Abstract

Bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) is a global staple crop vital for human nutrition. Heading date (HD) and flowering date (FD) are critical traits influencing wheat growth, development, and adaptability to diverse environmental conditions. A comprehensive study were conducted involving 190 bread wheat accessions to unravel the genetic basis of HD and FD using high-throughput genotyping and multi-environment field trials. Seven independent quantitative trait loci (QTLs) were identified to be significantly associated with HD and FD using two GWAS methods, which explained a proportion of phenotypic variance ranging from 1.43% to 9.58%. Notably, QTLs overlapping with known vernalization genes Vrn-D1 were found, validating their roles in regulating flowering time. Moreover, novel QTLs on chromosome 2A, 5B, 5D, and 7B associated with HD and FD were identified. The effects of these QTLs on HD and FD were confirmed in an additional set of 74 accessions across different environments. An increase in the frequency of alleles associated with early flowering in cultivars released in recent years was also observed, suggesting the influence of molecular breeding strategies. In summary, this study enhances the understanding of the genetic regulation of HD and FD in bread wheat, offering valuable insights into crop improvement for enhanced adaptability and productivity under changing climatic conditions. These identified QTLs and associated markers have the potential to improve wheat breeding programs in developing climate-resilient varieties to ensure food security.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11032-023-01422-z.

Keywords: GWAS, Bread Wheat, Heading Date, Flowering Date, Candidate Gene

Introduction

Bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) is the most widely grown crop in the world with massive importance for human nutrition (Mitchell et al. 2007). Heading date (HD) and flowering date (FD) significantly impact the growth and development of wheat, making them critical traits for determining cultivar adaptability to varied climatic conditions in different regions and cropping seasons (Law and Worland 1997).

The heading period of wheat is not only closely associated with its growth period but also significantly influences various vital agronomic traits, including yield, disease resistance, and stress tolerance (Jia et al. 2013). An appropriate heading period can ensure high and stable wheat yields (Abboye et al. 2020). The flowering stage is also closely linked to maturity, influencing multiple yield-related traits, thus ultimately affecting overall yield. Moreover, the flowering period represents the wheat's most critical phase of water sensitivity, signifying the transition from vegetative to reproductive growth, and thus is pivotal for determining wheat yield.

Plant HD and FD are regulated by five major pathways, age, vernalization, photoperiod, phytohormone gibberellic acid (GA), and autonomous (Distelfeld et al. 2009; Amasino and Michaels 2010; Capovilla et al. 2015). Among the various pathways, vernalization and photoperiod are recognized as the primary determinants of HD and FD in wheat (Choi et al. 2011; Kamran et al. 2014; Kosová et al. 2008; Li et al. 2020; Song et al. 2013; Zhang et al. 2015). Thus far, the growth habits and vernalization requirements of cereal plants have been primarily attributed to four genes of Vrn-1, Vrn-2, Vrn-3, Vrn-D4. Vrn-1, Vrn-3, and Vrn-D4 are considered flowering-promoting factors, while Vrn-2 functions as a flowering inhibitor (Kippes et al. 2015; Yan et al. 2003, 2004, 2006). Photoperiod insensitivity is widespread in wheat varieties worldwide and predominates in areas where spring wheat is grown in summer and winter wheat in autumn needs to mature in the following year before the onset of high summer temperatures (Zhang et al. 2015). Light plays a crucial role in regulating the transition from seed germination to flowering (Huo et al. 2016). In common wheat, the photoperiod response is regulated by photoperiod genes Ppd-1, located on chromosomes 2A, 2B, and 2D, assigned as Ppd-A1, Ppd-B1, and Ppd-D1, respectively (Boden et al. 2015; Mohler et al. 2004; Wilhelm et al. 2013). Alleles Ppd-A1a, Ppd-B1a, and Ppd-D1a confer photoperiod insensitivity, whereas Ppd-A1b, Ppd-B1b, and Ppd-D1b are sensitive to photoperiod (Dyck et al. 2004). Photoperiod insensitivity is consistently advantageous for yield and adaptability in regions such as Southern Europe and Asia (Cho et al. 2015; Seki et al. 2011; Shcherban et al. 2015). The increased expression of Ppd-A1a and Ppd-D1a is attributed to deletions in the promoter region, while elevated expression of Ppd-B1a is due to an increased copy number variation (CNV) (Kiseleva et al. 2017). The Ppd-D1a allele accelerates the growth process of winter wheat and enables early heading and flowering under both long- and short-day conditions, allowing it to evade unfavorable environmental conditions in the later stages (Harris et al. 2017; Okada et al. 2019; Shimada et al. 2009).

The photoperiod-insensitive allele Ppd-D1a became prevalent in the winter wheat region of China due to selective breeding. Shcherban et al. (2015) analyzed the genotypic composition of vernalization and photoperiod loci among European wheat cultivars, revealing that Ppd-D1a was predominantly found in southern Europe, whereas the photoperiod-sensitive allele Ppd-D1b was present in 91% of spring wheat cultivated in the northern European spring wheat region. Typically, the photoperiod-sensitive Ppd-D1b allele is primarily found in spring wheat regions of higher latitude due to the moderate summer temperatures that do not prohibit the later growth phase of wheat (Andeden et al. 2011; Guo et al. 2010; Yang et al. 2009). Apart from influencing the growth period, the Ppd-D1 allele also impacts various agronomic traits, including plant height and leaf shape. Previous studies have demonstrated the close association of the Ppd-D1 gene with other significant agronomic genes in 2D, including the Rht8 gene, a dwarf gene responsive to GA (Chai et al. 2022; Ellis et al. 2007; Worland et al. 2001; Würschum et al. 2018). They also revealed that both Rht8 and Ppd-D1a contribute to reduced plant height and earlier heading, and increase grain yield through augmentation of the number of fertile spikelets (Zhang et al. 2019). In addition, their combined effects are substantially larger than those conferred by either allele alone. Hence, the characterization of heading and flowering dates and the identification of novel heading date regulatory genes hold immense significance in deciphering the mechanisms that regulate wheat's heading and flowering dates.

HD and FD are complex polygenic traits, with several major genes previously identified (Kippes et al. 2015; Yan et al. 2003, 2004, 2006). Nonetheless, variations in HD and FD persist among materials with the same genotypes at the known loci, suggesting the presence of undiscovered quantitative trait loci (QTLs). Genome-wide Association Study (GWAS) approach enables systematic analysis of the genetic architecture underlying complex plant traits.

The present study aimed to reveal the important genetic loci for HD and FD using the 660 K SNP array in a diverse panel of 190 bread wheat accessions surveyed using a combination of HB-GWAS and SNP-based GWAS, linkage analysis, and polymorphism identification. The primary aim of this study was to identify the novel loci and candidate genes that are significantly associated with HD and FD in bread wheat.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

A total of 190 bread wheat accessions were included in this study, composed of 182 current wheat accessions and advanced lines from the major wheat production regions of China, predominantly from the Huang-huai winter wheat region, and 8 introduced varieties (Supplementary Table S1). These accessions were planted at the farm of the Institute of water-saving Agriculture in Arid Areas of China, located at Northwest A&F University (N34.3°; E108.8°), during the 2020–2021 and 2021–2022 cropping seasons. Furthermore, a total of 74 natural population accessions were also planted under the same conditions during the 2021–2022 cropping season.

These accessions were sown in the field as the normal watering (NW) treatment and under rainout shelters for drought treatment (DT). The rain shelters were closed to prevent rain after the heading stage. The field trial followed a completely randomized design based on random number generators or randomization tables. Each plot consisted of six 2-m-long rows with a spacing of 25 cm between rows and 3.33 cm between individuals. The HD and FD were recorded for each cultivar when approximately half of the plants displayed fully visible ears and stamens in April–May 2021, and 2022.

Allelic variations in vernalization and photoperiod genes

Genomic DNA was extracted from young leaves of 15-day-old seedlings using the cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) protocol (Aldrich and Cullis 1993). The PCR and programs were performed following the methods described in Chumanova et al. (2020) and Zhang et al. (2008). The PCR products were then separated on 1.5–2.5% agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide, and visualized using Image Lab. Allelic variations in vernalization and photoperiod response genes were identified in all surveyed cultivars based on the method outlined by Zhang et al. (2015).

Genotype filtering, population structure, and LD of the association panel

Genomic DNA was isolated using the CTAB method and subsequently genotyped with the 660K wheat iSelect SNP array by Capital Bio-limited (Beijing, China), following the standard procedure outlined by Sun et al. (2020). SNP calls were then filtered to include only those with missing values ≤ 10% and minor allele frequency (MAF) ≥ 5%. After filtering, a total of 273,329 SNPs were retained for GWAS among the 190 wheat materials. The population structure was assessed using ADMIXTURE-1.3.0 with all markers (Zhou et al. 2011), and genetic clusters were determined based on the lowest CV error value. The population structure diagram was created using Pophelper (http://pophelper.com/). The decay rate of linkage disequilibrium (LD) was calculated as the physical distance at which the average pairwise r2 dropped to half of its maximum value (Huang et al. 2010).

Genome-wide association study

Two GWAS methods were employed in this study. The first was the standard SNP-based GWAS (SNP-GWAS) approach, implemented using the linear mixed model in the “GAPIT3” packages (Wang and Zhang 2021) in the R 4.1.3 environment (R Core Team 2021). A uniform genome-wide significance threshold 10e−4 was set for this analysis. The second approach was the haplotype-based GWAS (HB-GWAS), utilizing the “RAINBOW” R package (Hamazaki and Iwata 2020). Plink1.9 was used to identify haplotype blocks as one set, considering a LD interval of no more than 500 kb for HB-GWAS. Within the LD region, the SNP or haplotype block with the highest -log10(p) value was considered representative for the values. To visualize the results of the GWAS analysis, Manhattan and quantile–quantile (Q–Q) plots were generated using the "CMplot" package (Yin et al. 2021) in R4.1.3 environment.

Identification of candidate genes in the haplotype block regions

The LD decay was calculated separately for the whole wheat genome and its different sub-genomes, setting at half of the maximum r2 value. If there was overlap between the candidate intervals of SNPs or haplotype blocks, they were merged into a single QTL. The corresponding gene IDs within the physical intervals of the identified QTLs were extracted from the IWGSC reference genome version 1.1 (The International Wheat Genome Sequencing Consortium [IWGSC] 2018). Additionally, the protein sequences of the corresponding candidate genes were obtained using the gene IDs, and the functional annotation of the proteins was performed using WheatOmics1.0, with the longest transcript used for annotation (Ma et al. 2021). Wheat genes that exhibited orthology to rice or Arabidopsis genes associated with heading and flowering dates were named accordingly. The expression level of candidate genes was retrieved from the Wheat Expression Browser (Ramírez-González et al. 2018), and a gene expression heatmap was generated using TBtools (Chen et al. 2020a, b).

Statistical analysis

The best linear unbiased estimator (BLUE) values of HD and FD under NW and DT conditions were determined using the "Lme4" package in R (Bates et al. 2014). The correlation coefficients and their significance between traits were calculated using the “PerformanceAnalytics” package in R4.1.3. Phenotype analysis and the Wilcoxon test were carried out to identify significant differences (* P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001) in HD and FD among the cultivars with various alleles using the R package "ggpubr" (https://github.com/kassambara/ggpubr/) and Microsoft Excel 2019 software.

Results

Phenotypic variation in HD and FD

The histogram depicting the HD and FD of the association mapping population (AMP) under NW, DT, and BLUE showed a nearly symmetrical distribution (Supplemental Fig. S1). The distribution spanned a range of 10–26 days, indicating significant variations in HD and FD among the accessions. Furthermore, the correlation coefficients between HD and FD were calculated among NW, DT, and BLUE, which ranging from 0.65*** to 0.86***, 0.51*** to 0.86***, and 0.93***, respectively (Supplemental Fig. S2). Within the same environment, the correlation coefficients between HD and FD ranged from 0.85 to 0.93*** (Supplemental Fig. S2). The broad-sense heritability (h2) values for HD and FD in the two years ranged from 68.93% to 84.12% (Table 1, Supplementary Table S1), indicating that HD and FD were influenced by the environment to varying degrees.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of HD and FD in NW and DT of the two growing seasons and BLUE values

| Traits_locale | Year/ BLUE | Mean | SD ( ±) | Range | CV | h2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HD_NW | 2020–2021 | 191.14 | 4.12 | 181 ~ 203 | 2.16% | 84.12% |

| 2021–2022 | 191.38 | 3.2 | 181 ~ 201 | 1.67% | ||

| BLUE | 183.06 | 2.45 | 177.6 ~ 193.4 | 1.34% | ||

| FD_NW | 2020–2021 | 202.4 | 3.37 | 192 ~ 211 | 1.67% | 76.67% |

| 2021–2022 | 200.34 | 3.14 | 189 ~ 211 | 1.57% | ||

| BLUE | 192.56 | 1.91 | 187.2 ~ 200.3 | 0.99% | ||

| HD_DT | 2020–2021 | 180.43 | 3.41 | 167 ~ 193 | 1.89% | 69.82% |

| 2021–2022 | 169.26 | 2.5 | 163 ~ 183 | 1.48% | ||

| BLUE | 183.06 | 2.45 | 177.6 ~ 193.4 | 1.34% | ||

| FD_DT | 2020–2021 | 190.07 | 2.82 | 184 ~ 200 | 1.48% | 68.93% |

| 2021–2022 | 177.46 | 2.13 | 169 ~ 189 | 1.20% | ||

| BLUE | 192.56 | 1.91 | 187.2 ~ 200.3 | 0.99% |

HD heading date; FD flowering date; BLUE best linear unbiased estimator; CV Coefficient of Variation

Distribution of Vrn-1 and Ppd-D1 genes and their effects on HD and FD

To elucidate the effects of allelic variations in vernalization and photoperiod genes on HD and FD in Chinese wheat accessions.Functional markers were used to screen the allelic variations in Vrn-A1, Vrn-B1, Vrn-D1 and Ppd-D1 genes among 182 wheat germplasms from six major wheat production regions. The results revealed that all 182 wheat materials carried vrn-A1, and 180 of them carried Ppd-D1a. Moreover, allelic variations were observed in the Vrn-B1 and Vrn-D1 genes among these materials (Table 2, Supplementary Table S1). The proportions of spring allelic variation in Vrn-1 differed across the five wheat production regions,which were 2.9%, 10.9%, 38.4%, 16.0% and 100% for Northern Winter Wheat Region (NWWR), Northern of Huang-huai Winter Wheat region (NHWWR), Southern of Huang-huai Winter Wheat Region (SHWWR), Western of Huang-huai Winter Wheat Region (WHWWR), and the Middle and Lower Yangtze Valley Winter wheat Region (MLYWWR), respectively (Table 2). Additionally, Ningchun 45 from the Northwest Spring wheat region (NWSWR) carried Vrn-B1c and Ppd-D1b alleles.

Table 2.

Frequencies of allelic variants of vernalization genes in wheat accessions from different ecological regions of China

| Combination | NWWR | NHWWR | SHWWR | WHWWR | MLYWWR | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NO. | % | NO. | % | NO. | % | NO. | % | NO. | % | |

| Vrn-B1c | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.4 | 1 | 4.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Vrn-B1b | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.2 | 1 | 1.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Vrn-D1a | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 4.3 | 20 | 27.4 | 1 | 4.0 | 1 | 100 |

| Vrn-D1b | 1 | 2.9 | 3 | 6.9 | 5 | 6.9 | 2 | 8.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Vrn-B1b + Vrn-D1a | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| vrn-1 | 34 | 97.1 | 41 | 89.1 | 45 | 61.6 | 21 | 84.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Total | 35 | 100.0 | 46 | 100.0 | 73 | 100.0 | 25 | 100.0 | 1 | 100.0 |

NWWR Northern Winter Wheat Region; NHWWR Northern of Huang-huai Winter Wheat region; SHWWR Southern of Huang-huai Winter wheat region; WHWWR Western of Huang-huai Winter wheat region; MLYWWR Middle and Lower Yangtze Valley Winter wheat region

The effects of different Vrn-1 genotypes on HD and FD were compared for the data collected from 2020–2022 by Wilcoxon tests, and it was found that materials carrying the Vrn-B1c + Vrn-D1a genotype exhibited earlier flowering. There were no significant differences in HD and FD between Vrn-B1b and Vrn-B1c materials, but the effect of Vrn-B1c on advancing flowering was stronger than that of Vrn-B1b. Comparing the effects of allelic variations in Vrn-D1a, Vrn-D1b, and vrn-D1 on HD and FD revealed that materials carrying the Vrn-D1a allele flowered significantly earlier (by 2.3 to 4.2 days) than those carrying the Vrn-D1b or Vrn-D1 alleles, except in HD_21DT and FD_21DT. However, there were no significant differences between materials with Vrn-D1b and vrn-D1 on HD and FD (Table 3). Vrn-B1b/c materials flowered by 0–7.8 days earlier than vrn-1 materials, but there was no significant difference across all environments, possibly due to a small sample size (Tables 2 and 3). Furthermore, an in-depth analysis of Vrn-D1 will be presented below.

Table 3.

Effects of Vrn-1 loci on HD and FD in NW and DT in 2020–2021 and 2021–2022

| Allelic variation of Vrn-1 |

Number | HD_20DT | FD_20DT | HD_20NW | FD_20NW | HD_21DT | FD_21DT | HD_21NW | FD_21NW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vrn-B1c + Vrn-D1a | 1 | 175 | 186 | 184 | 199 | 170 | 178 | 188 | 199 |

| Vrn-B1b | 2 | 181.5 ± 4.5AB | 190.5 ± 4.5ABa | 188.5 ± 5.5AB | 199 ± 5AB | 170.5 ± 2.5A | 179 ± 1.0A | 190.5 ± 1.5AB | 200.5 ± 1.5ABab |

| Vrn-B1c | 2 | 178 ± 2AB | 188.5 ± 2.5ABa | 188 ± 4.0AB | 199.5 ± 2.5AB | 166.5 ± 0.5A | 175.5 ± 0.5A | 192.5 ± 1.5AB | 196.5 ± 4.5ABab |

| Vrn-D1a | 24 | 177.5 ± 0.57B | 188 ± 0.4Bb | 187.63 ± 0.7B | 200.63 ± 0.8B | 168.58 ± 0.5A | 177.29 ± 0.4A | 189.21 ± 0.7B | 198.38 ± 0.7Bb |

| Vrn-D1b | 11 | 179.64 ± 1.08AB | 190.36 ± 0.7ABa | 191.82 ± 1.5A | 202 ± 1.3AB | 169 ± 0.7A | 177.27 ± 0.6A | 190.64 ± 1AB | 199.36 ± 1.1ABab |

| vrn-1 | 140 | 180.94 ± 0.25A | 190.39 ± 0.2Aa | 191.83 ± 0.3A | 202.88 ± 0.2A | 169.24 ± 0.2A | 177.36 ± 0.1A | 191.8 ± 0.2A | 200.83 ± 0.2Aa |

Different capital orlowercase letters indicate significant differences between the combinations of VRN-1 at the P < 0. 01 or P < 0.05 level, respectively. NW normal watering; DT drought treatment

Genetic diversity, population structure, and linkage disequilibrium

After removing low-quality SNP makers (MAF < 0.05 and missing values ≥ 0.1), a total of 273,329 SNPs remained, with an average SNP density of 0.072. The number of SNPs varied among different chromosomes, ranging from 2284 on 4D to 33, 706 on 3B (Supplemental Fig. S3). Similarly, the SNP density varied across chromosomes, ranging from 0.025 on 3B to 0.223 on 4D (Supplemental Fig. S3A, B). Additionally, 21,040 blocks, designated as block 1 on 1A to block 21, 040 on 7D, were identified from the pool of 273,329 SNPs using Plink1.9 software (https://github.com/chrchang/plink-ng). These blocks were distributed across all chromosomes, with the block numbers varying from 181 on 4D to 1, 944 on 3B (Supplemental Fig. S3).

The population structure was determined using ADMIXTURE-1.3.0 (Alexander et al. 2009) based on the remaining 273, 329 SNPs that spanned the whole genome and were distributed across all chromosomes. The ADMIXTURE analysis revealed the presence of eight distinct subgroups within the 190 wheat samples of the AMP (Fig. 1A, C), and classified the natural population into eight sub-populations (Fig. 1B). These sub-populations were designated SpI, SpII, SpIII, SpIV, SpV, SpVI, SpVII and SpVIII, comprising 22, 23, 10, 36, 27, 14, 24, and 34 accessions, respectively. Notably, the HD and FD of SpV were significantly lower than those of the other sub-populations, primarily consisting of wheat cultivars from the SHWWR (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table S1).

Fig. 1.

Population structure, kinship and linkage disequilibrium analysis of the diverse wheat panel used in this study based on 273, 329 SNP markers. A The distribution of CV error values from ADMIXTURE analysis; B Under the normal water conditions of 2021–2022, the heading status of HONG MANG MAI and Zhoumai 18 after 200 days of sowing; C The population structure inferred using the structure program with K set to 8. The labels I to VIII were assigned to represent the corresponding sub-populations. D The average linkage disequilibrium (LD) decay across the genome was assessed over physical distances. Plots were generated to display the LD r2 values between pairs of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) as a function of the inter-marker map distance (measured in kilobases, Kb), utilizing the IWGSC RefSeq v.1.1 database. To determine the significance of the LD r2 values, the critical value was chosen as half of the maximum value

Fig. 2.

Boxplot of HD and FD based on NW, DT and BLUE values for different sub-populations in the diversity panel. The eight subpopulations from SpI to SpVIII contained 22, 23, 10, 36, 27, 14, 24 and 34 accessions, respectively. The HD and FD of SpV were significantly lower than those of the other sub-populations, primarily consisting of wheat cultivars from the SHWWR. HD_NW, HD_DT, and HD_BLUE, heading date for normal watering in the field, drought stress and BLUE, respectively; FD_NW, FD_DT, and FD_BLUE, flowering date for normal watering in the field, drought stress and BLUE, respectively

The extent of LD was estimated using 106,615, 130,159, and 36,555 SNP loci from the A, B, and D sub-genomes, respectively. The whole-genome LD analysis was conducted with 273, 329 SNPs, and pairwise LD was estimated using the squared-allele frequency correlation (r2) (Dong et al. 2021). A plot illustrating LD estimates (r2) against physical distance (Kb) clearly demonstrated a significant decrease in LD as physical distance increased (Fig. 1D). To determine the significance level for r2, half of the maximum value was chosen as the critical threshold (Huang et al. 2010). The average LD decay distance for the entire genome was approximately 2.06 Mb, with the smallest decay observed at 1.54 Mb for the D sub-genome, while it was 1.78 Mb and 2.86 Mb for the A and B sub-genomes, respectively (Fig. 1D).

QTLs detected for HD and FD based on BLUE values by two GWAS methods

HB-GWAS and SNP-GWAS were conducted for HD and FD using the combined across-environment BLUE values of the 190 accessions. The Q-Q plot demonstrated effective control of false-positives in the GWAS model (Fig. 3). The HB-GWAS identified 6, 7, and 7 QTLs associated with HD, FD, and both HD and FD, respectively (Table 4). Meanwhile, the SNP-GWAS identified 3 QTLs for HD, 6 QTLs for FD, and 5 QTLs for both traits (Table 4). In total, 7 independent QTLs associated with HD and/or FD were identified using the two different GWAS methods (Table 4). The details of the detected QTLs for each trait are described below.

Fig. 3.

Q-Q and Manhattan plots of results from the two GWAS methods for HD_BLUE and FD_BLUE. A HD_BLUE (HB-GWAS). B HD_BLUE (SNP based-GWAS). C FD_BLUE (HB-GWAS). D FD_BLUE (SNP-based GWAS). The red line represents the threshold level of significance (-log10P > 3 in haplotype-based GWAS and -log10P > 4 in SNP-based GWAS). The information regarding Q-Q plots and significant Manhattan sites is provided in Table 4, Table 5, Supplementary Table 2, and Supplementary Table 3

Table 4.

Marker/haplotype-trait associations revealed by the SNP-based and haplotype-based GWAS approaches

| Traits | QTLs | Physical position (Mb) |

Haplotype-based GWAS | SNP-based GWAS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -1og10(P) | PVE(%) | Significant blocks | -1og10(P) | PVE(%) | Signifcant SNPs | |||

| HD | Qhd.nwafu-1B.1 | 1B:341.59–342.08 | 3.34 | 1.43% | block8679 | |||

| Qhd.nwafu-1B.2 | 1B:551.18 | 3.30 | 2.77% | block9123 | ||||

| Qhd.nwafu-1D.1 | 1D:449.29 | 4.18 | 6.12% | AX-109352933 | ||||

| Qhd.nwafu-1D.2 | 1D:484.17 | 4.86 | 7.33% | AX-94596406 | ||||

| Qhd.nwafu-5A.1 | 5A:18.64 | 3.00 | 5.10% | block4854 | ||||

| Qhd.nwafu-5A.2 | 5A:397.12 | 3.10 | 5.21% | block5127 | ||||

| Qhd.nwafu-7B | 7B:147.66–149.60 | 3.42 | 5.77% | block16943 | 4.01 | 5.83% | AX-110667024 | |

| FD | Qfd.nwafu-1A | 1A:489.60–490.09 | 4.31 | 3.30% | block920 | |||

| Qfd.nwafu-1B.1 | 1B:477.39–477.88 | 3.01 | 2.57% | block8958 | ||||

| Qfd.nwafu-2B | 2B:625.18 | 4.36 | 6.53% | AX-110587380 | ||||

| Qfd.nwafu-5B.1 | 5B:464.36–464.51 | 3.23 | 2.33% | block14565 | ||||

| Qfd.nwafu-5D.1 | 5D:462.57–464.11 | 4.19–4.28 | 6.23–6.39% | AX-111917011/AX-111234923/AX-110044748 | ||||

| Qfd.nwafu-5D.2 | 5D:475.38–476.31 | 3.19 | 6.28% | block19772 | 4.15–4.42 | 6.16–6.63% | AX-111129732/AX-89332803/AX-111660163/AX-111505625 | |

| Qfd.nwafu-6A | 6A:211.31 | 4.65 | 7.06% | AX-95008775 | ||||

| Qfd.nwafu-7B.1 | 7B:646.152–646.61 | 3.45 | 6.18% | block17433 | 4.17 | 6.18% | AX-111558145 | |

| Qfd.nwafu-7B.2 | 7B:711.36 | 3.08 | 4.14% | block17580 | ||||

| HD&FD | ||||||||

| HD | Qhf.nwafu-1B.1 | 1B:590.94–591.44 | 3.07 | 3.04% | block9235 | |||

| FD | 3.29 | 2.36% | block9235 | |||||

| HD | Qhf.nwafu-2A.1 | 2A:705.81–706.46 | 3.1 | 1.98% | block2659 | |||

| FD | 3.10–4.06 | 3.05%-6.27% |

block2659/ block2660/ block2661 |

4.19–4.21 | 6.22%-6.24% | AX-110410787/AX-110492985/AX-108966439 | ||

| HD | Qhf.nwafu-2A.2 | 2A:748.87–749.45 | 3.10 | 2.65% | block2879 | |||

| FD | 3.26–3.29 | 2.44%-4.39% |

block2879/ block2881 |

|||||

| HD | Qhf.nwafu-2B | 2B:450.76 | 3.38 | 5.21% | block10276 | |||

| FD | Qhf.nwafu-2B | 2B:447.79–450.76 | 3.18–3.31 | 4.97% | block10276 | |||

| HD | Qhf.nwafu-5B.1 | 5B:549.68–549.85 | 3.18 | 6.93% | block14777 | 4.33–4.63 | 6.38–6.92% | AX-111467695/AX-111216618/AX-108896917 |

| FD | 5B:549.85 | 4.12 | 6.11% | AX-108896917 | ||||

| HD | Qhf.nwafu-5B.2 | 5B:576.14 | 4.37 | 6.46% | AX-110595998 | |||

| FD | 5B:575.97–576.14 | 3.12 | 6.46% | block14874 | 4.11 | 6.09% | AX-108987083/AX-110595998 | |

| HD | Qhf.nwafu-5D.1 | 5D:465.09–465.11 | 5.13 | 9.58% | block19766 | 5.32–5.79 | 3.17%-9.03% | AX-110717870/AX-174253150/AX-109750213 |

| FD | 5D:465.1–476.31 | 5.52 | 6.28%-9.58% |

block19766/ block19772 |

5.29–6.02 | 8.23–9.58% | AX-110717870/AX-174253150/AX-109750213 | |

| HD | Qhf.nwafu-5D.2 | 5D:469.29–469.35 | 4.02–5.87 | 5.85–9.17% | AX-109360916/AX-110033637 | |||

| FD | 5D:469.29 | 7.43 | 12.31% | AX-109360916 | ||||

| HD | Qhf.nwafu-5D.3 | 5D:472.03–473.34 | 4.11 | 6.00% | AX-109870424 | |||

| FD | 5D:472.03–473.53 | 4.18–5.08 | 6.20–7.83% | AX-174251644/AX-174263729/AX-109870424/AX-109666105 | ||||

| HD | Qhf.nwafu-6B | 6B:31.86 | 3.78 | 5.17% | block15378 | |||

| FD | 6B:31.86 | 3.62 | 5.57% | block15378 | ||||

| HD | Qhf.nwafu-7D | 7D;384.66 | 3.01 | 2.97% | block20750 | |||

| HD | 7D:384.44–384.88 | 3.42 | 3.28% | block20750 | ||||

| Total numbera | 28 | 37 | ||||||

aThe number of significant haplotypes/SNPs identified by HB-GWAS and SNP-based GWAS

QTLs for HD and FD

A total of 9 QTLs were identified, with 13 significantly associated haplotypes and 24 SNPs, which played a role in regulating HD and FD. These QTLs were distributed on 6 chromosomes, namely 2A, 2B, 5B, 5D, 6B, and 7D (Fig. 3, Table 4).The proportion of variance explained (PVE) by these QTLs ranged from 1.98% to 9.58% among all the associated regions (Table 4; Supplementary Table S3). The QTLs Qhf.nwafu-2A.1, Qhf.nwafu-5B.1, Qhf.nwafu-5B.2, and Qhf.nwafu-5D.1, which were detected by both HB-GWAS and SNP-GWAS, exhibited a PVE ranging from 6.09% to 9.58%. Notably, the QTL Qhf.nwafu-5B.2 region (575.97–576.14 Mb) was found in the vicinity of the previously reported vernalization gene Vrn-B1. Additionally, the QTL Qhf.nwafu-5D.1 region (465.11–467.60 Mb) was linked to vernalization gene Vrn-D1, as determined by a significant representative haplotype (block19766/block19772, and AX-110717870/AX-174253150/ AX-109750213, Table 4). Based on the standard candidate interval prediction and marker detection results, Qhf.nwafu-5D.1 is considered to be the Vrn-D1 vernalization gene. A detailed analysis will be performed in the Discussion.

Furthermore, Qhf.nwafu-2A.1 (706.29–706.50 Mb) identified by both HB-GWAS and SNP-GWAS was found to be in close proximity to the QTL qHD2A.3 (707.7–707.8 Mb) previously reported (Table 4) (Pang et al. 2020). Qhf.nwafu-2B exhibited a physical interval on chromosome 2B similar to that of the QTL qHD2B.6 (418.6–455.5 Mb), which was previously reported (Pang et al. 2020). Notably, the QTL on 5B (549.68–549.85 Mb), identified by the highly associated haplotype block14777, overlapped with the QTL detected by SNP-GWAS (significant marker AX-111467695/AX-111216618/AX-108896917). As the 5B region has not been previously reported, it may be a novel candidate region. Furthermore, five new QTL regions were identified to be associated with HD and FD on 2A, 2B, 5B, 5D, and 7D in the current study (Table 4), while the accuracy of these newly discovered QTLs still needs to be further validated.

QTLs for HD

A total of 7 QTLs, comprising 5 significantly associated haplotypes and 3 SNPs, were identified as putatively involved in regulating HD. These QTLs were distributed on 4 chromosomes 1B, 1D, 5A, and 7B (Fig. 3). The PVE by these QTLs ranged from 1.43% to 7.33% (Table 4; Supplementary Table S5). Additionally, the QTL region Qhd.nwafu-1D.2 (484.17 Mb), identified by the significant SNP AX-94596406 in the study, was found to be in close proximity to the previously reported MQTL-1D-7 (485.96–494.47 Mb), (Yang et al. 2021). The QTL Qhd.nwafu-7B (147.73–150.82 Mb) was identified in both HB-GWAS and SNP-GWAS, and exhibited a PVE of 5.77%-5.83%. Further investigations are required for the remaining 5 QTLs: Qhd.nwafu-1B.1, Qhd.nwafu-1B.2, Qhd.nwafu-1D.1, Qhd.nwafu-5A.1, and Qhd.nwafu-5A.2.

QTLs for FD

A total of 9 QTLs, consisting of 6 significantly associated haplotypes and 10 SNPs, were identified as putatively involved in regulating FD. These QTLs were distributed across 7 chromosomes 1A, 1B, 2B, 5B, 5D, 6A, and 7B (Fig. 3). The PVE by these QTLs ranged from 2.33% to 6.63% (Table 4; Supplementary Table S5). Moreover, Qfd.nwafu-7B.1 (646.35Mb) represented by the most significantly associated haplotypes (block17433), overlapped with the QTL detected in the SNP-based GWAS (significant marker AX-111558145). Interestingly, the QTL Qfd.nwafu-5D.2 on chromosome 5D (475.38–476.28 Mb), represented by the most significantly associated haplotype (block19772), also overlapped with the QTL detected in the SNP-based GWAS (significant marker AX-111129732/AX-89332803/AX-111660163/AX-111505625). Additionally, Qfd.nwafu- 5D.1, identified by 3 SNPs (AX-111917011/AX-111234923/AX-110044748) in the SNP-GWAS, did not show any significantly associated haplotypes in the HB-GWAS.

Effects of QTLs detected by both GWAS approaches

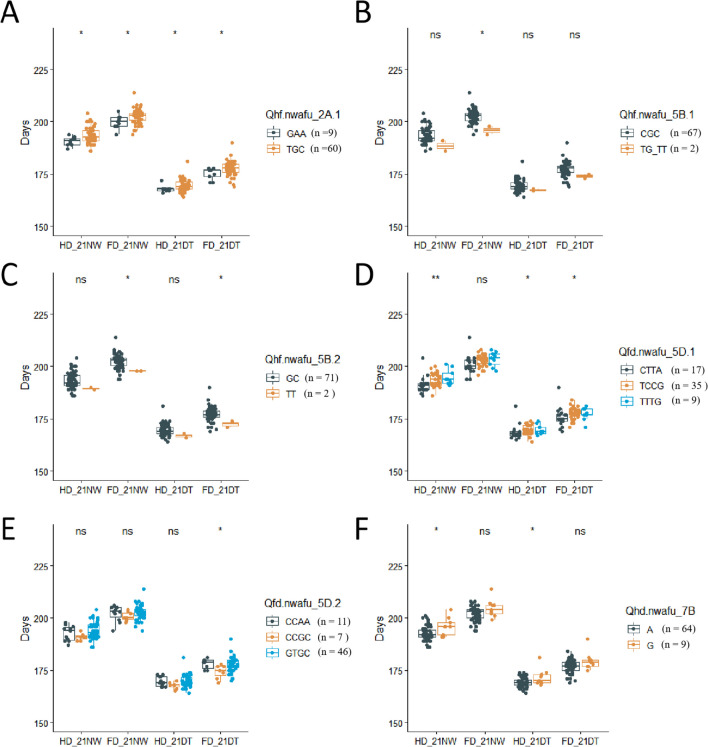

To investigate the impact of different QTLs on HD and FD, the 6 QTLs detected by both GWAS methods, which were associated with 7 blocks and represented by 13 significant SNPs, were selected to assess the significance of genotypic effects on HD and FD, employing the Wilcoxon signed rank test.

The HD and FD of cultivars with different alleles for the stable QTLs significantly associated with both HD and FD based on NW, DT, and BLUE were compared. At AX-110410787, AX-110492985 and AX-108966439 of Qhf.nwafu-2A.1, cultivars with the GAA allele (34 samples) headed and flowered 2.0 and 1.9 days earlier than those with the TGG allele (150 samples) (Fig. 4A). At AX-111467695, AX-111216618 and AX-108896917 of Qhf.nwafu-5B.1, cultivars with the TG_TT allele (11 samples, G_T means heterozygous genotypes G/T at this locus) headed and flowered 3.0 and 2.5 days eariler than those with the CGC (176 samples) allele (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, for the QTL Qhf.nwafu-5B.2, at markers AX-108987083 and AX-110595998, cultivars with the TT allele (9 samples) headed and flowered 3.2 and 3.0 days eariler, respectively, than those with the GC allele (177 samples) (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Phenotypic differences in HD and FD between the haplotypes of three QTLs related to HD and FD. Comparison of HD and FD between contrasting alleles at the QTLs Qhf.nwafu-2A.1 (A), Qhf.nwafu-5B.1 (B), and Qhf.nwafu-5B.2 (C), conducted using the Wilcoxon test. HD, heading date; FD, flowering date

Similarly, the HD and FD of cultivars with different alleles for the QTLs significantly associated with HD or FD, based on NW, DT and BLUE were compared. At AX-111129732, AX-89332803, AX-111660163, and AX-111505625 of Qfd.nwafu-5D.2, cultivars with either CCAA (44 samples) or CCGC (20 samples) exhibited earlier heading and flowering by 1.2 and 1.0 days, respectively, than those with the GTGC allele (113 samples)(Fig. 5A). Additionally, at AX-111558145 of Qfd.nwafu-7B.1, cultivars with the T allele (20 samples) headed and flowered 3.0 and 3.0 days earlier, respectively, compared to those with the G allele (168 samples) (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, at AX-110667024 of Qhd.nwafu-7B, cultivars with the A allele (154 samples) headed and flowered 2.7 and 1.7 days earlier than those with the G (33 samples) allele (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

Phenotypic differences in HD and FD between the haplotypes of three QTLs related to HD or FD. Comparison of HD and FD between contrasting alleles at the QTLs Qfd.nwafu-5D.1 (A), Qhd.nwafu-7B (B), and Qfd.nwafu-7B.2 (C), conducted using the Wilcoxon test. HD, heading date; FD, flowering date

Validation of the QTLs in a population of 74 natural accessions

To further validate the stability of the previously identified QTLs, a validation analysis was conducted using a set of 74 accessions with the 660 k genotype data (Supplemental Table S4). The QTL Qhf.nwafu-2A.1 showed a significant difference in both HD and FD (Fig. 6A). Similarly, Qhf.nwafu-5B.2 exhibited significant differences in FD_21NW and FD_21DT (Fig. 6C). Furthermore, Qfd.nwafu-5D.1 displayed significant differences in HD_21NW, HD_21DT and FD_21DT (Fig. 6D). Importantly although the QTLs did not show significant differences in other environments, this may be attributed to limitations in the amount of available material and linkage distance.

Fig. 6.

Phenotypic differences in HD and FD between the haplotypes of six detected QTLs in a natural validation population. Comparison of HD and FD between contrasting alleles at the QTLs Qhf.nwafu-2A.1 (A), hf.nwafu-5B.1 (B), Qhf.nwafu-5B.2 (C), Qfd.nwafu-5D.1 (D), Qfd.nwafu-5D.2 (E), Qhd.nwafu-7B (F) conducted using the Wilcoxon test in a natural validation population with 74 accessions. HD, heading date; FD, flowering date

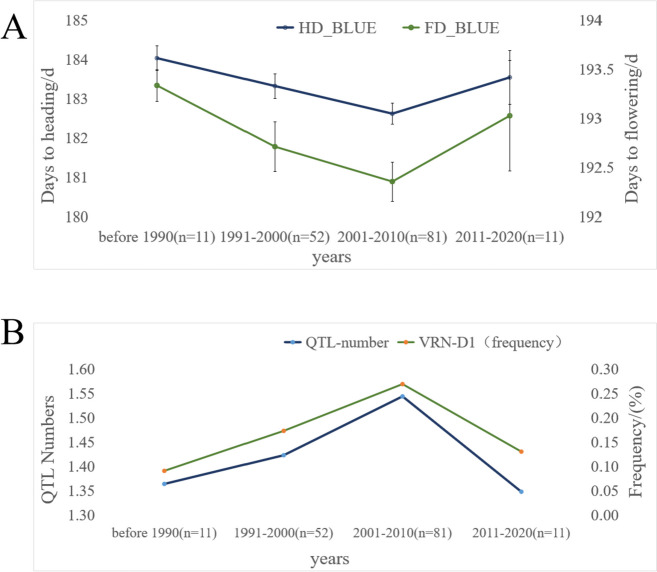

The frequency of precociousness alleles increased over the year of registration

The phenotypic performance of traits is influenced by both environmental factors and genotype. In the present study, 6 QTLs were detected using HB-GWAS and SNP-GWAS approaches. A total of 155 varieties were divided into four-year groups based on their release years (Supplementary Table S5). For each trait, as well as for all traits collectively, the average number of precociousness alleles in cultivars harboring representative QTLs within each year group was recorded (Fig. 7). The analysis revealed an increasing trend in the average number of precociousness alleles for the six identified QTLs, increasing from 1.36 in the period before 1990 to 1.54 in the 2001–2010 period. Simultaneously, the average frequency of Vrn-D1a/b alleles also increased sharply from 9.09% before 1990 to 26.92% in 2001–2010 (Fig. 7). Furthermore, the average number of 6 superior alleles related to precocity in the QTLs, along with the frequency of Vrn-D1a/b alleles increased, contributing to the earlier heading and flowering dates observed from before 1990 to 2001–2010 (Fig. 7). The gradual increase in the frequency of Vrn-D1a/b alleles in the cultivars over the release years could be attributed to the development of functional markers for Vrn-D1a/b and the implementation of molecular marker-assisted breeding in wheat breeding programs.

Fig. 7.

Changes in heading date (HD) and flowering date (FD) in wheat cultivars released over the past four decades, revealed by the days to heading (flowering) and occurrence frequency of QTLs related to HD and FD as well as Vrn-D1 loci in the cultivars of the release years. A. Changes in HD and FD in the cultivars over the release years. B. Change in frequencies of Vrn-D1 and the number of detected QTLs in the cultivars over the release years. The average number of 6 precocious superior alleles for precociousness of QTLs and the average frequency of Vrn-D1a/b increased, resulting in early heading and flowering dates from before 1990 to 2001-2010. The genotypic information of the cultivars was obtained from the detection of molecular markers and the 660 K SNP array. Additionally, data regarding the release years of the cultivars were sourced from the internet, such as https://www.a-seed.cn, and others

Discussion

Flowering is a complex trait, and several key genes for this trait have been cloned (Yan et al. 2003, 2004, 2006; Yoshida et al. 2010). In recent years, GWAS has emerged as powerful tools for identifying novel loci associated with HD and FD in bread wheat. This has facilitated the discovery of valuable genetic markers for molecular breeding. Previous studies have identified significant associations of HD and FD with certain SNPs located on chromosomes 1B, 3D, and 7D while excluding known photoperiod and vernalization loci (Chen et al. 2020a, b; Gupta et al. 2020; Zhang et al. 2018). Furthermore, many newly identified genes or QTLs have been reported to play essential roles in regulating flowering time and related biological functions (Cao et al. 2021; Mizuno et al. 2012; Zhang et al. 2021). In the present study, a diverse panel of 190 varieties was comprehensively evaluated through multi-environment field trials, enabling us to uncover the genetic architectures underlying HD and FD through GWAS. This research will facilitate the introgression of superior alleles into new wheat varieties, enhancing their adaptability to climate change.

The Vrn-D1 gene is predominant in Huang-huai wheat

The Huang-huai winter wheat production region is the most important and largest wheat production region in China, contributing 60–70% of the total wheat production in China. To mitigate the adverse effects of high temperatures in summer, farmers typically opt for early-maturing wheat varieties. As important traits in plant reproduction, HD and FD, are tightly regulated by intricate genetic networks that directly impact wheat yield and adaptability (Dai and Xue 2010; Zhang et al. 2018). Among the known genes influencing HD and FD in wheat, vernalization genes, photoperiod genes, and early-maturity genes play pivotal roles (Seki et al. 2011).

Adapting to climate change necessitates selecting cultivars featuring various allelic variations in vernalization and photoperiod genes for different planting regions. Previous studies have underscored the comprehensive effects of vernalization and photoperiod genes on a wide range of traits (Cane et al. 2013; Kamran et al. 2014; Kane et al. 2008; Sun et al. 2014; Arjona et al. 2020; Whittal et al. 2018; Xu et al. 2021). In this study, it was found that the wheat materials with Vrn-D1a flowered 0.1–4.2 days earlier than those with Vrn-D1b or vrn-D1, while no difference in HD and FD was observed between Vrn-D1b and vrn-D1 (Table 3). In the Huang-Huai region, the proportions of Vrn-D1a and Vrn-D1b alleles were 16.7% (24) and 6.9% (10), respectively, indicating that allelic variation in Vrn-D1 primarily accounted for the disparities in HD and FD among Huang-Huai wheat.

To verify whether Qfd.nwafu-5D.1 is a Vrn-D1 gene. The D' and r2 values of Vrn-D1 versus Qfd.nwafu-5D.1 were 0.6054 and 0.2237, respectively, confirming Vrn-D1 as a candidate gene for Qfd.nwafu-5D.1 (Tables 5 and 6). Nevertheless, certain variations in HD and FD remained unaccounted for by these loci. This study did not identify Vrn-A1 and Ppd-D1 among the GWAS results due to limited variant material (Supplemental Table S1). Furthermore, the Vrn-D1 allele was prevalent, with Vrn-D1a being the most common, followed by Vrn-B1 and Vrn-A1a. Similarly, the Ppd-D1a allele was also dominant in the analyzed accessions (Supplemental Table S1).

Table 5.

Information on known QTLs with physical positions close to the loci identified and candidate genes

| Traits | QTL | Physical position (Mb) |

Candidate gene | Previously reported QTL | Physical position (Mb) |

Associated traits (number) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HD | Qhd.nwafu-1B.1 | 1B:341.59–342.08 | In this study | ||||

| Qhd.nwafu-1B.2 | 1B:551.178272 | TraesCS1B02G320100 | MQTL-1B-4 | 1B:542.93–563.07 | GN(4), GW(3), TN(1), GY(1), SLN(1), BY(1) | Yang et al. 2021 | |

| Qhd.nwafu-1D.1 | 1D:449.29 | TraesCS1D02G360400 | MQTL-1D-5 | 1D:442.05–452.43 | GW(4), GN(1), GY(1), SL(1), SLN(1), DTH(1) | Yang et al. 2021 | |

| Qhd.nwafu-1D.2 | 1D:484.17 | TraesCS1D02G434100 | MQTL-1D-7 | 1D:485.96–494.47 | DTH(1), GW(1) | Yang et al. 2021 | |

| Qhd.nwafu-5A.1 | 5A:18.6351055 | MQTL5A.2 | 5A:13.2–15.2 | Saini et al. 2022 | |||

| Qhd.nwafu-5A.2 | 5A:397.119283 | MQTL5A.4 | 5A:399.8–401.8 | Saini et al. 2022 | |||

| Qhd.nwafu-7B | 7B:147.66–149.60 | TraesCS7B02G199600LC | In this study | ||||

| FD | Qfd.nwafu-1A | 1A:489.60–490.09 | In this study | ||||

| Qfd.nwafu-1B.1 | 1B:477.39–477.88 | In this study | |||||

| Qfd.nwafu-2B | 2B:625.18 | In this study | |||||

| Qfd.nwafu-5B.1 | 5B:464.36–464.51 | In this study | |||||

| Qfd.nwafu-5D.1 | 5D:462.57–464.11 | In this study | |||||

| Qfd.nwafu-5D.2 | 5D:475.38–476.31 |

TraesCS5D02G499800LC TraesCS5D02G412600 |

In this study | ||||

| Qfd.nwafu-6A | 6A:211.31 | In this study | |||||

| Qfd.nwafu-7B.1 | 7B:646.15–646.61 | TraesCS7B02G381500(gl6) | MQTL-7B-4 | 7B:639.36–654.93 | GW(9), TN(2), GN(1), DTH(1), Others(1) | Yang et al. 2021 | |

| Qfd.nwafu-7B.2 | 7B:711.36 | TraesCS7B02G443500 | MQTL-7B-6 | 7B:697.54–707.72 | GW(3), GFR(1), DTM(1) | Yang et al. 2021 | |

| HD&FD | Qhf.nwafu-1B.1 | 1B:590.94–591.44 | TraesCS1B02G352200 | MQTL-1B-5 | 1B:587.05–606.49 | GW(3), GY(3), SL(1) | Yang et al. 2021 |

| Qhf.nwafu-2A.1 | 2A:705.81–706.46 |

TraesCS2A02G459200 (both) TraesCS2A02G458600 TraesCS2A01G459700 |

qHD2A.3 | 2A:707.7–707.8 | HD | Pang et al. 2020 | |

| Qhf.nwafu-2A.2 | 2A:748.87–749.45 | In this study | |||||

| Qhf.nwafu-2B | 2B:447.79–450.76 | qHD2B.6 | 2B:418.6–455.5 | HD | Pang et al. 2020 | ||

| Qhf.nwafu-5B.1 | 5B:549.68–549.85 |

TraesCS5B02G371600 TraesCS5B02G564000 TraesCS5B02G370700 TraesCS5B02G563700 |

In this study | ||||

| Qhf.nwafu-5B.2 | 5B:575.97–576.14 |

TraesCS5B02G396900 TraesCS5B02G399800 |

qHD5B.3 qHD5B.4 |

5B:573.6–573.9 5B:574.3–574.4 |

HD | Pang et al. 2020 | |

| Qhf.nwafu-5D.1 | 5D:465.09–465.11 | Vrn-D1 |

Table 6.

Linkage disequilibrium analysis of vrn-B1 and vrn-D1 and their association with the nearby QTL

| Vrn-B1&Qhf.nwafu-5B.2 | Vrn-D1&Qhf.nwafu-5D.1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P(Vrn-B1)* P(Qhf.nwafu-5B.2) |

Vrn-B1b | Vrn-B1c | vrn-B1 | P(Vrn-D1)* P(Qfd.nwafu-5D.1) |

Vrn-D1a | Vrn-D1b | vrn-D1 |

| GC | 0.0214 | 0.0161 | 0.9116 | CTA | 0.032 | 0.012 | 0.176 |

| TT | 0.0011 | 0.0009 | 0.0488 | TCG | 0.100 | 0.039 | 0.545 |

| TTG | 0.014 | 0.005 | 0.077 | ||||

| P(TT*Vrn-B1b) | 0.0113 | P(Vrn-D1*Qhf.nwafu-5D.1) | 0.1017 | ||||

| D(Vrn-B1*Qhf.nwafu-5B.2) | 0.0102 | D(CTA&Vrn-D1a) | 0.0693 | ||||

| r2(Vrn-B1&Qhf.nwafu-5B.2) | 0.1281 | r2(Vrn-D1&Qhf.nwafu-5D.1) | 0.2237 | ||||

| D'(Vrn-B1&Qhf.nwafu-5B.2) | 0.631 | D'(Vrn-D1&Qhf.nwafu-5D.1) | 0.6054 | ||||

The flowering time of different genetic allelic variants are as follows: Vrn-B1, Vrn-B1c < Vrn-B1b < = vrn-B1; Qhf.nwafu-5B.2, TT < GG; Vrn-D1, Vrn-D1a < Vrn-1b < = vrn-D1; Qhf.nwafu-5D.1, CTA < TTG < = TCG

Different values are calculated as shown in the following formula:

Putative candidate genes within three intervals on chromosomes 2A and 5B

Overall, the average LD decay distance for the whole genome was approximately 2.06 Mb. Notably, LD decayed faster in the D sub-genome (1.54 Mb) than in the A (1.78 Mb) and B (2.86 Mb) sub-genomes (Fig. 1D). In the present study, the LD block interval containing the associated markers was investigated to identify potential candidate genes. For instance, the genomic region on chromosome 2A (705.96-706.46 Mb) associated with HD and FD was consistently detected by both GWAS methods. Accordingly, 19 genes located in this region were analyzed based on their annotations and expression patterns (Supplementary Table S6, Supplemental Fig. S4). TraesCS2A02G459200, encoding an SRF-type MADS-box transcription factor as the candidate gene of Qhf.nwafu-2A.1, was considered to make significant contributions to heading and flowering dates. Moreover, TraesCS2A02G458600 as Ubiquitin, which may also play an important role in the control of photoperiodic flowering (Piñeiro and Jarillo 2013).

The SNP-GWAS and HB-GWAS identified additional regions on chromosome 5B at approximately 549.68-549.85 Mb and 575.97-576.14 Mb associated with heading date (HD) and flowering date (FD). Among these regions, TraesCS5B02G371600, encoding the Zinc finger 512B protein, was significantly upregulated in the peduncle compared to other tissues (Table 5, Supplementary Table S6, Supplemental Fig. S5). Furthermore, TraesCS5B02G564000, TraesCS5B02G370700, and TraesCS5B02G563700 were also considered candidate genes for Qhf.nwafu-5B.1 based on their annotations and expression patterns (Table 5, Supplemental Fig. S5).

Despite the proximity between the vernalization gene Vrn-B1 (Chr5B:550.21 Mb), as reported by Yan et al. (2003), and Qfd.nwafu-5B.2 (575.97-576.14 Mb), Whether Qfd.nwafu-5B.2 was the Vrn-B1 gene still needed to be verified. The D' and r2 values of Vrn-B1 versus Qfd.nwafu-5B.2 were 0.631 and 0.1281, respectively, indicating that Vrn-B1 may not be a candidate gene for Qfd.nwafu-5B.1 (Table 6). Nevertheless, cultivars with different Vrn-B1 allelic variants did not show significant differences in heading date (HD) and flowering date (FD) (Table 3). Furthermore, the genotype frequency of Vrn-B1b/c was only 4.1% (Table 2), and the SNP associated with it was excluded by the MAF filter. This regions contains TraesCS5B02G396900, which codes for a COBRA-like protein, known as OsBC1L4 in rice (Dai et al. 2011). Interestingly, COBRA-LIKE 10, a GPI-anchored protein, has been found to mediate the directional growth of pollen tubes in Arabidopsis (Li et al. 2013). Furthermore, TraesCS5B02G399800 (UDP-glucose 6-dehydrogenase) and TraesCS5B02G397800 (50S ribosomal protein L13) were regarded as potential candidate genes for Qhf.nwafu-5B.2 based on their annotations and expression patterns (Supplemental Fig. S6). However, additional experimental studies are necessary to investigate the specific roles of these genes in regulating HD and FD in wheat.

Conclusions

A total of 7 QTLs related to HD and FD, including the Vrn-D1 gene, were identified using both SNP-based and haplotype-based GWAS in a population of 190 common wheat accessions. The significant loci were further validated in a new population of 74 individuals. Additionally, from before 1990 to 2011-2020, the average number of six early-maturity superior alleles of QTLs and the average frequency of Vrn-D1a/b increased, resulting in earlier heading and flowering time. These insights offer valuable guidance for crop enhancement, enabling improved adaptability and productivity under evolving climatic scenarios.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

Y.G.H. and L.C. designed the experiment, P.F.Q and X.L performed the experiment and wrote the paper, D.Z.L., S.L. L.Z. collected the previous studies, P.F.Q., A.R analyzed the data, Y.G.H. and L.C. reviewed the paper. All authors read and approved the article.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32171991), the Key Research and Development Program of Shaanxi Province (2021KWZ-23), Chinese Universities Scientific Fund (2452021166), the China 111 Project (B12007), the Construction of Overseas Demonstration Zone and the Tang Chung Ying Breeding Funds (NWAFU), P. R. China.

Data availability

All data that support the findings in this study are available in this article and its supplementary files. Furthermore, the R code used for conducting the statistical analysis has been submitted and is available at the following repository: https://github.com/qiao-001/SNP_HBbaseGWAS.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abboye AD, Megersa A, Hirpa D. Effect of Plant Population on Growth, Yields & Quality of Bread Wheat (Triticum Aestivum L.) Varieties at Kulumsa in Arsi Zone, South-Eastern Ethiopia. Int J Res Stud Agric Sci. 2020;6(2):32–53. doi: 10.20431/2454-6224.0602005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aldrich J, Cullis CA. RAPD analysis in flax: Optimization of yield and reproducibility using klen Taq 1 DNA polymerase, chelex 100, and gel purification of genomic DNA. Plant Mol Biol Report. 1993;11(2):128–141. doi: 10.1007/BF02670471. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander DH, Novembre J, Lange K. Fast model-based estimation of ancestry in unrelated individuals. Genome Res. 2009;19:1655–1664. doi: 10.1101/gr.094052.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amasino RM, Michaels SD. The timing of flowering. Plant Physiol. 2010;154(2):516–520. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.161653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andeden E, Yediay F, Baloch F, Shaaf S, Kilian B, Nachit M, Özkan H. Distribution of vernalization and photoperiod genes (Vrn-A1, Vrn-B1, Vrn-D1, Vrn-B3, Ppd-D1) in Turkish bread wheat cultivars and landraces. Cereal Res Commun. 2011;39(3):352–364. doi: 10.1556/CRC.39.2011.3.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arjona JM, Villegas D, Ammar K et al (2020) The effect of photoperiod genes and flowering time on yield and yield stability in durum wheat. Plants 9:1723. 10.3390/plants9121723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker BM, Walker SC (2014) Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4. 1. 10.18637/jss.v067.i01

- Boden SA, Cavanagh C, Cullis BR, Ramm K, Greenwood J, Jean Finnegan E, Trevaskis B, Swain SM. Ppd-1 is a key regulator of inflorescence architecture and paired spikelet development in wheat. Nat Plants. 2015;1(January):2–7. doi: 10.1038/nplants.2014.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cane K, Eagles HA, Laurie DA, Trevaskis B, Vallance N, Eastwood RF, Gororo NN, Kuchel H, Martin PJ. Ppd-B1 and Ppd-D1 and their effects in southern Australian wheat. Crop Pasture Sci. 2013;64(2):100–114. doi: 10.1071/CP13086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y, Hu G, Zhuang M, Yin J, Wang X. Molecular cloning and functional characterization of TaIRI9 gene in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Gene. 2021;791:145694. doi: 10.1016/J.GENE.2021.145694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capovilla G, Schmid M, Posé D. Control of flowering by ambient temperature. J Exp Bot. 2015;66(1):59–69. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai L, Xin M, Dong C, Chen Z, Zhai H, Zhuang J, Cheng X, Wang N, Geng J, Wang X, Bian R, Yao Y, Guo W, Hu Z, Peng H, Bai G, Sun Q, Su Z, Liu J, Ni Z. A natural variation in Ribonuclease H-like gene underlies Rht8 to confer “Green Revolution” trait in wheat. Mol Plant. 2022;15(3):377–380. doi: 10.1016/J.MOLP.2022.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Chen H, Zhang Y, Thomas HR, Frank MH, He Y, Xia R. TBtools: An Integrative Toolkit Developed for Interactive Analyses of Big Biological Data. Shengwei Ma, Meng Wang, Jianhui Wu, Weilong Guo, Yongming Chen, Guangwei Li, Yanpeng Wang, Weiming Shi, Guangmin Xia, Daolin Fu, Zhensheng Kang, Fei Ni. 2020;13(8):1194–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2020.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Cheng X, Yu K, Chang X, Bi H, Xu H, Wang J, Pei X, Zhang Z, Zhan K. Genome-wide association study of differences in 14 agronomic traits under low- and high-density planting models based on the 660k SNP array for common wheat. Plant Breed. 2020;139(2):272–283. doi: 10.1111/pbr.12774. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cho EJ, Kang C-S, Jung J-U, Yoon YM, Park CS. Allelic variation of Rht-1, Vrn-1 and Ppd-1 in Korean wheats and its effect on agronomic traits. Plant Breed Biotechnol. 2015;3(2):129–138. doi: 10.9787/pbb.2015.3.2.129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K, Kim J, Hwang HJ, Kim S, Park C, Kim SY, Lee I. The FRIGIDA complex activates transcription of FLC, a strong flowering repressor in Arabidopsis, by recruiting chromatin modification factors. Plant Cell. 2011;23(1):289–303. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.075911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chumanova EV, Efremova TT, Kruchinina YV. The effect of different dominant VRN alleles and their combinations on the duration of developmental phases and productivity in common wheat lines. Russ J Genet. 2020;56(7):822–834. doi: 10.1134/S1022795420070029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dai C, Xue HW. Rice early flowering1, a CKI, phosphorylates della protein SLR1 to negatively regulate gibberellin signalling. EMBO J. 2010;29(11):1916–1927. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai X, You C, Chen G, Li X, Zhang Q, Wu C. OsBC1L4 encodes a COBRA-like protein that affects cellulose synthesis in rice. Plant Mol Biol. 2011;75(4–5):333–345. doi: 10.1007/S11103-011-9730-Z/FIGURES/7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Distelfeld A, Li C, Dubcovsky J. Regulation of flowering in temperate cereals. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2009;12(2):178–184. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong SS, He WM, Ji JJ, Zhang C, Guo Y, Yang TL. LDBlockShow: a fast and convenient tool for visualizing linkage disequilibrium and haplotype blocks based on variant call format files. Brief Bioinform. 2021;22(4):1–6. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbaa227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyck JRB, Cheng JF, Stanley WC, Barr R, Chandler MP, Brown S, Wallace D, Arrhenius T, Harmon C, Yang G, Nadzan AM, Lopaschuk GD (2004) Malonyl coenzyme a decarboxylase inhibition protects the ischemic heart by inhibiting fatty acid oxidation and stimulating glucose oxidation. Circ Res 94(9). 10.1161/01.res.0000129255.19569.8f [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ellis MH, Bonnett DG, Rebetzke GJ. A 192bp allele at the Xgwm261 locus is not always associated with the Rht8 dwarfing gene in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Euphytica. 2007;157(1–2):209–214. doi: 10.1007/s10681-007-9413-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Z, Song Y, Zhou R, Ren Z, Jia J. Discovery, evaluation and distribution of haplotypes of the wheat Ppd-D1 gene. New Phytol. 2010;185(3):841–851. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.03099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta P, Kabbaj H, Hassouni KE, Maccaferri M, Sanchez-Garcia M, Tuberosa R, Bassi FM. Genomic regions associated with the control of flowering time in durum wheat. Plants. 2020;9(12):1–18. doi: 10.3390/plants9121628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamazaki K, Iwata H. Rainbow: Haplotype-based genome-wide association study using a novel SNP-set method. PLoS Comput Biol. 2020;16(2):e1007663. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1007663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris FAJ, Eagles HA, Virgona JM, Martin PJ, Condon JR, Angus JF. Effect of VRN1 and PPD1 genes on anthesis date and wheat growth. Crop Pasture Sci. 2017;68(3):195–201. doi: 10.1071/CP16420. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Wei X, Sang T, Zhao Q, Feng Q, Zhao Y, Li C, Zhu C, Lu T, Zhang Z, Li M, Fan D, Guo Y, Wang A, Wang L, Deng L, Li W, Lu Y, Weng Q, … Han B (2010) Genome-wide association studies of 14 agronomic traits in rice landraces. Nat Genet 42:11:961–967. 10.1038/ng.695 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Huo H, Wei S, Bradford KJ. DELAY OF GERMINATION1 ( DOG1) regulates both seed dormancy and flowering time through microRNA pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2016;113(15):E2199–E2206. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1600558113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia H, Wan H, Yang S, Zhang Z, Kong Z, Xue S, Zhang L, Ma Z. Genetic dissection of yield-related traits in a recombinant inbred line population created using a key breeding parent in China’s wheat breeding. Theor Appl Genet. 2013;126(8):2123–2139. doi: 10.1007/s00122-013-2123-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamran A, Iqbal M, Spaner D. Flowering time in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.): A key factor for global adaptability. Euphytica. 2014;197(1):1–26. doi: 10.1007/s10681-014-1075-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kane NA, Agharbaoui Z, Diallo AO, Adam H, Tominaga Y, Ouellet F, Sarhan F. TaVRT2 represses transcription of the wheat vernalization gene TaVRN1 (Plant Journal (2007) 51, (670–680)) Plant J. 2008;53(2):400. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kippes N, Debernardi JM, Vasquez-Gross HA, Akpinar BA, Budak H, Kato K, Chao S, Akhunov E, Dubcovsky J. Identification of the VERNALIZATION 4 gene reveals the origin of spring growth habit in ancient wheats from South Asia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(39):E5401–E5410. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1514883112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiseleva AA, Potokina EK, Salina EA (2017) Features of Ppd-B1 expression regulation and their impact on the flowering time of wheat near-isogenic lines. BMC Plant Biol 17(Suppl 1). 10.1186/s12870-017-1126-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kosová K, Prášil IT, Vítámvás P. The relationship between vernalization- and photoperiodically-regulated genes and the development of frost tolerance in wheat and barley. Biol Plant. 2008;52(4):601–615. doi: 10.1007/s10535-008-0120-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Law CN, Worland AJ. The control of adult-plant resistance to yellow rust by the translocated chromosome 5BS-7BS of bread wheat. Plant Breed. 1997;116(1):59–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0523.1997.tb00975.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Ge FR, Xu M, Zhao XY, Huang GQ, Zhou LZ, Wang JG, Kombrink A, McCormick S, Zhang XS, Zhang Y. Arabidopsis COBRA-LIKE 10, a GPI-anchored protein, mediates directional growth of pollen tubes. Plant J. 2013;74(3):486–497. doi: 10.1111/TPJ.12139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Xiong H, Guo H, Zhou C, Xie Y, Zhao L, Gu J, Zhao S, Ding Y, Liu L. Identification of the vernalization gene VRN-B1 responsible for heading date variation by QTL mapping using a RIL population in wheat. BMC Plant Biol. 2020;20(1):1–15. doi: 10.1186/s12870-020-02539-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma S, Wang M, Wu J, Guo W, Chen Y, Li G, Wang Y, Shi W, Xia G, Fu D, Kang Z, Ni F. WheatOmics: a platform combining multiple omics data to accelerate functional genomics studies in wheat. Mol Plant. 2021;1674(21):430. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2021.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell RAC, Castells-Brooke N, Taubert J, Verrier PJ, Leader DJ, Rawlings CJ. Wheat Estimated Transcript Server (WhETS): A tool to provide best estimate of hexaploid wheat transcript sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(SUPPL.2):148–151. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno N, Nitta M, Sato K, Nasuda S. A wheat homologue of PHYTOCLOCK 1 is a candidate gene conferring the early heading phenotype to einkorn wheat. Genes Genet Syst. 2012;87(6):357–367. doi: 10.1266/ggs.87.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohler V, Lukman R, Ortiz-Islas S, William M, Worland AJ, Van Beem J, Wenzel G. Genetic and physical mapping of photoperiod insensitive gene Ppd-B1 in common wheat. Euphytica. 2004;138(1):33–40. doi: 10.1023/B:EUPH.0000047056.58938.76. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Okada T, Jayasinghe JEARM, Eckermann P, Watson-Haigh NS, Warner P, Hendrikse Y, Baes M, Tucker EJ, Laga H, Kato K, Albertsen M, Wolters P, Fleury D, Baumann U, Whitford R (2019) Effects of Rht-B1 and Ppd-D1 loci on pollinator traits in wheat. Theor Appl Genet 0123456789. 10.1007/s00122-019-03329-w [DOI] [PubMed]

- Pang Y, Liu C, Wang D, st. Amand P, Bernardo A, Li W, He F, Li L, Wang L, Yuan X, Dong L, Su Y, Zhang H, Zhao M, Liang Y, Jia H, Shen X, Lu Y, Jiang H, … Liu S (2020) High-resolution genome-wide association study identifies genomic regions and candidate genes for important agronomic traits in wheat. Mol Plant 13(9):1311–1327. 10.1016/j.molp.2020.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Piñeiro M, Jarillo JA (2013) Ubiquitination in the control of photoperiodic flowering. In: Plant Science (Vol 198), pp 98–109. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2012.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ramírez-González RH, Borrill P, Lang D, Harrington SA, Brinton J, Venturini L, Davey M, Jacobs J, van Ex F, Pasha A, Khedikar Y, Robinson SJ, Cory AT, Florio T, Concia L, Juery C, Schoonbeek H, Steuernagel B, Xiang D, … Uauy C (2018) The transcriptional landscape of polyploid wheat. Science 361(6403). 10.1126/science.aar6089 [DOI] [PubMed]

- R Core Team (2021) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna. https://www.R-project.org/

- Saini DK, Srivastava P, Pal N, Gupta PK. Meta-QTLs, ortho-meta-QTLs and candidate genes for grain yield and associated traits in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Theor Appl Genet. 2022;135:1049–1081. doi: 10.1007/s00122-021-04018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seki M, Chono M, Matsunaka H, Fujita M, Oda S, Kubo K, Kiribuchi-Otobe C, Kojima H, Nishida H, Kato K. Distribution of photoperiod-insensitive alleles Ppd-B1a and Ppd-D1a and their effect on heading time in Japanese wheat cultivars. Breed Sci. 2011;61(4):405–412. doi: 10.1270/jsbbs.61.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shcherban AB, Börner A, Salina EA. Effect of VRN-1 and PPD-D1 genes on heading time in European bread wheat cultivars. Plant Breed. 2015;134(1):49–55. doi: 10.1111/pbr.12223. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada S, Ogawa T, Kitagawa S, Suzuki T, Ikari C, Shitsukawa N, Abe T, Kawahigashi H, Kikuchi R, Handa H, Murai K. A genetic network of flowering-time genes in wheat leaves, in which an APETALA1/FRUITFULL-like gene, VRN1, is upstream of FLOWERING LOCUS T. Plant J. 2009;58(4):668–681. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03806.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J, Irwin J, Dean C (2013) Remembering the prolonged cold of winter. Curr Biol 23(17). 10.1016/J.CUB.2013.07.027 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sun H, Guo Z, Gao L, Zhao G, Zhang W, Zhou R, Wu Y, Wang H, An H, Jia J. DNA methylation pattern of Photoperiod-B1 is associated with photoperiod insensitivity in wheat (Triticum aestivum) New Phytol. 2014;204(3):682–692. doi: 10.1111/nph.12948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C, Dong Z, Zhao L, Ren Y, Zhang N, Chen F. The Wheat 660K SNP array demonstrates great potential for marker-assisted selection in polyploid wheat. Plant Biotechnol J. 2020;18(6):1354–1360. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Zhang Z. GAPIT version 3: boosting power and accuracy for genomic association and prediction. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2021 doi: 10.1016/J.GPB.2021.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittal A, Kaviani M, Graf R, Humphreys G, Navabi A. Allelic variation of vernalization and photoperiod response genes in a diverse set of North American high latitude winter wheat genotypes. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(8):1–17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0203068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm EP, Boulton MI, Al-Kaff N, Balfourier F, Bordes J, Greenland AJ, Powell W, Mackay IJ. Rht-1 and Ppd-D1 associations with height, GA sensitivity, and days to heading in a worldwide bread wheat collection. Theor Appl Genet. 2013;126(9):2233–2243. doi: 10.1007/s00122-013-2130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worland AJ, Sayers EJ, Korzun V (2001) Allelic variation at the dwarfing gene Rht8 locus and its significance in international breeding programmes. In: Bedö Z, Láng L (eds) Wheat in a global environment: Proceedings of the 6th International Wheat Conference, 5–9 June 2000, Budapest, Hungary. Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, pp 747–753

- Würschum T, Langer SM, Longin CFH, Tucker MR, Leiser WL. A three-component system incorporating Ppd-D1, copy number variation at Ppd-B1, and numerous small-effect quantitative trait loci facilitates adaptation of heading time in winter wheat cultivars of worldwide origin. Plant Cell Environ. 2018;41(6):1407–1416. doi: 10.1111/pce.13167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu S, Dong Q, Deng M, Lin D, Xiao J, Cheng P, Xing L, Niu Y, Gao C, Zhang W, Xu Y, Chong K. The vernalization-induced long non-coding RNA VAS functions with the transcription factor TaRF2b to promote TaVRN1 expression for flowering in hexaploid wheat. Mol Plant. 2021;14(9):1525–1538. doi: 10.1016/J.MOLP.2021.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan L, Loukoianov A, Tranquilli G, Helguera M, Fahima T, Dubcovsky J. Positional cloning of the wheat vernalization gene VRN1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(10):6263–6268. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0937399100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan L, Loukoianov A, Blechl A, Tranquilli G, Ramakrishna W, SanMiguel P, Bennetzen JL, Echenique V, Dubcovsky J. The wheat VRN2 gene is a flowering repressor down-regulated by vernalization. Science. 2004;303(5664):1640–1644. doi: 10.1126/science.1094305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan L, Fu D, Li C, Blechl A, Tranquilli G, Bonafede M, Sanchez A, Valarik M, Yasuda S, Dubcovsky J. The wheat and barley vernalization gene VRN3 is an orthologue of FT. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(51):19581–19586. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607142103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang FP, Zhang XK, Xia XC, Laurie DA, Yang WX, He ZH. Distribution of the photoperiod insensitive Ppd-D1a allele in Chinese wheat cultivars. Euphytica. 2009;165(3):445–452. doi: 10.1007/s10681-008-9745-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Amo A, Wei D, Chai Y, Zheng J, Qiao P, Cui C, Lu S, Chen L, Hu YG. Large-scale integration of meta-QTL and genome-wide association study discovers the genomic regions and candidate genes for yield and yield-related traits in bread wheat. Theor Appl Genet. 2021;134(9):3083–3109. doi: 10.1007/s00122-021-03881-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin L, Zhang H, Tang Z, Xu J, Yin D, Zhang Z, Yuan X, Zhu M, Zhao S, Li X, Liu X. rMVP: a memory-efficient, visualization-enhanced, and parallel-accelerated tool for genome-wide association study. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.gpb.2020.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida T, Nishida H, Zhu J, Nitcher R, Distelfeld A, Akashi Y, Kato K, Dubcovsky J. Vrn-D4 is a vernalization gene located on the centromeric region of chromosome 5D in hexaploid wheat. Theor Appl Genet. 2010;120(3):543–552. doi: 10.1007/s00122-009-1174-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XK, Xiao YG, Zhang Y, Xia XC, Dubcovsky J, He ZH. Allelic variation at the vernalization genes Vrn-A1, Vrn-B1, Vrn-D1, and Vrn-B3 in Chinese wheat cultivars and their association with growth habit. Crop Sci. 2008;48(2):458–470. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2007.06.0355. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Gao M, Wang S, Chen F, Cui D. Allelic variation at the vernalization and photoperiod sensitivity loci in Chinese winter wheat cultivars (Triticum aestivum L.) Front Plant Sci. 2015;6(JULY):1–10. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Chen J, Yan Y, Yan X, Shi C, Zhao L, Chen F. Genome-wide association study of heading and flowering dates and construction of its prediction equation in Chinese common wheat. Theor Appl Genet. 2018;131(11):2271–2285. doi: 10.1007/s00122-018-3181-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K, Wang J, Qin H, Wei Z, Hang L, Zhang P, Reynolds M, Wang D. Assessment of the individual and combined effects of Rht8 and Ppd-D1a on plant height, time to heading and yield traits in common wheat. Crop J. 2019;7(6):845–856. doi: 10.1016/j.cj.2019.06.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Zhang H, Qiao L, Miao L, Yan D, Liu P, Zhao G, Jia J, Gao L (2021) Wheat MADS-box gene TaSEP3-D1 negatively regulates heading date. Crop J, xxxx. 10.1016/j.cj.2020.12.007

- Zhou H, Alexander D, Lange K. A quasi-Newton acceleration for high-dimensional optimization algorithms. Stat Comput. 2011;21(2):261–273. doi: 10.1007/s11222-009-9166-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data that support the findings in this study are available in this article and its supplementary files. Furthermore, the R code used for conducting the statistical analysis has been submitted and is available at the following repository: https://github.com/qiao-001/SNP_HBbaseGWAS.