Abstract

BACKGROUND

Students with IDD and the staff who support them were largely in-person during the 2021–2022 school year, despite their continued vulnerability to infection with SARS-CoV-2. This qualitative study aimed to understand continued perceptions of weekly SARS-CoV-2 screening testing of students and staff amidst increased availability of vaccinations.

METHODS

23 focus groups were held with school staff and parents of children with IDD to examine the perceptions of COVID-19 during the 2021–22 school year. Responses were analyzed using a directed thematic content analysis approach.

RESULTS

Four principal themes were identified: strengths and opportunities of school- and district- level mitigation policies; experience at school with the return to in-person learning; facilitators and barriers to participation in SARS-CoV-2 screening testing; and perceptions of SARS-CoV-2 testing in light of vaccine availability.

IMPLICATIONS FOR SCHOOL HEALTH POLICY, PRACTICE, AND EQUITY

Despite the increased availability of vaccines, school staff and families agreed that saliva-based SARS-CoV-2 screening testing helped increase comfort with in-person learning as long as the virus was present in the community.

CONCLUSION

To keep children with IDD in school during the pandemic, families found SARS-CoV-2 screening testing important. Clearly communicating school policies and mitigation strategies facilitated peace of mind and confidence in the school district.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2 testing, COVID-19 School Testing, COVID-19 Vaccinations, Children with IDD, Intellectual and developmental disabilities

BACKGROUND

Schools for typically developing students have shown to be safe when mitigation strategies, including masking adherence, increasing classroom ventilation, encouraging proper hand hygiene, and social distancing, are followed.1,2 However, children with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) are more vulnerable to contracting SARS-CoV-2 infections and, if infected, have increased morbidity and mortality.3 Heightened risks may be due to the child’s underlying medical condition(s), inability to effectively perform the mitigation strategies, and/or socioeconomic effects and other barriers limiting access to health care.3,4 In view of these risks and the accompanying challenges with implementing mitigation strategies at schools for children with IDD, parents/caregivers (parents) and school staff were reticent to resume in-person learning for these children.5

As part of the Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostic Testing for Underserved Populations (RADx UP) initiative of the National Institutes for Health, weekly saliva-based SARS-CoV-2 testing was implemented in six schools in the Special School District of Saint Louis County (SSD) in November 2020 as part of a research study to assess the best methods by which to conduct COVID-19 testing in schools.6,7 These schools are SSD-managed public separate special education schools. Since the implementation period, the school-based transmission rate was found to be 1% within the study participants. This further supports the current research that general population schools have a relatively low rate of transmission (approximately 2%), and adds promising data for schools that support children with IDD.8,9 Through focus groups held in November and December 2020 (time point 1), our team learned the saliva-based testing methodology was much preferred for both children with IDD and school staff, many of whom also preferred the convenient location of school-based testing.10 While families had the option to determine if their students would attend school in-person or virtually during the 2020–2021 school year, the state of Missouri limited options for all students for the 2021–2022 school year.11 Students who preferred to attend school virtually were required to do so through accessing the state of Missouri’s learning online portal, which did not offer tailored instruction to meet the unique needs of students with IDD. Therefore, the percentage of in-person students increased from 63% in the 2020–2021 school year to 100% in the 2021–2022 school year, per SSD’s Evaluation and Research Administrator (Matt Traughber, PhD, email communication, August 8, 2022). With such an increase in the number of people in school buildings, weekly SARs-CoV-2 testing became even more essential for the 2021–2022 school year in order to prevent transmission of COVID-19. Other mitigation measures, such as masking, social distancing, and reminders of hand hygiene, were in place; however, administrators reported 70% mask compliance during this time period. Even still, evidence suggests that routine testing can reduce and limit the spread of COVID-19 in schools.12–15 SSD administrators eagerly participated in a second school year of weekly testing in order to support students and staff to stay in school.

Having supported the implementation of SARS-CoV-2 testing throughout SSD during the 2020–2021 school year, we hosted follow-up discussion sessions with school staff and parents to understand how the 2021–2022 school year was going. In particular, we set out to assess the SSD community’s perception of testing in light of the availability of vaccinations. Through focus groups held in January and February 2022, we identified the perceived impact of COVID-19 mitigation strategies and school policies on the school community. Examples included perceptions of and exposure to the weekly school-based SARS-CoV-2 testing program and sentiments towards the COVID-19 vaccine. At the time of data collection, vaccines were widely available for those over 15 years old, while vaccines for those 15 and under were not yet available.16

METHODS

We conducted a qualitative study to understand how COVID-19 affected the school experience for staff, families, and students, and the impact of a weekly SARS-CoV-2 screening testing program.6,17 The Washington University Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Participants

This study utilized a convenience sample. Parents of students enrolled at SSD schools and staff working at these schools were invited to participate in directed focus groups. Principals at participating schools sent recruitment flyers electronically directly to parents and school staff through school communications (e.g., via email, PeachJar—a school messaging application) on behalf of the study team. Flyers were reviewed by a community advisory board (CAB), comprised of parents, school representatives (e.g., nurses, school staff), and an SSD leadership and staff workgroup. School staff were eligible if they were currently employed as a teacher or staff at an SSD school offering the weekly SARS-CoV-2 screening testing program. Parents were eligible if their child or children were currently attending an SSD school offering the testing program. Eligible participants were invited to join a virtual focus group.

Participants received project overview and consent information documents. Verbal consent was provided at the beginning of each session. Participants were asked to complete an online survey to collect demographic information, including but not limited to gender identity, age, race, ethnicity, and highest level of education completed. Participants were asked a series of questions related to COVID-19. They were asked if they had ever received a SARS-CoV-2 test, and if so, ever tested positive for COVID-19. Participants were also asked to report their COVID-19 vaccination status.

Instrumentation [Table 4]

Table 4:

Focus Group Guide

| Question* | Asked to Parents | Asked to Staff |

|---|---|---|

| How has this school year been going compared to last year? | X | X |

| What are the top risks related to COVID-19 that are weighing on you/your child about being at school in-person? | X | X |

| What impact does access to COVID-19 testing have on you and the school community? If possible, provide examples. | X | X |

| What sorts of factors did you consider when deciding whether to participate/to have your student participate in COVID-19 testing at your school? | X | X |

| What challenges or concerns, if any, do you have around being tested weekly for COVID-19? | X | X |

| We will now share a set of 6 messages on the screen. Do you remember seeing any of these materials sent or posted from the school that encouraged weekly COVID-19 testing? | X | X |

| If so, where do you remember seeing these messages, and in what format? | X | X |

| Has the increased availability of vaccines changed your comfort level with you/your student attending school in-person? Why or why not? | X | X |

| What challenges or concerns, if any, do you have around you/your student being vaccinated against COVID-19? | X | X |

| Many schools are requiring universal masking. Do you think SSD should continue to implement the mandate for those who are able to mask? Why or why not? | X | X |

| Looking ahead, what lessons learned from how COVID-19 is being addressed in your school should be considered when planning for the future? | X | X |

| Thank you, that is all the questions we have for today. Is there anything else still weighing on your mind about COVID-19 and what it means to return to in-person learning that I didn’t ask about? | X | X |

Note that the wording of the question in this table reflects both how questions were asked to parents (e.g., how does your student feel about COVID-19) as well as staff (e.g., how do you feel about COVID-19).

The main objectives for the focus groups were to understand the perceptions of parents and school staff about: 1) the continued impact of COVID-19 on the SSD community; and 2) the facilitators and barriers to participation in weekly saliva-based SARS-CoV-2 screening testing for students and school staff, particularly amidst the increased availability of COVID-19 vaccines. Participants were asked to provide feedback about the impact of COVID-19 on the return to in-person school; facilitators and barriers to participating in a weekly screening testing program; exposure to and perceptions of messages related to SARS-CoV-2 testing; perceived risks, barriers and benefits to receiving a COVID-19 vaccine; and the perceived impact of COVID-19 mitigation strategies and school policies on the school community. Separate facilitation guides were developed for focus groups with the two stakeholder groups. The CAB and SSD workgroup’s feedback informed the final versions.

Procedure

We conducted virtual focus groups with parents of students and school staff (educators, support staff, therapists). In total, we hosted 23—13 with parents and 10 with staff. Participants were offered a $50 gift card incentive for their engaged participation. Focus groups occurred between January 11 and February 7, 2022. Parent/caregiver focus groups lasted an average of 70 minutes, and staff focus groups lasted an average of 53 minutes. Focus groups were conducted virtually via Zoom.18 Each session was recorded. Audio files were transcribed by an external transcription vendor, then formatted and checked for accuracy by research assistants.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic characteristics. The qualitative methodology employed to analyze focus group data was a directed thematic content analysis.19 The research team used an existing codebook containing 24 descriptive codes from data analysis conducted at time point 1.10 A total of 16 additional codes were added based on the current topic areas and facilitation guides.20An iterative process was used to develop the codebook. Three trained qualitative analysts (LV, AS, LR) tested the codebook by coding two transcripts independently; they then compared their coding and modified the codebook as needed. Transcripts were then imported into an NVivo 13 project (, where the consensus-validated codes were applied to the text units of each transcript.21 For the purposes of this study, text units were defined as individual blocks of text containing both a facilitator’s question and participants’ responses to that prompt. Each text unit could have multiple codes assigned to it depending on content.

Three team members (LR, AS, LV) were the primary coders. To ensure reliability across coders and validate consistent understanding and application of each code, individual coders coded the same three transcripts (2 staff transcripts and 1 parent/caregiver transcript) independently. From this independent coding, inter-rater reliability (Cohen’s kappa coefficient) was calculated using NVivo. The coders reviewed any codes where the κ <0.8 and came to consensus. An overall inter-rater reliability of κ=0.85 was achieved among the three coders, exceeding Cohen’s suggested threshold of κ ≤0.8 for nearly perfect agreement.22 The remaining transcripts were coded independently. Each code’s assigned content was then exported, separated by code, into code report documents. From these code reports, theme reports were then produced using a directed thematic analysis approach. Iterative thematic aggregation was then conducted to identify recurring, prominent, or distinct themes.19 This process was driven using a grounded theory approach, wherein themes were derived inductively from the data. This is distinct from deductive analysis, which tests existing thematic hypotheses.22, 23 A grounded theory approach allowed the team to be guided by the uniqueness of the data and the SSD community.

RESULTS

A total of 155 people participated in 21 focus groups, 87 of whom were school staff and 68 were parents. All six SSD schools were represented in both parent/caregiver and school staff focus groups. Participant demographic information is shown in Table 1, including gender, age, race, ethnicity, and highest level of education completed.

Table 1:

Demographics of Focus Group Participants

| School Staff (n = 87) | Parent/Caregivers (n = 68) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | |

| Gender * | ||||

| Male | 9 | 10.3 | 6 | 8.8 |

| Female | 67 | 77.0 | 49 | 72.1 |

| Missing | 11 | 12.6 | 13 | 19.1 |

| Age | ||||

| 18–24 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2.9 |

| 25–34 | 17 | 19.5 | 5 | 7.6 |

| 35–44 | 22 | 25.3 | 16 | 23,5 |

| 45–54 | 21 | 24.1 | 18 | 26.5 |

| 55+ | 15 | 17.2 | 11 | 16.1 |

| Missing | 12 | 13.8 | 16 | 23.5 |

| Race * | ||||

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 2.9 |

| Black or African American | 8 | 9.2 | 24 | 35.3 |

| White or Caucasian | 67 | 77.0 | 25 | 36.8 |

| Multiracial or Biracial | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 4.4 |

| Missing | 12 | 13.8 | 14 | 20.6 |

| Ethnicity | 3 | 3.4 | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 73 | 83.9 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 11 | 12.6 | 54 | 79.4 |

| Missing | 14 | 20.6 | ||

| Education * | ||||

| Less than high school | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 2.9 |

| High school or GED | 1 | 1.1 | 4 | 5.9 |

| Some college, but no degree | 3 | 3.4 | 8 | 11.8 |

| Associate or Bachelor degree | 30 | 34.4 | 25 | 36.8 |

| Master, Professional, or Doctorate degree | 42 | 48.3 | 15 | 22.1 |

| Missing | 11 | 12.6 | 14 | 20.6 |

| Ever tested for COVID-19 | ||||

| Yes | 76 | 87.4 | 48 | 70.6 |

| No | 0 | 12.6 | 7 | 10.3 |

| Missing | 11 | 12.6 | 13 | 19.1 |

| Ever tested positive for COVID-19 | ||||

| Yes | 27 | 31.0 | 25 | 36.8 |

| No | 49 | 56.3 | 22 | 32.4 |

| N/A* | 0 | 0.0 | 7 | 10.3 |

| Missing | 11 | 12.6 | 13 | 19.1 |

Only gender, race, and education categories where n > 0 were included

N/A indicates participant never tested for COVID, so status is unknown.

Across the focus groups, the research team identified 200 theme statements. These themes were then reviewed for points of convergence and merged into 70 unique theme statements. 25 key theme statements were then identified based on the frequency with which they were mentioned in focus groups and their actionable implications for school health. These theme statements fell into one of five subject domains: participant COVID-19 experience; communication about school policies; school experience; COVID-19 testing; and COVID-19 vaccination. Several unique themes alsoemerged for between parents and staff. Illustrative supporting quotes are included in the respective tables to provide additional context for each theme statement.

Participant COVID-19 Experience [Table 1]

Of all participants who responded to the COVID-19 test experience questions (n=131), 124 had previously been tested for SARS-CoV-2, and 52 (42%) had tested positive (7 said they had not been tested, 24 chose not to answer). Of those who tested positive, 27 were school staff and 25 were parents. 115 people reported they were fully vaccinated, with an average of 87% vaccination rate across stakeholder groups. 6% of parents and 4% of staff were either hesitant or had no plans to get vaccinated.

Communication About School Policies [Table 2]

Table 2:

Barriers and Facilitators to Effective School Policies & Mitigation Strategies

| Theme | Illustrative Quote | Parents | Staff |

|---|---|---|---|

| Desire for more rigorous contact tracing |

|

X | X |

| Often-changing guidelines as a stressor |

|

X | X |

| Students unable to mask or need redirection |

|

X | X |

| Lack of staff support by school administration |

|

X | |

| Concerns about relaxation of mitigation strategies due to COVID-fatigue |

|

X | |

| Supportive of continued school mask mandate while virus is present in the community |

|

X | X |

| School COVID guidelines confusing or contradictory |

|

X | |

| Anxiety around exposure to students or household members |

|

X | X |

| Concern that parents send students to school while displaying symptoms of COVID-19 |

|

X | X |

| Weekly screening testing provided peace of mind for those who participated |

|

X | X |

| Weekly screening testing at school was convenient |

|

X | X |

| Not aware of screening testing at their school |

|

X | |

| Testing unnecessary for those who are asymptomatic and/or fully vaccinated |

|

X | |

| Did not participate in testing so as not to miss school due to quarantine if positive |

|

X | |

| Supportive of continued testing into 2022–2023 school year |

|

X | X |

| Mistrust of saliva-based test |

|

X | X |

| Saliva-based methodology as facilitator to participation |

|

X | X |

| Exposure to HCRL messages promoting testing in various formats |

|

X |

Many participants expressed a desire for increased communication around potential exposure occurrences or identified past positive cases at their schools. Participants noted the difficulty of contact tracing during the 2021–2022 school year, as the process was perceived as less rigorous compared to the 2020–2021 school year. Many participants cited often-changing SSD COVID-19 policies protocols as a significant stressor. Feelings of frustration increased when school staff and families perceived those protocols to be inconsistently enforced, particularly when schools did not shift back to virtual learning after the Omicron surge. Parents and school staff found some policies regarding quarantine guidelines to be confusing or contradictory. Contact tracing was often cited as inconsistent with notifications and/or instructions.

School Experience [Table 3]

Table 3:

Impact of COVID-19 and Vaccination on School Experience

| Theme | Illustrative Quote | Parents | Staff |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pandemic illuminated need for support of the social and emotional well-being of staff and students |

|

X | |

| In-person learning much preferred over virtual learning |

|

X | X |

| Concern of staff shortages impacting education |

|

X | X |

| Despite preference for in-person, school needs to make contingency plans for returning to virtual |

|

X | X |

| Concerns about vaccines due to side effects, development, or misinformation |

|

X | X |

| Unlikely to discuss with peers due to politicized nature of COVID and vaccinations |

|

X | |

| More comfortable with in-person learning after students and staff were vaccinated |

|

X | X |

With the pandemic still evolving throughout the 2021–2022 school year, risk of transmission of COVID-19 remained top of mind for many, especially for families with medically fragile students or other high-risk individuals in the home.25 However, many shared that the 2021–2022 school year was better than the 2020–2021 school year, as in-person learning was preferred by most students, parents, and school staff. As one parent shared, “For me, for my son, this school year has been going great. When we went out of school in 2020, it was not great because he did not like virtual. He got up and did his assignments, and he signed in when he was supposed to, but I can tell that it was really hard for him not being able to be there with his teachers and his classmates in-person.” Most felt a return to a sense of normalcy during the fall semester of 2021, followed by a period of stress when the Omicron variant surged in the community in January 2022.26 Many students and school staff missed school due to quarantine protocols, with no option to attend school virtually during the 2021–2022 school year. Protocols were often-changing because of shifting public health guidelines as vaccines became more widely available across various age groups.27

COVID-19 Testing [Table 2]

Focus group participants shared facilitators and barriers to participation in the weekly SARS-CoV-2 screening testing at SSD.

Facilitators.

Parents and school staff shared factors that increased their interest in participating in weekly saliva-based SARS-CoV-2 testing at SSD. Most who participated in testing did so because it provided peace of mind, especially when positive cases were detected in those who were asymptomatic and when those who experienced symptoms consistent with COVID-19 received negative results. Testing greatly increased comfort with returning to school in-person; school staff in particular felt comforted because many of their students were not eligible for vaccination at the beginning of the school year.28 Many participants identified the convenience of testing as a significant facilitator to testing uptake, both because of the location and because of the reliability of accessing testing when there were limited tests available in the community during December and January of 2021–2022.29 As one staff member mentioned, “People are having trouble getting COVID tests these days and, oh my gosh, we have it coming to our work, in [our] place of employment and we don’t even have to drive anywhere.” Finally, those who had participated in regular testing noted the trusting relationships they had developed with the testing team, and commended the adaptability of the team in accommodating students with IDD and their unique needs. This included changing testing locations as preferred by students, conducting home visits to collect samples, and using sponges, pipettes, and other implements to extract saliva from students for whom it was difficult to provide saliva samples. One caregiver complimented the team by sharing, “[The testing coordinator] made me feel so comfortable, she was down to earth. She was very knowledgeable and… I think that she really cared about my grandson and I.”

Barriers.

Some ongoing challenges and considerations for testing remained since the first time point of data collection, including mistrust of the testing method and disinterest in research participation.10 One additional barrier identified during this round of focus groups was the perception that testing was unnecessary if an individual was fully vaccinated or asymptomatic. Others expressed that they did not trust the saliva-based method of testing, as they perceived that this methodology was discussed less frequently by the general public compared to the nasal PCR test, and was therefore regarded as less reliable. Similarly, some focus group participants shared they were not interested in participating in SARS-CoV-2 testing because it was affiliated with a research study.

COVID-19 Vaccination [Table 3]

Some participants experienced increased comfort with returning to in-person learning after they or their students were vaccinated. However, this comfort was not shared by all. Uncertainty of the vaccination status of others still concerned some, especially when they felt uncomfortable talking about COVID-19 or vaccination status with their peers. One parent shared their concerns: “I mean, you don’t know, even with the increased access [to COVID-19 vaccines], you don’t know who has it and doesn’t have it anyway.” Of those who were vaccine hesitant, the top concerns included: unknown short- and long-term side effects; distrust of how quickly the mRNA vaccines were developed; and not knowing what was in the vaccines. Several participants cited challenges with vaccines that are contrary to scientific evidence (e.g., vaccines cause autism, vaccines will turn you into a zombie, and vaccine components lead to death).

Participants were more confident in using other mitigation strategies (testing, masking) to prevent or reduce transmission of COVID-19. There were mixed opinions around the potential for vaccine mandates in the school community. Many participants supported and/or pursued COVID-19 vaccination for themselves; despite their personal views on vaccination, most felt vaccination should be an individual choice. Some were supportive of vaccine mandates, often citing other vaccination requirements for school attendance.30

Unique Themes Across Stakeholder Groups

Parents.

Some themes were unique to parents, including lack of interest in or lack of awareness of weekly screening testing, as well as the social-emotional impact of the pandemic and an avoidance of COVID-19 discussions in their social circles. Some parents did not want their students to participate in weekly SARS-CoV-2 testing, in order to avoid missing days of school due to quarantine if they were to test positive. This theme aligns with staff experiences that many parents would send their students to school while sick. Some parents also shared they did not feel testing was necessary once their student was vaccinated, or if their student was asymptomatic. Interestingly, parents were also unlikely to discuss COVID-19 or vaccinations with their peers due to how politicized those conversations have become. At the same time, parents noted that the pandemic illuminated the need to have better support for the overall well-being of both school staff and students.

School Staff.

School staff were unique from parents in two ways: they experienced more challenges with school- or district-level policies, and they were much more likely to be aware of the weekly SARS-CoV-2 testing in their schools. One particular concern was about the lack of contact tracing for staff who moved between classrooms and campuses, putting both themselves and their students at risk. Those who moved between classrooms were often staff and not classroom teachers, in roles such as occupational or speech therapists, librarians, or counselors. In addition, school staff conveyed awareness of and participation in weekly screening testing at their schools, compared to many parents whose children did not participate. This supports weekly testing participation data, which shows that 84% of weekly testing participants were school staff and 16% were students.

DISCUSSION

We found that weekly screening testing provided comfort for both parents and school staff in supporting IDD students to attend in-person school.17 This peace of mind continued to be a significant finding across both time points of data collection, showing that the SSD community valued weekly screening testing despite the availability of vaccines. Since the first time point, much has changed as the pandemic evolved, including the addition of vaccination and treatment for COVID-19, district-level COVID-19 policies, and the SSD community’s experiences.31,32 At the second time point, vaccines were widely available for most people ages 12 and up, which had a significant impact on comfort levels with in-person learning.33 In-person school was much preferred over virtual or hybrid learning by all stakeholder groups. However, parents and school staff were frustrated that there was no virtual option for the 2021–2022 school year and wanted there to be contingency plans in case community rates increased. This was made clear during the Omicron surge in January 2022, when many students and staff had to quarantine due to exposure or positivity. The lack of virtual options can be attributed to the state of Missouri’s Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (DESE) policies around alternative methods of instruction (AMI) days, which were limited to five for the school year; this encompassed both days for inclement weather as well as pandemic-related closures.34 Another district-level policy frequently mentioned by school staff in the second time point was contact tracing; this process was much more challenging compared to time point 1, as students and staff were able to move about the school freely instead of in pods, and the procedures for contact tracing were more lenient. Many participants shared that these changing factors contributed to the importance of weekly screening testing for themselves and the SSD community.

Findings from this qualitative data assert that an added benefit for testing participants is an increased peace of mind to be able to attend school in person, which remains true since time point 1.35 For those who participated in testing, they described successful sample collection and gratitude for the trusting relationships they had developed with the test team over the course of the 2021–2022 school year. One important finding from this round of data collection was the continued need for consistent messaging to promote both the opportunity to participate in testing, as well as the efficacy of the saliva-based PCR test.36 One potential reason for a lack of consistency could be that this study was external to the district and was part of a research study through Washington University in St. Louis, as opposed to being district-driven. Increased familiarity with the methodology and additional messages from the school district, along with a more district-driven approach, would likely have increased participation in weekly testing.

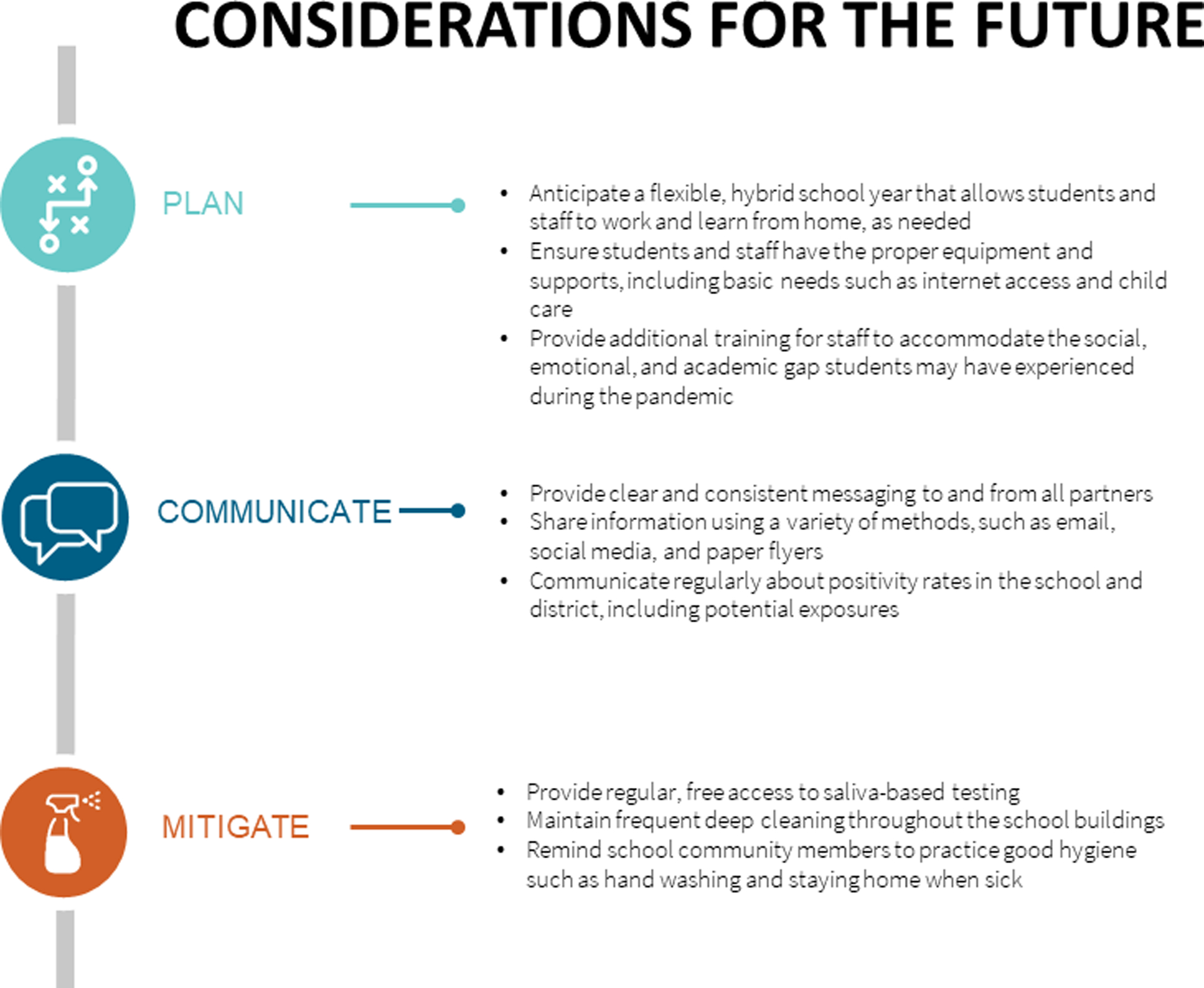

IMPLICACTIONS FOR SCHOOL HEALTH POLICY, PRACTICE, AND EQUITY [Figure 1]

Figure 1.

Considerations for future weekly testing

As one parent shared, “COVID is not going away anytime soon, and we have to make that the norm for our children.” To best meet the needs of school staff, students, and families, focus group participants identified the below strategies to support students with special needs throughout the pandemic.

Plan.

While school districts are limited by their state’s regulations on the number of AMI days, the majority of focus group participants advocated for their schools to anticipate a flexible, hybrid school year that would allow students and school staff to work and learn from home as needed. Participants also recommended that schools ensure students and staff have the proper equipment and supports, including basic needs such as Internet access and child care. Additionally, regardless of if virtual or in-person, participants recommended that schools provide additional training to staff to accommodate the social, emotional, and academic gaps students may have experienced as a result of the pandemic and its broader cultural landscape.

Communicate.

Regular, honest communication from school leadership was a primary facilitator for both parents and school staff to feel supported by their school. School administrators should provide clear and consistent messaging to all their families, staff, and key stakeholders. Sharing the same information using a variety of methods, such as email, social media, and paper flyers, will significantly increase exposure. The latest information regarding COVID-19 in each school should be communicated regularly, including positivity rates within the school and district, as well as potential exposures identified through contact tracing.

Mitigate.

As the pandemic continues, focus group participants highly encouraged the continued access to free, weekly, saliva-based SARS-CoV-2 testing. They also found it important to maintain frequent deep cleaning schedules throughout the school buildings and provide cleaning products to school staff as needed. Deep cleaning increased perceptions of hygiene and therefore increased comfort, though consideration must be given to the associated costs of these cleaning measures. Also, it is helpful to reiterate reminders to school community members about general public health recommendations such as staying home when sick and routinely washing hands.

LIMITATIONS

There are a number of potential limitations. The study team utilized a convenience sample; participation was voluntary and only parents and school staff were eligible. The primary study purpose was to speak to those identifying and implementing the mitigation strategies and policies/procedures in the schools. We did not speak to students, and their perspective is notably missing. Further research is needed to understand the particular experiences of students with IDD. Given that there was no control group, we are also unable to ascertain the perceived benefit of COVID-19 testing for SSD parents and staff compared to parents and staff in other school districts who might have been obtaining frequent testing through other mechanisms.

CONCLUSION

As the pandemic continued into the 2021–2022 school year, students with IDD, their families, and the school staff who support them navigated new challenges and opportunities as most returned to in-person learning. Despite the increased availability of vaccines, many families and school staff with whom we spoke believed that weekly SARS-CoV-2 screening testing remained a critical mitigation effort to prevent transmission in the school setting. Access to regular, saliva-based testing provided peace of mind, even as most age groups become eligible to receive vaccinations. School policies and mitigation strategies will remain an important factor contributing to school staff and families’ comfort and stress while continuing to attend in-person school as long as COVID is present in our communities.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the following members from the Brown School Evaluation Center who contributed to the data collection and analysis activities: Hannah Allee, Rachel Barth, Courtney Cantwell, Meihsi Chiang, Heather Jacobsen, Missy Krauss, Emily Laurent, and Zoey Dlott.

The COMPASS-T project is a joint partnership between the Washington University in St. Louis Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center (WUIDDRC), the University of Missouri-Kansas City Institute of Human Development, the Kennedy Krieger Institute in Maryland, and the Special School District of St. Louis County (SSD) in Missouri. Other key collaborators include the Brown School Evaluation Center, Health Communication Research Laboratory, and the Institute for Informatics at Washington University. This work is supported by the National Institutes of Health through the Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics - Underserved Populations (RADx-UP) Program (P50HD103525-01S1).

Footnotes

This study is registered at http://clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT04565509

HUMAN SUBJECTS APPROVAL STATEMENT

This study was approved by the Washington University in St. Louis Institutional Review Board (IRB) and individuals provided consent prior to participation. Prior to enrollment, this study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov on 9/25/2020, identifier NCT04565509, titled Supporting the Health and Well-being of Children with Intellectual and Developmental Disability During COVID-19 Pandemic. (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04565509?term=NCT04565509).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors have no competing interests relevant to this manuscript to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zimmerman K, Akinboyo I, Brookhart M, Boutzoukas A. Incidence and Secondary Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 Infections in Schools. Pediatrics. 2021;147(4). doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-048090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dawson P, Worrell MC, Malone S, et al. Pilot Investigation of SARS-CoV-2 Secondary Transmission in Kindergarten Through Grade 12 Schools Implementing Mitigation Strategies -- St. Louis County and City of Springfield, Missouri, December 2020. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(12):449–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gleason J, Ross W, Fossi A, Blonsky H, Tobias J, Stephens M. The Devastating Impact of COVID 19 on Individuals with Intellectual Disabilities in the United States. NEJM Catal Innov Care Deliv. 2021;2(3). doi: 10.1056/CAT.21.0051 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stevens D, Landes SD. Potential Impacts of COVID-19 on Individuals with Intellectual and Developmental Disability: A Call for Accurate Cause of Death Reporting. :3. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garbe A, ogurlu U, Logan N, Cook P. Parents’ Experiences with Remote Education during COVID-19 School Closures. Am J Qual Res. 2020;4(3). doi: 10.29333/ajqr/8471 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sherby MR, Kalb LG, Coller RJ, DeMuri GP. Supporting COVID-19 School Safety for Children with Disabilities and Medical Complexity. Pediatrics. 2022;149(Supplement_2). doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-054268H [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Institutes of Health. RADx Programs. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Published 2022. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://www.nih.gov/research-training/medical-research-initiatives/radx/radx-programs#radx-up

- 8.Heavey L, Casey G, Kelly D, McDarby G. No evidence of secondary transmission of COVID-19 from children attending school in Ireland, 2020. Eurosurveillance. 25(21). doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.21.2000903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lewis D Why schools probably aren’t COVID hotspots. Nature. 2020;587(17). doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-02973-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vestal LE, Schmidt AM, Lobb Dougherty N, Sherby MR, Newland JG, Mueller NM. COVID-19 Related Facilitators and Barriers to In-Person Learning for Children with Intellectual and Development Disabilities. J Sch Health. Published online November 20, 2022. doi:doi: 10.1111/josh.13262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Missouri Department of Elementary and Secondary Education. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Information: Archived Information. DESE COVID-19 Updates. Accessed November 18, 2022. https://dese.mo.gov/communications/coronavirus-covid-19-information-archived-information [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haroz EE, Kalb LG, Newland JG, Goldman JL. Implementation of School-Based COVID-19 Testing Programs in Underserved Populations. Pediatrics. 2022;1(149). doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-054268G [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vohra D, Rowan P, Hotchkiss J, Lim K, Lansdale A, O’Neil S. Implementing COVID-19 Routine Testing in K-12 Schools: Lessons and Recommendations from Pilot Sites. Mathematica; 2021:2–25. https://www.mathematica.org/news/implementing-routine-covid-19-testing-in-schools-can-significantly-reduce-and-in-some-cases?utm_source=acoustic&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=&utm_content=Rockefeller%20Routine%20Testing%20072621%20(1) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mendoza R, Bi CHT, Gabutan E, Pagaspas G. Implementation of a pooled surveillance testing program for asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections in K-12 schools and universities. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;2021(38):10208. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lanier W, Babitz K, Collingwood A. COVID-19 Testing to Sustain In-Person Instruction and Extracurricular Activities in High Schools — Utah, November 2020–March 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(21):785–791. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7021e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.AJMC. A Timeline of COVID-19 Vaccine Developments in 2021. AJMC. Published June 3, 2021. Accessed July 7, 2022. https://www.ajmc.com/view/a-timeline-of-covid-19-vaccine-developments-in-2021 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sherby MR, Walsh T, Lai A, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Screening Testing in Schools for Children with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. J Neurodev Disord. Published online July 21, 2021:1–22. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-700296/v1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zoom. Security Guide. Zoom Video Communications, Inc.; 2021:1–9. Accessed April 4, 2022. https://explore.zoom.us/docs/doc/Zoom-Security-White-Paper.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(4):1758–1772. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.QSR International Pty Ltd. NVivo. Published 2020. https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home

- 22.Cohen J. A Coefficient of Agreement for Nominal Scales. Educ Psychol Meas. 1960;20(1):37–46. doi: 10.1177/001316446002000104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chapman A, Hadfield M, Chapman C. Qualitative research in healthcare: An introduction to grounded theory using thematic analysis. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2015;45(3):201–205. doi: 10.4997/jrcpe.2015.305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chun Tie Y, Birks M, Francis K. Grounded theory research: A design framework for novice researchers. SAGE Open Med. 2019;7:205031211882292. doi: 10.1177/2050312118822927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hayes S, Malone S, Bonty B, Mueller N, Reyes S, Reyes S. Assessing COVID-19 testing strategies in K-12 schools in underserved populations: Study protocol for a cluster-randomized trial. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-13577-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bernhard B. Missouri school districts struggle to keep classrooms open during COVID-19 surge. St. Louis Post-Dispatch. https://www.stltoday.com/news/local/education/missouri-school-districts-struggle-to-keep-classrooms-open-during-covid-19-surge/article_a7e030ee-b543-5775-ba2e-72cd70c75239.html. Published January 6, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patel MK, Bergeri I, Bresee J, Cowling B, Crowcroft N, Fahmy K. Evaluation of post-introduction COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness: Summary of interim guidance of the World Health Organization. Vaccine. 2021;39(30):4013–4024. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.05.099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Diesel J, Sterrett N, Dasgupta S, Kriss J, Barry V, Vanden Esschert K. COVID-19 Vaccination Coverage - United States, December 14 2020 - May 22, 2021. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021. 2021;70(25):922–927. doi:doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7025e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Flamroussi A. Finding a COVID-19 test is a struggle right now in the US as Omicron and holiday plans collide. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2021/12/22/health/us-coronavirus-wednesday/index.html. Published December 3, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rules of Department of Health and Human Services: Division 20 - Division of Community and Public Health, Chapter 28 - Immunization. Published online September 30, 2015. Accessed November 18, 2022. https://www.sos.mo.gov/cmsimages/adrules/csr/current/19csr/19c20-28.pdf

- 31.Special School District of Saint Louis County. SSD Safe Return to In Person Learning Plan. Published online July 12, 2022. Accessed November 17, 2022. https://www.ssdmo.org/site/handlers/filedownload.ashx?moduleinstanceid=3811&dataid=282354&FileName=Safe%20Return%20to%20In-Person%20Learning%20Plan%20Rev%20July%202022.pdf

- 32.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Museum COVID 19 Timeline. CDC. Published August 16, 2022. Accessed November 17, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/museum/timeline/covid19.html [Google Scholar]

- 33.BJC Healthcare. Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine now approved for children ages 12–15. COVID-19 Vaccines Articles. Published May 13, 2021. Accessed November 17, 2022. https://www.bjc.org/Coronavirus/COVID-19-Vaccines/COVID-19-Vaccines-Articles/ArtMID/6435/ArticleID/4743/Pfizer-COVID-19-vaccine-now-approved-for-children-ages-12-15 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alternative Methods of Instruction (AMI) Plans. Missouri Department of Elementary and Seconday Education. Published April 4, 2022. https://dese.mo.gov/alternative-methods-instruction-ami-plans-0

- 35.Vestal LE, Schmidt AM, Lobb Dougherty N, Sherby MR, Newland JG, Mueller NB. COVID-19 Related Facilitators and Barriers to In-Person Learning for Children with Intellectual and Development Disabilities. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Fluidigm. Advanta Dx SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR Assay. Standard Biotools Inc. Accessed November 17, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/media/141541/download [Google Scholar]