Abstract

Purpose:

To characterize cannabis use among cancer patients, we aimed to describe 1) patterns of cannabis use across multiple cancer sites; 2) perceived goals, benefits, harms of cannabis; and 3) communication about cannabis.

Methods:

Patients with 9 different cancers treated at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center between March and August 2021 completed an online or phone survey eliciting cannabis use, attitudes, and communication about cannabis. Multivariable logistic regression estimated the association of cancer type and cannabis use, adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics and prior cannabis use.

Results:

Among 1258 respondents, 31% used cannabis after diagnosis, ranging from 25% for lung cancer to 59% for testicular cancer. Characteristics associated with cannabis use included younger age, lower education level, and cancer type. In multivariable analysis, compared to lung cancer patients, gastrointestinal cancer patients were more likely to use cannabis (odds ratio [OR] 2.64, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.25–5.43). Cannabis use in the year prior to diagnosis was strongly associated with cannabis use after diagnosis (OR 19.13, 95% CI 11.92–30.72). Among users, reasons for use included difficulty sleeping (48%); stress, anxiety, or depression (46%); and pain (42%). Among respondents who used cannabis to improve symptoms, 70–90% reported improvement; <5% reported that any symptom worsened. Only 25% discussed cannabis with healthcare providers.

Conclusions:

Almost a third of cancer patients use cannabis, largely for symptom management. Oncologists may not know about their patients’ cannabis use. To improve decision making about cannabis use during cancer care, research is needed to determine benefits and harms of cannabis use.

Keywords: Cannabis, cancer, palliative care, health communication, cross-sectional studies

Introduction

Cannabis products are increasingly available for medical and non-medical use, and their use in the general population is rapidly expanding.1–5 Surveys of cancer patients report that 12–21% of people with cancer used cannabis in the prior month, though this prevalence may have changed amidst rapidly shifting policies and attitudes toward cannabis.6–8 Cancer patients may opt to use cannabis to reduce symptoms (e.g., pain, anxiety, depression, poor appetite) or extend survival, but may also feel discouraged from cannabis use, fearing side effects, interactions with treatment, or issues with legality.8–11

Complicating patients’ decision making about cannabis, few trials have evaluated the safety and efficacy of cannabis use in cancer; most evidence regarding cannabis safety and efficacy in cancer comes from observational studies.12–15 Cannabis is commonly used to treat cancer-related pain, and it may reduce nausea and anorexia.16–21 There is also limited and conflicting evidence that cannabis has antitumor properties, carcinogenic properties, or both.20,22–25 Harms of cannabis include fatigue and cognitive changes, which are already common and debilitating symptoms in cancer patients.26,27 There is a risk of addiction and exacerbation of anxiety and depression with cannabis use, which are prevalent among cancer patients.24,28 Cannabis may also have harmful interactions with therapies; recent studies showed an association between cannabis use and reduced efficacy of immunotherapy in patients with advanced cancer.29–31 A broad understanding of cancer patients’ beliefs in the benefits and harms of cannabis use is lacking.

Despite unclear evidence regarding benefits and harms, patients and providers need to make informed decisions about cannabis use. Interventions to improve communication about cannabis use in the oncology setting require a stronger understanding of cancer patients’ perceptions and experiences of cannabis use, as well as which patients are most likely to use cannabis. As part of the National Cancer Institute’s efforts to characterize cannabis use among cancer patients,32 we conducted a survey study to describe: 1) the extent and characteristics of cannabis use across a range of cancer sites; 2) perceived goals, benefits, harms of cannabis use; and 3) communication about cannabis with healthcare providers.

Methods

Patients and setting.

Using Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK) billing and administrative data, we identified adults (≥18 years old) who received treatment between March and August 2021 for any of nine cancer subtypes (brain, breast, head and neck, gynecological, gastrointestinal, lymphoma, prostate, testicular, and lung). These cancers were selected to represent populations with diverse characteristics. Among these are common and rare tumors, cancers diagnosed at various ages, cancers that affect both sexes or only one sex (assigned at birth), cancers with and without tobacco as a leading risk factor, and patients with a range of comorbidity rates, treatment types, treatment toxicity, and survival rates. We included patients who had an email address or phone number in the medical record and who resided in New York, New Jersey, or Connecticut, where medical and non-medical cannabis use is legal.

Recruitment and survey administration.

With a goal of including 1,500 patients in the final sample and accounting for an estimated 35% response rate, the sampling frame was stratified by cancer type, resulting in 486 patients randomly sampled from each cancer stratum. When there were fewer eligible patients in the cancer stratum (ie., brain and testicular cancers), all eligible patients were sampled. We contacted all sampled patients by email (or phone, if email was unavailable) to invite them to complete an online or phone survey regarding experiences with cannabis in which no identifying information (e.g., names, dates, medical record number, addresses) was collected. We followed our initial invitation with reminder emails, calls, and, for patients with cancer types with lower enrollment rates (brain, testicular, and head and neck cancer), mailed letters. We administered surveys from August 2021 to April 2022. Online surveys were anonymous, and phone surveys were confidential, with identifiers used for patient contact destroyed after study completion. Invitations and surveys were available in English and Spanish.

Survey.

The survey used harmonized measures developed by investigators from 12 NCI-designated cancer centers to elicit experiences regarding patient-reported cannabis use. (Appendix) Additional measures were developed by the MSK study team. Measures included cannabis use after diagnosis (yes/no), defined as any cannabis product, including whole plant and products containing only tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) or only cannabidiol (CBD). Patients reported their beliefs about cannabis harms and benefits; timing of cannabis use (after diagnosis, during treatment, and after treatment, as applicable); product type (whole-plant or products mostly composed of THC, products mostly composed of CBD, prescription cannabis), mode of ingestion, frequency of cannabis use; and preferred and actual sources of cannabis information. Patient factors evaluated in relation to cannabis use included self-reported sociodemographic characteristics (gender, age, race, ethnicity, income, insurance, marital status, education, and employment status), cannabis use prior to cancer diagnosis, and cancer site.

Statistical analysis.

Weighting was assigned based on characteristics (age, sex assigned at birth, race, ethnicity, cancer) of the sampled population to account for potential nonresponse bias. We descriptively report patient characteristics, beliefs and experiences with cannabis, cannabis use, and sources of cannabis information among participants who were asked and responded to each question; participants with missing responses were dropped from the denominator on a question-by question basis. The primary endpoint was use of any cannabis product after cancer diagnosis (user vs. non-user). We used bivariate analyses to compare users’ and non-users’ beliefs that 1) cannabis has any benefits for cancer patients and 2) cannabis has any harms for cancer patients. We used unadjusted and weighted multivariable logistic regression to identify sociodemographic and clinical predictors of cannabis use after diagnosis, using 2-sided tests of significance (cutoff p<0.05).

This anonymous study was deemed exempt from human subjects review by MSK Institutional Review Board.

Results

Sample.

Of 3,837 patients sampled and approached, 1,258 completed the survey (35% overall response rate; range: 25%−41% across cancers). The demographic characteristics of respondents were similar to those of the sampling frame, with a few exceptions. There were fewer female patients (52% vs. 58%) and Black patients (6% vs. 9%) among respondents compared to the sampling frame. Median age of the respondents was 63 years (interquartile range 53, 71), most were white, had at least a college education, and had an income >$100,000. (Table 1)

Table 1.

Respondent characteristics (N=1258)

| N | |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| ≤ 45 | 174 |

| 46–64 | 525 |

| ≥ 65 | 559 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 599 |

| Female | 651 |

| Non-binary | 4 |

| Missing | 4 |

| Race | |

| Asian, Asian American, Pacific Islander | 82 |

| Black | 76 |

| White | 1014 |

| Mixed or Other | 82 |

| Missing | 4 |

| Hispanic | |

| No | 1146 |

| Yes | 102 |

| Missing | 7 |

| Income | |

| <$50,000 | 178 |

| $50,000-<$100,000 | 311 |

| ≥$100,000 | 666 |

| Missing | 102 |

| Insurance | |

| Private Insurance | 657 |

| Medicare | 459 |

| Uninsured | 55 |

| Medicaid or state program | 56 |

| Other | 19 |

| Missing | 12 |

| Marital Status | |

| Married/living as married | 892 |

| Divorced/separated | 153 |

| Single | 131 |

| Widowed | 72 |

| Missing | 10 |

| Employment status | |

| Retired or Disabled | 584 |

| Employed | 522 |

| Other | 144 |

| Missing | 8 |

| Education | |

| < HS graduation | 28 |

| 12 years or completed HS | 153 |

| Post HS training / some college | 235 |

| College graduate | 420 |

| Postgraduate | 412 |

| Missing | 10 |

| Cancer (self-report) | |

| Brain | 70 |

| Breast | 188 |

| Head and neck | 142 |

| Gynecological | 146 |

| Gastrointestinal | 169 |

| Lung | 141 |

| Lymphoma | 133 |

| Prostate | 157 |

| Testicular | 32 |

| Other | 77 |

| Missing | 3 |

Cannabis use.

Details about cannabis use among all respondents are presented in Table 2. Thirty-one percent of respondents (N=385) reported using cannabis since diagnosis, ranging from 25% among lung cancer patients to 59% among testicular cancer patients. Patients most commonly used whole-plant/mostly THC products (45%) or products including a mixture of approximately equal parts THC and CBD (30%). The most common mode of ingestion was eating (55%), followed by smoking (46%); 23% used pills (including prescribed cannabis), tinctures, or sublingual tablets. Cannabis products were mostly acquired through friends, family members, or members of the community (47%). Fifty-two percent of those using cannabis after diagnosis (N=197) reported cannabis use in the past month. Eighteen percent of respondents (N=224) had used cannabis in the year prior to diagnosis, 35% of whom (N=77) used cannabis at least a few times a week.

Table 2.

Timing and patterns of cannabis use among all respondents (N=1258)

| Cannabis use any time after diagnosis | ||

|---|---|---|

| Used cannabis any time after diagnosis (N=1258) | ||

| Yes | 385 | |

| No | 865 | |

| Mode of ingestion (among users, multiple modalities could be selected, N=385) | ||

| Eating in food such as brownies, cakes cookies, or candy | 208 | |

| Smoking such as in a joint, bong, pipe, or blunt | 173 | |

| Taking by mouth such as pills, tinctures, or sublingually | 145 | |

| Vaping | 111 | |

| Applying topically such as in a lotion, cream or patch | 62 | |

| Drinking it in a liquid such as tea, cola, or alcohol | 39 | |

| Dabbing such as using waxes or shatter | 9 | |

| Other | 10 | |

| Most frequent mode of ingestion (among users, N=385) | ||

| Eating in food such as brownies, cakes cookies, or candy | 115 | |

| Smoking such as in a joint, bong, pipe, or blunt | 99 | |

| Pills/tinctures/sublingually | 87 | |

| Vaping | 45 | |

| Applying topically such as in a lotion, cream or patch | 21 | |

| Drinking it in a liquid such as tea, cola, or alcohol | 4 | |

| Other | 10 | |

| Most frequent formulation (among users, N=385) | ||

| Whole-plant cannabis (mostly THC) | 170 | |

| CBD (mostly or only CBD) | 61 | |

| Mixed (Approximately equal use of THC and CBD) | 116 | |

| Prescribed cannabis medication | 15 | |

| Don’t know | 20 | |

| How cannabis was acquired (among users, multiple sources could be selected, N=385) | ||

| Friend, family member, or member of the community | 176 | |

| Cannabis store or dispensary with a certification | 165 | |

| Unlicensed cannabis dealer or seller | 60 | |

| Cannabis store or dispensary without a certification | 49 | |

| Retail store | 26 | |

| Pharmacy with a prescription | 13 | |

| Grown personally | 12 | |

| Other | 14 | |

| Cannabis use before cancer diagnosis Used cannabis prior to diagnosis (N=1258) | ||

| Yes | 224 | |

| No | 1021 | |

| Frequency of cannabis use prior to diagnosis (among users, N=224) | ||

| More than once a day | 11 | |

| Once a day or almost every day | 29 | |

| A few times a week | 37 | |

| A few times a month | 35 | |

| Once a month or less | 63 | |

| Only tried it once or twice | 47 | |

| Used cannabis in the past month (among users, N=385) | ||

| Yes | 197 | |

| No | 184 | |

Characteristics of patients using cannabis after diagnosis.

Table 3 presents the prevalence of cannabis use by patient characteristics (n=1120). In unadjusted analyses, patients who were younger, had a diagnosis of gastrointestinal or testicular cancer, had a lower education level, and reported using cannabis in prior year were more likely than their counterparts to use cannabis after cancer diagnosis. Weighted multivariable models (N=1120) that adjusted for demographics and prior use of cannabis demonstrated that, compared to patients with lung cancer, patients with gastrointestinal cancer were more likely to use cannabis (odds ratio [OR] 2.64, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.27–5.50). Independent associations of cannabis use with testicular cancer diagnosis, younger age, and lower education were not statistically significant, though trends remained. Use of cannabis at least once in the year prior to cancer diagnosis was strongly associated with cannabis use since diagnosis (multivariable OR 19.13, 95% CI 11.92–30.72). (Table 3)

Table 3.

Distribution of cannabis use after diagnosis by patient characteristics (N=1120)

| Used cannabis | Did not use cannabis | Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | N | OR | OR | |||||

| All | ||||||||

| 356 | 764 | |||||||

| Age | ||||||||

| ≤ 45 | 79 | 87 | 2.59 | 2.16 | ||||

| 46–64 | 160 | 315 | 1.37 | 1.44 | ||||

| ≥ 65 | 117 | 362 | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 181 | 359 | 1.15 | 0.97 | ||||

| Female | 173 | 404 | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Non-binary | 2 | 1 | — | — | ||||

| Race | ||||||||

| White | 291 | 621 | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Asian/Asian American Pacific Islander | 17 | 60 | 0.70 | 0.78 | ||||

| Black | 25 | 45 | 1.24 | 1.25 | ||||

| Mixed or other | 23 | 38 | 1.36 | 0.72 | ||||

| Hispanic | ||||||||

| No | 330 | 710 | 0.99 | 0.88 | ||||

| Yes | 26 | 54 | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Income | ||||||||

| <$50,000 | 49 | 123 | 0.85 | 1.31 | ||||

| $50,000-$99,000 | 100 | 202 | 0.92 | 1.07 | ||||

| ≥$100,000 | 207 | 439 | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Insurance | ||||||||

| Private Insurance | 215 | 399 | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Medicare | 103 | 291 | 0.67 | 0.86 | ||||

| Uninsured | 17 | 32 | 0.91 | 0.82 | ||||

| Medicaid or state program | 14 | 33 | 0.83 | 0.97 | ||||

| Other | 7 | 9 | 1.35 | 1.33 | ||||

| Marital Status | ||||||||

| Married/living as married | 249 | 551 | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Divorced/separated | 48 | 92 | 1.32 | 1.03 | ||||

| Single | 49 | 67 | 1.51 | 0.69 | ||||

| Widowed | 10 | 54 | 0.48 | 0.78 | ||||

| Postgraduate | 128 | 252 | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Cancer site | ||||||||

| Brain | 24 | 42 | 2.04 | 0.96 | ||||

| Breast | 46 | 129 | 1.01 | 0.77 | ||||

| Head and neck | 41 | 90 | 1.24 | 1.15 | ||||

| Gynecological | 39 | 94 | 1.26 | 1.20 | ||||

| Gastrointestinal | 53 | 92 | 1.84 | 2.64 | ||||

| Lung | 30 | 90 | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Lymphoma | 44 | 74 | 1.71 | 1.55 | ||||

| Prostate | 42 | 94 | 1.32 | 1.36 | ||||

| Testicular | 17 | 12 | 4.34 | 2.28 | ||||

| Other | 20 | 47 | 1.22 | 1.20 | ||||

| Cannabis use prior to diagnosis | ||||||||

| Yes | 172 | 39 | 16.5 | 19.1 | ||||

| No | 184 | 725 | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

Note: Proportions shown among respondents included in the multivariable complete case analysis (N=1120). Analyses were not performed for non-binary patients due to small sample size (N=3)

Reasons for non-use and use.

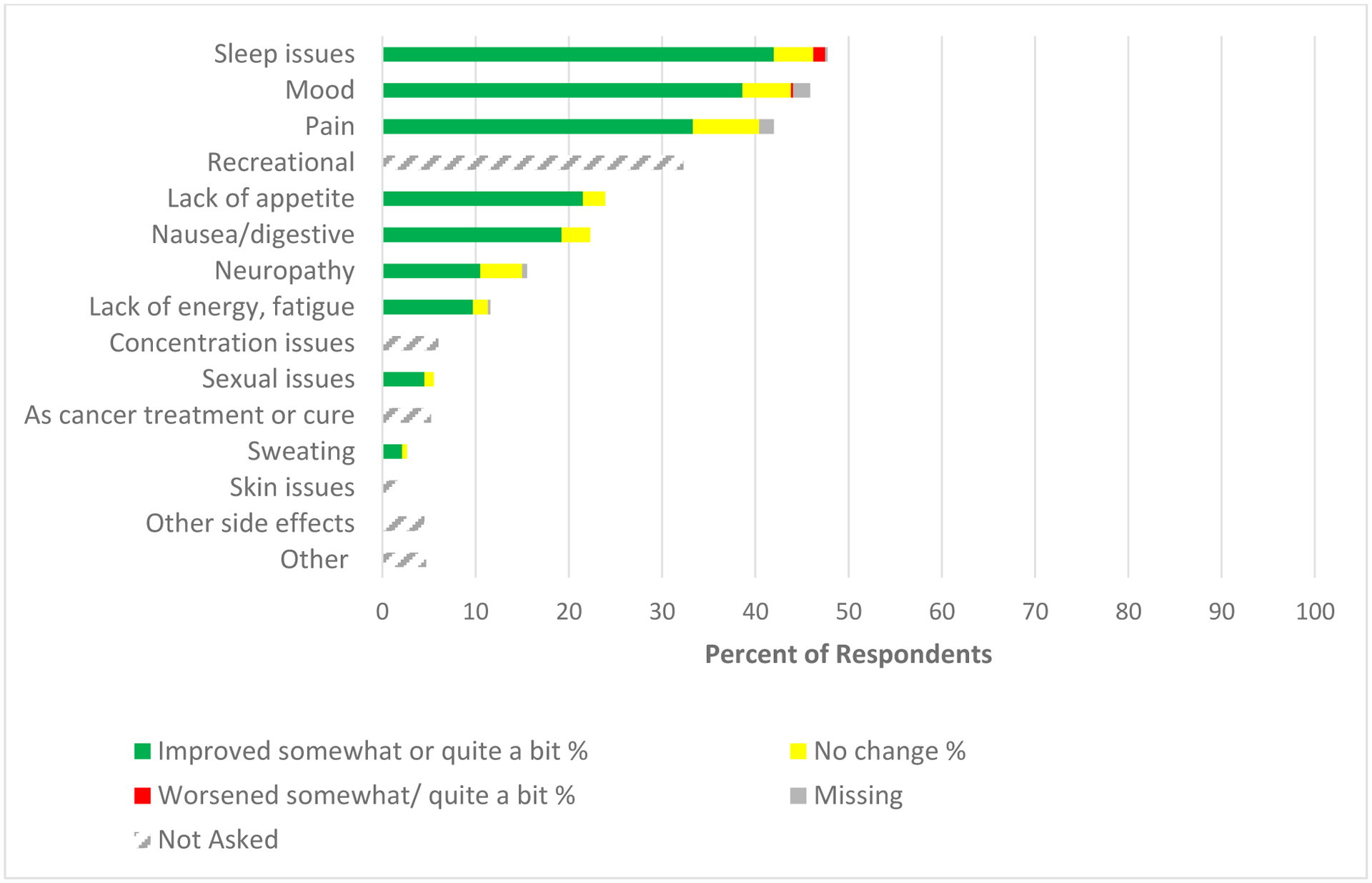

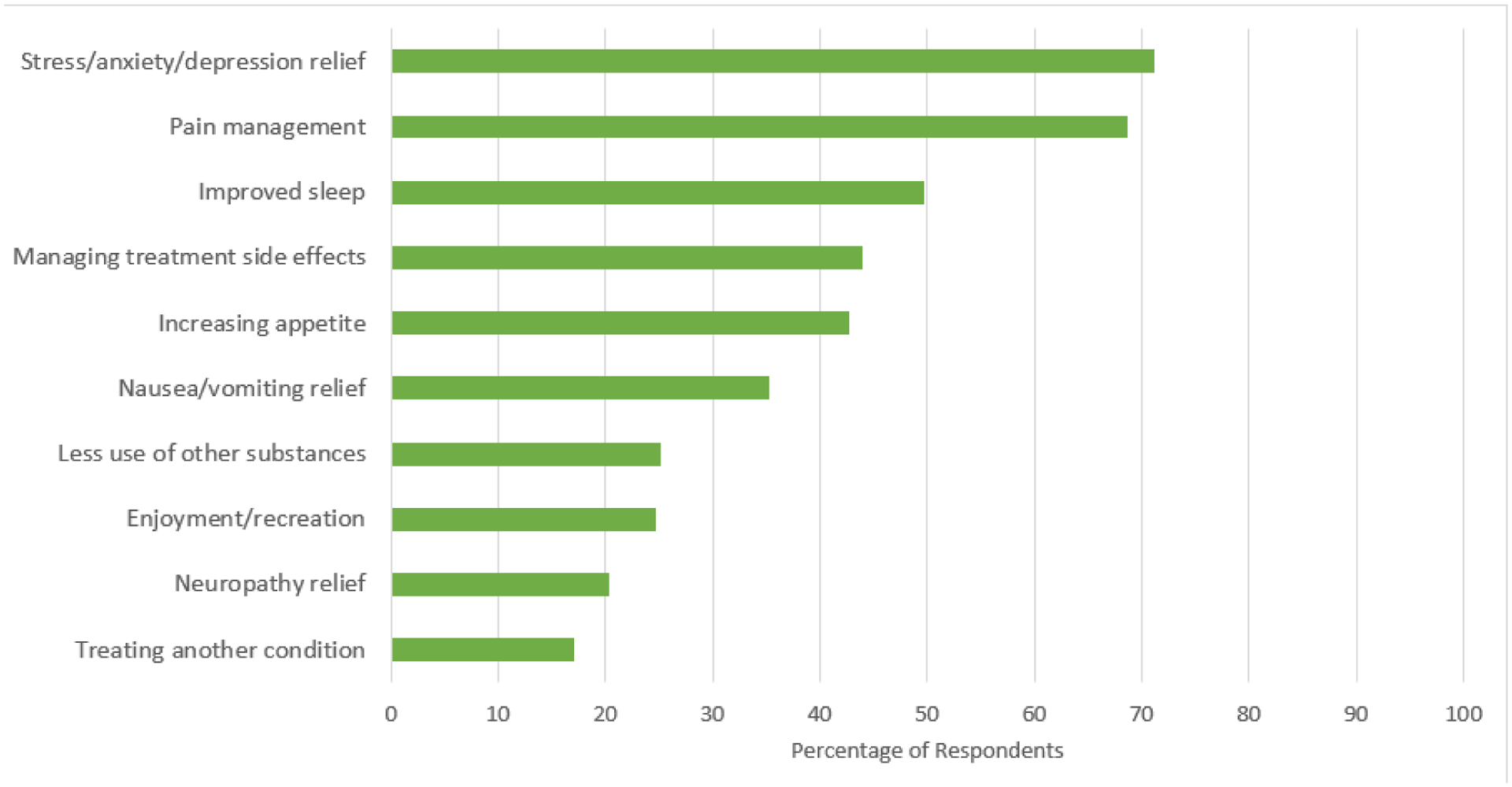

Among the 865 respondents who did not use cannabis since diagnosis, 27% (N=226) considered using cannabis. The most frequently endorsed reasons for non-use were lack of recommendation from healthcare provider (47%), too many choices or unsure which products were safe or effective (35%), and not knowing how to get it (31%). Among the 385 patients who reported cannabis use after diagnosis, the top reasons for use were difficulty sleeping (48%); anxiety, depression, or stress (46%); and pain (42%), with 32% reporting recreational use. For each symptom endorsed, 70–90% of respondents indicated that cannabis improved the symptom. No more than 3% of respondents indicated that cannabis worsened any symptom. (Figures 1 and 2)

Figure 1.

Reasons for use of cannabis (N=381)

Figure 2.

Reasons for not using cannabis among those who considered cannabis use after diagnosis (N=226)

Beliefs about cannabis.

Eighty-two percent of respondents (N=1032) believed there were benefits associated with cannabis use for cancer patients, with those who used cannabis after diagnosis more likely to perceive benefits than non-users (98% vs. 80%, respectively, χ2(1, N = 1197) = 71.6, p<0.05). The top endorsed benefits related to symptom relief, including relief of stress, anxiety, and depression (71%), pain management (69%), and improved sleep (50%). Enjoyment or recreation was endorsed by 25% of patients, and 7% believed cannabis could contribute to treatment or cure. Fifty-three percent of respondents (N=662) reported that there were potential harms associated with cannabis use, with non-users more likely to perceive harms than users (62% vs. 41%, respectively, χ2(1, N=1199) = 46.8, p<0.05). The most commonly reported harms included inability to drive (25%), difficulty concentrating (24%), and addiction (23%). Commonly endorsed perceived benefits and harms are shown in Figures 3 and 4; Supplemental Figures 1 and 2 show perceptions of each harm and benefit stratified by users and non-users.

Figure 3.

Most Common Perceived Benefits of Cannabis (N=1205)

Figure 4.

Most Common Perceived Harms of Cannabis (N=1206)

Communication and information about cannabis use.

Among the 86% of respondents who believed there were potential benefits to cannabis use (N=1032), the sources they would likely go to for information included their oncologist (78%), nurse or physician assistant (PA) involved in their care (37%), and primary care provider (33%). Internet search was endorsed by 27% of respondents. Seventy-four percent reported they would be somewhat or extremely comfortable talking to a healthcare provider about cannabis, but only 25% had done so. (Table 4) Among these 25% (N=311), 75% (N=233) spoke to an oncologist and 36% (N=113) spoke to a nurse or PA involved in their care. Advice from providers about cannabis was uncommonly received; 12% of respondents (N=153) had a provider recommend cannabis to them, while 4% (N=50) had a provider recommend against using cannabis, and 8% (N=98) had a provider say they were unable to recommend for or against cannabis use, with oncology providers (oncologists, nurses, or PAs) responsible for most of this communication. (Figure 5) Among people who reported using cannabis after diagnosis (N=385), 36% reported receiving no instructions regarding how to use cannabis and at what dose, and 24% received advice from a worker at dispensary or cannabis store; only 3% got this information from an oncologist. (Table 4)

Table 4.

Communication and information about cannabis use

| N | ||

|---|---|---|

| Missing: N=10 | ||

| Oncologist involved with your cancer treatment | 799 | |

| Nurse or physician’s assistant involved with your cancer treatment | 373 | |

| Primary care provider | 332 | |

| Internet search engine (e.g. Google) | 278 | |

| Another cancer patient | 234 | |

| Cannabis store or dispensary | 202 | |

| Friend of family member | 149 | |

| Hospital website | 128 | |

| Official federal, state, or local government website | 114 | |

| News or magazine articles | 112 | |

| Nutritionist | 93 | |

| Pamphlet or handout | 85 | |

| Social media or blogs (Facebook, Twitter, etc.) | 37 | |

| Other | 41 | |

| Missing: N=3 | ||

| Extremely comfortable | 589 | |

| Somewhat comfortable | 330 | |

| Somewhat uncomfortable | 168 | |

| Extremely uncomfortable | 153 | |

| Missing: N=3 | ||

| Yes | 311 | |

| No | 944 | |

| Missing: N=1 | ||

| No one gives me instructions | 138 | |

| Cannabis store or dispensary worker | 91 | |

| Family or family member | 82 | |

| Oncologist involved with your cancer treatment | 12 | |

| Nurse of physician assistant involved with your cancer treatment | 10 | |

| Primary care provider | 9 | |

| Pharmacist | 9 | |

| Another cancer patient | 7 | |

| Unlicensed cannabis dealer or seller | 5 | |

| Nutritionist or dietician | 4 | |

| Other | 17 | |

Figure 5.

Healthcare provider and their advice about cannabis use (N=311)

Discussion

In a large sample of recently or currently treated patients with a range of cancers and living in states where cannabis use is legal for adults, almost a third of patients reported using cannabis after their cancer diagnosis. Patients who used cannabis largely did so for symptom relief rather than with the goal of treating or curing their cancer. Those who used cannabis for symptom relief overwhelmingly reported improvement in symptoms; very few reported that cannabis made their symptoms worse. Although almost half of patients either used or considered using cannabis after diagnosis, only one fifth of patients discussed cannabis use with their oncologist.

Among the 31% of patients who used cannabis after their cancer diagnosis, half used cannabis in the past month (16% of the total sample). This is consistent with findings from earlier studies reporting rates of 12–21% of cancer patients using cannabis in the past month.6–8 We noted differences in prevalence of cannabis use by sociodemographic and clinical characteristics in unadjusted analysis, in which younger patients, those with high school education, and those with testicular or gastrointestinal cancer were more likely to use cannabis. In adjusted analyses, only the comparison of cannabis use between patients with gastrointestinal cancer and those with lung cancer remained statistically significant, although risk estimates in use by age and education remained elevated. Our findings align with a recent national survey study which found greater cannabis use among younger cancer survivors, as well as with a survey study of cancer patients in multiple western states that found greater cannabis use in younger patients and those with lower levels of education.6,33 Neither of these studies evaluated differences in cannabis use by cancer site. Ultimately, cannabis was relatively widely adopted across multiple patient groups. In our study, the strongest predictor of cannabis use after diagnosis was cannabis use in the year prior to diagnosis. This finding suggests that cannabis is not a novel product for many cancer patients, who continue to use cannabis in the context of cancer for medical or non-medical reasons. Use patterns in cancer may simply reflect trends in the general population.

Few patients reported using cannabis use with the goal of curing or treating their cancer. This contrasts with a recent study of advanced cancer patients in outpatient palliative care practices, in which 59% of patients using medical cannabis reported that cannabis was important for cancer cure.10 This difference may be driven by study population differences. Our study was not comprised of patients primarily receiving palliative care, suggesting that use of cannabis with curative intent is more limited among a wider range of cancer patients.

The vast majority (82%) of patients in our study believed that cannabis benefits people with cancer, and indeed 70–90% of patients who used cannabis to address issues with sleep, mood, pain, and other symptoms reported that cannabis use improved their symptoms. A smaller study of cancer patients using cannabis found similar self-reported benefit in sleep, pain, and anxiety symptoms, and a survey study of patients seeking cannabis through a medical cannabis clinic also found reasons for cannabis use included sleep, pain, anxiety, and appetite.34,35 A recent review of cannabis effectiveness for symptom management among patients with terminal illnesses found that although benefits have been reported, the quality of evidence is low.36 The evidence for cancer patients is of similarly poor quality but suggests improvement in nausea, pain, and other symptoms.37 Clinical practice guidelines for cancer pain state that evidence for herbal remedies, including cannabis, is insufficient to recommend these approaches.38

Harms of cannabis use include risks of fatigue, cannabis use disorder, and neurological harm.26,27,39–41 Preliminary data from cancer patients also suggests a possible reduction in the efficacy of immunotherapy.29–31 About half of respondents in our study acknowledged that cannabis could be harmful to cancer patients, with less acknowledgment of harms among users than non-users. This suggests many patients are using cannabis without a full understanding of potential side effects and associated problems, which could meaningfully impact their clinical outcomes.

Given the limited evidence of the impact of cannabis use in cancer care, it is difficult for patients and providers to make an informed decision, and the responsibility of advising on this topic may fall to oncology providers. However, oncologists are often unsure about what to recommend; 70% of oncologists do not feel comfortable advising on the clinical benefits and harms of cannabis,42 with only a quarter of oncology fellows receiving education about cannabis use and 13% reporting insufficient knowledge to make a recommendation to their patients.43 Similarly, a Canadian survey of healthcare providers found that 56% of providers felt uncomfortable with their level of knowledge regarding medical cannabis.44 We found that among patients who spoke to a provider about cannabis use, 24% had a provider report that they did not know enough to recommend for or against cannabis use. To some extent, providers’ discomfort with recommendations aligns with the lack of evidence and is unavoidable; high quality studies are critically needed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of cannabis for symptom relief, which will inform clinical practice guidelines regarding cannabis. Until that occurs, providers need to be educated about cannabis use in cancer to help patients make informed decisions in the context of uncertainty.

Patients may not get adequate information about cannabis outside of the oncology setting either. A study of cannabis dispensary workers found limited training and knowledge about therapeutic cannabis use, with workers often relying on discussions with colleagues and sampling products.45 In one study of glioma patients, more than half of cannabis users procured cannabis from friends or family.46 Many cannabis users in our study acquired cannabis through non-medical sources (e.g. friends, family, or unlicensed cannabis dealers), suggesting that oncologists should be aware that many patients use cannabis without clinician involvement. Indeed, oncologists likely do not know if their patients are using cannabis; we found that although three quarters of patients report that they are comfortable talking to providers about cannabis, only one fifth of patients talk to their oncologists.

Our study has limitations. As anticipated for a survey study among cancer patients on a potentially sensitive topic, the response rate was low (35%), raising concerns about non-response bias. Patients who used cannabis may have been less likely to participate due to concerns about confidentiality, legal risks, or stigma. However, it is also possible that patients who did not use cannabis were uninterested in a survey about cannabis. Patients who were sick from treatment might have been less likely to respond. We aimed to mitigate these concerns by ensuring anonymity, offering a brief survey (in English and Spanish) through multiple modalities with a modest financial incentive, providing extra recruitment efforts for patients with cancers that had a lower response rate, and explicitly noting in recruitment materials that we sought feedback from patients who do and do not use cannabis. We also statistically accounted for non-response using sampling weights. Ultimately, the prevalence of cannabis use among cancer patients in our study is within the range found in similar studies, which lends credibility to our findings.6–8 Self-reported cannabis use may be inaccurate as patients may underreport cannabis use because of stigma. They also may not accurately recall their cannabis use, particularly because there are multiple available products with varying constituents and modes of ingestion. Rates of cannabis use after diagnosis may vary by stage and prognosis, which we did not assess. Our findings that patients report relief across multiple symptoms must be tempered by the fact benefits and harms has not yet been determined in a randomized clinical trial.

Strengths of this study include a large population of recently (or currently) treated cancer patients living where cannabis is legal. Stratifying recruitment by cancer enabled the analyses of cannabis use in relation to cancer site. Our study found frequent cannabis use among users, a range of cannabis products consumed, a widespread perceived improvement in symptoms, a potential underestimation of cannabis harms, and limited conversations with healthcare providers about harms and benefits. Furthermore, our study found that cannabis use among cancer patients is common across sociodemographic and clinical populations, with cannabis often obtained without oncologist involvement. Oncologists and other members of the oncology team are uniquely positioned to provide education about the harms and benefits of cannabis use specifically for cancer patients, which is especially important in the context of inconclusive and often conflicting evidence. Interventions to improve cannabis education and communication need not target oncologists who treat specific cancers, as cannabis use appears consistent across multiple patient characteristics.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This work was supported by Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Support Grant from the National Institutes of Health (P30 CA008748) and a Covid administrative supplement from the National Cancer Institute (P30 CA008748-54S2).

Footnotes

Competing Interests

Dr. Korenstein’s spouse does consulting for Takeda and sits on the scientific advisory board of Vedanta Biosciences. No connection to this work. All other authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interest to disclose.

Ethics Approval

This study was reviewed and deemed exempt by our Memorial Sloan Kettering Institutional Review Board. The study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the MSK Institution.

Consent

This anonymous study was deemed exempt from human subject review by MSK’s Institutional Review Board

References

- 1.State Medical Marijuana Laws. National Conference of State Legislatures, United States. www.ncsl.org/research/health/state-medical-marijuana-laws.aspx [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marijuana Overview. National Conference of State Legislatures, United States. www.ncsl.org/research/civil-and-criminal-justice/marijuana-overview.aspx [Google Scholar]

- 3.Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP19–5068, NSDUH Series H-54). Administration. SAaMHS; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Health TNIo. Prevalence of Marijuana Use Among U.S. Adults Doubles Over Past Decade. The National Institute of Health. 2019. https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/prevalence-marijuana-use-among-us-adults-doubles-over-past-decade [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hasin DS, Saha TD, Kerridge BT, et al. Prevalence of Marijuana Use Disorders in the United States Between 2001–2002 and 2012–2013. JAMA psychiatry. Dec 2015;72(12):1235–42. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pergam SA, Woodfield MC, Lee CM, et al. Cannabis use among patients at a comprehensive cancer center in a state with legalized medicinal and recreational use. Cancer. Nov 15 2017;123(22):4488–4497. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tringale KR, Huynh-Le MP, Salans M, Marshall DC, Shi Y, Hattangadi-Gluth JA. The role of cancer in marijuana and prescription opioid use in the United States: A population-based analysis from 2005 to 2014. Cancer. Apr 22 2019;doi: 10.1002/cncr.32059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanco K, Dumlao D, Kreis R, et al. Attitudes and Beliefs About Medical Usefulness and Legalization of Marijuana among Cancer Patients in a Legalized and a Nonlegalized State. Journal of palliative medicine. Oct 2019;22(10):1213–1220. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2019.0218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luckett T, Phillips J, Lintzeris N, et al. Clinical trials of medicinal cannabis for appetite-related symptoms from advanced cancer: a survey of preferences, attitudes and beliefs among patients willing to consider participation. Internal medicine journal. Nov 2016;46(11):1269–1275. doi: 10.1111/imj.13224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zarrabi AJ, Welsh JW, Sniecinski R, et al. Perception of Benefits and Harms of Medical Cannabis among Seriously Ill Patients in an Outpatient Palliative Care Practice. Journal of palliative medicine. Apr 2020;23(4):558–562. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2019.0211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hawley P, Gobbo M. Cannabis use in cancer: a survey of the current state at BC Cancer before recreational legalization in Canada. Current oncology (Toronto, Ont). Aug 2019;26(4):e425–e432. doi: 10.3747/co.26.4743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steele G, Arneson T, Zylla D. A Comprehensive Review of Cannabis in Patients with Cancer: Availability in the USA, General Efficacy, and Safety. Curr Oncol Rep. Feb 1 2019;21(1):10. doi: 10.1007/s11912-019-0757-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson SP, Zylla DM, McGriff DM, Arneson TJ. Impact of Medical Cannabis on Patient-Reported Symptoms for Patients With Cancer Enrolled in Minnesota’s Medical Cannabis Program. Journal of oncology practice / American Society of Clinical Oncology. Apr 2019;15(4):e338–e345. doi: 10.1200/JOP.18.00562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schleider LB-L, Mechoulam R, Lederman V, et al. Prospective analysis of safety and efficacy of medical cannabis in large unselected population of patients with cancer. European journal of internal medicine. 2018;49:37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abrams DI. The therapeutic effects of Cannabis and cannabinoids: An update from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine report. Eur J Intern Med. Mar 2018;49:7–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2018.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tateo S State of the evidence: Cannabinoids and cancer pain-A systematic review. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners. Feb 2017;29(2):94–103. doi: 10.1002/2327-6924.12422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.VanDolah HJ, Bauer BA, Mauck KF. Clinicians’ Guide to Cannabidiol and Hemp Oils. Mayo Clinic proceedings. Sep 2019;94(9):1840–1851. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanders L The CBD Boom is way ahead of the Science. Science News. 2019. https://www.sciencenews.org/article/cbd-product-boom-science-research-hemp-marijuana [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meng H, Dai T, Hanlon JG, Downar J, Alibhai SMH, Clarke H. Cannabis and cannabinoids in cancer pain management. Current opinion in supportive and palliative care. Jun 2020;14(2):87–93. doi: 10.1097/spc.0000000000000493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilkie G, Sakr B, Rizack T. Medical Marijuana Use in Oncology: A Review. JAMA oncology. May 1 2016;2(5):670–675. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.0155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boland EG, Bennett MI, Allgar V, Boland JW. Cannabinoids for adult cancer-related pain: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ supportive & palliative care. Mar 2020;10(1):14–24. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2019-002032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nikan M, Nabavi SM, Manayi A. Ligands for cannabinoid receptors, promising anticancer agents. Life sciences. Feb 1 2016;146:124–30. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2015.12.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deng L, Ng L, Ozawa T, Stella N. Quantitative Analyses of Synergistic Responses between Cannabidiol and DNA-Damaging Agents on the Proliferation and Viability of Glioblastoma and Neural Progenitor Cells in Culture. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. Jan 2017;360(1):215–224. doi: 10.1124/jpet.116.236968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kramer JL. Medical marijuana for cancer. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. Mar 2015;65(2):109–22. doi: 10.3322/caac.21260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ghasemiesfe M, Barrow B, Leonard S, Keyhani S, Korenstein D. Association Between Marijuana Use and Risk of Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA network open. Nov 1 2019;2(11):e1916318. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.16318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whiting PF, Wolff RF, Deshpande S, et al. Cannabinoids for Medical Use: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Jama. Jun 23–30 2015;313(24):2456–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.6358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scarborough BM, Smith CB. Optimal pain management for patients with cancer in the modern era. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. May 2018;68(3):182–196. doi: 10.3322/caac.21453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hill KP. Medical Marijuana for Treatment of Chronic Pain and Other Medical and Psychiatric Problems: A Clinical Review. Jama. Jun 23–30 2015;313(24):2474–83. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.6199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taha T, Meiri D, Talhamy S, Wollner M, Peer A, Bar-Sela G. Cannabis Impacts Tumor Response Rate to Nivolumab in Patients with Advanced Malignancies. The oncologist. Apr 2019;24(4):549–554. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bar-Sela G, Cohen I, Campisi-Pinto S, et al. Correction: Bar-Sela et al. Cannabis Consumption Used by Cancer Patients during Immunotherapy Correlates with Poor Clinical Outcome. Cancers 2020, 12, 2447. Cancers (Basel). Apr 13 2022;14(8)doi: 10.3390/cancers14081957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bar-Sela G, Cohen I, Campisi-Pinto S, et al. Cannabis Consumption Used by Cancer Patients during Immunotherapy Correlates with Poor Clinical Outcome. Cancers (Basel). Aug 28 2020;12(9)doi: 10.3390/cancers12092447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ellison GL, Alejandro Salicrup L, Freedman AN, et al. The National Cancer Institute and Cannabis and Cannabinoids Research. Journal of the National Cancer Institute Monographs. Nov 28 2021;2021(58):35–38. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgab014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee M, Salloum RG, Jenkins W, Hales DB, Sharma A. Marijuana use among US adults with cancer: findings from the 2018–2019 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Journal of cancer survivorship : research and practice. Apr 9 2022;doi: 10.1007/s11764-021-01138-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tofthagen C, Perlman A, Advani P, et al. Medical Marijuana Use for Cancer-Related Symptoms among Floridians: A Descriptive Study. Journal of palliative medicine. Oct 2022;25(10):1563–1570. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2022.0100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raghunathan NJ, Brens J, Vemuri S, Li QS, Mao JJ, Korenstein D. In the weeds: a retrospective study of patient interest in and experience with cannabis at a cancer center. Support Care Cancer. Sep 2022;30(9):7491–7497. doi: 10.1007/s00520-022-07170-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Doppen M, Kung S, Maijers I, et al. Cannabis in Palliative Care: A Systematic Review of Current Evidence. J Pain Symptom Manage. Jun 12 2022;doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2022.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abu-Amna M, Salti T, Khoury M, Cohen I, Bar-Sela G. Medical Cannabis in Oncology: a Valuable Unappreciated Remedy or an Undesirable Risk? Curr Treat Options Oncol. Jan 13 2021;22(2):16. doi: 10.1007/s11864-020-00811-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mao JJ, Ismaila N, Bao T, et al. Integrative Medicine for Pain Management in Oncology: Society for Integrative Oncology–ASCO Guideline. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2022;0(0):JCO.22.01357. doi: 10.1200/jco.22.01357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Filbey FM, Aslan S, Calhoun VD, et al. Long-term effects of marijuana use on the brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Nov 25 2014;111(47):16913–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1415297111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meier MH, Caspi A, Ambler A, et al. Persistent cannabis users show neuropsychological decline from childhood to midlife. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Oct 2 2012;109(40):E2657–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206820109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barkus E High-potency cannabis increases the risk of psychosis. Evid Based Ment Health. May 2016;19(2):54. doi: 10.1136/eb-2015-102105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Braun IM, Wright A, Peteet J, et al. Medical Oncologists’ Beliefs, Practices, and Knowledge Regarding Marijuana Used Therapeutically: A Nationally Representative Survey Study. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. Jul 1 2018;36(19):1957–1962. doi: 10.1200/jco.2017.76.1221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Patell R, Bindal P, Dodge L, et al. Oncology Fellows’ Clinical Discussions, Perceived Knowledge, and Formal Training Regarding Medical Cannabis Use: A National Survey Study. JCO Oncol Pract. Apr 8 2022:Op2100714. doi: 10.1200/op.21.00714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hachem Y, Abdallah SJ, Rueda S, et al. Healthcare practitioner perceptions on barriers impacting cannabis prescribing practices. BMC Complement Med Ther. Sep 8 2022;22(1):237. doi: 10.1186/s12906-022-03716-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Braun IM, Nayak MM, Roberts JE, et al. Backgrounds and Trainings in Cannabis Therapeutics of Dispensary Personnel. JCO Oncol Pract. Aug 15 2022:Op2200129. doi: 10.1200/op.22.00129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reblin M, Sahebjam S, Peeri NC, Martinez YC, Thompson Z, Egan KM. Medical Cannabis Use in Glioma Patients Treated at a Comprehensive Cancer Center in Florida. Journal of palliative medicine. Oct 2019;22(10):1202–1207. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2018.0528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.