Abstract

Following a request from the European Commission, the EFSA Panel on Plant Health performed a quantitative pest risk assessment to assess whether the import of cut roses provides a pathway for the introduction of Thaumatotibia leucotreta (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) into the EU. The assessment was limited to the entry and establishment steps. A pathway model was used to assess how many T. leucotreta individuals would survive and emerge as adults from commercial or household wastes in an EU NUTS2 region climatically suitable in a specific season. This pathway model for entry consisted of three components: a cut roses distribution model, a T. leucotreta developmental model and a waste model. Four scenarios of timing from initial disposal of the cut roses until waste treatment (3, 7, 14 and 28 days) were considered. The estimated median number of adults escaping per year from imported cut roses in all the climatically suitable NUTS2 regions of the EU varied from 49,867 (90% uncertainty between 5,298 and 234,393) up to 143,689 (90% uncertainty between 21,126 and 401,458) for the 3‐ and 28‐day scenarios. Assuming that, on average, a successful mating will happen for every 435 escaping moths, the estimated median number of T. leucotreta mated females per year from imported cut roses in all the climatically suitable NUTS2 regions of the EU would vary from 115 (90% uncertainty between 12 and 538) up to 330 (90% uncertainty between 49 and 923) for the 3‐ and 28‐day scenarios. Due to the extreme polyphagia of T. leucotreta, host availability will not be a limiting factor for establishment. Climatic suitability assessment, using a physiologically based demographic modelling approach, identified the coastline extending from the northwest of the Iberian Peninsula through the Mediterranean as area suitable for establishment of T. leucotreta. This assessment indicates that cut roses provide a pathway for the introduction of T. leucotreta into the EU.

Keywords: Africa, Israel, false codling moth, climate suitability, pathway model, quantitative assessment, waste management

Summary

Following a request from the European Commission on whether the importation of cut flowers of roses (Rosa sp.) into the EU could constitute a potential pathway for the introduction of Thaumatotibia leucotreta (Meyrick) (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae), the EFSA Panel on Plant Health performed a quantitative pest risk assessment limited to the entry and the establishment of T. leucotreta, the false codling moth. The assessment focused on the pathway of import of cut roses from the areas where T. leucotreta is known to occur and the likelihood of introduction (i.e. entry, including transfer, and establishment) in the EU.

This polyphagous insect pest (affecting more than 100 genera of host plants in more than 50 botanical families) occurs in sub‐Saharan Africa and has spread to Israel. The pest is regularly intercepted on cut roses and other fresh produce imported into the EU from its areas of occurrence.

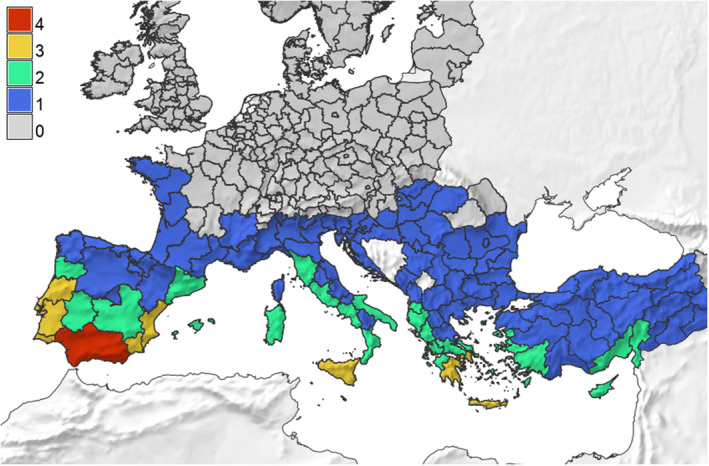

The area potentially suitable for the establishment of this pest in the EU was assessed using a climate matching approach according to Köppen–Geiger categories and a physiologically based demographic model (PBDM). The predictions of the PBDM were validated with the occurrence data from the areas of origin of the pest and from invaded areas.

T. leucotreta larvae on roses imported into the EU will be primarily affected by cold stress exacerbated by a lack of dormancy/diapause. The area of potential establishment includes the coastline extending from the northwest of the Iberian Peninsula through the Mediterranean. The estimated densities of populations in the EU do not reach the high population densities projected for East Africa. Other published models are in broad agreement with these predictions regarding the potential major areas at risk of establishment (which is related to the common use of data on temperature requirements of this pest).

Additional areas in the EU indicated as suitable with low population numbers are most likely associated with transient populations only. The main uncertainties about possible establishment in these areas are caused by the lack of developmental data at different temperatures. Besides outdoors establishment in regions climatically suitable, as stated by EPPO (2013), T. leucotreta could overwinter in greenhouses in other areas with horticultural production.

Considering entry, the pest has been frequently intercepted on cut roses and observational records exist of flying adults of the pest in a few locations in the EU. An entry pathway model was used to assess the probability of entry of T. leucotreta, considering different steps of the pathway, and to identify the uncertainties of the assessment. The model consisted of three components to determine the number of adults which would escape from cut roses imported from countries with reported occurrence of T. leucotreta (African countries and Israel):

a cut roses distribution model which describes the proportion of the imported infested roses distributed to the NUTS2 regions in the EU with suitable climate;

a developmental model that describes the proportion of T. leucotreta adults that would emerge from infested cut roses depending on the number of days after import into the EU;

a waste model which describes the proportion of T. leucotreta adults that would survive and escape prior to different types of waste treatments.

The model estimates how many T. leucotreta individuals would survive and emerge as adults from commercial or household disposal of infested cut roses, in the EU NUTS2 regions where the establishment is estimated possible based on physiologically based demographic modelling. The number of T. leucotreta adults escaping from disposed cut roses per year and per season are calculated using trade and temperature data.

Four scenarios were considered, for the timespan from the initial disposal of the cut roses at the household until the waste treatment: 3, 7, 14 and 28 days.

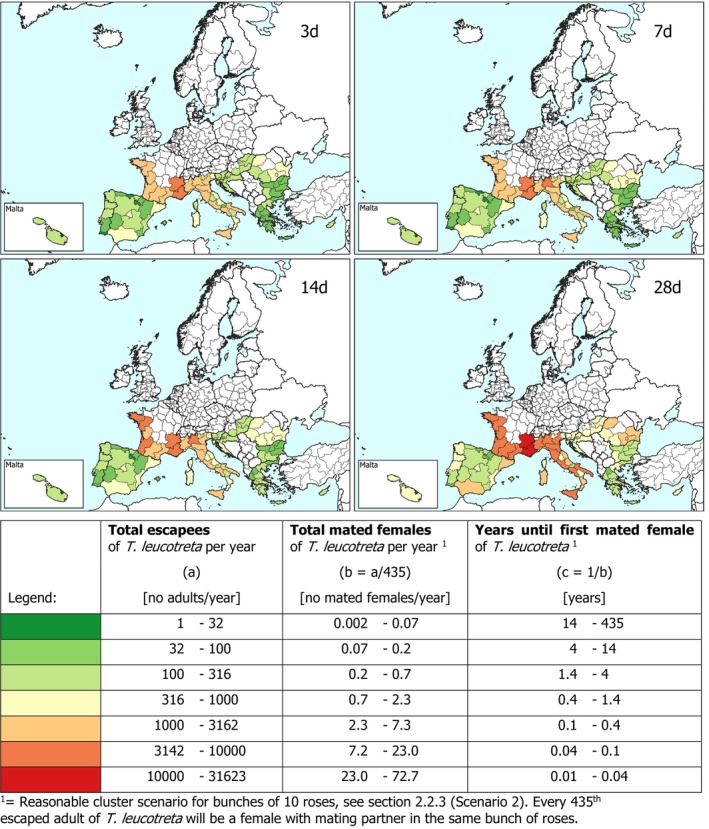

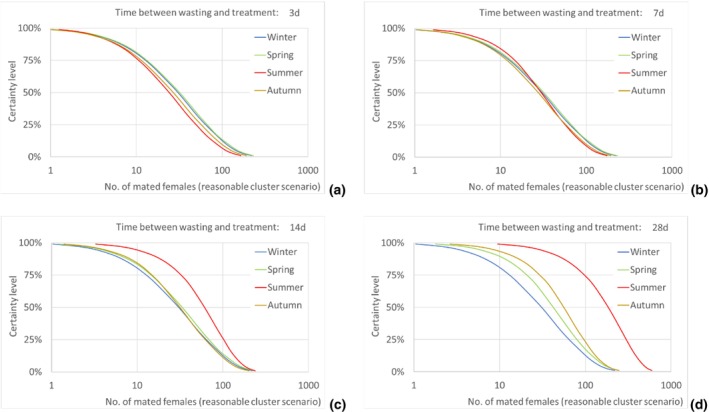

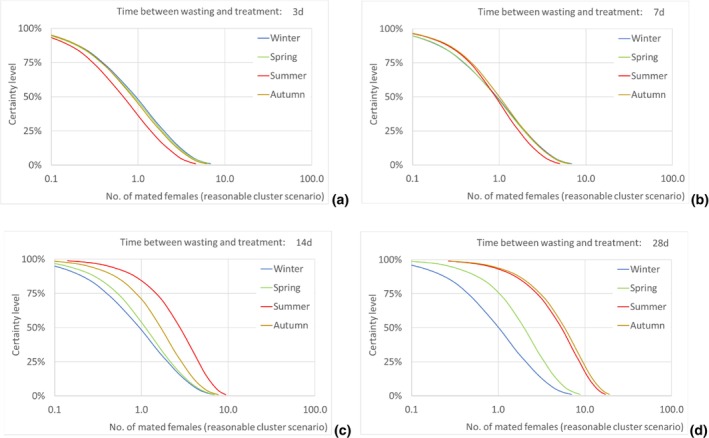

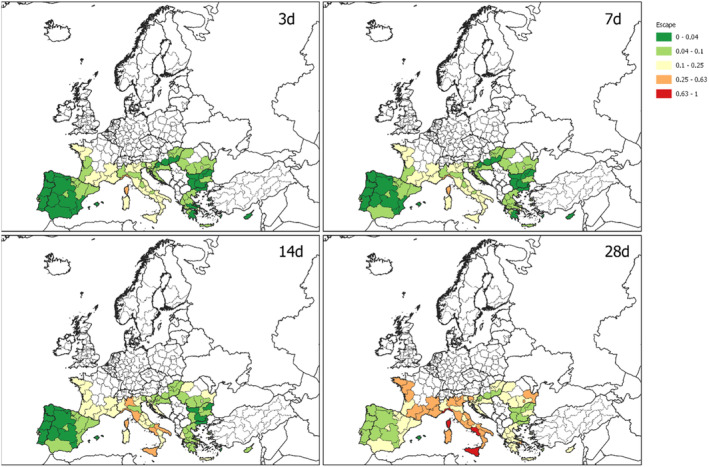

According to model results, the median number of T. leucotreta adults escaping from imported cut roses in all the climatically suitable NUTS2 regions of the EU was estimated as 49,867 per year (90% uncertainty between 5,298 and 234,393) for the 3‐day scenario of time from initial disposal of cut roses at the household until waste treatment, and as 143,689 per year (90% uncertainty between 21,126 and 401,458) for the 28‐day scenario. The differences across the scenarios are due to the escapes from the regional waste management processes, whereas the escapes from the private compost remain constant across all scenarios.

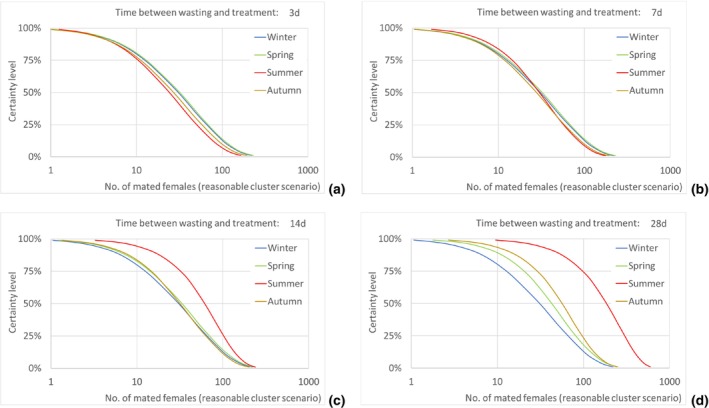

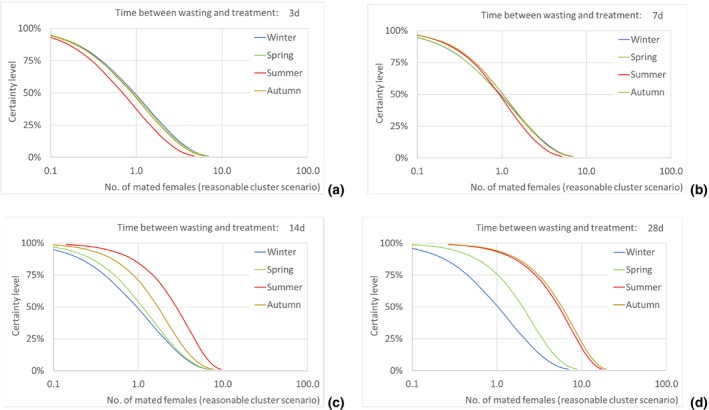

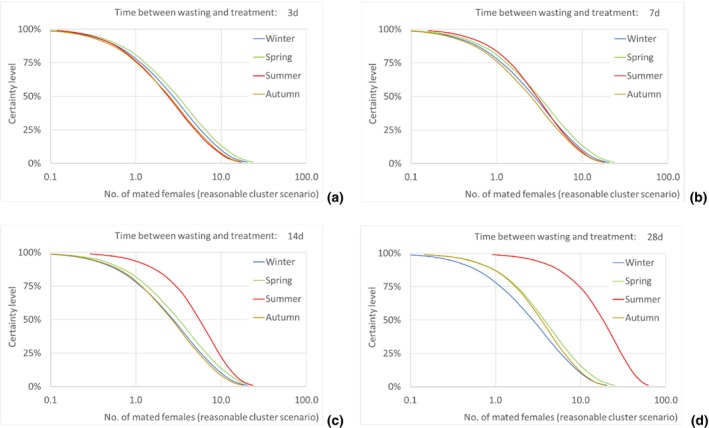

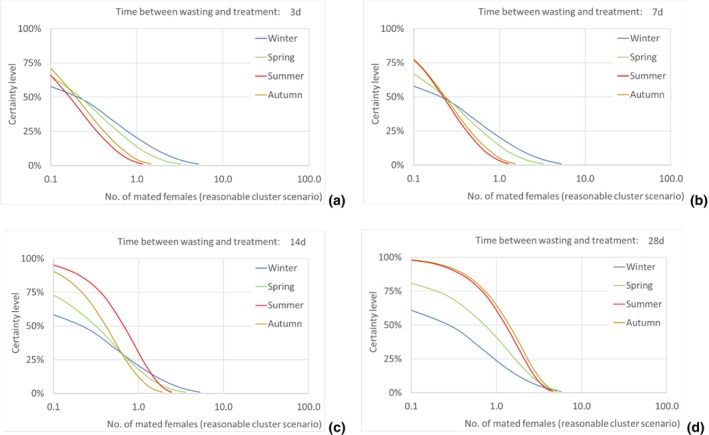

Assuming as a realistic scenario that on average one of every 435 escaping T. leucotreta moths results in a successful mating, the estimated median number of T. leucotreta mated females per year from imported cut roses in all the climatically suitable NUTS2 regions of the EU would vary from 115 (90% uncertainty between 12 and 539) up to 330 (90% uncertainty between 49 and 923) for the 3‐ and 28‐day scenarios, respectively. When analysing the results for the EU by seasons, the highest number of expected mated females is predicted in summer compared to the other seasons in the 14‐ and 28‐day scenarios. In particular, for the 28‐day scenario, the number of mated females in summer would be 185 (90% uncertainty between 28 and 480), contributing more than 50% of the total annual mated females. Factors like clustering of infestations in cut roses or spatial or temporal clustering of cut roses consumption in a particular residential area or during favourable times of the year would increase the probability of mating and transfer to suitable host.

With regard to host plants availability, the Panel agreed with EPPO (2013) on the wide availability of suitable hosts in the coastal areas of Southern Europe. A female of T. leucotreta, having an extremely wide range of plants suitable for oviposition and further larval development, will likely find suitable hosts for oviposition even during the winter in the areas climatically suitable. Due to the extreme polyphagia of T. leucotreta immature stages, host availability should not be a limiting factor for establishment in climatically suitable areas.

Overall, regular escape of pest insects on the territory of the EU is predicted but so far it has not led to outbreaks (other than few incursions) in the EU, possibly because of the relatively recent shift of pest pressure in Africa towards cut roses and the fact that much of the consumption of cut roses in the EU occurs in regions with lower climate suitability. However, observations of flying adults have been reported in the EU.

The outputs of this quantitative pest risk assessment indicate that cut roses provide a pathway for the introduction of T. leucotreta to the EU

The number of escaped adults of T. leucotreta with a possible mating partner, from the imported cut roses in the realistic clustering scenario, is predicted to be higher during summer than in the other seasons, particularly when the 14‐ and 28‐day scenarios until waste treatment are considered. This seasonality is explained by the faster development of T. leucotreta in the warmer season.

Sensitivity analysis of the pathway model showed that the main uncertainties remain regarding: the infestation rate in the imported cut roses; and main parameters of the waste model, especially the proportion of waste privately composted and the timing between initial disposal of the cut roses in the household and the waste treatment in the public facilities.

To reduce the uncertainties, data collection and research are recommended on the following key topics: the ecology and biology of T. leucotreta in its natural environment and in cut rose production in Eastern Africa; the level of infestation and clustering of T. leucotreta in the cut roses consignments; the level of effectiveness of the export and import border inspections in detecting the different life stages of T. leucotreta in cut roses; the actual waste management processes at NUTS2 level in the EU, including the proportion of private composting and the timing between the initial waste disposal and the waste treatment.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and terms of reference as provided by the requestor

1.1.1. Background

False codling moth (Thaumatotibia leucotreta [Meyrick]) is a moth species belonging to the family Tortricidae under the order of Lepidoptera. Larvae of the moth feed on a wide range of fruit, vegetable and other crops. It is not known to occur in the EU and it is regulated as a Union Quarantine Pest i.e., it is included in the annexes of Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2019/2072. It is also listed as a priority pest under Regulation (EU) 2019/1702. The pest is polyphagous and has a strong dispersal potential. The eggs and larvae of the pest are regularly intercepted on cut flowers of roses (Rosa sp.) imported into the EU from non‐EU countries.

Cut flowers of roses (Rosa sp.) are included in Annex XI.A of Regulation (EU) 2019/2072 as a commodity that is subject to phytosanitary certificates. They are, however, not included among commodities for which special import requirements for T. leucotreta are required under Annex VII. of the aforesaid Regulation.

The reason for which EFSA is requested to prepare its scientific opinion is related to the inclusion of cut roses 1 in the system of reduced frequencies of physical checks during import plant health inspection (Regulation (EC) No 1756/2004). The inclusion in the system of cut roses imported from African countries (Kenya in particular), is put in question due to the number of interceptions of the pest.

Over the last few years, the number of interceptions of eggs and larvae of T. leucotreta in imported cut flowers of roses, especially from Kenya, has increased. It would be therefore helpful, if the risk of cut roses as a potential pathway for the introduction of the pest in the Union was clarified. This would complement the non‐conclusive guidance on this potential pathway provided by the pest risk analysis carried out by EPPO in 2013 (modified in 2021), 2 and would guide the Commission and the Member States on further regulatory approach on the pest in the commodity.

1.1.2. Terms of reference (ToR)

EFSA is requested, pursuant to Article 29(1) of Regulation (EC) No 178/2002, to provide a scientific opinion in the field of plant health.

EFSA is requested to deliver an opinion whether the importation of cut flowers of roses (Rosa sp.) into the EU constitutes a potential pathway for the introduction of Thaumatotibia leucotreta (Meyrick). In order to reach that conclusion, EFSA shall take into account all relevant scientific and technical information, including data collected by Member States on interceptions of the pest in cut roses.

1.2. Interpretation of the terms of reference

The terms of reference specify that the requested opinion should address the probability of introduction, which is defined by the International Standard on Phytosanitary Measures ISPM No 5 (IPPC Secretariat, 2022) as the entry of a pest resulting in its establishment, thus including entry (including transfer) and establishment.

The assessment of spread and impact is therefore outside the scope of this mandate and not included in this opinion. The Panel therefore undertook a partial quantitative pest risk assessment, according to the principles laid down in its guidance on quantitative pest risk assessment (EFSA PLH Panel, 2018), as it is limited to the steps of entry (including transfer) and establishment.

As the mandate focuses on the assessment of the probability of introduction with cut roses under current conditions, no additional scenario of risk reduction options is included.

This opinion only deals with the introduction of T. leucotreta (the false codling moth (FCM)) via the pathway of imported cut roses from countries where the pest occurs, i.e. African countries and Israel (as specified in the mandate background).

2. Data and methodologies

For this opinion, the following data were searched:

Data on the EU import of cut roses from Africa and Israel;

Data on the import volume and destinations of cut roses into the EU;

Data on the waste treatment procedures in the EU;

Data on T. leucotreta developmental biology in relation to temperature.

The assessment was based on a combination of literature review, interviews with hearing experts and Expert Knowledge Elicitation (EKE) with experts or Panel members and EFSA staff to assess quantities that could not be well identified from literature or databases alone (EFSA, 2014). To link pest entry with establishment potential, the distribution of infested plant material entering the EU was assessed using the NUTS 2 statistical regions of the EU as the spatial resolution.

Hearings with experts from the National Plant Protection Organisations (NPPO) of Kenya and Uganda took place on 10 November 2022. Experts presented the pest status of T. leucotreta on cut roses in Kenya and Uganda and the phytosanitary measures that are in place against T. leucotreta including their limitations. The NPPOs of Kenya and Ethiopia submitted a report about T. leucotreta pest status on cut roses in their countries and the respective phytosanitary measures along with their limitations. Upon request of the EFSA, the NPPO of Kenya (KEPHIS) sent additional information, on anonymised trapping data of T. leucotreta populations in and around six rose farms (KEPHIS, personal communication, 11 January 2023).

Information on the pest distribution was retrieved from the European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization (EPPO) Global Database (EPPO, online) and relevant literature.

Data on interceptions and outbreaks of the pest within the risk assessment area were searched in the EUROPHYT and TRACES databases.

Data on cut roses import sampling and inspection procedures, infestation rates and the development stage of intercepted T. leucotreta specimens were provided by the Netherlands Food and Consumer Product Safety Authority (NVWA) (NVWA, 2022. Development of T. leucotreta on cut roses, personal communication, 23 September 2022; NVWA, 2022. Development stage of intercepted T. leucotreta specimens, personal communication, 12 October 2022; NVWA, 2022. Infestation rates of consignments of cut‐roses infested by T. leucotreta, personal communication, 12 October 2022).

Data on interception and development stage of intercepted T. leucotreta specimens in cut roses import were provided by the Belgian Federal Agency for the Safety of the Food Chain (FAVV‐AFSCA) (FAVV‐AFSCA, 2022. Reply to EFSA request of info on the FCM cut roses interceptions and checks in Belgium, personal communication, 25 January 2023).

2.1. Temporal and spatial scales

The cut roses pathway model calculates the flow per year, on average, over a period of 5 years (2022–2026).

The Köppen–Geiger climate classification used 30 years of climate data, 1981–2010. The Köppen–Geiger climate classification uses a 0.08 × 0.08° world grid.

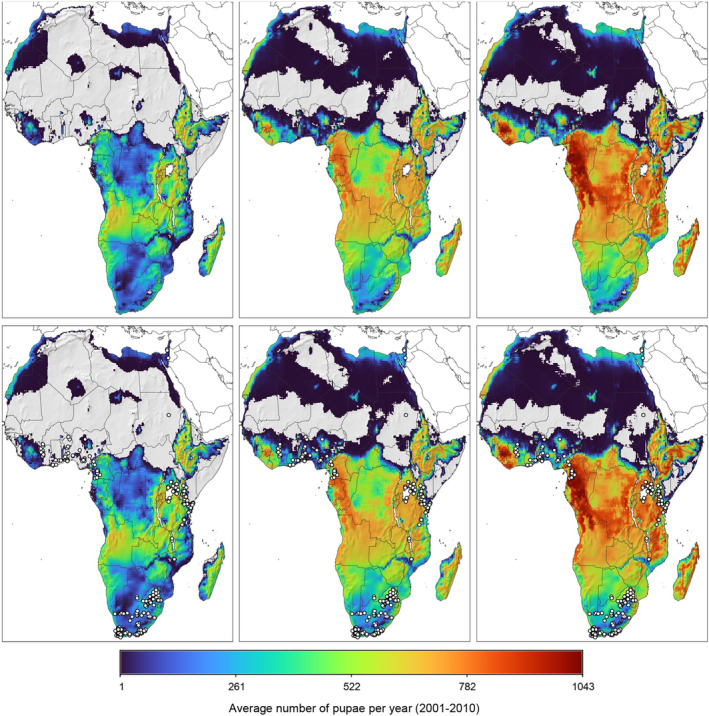

The physiologically based demographic model (PBDM) (Gutierrez, 1996) uses 2000–2010 gridded temperature data with the scale of about 0.25° × 0.25°. The projected distribution and relative abundance map of T. leucotreta used the same resolution (Ruane et al., 2015; AgMERRA data, https://data.giss.nasa.gov/impacts/agmipcf/agmerra).

2.2. Data on T. leucotreta occurrence and interceptions

2.2.1. Occurrences of T. leucotreta

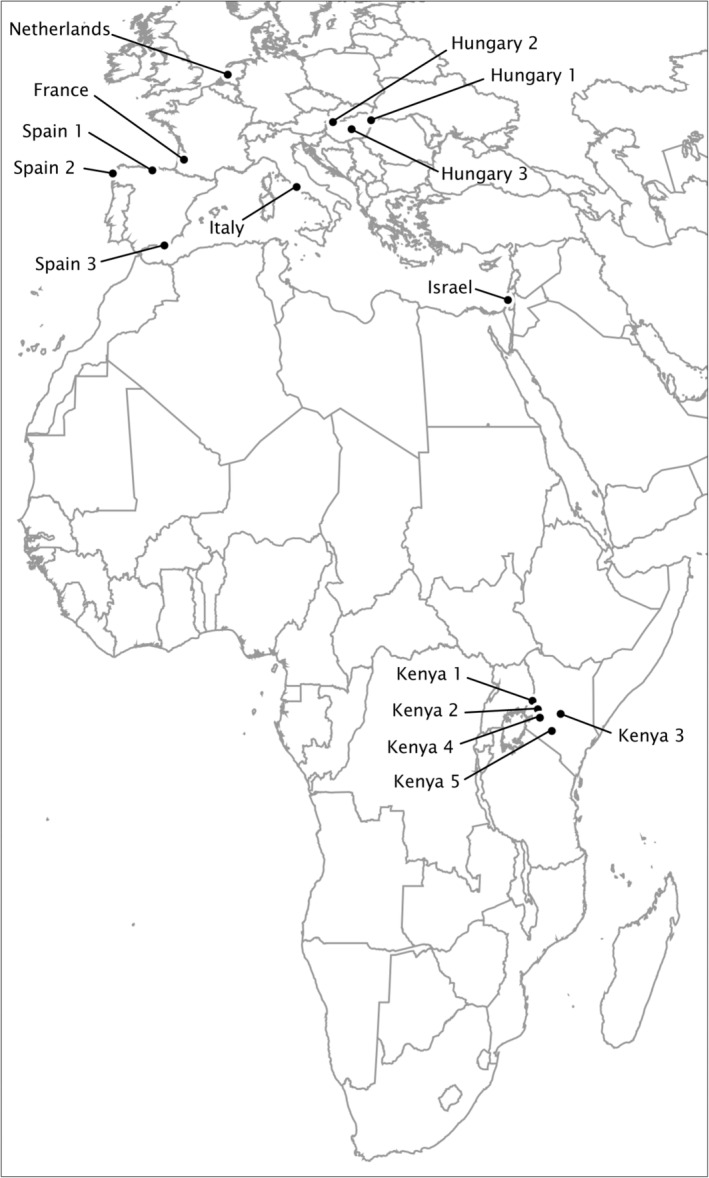

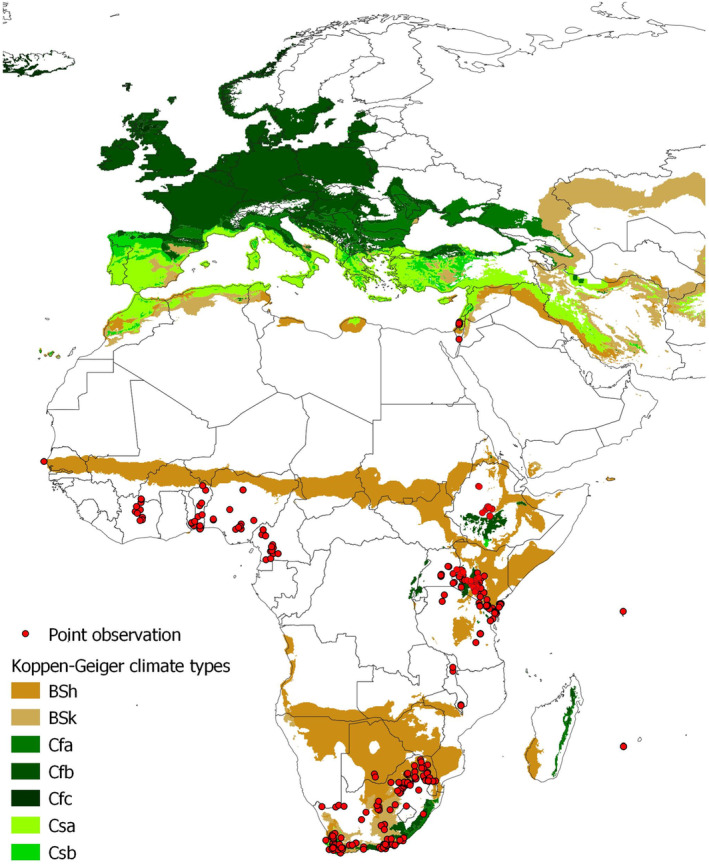

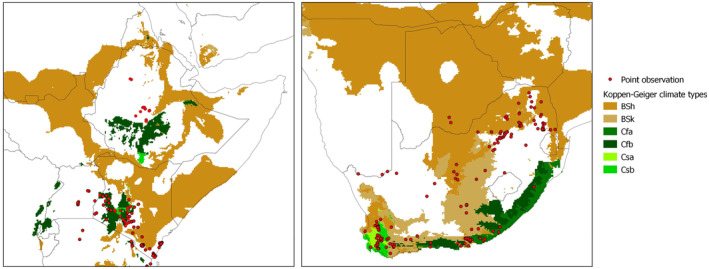

An extensive literature search for T. leucotreta global distribution was conducted in Web of Science (all databases, excluding Data Citation Index and Zoological Record) and Scopus on 12 May 2022 (Rossi et al., 2023; see Appendix D). The search string was based only on the scientific and English common name of the pest. No other keywords were used in order not to limit the retrieval of distribution data, often reported as secondary information. The review followed a two‐step approach. The first step was based on the title and the abstract, while the second one was based on the full text. The search yielded 240 documents including information on pest distribution. From these documents, 751 records of the presence of T. leucotreta were extracted, out of which 516 were specific locations reporting geographic coordinates, or very small administrative units (e.g. small provinces) for which coordinates from Google Earth were used, and 235 were related to larger administrative units (Figure 1). The full description of the literature search methodology and the results is available in Rossi et al. (2023) (see Appendix D).

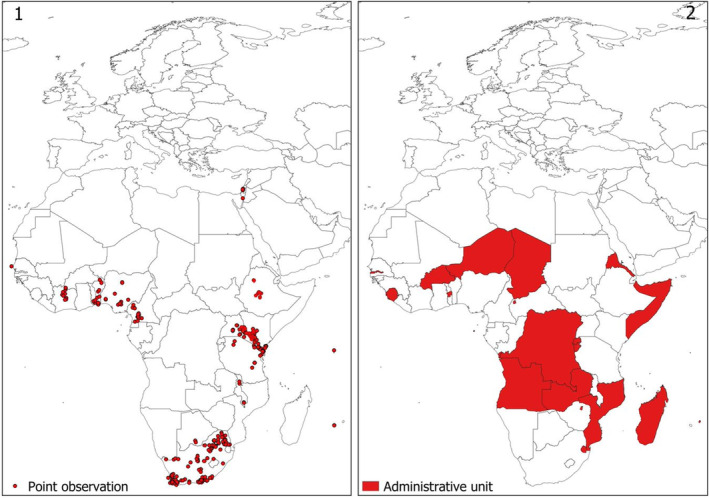

Figure 1.

Observed distribution of T. leucotreta. The map on the left (1) shows point observations. The map on the right (2) shows observations at the administrative unit level, for the areas where point observations were not found (Rossi et al., 2023; Appendix D)

2.2.2. Interceptions of T. leucotreta in border inspections

The Panel searched for interceptions of T. leucotreta on any commodity from 1994 until 2022, in EUROPHYT (last accessed on 10 February 2023) and TRACES (accessed on 10 February 2023).

From 2014 to 2022, a total of 517 interceptions of T. leucotreta were found in the EU (Table 1). Most of the infested consignments were intercepted in the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Germany and Spain. In the same period, 261 interceptions were found in cut roses, with the majority of interceptions on cut roses in the Netherlands and Belgium and few interceptions from France and Germany (Table 2). No interceptions in cut roses were reported in any other EU Member State (MS) for the period 2014–2022; however, this can be explained by their limited trade in cut roses (see Figure 4).

Table 1.

Annual interceptions of T. leucotreta on all commodities per EU MS, from 2014 until November 2022

| Total interceptions | Year | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | Total |

| Belgium | 11 | 6 | 9 | 13 | 20 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 70 | |

| Bulgaria | 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| Cyprus | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| France | 7 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 39 | |

| Germany | 3 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 14 | |||

| Ireland | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Italy | 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| Lithuania | 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| The Netherlands | 23 | 16 | 21 | 13 | 48 | 43 | 48 | 79 | 69 | 360 |

| Portugal | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | ||||||

| Spain | 6 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 12 | |||||

| Sweden | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 10 | |||

| Total | 40 | 41 | 41 | 37 | 68 | 77 | 57 | 81 | 76 | 517 |

Table 2.

Annual interceptions of T. leucotreta on cut roses per EU MS, from 2014 until November 2022

| Rosa sp. | Year | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Import country | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | Total |

| Belgium | 2 | 7 | 6 | 2 | 17 | |||||

| France | 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| Germany | 2 | 1 | 3 | |||||||

| The Netherlands | 1 | 29 | 25 | 43 | 79 | 61 | 238 | |||

| Total | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 31 | 34 | 50 | 81 | 61 | 261 |

Figure 4.

Distribution of cut roses imported by the EU (2011–2020)

From 2014 until January 2023, T. leucotreta was intercepted in 148 shipments of cut roses originating from Kenya, 84 shipments of cut roses from Uganda, 46 from Tanzania, 36 from Ethiopia, 20 from Zambia, 14 from Zimbabwe and 3 from Rwanda (Table 3). A peak in interceptions both in cut roses as well as in other consignments was recorded in 2021 (Table 4).

Table 3.

Annual interceptions of T. leucotreta on cut roses per exporting Country, from 2014 until January 2023

| Rosa sp. | Year | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exporting country | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 (January) | Total |

| Ethiopia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 23 | 1 | 36 |

| Kenya | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 37 | 39 | 9 | 44 | 18 | 1 | 148 |

| Rwanda | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Tanzania | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 33 | 12 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 46 |

| Uganda | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 9 | 19 | 13 | 19 | 19 | 3 | 84 |

| Zambia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 9 | 2 | 1 | 20 |

| Zimbabwe | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 14 |

| Total | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 96 | 76 | 26 | 82 | 63 | 6 | 351 |

Table 4.

Annual interceptions of T. leucotreta in the EU from 2014 until January 2023, in cut roses versus in all other commodities

| Year | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commodities | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | Jan‐23 | Total |

| Rosa sp. | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 96 | 76 | 26 | 82 | 63 | 6 | 351 |

| Other commodities | 169 | 260 | 146 | 141 | 112 | 116 | 34 | 56 | 14 | 3 | 1,051 |

| Total | 170 | 260 | 147 | 141 | 208 | 192 | 60 | 138 | 77 | 9 | 1,402 |

Live samples of egg and larval stages of T. leucotreta were repeatedly found during border inspections of cut roses from African countries conducted by the phytosanitary inspection services of the Netherlands (NVWA, 2022: Development stage of intercepted Thaumatotibia leucotreta specimens; personal communication, 12 October 2022; see Appendix A section A.7.1 ) and Belgium (FAVV‐AFSCA, 2022: Reply to EFSA request of info on the FCM cut roses interceptions and checks in Belgium; personal communication, 25 January 2023; data not shown). In experiments conducted by the Dutch NPPO, T. leucotreta adults were bred from some of these larvae under simulated waste‐bin conditions (NVWA 2022: Development of Thaumatotibia leucotreta on cut roses; personal communication, 23 September 2022).

2.2.3. Clustering of T. leucotreta in intercepted consignments

In the interception records of the Dutch NPPO some indications on clustered infestations of T. leucotreta in cut roses were given (NVWA, NVWA, 2022: Infestation rates of consignments of cut roses infested by T. leucotreta; personal communication, 12 October 2022). The Dutch NPPO reported, from all its imports of cut roses between January 2019 and September 2022, that 217 interceptions occurred, from which 77% of the samples had only one specimen, while 15% had two, and 8% had three specimens of T. leucotreta.

Neither the size of the consignment nor the sample size per consignment were recorded in the laboratory's database. As an approximation the Dutch NPPO assumed a median consignment size based on the import data for 2020 of 25,400 roses, which corresponds to a sample size of 400 roses according to the Dutch inspection rules (NVWA, 2022: Infestation rates of consignments of cut roses infested by T. leucotreta, personal communication, 12 October 2022, see also Appendix A Section A.7.2) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Number of T. leucotreta specimens per sample in consignments of cut roses intercepted by the Dutch NPPO in the period January 2019–September 2022 (NVWA, 2022: Infestation rates of consignments of cut roses infested by T. leucotreta; personal communication, 12 October 2022)

| Number of specimens per sample in infested consignments | Number of infested consignments | Total number of T. leucotreta specimens | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolut | Relative (% consignments) | Absolut | Relative (% specimens) | |

| 1 | 167 | 77% | 167 | 59% |

| 2 | 32 | 15% | 64 | 22% |

| 3 | 18 | 8% | 54 | 19% |

| 4 or more | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| Total | 217 | 100% | 285 | 100% |

Changing the view from consignments to specimens: 59% of the specimens were single individuals in the sample of the consignment, while 41% of the specimens were present as two or more insects per sample (= 22% + 19% + 0%; see Table 5 column on ‘Relative [% specimens]’). Using the latter value, two scenarios on the clustering of two or more specimens of T. leucotreta in the imported consignments of cut roses were constructed:

Cluster scenario 1 (worst case): Looking at the 41% of the specimens having two or more insects per sample, it is assumed that at least two specimens:

are on the same cut rose;

have similar life stages (e.g. egg, early larva), develop in parallel and escape at a similar time in the same location.

The likelihood that one insect would have a possible mating partner in the same rose is at least:

Where:

Likelihood of multiple infestation per sample (41%) is derived from Table 5 and described above;

Likelihood of having a female (2/3) and the likelihood of having a male (1/3) are derived from the sex ratio 2:1 of T. leucotreta, meaning two females per one male (Mkiga et al., 2019).

Hence, under this scenario, in total 9% of the insects will be females and will have a partner for mating in the same rose (i.e. at least one in every 11 T. leucotreta).

The worst‐case scenario is not further elaborated, because the Panel considers it as unlikely referring to:

-

–

the egg laying behaviour of the insect (according to COLEACP et al., 2020, the T. leucotreta female moth lays over 100 eggs at night, usually singly on flower petals or other parts of the rose bush);

-

–

the lack of records from border inspections on multiple T. leucotreta specimens on a single cut rose. Although, according to COLEACP et al. (2020), generally only one to three larvae survive in each rose flower, there is no record so far of multiple T. leucotreta specimens on a single cut rose upon EU import border inspection.

Cluster scenario 2 (realistic case): Looking at the 41% of the specimens having two or more insects per sample, it is assumed that:

Infested roses have no more than one T. leucotreta specimen per cut rose;

Distribution of the cut roses is done in bunches of 10 cut roses;

The specimens of T. leucotreta are uniformly distributed among the bunches of cut roses;

The specimens of T. leucotreta in a bunch of cut roses have similar life stages (e.g. egg, early larvae), develop in parallel and escape at similar time in the same location from the bunch.

The likelihood that one insect would have a possible mating partner in the same bunch of 10 roses is at least:

Where:

Likelihood of multiple infestation per sample (41%) is derived from Table 5 and described above;

Likelihood of multiple infestation per bunch (2.5%). A sample of 400 cut roses (as described above) has 40 bunches of 10 rose stems each; assuming that one bunch is infested with one insect, there is one out 40 possibilities for a second insect to infest the same bunch;

Likelihood of having a female (2/3) and the likelihood of having a male (1/3) are derived from the sex ratio 2:1 of T. leucotreta, meaning two females per one male (Mkiga et al., 2019).

Hence, under this scenario, in total 0.23% of the insect will be females and will have a partner for mating in the same bunch of 10 roses (i.e. at least one in every 435 T. leucotreta).

This realistic scenario is further elaborated in the assessment, because it is representing typical market conditions and egg laying behaviour of the insect.

Clustered scenario 3 (best case): in Appendix A, Section A.1.4, the Panel has also estimated the average number of escaped T. leucotreta adults per 1 km radius in the residential areas of the NUTS2 regions within a 10‐day period. This scenario could be interpreted as ‘best case’, when no temporal or spatial clustering of the cut roses consumption occurs, and all escaping adults are homogeneously distributed within the residential area of a NUTS2 region throughout the year.

2.2.4. Records of T. leucotreta in the EU, the UK and USA

Since 1965, more than 30 adult specimens of T. leucotreta have been reported in the EU. Occasional records have been made in Finland (Karvonen, 1983), the UK (Knill‐Jones, 1994; Langmaid, 1996; NBN atlas, 1997), Denmark and the Netherlands (Huisman and Koster, 2000), Sweden (Svensson, 2002), France (Rogard, 2015), Czechia (Šumpich et al., 2021, 2022) and Belgium and Germany (Rennwald, 2022). Recordings consisted of a single adult specimen either found in private homes, likely imported as larvae with produce from Africa (oranges; FI: Karvonen, 1983; NL: Huisman and Koster, 2000; SE: Svensson, 2002; DE: Rennwald, 2022) or captured in light traps outdoors (the UK: Langmaid, 1996; NBN atlas, 1997; FR: Rogard, 2015; BE and DE: Rennwald, 2022). However, these were all isolated findings without any evidence of established populations.

Since 2009, three incursions 3 of T. leucotreta have been reported in Europe: In the Netherlands, one larva was found in a glasshouse on habanero peppers (Capsicum chinense) in 2009 (EPPO, 2010; Potting and van der Straten, 2011), and one larva and three adults on sweet peppers (Capsicum annuum) in 2013 (EPPO, 2014); and in Germany, one male was found in 2018 on a pheromone trap in a glasshouse producing sweet peppers (C. annuum) (EPPO, 2018). These incursions have been found near packaging facilities of imported fruits (the Netherlands) and near a supermarket waste container (Germany). No populations were established.

A single adult male was detected in a trap in California (USA) in 2008 (Gilligan et al., 2011), but, in spite of extensive surveys conducted for T. leucotreta throughout the state, no further detections of the pest occurred.

2.3. Entry

The process of pest introduction is defined by the IPPC (International Plant Protection Convention) as the entry of a pest resulting in its establishment 4 (IPPC Secretariat, 2022 ). Introduction can therefore be divided into the assessment of pest entry and the assessment of pest establishment, with the process of pest transfer to a host being the step that links entry to establishment.

Estimation of the number of T. leucotreta adults escaping from the cut roses imported from African countries into the EU was performed for the NUTS2 regions identified as suitable for establishment as described in Section 2.4.

To estimate the number of T. leucotreta adults that will escape from infested cut roses imported from countries with reported occurrence of T. leucotreta, a pathway model was used that consisted of three submodels: (i) a rose distribution model (Section 2.3.1) describing how the imported and infested roses are distributed into the NUTS2 regions in the EU area suitable for establishment, (ii) a developmental model (Section 2.3.2) describing the proportion of T. leucotreta adults emerging depending on the number of days after import into the EU and (iii) a waste model (Section 2.3.3) estimating which proportion of T. leucotreta will survive and escape different waste treatments. The last component was included because the life cycle of imported cut roses was assumed to end with cut roses being disposed. For the assessment of entry as estimated by the overall entry model (Section 2.3.4), and of potential establishment of T. leucotreta, it is therefore important to estimate the proportion of T. leucotreta that survives and escapes all possible waste treatments.

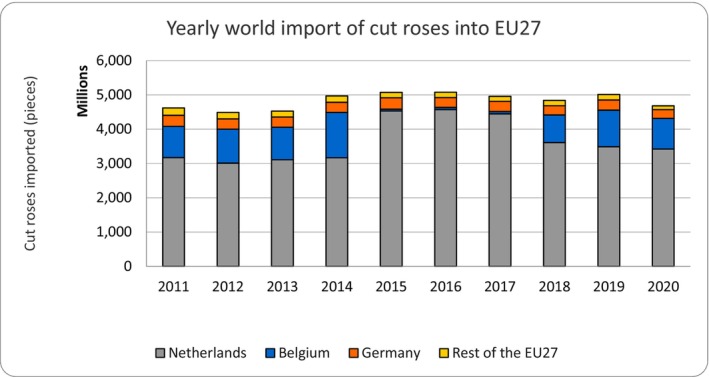

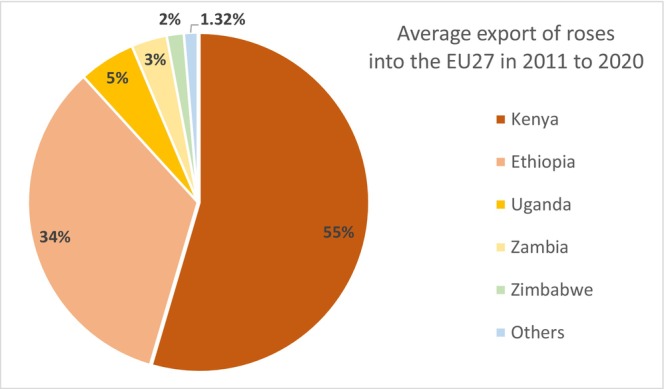

2.3.1. The cut roses distribution model

The average annual volume of cut roses imported into EU MS over the years 2011–2020 was 4,825 million stems. Most of the imported roses (91%) came from Africa and Israel (4,411 million stems). The remaining 9% (414 million stems) entered from the rest of the world, mainly Ecuador and Colombia, followed by the UK (Figure 2). The remaining countries contributed with only 1.5%. The EU countries on average exchanged 3,039 million stems among themselves. This includes trade of their own production and internal EU trade of imported cut roses from third countries.

Figure 2.

Trade in cut roses in the EU (average of 2011–2020)

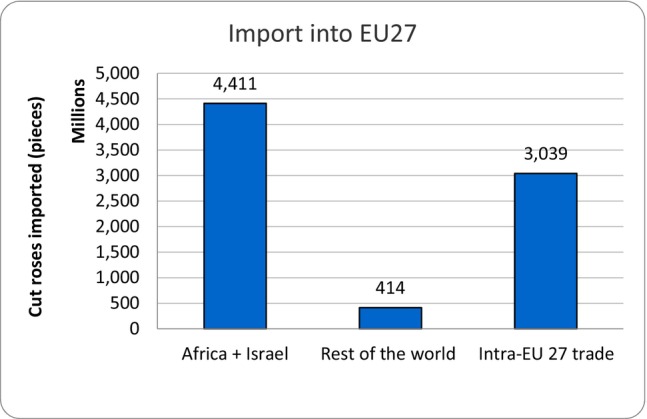

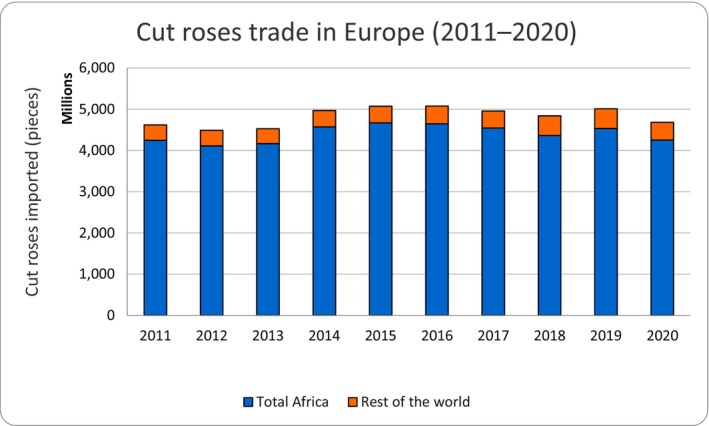

The volume of cut roses imported into the EU has been relatively stable in period 2011–2020 (Figure 3), reaching a peak in 2016. The Covid‐19 pandemic had only a marginal effect on the trade as indicated by the slight reduction in 2020.

Figure 3.

Trends in the EU of import of cut roses (2011–2020)

The imported roses are not distributed evenly through the EU. Most of the cut roses (on average 75.5%) enter the Netherlands, 15.0% enter Belgium, 6.1% enter Germany and only 3.4% enter the remaining 24 EU countries (Figure 4). However, the intra‐EU trade complicates the calculations of the pathway model for the EU 27 MS, e.g. between 2015 and 2017 the import into Belgium was reduced, while that of the Netherlands was increased by a similar amount, indicating intra‐EU trade relations between neighbouring countries. Due to the observed intra‐EU trade relations, to limit the pathway model to the main intra‐EU trade relations, some EU countries were therefore clustered for manageability of the pathway model calculations: ‘The Netherlands/Belgium’, ‘Germany/Luxembourg’, ‘Spain/Portugal’, ‘Italy/Malta’ and ‘Greece/Cyprus’.

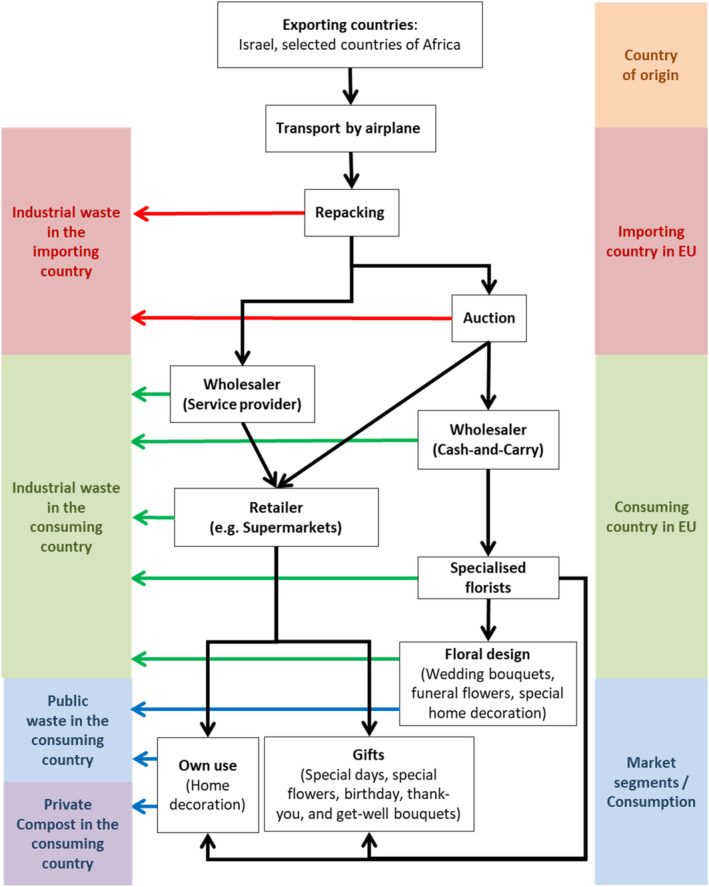

The pathway of cut roses in the EU starts with entries mainly via airplane followed by repacking, auction, wholesalers and retail sales to the consumers (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Pathway of cut roses from import to waste (adapted from CBI, 2017)

All cut roses will finally end in the waste, differentiated by commercial waste in different countries, public waste and private compost.

According to CBI (2017), the European cut flower market consists of two market channels: one focusing on specialised florists and the other on unspecialised retail (e.g. supermarkets). The main differences between the channels are the role of the flower auction and wholesalers, and the characteristics of the products.

Some of the imported cut roses are sold directly to high‐end customers, but most are reserved for Dutch auctions, a major hub in the redistribution of cut flowers in the EU and worldwide. In 2020, in total 2,912 million stems were imported from African countries (CBS, 2022), 2,814 million stems were traded through Dutch auctions (Royal Flora Auctions, 2021). A minor part of cut roses consumed in the EU is produced in European greenhouses (the Netherlands 20.0%, Germany 0.4% and Belgium 0.2%). A large part (78.0%) of the cut rose stems auctioned in the Netherlands are imported from rose farms in Africa (Ethiopia 44.0%, Kenya 31.0%, Uganda 1.5% and others from Rwanda, Tanzania, Zimbabwe, Zambia and South Africa) (see Appendix A). Germany and France are the major intra‐EU trade markets for auctioned roses (Rabobank, 2022). From the auction houses, cut roses are redistributed to various points of sale at retailers, any delay affects their vase life. Direct sales can drastically reduce the farm‐to‐vase time.

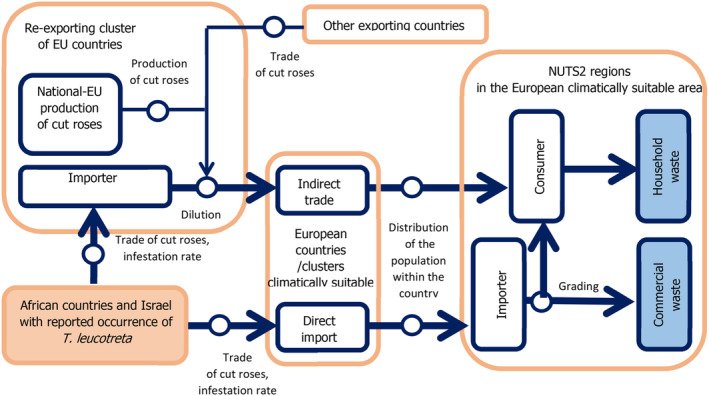

Due to missing precise information on the proportion of trade via specialised florists and supermarkets, the pathway model only distinguishes direct import into the consuming country/NUTS2 region, and re‐exporting via European countries (indirect trade, see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Pathway of cut roses from import to waste as conceptualised for the rose distribution model

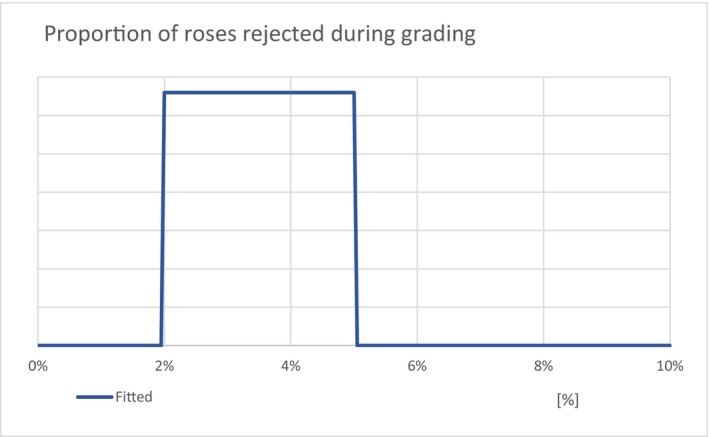

The waste resulting from rejected roses by grading/repacking will end in the commercial waste of the consuming country or stays in the importing country. A diagram presenting the pathway model for the rose distribution model is outlined in Figure 6.

The rose distribution model comprises two main pathways: ‘direct’ and ‘indirect’ import into the EU area climatically suitable. The latter one is further divided into two main clusters for intra‐EU trade: ‘The Netherlands/Belgium’ and ‘Germany/Luxembourg’.

-

Direct import of cut roses from African countries and Israel, with reported occurrence of T. leucotreta by a country with areas climatically suitable.

For this pathway, the trade volume reported by Eurostat on national and monthly basis was considered in the model. To cover most of the trade between the countries within the areas climatically suitable, the following country clusters were established: (i) Spain and Portugal, (ii) Italy and Malta and (iii) Greece and Cyprus. In the model, it is assumed that the distribution within a cluster will follow the distribution of potential consumers, thus the distribution of the population within the countries/clusters. Different regional consumption habits are not considered.

In this pathway, importers, including when applicable wholesalers and distribution centres, are in the NUTS2 region of consumption and it is assumed that they perform the necessary grading and repacking.

-

The cut roses are imported by the Netherlands and Belgium and further traded ‘intra‐EU’ to the EU countries with areas climatically suitable.

Because only the total trade volume between the Netherlands/Belgium and other EU flower consuming countries is reported to Eurostat, it is assumed that the imported cut roses (from Africa and Israel) will be equally diluted by other imports of cut roses, and the production in the Netherlands and Belgium. Preferences for the intra‐EU re‐trade of African cut roses are not considered.

In this pathway, grading and repacking is assumed to be done in the Netherlands and Belgium, and then, the cut roses will go directly to retailers or specialised florist shops in the consuming countries.

It is assumed that the national EU distribution will follow again the distribution of potential consumers, thus the distribution of the population within the cluster. Different regional consumption habits are not considered.

-

The cut roses are imported by Germany and Luxembourg and further traded intra‐EU the countries with areas climatically suitable.

For this pathway, the same assumptions made for re‐exporting for the Netherlands and Belgium are valid (see Section 2 for details).

No other European cluster for the re‐export of African roses is considered due to minor trade volumes. Due to the low infestation, the model further assumes that an infested rose contains one insect, and this could be in any life stage.

In all scenarios, the annual trade is further stratified by seasons: December–February, March–May, June–August, September–November; to reflect the different climatic condition per season (see developmental model).

The overall number of T. leucotreta individuals per season ending in commercial or household waste in a NUTS2 region climatically suitable in a specific season was therefore calculated as below. A description of the parameters used in the rose distribution model is presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Description and source of evidence for the parameters used in the rose distribution model

| Parameter | Description | Source | Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| FCMcommercial, NUTS2, Season FCMhousehold, NUTS2, Season | Number of T. leucotreta individuals ending in commercial or household waste in a NUTS2 region climatically suitable during a specific season | Calculated | |

| AF | African countries and Israel with reported occurrence of T. leucotreta | EPPO Global Database (Appendix A, Section A.2) | Strata |

| EURA | European countries/clusters with areas climatically suitable/under risk | Countries with at least one NUTS2 region with a climate suitability classification by the physiologically based demographic model above 0 (Appendix A, Section A.3) | Strata |

| NUTS2 | NUTS2 regions climatically suitable | NUTS2 regions with at least one grid cell with a climate suitability classification by the physiologically based demographic model above 0 (Appendix A, Section A.3) | Strata |

| NLBE | Cluster of re‐exporting countries: the Netherlands/Belgium | Annual trade of cut flowers from 2011 to 2020 (Appendix A, Section A.5) | Strata |

| DELU | Cluster of re‐exporting countries: Germany/Luxembourg | Annual trade of cut flowers from 2011 to 2020 (Appendix A, Section A.6) | Strata |

| Season | Stratification by season: winter, spring, summer, autumn; or total | Strata | |

| TradeAF‐EURA, Season | Direct trade of cut roses from AF to European climatically suitable countries/clusters (Unit: [pcs]) | Eurostat monthly trade of cut roses (CN 03061100) in 2011–2020 (Appendix A, Section A.4) | NORMAL |

| PopulationNUTS2/EURA | Proportion of the human population in the NUTS2 region climatically suitable in relation to the whole country or cluster (Unit: [−]) | Eurostat population 1 January 2020 (Appendix A, Section A.4.2) | CONSTANT |

| Grading | Proportion of direct imported cut roses, which on average is discarded due to quality issues (Unit: [−]) | Default value (Appendix A, Section A.4.4) | UNIFORM |

| TradeAF➔NLBE, Season TradeAF➔DELU, Season | Trade of cut roses from AF to the European re‐exporting clusters in a specific season (Unit: [pcs]) | Eurostat monthly trade of cut roses (CN 03061100) in 2011–2020 (Appendix A, Sections A.5, A.6) | NORMAL |

| TradeOthers➔NLBE, Season TradeOthers➔DELU, Season | Trade of cut roses from other countries to the European re‐exporting clusters in a specific season (Unit: [pcs]) | Eurostat monthly trade of cut roses (CN 03061100) in 2011–2020 (Appendix A, Sections A.5, A.6) | NORMAL |

| ProductionNLBE, Season ProductionDELU, Season | Average production of cut roses in European re‐exporting clusters in a specific season (Unit: [pcs]) | Calculated | |

| AreaNL AreaDE | Average, annual area for the production of cut roses in specific MS (Unit: [ha]) | National statistics on cut roses production surface | CONSTANT |

| ExtrapolationNL➔NLBE ExtrapolationDE➔DELU | Extrapolation from national production area to the area in a re‐exporting cluster (Unit: [−]) | Eurostat farm structure | CONSTANT |

| Conversionha➔pcs | Productivity of cut roses (Unit: [pcs/ha]) | Productivity of different roses | CONSTANT |

| ProportionSeason/Total | Proportion of cut roses produced in the re‐exporting clusters in a specific season compared to the annual production | Default value: equally distributed | CONSTANT |

| DilutionNLBE,Season DilutionDELU,Season | Dilution of T. leucotreta‐infested cut roses, imported from Africa and Israel, by other imports and own production in a specific re‐exporting cluster and season (Unit: [−]) | Calculated for scenarios without/with Intra‐EU trade | UNIFORM |

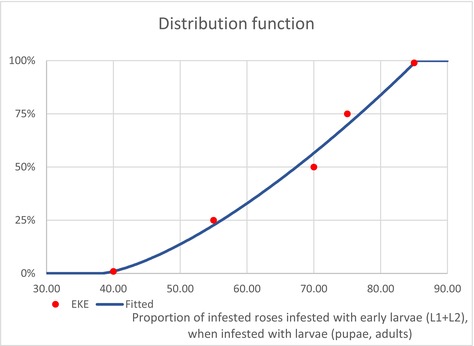

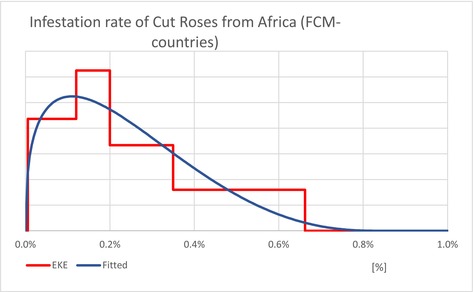

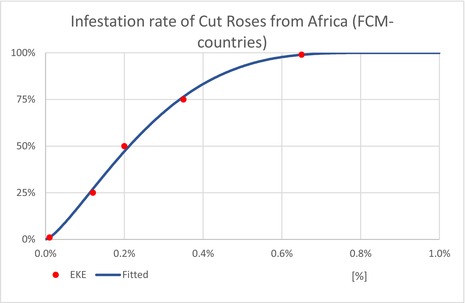

| InfestationAF | Average infestation rate of cut roses from AF (Unit: [−]) | EKE question 2 (Appendix A, Section A.7) | GENERALBETA |

It is assumed that commercial waste only appears in the grading step at import or auction. Thus, for indirect import (intra‐trade) via EU countries outside the EU climatically suitable areas (the EU climatically suitable area is indicated in the equations as the EU risk area, abbreviated as EURA), no commercial waste has to be considered. For the direct import, the number of T. leucotreta (FCM) entering a NUTS2 region in the EU climatically suitable area in a specific season (FCMcommercial, NUTS2 Season) is calculated as:

where TradeAF‐EURA, Season, InfestationAF, PopulationNUTS2/EURA and Grading are the volume of direct import from Africa into a country cluster in a specific season, the infestation rate of African roses, the proportion of the population within a NUTS2 region climatically suitable (compared to the total population of the country cluster) and the proportion of roses deselected by grading due to quality problems or similar, respectively.

Because all roses will finally be wasted, the household waste consists in the EU climatically suitable areas of the marketed (not deselected during grading) roses, and the imported roses from the ‘Dutch/Belgian’ and ‘German/Luxembourg’ cluster.

Roses re‐traded intra‐EU are diluted by national production and by other imports into these clusters (‘Dutch/Belgian’ and ‘German/Luxembourg’ clusters). The dilution factor is calculated as proportion of African and Israelian roses in relation to the total amount of roses within the corresponding country cluster. The total amount of roses in a country cluster consists of import from Africa, other imports and own production. This assumes that all roses within an intra‐EU trade cluster are mixed before intra‐EU re‐trade.

Missing information on the cut rose production of Belgium and Luxembourg was extrapolated from the Dutch and German production and converted from the production area.

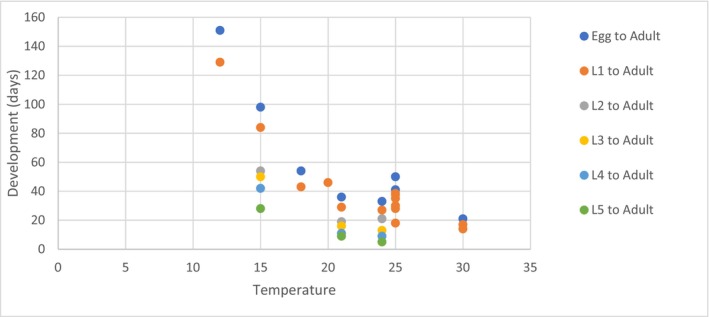

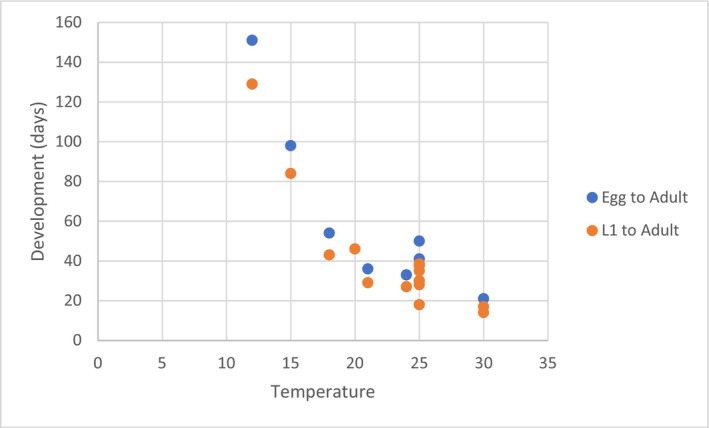

2.3.2. The developmental model

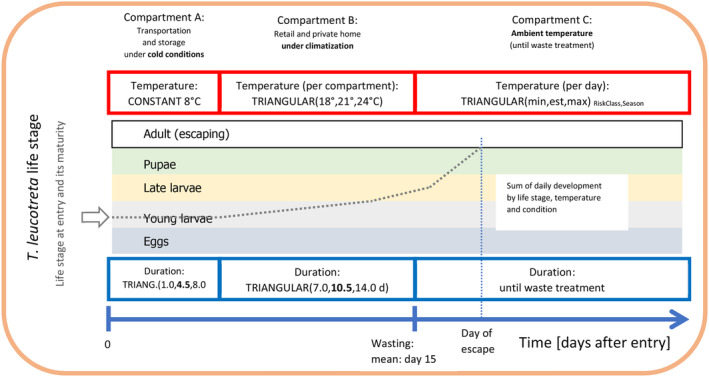

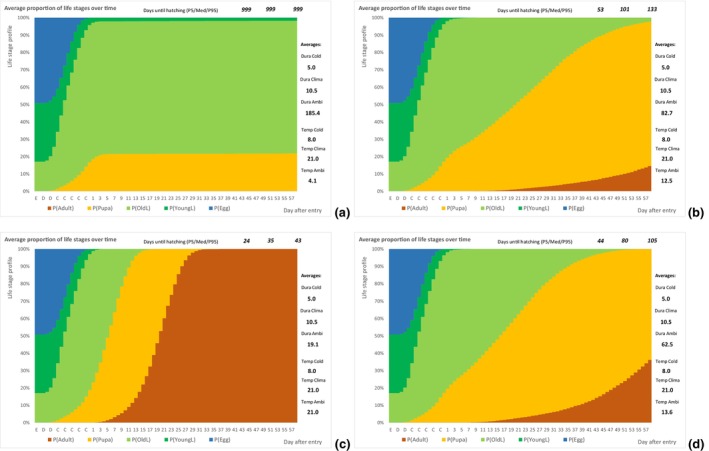

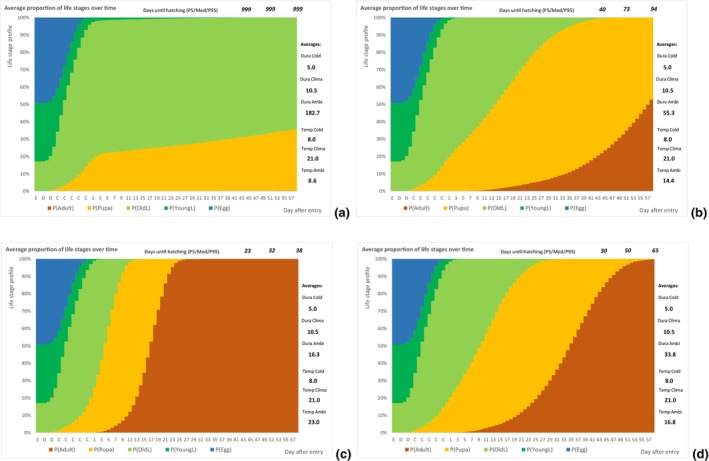

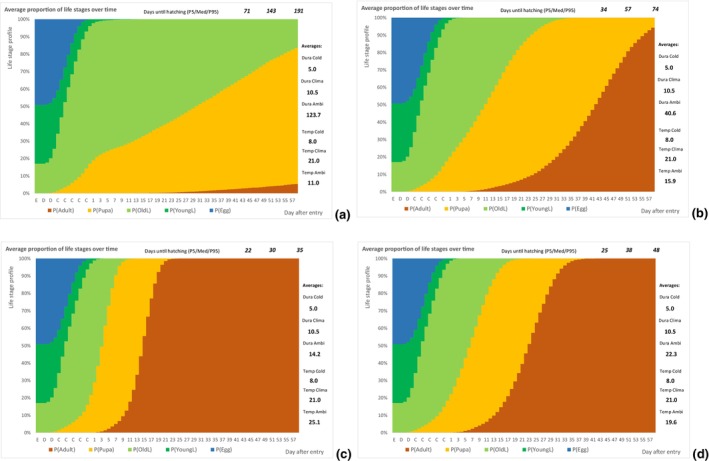

The developmental model of T. leucotreta after entry into the EU (start at the border) estimates the number of T. leucotreta adults emerging in the importing country considering three sequential compartments:

-

Transport and storage under cold conditions. This compartment includes the handling after entry, cold transportation to the region for consumption, and cold storage there. After harvest and sorting on site in Africa, cut roses are stored in water at a temperature of 2–6°C. As a result, the moisture content is maintained. During transport by truck/trailer, a constant temperature of 4–6°C and humidity level (60–80%) is maintained to deliver the flowers to destinations in optimal condition (at 4°C ± 1°C, Flower Watch, 2011; Carrier Transicold, 2022). Temperatures, however, may fluctuate for short periods during handling (up to 8°C) and reloading (short periods up to 16°C) from storage into transport and from trucks into the aircraft cabin (Flower Watch, 2011; Carrier Transicold, 2022) Cut roses are mainly transported by air freight. A total turnover time from the grower up to and including the auction takes between 1 and 2 days by air transport (Flower Watch, 2011; Carrier Transicold, 2022). Upon arrival in Europe (mostly the Netherlands), the time from purchasing trade to the retailer takes a maximum of ~ 4 days at a temperature of 8°C ± 1°C, 75% RH.

During the whole chain from grower to retailer, a constant temperature of 8°C is assumed as a conservative (i.e. worst) scenario.

The duration of cut roses in this model compartment assumes a triangular distribution with parameters minimum, most likely and maximum equal to 1.0, 4.5 and 8.0 days, respectively, that adequately describe the uncertainty in the duration of transport. These values were also set considering the interest in keeping the transport time as short as possible by the flower industry. Additionally, the cold storage at the final place of sales to consumers is part of this compartment. It should be noted that even considering the extreme values for temperature and duration, transportation and cold storage do not support full development of T. leucotreta.

-

Retail and private home under climatisation. This compartment includes the provision to and the use of the flowers by the consumer.

Vase life at the consumer is aimed at a period of 7.0–10.0 days for imported cut roses (VBN, 2017; Harkema et al., 2017) and 2 weeks for locally produced cut roses (FloraNews, 2015), but can vary between 4.0 and 14.0 days (Yakimova et al., 1996; Ichimura et al., 2006) Hence, the duration of cut roses in this compartment was modelled assuming a triangular distribution with parameters minimum, most likely and maximum equal to 7.0, 10.5 and 14.0 days, respectively. Temperature in this compartment is assumed to be set to the ideal temperature values for human living and therefore modelled assuming it could adequately be described by a triangular distribution with parameters minimum, most likely and maximum equal to 18.0, 21.0 and 24.0°C, respectively.

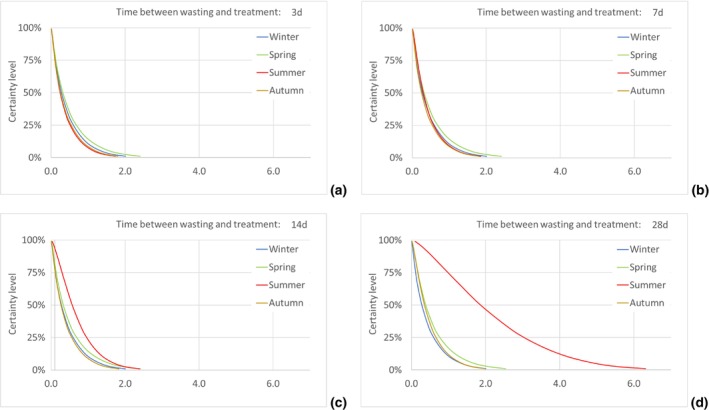

Organic waste at ambient temperature. This compartment comprises the situation after waste disposal by the consumer. It is assumed that the temperatures are ambient according to the regional and seasonal situation. Due to missing information on the duration within this compartment, four scenarios for the time between waste disposal and waste treatment are constructed: 3, 7, 14 and 28 days (see the waste model in Section 2.3.3).

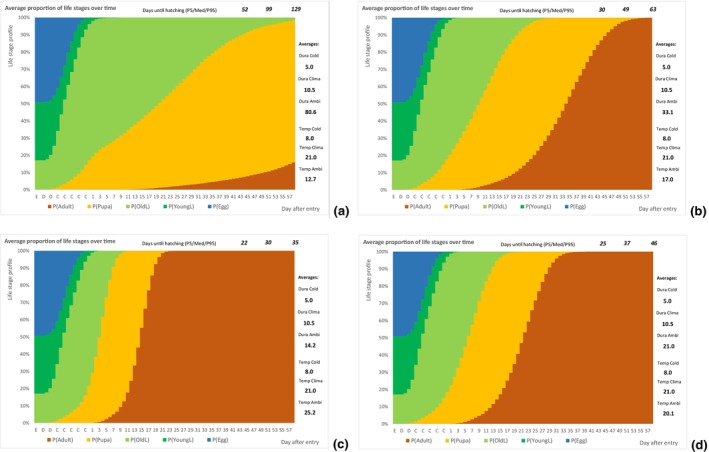

A diagram presenting the compartment model (time on the horizontal axis) for the developmental model is outlined in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Visualisation of three phases of development after entry of cut roses. The blue axis at the bottom represents the time axis and three phases: (1) transport, (2) vase life, (3) post‐waste disposal. The red boxes on top represent the assumed temperature during each phase, while the blue boxes at the bottom represent the duration. The dotted line in the middle of the graph indicates how larvae on the roses progress through their life stages during the three stages of the cut roses pathway, from production to waste.

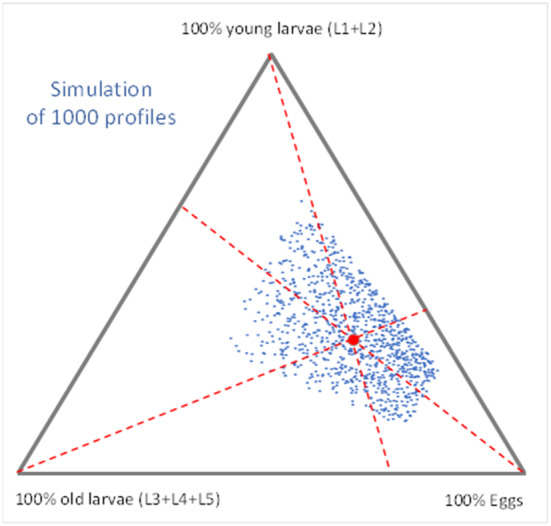

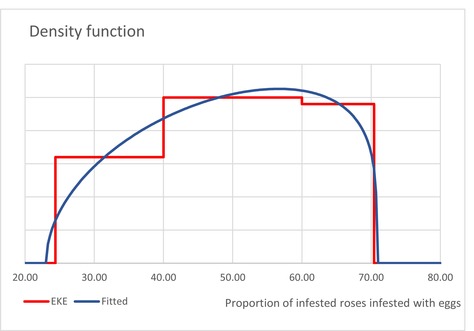

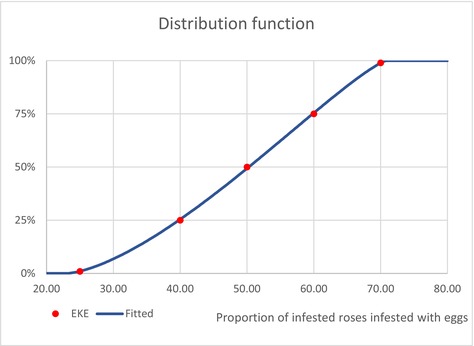

The following simulation process was done using @RISK software version 7.6 (see Appendix C): An individual of T. leucotreta will enter the EU at a specific life stage. According to the temperature, the individual will develop each day a bit, additionally depending on a random component related to the insect and host conditions (see @RISK file data Appendices). Individuals will develop through successive life stages accordingly. When emerging from the pupae, the adult moth will escape the cut rose or waste. The day of escape was simulated for 10,000 T. leucotreta arriving in the EU. The simulation results in a profile of life stages for each day after entry, or the proportion of adults for a fixed day depending on the ambient temperatures for specific climate suitability classes and seasons. A description of the parameters used to inform the developmental model is presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

Description and source of evidence for the parameters used in the developmental model

| Parameter | Description | Source | Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESCtime, xd, CSClass, Season | Proportion of T. leucotreta which will escape the cut roses until x days (x = 3, 7, 14 or 28 days depending on the scenario) after initial disposal (at day 15) in a region of a specific climate suitability class and season | Calculated | |

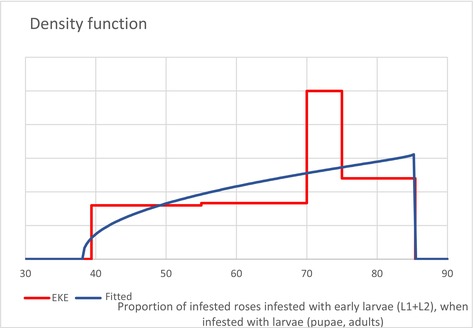

| PropEggs PropYoung/all larvae | Proportion of T. leucotreta life stages, when arriving at the border | EKE question 1a and 1b (Appendix A Section A.8) | GENERALBETA |

| Maturity | Level of maturity within a specific life stage, when arriving at the border | Uninformative on age | UNIFORM |

| DevelopLifeStage,Temp Condition | Daily development of a specific life stage according to the temperature and a random component related to the insect and host conditions. Reciprocal of the duration of the specific life stage at a specific temperature. The condition is the position within a range of values | Scientific literature | TRIANGULAR with correlation of the life stages |

| TemperatureCompA TemperatureCompB TemperatureCompC | Temperature during the stay in a compartment. For compartments A and B, the temperature is assumed as constant, while for compartment C, the temperature may change every day | Default values for compartment A and B, seasonal weather data for 2001–2010 (at NUTS2 level) | TRIANGULAR |

| DurationCompA DurationCompB | Duration of the stay in compartments A and B | Default values according to the objectives of the flower industry | TRIANGULAR |

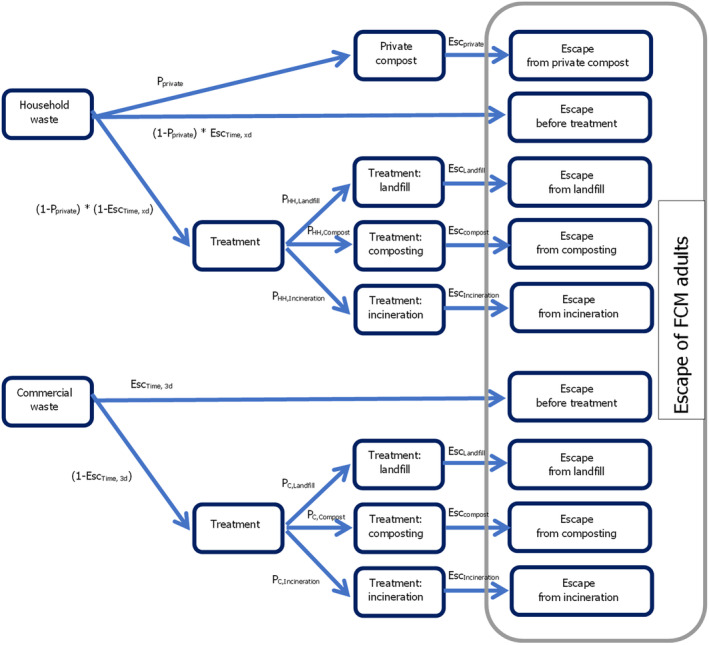

2.3.3. The waste model

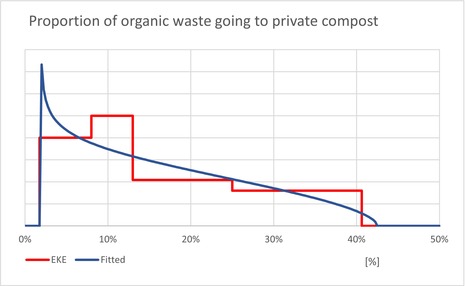

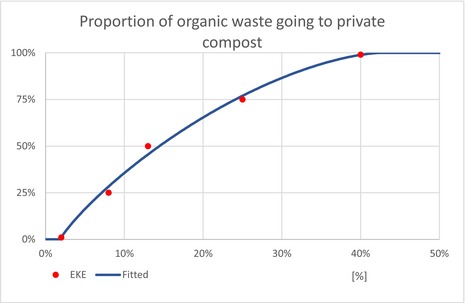

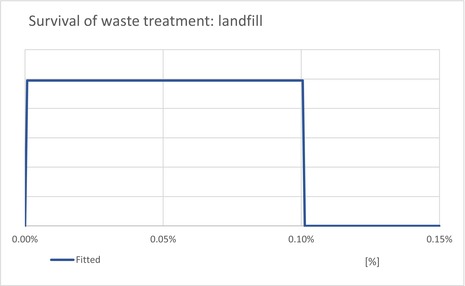

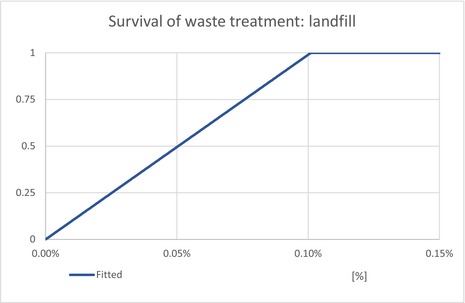

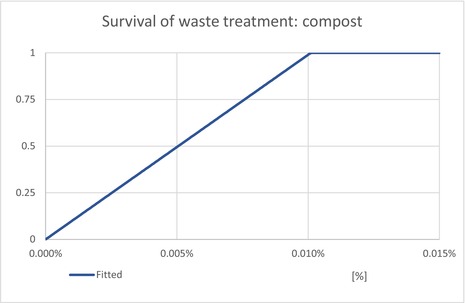

The waste model estimates the proportion of T. leucotreta that survive and escape different waste treatments: private compost and the communal treatments (landfill, composting and incineration/anaerobic digestion). The proportion of each treatment is estimated for household and commercial (sorted vegetal) waste.

Because no data on the duration from initial disposal to waste treatment for normal household waste were available, and a dependence on local conditions is assumed, the calculations were done for four different times: treatment 3.0, 7.0, 14.0 and 28.0 days after initial disposal at the household.

To model the escape of T. leucotreta moths before the treatment of the waste, four scenarios for the collection of household waste are calculated:

Scenario 1: Fast collection and treatment of household waste. In this scenario, treatment occurs 3 days after initial disposal (day 18 after entry). This is a ‘best case’ scenario where consumers would take their waste for collection on the same day that the cut roses were disposed of, and waste is also collected within 24 h and treated without delays.

Scenario 2: Treatment occurs 7 days after initial waste disposal (day 22 after entry). This is for example the case where roses are kept for a few days in the waste bin at private consumers before being taken out for collection. The rest of the waste management chain runs smoothly with a possible 1‐ or 2‐day delay between collection and treatment.

Scenario 3: Treatment occurs after 14 days after initial disposal (day 29 after entry). This is a scenario assuming more severe delays, e.g. when roses are kept for a few days in the waste bin at the private consumer's before being taken out for collection. At the same time, there is a delay in either the waste collection or treatment, e.g. by intermediate storage.

Scenario 4: Slow collection and treatment of household waste. In this scenario, treatment occurs 28 days after initial disposal (day 43 after entry). This should be regarded as the ‘worst‐case’ scenario in which long delays occur and there is maximum opportunity for T. leucotreta adults to escape from waste. For example, the waste is not taken out for collection every week and/or there is a longer storage in the waste management chain before the treatment.

For the commercial waste, the Scenario 1 (3 days after initial disposal) is assumed. The pathway of the waste model is presented in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Pathway model for the waste management component (see text below, Table 8 and Appendix A for details)

The overall number of T. leucotreta individuals/year escaping from the household or commercial waste were therefore calculated as the escape from private compost, escape from household waste before the treatment and escape during the three types of treatment: landfill, composting or incineration.

Additionally, T. leucotreta may escape the commercial waste. This may happen before the treatment (within 3 days after wasting), or during the different types of treatment.

A description of the parameters used to inform the waste model is presented in Table 8.

Table 8.

Description and source of evidence for the parameters used in the waste model

| Parameter | Description | Source | Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESCHousehold, NUTS2, Season | Proportion of T. leucotreta, which will escape the cut roses used at consumer level or household waste | Calculated | |

| ESCCommercial, NUTS2, Season | Proportion of T. leucotreta, which will escape the commercial waste of cut roses | Calculated | |

| Pprivate | Proportion of household waste, which goes to private composting (not subjected to regional waste treatment) | EKE question 3 (Appendix A.9) | GENERALBETA |

| ESCtime, xd, CSClass, Season | Proportion of T. leucotreta, which will escape the cut roses until x days after initial disposal in a region of a specific climate suitability class (CSClass) and season | Calculated by the developmental model | |

| PHH,Landfill,country PC,Landfill,country | Proportion of household (HH) or commercial (C) waste treated by ‘landfill’ | Eurostat waste treatment for household or vegetal waste (Appendix A.9.2 and A.9.3) | CONSTANT |

| PHH,Compostl,country PC,Compostl,country | Proportion of household (HH) or commercial (C) waste treated by ‘composting’ | Eurostat waste treatment for household or vegetal waste (Appendix A.9.2 and A.9.3) | CONSTANT |

| PHH,Incineration,country PC,Incineration,country | Proportion of household (HH) or commercial (C) waste treated by ‘incineration or anaerobic digestion’ | Eurostat waste treatment for household or vegetal waste (Appendix A.9.2 and A.9.3) | CONSTANT |

| ESCprivate | Proportion of T. leucotreta, which will escape private compost | Conservative assumption | CONSTANT = 100% |

| ESCLandfill | Proportion of T. leucotreta, which will escape waste treated by ‘landfill’ | EKE question 4a (Appendix A.9.4) | UNIFORM |

| ESCCompost | Proportion of T. leucotreta, which will escape waste treated by ‘composting’ | EKE question 4b (Appendix A.9.4) | UNIFORM |

| ESCIncineration | Proportion of T. leucotreta, which will escape waste treated by ‘incineration or anaerobic digestion’ | EKE question 4c (Appendix A.9.4) | CONSTANT = 0% |

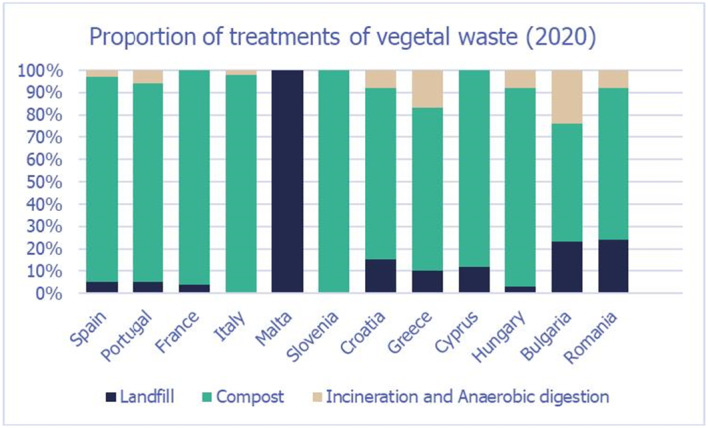

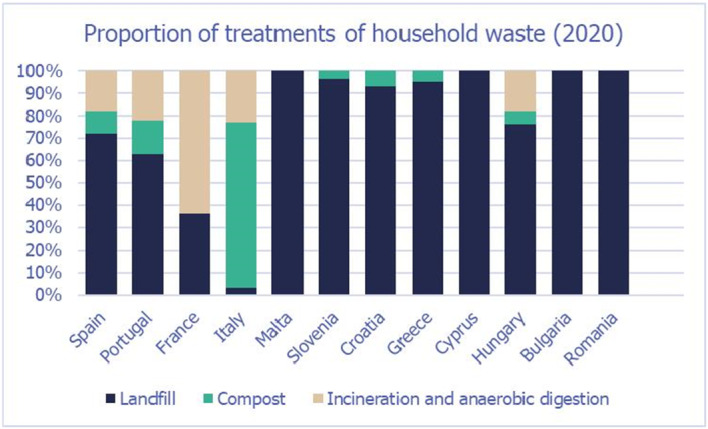

Waste treatments for both commercial and household waste include landfill, composting (and home composting), incineration or anaerobic digestion. A high variability in the proportions of waste treated by the different methods occurs across MSs, particularly in relation to the household waste (Figures 9 and 10).

Figure 9.

Proportion vegetal waste 5 treated as landfill, compost and incineration/anaerobic digestion in the European countries considered in the assessment

Figure 10.

Proportion household waste treated as landfill, compost and incineration/anaerobic digestion in the European countries considered in the assessment

5 For each type of treatment, EKE was used to determine the proportion of T. leucotreta that survives and escapes the treatment. The main characteristics of the different treatments are described in Appendix A.9. This information was used as part of the evidence for the expert judgement on: (i) proportion of organic waste going to private composting (Appendix A section A.9), (ii) survival rate of T. leucotreta at landfill, during composting and incineration/anaerobic digestion (Appendix A Sections A.9.4, A.9.5 and A.9.6).

For the scope of the opinion, the following assumptions were made: (i) Public waste management is also applicable for cut roses wasted by private consumers and (ii) commercial waste of cut flowers will be handled as treatment of vegetal waste.

2.3.4. The overall entry model

The overall model for entry combines the three submodels and calculates the average number of T. leucotreta adults escaping from cut roses over all seasons according to the equation below.

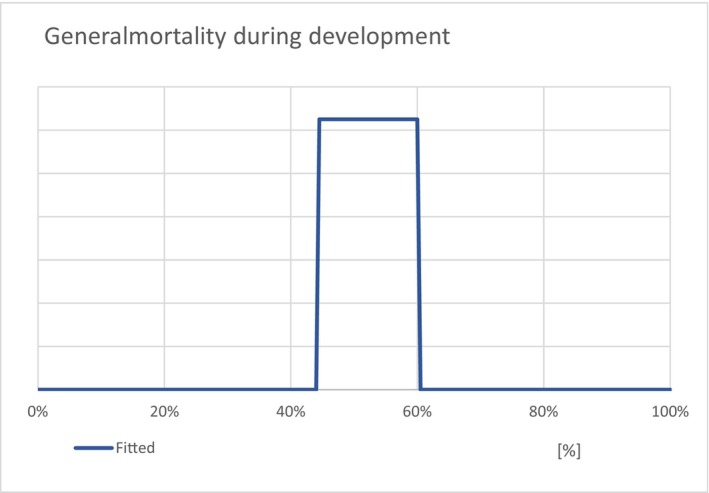

To adjust for the natural mortality occurring during the development of the insect along the pathway, an overall mortality factor of 44–60% was introduced that reduced the total number of escaping adults.

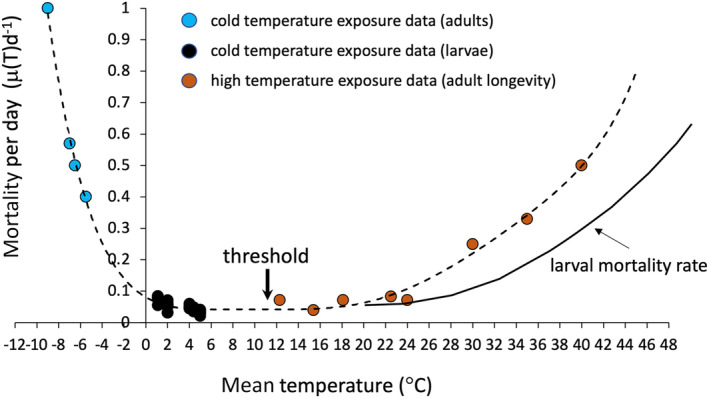

Neither data nor information were found in the scientific and grey literature on the mortality of T. leucotreta in cut roses or in organic waste; however, in other commodities (sweet orange and sweet pepper, see Section 3.1.2), a larval mortality range was reported between 25% and 37%. Data or information on pupal mortality rate for T. leucotreta are also lacking; however, the Panel assumes that for T. leucotreta the pupal mortality and the larval mortality are comparable, as it is the case for other Tortricidae species (Milonas and Savopoulou‐Soultani, 2000, Gutierrez et al., 2012). Therefore, as there are no data on mortality of T. leucotreta in cut roses and in organic waste and considering also that the temperature‐dependent mortality remains low in the range of temperatures experienced by cut roses from entry to disposal (see Figure 16), a mortality rate between 25% (such as in sweet oranges) and 37% (sweet pepper) for developing larvae at 25.0 ± 2.0°C was used as a lower bound of the overall mortality for larvae in the cut roses pathway. Further assuming that the mortality range (25–37%) would be similar also for pupae, an overall mortality range of 44–60% from larvae to pupae was estimated and applied overall to the entry model results on the numbers of adult moths predicted to escape per year.

Figure 16.

The biodemographic functions for larval and adult temperature‐dependent mortality (source: Myburgh, 1965; Daiber, 1980; Boardman et al., 2012, 2013; Moore et al., 2016, 2022) with the 4°C displacement of larval mortality rates (see Terblanche et al., 2017) indicated as a solid line. Same mortality function was assumed for eggs and pupae (see, e.g. for other Tortricidae species: Milonas and Savopoulou‐Soultani, 2000, Gutierrez et al., 2012)

Descriptions of the parameters used in the overall model are reported in Table 9.

Table 9.

Description and source of evidence for the parameters used in the final model

| Parameter | Description | Source | Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| FCMEscape, NUTS2 | Annual average number of T. leucotreta adults escaping from cut roses imported from AF (African countries with FCM occurrence and Israel) in a specific NUTS2 region | ||

| Mortnatural | Natural developmental mortality |

Observed larval mortality on other crops Extrapolation to pupae |

UNIFORM |

| FCMCommercial, NUTS2, Season FCMHousehold, NUTS2, Season | Number of FCM T. leucotreta individuals ending in commercial or household waste in a NUTS2 region climatically suitable in a specific season | Calculated in the distribution model | |

| ESCHousehold, NUTS2, Season | Proportion of T. leucotreta which will escape the cut roses used at consumer level or household waste | Calculated in the waste model | |

| ESCCommercial, NUTS2, Season | Proportion of T. leucotreta which will escape the commercial waste of cut roses | Calculated in the waste model |

Results of the overall model are expressed as average number of adult escapes per NUTS2 region with suitable climatic conditions for establishment.

To provide an interpretation of the results in terms of possible mating under different level of clustering, the results of the final model are also transformed to represent two scenarios:

Cluster Scenario 2: Clustering in bunches of 10 roses as defined in Section 2.2.3. Under this scenario, a mating will happen for every 435 escaping T. leucotreta (No. mated femalesNUTS2/year = FCMEscape, NUTS2/435) (see results in Sections 3.4.1 and 3.4.2 and in Appendix A Sections A.1.2 and A.1.3).

Cluster scenario 3: No temporal or spatial clustering and all escaping adults are homogeneously distributed within the residential area of a NUTS2 area and throughout a year. To this end, the average number of adult escapees is standardised to a circle of a 1‐km radius (flying radius of T. leucotreta males), considering only the residential area of each NUTS2 regions during a time of 10 days (because the majority of eggs are laid within the first 10 days of female adult stage) (see results in Section 3.4.3 and in Appendix A Section A.1.4).

Results transformed as the number of mated females NUTS2/year are presented for the EU and some selected NUTS2 regions as disaggregated values by season for all scenarios of time between waste disposal and waste treatment (i.e. 3, 7, 14 and 28 days).

To combine the uncertainties in the model parameter (expressed as distributions), the model is implemented in a Monte‐Carlo simulation 10,000 times (using @RISK version 7.6) (see Appendix D).

2.3.5. Uncertainties of entry

Uncertainties on entry are generally quantitatively assessed in the model and in the EKE. Aspects not quantified and assumptions are described in Section 3.3. To identify the parameters of the pathway model driving most of the uncertainty on the output estimates, a sensitivity analysis was conducted on each scenario (3, 7, 14 and 28 days) by calculating the relative decomposition of R2 from the calculated correlation coefficients between inputs and outputs.

2.4. Establishment

2.4.1. Climate suitability methodology

In the EPPO PRA for T. leucotreta (EPPO, 2013), a CLIMEX compare locations model was explored but then abandoned because of lack of knowledge on factors influencing winter survival and the climatic limits of its distribution. A simple rule based on diurnal temperatures (based on the difference between weekly maxima and minima) was adopted although recognising its uncertainty (as it was based on very few locations and there was uncertainty of the characteristics of the coldest winter that T. leucotreta could survive).

Other quantitative approaches to assess T. leucotreta establishment were found in literature but not all addressing the EU region (Table 10 below). The Panel used two approaches for assessing the area of potential establishment of T. leucotreta. The first is the Köppen–Geiger climate classification (MacLeod and Korycinska, 2019) matching climate categories in the EU with those in locations where T. leucotreta is known to occur in Africa and Israel (see Section 2.2.1 and Figure 1). The second is a physiologically based demographic model (hereinafter referred to as PBDM; Gutierrez, 1996).

Table 10.

Methodological approaches to model climate and niche suitability of T. leucotreta

| Model basis | Source | EU data |

|---|---|---|

| Host presence + pest occurrence + climate characteristics | EPPO (2013) | Yes, map |

| Pest occurrence + climate categories | (Köppen–Geiger) in this EFSA Scientific Opinion; Rossi et al. (2023) | Yes, map (Figure 23) |

| Pest occurrence + host presence | Venette et al. (2003) | None |

| Pest occurrence + degree‐days + host presence | Li et al. (2022) | Yes, map (pers.comm, Figure 27) |

| Pest biology+Degree‐day + cold stress (CLIMEX) | Barker and Coop (2019) | Yes, map (pers.comm) |

| Physiologically based demography | Gutierrez and Ponti (2013, 2023a,b) | Yes, map (Figure 25 and Figure 26) |

In this document, the establishment is measured in terms of interannual average abundance of life stages of the pest, given entry. Establishment is interpreted as the similarity of predicted pest abundance (output of the PBD Model) for EU regions in comparison with after invasion locations that report establishment of the pest in newly invaded areas in South Africa and Israel (Giliomee and Riedl, 1998; Hofmeyr et al., 2015).

2.4.2. EPPO PRA

The EPPO PRA led to the following conclusions.

Based on the assumption that the capacity to survive cold stresses during the winter is the key climatic factor influencing the establishment in the EPPO region and the finding that, in the South African locations where T. leucotreta is known to occur with the minimum lowest winter temperature, maximum temperatures in the winter are up to 15–17°C, a simple rule was applied to estimate EPPO regions where the climate was suitable for T. leucotreta. As a result, according to the conclusions of EPPO (2013), not only the known distribution in South Africa and the Israeli coastal plain, but also parts of the Mediterranean coast in Europe (Spain, Italy [Sicily], Malta and Cyprus) and North Africa (Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia) together with Portugal, the Canary Islands, Azores and Jordan were shown to have temperatures above the threshold. It was deemed possible that T. leucotreta can establish in a wider area in the EU because of limited knowledge of T. leucotreta cold tolerance and the fact that recent climatic data suggest that the threshold is also likely to be exceeded in southern France, e.g. Corsica, and larger areas of southern Portugal, Greece (Crete), Spain and Italy. Based on this rule, in areas further north in Europe, conditions are too cold (low minimum temperatures below 0°C, or absolute/mean minimum temperatures in January, as low as 1–3°C) and not coupled by maximum temperatures within the 15–18°C range or warmer. However, up to about 55° of latitude north, sufficient degree days above the minimum development threshold of 12°C may accrue during warmer periods for T. leucotreta to complete at least one transient generation (EPPO, 2013).

2.4.3. Previous climate suitability assessments

Although the potential establishment range of T. leucotreta was assessed with different methodologies, the exploited data were similar and limited to development + fecundity (Daiber, 1979a,b,c) and cold stress data for certain life stages (Stotter and Terblanche, 2009). The methodologies differ from each other regarding whether the suitability was estimated based on observed presence or, by the predictive interpretation of the set of experimental data as drivers of the population development over generations (see Table 10).

2.4.4. Climate matching based on the Köppen–Geiger climate classification

The climate matching approach based on the Köppen–Geiger climate classification maps areas including climate types that fulfil two conditions: (i) the organism has been found to occur in them in its endemic range, (ii) the climate type occurs in EU. Thus, if the organism occurs in a climate type that does not occur in the EU, this climate is not mapped as a relevant climate for the assessment. The Panel used the implementation of Köppen–Geiger climate classification currently available in SCANClim (EFSA and Maiorano, 2022, published by the Institute for Veterinary Public Health of the University of Vienna (Kottek et al., 2006), for the period 1986–2010, rescaled after Rubel et al. (2017) (https://koeppen-geiger.vu-wien.ac.at/present.htm).

2.4.5. Physiologically based demographic model

The climate matching with Köppen–Geiger classification was difficult to interpret because one climate zone intersected with the occurrence data on the African continent to a small extent, which would add all middle and northern EU MS to the climatically suitable area for establishment. Therefore, the EU territory was assessed using a physiologically based demographic model (PBDM; see CASAS Global https://www.casasglobal.org/). This approach models the potential establishment of the pest from the physiological response of its developmental stages to daily weather, using daily climatic variables as input. The approach does not rely on occurrence records. The technique is taken from the literature with several applications to other pests (see e.g. Gutierrez and Ponti, 2013, 2023a,b).

PBDMs are based on the notion that analogous weather‐driven submodels for resource acquisition and birth–death dynamics can be used to predict explicitly the biology and dynamics of heterotherm species across trophic levels (Gutierrez & Baumgärtner, 1984; Gutierrez, 1992, 1996; Gutierrez and Ponti, 2023b). When driven by site specific daily weather, PBDMs predict the phenology, age structure and abundance dynamics of the target species (e.g. an invasive insect herbivore) and as appropriate of interacting species in its food web (e.g. its host plant and natural enemies) across wide geographic areas (see Gutierrez et al., 2008, 2010).

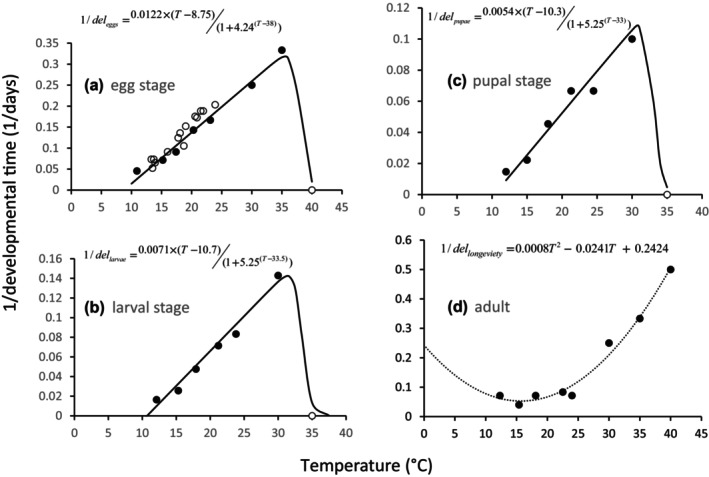

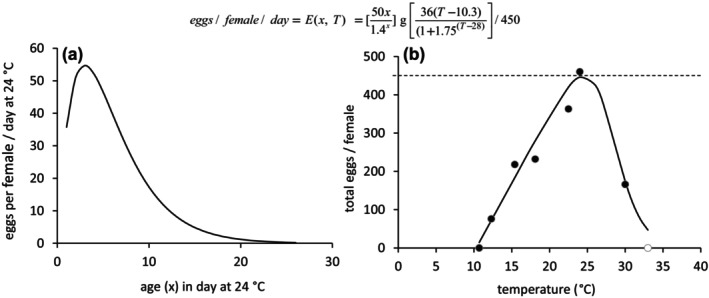

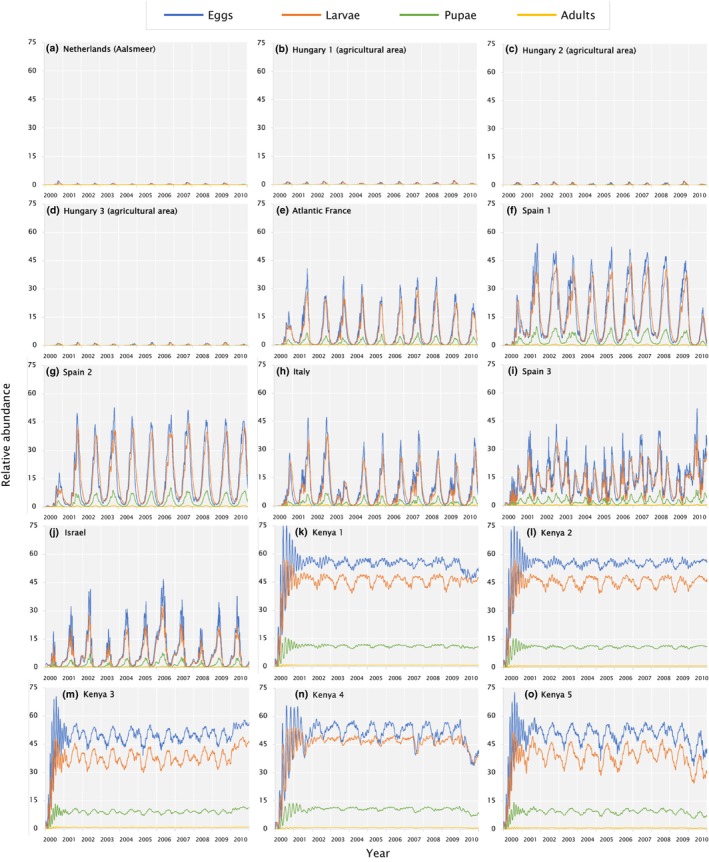

The technical model documentation can be found in Appendix B of this scientific opinion. The model characteristics are summarised according to the POE protocol (Purpose, Overview, Evidence) (Grimm et al., 2020). Purpose of the PBD Model: a temperature‐driven version of the PBDM (see Gutierrez and Ponti, 2013) was implemented to exploit local differences in climate on the scale of about 0.25° × 0.25° for predicting the average annual level of the life stages of T. leucotreta in the EU, the Mediterranean Basin and Africa, using 10 consecutive years of daily maximum and minimum temperature values (years 2001–2010) as driver of daily T. leucotreta biology. Overview: The model describes the growth and survival of local pest populations (on a 0.25° × 0.25° latitude/longitude grid resulting in horizontal resolution of about 25 km) based on interpreted temperature‐dependent development, fecundity and mortality data available from the literature across all life stages of the pest (see Section 3.1). With daily resolution, the thermal biology data of the four developmental stages of T. leucotreta were summarised using biodemographic functions for development, fecundity and mortality (see Box 1 below and Appendix B). Biodemographic functions of T. leucotreta with available data are temperature‐dependent developmental rates, per capita lifetime reproductive profiles and temperature‐dependent mortality rates (see Section 3.1).

Box 1. Biodemographic functions used in the PBD model of T. leucotreta.

Oviposition profile on age x = days at 24°C times a scalar for the effects of temperature.

Stage developmental rates on temperature (delstage):

Temperature (T) dependent mortality rate:

Polynomial mortality function for all stages (μstage):

Modification for larval temperature tolerance (τ; displacement of mortality curve):

Density‐dependent predation mortality in eggs/pupae/adults (Lx):

Erlang parameters:

kegg = klarvae = kpupae = 25 (age classes of each stage, see Appendix B)

kadult = 15 (age classes of the adult stage, see Appendix B)

Mean developmental times (degree days > threshold):

eggs (86.1dd > 8.75°C)

larvae (148,8dd > 10.7°C)

pupae (185.2dd > 10.3°C)

adult females (191.8dd > 10.3°C)

Adult immigration rates (adultimmigration)

Sex ratio = 0.5

The growth and abundance of the pest at a geographic location emerge from the daily minimum and maximum temperature values (AgMERRA daily weather data; see Ruane et al., 2015) and a background density‐dependent mortality term on all stages but larvae which are inside the rose bud. Local population may go extinct during extended frost/cold periods. In the model, new introduction of adults at very low levels is immediately assumed when daily temperature, T, is above 11°C. The model is analysed in each spatial unit in discrete daily steps evaluating the life stage cohorts independently. The model output per 25 × 25 km spatial unit refers to the (average) number of pupae over 10 consecutive years of temperature data and pest population dynamics. For selected locations across the EU, the physiologically based pest abundance is shown by multi‐annual time‐series plots to understand qualitative differences on the prospective local population dynamics of the pest.

Evidence: The PBDM of T. leucotreta is adapted from an established modelling framework in support of QPRA of different pests and the modelling approach has repeatedly been validated with the occurrence or occurrence‐based models of other pests (see e.g. Gutierrez and Ponti, 2013, 2023a,b). Likewise, the model output of the T. leucotreta version was assessed with the occurrence reports of indigenous and invasive T. leucotreta in Africa and Israel. The approach could predict positive densities of T. leucotreta for the regions with pest observations, in both indigenous and invaded locations (see Appendix B).

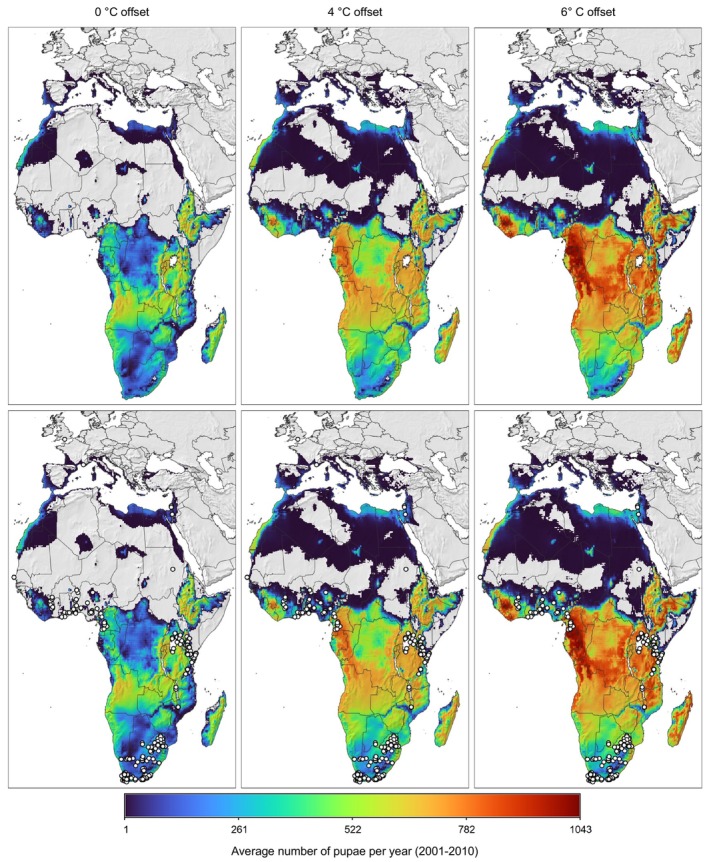

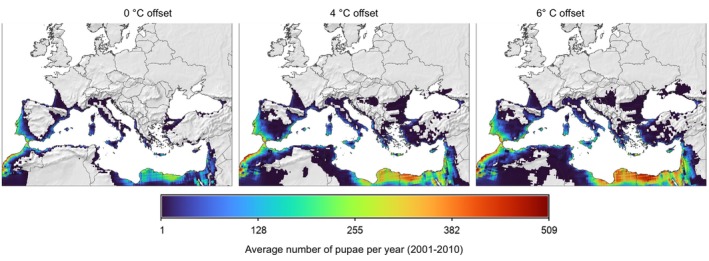

The model was modified to explore the impact of higher thermal tolerance of the larval stage when compared to the adult stage (see Box 1, modification for larval temperature tolerance). Literature provides strong indication of higher thermal tolerance of larvae (Uys, 2014; Terblanche et al., 2017), but data are not sufficiently detailed. Therefore, model scenarios were considered using different larval thermal tolerance. The displacement of larval temperature‐dependent mortality curve by 4°C resp. 6°C facilitated the explanation of T. leucotreta occurrence records in western parts of Africa (Table 11 and Figure 11). However, the physiological aspect is of marginal relevance to predictions for EU climates, as the main constraint to T. leucotreta distribution in Europe is cold weather and the absence of dormancy in the pest (Terblanche et al., 2014).

Table 11.

Comparison of average number of pupae per year in the period 2001–2010, as projected by the PBDM model, under three scenarios of larval heat‐stress mortality being displaced by 0°C, +4°C and 6°C. Percentages in brackets compare model predictions to observations

| Continent/Country | Number of T. leucotreta observations with geographical coordinates | No of T. leucotreta observations with predicted no pupae > 1 in scenario + 0 | No of T. leucotreta observations with predicted no pupae > 1 in scenario +4°C | No of T. leucotreta observations with predicted no pupae > 1 in scenario +6°C |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| African continent | 468 | 412 (88%) | 446 (95%) | 448 (96%) |

| Southern Africa | 265 | 264 (99.6%) | 265 (100%) | 265 (100%) |

| Eastern Africa | 123 | 112 (91%) | 115 (93%) | 115 (93%) |

| Western Africa | 46 | 9 (19.6%) | 41 (89%) | 43 (93%) |

Figure 11.