Abstract

Science advisory boards and policy organizations have called for adolescent brain science to be incorporated into juvenile probation operations. To achieve this, Opportunity-Based Probation (OBP), a probation model that integrates knowledge of adolescent development and behavior change principles, was developed in collaboration with a local juvenile probation department. The current study compares outcomes (recidivism and probation violations) for youth in the OBP condition versus probation as usual. Inverse probability weighting (IPW) and coarsened exact matching (CEM) were used to estimate causal effects of OBP’s average treatment effect (ATE). Results indicated clear effects of OBP on reducing criminal legal referrals, but no significant effects were observed for probation violations. Overall, results provide promising recidivism-reduction effects in support of developmentally grounded redesigns of juvenile probation.

Keywords: juvenile, probation, adolescent development, community supervision, implementation, juvenile justice, recidivism

National calls by influential policy organizations and scientific advisory committees make clear the importance of integrating the science of adolescent development into youth criminal legal operations (Schwartz, 2018). Positive youth development frameworks and evidence-based curricula suggest that juvenile probation should shift to teaching accountability without the criminalization of normative adolescent behavior (National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges [NCJFCJ], 2018; National Research Council [NRC], 2013). Recommendations for reform include providing incentives rather than sanctions, focusing on family and community engagement, and implementing standardized risk/needs assessments to support individualized probation goals (The Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2018; NCJFCJ, 2018; NRC, 2013; Tuell et al., 2017). These calls for transformation of juvenile probation practices highlight the importance of centering racial and ethnic equity in all reform efforts (The Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2018; NRC, 2013). Stakeholders at many levels within these agencies have perceived the need to radically transform juvenile probation operations (The Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2018; NCJFCJ, 2018; NRC, 2013).

PROBATION AS USUAL

Juvenile probation evolved as an alternative to incarceration that functioned independently from the courts’ purview and had a rehabilitative focus (Schwalbe, 2012; Walker et al., 2020). As probation came under the control of the courts, it gradually became more compliance-focused (Schwalbe, 2012). Consequently, modern day probation practice often veers between the compliance-focused model and the social work–focused model, each with its own theory of change and definition of probation’s role (Schwalbe, 2012; Schwartz, 2018; Skeem & Manchak, 2008). The compliance-focused model emphasizes the need for control, surveillance, and punishment, while the social work-focused model is aligned with treatment and rehabilitation. Both frameworks ultimately aim to reduce recidivism and increase public safety (Schwartz, 2018); however, empirical evidence suggests that traditional compliance-focused approaches to youth criminal legal involvement do not effectively control crime rates and may even lead to increased delinquent behavior (Huizinga et al., 2003; Petrosino et al., 2010).

The iatrogenic effects of probation involvement are largely attributed to the increased surveillance of youth behavior rather than increases in delinquent behavior. The increase in supervision contacts and implementation of additional rules to be followed (i.e., conditions of probation) increases the likelihood that rule-breaking behavior will be noticed and punished (Paparozzi & Gendreau, 2005). Conditions of probation frequently include restriction of behaviors that are normative for adolescents, such as early curfew and movement restriction (e.g., not being allowed to leave their county of residence without probation officer’s approval). Violating these conditions can result in punitive actions such as prolonged probation and detention (Dir et al., 2020; Goldstein et al., 2016), both of which are associated with poor long-term outcomes (e.g., increased likelihood of criminal behavior in adulthood, increased aggression, disruption of normative adolescent development; Gatti et al., 2009; Goldstein et al., 2016; Schwartz, 2018).

PRIOR INCORPORATION OF ADOLESCENT DEVELOPMENTAL SCIENCE INTO PROBATION PRACTICES

Existing research suggests behavioral modification approaches (contingency management) can be feasibly incorporated into probation, but effects on recidivism are still unknown. Very few studies test the feasibility of design or implementation. Proposed reforms and studies suggest some common approaches in how principles of adolescent development can be integrated into juvenile probation practice. Goldstein and colleagues (2016) proposed a model of probation grounded in behavior modification approaches (i.e., operant conditioning, behavior shaping, learning theory) and adolescent development (e.g., sensitivity to rewards, importance of peer relationships, limited future orientation). The model highlights the importance of youth experiencing success shortly after initiating probation, progress over perfection, and increased interaction with positive peer groups. Two recent studies found behavioral modification using positive reinforcement in juvenile probation was acceptable to probation officers (Rudes et al., 2021; Sheidow et al., 2020). Sheidow and colleagues (2020) found that juvenile probation officers trained in contingency management (i.e., a behavior modification approach using reinforcement principles) were able to deliver this approach as well or better than trained psychotherapists. Rudes and colleagues (2021) reported that juvenile probation officers who used contingency management reported stronger relationships with youth on probation, as well as more positive perceptions and increased confidence in their work.

In addition to contingency management, the literature suggests juvenile probation staff are amenable to adopting other therapeutic and positive youth development principles. Schwartz (2018) found that principles of positive reinforcement and positive youth development principles could be replicated across multiple probation departments. Specific principles of positive youth development include competency and engagement (e.g., employment, school, problem-solving skills), opportunities for prosocial connection, and confidence (through achievement of goals and emphasizing small successes; Arnold & Silliman, 2017; Bonell et al., 2016; Ciocanel et al., 2017; Geldhof et al., 2014). In their review, probation departments adopted empirically validated assessment instruments, motivational interviewing techniques, teaching accountability without criminalization of behaviors, and collaborative goal-setting processes (Schwartz, 2018; Torbet, 2008). The success of these programs suggests that principles of adolescent development are feasible to implement across diverse juvenile probation settings.

Instituting reforms in juvenile probation is particularly important for reducing the disparities of contact and harm experienced by youth of color (YOC). Black youth are more likely to receive probation violations (Dir et al., 2020; Smith et al., 2009) and may receive harsher consequences for these violations (Krezmien et al., 2008; Leiber & Peck, 2013; Mallett & Stoddard-Dare, 2010; Steinmetz & Anderson, 2016). Young Black people are also more likely to receive a wider range of and more restrictive conditions on probation (Kimchi, 2019). Often, well-intentioned programs developed to decrease disproportionate minority contact have been unsuccessful because the benefits of increased discretion in lifting restrictions or sanctions more often accrue to White youth (Saunders et al., 2021; Walker et al., 2017). Consequently, it is critical that any reform efforts examine outcomes by race/ethnicity to ensure that benefits are distributed equally across groups.

Overall, probation reforms centered in adolescent development principles are promising, but little is known about whether these reforms will translate into changes in the use of probation violations and future legal system involvement for youth. Recidivism is only a partial measure of youth progress and does not account for gains being made in school and family functioning (Butts & Schiraldi, 2018). At the same time, it remains a metric of significant public interest as it reflects one of the responsibilities of the youth criminal legal system to improve public safety. This study adds to the limited literature examining the impact of probation reforms on probation outcomes and continued legal system contact for adolescents.

OPPORTUNITY-BASED PROBATION (OBP)

OBP was codesigned by university-based researchers and a medium-sized probation department (Pierce County Juvenile Court [PCJC] in Washington State) using a structured method for integrating evidence and local expertise (Davies et al., 2016; Sanders & Stappers, 2008). Model development is reported in detail elsewhere (Walker et al., 2020) and we summarize the final model here. OBP is grounded in principles of adolescent social and emotional development and behavior change principles. The model emphasizes four intervention principles: reward-based motivation, structured goal setting, family engagement, and positive youth development. Primary elements of adolescent brain development, including a drive toward independence, heightened responsivity to rewards, underdeveloped cognitive control, underdeveloped planning/future orientation, sensitivity to family/home environment, and influence of peer approval, were incorporated throughout OBP.

Juvenile probation counselors monitor probation goals and caregivers monitor home goals on a routine schedule. The reward-based structure awards points for met goals that result in small, material rewards (e.g., chips, nail polish, US$5 gift card, key chain, gum, bath bomb, bus pass) similar to contingency management schedules. Points also accumulate toward social rewards that build rapport between the probation staff, the youth, and the family (e.g., lunch with probation staff, vouchers/tickets for family activities). As youth accrue points and demonstrate success on probation, they also become eligible for internships, youth development activities, or modest financial support to advance career goals or interests (up to US$200). Upon successful completion of the OBP program, youth can also earn early release from probation.

In the model, probation staff meet with the caregiver and youth during pretrial to discuss the probation plan and the caregiver’s goals for the youth during probation. Caregiver goals set during this early structured goal-setting phase become part of the official probation plan along with goals guided by a court risk/needs assessment and a plan for strengthening youth and family skills to reduce the risk of youth reoffending. In addition to the initial caregiver meeting, the model asks caregivers to monitor youth progress toward goal achievement and assign points for completion of action steps. This caregiver involvement supports positive relationship development within families. If a primary caregiver was not available, the probation officer worked with the youth to identify another natural support such as an extended family member or older sibling who could be involved in the probation process. Positive youth development is incorporated throughout OBP, including but not limited to the focus on competency attainment, increased prosocial community connections, and relationship building within families and with probation counselor.

More contact with traditional juvenile probation departments often increases the number of probation violations due to increased likelihood that rule-breaking behavior will be identified. However, the OBP framework protects against this by working with the youth to determine what led to rule-breaking behaviors and creating a plan to address these issues, rather than simply issuing a probation violation. There is no written policy regarding how OBP officers must respond to probation violations; however, there was a soft expectation to use a conflict resolution approach to address behavioral issues first, before issuing a probation violation. OBP allows for probation counselors to understand behavioral issues as teachable moments rather than something that needs to be punished.

A process and formative evaluation of the program found OBP to be feasible to implement among probation counselors in addition to being well received by youth and families (Walker et al., 2020). This study extends previous evaluations of OBP by examining the model’s impact on youth recidivism and probation violations.

THE CURRENT STUDY

The field lacks studies that examine the impact of developmentally grounded juvenile probation on probation violations and recidivism. The current study examines the effects of OBP, one model of developmentally grounded probation, on 6-month recidivism and probation violations using a quasi-experimental, matched sample design. Given previous research demonstrating the beneficial effects of social and cognitive skills–based programs and positive youth development programs within populations who are legally involved, we hypothesized that this approach to juvenile probation would decrease recidivism, reduce probation violations, and demonstrate similar effects for YOC and White youth.

METHOD

DATA SOURCES

Data for the study came from two sources. Information about youth probation start date for the OBP and comparison youth, as well as youth demographics (gender, race/ethnicity, age at time of probation) were drawn from PCJC’s electronic record system. Information about youth court contact history was drawn from the Washington State Administrative Office of the Courts’ (AOC) court contact database. The AOC court contact database is the state data management system for all court contacts (youth and adult) across jurisdictions in Washington State. Data were obtained from August 2016 through October 2018 (26 months) for youth charges (historical and during the observation period) recorded in any county in the state.

SAMPLE

We obtained data on all PCJC probation-involved youth in the 26-month observation period who scored as moderate or high risk at the time of observation using the court risk/needs instrument (Positive Achievement Change Tool [PACT]; Florida Department of Juvenile Justice, 2009; Hamilton et al., 2015; Hay & Widdows, 2013) and who had a referral offense that defined their entry into probation. These criteria resulted in 310 youth total, with 279 youth in the comparison group (probation as usual) and 31 youth who participated in OBP (Table 1). A larger sample size was not available, as study parameters and timeline were determined by funding. The sample reflected demographic distributions in other juvenile court jurisdictions in Washington State and was primarily male (73%) and White (59%). Black youth made up 33% of the sample. Asian, Pacific Islander, or Indigenous youth together accounted for 8% of the sample. This group will be referred to as non-Black YOC. Information regarding ethnicity was not available. The mean age at entry was 15.3 years; mean age of first prior referral was 14.5 years. A majority of the sample scored as high risk (67%) on the PACT compared with moderate risk (33%), and 52% of the sample had a least one prior referral before their entry referral. The average number of total prior referrals was 2.37, including entry referral (SD = 2.11). The average seriousness (as coded by the AOC) of prior referrals was 5.72 (SD = 2.00) based on a 0–9 scale.

TABLE 1:

Sample Demographics by Treatment and Comparison Groups

| Demographic | OBP, n = 31 | Control, n = 279 | Total N = 310 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Racea,b | |||

| White | 17 (55%) | 166 (59%) | 183 (59%) |

| Black | 12 (39%) | 91 (33%) | 103 (33%) |

| Non-Black youth of color | 2 (6%) | 22 (8%) | 24 (8%) |

| Recorded sexa | |||

| Male | 22 (71%) | 204 (73%) | 226 (73%) |

| Female | 9 (29%) | 75 (27%) | 84 (27%) |

| Risk levela | 22 (71%) | 185 (66%) | 207 (67%) |

| Age at first referralc | 14.13 (1.50) | 14.50 (1.50) | 14.46 (1.50) |

| Age at entry referralc | 15.03 (1.28) | 15.34 (1.31) | 15.31 (1.30) |

| Number of prior referralsc | 2.94 (2.24) | 2.31 (2.09) | 2.37 (2.11) |

| Average seriousness of priorsc | 6.42 (1.54) | 5.64 (2.03) | 5.72 (2.00)* |

| No. of new referrals (at 6 months)c,d | 0.36 (0.70) | 1.01 (1.41) | 0.95 (1.38)* |

| No. of new violations (at 6 months)c,d | 1.84 (2.48) | 1.00 (1.53) | 1.07 (1.65)* |

Note. OBP = Opportunity-Based Probation; ANOVA = analysis of variance.

Chi-square tests were used for nonparametric data: n and (percentage of sample) are reported.

No information regarding ethnicity was available; thus, Latinx/Hispanic youth could be in each race category.

ANOVA was used for continuous data: M and (SD) are reported.

A minimum 6-month observation period reduces the n for each group (OBP, n = 25, Control, n = 265).

p < .05.

MEASURES

Dependent Variables

This study examined two outcomes: probation violations and recidivism. Each outcome was measured as a count distribution and a dichotomous outcome (0/1 absent of any/presence). Probation violations were counted from the probation start date through the end of 6-month observation period. Individual probation counselors determined what behaviors met threshold for probation violations; however, common behaviors constituting probation violations included consistent noncompliance with court orders, not engaging with probation, drug/alcohol use, running away from home for more than 24 hr, and truancy. Recidivism was measured as the counts of referrals from law enforcement to the prosecutor for offenses after the probation start date through the 6-month window, as well as a simple dichotomy of having (1) or not having (0) a referral. The start date of probation was used as the cutoff date for calculating prior referrals (before) and recidivism (after). If a youth began a probation term more than once in the observation period, the earliest probation date was selected.

We used referrals rather than filings or convictions as our recidivism variable to avoid undercounting recidivism events due to variability in how individual cases were processed by prosecutors. Referrals are reports sent by law enforcement officers to the juvenile prosecutor division about an event a law enforcement officer determines to be a criminal offense. The prosecutor’s office may not file criminal charges after receiving a referral for a number of reasons unrelated to whether the prosecutor determines the event to be eligible for filing. For example, the prosecutor may judge the evidence to be insufficient to demonstrate “probable cause,” or, more often, prosecutors may use their discretion to offer youth and families diversion options outside of filing charges with the court. As we did not have access to information about whether prosecutor diversions were offered in individual cases, we used referral rather than filing or conviction to guard against any unobserved decision-making processes applied by the prosecutor’s office.

OBP Involvement

Involvement in OBP was defined as referral to the program by juvenile probation counselors (i.e., intent to treat). All youth assigned to probation at moderate or high risk of recidivism and whose whereabouts were known were eligible for referral to OBP. This included youth referred to substance use treatment, intensive mental health treatment, and routine field supervision. Youth who had a known history of runaway behavior or extreme housing instability were not typically referred to OBP. Youth who were excluded from OBP were included in the probation as usual condition. The court referral process prioritized YOC when considering candidates. Operationally, referral to OBP involved assigning a youth to one of the five probation counselors who codeveloped or were trained to deliver OBP (three codevelopers, two trained after development). Decisions about referring a new case to OBP were made by the supervisors based on current workload and capacity of the five OBP counselors out of a total of 18 probation counselors. Because of the additional time and cost required to deliver OBP, OBP-trained counselors continued to supervise mixed caseloads, about half OBP and half non-OBP youth. OBP-trained counselors continued to deliver probation as usual to youth on their caseload who were not assigned to OBP. Training for new counselors involved a 3-hr presentation co-delivered by probation staff and the university partner, and monthly peer consultation throughout the study period. Monthly peer consultation involved staffing cases and discussing implementation issues with the rest of the OBP team including a probation supervisor who was also involved in program development. The university codeveloper worked with the team approximately bimonthly to consult on implementation. The monthly peer consultation and bimonthly university team meetings served as the primary fidelity checks regarding probation counselor implementation of OBP.

Youth in the comparison group received probation as usual. This included a case planning meeting with the youth and caregiver following assignment to the probation counselor, the development of a probation plan guided by the risk/needs assessment, routine check-ins by the probation counselor on the youth’s progress, and general assistance with problem-solving program engagement and school attendance with the parent and other social service providers. Youth in OBP and the comparison group had the same access to court-provided services, including cognitive-behaviorally based problem-solving groups, substance use outpatient treatment, and family therapy, when available.

Covariates

Covariates of youth recidivism were included in the model to statistically control for group mean differences in the nonrandom assignment to OBP and as known correlates of youth recidivism. These included age at first referral, age at the time of probation initiation, gender, race, prior criminal referrals, seriousness of prior offenses, and current risk assessment level. Age was included as a continuous variable ranging from 12 to 18 years old. Recorded sex was included as a dichotomous variable (female/male). Due to low numbers of Asian, Pacific Islander, and Indigenous youth (i.e., non-Black YOC), we created a categorical race variable with three levels (Black, non-Black YOC, White). Without a variable for ethnicity, it is possible that ethnically Latinx/Hispanic youth could appear in any of the three categories. Some indicators in the administrative data suggested the Latinx/Hispanic category is small. Prior referral was a count of all previous referrals to any juvenile court in Washington State for a criminal matter, including the referral that initiated their current probation status. Risk level was a dichotomous variable indicating whether the youth scored moderate or high on the PACT assessment at the start of the most recent probation period.

WEIGHTING, MATCHING, AND ANALYTIC APPROACH

We use two strategies to account for differences between OBP youth and those youth receiving probation as usual. We present analyses based on inverse probability weight (IPW) from propensity scores (Austin, 2011; Rosenbaum & Rubin, 1983; Thoemmes & Ong, 2016) and from direct matching based on coarsened exact matching (CEM; Blackwell et al., 2009; Iacus et al., 2012). A propensity score is the probability of group assignment, in this case OBP versus probation as usual, conditional on observed baseline covariates (Rosenbaum & Rubin, 1983). In observational studies, the true propensity is not known and can only be estimated by the available data. Similar to randomized trials, residual differences may still exist in the observed baseline covariates between groups after matching and regression adjustment is commonly used to increase precision (Lunceford & Davidian, 2004). CEM groups values of the covariates used for matching in a manner that allows for easier exact matching on the coarsened value (retaining more matches) and then in a subsequent analysis uses the non-coarsened values of the covariates to adjust for resulting differences due to the matching on less specific values. Because critiques of both methods are cited in the literature, we compare the outcomes of these methods to examine the consistency of results (Iacus et al., 2012; Rosenbaum & Rubin, 1983). Some work suggests propensity score approaches using inverse weighting produce comparable balance to CEM and other exact matching techniques (Austin & Stuart, 2017; Jann, 2017). As CEM often reduces or changes the actual number of cases in the treatment and control groups, there is a risk that CEM may alter generalization and change the efficiency due to smaller sample size. Therefore, we included both IPW and CEM results in this analysis as a sensitivity check on the findings, given the small sample size.

We present the results from the propensity score method supplemented by the CEM approach. In all cases, the matching routines provided a causal estimate of the effect of OBP and are presented as the average treatment effect (ATE); we used robust and bootstrap standard errors to assess the ATE confidence intervals (CIs). ATE can be understood as the difference between the outcomes postulating a hypothetical condition if youth who received the treatment had not received the treatment, and if youth in the comparison, in fact, received the treatment (Holland, 1986).

RESULTS

UNADJUSTED RESULTS

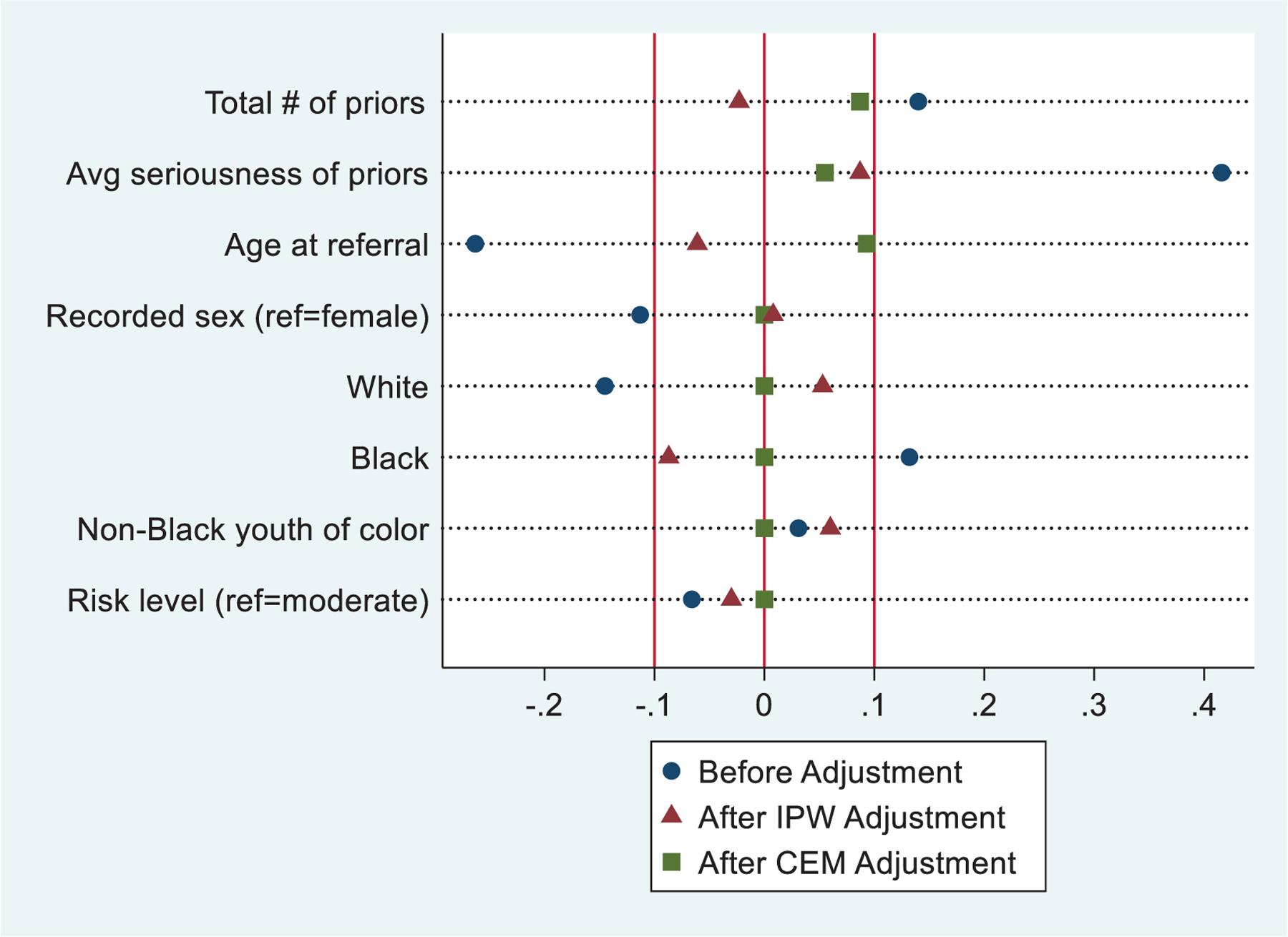

Imbalance in the unmatched samples was present in age and number of prior offenses between the OBP and comparison groups (Figure 1). Youth in OBP were younger than control by about 4 months and had an average of 0.60 more prior offenses than comparison youth (OBP, M = 2.94; control, M = 2.31; Table 1). Prior criminal referrals ranged from 1 to 16 and was right-skewed; the mean for priors was 2.94 (OBP) and 2.31 (controls). The simple outcome results unadjusted for baseline differences show OBP, compared with controls, to have lower recidivism within the 6-month exposure window (M = 0.36, M = 1.01) and higher probation violations for OBP versus control (M = 1.84, M = 1.00). Using the 6-month window eliminates six OBP youth and 14 probation as usual youth who were not included for this full window postentry referral date. With a simple mean difference of one postreferral or one probation violation between OBP (n = 25) and comparison groups (n = 265), power is >0.99 at an alpha of .05. If we reduce the n to 22 (OBP) and 86 (control) due to failed matches, as in the CEM analysis, power is reduced to approximately 0.85.

Figure 1: Balance in Sample Covariates Between Groups Before and After IPW and CEM Adjustment.

Note. IPW = inverse probability weight; CEM = coarsened exact matching.

IPW

We conducted IPW by running a logistic regression model to predict OBP selection using all of the covariates available to our study (race, age, gender, prior referrals, seriousness of priors, risk level). Two youth in the OBP group were missing scores on risk level, and we used regression substitution to impute these two scores (Rosenbaum & Rubin, 1983). As a sensitivity check, we also ran the analytic models with listwise deletion of the youth with missing data removed, and by assigning youth all combinations of moderate and high risk. The results did not substantively change, and we present results from the imputed values here. Missingness was attributed to input error and was consistent with typical administrative data. Balance on the covariates between OBP and control group after IPW was strong (see Figure 1). Tests of the effect of OBP on recidivism and probation violations were run with negative binomial models for counts (number of referrals, number of probation violations) and with multivariate logistic regression models for dichotomous outcomes (any referrals, any probation violations).

The results for IPW matching show the ATE for recidivism: dichotomous ATE = −0.20, 95% CI = [−0.43, 0.03] and count ATE = −0.61, 95% CI = [−0.96, −0.25] for models without covariate adjustment, and dichotomous ATE = −0.16, 95% CI = [−0.51, 0.19] and count ATE = −0.59, 95% CI = [−1.09, −0.09] for models with covariates (Table 2). All recidivism count models were statistically significant in the expected direction; models of any recidivism were in the correct direction but not different from zero. For probation violations (continuous or count), there was no statistically significant difference between OBP and control groups in the IPW models and all effects were in a positive, rather than negative, direction.

TABLE 2: Average Effect Due to Treatment (ATE) Across Multiple Models.

| Statistical technique | Probation violation count |

Probation violation any |

Referral count |

Referral any |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | 95% CI | Effect | 95% CI | Effect | 95% CI | Effect | 95% CI | |

| IPW | 0.77 | [−0.34, 1.88] | 0.17 | [−0.06, 0.39] | −0.61* | [−0.96, −0.25] | −0.20 | [−0.43, 0.03] |

| IPW with covariates | 0.84 | [−0.78, 2.48] | 0.14 | [−0.26, 0.54] | −0.59* | [−1.09, −0.09] | −0.16 | [−0.51, 0.19] |

| CEM | 0.64 | [−0.54, 1.84] | 0.18 | [−0.06, 0.42] | −0.82* | [−1.37, −0.28] | −0.25* | [−0.48, −0.01] |

| CEM with covariates | 0.63 | [−0.47, 1.72] | 0.17 | [−0.05, 0.41] | −0.82* | [−1.37, −0.27] | −0.26* | [−0.48, −0.03] |

Note. CEM, n = 121; IPW, n = 290. ATE = average treatment effect; CI = confidence interval; IPW = inverse probability weight; CEM = coarsened exact matching.

p < .05.

Additional analyses were performed to supplement the ATE estimates. Tests of the effect of OBP on recidivism and probation violations were run with weighted negative binomial models for counts (number of referrals, number of probation violations) and with weighted multivariate logistic regression models for dichotomous outcomes (any referrals, any probation violations). The results were similar: OBP demonstrated significantly lower counts and presence of postprobation referrals while OBP had weak (nonsignificant) positive effects on probation violations.

CEM

To conduct CEM, we used similar, but fewer, covariates as were used for the IPW models. In CEM, all variables were categorized to create “bins” reflecting a coarser categorization than the probability matches used in IPW. The following describes the collapsed structure: age = 1 (under age 15), 2 (age 15 and 16), 3 (age 17 and 18); number of priors = 0 (none), 1 (1 to 2 priors), 2 (3 or more priors); race/ethnicity = 1 (White), 2 (Black), 3 (non-Black YOC); and recorded sex = 1 (male), 0 (female). This method produced a high level of balance (Figure 1). The matching dropped two cases from the OBP group and 167 from the control group. Linear probability regression models (LPMs), with robust standard errors, were used to predict binary recidivism outcomes with the remaining sample (n = 121) with and without covariates; the LPM allows direct comparison with the ATE effects from IPW analysis. CEM models also included the same additional covariates (noncoarsened) in the regression models to adjust for any remaining differences after matching (Blackwell et al., 2009). Race was represented by the three categories with White as referent (White vs. Black and non-Black YOC), and the PACT risk level was categorized as high versus moderate. Results show that OBP treatment reduced recidivism compared with controls. For dichotomous outcomes, this effect was −0.25, 95% CI = [−0.48, −0.01] without covariates and −0.26, 95% CI = [−0.48, −0.03] with covariates (Table 2). The effect based on linear regression for count outcomes was −0.82, 95% CI = [−1.37, −0.28] without covariates, and −0.82, 95% CI = [−1.37, −0.27] with covariates. Models using logistic regression and negative binomial count models yielded similar results.

When predicting probation violations, the coarsened results for any violation showed an increase attributed to OBP of 0.18, 95% CI = [−0.06, 0.42] without covariates, and 0.17, 95% CI = [−0.05, 0.41] with covariates. However, these positive effects did not reach statistical significance. Analysis of the count of probation violations found similar unexpected positive effects for OBP at nonstatistically significant values. The corresponding differences for count of probation violations were 0.64, 95% CI = [−0.54, 1.84] without covariates and 0.63, 95% CI = [−0.47, 1.72] with covariates (Table 2). Again, using logistic and negative binomial count models provided similar results.

Preliminary assessment of the four outcomes by race/ethnicity, White versus YOC, was carried out by using the same IPW and CEM approaches above, with matching within each group. To build a model to test race/ethnicity interaction, we used the same covariates and coarsened variables from the original total sample analyses. Matching reduced the sample size within race categories for YOC in the IPW (n = 120) and CEM (n = 55) approaches. For White youth, the samples were reduced as well (IPW, n = 170; CEM, n = 84). Results were similar for White youth as for the total sample both in terms of any referral and count of referrals (e.g., IPW with covariate referral count for White youth: ATE = −0.58, 95% CI = [−0.90, −0.16]). For YOC, the effects were slightly stronger in magnitude (e.g., IPW with covariate referral count for YOC: ATE = −0.69, 95% CI = [−1.05, −0.33]). This same pattern held for the CEM results for referrals. Probation violations showed no strong, non-zero effects, and as in the total sample, the results were all in a positive, instead of the expected negative, direction. The interactions of treatment by White/YOC across the outcomes and across methods showed no statistically significant difference between the two groups. Overall, these preliminary results suggest no strong differences in outcomes for YOC versus White youth.

DISCUSSION

This study examined the effect of a developmentally grounded redesign of juvenile probation on the likelihood of probation violations and youth recidivism within 6 months. Our hypothesis that recidivism would be lower for youth who participated in OBP was supported, while our expectation that youth in OBP would also have fewer probation violations was not supported. Overall, results based on matching suggest clear effects that OBP involvement was associated with reduced legal referrals to the youth or adult system for counts of referrals and the presence/absence of any referral. The CEM models suggest a difference of almost one full referral (e.g., −0.82 referral) within the 6-month window of exposure. Evidence for effects on probation violations is less clear, with OBP associated with increases in counts of probation violations and likelihood of any probation violations; however, these increases were weak and not distinguishable from zero. This held in both the IPW and CEM approaches.

The OBP model is a multicomponent model that integrates multiple activities shown to be effective in reducing externalizing behaviors in youth in controlled studies. As an intent-to-treat study, we were able to study the effect of the model as a whole but did not examine how the dosage of any one component influenced outcomes. Consequently, the study provides preliminary support for the public safety benefit of providing developmentally grounded approaches to juvenile probation without being able to comment on the effect of any individual component. In OBP, “developmentally-grounded” was operationalized as using short-term, proactive goal setting with immediate rewards, the engagement of families in developing contingency-like goal setting and rewards, and the support of positive activities in the community. Routine review of goals and progress toward goals is an evidence-based service strategy in mental health treatment where it is referred to as measurement-based care (MBC; Fortney et al., 2017). In the present study, this approach was used to accommodate the still-developing capacities of adolescents to shape their behavior to achieve long-term goals by breaking tasks into short-term, weekly assignments. Our study’s findings also add support to the feasibility and benefit of implementing contingency-like schedules into juvenile probation routines (Schwalbe, 2012; Sheidow et al., 2020). While other studies have found positive outcomes of implementing contingency schedules on recidivism in adult probation (Rudes et al., 2012; Trotman & Taxman, 2011), this study demonstrates the benefit of a contingency-like schedule on youth recidivism as well.

The study hypothesis that probation violations would be lower for youth on OBP was not supported. The failure to meaningfully reduce probation violations may reflect the challenge of changing the fundamental role of probation as it operates in modern juvenile courts as a compliance-focused effort, net of other rehabilitative goals. As the sine qua non of probation is the role of the probation counselor in monitoring court orders, probation violations are most often reduced because probation counselors limit their contact to youth and, consequently, are unaware of violating behavior (Saunders et al., 2021). The increase in probation violations due to intensive probation supervision models is the primary reason these models are contraindicated (Lane et al., 2005). Given the increased expectations for contact in the early phases of OBP, it is encouraging that we did not observe a significant increase in violations.

Two probation supervisors were asked to reflect on possible spillover effects of OBP to non-OBP cases among juvenile probation counselors who handle both OBP and non-OBP cases. Probation supervisors reported that juvenile probation counselors trained in OBP were likely to change their approach to probation with their non-OBP cases as a result of a better understanding of adolescent brain development, scaffolding, and behavior change. Specifically, they stated these probation counselors might have been more likely to foster meaningful family involvement and complete intentional goal setting with their cases.

EFFECTS OF RACE/ETHNICITY

Given the issue of disproportionate minority contact in the youth criminal legal system (Dir et al., 2020; Kimchi, 2019; Saunders et al., 2021), it was important to identify whether outcomes of OBP differed by race/ethnicity to confirm that possible benefits were equitable across groups. Prior reform efforts have highlighted that even well-intentioned program development often benefits White youth more than YOC (Walker et al., 2017). In addition, White youth tend to accrue more benefits from models of increased discretion (Saunders et al., 2021; Walker et al., 2017). Our study did not find differential benefits between White youth and YOC experiencing OBP or as an interaction between OBP and probation as usual. This finding is preliminary, given the small sample size, and should be interpreted cautiously. However, the finding is in the expected direction, as OBP was designed to prioritize YOC in referrals. This resulted in proportionate representation of YOC in OBP compared with probation as usual, potentially guarding against the higher recruitment of White youth into therapeutically oriented programs.

LIMITATIONS

The current study is a pilot and is limited by small sample size and nonrandomized assignment. Given the increased intensity of OBP as compared with probation as usual, it is possible that the positive outcomes might reflect increased access to services rather than OBP-specific programming. This is a common limitation of treatment research where the specific components of treatment cannot be entirely determined, and particularly when compared with treatment as usual, as it is typical for treatment programs to provide a higher level of services than treatment as usual. Furthermore, study participants were drawn from a single juvenile probation department in Washington State, thus study findings have limited generalizability to other probation departments or areas of the country. This particular juvenile probation department appears to have a low baseline level of probation violations, which might impact generalizability of findings to other probation departments with a higher number of probation violations. It is possible that a program like OBP would be less accepted by a more traditional probation department, and thus evidence less significant change; however, if accepted, it could also increase the impact that a program like OBP might have on a probation department with a higher baseline level of probation violations. In addition, the small sample size did not allow for control clustering of probation counselors and we were unable to fully control for selection factors. No youth or caregiver opted out of OBP when it was offered, but probation supervisors made referrals based on who they thought would be a good candidate for increased supervision. Even though matching was applied during statistical analyses, selection factors cannot be fully ruled out. Of note, probation counselors who were conducting OBP were still assigned non-OBP cases and as we did not measure dosage or fidelity, we cannot be sure that non-OBP cases from these juvenile probation counselors did not benefit from spillover effects. A further limitation is that the developers of OBP completed this program evaluation. Research suggests that evaluations completed by program developers tend to have larger effect sizes than those completed by independent evaluators (Wolf et al., 2020).

In addition, recidivism is an imperfect measure of healthy youth development (Harvell et al., 2018). Contact with law enforcement and referrals are known to be driven by factors outside of youth behavior, including policing practices and community-level racism (Butts & Schiraldi, 2018). In future studies, it will be beneficial to measure the impact of reformed probation efforts on positive youth outcomes such as employment, education, and other indicators of well-being (Butts & Schiraldi, 2018; Harvell et al., 2018). Further research is also needed to determine which components of positive youth development are most important to incorporate into juvenile probation and youth criminal legal systems to decrease recidivism. It will also be important to determine whether more traditional probation departments would accept and implement progressive programs such as OBP and experience similar decreases in recidivism. Thus, additional research is needed to determine generalizability of positive outcomes (namely, decreased recidivism) from juvenile probation departments that have incorporated principles of positive youth development and adolescent brain science into their programs.

CONCLUSION

OBP is a developmentally based approach to probation supervision that capitalizes on the strengths of the individual probation department and the local community. The model has been successfully implemented and is associated with significant reductions in youth referrals for criminal behaviors at 6 months. This study provides preliminary support that developmentally grounded models of juvenile probation reduce youth recidivism and further system involvement. Continued development and replication of transformed probation practices for youth involved in the criminal legal system are critical to enhance positive youth development and community safety.

Acknowledgments

This study received partial funding through the Annie E. Casey Foundation.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

KATHRYN A. CUNNINGHAM, University of Washington

NOAH R. GUBNER, University of Washington

KRISTIN VICK, University of Washington.

JERALD R. HERTING, University of Washington

SARAH C. WALKER, University of Washington

REFERENCES

- The Annie E Casey Foundation. (2018). Transforming juvenile probation: A vision for getting it right https://www.aecf.org/resources/transforming-juvenile-probation/ [Google Scholar]

- Arnold ME, & Silliman B (2017). From theory to practice: A critical review of positive youth development program frameworks. Journal of Youth Development, 12(2), 1–20. 10.5195/jyd.2017.17 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Austin PC (2011). An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 46, 399–424. 10.1080/00273171.2011.568786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin PC, & Stuart EA (2017). The performance of inverse probability of treatment weighting and full matching on the propensity score in the presence of model misspecification when estimating the effect of treatment on survival outcomes. Statistical Methods in Medical Research, 26(4), 1654–1670. 10.1177/0962280215584401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell M, Iacus S, King G, & Porro G (2009). cem: Coarsened exact matching in Stata. The Stata Journal, 9, 524–546. 10.1177/1536867X0900900402 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bonell C, Hinds K, Dickson K, Thomas J, Fletcher A, Murphy S, Melendez-Torres GJ, & Campbell R (2016). What is positive youth development and how might it reduce substance use and violence? A systematic review and synthesis of theoretical literature. BMC Public Health, 16, Article 13. 10.1186/s12889-016-2817-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butts JA, & Schiraldi VN (2018). Recidivism reconsidered: Preserving the community justice mission of community corrections. Program in Criminal Justice Policy and Management, Harvard Kennedy School [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ciocanel O, Power K, Eriksen A, & Gillings K (2017). Effectiveness of positive youth development interventions: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46, 483–504. 10.1007/s10964-016-0555-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies N, Mathew R, Wilcock J, Manthorpe J, Sampson EL, Lamahewa K, & Iliffe S (2016). A co-design process developing heuristics for practitioners providing end of life care for people with dementia. BMC Palliative Care, 15, Article 68. 10.1186/s12904-016-0146-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dir AL, Magee LA, Clifton RL, Ouyang F, Tu W, Wiehe SE, & Aalsma MC (2020). The point of diminishing returns in juvenile probation: Probation requirements and risk of technical probation violations among first-time probation-involved youth. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 27, 283–291. 10.1037/law0000282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florida Department of Juvenile Justice. (2009). Residential Positive Achievement Change Tool (R-PACT) http://www.djj.state.fl.us/docs/partners-providers-staff/rpact-v1_3-florida-20090213.pdf?sfvrsn=2 [Google Scholar]

- Fortney JC, Unützer J, Wrenn G, Pyne JM, Smith GR, Schoenbaum M, & Harbin HT (2017). A tipping point for measurement-based care. Psychiatric Services, 68, 179–188. 10.1176/appi.ps.201500439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatti U, Tremblay RE, & Vitaro F (2009). Iatrogenic effect of juvenile justice. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 50, 991–998. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.02057.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geldhof GJ, Bowers EP, Boyd MJ, Mueller MK, Napolitano CM, Schmid KL, Lerner JV, & Lerner RM (2014). Creation of short and very short measures of the five Cs of positive youth development. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 24, 163–176. 10.1111/jora.12039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein NES, NeMoyer A, Gale-Bentz E, Levick M, & Feierman J (2016). “You’re on the right track!”: Using graduated response systems to address immaturity of judgment and enhance youths’ capacities to successfully complete probation. Temple Law Review, 88, 803–836. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton Z, van Wormer J, & Barnoski R (2015). PACT validation and weighting results: Technical report https://s3.wp.wsu.edu/uploads/sites/436/2017/02/PACT-Study-Final3.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Harvell S, Love H, Pelletier E, & Warnberg C (2018). Bridging research and practice in juvenile probation: Rethinking strategies to promote long-term change https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/99223/bridging_research_and_practice_in_juvenile_probation_1.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Hay C, & Widdows A (2013). Residential Positive Achievement Change Tool (R-PACT) validation study https://www.djj.state.fl.us/content/download/22778/file/r-pact_validation_study_powerpoint_june2013.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Holland PW (1986). Statistics and causal inference. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 81, 945–960. 10.1080/01621459.1986.10478354 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huizinga D, Schumann K, Ehret B, & Elliott A (2003). The effect of juvenile justice system processing on subsequent delinquent and criminal behavior: A cross-national study https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/205001.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Iacus SM, King G, & Porro G (2012). Causal inference without balance checking: Coarsened exact matching. Political Analysis, 20, 1–24. 10.1093/pan/mpr013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jann B (2017, June 23). Why propensity scores should be used for matching [Keynote address] 2017 German Stata Users Group Meeting, Berlin, Germany. https://www.stata.com/meeting/germany17/slides/Germany17_Jann.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Kimchi A (2019). Investigating the assignment of probation conditions: Heterogeneity and the role of race and ethnicity. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 35, 715–745. 10.1007/s10940-018-9400-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krezmien MP, Mulcahy CA, & Leone PE (2008). Detained and committed youth: Examining differences in achievement, mental health needs, and special education status. Education and Treatment of Children, 31, 445–464. 10.1353/etc.0.0029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lane J, Turner S, Fain T, & Sehgal A (2005). Evaluating an experimental intensive juvenile probation program: Supervision and official outcomes. Crime & Delinquency, 51, 26–52. 10.1177/0011128704264943 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leiber MJ, & Peck JH (2013). Probation violations and juvenile justice decision making: Implications for Blacks and Hispanics. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 11, 60–78. 10.1177/1541204012447960 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lunceford JK, & Davidian M (2004). Stratification and weighting via the propensity score in estimation of causal treatment effects: A comparative study. Statistics in Medicine, 23, 2937–2960. 10.1002/sim.1903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallett CA, & Stoddard-Dare P (2010). Predicting secure detention placement for African-American juvenile offenders: Addressing the disproportionate minority confinement problem. Journal of Ethnicity in Criminal Justice, 8, 91–103. 10.1080/15377931003761011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges. (2018). Resolution regarding juvenile probation and adolescent development. Juvenile and Family Court Journal, 69, 55–57. 10.1111/jfcj.12104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. (2013). Reforming juvenile justice: A developmental approach https://www.njjn.org/uploads/digital-library/Reforming_JuvJustice_NationalAcademySciences.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Paparozzi MA, & Gendreau P (2005). An intensive supervision program that worked: Service delivery, professional orientation, and organizational supportiveness. The Prison Journal, 85, 445–466. 10.1177/0032885505281529 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Petrosino A, Turpin-Petrosino C, & Guckenburg S (2010). Formal system processing of juveniles: Effects on delinquency. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 6, 1–88. 10.4073/csr.2010.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum PR, & Rubin DB (1983). The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika, 70, 41–55. 10.1093/biomet/70.1.41 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rudes DS, Taxman FS, Portillo S, Murphy A, Rhodes A, Stitzer M, Luongo PF, & Friedmann PD (2012). Adding positive reinforcement in justice settings: Acceptability and feasibility. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 42, 260–270. 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudes DS, Viglione J, Sheidow AJ, McCart MR, Chapman JE, & Taxman FS (2021). Juvenile probation officers’ perceptions on youth substance use varies from task-shifting to family-based contingency management. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 120, 108144. 10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders EB-N, & Stappers PJ (2008). Co-creation and the new landscapes of design. CoDesign, 4, 5–18. 10.1080/15710880701875068 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders J, Midgette G, Taylor J, & Faraji S-L (2021). A hidden cost of convenience: Disparate impacts of a program to reduce burden on probation officers and participants. Criminology & Public Policy, 20, 71–122. 10.1111/1745-9133.12534 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwalbe CS (2012). Toward an integrated theory of probation. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 39, 185–201. 10.1177/0093854811430185 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz RG (2018). A 21st century developmentally appropriate juvenile probation approach. Juvenile and Family Court Journal, 69, 41–54. 10.1111/jfcj.12108 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sheidow AJ, McCart MR, Chapman JE, & Drazdowski TK (2020). Capacity of juvenile probation officers in low-resourced, rural settings to deliver evidence-based substance use intervention to adolescents. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 34, 76–88. 10.1037/adb0000497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skeem JL, & Manchak S (2008). Back to the future: From Klockars’ model of effective supervision to evidence-based practice in probation. Juvenile and Family Court Journal, 69, 41–54. 10.1080/10509670802134069 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith H, Rodriguez N, & Zatz MS (2009). Race, ethnicity, class, and noncompliance with juvenile court supervision. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 623, 108–120. 10.1177/0002716208330488 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmetz KF, & Anderson JO (2016). A probation profanation: Race, ethnicity, and probation in a Midwestern Sample. Race and Justice, 6, 325–349. 10.1177/2153368715619656 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thoemmes F, & Ong AD (2016). A primer on inverse probability of treatment weighting and marginal structural models. Emerging Adulthood, 4, 40–59. 10.1177/2167696815621645 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Torbet PM (2008). Building Pennsylvania’s comprehensive aftercare model: Probation case management essentials for youth in placement https://www.pccd.pa.gov/Juvenile-Justice/Documents/Probation%20Case%20Management%20Essentials.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Trotman AJ, & Taxman FS (2011). Implementation of a contingency management-based intervention in a community supervision setting: Clinical issues and recommendations. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 50, 235–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuell JA, Heldman J, & Harp K (2017). Developmental reform in juvenile justice: Translating the science of adolescent development to sustainable best practice https://rfknrcjj.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Developmental_Reform_in_Juvenile_Justice_RFKNRCJJ.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Walker SC, Bishop AS, Catena J, & Haumann E (2017). Deploying street outreach workers to reduce failure to appear in juvenile court for youth of color: A randomized study. Crime & Delinquency, 65, 1740–1762. 10.1177/0011128717739567 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walker SC, Valencia E, Miller S, Pearson K, Jewell C, Tran J, & Thompson A (2020). Developmentally-grounded approaches to juvenile probation practice: A case study. Federal Probation, 83, 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf R, Morrison J, Inns A, Slavin R, & Risman K (2020). Average effect sizes in developer-commissioned and independent evaluations. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 13, 428–447. 10.1080/19345747.2020.1726537 [DOI] [Google Scholar]