Abstract

Anti-Hu antibodies are associated with autoimmune syndromes, mainly limbic encephalitis, encephalomyelitis, and painful sensory polyneuropathy (Denny-Brown). We report the case of a 15-year-old boy presenting with epilepsia partialis continua (EPC) found to have a right middle frontal gyrus brain lesion without atrophy or contralateral involvement. After partial resection, neuropathology revealed neuronal loss, reactive gliosis and astrocytosis, and perivascular mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate and features of neuronophagia resembling Rasmussen encephalitis. Suboptimal response to antiseizure drugs and surgery prompted further workup with identification of positive serum anti-Hu antibodies and a mediastinal seminoma. The patient was treated with immunotherapy including steroids, IV immunoglobulin, azathioprine, rituximab, plasmapheresis, and mediastinal lesion resection. However, he continued to experience EPC and psychomotor impairment along with left hemiparesis and dysarthria. Given clinical progression with failure to respond to immunotherapy and antiseizure polytherapy, hemispherotomy was attempted and seizure freedom achieved. A review of the literature found only 16 cases of neurologic presentations associated with anti-Hu antibodies in children, confirming the rarity of EPC in these cases. Thus, this report provides a new observation of germ cell mediastinal tumor associated with anti-Hu antibodies in children, broadening the spectrum of anti-Hu–associated neurologic disorders in children and highlighting the importance of considering antineuronal antibody testing in children presenting with EPC and brain lesions suggestive of Rasmussen encephalitis.

Anti-Hu antibodies are associated with autoimmune syndromes, mainly limbic encephalitis, encephalomyelitis, and painful sensory polyneuropathy (Denny-Brown). We report the case of a 15-year-old boy diagnosed with a mediastinal seminoma presenting with epilepsia partialis continua (EPC).

Case Report

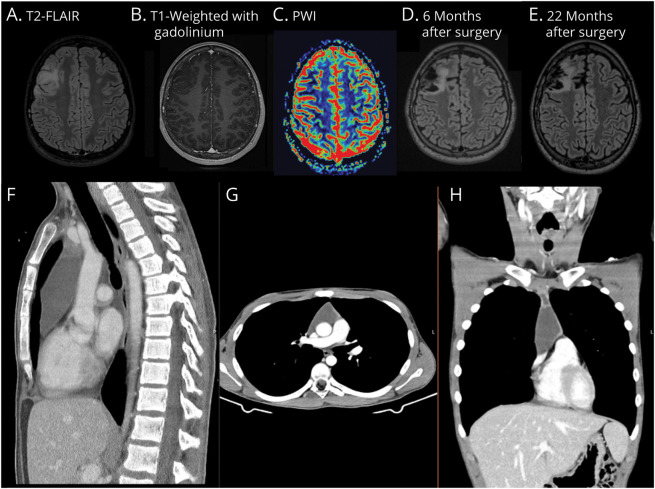

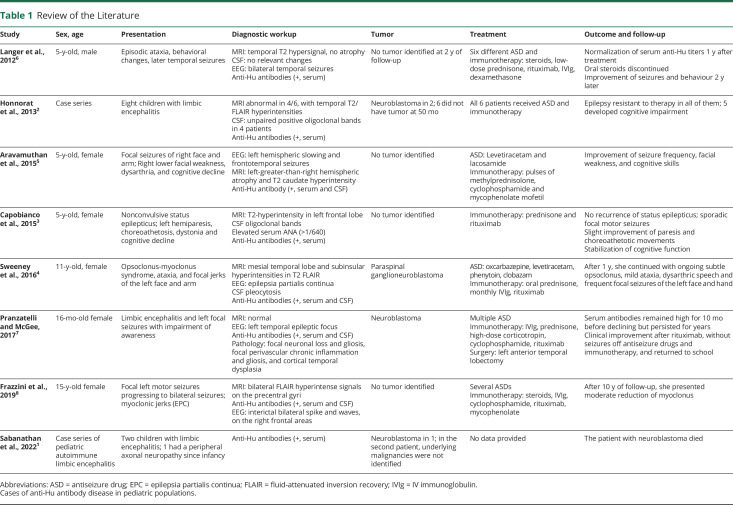

A 15-year-old typically developing boy with no relevant medical history presented with focal-onset seizures with impaired awareness characterized by clonic movements of the left arm and face. Diagnostic workup included brain CT scan, brain MRI, and EEG, which were initially unremarkable. Seizure frequency continued to increase despite treatment with multiple antiseizure drugs (ASDs), evolving into uninterrupted myoclonic jerks of the left hand, compatible with EPC. A follow-up brain MRI scan 5 months later revealed a hyperintensity signal on T2-weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) in the right middle frontal gyrus, without gadolinium enhancement or increase in relative cerebral blood volume on perfusion imaging, suggesting a low-grade infiltrative lesion (Figure 1, A–C). No associated brain atrophy was found. The patient underwent a partial resection of the brain lesion. Neuropathology showed neuronal loss, reactive gliosis and astrocytosis, and perivascular mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate and features of neuronophagia (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Neuropathology.

Pathology analysis discloses increased cellularity and exuberant vascular network (HE: 100×) (A), neuronophagia (HE: 400×) (B), perivascular mononucleated inflammatory infiltrate (HE: 200×) (C), and gliosis with reactive astrocytosis (GFAP: 400×) (D). GFAP = glial fibrillary acidic protein; HE = hematoxylin and eosin.

After surgery, he continued to experience myoclonic jerks of the left hand, a mild left central facial palsy, and Medical Research Council grade 4 left arm motor strength. EEG now showed a focal slowing in the right frontal region with 2–3 Hz irregular activity and periodic sharp waves synchronous with the hand movements. Considering symptom persistence and the histologic analysis, a comprehensive workup was performed. CSF analysis showed 3 white blood cells, normal protein level (0.22 g/L), and 58 mg/dL of CSF glucose with 84 mg/dL of serum glucose. Systemic autoimmune studies and common infectious causes of encephalitis were unremarkable (eTable 1, links.lww.com/WNL/D19). Neuronal antibody testing revealed highly positive anti-Hu antibodies in the blood but was negative for other antibodies (eTable 1). Given anti-Hu antibodies, the patient was treated with 1 g of IV methylprednisolone (5-day course), followed by 2 g/kg of IV immunoglobulin (IVIg) (2-day course), 40 mg of oral prednisone with slow progressive tapering, and then 150 mg of azathioprine daily. However, he continued to exhibit EPC with brachiofacial involvement. ASDs were progressively uptitrated to 40 mg/kg of valproic acid, 200 mg of lacosamide bid, 8 mg of perampanel, and 20 mg of clobazam. Given the suboptimal clinical response, 375 mg/m2 of IV rituximab was initiated alongside monthly courses of IVIg.

In the context of paraneoplastic screening, a chest, abdomen, and pelvis CT scan were performed, and a large thymic mass with 53 × 35 × 90 mm was found (Figure 1, F–H). Testicular ultrasonography and serum germinative neoplastic biomarkers (carcinoembryonic antigen, alpha-fetoprotein, and human chorionic gonadotropin) were unremarkable. The patient underwent complete resection of the mediastinal mass, and pathologic analysis confirmed a mediastinal germ cell tumor compatible with a seminoma. Physical rehabilitation therapy was initiated along with psychological support. Repeat evaluation of serum antibodies revealed a continued positive anti-Hu antibody, although decreased immunohistochemical staining compared with the first assessment. Chest imaging reassessment was negative for neoplastic relapses. After multidisciplinary discussion, disease monitoring with regular imaging was adopted.

Despite a transient initial improvement, 9 months after mediastinal seminoma resection, the patient’s condition started to deteriorate including psychomotor impairment, significant functional impairment of his left hand due to seizures and weakness, and dysarthria. EEG-confirmed frequent brachiofacial myoclonic jerks were EPC with occasional generalization. There was no epileptiform activity or abnormal activity from his left hemisphere. Follow-up brain MRI scans at 6 (Figure 1D) and 22 (Figure 1E) months revealed increase in frontal right T2/FLAIR hyperintensity in addition to postsurgical inflammatory changes and a mild symmetric bilateral hemispheric atrophy. No progressive hemiatrophy was observed. Spectroscopy revealed an increase in choline peak and reduction in aspartate, suggestive of an inflammatory lesion. Ketogenic diet was started, alongside 1,800 mg of felbamate bid, 1,600 mg of eslicarbazepine once a day, 100 mg of phenobarbital 100, and 0.25 mg of clonazepam bid. Plasmapheresis was also attempted with no improvement in clinical status. Ultimately, vertical right perisilvian hemispherotomy was performed and seizure freedom achieved. As expected, he developed left hemiparesis and is currently undergoing neurorehabilitation. Neuropathology of the resected hemisphere again showed neuronal loss, reactive gliosis and astrocytosis, and perivascular mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate and features of neuronophagia similar to the earlier resection.

Figure 1. MRI and CT Imaging.

Axial brain MRI T2-fluid attenuation inversion recovery (FLAIR) showing a right middle frontal gyrus infiltrative lesion (A), with corresponding T1 hypointensity, no enhancement after gadolinium (B), and no increase in relative cerebral blood volume on perfusion-weighted imaging (C) (presurgery). Follow-up axial brain MRI T2-FLAIR at 6 (D) and 22 (E) months postsurgery revealing increased frontal right hyperintensity and a mild symmetric bilateral hemispheric atrophy. Chest (F), abdomen (G), and pelvis (H) CT scan showing a large anterior mediastinal mass.

Discussion

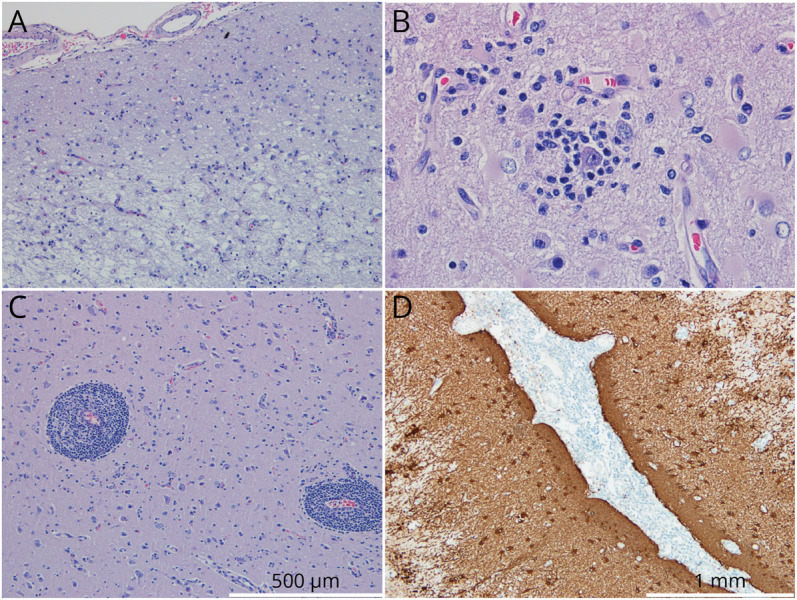

Anti-Hu typically presents in adults with small cell lung cancer, although cases of anti-Hu limbic encephalitis associated with nonseminomatous mediastinal germinoma have been reported up to 9 years before tumor detection.9 Anti-Hu antibodies in children are rare1-8 (Table 1). In addition, only a limited number of pediatric cases described in the literature report an association between anti-Hu encephalitis and an identified tumor, with most being neuroblastoma in children younger than 3 years.1,2,7

Table 1.

Review of the Literature

| Study | Sex, age | Presentation | Diagnostic workup | Tumor | Treatment | Outcome and follow-up |

| Langer et al., 20126 | 5-y-old, male | Episodic ataxia, behavioral changes, later temporal seizures | MRI: temporal T2 hypersignal, no atrophy CSF: no relevant changes EEG: bilateral temporal seizures Anti-Hu antibodies (+, serum) |

No tumor identified at 2 y of follow-up | Six different ASD and immunotherapy: steroids, low-dose prednisone, rituximab, IVIg, dexamethasone | Normalization of serum anti-Hu titers 1 y after treatment Oral steroids discontinued Improvement of seizures and behaviour 2 y later |

| Honnorat et al., 20132 | Case series | Eight children with limbic encephalitis | MRI abnormal in 4/6, with temporal T2/FLAIR hyperintensities CSF: unpaired positive oligoclonal bands in 4 patients Anti-Hu antibodies (+, serum) |

Neuroblastoma in 2; 6 did not have tumor at 50 mo | All 6 patients received ASD and immunotherapy | Epilepsy resistant to therapy in all of them; 5 developed cognitive impairment |

| Aravamuthan et al., 20155 | 5-y-old, female | Focal seizures of right face and arm; Right lower facial weakness, dysarthria, and cognitive decline | EEG: left hemispheric slowing and frontotemporal seizures MRI: left-greater-than-right hemispheric atrophy and T2 caudate hyperintensity Anti-Hu antibody (+, serum and CSF) |

No tumor identified | ASD: Levetiracetam and lacosamide Immunotherapy: pulses of methylprednisolone, cyclophosphamide and mycophenolate mofetil |

Improvement of seizure frequency, facial weakness, and cognitive skills |

| Capobianco et al., 20153 | 5-y-old, female | Nonconvulsive status epilepticus; left hemiparesis, choreoathetosis, dystonia and cognitive decline | MRI: T2-hyperintensity in left frontal lobe CSF oligoclonal bands Elevated serum ANA (>1/640) Anti-Hu antibodies (+, serum) |

No tumor identified | Immunotherapy: prednisone and rituximab | No recurrence of status epilepticus; sporadic focal motor seizures Slight improvement of paresis and choreoathetotic movements Stabilization of cognitive function |

| Sweeney et al., 20164 | 11-y-old, female | Opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome, ataxia, and focal jerks of the left face and arm | MRI: mesial temporal lobe and subinsular hyperintensities in T2 FLAIR EEG: epilepsia partialis continua CSF pleocytosis Anti-Hu antibodies (+, serum and CSF) |

Paraspinal ganglioneuroblastoma | ASD: oxcarbazepine, levetiracetam, phenytoin, clobazam Immunotherapy: oral prednisone, monthly IVIg, rituximab |

After 1 y, she continued with ongoing subtle opsoclonus, mild ataxia, dysarthric speech and frequent focal seizures of the left face and hand |

| Pranzatelli and McGee, 20177 | 16-mo-old female | Limbic encephalitis and left focal seizures with impairment of awareness | MRI: normal EEG: left temporal epileptic focus Anti-Hu antibodies (+, serum and CSF) Pathology: focal neuronal loss and gliosis, focal perivascular chronic inflammation and gliosis, and cortical temporal dysplasia |

Neuroblastoma | Multiple ASD Immunotherapy: IVIg, prednisone, high-dose corticotropin, cyclophosphamide, rituximab Surgery: left anterior temporal lobectomy |

Serum antibodies remained high for 10 mo before declining but persisted for years Clinical improvement after rituximab, without seizures off antiseizure drugs and immunotherapy, and returned to school |

| Frazzini et al., 20198 | 15-y-old female | Focal left motor seizures progressing to bilateral seizures; myoclonic jerks (EPC) | MRI: bilateral FLAIR hyperintense signals on the precentral gyri Anti-Hu antibodies (+, serum and CSF) EEG: interictal bilateral spike and waves, on the right frontal areas |

No tumor identified | Several ASDs Immunotherapy: steroids, IVIg, cyclophosphamide, rituximab, mycophenolate |

After 10 y of follow-up, she presented moderate reduction of myoclonus |

| Sabanathan et al., 20221 | Case series of pediatric autoimmune limbic encephalitis | Two children with limbic encephalitis; 1 had a peripheral axonal neuropathy since infancy | Anti-Hu antibodies (+, serum) | Neuroblastoma in 1; in the second patient, underlying malignancies were not identified | No data provided | The patient with neuroblastoma died |

Abbreviations: ASD = antiseizure drug; EPC = epilepsia partialis continua; FLAIR = fluid-attenuated inversion recovery; IVIg = IV immunoglobulin.

Cases of anti-Hu antibody disease in pediatric populations.

While it was unclear in our patient whether the mediastinal mass was related to the clinical picture, the fact that anti-Hu antibodies are directed at intranuclear antigens and pathogenically related to the presence of Hu-specific T cells, plus the initial response to immunotherapy and lesion resection, strongly advocate in favor of a paraneoplastic anti-Hu encephalitis related with the seminoma. Of interest, Rasmussen encephalitis (RE) is also a T-cell–mediated disease suggesting a shared pathophysiologic mechanism. Moreover, the neuropathologic findings in anti-Hu encephalitis are identical to those found in RE, which is a diagnosis of exclusion.10 However, the mild and nonprogressive cortical deficits before hemispherotomy, plus the absence of progressive unilateral cortical hemispheric atrophy, strongly disfavor RE in this case.10 Notwithstanding, unilateral signal abnormalities in the affected hemisphere have been described in a third of patients with EPC diagnosed with RE.11

To date, 2 cases of antibody-mediated inflammatory diseases mimicking RE have been described: 1 with anti-NMDA11 and the other with anti-Hu antibodies,5 although neither of them with associated malignancy, as in our case. Other differential diagnoses for inflammatory lesions presenting with EPC include mitochondrial disorders, although in these, EPC tends to present earlier, with distinguishing clinical features and bilateral EEG and imaging changes.11 Likewise, in children with anti-NMDA encephalitis, EPC presents with severe encephalopathy and complex movement disorders and therefore is unlikely to account for isolated EPC.11 Only a few cases of anti-Hu paraneoplastic syndrome and EPC are described, mainly in adults, and without hemispheric atrophy or other RE resembling features.4,12-14

Currently, little is known regarding the best therapeutic strategy for these challenging cases. While the goal is to achieve optimal seizure control, prevent further brain atrophy, and preserve intellectual and motor performance, this must be balanced with iatrogenic immunotherapy risks, a particularly sensitive question when dealing with children. In the advent of immunotherapy failure, surgery indication is considered. Because this is the first description of hemispherotomy in anti-Hu–associated encephalitis, long-term outcomes are unknown. Although this procedure alone may not be sufficient to achieve seizure freedom due to continuous antibody cytotoxicity,5 a probability higher than 70% of long-term seizure-freedom has been described for RE.15

This case broadens the spectrum of anti-Hu–associated neurologic disorders in children. We highlight the importance of considering antineuronal antibody testing in children presenting with EPC, focal cerebral atrophy, or hypersignal suggestive of RE and the need for an ongoing surveillance for malignancy in the presence of anti-Hu antibodies. Although previously reported pediatric cases may have involved undiscovered occult malignancies, this is the first description of a pathology-proven paraneoplastic autoimmune encephalitis associated with anti-Hu antibodies and EPC.

Research Ethics and Patient Consent

The study is exempt from ethics board review board approval. Written informed consent to disclose was obtained from the patient and his parents.

Data Availability

The authors have full access and the right to publish all data contained in this article, separate and apart from the guidance of any sponsor.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Professor Josef Dalmau at Hospital Clinic, University of Barcelona, for his insight and contribution for this case diagnosis and management; Dr Ricardo Rego at the Refractory Epilepsy Center and Neurophysiology Unit of Centro Hospitalar Universitário de São João (CHUSJ) and Dr. María Ángeles Pérez Jiménez at Hospital Infantil Universitario Niño Jesús in Madrid for multidisciplinary discussions and their contribution to this case management; Dr. Manuel Rito and Dr. Josué Pereira at Neurosurgery Department of CHUSJ; Dr. Jorge Pinheiro and Dr. Roberto Silva at Neuropathology Department of CHUSJ; and Dr. Cátia Morais at the Neuroimmunology Laboratory of Centro Hospitalar Universitário do Porto.

Appendix. Authors

| Name | Location | Contribution |

| Veronica Cabreira, MD | Neurology Department, Centro Hospitalar Universitário de São João; Neurosciences and Mental Health Department, Faculty of Medicine, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; study concept or design; and analysis or interpretation of data |

| Daniel Ferreira, MD | Neurology Department, Centro Hospitalar Universitário de São João; Neurosciences and Mental Health Department, Faculty of Medicine, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; study concept or design; and analysis or interpretation of data |

| Cláudia Melo, MD, PhD | Neuropediatrics Unit, Pediatrics Department, Centro Hospitalar Universitário de São João; Department of Pediatrics and Gynecology-Obstetrics, Faculty of Medicine, Universidade do Porto, Porto, Portugal | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content; study concept or design |

| Joana Rebelo, MD | Pediatric Oncology Department, Centro Hospitalar Universitário de São João, Porto, Portugal | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content |

| Jacinta Fonseca, MD | Neuropediatrics Unit, Pediatrics Department, Centro Hospitalar Universitário de São João; Department of Pediatrics and Gynecology-Obstetrics, Faculty of Medicine, Universidade do Porto, Porto, Portugal | Analysis or interpretation of data |

| Raquel Sousa, MD | Neuropediatrics Unit, Pediatrics Department, Centro Hospitalar Universitário de São João; Department of Pediatrics and Gynecology-Obstetrics, Faculty of Medicine, Universidade do Porto, Porto, Portugal | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content; analysis or interpretation of data |

| Mafalda Sampaio, MD | Neuropediatrics Unit, Pediatrics Department, Centro Hospitalar Universitário de São João; Department of Pediatrics and Gynecology-Obstetrics, Faculty of Medicine, Universidade do Porto, Porto, Portugal | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content; study concept or design; and analysis or interpretation of data |

Study Funding

No targeted funding reported.

Disclosure

The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Sabanathan S, Abdel-Mannan O, Mankad K, et al. Clinical features, investigations, and outcomes of pediatric limbic encephalitis: a multicenter study. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2022;9(1):67-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Honnorat J, Didelot A, Karantoni E, et al. Autoimmune limbic encephalopathy and anti-Hu antibodies in children without cancer. Neurology. 2013;80(24):2226-2232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Capobianco M, Sperli F, Malentacchi M, Valentino P, et al. Anti-Hu antibodies associated focal epileptogenic encephalitis successfully treated with rituximab: a new limited form of chronic focal encephalitis of the Rasmussen's type? Austin J Clin Neurol. 2015;2(5):1043. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sweeney M, Sweney M, Soldán MM, Clardy SL. Antineuronal nuclear autoantibody type 1/anti-Hu-associated opsoclonus myoclonus and epilepsia partialis continua: case report and literature review. Pediatr Neurol. 2016;65:86-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aravamuthan BR, Sánchez Fernández I, Zurawski J, Olson H, Gorman M, Takeoka M. Pediatric anti-Hu-associated encephalitis with clinical features of Rasmussen encephalitis. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2015;2(5):e150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Langer JE, Lopes MB, Fountain NB, et al. An unusual presentation of anti-Hu-associated paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2012;54(9):863-866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pranzatelli MR, McGee NR. Neuroimmunology of OMS and ANNA-1/anti-Hu paraneoplastic syndromes in a child with neuroblastoma. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2018;5(2):e433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frazzini V, Nguyen-Michel V, Habert MO, et al. Focal status epilepticus in anti-Hu encephalitis. Autoimmun Rev. 2019;18(11):102388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silsby M, Clarke CJ, Lee K, Sharpe D. Anti-Hu limbic encephalitis preceding the appearance of mediastinal germinoma by 9 years. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2020;7(3):e685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Varadkar S, Bien CG, Kruse CA, et al. Rasmussen's encephalitis: clinical features, pathobiology, and treatment advances. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(2):195-205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greiner H, Leach JL, Lee KH, Krueger DA. Anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis presenting with imaging findings and clinical features mimicking Rasmussen syndrome. Seizure. 2011;20(3):266-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shavit YB, Graus F, Probst A, Rene R, Steck AJ. Epilepsia partialis continua: a new manifestation of anti-Hu-associated paraneoplastic encephalomyelitis. Ann Neurol. 1999;45(2):255-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacobs DA, Fung KM, Cook NM, Schalepfer WW, Goldberg HI, Stecker MM. Complex partial status epilepticus associated with anti-Hu paraneoplastic syndrome. J Neurol Sci. 2003;213(1-2):77-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mut M, Schiff D, Dalmau J. Paraneoplastic recurrent multifocal encephalitis presenting with epilepsia partialis continua. J Neurooncol. 2005;72(1):63-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lagarde S, Boucraut J, Bartolomei F. Medical treatment of Rasmussen's Encephalitis: a systematic review. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2022;178(7):675-691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors have full access and the right to publish all data contained in this article, separate and apart from the guidance of any sponsor.