Abstract

Purpose: The purpose of this prospective observational study was to investigate the relationship between pretreatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and posttreatment early tumor shrinkage (ETS), and clinical outcomes in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (uHCC) who received lenvatinib, programmed death-1 inhibitors plus transcatheter arterial chemoembolization. Patients and Methods: A total of 63 uHCC patients were treated with this triple combination. Multivariate analyses to determine the independent factors associated with overall survival (OS) were employed. The link between NLR and clinical results was further analyzed. Furthermore, the predictive value of combining NLR with ETS should be investigated to stratify patients receiving treatment for survival benefits. Results: Progression-free survival and OS were 9.8 and 23.0 months, respectively, with a median follow-up of 20.8 months. On a multivariate analysis of OS, NLR was the only independent prognostic factor. Patients with NLR low (NLR < 3.2) had longer progression-free survival (19.3 vs 7.3 months, P < 0.001) and OS (28.9 vs 16.9 months, P < 0.001), higher objective response rate (86.7% vs 39.4%, P < 0.001), and a higher chance of achieving ETS ≥ 10% (ETS high) (73.3% vs 21.1%, P < 0.001) compared with patients with NLR high (NLR ≥ 3.2). The Spearman correlation analysis also showed the strong consistency between NLR and ETS (R2 = 0.6751). In the subgroup analysis, greater OS benefit was found in the NLR low/ETS high group than the NLR high/ETS low group (χ2 = 31.258, P < 0.001), while there was no survival difference for patients in the NLR low/ETS low group compared with in the NLR high/ETS high group (χ2 = 0.046, P = 0.830). Conclusion: NLR has the potential to identify which patients would benefit from this triple therapy, and when combined with ETS, it has the potential to provide greater predictive power in selecting the appropriate candidates for this combination treatment.

Keywords: hepatocellular carcinoma, combination therapy, biomarker, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, early tumor shrinkage

Introduction

Immunotherapy-based combination therapy has greatly improved the therapeutic approaches for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and demonstrating promising antitumor efficacy in recent years.1–3 Combination of atezolizumab and bevacizumab showed a higher objective response rate (ORR) and better survival compared to sorafenib in patients with unresectable HCC (uHCC), 4 and the encouraging outcomes also was obtained in the KEYNOTE 524 study. 5 Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) into systemic combination therapy may improve antitumor activity even further.6,7 Our previous study was consistent with these results that this triple combination might be effective and favorable for uHCC responders. 8 However, a subset of patients was unable to benefit clinically from this triple combination treatment. Finding effective biomarkers may determine who will benefit more. Biomarkers include serum angiopoietin 2, fibroblast growth factor (FGF) 19 (FGF19), FGF23, and vascular endothelial growth factor for TKIs.9,10 In addition, PD-L1 expression, tumor mutational burden, microsatellite instability, and plasma transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) for immunotherapy11–13 have been reported to predict tumor response, but thus far with limited efficacy.

The inflammatory response plays a critical role in tumor progression, prognosis, and therapeutic response.14,15 Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) is well identified as a biomarker to assess the systemic inflammation status, which might predict the clinical results in patients with various kinds of cancers undergoing systemic treatment.16–19 Recent research has highlighted the value of NLR in predicting response to treatment in HCC patients treated with ICIs and/or TKIs and investigated that elevated NLR is linked with poorer prognosis.8,20,21 The other indicator of short-term radiologic evaluation posttreatment, early tumor shrinkage (ETS), has also been found to be linked with the results in patients treated with systemic therapy.22–24 The relationship between NLR and ETS, as well as whether the potential of combining pretreatment NLR and posttreatment ETS to provide a more accurate prediction of outcomes in HCC patients, requires further investigation.

Thus, this research aims to explore the link between NLR and ETS, as well as the predictive value of NLR and ETS to identify the appropriate candidates for this triple combination in uHCC respondents.

Methods

Patients

In clinical practice, we conducted a prospective observational study on uHCC patients treated with lenvatinib, programmed death-1(PD-1) inhibitors, and TACE. From January 2018 to April 2020, 63 uHCC patients were enrolled at the First Department of Hepatic Surgery. Clinically or histologically affirmed HCC based on the practice guidelines proposed by the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease were included in this study: unfit for curative surgery; at least 1 measurable target lesion according to Modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (mRECIST); no prior systemic therapy; Child–Pugh scores 7 or less; good ECOG PS of 0 to 1; adequate organ function was key eligibility criteria (Adequate organ function: ① hematologic function: Absolute neutrophil count (ANC) ≥ 1.5 × 109/L; Platelets ≥50 × 109/L; Hemoglobin ≥ 9.0 g/dl (no packed red blood cell transfusion within the last 2 weeks). ② Renal function: Serum creatinine ≤ 1.5 × ULN or measured or calculated creatinine clearance ≥ 50 ml/min for participant with creatinine levels >1.5 × institutional ULN. ③ Hepatic function: Albumin > 3.0 g/dl; AST and ALT ≤5 × ULN; Total bilirubin ≤ 2 × ULN. ④ Coagulation: International normalized ratio (INR) ≤ 1.5 × ULN or aPTT ≤1.5 × ULN for patients not receiving anticoagulant therapy; INR ≤2 × ULN and APTT within normal range within 14 days before the treatment of patients receiving preventive anticoagulant therapy. ⑤ cardiac function: NYHA classification of cardiac function ≤ II, LVEF > 50%, BNP < 100 ng/L and cTnI < 0.04 ng/ml). If patients met any of the following conditions, they were considered ineligible for participation in this study, such as less than a 3-month life expectancy; uncontrollable ascites or decompensated liver function; and patients who received concurrent treatments such as chemotherapy or ablation. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. We have followed relevant Equator guidelines 25 and have de-identified all patient details.

Treatments

Lenvatinib was administered 1 week before the initial TACE. Patients were given lenvatinib at either 8 mg/day for patients weighing <60 kg or 12 mg/day for patients weighing ≥60 kg, which was stopped for 2 days before each TACE session and restarted after at least 2 days if no obvious adverse events were caused by TACE. Dose adjustments were allowed for toxicity management.

Respondents received 200 mg pembrolizumab or 240 mg toripalimab intravenously every 3 weeks. PD-1 inhibitors were initiated 1 day before the initial TACE. Treatment interruption was allowed if patients suffered severe adverse events. Respondents were given the treatment until they experienced unacceptable toxicity or disease progression. The maximum treatment cycle of pembrolizumab or toripalimab was 35 cycles.

The TACE procedure was carried out by the same senior interventional physicians with more than 15 years of experience described previously. 26 Hepatic angiography was conducted using the femoral artery approach according to the Seldinger technique. When possible, the catheter tip was inserted into the tumor's feeding artery. An emulsion of pirarubicin and lipiodol was injected, followed by Gelfoam fragments to embolize the tumor-feeding vessel. TACE was repeated on demand, primarily based on performance status, hepatic function, and viable area proportion during the follow-up period.

Outcomes and Assessments

Every two months, a routine follow-up investigation was carried out, which included a physical examination, laboratory tests, and radiological imaging. The laboratory tests included urine and blood routine, thyroid function and cardiac enzyme concentration, liver and renal function, HBV-DNA (for HBsAg-positive person), and AFP. The imaging evaluation were performed by Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) or computer tomography (CT), and when indicated, an 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography (FDG-PETCT). OS was measured from the time of initial treatment until the last follow-up. PFS was calculated from the time of first treatment until progression according to mRECIST or death due to any cause. mRECIST criteria were used to assess therapeutic responses, which included progressive disease (PD), stable disease (SD), partial response (PR), and complete response (CR). The percentage of patients with CR and PR was used to calculate the ORR, while the disease control rate (DCR) was calculated as ORR plus SD. NLR was calculated as the ratio of ANC to absolute lymphocyte count. ALBI score = (log10 bilirubin × 0.66) + (albumin × − 0.085), (grade I, score ≤ − 2.60; grade II, score − 2.60 to ≤ − 1.39; grade III, score > − 1.39); Serum concentrations of AFP were measured with the ARCHITECT immunoassay (Abbott Diagnostics, Chicago, IL, USA). ETS was described as the percentage of tumor shrinkage at the time of first follow-up (8 weeks after treatment), by investigating the change of the sum of longest diameters of the target lesions equated to that on baseline according to RECIST v1.1. 27 As previously stated, a 10% ETS was established as the cutoff value for distinguishing early-stage therapeutic activity response. 22

Statistical Analysis

Outcomes were analyzed employing STATA, version 15.0. Fisher's exact test or a χ2 test was employed for categorical variables, whereas continuous variables were equated by the t-test or Mann–Whitney U test for variables with skewed distribution. The median value of the NLR was used as the cutoff criterion to divide patients into high- and low-subgroups. Survivals were estimated with the Kaplan–Meier method and then compared by a log-rank test. Cox regression was used to perform univariate and multivariate analyses of prognostic factors. Factors with a P value < 0.2 in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate analysis. The correlation of NLR and ETS was evaluated by Spearman analysis. To investigate the combined effect of NLR and ETS on patients’ survival, we divided patients into 4 groups based on NLR and ETS levels: NLR low/ETS high, NLR low/ETS low, NLR high/ETS high, and NLR high/ETS low. Statistical significance was regarded at P < 0.05.

Results

Clinical Characteristics

Between January 2018 and April 2020, 63 uHCC patients who met the inclusion criteria were included in this study. The follow-up ended on March 31, 2021, with a median duration of 20.8 months (range, 9.0-38.5). The median duration of exposure was 8.9 months (range, 1.8-35.5) for lenvatinib. The average TACE procedure was 2.3 (range, 1-4) (Supplementary Table 1), and the median cycle of PD-1 inhibitor administration was 10 (range, 2-32). Baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. The subjects’ median age was 51 years (IQR, 44-60 years), and 57 (90.5%) were males. Most cases had hepatitis B infection (48, 76.2%). At the outset, 53 (84.1%) and 10 (15.9%) patients had ECOG PS of 0 and 1, respectively. Child–Pugh scores of 5, 6, and 7 were recorded in 51 (81.0%), 9 (14.2%), and 3 (4.8%), respectively. Macroscopic portal vein invasion (MVI) was seen in 21 patients (33.3%), had extrahepatic spread (EHS) was seen in 33 (52.4%). Most patients were BCLC stage C (69.8%). No important baseline differences between NLR low and NLR high groups were noticed. There was no significant difference observed between HBV and NLR, ETS (Supplementary Table 2). Ten patients received pembrolizumab, and 53 patients received toripalimab as an immunotherapy regimen.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Patients Enrolled in This Study.

| Characteristic | Total (N = 63) | NLR low (N = 30) | NLR high (N = 33) | P value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (Q1, Q3), years | 51(44-60) | 51(44-57) | 51(43-61) | 0.940 |

| Sex, male/female | 57/6 | 25/5 | 32/1 | 0.158 |

| ECOG PS, 0/1 | 53/10 | 26/4 | 27/6 | 0.857 |

| BMI, median (Q1, Q3), kg/m2 | 23.1(20.8-25.1) | 22.3(20.1-25.0) | 23.4(20.8-25.1) | 0.477 |

| Etiology, HBV/Nonviral | 48/15 | 22/8 | 26/7 | 0.612 |

| PLT, median (Q1, Q3), 10^9/L | 187(141-221) | 180(140-221) | 187(136-222) | 0.834 |

| Cr, median (Q1, Q3), μmol/L | 74(66-85) | 73(66-83) | 76(65-86) | 0.735 |

| Child–Pugh score, 5/6/7 | 51/9/3 | 24/4/2 | 27/5/1 | 0.785 |

| ALBI, Grade 1/2 | 38/25 | 16/14 | 22/11 | 0.280 |

| AFP, ≥/<400, ng/ml | 22/41 | 10/20 | 12/21 | 0.801 |

| Target tumor size, ≥/<7.4, cm | 33/30 | 17/13 | 16/17 | 0.516 |

| Target tumor numbers, 1/2/≥3 | 15/42/6 | 8/18/4 | 7/24/2 | 0.481 |

| MVI, +/- | 21/42 | 8/22 | 13/20 | 0.285 |

| EHS, +/- | 33/30 | 19/11 | 14/19 | 0.097 |

| BCLC, B/C | 19/44 | 7/23 | 12/21 | 0.260 |

Note: Values are expressed as numbers or medians (Q1, Q3), Q1, and Q3 are 25th percent and 75th percent of interquartile range.

*P values showed the comparison results of baseline characteristics between NLR low group and NLR high group.

Abbreviations: NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; BMI, body mass index; PLT, platelet; Cr, creatinine; AFP, α-fetoprotein; MVI, macroscopic vascular invasion; EHS, extrahepatic spread; BCLC, Barcelona Clinical Liver Cancer system.

Survival Outcomes of the Triple Combination Therapy

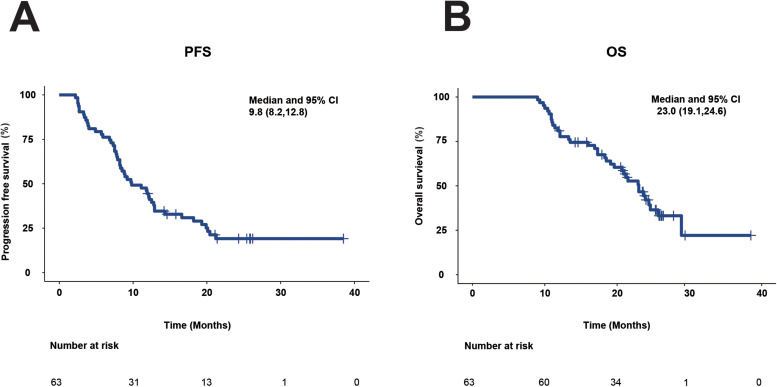

At the March 31, 2021 cutoff, 49 (77.8%) patients had disease progression, and 37 (58.7%) had died in the overall population. The overall cohort's median PFS and OS were 9.8 months (95%CI, 8.2-12.8; Figure 1A) and 23.0 months (95% CI, 19.1-24.6; Figure 1B), respectively.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier plots of PFS and OS for all patients. (A) PFS. (B) OS.

Prognostic Factors for OS

Uni- and multivariate analyses linked with OS are detailed in Table 2. In univariate analysis, NLR (<3.2) was recognized as important prognostic factors for longer OS. Multivariate analysis also revealed that only NLR low (<3.2) was an independent prognostic factor for better results.

Table 2.

Univariate and Multivariate Analyses for OS.

| Factors | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95%CI | P | HR | 95%CI | P | |

| Age,<55 years | 1.041 | 0.542-2.000 | 0.903 | |||

| Gender, female | 0.230 | 0.032-1.681 | 0.148 | 0.590 | 0.075-4.657 | 0.617 |

| NLR, <3.2 | 0.131 | 0.055-0.310 | <0.001 | 0.145 | 0.060-0.351 | <0.001 |

| ALBI grade,1 | 0.893 | 0.462-1.725 | 0.736 | |||

| AFP,<400 ng/ml | 0.942 | 0.473-1.877 | 0.865 | |||

| Target tumor size,<7.4 cm | 0.930 | 0.487-1.776 | 0.825 | |||

| Target tumor number,1 | 1.402 | 0.675-2.913 | 0.364 | |||

| BCLC stage, B | 0.966 | 0.465-2.007 | 0.927 | |||

| MVI, absence | 0.768 | 0.395-1.491 | 0.435 | |||

| EHS, absence | 0.577 | 0.297-1.121 | 0.105 | 0.828 | 0.417-1.644 | 0.590 |

Note: The bold values highlighted the factors with significant difference.

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; AFP, α-fetoprotein; DCP, Des-gamma-carboxy prothrombin; BCLC, Barcelona Clinical Liver Cancer; MVI, macrovascular invasion; EHS, extrahepatic spread.

Survival Outcomes Based on Pretreatment NLR

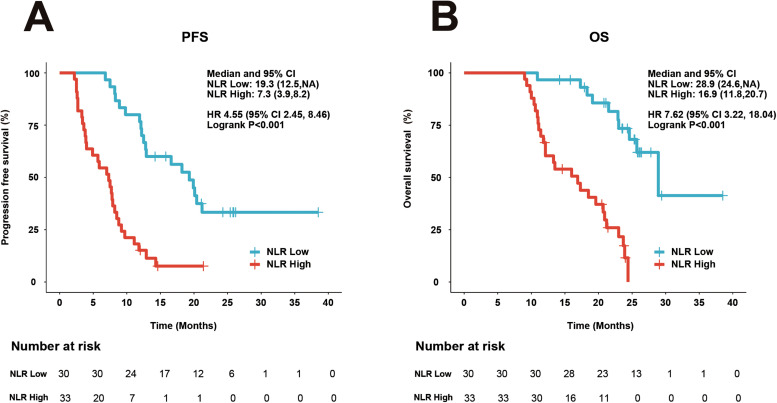

We further investigate the relationship between NLR and survival results. Of the 63 respondents in this cohort, 30 respondents had NLR < 3.2 (NLR low) and 33 patients had NLR ≥ 3.2 (NLR high). Respondents with NLR high attained importantly poorer PFS (HR = 4.55; 95%CI 2.45-8.46; P < 0.001) (Figure 2A) and OS (HR = 7.62; 95%CI 3.22-18.04; P < 0.001) (Figure 2B) compared with the patients with NLR low.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier plots of PFS and OS by NLR status. (A) PFS. (B) OS.

Abbreviations: NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Survival Outcomes Based on Posttreatment ETS

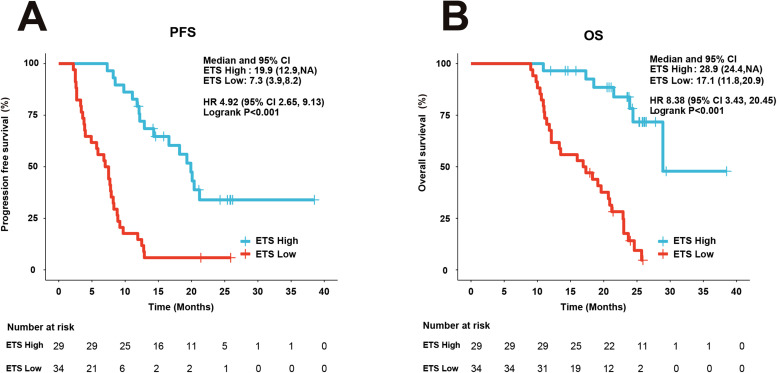

The posttreatment ETS value on clinical results was also investigated in our research. Respondents with ETS low had importantly poorer PFS (HR = 4.92; 95%CI 2.65-9.13; P < 0.001) (Figure 3A) and OS compared with respondents with ETS high (HR = 8.38; 95%CI 3.43-20.45; P < 0.001) (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier plots of PFS and OS by ETS status. (A) PFS. (B) OS.

Abbreviations: ETS, early tumor shrinkage; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Association Between NLR and Therapeutic Response

Table 3 shows tumor response data. This cohort included 11 (17.5%) respondents with CR, 28 (44.4%) respondents with PR, 16 (25.4%) respondents with SD, and 8 (12.7%) respondents with PD, according to mRECIST. The corresponding ORR was 61.9%, whereas the DCR was 87.3%. Additionally, 29 (46%) respondents attained ETS great with tumor shrinkage ≥10% at the first follow-up.

Table 3.

Therapeutic Efficacy of Response and ETS.

| Variable | Total (N = 63) No. (%) | NLR low (N = 30) No. (%) | NLR high (N = 33) No. (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete response (CR) | 11 (17.5) | 10 (33.3) | 1 (3.0) | 0.002 |

| Partial response (PR) | 28 (44.4) | 16 (53.4) | 12 (36.4) | |

| Stable disease (SD) | 16 (25.4) | 4 (13.3) | 12 (36.4) | |

| Progressive disease (PD) | 8 (12.7) | 0 (0) | 8 (24.2) | |

| Objective response rate (ORR) | 39(61.9) | 26 (86.7) | 13 (39.4) | <0.001 |

| Disease control rate (DCR) | 55(87.3) | 30 (100) | 25 (75.8) | 0.012 |

| Early tumor shrinkage (ETS) ≥ 10% | 29 (46) | 22 (73.3) | 7 (21.1) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio.

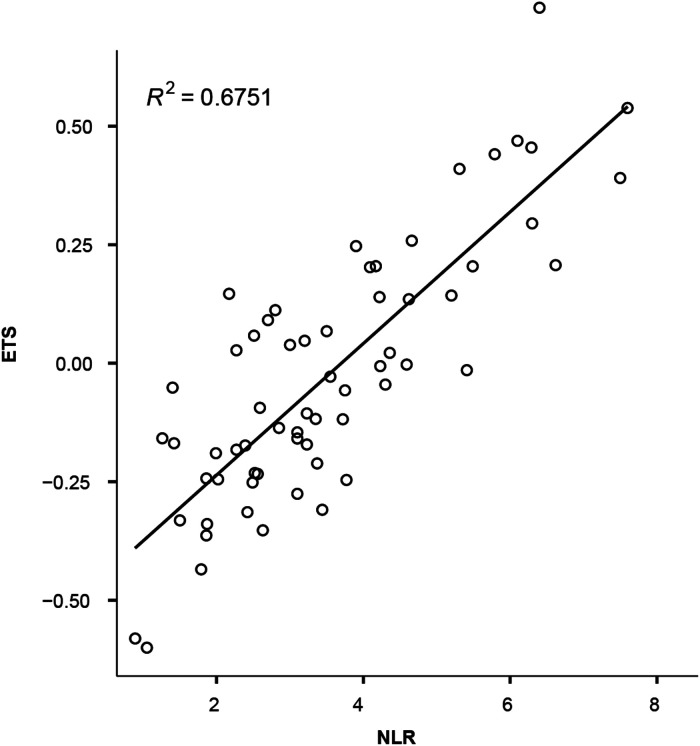

The therapeutic responses differed significantly between the NLR low and NLR high groups. The ORR and DCR were substantially greater in NLR low patients than in NLR high patients. Similarly, respondents with low NLR had a higher chance of achieving ETS high (22 of 30, 73.3%) than respondents with high NLR (7 of 33, 21.1%) (P < 0.001). Furthermore, the strong correlation between NLR and ETS was also validated (Spearman correlation coefficient squared 0.6751) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Correlation between ETS and NLR.

Abbreviations: NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; ETS, early tumor shrinkage; R, Spearman correlation coefficient.

Combined Predictive Value of NLR and ETS

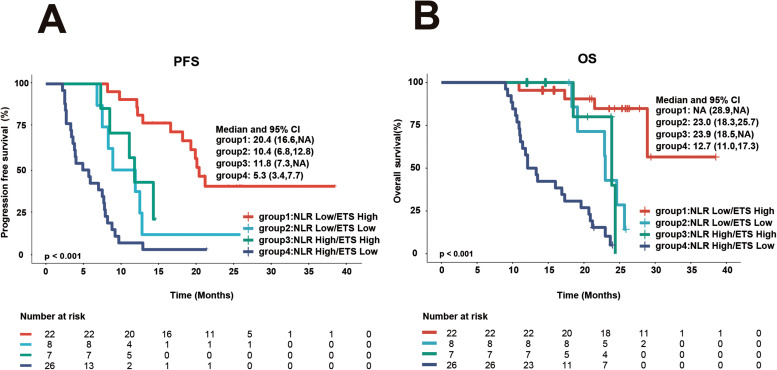

Patients were divided into 4 subgroups based on their NLR and ETS patterns: NLR low/ETS high (22 cases), NLR low/ETS low (8 cases), NLR high/ETS high (7 cases), and NLR high/ETS low (26 cases). The best results were revealed in the NLR low/ETS high group, and the poorest results were recorded in the NLR high/ETS low group (Figure 5), while no statistically significant difference in PFS and OS (Figure 5, Tables 4 and 5) was found between the NLR low/ ETS low and NLR high/ ETS high groups.

Figure 5.

PFS and OS according to a combined NLR and ETS categorization. (A) PFS. (B) OS.

Abbreviations: NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; ETS, early tumor shrinkage; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Table 4.

Intergroup Comparison of PFS Based on Combination of NLR and ETS.

| Group comparison | χ2 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | 2 | 9.018 | 0.003 |

| 3 | 8.479 | 0.004 | |

| 4 | 34.291 | <0.001 | |

| Group 2 | 3 | 0.356 | 0.551 |

| 4 | 4.582 | 0.032 | |

| Group 3 | 4 | 7.266 | 0.007 |

Note: Group 1, NLR low/ETS high; group 2, NLR low/ETS low; group 3, NLR high/ETS high; group 4, NLR high/ETS low.

Abbreviations: NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; ETS, early tumor shrinkage.

Table 5.

Intergroup Comparison of OS Based on Combination of NLR and ETS.

| Group comparison | χ2 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | 2 | 8.833 | 0.003 |

| 3 | 4.549 | 0.033 | |

| 4 | 31.258 | <0.001 | |

| Group 2 | 3 | 0.046 | 0.830 |

| 4 | 7.678 | 0.006 | |

| Group 3 | 4 | 7.828 | 0.005 |

Note: Group 1, NLR low/ETS high; group 2, NLR low/ETS low; group 3, NLR high/ETS high; group 4, NLR high/ETS low.

Abbreviations: NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; ETS, early tumor shrinkage.

Discussion

The combination of lenvatinib, PD-1 inhibitors, and TACE demonstrated promising antitumor activity in uHCC patients in this prospective observational study. We discovered a median PFS of 9.8 months by mRECIST and a median OS of 23.0 months. The favorable therapeutic response might be attributed to the synergistic effect of this triple combination, 8 although the exact mechanism remains unclear. The affirmed ORR of 61.9% in the current research was greater than 24% to 46% of dual combination treatment of ICIs and antiangiogenics or TKIs.4,5,28,29 Similarly, a great ORR of 75.7% to 84.2% has also been revealed for uHCC patients with this combination in many studies.6,7 Hence, this combination of lenvatinib, PD-1 inhibitors, and TACE may be a promising and potential strategy for uHCC patients.

Nonetheless, nearly 40% of patients in this cohort did not receive an objective response, emphasizing the importance of identifying potential predictors for better clinical decisions. Many biomarkers dependent on molecules or genes have been found in HCC patients who were treated with systemic treatment,9,12,30–34 but each of them has not been described to be predictive markers of therapeutic response so far.

The pretreatment NLR, a well-established indicator to assess systemic inflammatory status, is widely employed to forecast the clinical efficacy of systemic treatment in a variety of cancers.35–37 According to data from two phase 3 studies of SHARP and Asia Pacific, importantly greater benefit from sorafenib treatment was noticed in patients with low NLR. 20 Recent research has illustrated that low NLR was also linked with better survival in patients with uHCC treated with lenvatinib. 38 A similar outcome was looked into for immunotherapy. In retrospective research, 1714 patients with 16 different cancer kinds received ICIs, and greater response rates and better survival gain were discovered in the lower NLR group after ICI therapy across diverse cancer types. 21 In our research, we investigated the predictive role of NLR in patients treated with this triple treatment. Multivariate analysis revealed that NLR < 3.2 (NLR low) was an independent predictor of advanced OS, and importantly greater survival gain was seen in NLR low patients (PFS: 19.3 vs 7.3 months, P < 0.001; OS: 28.9 vs 16.9 months, P < 0.001). As a result, as a pretreatment indicator, NLR could be used to predict clinical benefit in uHCC patients receiving this triple combination.

The posttreatment ETS as an early radiologic marker of response to systemic treatment was closely linked to predicting clinical results in a variety of cancers.27,39,40 In recent years, ETS has been presented to predict clinical gain in HCC patients undergoing systemic therapy. ETS was an independent predictor of both OS and PFS in patients receiving sorafenib in the SORAMIC trial, identifying responders to therapy earlier than mRECIST. 41 Retrospective research also revealed similar outcomes in HCC patients treated with lenvatinib and proposed that ETS could allow earlier assessment of the treatment response. 22 In lung cancer patients treated with atezolizumab, achieving ETS was significantly associated with longer OS and PFS, and was an independent predictor for superior OS and PFS. 24 Just as in our research, patients with ETS high had importantly better PFS and OS than those with ETS low (PFS: 19.9 vs 7.3 months, P < 0.001; OS: 28.9 vs 17.1 months, P < 0.001).

In this research, the further investigation reported that NLR and ETS were strongly correlated, denoting that patients with NLR low were more likely to achieve ETS high. More significantly, ETS might be used as a complementary indicator of NLR to better screen the patients who could gain from this treatment. While respondents with NLR low revealed better survival gain, it is worth noting that a subset of NLR high respondents, if they were able to attain ETS high following treatment, had no important difference in survival from that in the NLR low/ETS low group (OS: 23.9 vs 23.0 months, P = 0.830). Thus, ETS is a promising predictor of clinical results for this combination treatment and could help guide therapy decision-making earlier along with pretreatment NLR. The limitations of this study include a relatively small sample size. Thus, we will enroll a greater number of patients for further validation in future study.

However, the present research had some restrictions. A small number of respondents were investigated, and only 1 center of hepatobiliary surgery was included in the research. So, the findings should be interpreted discreetly. Further multicenter studies with large sample size are warranted to affirm these findings.

Conclusion

This research illustrated that a combination of lenvatinib, PD-1 inhibitors, and TACE provided promising clinical benefits for uHCC patients. The NLR has the potential to identify which patients would benefit from this triple treatment. The ETS may be employed as a complementary indicator of the NLR to better screen patients who could benefit from this treatment.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-tct-10.1177_15330338231206704 for Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio and Early Tumor Shrinkage as Predictive Biomarkers in Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patients Treated With Lenvatinib, PD-1 Inhibitors, in Combination With TACE by Shuping Qu, Dong Wu and Zhiming Hu in Technology in Cancer Research & Treatment

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-tct-10.1177_15330338231206704 for Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio and Early Tumor Shrinkage as Predictive Biomarkers in Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patients Treated With Lenvatinib, PD-1 Inhibitors, in Combination With TACE by Shuping Qu, Dong Wu and Zhiming Hu in Technology in Cancer Research & Treatment

Supplemental material, sj-docx-3-tct-10.1177_15330338231206704 for Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio and Early Tumor Shrinkage as Predictive Biomarkers in Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patients Treated With Lenvatinib, PD-1 Inhibitors, in Combination With TACE by Shuping Qu, Dong Wu and Zhiming Hu in Technology in Cancer Research & Treatment

Abbreviations

- CR

complete response

- CT

computer tomography

- DCR

disease control rate

- ECOG PS

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status

- EHS

extrahepatic spread

- ETS

early tumor shrinkage

- FDG-PETCT

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography

- FGF

fibroblast growth factor

- ICIs

Immune checkpoint inhibitors

- mRECIST

Modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- MVI

macroscopic portal vein invasion

- NLR

neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio

- ORR

objective response rate

- PD

progressive disease

- PD-1

programmed death-1

- SD

stable disease

- TACE

transcatheter arterial chemoembolization

- TGF-β

transforming growth factor β

- TKIs

tyrosine kinase inhibitors

- uHCC

unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma

- ULN

upper limit of normal

Footnotes

Data Availability: All data and materials presented in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval: This study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Third Affiliated Hospital of Second Military Medical University, Shanghai, China (approval # EHBHKY2017-K-025; date: October 2017 to October 2020).

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

ORCID iDs: Shuping Qu https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7086-1541

Zhiming Hu https://orcid.org/0009-0009-9330-2764

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Edeline J, Meyer T, Blanc JF, et al. New challenges facing systemic therapies of advanced HCC in the era of different first-line immunotherapy-based combinations. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(23):5868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cannella R, Lewis S, da Fonseca L, et al. Immunotherapy-based treatments of hepatocellular carcinoma: AJR expert panel narrative review. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2022;219(4):533-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pelizzaro F, Farinati F, Trevisani F. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in hepatocellular carcinoma: current strategies and biomarkers predicting response and/or resistance. Biomedicines. 2023;11(4):1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(20):1894-1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Finn RS, Ikeda M, Zhu AX, et al. Phase Ib study of lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(26):2960-2970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song T, Lang M, Lu W, et al. Conversion of initially unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) with triple-combination therapy (lenvatinib, anti-PD-1 antibodies, and transarterial therapy): a retrospective analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(4_suppl):413. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang X, Zhu X, Liu C, et al. The safety and efficacy of transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) + lenvatinib + programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) antibody of advanced unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(4_suppl):453. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qu S, Zhang X, Wu Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of TACE combined with lenvatinib plus PD-1 inhibitors compared with TACE alone for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma patients: a prospective cohort study. Front Oncol. 2022;12:874473. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.874473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Llovet JM, Peña CE, Lathia CD, Shan M, Meinhardt G, Bruix J. Plasma biomarkers as predictors of outcome in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(8):2290-2300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finn RS, Kudo M, Cheng AL, et al. Pharmacodynamic biomarkers predictive of survival benefit with lenvatinib in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: from the phase III REFLECT study. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27(17):4848-4858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feun LG, Li YY, Wu C, et al. Phase 2 study of pembrolizumab and circulating biomarkers to predict anticancer response in advanced, unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2019;125(20):3603-3614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El-Khoueiry AB, Sangro B, Yau T, et al. Nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (CheckMate 040): an open-label, non-comparative, phase 1/2 dose escalation and expansion trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10088):2492-2502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dhanasekaran R, Nault JC, Roberts LR, Zucman-Rossi J. Genomic medicine and implications for hepatocellular carcinoma prevention and therapy. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(2):492-509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 2002;420(6917):860-867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell. 2010;140(6):883-899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Capone M, Giannarelli D, Mallardo D, et al. Baseline neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and derived NLR could predict overall survival in patients with advanced melanoma treated with nivolumab. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6(1):74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bilen MA, Martini DJ, Liu Y, et al. The prognostic and predictive impact of inflammatory biomarkers in patients who have advanced-stage cancer treated with immunotherapy. Cancer. 2019;125(1):127-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yun NK, Rouhani SJ, Bestvina CM, et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is a predictive biomarker in patients with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutated advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) therapy. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(6):1426. doi: 10.3390/cancers13061426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Santoni M, Buti S, Conti A, et al. Prognostic significance of host immune status in patients with late relapsing renal cell carcinoma treated with targeted therapy. Target Oncol. 2015;10(4):517-522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bruix J, Cheng AL, Meinhardt G, Nakajima K, De Sanctis Y, Llovet J. Prognostic factors and predictors of sorafenib benefit in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: analysis of two phase III studies. J Hepatol. 2017;67(5):999-1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Valero C, Lee M, Hoen D, et al. Pretreatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and mutational burden as biomarkers of tumor response to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takahashi A, Moriguchi M, Seko Y, et al. Early tumor shrinkage as a predictive factor for outcomes in hepatocellular carcinoma patients treated with lenvatinib: a multicenter analysis. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(3):754. doi: 10.3390/cancers12030754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fucà G, Corti F, Ambrosini M, et al. Prognostic impact of early tumor shrinkage and depth of response in patients with microsatellite instability-high metastatic colorectal cancer receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Immunother Cancer. 2021;9(4):e002501. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2021-002501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hopkins AM, Kichenadasse G, Karapetis CS, Rowland A, Sorich MJ. Early tumor shrinkage identifies long-term disease control and survival in patients with lung cancer treated with atezolizumab. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8(1):e000500. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2019-000500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(8):573-577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fu Z, Li X, Zhong J, et al. Lenvatinib in combination with transarterial chemoembolization for treatment of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (uHCC): a retrospective controlled study. Hepatol Int. 2021;15(3):663-675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cremolini C, Loupakis F, Antoniotti C, et al. Early tumor shrinkage and depth of response predict long-term outcome in metastatic colorectal cancer patients treated with first-line chemotherapy plus bevacizumab: results from phase III TRIBE trial by the Gruppo Oncologico del Nord Ovest. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(6):1188-1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ren Z, Xu J, Bai Y, et al. Sintilimab plus a bevacizumab biosimilar (IBI305) versus sorafenib in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (ORIENT-32): a randomised, open-label, phase 2-3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(7):977-990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu J, Shen J, Gu S, et al. Camrelizumab in combination with apatinib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (RESCUE): a nonrandomized, open-label, phase II trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27(4):1003-1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bonneville R, Krook MA, Kautto EA, et al. Landscape of microsatellite instability across 39 cancer types. JCO Precis Oncol. 2017;2017. doi: 10.1200/PO.17.00073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ang C, Klempner SJ, Ali SM, et al. Prevalence of established and emerging biomarkers of immune checkpoint inhibitor response in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2019;10(40):4018-4025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamauchi M, Ono A, Ishikawa A, et al. Tumor fibroblast growth factor receptor 4 level predicts the efficacy of lenvatinib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2020;11(5):e00179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hsu WF, Wang HW, Chen CK, et al. Alpha-fetoprotein response predicts treatment outcomes in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors with or without tyrosine kinase inhibitors or locoregional therapies. Am J Cancer Res. 2021;11(12):6173-6187. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee CH, DiNatale RG, Chowell D, et al. High response rate and durability driven by HLA genetic diversity in patients with kidney cancer treated with lenvatinib and pembrolizumab. Mol Cancer Res. 2021;19(9):1510-1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Soest RJ, Templeton AJ, Vera-Badillo FE, et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic biomarker for men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer receiving first-line chemotherapy: data from two randomized phase III trials. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(4):743-749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bagley SJ, Kothari S, Aggarwal C, et al. Pretreatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a marker of outcomes in nivolumab-treated patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2017;106:1-7. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2017.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chrom P, Stec R, Semeniuk-Wojtas A, Bodnar L, Spencer NJ, Szczylik C. Fuhrman grade and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio influence on survival in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with first-line tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2016;14(5):457-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tada T, Kumada T, Hiraoka A, et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is associated with survival in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma treated with lenvatinib. Liver Int: Off J Int Assoc Study Liver. 2020;40(4):968-976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vivaldi C, Fornaro L, Cappelli C, et al. Early tumor shrinkage and depth of response evaluation in metastatic pancreatic cancer treated with first line chemotherapy: an observational retrospective cohort study. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11(7):939. doi: 10.3390/cancers11070939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grünwald V, Dietrich M, Pond GR. Early tumor shrinkage is independently associated with improved overall survival among patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a validation study using the COMPARZ cohort. World J Urol. 2018;36(9):1423-1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Öcal O, Schinner R, Schütte K, et al. Early tumor shrinkage and response assessment according to mRECIST predict overall survival in hepatocellular carcinoma patients under sorafenib. Cancer Imaging. 2022;22(1):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-tct-10.1177_15330338231206704 for Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio and Early Tumor Shrinkage as Predictive Biomarkers in Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patients Treated With Lenvatinib, PD-1 Inhibitors, in Combination With TACE by Shuping Qu, Dong Wu and Zhiming Hu in Technology in Cancer Research & Treatment

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-tct-10.1177_15330338231206704 for Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio and Early Tumor Shrinkage as Predictive Biomarkers in Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patients Treated With Lenvatinib, PD-1 Inhibitors, in Combination With TACE by Shuping Qu, Dong Wu and Zhiming Hu in Technology in Cancer Research & Treatment

Supplemental material, sj-docx-3-tct-10.1177_15330338231206704 for Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio and Early Tumor Shrinkage as Predictive Biomarkers in Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patients Treated With Lenvatinib, PD-1 Inhibitors, in Combination With TACE by Shuping Qu, Dong Wu and Zhiming Hu in Technology in Cancer Research & Treatment