Dear editor,

We present a case of myelitis showing contrast on MRI, which occurred in the context of recreational use of nitrous oxide. A 20-year-old woman was admitted with gait and balance disorders that had appeared a few weeks before and progressively worsened. She had inhaled nitrous oxide (N2O) almost daily (estimated to 1200 g/day equivalent to 200 balloons) for recreational use for three years. Examination demonstrated motor and sensory impairment in all four limbs, Lhermitte's sign, and leg areflexia. Electromyogram revealed a length-dependent axonal neuropathy. A complete autoimmune work-up including antibodies against AQP4 and MOG, and lumbar puncture was negative. Spinal cord MRI showed an extensive sagittal line hyperintensity restricted to the posterior column (inverted-V sign, inset) with contrast enhancement (Fig. 1). N2O inactivates vitamin B12 by impairing its ability to act as a cofactor for methionine synthetase and may lead to neurological complications. Although aware of this interaction and self-medicating daily with vitamin B12 supplementation for months, the patient failed to prevent these neurological complications induced by the persistent intake of N2O.

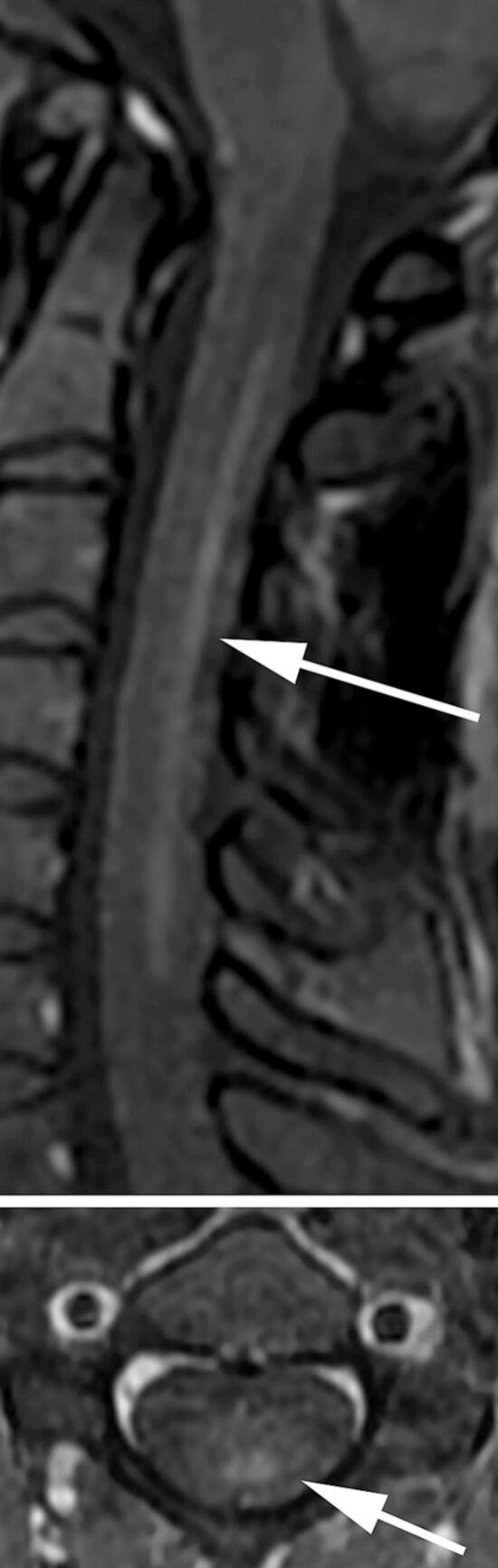

Fig. 1.

Spinal cord MRI of a 20-year-old woman with a history of massive N2O abuse who presented a sensory and motor impairment of the four limbs. T2-weighted image of the cervical cord at the axial level C2–6 shows an increased intensity of the posterior columns, predominating in the fasciculus gracilis (inverted V-sign, not shown). T1-weighted contrast-enhanced sagittal image shows a linear uptake of the lesion (upper image). The axial image supports the involvement of the fasciculus gracilis, while the fasciculus cuneatus at the posterior midline remains normal (lower inset).

Although its damaging effects were first described in 1978 by Layzer [1], the recreational use of N2O has increased dramatically in France in recent months, possibly due to the repeated periods of quarantine and curfews in the context of the Covid-19 public health crisis [2,3]. High intake of N2O could trigger central and peripheral neurological damage similar to the combined spinal cord sclerosis reported in pernicious anemia related to B12 malabsorption [3]. T2-weighted sagittal images often show cervical cord lesion restricted to the posterior columns [4]. However, contrast enhancement is exceedingly rare in pernicious anemia or after N2O abuse, so this case underlines how severe the neurological complications of N2O misuse can be [5]. Although linear contrast enhancement strongly suggests inflammatory myelitis, clinicians should be aware that similar lesions may be triggered by severe N2O abuse.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yachar Dawudi: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Data curation. Evangelia Pappa: Validation, Data curation. Karolina Hankiewicz: Validation, Data curation. Thomas De Broucker: Writing – review & editing, Validation. Mickael Bonnan: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None

References

- 1.Layzer R.B., Fishman R.A., Schafer J.A. Neuropathy following abuse of nitrous oxide. Neurology. 1978;28(5):504. doi: 10.1212/WNL.28.5.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anses . 2021. Protoxyde d’azote. Bilan des cas rapportés aux Centres antipoison en 2020 (saisine 2021-AST-0027) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vollhardt R., Mazoyer J., Bernardaud L., et al. Neurological consequences of recreational nitrous oxide abuse during SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. J. Neurol. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s00415-021-10748-7. Published online August 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pema P.J., Horak H.A., Wyatt R.H. Myelopathy caused by nitrous oxide toxicity. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 1998;19(5):894–896. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bao L., Li Q., Li Q., et al. Clinical, electrophysiological and radiological features of nitrous oxide-induced neurological disorders. NDT. 2020;16:977–984. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S236939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]