Abstract

There are over 500 human kinases ranging from very well-studied to almost completely ignored. Kinases are tractable and implicated in many diseases, making them ideal targets for medicinal chemistry campaigns, but is it possible to discover a drug for each individual kinase? For every human kinase, we gathered data on their citation count, availability of chemical probes, approved and investigational drugs, PDB structures, and biochemical and cellular assays. Analysis of these factors highlights which kinase groups have a wealth of information available, and which groups still have room for progress. The data suggest a disproportionate focus on the more well characterized kinases while much of the kinome remains comparatively understudied. It is noteworthy that tool compounds for understudied kinases have already been developed, and there is still untapped potential for further development in this chemical space. Finally, this review discusses many of the different strategies employed to generate selectivity between kinases. Given the large volume of information available and the progress made over the past 20 years when it comes to drugging kinases, we believe it is possible to develop a tool compound for every human kinase. We hope this review will prove to be both a useful resource as well as inspire the discovery of a tool for every kinase.

Keywords: chemical probe, druggable, kinase, kinase inhibitor, understudied kinase

Introduction

Amongst the nearly 20 000 proteins encoded by our genome [1], humans have around 500 protein kinases. How many of these kinases are druggable? Well of course the answer is ‘That depends!' If your question is ‘which kinases can be targeted by an inhibitor and this inhibition leads to favorable disease modification or amelioration in patients?' then it is fair to say no one knows the answer. Our level of understanding of the ins and outs of human biology and disease biology preclude any sweeping and confident ‘this will work for that' conclusions. If your question is ‘for which kinases can I make a high-quality inhibitor, so that I may test a target-based hypothesis?’ then we believe the answer may be close to all of them. Here we take a broad look at work that has been done and strategies that have been used to identify high-quality kinase inhibitors. With this, we can begin to understand what percentage of the human kinome is targetable with useful tools that can be used to test therapeutic hypotheses.

Kinase research has a long and rich history. The first kinase was discovered by Tony Hunter as the enzyme encoded by the ‘transforming gene' of Rous Sarcoma virus [2]. Thus, this remarkable study simultaneously identified protein phosphorylation as a player in oncogenesis, and laid the foundation of kinomics. A wonderful first-hand account of this discovery was published by Hunter in 2015 [3]. The account noted that this significant revelation was expeditiously disseminated during scientific gatherings, fostering open communication that contributed to subsequent breakthroughs. One such breakthrough disclosed that the EGF receptor demonstrated kinase activity, by way of phosphorylating tyrosine residues [4]. The author notes that by the conclusion of 1980 a total of four tyrosine kinases (TKs) had been brought to light, thereby facilitating a wealth of breakthroughs in the field of kinase research. In the subsequent decade, a multitude of additional kinases were discovered, accompanied by a profusion of publications which laid the foundation for our present conception of the ‘kinome' [5–7]. In 1995, a significant publication emerged, introducing the first classification system that organized the expanding list of kinases into families on shared characteristics such as sequence, substrates, and methods of regulation [8]. At this point the kinase discovery flood gates were wide open, with new kinase additions almost weekly! It is interesting to note that enthusiasm was so high that the authors suggested that the estimate (at the time) of a grand total of 1000 human kinases [9] would perhaps end up being too low [10]. We know now that this is not so, but one can sense the palpable excitement of discovery in the burgeoning kinase field. In 2002, the landmark paper ‘The Protein Kinase Complement of the Human Genome' by Manning was published [11]. With the human genome project nearing completion, this paper utilized and expanded on the 1995 classification system of Hanks and Hunter. They reported 518 putative protein kinases and added new kinases to the well-known groups and added new families to the kinome tree. The paper also features an intriguing section on catalytically inactive kinases, which sets the stage for today's burgeoning interest in what are now commonly referred to as pseudokinases. The kinase family framework provided in that 2002 review is in widespread use today.

The history of kinase inhibitor discovery parallels the timeline of new kinase revelations, as the therapeutic potential of kinase inhibition was recognized at an early stage. In this introduction, we will briefly touch upon three significant events in the inhibitor timeline. Firstly, in 1986, a notable paper reported that the natural product staurosporine inhibited protein kinase C, providing compelling evidence of potent kinase inhibition by a small molecule [12]. Then, in 1989, another publication showcased that while staurosporine and related compounds K-252 and UCN-01 were potent inhibitors of the aforementioned kinase from the 1986 study, they also exhibited potent inhibition against several other kinases [13]. They emphasized the fact that nonselective inhibitors, often referred to as promiscuous inhibitors, have some utility but are less suited, or perhaps not useful, for defining the functions of kinase targets. The authors presciently state that ‘for the molecular pharmacologist, protein kinase inhibitors of similar affinity but higher selectivity would be very useful'. It is evident that medicinal chemists embraced this challenge and have precisely furnished these types of invaluable tools to molecular pharmacologists. The desire for ‘similar affinity but higher selectivity’ has now been codified and embodied in all present efforts to deliver chemical probes for targets of biological interest. The third important event on the kinase inhibitor timeline is the landmark approval of the small-molecule kinase inhibitor imatinib by the FDA in 2001. This compound was developed for chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) with the kinase BCR-ABL fusion protein as its target [14]. During this period, numerous companies were engaged in kinase-related research, and the approval of imatinib only bolstered investment and resulted in a surge of FDA approved kinase inhibitors. Since Imatinib, there are now a total of 72 kinase inhibitors approved for the treatment of a variety of disease states [15]. It is now evident kinases are involved in the etiology and progression of many diseases. Cancers have predominantly been the focus of kinase research, owing to the pervasiveness of overexpression and mutations in kinase genes present in cancers [16]. However, there is increasing interest and emerging evidence for the role of kinases in other disease states as well, including inflammation and immunological diseases [17–25], neurological diseases [26–31], metabolic diseases [32–35], viral infections [36–40], fungal [41], and parasitic infections [42–47]. It should be noted that eukaryotic pathogens such as Plasmodium [48–50] and trypanosomatids [51] possess their own kinomes, divergent from humans, making them attractive targets for therapeutic intervention [52–54]. Consequently, kinase inhibitors have been developed and approved for non-cancer indications [55].

There is compelling evidence linking kinases to disease, and a growing number of kinases have achieved both commercial and clinical success. Despite this success and the great potential this target class holds, it is somewhat surprising that many kinases remain understudied. Twenty years ago, Hoffman and Valencia observed that certain genes received more attention than other genes, seemingly unrelated to the gene's importance, as measured by its centrality in protein interaction networks [56]. A few years later another publication noted that gene annotation, assessed by publications, illustrates the scientific community's preference for extensive study of a small, selective subset of genes rather than a genome-wide approach [57]. This same phenomenon was described for kinases more than a decade ago and remains true today [58]. The reasons for this wildly uneven discrepancy in research effort are unknown (and being studied) [59]. However, this could be partially attributed to a natural positive-feedback loop, where existing scientific research attracts additional investigation and resources to those targets which already possess sufficient evidence implicating them in crucial biological processes or disease states. Building on the work of others is a natural way to make progress. Moreover, securing funding for research built on a well-established published framework in a specific field may be easier than obtaining funding for research on topics with limited existing knowledge and uncertain future value. In this review, we begin by illustrating the disparities in kinase research through literature mining. We proceed to examine some of the remarkable progress achieved by kinase scientists, exemplified by the discovery of kinase chemical probes and the FDA approved kinase inhibitors employed in clinical settings. Next, we explore the types of resources, such as assays and crystal structures, required to identify useful tools to study kinases. Here, we make the case that the last 25 or so years of kinase research has removed most barriers for family-wide kinase inhibitor development.

It appears the uneven distribution of kinase research is not by necessity. Selectivity is a key challenge in kinase inhibitor discovery, exemplified by the plea described above to identify compounds with ‘similar affinity but higher selectivity'. Is kinase research skewed because it is just too difficult to attain the necessary selectivity? To answer this, we provide an overview of some of the methods through which medicinal chemists and chemical biologists have confronted and successfully met the selectivity challenge. While our examples are not exhaustive, they instill confidence that medicinal chemistry campaigns targeting understudied kinases can incorporate a range of selectivity modulating strategies that will likely yield useful, selective kinase inhibitors thus enhancing the druggability of the entire kinome. In conclusion, the data presented in this review illustrate that the distribution of research on kinases is unbalanced. Nevertheless, the knowledge accumulated over the past 30 years in this field has equipped us with the necessary expertise to develop tools for all kinases, paving the way for successful kinome-wide tool discovery. Such tools will be instrumental in validating targets for drug discovery programs.

Explored vs. underexplored kinases

While kinases have been the focus of scientific research for decades, there has been a bias toward studying a subpopulation of kinases which were linked to critical disease states early in their exploration as targets [60]. It has previously been estimated only 8% of the human kinome has been targeted for cancer therapeutic exploration, and 162 of the human kinases are considered ‘dark' by the NIH sponsored initiative, Illuminating the Druggable Genome (IDG) [61]. The IDG is an effort by the NIH to facilitate exploration into the underexplored members of the three major groups of genes that encode druggable proteins: G-protein coupled receptors, ion channels, and kinases. The dark kinase knowledgebase (DKK) is a repository for the tools and information collected from the IDG kinase data and resource generating center (DRGC) (https://darkkinome.org/). This initiative is a highly commendable effort to improve upon the equity of research across the kinome. The IDG effort is a manifestation of the view that kinases are druggable but work across the kinome is skewed towards a subset of kinases. We conducted a series of database searches to evaluate the current state of kinase research, providing an updated view of the existing disparities among the families of the kinome.

First, we queried the SciFindern (https://scifinder-n.cas.org, accessed from February 2023 to March 2023) search engine for individual kinases by their HGNC gene name and related synonyms to quantify citation levels for 536 kinases. We recorded total citation counts reported for every kinase. As a proxy for scientific interest in the kinase, we recorded citation counts in journal articles, and as a proxy for commercial interest in the kinase, we recorded the citation count in patents. To further investigate the interest in kinase inhibitor development, we recorded and compiled the citation count for five medicinal chemistry journals: Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry, European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry Letters, and ACS Medicinal Chemistry Letters. This comparison was purposefully chosen for the sake of this review, and the rationale for this decision stemmed from the idea that total citations compared with total citations from medicinal chemistry journals would provide an idea of how much of the available literature concerned the basic biology of the kinase target as opposed to drug discovery efforts for the target. To validate our search results, we compared the total citations from SciFindern and from PubMed and found the trends to agree (Supplementary Figure S1A). Detailed results for each kinase are provided in Supplementary Table S6, and we provide an analysis of the results below.

We stratified the generated data by kinase group (Supplementary Table S1). The proportion of the kinome each kinase group contributes was then compared with the proportion of total citations, citations in journal articles, patents, and medicinal chemistry papers each group includes, relative to the kinome-wide metric (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Distribution of citation counts across the kinome based on SciFindern search results relative to the size of the kinase group in the kinome.

Relative to the kinome-wide average, the CMGC and TK groups are very well-studied. Despite only making up 12%/17% (CMGC/TK) of the kinome, those two groups account for 55% (23%/32%) of total citations. Lipid kinases are also slightly overrepresented, making up 4% of the kinome but accounting for 8% of the citations (due to PIK3CA/PI3K being the singularly most cited kinase with nearly 80 000 citations). The AGC, CAMK, CK1, RGC, STE, TKL, and Other kinases are underrepresented in overall citations. This trend also holds when looking at the number of journal articles, and especially the number of medicinal chemistry papers. For the case of medicinal chemistry papers, the focus has clearly been on CMGC and TK kinases (22.9% and 38.3% of all medicinal chemistry papers, respectively). For patents, while there exists a general correlation between the number of citations in journal articles and patents kinome-wide (Supplementary Figure S1B), when broken down into groups, a slightly different trend emerged. The proportion of citations in patents for CMGC kinases and Lipid kinases are congruent with their proportion in the kinome. In contrast, the proportion of citations in patents mentioning TKs are significantly higher, where almost half of all citations in patents are for TKs. This highlights the extent to which TKs have been the focus for therapeutic purposes, especially in the pharmaceutical industry. It is interesting to note that despite the overall interest in CMGC kinases in the journal literature, it has not translated to as many patents when compared with the TKs. Two small groups of kinases, the CK1 and RGC groups, barely have any citations when compared with the other kinases.

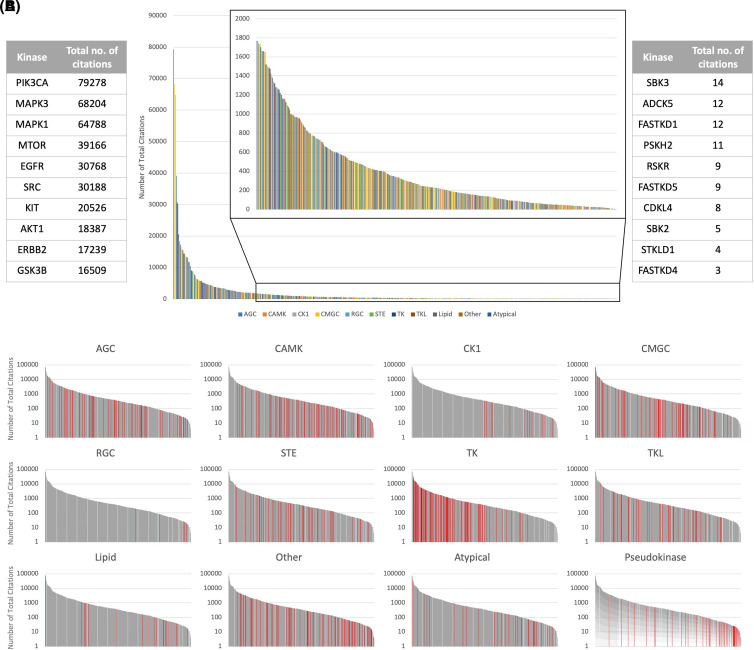

We have provided another view to illustrate the discrepancy between kinase groups (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table S2). When all members of the kinome are sorted in descending order according to the number of citations (lowest rank = most citations). We can see the TK group has the lowest mean rank of 147, indicating on average, members of the TK group tend to be more highly cited. The CMGC, STE, TKL, and AGC groups have a mean rank of 244–275, similar to the kinome-wide overall mean of 272, suggesting they are average in terms of their distributions of highly cited or infrequently cited kinases. In contrast, the CAMK group, Lipid kinases, Other kinases, and Atypical kinases have an above average mean rank of 301–346, indicating they are generally less cited amongst the kinome. At the very end of the spectrum, we have the CK1 and RGC kinase groups with very high mean ranks (391 and 458, respectively), indicating on average, these kinases are amongst the least cited. A surprisingly different story emerges when we look at the mean number of citations. Compared with the kinome-wide average, as expected, the TK kinases have a high mean number of citations. However, the CMGC kinases also have a high mean number of citations, despite their mean rank being only slightly better than average. This may be in part because of the presence of a few very highly cited CMGC kinases (MAPK1 and MAPK3). This demonstrates the CMGC group is varied in terms of their number of citations, with a few members of the family being very highly cited while others are relatively understudied. Also surprising is the high mean number of citations of the Lipid kinases. A closer inspection reveals this is due to the very high number of citations for PIK3CA. Most other Lipid kinases have a low citation count, as evident from the high mean rank. The other kinase groups tend to have below average number of citations, especially for the CK1 and RGC groups. When the kinome is broken down into kinases versus pseudokinases, we can see the mean rank of pseudokinases are very high (404) compared with kinases (256), with a much lower average citation count than kinases. The pseudokinase definition that was originally proposed by Manning and has since been expanded and determined our pseudokinase classification [11,62–64]. This strongly indicates pseudokinases are generally poorly studied and more effort is needed to illuminate their biological functions and develop appropriate chemical tools for their study. Of late, the importance and promise of pseudokinases has been recognized, as reflected by both primary literature and review papers [65,66].

Figure 2. Total number of citations for each kinase.

(A) Distribution of total number of citations across the kinome. Each vertical line represents a kinase, colored by their kinase group. The list of kinases is sorted in descending order based on total number of citations. (inset) Distribution after the top 100 kinases have been removed to illustrate the disparity between the studied and the understudied kinases. (left) The 10 kinases with the highest total number of citations. (right) The 10 kinases with the lowest total number of citations. (B) Distribution of the total number of citations for kinases across the 11 major kinase groups, and for pseudokinases (across all kinase groups). Each vertical line represents a kinase, colored red for the specific kinase group, and gray otherwise. These plots are plotted on the logarithmic scale for better visualization.

From the data analyzed here we observe that the current state of kinase research continues to show a publication disparity across the kinome. The kinases in the top 20% in terms of citations have been cited 844 468 times, while the kinases in the bottom 20% of the kinome have been only cited 4 240 times. The CMGC and TK families have received the most attention, and perhaps one can argue that at least some of this bias is due to broad implication of family members in disease pathology. Nevertheless, many of the understudied kinases certainly have biological and perhaps clinical importance [61,67,68]. A degree of bias to focus additional scientific research on targets which have been worked on or have been validated as drug targets is understandable. New papers raise new questions that can be addressed by additional work. For example, approved drugs demonstrate value in the clinic, over time resistance arises, and this necessitates the development of new drugs for the same targets. The scientific community has demonstrated that kinases are tractable targets and that useful medicines can emerge from drug discovery efforts. It seems likely that opportunities await in the kinases on the right-hand side of Figure 2. With more than 70 approved medicines from research biased towards roughly 25% of the kinome, what can be achieved if high-quality tools are available for every kinase? How many targets from the understudied kinome will prove useful for treating disease?

Kinase coverage with high-quality chemical probes

As another way of demonstrating progress towards ‘drugging the kinome’, in this section we focus on kinase chemical probes. There are multiple means of interrogating the kinome, but to effectively interrogate the role of a kinase as a preclinical target, a high-quality chemical probe complements the commonly used genetic methods of gene knockout and knockdown studies. Chemical probes are powerful small-molecule tools used to help validate a target for preclinical drug discovery, meant to provide insight into multiple aspects of a target protein's role in disease. A set of guiding principles have been previously established concerning the use of chemical probes to discern the biological role of a target [69–72]. Briefly, these principles explain that a high-quality chemical probe should be potent against the target, it should demonstrate dose-dependent inhibition on target activity in cells at useful (lower is better) concentrations, be well annotated (in terms of selectivity within the target family), and should be readily available to the scientific community. In addition, the availability of a negative control compound, defined as a structurally related compound that is inactive at the target of interest, is highly desirable. To our knowledge, there are three resources for obtaining open-source chemical probe sets. Through these sources, the Structural Genome Consortium (SGC), the Gray Lab at Stanford, and the OpenME portal, interested researchers can get access to probe sets for use as discovery tools [73–75].

For the purposes of this review, we chose the definition of a chemical probe utilized by the SGC to outline what we consider to be a high-quality chemical probe (Box 1) [70]:

| Box 1: Definition of a Chemical Probe |

|---|

| 1. The chemical probe is a potent inhibitor of its primary target, ideally with an in vitro potency in biochemical assays <100 nM. |

| 2. The chemical probe demonstrates selectivity over other proteins, with at least a 30-fold window over closely related targets in the same protein family. |

| 3. The chemical probe demonstrates on-target activity in cellular assays at or below a concentration of 1 µM. |

| 4. A close analog of the chemical probe that lacks activity on the primary target is available as a negative control compound. |

| 5. The chemical probe is publicly available without restrictions on its use. |

We looked in the list of SGC chemical probes and the Chemical Probes Portal to identify available kinase chemical probes. One can identify other probes from detailed searches in the primary literature, but we opted for this simpler search where the quality of the probes has been curated by experts. The Probes Portal uses a four-star rating system to rate all chemical probes that have been submitted to the portal and ranks the compounds by their suitability for use as a tool to interrogate the target in question. We have chosen to include only those probes from the Probes Portal database which were assigned a three-star or higher rating in cells. The Probes Portal defines any probe with a three-star or better rating as ‘Best available probe for this target, or a high-quality probe that is a useful orthogonal tool [76].' During data curation, the list of probes was double checked for potential redundancies due to, for example, alternate kinase names being used. The final list of 3- and 4-star kinase probes from the Probes Portal along with the list of SGC-approved probes should provide sufficient information to infer the state of available chemical probes for the study of kinases. Details on the compounds pulled from these searches are available in Supplementary Table S7. Using this methodology, we have identified 132 kinase chemical probes, with at least one high-quality chemical probe for 129 of 536 human kinases. This means that a high-quality chemical probe is available for approximately 24% of the human kinome. Multiple probes are available for several kinases. This redundancy, having probes in different structural classes, adds value. When a phenotypic result is recapitulated with two or more different probes for the same target, this builds confidence that modulation of the target is indeed driving the observed phenotype.

Our results (Table 1 and Supplementary Figure S2) show approximately half (107 out of 208) of the probe-kinase pairs are found in the top 20th percentile (107 out of 536) kinases, whereas for the bottom 20th percentile of kinases no probe-kinase pairs were found. There is a sharp drop-off in the number of probe-kinase pairs after the top 30th percentile. These results clearly illustrate the dearth of high-quality chemical tools for much of the kinome. Even for the more studied kinases, there is not always a chemical probe available, highlighting an opportunity for additional impactful work in the field of chemical probe development.

Table 1. Availability of probes for individual kinases stratified by citation count percentile.

| Percentile | Number of probe-kinase pairs | Cumulative number of probes-kinase pairs | Number of kinases with at least 1 probe | Cumulative number of kinases with at least 1 probe | Proportion with at least 1 probe (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 90 | 58 | 58 | 31 | 31 | 58.5 |

| 80 | 49 | 107 | 28 | 59 | 51.9 |

| 70 | 29 | 136 | 20 | 79 | 37.7 |

| 60 | 8 | 144 | 7 | 86 | 13.0 |

| 50 | 25 | 169 | 15 | 101 | 27.8 |

| 40 | 16 | 185 | 11 | 112 | 20.8 |

| 30 | 16 | 201 | 11 | 123 | 20.4 |

| 20 | 7 | 208 | 6 | 129 | 11.3 |

| 10 | 0 | 208 | 0 | 129 | 0.0 |

| 0 | 0 | 208 | 0 | 129 | 0.0 |

A probe-kinase pair is identified as any kinase target that was annotated as the target of a probe by the SGC and/or Chemical Probes Portal.

Kinome coverage by FDA approved medicines

Kinases were identified as potentially druggable targets in the 1980s. At the time, the feasibility of designing ATP-competitive inhibitors with selectivity between kinases was contested (or sometimes considered a nearly insurmountable barrier) due to the generally well-conserved ATP-binding pocket across the kinome. In 1995, Japan approved the first small-molecule kinase inhibitor, Fasudil, which targets ROCK1 and ROCK2 to treat cerebral vasospasm [77]. Four years later, the natural product Sirolimus (rapamycin) became the first FDA approved kinase inhibitor [78]. Used to prevent organ transplant rejection, Sirolimus inhibits the mammalian target of Rapamycin (mTOR) [79], which has become a popular target as it is implicated in many disease states [80]. Two years later in 2001, Imatinib became the first small-molecule kinase inhibitor approved by the FDA [81].

A detailed discussion on each of these FDA approved inhibitors is out of scope here (and well-reviewed elsewhere by Roskoski R Jr., 2022 [82] and 2023 [15]), but several details are important. Out of the 72 FDA approved kinase inhibitors, 64 of them target the ATP-binding site [83], in part because working in this site provides an opportunity to discover new drugs from screening ATP-competitive inhibitors developed for previous kinase programs. Generic assays can be configured, and starting points for a new kinase can be found from inhibitor sets made for previous programs. A huge number of heterocyclic cores have been used to make kinase inhibitors [84,85], and many recapitulate elements of the adenine core of ATP. Aminopyrimidines and quinazolines are among the most prominent scaffolds, found in 38% of approved drugs. These ATP-competitive inhibitors (Type I and Type II inhibitors) comprise most FDA approved kinase inhibitors. Another subset of FDA approved kinase drugs function as allosteric inhibitors (Type III). Although the mechanism of action of Sirolimus was unknown at the time of discovery, it was later identified as an allosteric inhibitor [79,86]. A third class of approved compounds are covalent inhibitors (Type V), which form an irreversible bond with an active site cysteine residue. Covalent inhibitors are gaining prominence. Afatinib was the first and garnered approval in 2013, quickly followed by Ibrutinib [87]. In total, eight current FDA approved kinase drugs function as covalent inhibitors [88]. We discuss more on these important classes in the section on strategies for enhancing selectivity.

The landmark approval of Imatinib encouraged a rapid increase in medicinal chemistry campaigns targeting kinases. The increased effort has borne substantial fruit, as depicted in Figure 3. In the just over 20 years since Imatinib's approval, 71 more kinase inhibitors have been approved. One key takeaway is that in the last 6 years, at least five kinase inhibitors were approved by the FDA each year. This represents astounding consistency, wonderful progress, and provides a clear demonstration of the druggability of this protein class. With such a track record, it should not be surprising that hundreds of other prospective drugs are currently under clinical investigation.

Figure 3. FDA approved drugs by year of approval and main kinase targeted.

To dig a bit deeper into these approvals and ongoing clinical trials, data on FDA approved drugs and their targets was gathered from PKIDB [89], a continually updated database. When no targets were listed by the PKIDB, DrugBank (an online database for drug and drug-target information), PubChem (an open database for small molecules by the NIH), and Clinicaltrials.gov (a web-based resource that provides access to clinical trials information) were used to supplement, and if no targets were annotated on these databases, entries were manually added based on literature searches (Supplementary Tables S6 and S8). Importantly, these sites list all kinases that are inhibited as ‘targets,' not just the specific kinase or kinases the drug was designed to target. Therefore, even though there are only 72 FDA approved drugs, there are 186 total drug-kinase pairs. With all this in mind, 63 unique kinases are listed as targets, giving coverage of just under 12% of the kinome. KIT, KDR, and EGFR are the most repeatedly targeted individual kinases, with 13, 12, and 11 approved drugs for each, respectively. Out of the 11 major kinase groups, only RGC and CK1 lack a small-molecule kinase inhibitor targeting one of their kinases. The TK group is the most covered overall, with an FDA approved small-molecule inhibitor available for nearly 50% of its kinases (Table 2).

Table 2. Availability of FDA approved drugs for each kinase group.

| Group | Number of kinases | Total number of approved drug-kinase pairs | Mean number of approved drug-kinase interactions per kinase | Number of kinases with at least 1 approved drug | Proportion of group with at least 1 approved drug (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TK | 90 | 186 | 2.07 | 44 | 48.9 |

| Lipid | 19 | 6 | 0.32 | 3 | 15.8 |

| TKL | 42 | 10 | 0.24 | 3 | 7.1 |

| CMGC | 64 | 10 | 0.16 | 4 | 6.3 |

| STE | 48 | 9 | 0.19 | 3 | 6.3 |

| AGC | 63 | 6 | 0.10 | 2 | 3.2 |

| Atypical | 32 | 1 | 0.03 | 1 | 3.1 |

| CAMK | 74 | 2 | 0.03 | 2 | 2.7 |

| Other | 80 | 1 | 0.01 | 1 | 1.3 |

| CK1 | 12 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.0 |

| RGC | 5 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Overall | 529 | 231 | 0.44 | 63 | 11.9 |

These data demonstrate that the approved medicines largely target well-studied and characterized kinases (Table 3 and Supplementary Figure S3). Among the 53 kinases comprising the 90–100th percentiles of cited kinases, 56.6% of them have at least one approved drug. For kinases in the 70–90th percentiles, this number drops rapidly to around 20%. The understudied kinases, which constitute the bottom 60% of the kinome, have minimal drug representation. If the criteria are widened to include investigational drugs, the contrast becomes even more stark, with 85% of the 90–100th percentile having at least one approved or investigational drug (Supplementary Figure S4). Kinases in 60–90th percentiles range from 20% to 40% covered, and the remainder are under 10%. Qualitatively, this observation is unsurprising. A drug's progression through clinical trials and subsequent approval generates heightened scientific interest in the drug and its targets, establishing a cycle that leads to increased citations. Nonetheless, this finding adds to the evidence of the existing research disparity within the kinome. Our hypothesis suggests that providing tools for poorly studied kinases will facilitate the research necessary to identify which kinases, within the bottom 60th percentile of citations, can emerge as valuable drug discovery targets.

Table 3. Availability of an FDA approved drug for individual kinases stratified by citation count percentile.

| Percentile | Number of approved drug-kinase pairs | Cumulative number of approved drug-kinase pairs | Number of kinases with at least 1 approved drug | Cumulative number of kinases with at least 1 approved drug | Proportion with at least 1 approved drug (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 90 | 142 | 142 | 30 | 30 | 56.6 |

| 80 | 32 | 174 | 11 | 41 | 20.4 |

| 70 | 31 | 205 | 12 | 53 | 22.6 |

| 60 | 12 | 217 | 4 | 57 | 7.4 |

| 50 | 3 | 220 | 3 | 60 | 5.6 |

| 40 | 10 | 230 | 2 | 62 | 3.8 |

| 30 | 0 | 230 | 0 | 62 | 0.0 |

| 20 | 0 | 230 | 0 | 62 | 0.0 |

| 10 | 1 | 231 | 1 | 63 | 1.9 |

| 0 | 0 | 231 | 0 | 63 | 0.0 |

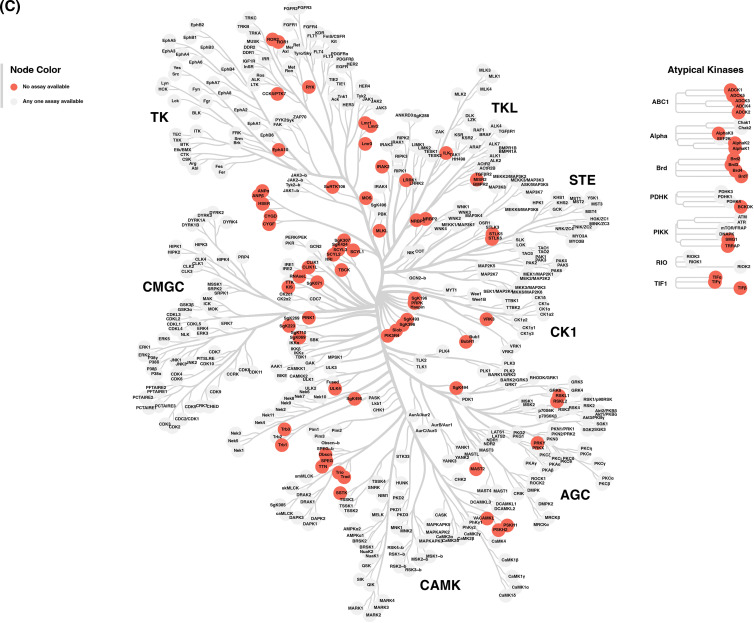

Identifying a kinase inhibitor drug compound presents different challenges to identifying a kinase inhibitor probe compound. Figure 4 illustrates progress in developing both probes and drugs for every kinase across the kinome. Successful drugs necessitate specific properties, including potency, selectivity, pharmacokinetic properties, safety, and scalability of chemical synthesis. They must also navigate clinical trials, which present scientific, logistic, and strategic challenges. Furthermore, the estimated cost to bring a single drug to market ranges from under a billion to more than two billion dollars [91], a significant investment which requires confidence in the candidate therapeutic and target. The critical challenge for probes is designing requisite selectivity for the kinase of interest. Drugs differ in that drugs may not necessarily require selectivity and the effectiveness of certain drugs may be attributed to polypharmacology [92]. Engineering in the selectivity required of a chemical probe is especially complex with kinases, as members of the same family can have ATP-binding pockets with very high sequence homology. Medicinal chemists have risen to this challenge employing numerous strategies to design selective compounds (See below, ‘Kinome wide tool generation: Strategies to impart selectivity’ section). Among the main kinase groups, the CMGC group has the highest proportion of kinases with available probes (Figure 5 and Supplementary Figure S5), but not the most drugs. Overall, most groups possess more probes than drugs (Figure 5 and Supplementary Figure S5) aligning with the costs and challenges of drug development. Overlap exists between kinases with probes and drugs, as probes can serve as precursors to medicines. However, availability of a probe is not a prerequisite for having an approved or investigational drug for a given kinase. Many kinases with no probes have an FDA approved drug targeting them, and conversely, many kinases with multiple probes available have no small-molecule inhibitor approved or in clinical trials.

Figure 4. The availability of chemical probes and FDA approved drugs for each individual kinase.

Kinases with both a drug and probe are colored in green, kinases with a drug but no probe are blue, kinases with a probe but no drug are yellow, and kinases with neither are gray. This kinome tree was created using CORAL [90].

Figure 5. Comparison between distributions of chemical probes and drugs across kinase groups.

Comparison between the proportion of a kinase group with at least one chemical probe versus the proportion of that group with one approved drug (A) or approved or investigational drug (B).

What is needed to make useful kinase inhibitor tools for testing a biological hypothesis?

Chemical probes are invaluable for studying kinases, but their coverage of the kinome remains inadequate. The development of chemical probes, although not as financially demanding as the development of a drug, is no trivial task. Chemical probe development requires resources such as target based assays, cellular assays, means to assess selectivity, and the scientific expertise to efficiently guide compound design. In this section, we discuss resources available for inhibitor development for each kinase. This information highlights kinases with adequate available resources to facilitate probe discovery, and kinases requiring additional work be done to establish the necessary resources for probe development.

Availability of a crystal structure

While not mandatory for chemical probe discovery, crystal structures facilitate the rational design of chemical probes by providing atomic-level details of the kinase amino acid sequence, and the unique features of the folded kinase. The first kinase structure, published in 1991, depicted the crystal structure of the catalytic subunit of PKA bound to a peptidic analog inhibitor [93]. This landmark paper introduced the now familiar bilobal structure, with the ATP-binding site described as a ‘deep cleft between the lobes'. The authors pointed out the conserved catalytic core shared by (at the time) more than 100 kinases. This observation hinted at the potential for an active site-based strategy to enable drug discovery efforts for the entire kinase family. The first TK structure, the kinase domain of INSR, was reported just a few years later [94]. This revealed similarities with serine-threonine kinases such as the distinct bilobal feature of kinases and shared catalytic residues, but also highlighted differences. Since these initial reports, more than 6000 kinase crystal structures have been solved and deposited in the PDB [95,96]. Crystallography has continued to play an important role in building our understanding of the way kinases are regulated, how they phosphorylate their substrates, how they participate in complex signaling cascades, and how an ever-increasing number of inhibitors with different modes of action bind to kinases potently and selectively. A recent review from the Taylor lab (with two authors who were on the publication reporting the first kinase crystal structure) highlights many of the kinase discoveries made possible through careful structural elucidation and mechanistic studies [97].

From structures, size and shape of pockets can be ascertained, important interactions of inhibitors with active sites (or allosteric sites) become apparent, and by comparison of different structures, potential strategies for enhancing selectivity between kinases can be inferred. The availability of crystal structures enables drug discovery technologies such as molecular docking simulations, molecular dynamic simulations, and fragment-based drug design. All these methods are useful for inhibitor discovery, as they can enable informed choices regarding which type of compounds will likely bind and interactions likely to occur for a particular kinase. For these reasons, we chose to tabulate the available crystal structures for kinases on the Protein Database (Supplementary Tables S3 and S6).

Kinases generally are amenable to crystallography, with 312 kinases (59%) having at least one crystal structure available in the PDB (Supplementary Table S3 and Figure 6). The availability of crystal structures across kinases from different groups are similar, with the exceptions of the CK1 group where almost all kinases have a crystal structure, and the RGC group where no kinase has a crystal structure. This suggests that no one group is more challenging for crystallographic efforts, and we believe it is possible to solve crystal structures for every kinase.

Figure 6. Visual representation of PDB structure availability based on kinase group.

We note that crystal structures tend to be available for the more well-studied kinases as compared with the kinases with fewer citations (Supplementary Figure S6). This is perhaps unsurprising since the citation count reflects general interest in the kinase and incentive to solve a crystal structure. Crystal structures are also generated during drug and probe discovery campaigns, which tend to be conducted for the more well-studied kinases. We thus compared the availability of PDB crystal structures between kinases with approved drugs and probes versus kinases with no approved drugs and probes (Supplementary Table S4 and Figure 7). We infer from this data that the availability of crystal structures facilitates the development of drugs, or that crystallographers focus on kinases that are known drug targets. Once interest in a target has risen to the level that the kinase becomes the subject of a drug discovery program, crystallography is often in place, or efforts are made to enable crystallographic determination of binding mode. The results of the comparisons emphasize the argument that those kinases with no crystal structures available are in an under-privileged position with respect to potential medicinal chemistry campaigns compared with those with solved crystal structures. Additionally, recent advances have shown how crystal structures can be used to exploit small differences in the ATP-binding pocket to generate selectivity, even though this region may appear structurally very similar [98]. We discuss more about specific strategies for generating selectivity below, many of which are enabled by crystal structures.

Figure 7. Comparison between availability of a probe or drug and availability of a crystal structure.

Availability of an assay

While crystal structures represent a highly significant way of bringing a previously understudied kinase to a more accessible place for ligand design, there are other crucial aspects of kinase ligand discovery and optimization which must be in place. Availability of assays is one major consideration. Any medicinal chemistry campaign to develop an inhibitor of a kinase requires robust assays to measure the potency and selectivity. There are many different assays to measure kinase activity, but they may be broadly grouped into cell-based or cell-free assays, and binding assays or enzymatic assays. Several reviews on the advantages, disadvantages, strengths, and limitations of kinases assay types are available [99–105]. Here we have tabulated which kinases may be assayed using common commercially available assays (Supplementary Table S6). One commonly used cell-free assay for kinome-wide selectivity screening is the Eurofins DiscoverX KinomeScan competitive binding assay [106–108]. Both Eurofins and Reaction Biology Corporation (RBC) offer enzymatic assays that measure phosphorylation of a substrate [109,110]. For a sampling of cell-based assays, we have looked at the NanoBRET assay by Promega which measures cellular target engagement [103,111,112], and the RBC cellular phosphorylation assay [110].

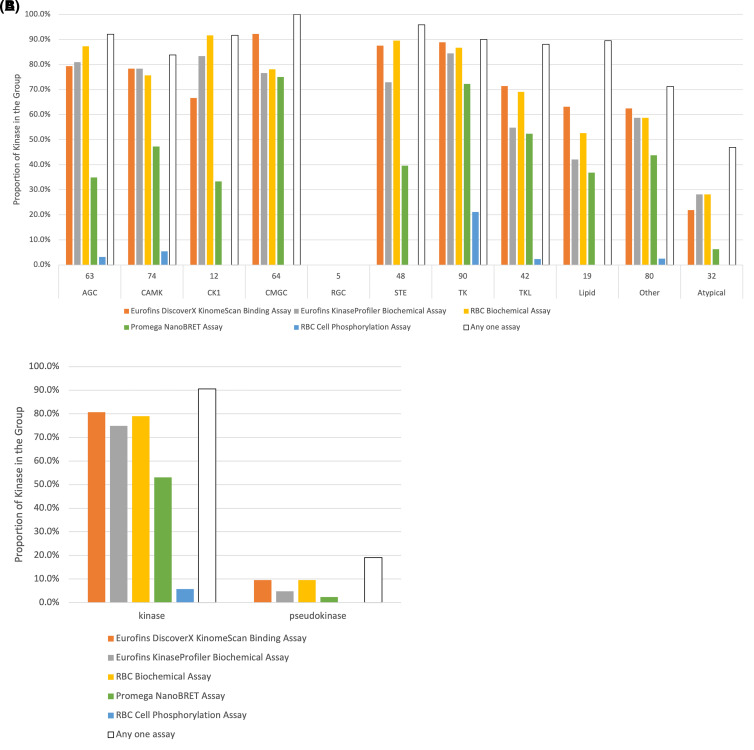

The distribution of the kinases having at least one commercial kinase assay when sorted by citation count (Figure 8A,B) shows that there is relatively good coverage of kinases by at least one assay for most of the kinome. All kinases in the top 10th percentile have at least one assay available. As citation count decreases, for the kinases in the 30–90th percentile there remains 90% of the kinases with an assay. Only below the 30th percentile did we observe a drop-off in assay availability. Figures containing similar plots of kinome-wide distribution of assay availability of each individual assay are available in Supplementary Figure S7.

Figure 8. Assay availability of each kinase, ranked by total number of citations.

(A) Assay availability across the kinome. Each vertical line represents a kinase, colored by whether any one assay is available. The list of kinases is sorted in descending order based on total number of citations. The plot is plotted on a logarithmic scale for better visualization. These assays included are Eurofins DiscoverX KinomeScan Binding Assay, the Eurofins KinaseProfiler Biochemical Assay, the RBC Biochemical Assay, the RBC Cell Phosphorylation Assay, and the Promega NanoBRET cellular target engagement assay. (B) Assay availability by percentile of kinome when ranked based on total citation count.

We next examined the distribution of kinase groups and availability across the groups of each commercial assay type (Supplementary Table S5 and Figure 9A). The three cell-free assays (the enzyme assay or binding assays often used to drive medicinal chemistry structure activity relationship efforts) generally have good coverage across the major kinase groups, with approximate coverage of 70–90% of the AGC, CAMK, CK1, CMGC, STE, and TK kinases. The TKL, Lipid, and Other kinases are slightly less covered by the cell-free assays. Atypical kinases are typically poorly covered and the small group of RGC kinases has no assays available. The generally high availability of cell-free assays presents a positive outlook for the druggability of the kinome and suggests that the design of assays is not a limiting feature for kinome-wide probe discovery.

Figure 9. Assay availability by kinase group or classification.

(A) Assay availability by kinase group. (B) Assay availability by kinase or pseudokinase classification. (C) A kinome tree illustrating the distribution of kinases without a commercial assay. Each red circle corresponds to a single kinase that currently has no commercial assay available. This kinome tree was created using CORAL [47].

Quantification of enzyme inhibition or binding to the kinase of interest is a key feature of probe programs, but as a key component of chemical probe criteria, evaluation of compounds in a cellular environment is critical. Our analysis of available assays shows that there is a much lower total coverage of the kinome with commercial cell-based assays. RBC provides numerous in-cell phosphorylation assays, but there is a strong bias for the TK group of kinases and generally very low coverage (0–5%) of other kinase groups. The Promega NanoBRET assay was developed as a generic approach to evaluate in-cell target engagement and has the potential to cover the entire kinome [103,112]. Despite the higher coverage of CMGC and TK kinases, the NanoBRET assay provides at least some coverage of all kinase groups. Just like the cell-free assays, the Atypical kinases are very poorly covered by this assay. Cell-based assays reveal more about the properties of a kinase inhibitor than a cell-free assay for a multitude of reasons: cell-based assays more closely mimic the native environment of the kinase, with cellular ATP concentrations and the presence of relevant binding partners, as well provide information about the permeability of inhibitors into cells. Thus, the lower availability of cell-based assays is an area with room for improvement.

Despite the incomplete coverage of individual assays, together the five assays cover the kinome very well, primarily the three cell-free assays. All major kinase groups except the RGC kinases have at least 80% of the group covered by at least one assay. Impressively, every kinase in the CMGC group has at least one assay available. We next examined the distribution of kinases which do not have an assay available (Supplementary Table S5 and Figure 9C) and observed that the majority of kinases without any assay belong to the Other kinase and Atypical kinase groups. Further work still needs to be done to better establish assays for this subset of the kinome.

We have found a stark contrast between assay availability for kinases and pseudokinases (Supplementary Table S5 and Figure 9B). While 91% of kinases are covered by at least one assay, only eight pseudokinases (19% of all pseudokinases) are covered by one commercially available assay. Interestingly, of these eight pseudokinases, EIF2AK4 is available in both Eurofins and RBC enzymatic assays; KSR1, KSR2, and PEAK1 are available in the RBC enzymatic assay; and TRIB2 is available in the Eurofins enzymatic assay. This suggests that these five pseudokinases have detectable and assayable enzymatic activity, and thus demonstrates that assay development for some pseudokinases with enzymatic activity is still possible. It is worth noting that catalytic activity of psuedokinases may be residual or disputed in some cases. The development of binding assays for pseudokinases is also still possible, as evident from the availability of the DiscoverX KinomeScan assay for CASK, EPHB6, ERBB3, and EIF2AK4, and the NanoBRET assay for EIF2AK4. Protein production methods have been described for many pseudokinases, and these proteins can be used to configure assays. With methods for protein production and the ability to create assays, an increased rate of discovery of enabling tools to validate pseudokinases as drug targets seems likely. For a more detailed discussion on assay development for pseudokinases, readers are encouraged to consult volume 667 of Methods in Enzymology, titled ‘Pseudokinases' [113].

As anticipated, the availability of assays for a kinase enables medicinal chemistry research to develop inhibitors (Figure 10). There are very few citations for kinases without any available assay in the five medicinal chemistry journals we investigated. Except for the bromodomains BRD2, BRD3, and BRD4 (referred to as part of the Atypical kinase family in the original Manning paper [11], but not considered to have kinase activity now), every kinase without an available assay has <10 combined citations in the five medicinal chemistry journals. Sixty-eight of these kinases (77%) have no citations in any of the five journals at all.

Figure 10. Impact of assay availability on number of citations in medicinal chemistry journals.

Interestingly SMG1 has a chemical probe available, SMG1i, despite being one of the kinases with no commercial assays. SMG1i was developed by Pfizer, which established their own cell-free enzymatic assay for evaluating compound activity [114,115]. Clearly, this example demonstrates that assays can be developed even for kinases with no commercial assay availability.

Having an assay for every kinase is of course critical for the long-term objective to develop a tool molecule for every kinase. Fortunately, being understudied does not preclude assay development. To illustrate, the kinase CDKL4 is an understudied kinase with only eight total citations. CDKL4 has no probe, no crystal structure, and no medicinal chemistry citations. Despite being among the least studied kinases in the kinome, Eurofins has included CDKL4 in their KinaseProfiler assay. We speculate that the ability to generalize kinase assay production in particular formats, and the effort that went into building kinase panels in these generalized assay formats, enabled assays for many still understudied targets like CDKL4. Availability of assays for many understudied kinases provides an opportunity and a much needed first step for probe identification.

Druggability by chemoproteomic assays

Chemoproteomic approaches are also commonly used to assess kinome-wide binding. Although not commercially available, these methods are noteworthy as valuable resources for effective kinome-wide profiling. They can be utilized for hit identification in screening campaigns, repurposing existing inhibitors as hits for other kinases, and conducting selectivity and off-target analysis during the optimization process.

One prominent example is Kinobeads [116–118]. Kinases may be pulled down from cell lysate using an array of immobilized kinase inhibitors. A test compound can then be assayed through incubation with the cell lysate. Dose-dependent competitive elution of a kinase, detected by mass spectrometry (MS), allows for the determination of relative binding affinity. While this technology has been demonstrated numerous times in literature, we have chosen an exemplar application of Kinobead technology for the evaluation of 243 clinically relevant kinase inhibitors [116] to further illustrate ligandability (as a prelude to druggability) across the kinome. This chemoproteomic method is distinct from and complementary to the commercial assays we have described. The utility of Kinobeads to illustrate druggability of each kinase is two-fold: (1) any kinase successfully pulled down by the immobilized inhibitors is proof that binding to at least one of the immobilized inhibitors is possible; (2) if one of the test compounds is able to potently compete with the pull down of any kinase, it directly suggests the kinase may be targeted by the investigated inhibitor.

In this study, approximately half the kinome (263 kinases) was successfully detected in pulldown experiments. The distribution of kinases across kinase groups (Supplementary Figure S8) shows kinases across the AGC, CK1, CMGC, STE, TK, TKL, and Lipid kinase groups are amenable to being pulled down, with approximately half of each group being pulled down. Kinases from the STE group surprisingly tend to be more amenable to pulldown, with almost 70% of the group pulled down. However, the kinases from the CAMK group, Atypical kinases, and Other kinases tend to be pulled down at a lower frequency, while none of the RGC kinases are pulled down. A kinase might not be pulled down for several reasons, including low expression in the chosen cell line, or simply that none of the immobilized inhibitors bind to the kinases in question. This study demonstrated that 221 of the pulled down kinases have at least one drug-target interaction with an apparent Kd of ≤1 μM out of the 243 inhibitors tested. The trend of the distribution of these kinases across the kinase groups largely mirrors the trend for the distribution pulled down, with STE kinases slightly higher in the proportion of kinases with such an interaction. One notable exception in the trend is the significantly lower number of potent drug-target interactions with the Lipid kinases. Only 3 of the 10 Lipid kinases pulled down have a compound with apparent Kd <= 1 µM, although we note this could be due to the choice of the compounds screened in the panel of 243 compounds.

Another whole-cell chemoproteomic technique is the cellular thermal shift assay (CETSA) [119,120]. CETSA was initially designed and utilized for evaluation of cellular target engagement of various kinase inhibitors [119]. CETSA relies on the basic principle that binding of a compound to a target modulates the thermal stability of the target, measured by the amount of soluble protein during thermal denaturation. When combined with MS to quantify all soluble proteins within a lysate, this may also be used for target identification. This technique is also named MS-CETSA or thermal proteome profiling (TPP) [121,122]. This strategy is complementary to Kinobeads. While TPP can identify kinases which fail to bind to immobilized inhibitors in Kinobeads experiments, Kinobeads is able to identify kinases which TPP may miss because of insufficient solubility in absence of a ligand. One additional advantage of TPP is its ability to identify non-kinase targets [123]. TPP has been demonstrated for the promiscuous kinase inhibitors staurosporine and GSK3182571 [124]. 175 kinases have been quantified through TPP, of which a significant thermal shift was induced by staurosporine for 51 of them [124]. Clearly, this study has demonstrated that these 51 kinases are indeed druggable in a cellular context. Demonstrating druggability in a cellular context is a unique advantage of this technique because it represents physiologically relevant concentrations of the kinase, ATP, as well as other binding partners. As far as we are aware, a large screen of multiple kinase inhibitors using TPP (similar to that using Kinobeads) has not been reported, but we are confident that this strategy would be able to demonstrate druggability of the kinome.

Kinome-wide tool generation: strategies to impart selectivity

In our introduction, we posed this question with regards to druggability: ‘for which kinases can I make a high-quality inhibitor, so that I may test a target-based hypothesis?' We firmly believe that a high-quality inhibitor can be developed for any kinase, with selectivity being a crucial criterion for inhibitor quality. When a hit compound is available for a kinase from any of the kinase assays, optimizing the inhibitor scaffold's selectivity becomes paramount in the medicinal chemistry program to develop a suitable chemical tool for interrogating the target's biological properties. Targeting kinases from medicinal chemistry or chemical biology perspectives poses several challenges, with the conserved amino acids of the ATP-binding pocket presenting the most significant obstacle. Fortunately, the wealth of crystal structures demonstrates that active sites are similar, but they are not identical! These differences provide opportunities for selectivity. In this section we briefly provide an overview of the diversity of strategies that have been implemented to impart selectivity. The task of developing tools for every kinase, though challenging, becomes feasible with the presence of numerous examples of selectivity (e.g. the chemical probes list) and the emergence of applicable general strategies. With an understanding of how to design selective inhibitors, we firmly believe that the medicinal chemistry community has the potential to make every kinase druggable with a selective inhibitor.

Before highlighting some selectivity strategies, an understanding of two of the most common kinase inhibition modes would be helpful (Box 2). Great reviews are available for a deeper look [15,82,125–130].

| Box 2: Brief Overview of Type I and Type II Kinase Inhibition Modes |

|---|

| The hinge region of kinases is a stretch of amino acids that connects the two lobes of the kinase and plays a key role in interactions with numerous kinase inhibitors. Between the lobes connected by the hinge region is the deep cleft. At the hinge region, most ATP-competitive inhibitors make one, two, or even three hydrogen bonds with the kinase, recapitulating some of the H-bonds seen in the binding of ATP. This portion of the kinase is the target for both Type I and Type II kinase inhibitors, which bind to the amide backbone of the hinge region sequences. Typically, a Type I inhibitor will occupy this region, utilizing a core scaffold such as a pyrimidine, quinazoline, or azaindole to mimic and compete with ATP for the hydrogen bonding interactions at the hinge site [79]. Eight examples of FDA approved kinase inhibitors with different hinge binding groups are shown in Figure 11, with the yellow boxes highlighting the portion of the molecule that interacts with the hinge region via hydrogen bonds. The differentiating feature of Type I and Type II kinase inhibition is the state of the kinase to which the inhibitor binds, defined by the orientation of the DFG motif, a highly conserved and flexible tri-peptide motif which co-ordinates the binding of ATP in the catalytic domain. Type I inhibitors bind to the active state of kinases, with the Asp of the DFG motif positioned in the ATP-binding pocket while the Phe of the DFG motif remains in the back pocket of the kinase to complete the regulatory spine. Type II inhibitors bind to the inactive state of kinases. Here the Phe of the DFG motif flips into the ATP-binding pocket to preclude binding of ATP, while the Asp of the DFG motif flips into the back pocket of the kinase. When the Type II binding mode was first discovered, initial studies suggested Type II inhibitors tend to be more selective because they bind to the back pocket of the kinase, which tend to be less conserved [131–133]. However, additional research has found that Type II inhibitors are not necessarily more selective than Type I inhibitors [134–136]. |

Figure 11. Selected FDA approved kinase inhibitors with hinge-binding functionality highlighted with a yellow box.

Selectivity at the ATP-binding pocket

Even with the challenge posed by the highly conserved nature of kinase catalytic domains, the discovery of chemical probes has demonstrated that the development of selective Type I inhibitors is still a possibility. Despite a generally high degree of conservation of the amino acid residues surrounding the ATP-binding pocket, small single amino acid differences may be exploited to achieve selectivity between kinases through rational drug design. Some examples follow.

One residue where differences are commonly exploited is the gatekeeper residue [137–139], which is the residue which blocks access to the hydrophobic back pocket of kinases and is a key feature of the recognition elements in the ATP-binding site of the kinase [137,140,141]. The four most common gatekeeper residues in human kinases are Met, Thr, Phe, and Leu [136]. A smaller gatekeeper residue allows for access to back pocket [139], but it is possible to achieve Type II inhibition even with a large gatekeeper residue [135]. A smaller gatekeeper residue (Thr) also allows for binding at the region of the gatekeeper [142], although it has also been shown that the large but flexible side chain of Met can fold to accommodate inhibitors at this region as well [143]. Direct interaction with the different gatekeeper residues can also help to achieve selectivity between kinases. For example, addition of a halogen onto a pyrimidine scaffold can form a chalcogen bond between the halogen and the sulfur of the Met gatekeeper residue of JNK3, thereby achieving selectivity for JNK3 over p38α, which has a Thr as its gatekeeper (Figure 12) [144]. As another example of achieving selectivity at the gatekeeper residue, an inhibitor with a chlorine atom near the gatekeeper was tolerated by the smaller Leu gatekeeper residue of GSK3β but induces a steric clash with a larger Phe gatekeeper residue of CDK1/2, conferring selectivity for GSK3β [145]. In another example, selectivity for CDK2 over GSK3B has been achieved through the addition of a dimethyl because CDK2 has a wider pocket then that of GSK3B by virtue of differences in a few active site residues, including the gatekeeper [146]. The gatekeeper residue has also been a key residue in uncovering kinase biology via chemical genetics approaches. Mutation of a larger gatekeeper residue to a smaller residue sensitizes the mutant kinase to inhibitors that would otherwise sterically clash with the larger residue, allowing phenotypic effect of the inhibitor to be attributed to the kinase in question [147]. On the other hand, mutation of a small gatekeeper residue to a larger residue confers resistance towards its inhibitor. Knockout of the wild-type kinase and replacement with this mutant kinase thus serves as a control experiment to attribute the phenotypic effect of an inhibitor to inhibition of the kinase in question [148].

Figure 12. Examples of generated selectivity by addressing the gatekeeper residue.

Key selectivity-generating substitutions are highlighted in yellow.

Another residue that can be exploited for selectivity is the middle hinge residue, which does not form any hydrogen bonds with inhibitors via its amide backbone and has its side chain pointed towards the N-terminal lobe of the kinase. The three most common middle hinge residues are Tyr, Leu, and Phe [136]. The presence of the relatively smaller Leu residue here creates a small groove where small groups of the inhibitor may bind, thereby achieving selectivity over kinases with the larger Tyr and Phe residues. Lorlatinib exemplifies this by utilizing a nitrile group at this position, which was tolerated by ALK containing a leucine in this position but disfavored by NTRK2 (also called TRKB) which has the larger tyrosine in this position (Figure 13) [149]. A similar strategy was adopted where a methyl group of GDC-0994 helps to achieve selectivity for ERK2 (Leu) over CDK2 (Phe) [150]. The methoxy group of BI-2536 also serves a similar role in achieving selectivity for the kinase PLK1 (Leu) [151]. Additionally, interaction with the phenolic –OH of the tyrosine residue offers another alternative to achieve selectivity, as demonstrated by the selectivity obtained for CDK12 (Tyr) over the closely related family members CDK1/2/7/9 (Phe). Selectivity was achieved by using a benzimidazole that could form a hydrogen bond with the tyrosine residue of CDK12 [152].

Figure 13. Modulating selectivity by addressing the middle hinge residue.

For Lorlatinib, Ravoxertinib, and BI-2536 selectivity is gained because the group highlighted in yellow clashes for kinases with a Tyr or Phe residue here. In the case of the CDK12 inhibitor, the highlighted nitrogen of the benzimidazole makes a hydrogen bond with the Tyr-OH, improving potency and thus enhancing selectivity.

Other residues in the hinge region can also be exploited for selectivity. One example comes from the PIM family of kinases within the CAMK group. All three isoforms of the PIM kinases have a proline as the outer hinge residue. In all other kinases, this residue is responsible for providing the key backbone amide –NH as a hydrogen bond donor for inhibitor binding [136]. However, with a proline at this position of the PIM kinases, PIM inhibitors do not need the corresponding hydrogen bond acceptor typically found in other Type I and Type II inhibitors that serve as key the recognition element in the ATP-binding site. This allows for the design of exquisitely selective orthosteric inhibitors such as PIM-447 [153].

The hinge + 1 residue provides another avenue for selectivity. Only 46 kinases have a glycine at this position, which allows the backbone carbonyl of the outer hinge residue to rotate away from the ATP-binding site, instead presenting the backbone NH of the hinge + 1 residue into the binding site [136]. This ‘hinge-flip’ conformation thus presents two hydrogen bond donors, one from the backbone NH of the outer hinge residue and one from the NH of the hinge + 1 residue. This property has been exploited particularly in the design of p38α/MAPK14 inhibitors, which possess a carbonyl group at this position to form bifurcated hydrogen bonds with both hydrogen bond donors [154–157].

Moving further from the hinge towards solvent, there are other differences that can be exploited. In the outer hinge region, making specific and favorable interactions with the unique hinge + 4 and hinge + 6 residues have proven to be effective in the design of selective SYK inhibitors, targeting Pro455 and Asn457, respectively) [158].

Another common residue to address selectivity is the residue that directly precedes the DFG motif, often called the DFG-1 (DFG-minus-1) residue. This residue is not highly conserved, with 15% of all human kinases having a bulky hydrophobic residue (Val/Ile/Leu) at this position, while most other kinases have smaller or hydrophilic residues (Ala/Gly/Ser/Thr) [159]. Kinases with both a larger hydrophobic residue at the DFG-1 position and a hydrophobic gatekeeper (Phe/Leu/Ile) are able to adopt a binding mode where a hydrophobic or flat moiety of the inhibitor is sandwiched between the gatekeeper and the DFG-1 residue [159]. This confers selectivity of CLK inhibitors for CLK1/2/4 (Val) over the family member CLK3 (Ala) [159]. This example highlights the ability to take advantage of more than one difference (DFG-1 and gatekeeper) to build in selectivity. Because of the diversity of amino acid residues at the DFG-1 position, hydrogen bonding with Ser or Thr is also possible, as exemplified by LY333531 [160] and BI-4020 [161], conferring selectivity through this unique interaction. Where the DFG-1 residue is a glycine, the increased flexibility of the DFG loop allows for a helical conformation where both the Asp and Phe bend towards the back pocket of the kinase [162]. The ability to bind to this unique conformation has been used to explain selectivity of TAE226 for FAK. Targeting the DFG-1 residue provides another avenue to generate selective Type II inhibitors. In the Type II binding mode, this residue sits below the inhibitor as it binds to both the ATP-binding pocket and the back pocket. A smaller residue has been demonstrated to offer a larger binding pocket, allowing for selectivity of Type II inhibitors towards TNNI3K (Ala) over p38α (Leu) and VEGFR2 (Cys) [163]. The Ala residue in TNNI3K prevents the shift of the DFG Phe residue below the inhibitor, which was the case for B-RAF (Gly), allowing the inhibitor to achieve selectivity for TNNI3K [163].

The phosphate-binding loop (P-loop), also known as the Gly-rich loop, sits above the ATP-binding pocket and offers another avenue for selectivity. As an example of targeting small single amino acid differences, selectivity for PI3Kα over PI3Kβ was achieved by taking advantage of a hydrogen bonding interaction present between a sulfonamide oxygen of the inhibitor and an arginine residue on the Gly-rich loop in PI3Kα, which was not possible with the slightly shorter corresponding lysine residue in PI3Kβ [164]. In some kinases, the P-loop can adopt a folded conformation, where the fifth residue of the GxGxxG motif folds inwards towards the ATP-binding pocket. Interaction with this residue, typically a Phe or Tyr residue, may confer selectivity [134,165]. This has been demonstrated for ABL [166] and MAP4K4 [165]. When combined with an outward movement of the αC-helix, the folded P-loop opens a highly unusual binding pocket that may be further taken advantage of for selectivity, as has been shown for SCH772984 for ERK1/MAPK3 and ERK2/MAPK1 [167]. In another example where the highly dynamic P-loop conformation of kinases influences selectivity, our group reported the selectivity of the chemical probe SGC-STK17B-1 for DRAK2/STK17B over DRAK1/STK17A was derived from the flexibility of Arg41 in DRAK2 [158,164,168].

Selectivity by allosteric inhibition

Type III inhibitors are allosteric, and they modulate the activity of the kinase in a non-ATP-competitive manner. Four FDA approved MEK1/2 inhibitors (Binimetinib, Cobimetinib, Selumetinib, and Trametinib) serve to exemplify the selectivity of Type III inhibitors and illustrate the promise that they hold. These MEK1/2 inhibitors are highly selective for MEK by binding in the hydrophobic pocket adjacent to the ATP-binding site [83]. The MEK1/2 hydrophobic pocket is 100% conserved between these two kinases and has less than 70% sequence homology with other kinases. Additionally, MEK1/2 conserved Lys and Met residues physically separate the ATP-binding region from the adjacent hydrophobic pocket [169]. In structures of MEK1/2 co-crystallized concurrently with ATP or ATP-mimetic analogs and allosteric inhibitors, the kinase takes on a DFG-in, αC-helix-out conformation, where the conserved Glu residue on the αC-helix does not form an ion pair interaction with the catalytic Lys residue [170–172]. Molecular dynamics (MD) studies predicted that the specificity of the allosteric MEK inhibitors was attributed to the flexibility of the P-loop, activation loop and the αC-helix which allows for allosteric inhibitors to occupy the allosteric pocket [173].

Allosteric inhibition is not unique to the MEK kinases. GSK2982772 represents an unconventional Type III inhibitor of RIPK1 [174]. It binds to RIPK1 in a DFG-out conformation, occupying a deep lipophilic back pocket between the N and C-terminal domains and while making no interaction with the hinge residues, although it is not strictly considered allosteric as its benzoxapinone group occupies the space for the α-phosphate of ATP. Allosteric inhibitors have also been reported for LIMK2. The N-phenylsulfonamide series of allosteric inhibitors bind in the lipophilic back pocket of LIMK2 in a DFG-out conformation, without interaction with the hinge region. The non-competitive mode of inhibition was confirmed by enzyme kinetic studies [175]. Importantly, these compounds possess good selectivity over the related family member LIMK1, which shares a high degree of homology in the kinase domain [176,177]. This lends further evidence that allosteric inhibition may offer a route for the discovery of highly selective chemical tools for the study of kinases.

Understanding natural kinase regulatory mechanisms also provides an opportunity to develop selective allosteric inhibitors, as exemplified for BCR-ABL1. A myristoyl group occupies the myristate pocket of ABL1 under normal physiological conditions, preventing constitutive activation [178,179]. However, the formation of the BCR-ABL1 fusion protein leads to loss of the myristoyl-based autoregulation [180,181]. Allosteric inhibitors such as GNF-2 [182] and Asciminib [183,184] thus bind to this pocket to inhibit BCR-ABL1, mimicking the lost autoinhibitory function. One advantage of allosteric inhibitors, as highlighted by Asciminib, is the ability to overcome mutations in the ATP-binding pocket that confer resistance to ATP-competitive inhibitors [183]. Asciminib was approved by the FDA in 2021 and is an example of how informed SAR campaigns and a focus on allosteric inhibition can lead to discovery of a highly selective and efficacious inhibitor for a kinase [185].

The catalytic domain of a kinase is not the only means of drugging a kinase, as there are several extracatalytic domains which can be targeted as an alternative to the catalytic site and which are more variable [186]. Previous work has shown around 60% of the human kinome encodes for kinases with accessory domains, of which there are 65 varieties of accessory domains [187]. These numerous accessory domains open the potential for selectivity to be designed into a kinase inhibitor. Here we provide two small-molecule examples: SSR128129E binds to the extracellular domain of FGFR1 and FGFR2 selectively over other receptor TKs [188], and WRG-28 selectively binds to the extracellular domain of DDR2 over DDR1 [189].

Selectivity by protein degradation

An alternative class of probe has become available with the emergence of bifunctional degrader compounds called PROTACs (proteolysis targeting chimeras), which harness the cellular proteasomal degradation pathway to remove the bound target protein from the cell [190–195]. We highlight PROTACs here for two reasons. One, a kinase chemical probe could be a PROTAC reagent, and two, the PROTAC strategy may be implemented as another strategy by which selectivity between closely related kinases can be achieved. Many degrader probes have been made available by the Gray lab at Stanford University [75]. Amongst the 22 degrader probes from the Gray lab, there are 13 compounds available which target kinases. The thirteen unique compounds target ALK, AKT, BTK, CDK2/4/6/8/9/10/12, EGFR, and FGFR [196–206]. PROTAC degraders have been used in the past to increase selectivity of an already validated inhibitor for a kinase of interest.

A noteworthy example of PROTACs improving the selectivity for a kinase was shown by attaching a CEREBLON-binding thalidomide motif to AURKA kinase inhibitor alisertib [207]. Alisertib has a Kd of 7 nM for AurA and 90 nM for AURKB, a close relative in structural and functional aspects, offering a modest 13-fold selectivity window. When the novel degrader termed JB170 was evaluated using Kinobead selectivity profiling, the Kd value for AURKA was 99 nM while the Kd value for AURKB increased to 5.1 μM, increasing the selectivity window for AURKA to 52-fold.

The commercially available CDK4/6 kinase inhibitors Ribociclib, Palbociclib, and Abemaciclib are dual CDK4/6 inhibitors with similar reversible inhibitory activity for both CDK4 and CDK6. Several groups have investigated using these inhibitors in PROTAC reagents. The Burgess lab identified CDK4/6 degraders by linking Palbociclib and Ribociclib with Pomalidomide [208]. In other work, these three FDA approved CDK4/6 inhibitors were modified with either a PEG linker of varying length or an alkyl linker spanning from the piperazine of the inhibitor to the 4’ location of the E3 ligase Cereblon (CRBN) recruiter thalidomide to investigate if there would be any changes in fold selectivity by making these modifications. The results showed by adding an alkyl linked thalidomide to Ribociclib there was selective, CRBN dependent, degradation of CDK4. Similarly, by adding a PEG linker to Palbociclib selectivity for CDK6 was achievable [206]. This finding was further validated by another group which was able to achieve selective CDK6 degradation via addition of phthalidomide to Palbociclib [209]. Readers are referred to several comprehensive reviews of PROTAC based probes that discuss elements of constructing successful PROTAC reagents and the steps that need to be taken for validation of PROTAC probes [210–213].

Selectivity by covalent inhibition

Another potential way to improve the selectivity of kinase inhibitors for some kinases can be found in covalent inhibition [214,215]. Covalent inhibitors form covalent bonds with the target kinases [186]. Through residue specific reactivity and subsequent covalent bond formation, covalent kinase inhibitors may have enhanced selectivity. Just like the presence of different gatekeeper residues or different DFG-1 residues offer opportunities to design in selectivity, the location of nucleophilic residues on kinases (cysteines primarily, but also lysines, tyrosines, histidines, serines, and threonines) can be used to improve selectivity by incorporation of an appropriately placed electrophilic warhead on the kinase inhibitor.