Abstract

Shift work is an integral part of living in a 24-hour society. However, shift work can disrupt circadian rhythms, negatively impacting health. Guided by the Stress Process Model (SPM), this study examines the association between shift work and depressive symptoms and investigates whether sleep health (duration, quality, and latency) mediates this relationship among midlife adults. Utilizing data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979 cohort (N = 6,372), findings show that working evening, night, and irregular shifts is associated with increased depressive symptoms. The results also show that part of the association between shift work and depressive symptoms among night and irregular shift workers, is indirect, operating through short sleep during the week and on the weekend. Although shift work can negatively affect mental health, getting more restorative sleep may mitigate part of the harmful mental health consequences of non-standard work schedules.

Keywords: shift work, sleep, depressive symptoms, stress process

Shift work is an integral part of living in a 24-hour society due to increased demand for round-the-clock service. From 2017 to 2018, approximately 16 percent of wage and salary workers in the United States engaged in shift work (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics [BLS] 2019). Shift work occurs outside standard daily work hours, typically between 8 to 9 a.m. and 5 to 6 p.m. (Brown et al. 2020; Costa 2016; Vogel et al. 2012). Covering the entire 24 hours through the alternation of separate groups of workers, shift work refers to evening and night shifts, rotating and split shifts, and irregular schedules (Åkerstedt et al. 2019; BLS 2019). While various industries benefit from non-standard schedules, shift work can have deleterious consequences for health, including increased risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD), diabetes, obesity, metabolic syndrome, substance abuse, and depressed mood (Brown et al. 2020; Kulkarni, Schow, and Shubrook 2020; Park, Suh, and Lee 2019; Takahashi 2014).

Shift work is particularly detrimental to physiological processes that follow a 24-hour rhythm of the body (i.e., circadian rhythm). Circadian rhythms evolve in response to a light-dark cycle established by sunrise and sunset, along with the daily rhythm of other external factors, such as temperature and noise (Kulkarni et al. 2020). Disruption to circadian rhythms is associated with a variety of pathophysiological processes like depressive symptoms, whereby severity is correlated with the degree of circadian misalignment (Courtet and Olié 2012). Moreover, shift work can negatively affect sleep, which is regulated by circadian rhythms.

Sleep health, which refers to the multidimensional nature of sleep that includes duration, efficiency, timing, alertness, and satisfaction/quality (Buysse 2014; Hale, Troxel, and Buysse 2020), is susceptible to changes in circadian rhythms. Engaging in shift work disrupts the normal sleep-wake cycle because it requires workers to sleep during normal waking hours and work during normal sleep periods for the human body (Hale 2005; Pandi-Perumal et al. 2020). The association between shift work and sleep involves quantitative and qualitative aspects of sleep reduction, disturbed sleep, and altered sleep quality (Åkerstedt et al. 2008). Non-standard work schedules are associated with short sleep, excessive fatigue, increased sleep disturbance, difficulty falling asleep, and insomnia (Åkerstedt 2008; Kecklund and Axelsson 2016; Vallières et al. 2014). Shift workers also have more difficulty establishing a regular sleep schedule compared with non-shift workers (Burgard and Ailshire 2009; Flo et al. 2013; Yong, Li, and Calvert 2017).

Although shift work can negatively impact sleep, it is important to note that poor sleep has independent effects on mental and physical health. For example, short sleep is associated with increased risk for CVD, diabetes, and obesity (Åkerstedt et al. 2019; Buxton and Marcelli 2010; Grandner et al. 2010; Jackson, Redline, and Emmons 2015). Sleep disorders such as insomnia, which affects about 40 percent of Americans, are also associated with depressed mood, anxiety, and increased risk for mortality (Leggett, Sonnega, and Lohman 2018). Finally, sleep latency (i.e., the time it takes to fall asleep), which averages around 10 to 20 minutes, can help indicate whether an individual is getting quality sleep (Sleep Foundation 2021).

Despite evidence that there is an association between shift work and depressive symptoms, few studies examine this relationship among midlife adults. There is evidence that depressive symptoms decline during midlife (Clarke et al. 2011; Mirowsky and Ross 1992; Sinkewicz et al. 2022). However, engaging in shift work may increase depressive symptoms during this stage of the life course due to being out of sync with society, which primarily follows a daytime schedule. Considering the increasing complexities of social role demands and expectations during midlife (Lachman 2015), engaging in shift work can be disruptive to work-life balance, thus giving rise to not only depressive symptoms but also poor sleep. As such, this study examines the association between shift work and depressive symptoms and investigates whether sleep health is a mechanism that explains this relationship.

BACKGROUND

Shift Work: A Chronic Stressor

The stress process model (SPM) is the guiding theoretical framework for this study (Pearlin et al. 1981). Consisting of stressors, psychosocial resources (i.e., mediators and moderators), and outcomes, the SPM can provide insight about specific mechanisms that help explain the causal pathway between stressors and health outcomes. In the context of SPM, stressors can be acute (e.g., negative life events) or chronic. Chronic stressors are ongoing or recurrent in nature and require individuals to adapt over a prolonged period of time (Wheaton et al. 2013). Shift work is a chronic stressor because it can cause long-term changes to both physiological and social processes.

Physiologically, shift workers must adjust to changes in numerous biological processes that are regulated by the body’s circadian rhythm (i.e., biological clock). Disruptions to the circadian rhythm as a result of shift work can lead to poor health, due to fluctuations in the normal sleep/wake cycle (i.e., sleep during the day and working at night) (Costa 2010). Shift work can also increase levels of cortisol, a stress hormone that has a distinct rhythm where levels are high in the early morning and low in the evenings (Herichova 2013). Thus, shift workers who sleep during the day can experience increased cortisol secretion that diminishes sleep quality (Niu et al. 2011). Moreover, Mai, Jacobs, and Schieman (2019) found that shift workers from Europe with physical health problems experienced higher levels of subjective job precarity and were more likely to report sleep disturbances. In general, compared with day workers, shift workers experience more instances of short sleep, reduced sleep quality, and insomnia symptoms (Boivin and Boudreau 2014); they also frequently complain of irritability, nervousness, and anxiety (Costa 2016).

Socially, shift work is a chronic stressor because it can interfere with family and social life. Shift workers are frequently out of phase with society because part of the shared reality of American life is the understanding that normal hours for paid work are daytime hours (Costa 2016; Dunham 1977). This idea is supported and reinforced by a variety of institutions. For example, most communities are oriented to support day schedules, which is reflected in the fact that businesses, schools, and other facilities (e.g., recreational, medical, social) are primarily available during the hours of 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. (Costa 2016; Dunham 1977). Consequently, shift work can lead to diminished integration into society as well as social marginalization due to an inability to engage in typical community activities and responsibilities in the home (Costa 2016; Vogel et al. 2012).

Compared with non-shift workers, workers with non-standard schedules are more likely to be dissatisfied with work-life balance, spend less time with family, experience more conflict in the home, and are more likely to experience role overload (i.e., difficulty meeting demands and responsibilities of multiple social roles) (Hendrix 2016; Perry-Jenkins et al. 2007; Tuttle and Garr 2012; Williams 2008; Wöhrmann, Müller, and Ewert 2020). Low integration in society and difficulties with work-life balance are chronic stressors that can impact shift workers’ mental and physical health. The inability to meet role responsibilities and obligations due to shift work may be particularly detrimental for midlife adults who are expected, at this stage of the life course, to have more experience dealing with stress as well as maintaining work-life balance (Lachman 2015).

The Mediating Role of Sleep

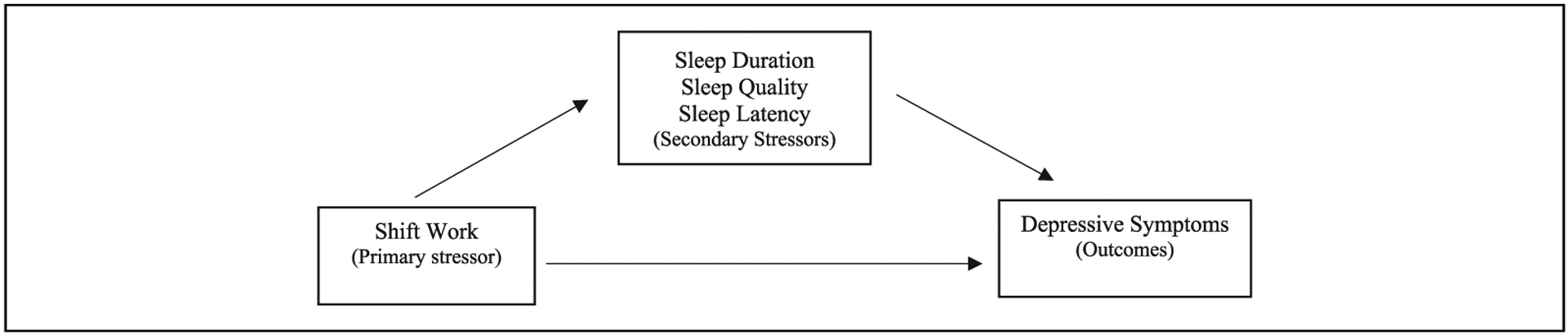

Within the stress process framework, stressors are also characterized as primary or secondary. Primary stressors represent the initial event that induces a stress response, while secondary stressors emerge from primary stress (Pearlin and Bierman 2013). Secondary stressors can represent mediating pathways that connect primary stressors to outcomes. For example, shift work is a primary, chronic stressor that can disrupt biological processes (i.e., circadian rhythm), which can increase the risk of poor sleep health. As such, reduced sleep duration, poor sleep quality, and increased sleep latency are secondary stressors that can arise from engaging in shift work, which in turn operate as mediating pathways by which shift work affects mental health. Figure 1 displays a conceptual representation.

Figure 1.

Conceptual diagram of the relationship between shift work, sleep health, and depressive symptoms within the stress process framework.

There is evidence that sleep can be a mechanism that explains various biopsychosocial pathways to health outcomes. For example, using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality index, Uchino et al. (2019) found that sleep quality mediated the association between self-rated health and inflammatory markers. Research also shows that disturbed sleep mediated the association between low network support and myocardial infarction in women (Nordin, Knutsson, and Sundbom 2008). Different dimensions of sleep are shown to be mediators when examining the association between work-related factors and mental health. For instance, Nakata (2011) found that the association between longer work hours and depressive symptoms was mediated by sleep deprivation, instead of a direct link to work schedules. Sleep quality also mediated the association between working the night shift and health-related quality of life (Lim et al. 2020). In a study among South Korean shift workers, Park et al. (2019) found that sleep quality mediated the association between working during the day and depressive symptoms compared with non-day workers. Although these studies provide evidence for sleep as a mechanism that can help explain the association between different work-related factors and well-being outcomes, they are limited in their inclusion of only one indicator of sleep (e.g., sleep quality, sleep deprivation), there is a lack of attention to multiple types of shift work, and the studies utilize localized, non-generalizable populations. The current study addresses these gaps.

Shift Work, Sleep, and Depressive Symptoms

Outcomes are the final component of the stress process model and refer to various health consequences or manifestations of stress (Pearlin et al. 1981). Depressive symptoms is the outcome for this study. Depressed mood is associated with abnormal circadian activity, and evidence suggests that the mechanisms involved in the regulation of the sleep-wake cycle overlap with those of depression (Moulton, Pickup, and Ismail 2015). However, while there is an established link between circadian disruption and shift work, evidence of the association between shift work and depressive symptoms is mixed. On one hand, research shows that shift work does not have a substantial impact on depressed mood (Driesen et al. 2011; Goodrich and Weaver 1998). However, it is important to note that Driesen et al. (2011) found a gendered effect such that only male shift workers over the age of 45 had a higher risk of developing depressed mood compared with male non-shift workers of the same age. On the other hand, other studies show that depressive symptoms are higher among shift workers compared with non-shift workers (Lee et al. 2016; Park et al. 2019; Perry-Jenkins et al. 2007). Likewise, Holst et al. (2021) found that police officers in Buffalo, New York, working evening and night shifts had higher odds of depressive symptoms compared with police officers working during the day. Although not specifically related to depressive symptoms, Cho (2018) found that workers with non-standard shifts had more days of poor mental health than standard day workers.

While studies show that short sleep and sleep quality is associated with depression and depressive symptoms (Pandi-Perumal et al. 2020; Pandi-Perumal et al. 2009), the explanation of this association is equivocal. One explanation for the association between sleep and depressed mood focuses on disruption to circadian rhythms, while another explanation posits reciprocal effects between poor sleep and depressed mood (Pandi-Perumal et al. 2009). Few studies confirmed these explanations. However, in a simulation study, Rosenström et al. (2012) found that for minor depression, sleep problems caused more dysphoria than dysphoria caused sleep problems. The authors conclude that while sleep problems precede depression in time, there is still a reciprocal relationship between the two (Rosenström et al. 2012). A similar bidirectional pathway is postulated for the association between insomnia and depression such that while insomnia is a typical symptom of depression, it may also be an independent risk factor for depression (Pandi-Perumal et al. 2020). In short, there remains ambiguity regarding the depressive symptoms—sleep health connection. However, considering that there is ample evidence that depression is low during midlife (Clarke et al. 2011; Mirowsky and Ross 1992; Sinkewicz et al. 2022), and respondents in this sample are age 50 on average, Figure 1 conveys the model specification utilized in this study.

The Current Study

Shift work is a chronic stressor that can affect health, primarily due to disruptions to circadian rhythms. Although evidence shows that shift work can lead to poor sleep and poor sleep, in turn, may be associated with diminished mental health, this study aims to better understand the association between shift work and depressive symptoms and to determine what role, if any, sleep health plays in this relationship. The following research questions are examined: (1) What is the association between shift work and sleep health (duration, quality, latency); (2) Is shift work and sleep health associated with depressive symptoms; and (3) Does sleep health mediate the relationship between shift work and depressive symptoms?

DATA AND METHODS

Sample

Data for this study are from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979 cohort (NLSY-79). The NLSY-79 is a nationally representative sample of non-institutionalized Americans. The BLS sponsored data collection, and it is managed by the Center for Human Resource Research (CHRR) at The Ohio State University. The original sample consists of 12,686 respondents aged 14 to 22. African Americans, Hispanics, and economically disadvantaged Whites were over-sampled. The NLSY-79 includes measures of labor force participation, demographic factors, family life, health, and cognitive and behavioral functioning. Data were collected annually from 1979 to 1994 and biennially thereafter.

NLSY-79 researchers conducted a health assessment when respondents turned or were close to age 50. The assessment asked detailed questions about mental health, chronic physical health conditions, and health care utilization. Questions pertaining to sleep and depressive symptoms were also asked during the age 50 health assessment, which was administered in 2008, 2010, 2012, 2014, and 2016. All study variables are from the year that respondents completed the age 50 health module. Although the NLSY-79 is a longitudinal data set, the current study is a pooled cross-sectional analysis because respondents were asked sleep questions once. Respondents were deleted if they were missing (valid skips) on any questions related to shift work, depressive symptoms, and sleep health. About 15 percent of the sample had missing information on income. To preserve sample size, multiple imputation was used, leading to a final sample size of 6,372.

Dependent Measure

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms is assessed using a seven-item version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), which is a reliable index of depressive symptomology (Levine 2013). Respondents were asked, often in the past week did you: (1) not feel like eating; (2) have trouble keeping your mind on what you were doing; (3) feel depressed; (4) feel everything was an effort; (5) experience restless sleep; (6) feel sad; and (7) feel like you could not get going.”

The responses ranged from 0 (rarely/none of the time) to 3 (most/all of the time). Item 5, which is the sleep-related question, was removed to reduce multicollinearity with sleep health measures. The remaining six items were summed to create a scale that ranged from 0 to 18. Higher values indicate more depressive symptoms. The Cronbach’s alpha is .80, and depressive symptoms is logged in all analyses to correct for skewness.

Independent Measures

Shift work

Shift work is assessed based on respondents’ answer to the question: “At your current job do you usually work a regular daytime schedule or some other schedule?” If respondents answered, “some other schedule,” they were asked to specify the particular shift. As such, a categorical variable comprising day shift (reference), evening shift (1 = yes), night shift (1 = yes), rotating shift (1 = yes), and irregular shift (1 = yes) was created. Secondary stressors (i.e., mediators) include sleep duration, insomnia symptoms, and sleep latency.

Sleep duration

Sleep duration is measured with the following questions, (1) “How much sleep (i.e., hours) do you get on weekdays/workdays?” and (2) “How much sleep (i.e., hours) do you get on weekends/non-workdays?” Based on the National Sleep Foundation’s recommendation for optimal sleep (e.g., 7–9 hours), a binary variable of short sleep (<7 hours) and the reference category “normal” sleep (7 or more hours) was created (Ojile 2017). Due to a lack of respondents indicating sleeping more than nine hours for both sleep measures and theoretical framing, no category for long sleep was created. Insomnia symptoms is assessed with four questions: (1) “How often do you have trouble falling asleep”; (2) “How often do you wake up during the night and have trouble falling back asleep”; (3) “How often do you wake up too early in the morning and are unable to get back to sleep”; and (4) “How often do you feel unrested during the day no matter how many hours of sleep you’ve had?” Responses ranged from (1) almost always, (2) often, (3) sometimes, and (4) rarely or never. A binary measure was created by combining items 1, 2, and 3 to indicate symptoms of insomnia and category 4 represented no insomnia symptoms (reference). Finally, sleep latency (i.e., the time it takes to fall asleep) was measured as 0 to 29 minutes (reference) and 30 to 60 minutes.

Covariates

To limit confounding for both independent and dependent variables, the analysis adjusts for a range of factors such as gender, race/ethnicity, age, marital status, parenthood, caregiving, education, income, and self-rated health. Gender is measured as female (1 = yes) and male (reference). Race/ethnicity is a three-category variable that consists of Black (1 = yes), Hispanic (1 = yes), and White (reference). Marital status is coded as married (1 = yes) and not married (reference), while parenthood is a binary variable consisting of parent (1 = yes) and non-parents (reference). Caregiving (1 = yes) is assessed by respondents indicating whether they are caregivers for a house-hold member or a friend living outside the home; the reference group is non-caregivers. Education is a categorical variable comprising less than high school (reference), high school degree, and college (1 or more years). Income is measured in thousands of dollars and is logged to correct for skewness. Finally, self-rated health is a scale that ranges from 1 to 5; respondents were asked: “In general would you say your health is (1) excellent, (2) very good, (3) good, (4) fair, and (5) poor.” A binary measure of good self-rated health (comprising items 1, 2, and 3) and poor self-rated health (comprising items 4 and 5) was created; good self-rated health is the reference category.

Analytic Strategy

First, to preserve sample size, multiple imputation was used to handle missing information on income. Values were imputed using the MI procedure in Stata 17 and 20 MI data sets were imputed. Second, descriptive statistics were obtained for the study sample (Table 1). Next, to determine whether poor sleep health is a secondary stressor that may arise from shift work, logistic regression models were estimated (Table 2). Fourth, ordinary least squares regression was utilized to assess the association between shift work, sleep health, and depressive symptoms (Table 3). Models 1 through 5 estimate the effects of shift work and sleep separately. Model 6 contains all study variables, and study conclusions are drawn from the full model. Finally, the mediation analysis was conducted using sgmediation2, which calculates three different tests of mediation (Sobel, Aroian, and Goodman) using the “product of coefficients” approach (MacKinnon et al. 2002; Mize, n.d.). All analyses are weighted.

Table 1.

Means, Percentages, and Confidence Intervals (CIs) for All Study Variables.

| Study variables | Mean/percent | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent variables | ||

| Depressive symptoms 0 (low) to 18 (high) | 2.47 | [2.38, 2.55] |

| Depressive symptoms (logged) | .86 | [0.84, 0.88] |

| Shift work | ||

| Day | 80.27% | — |

| Evening | 3.28% | — |

| Night | 4.17% | — |

| Rotating | 4.41% | — |

| Irregular | 7.86% | — |

| Sleep health (mediators) | ||

| Short sleep weekdays (⩽6 hours) | 44.84% | — |

| Short sleep weekdays (≥7 hours) | 55.16% | — |

| Short sleep weekend (⩽6 hours) | 27.15% | — |

| Short sleep weekend (≥7 hours) | 72.85% | — |

| Insomnia symptoms (1 = yes) | 66.71% | — |

| Insomnia symptoms (0 = no) | 33.29% | — |

| Sleep latency (30–60 minutes) | 22.13% | — |

| Sleep latency (0–29 minutes) | 77.87% | — |

| Control variables | ||

| Women | 49.92% | — |

| Men | 50.08% | — |

| Black | 29.36% | — |

| Hispanic | 18.86% | — |

| White | 51.77% | — |

| Age | 50.29 | [50.26, 50.32] |

| Married | 58.54% | — |

| Not married | 41.46% | — |

| Parents | 81.84% | |

| Non-parents | 18.16% | |

| Caregiver | 9.67% | |

| Non-caregiver | 90.33% | |

| Less than high school degree | 7.49% | — |

| High school degree | 41.51% | — |

| College (1 or more years) | 51.00% | — |

| Income (logged) | 10.75 | [10.71, 10.80] |

| Poor self-rated health | 14.31% | — |

| Good self-rated health | 85.69% | — |

Note. NLSY-79 Cohort, (N = 6372).

Table 2.

Logistic Regression Estimating the Association between Shift Work and Sleep, NLSY-79 Cohort (N = 6,372).

| Short sleep weekday | Short sleep weekend | Insomnia symptoms | Sleep latency | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratios | 95% CI | Odds ratios | 95% CI | Odds ratios | 95% CI | Odds ratios | 95% CI | |

| Shift | ||||||||

| Evening | 0.97 | [0.68, 1.38] | 1.05 | [0.70, 1.57] | 1.04 | [0.73, 1.50] | 0.87 | [0.58, 1.31] |

| Night | 2.19*** | [1.57, 3.03] | 1.34 | [0.96, 1.87] | .93 | [0.67, 1.29] | 1.03 | [0.71, 1.51] |

| Rotating | 1.20 | [0.89, 1.61] | 1.06 | [0.76, 1.48] | 1.08 | [0.78, 1.50] | 0.99 | [0.69, 1.41] |

| Irregular | 1.46** | [1.18, 1.82] | 1.64*** | [1.29, 2.07] | 1.18 | [0.92, 1.50] | 0.74* | [0.56, .99] |

Note. All models control for gender, race-ethnicity, marital status, age, education, parenthood, care giver status, income, and self-rated health. CI = confidence interval.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001 (two-tailed tests).

Table 3.

Depressive Symptoms Regressed on Study Variables NLSY-79 Cohort (N = 6,372).

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | B | SE | b | SE | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | |

| Shift work | ||||||||||||

| Eveninga | .166* | .07 | .167* | .07 | .164* | .07 | .162* | .07 | .169* | .07 | .164* | .07 |

| Nighta | .132* | .06 | .094 | .06 | .118 | .06 | .139* | .06 | .131* | .06 | .117* | .06 |

| Rotatinga | −.017 | .06 | −.026 | .06 | −.019 | .06 | −.023 | .06 | −.017 | .06 | −.027 | .05 |

| Irregulara | .136** | .04 | .118** | .04 | .115** | .04 | .123** | .04 | .143** | .04 | .109** | .04 |

| Sleep health | ||||||||||||

| Short sleep weekdayb (⩽6 hours) | .202*** | .02 | .078** | .03 | ||||||||

| Short sleep weekendsc (⩽6 hours) | .233*** | .03 | .116*** | .03 | ||||||||

| Insomnia symptomsd | .441*** | .02 | .404*** | .02 | ||||||||

| Sleep latencye (30–60 minutes) | .135*** | .03 | .075** | .03 | ||||||||

| Controls | ||||||||||||

| Womenf | .250*** | .02 | .256*** | .02 | .254*** | .02 | .192*** | .02 | .245*** | .02 | .198*** | .02 |

| Blackg | −.036 | .03 | −.062* | .03 | −.064* | .03 | −.013 | .03 | −.045 | .03 | −.044 | .03 |

| Hispanicg | −.110*** | .03 | −.114** | .03 | −.114** | .03 | −.072* | .03 | −.112** | .03 | −.080** | .03 |

| Age | −.018 | .01 | −.020* | .01 | −.020* | .01 | −.017 | .01 | −.018 | .01 | −.019 | .01 |

| Marriedh | −.142*** | .03 | −.136*** | .03 | −.131*** | .03 | −.136*** | .03 | −.141*** | .03 | −.128*** | .03 |

| Parenti | .077* | .03 | .029* | .03 | .070* | .03 | .080** | .03 | .083** | .03 | .077** | .03 |

| Caregiverj | .164*** | .04 | .156*** | .04 | .157*** | .04 | .162*** | .04 | .171*** | .04 | .159*** | .04 |

| High school degreek | −.137* | .05 | −.130* | .05 | −.130* | .05 | −.116* | .05 | −.140** | .05 | −.113* | .05 |

| Collegek | −.167** | .05 | −.154** | .05 | −.145** | .05 | −.146** | .05 | −.168** | .05 | −.131* | .05 |

| Income (logged) | −.040*** | .01 | −.041*** | .01 | −.039*** | .01 | −.039*** | .01 | −.041*** | .01 | −.040*** | .01 |

| Poor self−rated healthl | .603*** | .04 | .573*** | .04 | .565*** | .04 | .524*** | .04 | .595*** | .04 | .496*** | .04 |

| Constant | 2.15*** | .53 | 2.20*** | .52 | 2.18*** | .53 | 1.81*** | .51 | 2.13*** | .53 | 1.86*** | .51 |

| R 2 | .13 | .14 | .14 | .18 | .13 | .19 | ||||||

Working during day (reference).

Seven or more hours sleep during week (reference).

Seven or more hours sleep on the weekend (reference).

No insomnia symptoms (reference).

Sleep latency 0 to 29 minutes (reference).

Men (reference).

White (reference).

Not married (reference).

Non-parents.

Non-caregiver.

Less than high school degree (reference).

Good health (reference).

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001 (two-tailed tests).

RESULTS

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics for the study sample. The average for depressive symptoms is 2.47. Around 80.27 percent of the sample worked days, 3.28 percent evenings, 4.17 percent nights, 4.41 percent rotating shift, and 7.86 percent worked an irregular shift. With regard to sleep health, 44.84 and 27.15 percent of respondents get six or less hours of sleep (i.e., short sleep) during the week and on the weekend, respectively. Insomnia symptoms are experienced by 66.71 percent of the sample, and 22.13 percent of respondents report increased sleep latency of 30 to 60 minutes. The sample is 49.92 percent women, 29.36 percent Black, and 18.86 percent Hispanic. The average age is 50 years, and 58.54 percent are married. Around 81.84 percent of respondents are parents and 9.67 percent are caregivers. Educationally, 7.49 percent have less than a high school degree, 41.51 percent have a high school degree, and 51 percent of respondents attended one or more years of college. Logged income is 10.93 and about 14.31 percent of the sample report poor self-rated health.

The results of the logistic regression analysis of the association between shift work and sleep health are displayed in Table 2. The findings show that working nights and irregular shifts, compared with working the day shift, increased the odds of short sleep during the week by a factor of 2.19 and 1.46, respectively. While irregular shift work, relative to working during the day, increased the odds of short sleep on the weekend by a factor of 1.64, it reduced the odds of sleep latency (i.e., taking longer to fall asleep) by a factor of .74. There were no significant findings for the association between shift work and symptoms of insomnia.

Table 3 displays the results of the direct effects of shift work and sleep health on depressive symptoms. In Model 1, working evenings (b = .166, p <.05), nights (b = .132, p <.05), and irregular shifts (b = .136, p <.01) is associated with increased depressive symptoms compared with working a day shift. Measures related to sleep health are added in Models 2, 3, 4, and 5. Across these models, short sleep during the week (b = .202, p <.001), short sleep on the weekend (b = .233, p <.001), insomnia symptoms (b = .441, p <.001), and sleep latency (b = .135, p <.001) are all associated with increased depressive symptoms compared with respondents who get normal sleep during the week and on the weekend, have no insomnia symptoms, and fall asleep within 0 to 30 minutes, respectively.

Model 6 is the full model that includes all study variables. Compared with working during the day, evenings (b = .164, p <.05), nights (b = .117, p <.05), and irregular shifts (b = .109, p <.01) are associated with increased depressive symptoms. All sleep health variables remain significant and positively associated with the outcome measure. The results from several covariates are worth noting. Compared with men, women experience increased depressive symptoms, which is consistent with prior research. Moreover, across all models, Hispanics experience reduced depressive symptoms compared with Whites. Marriage, increased education, and income are all inversely associated with depressive symptoms. However, respondents who are parents, caregivers, or who report poor self-rated health experience increased depressive symptoms compared with those who are non-parents, non-caregivers, and respondents reporting good self-rated health, respectively. Sensitivity analyses show that continuous measures of sleep duration, insomnia symptoms, and sleep latency produce similar results.

Turning to the mediation analysis, Table 4 shows coefficients for indirect, direct, and total effects for each mediator estimated separately, adjusting for all study covariates. Mediation was determined based on statistical significance (p value <.05) from the Sobel, Aroian, and Goodman tests of mediation produced in sgmediation2 (not shown). The proportion mediated is calculated by dividing the indirect effect by the total effect; moreover, it captures the effect of shift work on depressive symptoms due to the indirect effect of sleep health. The findings show that the association between working a night shift and depressive symptoms is mediated by short sleep during the week (Proportion mediated 32 percent). The association between working an irregular shift and depressive symptoms is mediated by short sleep during the week (Proportion mediation 13 percent) as well as short sleep on the weekend (Proportion mediated 17 percent). Table 4 also shows that the relationship between irregular shift work and depressive symptoms is mediated by sleep latency (Proportion mediation −5 percent). However, it is important to note that this finding is not indicative of mediation. Specifically, the −5 percent proportion mediated is evidence of inconsistent mediation and/or suppression (MacKinnon, Krull, and Lockwood 2000). Inconsistent mediation occurs when at least one mediated effect has a different sign than the direct effect in the model (MacKinnon et al. 2000). Thus, as shown in Table 4, the indirect effect is negative (−.005), while the direct effect is positive (.134). Furthermore, in Table 3, when sleep latency is added to Model 5, the coefficient for irregular shift increases (.136 to .143), which is indicative of suppression. Although the coefficient for irregular shift is reduced in the full model (.136 to .109), the results from the mediation analysis (i.e., opposite signs of indirect and direct effects) provide additional evidence for inconsistent mediation. In short, despite the −.5 percent proportion mediated, there is technically no “true” mediating effects due to inconsistent mediation/suppression.

Table 4.

Mediation Analysis.

| Effect | Evening | Night | Rotating | Irregular | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | SE | Coefficient | SE | Coefficient | SE | Coefficient | SE | ||

| Short sleep weeknight | id | −.005 | .01 | .036*** | .01 | .006 | .01 | .017** | .01 |

| de | .154* | .07 | .078 | .06 | −.043 | .06 | .111* | .04 | |

| te | .149 | .07 | .114 | .06 | −.037 | .06 | .128** | .05 | |

| Proportion mediated | N.S. | 32% | N.S. | 13% | |||||

| Short sleep weekend | id | −.001 | .01 | .011 | .01 | −.000 | .01 | .021** | .01 |

| de | .150* | .07 | .103 | .06 | −.037 | .06 | .106* | .04 | |

| te | .149* | .07 | .114 | .06 | −.037 | .06 | .128** | .04 | |

| Proportion mediated | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | 17% | |||||

| Insomnia symptoms | id | .003 | .02 | −.009 | .02 | .006 | .02 | .014 | .01 |

| de | .146* | .07 | .123* | .06 | −.043 | .06 | 114** | .04 | |

| te | .149* | .07 | .114 | .06 | −.037 | .06 | .128** | .04 | |

| Proportion mediated | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | |||||

| Sleep latency | id | −.002 | .01 | .001 | .00 | .000 | .00 | −.005* | .00 |

| de | .151* | .07 | .113 | .06 | −.038 | .06 | .134** | .04 | |

| te | .149* | .07 | .114 | .06 | −.037 | .06 | .128** | .04 | |

| Proportion mediated | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | |||||

Note. NLSY-79 Cohort, (N = 6,372). id = indirect effect; de = direct effect; te = total effect; N.S. = not significant; Proportion mediated = indirect effect (id)/total effect (te).

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001 (two-tailed tests).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

The rise of the 24-hour society has reshaped the timing of work, and shift work is an integral part of labor force participation for some adults. However, engaging in shift work can be stressful, resulting in negative consequences for both mental and physical health. Poor mental health arising from shift work may be due to an inability to engage in society, which primarily operates on a daytime schedule, as well as difficulty meeting midlife social role demands and expectations. Physically, shift work can disrupt circadian rhythms, which has deleterious effects on sleep. Guided by the stress process model (SPM), this study examines the association between shift work and depressive symptoms and investigates whether sleep health is a mediating factor in this relationship.

In the context of the SPM, one goal of this study was to determine whether poor sleep health is a secondary stressor that arises from shift work—the primary stressor. The findings reveal that the association between shift work and sleep health depends on the particular shift and dimension of sleep considered. For example, working nights and irregular shifts increase the odds of short sleep duration during the week and on the weekend, respectively. These findings support previous research regarding the detrimental effects of night and irregular shift work (Åkerstedt 2003; Sallinen et al. 2003). There is also evidence that working an irregular shift is associated with decreased odds of sleep latency (i.e., the time it takes to fall asleep). Although this result seemingly indicates that working an irregular shift is “helpful” in terms of the time it takes to fall asleep, this finding may be a sign of fatigue and/or sleep deprivation among irregular shift workers (Hossain et al. 2003). Specifically, the unpredictable nature of irregular shift work can make it difficult to get restorative sleep.

The second goal was to examine whether shift work and sleep health are associated with depressive symptoms. First, the results show that working evenings, nights, and irregular shifts is associated with increased depressive symptoms compared with working a day shift. Second, there is evidence that midlife adults who report short sleep during the week and on the weekend, insomnia symptoms, and increased sleep latency experience more depressive symptoms compared with individuals with better sleep health. These findings hold in the full model when all study variables are added, which suggests that shift work, with the exception of rotating shifts, and sleep health (duration, quality, and latency) are independently and directly associated with increased depressive symptoms.

Finally, I examined whether sleep health mediates the relationship between shift work and depressive symptoms. The mediation analysis yielded limited results. However, there is evidence that short sleep during the week partially mediates 32 and 17 percent of the association between working nights, irregular shifts, and depressive symptoms, respectively. Moreover, short sleep on the weekend also mediates 17 percent of the association between irregular shift work and depressive symptoms. Thus, while midlife adults in this sample experience worse mental health from participating in shift work, part of this effect is indirect, operating through diminished sleep (i.e., short sleep duration).

The mediating effects of short sleep duration during the week and on the weekend may be due to the following factors. First, there is an abundance of research that shows a strong connection between working nights and circadian rhythm disruption. Consequently, short sleep duration may occur because workers are trying to sleep when the body’s biological clock is signaling that they should be awake. Next, although there is no definitive answer about whether there is a reciprocal relationship between sleep and depressed mood, there is evidence that short sleep may increase the risk for depressive symptoms during midlife (Li et al. 2017). Finally, irregular shift workers may have low schedule control and/or lack autonomy, which are stressful workplace conditions that may increase depressive symptoms as well as make it difficult to develop good sleep hygiene (e.g., a regular sleep schedule) (Costa 2020; Hendrix 2016; Theorell et al. 2015).

Taken together, these results suggest that engaging in shift work, compared with working a day shift, is detrimental for depressive symptoms during midlife. This may be due to an inability to meet family and caregiving responsibilities as well as be active in the community. For example, research shows that workers with non-standard schedules are more likely to report negative effects on family life, marital quality, parent-child interactions, and lower levels of community participation than their day shift counter-parts (Perrucci et al. 2007; Perry-Jenkins et al. 2007; Strazdins et al. 2006). Furthermore, the stress of shift work may be particularly detrimental for midlife adults who comprise the study sample. Midlife is a stage of the life course where health may begin to decline, there may be increased economic burdens, and adults may experience increased care giving responsibilities for both children and aging parents. (Bierman 2021). As such, engaging in evening shift work could make meeting these demands more difficult, which can lead to increased depressive symptoms.

This study is not without limitations. First, the reliance on self-reported measures of sleep may be subject to recall bias. While self-reports of sleep quantity and quality are reliable and valid measures, there can also be biases due to a person’s mood, memory, and personal characteristics (Krystal and Edinger 2008). Utilizing objective measures of sleep from actigraphy can minimize potential measurement biases stemming from self-reports (Morgenthaler et al. 2007). Moreover, questions related to sleep duration in the NLSY-79 ask how much sleep people get on their workdays/weeknights and non-workdays/weekends, which assumes that people do not work on the weekends. Second, this study does not capture the reasons why people engage in shift work. While people may engage in shift work because it is the only option available, some people voluntarily work non-standard schedules to help with childcare costs and to achieve work-life balance (Hendrix 2016; Wöhrmann et al. 2020). Future research should incorporate more qualitative methodologies to investigate people’s motivation for engaging in shift work. Finally, due to the cross-sectional data utilized in this study, it is difficult to establish temporal order between depressive symptoms and sleep health. Although prior research suggests bidirectional effects, the association is equivocal. Future research should incorporate longitudinal data to better assess this relationship.

Despite these limitations, this study makes several contributions to the literature. It expands research on the consequences of shift work for depressive symptoms among midlife adults, which is understudied. Midlife is a time of the life course that is often viewed as a “crisis” due to competing demands and/or the onset of physiological changes related to aging or it can be a time where adults possess the necessary resources to deal with life stressors and can successfully balance work and family responsibilities. Thus, it is important to understand how work-related factors, which is a central part of midlife, condition this stage of the life course. Next, unlike previous research that primarily focuses on the consequences of working the night shift, this study investigates several non-standard schedules (e.g., evening, night, rotating, and irregular shifts) and the associated impact on mental health. Examining multiple types of shift work is important because workers may face different health consequences depending on the shift worked. Another important contribution is the incorporation of three measures of sleep health (e.g., duration, quality, and latency). By using the term “sleep health,” this study adds to research that encourages a more holistic view of sleep, rather than focusing on individual symptoms and disorders (Buysse 2014). Finally, unlike previous studies that utilize small localized samples, this study draws from nationally representative data, which helps generalize the findings to the broader population.

In closing, this study reveals that there are mental health consequences associated with working non-standard schedules. In particular, midlife adults working evening, night, and irregular shifts experience increased depressive symptoms compared with day shift workers. In addition, while poor sleep duration during the week and on the weekend only partially mediate the effects of night and irregular shift work on depressive symptoms, the findings suggest that being able to take advantage of the restorative properties of sleep may be beneficial for shift workers. As such, industries that rely on shift work may consider promoting and/or implementing ways to help improve sleep health among workers, which could include providing designated workplace areas for naps, enrolling employees in sleep monitoring programs, or providing onsite education and resources to improve sleep hygiene.

FUNDING

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The Duke Aging Center Postdoctoral Research Training Grant (NIA T32 AG000029) supported this work.

REFERENCES

- Åkerstedt Torbjörn. 2003. “Shift Work and Disturbed Sleep/wakefulness.” Occupational Medicine 53: 89–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Åkerstedt Torbjörn, Ghilotti Francesca, Grotta Alessandra, Zhao Hongwei, Adami Hans-Olov, Trolle-Lagerros Ylva, and Bellocco Rino. 2019. “Sleep Duration and Mortality—Does Weekend Sleep Matter?” Journal of Sleep Research 28:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Åkerstedt Torbjörn, Ingre Michael, Broman Jan-Erik, and Kecklund Göran. 2008. “Disturbed Sleep in Shift Workers, Day Workers, and Insomniacs.” Chronobiology International 25:333–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierman Alex. 2021. “Why Have Sleep Problems in Later-midlife Grown Following the Great Recession? A Comparative Cohort Analysis.” The Journals of Gerontology: Series B 76:1005–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boivin Diane B., and Boudreau Philippe. 2014. “Impacts of Shift Work on Sleep and Circadian Rhythms.” Pathologie Biologie 62:292–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown Jessica P., Martin Destiny, Nagaria Zain, Verceles Avelino C., Jobe Sophia L., and Wickwire Emerson M.. 2020. “Mental Health Consequences of Shift Work: An Updated Review.” Current Psychiatry Reports 22:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgard Sarah A., and Ailshire Jennifer A.. 2009. “Putting Work to Bed: Stressful Experiences on the Job and Sleep Quality.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 50:476–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buxton Orfeu M., and Marcelli Enrico. 2010. “Short and Long Sleep Are Positively Associated with Obesity, Diabetes, Hypertension and Cardiovascular Disease among Adults in the United States.” Social Science and Medicine 71:1027–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buysse Daniel J. 2014. “Sleep Health: Can We Define It? Does It Matter?” Sleep 37:9–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho Youngmin. 2018. “The Effects of Nonstandard Work Schedules on Workers’ Health: A Mediating Role of Work-to-Family Conflict.” International Journal of Social Welfare 27:74–87. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke Philippa, Marshall Victor, House James, and Lantz Paula. 2011. “The Social Structuring of Mental Health over the Adult Life Course: Advancing Theory in the Sociology of Aging.” Social Forces 89: 1287–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa Giovanni. 2010. “Shift Work and Health: Current Problems and Preventive Actions.” Safety and Health at Work 1:112–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa Giovanni. 2016. “Introduction to Problems of Shift work.” Pp. 19–35 in Social and Family Issues in Shift Work and Non-standard Working Hours, edited by Iskra-Golec Irena, Barnes-Farrell Janet, and Bohle Philip. Basel, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Costa Giovanni. 2020. “Shift Work and Occupational Hazards.” Pp. 1–18 in Handbook of Socioeconomic Determinants of Occupational Health: From Macro-level to Micro-level Evidence, edited by Theorell Töres. Edinburgh, UK: Springer Cham. [Google Scholar]

- Courtet Philippe and Olié Emilie. 2012. “Circadian Dimension and Severity of Depression.” European Neuropsychopharmacology 22:S476–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driesen Karolien, Jansen Nicole W. H., van Amelsvoort Ludovic G. P. M., and Kant Ijmert. 2011. “The Mutual Relationship between Shift Work and Depressive Complaints—A Prospective Cohort Study.” Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment and Health 37:402–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunham Randall B. 1977. “Shift Work: A Review and Theoretical Analysis.” Academy of Management Review 2:624–34. [Google Scholar]

- Flo Elisabeth, Pallesen Ståle, Åkerstedt Torbjørn, Magerøy Nils, Moen Bente Elisabeth, Grønli Janne, Nordhus Inger Hilde, and Bjorvatn Bjørn. 2013. “Shift-related Sleep Problems Vary According to Work Schedule.” Occupational and Environmental Medicine 70:238–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich Suanne and Weaver Kenneth A.. 1998. “Differences in Depressive Symptoms between Traditional Workers and Shift Workers.” Psychological Reports 83:571–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandner Michael A., Hale Lauren, Moore Melisa, and Patel Nirav P.. 2010. “Mortality Associated with Short Sleep Duration: The Evidence, the Possible Mechanisms and the Future.” Sleep Medicine Reviews 14:191–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale Lauren. 2005. “Who Has Time to Sleep?” Journal of Public Health 27:205–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale Lauren, Troxel Wendy, and Buysse Daniel J.. 2020. “Sleep Health: An Opportunity for Public Health to Address Health Equity.” Annual Review of Public Health 41:81–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrix Joshua. 2016. “Shift Work in the United States.” Pp. 1–4 in The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Family Studies, edited by Shehan Constance L.. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Herichova I 2013. “Changes of Physiological Functions Induced by Shift Work.” Endocrine Regulations 47: 159–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holst Meghan M., Wirth Michael D., Allison Penelope, Burch James B., Andrew Michael E., Fekedulegn Desta, Hussey James, Charles Luenda E., and Violanti John M.. 2021. “An Analysis of Shift Work and Self-reported Depressive Symptoms in a Police Cohort from Buffalo, New York.” Chronobiology International 38:830–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain JL, Reinish LW, Kayumov L, Bhuiya P, and Shapiro CM. 2003. “Underlying Sleep Pathology May Cause Chronic High Fatigue in Shift Workers.” Journal of Sleep Research 12:223–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson Chandra L., Redline Susan, and Emmons Karen M.. 2015. “Sleep as a Potential Fundamental Contributor to Disparities in Cardiovascular Health.” Annual Review of Public Health 36:417–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kecklund Göran and Axelsson John. 2016. “Health Consequences of Shift Work and Insufficient Sleep.” BMJ 356:i6599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krystal Andrew D., and Edinger Jack D.. 2008. “Measuring Sleep Quality.” Sleep Medicine 9: S10–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni Kshma, Schow Marie, and Shubrook Jay H.. 2020. “Shift Workers at Risk for Metabolic Syndrome.” The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association 120:107–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachman Margie E. 2015. “Mind the Gap in the Middle: A Call to Study Midlife.” Research in Human Development 12:3–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Hea Young, Kim Mi Sun, Kim OkSoo, Lee Il-Hyun, and Kim Han-Kyoul. 2016. “Association between Shift Work and Severity of Depressive Symptoms among Female Nurses: The Korea Nurses’ Health Study.” Journal of Nursing Management 24:192–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leggett Amanda N., Sonnega Amanda J., and Lohman Matthew C.. 2018. “The Association of Insomnia and Depressive Symptoms with All-cause Mortality among Middle-aged and Old Adults.” International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 33:1265–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine Stephen Z. 2013. “Evaluating the Seven-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale Short-form: A Longitudinal US Community Study.” Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 48: 1519–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Yujie, Wu Yili, Zhai Long, Wang Tong, Sun Yongye, and Zhang Dongfeng. 2017. “Longitudinal Association of Sleep Duration with Depressive Symptoms among Middle-aged and Older Chinese.” Scientific Reports 7:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim Yin Cheng, Hoe Victor C. W., Darus Azlan, and Bhoo-Pathy Nirmala. 2020. “Association between Night-shift Work, Sleep Quality, and Health-related Quality of Life: A Cross-sectional Study among Manufacturing Workers in a Middle-income Setting.” BMJ Open 10:e034455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon David P., Krull Jennifer L., and Lockwood Chondra M.. 2000. “Equivalence of the Mediation, Confounding and Suppression Effect.” Prevention Science 1:173–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon David P., Lockwood Chondra M., Hoffman Jeanne M., West Stephen G., and Sheets Virgil. 2002. “A Comparison of Methods to Test Mediation and Other Intervening Variable Effects.” Psychological Methods 7:83–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mai Quan D., Jacobs Anna W., and Schieman Scott. 2019. “Precarious Sleep? Nonstandard Work, Gender, and Sleep Disturbance in 31 European Countries.” Social Science and Medicine 237:112424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirowsky John and Ross Catherine E.. 1992. “Age and Depression.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 33:187–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mize Trention. n.d. “sgmediation2: Sobel-Goodman Tests of Mediation in Stata.” Retrieved February 3, 2023 (https://www.trentonmize.com/software/sgmediation2).

- Morgenthaler Timothy, Alessi Cathy, Friedman Leah, Owens Judith, Kapur Vishesh, Boehlecke Brian, Brown Terry, Chesson Andrew, Coleman Jack, Lee-Chiong Teo-filo, Pancer Jeffrey, and Swick Todd J.. 2007. “Practice Parameters for the Use of Actigraphy in the Assessment of Sleep and Sleep Disorders: An Update for 2007.” Sleep 30:519–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulton Calum D., Pickup John C., and Ismail Khalida. 2015. “The Link between Depression and Diabetes: The Search for Shared Mechanisms.” The Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology 3:461–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakata Akinori. 2011. “Work Hours, Sleep Sufficiency, and Prevalence of Depression among Full-time Employees: A Community-based Cross-sectional Study [CME].” The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 72:605–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu Shu-Fen, Chung Min-Huey, Chen Chiung-Hua, Hegney Desley, O’Brien Anthony, and Chou Kuei-Ru. 2011. “The Effect of Shift Rotation on Employee Cortisol Profile, Sleep Quality, Fatigue, and Attention Level: A Systematic Review.” Journal of Nursing Research 19:68–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordin Maria, Knutsson Anders, and Sundbom Elisabet. 2008. “Is Disturbed Sleep a Mediator in the Association between Social Support and Myocardial Infarction?” Journal of Health Psychology 13:55–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojile Joseph. 2017. “National Sleep Foundation Sets the Standard for Sleep as a Vital Sign of Health.” Sleep Health: Journal of the National Sleep Foundation 3: 226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandi-Perumal Seithikurippu R., Monti Jaime M., Burman Deepa, Karthikeyan Ramanujam, BaHammam Ahmed S., Spence David Warren, Brown Gregory M., and Narashimhan Meera. 2020. “Clarifying the Role of Sleep in Depression: A Narrative Review.” Psychiatry Research 291:113239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandi-Perumal Seithikurippu R., Moscovitch Adam, Srinivasan Venkatramanujam, Spence David Warren, Cardinali Daniel P., and Brown Gregory M.. 2009. “Bidirectional Communication between Sleep and Circadian Rhythms and Its Implications for Depression: Lessons from Agomelatine.” Progress in Neurobiology 88:264–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Hwanjin, Suh Byungsung, and Lee Soo-Jin. 2019. “Shift Work and Depressive Symptoms: The Mediating Effect of Vitamin D and Sleep Quality.” Chronobiology International 36:689–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin Leonard I., and Bierman Alex. 2013. “Current Issues and Future Directions in Research into the Stress Process.” Pp. 325–40 in Handbook of the Sociology of Mental Health, edited by Aneshensel CS, Phelan JC, and Bierman A. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin Leonard I., Menaghan Elizabeth G., Lieberman Morton A., and Mullan Joseph T.. 1981. “The Stress Process.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 22: 337–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrucci Robert, MacDermid Shelley, King Ericka, Tang Chiung-Ya, Brimeyer Ted, Ramadoss Kamala, Kiser Sally Jane, and Swanberg Jennifer. 2007. “The Significance of Shift Work: Current Status and Future Directions.” Journal of Family and Economic Issues 28:600–17. [Google Scholar]

- Perry-Jenkins Maureen, Goldberg Abbie E., Pierce Courtney P., and Sayer Aline G.. 2007. “Shift Work, Role Overload, and the Transition to Parenthood.” Journal of Marriage and Family 6:123–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenström Tom, Jokela Markus, Puttonen Sampsa, Hintsanen Mirka, Pulkki-Råback Laura, Viikari Jorma S., Raitakari Olli T., and Keltikangas-Järvinen Liisa. 2012. “Pairwise Measures of Causal Direction in the Epidemiology of Sleep Problems and Depression.” PLoS ONE 7:e50841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallinen Mikael, Härmä Mikko, Mutanen Pertti, Ranta Riikka, Virkkala Jussi, and Müller Kiti. 2003. “Sleep-wake Rhythm in an Irregular Shift System.” Journal of Sleep Research 12:103–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinkewicz Marilyn, Rostant Ola, Zivin Kara, McCammon Ryan, and Clarke Philippa. 2022. “A Life Course View on Depression: Social Determinants of Depressive Symptom Trajectories Over 25 Years of Americans’ Changing Lives.” SSM-Population Health 18:101125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleep Foundation. 2021. “Sleep Latency.” Retrieved February 3, 2023 (https://www.sleepfoundation.org/how-sleep-works/sleep-latency).

- Strazdins Lyndall, Clements Mark S., Korda Rosemary J., Broom Dorothy H., and D’Souza Rennie M.. 2006. “Unsociable Work? Nonstandard Work Schedules, Family Relationships, and Children’s Well-being.” Journal of Marriage and Family 68: 394–410. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi Masaya. 2014. “Assisting Shift Workers Through Sleep and Circadian Research.” Sleep and Biological Rhythms 12:85–95. [Google Scholar]

- Theorell Töres, Hammarström Anne, Aronsson Gunnar, Bendz Lil Träskman, Grape Tom, Hogstedt Christer, Marteinsdottir Ina, Skoog Ingmar, and Hall Charlotte. 2015. “A Systematic Review Including Meta-analysis of Work Environment and Depressive Symptoms.” BMC Public Health 15:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuttle Robert and Garr Michael. 2012. “Shift Work and Work to Family Fit: Does Schedule Control Matter?” Journal of Family and Economic Issues 33:261–71. [Google Scholar]

- Uchino Bert N., Landvetter Joshua, Cronan Sierra, Scott Emily, Papadakis Michael, Smith Timothy W., Bosch Jos A., and Joel Samantha. 2019. “Self-rated Health and Inflammation: A Test of Depression and Sleep Quality as Mediators.” Psychosomatic Medicine 81:328–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2019. “Job Flexibilities and Work Schedules.” Retrieved February 3, 2023 (https://www.bls.gov/news.release/flex2.nr0.htm).

- Vallières Annie, Azaiez Aïda, Moreau Vincent, LeBlanc Mélanie, and Morin Charles M.. 2014. “Insomnia in Shift Work.” Sleep Medicine 15:1440–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel Matthias, Braungardt Tanja, Meyer Wolfgang, and Schneider Wolfgang. 2012. “The Effects of Shift Work on Physical and Mental Health.” Journal of Neural Transmission 119:1121–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton Blair, Young Marisa, Montazer Shirin, and Stuart-Lahman Katie. 2013. “Social Stress in the Twenty-first Century.” Pp. 299–323 in Handbook of the Sociology of Mental Health, edited by Stets JE and Turner JH. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Williams Cara. 2008. Work-life Balance of Shift Workers. Vol. 9. Ottawa, ON, Canada: Statistics Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Wöhrmann Anne, Müller Grit, and Ewert Kathrin. 2020. “Shift Work and Work-family Conflict: A Systematic Review.” Sozialpolitik .ch 3:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Yong Lee C., Li Jia, and Calvert Geoffrey M.. 2017. “Sleep-related Problems in the US Working Population: Prevalence and Association with Shiftwork Status.” Occupational and Environmental Medicine 74: 93–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]