Abstract

Background

In European axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) and psoriatic arthritis (PsA) clinical registries, we aimed to investigate commonalities and differences in (1) set-up, clinical data collection; (2) data availability and completeness; and (3) wording, recall period, and scale used for selected patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs).

Methods

Data was obtained as part of the EuroSpA Research Collaboration Network and consisted of (1) an online survey and follow-up interview, (2) upload of real-world data, and (3) selected PROMs included in the online survey.

Results

Fifteen registries participated, contributing 33,948 patients (axSpA: 21,330 (63%), PsA: 12,618 (37%)). The reported coverage of eligible patients ranged from 0.5 to 100%. Information on age, sex, biological/targeted synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug treatment, disease duration, and C-reactive protein was available in all registries with data completeness between 85% and 100%. All PROMs (Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity and Functional Indices, Health Assessment Questionnaire, and patient global, pain and fatigue assessments) were more complete after 2015 (68–86%) compared to prior (50–79%). Patient global, pain and fatigue assessments showed heterogeneity between registries in terms of wording, recall periods, and scale.

Conclusion

Important heterogeneity in registry design and data collection across fifteen European axSpA and PsA registries was observed. Several core measures were widely available, and an increase in data completeness of PROMs in recent years was identified. This study might serve as a basis for examining how differences in data collection across registries may impact the results of collaborative research in the future.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13075-023-03184-7.

Keywords: Spondyloarthritis, European registries, Clinical data collection, Collaborative research, Real-world evidence

Background

Clinical registries and observational cohorts are essential for studying disease course, treatment effect, and safety in real-world patients. To study rare exposures and outcomes, very large study populations are required, such as through collaborative research across countries. Many countries have established clinical rheumatology registries [1–13]; however, differences in their design, data availability, and completeness pose a challenge when researchers pool data from multiple countries [14, 15].

In rheumatoid arthritis (RA), two surveys conducted among 25 European clinical cohorts and registries, and 14 biological disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (bDMARD) registries under the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR), suggested that existing heterogeneity in the data collection represents a limitation for data merging and collaborative research. As an example, the registries used diverse methods and instruments for measuring patient-reported outcomes, hampering direct comparability and interpretation [16–19].

The EuroSpA Research Collaboration Network (RCN) is a scientific collaboration among European clinical registries, collecting information on patients with spondyloarthritis (SpA), including axial SpA (axSpA) and psoriatic arthritis (PsA). The individual registries collect a broad range of clinical data relevant for the everyday management of patients with SpA (www.eurospa.eu). However, specific knowledge about the commonalities and differences in data collection across the 16 participating registries is limited. The experience from RA clinical registries [16, 17] prompted the need for a similar cross-country exploration of data collection practices in SpA to gain a better understanding of the data used in pooled analyses. Ultimately, such knowledge may guide the design and interpretation of future collaborative studies. Furthermore, as recently suggested in the European Medicines Agency Patients Registries Initiative [20], it would be beneficial for collaborative research if a set of commonly collected variables with high data availability were defined.

The objective of this study was therefore to explore the design of European registries collecting information on axSpA and PsA, including the commonalities and differences in (1) the set-up, clinical data collection, and funding; (2) data availability and completeness; and (3) the wording, recall period, and scale of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs).

Methods

The study consisted of three parts: (1) an online survey designed to capture aspects of registry set-up and clinical data collection, (2) data availability and completeness analysis performed on real-world data collected through EuroSpA, and (3) investigation of the wording, recall period and scale used for selected patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs).

Online survey regarding registry design

The survey data were collected and managed using the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) tool, a secure, web-based software platform designed to support data capture for research studies [21, 22]. The survey covered the following 12 themes: general registry information (e.g., set-up, infrastructure for data-collection, funding), data management, demographics, diagnosis, disease characteristics, medication, safety, PROMs, lifestyle, laboratory measures, imaging, and comorbidities. The number of individual questions covered in each theme varied from 9 (safety) to 56 (general registry information), the full survey is included as Supplementary material. Each registry assigned 1–3 persons with a thorough knowledge of the registry, hereafter called “registry experts,” to complete the survey. Two investigators (LL, LØ) then reviewed the responses for inconsistencies and missingness. Next, a one-hour semi-structured interview was conducted through a video link by the same two investigators to supplement and validate the survey responses. A common interview guide was shared with the registry experts ahead of the interview (see Supplementary material).

Patient data availability and completeness assessment of uploaded datasets

Considering the themes explored in the online survey, data availability across registries and data completeness across variables were investigated. A variable was considered available if collected in the registry; the data completeness was reported for each available variable. We used patient data that had been prospectively collected in the registries and uploaded onto a secure server by the individual registries for secondary use in the EuroSpA collaboration. Data were pseudonymized, i.e., personal identifiers had been removed and replaced with placeholder values prior to upload. Previous EuroSpA studies have been based on data uploaded in a similar manner [23, 24]. For the current study, we included data on patients with a clinical diagnosis of axSpA or PsA, aged 18 years or older, and followed in one of the participating registries from the start of their first course of biological (b) DMARD or targeted synthetic (ts) DMARD therapy between 2000 to 2021. Data from the baseline visit of the first b/tsDMARD treatment course were used for this study. A baseline visit was defined as a visit from 4 weeks before to 4 weeks after the treatment initiation date, with priority given to the closest visit before treatment start. Baseline visit data included age, time since diagnosis, clinical disease characteristics, medication, PROMs, and inflammatory markers. Other variables, e.g., HLA-B27, lifestyle, comorbidities, and classification criteria were considered patient-specific and were included independently of the baseline visit, if available in the registry. The availability of variables not accessible for evaluation in the uploaded data was instead based on the survey responses provided by the registry experts.

Wording, recall period, and scale used for selected patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs)

In the online survey, the registry experts reported the specific wording (translated into English when necessary), recall period, and scales (NRS or VAS) used in the patient global, pain and fatigue assessments. Further details were explored during the follow-up interview, and furthermore, the reported scale was verified by visual inspection of the distribution of the patient scores in the uploaded data.

Results

Registries from 15 countries participated: ATTRA (Czech Republic), DANBIO (Denmark), ERSBTR (Estonia), ROB-FIN (Finland), ICEBIO (Iceland), GISEA (Italy), AmSpA (Netherlands), NOR-DMARD (Norway), Reuma.pt (Portugal), RRBR (Romania), biorx.si (Slovenia), BIOBADASER (Spain), SRQ (Sweden), SCQM (Switzerland), and BSRBR-AS (UK). BSRBR-AS and AmSpA collected data on axSpA only. Data availability and completeness were assessed in a total of 33,948 patients (axSpA: 21,330, PsA: 12,618).

Online survey regarding registry design

In Table 1, an overview of the 15 registries, based on the online survey and follow-up interviews, is presented. The full survey is included as Supplementary material. A diagnosis was registered using the International Classification of Diseases – tenth revision (ICD-10) in 5 registries, classification criteria in 2 registries, and expert opinion in 1 registry. In the remaining 7 registries all three methods could be applied (Table 1). Treatment with b/tsDMARDs was registered by all, while treatments with conventional synthetic (cs) DMARDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and glucocorticoids were registered in 14, 8, and 11 registries, respectively (Table 1). The estimated coverage of eligible patients ranged from 0.5% (Netherlands) to 100% (Romania) for both diagnoses (Table 1). The sources of funding for the registry activities differed, 7/14 from research grants (covering 2–80% of expenses/cost), 4/14 from the public sector (covering 10–100%), 12/14 from industry (20–100%) and other sources in 3/14 registries (10–100%) (Table 1). The funding was further explored during the follow-up interviews and covered expenditures related to the development and running of IT platforms, dedicated research nurses, secretaries, data managers, and statisticians.

Table 1.

Set-up of 15 registries in EuroSpA

| Country | Czechia | Denmark | Estonia | Finland | Iceland | Italy | Netherlands | Norway | Portugal | Romania | Slovenia | Spain | Sweden | Switzerland | UK |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Registry | ATTRA | DANBIO | ESRBTR | ROB-FIN | ICEBIO | GISEA | AmSpA | NOR-DMARD | Reuma.pt | RRBR | Biorx.si | BIOBADASER | SRQ | SCQM | BSRBR-AS |

| General information | |||||||||||||||

| Patients included in the registry | |||||||||||||||

| AxSpA/PsA patients in the data completeness analyses (n)a | 3512/1331 | 4855/3652 | <100/<100 | 1699/720 | 386/424 | 171/457 | <100/- | 1805/1052 | 1985/1094 | 1325/242 | 616/448 | 1126/1036 | 791/1084b | 1893/1021 | 1091/- |

| AxSpA, year of start | 2002 | 2002 | 2013 | 2000 | 2008 | 2010 | 2019 | 2000 | 2009 | 2013 | 2010 | 2000 | 1999 | 2005 | 2012 |

| PsA, year of start | 2002 | 2002 | 2013 | 2000 | 2008 | 2010 | - | 2000 | 2009 | 2013 | 2010 | 2000 | 1999 | 2006 | - |

| Other rheumatological conditions | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Additional entry criteria | |||||||||||||||

| Treatment with a b/ts DMARD | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||

| Basis for diagnosis registration | |||||||||||||||

| ICD-10 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||

| Expert opinion | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||

| ASAS/mNY criteria | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| CASPAR criteria | √ | √ | √ | - | √ | √ | √ | √ | - | ||||||

| Number of visits per year | |||||||||||||||

| First year | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2-3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Subsequent years | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Data entry | |||||||||||||||

| Electronic | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Paper-based | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||

| Interactive fields | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| Medication | |||||||||||||||

| b/tsDMARDs | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| csDMARDs | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| NSAIDs | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||

| Oral glucocorticoids | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| Coverage | |||||||||||||||

| Geographic area covered by the registry | |||||||||||||||

| Nationwide | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| Estimate of eligible patients included | |||||||||||||||

| axSpA | 95 | 95 | 95 | 60 | 95 | 15 | 0.5 | 25 | 10 | 100 | 70 | 5 | 82 | 10 | 0.5 |

| PsA | 95 | 85 | 95 | 60 | 95 | 10 | - | 25 | 15 | 100 | 60 | 4 | 76 | 10 | - |

| Institutions collecting patient data | |||||||||||||||

| Private rheumatology practices | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||

| University hospital rheumatology departments | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Other hospital rheumatology departments | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Funding of registry activities (%) | |||||||||||||||

| Research grants | 5 | 80 | 20 | 15 | 50 | 20 | 2 | ||||||||

| Public sector | 15 | 100 | 10 | 50 | |||||||||||

| Industry | 95 | 85 | 100 | 20 | 80 | 85 | 50 | 80 | 90 | 50 | 90 | 98 | |||

| Other | 100c | 100d | 10 | ||||||||||||

axSpA Axial spondyloarthritis, PsA Psoriatic arthritis, DMARD Disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs, ICD-10 International Classification of Diseases – tenth revision, ASAS Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society, mNY Modified New York, CASPAR Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis, NSAID Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, NA Not available

aSecondary pseudonymized baseline data from initiation of the first biologic (b) or targeted synthetic (ts) disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug (DMARD) treatment on patients with a clinical diagnosis of axSpA and PsA, 18 years or older, followed in one of the participating registries since the start of their first b/tsDMARD between 2000 to 2021

bSweden has provided data on Secukinumab treated patients only

cNational society for rheumatology is sponsor

dGeneral research funds

Patient data availability and completeness assessment of uploaded datasets

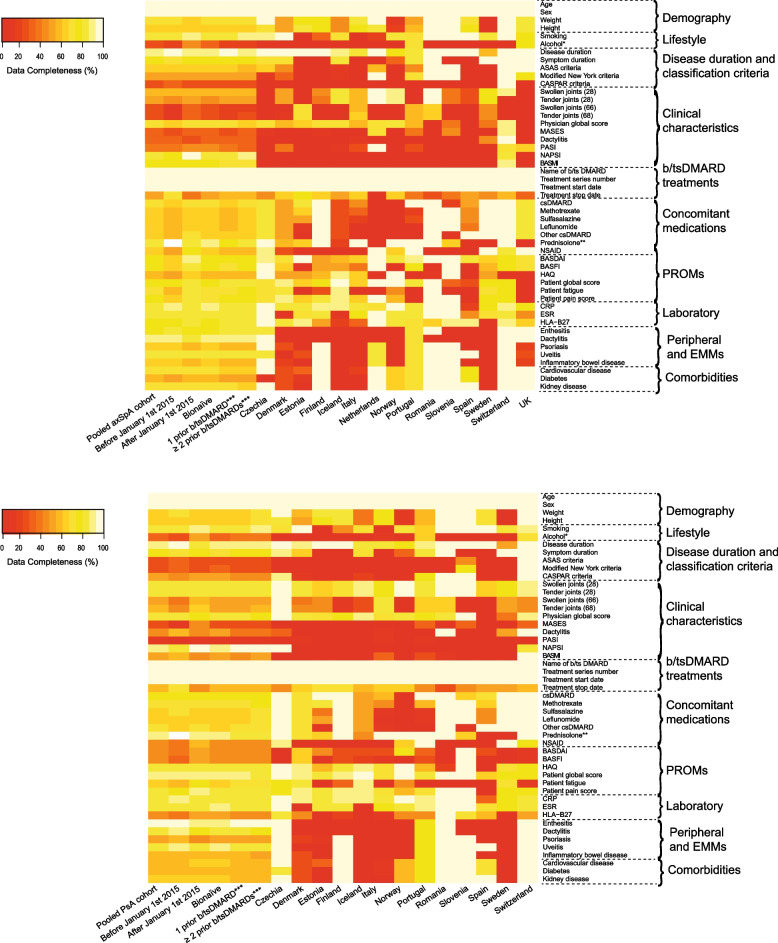

In Table 2, data availability and completeness are presented in pooled and stratified data (treatment courses initiated before vs. after January 1, 2015, and axSpA vs PsA), and in Fig. 1 data are further stratified by b/tsDMARD history and registry. Age, sex, disease duration, C-reactive protein (CRP), and details regarding b/tsDMARDs were available in all 15 registries with a data completeness ranging from 85 to 100% (Table 2). Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) scores were also available in all registries; while data completeness varied by the time period (later time period: 71% vs earlier: 54%) and diagnosis (axSpA: 78% vs PsA: 39%) (Table 2). The data completeness in variables describing peripheral involvement, such as swollen/tender joint counts and the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ), were higher in PsA (50–85%) vs. axSpA (16–58%). Conversely, variables designed to evaluate axial involvement, such as the BASDAI, the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional and Metrology Indices (BASFI and BASMI), had higher data completeness in axSpA (39–78%) vs PsA (7–39%) (Table 2). All PROMs had higher data completeness in the later time period (68–86%) compared to before 2015 (50–79%) (Table 2). Variables describing uveitis and peripheral musculoskeletal manifestations (enthesitis and dactylitis) of SpA were more complete than were comorbid conditions (diabetes, cardiovascular, and kidney disease) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Results regarding data availability and completeness

| Data source | Pooled data from 15 European registries collecting information on patients with SpA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pooled data (n=33,948) | Before January 1, 2015 (n=16,207) | From January 1, 2015 (n=21,423) | axSpA (n=21,330) | PsA (n=12,618) | ||

| Variables | No of registries with available data | Data completeness, mean % (range)a | Data completeness, mean %a | |||

| Demography | ||||||

| Age | 15 | 100 (100–100) | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Sex | 15 | 100 (100–100) | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Weight | 14 | 67 (7–100) | 71% | 64% | 68% | 65% |

| Height | 14 | 64 (13–100) | 65% | 64% | 65% | 63% |

| Lifestyle | ||||||

| Smoking | 13 | 85 (15–100) | 82% | 88% | 85% | 84% |

| Alcohol consumptionb | 4 | 29 (7–76) | 21% | 44% | 26% | 32% |

| Disease duration and classification criteria | ||||||

| Disease duration (years) | 15 | 92 (53–100) | 96% | 88% | 93% | 90% |

| Symptom duration (years) | 9 | 75 (33–100) | 72% | 78% | 75% | 74% |

| ASAS criteria | 9 | 46 (5–100) | 47% | 46% | 63% | 16% |

| Modified New York criteria | 9 | 38 (5–100) | 40% | 35% | 49% | 17% |

| CASPAR criteria | 7 | 27 (6–100) | 29% | 26% | 15% | 48% |

| Clinical characteristics at baseline | ||||||

| Swollen joint count (28) | 14 | 60 (28–100) | 59% | 61% | 45% | 85% |

| Tender joint count (28) | 14 | 56 (28–100) | 53% | 59% | 38% | 85% |

| Swollen joint count (66) | 10 | 29 (5–74) | 20% | 37% | 16% | 50% |

| Tender joint count (68) | 10 | 31 (6–76) | 21% | 39% | 17% | 54% |

| Physician global | 13 | 71 (13–92) | 71% | 71% | 64% | 82% |

| Enthesitis (MASES) | 6 | 25 (6–70) | 20% | 29% | 29% | 16% |

| Dactylitis (yes/no) | 5 | 33 (10–97) | 40% | 28% | 26% | 46% |

| Skin (PASI binary) | 4 | 40 (1–92) | 53% | 31% | 35% | 49% |

| Nails (NAPSI binary) | 2 | 44 (27–83) | 44% | 44% | 23% | 92% |

| BASMI | 8 | 26 (3–100) | 24% | 27% | 39% | 7% |

| Biological or targeted synthetic DMARD treatment | ||||||

| Name of b/tsDMARD | 15 | 100 (100–100) | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Treatment series number | 15 | 100 (100–100) | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Treatment start date | 15 | 100 (100–100) | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Treatment stop date | 15 | 53 (5–71) | 69% | 39% | 51% | 56% |

| Concomitant medication at baseline | ||||||

| Conventional synthetic (cs) DMARD | 14 | 71 (2–100) | 67% | 74% | 68% | 75% |

| Methotrexate | 14 | 66 (2–100) | 64% | 68% | 63% | 71% |

| Sulfasalazine | 14 | 63 (2–100) | 62% | 65% | 63% | 65% |

| Leflunomide | 14 | 62 (2–100) | 60% | 63% | 60% | 64% |

| Other csDMARDs | 13 | 65 (2–100) | 60% | 68% | 63% | 67% |

| Oral glucocorticoidsc | 11 | 86 (33–100) | - | 86% | 84% | 88% |

| NSAIDs | 8 | 56 (16–100) | 42% | 69% | 61% | 46% |

| Patient-reported outcomes at baseline | ||||||

| BASDAI | 15 | 63 (28–100) | 54% | 71% | 78% | 39% |

| BASFI | 11 | 59 (16–100) | 50% | 68% | 74% | 35% |

| HAQ | 12 | 68 (14–97) | 63% | 72% | 58% | 83% |

| Patient global | 14 | 82 (43–100) | 79% | 85% | 79% | 87% |

| Patient fatigue | 8 | 68 (23–90) | 57% | 79% | 71% | 64% |

| Patient pain | 13 | 77 (26–100) | 68% | 86% | 74% | 82% |

| Laboratory parameters at baseline | ||||||

| CRP | 15 | 85 (22–100) | 88% | 83% | 85% | 85% |

| ESR | 13 | 84 (46–100) | 85% | 82% | 83% | 85% |

| HLA-B27 | 14 | 67 (8–95) | 63% | 71% | 80% | 46% |

| Peripheral and extra-musculoskeletal manifestations of spondyloarthritis (ever/never) | ||||||

| Enthesitis | 5 | 78 (73–100) | 82% | 75% | 80% | 73% |

| Dactylitis | 6 | 80 (4–100) | 91% | 72% | 79% | 81% |

| Psoriasis | 12 | 56 (2–100) | 61% | 53% | 60% | 50% |

| Uveitis | 11 | 84 (4–100) | 87% | 82% | 83% | 86% |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 11 | 57 (1–100) | 61% | 53% | 60% | 51% |

| Comorbidities (ever/never) | ||||||

| Cardiovascular | 13 | 65 (10–100) | 63% | 68% | 69% | 59% |

| Diabetes | 13 | 55 (7–100) | 53% | 57% | 54% | 57% |

| Kidney disease | 12 | 66 (3–100) | 65% | 67% | 69% | 60% |

Unless otherwise stated, we used secondary pseudonymized baseline data from initiation of the first biologic (b) or targeted synthetic (ts) disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug (DMARD) treatment on patients with a clinical diagnosis of axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) and psoriatic arthritis (PsA), 18 years or older, followed in one of the participating registries since the start of their first b/tsDMARD between 2000 to 2021. Sweden has provided data on Secukinumab-treated patients only

ASAS Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society, CASPAR Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis, MASES Maastricht Ankylosing Spondylitis Enthesitis Index, PASI Psoriasis Area and Severity Index, NAPSI Nail Psoriasis Severity Index, BASMI Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index, NSAID non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug, BASDAI Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index, BASFI Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index, HAQ Health Assessment Questionnaire, CRP C-reactive protein, ESR Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, HLA-B27 Human Leukocyte Antigen subtypes B*2701-2759

aAmong registries with available data on the variable

bData based on patients who initiated a TNFi between January 1, 2009, and December 31, 2018

cData based on patients who initiated a new b/tsDMARD from January 1, 2015, and May 31, 2022

Fig. 1.

Data completeness for variables collected in axSpA (upper panel) and PsA (lower panel) overall and stratified by time-period for initiation of a b/tsDMARD treatment course, b/tsDMARD history and registry. Legend: Unless otherwise stated, we used secondary pseudonymized baseline data from initiation of the first biologic (b) or targeted synthetic (ts) disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug (DMARD) treatment on patients with a clinical diagnosis of axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) and psoriatic arthritis (PsA), 18 years or older, followed in one of the participating registries since the start of their first b/tsDMARD between 2000 and 2021. Sweden has provided data on Secukinumab-treated patients only. ASAS, Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society; CASPAR, Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis; MASES, Maastricht ankylosing spondylitis enthesitis index; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; NAPSI, Nail Psoriasis Severity Index; BASMI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index; cs, concomitant synthetic; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; PROMs, patient-reported outcome measures; BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; BASFI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index; HAQ, Health Assessment Questionnaire; CRP, C-reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; HLA-B27, Human Leukocyte Antigen subtypes B*2701-2759; EMMs, extra-musculoskeletal manifestations. *Baseline data on patients who initiated a TNFi between January 1, 2009 and December 31, 2018 (alcohol); **baseline data on patients who initiated a new b/tsDMARD from January 1, 2015, and May 31, 2022 (prednisolone); ***baseline data on patients initiating a later line b/tsDMARD (1 prior or ≥2 prior)

Variables not available in the uploaded data

Additional variables, such as physical activity, intramuscular and intra-articular use of glucocorticoids, EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D), other comorbid conditions, imaging, and adverse events were available in some registries, as reported by the registry experts (Supplementary Table S1). Data completeness for these variables was not available in this study.

Wording, recall period, and scale used for selected patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs)

An overview of selected PROMs used in axSpA across registries is presented in Table 3 and a similar overview for PsA in Supplementary Table S2. For both diagnoses, differences in the wording, recall period, and scale were observed. For patient global, the questions referred to either “overall impact due to disease activity” or “overall impact due to the rheumatic disease”. For patient pain, the questions referred to either “pain due to the rheumatic disease,” “spinal pain,” or pain non-specifically. For patient fatigue, the questions referred to either “unusual fatigue/tiredness,” “fatigue due to the disease,” or to fatigue non-specifically. For both patient global, pain and fatigue assessments, the recall periods varied from “at the moment” to “last week,” and the assessments were performed using either numeric rating scales (NRS) from 0 to 10 or 100 or visual analog scales (VAS). The BASDAI and BASFI were assessed using either NRS 0–10 or 100 mm/10 cm VAS.

Table 3.

Overview of selected patient-reported outcome measures in axSpA across registries

| Registry | Patient global assessment | Patient pain assessment | Patient fatigue assessment | BASDAI/BASFI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wordinga | Scaleb | Wordinga | Scaleb | Wordinga | Scaleb | Registered | Scaleb | |

| ATTRA (Czechia) | Please indicate below how you feel when you consider all the ways in which your illness now affects you | VAS and NRS (0–100) | How much pain has your illness caused you DURING THE PAST WEEK? | NRS (0–100) | How much of a problem has unsual fatigue been for you DURING THE PAST WEEK? | NRS (0–100) | Yes/yes [25] | VAS |

| DANBIO (Denmark) | How does the arthritis affect your overall life at the moment? | VAS | How much pain due to arthritis do you have at the moment? | VAS | How tired are you at the moment? | VAS | Yes/yes [26] | VAS |

| ESRBTR (Estonia) | Patient´s evaluation of disease activity on a VAS ranging from “no activity” to “very active”. | VAS | Patient´s evaluation of pain on a VAS ranging from “no pain” to “strong pain”. | VAS | - | - | Yes/no | NRS |

| ROBFIN (Finland) |

How is your health condition today? VAS ranging from “very good to “worst possible” |

VAS | How much pain have you been experiencing during last week? | VAS | How much fatigue have you been experiencing during last week? | VAS | Yes/yes [27] | VAS |

| ICEBIO (Iceland) | Put a mark on the line below which illustrates the disease activity on your health due to your disease during the last week | VAS | Put a mark on the line below which illustrates the pain due to your disease during the last week | VAS | Put a mark on the line below which illustrates the fatigue due to your disease during the last week | VAS | Yes/yes | VAS |

| GISEA (Italy) | Considering all the ways your arthritis has affected you, how active do you feel your arthritis is today on a scale ranging from 0 to 100? | NRS 0–100 | Numerical rating scale ranging from 0 (no pain) to 100 (worst imaginable pain) measuring actual pain intensity during the last 24 hours | NRS 0–100 | - | - | Yes/yes | VAS |

| AmSpA (Netherlands) | How active was your disease the last week? | NRS | How much back pain did you have during the night the last week? | NRS | How tired were you the last week? | - | Yes/yes | VAS |

| NOR-DMARD (Norway) | We kindly ask you to evaluate the activity in your arthritis during the last week. Considering all the symptoms you have had, how would you evaluate your condition? | VAS | How much pain have you had during the last week? | VAS | To what degree has a feeling of unusual tiredness or exhaustion been a problem for you during the last week? | VAS | Yes/no | VAS |

| Reuma.pt (Portugal) | Considering the way the disease disturbs you, how did you feel during the last week? | NRS and VAS | Please indicate the level of pain that you felt in your spine at any moment (day or night) during last week | VAS | FACIT questionnaire | - | Yes/yes [28] | VAS |

| RRBR (Romania) | Please rate how much the disease is globally affecting you, taking into account all the aspects of the disease (e.g., psoriasis and arthritis) over the past week | NRS | c | - | d | - | Yes/no | VAS |

| Biorx.si (Slovenia) | How does your disease affect you today? | NRS | How severe was the pain in the past week? | NRS | - | - | Yes/yes | NRS |

| BIOBADASER (Spain) | No specific wording, depends on each center | NRS | - | - | - | - | Yes/no [29] | VAS |

| SRQ (Sweden) | How have you felt in the last week, in general, given your rheumatic disease? | VAS | How much pain have you had in the last week due to your rheumatic disease? | VAS | How tired have you been in the last week due to your rheumatic disease? | VAS | Yes/yes [30, 31] | VAS |

| SCQM (Switzerland) | How active is your disease today? | NRS | How would you rate your overall pain in the past 7 days? | NRS | d | - | Yes/yes | VAS |

| BSRBR-AS (UK) | Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Global Score (BAS-G) | - | Pain question in SF12, EQ5D, pain 100 mm VAS | - | Chalder Fatigue Scale | - | Yes/yes [32, 33] | VAS |

NRS Numeric rating scale from 0 to 10 unless stated otherwise, VAS Visual analog scale from 0 to 100 mm, BASDAI Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index, BASFI Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index

aThe wording is based on a translation from the original language (if not English) in the online survey and follow-up interviews

bScales are evaluated visually using graphic presentation of the respective patient assessments in secondary anonymized baseline data from initiation of the first biologic (b) or targeted synthetic (ts) disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug (DMARD) treatment on patients with a clinical diagnosis of axial spondyloarthritis, 18 years or older, followed in one of the participating registries since the start of their first b/tsDMARD between 2000 to 2021. Sweden has provided data on Secukinumab treated patients only

cBASDAI pain question

dBASDAI fatigue question

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the design and data collection in 15 European SpA registries, covering ≈34,000 patients with axSpA and PsA. By collecting details of coverage, recruitment, funding, and assessment of PROMs in the participating registries, we have provided insights into potential challenges when attempting to pool data. High data completeness was observed in core demographic, clinical, and treatment-related variables, and moreover, we observed an increased data completeness of PROMs in recent years.

This study is the first to comprehensively characterize the commonalities and differences across European SpA registries. Heterogeneity across registries has been acknowledged as a factor in interpreting pooled data since EuroSpA was established in 2017, and this study provides further insights into such differences [14, 15, 34, 35]. In RA, two collaborative cross-country studies concluded that further collaboration would benefit from harmonization of data collection [16, 17]. Similarities between our study and the RA studies include the survey-based collection of information from registry experts regarding different aspects of European registries. Our study, however, adds further weight by incorporating real-world data uploaded by the registries for assessment of data completeness.

We noted large variation in coverage across registries, some covering up to 100% of eligible patients and others only a small proportion. This implies that some registry cohorts may be generally representative of patients with SpA in that country or region, whereas other cohorts may be highly selected. Such heterogeneity should be considered when pooling data across registries. Another interesting finding was that in some registries, a diagnosis could be assigned using several methods, i.e., either ICD-10, classification criteria, or expert opinion, while in two registries, classification criteria was the only method used. This may reflect that the registries have different main purposes - some of them are primarily clinical while others are mainly used for research. How a diagnosis is established is of importance since the concordance between clinical diagnoses and fulfillment of classification criteria is not complete, and the clinical characteristics of the patients may also differ according to the diagnostic strategy. In a recent study, 83% of patients with a clinical axSpA diagnosis (ICD-10 of all axSpA diagnoses combined) fulfilled either Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) or modified New York classification criteria, and those fulfilling the criteria were more often men and HLA-B27 positive but had less enthesitis [36]. To gain more insight, a future perspective would be to investigate how the different registration strategies are balanced in the registries.

We observed similar frequencies of missingness in our data and in the collated estimates previously reported by Radner et al. in European RA registries for disease duration, patient global score, patient pain, HAQ, joint counts and CRP (0–20%) and treatment with NSAID (20–40%), while our data were more complete regarding cigarette smoking and fatigue [16]. However, it should be noted that the frequencies presented by Radner et al. were self-reported estimates, while in this study they were based on calculations of real data [16]. As could be expected, the BASDAI and BASFI, which are measures developed for use in patients with ankylosing spondylitis, had more complete data in axSpA than in PsA patients, probably reflecting that the majority of the latter has a phenotype with predominantly peripheral involvement. It could also suggest that axial PsA is not routinely looked for in the clinical encounter and therefore tools to assess the axial domain of PsA are not applied in a subset of patients. In general, routine registration of PsA patients may be challenged by the heterogeneity of PsA and the large number of potentially affected domains.

Interestingly, we found higher data completeness across all PROMs in the later time period (after 2015), which may be a sign of an increasing focus on patient engagement, as illustrated by implementing online digital solutions to facilitate data collections using touch screens and apps [37–39].

Our evaluation of PROMs across registries revealed differences in the use of wording, recall period, and scale. The differences were most evident for the patient global, pain and fatigue scores, which could reflect that no specific wording, recall, or scale for the assessment of these concepts has been recommended across rheumatic diseases. However, some variation in the use of scale was still observed for the BASDAI and BASFI although these have been validated in several countries [25–33].

Regarding the wording, only rough comparisons should be made due to the probable semantic differences following the translation of the original questions performed by the registry experts. Possible explanations of the differences observed in our study are many, given the heterogeneity of the registries in general. For instance, we could speculate that data collection practices in axSpA and PsA might have been influenced by RA registries since the movement towards including PROMs as outcome measures in rheumatology started with the development of a core set for endpoints in RA [40]. Several years later, recommendations for AS-specific scores and scales for spinal pain, patient global, and fatigue were proposed in the ASAS core set [41, 42].

In line with this theory, we have seen that the majority of the SpA registries included in our study ask about pain in more general terms and not about spinal pain specifically. Conversely, since widespread pain has been shown to be a strong predictor of poor outcome [43], and spinal pain is already included in the BASDAI, the registries may also have made an active decision to consider pain more generally. The impact of such cross-registry differences in PROM wording, recall period, and scale on data from pooled analyses has not been investigated.

Some limitations to our study should be noted. First, since the online survey and follow-up interviews were conducted in a small group of experts from each registry, we cannot exclude that the responses might have differed slightly, had other registry experts been assigned the task. This limitation would, however, mainly apply to the areas where we have not presented real data for verification, e.g., in registry set-up (including coverage, funding, and data management), safety, lifestyle, and imaging. Next, since all except one registry (BSRBR-AS in the UK) are non-English, the patient assessments were translated by the registry experts from the original language to English to compare the wording. Such a translation should ideally have been done by a native speaker, who has good knowledge of both languages and then translated back by a similarly knowledgeable bilingual [44]. Furthermore, the study revealed that some key patient variables were collected in all registries, whereas considerable heterogeneity in data availability was observed for other variables. Also, the wording, recall periods, and scales used for patient assessments differed across registries. Finally, we observed variation in data completeness of patient-reported outcomes over time with an increase in recent years, perhaps reflecting a larger emphasis on their relevance.

Conclusions

This study has uncovered considerable variation in the design of axSpA and PsA registries across fifteen countries in Europe. Moreover, differences in the availability and completeness of data in general, and the wording, recall periods, and scales used for patient assessments contributed to the heterogeneity., This study might serve as a basis for examining how differences in the current data collection across registries impact the pooled analyses, thereby informing the potential need for a more unified strategy in future collaborative research.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 2. Interview guide – data mapping. S1. Data availability as reported by the registries. S2. Overview of selected patient reported outcomes in PsA across registries.

Additional file 3. Supplementary data: CRediT statement.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- axSpA

Axial spondyloarthritis

- ASAS

Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society

- BASDAI

Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index

- BASFI

Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index

- BASMI

Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index

- bDMARD

Biological disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs

- cs

Conventional synthetic

- EQ-5D

Euro Qol-5 Dimensions

- EULAR

European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology

- HAQ

Health Assessment Questionnaire

- ICD-10

The International Classification of Diseases – tenth revision

- NRS

Numeric rating scale

- NSAIDs

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- PROM

Patient-reported outcome measure

- PsA

Psoriatic arthritis

- RA

Rheumatoid arthritis

- RCN

Research Collaboration Network

- REDCap

Research Electronic Data Capture

- SpA

Spondyloarthritis

- ts

Targeted synthetic

- VAS

Visual analog scale

Authors’ contributions

LL, LMØ, SHR, TJL, AGL, MØ and MH conceptualized the study. AGL, JZ, KL, DN, BG, FI, PH, EKK, TKK, AMR, CC, ZR, IC, DDG, GJM, MH and BG collected data by completing the REDCap survey and/or participating in the follow-up interviews. LL, LMØ and SHR analyzed the data. LL drafted the manuscript, and all authors interpreted the data, read and approved the final manuscript. For further details, see CRediT (Contributor Roles Taxonomy) statement in Supplementary material.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Royal Library, Copenhagen University Library The EuroSpA Research Collaboration Network was financially supported by Novartis Pharma AG. Novartis had no influence on the data collection, statistical analyses, manuscript preparation or decision to submit the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The data in this article was collected in the individual registries and made available for secondary use through the EuroSpA Research Collaboration Network [https://eurospa.eu/#registries] Relevant patient-level data may be made available on reasonable request to the corresponding author, but will require approval from all contributing registries.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All participating registries obtained the necessary approvals (including written informed patient consent if needed) in accordance with legal, compliance and regulatory requirements from national Data Protection Agencies and/or Research Ethics Boards prior to the data transfer. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Louise Linde, Lykke M. Ørnbjerg and Simon H. Rasmussen: Research grants from Novartis; Thorvardur Jon Love: None; Anne Gitte Loft: Research Grant from Novartis, and speaking and/or consulting fees from AbbVie, Janssen, Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and UCB; Jakub Zavada: Speaker and consulting fees from Abbvie, Elli-Lilly, Sandoz, Novartis, Egis, UCB; Jiří Vencovský: Consulting and/or speaking fees from Abbvie, Biogen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Gilead, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Pfizer and UCB; Karin Laas: Consulting and/or speaking fees from Amgen, Johnson and Johnson and Novartis; Dan C. Nordstrom: Consulting and/or speaking fees from Abbvie, BMS, Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche and UCB; Tuulikki Sokka-Isler: non-financial support from DiaGraphIT, personal fees from Abbvie, BMS, Celgene, Medac, Merck, Novartis, Orion Pharma, Pfizer, Roche, Sandoz, UCB and Bohringer Ingelheim, grants from Amgen, outside the submitted work; Bjorn Gudbjornsson: Consulting and/or Speaking fees from Novartis and Nordic-Pharma; Gerdur Gröndal: None, Florenzo Iannone: Consulting and/or speaking from Abbvie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, BMS, Galapagos, Janssen, Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, UCB; Roberta Ramonda: Consulting and/or speaking fees from AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Janssens, Novartis, UCB and Pfizer; Pasoon Hellamand: Research grant from Novartis; Eirik K. Kristianslund: None; Tore K. Kvien: Fees for speaking and/or consulting last 2 years from AbbVie, Amgen, Celltrion, Gilead, Grünenthal, Novartis, Pfizer, Sandoz, UCB and research funding to Diakonhjemmet Hospital from AbbVie, BMS, Galapagos, Novartis, Pfizer and UCB; Ana M. Rodrigues: Research grant from Novartis, Pfizer, Amgen, consulting and/or speaking from Abbvie, Amgen; Maria J. Santos: Speaker fees from Abbvie, AstraZeneca, Lilly, Novartis and Pfizer; Catalin Codreanu: Speaker and consultancy fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Ewopharma, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer; Ziga Rotar: Speaker or consultancy fees from Abbvie, Novartis, MSD, Medis, Biogen, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Sanofi, Lek, Janssen; Matija Tomšič: Consulting and/or speaking fees from Abbvie, Amgen, Biogen, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Medis, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi, Sandoz-Lek; Isabel Castrejon: Speaker and/or consultancy fees from BMS, Eli-Lilly, Galapagos, Gilead, Janssen, Novartis, MSD, Pfizer, GSK; Federico Díaz-Gonzáles: None; Daniela Di Giuseppe: None; Lotta Ljung: No grants, consulting or speaking fees, but has, for Karolinska University Hospital and as register holder for the Swedish Rheumatology Register in the last years agreements with Abbvie, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Galapagos, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi, Sobi, UCB, Janssen, BMS, GSK, Otsuka; Michael J. Nissen: Consulting and/or speaking fees from AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Janssens, Novartis and Pfizer; Adrian Ciurea: Consulting and/or speaking fees from AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Pfizer; Gary J. Macfarlane: Research grant from GSK; Maureen Heddle: None; Bente Glintborg: Research grants from Pfizer, AbbVie, BMS, Sandoz; Mikkel Østergaard: Research grants from Abbvie, BMS, Merck, Celgene and Novartis, and speaker and/or consultancy fees from Abbvie, BMS, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Celgene, Eli-Lilly, Hospira, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Novo, Orion, Pfizer, Regeneron, Roche, Sandoz, Sanofi and UCB; Merete L. Hetland: Research grants from Abbvie, Biogen, BMS, Celltrion, Eli Lilly, Janssen Biologics B.V, Lundbeck Fonden, MSD, Medac, Pfizer, Roche, Samsung Biopies, Sandoz, Novartis

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Mikkel Østergaard and Merete L. Hetland contributed equally.

References

- 1.Lapadula G, Ferraccioli G, Ferri C, et al. GISEA: an Italian biological agents registry in rheumatology. Reumatismo. 2011;63:155–64. doi: 10.4081/reumatismo.2011.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Codreanu C, Mogosan C, Enache L, et al. Romanian registry of rheumatic diseases: Efficacy and safety of biologic therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(Issue Suppl 2). 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-eular.5823.

- 3.Canhão H, Faustino A, Martins F, et al. Reuma. PT - the rheumatic diseases Portuguese register. Acta Reumatol Port. 2011;36:45–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Konttinen L, Honkanen V, Uotila T, et al. Biological treatment in rheumatic diseases: Results from a longitudinal surveillance: adverse events. Rheumatol Int. 2006;26:916–22. doi: 10.1007/s00296-005-0097-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ciurea A, Scherer A, Weber U, et al. Age at symptom onset in ankylosing spondylitis: is there a gender difference? Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:1908–10. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Vollenhoven RF, Ashling J. Rheumatoid arthritis registries in Sweden. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2005;23:195–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pavelka K, Forejtová Š, Štolfa J, et al. Anti-TNF therapy of ankylosing spondylitis in clinical practice. Results from the Czech national registry ATTRA. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2009;27:958–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carmona L, de la Vega M, Ranza R, et al. BIOBADASER, BIOBADAMERICA, and BIOBADADERM: Safety registers sharing commonalities across diseases and countries. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2014;32:163–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rotar Z, Hočevar A, Rebolj Kodre A, et al. Retention of the second-line biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis failing one tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitor: data from the BioRx.si registry. Clin Rheumatol. 2015;34:1787–93. doi: 10.1007/s10067-015-3066-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Macfarlane GJ, Barnish MS, Jones EA, et al. The British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Registers in Ankylosing Spondylitis (BSRBR-AS) study: Protocol for a prospective cohort study of the long-term safety and quality of life outcomes of biologic treatment. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015;16:347. doi: 10.1186/s12891-015-0805-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ibfelt EH, Jensen DV, Hetland ML. The Danish nationwide clinical register for patients with rheumatoid arthritis: DANBIO. Clin Epidemiol. 2016;8:737–742. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S99490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glintborg B, Gudbjornsson B, Krogh NS, et al. Impact of different infliximab dose regimens on treatment response and drug survival in 462 patients with psoriatic arthritis: Results from the nationwide registries DANBIO and ICEBIO. Rheumatol (United Kingdom) 2014;53:2100–9. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keu252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kvien TK, Heiberg MS, Lie E, et al. A Norwegian DMARD register: Prescriptions of DMARDs and biological agents to patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2005;23:188–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ørnbjerg LM, Brahe CH, Askling J, et al. Treatment response and drug retention rates in 24 195 biologic-naïve patients with axial spondyloarthritis initiating TNFi treatment: routine care data from 12 registries in the EuroSpA collaboration. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:1536–1544. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brahe CH, Ørnbjerg LM, Jacobsson L, et al. Retention and response rates in 14 261 PsA patients starting TNF inhibitor treatment - Results from 12 countries in EuroSpA. Rheumatol (United Kingdom) 2020;59:1640–1650. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kez427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Radner H, Dixon W, Hyrich K, et al. Consistency and utility of data items across european rheumatoid arthritis clinical cohorts and registers. Arthritis Care Res. 2015;67:1219–1229. doi: 10.1002/acr.22602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kearsley-Fleet L, Závada J, Hetland ML, et al. The EULAR Study Group for Registers and Observational Drug Studies: Comparability of the patient case mix in the European biologic disease modifying anti-rheumatic drug registers. Rheumatol (United Kingdom) 2015;54:1074–1079. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keu446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hewlett S, Hehir M, Kirwan JR. Measuring fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review of scales in use. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:429–39. doi: 10.1002/art.22611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nikiphorou E, Radner H, Chatzidionysiou K, et al. Patient global assessment in measuring disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis: a review of the literature. Arthritis Res Ther. 2016;18:251. doi: 10.1186/s13075-016-1151-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGettigan P, Alonso Olmo C, Plueschke K, et al. Patient Registries: an Underused Resource for Medicines Evaluation: Operational proposals for increasing the use of patient registries in regulatory assessments. Drug Saf. 2019;42:1343–1351. doi: 10.1007/s40264-019-00848-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)-A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Informatics. 2019;95:103208. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ørnbjerg LM, Linde L, Georgiadis S, et al. Predictors of ASDAS-CRP inactive disease in axial spondyloarthritis during treatment with TNF-inhibitors: Data from the EuroSpA collaboration. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2022;56:152081. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2022.152081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ørnbjerg LM, Rugbjerg K, Georgiadis S, et al. One-Third of European Patients with Axial Spondyloarthritis Reach Pain Remission With Routine Care Tumor Necrosis Factor Inhibitor Treatment. J Rheumatol. 2022; 10.3899/jrheum.220459. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Šléglová O, Dušek L, Olejárová M, et al. Evaluation of status and quality of life in patients with ankylosing spondylitis - Validation of Czech versions of Bath questionnaires - BAS-G. BADAI a BASFI. Ces Revmatol. 2004;12:43–54. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pedersen OB, Hansen GO, Svendsen AJ, et al. Adaptation of the Bath measures on disease activity and function in ankylosing spondylitis into Danish. Scand J Rheumatol. 2007;36:22–7. doi: 10.1080/03009740600904268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heikkilä S, Viitanen JV, Kautianen H, et al. Evaluation of the Finnish versions of the functional indices BASFI and DFI in spondylarthropathy. Clin Rheumatol. 2000;19:464–9. doi: 10.1007/pl00011179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pimentel-Santos FM, Pinto T, Santos H, et al. Portuguese version of the bath indexes for ankylosing spondylitis patients: a cross-cultural adaptation and validation. Clin Rheumatol. 2012;31:341–6. doi: 10.1007/s10067-011-1864-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cardiel MH, Londoño JD, Gutiérrez E, et al. Translation, cross-cultural adaptation, and validation of the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI), the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) and the Dougados Functonal Index (DFI) in a Spanish speaking population wit. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2003;21:451–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cronstedt H, Waldner A, Stenström CH. The Swedish version of the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index. Reliability and validity. Scand J Rheumatol Suppl. 1999;111:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Waldner A, Cronstedt H, Stenström CH. The Swedish version of the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index. Reliability and validity. Scand J Rheumatol Suppl. 1999;111:10–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garrett S, Jenkinson T, Kennedy LG, et al. A new approach to defining disease status in ankylosing spondylitis: The bath ankylosing spondylitis disease activity index. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:2286–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Calin A, Garrett S, Whitelock H, et al. A new approach to defining functional ability in ankylosing spondylitis: The development of the bath ankylosing spondylitis functional index. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:2281–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lindström U, Di Giuseppe D, Delcoigne B, et al. Effectiveness and treatment retention of TNF inhibitors when used as monotherapy versus comedication with csDMARDs in 15 332 patients with psoriatic arthritis. Data from the EuroSpA collaboration. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80:1410–1418. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-220097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Michelsen B, Lindström U, Codreanu C, et al. Drug retention, inactive disease and response rates in 1860 patients with axial spondyloarthritis initiating secukinumab treatment: routine care data from 13 registries in the EuroSpA collaboration. RMD Open. 2020;6:e001280. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2020-001280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lindqvist E, Olofsson T, Jöud A, et al. How good is the agreement between clinical diagnoses and classification criteria fulfilment in axial spondyloarthritis? Results from the SPARTAKUS cohort. Scand J Rheumatol. 2022; 10.1080/03009742.2022.2064183. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Cheung PP, De Wit M, Bingham CO, et al. Recommendations for the Involvement of Patient Research Partners (PRP) in OMERACT Working Groups. A Report from the OMERACT 2014 Working Group on PRP. J Rheumatol. 2016;43:187–93. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.141011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.De Wit MPT, Berlo SE, Aanerud GJ, et al. European League Against Rheumatism recommendations for the inclusion of patient representatives in scientific projects. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:722–6. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.135129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Glintborg B, Jensen DV, Terslev L, et al. Nationwide, large-scale implementation of an online system for remote entry of patient-reported outcomes in rheumatology: characteristics of users and non-users and time to first entry. RMD Open. 2022;8:e002549. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2022-002549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boers M, Tugwell P, Felson DT, et al. World Health Organization and International League of Associations for Rheumatology core endpoints for symptom modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials. J Rheumatol Suppl. 1994;41:86–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van der Heijde D, Bellamy N, Calin A, et al. Preliminary core sets for endpoints in ankylosing spondylitis. Assessments in Ankylosing Spondylitis Working Group. J Rheumatol. 1997;24:2225–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Der Heijde D, Calin A, Dougados M, et al. Selection of instruments in the core set for DC-ART, SMARD, physical therapy, and clinical record keeping in ankylosing spondylitis. Progress report of the ASAS Working Group. J Rheumatol. 1999;26:951–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dean LE, MacFarlane GJ, Jones GT. Five potentially modifiable factors predict poor quality of life in ankylosing spondylitis: results from the scotland registry for ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol. 2018;45:62–9. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.160411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sousa VD, Rojjanasrirat W. Translation, adaptation and validation of instruments or scales for use in cross-cultural health care research: a clear and user-friendly guideline. J Eval Clin Pract. 2011;17(2):268–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 2. Interview guide – data mapping. S1. Data availability as reported by the registries. S2. Overview of selected patient reported outcomes in PsA across registries.

Additional file 3. Supplementary data: CRediT statement.

Data Availability Statement

The data in this article was collected in the individual registries and made available for secondary use through the EuroSpA Research Collaboration Network [https://eurospa.eu/#registries] Relevant patient-level data may be made available on reasonable request to the corresponding author, but will require approval from all contributing registries.