediation by plants growing around Tang-e Douzan lead–zinc mine. Iran Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2018;25(9):8701–8714. doi: 10.1007/s11356-017-1156-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bayouli IT, Gómez-Gómez B, Bayouli HT, Pérez-Corona T, Meers E, Ammar E, et al. Heavy metal transport and fate in soil-plant system: study case of industrial cement vicinity. Tunis Arab J Geosci. 2020;13(2):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 48.de Santiago-Martín A, Valverde-Asenjo I, Quintana JR, Vázquez A, Lafuente AL, González-Huecas C. Carbonate, organic and clay fractions determine metal bioavailability in periurban calcareous agricultural soils in the Mediterranean area. Geoderma. 2014;221:103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.geoderma.2014.01.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wenger K, Kayser A, Gupta S, Furrer G, Schulin R. Comparison of NTA and elemental sulfur as potential soil amendments in phytoremediation. Soil Sediment Contam. 2002;11(5):655–672. doi: 10.1080/20025891107023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang L, Zhang L, Song F. Cadmium uptake and distribution by different maize genotypes in maturing stage. Commun Soil Sci Plant Anal. 2008;39(9–10):1517–1531. doi: 10.1080/00103620802006651. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rayment G, Higginson FR. Australian laboratory handbook of soil and water chemical methods. Melbourne, Australia: Inkata Press Pty Ltd; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Herbert BE, Bertsch PM. Characterization of dissolved and colloidal organic matter in soil solution: a review. In: William W, McFee J, Kelly M, editors. Carbon forms and functions in forest soils. Madison: Soil Science Society of America, American Society of Agronomy; 1995. pp. 63–88. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jenkinson DS, Ladd J. Microbial biomass in soil: measurement and turnover. In: Paul EA, Ladd JN, editors. Soil biochemistry. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1981. pp. 415–471. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Anderson JPE. Soil respiration. In: Page AL, editor. Methods of Soil Analysis Part 2 Chemical and Microbiological Properties. Madison, Wisconsin: American Society Agronomy and Soil Science Society America; 1982. pp. 831–871. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Meyer K, Joergensen RG, Meyer B. The effects of reduced tillage on microbial biomass C and P in sandy loess soils. Appl Soil Ecol. 1997;5(1):71–79. doi: 10.1016/S0929-1393(96)00123-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang M, Zhang H. Co-transport of dissolved organic matter and heavy metals in soils induced by excessive phosphorus applications. J Environ Sci. 2010;22(4):598–606. doi: 10.1016/S1001-0742(09)60151-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim K-R, Owens G, Kwon S-l. Influence of Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) on rhizosphere soil solution chemistry in long-term contaminated soils: a rhizobox study. J Environ Sci. 2010;22(1):98–105. doi: 10.1016/S1001-0742(09)60080-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang Y, Huang H, Yu H, Zhan J, Ye D, Zheng Z et al. Nitrilotriacetic acid enhanced lead accumulation in Athyrium wardii (Hook.) Makino by modifying rhizosphere characteristics. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2021. 10.21203/rs.3.rs-436736/v1 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 59.Lapie C, Leglize P, Paris C, Buisson T, Sterckeman T. Profiling of main metabolites in root exudates and mucilage collected from maize submitted to cadmium stress. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2019;26(17):17520–17534. doi: 10.1007/s11356-019-05168-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pinto A, Sim Es I, Mota A. Cadmium impact on root exudates of sorghum and maize plants: a speciation study. J Plant Nutr. 2008;31(10):1746–1755. doi: 10.1080/01904160802324829. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li H, Shen J, Zhang F, Clairotte M, Drevon JJ, Le Cadre E, et al. Dynamics of phosphorus fractions in the rhizosphere of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) and durum wheat (Triticum turgidum durum L.) grown in monocropping and intercropping systems. Plant and Soil. 2008;312(1):139–50. doi: 10.1007/s11104-007-9512-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kizilkaya R, Aşkin T. Influence of cadmium fractions on microbiological properties in Bafra plain soils. Arch Agron Soil Sci. 2002;48(3):263–272. doi: 10.1080/03650340213845. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pineros MA, Shaff JE, Manslank HS, Carvalho Alves VM, Kochian LV. Aluminum resistance in maize cannot be solely explained by root organic acid exudation. A comparative physiological study. Plant Physiol. 2005;137(1):231–241. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.047357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Meers E, Tack F, Verloo M. Degradability of ethylenediaminedisuccinic acid (EDDS) in metal contaminated soils: implications for its use soil remediation. Chemosphere. 2008;70(3):358–363. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2007.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Usman AR, Almaroai YA, Ahmad M, Vithanage M, Ok YS. Toxicity of synthetic chelators and metal availability in poultry manure amended Cd, Pb and As contaminated agricultural soil. J Hazard Mater. 2013;262:1022–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2013.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Suman A, Lal M, Singh A, Gaur A. Microbial biomass turnover in Indian subtropical soils under different sugarcane intercropping systems. Agron J. 2006;98(3):698–704. doi: 10.2134/agronj2005.0173. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Parelho C, Rodrigues A, Barreto M, Ferreira N, Garcia P. Assessing microbial activities in metal contaminated agricultural volcanic soils–an integrative approach. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2016;129:242–249. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2016.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhou H, Zhang D, Wang P, Liu X, Cheng K, Li L, et al. Changes in microbial biomass and the metabolic quotient with biochar addition to agricultural soils: A Meta-analysis. Agr Ecosyst Environ. 2017;239:80–89. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2017.01.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Xian Y, Wang M, Chen W. Quantitative assessment on soil enzyme activities of heavy metal contaminated soils with various soil properties. Chemosphere. 2015;139:604–608. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.12.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yang L, Wang G, Cheng Z, Liu Y, Shen Z, Luo C. Influence of the application of chelant EDDS on soil enzymatic activity and microbial community structure. J Hazard Mater. 2013;262:561–570. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2013.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Meers E, Unamuno V, Vandegehuchte M, Vanbroekhoven K, Geebelen W, Samson R, et al. Soil-solution speciation of Cd as affected by soil characteristics in unpolluted and polluted soils. Environ Toxicol Chem: Int J. 2005;24(3):499–509. doi: 10.1897/04-231R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yu H-Y, Liu C, Zhu J, Li F, Deng D-M, Wang Q, et al. Cadmium availability in rice paddy fields from a mining area: the effects of soil properties highlighting iron fractions and pH value. Environ Pollut. 2016;209:38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2015.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Qi F, Lamb D, Naidu R, Bolan NS, Yan Y, Ok YS, et al. Cadmium solubility and bioavailability in soils amended with acidic and neutral biochar. Sci Total Environ. 2018;610:1457–1466. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.08.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Maftoun M, Rassooli F, Ali Nejad Z, Karimian N. Cadmium sorption behavior in some highly calcareous soils of Iran. Commun Soil Sci Plant Anal. 2004;35(9–10):1271–1282. doi: 10.1081/CSS-120037545. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rajaie M, Karimian N, Maftoun M, Yasrebi J, Assad M. Chemical forms of cadmium in two calcareous soil textural classes as affected by application of cadmium-enriched compost and incubation time. Geoderma. 2006;136(3–4):533–541. doi: 10.1016/j.geoderma.2006.04.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Suzuki T, Nakase K, Tamenishi T, Niinae M. Influence of pH and Cations Contained in Rainwater on Leaching of Cd (II) from Artificially Contaminated Montmorillonite. J Environ Chem Eng. 2020;8(5):104080. doi: 10.1016/j.jece.2020.104080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jalali M, Khanlari ZV. Redistribution of fractions of zinc, cadmium, nickel, copper, and lead in contaminated calcareous soils treated with EDTA. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol. 2007;53(4):519–532. doi: 10.1007/s00244-006-0252-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fan W, Jia Y, Li X, Jiang W, Lu L. Phytoavailability and geospeciation of cadmium in contaminated soil remediated by Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Chemosphere. 2012;88(6):751–756. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2012.04.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data and materials will be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.