Abstract

We address the advantages and disadvantages of maintaining the mandatory use of masks in health centers and nursing homes in the current epidemiological situation in Spain and after the declaration of the World Health Organization on May 5, 2023 of the end of COVID-19 as public health emergency. We advocate for prudence and flexibility, respecting the individual decision to wear a mask and emphasizing the need for its use when symptoms suggestive of a respiratory infection appear, in situations of special vulnerability (such as immunosuppression), or when caring for patients with those infections. At present, given the observed low risk of severe COVID-19 and the low transmission of other respiratory infections, we believe that it is disproportionate to maintain the mandatory use of masks in a general way in health centers and nursing homes. However, this could change depending on the results of epidemiological surveillance and it would be necessary to reconsider returning to the obligation in periods with a high incidence of respiratory infections.

Keywords: Masks, Health centers and nursing homes, Spain, SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19

Abstract

Abordamos las ventajas e inconvenientes de mantener la obligatoriedad del uso de las mascarillas en centros sanitarios y sociosanitarios en la situación epidemiológica actual de España y tras la declaración de la Organización Mundial de la Salud el 5 de mayo de 2023 del fin de la COVID-19 como emergencia de salud pública. Propugnamos prudencia y flexibilidad, respetando la decisión individual de usar mascarilla y enfatizando la necesidad de su uso ante la aparición de síntomas sugestivos de infección respiratoria, en situaciones de especial vulnerabilidad (como inmunodepresión) o al attender pacientes con dichas infecciones. En la actualidad, dado el bajo riesgo observado de COVID-19 grave y la baja transmisión de otras infecciones respiratorias, creemos que es desproporcionado mantener el uso obligatorio de mascarillas de forma generalizada en centros sanitarios y sociosanitarios. No obstante, esto podría cambiar en función de los resultados de la vigilancia epidemiológica y habría que reconsiderar volver a la obligatoriedad en periodos con alta incidencia de infecciones respiratorias.

Palabras clave: Mascarillas, Centros sanitarios y sociosanitarios, España, SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19

INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic, particularly in its first waves that produced thousands of deaths in Spain, was an exceptional situation that made necessary, as in most countries, to take extraordinary measures. To limit the transmission of the infection and its serious consequences, measures were adopted such as confinement, the promotion of teleworking, the expansion of telemedicine, hand washing, diagnostic screening tests, and the widespread use of masks [1]. The latter, strongly supported by public health guidelines, was probably very useful in reducing transmission, although, given the simultaneous implementation of all of them, it is not easy to assess the individual effect of each one. The mandatory use of masks in all public spaces, designed to reduce viral transmission, has been progressively abandoned, but it persists in Spain in health centers and nursing homes.

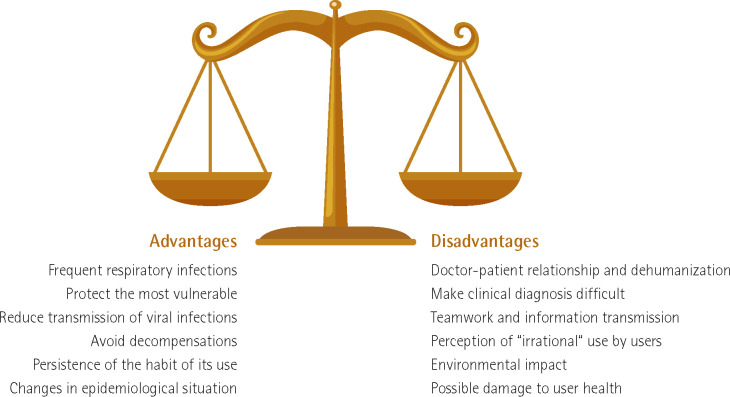

The current situation of widespread immunity acquired through vaccines and infections, combined with the successive mutations of the virus and the widespread availability of rapid diagnoses and effective treatments, has drastically reduced the incidence of serious SARS-CoV-2 infections. Although there are some exceptions [2], most authors agree that the mandatory use of masks should not be maintained indefinitely in hospitals, health centers, nursing homes, pharmacies, dental clinics, and other health centers [3-5]. What is more debatable is the moment to withdraw the obligation, accepting that this decision can be dynamic and reversible (Figure 1). In some countries with vaccination levels similar to Spain, it is no longer compulsory to wear a mask in these centers and this decision does not seem to have led to an increase in infections. Although different climatic, geographic, and epidemiological circumstances may make it difficult to extrapolate those experiences, SARS-CoV-2 infections now appear to be little more severe than those caused by influenza and other respiratory viruses [6].

Figure 1.

Advantages and disadvantages of maintaining the mandatory use of masks in health centers and nursing homes.

ADVANTAGES OF MAINTAINING THE MANDATORY USE

Viral respiratory infections are common and potentially serious. Health centers and nursing homes concentrate the population with the highest risk of severe COVID-19, subgroups that continue to have a relatively high risk of serious illness and death in the case of acquiring respiratory infections. In addition, nosocomial and healthcare-related infections by respiratory viruses are common and include not only SARS-CoV-2 but also influenza, respiratory syncytial virus, and others (human metapneumovirus, parainfluenza virus...). Acute respiratory viral infections can cause pneumonia and exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, decompen-sated heart failure, arrhythmias, acute coronary syndromes, and neurological events [7,8].

Reduced transmission of viral infections. Despite the fact that Jefferson et al [9] have recently questioned the degree of usefulness of masks with respect to the prevention of respiratory virus infections in the latest Cochrane Review, and other authors have questioned its usefulness in other circumstances such as its use in schools [10], several studies have shown that the proper use of masks reduces respiratory viral spread. In fact, its use by healthcare professionals can reduce nosocomial respiratory viral infections by up to 60% [11-14].

Habit persistence. The habit of wearing masks in health centers by professionals, patients and family members has been established, and it could be difficult to recover - in situations similar to those that occurred in the COVID-19 pandemic or due to the increase in other respiratory infections - if masks were no longer mandatory.

DISADVANTAGES OF MAINTAINING THE OBLIGATORY NATURE OF ITS USE

Doctor–patient relationship. Masks prevent seeing people’s faces. Its mandatory use has had a negative impact on communication, empathy and closeness, more pronounced in some subgroups such as children [15], the elderly, patients with impaired speech, mental health disorders or cognitive impairment, and patients who do not speak Spanish as their first language or with hearing loss [16-18]. Smiles and facial stimuli are not seen, and are necessary for the relationship with patients. The increased listening effort required when wearing masks is also associated with a higher cognitive load for patients and healthcare professionals [19,20]. The prolonged use of masks has contributed to the harmful trend, already present before the pandemic, of medical practice progressive dehumanization [21].

In some cases, the use of the mask can also make clinical diagnosis difficult, preventing or making it difficult to assess labial cyanosis and perioral infections, facial paralysis, and others [22].

Perception of healthcare and nursing homes users. Patients and, even more so, users of nursing homes perceive the mandatory use of masks as irrational when they are not mandatory in cafeterias, theaters and means of transport. They want to return to a true normality as soon as possible, as they already have in the “outside world”.

Teamwork. The advent of masks has also had a negative impact on interprofessional relations. Masks hide facial expression, can contribute to feelings of isolation, and negatively affect human connection [23]. The transmission of information is more difficult and it is not easy to perceive changes in mood [24]. In some situations, such as in the context of emergencies, masks can hinder clear communication between the professionals caring for the patient, facilitating errors. In addition, there are contexts such as clinical sessions and other training activities in which there is no contact with patients in which the mandatory use of the mask is not justified when there is a high level of vaccination among professionals and outside of the periods of increased circulation of respiratory viruses.

Environmental impact. The detrimental effect of respirator fragmentation on biomass quality is also a cause for concern. Disposable masks can reduce water quality and harm microalgae, inhibiting their growth [25]. In addition, masks contaminated by various microorganisms, after being used, are a potential danger to the environment [26].

Possible damage to the user’s health. Although the impact on the user’s health is minimal, some studies have shown possible side effects related to prolonged use of masks such as headache, irritation and dry eyes and skin conditions (appearance or worsening of acne and other facial dermatoses, including rosacea, dermatitis seborrheic, and irritant contact dermatitis) [27]. An impact on the subjective appreciation of effort when performing physical activities has also been described [28].

CONCLUSIONS

The individual decision to wear a mask in health centers and nursing homes must be respected and its use is recommended and necessary, as it was before the pandemic, for patients and health workers with symptoms compatible with respiratory infections, in situations of special vulnerability (such as immunosuppression) or when caring for patients with these infections. Given that the observed risk of severe COVID-19 is currently very low, and that there is no high transmission of other respiratory diseases, it seems disproportionate to maintain its mandatory use. However, mandatory use should be assessed - at least in spaces where there is contact with patients - seasonally, for example, from December to February, when the incidence of respiratory infections is high, with epidemic figures in the case of flu. The situation may change in the future and we need an approach that allows for the rapid and effective implementation of prevention policies that adapt to changing circumstances and that can be adopted by the governing bodies of these centers in epidemic situations.

FUNDING

None to declare

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Calderwood MS, Deloney VM, Anderson DJ , et al. Policies and practices of SHEA Research Network hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020;41:1127-1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalu IC, Henderson DK, Weber DJ, et al. Back to the future: Redefining “universal precautions” to include masking for all patient encounters. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2023:1-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klompas M, Baker MA, Rhee C, Baden LR. Strategic masking to protect patients from all respiratory viral infections. N Engl J Med. 2023. Jun 14. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2306223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martínez-Sellés M. El objetivo irrenunciable de volver a mirar la cara de nuestros pacientes. Madrid Médico 2023;169:4-5. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shenoy ES, Babcock HM, Brust KB, Calderwood MS, Doron S, Malani AN, et al. Universal masking in health care settings: a pandemic strategy whose time has come and gone, for now. Ann Intern Med. 2023. Apr 18:M23-0793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Portmann L, de Kraker MEA, Fröhlich G, Thiabaud A, Roelens M, Schreiber PW, et al. Hospital Outcomes of Community-Acquired SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Variant Infection Compared With Influenza Infection in Switzerland. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e2255599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klompas M. New insights into the prevention of hospital-acquired pneumonia/ventilator-associated pneumonia caused by viruses. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2022;43:295-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kwong JC, Schwartz KL, Campitelli MA, et al. Acute myocardial infarction after laboratory-confirmed influenza infection. N Engl J Med 2018;378:345-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jefferson T, Dooley L, Ferroni E, Al-Ansary LA, van Driel ML, Bawazeer GA, et al. Physical interventions to interrupt or reduce the spread of respiratory viruses. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023. Jan 30;1(1):CD006207. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006207.pub6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Juutinen A, Sarvikivi E, Laukkanen-Nevala P, Helve O. Face mask recommendations in schools did not impact COVID-19 incidence among 10-12-year-olds in Finland-joinpoint regression analysis. BMC Public Health. 2023;23:730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ambrosch A, Luber D, Klawonn F, Kabesch M. A strict mask policy for hospital staff effectively prevents nosocomial influenza infections and mortality: monocentric data from five consecutive influenza seasons. J Hosp Infect 2022;121:82-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aravindakshan A, Boehnke J, Gholami E, Nayak A. The impact of mask-wearing in mitigating the spread of COVID-19 during the early phases of the pandemic. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2022;2:e0000954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sung AD, Sung JAM, Thomas S, et al. Universal mask usage for reduction of respiratory viral infections after stem cell transplant: a prospective trial. Clin Infect Dis 2016;63:999-1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Damette O, Huynh TLD. Face mask is an efficient tool to fight the Covid-19 pandemic and some factors increase the probability of its adoption. Sci Rep. 2023;13:9218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shavit RC, Nasrallah N, Levi O, Youngster I, Shavit I. The influence of the type of face mask used by healthcare providers during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on the report of pain: a cross-sectional study in a pediatric emergency department. Transl Pediatr. 2023;12:890-896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cox BG, Tuft SE, Morich JR, McLennan CT. Examining listeners’ perception of spoken words with different face masks. Q J Exp Psychol (Hove). 2023. May 25:17470218231175631. doi: 10.1177/17470218231175631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hammer A, Coene M. The impact of COVID-19 on communicative accessibility and well-being in adults with hearing impairment: a survey study. BMC Public Health. 2023;23:652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seol HY, Jo M, Yun H, Park JG, Byun HM, Moon IJ. Comparison of speech recognition performance with and without a face mask between a basic and a premium hearing aid in hearing-impaired listeners. Am J Otolaryngol. 2023;44:103929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee E, Cormier K, Sharma A. Face mask use in healthcare settings: effects on communication, cognition, listening effort and strategies for amelioration. Cogn Res Princ Implic. 2022;7:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu X, Ma L, Yin Q, Liu M, Wu K, Wang D. The impact of wearing a KN95 face mask on human brain function: evidence from resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging. Front Neurol. 2023;14:1102335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wong CK , Yip BH , Mercer S, et al. Effect of facemasks on empathy and relational continuity: a randomised controlled trial in primary care. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14:200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gizzi MS, Mason RJ, Amaranto A. Surgical masks may hide neurological diagnoses. Case Rep Neurol. 2022;14:377-380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leos H, Gold I, Pérez-Gay Juárez F. Face masks negatively skew theory of mind judgements. Sci Rep. 2023;13:4950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li AY, Rawal DP, Chen VV, Hostetler N, Compton SAH, Stewart EK, et al. Masking our emotions: Emotion recognition and perceived intensity differ by race and use of medical masks. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0284108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khoironi A, Hadiyanto H, Hartini E, Dianratri I, Joelyna FA, Pratiwi WZ. Impact of disposable mask microplastics pollution on the aquatic environment and microalgae growth. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2023. May 31:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s11356-023-27651-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang L, Li S, Ahmad IM, Zhang G, Sun Y, Wang Y, et al. Global face mask pollution: threats to the environment and wildlife, and potential solutions. Sci Total Environ. 2023;887:164055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guleria A, Krishan K, Sharma V, Kanchan T. Impact of prolonged wearing of face masks-medical and forensic implications. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2022;16:1578-1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Kampen V, Marek EM, Sucker K, Jettkant B, Kendzia B, Strauß B, et al. Influence of face masks on the subjective impairment at different physical workloads. Sci Rep. 2023;13:8133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]