Abstract

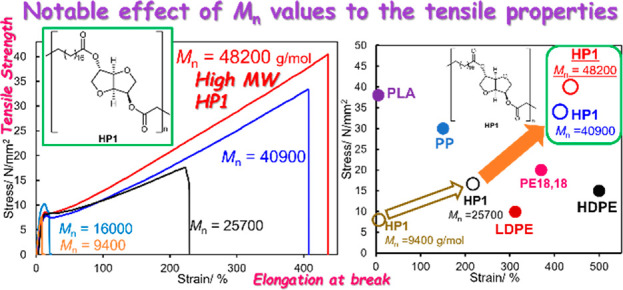

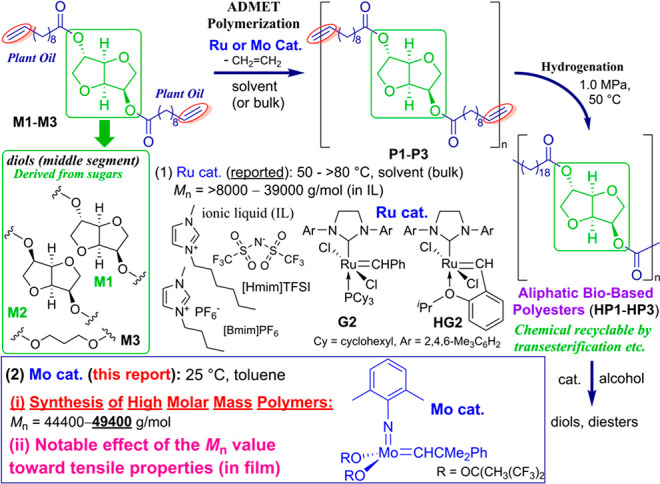

Synthesis of high molecular weight polyesters prepared by acyclic diene metathesis (ADMET) polymerization of bis(undec-10-enoate) with isosorbide (M1), isomannide (M2), and 1,3-propanediol (M3) and the subsequent hydrogenation have been achieved by using a molybdenum-alkylidene catalyst. The resultant polymers (P1) prepared by the ADMET polymerization of M1 (in toluene at 25 °C) possessed high Mn values (Mn = 44400–49400 g/mol), and no significant differences in the Mn values and the PDI (Mw/Mn) values were observed in the samples after the hydrogenation. Both the tensile strength and the elongation at break in the hydrogenated polymers from M1 (HP1) increased upon increasing the molar mass, and the sample with an Mn value of 48200 exhibited better tensile properties (tensile strength of 39.7 MPa, elongation at break of 436%) than conventional polyethylene, polypropylene, as well as polyester containing C18 alkyl chains. The tensile properties were affected by the diol segment employed, whereas HP2 showed a similar property to HP1.

Aliphatic polyesters derived from plant resources are attracting considerable attention1−8 not only as an alternative of petroleum-based polymers but also in terms of their circular economy9−11 due to rather facile chemical recycling by the depolymerization (through transesterification, etc.)12−15 compared to conventional polyolefins. These polyesters would also provide a possibility as new promising materials with better mechanical properties through interpolymer interactions as well as better compatibility with biobased fibers (described below). An olefin metathesis route consisting of acyclic diene metathesis (ADMET) polymerization16−19 and the subsequent hydrogenation (Scheme 1) have been considered as the synthetic route due to the wide polymer scope (especially the polymer main chain, called the middle segment in Scheme 1) in addition to the condensation–polymerization route.7 In spite of the number of reports by ADMET polymerization in the presence of ruthenium-carbene catalysts,15,20−34 however, synthesis of the high molecular weight polymers still seems to be difficult.35 Two studies28,34 reported the synthesis of the high molar mass polyesters under bulk conditions (80–90 °C, G2, 16–20 h). However, polymerization at such high temperature led to catalyst decomposition which not only causes isomerization and undesired side reactions by formed radicals (metal particles)15,21,24 but also causes the separation of metals from the resultant polymers to be difficult. The method also faces the difficulty of stirring due to high viscosity.15

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Aliphatic Polyesters by Acyclic Diene Metathesis (ADMET) Polymerization.

Recently, the polymerization of M1 and M2 conducted in ionic liquid (IL, no vapor pressure) with continuous removal of ethylene byproduced afforded polymers with Mn value higher than 30000 (Scheme 1),15 whereas the polymerization conducted in toluene or CHCl3 (even under optimized conditions with careful removal of ethylene) afforded polymers of Mn values up to 15000.21,32 We thus herein communicate that the synthesis of high molar mass polymers (Mn = 44000–49400 g/mol), which exhibit better tensile properties than conventional polyethylene, has been achieved by using the molybdenum-alkylidene catalyst, Mo(CHCMe2Ph)(2,6-Me2C6H3)[OC(CH3)(CF3)2] (Mo cat.), even in toluene at 25 °C.36

Table 1 summarizes the selected results for ADMET polymerization of M1–M3 in toluene (at 25 °C) in the presence of the molybdenum-alkylidene catalyst (Mo cat.). Three monomers (M1–M3) have been chosen in this study because these are easily available from castor oil (undecenoate) and sugars (isosorbide, isomannide, and 1,3-propanediol). The Mo catalyst has been chosen because the catalyst showed unique characteristics especially for the synthesis of poly(9,9′-dialkyl-fluorene-2,7-vinylene)s in the ADMET polymerization.37,38 The experimental details and the additional polymerization results and selected NMR spectra for the identifications are shown in the Supporting Information (SI).

Table 1. ADMET Polymerization of M1–M3a.

| runa | monomer (μmol) | cat. | cat./mol % | solvent (mL) | temp/°C | time/h | yieldb/% | Mnc/g·mol–1 | Mw/Mnc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1d | M1 (90.5) | Mo | 5.0 | toluene (0.72) | 25 | 6 | 99 | 16000 | 1.79 |

| 2d | M1 (90.5) | Mo | 5.0 | toluene (0.72) | 25 | 8 | 91 | 20800 | 1.73 |

| 3 | M1 (90.5) | Mo | 2.5 | toluene (0.72) | 25 | 6 | 90 | 25100 | 1.43 |

| 4d | M1 (90.5) | Mo | 1.0 | toluene (0.72) | 25 | 6 | 88 | 34400 | 1.49 |

| 5 | M1 (90.5) | Mo | 1.0 | toluene (0.72) | 25 | 6 | 84 | 31100 | 1.89 |

| 6 | M1 (272) | Mo | 1.0 | toluene (0.72) | 25 | 6 | 88 | 46100 | 2.08 |

| 7d | M1 (272) | Mo | 1.0 | toluene (0.72) | 25 | 6 | 91 | 46100 | 1.84 |

| 8 | M1 (272) | Mo | 0.5 | toluene (0.72) | 25 | 3 | 93 | 22600 | 1.93 |

| 9 | M1 (272) | Mo | 0.5 | toluene (0.72) | 25 | 6 | 90 | 48700 | 2.04 |

| 10 | M1 (272) | Mo | 0.5 | toluene (0.72) | 25 | 6 | 84 | 47500 | 1.78 |

| 11 | M1 (543) | Mo | 0.5 | toluene (1.0) | 25 | 6 | 90 | 44500 | 2.23 |

| 12 | M1 (543) | Mo | 0.5 | toluene (1.0) | 25 | 6 | 95 | 44400 | 1.92 |

| 13 | M1 (543) | Mo | 0.5 | toluene (1.0) | 25 | 6 | 91 | 49400 | 2.47 |

| 14e | M2 (272) | Mo | 1.0 | toluene (0.72) | 25 | 6 | 87 | 34800 | 1.87 |

| 15 | M3 (272) | Mo | 1.0 | toluene (0.72) | 25 | 6 | 99 | 67200 | 2.27 |

| 16 | M1 (624) | HG2 | 1.0 | toluene (0.14) | 50 | 5 | 71 | 7100 | 1.58 |

| 17 | M1 (624) | HG2 | 1.0 | toluene (0.14) | 50 | 12 | 86 | 8700 | 1.39 |

| 18 | M1 (624) | HG2 | 1.0 | toluene (0.14) | 50 | 24 | 88 | 14000 | 1.42 |

| 19f | M1 (624) | HG2 | 1.0 | CHCl3 (0.14) | 50 | 24 | 88 | 11000 | 1.21 |

| 20g | M1 (624) | HG2 | 1.0 | [Bmim]PF6 (0.14) | 50 | 16 | 89 | 32200 | 1.87 |

| 21g | M1 (624) | HG2 | 1.0 | [Hmim]TFSI (0.14) | 50 | 16 | 93 | 39200 | 1.95 |

| 22g | M2 (624) | HG2 | 1.0 | [Hmim]TFSI (0.14) | 50 | 16 | 92 | 26000 | 1.95 |

Conditions: (runs 1–15) Mo(CHCMe2Ph)(N-2,6-Me2C6H3)[OC(CH3)(CF3)2]2 (Mo), toluene 0.72 or 1.0 mL, 25 °C, quenched by benzaldehyde (for termination through Wittig-type cleavage37,38) and (runs 16–18) HG2, toluene 0.14 mL, 50 °C (optimized conditions in ref (31)).

Isolated yield (as MeOH insoluble fraction).

GPC data in THF (at 40 °C) vs polystyrene standards.

4-Me3SiOC6H3CHO (runs 1, 24) or ferrocenecarboxaldehyde (run 7) was used instead of benzaldehyde.

Ethylene removal every 5 min (instead of 10 min) at the initial 30 min, see SI.

Cited from ref (31).

Cited from ref (15). RuCl2(IMesH2)(CH-2-OiPr-C6H4) [HG2; IMesH2 = 1,3-bis(2,4,6-trimethylphenyl) imidazolin-2-ylidene, Cy = cyclohexyl]. [Bmim]PF6: 1-n-butyl-3-methyl imidazolium hexafluorophosphate; [Hmim]TFSI: 1-n-hexyl-3-methyl imidazolium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl) imide.

It was revealed that the Mn value in the resultant polymer, expressed as P1, increased with a decrease in the amount of the Mo catalyst loaded [ex. Mn = 9500 g/mol (Mo 10 mol %, run S1 in Table S1, SI) < 16000 (5.0 mol %, run 1) < 31100 (run 5), 34400 (run 4, Mo 1.0 mol %); M1 90.5 μmol scale], whereas the Mn value was also affected by the time course (4–8 h, runs 1, 2, and S2). Note that the Mn values further increased when the polymerizations were conducted under rather high initial monomer concentration (rather a large reaction, M1 0.272 mmol scale) conditions [Mn = 46100 (runs 6 and 7, [M1]0 = 0.38 mmol/mL; [M1]0 = initial M1 concentration) vs 31100 (run 5, [M1]0 = 0.13 mmol/mL)], and the results are reproducible even terminated with different aldehydes (through Wittig-type cleavage between metal–alkylidene species with aldehyde,37,38 runs 6 and 7). Also note that the Mn values reached 47500–48700 g/mol when the polymerizations were conducted under low Mo loading (0.5 mol %), and the results were reproducible (runs 9, 10, and S4). The polymerizations of M1 under increased reaction scale (M1 0.543 mmol in 1.0 mL of toluene) also afforded high molar mass P1 (Mn = 49400, run 13), as reported previously,15−19,30,31,33 and careful removal of byproduced ethylene (especially at the beginning) is a prerequisite for the synthesis of high molar mass polymers in this condensation–polymerization (runs 11–12 and S6–8), probably due to increased viscosity under these rather high initial M1 concentration conditions (as demonstrated previously).15

Similarly, the Mn values in the resultant polymers from M2 (expressed as P2, Mn = 32200–36700, runs 14, S9, and S10) were higher than those prepared by the ruthenium catalyst in IL (Mn = 26000, run 22).15 The Mn values in P3 (Mn = 59900–67200, runs 15, S12, and S13) and polymers from bis(undec-10-enoate) with 1,3-propanediol (M3) were higher than those in P1 and P2. In contrast, the polymerizations of M1 by ruthenium catalysts (HG2, G2, shown in Scheme 1) in toluene (conducted under the same procedure) or CHCl331 afforded polymers with low Mn values (runs 16–19 and S14–S18), whereas improvements in the Mn values were seen when the reactions were conducted in IL (runs 20, 21, and S19). The results thus indicate that the molybdenum catalyst is effective for the synthesis of high molar mass polymers (even under rather simple reaction conditions compared with those conducted in IL).

The resultant polymers (P1–P2) were hydrogenated in the presence of RhCl(PPh3)3 in toluene (H2 1.0 MPa, 50 °C) according to a reported procedure for hydrogenation of ethylene/conjugated diene copolymers, poly(ethylene-co-isoprene)s39 and poly(ethylene-co-myrcene)s.40 As summarized in Table S2, no significant changes in the Mn values and the Mw/Mn values were observed in all cases; the resultant polymers (expressed as HP1 and HP2) were identified by NMR spectra (selected NMR spectra, GPC traces are shown in the SI).

Tensile property tests (stress/strain experiments) for the resultant hydrogenated polymers were conducted by using a universal testing instrument with an elongation rate of 10 mm/min (23 °C, humidity 50 ± 10%). The small dumbbell-shaped test specimens were prepared by cutting the polymer sheet (prepared by a hot press, the detailed procedures are described in SI),37 and at least three specimens of each polymer were tested (additional data are shown in SI). Samples (P1, HP1) of different (rather low) Mn values were prepared by using ruthenium catalysts,15,31 and the details are shown in Table S2. The polymer sheets prepared by the hot press method were chosen because these samples showed better tensile properties than those prepared through solvent cast methods (detailed comparisons are shown in the SI).41

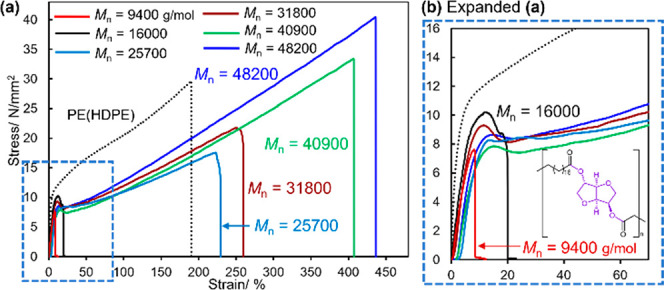

Figure 1 summarizes the results for the effect of molecular weight on the tensile properties, and the additional results are shown in Figure S28. The results for tensile properties are summarized in Table 2. It should be noted that a rather significant increase in both tensile strength (stress) and the elongation at break (strain) were observed upon increasing the Mnvalues ofHP1. In particular, HP1 with the highest Mn value (Mn = 48200, hydrogenated sample of P1, run 13) exhibited a tensile strength of 39.7 MPa along with the elongation at break of 436%; a fairly good linear relationship between the tensile strength and the elongation at break was observed (in HP1 of Mn values higher than 25700, Figure S26).37 The value is indeed higher than a sample of high molar mass linear polyethylene (HDPE, Mn = 1.86 × 106, Mw/Mn = 3.44; tensile strength 30 MPa, elongation at break 180%) prepared for comparison.

Figure 1.

(a) Effect of molecular weight (Mn value) on the tensile properties in HP1 (speed 10 mm/min, hot press film). (b) Expanded view of Figure 1(a). Data after hydrogenation for the preparation of the samples are shown in Table S2, SI. PE (polyethylene): Mn = 1.86 × 106 g/mol, Mw/Mn = 3.44 (see SI for synthesis).

Table 2. Summary of the Tensile Properties of Polyestersa.

| sample | Mnb/g·mol–1 | Mw/Mnb | tensile strength/MPa | elongation at break/% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HP1 | 9400 | 1.61 | 6.2(±1.3) | 8.0(±1.3) |

| HP1 | 25700 | 2.16 | 16.8(±1.8) | 217(±35) |

| HP1 | 31800 | 2.23 | 20.6(±1.1) | 245(±14) |

| HP1 | 40900 | 2.41 | 33.7(±2.2) | 413(±13) |

| HP1 | 48200 | 2.56 | 39.7(±2.6) | 436(±24) |

| HP2 | 23300 | 2.17 | 16.7(±0.7) | 229(±22) |

| HP4 | 28700 | 3.42 | 8.79(±0.4) | 165(±15) |

| P1 | 39600 | 1.89 | 18.17(±1.1) | 513(±58) |

| P1 | 44500 | 2.23 | 19.85(±0.7) | 507(±11) |

| P2 | 35900 | 1.52 | 15.14(±4.3) | 535(±49) |

| P3 | 62200 | 2.36 | 13.99(±0.9) | 251(±26) |

Details in stress/strain experiments including the sample preparations are described in SI.

GPC data in THF (at 40 °C) vs polystyrene standards.

It was revealed that HP2 showed similar tensile property to HP1 (Figure S27), whereas the hydrogenated polymer sample prepared by ADMET polymerization of bis(undec-10-enoate) with 1,4-cyclohexanedimethanol (expressed as HP4, Figure S27)15 was inferior to tensile strength and the elongation at break. Stress–strain curves for polymer samples before hydrogenation (P1–P3) are shown in Figure 2. P2 showed similar tensile property to that in P1, and P3 was inferior to elongation at break. The results suggest that the tensile properties are affected by the diol segment employed, and the polymer samples derived from isosorbide and isomannide showed better properties. It was revealed that elongation at breaks in both P1 and P2 samples before hydrogenation are apparently larger than those in HP1 and HP2, whereas HP1 and HP2 showed higher levels of tensile strengths compared to P1 and P2. Moreover, no significant differences in tensile strength and the elongation at break were observed in P1 with Mn values of 39600 and 44500, whereas the values were apparently low in the rather low molar mass sample [Mn = 28300, Mw/Mn = 1.75, prepared by HG2 in IL, 1.0 g scale in 0.3 mL of [Hmim]TFSI, 1.0 mol % of HG2, 50 °C, 6 h].15

Figure 2.

Tensile properties in P1–P3 (samples before hydrogenation, speed 10 mm/min, hot press film).

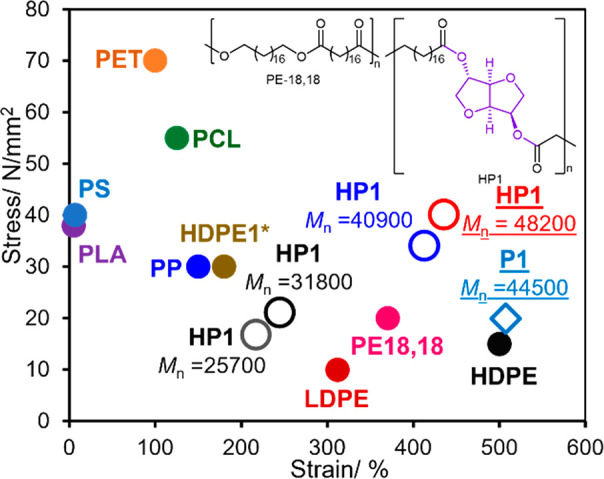

Figure 3 shows plots of HP1 with different Mn values, and plots of PE-18,18, prepared from C18 dimethyl dicarboxylate and the corresponding diol by a condensation–polymerization with Ti(OiPr)4,10 commercially available samples including poly(ethylene terephthalate) (PET),42 high density polyethylene (HDPE),10,42 low density polyethylene (LDPE),42 polypropylene (PP),42 etc., are also shown for comparison.10,42 It is clear that the high molecular weight of HP1, presented in this communication, possesses higher tensile strength (stress) than the other polymer samples such as PP and PEs, whereas both the tensile strength and the elongation at break are affected by the Mn value. As described above, the sample before hydrogenation showed higher strain (elongation at break) with less stress (tensile strength), which is close to that of conventional HDPE.

Figure 3.

Plots of tensile (fracture) strengths and strains (elongation at breaks) of HP1 with different Mn values. The plots of PE-18,18 (polyester-18,18),10 commercially available polyethylene terephthalate (PET), poly(lactic acid) (PLA), poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL), high-density polyethylene (HDPE), low-density polyethylene (LDPE), polypropylene (PP), and polystyrene (PS).42 HDPE1* is a high molecular weight polyethylene sample (Mn = 1.86 × 106, Mw/Mn = 3.44) prepared in this study.

We have communicated a successful synthesis of high molar mass polyesters (HP1–HP3, ex. Mn = 48200) derived from plant resources, which exhibit tensile properties beyond conventional polyethylene and polypropylene (LDPE, HDPE, PP), prepared by ADMET polymerization using the molybdenum-alkylidene catalyst (in toluene at 25 °C). The effect of molecular weight on the tensile property in HP1 has been demonstrated.43 The results here should introduce a promising possibility of chemical recyclable15 biobased aliphatic polyesters not only as alternatives of conventional polyolefins but also as functional polymers suited to circular economy. Moreover, the mechanical property of HP1 was improved by the preparation of a composite with a small amount of cellulose nanofiber (CNF),42 whereas such an effect was not observed when the polyester containing a linear C9 alkyl was employed.36 More details including crystallinity (small-angle light scattering, SAXS analysis, etc.),43 the preparation of soluble network polymers that improve elongation breaks,36 and the fabrication with additives (CNF etc.)36,41 will be introduced in the near future.

Acknowledgments

This project was partly supported by JST-CREST (Grant Number JPMJCR21L5), JST SICORP (Grant Number JPMJSC19E2), Japan, and Tokyo Metropolitan Government Advanced Research (Grant Number R2-1). K.N. and H.H. express their thanks to Prof. Hiroki Takeshita (The University of Shiga Prefecture) for fruitful discussions. X.W. thanks the Tokyo Metropolitan government (Tokyo Human Resources Fund for City Diplomacy) for a predoctoral fellowship. L.G. also expresses his thanks to a MEXT (Japanese government, Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology) fellowship for his predoctoral study.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmacrolett.3c00481.

(i) General procedure, synthesis of polymers, (ii) additional polymerization, hydrogenation results, (iii) selected NMR spectra and GPC charts in the resultant polymers, and (iv) summary of tensile properties of the prepared film (PDF)

Author Contributions

§ Equal contribution as the first authors (M.K., X.W.).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Stempfle F.; Ortmann P.; Mecking S. Long-chain aliphatic polymers to bridge the gap between semicrystalline polyolefins and traditional polycondensates. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 4597–4641. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier M. A. R.; Metzger J. O.; Schubert U. S. Plant oil renewable resources as green alternatives in polymer science. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007, 36, 1788–1802. 10.1039/b703294c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Y.; Larock R. C. Vegetable oil-based polymeric materials: synthesis, properties, and applications. Green Chem. 2010, 12, 1893–1909. 10.1039/c0gc00264j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Biermann U.; Bornscheuer U.; Meier M. A. R.; Metzger J. O.; Schäfer H. J. Oils and fats as renewable raw materials in chemistry. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 3854–3871. 10.1002/anie.201002767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillmyer M. A.; Tolman W. B. Aliphatic polyester block polymers: Renewable, degradable, and sustainable. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 2390–2396. 10.1021/ar500121d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monomers and polymers from chemically modified plant oils and their fatty acids. In Polymers from Plant Oils, 2nd ed.; Gandini A., Lacerda T. M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; Scrivener Publishing LLC: Hoboken, NJ, USA, Beverly, MA, USA, 2019; pp 33–82. [Google Scholar]

- Nomura K.; Binti Awang N. W. Synthesis of bio-based aliphatic polyesters from plant oils by efficient molecular catalysis: A selected survey from recent reports. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 5486–5505. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.1c00493. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Biermann U.; Bornscheuer U. T.; Feussner I.; Meier M. A. R.; Metzger J. O. Fatty acids and their derivatives as renewable platform molecules for the chemical industry. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 20144–20165. 10.1002/anie.202100778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coates G. W.; Getzler Y. D. Y. L. Chemical recycling to monomer for an ideal, circular polymer economy. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2020, 5, 501–516. 10.1038/s41578-020-0190-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Häußler M.; Eck M.; Rothauer D.; Mecking S. Closed-loop recycling of polyethylene-like materials. Nature 2021, 590, 423–427. 10.1038/s41586-020-03149-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worch J. C.; Dove A. P. 100th Anniversary of macromolecular science viewpoint: Toward catalytic chemical recycling of waste (and future) plastics. ACS Macro Lett. 2020, 9, 1494–1506. 10.1021/acsmacrolett.0c00582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura K.; Aoki T.; Ohki Y.; Kikkawa S.; Yamazoe S. Transesterification of methyl-10-undecenoate and poly(ethylene adipate) catalyzed by (cyclopentadienyl) titanium trichlorides as model chemical conversions of plant oils and acid-, base-free chemical recycling of aliphatic polyesters. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 12504–12509. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.2c04877. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sudhakaran S.; Siddiki S. M. A. H.; Kitiyanan B.; Nomura K. CaO catalyzed transesterification of ethyl 10-undecenoate as a model reaction for efficient conversion of plant oils and their application to depolymerization of aliphatic polyesters. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 12864–12872. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.2c04287. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ohki Y.; Ogiwara Y.; Nomura K. Depolymerization of polyesters by transesterification with ethanol using (cyclopentadienyl) titanium trichlorides. Catalysts 2023, 13, 421.and related references cited therein 10.3390/catal13020421. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.; Zhao W.; Nomura K. Synthesis of high molecular weight biobased aliphatic polyesters by acyclic diene metathesis polymerization in ionic liquids. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 7222–7233. 10.1021/acsomega.3c00390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz M. D.; Wagener K. B.. ADMET Polymerization. In Handbook of Metathesis, 2nd ed.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2015; Vol. 3, pp 315–355. 10.1002/9783527674107.ch39 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caire da Silva L.; Rojas G.; Schulz M. D.; Wagener K. B. Acyclic diene metathesis polymerization: History, methods and applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2017, 69, 79–107. 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2016.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.; Abdellatif M. M.; Nomura K. Olefin metathesis polymerization: Some recent developments in the precise polymerizations for synthesis of advanced materials (by ROMP, ADMET). Tetrahedron 2018, 74, 619–692. 10.1016/j.tet.2017.12.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pribyl J.; Wagener K. B.; Rojas G. ADMET polymers: synthesis, structure elucidation, and function. Mater. Chem. Front. 2021, 5, 14–43. 10.1039/D0QM00273A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rybak A.; Meier M. A. R. Acyclic diene metathesis with a monomer from renewable resources: Control of molecular weight and one-step preparation of block copolymers. ChemSusChem 2008, 1, 542–547. 10.1002/cssc.200800047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fokou P. A.; Meier M. A. R. Use of a renewable and degradable monomer to study the temperature-dependent olefin isomerization during ADMET polymerizations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 1664–1665. 10.1021/ja808679w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutlu H.; Meier M. A. R. Unsaturated PA X,20 from renewable resources via metathesis and catalytic amidation. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2009, 210, 1019–1025. 10.1002/macp.200900045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Espinosa L. M.; Ronda J. C.; Galià M.; Cádiz V.; Meier M. A. R. Fatty acid derived phosphorus-containing polyesters via acyclic diene metathesis polymerization. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. 2009, 47, 5760–5771. 10.1002/pola.23620. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fokou P. A.; Meier M. A. R. Studying and suppressing olefin isomerization side reactions during ADMET polymerizations. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2010, 31, 368–373. 10.1002/marc.200900678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortmann P.; Mecking S. Long-spaced aliphatic polyesters. Macromolecules 2013, 46, 7213–7218. 10.1021/ma401305u. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lebarbé T.; Neqal M.; Grau E.; Alfos C.; Cramail H. Branched polyethylene mimicry by metathesis copolymerization of fatty acid-based α,ω-dienes. Green Chem. 2014, 16, 1755–1758. 10.1039/C3GC42280A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shearouse W. C.; Lillie L. M.; Reineke T. M.; Tolman W. B. Sustainable polyesters derived from glucose and castor oil: Building block structure impacts properties. ACS Macro Lett. 2015, 4, 284–288. 10.1021/acsmacrolett.5b00099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llevot A.; Grau E.; Carlotti S.; Grelier S.; Cramail H. ADMET polymerization of bio-based biphenyl compounds. Polym. Chem. 2015, 6, 7693–7700. 10.1039/C5PY01232E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barbara I.; Flourat A. L.; Allais F. Renewable polymers derived from ferulic acid and biobased diols via ADMET. Eur. Polym. J. 2015, 62, 236–243. 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2014.11.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Le D.; Samart C.; Kongparakul S.; Nomura K. Synthesis of new polyesters by acyclic diene metathesis polymerization of bio-based α,ω-dienes prepared from eugenol and castor oil (undecenoate). RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 10245–10252. 10.1039/C9RA01065C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura K.; Chaijaroen P.; Abdellatif M. M. Synthesis of biobased long-chain polyesters by acyclic diene metathesis polymerization and tandem hydrogenation and depolymerization with ethylene. ACS Omega. 2020, 5, 18301–18312. 10.1021/acsomega.0c01965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piccini M.; Leak D. J.; Chuck C. J.; Buchard A. Polymers from sugars and unsaturated fatty acids: ADMET polymerisation of monomers derived from D-xylose, D-mannose and castor oil. Polym. Chem. 2020, 11, 2681–2691. 10.1039/C9PY01809C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima M.; Abdellatif M. M.; Nomura K. Synthesis of semicrystalline long chain aliphatic polyesters by ADMET copolymerization of dianhydro-D-glucityl bis(undec-10-enoate) with 1,9-decadiene and tandem hydrogenation. Catalysts 2021, 11, 1098. 10.3390/catal11091098. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Piccini M.; Lightfoot J.; Dominguez B. C.; Buchard A. Xylose-based polyethers and polyesters via ADMET polymerization toward polyethylene-like materials. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2021, 3, 5870–5881. 10.1021/acsapm.1c01095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Another example in ADMET polymerization of α,ω-dienes under bulk conditions:; Bell M.; Hester H. G.; Gallman A. N.; Gomez V.; Pribyl J.; Rojas G.; Riegger A.; Weil T.; Watanabe H.; Chujo Y.; Wagener K. B. Bulk acyclic diene metathesis polycondensation. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2019, 220, 1900223. 10.1002/macp.201900223. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- The results were partly introduced in 11th The International Symposium on Feedstock Recycling of Polymeric Materials (ISFR), keynote X, Pattaya, Thailand, December 2022.

- Nomura K.; Morimoto H.; Imanishi Y.; Ramhani Z.; Geerts Y. Synthesis of high molecular weight trans-poly(9,9-di-n-octylfluorene-2,7-vinylene) by the acyclic diene metathesis polymerization using molybdenum catalysts. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. 2001, 39, 2463–2470. 10.1002/pola.1223. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miyashita T.; Kunisawa M.; Sueki S.; Nomura K. Synthesis of poly(arylene vinylene) s containing different end groups by combined acyclic diene metathesis polymerization with Wittig-type coupling. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 5288–5293. 10.1002/anie.201700466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L.; Makino R.; Shimoyama D.; Kadota J.; Hirano H.; Nomura K. Synthesis of ethylene/isoprene copolymers containing cyclopentane/cyclohexane units as unique elastomers by half-titanocene catalysts. Macromolecules 2023, 56, 899–914. 10.1021/acs.macromol.2c02399. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kitphaitun S.; Chaimongkolkunasin S.; Manit J.; Makino R.; Kadota J.; Hirano H.; Nomura K. Ethylene/myrcene copolymer as new bio-based elastomers prepared by coordination polymerization using titanium catalysts. Macromolecules 2021, 54, 10049–10058. 10.1021/acs.macromol.1c01878. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto Y.; Abdellatif M. M.; Nomura K. Polymer composites of biobased aliphatic polyesters with natural abundant fibers that improve the mechanical properties. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2023, 10.1007/s10163-023-01756-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; The SEM micrographs revealed that the morphology of the films prepared by the hot press method showed a smooth and regular surface, whereas the images by using the solvent cast method showed irregular surface morphologies (also shown in Figure S33).

- Wang X.; Chin A. L.; Zhou J.; Wang H.; Tong R. Resilient poly(α-hydroxy acids) with improved strength and ductility via scalable stereosequence-controlled polymerization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 16813–16823. 10.1021/jacs.1c08802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The increased entanglement (including the formation of spherulite) in the amorphous region upon increasing the molecular weight of HP1 causes an increase of tie molecules after crystallization was confirmed by measurement of crystallization rate, and the results were partly introduced in the following symposium. Nishiyama A.; Takeshita H.; Tokumitsu K.; Nomura K.. 71st Symposium on Macromolecules; The Society of Polymer Science: Japan, (September 2022, 1Pe041, Sapporo, Japan). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.