A key challenge in cancer therapy is to balance potential survival benefit against treatment-related toxicity and subsequent impairment of Quality of Life (QoL). The oncologist’s role is not only to deliver the best quality anticancer treatment but also to consider the impact of the disease and treatment on each patient (Jordan et al. 2018). In Multiple Myeloma (MM) patients are usually continuously treated for several years. Continuous therapy, however, constantly exposes patients to displeasing side effects (Jordan et al. 2014). QoL in MM patients deteriorates with each subsequent line of therapy (Engelhardt et al. 2021). QoL measurements have been implemented as a secondary endpoint in almost all recent MM trials. Yet, it is important to note that the patients’ preference on a survival benefit versus a potentially impaired QoL has yet to be studied in MM, e.g. it is unknown whether patients would accept reduced survival for better QoL or vice-versa.

Maintenance therapy with lenalidomide (LEN) is a scenario in which this preference appears highly relevant (Richardson et al. 2022). On the one hand, two meta-analyses confirmed a progression-free survival (PFS) benefit in patients treated with LEN until progression of roughly 24 months compared to placebo or observation (McCarthy et al. 2017). On the other hand, a number of LEN-related side effects such as thromboembolism, diarrhea, peripheral neuropathy, constipation, and muscle pain were frequently observed (Pawlyn et al. 2014). Further, the incidence of second primary malignancies (SPMs) was reported to be three-fold higher for patients treated with LEN (Holstein et al. 2017). These negative effects, which mainly included grade 1 toxicities, sum up to a clear, yet undetermined deficit in QoL during LEN maintenance.

To address the question whether continuous LEN matches with the patient's preference on maintenance therapy, we analyzed patient reported outcome measures on maintenance therapy and related clinical endpoints in patients with MM. We actively involved MM patients to develop an online survey of 205 questions tailored especially to the needs of patients with MM under LEN maintenance therapy. The survey contained two validated questionnaires (EORTC, QoL questionnaires C30 and My20) on QoL and a set of additional questions pertaining to LEN toxicity and tolerability, which we developed together with a focus group of patients from the University Hospital Würzburg (Supplemental Table 1). To directly address the patient’s preference, we included an additional questionnaire that asked patients, whether they would choose a shortened time of PFS in favor of an increased QoL (Table 1). We distributed the online survey with the help of patient advocacy groups for MM patients in Germany. Patients who were interested in participating in our survey anonymously logged in to our public homepage and answered the questions. The survey was open for a timeframe of 50 days.

Table 1.

Patient preferences regarding outcome measures (PFS and QoL)

| Preference | All patients | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Long PFS | High QoL | None | ||

| Number of patients | 92 | 81 | 21 | 194 |

| Advanced treatment line | ||||

| Yes | 21 (11%) | 32 (16%) | 11 (6%) | 64 (33%) |

| No | 71 (37%) | 49 (25%) | 10 (5%) | 130 (67%) |

| Fisher exact test statistic value < 0.021 | The result is significant at p < 0.05 | |||

| Number of patients | 90 | 79 | 21 | 190 |

| Tendency to hand over responsibility to physicians | ||||

| Yes | 31 (16%) | 14 (7%) | 7 (4%) | 52 (27%) |

| No | 59 (31%) | 65 (34%) | 15 (8%) | 138 (73%) |

| Fisher exact test statistic value < 0.0153 | The result is significant at p < 0.05 | |||

| Number of patients | 92 | 76 | 18 | 186 |

| Diarrhoea | ||||

| Mild or none | 79 (42%) | 65 (35%) | 16 (9%) | 160 (86%) |

| Severe or very severe | 13 (7%) | 11 (6%) | 2 (1%) | 26 (14%) |

| Fisher exact test statistic value = 1 | The result is not significant at p < 0.05 | |||

| Number of patients | 90 | 75 | 19 | 184 |

| Nausea | ||||

| Mild or none | 87 (47%) | 72 (39%) | 19 (10%) | 178 (97%) |

| Severe or very severe | 3 (1.5%) | 3 (1.5%) | 0 | 6 (3%) |

| Fisher exact test statistic value = 1 | The result is not significant at p < 0.05 | |||

| Number of patients | 90 | 75 | 18 | 183 |

| Constipation | ||||

| Mild or none | 84 (46%) | 69 (38%) | 18 (9%) | 171 (93%) |

| Severe or very severe | 6 (3%) | 6 (3%) | 0 | 12 (6%) |

| Fisher exact test statistic value = 0.77 | The result is not significant at p < 0.05 | |||

| Number of patients | 90 | 76 | 19 | 185 |

| Fatigue | ||||

| Mild or none | 70 (38%) | 60 (32%) | 15 (8%) | 145 (78%) |

| Severe or very severe | 20 (11%) | 16 (9%) | 4 (2%) | 40 (22%) |

| Fisher exact test statistic value = 1 | The result is not significant at p < 0.05 | |||

| Number of patients | 92 | 76 | 19 | 187 |

| Fever | ||||

| Yes | 2 (1%) | 4 (2%) | 0 | 6 (3%) |

| No | 90 (48%) | 72 (39%) | 19 (10%) | 181 (97%) |

| Fisher exact test statistic value = 0.41 | The result is not significant at p < 0.05 | |||

| Number of patients | 90 | 73 | 19 | 182 |

| Upper airway infection | ||||

| Mild or none | 90 (49%) | 70 (38%) | 19 (10%) | 179 (96%) |

| Severe or very severe | 0 | 3 (2%) | 0 | 3 (2%) |

| Fisher exact test statistic value = 0.09 | The result is not significant at p < 0.05 | |||

| Number of patients | 90 | 76 | 19 | 185 |

| Pulmonary infection | ||||

| Mild or none | 85 (46%) | 74 (40%) | 19 (10%) | 178 (96%) |

| Severe or very severe | 5 (3%) | 2 (1%) | 0 | 7 (4%) |

| Fisher exact test statistic value = 0.46 | The result is not significant at p < 0.05 | |||

| Number of patients | 90 | 75 | 19 | 184 |

| Dyspnea | ||||

| Mild or none | 81 (44%) | 69 (38%) | 18 (9%) | 168 (91%) |

| Severe or very severe | 9 (5%) | 6 (3%) | 1 (1%) | 16 (9%) |

| Fisher exact test statistic value = 0.79 | The result is not significant at p < 0.05 | |||

| Number of patients | 91 | 76 | 19 | 186 |

| Vertigo | ||||

| Mild or none | 85 (46%) | 72 (39%) | 19 (10%) | 176 (95%) |

| Severe or very severe | 6 (3%) | 4 (2%) | 0 | 10 (5%) |

| Fisher exact test statistic value = 0.76 | The result is not significant at p < 0.05 | |||

| Number of patients | 91 | 75 | 19 | 185 |

| Sensory peripheral neuropathy | ||||

| Mild or none | 83 (45%) | 66 (36%) | 18 (9%) | 167 (90%) |

| Severe or very severe | 8 (4%) | 9 (5%) | 1 (1%) | 18 (10%) |

| Fisher exact test statistic value = 0.61 | The result is not significant at p < 0.05 | |||

| Number of patients | 89 | 75 | 19 | 183 |

| Secondary malignancy | ||||

| Yes | 6 (3%) | 3 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 10 (6%) |

| No | 83 (45%) | 72 (39%) | 18 (10%) | 173 (94%) |

| Fisher exact test statistic value = 0.51 | The result is not significant at p < 0.05 | |||

| Number of patients | 92 | 74 | 18 | 184 |

| General muscular weakness | ||||

| Yes | 35 (19%) | 32 (17%) | 9 (5%) | 76 (41%) |

| No | 57 (31%) | 42 (23%) | 9 (5%) | 108 (59%) |

| Fisher exact test statistic value = 0.53 | The result is not significant at p < 0.05 | |||

| Number of patients | 89 | 76 | 19 | 184 |

| Muscle cramps | ||||

| Mild or none | 74 (40%) | 62 (34%) | 17 (9%) | 153 (83%) |

| Severe or very severe | 15 (8%) | 14 (8%) | 2 (1%) | 31 (17%) |

| Number of patients | 91 | 76 | 19 | 186 |

| Thrombosis/thromboembolism | ||||

| Yes | 14 (8%) | 11 (6%) | 4 (2%) | 29 (16%) |

| No | 77 (41%) | 65 (35%) | 15 (8%) | 157 (84%) |

| Fisher exact test statistic value = 1 | The result is not significant at p < 0.05 | |||

| Number of patients | 88 | 78 | 21 | 187 |

| Back pain | ||||

| Yes | 10 (5%) | 4 (2%) | 3 (1%) | 17 (9%) |

| No | 78 (42%) | 74 (40%) | 18 (9%) | 170 (91%) |

| Fisher exact test statistic value = 0.17 | The result is not significant at p < 0.05 | |||

| Number of patients | 88 | 79 | 21 | 188 |

| Hip pain | ||||

| Yes | 87 (46%) | 78 (41%) | 21 (11%) | 186 (99%) |

| No | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 0 | 2 (1%) |

| Fisher exact test statistic value = 1 | The result is not significant at p < 0.05 | |||

| Number of patients | 91 | 80 | 20 | 191 |

| Arm or shoulder pain | ||||

| Yes | 46 (24%) | 51 (27%) | 8 (4%) | 105 (55%) |

| No | 45 (24%) | 29 (15%) | 12 (63%) | 86 (45%) |

| Fisher exact test statistic value = 0.09 | The result is not significant at p < 0.05 | |||

| Number of patients | 89 | 78 | 21 | 188 |

| Chest pain | ||||

| Yes | 24 (13%) | 27 (14%) | 9 (5%) | 60 (32%) |

| No | 65 (35%) | 51 (27%) | 12 (6%) | 128 (68%) |

| Fisher exact test statistic value = 0.32 | The result is not significant at p < 0.05 | |||

| Number of patients | 91 | 81 | 21 | 193 |

| Dry mouth | ||||

| Yes | 50 (26%) | 45 (23%) | 12 (6%) | 107 (55%) |

| No | 41 (21%) | 36 (19%) | 9 (5%) | 86 (45%) |

| Fisher exact test statistic value = 1 | The result is not significant at p < 0.05 | |||

| Number of patients | 90 | 78 | 21 | 189 |

| Hair loss | ||||

| Yes | 20 (11%) | 20 (11%) | 6 (3%) | 46 (24%) |

| No | 70 (37%) | 58 (31%) | 15 (8%) | 143 (76%) |

| Fisher exact test statistic value = 0.72 | The result is not significant at p < 0.05 | |||

| Number of patients | 91 | 81 | 21 | 193 |

| Heartburn | ||||

| Yes | 41 (21%) | 32 (17%) | 12 (6%) | 85 (44%) |

| No | 50 (26%) | 49 (25%) | 9 (5%) | 108 (56%) |

| Fisher exact test statistic value = 0.54 | The result is not significant at p < 0.05 | |||

| Number of patients | 86 | 78 | 21 | 185 |

| Lenalidomide maintenance therapy | ||||

| At the time of the survey | 68 (36%) | 48 (26%) | 18 (10%) | 134 (72%) |

| Before the time of the survey | 18 (10%) | 30 (16%) | 3 (2%) | 51 (28%) |

| Fisher exact test statistic value = 0.0164 | The result is significant at p < 0.05 | |||

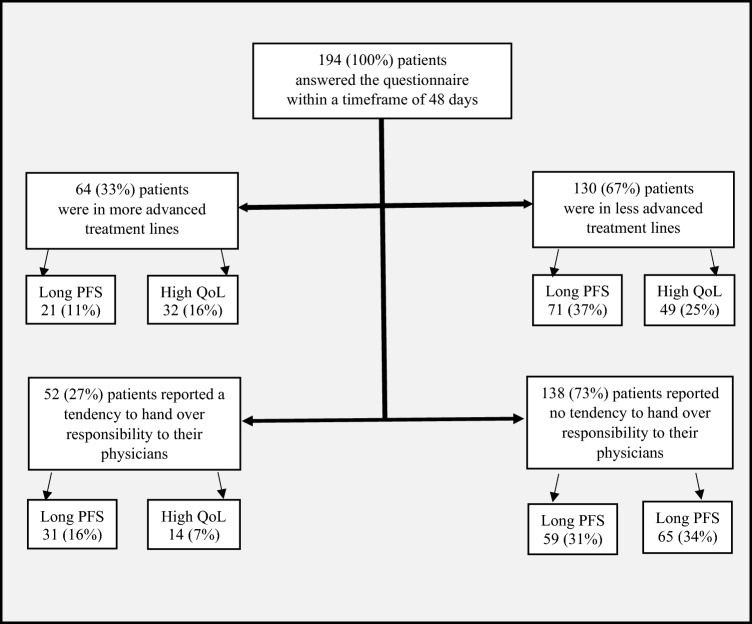

Of 194 patients with MM who answered this question, an unexpected high number of 81 (42%) subjects were willing to accept a shorter PFS for better QoL. On the other hand, 92 (47%) preferred a longer PFS at the cost of reduced QoL. Twenty-one patients (11%) indicated to be undecided.

Patient flow

We next addressed the question whether specific features were associated with the two main groups (“in favor QoL” vs “in favor PFS”) (Sacristán et al. 2016). Patients who belonged to the “in favor QoL”-group tended to be in more advanced treatment lines when compared to the “in favor PFS-group” (P = 0.0001; Fisher test, not corrected for multiple testing). Those patients who had received LEN maintenance therapy before the time of the survey and whose LEN therapy had been terminated before the time the survey was undertaken, were significantly more likely to belong to the “in favor QoL”-group. Patients who preferred PFS were found to generally be more likely to hand over responsibility to their physicians (P = 0.01; Fisher test). No associations were found for other disease specific conditions including pain, gastrointestinal symptoms, fatigue or infection (Table 1). Of note, we did not find differences between severe or very severe side effects being associated with one of the two groups. It is important to take into consideration, that these results were gathered using an anonymous web-based questionnaire, and patients’ preferences on possible outcome measures in myeloma may change over time during the course of treatment and have yet to be determined. Despite these limitations, we conclude that QoL constitutes the central outcome measure for roughly half of our patients.

Planning a new generation of clinical trials requires active involvement of patients to value their preferences concerning study endpoints (Mohyuddin et al. 2022; Auclair et al. 2022; Mols et al. 2012). It is important to consider the patient’s perspective to adapt study design and endpoints to the needs of the patients. This procedure may add a new dimension to traditional outcome measures specifically regarding the primary endpoint. While capturing changes in QoL has become standard in clinical trials, it remains difficult for both patients and treating physicians to envision the trade-off between survival outcome and QoL and to use this information for shared decision-making. In our opinion, statistically significant results alone are barely helpful. As an alternative approach, we propose to provide a trade-off between PFS and QoL presented in terms of likelihood rather than statistical significance. For instance, for an individual patient treated in arm A of a given study, the likelihood of being progression-free at 3 years from treatment may be 80% and QoL 70%, whereas in arm B PFS likelihood is 60% and QoL 90%.

In conclusion, our data strongly suggest that future studies in this setting should include PFS and QoL measures as co-primary endpoints to account for the heterogeneity in patients’ preferences and to collect the information necessary for shared decision-making in future patients. The results of our study accentuate significant differences in patients’ preferences, thus underlining the importance of assessing individual patient needs in determining the endpoints of further research.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the patients for their active involvement in this study.

Author contributions

Conception and design: All authors. Collection and assembly of data: All authors. Data analysis and interpretation: All authors. Manuscript writing: All authors. Final approval of manuscript: All authors. Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This study was funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research. (BMBF O1KD 1906).

Data availability

The data is available upon request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

KJ reports personal fees as an invited speaker from Amgen, art tempi, Helsinn, Hexal, med update GmbH, MSD, Mundipharma, onkowissen, Riemser, Roche, Shire (Takeda) and Vifor; personal fees for advisory board membership from Amgen, AstraZeneca, BD Solutions, Hexal, Karyopharm and Voluntis HE reports personal fees from: Janssen,Celgene/BMS, Amgen, GSK, Sanofi: Consultancy, Honoraria, Research, NW: Sanofi: Honoraria. AF: fees for advisory board membership from GSK, speaker training BMS, LR personal fees from: Janssen,Celgene/BMS, Amgen, GSK, Sanofi, Pfizer: Consultancy, Honoraria. The remaining authors report no conflict of interests.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the ethics committee of Würzburg (AZ 270/20).

Consent to participate

Only patients who were able to give informed consent were included.

Consent for publication

All included patients gave their consent for publication of the collected data.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Anna Fleischer and Larissa Zapf contributed equally.

References

- Auclair D, et al. Preferences and priorities for relapsed multiple myeloma treatments among patients and caregivers in the United States. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2022;16:573. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S345906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelhardt M, Ihorst G, Singh M, Rieth A, Saba G, Pellan M, Lebioda A. Real-world evaluation of health-related quality of life in patients with multiple myeloma from Germany. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2021;21(2):e160–e175. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2020.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holstein SA, et al. Updated analysis of CALGB (Alliance) 100104 assessing lenalidomide versus placebo maintenance after single autologous stem-cell transplantation for multiple myeloma: a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2017;4(9):e431–e442. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(17)30140-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan K, et al. Effect of general symptom level, specific adverse events, treatment patterns, and patient characteristics on health-related quality of life in patients with multiple myeloma: results of a European, multicenter cohort study. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22(2):417–426. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1991-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan K, Aapro M, Kaasa S, et al. ESMO position paper on supportive and palliative care. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:36–43. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy PL, et al. Lenalidomide maintenance after autologous stem-cell transplantation in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: a meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(29):3279. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.72.6679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohyuddin GR et al (2022) A patient perspective on cure in multiple myeloma: a survey of over 1,500 patients, pp 8046–8046.

- Mols F, et al. Health-related quality of life and disease-specific complaints among multiple myeloma patients up to 10 yr after diagnosis: results from a population-based study using the PROFILES registry. Eur J Haematol. 2012;89(4):311–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2012.01831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlyn C, et al. Lenalidomide-induced diarrhea in patients with myeloma is caused by bile acid malabsorption that responds to treatment. Blood. 2014;124(15):2467–2468. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-06-583302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson PG, et al. Triplet therapy, transplantation, and maintenance until progression in myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:132–147. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2204925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacristán JA, et al. Patient involvement in clinical research: why, when, and how. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:631. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S104259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data is available upon request.