Abstract

Background

Healthcare-associated infections in long-term care are associated with substantial morbidity and mortality. While infection prevention and control (IPC) guidelines are well-defined in the acute care setting, evidence of effectiveness for long-term care facilities (LTCF) is missing. We therefore performed a systematic literature review to examine the effect of IPC measures in the long-term care setting.

Methods

We systematically searched PubMed and Cochrane libraries for articles evaluating the effect of IPC measures in the LTCF setting since 2017, as earlier reviews on this topic covered the timeframe up to this date. Cross-referenced studies from identified articles and from mentioned earlier reviews were also evaluated. We included randomized-controlled trials, quasi-experimental, observational studies, and outbreak reports. The included studies were analyzed regarding study design, type of intervention, description of intervention, outcomes and quality. We distinguished between non-outbreak and outbreak settings.

Results

We included 74 studies, 34 (46%) in the non-outbreak setting and 40 (54%) in the outbreak setting. The most commonly studied interventions in the non-outbreak setting included the effect of hand hygiene (N = 10), oral hygiene (N = 6), antimicrobial stewardship (N = 4), vaccination of residents (N = 3), education (N = 2) as well as IPC bundles (N = 7). All but one study assessing hand hygiene interventions reported a reduction of infection rates. Further successful interventions were oral hygiene (N = 6) and vaccination of residents (N = 3). In outbreak settings, studies mostly focused on the effects of IPC bundles (N = 24) or mass testing (N = 11). In most of the studies evaluating an IPC bundle, containment of the outbreak was reported. Overall, only four articles (5.4%) were rated as high quality.

Conclusion

In the non-outbreak setting in LTCF, especially hand hygiene and oral hygiene have a beneficial effect on infection rates. In contrast, IPC bundles, as well as mass testing seem to be promising in an outbreak setting.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13756-023-01318-9.

Keywords: Infection prevention, Long-term care facilities, Healthcare-associated infection, COVID-19

Background

In the United States, there are 65,600 regulated long-term care facilities (LTCF). Around 70% of people turning 65 are expected to need long-term care at some point in their life, and 18% of the older persons will spend over a year in a nursing facility [1]. Similar data exist for Europe, where approximately 3 million long-term care beds exist in nursing and residential care facilities in the 26 EU member states for which data are available in 2020 [2].

Healthcare-associated infections (HAI) are a major threat in acute and long-term care [3]. Point prevalence studies from Switzerland demonstrated that between 2.0 and 4.4% of nursing home residents are affected by HAI [4]. In combination, these numbers indicate that a large proportion of the population will sooner or later be affected by HAI in a long-term care institution and that there is an essential need for effective HAI preventive and control measures in these settings [3]. The Covid-19 pandemic underlined the strong need for recommendations to prevent HAI in long-term care [5].

While infection prevention and control (IPC) measures and outcomes are well defined for acute care hospitals in the World Health Organization (WHO) core components for infection prevention [6], data are scarce for long-term care settings.

In a thorough review by Lee et al., published 2019 prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, the authors were unable to identify a set of measures that could be proposed for implementation of effective IPC measures [7]. Up to this review, only a few high-quality studies were available [7].

In the current study, we aimed to both, update the findings by Lee et al. and complete by focusing on the Covid-19 pandemic in order to provide an overview of the current literature, identify existing research gaps and propose IPC measures and that could uniformly be recommended in long-term care. For the analysis, we differentiated between non-outbreak and outbreak settings.

Methods

The methods and results are reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement 2020 [8].

Definitions

PICOS statement

The population of interest was defined as residents and healthcare workers in adult LTCF. Interventions included any IPC measures in accordance with the WHO core components for infection prevention even if they were mainly developed for acute care settings [9]. Furthermore, we included oral hygiene as IPC measure as it has been shown to have a beneficial effect on infection rates in other settings [10]. No restrictions in terms of comparisons were made. Outcomes were defined as HAIs or HAI prevention measures, mortality or transmission events, as well as healthcare worker attributes such as IPC knowledge or adherence to measures.

Search strategy

In order to cover the most recent scientific evidence, with a specific focus on the Covid-19 pandemic, we performed an electronic search of PubMed and The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) using the terms (((infection[Title/Abstract] OR infections[Title/Abstract]) AND (‘nursing home*’[Title/Abstract] OR ‘skilled nursing*’[Title/Abstract] OR ‘long-term care’[Title/Abstract])) AND (practice[Title/Abstract] OR control*[Title/Abstract] OR measure*[Title/Abstract] OR evaluate*[Title/Abstract] OR effect*[Title/Abstract] OR prevent*[Title/Abstract] OR program*[Title/Abstract] OR intervention*[Title/Abstract] OR outcome*[Title/Abstract])) NOT (surgery[Title/Abstract] OR cancer[Title/Abstract] OR ‘neoplasm’[Title/Abstract] OR ‘intensive care unit’[Title/Abstract] OR child[Title/Abstract] OR children[Title/Abstract] OR ‘operative’[Title/Abstract]). Thereby, we built on the search strategy used in the most comprehensive existing review [7], but extended the time frame from 2017 until the 4th of November, 2022. In addition, reference lists of reviewed articles were scanned and the results combined.

Eligibility criteria

We included randomized controlled trials, observational studies (cohort and case–control studies) and quasi-experimental studies (before-after studies) in non-outbreak settings and outbreak reports. Studies were included if they were published in English and reported results from an infection prevention intervention in adult LTCFs.

Article types such as review papers, letters, editorials, expert opinions, ecological studies and study protocols were excluded, as were studies from pediatric long-term-care settings.

Study selection

Four main authors (NB, DF, SPK, and JM) screened searched titles and abstracts of each reference identified by the search. If the study met the eligibility criteria, the full-text article was reviewed independently for definitive inclusion by two authors each. In case of disagreement or in unclear cases, a third author made the decision about final inclusion.

Data extraction

Study data were extracted by the same authors (NB, DF, SPK, and JM), including setting, study design, main topic, type of intervention, and outcomes, using a standardized data collection form. An intervention was rated as successful when a statistically significant effect in the primary outcome was observed.

Included studies were further classified into non-outbreak versus outbreak settings.

Quality assessment

To assess methodological quality and risk of bias, we used the Cochrane risk-of-bias (RoB) 2.0 tool for randomized controlled trials, and the Newcastle Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale for Cohort studies and case–control studies [11, 12]. Each included study was assessed by one author and classified as high, medium, or low quality.

If the judgement in all key domains was ‘low risk of bias’ for RCT or achieved one star within every category for observational studies, the study was determined to be high quality. If the judgement in one or more key domains was ‘unclear’ or had ‘some risk of bias’ in the RoB 2.0 tool or achieved most but not all stars in the Newcastle–Ottawa-Scale, the study was evaluated to be medium quality. If the study was assessed to be at high risk of bias in one or more key domains for RCTs or failed to meet most of the stars for observational studies, the quality-summary was deemed to be low in quality. Single-arm trials and outbreak reports were classified as low quality.

In order to avoid duplication and for better readability, most results are either presented in the detailed tables or in the main text.

Detailed descriptions of the respective investigated infection control and prevention measures are given in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Included studies from the non-outbreak setting

| Author | Design | Setting | Sample size | Topic | Intervention | Study period | Outcome | Results | Mean quality score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chahine et al. (2022) [13] | Quasi-experimental | LTCF | 205 (2015/16) and 253 (218/19) hospital admissions | Antimicrobial Stewardship | AMS mandate consisting of leadership, accountability, drug expertise, acting, tracking, reporting and education | 2015/16 and 2018/19 | MDRO and CDI-Incidence | No statistically significant difference in the combined rate of LTCF-acquired MDRO-I/C and CDI | Medium |

| Felsen et al. (2020) [14] | Quasi-experimental | 6 NHs in the USA | Not described | Antimicrobial Stewardship | CDC's core elements for antibiotic stewardship in acute care | 2014–2019 | CDI incidence | Rate of CDI per 10.000 RD decreased | Low |

| Nace et al. (2020) [15] | RCT | 25 LTCFs in the USA |

Intervention: 512.408 facility resident-days Control: 443.912 facility resident-days |

Antimicrobial Stewardship | Multifaceted antimicrobial stewardship intervention, education, guidelines, audit, feedback | 02/2017–04/2018 | CDI incidence | Increase in CDI in control group | Medium |

| Salem-Schatz et al. (2020) [16] | Quasi-experimental | 30 LTCFs in the USA |

365.019 patient days in first period 340.468 resident days in second period |

Antimicrobial Stewardship | Education, tools |

1. period: 13/2012–06/2013 2. Period: 11/2013–06/2014 |

CDI incidence rate | Reduction of CDI | Low |

| Mody et al. (2003) [17] | RCT | 2 LTCFs in the USA | 127 persistent carriers | Decolonization | Mupirocin therapy or placebo administered twice daily for 14 days to nares and/or wound surfaces | Not reported | S.aureus colonization, reduction in S.aureus infections in residents treated with Mupirocin | Mupirocin significantly eradicated colonization in 93% of intervention group while 85% of placebo group remained colonized | Medium |

| Baldwin et al. (2010) [19] | cRCT | 32 NHs in Northern Ireland |

Intervention: 16 NHs Control: 16 NHs |

Education | Education: 2 h session at baseline, and at 3 and 6 months, Audits Control: usual practice | 01/2007–08/2008 |

MDRO incidence Infection control audit scores |

MRSA prevalence was not significantly different between intervention and control groups Infection control audit scores were significantly higher in intervention group compared with control group at 12 months |

Medium |

| Freeman-Jobson et al. (2016) [20] | Quasi-experimental | 3 LTCFs in the USA | 42 care workers | Education | Education program (three sections] | Not reported | Knowledge related to UTIs | Knowledge scores improved significantly | Low |

| Fendler et al. (2002) [21] | Quasi-experimental | 1 NH in the USA | 275 beds | Hand hygiene | Hand sanitizer provided to 2nd and 3rd floors of facility, remainder of facility served as control and received no hand sanitizer | Not reported | Nosocomial infection rates | Reduction in nosocomial infection rates seen in hand sanitizer group | Medium |

| Ho et al. (2012) [22] | cRCT | 18 LTCFs in Hong Kong |

Intervention 1: 6 LTCFs Intervention 2: 6 LTCFs Control: 6 LTCFs |

Hand hygiene |

WHO multi-modal HH interventions: ABHR, gloves, posters, reminders, video clips and performance feedback Intervention 1: slightly powdered gloves Intervention 2: powderless gloves Control: a 2 h health talk |

Not reported | HH adherence, infection rates, MDRO incidence |

HH adherence was increased after intervention in intervention groups Risks of respiratory outbreaks and MRSA infections requiring hospitalization were reduced in the intervention group |

Low |

| Lai et al. (2019) [23] | Cohort study | 11 NHs in Taiwan | 11 NHs | Hand hygiene | Education | 01/2015–12/2016 | Knowledge | Increase in hand hygiene compliance rate, overall knowledge level and use of alcohol-based hand rub | Low |

| Mody et al. (2003) [24] | Quasi-experimental | 2 NHs units in the USA | 2 NHs | Hand hygiene | Educational campaign to introduce alcohol based hand rubs | Not reported | Nosocomial infection rates | No difference in nosocomial infection rates after introduction of alcohol based hand rubs | Medium |

| Schweon et al. (2013) [25] | Quasi-experimental | 1 NH in the USA | 1 NH | Hand hygiene | HH programme, provision of HH product and wipes, HH education for HCW and patients, Poster as reminder, HH champion, HH compliance monitoring | 05/2009–02/2011 | Infection rates, MDRO incidence |

Significant reduction in LRTIs as well as a non-significant reduction in SSTIs Incidence rates of MRSA, VRE,CDI and gastrointestinal illness were not significantly reduced post-intervention |

Low |

| Teesing et al. (2021) [26] | cRCT | 66 units in 33 NHs in the Netherlands |

Intervention: 976 beds Control:886 beds |

Hand hygiene | Multimodal intervention including a combination of activities for changing hygiene policy and the individual behavior of nurses, E-learning, 3 live lessons, posters, and a photo competition, hand hygiene compliance measurements | 10/2016–10/2017 | Infection rates, MDRO incidence |

Significantly more gastroenteritis and significantly less influenza-like illness in the intervention arm No significant differences of pneumonia, urinary tract infections, and MRSA infections in the intervention arm compared to the control arm |

Medium |

| Temime et al. (2018) [27] | cRCT | 26 NHs in France |

Intervention: 13 NHs Control: 13 NHs |

Hand hygiene | Bundle of HH-related measures: increased availability of alcohol-based handrub, HH promotion, staff education, and local work groups | 04/2014–04/2015 |

Primary: infection rates Secondary: mortality |

No data for primary endpoint The intervention group showed significantly lower mortality |

Medium |

| Yeung et al. (2011) [28] | cRCT | 6 LTCFs in Hong Kong |

Intervention: 3 LTCFs (73 staff, 244 residents) Control: 3 LTCFs (115 staff, 379 residents) |

Hand hygiene |

Pocket-sized containers of ABHR, a 2-h seminar, reminder materials and posters Control: basic life support education and workshops and usual HH practices |

01/2007–11/2007 | HH adherence, infection rates | Increase in HH adherence and reduction of the incidence of infections | Low |

| Banks M et al. (2021) [29] | Quasi-experimental | 1 LTCF in the USA | 180 beds | Hand Hygiene | HH technology, badge measures alcohol concentration on health care workers hands, or time washing hands | 2017–2019 | HH adherence, CDI rates | Increase in compliance with hand hygiene, reduction of CDI rate | Low |

| Sassi et al. (2015) [30] | Quasi-experimental | 1 LTCF in the USA |

Fomites Before: 106 samples After: 105 samples Staff hands Before: 28 samples After: 29 samples |

Hand hygiene | Training: active ingredients, safety precautions, effective times, recommended times to use the product and recommended methods, Product placement: hand sanitizer, wipes, antiviral tissue and gloves | Not reported | MDRO incidence | There was a 16.7% reduction in the number of MS-2 positive, significant reduction in recovered MS-2 on sampled fomites and staff hands | Low |

| Peterson et al. (2016) [18] | cRCT | 12 nursing units at 3 LTCFs in the USA | Between 850—900 beds | IPC Bundle | Universal decolonization for MRSA, active surveillance (all admissions), annual instruction on HH, enhanced cleaning of surfaces (every 4 months) | 03/2011–03/2013 | MRSA incidence | Significant reduction in rate difference between intervention group and control group | Low |

| Bellini et al. (2015) [31] | cRCT | 104 NHs in Switzerland |

Intervention: 53 NHs (2338 residents) Control: 51 NHs (2412 residents) |

IPC Bundle |

Universal MRSA screening, topical decolonization of carriers, disinfection of environment, standard precautions and training sessions Control: standard precautions alone |

06/2010–12/2011 | MRSA incidence | No significant reduction in prevalence of MRSA carriers | High |

| Koo et al. (2016) [32] | cRCT | 12 NHs in the USA |

Intervention: 6 NHs Control: 6 NHs |

IPC Bundle |

Interactive educational program: Pre-emptive barrier precautions with gloves and gown, monthly MDRO and infection surveillance with feedback, NH staff education Control: own IPC practices and given knowledge tests |

Not reported | Knowledge about IPC topics | Knowledge scores increased significantly after each educational module | Medium |

| Mody et al. (2015) [33] | cRCT | 12 NHs in the USA |

Intervention: 6 NHs Control: 6 NHs |

IPC Bundle |

Pre-emptive barrier precaution, active surveillance for MDROs and infections with feedback, NH staff education on IPC practices and HH promotion Control: own IPC practices |

Not reported | MDRO incidence | Intervention group had a significant decrease in overall MDRO prevalence, and lower rates of MRSA acquisition and first new CAUTI | High |

| McConeghy et al. (2017) [34] | cRCT | 5 NHs in the USA | 481 and 380 long-stay residents | IPC Bundle | Education, cleaning products, and audit of compliance and feedback | 10/2015–05/2016 | Infection rates | No significant reduction for both total infections and LRTIs | Medium |

| Mody et al. (2021) [35] | cRCT | 6 NHs in the USA |

Intervention: 113 patients Control: 132 patients |

IPC Bundle | Enhanced barrier precautions, chlorhexidine bathing, MDRO surveillance, environmental cleaning, education and feedback, hand hygiene promotion | 09/2016–08/2018 | MDRO incidence | Reduced overall prevalence of MDRO | Medium |

| Ben-David et al. (2019) [36] | Quasi-experimental | 330 LTCFs in Israel | 330 LTCFs | IPC Bundle | Education, screening, isolation | 2009–2015 | MDRO incidence | Incidence of MDRO acquisition declined in all facility types to approximately 50% from baseline | Low |

| Trick et al. (2004) [37] | cRCT | 1 skilled NH in the USA | 283 residents | Isolation | Healthcare workers assigned to either the contact isolation group or routine glove use group without contact isolation | 06/1998–12/1999 | MDRO incidence | No difference in acquisition of VRE/MRSA with glove use without contact isolation compared to contact isolation group | High |

| Adachi et al. (2002) [38] | RCT | 2 NHs in Japan | 141 residents | Oral hygiene | Professional oral care weekly by dental hygienists in intervention group, usual care in control group | Not reported | Oral health | Professional oral care by dental hygienist reduced microorganisms related to pneumonia | Low |

| Ishikawa et al. (2008) [39] | Quasi-experimental | 3 NHs in Japan | 202 residents | Oral hygiene | Provided professional oral care by a dental hygienist once a week with varying modality, intensity and frequency | Not reported | Oral health | Levels of oropharyngeal bacteria decreased across all 3 facilities when weekly professional care was instituted | Low |

| Kulberg et al. (2010) [40] | Quasi-experimental | 1 NH in Sweden | 43 residents | Oral hygiene | Dental hygiene education led by dental hygienist for nursing staff; residents were given electronic toothbrushes,recommended to use chlorhexidine gel twice daily | 2008 | Oral health | Reduction in plaque scores | Low |

| Maeda and Akagi (2014) [41] | Cohort study | 1 LTCF in Japan |

Intervention: 31 residents Control: 32 residents |

Oral hygiene |

Oral care protocol (at least twice per day), tooth and tongue brushing using a toothbrush, and oral mucosa brushing using a sponge brush and a 0.2% chlorhexidine solution, moisturizing the inner mouth with glyceryl poly methacrylate gel, salivary gland massage Control: oral care not performed regularly |

07/2011–06/2013 | Pneumonia rates | Reduction in the incidence of pneumonia | Medium |

| Quagliarello et al. (2009) [42] | RCT | 1 LTCF in the USA | 52 residents (30 in oral hygiene intervention group, 20 in swallowing intervention group) | Oral hygiene |

Oral hygiene group assigned to manual oral brushing plus chlorhexidine mouth rinse at different frequencies daily, no control Swallowing group assigned to 90 degree feeding posture, swallowing techniques or manual brushing daily |

Not reported | Oral health | Significant reduction in plaque scores at end of oral care intervention | Medium |

| Yoneyama et al. (2002) [43] | RCT | 11 NHs in Taiwan | 417 residents | Oral hygiene | Enforced oral hygiene measures and oral cleaning by dental hygienists once a week, control group received usual care | 1996–1998 | Pneumonia rates | Incidence of pneumonia was lower in intervention group | Medium |

| Cabezas et al. (2021) [44] | Cohort study | NH in Spain | 28.000 residents, 26.000 NH Staff, 60.000 HCW | Vaccination | Participants (NH-Residents, NH-staff and HCW) were followed until outcome (SARS-Cov2 infection, hospital admission, death) occurs, vaccination as a time varying exposure | 12/2020–05/2021 | SARS-CoV-2 infection rates, hospital admission or death with Covid-19 | Vaccination was associated with 80–91% reductions in symptomatic and asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections among nursing home residents, nursing home staff, and healthcare workers and led to ≥ 95% reductions in covid-19 related hospital admission and mortality among nursing home residents | Low |

| Goldin et al. (2022) [45] | Cohort study | 454 LTCFs in Israel | 43.596 residents | Vaccination | BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 (Comirnaty) Vaccine | 12/2020–05/2021 | SARS-CoV-2 infection rates | Mortality from COVID-19 was 21.9% in the vaccinated population and 30.6% in the unvaccinated population | Medium |

| Maruyama et al. (2010) [46] | RCT | 9 hospitals and 23 NHs in Japan | 1006 residents | Vaccination | Residents received pneumococcal vaccine, control group received placebo | 03/2006–03/2009 | Pneumonia rates | Significant reduction of pneumonia incidence | High |

LTCF, long-term care facilities; MDRO, multi-drug resistant Organism; CDI, C.difficile Infection; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; RD, resident days; DOT, days of therapy; AIRR = ; UTI, urinary tract infection; RCT, randomized-control trial; cRCT, cluster randomized-control trial; NH, Nursing Home; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; WHO, World Health Organization; ABHR, alcohol-based hand rub; HH, hand hygiene; HCW, healthcare worker; LTRI, lower respiratory tract infection; SSTI, skin and soft tissue infection; VRE, Vancomycin-resistant Enterococci; IPC, infection prevention and control; CAUTI, Catheter-associated urinary tract infection; CRE, Carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae

Table 2.

Included studies from the outbreak setting

| Author | Design | Setting | Pathogen or disease | Sample size | Topic | N of cases | Overall attack rate | Outbreak Date | Control measures | Results | Mean quality score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahmed et al. (2018) [47] | Case–control study | 1 LTCF in the USA | GAS | 228-bed skilled nursing facility | IPC bundle | 7 residents and 5 staff |

0.84% resident: 0.65% Staff: 1.41% |

05/2014–08/2016 | Active surveillance, contact precaution, recommendation for use of PPE during irrigation, changing soiled diapers/linen before dressing change, and adopting a supportive sick leave policy | Frequent antimicrobial treatment and wound vacuum-assisted closure devices as risk factors | Medium |

| Al Hamad et al. (2021) [48] | Outbreak report | 1 LTCF in Qatar | Covid-19 | Not reported | IPC bundle | 24 cases | Not reported | 06/2020 | Education, awareness, staff compliance monitoring, contact tracing, visitor policy revision, monitoring | Lapse of infection control practices, successful containment of the outbreak, only 57% of patients were symptomatic | Low |

| Barret et al. (2014) [49] | Outbreak report | 1040 LTCFs in France | Gastroenteritis (Norovirus 73%, Rotavirus 19%) | Residents and staff | IPC bundle | 26.551 episodes among resident, 5.548 episodes among staff | resident: 32.5% Staff: 12.40% | 05/2010–05/2012 | Reinforcement of hand hygiene, contact precautions, cleaning or disinfection of the environment, restriction of movements, stopping or limitation of group activities, measures on food handling | The attack rate was lower and the duration of outbreaks was shorter when infection control measures were implemented within three days of onset of the first case | Low |

| Bernadou et al. (2021) [50] | Outbreak report | 1 NH France | Covid-19 | 88 residents, 104 staff | IPC bundle | 109 cases | 55% | 03–05/2020 | Mass testing, symptom screening, active surveillance, droplet measures | Significant rate of asymptomatic residents detected through mass screening | Low |

| Bruins et al. (2020) [51] | Outbreak report | 1 NH in the Netherlands | MDRO | 110 residents | IPC bundle | 8 cases | 7% | 02/2017–05/2018 | Screening, contact precautions, intensive cleaning procedure, education | Spread was associated with the use of shared toilets in communal areas. Containment of the outbreak after the implementation of a customized IPC bundle | Low |

| Calles et al. (2017) [52] | Case–control study | 1 LTCF in the USA | Hepatitis C | 114-bed skilled nursing facility | IPC bundle |

All cases: 45 residents, case–control: 30 cases/ 62 controls |

Overall: 10.54%, Residents:15.63% Staff: 0% | 01/2011–09/2013 | Screening, environmental measures, use of single-use of instruments, cleaning and disinfection, glove change, | Podiatry care and INR monitoring by phlebotomy were significantly associated with HCV cases | Medium |

| Dom´ınguez- Berjo´n et al. (2007) [53] | Cohort study | 1 NH in Spain | Adenovirus | 118 residents | IPC bundle | 46 cases (36 residents and 10 HCWs)/193 controls | Overall: 19.25%, Resident: 30.51% Staff: 8.26% | 08–12/2005 | Cleaning and disinfection, hand hygiene, isolation, withdrawal of affected workers, admission stop, visitor restrictions, education | Age, nursing home floor and cognitive impairment as independent risk factors | Medium |

| Dooling et al. (2013) [54] | Case–control study | 1 LTCF in the USA | GAS | Not reported | IPC bundle |

Total: 19 residents with 24 infections Case- control study: 18 infections/54 controls |

Not reported | 06/2009–06/2012 | Carriage survey, contact precaution, education, and placement of additional alcohol-based hand rub dispensers, cleaning and disinfection, chemoprophylaxis | Indwelling line and area of living as independent risk factors | Medium |

| Gaillat et al. (2008) [55] | Outbreak report | 1 NH in France | ILI (Influenza A) | 81 residents | IPC bundle | 32 residents and 6 staff |

Overall 29.46%, Residents: 39.51% Staff: 12.50% |

06–07/2005 | Isolation, wearing of surgical masks, droplet and contact precaution, chemoprophylaxis, setting up a crisis management team |

This outbreak occurred in summer Spread of the virus because of close area of living |

Low |

| Hand et al. (2018) [56] | Outbreak report | 1 LTCF in the USA | Coronavirus NL63 | 130 residents | IPC bundle | 20 cases | 26% | 11/2017 | Standard and droplet precaution, hand hygiene, enhanced environmental cleaning | Outbreak report with Coronavirus NL63 | Low |

| Kanayama et al. (2016) [57] | Case–control study | 1 LTCF in Japan | MRPA | Residents in a 225-bed LTCF | IPC bundle |

Total: 23 cases Case- control study: 14 cases/28 controls |

Not reported | 01/2013–01/2014 | Surveillance, infection control team composition, contact precautions, cohorting and using new gloves and gown, admission restriction, training and re-education of HCWs, deep environmental cleaning, discontinuation of sharing devices | Use of an oxygen mask and use of a nasogastric tube were significant factors associated with MRPA infection | Low |

| Mahmud et al. (2013) [58] | Multiple outbreak reports | 37 LTCFs in Canada | Influenza A (47%), Influenza B (5%), Parainfluenza (5%), Respiratory syncytial virus (3%), not identified (40%) | Residents and staff in 37 LTCFs | IPC bundle | 154 outbreaks | Median (Influenza A and B) residents: 7.2%, staff: 3.3% | Median: 18 days (3–53 days) | Chemoprophylaxis: 57% of influenza A, 63% of influenza B (the other measures were not reported), early notification | Early notification to public health authorities was associated with lower attack rate and mortality rates among residents, Chemoprophylaxis was the measure associated with lower attack rates, but not with shorter duration of outbreaks or with lower mortality | Low |

| McMichael et al. (2020) [59] | Outbreak report | 1 LTCF in the USA | COVID-19 | 130 residents and 170 staff | IPC bundle | 167 cases (101 residents, 50 HCW, 16 visitors) |

Residents: 77.6% HCW: 29.4% |

02–03/2020 | Case investigation, contact tracing, quarantine of exposed persons, isolation, on-site enhancement of IPC measures | Outbreak description of one of the first COVID-19 outbreaks in a LTCF | Low |

| Murti et al. (2021) [60] | Outbreak report | 1 NH in Canada | COVID-19 | 65 residents | IPC bundle | Residents: 61, Staff: 34 | Residents: Attack rate 94%, case fatality rate 45%; Staff: Attack rate 51% | 03–05/2020 | Droplet and contact precautions, universal masking of staff, testing, visitor restrictions | Tight clustering of cases with high attack rate of 94%, Outbreak containment after IPC implementation | Low |

| Nanduri et al. (2019) [61] | Outbreak report | 1 LTCF in the USA | GAS | Not reported | IPC bundle | 19 invasive and 60 non-invasive cases (50 residents and 24 staff) | Not reported | 05/2014–08/2016 | Chemoprophylaxis, active surveillance, recommendation of health authority | Inadequate infection control and wound-care practices may lead to this prolonged GAS outbreak in a skilled nursing facility | Low |

| Nicolay et al. (2018) [62] | Outbreak report | 1 NH in France | Acute gastroenteritis (Norovirus) | Nursing home with 89 residents | IPC bundle | 29 residents and 9 staff |

43.94% Resident: 57.65% Staff: 19.15% |

09–10/2016 | Reinforcement of standard precaution, barrier measures, limitation of the movements of symptomatic residents, environmental disinfection, stopping group activities, closure of the kitchen and outsourcing of meals | More dependent residents were at higher risk of acute gastroenteritis | Low |

| Psevdos et al. (2021) [63] | Outbreak report | 1 NH in the USA | COVID-19 | 80 residents | IPC bundle | 25 residents | Attack rate 31%, mortality rate 24% | 03–04/2020 | Testing, visitor restrictions, symptom screening, admission stop, hand hygiene, masks, isolation, | Attack rate only 31%. Quick containment of the outbreak through IP measures | Low |

| Sáez-López et al. (2019) [64] | Outbreak report | 1 LTCF in Portugal | Norovirus | 335 residents | IPC bundle | 146 people, 97 residents and 49 staff | Residents: 29%, Nurses: 19% | 10–12/2017 | Disinfection, hand hygiene, education, PPE, isolation and cohorting | Insufficient adherence to IPC measures due to staffing shortage | Low |

| Shrader et al. (2021) [65] | Outbreak report | 1 LTCF in USA | COVID-19 | 98 residents, 156 staff | IPC bundle | 52 residents and 19 staff | Resident 52% | 03–08/2020 | Testing, PPE, disinfection and isolation, restriction of visitors | Outbreak controlled with IPC measures | Low |

| Telford et al. (2021) [66] | Observational study | 24 LTCF in the USA | COVID-19 | 2580 LTCF residents | IPC bundle | 1004 | 39% | 06–07/2020 | Adherence to IPC (HH, Disinfection, Social Distancing, PPE, Symptom screening) | Implementation lowest in Disinfection, highest in symptoms screening, differences in social distancing and PPE between high-prevalence and low-prevalence group | Medium |

| Thigpen et al. (2007) [67] | Outbreak report | 1 NH in the USA | GAS | Residents in a 146-bed nursing home | IPC bundle |

Definite case: 6 residents Possible case: 4 residents |

6.9% | 11–12/2003 | Screening, reinforce standard precautions, improve access to hand disinfectants, to implement appropriate respiratory etiquette, influenza immunization, Chemoprophylaxis for colonized persons | Three risk factors for GAS: presence of congestive heart failure or history of myocardial infarction, residence on unit 2, and requiring a bed bath | Low |

| Van Dort et al. (2007) [68] | Case–control study | 1 NH in the USA | NTHi | 120-bed nursing home | IPC bundle |

13 cases 18 controls |

Not reported | 06–07/2005 | Universal precaution, respiratory droplet precaution, evaluating staffs with symptoms, throat culture survey for residents | None of the variables showed a significant association with NTHi | Medium |

| Van Esch et al. (2015) [69] | Case control study, Outbreak report | 1 LTCF in Belgium | CDI | 120 bed LTCF | IPC bundle |

66 cases 61 controls |

51.97% | 01/2009–12/2012 | Stringent hygienic protocol, active surveillance, strict isolation, timely treatment for CDI (AB-prescription), cleaning and disinfection of residents rooms | The nutritional status was found to be significantly poorer in the residents with CDI | Low |

| Weterings et al. (2015) [70] | Outbreak report | 1 hospital and 1 NH in the Netherlands | KPC-KP | 150-bed nursing home | IPC bundle | 4 cases | Not reported | 07–12/2013 | Isolation, PPE, Handrub with 70% alcohol, frequent audits of hand hygiene and direct feedback, daily cleaning of room and disinfection, contact screening surveillance | Preventing transmission of MDROs is challenging in nursing homes | Low |

| Kennelly et al. (2021) [71] | Observational study | 45 NH in Ireland | COVID-19 | 2043 residents | Surveillance | 1741 cases | 43.9%, 27.2% asymptomatic, fatality rate 27.6% | 04–05/2020 | Surveillance | Significant impact of Covid-19 with high rate of asymptomatic carriers | Low |

| Blackman et al. (2020) [72] | Outbreak report | 1 NH in the USA | COVID-19 | 150 bed institution | Testing | 32 symptomatic residents, 26 HCW, limited testing capacity | Not reported | Not reported | Education, personal protective equipment, masks, symptom screening, contact and droplet precautions | Severe outbreak despite IPC measures because of insufficient testing availability | Low |

| Dora et al. (2020) [73] | Outbreak report | 1 NH in the USA | COVID-19 | 99 residents | Testing | Residents:19 Staff: 8 | Residents: 19%; Staff 6% | 03–04/2020 | Screening, droplet and contact precautions, visitor restrictions | Successful outbreak containment | Low |

| Eckardt et al. (2020) [74] | Outbreak report | 1 LTCF in the USA | COVID-19 | 120 bed LTCF | Testing | Not reported | 5.4%, 3.6% and 0.41% in three point prevalence testing rounds every 14 days | Not reported | Point prevalence testing | Containment of outbreak | Low |

| Graham et al. (2020) [75] | Outbreak report | 4 NH in the UK | COVID-19 | 394 residents and 70 staff | Testing |

Residents: 126 Staff: 3 |

40% with 43% asymptomatic, 26% mortality | 03–05/2020 | Two point prevalence surveys | 60% of SARS-CoV-2 positive residents were either asymptomatic or only had atypical symptoms for Covid-19 | Low |

| Louie et al. (2021) [76] | Outbreak report | 4 LTCF in the USA | COVID-19 | 431 persons | Testing | 214 | 49.7%; thereof 40.2% asymptomatic | 03–04/2020 | Surveillance | Mass testing identified a high proportion of asymptomatic infections | Low |

| Patel et al. (2020) [77] | Cohort study | 1 LTCF in the USA | COVID-19 | 127 residents | Testing |

33 thereof 13 asymptomatic |

26% | Not reported | Surveillance | High rate of asymptomatic infections | Medium |

| Roxby et al. (2020) [78] | Outbreak report | 1 LTCF in the USA | COVID-19 | 80 residents and 62 HCW | Testing |

3 residents, 2 staff |

3.8% of residents, 3.2% of staff | Not reported | Mass testing, symptom screening | Detection of asymptomatic infected residents | Low |

| Sacco et al. (2020) [79] | Outbreak report | 1 LTCF in France | COVID-19 | 87 residents and 92 staff members | Testing | 41 residents and 22 staff members | 47% in residents and 24% in staff | 03–04/2020 | Mass testing | High rate of asymptomatic infected persons | Low |

| Sanchez et al. (2020) [80] | Outbreak report | 26 LTCF in the USA | COVID-19 | 2773 residents | Testing | 1207 cases | 44% | 03–05/2020 | Mass testing (two point-prevalence surveys) | 44% attack rate, 37% hospitalization, 24% mortality; Reduction of positivity after second point prevalence survey | Low |

| Zollner et al. (2021) [81] | Outbreak report | 3 LTCF in Austria | COVID-19 | 277 residents | Testing | 36 | 13% | 03–04/2020 | Testing | Only 25% with fever and 19% with cough, 6/36 remained asymptomatic, hospitalization rate 58% and mortality rate 33%,19/214 HCW positive | Low |

| Giddings et al. (2021) [82] | Cohort study | 330 LTCF in UK | COVID-19 | Resident and staffs | Vaccination | 297 outbreaks across all four time periods | 90% of LTCF | Not reported | Vaccination | Reduction of number of the proportion of LTCF with outbreaks over the four time periods from 51.5% to 4.7% | Medium |

| Martinot et al. (2021) [83] | Outbreak report | 1 LTCF in France | COVID-19 | 93 residents | Vaccination | 40 cases (residents 24, HCW 16) | Residents 25.8%, HCW 21.9% | 03–05/2021 | Vaccination | Outbreak with alpha-variant,higher case rate in unvaccinated than in vaccinated residents, no severe symptoms in vaccinated residents | Low |

| Mazagatos et al. (2021) [84] | Outbreak report | LTCFs in Spain | COVID-19 | Not reported | Vaccination | Not reported | Not reported | 12/2020–04/2021 | Vaccination | Effectiveness of 71%, 88% and 97% for infections, hospitalization and death | Low |

| Van Ewijk et al. (2022) [85] | Outbreak report | 1 LTCF in the Netherlands | COVID-19 | 105 residents | Vaccination | 70 residents | 67% (70/105) | 11/2021–01/2022 | Booster vaccine dose | Booster vaccine curbed transmission | Low |

| Cheng H-Y et al. (2018) [86] | Outbreak report | LTCFs in Taiwan | Influenza | 102 Outbreaks | Vaccination, antiviral treatment/prophylaxis | Median residents 65.5 | Median attack rate 24% | 2008–2014 | Antiviral prophylaxis | Initiating antiviral treatment within 2 days of outbreak start decreased the possibility of a large influenza outbreak to only one-third | Low |

LTCF, Long-term care facilities; GAS, Group A Streptococcus; IPC, Infection prevention and control; NH, Nursing Home; MDRO, multi-drug resistant Organism; INR, International Normalized Ratio; HCV, HepatitisCVirus; OR, Odds ratio; CI, Confidence interval; ILI, Influenza-like-illness; HCW, Healthcare worker; aOR, adjusted Odds ratio; RR, Risk ratio; HH, Hand hygiene; PPE, Personal Protective Equipment; NTHi, Non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae; CDI, C.difficile Infection; AB, Antibiotic; KPC-KP, Carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae

Results

Study characteristics

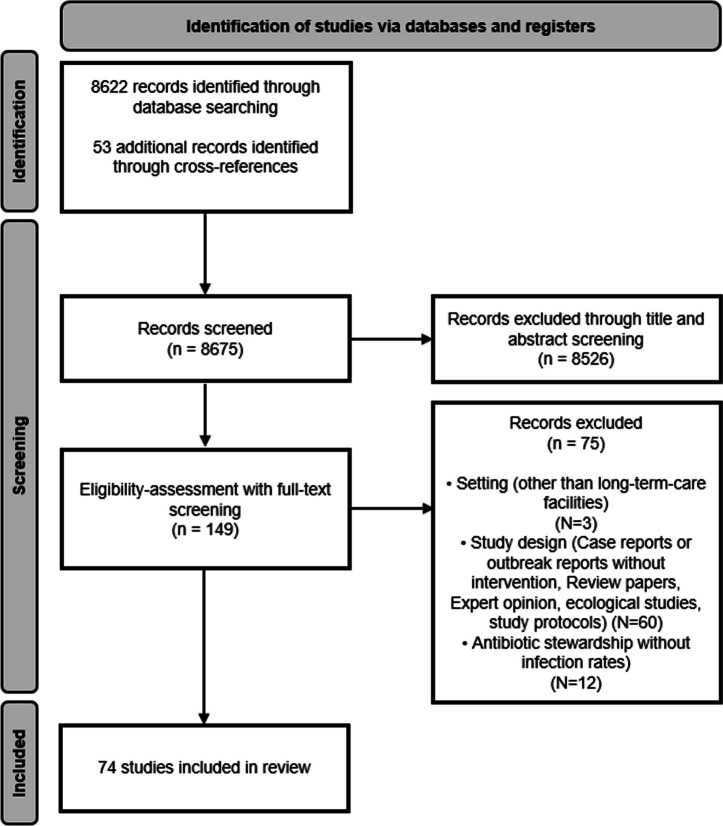

The literature search yielded 8675 references (Fig. 1). After the screening of titles and abstracts, we selected 150 studies for full-text screening. Seventy-four studies met the inclusion criteria and were included [13–86] (Tables 1, 2).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram 2020. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA statement [8]

Details for study type, study quality, place of study, and type of intervention are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the included studies with respect of study quality,-type,-place and type of intervention

| Variable | Total (%) | Non-outbreak (%) | Outbreak (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Studies | 74 (100) | 34 (46) | 40 (54) |

| Study quality | |||

| High quality | 4 (5) | 4 (100) | 0 |

| Medium quality | 22 (29) | 14 (64) | 8 (36) |

| Low quality | 48 (65) | 16 (33) | 32(67) |

| Study type | |||

| RCT | 18 (24) | 18 (100) | 0 |

| Cohort study | 10 (13) | 7 (70) | 3 (30) |

| Case control study | 6 (8) | 0 | 6 (100) |

| Outbreak report | 30 (41) | 0 | 30 (100) |

| Others (single arm trial, before-after study) | 10 (13) | 9 (90) | 1 (10) |

| Place of study | |||

| Europe | 23 (31) | 6 (26) | 17 (74) |

| North America | 38 (51) | 18 (47) | 20 (53) |

| Asia | 13 (18) | 10 (77) | 3 (23) |

| Type of intervention | |||

| IPC bundle | 31 (42) | 7 (23) | 24 (77) |

| Mass testing | 11 (15) | 0 | 11 (100) |

| Hand hygiene | 10 (14) | 10 (100) | 0 |

| Education | 2 (3) | 2 (100) | 0 |

| Isolation precautions | 1 (1) | 1 (100) | 0 |

| Oral hygiene | 6 (8) | 6 (100) | 0 |

| Vaccination | 7 (9) | 3 (43) | 4 (57) |

| Decolonization | 1 (1) | 1 (100) | 0 |

| Antimicrobial stewardship | 4 (5) | 4 (100) | 0 |

| Antiviral prophylaxis | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (100) |

| Measured outcomes | |||

| Infection rates | 33 (45) | 14 (42) | 19 (58) |

| MDRO incidence | 12 (16) | 11 (92) | 1 (8) |

| Oral health | 4 (5) | 4 (100) | 0 |

| Adherence to IPC measures | 3 (4) | 3 (100) | 0 |

| Knowledge about IPC topics | 2 (3) | 2 (100) | 0 |

| Outbreak control | 8 (11) | 0 | 8 (100) |

| Risk factor identification | 12 (16) | 0 | 12 (100) |

RCT, randomized controlled trial; IPC, infection prevention and control; MDRO, multi drugresistant organism

Type of intervention and setting

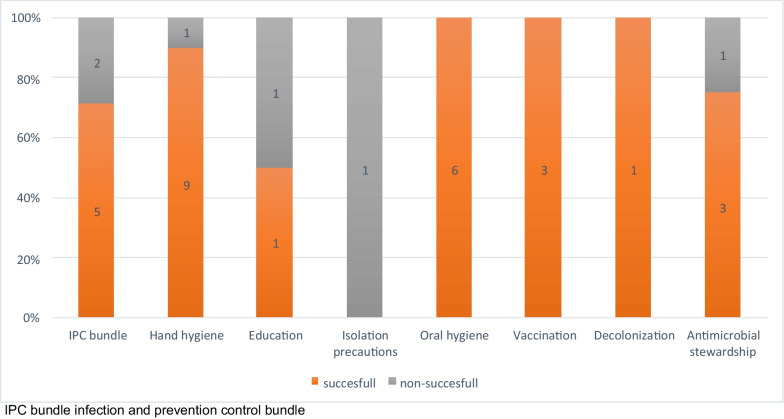

The most frequent interventions from the non-outbreak setting were hand hygiene (N = 10) [21–30], an IPC bundle with several measures included (N = 7) [18, 31–36], oral hygiene (N = 6) [38–43], antimicrobial stewardship (N = 4) [13–16] as well as vaccination of residents (N = 3) [44–46]. Interestingly, studies from Asia mainly concentrated on oral health (N = 4) [38, 39, 41, 43] and hand hygiene (N = 3) [22, 23, 28], whereas studies from North America drew their attention towards antimicrobial stewardship [13–16] and hand hygiene [21, 24, 25, 30] (each N = 4). An overview on the results of the included studies in non-outbreak settings is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Non-outbreak setting, divided in successful and non-successful intervention by type of intervention

The majority of studies in the outbreak setting concentrated on an IPC bundle (N = 24) [47–70] and on mass testing/surveillance (N = 11) [71–81].

Hand hygiene

Hand hygiene alone was evaluated in ten studies [21–30], all conducted in non-outbreak settings. Nine of ten articles showed a successful intervention with reduced infection rates and lower prevalence of multi drug resistant organisms (MDRO) [21–23, 25–30].

No study evaluated hand hygiene alone in an outbreak setting.

Antimicrobial stewardship

Four studies in non-outbreak-settings on antimicrobial stewardship which also measured the infection rates were included in our review [13–16]. Three could demonstrate a reduction of C.difficile infections through antimicrobial stewardship [14–16], while one retrospective quasi-experimental study showed no decrease of MDRO-incidence or C.difficile infections [13].

In an outbreak setting no studies on this topic were undertaken so far.

Education

Two studies assessed the effect of education in IPC measures [19, 20]. Both were executed in a non-outbreak setting. One RCT found no difference of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) prevalence in groups with IPC education [19]. The other study recorded a successful outcome with a significant improvement of knowledge after education [20].

No studies were conducted to evaluate the effect of education alone in an outbreak setting.

Decolonization

One RCT assessed decolonization measures as main intervention in a non-outbreak setting [17] and found a reduction of MRSA prevalence after decolonization measures were implemented. No study evaluated decolonization measures in an outbreak setting.

Isolation precautions

One high-quality study from the USA evaluated the effect of isolation precautions alone with no significant difference in MDRO prevalence with/without isolation precautions [37].

Vaccination

We included three studies on vaccination in a non-outbreak setting [44–46]. A high-quality trial from Japan showed a significant reduction in cases of pneumonia in residents of 23 LTCF after the 23-valent pneumococcal vaccine was introduced [46]. Two studies were conducted in the non-outbreak setting with COVID-19 vaccination and showed a significant reduction in COVID-19 cases, COVID-19 related hospitalization and mortality [44, 45]. In outbreak settings, COVID-19 vaccination of residents significantly reduced outbreaks, COVID-19 cases, COVID-19 related hospitalization, and mortality in 3 of 4 studies. One study, executed in the turn of the year 2021 to 2022 showed no reduction in COVID-19 cases, but a reduced case fatality after vaccination [85].

Oral hygiene

Six studies evaluated the effect of improved oral hygiene on overall infection rates, all from a non-outbreak setting [38–43]. All studies found a reduction of infections (mainly cases of pneumonia) with the intervention.

No publication on the effect of oral hygiene in an outbreak setting was recorded.

Mass testing

We found no study on mass testing in a non-outbreak setting. All studies that analyzed the effect of mass testing were performed in an outbreak setting during an early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic [72–81] and mostly resulted in the isolation of residents and quarantine of HCWs who tested positive. All of them found a significant number of asymptomatic HCWs and residents with a range of asymptomatic carriers from around 3% up to 43% in different studies.

IPC bundles

Half of the included studies (21% in non-outbreak-setting [18, 31–36] and 60% in outbreak setting [47–70]) focused on several topics simultaneously within an IPC bundle. In the non-outbreak setting one cRCT study evaluated a bundle of education of health care workers (HCW), surface cleaning, and feedback on HAI rates and could not observe a significant reduction in infection rates [34].

Furthermore, a large RCT in 104 long-term care facilities in Switzerland showed no effect of MRSA decolonization and different isolation precautions (standard vs. contact precautions) on MRSA prevalence [31].

In contrast, four studies could demonstrate a reduction of MDRO prevalence through a multicomponent intervention that included barrier precautions, active surveillance of MDRO and infections, as well as staff education and hand hygiene promotion [18, 33, 35, 36]. Koo et al. could at least show an improvement in knowledge for trained topics through an IPC bundle that included education while not evaluating infection rates [32]. Twenty-four of 31 included studies on IPC bundles were performed in an outbreak setting [47–70]. The included studies contained cohort and case–control studies, as well as outbreak reports. A median of 5 measures were included in an IPC bundle (range 2 to 8) with isolation/precautions (N = 24, 19.7%), surveillance (N = 13, 10.7%) and hand hygiene (N = 9, 8.2%) being the most represented interventions included in the bundles. All outbreak reports showed containment of the outbreaks.

When we differentiated by the transmission route, we found 15 studies where the transmission occurred mainly by respiratory droplets (SARS-CoV-2, Group A streptococci, Influenza-like illnesses) [47, 48, 50, 54–56, 58–61, 63, 65–68] and 8 studies with transmission via direct and/or indirect contact (gastroenteritis, MDRO, Norovirus etc.) [49, 51, 53, 57, 62, 64, 69, 70]. The bundles in these two categories varied slightly. The ones for pathogens transmitted through the respiratory route concentrated on wearing masks and repetitive testing, whereas those for direct or indirect contact transmissions focused more on environmental cleaning measures and contact precautions.

COVID-19

In the non-outbreak setting we found two articles focusing on the effect of vaccination on SARS-CoV-2 infection rates [44, 45]. Both found a positive effect of the vaccination on infection incidence in nursing home residents and staff as well as a reduced mortality in residents.

In 22/40 (55%) studies from the outbreak setting, SARS-CoV-2 was the main pathogen [48, 50, 59, 60, 63, 65, 66, 71–85]. Vaccination was also highly effective in reducing infections in this setting [82–85]. 7 articles reported the effect of an IPC bundle [48, 50, 59, 60, 63, 65, 66], whereas mass testing was the main IPC measure in 11 articles [71–81] (see also paragraph on mass testing above) and vaccination was evaluated in four studies [82–85]. As already mentioned above, most of the included studies from the outbreak setting documented a successful containment of the outbreak. This was also true for COVID-19.

Other WHO core components

Other WHO core components for infection prevention, such as IPC programs per se, IPC guidelines, monitoring of IPC practices, reduction of workload, optimized staffing and bed occupancy rates as well as the environment, materials and equipment alone were not evaluated in the studies that were identified by our search.

Study quality

The quality of included studies was generally low (Additional file 1: Tables S2a, S2b, S2c). Only four (5%) studies were classified as high quality [31, 33, 37, 46]; all of these were RCTs. Other RCTs were medium (N = 10) [15, 17, 19, 26, 27, 32, 34, 35, 42, 43] or low (N = 4) in quality [18, 22, 28, 38]. In contrast, the included cohort studies were medium-quality [21, 24, 41, 53, 82] or low-quality studies (N = 5) [29, 36, 39, 44, 77]. The case–control studies were classified as medium (N = 4) [47, 52, 54, 68] or low quality (N = 2) [57, 69]. All outbreak reports were classified as low quality per definition (N = 16) [48–51, 55, 56, 58–65, 67, 70].

Discussion

Main results

In this systematic review, which also covers the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, we identified 74 studies of different quality evaluating the effect of infection prevention and control measures in long-term care facilities in outbreak or non-outbreak settings, respectively. Hand hygiene, staff education measures, antimicrobial stewardship, vaccination and oral care seem to be consistently effective in preventing healthcare-associated infections or transmission events in long-term care settings. However, studies were mostly of low quality and highly heterogeneous with regard to setting, intervention measures, populations, and outcomes. Therefore, deriving standard of care recommendations or guidelines for LTCFs based on these data remains difficult.

Our current systematic review covers data from non-outbreak and outbreak settings, especially during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, from a variety of countries worldwide. With a large increase in new publications during the COVID-19 pandemic, our study provides an update on the currently available literature on the effectiveness of different infection prevention measures in LTCFs in comparison to previous reviews. This allowed us to draw a more accurate picture of the current evidence on this topic.

For non-outbreak publications, our results regarding the effectiveness of different measures as well as the difficult comparability of the studies are in line with earlier well-made systematic reviews [7, 87]. In comparison to Lee et al., we identified relatively good quality data on the importance of hand hygiene, antimicrobial stewardship, vaccination and oral hygiene in addition to the already known beneficial effects of education, monitoring and multi-modal strategies. Of note, Lee et al. did not evaluate any antimicrobial stewardship interventions in their review [7]. While Uchida et al. focused solely on therapeutic measures [87] we also analyzed studies on educational measures and focused more on the effect of the type of intervention. This allowed us to identify the particular contribution of various measures to a given outcome.

In contrast to others authors [7, 87–90], we included articles from the non-outbreak setting as well as from the outbreak-setting. While one review on IPC measures in the outbreak setting was conducted before COVID-19 [90], the others were published during the pandemic [88, 89].

For the outbreak setting, mainly for studies on SARS-CoV-2, our review indicates that reasonably good data exist for the effectiveness of vaccination, mass testing, and IPC bundles, whereas no statement can be made about other single or combination of measures [71, 72]. Since outbreaks in general and virus-related outbreaks in particular are often self-limiting [91], it remains difficult to assess and put into context the added value of such transiently applied outbreak control measures. Whether an outbreak could be contained because of the IPC bundle or because of the temporary nature of outbreaks is impossible to discriminate in studies without control group.

It is to be expected that a combination of different measures produces an additive or synergistic effect, although, in our review, combinations of different measures were mostly applied in outbreak settings, with a difficult to evaluate outcome for the reasons mentioned above. Therefore, an additive or synergistic effect cannot be proven in our dataset.

Although education is often part of a bundle of measures, there is very little data on the importance of education alone. However, this should not limit the importance of education, which is extremely important in this context where health care workers are often insufficiently trained in medical and infection prevention and control.

Strengths and limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, generalizability is hampered in that we only included studies published in English and most studies in our review were performed in North America and Europe. As long-term settings vary widely within and across countries, settings and thus effectiveness of interventions may differ across institutions. Second, publication bias may have played a role in that ineffective IPC interventions may not be published, especially in outbreak settings. Furthermore, due to the heterogeneity and the low quality of studies, we were unable to compare effect sizes, let alone to meta-analyze effects across studies, even within similar settings or types of interventions. Last, we did not extend our search beyond PubMed and The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), but given the quality and heterogeneity of identified studies, we are confident that searching further databases would not have led to more refined results. Another limitation of our study is the fact that LTC institutions provide medical and nursing care for different and rather heterogeneous resident populations in different countries. Thus, an identical measure could have a different clinical outcome based on the cognitive and or functional status of the persons living in the LTCF. This also applies to common geriatric syndromes such as frailty and/or malnutrition including urinary or stool incontinence. In addition the way how and by whom medical care is provided may have some impact upon the outcomes documented in our selected studies.

Strengths of our study are the inclusion of studies conducted in both non-outbreak and outbreak settings, including the COVID-19 pandemic and outbreaks of other pathogens, the inclusion of antimicrobial stewardship as a topic and the updated search until November 2022. Through this, we were able to recognize a large amount of studies with IPC measures not included in other reviews.

Conclusion and outlook

In conclusion, although we were able to find a good amount of data on IPC measures in the LTCF setting, interpretability and generalizability of these data remains difficult. Especially for outbreak settings, reports of successful control measures often do not add more value than do single case reports in the individual patient care setting. Given that the population at risk for healthcare-associated infections in these settings is large and constantly growing, coordinated action is imperative. In order to move a step forward and to complete the picture, well executed studies on this topic are desperately needed. These include a systematic evaluation of clearly defined single interventions or intervention bundles using high-quality (cluster-)-randomized controlled trials in well-defined settings and patient populations with useful outcome measures. These, due to the special needs of this population, do not only include HAIs, but also other measures such as quality of life, which sometimes might be favored over restrictive measures for infection prevention. In addition, IPC intervention trials and or measures across a clearly defined resident population and interventions that control for geriatric syndromes are urgently needed. Such efforts are only possible if sufficient funding for large, concerted, multi-national initiatives is available.

In general, it can be discussed whether reducing nosocomial infections is of high priority for the long-term-care setting or whether the focus should rather be on maintaining quality of life. Data on the influence of IPC measures on quality of life in long-term-care facilities are scarce or non-existing. From the COVID-19 pandemic, we assume that certain factors, such as visitor restriction, isolation measures and wearing masks for example, had an impact on the well-being of APH residents.

In the meantime, using the available low-quality evidence and extrapolating infection prevention and control measures from acute to long-term care with some common sense seem to be useful approaches. Thereby, the most essential basic IPC measures from the acute care setting, such as standard hygiene measures with hand hygiene and personal protective equipment when needed, combined with a good education for HCW and a functioning surveillance system might be the cornerstones of a successful IPC program in long-term care. Given that LTCFs are very heterogeneous with ever changing activities, defining the needs of every single institution is challenging. However, a standardized IPC program that every institution could adapt to its temporary needs may be a reasonable approach with a high acceptance on the part of the residents, HCW, and IPC team.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Quality assessment of the included studies

Author contributions

NB, JM, SPK and DF were involved in the conception and design of the work. NB, JM, SPK and DF were involved in study selection and data extraction. NB and JM made equal contributions as first author and drafted the original version of the manuscript. SPK and DF made equal contributions as last authors. CG, PK, JK, TM and MS read, critically appraised and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

PK was supported by the Swiss National Sciences Foundation (Grant Number PZ00P3_179919).

Availability of data and materials

The dataset used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Nando Bloch and Jasmin Männer: equal contribution as first authors.

Stefan P. Kuster and Domenica Flury: equal contribution as last authors.

References

- 1.https://www.crossrivertherapy.com/long-term-care-statistics.

- 2.https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statisticsexplained/index.php?title=Healthcare_resource_statistics_-_beds&oldid=567775#:~:text=In%202020%2C%20there%20were%20approximately,Germany%2C%20Greece%20and%20Cyprus.

- 3.Cassini A, Plachouras D, Eckmanns T, Abu Sin M, Blank HP, Ducomble T, et al. Burden of six healthcare-associated infections on European population health: estimating incidence-based disability-adjusted life years through a population prevalence-based modelling study. Harbarth S, editor. PLOS Med. 2016;13(10):e1002150. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Héquet D, Kessler S, Rettenmund G, Lemmenmeier E, Qalla-Widmer L, Gardiol C, et al. Healthcare-associated infections and antibiotic use in long-term care residents from two geographical regions in Switzerland. J Hosp Infect. 2021;117:172–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2021.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/covid-19-surveillance-in-long-term-care-facilities-november-2021.pdf.

- 6.Storr J, Twyman A, Zingg W, Damani N, Kilpatrick C, Reilly J, et al. Core components for effective infection prevention and control programmes: new WHO evidence-based recommendations. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2017;6:6. doi: 10.1186/s13756-016-0149-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee MH, Lee GA, Lee SH, Park YH. Effectiveness and core components of infection prevention and control programmes in long-term care facilities: a systematic review. J Hosp Infect. 2019;102(4):377–393. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2019.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLoS Med. 2021;18(3):e1003583. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. Improving infection prevention and control at the health facility: interim practical manual supporting implementation of the WHO guidelines on core components of infection prevention and control programmes. World Health Organization; 2018. Report No.: WHO/HIS/SDS/2018.10. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/279788. Cited 4 Jan 2023.

- 10.Wolfensberger A, Clack L, von Felten S, Faes Hesse M, Saleschus D, Meier MT, et al. Prevention of non-ventilator-associated hospital-acquired pneumonia in Switzerland: a type 2 hybrid effectiveness-implementation trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2023;23(7):836–846. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00812-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Risk of bias tools - Current version of RoB 2. https://sites.google.com/site/riskofbiastool/welcome/rob-2-0-tool/current-version-of-rob-2. Cited 28 Dec 2022.

- 12.Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Cited 4 Jan 2023.

- 13.Chahine EB, Cook RO, Carrion T, Sarkissian RJ. Impact of the antimicrobial Stewardship mandate on multidrug-resistant organisms and Clostridioides difficile infection among long-term care facility residents. Sr Care Pharm. 2022;37(8):345–356. doi: 10.4140/TCP.n.2022.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Felsen CB, Dodds Ashley ES, Barney GR, Nelson DL, Nicholas JA, Yang H, et al. Reducing fluoroquinolone use and clostridioides difficile infections in community nursing homes through hospital-nursing home collaboration. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21(1):55–61.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nace DA, Hanlon JT, Crnich CJ, Drinka PJ, Schweon SJ, Anderson G, et al. A multifaceted antimicrobial stewardship program for the treatment of uncomplicated cystitis in nursing home residents. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(7):944–951. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salem-Schatz S, Griswold P, Kandel R, Benjamin-Bothwell S, DeMaria AJ, McElroy N, et al. A statewide program to improve management of suspected urinary tract infection in long-term care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(1):62–69. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mody L, Kauffman CA, McNeil SA, Galecki AT, Bradley SF. Mupirocin-based decolonization of Staphylococcus aureus carriers in residents of 2 long-term care facilities: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2003;37(11):1467–1474. doi: 10.1086/379325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peterson LR, Boehm S, Beaumont JL, Patel PA, Schora DM, Peterson KE, et al. Reduction of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection in long-term care is possible while maintaining patient socialization: a prospective randomized clinical trial. Am J Infect Control. 2016;44(12):1622–1627. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2016.04.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baldwin NS, Gilpin DF, Tunney MM, Kearney MP, Crymble L, Cardwell C, et al. Cluster randomised controlled trial of an infection control education and training intervention programme focusing on meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in nursing homes for older people. J Hosp Infect. 2010;76(1):36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freeman-Jobson JH, Rogers JL, Ward-Smith P. Effect of an education presentation on the knowledge and awareness of urinary tract infection among non-licensed and licensed health care workers in long-term care facilities. Urol Nurs. 2016;36(2):67–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fendler EJ, Ali Y, Hammond BS, Lyons MK, Kelley MB, Vowell NA. The impact of alcohol hand sanitizer use on infection rates in an extended care facility. Am J Infect Control. 2002;30(4):226–233. doi: 10.1067/mic.2002.120129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ho M, Seto W, Wong L, Wong T. Effectiveness of multifaceted hand hygiene interventions in long-term care facilities in Hong Kong: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33(8):761–767. doi: 10.1086/666740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lai CC, Lu MC, Tang HJ, Chen YH, Wu YH, Chiang HT, et al. Implementation of a national quality improvement program to enhance hand hygiene in nursing homes in Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect Wei Mian Yu Gan Ran Za Zhi. 2019;52(2):345–351. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2018.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mody L, McNeil SA, Sun R, Bradley SE, Kauffman CA. Introduction of a waterless alcohol-based hand rub in a long-term-care facility. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2003;24(3):165–171. doi: 10.1086/502185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schweon SJ, Edmonds SL, Kirk J, Rowland DY, Acosta C. Effectiveness of a comprehensive hand hygiene program for reduction of infection rates in a long-term care facility. Am J Infect Control. 2013;41(1):39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Teesing GR, Richardus JH, Nieboer D, Petrignani M, Erasmus V, Verduijn-Leenman A, et al. The effect of a hand hygiene intervention on infections in residents of nursing homes: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2021;10(1):80. doi: 10.1186/s13756-021-00946-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Temime L, Cohen N, Ait-Bouziad K, Denormandie P, Dab W, Hocine MN. Impact of a multicomponent hand hygiene-related intervention on the infectious risk in nursing homes: a cluster randomized trial. Am J Infect Control. 2018;46(2):173–179. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2017.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yeung WK, Tam WSW, Wong TW. Clustered randomized controlled trial of a hand hygiene intervention involving pocket-sized containers of alcohol-based hand rub for the control of infections in long-term care facilities. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011;32(1):67–76. doi: 10.1086/657636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Banks M, Phillips AB. Evaluating the effect of automated hand hygiene technology on compliance and C. difficile rates in a long-term acute care hospital. Am J Infect Control. 2021;49(6):727–732. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2020.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sassi HP, Sifuentes LY, Koenig DW, Nichols E, Clark-Greuel J, Wong LF, et al. Control of the spread of viruses in a long-term care facility using hygiene protocols. Am J Infect Control. 2015;43(7):702–706. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2015.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bellini C, Petignat C, Masserey E, Büla C, Burnand B, Rousson V, et al. Universal screening and decolonization for control of MRSA in nursing homes: a cluster randomized controlled study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2015;36(4):401–408. doi: 10.1017/ice.2014.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koo E, McNamara S, Lansing B, Olmsted RN, Rye RA, Fitzgerald T, et al. Making infection prevention education interactive can enhance knowledge and improve outcomes: results from the Targeted Infection Prevention (TIP) Study. Am J Infect Control. 2016;44(11):1241–1246. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2016.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mody L, Krein SL, Saint SK, Min LC, Montoya A, Lansing B, et al. A targeted infection prevention intervention in nursing home residents with indwelling devices: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(5):714. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McConeghy KW, Baier R, McGrath KP, Baer CJ, Mor V. Implementing a pilot trial of an infection control program in nursing homes: results of a matched cluster randomized trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18(8):707–712. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mody L, Gontjes KJ, Cassone M, Gibson KE, Lansing BJ, Mantey J, et al. Effectiveness of a multicomponent intervention to reduce multidrug-resistant organisms in nursing homes: a cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(7):e2116555. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.16555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ben-David D, Masarwa S, Fallach N, Temkin E, Solter E, Carmeli Y, et al. Success of a national intervention in controlling carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae in israel’s long-term care facilities. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2019;68(6):964–971. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trick WE, Weinstein RA, DeMarais PL, Tomaska W, Nathan C, McAllister SK, et al. Comparison of routine glove use and contact-isolation precautions to prevent transmission of multidrug-resistant bacteria in a long-term care facility. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(12):2003–2009. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Adachi M, Ishihara K, Abe S, Okuda K, Ishikawa T. Effect of professional oral health care on the elderly living in nursing homes. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;94(2):191–195. doi: 10.1067/moe.2002.123493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ishikawa A, Yoneyama T, Hirota K, Miyake Y, Miyatake K. Professional oral health care reduces the number of oropharyngeal bacteria. J Dent Res. 2008;87(6):594–598. doi: 10.1177/154405910808700602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kullberg E, Sjögren P, Forsell M, Hoogstraate J, Herbst B, Johansson O. Dental hygiene education for nursing staff in a nursing home for older people. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66(6):1273–1279. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maeda K, Akagi J. Oral care may reduce pneumonia in the tube-fed elderly: a preliminary study. Dysphagia. 2014;29(5):616–621. doi: 10.1007/s00455-014-9553-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Quagliarello V, Juthani-Mehta M, Ginter S, Towle V, Allore H, Tinetti M. Pilot testing of intervention protocols to prevent pneumonia in nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(7):1226–1231. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02311.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yoneyama T, Yoshida M, Ohrui T, Mukaiyama H, Okamoto H, Hoshiba K, et al. Oral care reduces pneumonia in older patients in nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(3):430–433. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cabezas C, Coma E, Mora-Fernandez N, Li X, Martinez-Marcos M, Fina F, et al. Associations of BNT162b2 vaccination with SARS-CoV-2 infection and hospital admission and death with covid-19 in nursing homes and healthcare workers in Catalonia: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2021;18(374):n1868. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goldin S, Adler L, Azuri J, Mendel L, Haviv S, Maimon N. BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 (Comirnaty) vaccine effectiveness in elderly patients who live in long-term care facilities: a nationwide cohort. Gerontology. 2022;8:1–8. doi: 10.1159/000521899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maruyama T, Taguchi O, Niederman MS, Morser J, Kobayashi H, Kobayashi T, et al. Efficacy of 23-valent pneumococcal vaccine in preventing pneumonia and improving survival in nursing home residents: double blind, randomised and placebo controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;8(340):c1004. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ahmed SS, Diebold KE, Brandvold JM, Ewaidah SS, Black S, Ogundimu A, et al. The role of wound care in 2 group a Streptococcal outbreaks in a Chicago skilled nursing facility, 2015–2016. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2018;5(7):ofy145. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofy145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Al Hamad H, Malkawi MMM, Al Ajmi JAAA, Al-Mutawa MNJH, Doiphode SH, Sathian B. Investigation of a COVID-19 outbreak and its successful containment in a long term care facility in Qatar. Front Public Health. 2021;9:779410. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.779410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barret AS, Jourdan-da Silva N, Ambert-Balay K, Delmas G, Bone A, Thiolet JM, et al. Surveillance for outbreaks of gastroenteritis in elderly long-term care facilities in France, November 2010 to May 2012. Euro Surveill Bull Eur Sur Mal Transm Eur Commun Dis Bull. 2014;19(29):20859. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2014.19.29.20859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bernadou A, Bouges S, Catroux M, Rigaux JC, Laland C, Levêque N, et al. High impact of COVID-19 outbreak in a nursing home in the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, France, March to April 2020. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21(1):198. doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-05890-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bruins MJ, Koning Ter Heege AH, van den Bos-Kromhout MI, Bettenbroek R, van der Lubben M, Debast SB. VIM-carbapenemase-producing Escherichia coli in a residential care home in The Netherlands. J Hosp Infect. 2020;104(1):20–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2019.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Calles DL, Collier MG, Khudyakov Y, Mixson-Hayden T, VanderBusch L, Weninger S, et al. Hepatitis C virus transmission in a skilled nursing facility, North Dakota, 2013. Am J Infect Control. 2017;45(2):126–132. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2016.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Domínguez-Berjón MF, Hernando-Briongos P, Miguel-Arroyo PJ, Echevarría JE, Casas I. Adenovirus transmission in a nursing home: analysis of an epidemic outbreak of keratoconjunctivitis. Gerontology. 2007;53(5):250–254. doi: 10.1159/000101692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dooling KL, Crist MB, Nguyen DB, Bass J, Lorentzson L, Toews KA, et al. Investigation of a prolonged Group A Streptococcal outbreak among residents of a skilled nursing facility, Georgia, 2009–2012. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2013;57(11):1562–1567. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gaillat J, Dennetière G, Raffin-Bru E, Valette M, Blanc MC. Summer influenza outbreak in a home for the elderly: application of preventive measures. J Hosp Infect. 2008;70(3):272–277. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hand J, Rose EB, Salinas A, Lu X, Sakthivel SK, Schneider E, et al. Severe respiratory illness outbreak associated with human coronavirus NL63 in a long-term care facility. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24(10):1964–1966. doi: 10.3201/eid2410.180862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kanayama A, Kawahara R, Yamagishi T, Goto K, Kobaru Y, Takano M, et al. Successful control of an outbreak of GES-5 extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a long-term care facility in Japan. J Hosp Infect. 2016;93(1):35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2015.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mahmud SM, Thompson LH, Nowicki DL, Plourde PJ. Outbreaks of influenza-like illness in long-term care facilities in Winnipeg, Canada. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2013;7(6):1055–1061. doi: 10.1111/irv.12052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McMichael TM, Clark S, Pogosjans S, Kay M, Lewis J, Baer A, et al. COVID-19 in a long-term care facility—King County, Washington, February 27–March 9, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(12):339–342. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6912e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Murti M, Goetz M, Saunders A, Sunil V, Guthrie JL, Eshaghi A, et al. Investigation of a severe SARS-CoV-2 outbreak in a long-term care home early in the pandemic. CMAJ Can Med Assoc J J Assoc Med Can. 2021;193(19):E681–E688. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.202485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nanduri SA, Metcalf BJ, Arwady MA, Edens C, Lavin MA, Morgan J, et al. Prolonged and large outbreak of invasive group A Streptococcus disease within a nursing home: repeated intrafacility transmission of a single strain. Clin Microbiol Infect Off Publ Eur Soc Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;25(2):248.e1–248.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2018.04.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nicolay N, Boulet L, Le Bourhis-Zaimi M, Badjadj-Kab L, Henry L, Erouart S, et al. The role of dependency in a norovirus outbreak in a nursing home. Eur Geriatr Med. 2018;9(6):837–844. doi: 10.1007/s41999-018-0120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]