Abstract

Cytochrome P450 2D6 (CYP2D6) is involved in the metabolism of >20% of marketed drugs. CYP2D6 expression and activity exhibit high interindividual variability and is induced during pregnancy. The farnesoid X receptor (FXR) is a transcriptional regulator of CYP2D6 that is activated by bile acids. In pregnancy, elevated plasma bile acid concentrations are associated with maternal and fetal risks. However, modest changes in bile acid concentrations may occur during healthy pregnancy, thereby altering FXR signaling. A previous study demonstrated that hepatic tissue concentrations of bile acids positively correlated with the hepatic mRNA expression of CYP2D6. This study sought to characterize the plasma bile acid metabolome in healthy women (n = 47) during midpregnancy (25–28 weeks gestation) and ≥3 months postpartum and to determine if plasma bile acids correlate with CYP2D6 activity. It is hypothesized that during pregnancy, plasma bile acids would favor less hydrophobic bile acids (cholic acid vs. chenodeoxycholic acid) and that plasma concentrations of cholic acid and its conjugates would positively correlate with the urinary ratio of dextrorphan/dextromethorphan. At 25–28 weeks gestation, taurine-conjugated bile acids comprised 23% of the quantified serum bile acids compared with 7% ≥3 months postpartum. Taurocholic acid positively associated with the urinary ratio of dextrorphan/dextromethorphan, a biomarker of CYP2D6 activity. Collectively, these results confirm that the bile acid plasma metabolome differs between pregnancy and postpartum and provide evidence that taurocholic acid may impact CYP2D6 activity during pregnancy.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT

Bile acid homeostasis is altered in pregnancy, and plasma concentrations of taurocholic acid positively correlate with CYP2D6 activity. Differences between plasma and/or tissue concentrations of farnesoid X receptor ligands such as bile acids may contribute to the high interindividual variability in CYP2D6 expression and activity.

Introduction

Cytochrome P450 2D6 (CYP2D6) is a drug-metabolizing enzyme responsible for the metabolism of >20% of marketed drugs in the United States (Pan et al., 2017). CYP2D6 expression and activity exhibit high interindividual variability that is attributed to genetic determinants such as allelic copy number and polymorphisms, regulation by transcription factors, and posttranscriptional regulatory mechanisms (Pan et al., 2017; Gaedigk et al., 2018). The mechanisms that determine the basal expression level of CYP2D6 and contribute to observed interindividual variability of CYP2D6-mediated drug metabolism are not completely understood (Gaedigk et al., 2018). Although considered to be noninducible by xenobiotics, increased hepatic CYP2D6 expression and activity are observed during pregnancy (Pan et al., 2017) and contribute to increased clearance of drug substrates such as metoprolol, clonidine, dextromethorphan, and paroxetine during pregnancy (Isoherranen and Thummel, 2013).

Prior work has implicated a central role of the farnesoid X receptor (FXR) and downstream transcription factors, including the orphan nuclear receptor small heterodimer partner (SHP), hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 alpha (HNF4α), and liver receptor homolog-1 (LRH-1) in the regulation of CYP2D6 expression (Koh et al., 2014; Pan et al., 2017; Ning et al., 2019). Hepatic FXR activation by bile acids (Choudhuri and Klaassen, 2022) and retinoids (Cai et al., 2010; Koh et al., 2014) induces expression of SHP, which represses the expression of CYP7A1, CYP8B1, and consequently de novo biosynthesis of FXR’s cognate ligands, bile acids. SHP activation also inhibits the activation of HNF4α and LRH-1 and results in downregulation of CYP2D6 in CYP2D6-humanized mice (Koh et al., 2014) and reproduced in human hepatocytes using a synthetic potent FXR agonist, GW4064 (Pan et al., 2015). In contrast, SHP repression such as during pregnancy increases HNF4α recruitment to CYP2D6 gene promoter resulting in gene induction and increased CYP2D6 metabolic activity in CYP2D6-humanized mice (Koh et al., 2014).

The mechanisms driving CYP2D6 induction during pregnancy remain unclear. Past evidence from in vitro and animal studies supported a mechanism by which declining retinoid concentrations during pregnancy reduced activation of SHP, relieving repression of CYP2D6 expression compared with postpartum (Amaeze et al., 2023). However, recently all-trans-retinoic acid (atRA) plasma concentrations were reported to be higher in pregnancy than postpartum (Czuba et al., 2022; Amaeze et al., 2023; Jeong et al., 2023) and have a positive correlation with the urinary ratio of dextromethorphan/dextrorphan (DM/DX), a marker of CYP2D6 activity (Amaeze et al., 2023). In contrast, in human liver, hepatic atRA concentrations did not associate with CYP2D6 mRNA (Ning et al., 2019). It is unclear if changes in human plasma and/or tissue concentrations of FXR ligands during pregnancy promote reciprocal changes in the endogenous regulation of hepatic SHP expression and its downstream target genes such as CYP2D6. However, modest changes in bile acid concentrations and/or a shift in bile acid metabolism to favor cholic acid (CYP8B1) over chenodeoxycholic acid (CYP7A1) may occur during healthy pregnancy, thereby altering FXR signaling pathways in the liver. Additionally, intestinal bile acid signaling is impaired in human pregnancy, as evident by reduced serum levels of the FXR-regulated hormone fibroblast growth factor 19 (FGF19) in the third trimester (Ovadia et al., 2019). FGF19 is a critical postprandial regulator of de novo hepatic bile acid synthesis, and reduced levels in pregnant women are associated with increased serum concentrations of the bile acid intermediate 7α-hydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one (C4) (Ovadia et al., 2019).

The goal of this study was to characterize the plasma bile acid metabolome in healthy women (n = 47) during pregnancy (25–28 weeks gestation) and ≥3 months postpartum and to determine if plasma bile acids correlate with CYP2D6 activity during pregnancy and postpartum. Metabolomics was validated using quantitative liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analysis of cholic acid (CA), chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA), deoxycholic acid (DCA), and the corresponding taurine (T) and glycine (G) conjugates. As the cohort investigated did not have intrahepatic cholestasis (IHC), we hypothesized that during pregnancy plasma bile acids would favor less hydrophobic bile acids (CA vs. CDCA) and positively correlate with CYP2D6 activity, similar to that observed in healthy human livers (Ning et al., 2019).

Methods

Materials

Optima LC-MS grade acetonitrile, water, and formic acid were from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). Human serum (DC Mass Spect Gold MSG 4000) was from Golden West Biologics (Temecula, CA). Cholic acid (CA), chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA), deoxycholic acid (DCA), taurocholic acid (TCA), taurochenodeoxycholic acid (TCDCA), taurodeoxycholic acid (TDCA), glycocholic acid (GCA), glycochenodeoxycholic acid (GCDCA), and glycodeoxycholic acid (GDCA) were from Sigma-Aldrich. The following internal standards were purchased from Steraloids, Inc. (Newport, RI): CA-d4, CDCA-d4, DCA-d4, GCDCA-d4, and GCA-d4. TCA-d4, TDCA-d4, TCDCA-d4, and GDCA-d4 were purchased from Cayman Chemicals (Ann Arbor, MI).

Study Participants

Healthy pregnant women (singleton pregnancies) aged 18–50 years old were enrolled in this study. All enrolled participants were genotyped, and only women with CYP2D6 activity scores of 1, 1.5, or 2 participated in the study. All subjects provided written informed consent. Exclusion criteria included a history of obesity (BMI >30 kg/m2 based on prepregnancy weight), diabetes, kidney disease, liver disease. treatment of mental illness, vitamin A supplementation other than prenatal vitamins, or any current illness involving a fever or cough. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Washington (STUDY00001620, approved March 28, 2017) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki principles. This study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03117600).

As part of a larger prospective study evaluating regulators of CYP2D6 activity (Amaeze et al., 2023), each woman completed three study days [25–28 weeks gestation (study day 1), 28–32 weeks gestation (study day 2) and ≥3 months postpartum (study day 3)]. Greater than 91% of participants were taking a prenatal vitamin or folic acid supplement during their 25–28 weeks gestation study day. Prenatal vitamins were discontinued between study day 1 and study day 2. During this 3- to 4-week period between study day 1 and study day 2, each woman took folic acid (1 mg) orally daily. Subjects were randomized using random numbers (1:1) to receive either vitamin A 10,000 IU orally daily or no vitamin A during the period between study day 1 and study day 2. After study day 2, prenatal vitamins were restarted as part of routine clinical care.

Collection of Postprandial Plasma Samples

Blood samples were obtained from participants approximately 60 minutes after initiation of breakfast into foil-wrapped K2 EDTA vacutainer tubes, immediately placed on wet ice, and centrifuged within 10 minutes of collection at 3000 g for 10 minutes at 4°C, and then plasma was separated and immediately stored at −80°C until bioanalysis. Paired samples from study days 1 and 3 were compared to assess the impact of pregnancy on CYP2D6 activity and plasma bile acids. Samples from study day 2 were compared to assess the impact of vitamin A supplementation on plasma bile acids. Samples from all three study days were used to determine the relationship between bile acids and CYP2D6 activity.

Untargeted Metabolomics and Pathway Analysis

Metabolomics analysis was carried out by Metabolon Inc., adapted from previously published methods (Collet et al., 2017) and described in detail previously (Enthoven et al., 2023). Bile acid metabolites were identified using automated functions according to a reference library containing the retention time, mass-to-charge ratio, preferred adducts, in-source fragments, and associated spectra for reference standards and confirmed by visual inspection. Peak areas for each bile acid were batch normalized by dividing the raw peak area values by the median value for that metabolite. Missing values were replaced with the batch-normalized minimum value. MetaboAnalyst 5.0 (https://www.metaboanalyst.ca) was used to perform joint pathway analysis (Xia and Wishart, 2011; Enthoven et al., 2023).

Targeted Metabolomics and Quantification of Nine Bile Acids in Human Plasma

Bile acids were quantified from human plasma using methods modified from a previously published (Ning et al., 2019) ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS) method. A spiked standard curve was prepared in duplicate, and four independent quality control (QC) samples were prepared in triplicate in charcoal-stripped human serum for the following analytes: CA (9.77–1250 nM; QCs: 25nM, 50 nM, 250nM, 1000 nM); CDCA (19.53–1250 nM; QCs: 50 nM, 250 nM, 415 nM, 1000 nM); DCA (9.77–2500 nM; QCs: 25 nM, 50 nM, 250 nM, 1000 nM); GCDCA (39.06–2500 nM; QCs: 50 nM, 250 nM, 415 nM, 1000 nM); GCA (39.06–2500 nM; QCs: 25 nM, 50 nM, 250 nM, 1000 nM); GDCA (19.53–2500 nM; QCs: 50 nM, 250 nM, 415 nM, 1000 nM); TCA (9.77–2500 nM; QCs: 25 nM, 50 nM, 250 nM, 1000 nM); TDCA (9.77–1250 nM; QCs: 25 nM, 50 nM, 250 nM, 1000 nM); and TCDCA (9.77–1250 nM; QCs: 25 nM, 50 nM, 250 nM, 1000 nM). Additionally, nonspiked between day QC samples were prepared using plasma purchased from Bloodworks Northwest (Seattle, WA). Samples outside of the standard curve range were prepared at a 1:10 dilution in blank charcoal-stripped serum along with a set of dilution QCs.

For analysis, 60 μl of human plasma samples, standard curve samples, and QC samples were protein precipitated with 120 μl of ice-cold mixture of methanol and acetonitrile (50:50) spiked with 75 nM of the following internal standards: CA-d4, CDCA-d4, DCA-d4, GCDCA-d4, GCA-d4, TCA-d4, TDCA-d4, TCDCA-d4, and GDCA-d4. Samples were gently mixed by pipetting, and plates were centrifuged at 3000 g for 40 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was transferred to a new 96-well plate followed by a second centrifugation step at 3000 g for an additional 30 minutes at 4°C. One hundred microliters of final cleared supernatant was transferred to a 96-well plate and diluted with 50 μl of LC-MS–grade water for UHPLC-MS/MS analysis. All sample preparation was performed on ice.

Plasma bile acids were separated using an Agilent 1290 Infinity I UHPLC (Santa Clara, CA) coupled to a Waters (Milford, MA) ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 column (1.7 μm, 2.1 × 100 mm). A mobile phase consisting of (A) water + 0.1% formic acid and (B) acetonitrile + 0.1% formic acid was used at a flow rate of 0.45 ml/min at an initial condition of 25% mobile phase B, held for 2 minutes before a gradient elution to 40% B by 11 minutes and 95% by 14.5 minutes, and held at 95% for 2 minutes before returning to initial conditions.

Bile acids and internal standards detected on an AB SCIEX 5500 QTRAP Q-LIT mass spectrometer (Foster City, CA) operated in negative ion electrospray ionization (ESI) mode. The following transitions were monitored: CA (407.3 > 407.3), CA-d4 (411.3 > 411.3), CDCA (391.3 > 391.3), CDCA-d4 (395.3 > 395.3), DCA (391.2 > 345.2), DCA-d4 (395.3 > 349.3), GCDCA (448.2 > 73.9), GCDCA-d4 (452.2 > 74.2), GCA (454.4 > 74.1), GCA-d4 (468.4 > 73.9), GDCA (448.2 > 73.9), GDCA-d4 (452.2 > 74.2), TCA (452.2 > 74.2), TCA-d4 (518.4 > 79.8), TDCA (502.2 > 80.0), TDCA-d4 (502.2 > 80.0), TCDCA (502.2 > 80.0), and TCDCA-d4 (502.2 > 80.0). Collision energy and delustering potential were optimized for each compound.

Analyte peaks were integrated using MultiQuant 3.1 (SCIEX), and peak area ratios were quantified against the standard curve (weighted 1/x). For run acceptance, at each QC concentration, at least two-thirds of QC samples were within 15% of the nominal concentration in accordance with bioanalytical guidelines (https://www.fda.gov/files/drugs/published/Bioanalytical-Method-Validation-Guidance-for-Industry.pdf).

Statistical Methods

Data are expressed as geometric mean and interquartile range (IQR: 25th percentile, 75th percentile), unless otherwise indicated. Statistical comparisons were performed using GraphPad Prism 9.1 (San Diego, CA). Log-transformed bile acid concentrations from study day 1 (SD1) were compared with the paired study day 3 (SD3) sample using a two-sided paired t test. Log-transformed bile acid concentrations from study day 2 (SD2) were compared using a two-sided unpaired t test. P values for the individual bile acid concentration comparisons were compared for significance at an adjusted alpha of <0.0056 to account for the nine individual bile acid endpoints measured. In addition to reporting individual concentrations of plasma bile acids, surrogate measurements were calculated using published recommendations (Hofmann and Marschall, 2018). Briefly, plasma concentrations of the total plasma bile acid concentration in each participant were approximated through the summation of each of the nine bile acids. The CA/CDCA ratio was calculated using “Total CA” concentration/“Total CDCA” concentration. Total bile acid concentrations and the CA/CDCA ratio were compared using t tests, and significance was measured at P < 0.05. Absolute P values are reported.

To investigate if bile acids are putative regulators of CYP2D6 expression, an exploratory linear mixed-effect regression analysis was performed using the corresponding bile acid plasma concentrations measured at each of the three paired study day windows and previously reported log transformed 4-hour urinary metabolic ratio of dextromethorphan/dextrorphan (Amaeze et al., 2023). All analysis procedures were previously described (Amaeze et al., 2023). All analyses were performed using the NLME package in R 4.1.2 (https://www.r-project.org) (https://cran.r-project.org/package=nlme). Bonferroni correction was applied to account for multiple comparisons, and absolute P value was reported.

Results

Human Subjects

Forty-seven women with singleton pregnancies completed the study with an average age of 31.9 ± 5.7 years and a prepregnancy BMI of 26.1 ± 3.3 kg/m2. Participants self-identified their race and ethnicity as indicated in Table 1. No participants had any significant alterations in liver or kidney function throughout the study (Supplemental Table 1). In addition, no participants were diagnosed with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy or pruritis. All other reported medical conditions are as reported in detail previously (Czuba et al., 2022; Amaeze et al., 2023).

TABLE 1.

Participants’ weight (mean ± S.D.) and self-reported demographics

| Pregnant Women (n = 47) | Mean ± S.D. |

|---|---|

| Age (y) | 31.9 ± 5.7 |

| Prepregnancy BMI | 26.1 ± 3.3 |

| Weight (kg) | 71.4 ± 10.4 |

| Race | n (%) |

| Caucasiana | 35 (74.5%) |

| Blacka | 4 (8.5%) |

| Asian | 5 (10.6%) |

| Pacific Islander | 1 (2.1%) |

| Caucasian and Asian | 2 (4.3%) |

aOne participant self-identified as Caucasian of Hispanic descent, and all four participants identifying as Black were of African descent.

There was a higher prevalence of antihistamines, antacids, antiemetics, and laxatives used during pregnancy compared with postpartum (Supplemental Table 1). Supplementation with vitamin D, iron, and various forms of omega-3 fatty acids were also reported by some participants during pregnancy and postpartum.

Untargeted Plasma Metabolomics and Bile Acid Pathway Analysis

Previously, exploratory untargeted metabolomic analysis using plasma samples from this cohort identified 708 metabolites significantly different between pregnancy and postpartum and described significant global changes to biochemical pathways, including arginine, valine, leucine, isoleucine, and xanthine metabolism (Enthoven et al., 2023). Table 2 contains the mean peak area of 34 primary bile acids [unconjugated and taurine (T)- and glycine (G)-conjugated CA and CDCA] and bile acid secondary metabolites [unconjugated and taurine (T)- and glycine (G)-conjugated DCA, UDCA, IUDCA, HCA, MCA, etc.]. At 25–28 weeks of pregnancy and ≥3 months postpartum, the frequency of a given bile acid being present in the plasma of participants ranged from 51%–100% and 49%–100%, respectively. Based on peak area, 28 of 34 metabolites were significantly different between 25 and 28 weeks of pregnancy and ≥3 months postpartum. There was a general trend for higher taurine-conjugated metabolite peak areas and lower glycine-conjugated metabolites during pregnancy compared with postpartum. A summary of the statistically significant changes identified in the untargeted metabolomics can be found in Fig. 1.

TABLE 2.

Batch-normalized peak areas of bile acids measured using untargeted metabolomic methods

Plasma samples from n = 47 women drawn in pregnancy (25–28 weeks) and postpartum (≥3 months) were used in the analysis. The Paired Pregnancy/Postpartum Ratio was calculated for each participant and presented as the geometric mean and interquartile range. Paired Pregnancy/Postpartum ratio P values are calculated from paired t tests, and pathway P values (q-values) are adjusted by pathway weighting and the false discovery rate (FDR). Absolute P values are reported.

| Bile Acid Metabolite | Pregnant | Postpartum | Paired Pregnancy/Postpartum Ratio | P value | q-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± S.D. | Mean ± S.D. | Geometric Mean (IRQ: 25th, 75th) | |||

| Cholate | 2.13 ± 2.84 | 1.72 ± 1.63 | 0.96 (0.53, 1.97) | 0.8 | 0.081 |

| Glycocholate | 1.53 ± 1.44 | 1.90 ± 2.54 | 0.91 (0.43, 1.69) | 0.6 | 0.0619 |

| Taurocholate | 3.35 ± 3.80 | 1.09 ± 1.26 | 3.72 (1.40, 7.49)* | 8.50E-07 | 2.22E-07 |

| Chenodeoxycholate | 0.75 ± 0.83 | 1.32 ± 2.50 | 0.77 (0.43, 1.06) | 0.08 | 0.0105 |

| Glycochenodeoxycholate | 0.88 ± 0.69 | 2.23 ± 2.16 | 0.41 (0.21, 0.80)* | 4.20E-07 | 1.14E-07 |

| Taurochenodeoxycholate | 2.07 ± 1.87 | 1.33 ± 1.54 | 1.77 (0.79, 3.87)* | 0.005 | 0.0008 |

| Tauro-beta-muricholate | 2.76 ± 4.09 | 0.42 ± 0.55 | 7.59 (3.80, 15.70)* | 2.30E-18 | 3.36E-18 |

| Glyco-beta-muricholate | 1.62 ± 1.21 | 0.96 ± 0.76 | 1.65 (0.96, 2.88)* | 0.0002 | 3.77E-05 |

| Glycochenodeoxycholate glucuronide | 2.42 ± 2.04 | 0.78 ± 0.73 | 3.08 (2.20, 4.62)* | 1.49E-14 | 1.11E-14 |

| Glycochenodeoxycholate 3-sulfate | 1.18 ± 1.84 | 1.29 ± 0.75 | 0.67 (0.33, 1.02)* | 0.003 | 0.0004 |

| Glycocholate glucuronide | 1.13 ± 0.97 | 0.61 ± 0.75 | 1.82 (0.97, 3.83)* | 0.0001 | 1.71E-05 |

| Deoxycholate | 0.85 ± 0.69 | 1.33 ± 0.79 | 0.59 (0.31, 1.01)* | 0.002 | 0.0003 |

| Deoxycholic acid 12-sulfate | 1.13 ± 0.81 | 1.51 ± 1.40 | 0.78 (0.42, 1.35) | 0.1 | 0.0135 |

| Deoxycholic acid glucuronide | 0.84 ± 0.71 | 1.44 ± 1.16 | 0.56 (0.37, 0.92)* | 4.30E-06 | 1.01E-06 |

| Glycodeoxycholate | 1.15 ± 1.10 | 1.76 ± 1.88 | 0.65 (0.33, 1.36)* | 0.02 | 0.0032 |

| Taurodeoxycholate | 1.95 ± 1.86 | 0.89 ± 0.84 | 2.18 (0.91, 4.73)* | 0.0003 | 5.15E-05 |

| Taurodeoxycholic acid 3-sulfate | 2.89 ± 3.35 | 0.51 ± 0.43 | 5.74 (3.03, 11.61)* | 2.10E-16 | 2.31E-16 |

| Lithocholate sulfate | 0.75 ± 0.68 | 1.72 ± 1.15 | 0.40 (0.22, 0.70)* | 3.30E-07 | 8.98E-08 |

| Glycolithocholate | 0.52 ± 0.52 | 1.63 ± 0.97 | 0.26 (0.11, 0.55)* | 1.00E-08 | 3.38E-09 |

| Glycolithocholate sulfate | 0.77 ± 0.42 | 1.59 ± 0.95 | 0.54 (0.32, 0.75)* | 0.0001 | 2.54E-05 |

| Taurolithocholate 3-sulfate | 1.49 ± 0.99 | 1.01 ± 0.89 | 1.83 (0.99, 2.99)* | 4.10E-05 | 8.86E-06 |

| Ursodeoxycholate | 0.68 ± 0.95 | 1.85 ± 4.36 | 0.43 (0.26, 0.99)* | 0.0001 | 1.96E-05 |

| Isoursodeoxycholate | 0.89 ± 1.34 | 3.73 ± 5.54 | 0.25 (0.12, 0.48)* | 9.00E-15 | 7.03E-15 |

| Glycoursodeoxycholate | 0.99 ± 1.70 | 3.18 ± 4.59 | 0.30 (0.15, 0.58)* | 6.00E-11 | 2.70E-11 |

| Glycoursodeoxycholic acid sulfate | 1.75 ± 2.83 | 1.24 ± 1.16 | 0.90 (0.47, 1.62) | 0.4 | 0.0485 |

| Tauroursodeoxycholate | 1.07 ± 1.62 | 1.21 ± 2.77 | 1.12 (0.66, 2.01) | 0.4 | 0.0429 |

| Hyocholate | 1.02 ± 0.99 | 1.25 ± 0.94 | 0.72 (0.35, 1.29)* | 0.03 | 0.0047 |

| Glycohyocholate | 1.10 ± 0.89 | 1.44 ± 1.13 | 0.78 (0.49, 1.04)* | 0.04 | 0.0052 |

| Glycocholenate sulfate | 0.82 ± 0.43 | 1.37 ± 0.59 | 0.57 (0.39, 0.81)* | 2.10E-09 | 7.62E-10 |

| Taurocholenate sulfate | 1.67 ± 0.98 | 0.82 ± 0.54 | 2.10 (1.34, 2.88)* | 6.70E-10 | 2.59E-10 |

| 3b-hydroxy-5-cholenoic acid | 0.66 ± 0.49 | 1.17 ± 0.63 | 0.53 (0.35, 0.80)* | 3.60E-09 | 1.25E-09 |

| Glycodeoxycholate 3-sulfate | 1.66 ± 1.60 | 1.02 ± 0.81 | 1.61 (0.84, 2.54)* | 0.0014 | 0.0002 |

| Taurochenodeoxycholic acid 3-sulfate | 2.41 ± 3.58 | 0.78 ± 0.65 | 2.55 (1.31, 4.40)* | 2.20E-07 | 6.04E-08 |

| Glycodeoxycholate glucuronide | 2.08 ± 2.02 | 0.59 ± 0.69 | 3.77 (2.00, 5.72)* | 2.30E-12 | 1.25E-12 |

*Pregnancy/postpartum significant changes.

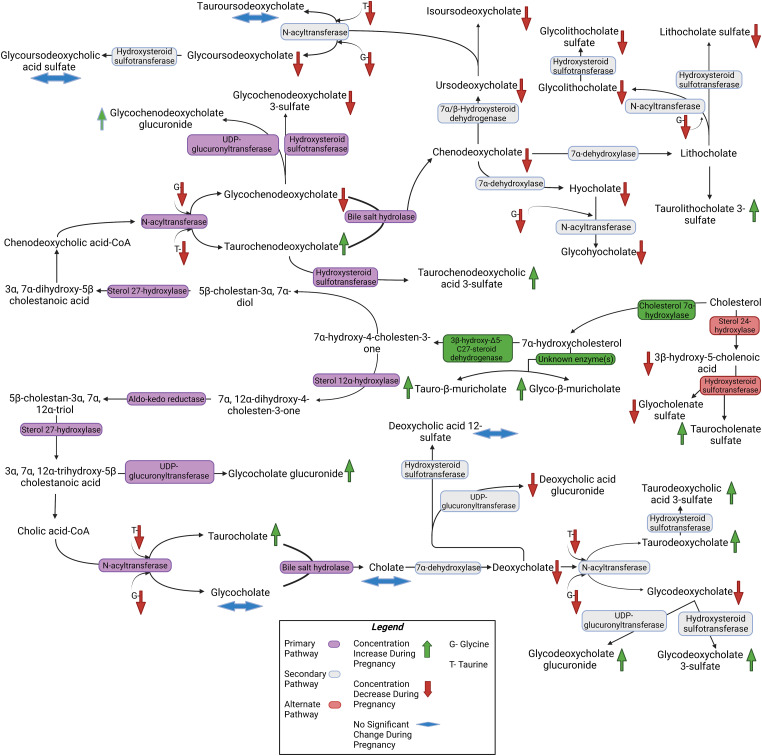

Fig. 1.

Pathway for synthesis of primary (marked in purple) and secondary (marked in gray) bile acids constructed using the mean peak areas measured in the untargeted metabolomics assays and constructed based on Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways for bile acid synthesis. An alternate pathway is also depicted (marked in red). Downward pointing arrows indicate lower metabolite peak areas in pregnancy (25–28 weeks of gestation) compared with ≥3 months postpartum (marked in red), whereas upward arrows indicate higher peak area during pregnancy compared with postpartum (marked in green). Double pointed horizontal arrows indicate no significant change (blue). Tauro-β-muricholic acid and glyco-β-muricholic acid were not included in the pathway as they are not recognized as major bile acid metabolites in humans.

Quantitative Targeted Bile Acid Metabolomics

To validate the untargeted metabolomic analysis, nine bile acids considered to be the most abundant in plasma (Hofmann and Marschall, 2018) were quantified in plasma samples from 25 to 28 weeks gestation and ≥3 months postpartum (Table 3). Concentrations of unconjugated bile acids, CA, and CDCA were low in plasma compared with the glycine- and taurine-conjugated bile acids. At 25–28 weeks gestation, geometric mean plasma concentrations of unconjugated CA were 36.6 nM (IQR: 18.9 nM, 84.5 nM) and did not differ (P = 0.54) from ≥3 months postpartum 42.0 nM (IQR: 22.9 nM, 85.1 nM). In contrast, unconjugated CDCA plasma concentrations were lower (P < 0.0001) at 25–28 weeks gestation (40.4 nM; IQR: 17.4 nM, 103.6 nM) compared with ≥3 months postpartum (126.9 nM; IQR: 51.9 nM, 317.7 nM). The unconjugated bile acid metabolite, DCA, was also lower (P = 0.0043) at 25–28 weeks of gestation (280.0 nM; IQR: 184.4 nM, 480.1 nM) compared with ≥3 months postpartum (492.0 nM; IQR: 440.1 nM, 825.9 nM).

TABLE 3.

Plasma concentrations of nine bile acids measured using targeted LC-MS/MS methods

Plasma samples from n = 47 women drawn in pregnancy (25–28 weeks) and postpartum (≥3 months) were used in the analysis. Log-transformed concentrations measured at 25–28 weeks of gestation and ≥3 months postpartum were compared using two-way paired t tests. Significance was measured against an adjusted alpha of P < 0.0056 to account for the nine separate comparisons. Absolute P values are reported. The sum of all nine bile acids was calculated for each participant and geometric mean and IQR were reported along with percentage of unconjugated bile acids (CA, CDCA, DCA), taurine conjugates (TCA, TCDCA, TDCA), and glycine conjugates (GCA, GCDCA, GDCA). For each bile acid, the pregnancy-to-postpartum ratio was calculated for each participant and the geometric mean ratio and IQR were reported.

| 25–28 Weeks Gestation | ≥3 Months Postpartum | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bile Acids | Geometric Mean | Pregnancy/Postpartum | P Valuea | |

| (nM) | (Interquartile Range: 25th, 75th) | Paired Ratio | Adjusted Alpha P < 0.0056 | |

| Cholic acid | 36.6 | 42.0 | 0.9 | 0.54 |

| (18.9, 84.5) | (22.9, 85.1) | (0.4, 0.8) | ||

| Chenodeoxycholic acid | 40.4 | 126.9 | 0.3 | <0.0001* |

| (17.4, 103.6) | (51.9, 317.7) | (0.1, 0.3) | ||

| Deoxycholic acid | 280.0 | 492.0 | 0.6 | 0.0043* |

| (184.4, 480.1) | (440.1, 825.9) | (0.3, 0.6) | ||

| Glycocholic acid | 386.7 | 423.1 | 0.9 | 0.61 |

| (193.5, 717.9) | (222.8, 792.0) | (0.4, 1.0) | ||

| Glycochenodeoxycholic acid | 501.1 | 1204.0 | 0.4 | <0.0001* |

| (325.6, 916.1) | (542.1, 2525.3) | (0.2, 0.5) | ||

| Glycodeoxycholic acid | 350.1 | 523.5 | 0.7 | 0.047 |

| (204.6, 761.7) | (336.2, 974.6) | (0.4, 0.7) | ||

| Taurocholic acid | 154.4 | 47.9 | 3.2 | <0.0001* |

| (70.3, 337.0) | (18.7, 106.5) | (1.2, 3.0) | ||

| Taurochenodeoxycholic acid | 213.3 | 122.7 | 1.7 | 0.0049* |

| (113.2, 514.8) | (71.0, 232.1) | (0.8, 1.6) | ||

| Taurodeoxycholic acid | 177.0 | 74.2 | 2.4 | <0.0001* |

| (87.6, 464.2) | (30.1, 171.8) | (1.2, 2.2) | ||

| Σ Bile acids | 2487.2 (1458.3, 4559.7) | 3684.9 (2038.3, 5690.4) | ||

| % Unconjugated bile acids | 15.9% (11.0%, 31.6%) | 22.5% (13.5%, 40.2%) | ||

| % Glycine-conjugated bile acids | 53.0% (46.9%, 61.3%) | 63.3% (53.3%, 74.7%) | ||

| % Taurine-conjugated bile acids | 23.3% (19.0%, 35.1%) | 7.2% (5.1%, 12.3%) | ||

aLog-transformed data compared using a two-way paired t test.

*Significant difference (determined using an adjusted alpha = 0.0056).

At 25–28 weeks gestation, the geometric mean plasma concentrations of the glycine-conjugated bile acids, GCDCA and GCA, were 501.1 nM (IQR: 325.6 nM, 916.1 nM) and 386.7 nM (IQR: 193.5 nM, 717.9 nM), respectively. In comparison, at ≥3 months postpartum, GCDCA was higher than during pregnancy (P < 0.0001), with a geometric mean concentration of 1204.0 nM (IQR: 542.1 nM, 2,525.3 nM). In contrast, plasma GCA concentrations were not statistically different (P = 0.61) between 25 and 28 weeks of gestation and ≥3 months postpartum (423.1 nM (IQR: 222.8 nM, 792.0 nM)). At 25–28 weeks gestation, the concentration of GDCA was 350.1 nM (IQR: 204.6 nM, 761.7 nM) compared with 523.5 nM (IQR: 336.2 nM, 974.6 nM) postpartum, which did not reach statistical significance at the adjusted alpha (P < 0.0056).

Bile acids are also conjugated with taurine. Plasma TCA concentrations were higher (P < 0.0001) at 25–28 weeks gestation (154.4 nM; IQR: 70.3 nM, 337.0 nM) than at ≥3 months postpartum (47.9 nM; IQR: 18.7 nM, 106.5 nM). Additionally, TCDCA was higher (P = 0.0049) at 25–28 weeks (213.3 nM; IQR:113.2 nM, 514.8 nM) than at ≥3 months postpartum (122.7 nM; IQR: 71.0 nM, 232.1 nM). Similarly, TDCA concentrations were higher (P < 0.0001) at 25–28 weeks (177.0 nM; IQR: 87.6 nM, 464.2 nM) than at ≥3 month postpartum (74.2 nM; IQR: 30.1 nM, 171.8 nM). Overall, the geometric mean of fold change in the TCA, TDCA, and TCDCA plasma concentrations at 25–28 weeks gestation versus ≥3 month postpartum was 3.2, 2.4, and 1.7, respectively.

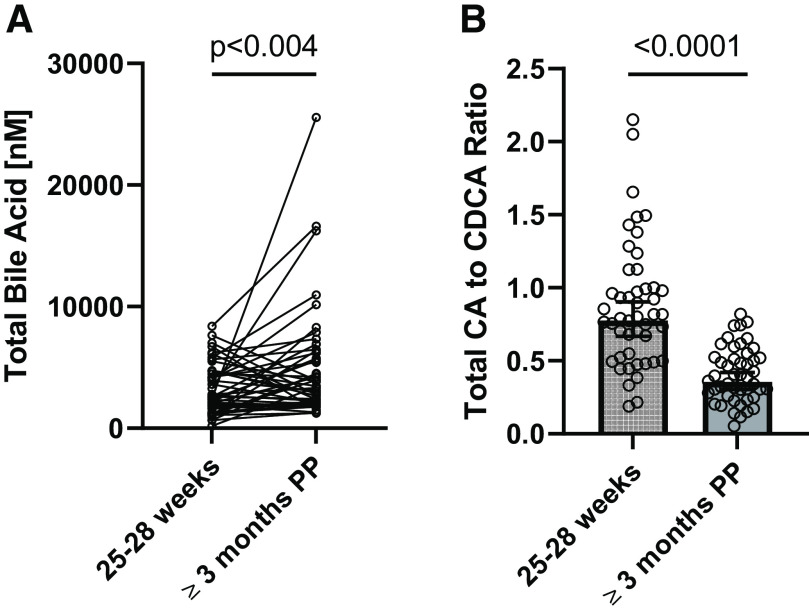

It is routine to sum individual bile acid metabolites measured in plasma to approximate the “total” plasma bile acid concentration for comparison with literature data (Hofmann and Marschall, 2018). The sum of the nine bile acids measured was 2487.2 nM (IQR: 1458.3 nM, 4559.7 nM) at 25–28 weeks of gestation and 3684.9 nM (IQR: 2038.3 nM, 5690.4 nM) at ≥3 months postpartum. Although the geometric mean total bile acid pool concentration appeared higher at ≥3 months postpartum (Table 3), this was driven by a few participants with high postprandial bile acid concentrations postpartum. The total postprandial bile acid plasma concentrations were different (P = 0.03) at 25–28 weeks gestation when compared with paired plasma samples taken ≥3 months postpartum (Fig. 2A). During primary bile acid synthesis, the expression and activity of CYP8B1 determines the ratio of CA to CDCA. Here, the geometric mean CA/CDCA ratio was 0.78 (IQR: 0.53, 1.0) at 25–28 weeks gestation and 0.36 (IQR: 0.26, 0.52) at ≥3 months postpartum (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Secondary comparisons of (A) total bile acids and (B) total CA-to-CDCA ratio, which are calculated from the nine bile acids measured using a targeted LC-MS/MS method and represented as the individual values or geometric mean ± 95% confidence interval (CI), respectively. Plasma samples from n = 47 women drawn in pregnancy (25–28 weeks) and postpartum (≥3 months) were used in the analysis. Log-transformed concentrations measured at 25–28 weeks of gestation and ≥3 months postpartum were compared using two-way paired t tests without correction for multiple comparisons. Absolute P values are reported.

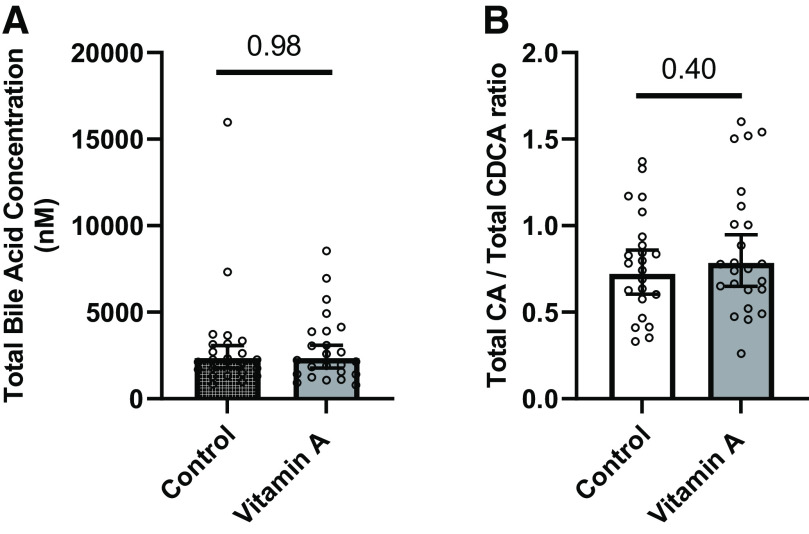

Impact of Vitamin A Supplementation on Plasma Bile Acid Metabolome

Vitamin A has been shown to induce the expression of SHP (Cai et al., 2010; Mamoon et al., 2014), a well known repressor of bile acid synthesis. To determine if vitamin A supplementation impacts postprandial bile acid concentrations, plasma bile acids were measured at 28–32 weeks of gestation and provided in Supplemental Table 2. No difference was observed (P = 0.98) in the total calculated concentration of bile acids between pregnant women who supplemented with low-dose vitamin A (2344.4 nM; IQR: 1415.6 nM, 3889.3 nM) and those without supplementation (2335.3 nM; IQR: 1587.0 nM, 3160.6 nM) (Fig. 3A). Likewise, there was no statistical difference observed in the ratio of CA to CDCA between pregnant women receiving vitamin A compared with those not receiving vitamin A (P = 0.40) (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of the (A) calculated total bile acid concentration and (B) calculated total CA-to-CDCA ratio plasma concentration between pregnant women at 28–32 weeks of gestation (study day 2) with vitamin A supplementation (n = 24) or without (n = 23). Calculations are based on the quantification of nine bile acids measured using a targeted LC-MS/MS method and represented as geometric mean ± 95% CI. Log-transformed concentrations measured were compared using two-way unpaired t tests without correction for multiple comparisons. Absolute P values are reported.

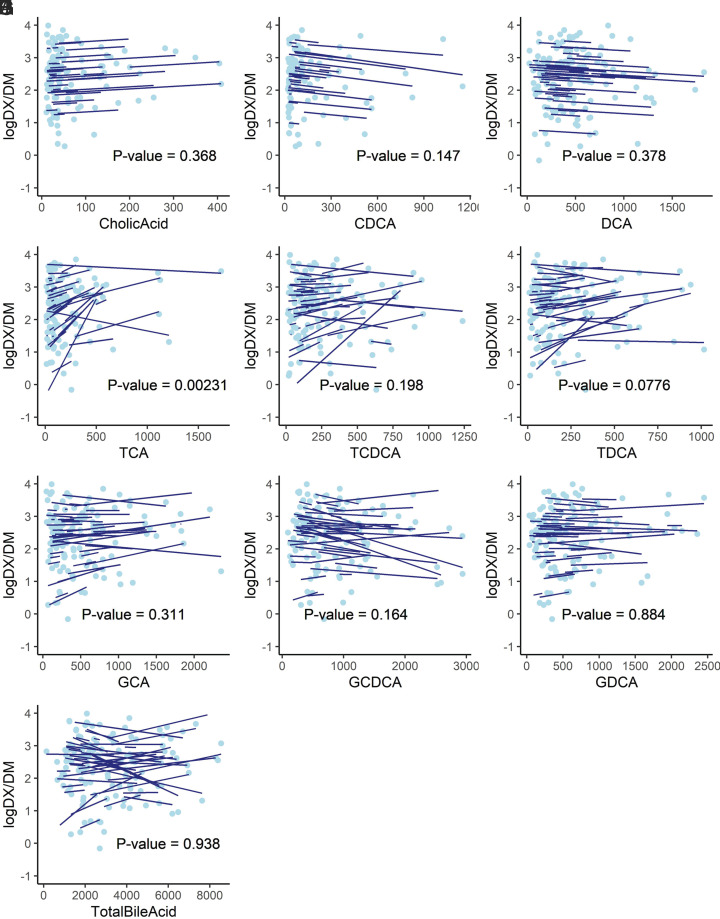

Bile Acids As Putative Regulators of SHP Target Gene CYP2D6

The relationship between the reported 4-hour urinary DX/DM ratio and the plasma concentration of different bile acids is shown in Fig. 4. Taurocholic acid concentrations were correlated with CYP2D6 activity (P = 0.0023) across the three study days even after Bonferroni correction for multiple hypothesis testing (nine bile acids and total bile acid, corrected α = 0.005). No other plasma bile acid concentration or calculated total bile acid concentration was observed to have a significant association with CYP2D6 activity.

Fig. 4.

Log-transformed urinary dextrorphan (DX)/dextromethorphan (DM) ratio versus plasma (A) cholic acid, (B) chenodeoxycholic acid, (C) deoxycholic acid, (D) taurocholic acid, (E) taurochenodeoxycholic acid, (F) taurodeoxycholic acid, (G) glycocholic acid, (H) glycochenodeoxycholic acid, (I) glycodeoxycholic acid, and (J) total bile acid concentrations (nM). Light-blue solid dots represent repeated measurements from n = 47 participants, whereas each dark-blue solid line represents the prediction from a linear mixed-effect model for each individual participant. The P value of the regression coefficient is displayed.

Discussion

This study reports differences in plasma concentrations of individual bile acids in pregnancy compared with postpartum and provides preliminary evidence of an association between plasma TCA concentrations and CYP2D6 regulation. Our results demonstrate that in pregnancy compared with postpartum there is decreased plasma concentrations of unconjugated bile acids and increased plasma concentrations of taurine conjugates. A positive association was observed between plasma TCA concentrations and the 4-hour urinary metabolic ratio of dextrorphan/dextromethorphan. To our knowledge, this is the first report to demonstrate that physiologic changes to the human plasma bile acid metabolome are positively associated with induction of CYP2D6 activity. However, these findings are supported by a previous report demonstrating that basal CYP2D6 mRNA expression is positively correlated with hepatic total bile acid concentrations, the percentage of hepatic total cholic acid, and expression levels of downstream FXR target genes SHP, HNF4A and CYP8B1 (Ning et al., 2019). A higher CA-to-CDCA ratio during pregnancy compared with postpartum was observed both here and previously (Gagnon et al., 2021) and may suggest an increase in CYP8B1 activity shifting the bile acid metabolic pathway to favor CA formation. The relative potencies of CA, CDCA, and DCA as well as their conjugates toward FXR activation are generally considered comparable in the presence of active transporters (Wang et al., 1999), so the clinical relevance of differential changes between bile acids is currently unclear.

Other transcriptional regulators can modify FXR signaling including retinoids (Cai et al., 2010; Mamoon et al., 2014). Retinoids such as all-trans-retinoic acid induced SHP expression in liver tissue via FXR/RXR (retinoid X receptor) signaling pathways (Cai et al., 2010). Retinoids can repress metabolism of bile acids and CYP2D6 mRNA expression and activity (Cai et al., 2010; Stevison et al., 2019). Here we demonstrate that vitamin A supplementation during pregnancy does not alter the total concentration of bile acids or any individual bile acids in circulation. Like plasma TCA concentrations, a mild positive association of CYP2D6 activity with atRA plasma concentrations was previously observed in this cohort (Amaeze et al., 2023). Collectively, these findings conflict with the established roles of bile acids and retinoids in the FXR-mediated activation of SHP (Chiang et al., 2000; Watanabe et al., 2004; Cai et al., 2010; Koh et al., 2014), as it would be expected that increased concentrations of either ligand class would promote SHP activity and, in turn, repress CYP2D6 expression and activity. Future work is needed to confirm and understand why TCA plasma concentrations, but not TCDCA, TDCA, glycine conjugates, or even total calculated bile acid concentration, are positively correlated with CYP2D6 activity in pregnancy. It may support observations of ligand-specific transcriptional signaling by FXR (Ramos Pittol et al., 2020) or implicate ligand-specific differences in the recruitment of coactivator/repressors. Thus, future mechanistic work is required to understand differences in the FXR-SHP signaling patterns of different bile acid metabolites.

A major strength of the study is the validation of the untargeted metabolomic pathway analysis using targeted, quantitative liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) methods. The data support prior studies that bile acid homeostasis is altered during human pregnancy (Glantz et al., 2004; Barth et al., 2005; Gagnon et al., 2021; He et al., 2022) and that a subset of normal pregnant women experience asymptomatic hypercholanemia, which is defined by total plasma or serum bile acids >6 μM (Barth et al., 2005) in the absence of intrahepatic cholestasis (IHC) (He et al., 2022). Total serum bile acids in healthy pregnant women have been shown to be moderately correlated and overlap between the fasting (4.4–14.1 μM) and postprandial (4.7–20.2 μM) state (Mor et al., 2021). The total bile acid plasma concentrations calculated for the participants in this study were within the postprandial range for normal pregnancies (Mor et al., 2021), and no participants were diagnosed with pruritus or IHC during the study. Bile acid conjugation to taurine or glycine results in bile acids that are less hydrophobic and carry less risk of liver toxicity as concentrations rise compared with unconjugated bile acids (Hofmann, 1984). Collectively, when comparing pregnancy and postpartum plasma concentrations, there was an increase in taurine-conjugated bile acids. The enzyme responsible for conjugation, bile acid–CoA:amino acid N-acyltransferase (BAAT), has similar enzyme activity toward glycine or taurine, so differences in conjugation are likely driven by amino acid availability (Styles et al., 2016). Glycine is needed for production of heme and glutathione and can be obtained dietarily or biosynthesized in humans. Recently, it has been established that there is an indispensable maternal need for dietary glycine in late gestation (30–40 weeks) (Rasmussen et al., 2021). It is possible that there is a conditional switch to bile acid taurine conjugation earlier in pregnancy to compensate for increased metabolic demand for glycine. Thus, measured differences in the plasma concentration of individual bile acids likely represent collective changes to the biosynthesis pathway, taurine or glycine hepatic availability, and potentially hepatic bile acid uptake in human pregnancy. A limitation of the current analysis is that some participants reported use of supplements (e.g., vitamin D, omega-3s/fish oils) that can indirectly alter bile acid homeostasis by altering bile acid metabolism and feedback mechanisms (Jacobs et al., 2016; Cieślak et al., 2018). The study was not designed to investigate these interactions or differences related to pregnancy complications. In addition, the bile acid precursor 7α-hydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one was not measured, limiting interpretation as to whether increases in the taurine conjugates were associated with increased bile acid synthesis (Sauter et al., 1996; Ovadia et al., 2019) or other metabolic and transport processes (Ovadia et al., 2019). Although prior work has shown that pregnancy is associated with reduced enterohepatic regulation of bile acid de novo synthesis (Ovadia et al., 2019), future work is needed to establish the role of alternative mechanisms promoting altered bile acid homeostasis in pregnancy. Collectively, this study supports that bile acid homeostasis is altered in human pregnancy. The results are vital to understanding transient changes to bile acid homeostasis in pregnancy and will provide preliminary insight into drivers of pregnancy-related changes in CYP2D6-mediated drug metabolism in humans.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- atRA

all-trans-retinoic acid

- CA

cholic acid

- CDCA

chenodeoxycholic acid

- DCA

deoxycholic acid

- DM

dextromethorphan

- DX

dextrorphan

- FXR

farnesoid X receptor

- GCA

glycocholic acid

- GCDCA

glycochenodeoxycholic acid

- and GDCA

glycodeoxycholic acid

- HNF4α

hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 alpha

- IHC

intrahepatic cholestasis

- IQR

interquartile range

- LC-MS

liquid chromatography mass spectrometry

- LC-MS/MS

liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry

- QC

quality control

- SHP

small heterodimer partner

- TCA

taurocholic acid

- TCDCA

taurochenodeoxycholic acid

- TDCA

taurodeoxycholic acid

- UHPLC

ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Isoherranen, Hebert.

Conducted experiments: Czuba, Malhotra, Enthoven, Fay, Moreni, Mao, Shi, Huang, Hebert.

Contributed new reagents or analytic tools: Totah, Isoherranen, Hebert.

Performed data analysis: Czuba, Malhotra, Enthoven, Shi, Huang, Totah, Isoherranen, Hebert.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Czuba, Malhotra, Enthoven, Fay, Moreni, Mao, Shi, Huang, Totah, Isoherranen, Hebert.

Footnotes

This research was supported in part by National Institutes of Health National Institute of General Medical Sciences [Grant R01GM124264], National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases [Training Grant T32DK007247-42], and the University of Washington School of Pharmacy’s Milo Gibaldi Endowed Chair Fund. The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funders.

No author has an actual or perceived conflict of interest with the contents of this article.

This article has supplemental material available at dmd.aspetjournals.org.

This article has supplemental material available at dmd.aspetjournals.org.

References

- Amaeze OUCzuba LCYadav ASFay EELaFrance JShum SMoreni SLMao JHuang WIsoherranen N, et al. (2023) Impact of pregnancy and vitamin A supplementation on CYP2D6 activity. J Clin Pharmacol 63:363–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth A, Rost M, Kindt A, Peiker G (2005) Serum bile acid profile in women during pregnancy and childbed. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 113:372–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai SY, He H, Nguyen T, Mennone A, Boyer JL (2010) Retinoic acid represses CYP7A1 expression in human hepatocytes and HepG2 cells by FXR/RXR-dependent and independent mechanisms. J Lipid Res 51:2265–2274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang JYL, Kimmel R, Weinberger C, Stroup D (2000) Farnesoid X receptor responds to bile acids and represses cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase gene (CYP7A1) transcription. J Biol Chem 275:10918–10924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhuri S, Klaassen CD (2022) Molecular regulation of bile acid homeostasis. Drug Metab Dispos 50:425–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cieślak A, Trottier J, Verreault M, Milkiewicz P, Vohl MC, Barbier O (2018) N-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids stimulate bile acid detoxification in human cell models. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018:6031074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collet T-H, Sonoyama T, Henning E, Keogh JM, Ingram B, Kelway S, Guo L, Farooqi IS (2017) A metabolomic signature of acute caloric restriction. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 102:4486–4495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czuba LC, Fay EE, LaFrance J, Smith CK, Shum S, Moreni SL, Mao J, Isoherranen N, Hebert MF (2022) Plasma retinoid concentrations are altered in pregnant women. Nutrients 14:1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enthoven LFShi YFay EEMoreni SMao JHoneyman EMSmith CKWhittington DBrockerhoff SEIsoherranen N, et al. (2023) The effects of pregnancy on amino acid levels and nitrogen disposition. Metabolites 13:242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaedigk A, Dinh JC, Jeong H, Prasad B, Leeder JS (2018) Ten years’ experience with the CYP2D6 activity score: a perspective on future investigations to improve clinical predictions for precision therapeutics. J Pers Med 8:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon M, Trottier J, Weisnagel SJ, Gagnon C, Carreau AM, Barbier O, Morisset AS (2021) Bile acids during pregnancy: trimester variations and associations with glucose homeostasis. Health Sci Rep 4:e243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glantz A, Marschall HU, Mattsson LÅ (2004) Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: Relationships between bile acid levels and fetal complication rates. Hepatology 40:467–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Zhang X, Shao Y, Xu B, Cui Y, Chen X, Chen H, Luo C, Ding M (2022) Recognition of asymptomatic hypercholanemia of pregnancy: different clinical features, fetal outcomes and bile acids metabolism from intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 1868:166269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann AF (1984) Chemistry and enterohepatic circulation of bile acids. Hepatology 4(5, Suppl)4S–14S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann AF, Marschall H-U (2018) Plasma bile acid concentrations in humans: suggestions for presentation in tabular form. Hepatology 68:787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isoherranen N, Thummel KE (2013) Drug metabolism and transport during pregnancy: how does drug disposition change during pregnancy and what are the mechanisms that cause such changes? Drug Metab Dispos 41:256–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs ET, Haussler MR, Alberts DS, Kohler LN, Lance P, Martínez ME, Roe DJ, Jurutka PW (2016) Association between circulating vitamin D metabolites and fecal bile acid concentrations. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 9:589–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong H, Armstrong AT, Isoherranen N, Czuba L, Yang A, Zumpf K, Ciolino J, Torres E, Stika CS, Wisner KL (2023) Temporal changes in the systemic concentrations of retinoids in pregnant and postpartum women. PLoS One 18:e0280424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh KH, Pan X, Shen H-W, Arnold SLM, Yu A-M, Gonzalez FJ, Isoherranen N, Jeong H (2014) Altered expression of small heterodimer partner governs cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2D6 induction during pregnancy in CYP2D6-humanized mice. J Biol Chem 289:3105–3113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamoon A, Subauste A, Subauste MC, Subauste J (2014) Retinoic acid regulates several genes in bile acid and lipid metabolism via upregulation of small heterodimer partner in hepatocytes. Gene 550:165–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mor H, Seravalli V, Lippi C, Tofani L, Galli A, Petraglia F, Di Tommaso M (2021) Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: time to redefine the normal reference range of total serum bile acids. SSRN DOI: 10.2139/ssrn.3980533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ning M, Duarte JD, Stevison F, Isoherranen N, Rubin LH, Jeong H (2019) Determinants of cytochrome P450 2D6 mRNA levels in healthy human liver tissue. Clin Transl Sci 12:416–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ovadia CPerdones-Montero ASpagou KSmith ASarafian MHGomez-Romero MBellafante EClarke LCDSadiq FNikolova V, et al. (2019) Enhanced microbial bile acid deconjugation and impaired ileal uptake in pregnancy repress intestinal regulation of bile acid synthesis. Hepatology 70:276–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan X, Lee Y-K, Jeong H (2015) Farnesoid X receptor agonist represses cytochrome P450 2D6 expression by upregulating small heterodimer partner. Drug Metab Dispos 43:1002–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan X, Ning M, Jeong H (2017) Transcriptional regulation of CYP2D6 expression. Drug Metab Dispos 45:42–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos Pittol JM, Milona A, Morris I, Willemsen ECL, van der Veen SW, Kalkhoven E, van Mil SWC (2020) FXR isoforms control different metabolic functions in liver cells via binding to specific DNA motifs. Gastroenterology 159:1853–1865.e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen BF, Ennis MA, Dyer RA, Lim K, Elango R (2021) Glycine, a dispensable amino acid, is conditionally indispensable in late stages of human pregnancy. J Nutr 151:361–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauter G, Berr F, Beuers U, Fischer S, Paumgartner G (1996) Serum concentrations of 7alpha-hydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one reflect bile acid synthesis in humans. Hepatology 24:123–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevison F, Kosaka M, Kenny JR, Wong S, Hogarth C, Amory JK, Isoherranen N (2019) Does in vitro cytochrome P450 downregulation translate to in vivo drug-drug interactions? Preclinical and clinical studies with 13-cis-retinoic acid. Clin Transl Sci 12:350–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Styles NA, Shonsey EM, Falany JL, Guidry AL, Barnes S, Falany CN (2016) Carboxy-terminal mutations of bile acid CoA:N-acyltransferase alter activity and substrate specificity. J Lipid Res 57:1133–1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Chen J, Hollister K, Sowers LC, Forman BM (1999) Endogenous bile acids are ligands for the nuclear receptor FXR/BAR. Mol Cell 3:543–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe M, Houten SM, Wang L, Moschetta A, Mangelsdorf DJ, Heyman RA, Moore DD, Auwerx J (2004) Bile acids lower triglyceride levels via a pathway involving FXR, SHP, and SREBP-1c. J Clin Invest 113:1408–1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia J, Wishart DS (2011) Metabolomic data processing, analysis, and interpretation using MetaboAnalyst. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics 34:14.10.1–14.10.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]