Abstract

Nursing terminologies like the Omaha System are foundational in realizing the vision of formal representation of social determinants of health (SDOH) data and whole-person health across biological, behavioral, social, and environmental domains. This study objective was to examine standardized consumer-generated SDOH data and resilience (strengths) using the MyStrengths+MyHealth (MSMH) app built using Omaha System. Overall, 19 SDOH concepts were analyzed including 19 Strengths, 175 Challenges, and 76 Needs with additional analysis around Income Challenges. Data from 919 participants presented an average of 11(SD = 6.1) Strengths, 21(SD = 15.8) Challenges, and 15(SD = 14.9) Needs. Participants with at least one Income Challenge (n = 573) had significantly (P < .001) less Strengths [9.4(6.4)], more Challenges [27.4(15.5)], and more Needs [15.1(14.9)] compared to without an Income Challenge (n = 337) Strengths [13.4(4.5)], Challenges [10.5(8.9)], and Needs [5.1(10.0)]. This standards-based approach to examining consumer-generated SDOH and resilience data presents a great opportunity in understanding 360-degree whole-person health as a step towards addressing health inequities.

Keywords: nursing terminology, Omaha System, social determinants of health, standards, interoperability

BACKGROUND AND SIGNIFICANCE

Social determinants of health (SDOH) are the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, and live and are known to influence health outcomes.1,2 The World Health Organization advocates for addressing SDOH as fundamental for reducing health inequities.2 National initiatives, such as the Future of Nursing 2020 to 2030, advocate for the use of SDOH data to advance health equity.3–6 Additionally, these reports explicitly address the need for nursing expertise in generating and applying data to support SDOH initiatives. Use of standardized terminologies can advance the use of SDOH data by enhancing structured data capture and sharing across entities.7,8 Further, to address SDOH effectively, it is essential to incorporate a whole-person approach, which takes into account a person’s environment, physical and psychosocial aspects, and health-related behaviors.9

Multiple factors contribute to SDOH and individual or family income has been identified as a critical element.2 Income alone poses a barrier to accessing healthcare and can lead to poor health outcomes directly and through varied mechanisms.7,10 Emerging programs focusing on income have been shown to be successful in addressing overall health outcomes.11,12 However, little is known how income affects whole-person health from an individuals’ perspective.

Informatics methods such as standardized terminology have been used to document SDOH. The Omaha System, a multidisciplinary health terminology, represents both physical signs/symptoms but also environmental, psychosocial, and health behaviors components.13 Prior studies have used the Omaha System to represent whole-person health including SDOH and strengths (indicator of resilience).14,15 Strengths are defined as health assets: skills, capabilities, actions, talents, and potential in each family member, each family, and the community.4,16

The Omaha System consists of 3 inter‐related standardized instruments: The Problem Classification Scheme (patient assessment/problem list), the Problem Rating Scale for Outcomes (problem evaluation), and Intervention Scheme (used for care planning and services).13 The Problem Classification Scheme includes 42 nonoverlapping concepts within 4 domains of health: Environmental, Psychosocial, Physiological, and Health‐related behaviors. A concept is a neutral term used to describe health within the Omaha System. Each of the 42 concepts includes a specific definition along with unique signs/symptoms.13

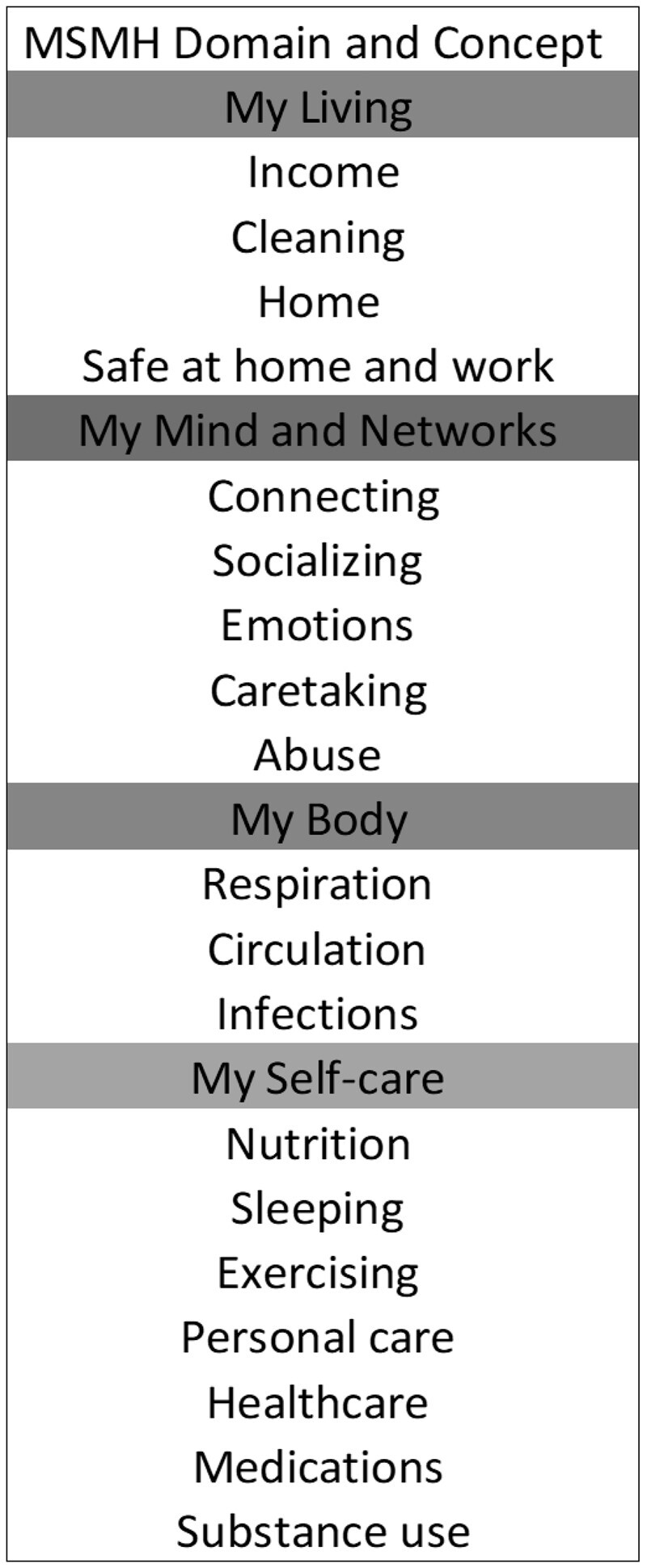

Most current methods to collect SDOH have been from the health providers’ perspective. It is increasing valuable to include the individuals’ perspective. To examine whole-person health, including SDOH, from the consumers’ perspective, the Omaha System has been translated into Simplified Omaha System Terms (SOST) The Terms have been validated by the community and are at the fifth grade reading level.17 The mobile application, MyStrengths+MyHealth (MSMH) incorporates SOST to capture whole-person health data across 4 domains and have been renamed to My Living (Environmental), My Mind and Networks (Psychosocial), My Body (Physiological), and My Self-care (Health-related behaviors). In MSMH, the Status rating scale is used to identify “Strengths” as a status score of “4” (minimal signs/symptoms) or “5” (no signs/symptoms). Omaha System signs/symptoms were renamed “Challenges” and are defined as “yes,” “no,” or “none apply.” The “Needs” are related to the Intervention scheme for each concept and describe specific activities in 4 categories: Teaching, Guidance, and Counseling (Info/Guidance); Treatments and Procedures (Hands‐On Care); Case Management (Care Coordination); Surveillance (Check‐Ins); and can select any, all, or “No Needs” if none apply for that concept (Figure 1).13 MSMH has been used in various community settings for individuals to self-report Strengths, Challenges, and Needs.18–21

Figure 1.

MyStrengths+MyHealth Income concept Strengths-Challenges-Needs.

OBJECTIVE

The objective of this study was to examine deidentified consumer-generated health data from MSMH application collected August 2020–February 2021. The study aims were to: (1) Examine and describe self-reported strengths, challenges, and needs for all participants (N = 919); and (2) Compare self-reported strengths, challenges, and needs for participants with (N = 573) and without (N = 337) at least one challenge in the Income concept.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This retrospective, observational study of existing deidentified MyStrengths+MyHealth (MSMH) data. The study was approved by the University of Minnesota, Institutional Review Board. MSMH data were collected using MSMH app via phones, iPads, or tablets. Participants (18 years and older) were recruited via community outreach (Health Fair and a Midwestern State Fair) and via social media (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and LinkedIn) outreach between August 2020 and August 2021. All participation was voluntary and participants were given a gift card ($10) or a drawstring backpack as incentive for completing MSMH. We obtained consent within MSMH by the statement: “It is your choice to take part in this health report. It is your choice to answer any of the questions. Your answers are kept safe. Your unidentified data can be used for research studies.” Participants selected: “I have read the above information. By continuing, I am consenting to participate in the study”. If they did not agree with the consent statement, participants were not allowed to continue in the application. All data were stored in the university-provided secure data shelter environment. All data are self-reported and included: Age as category (18–24; 25–44; 45–64; and 65+), Self-identified Gender (Male; Female; Nonbinary; Transgender), Marital status (Divorced; Married; Other; Partnered; Single; Widowed), Race (Asian; Black/African American; Native American/Alaskan; Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander; 2 or more; Other; White), and Ethnicity (Hispanic/Latinx; Non-Hispanic/Non-Latinx). Income (<$25 000; $25 000–$49 999; $50 000–$74 999; $75 000–$99 999; $100 000–$149 999; $150 000; or more).

In this study, MSMH was customized to capture the SDOH concepts and included a total of 19 strengths, 5 challenges, and 76 needs. The concepts selected are based on the National Academies of Medicine (NAM) SDOH domains and previous SDOH Omaha System Research that mapped Omaha System concepts to the NAM SDOH domains (Figure 2) (See Supplementary Material for full concept definitions and challenges).22,23

Figure 2.

Selected simplified Omaha System terms concepts.

To examine economic instability, we selected those with and without at least one self-reported Challenge in the Income concept. The Income concept was selected based on literature identifying economic instability as a major social driver of SDOH.7,24 The Income concept is defined as “money from wages, pensions, subsidies, interest, dividends, or other sources available for living and health care expenses.” The 5 challenges associated with the Income concept include low/no income, uninsured medical expenses, difficulty with money management, able to buy only necessities, and difficulty buying necessities.13 All data were examined using IBM SPSS (version 28) to conduct descriptive and inferential statistics. We conducted a chi-squared analysis and stratified Income Challenges by Income categories.

RESULTS

Of the total 919 participants, the majority were between the ages 25–44 years (65.3%), female (56.3%), white (83.8%), married (63.6%), non-Hispanic (74.5%), and income level between $75 000 and $99 000 (40.2%). Overall participants had an average of 11(SD = 6.1) Strengths, 21(SD = 15.8) Challenges, and 15(SD = 14.9) Needs. The most frequent Strengths was Infection (68.4%) (meaning no infection), followed by Breathing (68.0%) and Medications (66.5%). The most frequent Challenge was Emotions (80.0%), followed by Nutrition (78.8%), and Exercising (76.4%). The most frequent Need was Emotions (61.0%) followed by Income (56.9%), and Exercising (55.8%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Strengths, Challenges, and Needs overall by domain and concept

|

Over half (63.0%) reported having at least one Income Challenge and 56.9% reported as having at least one Need in Income. Those with at least one Income Challenge (n = 573) had significantly fewer Strengths (P < .001) and more Challenges (P < .001) and Needs (P < .001) compared to those without Income Challenges (N = 337) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Average Strengths, Challenges, and Needs overall and those with and without Income Challenges

| All (N = 919) | With Income Challenges (N = 573) | Without Income Challenges (N = 337) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Strengths | 11.1 (SD = 6.1) | 9.5 (SD = 6.4) | 13.4 (SD = 4.5) | <.001 |

| Average Challenges | 21.2 (SD = 15.8) | 27.4 (SD = 15.5) | 10.5 (SD = 8.9) | <.001 |

| Average number of concepts with Challenges | 11.7 (SD = 6.6) | 15.1 (SD = 5.4) | 5.8 (SD = 4.0) | <.001 |

| Average Needs | 15.1 (SD = 14.9) | 21.2 (SD = 14.1) | 5.1 (SD = 10.0) | <.001 |

| Average number of concepts with Needs | 8.9 (SD = 7.5) | 12.4 (SD = 6.5) | 3.0 (SD = 4.8) | <.001 |

SD: standard deviation.

For those with at least one Challenge in the Income concept (n = 573), the most frequent Income Challenge was hard to manage my money (25.9%), followed by only able to buy what I need (22.4%), not enough income (20.5%), too many health care bills (19.3%), and hard to buy the things I need (9.5%). The income category with the most Income Challenges was $75 000–$99 999 (40.2%), followed by <$25 000 (23.0%), $50 000–$74 999 (17.9%), and $25 000–$49 999 (15.2%). For the Income group ($75 000–$99 999) (n = 148), the 2 notable responses were too many health care bills (22.2%), and hard to buy the things I need (21.6%).

DISCUSSION

This retrospective, observational study found respondents despite having Challenges and Needs, overall participants reported a fair number of Strengths. Those with at least one Income Challenge had significantly less Strengths and more Challenges and Needs compared to those without Income Challenges. Participants with the third highest income category ($75 000–$99 999) had the most Income Challenges specifically reporting “too many healthcare bills” and “hard to buy the things I need.” The use of standardized consumer-generated health data using comprehensive nursing terminology such as the Omaha System can inform a whole-person perspective of health. The ability to collect and analyze standardized SDOH data across populations using a standards-based tool such as MSMH app aligns with national initiatives to support nurse driven solutions in addressing health inequities.

Overall participants self-reported a fair number of strengths, despite having Challenges and Needs and if all 42 concepts had been assessed more strengths would have been likely as seen in other studies.19,21,25 Emerging research has shown a person’s strengths (or resilience) may help to offset negative effects of chronic conditions such as cardiovascular disease, mild cognitive impairment, and pain.25–28 Additionally, the most frequent reported Challenges (Emotions, Nutrition, Exercising) and most frequent Needs (Emotions, Income, Exercising) aligns with previous research.19,21,25 Given these are frequently reported, this can inform future health promotion and educational programs for nurses and local public health agencies. Future research should address connecting those that report Challenges such as Emotions (eg, local mental health resources/clinics) or Exercising (eg, local gyms, walking programs, or exercise clubs based on ability and needs) with community-based programs to assist these health challenges and needs.

The finding that over half of the participants had at least one Income Challenge (63.0%) and at least one Income Need (56.9%) aligns with the literature to show the economic hardship during the pandemic.29,30 Additionally, those with at least one Income Challenge had significantly fewer Strengths and more Challenges and Needs as compared to those without Income Challenges highlights the critical impact financial strain can have on overall health outcomes.7,31 Additionally, the finding that those in the third highest income category ($75 000–$99 999) had the most Income Challenges. Specifically reporting “too many healthcare bills” and “hard to buy the things I need,” was surprising. A detailed analysis is needed to explore if this was a limited finding due to the pandemic or a broader issue for this income bracket. For example, this group may have had established a higher standard of living but with limited financial reserves and income were lost, there was limited capacity to maintain a living standard thus making this group more vulnerable to financial stresses.29 This further supports the need for a comprehensive whole-person assessment from the individuals’ perspective may find potential hidden strengths, health challenges and needs in unexpected populations. Additionally, emerging evidence shows antipoverty programs have shown positive results.11,12 Therefore, future research should explore how a whole-person assessment such as MSMH can aid in addressing income challenges and promoting whole-person care plans in such large-scale community programs.

The use of MSMH aligns to national recommendations to collect, integrate, and use SDOH data.7,32 The app enables self-report of a whole-person perspective through the SOST assessment, that includes SOH as well as resilience. National initiatives such as the Gravity Project have been established to develop consensus-based data standards to improve the collection and sharing of SDOH data.33 Nursing terminologies like the Omaha System are foundational in realizing the vision of formal representation of these data.22,23 Standards-based tools such as the MSMH app provide consumer-generated whole-person SDOH data on concepts such as Emotions, Income, and Substance use.19 The strengths of this study lie in its utilization of the standardized nursing terminology, which enhance the rigor and reliability of the collected data.

The incorporation of Strengths, Challenges, and Needs provide actionable data for the public, community health practitioners, and policy makers. This research fills a gap by moving from acknowledging the importance of collecting SDOH data to collecting this data directly from the consumer using a mobile application with standardized terminology. For example, nurses could use this data to inform the development of targeted public health interventions, particularly for those facing financial challenges. Further, self-reported data from MSMH based on a standardized terminology has the potential to incorporate the consumer’s perspective within the EHR and contribute to longitudinal consumer-generated health data. Limitations with this study are inherent to all observational data and limit generalizability. Additionally, this study was conducted at the height of COVID-19 and therefore individuals may have more income challenges than a typical time-period and not generalizable. Future research should include an in-depth comparative study of Income Challenges differences between groups that includes throughout and after the pandemic period.

CONCLUSION

This study highlights the need to examine whole-person health as factors such as Income (financial strain) exhibit more challenges and needs in the overall assessment. It also presents an opportunity to leverage an individuals’ strengths to overcome health challenges. These findings underscore the value of standardized consumer-generated health data in gaining an individuals’ perspective of SDOH factors. This study demonstrates the potential of nursing terminologies, such as the Omaha System, scalable by embedding in tools like the MSMH app to support semantic interoperability of SDOH data to advance population health.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors express gratitude to the MSMH study participants and would like to acknowledge the Center for Nursing Informatics at the University of Minnesota, School of Nursing.

Contributor Information

Robin R Austin, School of Nursing, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA.

Sripriya Rajamani, School of Nursing, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA.

Ratchada Jantraporn, School of Nursing, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA.

Anna Pirsch, School of Nursing, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA.

Karen S Martin, Martin Associates, Omaha, Nebraska, USA.

FUNDING

This work was supported by funding from a Clinical and Translational Science Institute (CTSI) COVID-19 Rapid Response Award from the University of Minnesota.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

RRA and SR collaborated on the writing of this manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material is available at Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association online.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data were collected using MSMH app with participant consent for purposes of specific studies as noted in IRB approvals. These are deidentified data and will be shared on a case-by-case basis based upon requests to the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

- 1. US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Healthy People 2030. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. 2021. https://health.gov/healthypeople. Accessed September 10, 2021.

- 2. World Health Organization. Social Determinants of Health. 2019. https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health. Accessed February 5, 2023.

- 3. Maxwell J, Tobey R, Barron C, et al. National Approaches to Whole-Person Care in the Safety Net. 2014: 1–35. https://www.dhcs.ca.gov/provgovpart/Documents/Waiver%20Renewal/Workforce1_WPC_JSI.pdf. Accessed January 20, 2023.

- 4. Sminkey PV. The “whole-person” approach: understanding the connection between physical and mental health. Prof Case Manag 2015; 20 (3): 154–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine. The Future of Nursing 2020–2030: Charting a Path to Achieve Health Equity. Washington, DC; 2021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. National Institutes of Nursing Research (NINR). National Institute of Nursing Research 2022–2026 Strategic Plan. 2022. https://www.ninr.nih.gov/aboutninr/ninr-mission-and-strategic-plan. Accessed February 20, 2023.

- 7. Whitman A, Lew ND, Chappel A, et al. Addressing Social Determinants of Health: Examples of Successful Evidence-Based Strategies and Current Federal Efforts. 2022. https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/sdoh-evidence-review. Accessed February 2, 2023.

- 8. NORC University Chicago and AHIMA. Social Determinants of Health Data: Survey Results on the Collection, Integration, and Use. 2022. https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/e2b650cd64cf84aae8ff0fae7474af82/SDOH-Evidence-Review.pdf. Accessed February 26, 2023.

- 9. National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. NCCIH Strategic Plan FY 2021–2025: Mapping the Pathway to Research on Whole Person Health. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Health; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2030: Economic Stability. 2022. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/economic-stability. Accessed January 10, 2023.

- 11. Sun S, Huang J, Hudson DL, et al. Cash transfers and health. Annu Rev Public Health 2021; 42: 363–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Courtin E, Allen HL, Katz LF, et al. Effect of expanding the earned income tax credit to Americans without dependent children on psychological distress. Am J Epidemiol 2022; 191 (8): 1444–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Martin KS. The Omaha System: A Key to Practice Documentation and Information Management. Reprinted 2nd ed. Omaha, NE: Health Connections Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Austin R, Monsen K, Alexander S.. Capturing whole-person health data using mobile applications. Clin Nurse Spec 2021; 35 (1): 14–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Austin RR, Mathiason MA, Lu S-C, et al. Toward clinical adoption of standardized mHealth solutions: the feasibility of using MyStrengths+MyHealth consumer-generated health data for knowledge discovery. Comput Inform Nurs 2022; 40 (2): 71–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Carter J, Zawalski S, Sminkey PV, et al. Assessing the whole person: case managers take a holistic approach to physical and mental health. Prof Case Manag 2015; 20 (3): 140–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Austin RR, Martin CL, Jones RC, et al. Translation and validation of the Omaha System into English-language simplified Omaha System terms. Kontakt 2022; 24 (1): 48–54. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Agboola O, Austin RR, Monsen KA.. Developing partnerships to examine community strengths, challenges, and needs in Nigeria: a pilot study. Interdiscip J Partnersh Stud 2022; 9: 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rajamani S, Austin RR, Geiger-Simpson E, et al. Understanding whole-person health and resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond: a cross-sectional and descriptive correlation study. JMIR Nurs 2022; 5 (1): e38063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Austin R, Rajamani S, Jones RC, et al. A community-based participatory intervention in the United States using data to shift the community narrative from deficits to strengths. Am J Public Health 2022; 112 (S3): S275–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Austin RR, Jones RC, Dominguez A, et al. Shifting the opioid conversation from stigma to strengths: opportunities for developing community-academic partnerships. Interdiscip J Partnersh Stud 2022; 9 (1): 2. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Monsen KA, Brandt JK, Brueshoff BL, et al. Social determinants and health disparities associated with outcomes of women of childbearing age who receive public health nurse home visiting services. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2017; 46 (2): 292–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Monsen KA, Peterson JJ, Mathiason MA, et al. Discovering public health nurse–specific family home visiting intervention patterns using visualization techniques. West J Nurs Res 2017; 39 (1): 127–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Forchuk C, Dickins K, Corring D.. Social determinants of health: housing and income. Healthc Q 2016; 18Spec No: 27–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Austin RR, Mathiason MA, Lindquist RA, et al. Understanding women’s cardiovascular health using MyStrengths+MyHealth: a patient-generated data visualization study of strengths, challenges, and needs differences. J Nurs Scholarsh 2021; 53 (5): 634–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hassett AL, Finan PH.. The role of resilience in the clinical management of chronic pain. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2016; 20 (6): 39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Meléndez JC, Satorres E, Redondo R, et al. Wellbeing, resilience, and coping: are there differences between healthy older adults, adults with mild cognitive impairment, and adults with Alzheimer-type dementia? Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2018; 77: 38–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Aungst H, Baker M, Bouyer C, et al. Identifying Personal Strengths to Help Patients Manage Chronic Illness. Cleveland, OH: Center for Community Health Integration. 2019. https://www.pcori.org/research-results/2012/identifying-personal-strengths-help-patients-manage-chronic-illness. Accessed February 12, 2023. [PubMed]

- 29. Chen J, Vullikanti A, Santos J, et al. Epidemiological and economic impact of COVID-19 in the US. Sci Rep 2021; 11 (1): 20451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ettman CK, Abdalla SM, Cohen GH, et al. Low assets and financial stressors associated with higher depression during COVID-19 in a nationally representative sample of US adults. J Epidemiol Community Health 2021; 75 (6): 501–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bierman A, Upenieks L, Glavin P, et al. Accumulation of economic hardship and health during the COVID-19 pandemic: social causation or selection? Soc Sci Med 2021; 275: 113774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Advancing SDoH Health IT Enabled Tools and Data Interoperability: eCDS and Data Tagging Project. https://oncprojectracking.healthit.gov/wiki/display/ASHIETDI/Advancing+SDoH+Health+IT+Enabled+Tools+and+Data+Interoperability+Home. Accessed February 26, 2023.

- 33. Gravity Project. Gravity Project. 2021. https://thegravityproject.net/. Accessed March 2, 2022.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data were collected using MSMH app with participant consent for purposes of specific studies as noted in IRB approvals. These are deidentified data and will be shared on a case-by-case basis based upon requests to the corresponding author.