Abstract

Background and Objectives

Neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders have long been considered as different clinical and molecular entities, and only a few genes are known to be involved in both processes. The IRF2BPL (interferon regulatory factor 2 binding protein like) gene was implicated in a severe pediatric phenotype characterized by developmental and epileptic encephalopathy and early regression. In parallel, inherited IRF2BPL variants have been reported in cohorts of patients with late-onset progressive dystonic and ataxic syndrome with few information about the neurodevelopment of these patients. This study aimed to describe both neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative aspects of the phenotype in adults with IRF2BPL pathogenic variant.

Methods

We report here the clinical and molecular data of 18 individuals carrying truncating IRF2BPL variants (identified by either exome or genome sequencing), including a large pedigree of 16 patients presenting with a neurodevelopmental disorder (NDD) associated with late-onset cerebellar ataxia and atrophy.

Results

Genome sequencing identified the p.(Gln117*) variant in a large family first assessed for familial ataxia, with multiple individuals presenting with NDD. The p.(Ser313*) variant was identified by exome sequencing in a second family with a young adult patient with NDD without ataxia which was inherited from her asymptomatic mother, suggesting incomplete penetrance of IRF2BPL-linked disorders.

Discussion

This study illustrates the importance of neurologic evaluation of adult patients initially diagnosed with NDD to detect a late-onset neurodegenerative condition. Two different disorders may be clinically diagnosed in the same family, when not considering that NDD and late cerebellar changes may be part of the same molecular spectrum such as for IRF2BPL.

Introduction

Neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs) are defined by impairments in cognition, communication, behavior, and/or motor skills resulting from abnormal brain development, manifesting either in utero or during early postnatal life. More than 1,000 genes have been implicated in NDD, mostly highly penetrant and evolutionarily constrained fetal brain-expressed genes.1,2 Neurodegenerative disorders are characterized by progressive neurodegeneration which results in progressive decline variably affecting cognition and behavior, motor and/or sensory functions, and presenting mostly in adulthood. The developmental and degenerative processes have long been considered as different clinical and biological entities. More recently, some common denominators and interactions between neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders have emerged suggesting that proteins implicated in neurodegenerative disorders play important roles in brain development. For example, pathogenic variants in the RAB39B and WDR45 genes are responsible for phenotypes characterized by early neurodevelopmental disorder with intellectual disability (ID) and secondary parkinsonism.3 Severe infantile onset developmental and epileptic encephalopathy are caused by mutations in the autophagy gene WDR45.4

We identified an IRF2BPL (interferon regulatory factor 2 binding protein like) variant segregating in a previously unreported large pedigree of 16 patients presenting with NDD associated with cerebellar ataxia which appeared later in life and in a sporadic case with NDD inherited from her asymptomatic mother.

Methods

Both families have been examined at the Pitié-Salpêtrière University Hospital 28 years apart.

Exome and Genome Sequencing

Two individuals (SAL-394-10 and 13) underwent genome sequencing on a HiSeq X Five (Illumina). Patient IIA had trio exome sequencing on a NextSeq 500 Sequencing System (Illumina, San Diego, CA), with a 2 × 150 bp high output sequencing kit after a 12-plex enrichment with the SeqCap EZ MedExome kit (Roche, Basel, Switzerland), according to the manufacturer's specifications.

For all patients, sequence quality was assessed with FastQC 0.11.5, then the reads were mapped using BWA-MEM (version 0.7.13), sorted and indexed in a bam file (samtools 1.4.1), duplicates were flagged (sambamba 0.6.6), and coverage was calculated (picard tools 2.10.10). Variant calling was performed with GATK 3.7 Haplotype Caller. Coverage for these samples was >96%, >89%, and >93% at a 20× depth threshold, for SAL-394-10, 13, and IIA patients, respectively. Variants were annotated with SnpEff 4.3, dbNSFP 2.9.3, gnomAD, ClinVar, HGMD, and OMIM. Filtering was performed with criteria based on the consequence on the protein and frequency in gnomAD.

All candidate variants and their segregation within pedigrees were further confirmed by Sanger sequencing. We used the NM_024496.3 transcript as the reference sequence.

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards in accordance with local French legislation (approval from local ethics committees on December 19, 1990 and November 10, 1992). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients and/or their legal representatives.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Results

Family SAL-394

This index case, SAL-394-013, experienced the onset of unsteady gait due to cerebellar ataxia at age 30 years and had a progressive worsening of her ability to walk making wheelchair use necessary at age 40 years (Figure 1). Reflexes were increased in all limbs with unilateral extensor plantar reflex and Hoffman signs, mild proximal weakness but no wasting. Both arms showed dystonic postures, and there was a mild loss of facial mimicry. Eye movements were abnormal because of the presence of gaze-evoked nystagmus and a limited upward gaze. She complained of swallowing difficulties but not of urinary problems. Cognitive impairment was clinically suspected. Cerebral MRI showed mild global cortical atrophy, moderate cerebellar atrophy with normal brainstem volume, and no white matter changes (Figure 2). Nerve conduction velocities were normal as was the muscle biopsy. Visual-evoked potentials showed normal optic nerve conduction time; auditory-evoked potentials were abnormal with delayed bulbar and brainstem latencies. Somatosensory-evoked potentials were evocative of abnormal bilateral thalamocortical connections and impaired bilateral lemniscus fibers. This was also reflected by decreased vibration detection at the ankles.

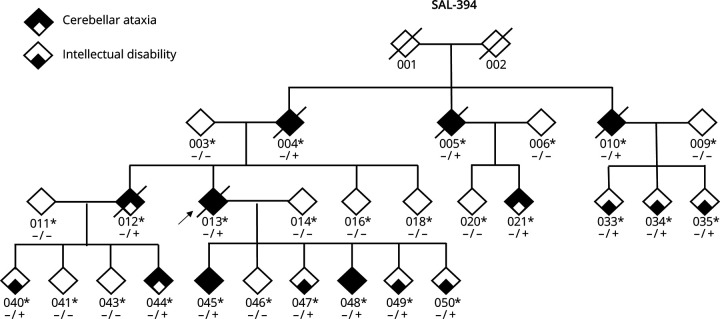

Figure 1. Family Structure of SAL-394.

Bold symbols indicate that individuals had cerebellar and pyramidal signs; small squares indicate intellectual disability only. Genotypes are indicated; heterozygous carriers are +/−. The arrow indicates the index case. Deceased individuals are crossed out.

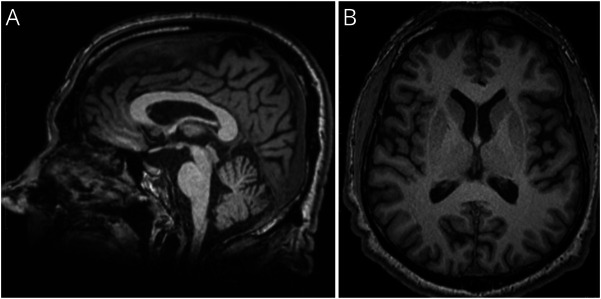

Figure 2. Cerebral MRI From SAL-394-048 After 10 Years of Ataxia Duration.

T1-weighted MPRAGE sagittal (A) and axial (B) views. Mild but visible cerebellar (vermian), mesencephalic and lower brainstem atrophy, as well as general cortical thinning.

Family history revealed several other affected members, and the family had been seen at their homes by AD and AB (see Table). Ages at examination ranged from 11 to 74 years. Ages at death ranged from 58 to 77 (n = 5) and ataxia durations from 21 up to 43 years. Patients presented with variable combinations of intellectual disability and/or a cerebellar ataxia with pyramidal signs. Half of the patients (8/16) had ataxic features with onset between ages 21 and 53 years. Seven individuals (021, 035, 040, 044, 045, 047, and 048) had very slight difficulties with sway in the upright position with feet together or in tandem walking or isolated mild dysarthria. These very slight signs were confirmed in 3 (040, 045, and 047) seen first in their twenties, with evident cerebellar ataxia in their thirties or even fifties, in addition to their mild intellectual difficulties since school. Reflexes were increased in most (11/16), while plantar reflexes were extensor in 5/16. ID was present in all individuals evaluated. Evaluations were not available for the oldest patients (004, 005, 010, 012, 013, and 040) who all had severe cerebellar signs and no speech for 3. Neurodevelopmental difficulties in most affected members were also noted without specificities. A clinical geneticist specialized in neurodevelopmental disorders (SH) contacted several members of the family to better delineate the neurodevelopmental trajectory of the affected members (psychomotor development, scholarship, and acquisition of writing and reading). No formal IQ scores were available for these patients, but it seems that all affected members presented with mild-to-moderate ID. This study indicates that all variant carriers examined after the age of 35 years had clinical signs of cerebellar ataxia and pyramidal signs. Those examined at a younger age had intellectual difficulties, and several already had increased reflexes (4/9) and/or minimal cerebellar signs. We could not reach 4 patients from the initial family.

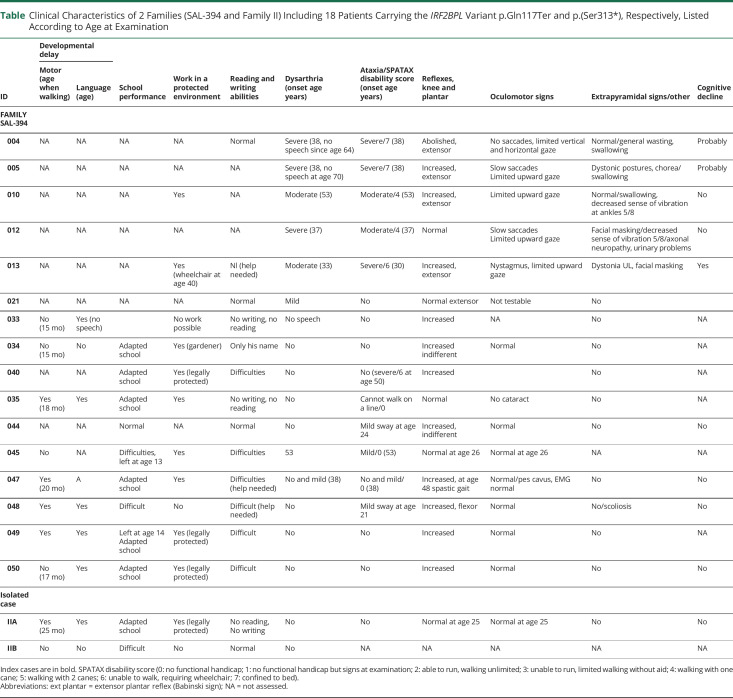

Table.

Clinical Characteristics of 2 Families (SAL-394 and Family II) Including 18 Patients Carrying the IRF2BPL Variant p.Gln117Ter and p.(Ser313*), Respectively, Listed According to Age at Examination

| ID | Developmental delay | School performance | Work in a protected environment | Reading and writing abilities | Dysarthria (onset age years) | Ataxia/SPATAX disability score (onset age years) | Reflexes, knee and plantar | Oculomotor signs | Extrapyramidal signs/other | Cognitive decline | |

| Motor (age when walking) | Language (age) | ||||||||||

| FAMILY SAL-394 | |||||||||||

| 004 | NA | NA | NA | NA | Normal | Severe (38, no speech since age 64) | Severe/7 (38) | Abolished, extensor | No saccades, limited vertical and horizontal gaze | Normal/general wasting, swallowing | Probably |

| 005 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Severe (38, no speech at age 70) | Severe/7 (38) | Increased, extensor | Slow saccades Limited upward gaze |

Dystonic postures, chorea/swallowing | Probably |

| 010 | NA | NA | NA | Yes | NA | Moderate (53) | Moderate/4 (53) | Increased, extensor | Limited upward gaze | Normal/swallowing, decreased sense of vibration at ankles 5/8 | No |

| 012 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Severe (37) | Moderate/4 (37) | Normal | Slow saccades Limited upward gaze |

Facial masking/decreased sense of vibration 5/8/axonal neuropathy, urinary problems | No |

| 013 | NA | NA | NA | Yes (wheelchair at age 40) | Nl (help needed) | Moderate (33) | Severe/6 (30) | Increased, extensor | Nystagmus, limited upward gaze | Dystonia UL, facial masking | Yes |

| 021 | NA | NA | NA | NA | Normal | Mild | No | Normal extensor | Not testable | No | |

| 033 | No (15 mo) | Yes (no speech) | No work possible | No writing, no reading | No speech | No | Increased | NA | No | NA | |

| 034 | No (15 mo) | No | Adapted school | Yes (gardener) | Only his name | No | No | Increased indifferent | Normal | No | NA |

| 040 | NA | NA | Adapted school | Yes (legally protected) | Difficulties | No | No (severe/6 at age 50) | Increased | No | NA | |

| 035 | Yes (18 mo) | Yes | Adapted school | Yes | No writing, no reading | No | Cannot walk on a line/0 | Normal | No cataract | No | NA |

| 044 | NA | NA | Normal | NA | Normal | No | Mild sway at age 24 | Increased, indifferent | Normal | No | No |

| 045 | No | NA | Difficulties, left at age 13 | Yes | Difficulties | 53 | Mild/0 (53) | Normal at age 26 | Normal at age 26 | NA | NA |

| 047 | Yes (20 mo) | A | Adapted school | Yes | Difficulties (help needed) | No and mild (38) | No and mild/0 (38) | Increased, at age 48 spastic gait | Normal/pes cavus, EMG normal | No | No |

| 048 | Yes | Yes | Difficult | No | Difficult (help needed) | No | Mild sway at age 21 | Increased, flexor | Normal | No/scoliosis | No |

| 049 | Yes | Yes | Left at age 14 Adapted school |

Yes (legally protected) | Difficult | No | No | Increased | Normal | No | NA |

| 050 | No (17 mo) | Yes | Adapted school | Yes (legally protected) | Difficult | No | No | Increased | Normal | No | No |

| Isolated case | |||||||||||

| IIA | Yes (25 mo) | Yes | Adapted school | Yes (legally protected) | No reading, No writing | No | No | Normal at age 25 | Normal at age 25 | No | No |

| IIB | No | No | Difficult | No | Normal | No | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Index cases are in bold. SPATAX disability score (0: no functional handicap; 1: no functional handicap but signs at examination; 2: able to run, walking unlimited; 3: unable to run, limited walking without aid; 4: walking with one cane; 5: walking with 2 canes; 6: unable to walk, requiring wheelchair; 7: confined to bed).

Abbreviations: ext plantar = extensor plantar reflex (Babinski sign); NA = not assessed.

Family II

Patient IIA was the third child of nonconsanguineous healthy parents. She was born eutrophic at term after an uneventful pregnancy. Her first months of life were normal. She presented with a global developmental delay with unsupported sitting acquired after age 9 months, independent walking acquired at 25 months, and a language delay with first words emerging around 4 years. She went to a special school from the age of 8 because of learning difficulties and had speech and psychomotor therapies during childhood. She had no history of epilepsy. At the last evaluation at the age of 25 years, she had moderate intellectual disability, was not able to read or write, and was under curatorship. Her neurologic examination was normal. She had moderate obesity (body mass index 30.9) without compulsive eating behavior. Her brain MRI was normal.

Genetic Analyses

In family SAL-394, previous screening of the repeat expansions in ATXN1, 2, and 3; CACNA1A; ATXN7; ATXN10; PPP2R2B; TBP; and ATN1 was negative as was a search for point mutations by targeted sequencing in most known ataxia-related genes. Genome sequencing in 2 individuals later identified variant c.349C>T, p(Gln117*) in a polymorphic CAG repeat region of the IRF2BPL gene absent from the GnomAD database (v2.1.1 and v3.1.2) and segregating in all affected (either with DI and/or ataxia) individuals.

In family II, exome sequencing identified the IRF2BPL variant c.938C>A, p.(Ser313*), absent from the GnomAD database (v2.1.1 and v3.1.2), and inherited from the healthy mother who had no evidence of mosaicism (variant allelic frequency = 0.45). The mother reported no developmental delay and went to a normal school until the age of 14 years but did not work. She was autonomous as an adult. She died of a domestic accident at the age of 45 years. No neurologic abnormalities were reported. A segregation study in family II showed that the healthy sister of the patient did not carry the IRF2BPL variant.

Discussion

We are reporting on 2 families carrying pathogenic IRF2BPL truncating variants, one large family with 27 sampled individuals including 16 patients and a second family with a mother-child dyad. Of interest, affected members in the large family exhibited 2 phenotypes, not believed to be related at first: intellectual disability and late-onset cerebellar ataxia with pyramidal signs. This prevented us from identifying a common cause through genome sequencing because the phenotypes were treated as 2 different traits. The large family was seen 28 years ago, and thus, we contacted members of the younger generation to gather information about their outcomes. Three individuals seen in their twenties developed cerebellar signs in their thirties and fifties. This was in addition to mild intellectual difficulties present since beginning school linked to the full phenotype of IRF2BPL in adults. This shows that variants in IRF2BPL are responsible for both a neurodevelopmental and a neurodegenerative aspect of the disease. The IRF2BPL gene encodes for an E3 ubiquitin protein ligase involved in the proteasome-mediated ubiquitin-dependent degradation of target proteins and is ubiquitously expressed in human tissues, including the brain. This protein plays a role in the development of the CNS and in neuronal maintenance through Wnt (Wingless/integrated) signaling. The Wnt family of ligand glycoproteins acts as key regulators of the development especially in the CNS by regulating cell proliferation, migration, differentiation, and synapse development.5,6

Heterozygous loss of function variants in the IRF2BPL gene had first been reported in individuals with a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by initial normal or subnormal development and early neurologic regression with epilepsy prior to the age of 7 in most patients.7,8 Neurologic features include severe tetraparesis and cerebellar syndrome with ataxia, dysarthria, and nystagmus, associated with inconstant cerebellar atrophy. Some patients did not show signs of neurologic regression and instead presented with global mild to moderate developmental delay. In these pediatric patients, the reported IRF2BPL variants arose de novo. In parallel, IRF2BPL variants have been identified in patients with adult-onset dystonia in 2 out of 8 NDD patients with cerebellar ataxia and pyramidal signs as well as dystonic features.9-11 One of the first descriptions of a link between neurodegenerative and neurodevelopmental disorders was for Rett syndrome, characterized by motor degradation and attributed to a disturbance of BDNF transport throughout the corticostriatal pathway.12

Similarly, pathogenic variants in the WDR45 or RAB39B genes have been reported to induce learning difficulties and ID with progression towards a neurodegenerative parkinsonism phenotype in adulthood.3,4

In this study, patient IIA inherited the IRF2BPL variant from her asymptomatic mother who died in an accident at age 45, suggesting incomplete penetrance. At the last evaluation after identification of the IRF2BPL variant, patient IIA presented no neurologic signs, too young at the time.

Neurodegenerative aspects in NDD are very likely underestimated as young adult patients with NDD are often lost to specialized follow-up. This study illustrates the importance of regular evaluation of patients with NDD during adulthood to better delineate the natural history of the disease. Understanding the relationships between nervous system development and degeneration is essential for early detection and prevention of neurodegenerative disease. Looking at premanifest phases of dominantly inherited diseases has allowed us to show neurodevelopment changes in Huntington disease.13 Human fetal tissues which carried an expansion in the HTT gene responsible for late-onset disease showed abnormalities in the developing cortex, including abnormal localization of mutant huntingtin and junction complex proteins, defects in polarity and differentiation of neural precursors, abnormal ciliogenesis, and changes in mitosis and cell cycle progression. These abnormalities disrupt the “division-differentiation” balance of progenitors. This work not only provides the first direct evidence from human fetuses that brain development is impaired in a neurodegenerative disease with delayed onset but also clearly demonstrate that molecular changes even in adult-onset neurologic diseases occur very early on. These early changes may prime specific neuronal populations for neurodegeneration occurring much later.

Acknowledgment

The authors are deeply indebted to all family members for their patience and participation. Special thanks to Bertrand Fontaine, Fausto Viader, and Soraya Medjbeur for referral and initial neurologic examination.

Glossary

- ID

intellectual disability

- NDD

neurodevelopmental disorder

Appendix. Authors

| Name | Location | Contribution |

| Solveig Heide, MD | Genetic Department, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris (AP-HP) Pitié-Salpêtrière; Reference Center for Rare Diseases « Intellectual disabilites of rare causes » « Déficiences Intellectuelles de Causes Rares », Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital, Paris, France | Conception and design of the study; acquisition and analysis of data; drafting a significant portion of the manuscript or figures |

| Claire-Sophie Davoine, BS | Sorbonne Université, Paris Brain Institute (ICM Institut du Cerveau), INSERM, CNRS, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris (AP-HP), France | Conception and design of the study; acquisition and analysis of data; drafting a significant portion of the manuscript or figures |

| Paulina Cunha, MD | Sorbonne Université, Paris Brain Institute (ICM Institut du Cerveau), INSERM, CNRS, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris (AP-HP), France | Acquisition and analysis of data |

| Clarisse Scherer-Gagou, MD | Department of Neurology, University Hospital d’Angers, France | Acquisition and analysis of data |

| Boris Keren, MD, PhD | Genetic Department, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris (AP-HP) Pitié-Salpêtrière, France | Acquisition and analysis of data |

| Giovanni Stevanin, PhD | Sorbonne Université, Paris Brain Institute (ICM Institut du Cerveau), INSERM, CNRS, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris (AP-HP); INCIA, EPHE, Université de Bordeaux, France | Drafting a significant portion of the manuscript or figures |

| Perrine Charles, MD, PhD | Genetic Department, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris (AP-HP) Pitié-Salpêtrière; Reference Center for Rare Diseases « Intellectual disabilites of rare causes » « Déficiences Intellectuelles de Causes Rares », Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital, Paris, France | Drafting a significant portion of the manuscript or figures |

| Delphine Heron, MD | Genetic Department, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris (AP-HP) Pitié-Salpêtrière; Reference Center for Rare Diseases « Intellectual disabilites of rare causes » « Déficiences Intellectuelles de Causes Rares », Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital, Paris, France | Acquisition and analysis of data |

| Alexis Brice, MD, PhD | Sorbonne Université, Paris Brain Institute (ICM Institut du Cerveau), INSERM, CNRS, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris (AP-HP), France | Conception and design of the study; acquisition and analysis of data; drafting a significant portion of the manuscript or figures |

| Alexandra Durr, MD, PhD | Genetic Department, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris (AP-HP) Pitié-Salpêtrière; Sorbonne Université, Paris Brain Institute (ICM Institut du Cerveau), INSERM, CNRS, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris (AP-HP), France | Conception and design of the study; acquisition and analysis of data; drafting a significant portion of the manuscript or figures |

Study Funding

The authors report no targeted funding.

Disclosure

The authors report no relevant disclosures. Go to Neurology.org/NG for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Hoischen A, Krumm N, Eichler EE. Prioritization of neurodevelopmental disease genes by discovery of new mutations. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17(6):764-772. doi: 10.1038/nn.3703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Samocha KE, Robinson EB, Sanders SJ, et al. A framework for the interpretation of de novo mutation in human disease. Nat Genet. 2014;46(9):944-950. doi: 10.1038/ng.3050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson GR, Sim JCH, McLean C, et al. Mutations in RAB39B cause X-linked intellectual disability and early-onset Parkinson disease with α-synuclein pathology. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;95(6):729-735. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.10.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carvill GL, Liu A, Mandelstam S, et al. Severe infantile onset developmental and epileptic encephalopathy caused by mutations in autophagy gene WDR45. Epilepsia. 2018;59(1):e5-e13. doi: 10.1111/epi.13957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marcogliese PC, Dutta D, Ray SS, et al. Loss of IRF2BPL impairs neuronal maintenance through excess Wnt signaling. Sci Adv. 2022;8(3):eabl5613. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abl5613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Higashimori A, Dong Y, Zhang Y, et al. Forkhead box F2 suppresses gastric cancer through a novel FOXF2-IRF2BPL- β -Catenin signaling axis. Cancer Res. 2018;78(7):1643-1656. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-17-2403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tran Mau-Them F, Guibaud L, Duplomb L, et al. De novo truncating variants in the intronless IRF2BPL are responsible for developmental epileptic encephalopathy. Genet Med. 2019;21(4):1008-1014. doi: 10.1038/s41436-018-0143-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marcogliese PC, Shashi V, Spillmann RC, et al. IRF2BPL is associated with neurological phenotypes. Am J Hum Genet. 2018;103(3):456-460. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antonelli F, Grieco G, Cavallieri F, Casella A, Valente EM. Adult onset familiar dystonia-plus syndrome: a novel presentation of IRF2BPL-associated neurodegeneration. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2022;94:22-24. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2021.10.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ganos C, Zittel S, Hidding U, Funke C, Biskup S, Bhatia KP. IRF2BPL mutations cause autosomal dominant dystonia with anarthria, slow saccades and seizures. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2019;68:57-59. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2019.09.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prilop L, Buchert R, Woerz S, Gerloff C, Haack TB, Zittel S. IRF2BPL mutation causes nigrostriatal degeneration presenting with dystonia, spasticity and keratoconus. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2020;79:141-143. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2020.03.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pejhan S, Rastegar M. Role of DNA Methyl-CpG-binding protein MeCP2 in Rett syndrome pathobiology and mechanism of disease. Biomolecules. 2021;11(1):75. doi: 10.3390/biom11010075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barnat M, Capizzi M, Aparicio E, et al. Huntington's disease alters human neurodevelopment. Science. 2020;369(6505):787-793. doi: 10.1126/science.aax3338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.